Rick Just's Blog, page 105

January 9, 2022

The Governor from Arco (tap to read)

It would probably not surprise you that a 19-year-old “printer’s devil” (apprentice) went on to purchase and operate a small-town newspaper in Idaho. Clarence Bottolfsen was that young man. A North Dakota publisher founded the Arco Advertiser in 1909 and sent for Bottolfsen who had assisted him on publications in that state. In a few years young Bottolfsen purchased the Arco paper. He would run it until 1949 and would also serve as editor and general manager of the Blackfoot Daily Bulletin from 1934-1938. He was elected president of the Idaho Editorial Association in 1929.

So, a newspaper man through and through. No surprise. What might be news to you is why he is well-known in Idaho history.

Clarence A. Bottolfsen participated in Idaho politics. A lot. He served in the Idaho House of Representatives in the 1921 and 1923 session, back when the legislature met every other year. He had the appointed position of chief clerk of the House in 1925 and 1927, then came back as an elected representative in 1929 and 1931, serving as speaker of the house in 1931. He worked as Republican State Chair in 1936 and 37. In 1938 Idaho citizens elected him governor. In 1940 he ran for that office, again, but lost to Chase Clark. He had better luck in 1942, defeating Clark and serving a second term, making him the first governor in Idaho to serve in non-consecutive terms. Cecil D. Andrus was the second.

Bottolfsen ran for U.S. Senate in 1944, losing to Glen H. Taylor. He was appointed chief clerk of the Idaho House in 1949 and 1951. In 1953 he served as Deputy Sergeant of Arms of the U.S. Senate. He was back in Idaho in 1955 and 1956, serving again as the Chief Clerk of the Idaho House.

In 1958. Bottolfsen ran for a seat in the Idaho Senate. He won, serving until 1962 when his health precluded another run.

If you think serving as governor, twice, several terms in the Idaho House and Senate, and various political appointments, along with running a newspaper was enough to keep Bottolfsen busy, you’d be wrong. He was elected permanent parliamentarian for the National Education Association in 1937, a post he held for 17 years. Bottolfsen also served as State Commander of the American Legion (he served in the army during WWI) and was active in the Masons, and the Arco Chamber of Commerce and Rotary Club.

C.A. Bottolfsen passed away at the VA Hospital in Boise in 1964. He was 72.

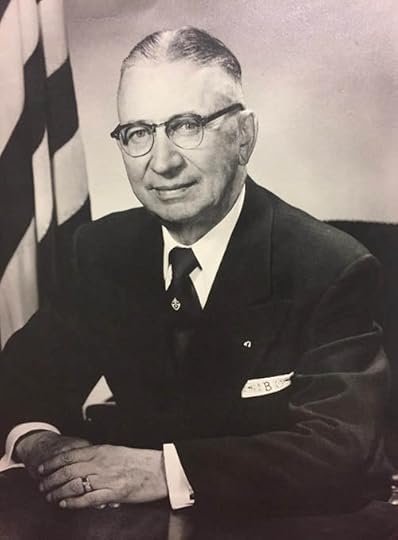

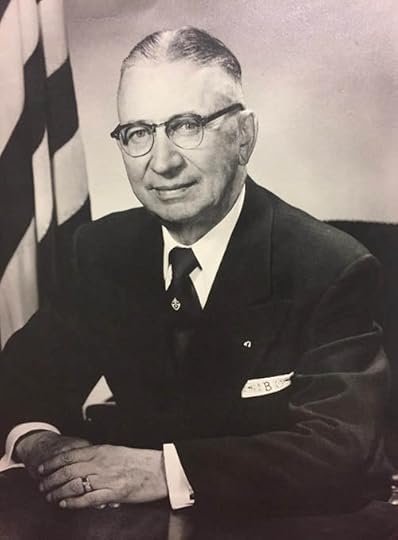

Dedicated Idaho politician C.A. Bottolfsen.

Dedicated Idaho politician C.A. Bottolfsen.

So, a newspaper man through and through. No surprise. What might be news to you is why he is well-known in Idaho history.

Clarence A. Bottolfsen participated in Idaho politics. A lot. He served in the Idaho House of Representatives in the 1921 and 1923 session, back when the legislature met every other year. He had the appointed position of chief clerk of the House in 1925 and 1927, then came back as an elected representative in 1929 and 1931, serving as speaker of the house in 1931. He worked as Republican State Chair in 1936 and 37. In 1938 Idaho citizens elected him governor. In 1940 he ran for that office, again, but lost to Chase Clark. He had better luck in 1942, defeating Clark and serving a second term, making him the first governor in Idaho to serve in non-consecutive terms. Cecil D. Andrus was the second.

Bottolfsen ran for U.S. Senate in 1944, losing to Glen H. Taylor. He was appointed chief clerk of the Idaho House in 1949 and 1951. In 1953 he served as Deputy Sergeant of Arms of the U.S. Senate. He was back in Idaho in 1955 and 1956, serving again as the Chief Clerk of the Idaho House.

In 1958. Bottolfsen ran for a seat in the Idaho Senate. He won, serving until 1962 when his health precluded another run.

If you think serving as governor, twice, several terms in the Idaho House and Senate, and various political appointments, along with running a newspaper was enough to keep Bottolfsen busy, you’d be wrong. He was elected permanent parliamentarian for the National Education Association in 1937, a post he held for 17 years. Bottolfsen also served as State Commander of the American Legion (he served in the army during WWI) and was active in the Masons, and the Arco Chamber of Commerce and Rotary Club.

C.A. Bottolfsen passed away at the VA Hospital in Boise in 1964. He was 72.

Dedicated Idaho politician C.A. Bottolfsen.

Dedicated Idaho politician C.A. Bottolfsen.

Published on January 09, 2022 04:00

January 8, 2022

Artesian City (tap to read)

Water in the West is precious. “Whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting over,” said Mark Twain. Possibly. No one has ever nailed down that quote as his, but it says a lot about the value of water in an arid country.

Imagine how settlers must have felt when they heard about water bubbling out of the desert all by itself in seemingly endless quantities. Bonus: The water came springing out of the earth at 110 degrees like a gift from God.

Artesian City came into existence because of two wells that James E. Bower drilled on the Cassia-Twin Falls county line a couple of miles south of Murtaugh Lake in 1895. Bower watered his cattle with the wells for a while, but he thought they might be an attractant for farmers whose crops might benefit from warm water.

