Rick Just's Blog, page 95

May 20, 2022

J.R. Simplot’s Seed Money (Tap to read)

J.R. Simplots origin story, as it were, is well known because he loved telling it. It’s a great story, so I’ll tell it again. By origin, I mean how he got to be wealthy.

John Richard Simplot understood how to make a dollar. He struck out on his own at age 14, leaving family and school behind. Not far behind, though. Simplot moved into a boarding house in his hometown of Declo to avoid arguments with his father. Leaving school at that age was quite common at the time. Young men had to get on with their working lives.

Simplot learned the basics of being a billionaire in that boarding house because of the eight school teachers who also boarded there for a dollar a day. Those teachers may have made some effort to pass on some knowledge to Simplot, but what he really learned was that they were willing to pass on half their salaries to him.

It was the middle of the Great Depression and money was tight. Teachers were paid not in dollars, but in scrip. Scrip was essentially an IOU, promising to pay the teachers at a later date, with a little interest. The teachers couldn’t wait until a later date, because they had bills to pay right then, such as what it cost to stay at the boarding house.

J.R. had left his home with $80 in gold certificates, money he had made from the sale of fat lambs. Carrying around that much money during hard times wasn’t wise, so he started a bank account. When he found out the boarding house residents were willing to sell their scrip to him for half its face value, he put that account to good use. He could afford to wait until the scrip matured.

In his biography, J.R Simplot—A billion the hard way*, by Louie Attebery, Simplot is quoted as saying, “It wasn’t a lotta money, but it was enough to make some money. I’d buy that scrip every month when [they got paid]. They had to pay their board bill…Damn board bill was about half their [salary]. Tough. You talk about tough times; they were tough! Tough, boy! But I accumulated a few hundred dollars, and I made some money.”

He had a lot of stories like that, because spotting a bargain or a deal was his life. Simplot was known as the potato king because his company invented a way to process French fries that caught on just a little bit with companies such as McDonalds. He was big in fertilizer, raising cattle, and funding the development of microchips. The latter proving that he never lost the business acumen that he gained back at that boarding house in Declo.

J.R. Simplot was Idaho’