By 1909, Bower had enticed a couple dozen families to purchase property from him. And, indeed, the crops seemed to respond well to warm water. Potatoes faired particularly well. Cattle seemed to do better drinking all the warm winter water they wanted. A couple of cattlemen from California moved 5,000 head into the area. The claim was that feeding alfalfa to cows that had access to warm water was worth about $1 a ton in feeding value.

Artesian City popped up with a general store, school, hotel, a couple of dance halls, a livery stable, a post office and a cemetery. The post office operated just a couple of years, from 1909 to 1911. The cemetery is still… operating.

In 1910, developers brought a sanatorium to Artesian City “for the cure of the ailments of humanity,” according to an Idaho Statesman article at the time. The project included a 40-room hotel with each room offering a bathtub in which one could soak privately in hot water. The water contained “Sulphur, iron, and magnesia in quantities that render it valuable in the eradication of many diseases of the human family.”

The sanatorium lasted into the 40s. The wells were capped after that. Some say drilling for irrigation water in the area has since killed the artesian effect.

One footnote worth mentioning is that James Bower, who dreamed of providing warm water to crops, played another role in Idaho history. He was the ranch foreman who hired “Diamondfield” Jack Davis. More important, he was one of the men who confessed to the murder of a pair of sheepherders that Davis had been convicted of killing. That confession freed “Diamondfield” Jack and seemed to have done Bower no discernible harm. The two artesian wells drilled by James Bower in 1895 bubbled up ten feet high. [image error] The sanatorium at Artesian City.

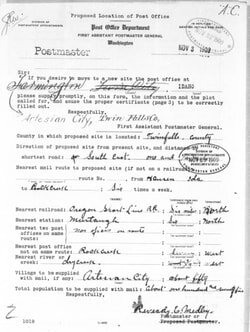

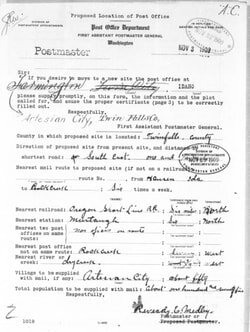

The two artesian wells drilled by James Bower in 1895 bubbled up ten feet high. [image error] The sanatorium at Artesian City.  The application for a post office showed some indecision on the part of residents. Two town names were crossed out before they settled on Artesian City. Image courtesy of Bob Omberg who has the best collection of information about Idaho post offices that I know of.

The application for a post office showed some indecision on the part of residents. Two town names were crossed out before they settled on Artesian City. Image courtesy of Bob Omberg who has the best collection of information about Idaho post offices that I know of.

Imagine how settlers must have felt when they heard about water bubbling out of the desert all by itself in seemingly endless quantities. Bonus: The water came springing out of the earth at 110 degrees like a gift from God.

Artesian City came into existence because of two wells that James E. Bower drilled on the Cassia-Twin Falls county line a couple of miles south of Murtaugh Lake in 1895. Bower watered his cattle with the wells for a while, but he thought they might be an attractant for farmers whose crops might benefit from warm water.

By 1909, Bower had enticed a couple dozen families to purchase property from him. And, indeed, the crops seemed to respond well to warm water. Potatoes faired particularly well. Cattle seemed to do better drinking all the warm winter water they wanted. A couple of cattlemen from California moved 5,000 head into the area. The claim was that feeding alfalfa to cows that had access to warm water was worth about $1 a ton in feeding value.

Artesian City popped up with a general store, school, hotel, a couple of dance halls, a livery stable, a post office and a cemetery. The post office operated just a couple of years, from 1909 to 1911. The cemetery is still… operating.

In 1910, developers brought a sanatorium to Artesian City “for the cure of the ailments of humanity,” according to an Idaho Statesman article at the time. The project included a 40-room hotel with each room offering a bathtub in which one could soak privately in hot water. The water contained “Sulphur, iron, and magnesia in quantities that render it valuable in the eradication of many diseases of the human family.”

The sanatorium lasted into the 40s. The wells were capped after that. Some say drilling for irrigation water in the area has since killed the artesian effect.

One footnote worth mentioning is that James Bower, who dreamed of providing warm water to crops, played another role in Idaho history. He was the ranch foreman who hired “Diamondfield” Jack Davis. More important, he was one of the men who confessed to the murder of a pair of sheepherders that Davis had been convicted of killing. That confession freed “Diamondfield” Jack and seemed to have done Bower no discernible harm.

The two artesian wells drilled by James Bower in 1895 bubbled up ten feet high. [image error] The sanatorium at Artesian City.

The two artesian wells drilled by James Bower in 1895 bubbled up ten feet high. [image error] The sanatorium at Artesian City.  The application for a post office showed some indecision on the part of residents. Two town names were crossed out before they settled on Artesian City. Image courtesy of Bob Omberg who has the best collection of information about Idaho post offices that I know of.

The application for a post office showed some indecision on the part of residents. Two town names were crossed out before they settled on Artesian City. Image courtesy of Bob Omberg who has the best collection of information about Idaho post offices that I know of.

Published on January 08, 2022 04:00

January 7, 2022

Kleinschmidt (tap to read)

Albert Kleinschmidt had more money than he needed. He was a wealthy merchant and mine owner in Helena, Montana who made an expensive decision that would result in little more than getting his name on some Idaho maps.

Kleinschmidt bought into a trio of mines, the Helena, the Peacock, and the White Monument, in Idaho’s Seven Devils country in 1885. Most Idaho miners at the time were obsessed with gold and silver, but these were copper mines. They were difficult to get to on foot or by mule. Getting there wasn’t the problem, though. It was getting copper ore out and to market that was an issue. You can pack only so much ore out in your pockets.

Our money man from Helena thought the solution might be a road down to the Snake River where steamboats could load up the ore and move it to Weiser to catch the nearest railroad line.

Building the road went fast, but that doesn’t mean it was easy. Kleinschmidt threw money into the construction, hiring experienced crews and pushing them to work on the road in all weather. It took them a couple of years, but the result was a 22-mile tangle of switchbacks that dropped 3,000 feet into Hells Canyon. The Kleinschmidt Grade was completed July 31, 1891. It cost $20,000.

Lounging in a chair today with our hindsight firmly installed, we can ask why the heck Kleinschmidt didn’t try the steamboat leg of the plan first, before putting so much money into the road. They built the Norma in 1891 for the purpose of hauling ore to Weiser, only to find out that navigating a steamboat up to the terminus of the road was treacherous. At about the same time they learned that little tidbit of information, the price of copper dropped through the floor.

Others had some later success in getting copper out, but no one ever made any money on it. Losing money on mining operations in the Seven Devils has been something of a tradition ever since Albert Kleinschmidt built that twisty memorial to himself.

You can take the Kleinschmidt Grade today if you have a vehicle that is ready for it. Be on the lookout for oncoming traffic. Two rigs can’t get by each other just anywhere on the road.

[image error]

Kleinschmidt bought into a trio of mines, the Helena, the Peacock, and the White Monument, in Idaho’s Seven Devils country in 1885. Most Idaho miners at the time were obsessed with gold and silver, but these were copper mines. They were difficult to get to on foot or by mule. Getting there wasn’t the problem, though. It was getting copper ore out and to market that was an issue. You can pack only so much ore out in your pockets.

Our money man from Helena thought the solution might be a road down to the Snake River where steamboats could load up the ore and move it to Weiser to catch the nearest railroad line.

Building the road went fast, but that doesn’t mean it was easy. Kleinschmidt threw money into the construction, hiring experienced crews and pushing them to work on the road in all weather. It took them a couple of years, but the result was a 22-mile tangle of switchbacks that dropped 3,000 feet into Hells Canyon. The Kleinschmidt Grade was completed July 31, 1891. It cost $20,000.

Lounging in a chair today with our hindsight firmly installed, we can ask why the heck Kleinschmidt didn’t try the steamboat leg of the plan first, before putting so much money into the road. They built the Norma in 1891 for the purpose of hauling ore to Weiser, only to find out that navigating a steamboat up to the terminus of the road was treacherous. At about the same time they learned that little tidbit of information, the price of copper dropped through the floor.

Others had some later success in getting copper out, but no one ever made any money on it. Losing money on mining operations in the Seven Devils has been something of a tradition ever since Albert Kleinschmidt built that twisty memorial to himself.

You can take the Kleinschmidt Grade today if you have a vehicle that is ready for it. Be on the lookout for oncoming traffic. Two rigs can’t get by each other just anywhere on the road.

[image error]

Published on January 07, 2022 04:00

January 6, 2022

40 Horse Cave (tap to read)

I grew up hearing about picnics and other mild adventures at 40 Horse Cave. It’s located within Wolverine Canyon about 15 miles from Firth, and about 10 miles from the Blackfoot River Valley where I grew up.

I ran across a photo of 40 Horse Cave in an old family album and decided to find out more about it, mainly why it is called 40 Horse Cave.

There are two schools of thought about the name. One is that two men climbed up to the cave and commented to the other that you could put 40 horses inside. The second is that there actually were 40 horses in the cave on one occasion, that occasion being when horse thieves hid them there while being pursued by a posse.

To my disappointment, I could not find any documentation or early mentions of the cave that might have given me a clue as to the derivation of the name. I can only say that the horse thief story seems highly unlikely. The cave is about one hundred feet from the bottom of the canyon where the road is today. There was likely a trail through the canyon in the same location going back long before European settlers.

The climb up to the cave is steep and the slope has a lot of loose shale to navigate. Getting one horse, let alone 40, up into the cave would require several men or several hours. Each would have to be led up the steep slope, parked (a well-known equestrian term), and settled inside. They could not possibly be driven up the slope and into the cave even by the most persistent thieves. Further, even if one could drive horses up the slope and hide them in the cave, the resulting disturbance on the slope would be quite obvious from below. Need I mention that 40 horses standing around inside a spooky space would likely make some nervous noise?

The cave is certainly big enough to house horses, though it isn’t very deep. It goes back only about 50 feet.

I look forward to better horsemen than I am speculating about how to get horses into the cave. Maybe we could make it an annual reenactment. I’ll buy the first ticket.

A photo of 40 Horse Cave probably taken in the 1940s by Doug Reid.

A photo of 40 Horse Cave probably taken in the 1940s by Doug Reid.

I ran across a photo of 40 Horse Cave in an old family album and decided to find out more about it, mainly why it is called 40 Horse Cave.

There are two schools of thought about the name. One is that two men climbed up to the cave and commented to the other that you could put 40 horses inside. The second is that there actually were 40 horses in the cave on one occasion, that occasion being when horse thieves hid them there while being pursued by a posse.

To my disappointment, I could not find any documentation or early mentions of the cave that might have given me a clue as to the derivation of the name. I can only say that the horse thief story seems highly unlikely. The cave is about one hundred feet from the bottom of the canyon where the road is today. There was likely a trail through the canyon in the same location going back long before European settlers.

The climb up to the cave is steep and the slope has a lot of loose shale to navigate. Getting one horse, let alone 40, up into the cave would require several men or several hours. Each would have to be led up the steep slope, parked (a well-known equestrian term), and settled inside. They could not possibly be driven up the slope and into the cave even by the most persistent thieves. Further, even if one could drive horses up the slope and hide them in the cave, the resulting disturbance on the slope would be quite obvious from below. Need I mention that 40 horses standing around inside a spooky space would likely make some nervous noise?

The cave is certainly big enough to house horses, though it isn’t very deep. It goes back only about 50 feet.

I look forward to better horsemen than I am speculating about how to get horses into the cave. Maybe we could make it an annual reenactment. I’ll buy the first ticket.

A photo of 40 Horse Cave probably taken in the 1940s by Doug Reid.

A photo of 40 Horse Cave probably taken in the 1940s by Doug Reid.

Published on January 06, 2022 04:00

January 5, 2022

A Handy Pronouncement (tap to read)

I’ve done posts about the origin of many Idaho place names, leaning heavily on the work of Lalia Boone and her book Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary. That book, sadly, is now out of print, but can be obtained for about $50 from various places on the Internet.

Sometimes I’ve posted about the pronunciation of Idaho place names, something Lalia did only when the pronunciation wasn’t obvious. For instance, Pahsimeroi is pronounced, according to Lalia, pu-SIM-uh-roy. It is allegedly of Shoshoni origin with pah meaning water, sima meaning one, and roi meaning grove. The river had one noticeable grove of trees on its bank.

Lalia’s book, published by the University of Idaho Press, came out in 1988.

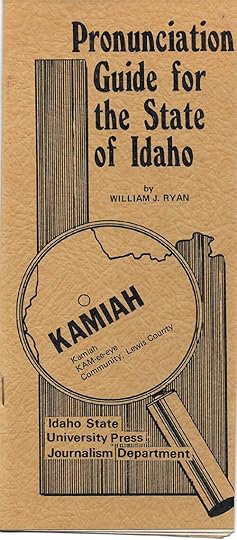

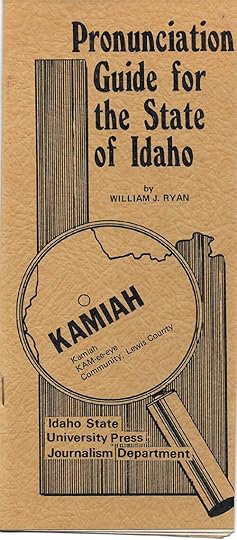

I ran across an old favorite the other day, the Pronunciation Guide for the State of Idaho, by William J. Ryan. It was published in 1975 by the Idaho State Press Journalism Department as a guide for radio and television announcers who might encounter an Idaho place name for the first time and wonder how the heck you pronounce Weippe. The answer is WEE-ipe, according to the ISU publication and everyone I’ve ever talked with who seemed to know.

In 1975, Ryan noted that there were 40 radio stations in Idaho. Nowadays there are that many receivable in the Boise market and 187 statewide. The number of TV stations hasn’t grown as much, though streaming choices are endless. In 1975 there were 11 TV stations in Idaho, compared with 19 today.

It’s probably time to do an updated pronunciation guide, since we’ve had a few hundred thousand people move into the state in recent years. There are some place names that didn’t exist when either of the two publications came out. Maybe that’s not a big problem. I can’t think of a way to mispronounce Avimor.

To own your personal copy of the ISU publication, you can download it here.

Thanks to Stuart Summers, Associate Vice President of Marketing, Communications, and Strategic Initiatives at Idaho State University for his help in making this possible.

Sometimes I’ve posted about the pronunciation of Idaho place names, something Lalia did only when the pronunciation wasn’t obvious. For instance, Pahsimeroi is pronounced, according to Lalia, pu-SIM-uh-roy. It is allegedly of Shoshoni origin with pah meaning water, sima meaning one, and roi meaning grove. The river had one noticeable grove of trees on its bank.

Lalia’s book, published by the University of Idaho Press, came out in 1988.

I ran across an old favorite the other day, the Pronunciation Guide for the State of Idaho, by William J. Ryan. It was published in 1975 by the Idaho State Press Journalism Department as a guide for radio and television announcers who might encounter an Idaho place name for the first time and wonder how the heck you pronounce Weippe. The answer is WEE-ipe, according to the ISU publication and everyone I’ve ever talked with who seemed to know.

In 1975, Ryan noted that there were 40 radio stations in Idaho. Nowadays there are that many receivable in the Boise market and 187 statewide. The number of TV stations hasn’t grown as much, though streaming choices are endless. In 1975 there were 11 TV stations in Idaho, compared with 19 today.

It’s probably time to do an updated pronunciation guide, since we’ve had a few hundred thousand people move into the state in recent years. There are some place names that didn’t exist when either of the two publications came out. Maybe that’s not a big problem. I can’t think of a way to mispronounce Avimor.

To own your personal copy of the ISU publication, you can download it here.

Thanks to Stuart Summers, Associate Vice President of Marketing, Communications, and Strategic Initiatives at Idaho State University for his help in making this possible.

Published on January 05, 2022 04:00

January 4, 2022

The Dark Side of a Pioneer Family, Part 2 (tap to read)

Yesterday I told you about Angela O’Farrell Hopper, the daughter of the first family to erect a permanent building in Boise. She was convicted of embezzling from the City of Boise. Everyone was shocked. Why had she done it and where had the money gone?

In November of 1933, a couple of months after Hopper’s arrest, the story began to come together when her son, John, was arrested for receiving stolen property. The complaint against 21-year-old John, or Johnny, Hopper was that he had received $20,401.49 from his mother. Angela Hopper was already in prison, and John would shortly join her there.

Young Mr. Hopper, with his aunt Theresa O’Farrell in the courtroom looking on, denied that he knew the money his mother sent him was stolen. As reported in the Idaho Statesman on February 10, 1934, he said “Why if it was patent that this was stolen money did not the telephone company, the merchants and businessmen who received this money in Boise suspect something wrong?”

The prosecution argued that he knew well his mother’s financial circumstances and must have known the money was obtained illegitimately. They produced telegrams Hopper had sent to his mother from California demanding money time and again. Johnny Hopper had an extensive record of juvenile offenses and had a reputation in his Boise neighborhood for dealing violently with his mother and aunt when he didn’t get his way.

Hopper was a dapper looking young man with a high pompadour and a pencil thin mustache. He was described in newspaper reports as a Hollywood playboy who lived in a luxurious apartment. He had married an exotic chorus girl, though that match didn’t last.

The jury took just a few hours of deliberation to find John Hopper guilty. He was sentenced to from two to five years in February of 1934.

The “playboy” seemed to quickly mend his ways while in prison, deciding to become a lawyer and taking a correspondence course in the law while there. His good behavior convinced the parole board to set him free in November 1935 after just 20 months in prison.

In December of that year, John Hopper was on his way back to Los Angeles where he had a job lined up and an attorney interested in helping him pursue his legal career.

Three weeks later Hopper was back in a Boise jail charged with being drunk and disorderly. He failed to appear at his hearing, forfeiting his bond. It was the first of several arrests and forfeitures for Hopper.

In May 1936, his mother, convicted embezzler Angela Hopper was conditionally pardoned and released under parole to a couple in San Francisco.

In May, 1937, things got serious in Boise. Police answered a call at 420 Franklin Street, the O’Farrell family mansion, and discovered Hopper’s aunt, Theresa O’Farrell in a semi-conscious condition on her front lawn. She had been beaten over the head with a heavy platter. Inside the house they found pieces of the platter in a pool of blood. While investigators were in the house, John Hopper entered and demanded to know “what has happened here?” They noted that his clothing was bloodstained and quickly arrested him for assault.

A few days later, Hopper was charged with a complaint of insanity. His aunt, Theresa O’Farrell was still recovering in a Boise hospital where her condition was serious. He was judged to be an inebriate and committed to the state mental hospital at Blackfoot by district court Judge Charles F. Winstead.

Dr. V. E. Fisher and Dr. Mary Calloway testified that the former Hollywood night life addict should be placed under medical treatment with the possibility that he might be cured.

Under Idaho law, two years was the maximum he could spend at the mental institution. He would not come close to pushing that limit.

John Hopper was released from the asylum five months later, paroled by the hospital’s superintendents. They had the power to do so but took quite a lot of heat for it. The Director of Charitable Institutions, Lewis Williams, said, “I approved the parole. If a mistake has been made I assume all responsibility. But until Hopper demonstrates by misconduct that a mistake has been made, I have no apologies to make.” Hopper left the state for San Francisco.

While researching this story I expected to find evidence that Lewis Williams would be called on his mistake of releasing John Hopper. I found no further record of imprisonment for him, though. He sold cars for a while, then dropped off the radar. John Hopper died in California in 1951. The Idaho Statesman on June 4, 1953, noted that “Mrs. Angela O’Farrell Hopper, a resident of Boise until moving to San Francisco, Cal., several years ago, died there after a long illness.” No mention was made of her pioneer family or her time in the glare of a Boise spotlight. Mugshot photo of Johnny Hopper. He was convicted of receiving stolen property, money his mother, Angela O’Farrell Hopper, embezzled from the City of Boise. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Mugshot photo of Johnny Hopper. He was convicted of receiving stolen property, money his mother, Angela O’Farrell Hopper, embezzled from the City of Boise. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

In November of 1933, a couple of months after Hopper’s arrest, the story began to come together when her son, John, was arrested for receiving stolen property. The complaint against 21-year-old John, or Johnny, Hopper was that he had received $20,401.49 from his mother. Angela Hopper was already in prison, and John would shortly join her there.

Young Mr. Hopper, with his aunt Theresa O’Farrell in the courtroom looking on, denied that he knew the money his mother sent him was stolen. As reported in the Idaho Statesman on February 10, 1934, he said “Why if it was patent that this was stolen money did not the telephone company, the merchants and businessmen who received this money in Boise suspect something wrong?”

The prosecution argued that he knew well his mother’s financial circumstances and must have known the money was obtained illegitimately. They produced telegrams Hopper had sent to his mother from California demanding money time and again. Johnny Hopper had an extensive record of juvenile offenses and had a reputation in his Boise neighborhood for dealing violently with his mother and aunt when he didn’t get his way.

Hopper was a dapper looking young man with a high pompadour and a pencil thin mustache. He was described in newspaper reports as a Hollywood playboy who lived in a luxurious apartment. He had married an exotic chorus girl, though that match didn’t last.

The jury took just a few hours of deliberation to find John Hopper guilty. He was sentenced to from two to five years in February of 1934.

The “playboy” seemed to quickly mend his ways while in prison, deciding to become a lawyer and taking a correspondence course in the law while there. His good behavior convinced the parole board to set him free in November 1935 after just 20 months in prison.

In December of that year, John Hopper was on his way back to Los Angeles where he had a job lined up and an attorney interested in helping him pursue his legal career.

Three weeks later Hopper was back in a Boise jail charged with being drunk and disorderly. He failed to appear at his hearing, forfeiting his bond. It was the first of several arrests and forfeitures for Hopper.

In May 1936, his mother, convicted embezzler Angela Hopper was conditionally pardoned and released under parole to a couple in San Francisco.

In May, 1937, things got serious in Boise. Police answered a call at 420 Franklin Street, the O’Farrell family mansion, and discovered Hopper’s aunt, Theresa O’Farrell in a semi-conscious condition on her front lawn. She had been beaten over the head with a heavy platter. Inside the house they found pieces of the platter in a pool of blood. While investigators were in the house, John Hopper entered and demanded to know “what has happened here?” They noted that his clothing was bloodstained and quickly arrested him for assault.

A few days later, Hopper was charged with a complaint of insanity. His aunt, Theresa O’Farrell was still recovering in a Boise hospital where her condition was serious. He was judged to be an inebriate and committed to the state mental hospital at Blackfoot by district court Judge Charles F. Winstead.

Dr. V. E. Fisher and Dr. Mary Calloway testified that the former Hollywood night life addict should be placed under medical treatment with the possibility that he might be cured.

Under Idaho law, two years was the maximum he could spend at the mental institution. He would not come close to pushing that limit.

John Hopper was released from the asylum five months later, paroled by the hospital’s superintendents. They had the power to do so but took quite a lot of heat for it. The Director of Charitable Institutions, Lewis Williams, said, “I approved the parole. If a mistake has been made I assume all responsibility. But until Hopper demonstrates by misconduct that a mistake has been made, I have no apologies to make.” Hopper left the state for San Francisco.

While researching this story I expected to find evidence that Lewis Williams would be called on his mistake of releasing John Hopper. I found no further record of imprisonment for him, though. He sold cars for a while, then dropped off the radar. John Hopper died in California in 1951. The Idaho Statesman on June 4, 1953, noted that “Mrs. Angela O’Farrell Hopper, a resident of Boise until moving to San Francisco, Cal., several years ago, died there after a long illness.” No mention was made of her pioneer family or her time in the glare of a Boise spotlight.

Mugshot photo of Johnny Hopper. He was convicted of receiving stolen property, money his mother, Angela O’Farrell Hopper, embezzled from the City of Boise. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Mugshot photo of Johnny Hopper. He was convicted of receiving stolen property, money his mother, Angela O’Farrell Hopper, embezzled from the City of Boise. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on January 04, 2022 04:00

January 3, 2022

The Dark Side of a Pioneer Family, Part 1 (tap to read)

If you pay even a little attention to Boise’s history, you’ll know about the O’Farrell Cabin, the first permanent structure built in Boise. The city has preserved the cottonwood cabin in a location not far from where it was erected in 1863. This story, much less known, is about one of the O’Farrell’s daughters and how she slipped into a scandal that rocked the city she loved.

John and Mary O’Farrell had seven children. Two died in infancy. They raised five daughters and seven adopted children. In the interest of space, I will leave the stories of most of the O’Farrells for another time, concentrating on two daughters. Theresa, born in 1867, gets three cameo appearances in the story, which is largely about Angela, who was born in 1880.

Angela O’Farrell’s name appeared frequently in early newspapers. She was a student at St. Teresa’s, and by early accounts a good one. She was lauded for her careful embroidery, her skill at playing the piano, her singing, her drawing, and the essays she wrote. In 1889 she received a “crown of excellence” for perfect conduct.

When she was 17, Angela was one of dozens of contestants in the “Queen of Idaho” or “Queen of the Intermountain Fair” contest. The 1897 Intermountain Fair was Boise’s first big chance to show itself off. It would be a spectacular event if the Idaho Statesman had anything to say about it. The newspaper reported for weeks on the celebrities who might appear, the competitions to be held, and the rodeo that would attract cowboys from several states. The Statesman sponsored the “Queen” contest, raising money for the fair by soliciting votes from all over Idaho. You could vote as often as you liked, but each vote cost ten cents.

The winner of the contest was the daughter of a wealthy Lewiston businessman, 20-year-old Miss Bessie Volmer. The Statesman described her as “six feet tall and exceedingly graceful,” and they reported, “Few women are endowed by nature with greater personal beauty.”

Volmer received 3,813 votes. The runner up, with 2002 votes was Teresa O’Farrell. Angela O’Farrell received 16 votes. We don’t know how Angela felt about this, but it is likely she was happy for her older sister.

Angela had her life to get on with, anyway. She wanted to be a teacher and was in the first class of the “Teachers Institute and School of Methods,” housed for a time at Boise High School.

The mentions in the paper of Angela O’Farrell soon after were of the well-liked teacher in Meridian.

Angela married Edward Hopper in 1907. In 1911 the Hoppers had a son and named him John.

In 1920 Angela Hopper became the Boise City Clerk. Her name appeared in the news frequently in that official capacity. Then, in 1933 her world fell apart.

The headline in the Idaho Statesman on September 28 read, “Embezzlement Charges Rock Boise City Hall; Angela Hopper Arrested.”

As the story played out over the next few weeks and months the amount of the embezzlement climbed from $10,000, to $75,000, to somewhere near $100,000. A full accounting of what she took could never be made.

Hopper pleaded guilty and was sentenced to from one to ten years in the Idaho State Penitentiary.

One question on the minds of many Boiseans was, why? Why did a well-respected woman from a pioneer family risk embezzling all that money? A second question was, where did it go?

We’re going to answer those questions in tomorrow’s blog.

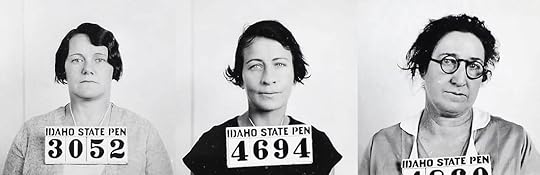

Left to right are Theresa, Angela, and Eveline O’Farrell. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Left to right are Theresa, Angela, and Eveline O’Farrell. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

John and Mary O’Farrell had seven children. Two died in infancy. They raised five daughters and seven adopted children. In the interest of space, I will leave the stories of most of the O’Farrells for another time, concentrating on two daughters. Theresa, born in 1867, gets three cameo appearances in the story, which is largely about Angela, who was born in 1880.

Angela O’Farrell’s name appeared frequently in early newspapers. She was a student at St. Teresa’s, and by early accounts a good one. She was lauded for her careful embroidery, her skill at playing the piano, her singing, her drawing, and the essays she wrote. In 1889 she received a “crown of excellence” for perfect conduct.

When she was 17, Angela was one of dozens of contestants in the “Queen of Idaho” or “Queen of the Intermountain Fair” contest. The 1897 Intermountain Fair was Boise’s first big chance to show itself off. It would be a spectacular event if the Idaho Statesman had anything to say about it. The newspaper reported for weeks on the celebrities who might appear, the competitions to be held, and the rodeo that would attract cowboys from several states. The Statesman sponsored the “Queen” contest, raising money for the fair by soliciting votes from all over Idaho. You could vote as often as you liked, but each vote cost ten cents.

The winner of the contest was the daughter of a wealthy Lewiston businessman, 20-year-old Miss Bessie Volmer. The Statesman described her as “six feet tall and exceedingly graceful,” and they reported, “Few women are endowed by nature with greater personal beauty.”

Volmer received 3,813 votes. The runner up, with 2002 votes was Teresa O’Farrell. Angela O’Farrell received 16 votes. We don’t know how Angela felt about this, but it is likely she was happy for her older sister.

Angela had her life to get on with, anyway. She wanted to be a teacher and was in the first class of the “Teachers Institute and School of Methods,” housed for a time at Boise High School.

The mentions in the paper of Angela O’Farrell soon after were of the well-liked teacher in Meridian.

Angela married Edward Hopper in 1907. In 1911 the Hoppers had a son and named him John.

In 1920 Angela Hopper became the Boise City Clerk. Her name appeared in the news frequently in that official capacity. Then, in 1933 her world fell apart.

The headline in the Idaho Statesman on September 28 read, “Embezzlement Charges Rock Boise City Hall; Angela Hopper Arrested.”

As the story played out over the next few weeks and months the amount of the embezzlement climbed from $10,000, to $75,000, to somewhere near $100,000. A full accounting of what she took could never be made.

Hopper pleaded guilty and was sentenced to from one to ten years in the Idaho State Penitentiary.

One question on the minds of many Boiseans was, why? Why did a well-respected woman from a pioneer family risk embezzling all that money? A second question was, where did it go?

We’re going to answer those questions in tomorrow’s blog.

Left to right are Theresa, Angela, and Eveline O’Farrell. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Left to right are Theresa, Angela, and Eveline O’Farrell. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on January 03, 2022 04:00

January 2, 2022

The 1933 Movie Night Scandal (Tap to Read)

Three ladies going to a movie with some friends wasn’t something that would typically generate headlines in 1933, but an outing in November of that year caused quite a sensation. Mrs. Southard, Mrs. Boggan and Mrs. Hopper went to see Flying Devils at the Fox Theater, better known today as The Egyptian. Their friends Mr. and Mrs. George Rudd went with them.

To understand the consternation of the citizenry, we need to add some detail to the story. George Rudd was the warden of the Idaho State Penitentiary. Lyda Southard, Marguerite Boggan, and Angela Hopper were women inmates.

Southard, the most notorious of the three, had been convicted of poisoning her husband in 1922. Evidence was building that she had dispatched a string of husbands in a similar fashion. Southard had escaped from prison in 1931 and was recaptured in Denver in 1932.

Boggan had an argument with her husband in Salmon that resulted in a struggle over a gun, which the husband lost, resulting in his demise. She was later pardoned.

Hopper had some notoriety of her own in Boise, though not for murder. Angela Hopper had served as city clerk in Boise for 13 years. Just a few days before movie night she had pled guilty to embezzling more than $50,000 from local improvement districts. (Note: We'll be hearing more about Hopper the next two days)

If treating inmates to a night at the movies was shocking, imagine how citizens reacted when they found out Warden Rudd had taken Hopper for a joy ride to Payette the day she was incarcerated. Rudd took Southard, who had already escaped once, to visit her mother in Twin Falls, leaving her unsupervised for hours.

Letting inmates enjoy some free time was apparently common at the prison. They were sometimes allowed to hike along the Boise River, play tennis on the courts at Julia Davis, and have an occasional picnic well outside the walls.

Warden Rudd chalked these special privileges up to simple acts of kindness to the prisoners in hopes of encouraging their rehabilitation. In his defense, none of the instances of beyond-the-walls excursions resulted in an escape during his tenure as a warden.

That tenure was, however, about to end. Rudd had been a state legislator representing Fremont County before being named warden in the spring of 1933. By January of 1934 he was out of a job because of the movie night scandal.

Rudd always felt justified in his actions and many years later in an oral history blamed his loss of the job on coverage by the Idaho Statesman, pointing out that he got terrific support from the Boise Capital News. Most newspapers at that time were blatantly political. The Statesman was a Republican newspaper and the Boise Capital News was Democratic. Rudd was a Democrat.

One might think that a kerfuffle such as the inmate movie night would have killed Rudd’s political career. Nope. The very next year he was putting out feelers about running for secretary of state. He decided not to but did run for lieutenant governor. Rudd lost that one and was defeated in a run for his old house seat in 1934. He was elected Chief Clerk of the Idaho House in 1935 and again in 1937. He ran for an Idaho senate seat in the 40s and won. His last political post came in 1960 when he became a probate judge. George Rudd passed away in 1970.

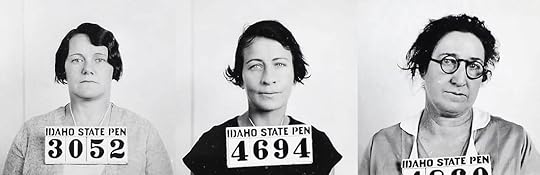

Lyda Southard, Marguerite Boggan, and Angela Hopper went to a movie and the warden got fired. Photos courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Lyda Southard, Marguerite Boggan, and Angela Hopper went to a movie and the warden got fired. Photos courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

To understand the consternation of the citizenry, we need to add some detail to the story. George Rudd was the warden of the Idaho State Penitentiary. Lyda Southard, Marguerite Boggan, and Angela Hopper were women inmates.

Southard, the most notorious of the three, had been convicted of poisoning her husband in 1922. Evidence was building that she had dispatched a string of husbands in a similar fashion. Southard had escaped from prison in 1931 and was recaptured in Denver in 1932.

Boggan had an argument with her husband in Salmon that resulted in a struggle over a gun, which the husband lost, resulting in his demise. She was later pardoned.

Hopper had some notoriety of her own in Boise, though not for murder. Angela Hopper had served as city clerk in Boise for 13 years. Just a few days before movie night she had pled guilty to embezzling more than $50,000 from local improvement districts. (Note: We'll be hearing more about Hopper the next two days)

If treating inmates to a night at the movies was shocking, imagine how citizens reacted when they found out Warden Rudd had taken Hopper for a joy ride to Payette the day she was incarcerated. Rudd took Southard, who had already escaped once, to visit her mother in Twin Falls, leaving her unsupervised for hours.

Letting inmates enjoy some free time was apparently common at the prison. They were sometimes allowed to hike along the Boise River, play tennis on the courts at Julia Davis, and have an occasional picnic well outside the walls.

Warden Rudd chalked these special privileges up to simple acts of kindness to the prisoners in hopes of encouraging their rehabilitation. In his defense, none of the instances of beyond-the-walls excursions resulted in an escape during his tenure as a warden.

That tenure was, however, about to end. Rudd had been a state legislator representing Fremont County before being named warden in the spring of 1933. By January of 1934 he was out of a job because of the movie night scandal.

Rudd always felt justified in his actions and many years later in an oral history blamed his loss of the job on coverage by the Idaho Statesman, pointing out that he got terrific support from the Boise Capital News. Most newspapers at that time were blatantly political. The Statesman was a Republican newspaper and the Boise Capital News was Democratic. Rudd was a Democrat.

One might think that a kerfuffle such as the inmate movie night would have killed Rudd’s political career. Nope. The very next year he was putting out feelers about running for secretary of state. He decided not to but did run for lieutenant governor. Rudd lost that one and was defeated in a run for his old house seat in 1934. He was elected Chief Clerk of the Idaho House in 1935 and again in 1937. He ran for an Idaho senate seat in the 40s and won. His last political post came in 1960 when he became a probate judge. George Rudd passed away in 1970.

Lyda Southard, Marguerite Boggan, and Angela Hopper went to a movie and the warden got fired. Photos courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Lyda Southard, Marguerite Boggan, and Angela Hopper went to a movie and the warden got fired. Photos courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on January 02, 2022 04:00

January 1, 2022

The First Female Mayor (Tap to read)

In her obituary, Laura Stockton Starcher was called a “pioneer Idaho resident.” True, she was born in Missouri in 1874, but here parents brought her to Parma when she was a year old. She lived for decades in Idaho and was buried in what she considered her hometown, Parma, when she died in 1960.

I’m defending Starcher’s Idaho bona fides because her claim to fame was something she did while she and her husband lived in Umatilla, Oregon. You’re welcome to quibble with me about whether this is Idaho history, but I remain the guy who writes this blog.

Laura Stockton Starcher was the leading figure of what newspapers across the country in 1916 called the Petticoat Revolution. At a card party several days before the municipal election, hostess Mrs. Robert Merrick convinced six of her friends, all women, that they should run for city council. Starcher would run for mayor. This came as a surprise to E.E. Starcher who was the incumbent mayor and Laura Starcher’s husband.

The surprise was part of the fun for the women. They were mostly mum about their plan, telling no man about it. All ran as write-ins, counting on the support of the women of Umatilla, who had gained the right to vote four years earlier.

At noon on election day the women won the majority of the seats on the city council. Starcher—the distaff Starcher—won the mayor’s seat by a vote of 28-6. The men had a good laugh over it and stepped back to let the women run the town.

It was a joke that was not a joke. The women recognized the humor in their plot, but they were also serious about bettering the town.

Madam Mayor Starcher, quoted in an interview in the Idaho Statesman, said, “Well, my husband’s administration claimed that the reason it accomplished so little for the city was that it was impossible to get the entire council, or even a quorum, out. Now, I intend to get my council out in this way. We will all be women except the two holdovers, men, who, I understand, are going to learn to do fancy work, in order to feel at home with us, and I shall turn the city council meetings into afternoon teas if necessary, in order to be sure of the full council being present.”

Starcher had a unique plan for ridding Umatilla of gambling, “the only grave violation of the law we know of.” She would appoint women, one a week, as detectives. No one would know who that week’s detective was. They would be unpaid, because “accomplishing results will be sufficient reward for the women.”

Now, dear reader if you are a woman, prepare to grit your teeth. The Statesman article noted that she was a “stylish little mayor, too… She is small and dainty, exceedingly vivacious and good looking. She wore, while in Boise, the most up-to-date of trotteur suits of Burgundy red, which suited her brunette type, and her stunning velvet hat and fox furs added to her chic appearance.”

We can’t judge editorial decisions made in 1916 through a 2021 lens. This was at a time when women were barely a blip on the political radar, so Mayor Starcher was treated as something of a unicorn. She was, after all, the first woman mayor in the United States.

Laura Stockton Starcher was the first women to be elected mayor of a city in the U.S. (Public Domain Photo)

Laura Stockton Starcher was the first women to be elected mayor of a city in the U.S. (Public Domain Photo)

I’m defending Starcher’s Idaho bona fides because her claim to fame was something she did while she and her husband lived in Umatilla, Oregon. You’re welcome to quibble with me about whether this is Idaho history, but I remain the guy who writes this blog.

Laura Stockton Starcher was the leading figure of what newspapers across the country in 1916 called the Petticoat Revolution. At a card party several days before the municipal election, hostess Mrs. Robert Merrick convinced six of her friends, all women, that they should run for city council. Starcher would run for mayor. This came as a surprise to E.E. Starcher who was the incumbent mayor and Laura Starcher’s husband.

The surprise was part of the fun for the women. They were mostly mum about their plan, telling no man about it. All ran as write-ins, counting on the support of the women of Umatilla, who had gained the right to vote four years earlier.

At noon on election day the women won the majority of the seats on the city council. Starcher—the distaff Starcher—won the mayor’s seat by a vote of 28-6. The men had a good laugh over it and stepped back to let the women run the town.

It was a joke that was not a joke. The women recognized the humor in their plot, but they were also serious about bettering the town.

Madam Mayor Starcher, quoted in an interview in the Idaho Statesman, said, “Well, my husband’s administration claimed that the reason it accomplished so little for the city was that it was impossible to get the entire council, or even a quorum, out. Now, I intend to get my council out in this way. We will all be women except the two holdovers, men, who, I understand, are going to learn to do fancy work, in order to feel at home with us, and I shall turn the city council meetings into afternoon teas if necessary, in order to be sure of the full council being present.”

Starcher had a unique plan for ridding Umatilla of gambling, “the only grave violation of the law we know of.” She would appoint women, one a week, as detectives. No one would know who that week’s detective was. They would be unpaid, because “accomplishing results will be sufficient reward for the women.”

Now, dear reader if you are a woman, prepare to grit your teeth. The Statesman article noted that she was a “stylish little mayor, too… She is small and dainty, exceedingly vivacious and good looking. She wore, while in Boise, the most up-to-date of trotteur suits of Burgundy red, which suited her brunette type, and her stunning velvet hat and fox furs added to her chic appearance.”

We can’t judge editorial decisions made in 1916 through a 2021 lens. This was at a time when women were barely a blip on the political radar, so Mayor Starcher was treated as something of a unicorn. She was, after all, the first woman mayor in the United States.

Laura Stockton Starcher was the first women to be elected mayor of a city in the U.S. (Public Domain Photo)

Laura Stockton Starcher was the first women to be elected mayor of a city in the U.S. (Public Domain Photo)

Published on January 01, 2022 04:00

December 31, 2021

Pop Quiz! (Tap to Participate)

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture. If you missed that story, click the letter for a link.

1). The gold-colored U.S. coin honoring Sacagawea is what denomination?

A. Penney

B. Nickel

C. Dime

D. Quarter

E. Dollar

2). What gift did Fred T. Dubois give to President Taft?

A. A bouquet of flowers

B. A thoroughbred stud

C. A key to the city Blackfoot

D. A pig

E. A bag of Idaho potatoes

3). Where did Jesse Owens stay when he visited Boise in 1945?

A. The Idanha

B. The Hotel Boise

C. At a private residence

D. The Owyhee

E. The Overland Hotel

4). What type of building is now a museum to Butch Cassidy in Montpelier, Idaho?

A. A church

B. A railroad roundhouse

C. A bank

D. His childhood home

E. A saloon

5) What were billiard balls commonly made from in 1864?

A. Ground up and reconstituted bones from cavalry horses

B. Ivory

C. Resin

D. Celluloid

E. Silica

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

1, E

2, D

3, C

4, C

5, B

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). The gold-colored U.S. coin honoring Sacagawea is what denomination?

A. Penney

B. Nickel

C. Dime

D. Quarter

E. Dollar

2). What gift did Fred T. Dubois give to President Taft?

A. A bouquet of flowers

B. A thoroughbred stud

C. A key to the city Blackfoot

D. A pig

E. A bag of Idaho potatoes

3). Where did Jesse Owens stay when he visited Boise in 1945?

A. The Idanha

B. The Hotel Boise

C. At a private residence

D. The Owyhee

E. The Overland Hotel

4). What type of building is now a museum to Butch Cassidy in Montpelier, Idaho?

A. A church

B. A railroad roundhouse

C. A bank

D. His childhood home

E. A saloon

5) What were billiard balls commonly made from in 1864?

A. Ground up and reconstituted bones from cavalry horses

B. Ivory

C. Resin

D. Celluloid

E. Silica

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)1, E

2, D

3, C

4, C

5, B

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on December 31, 2021 04:00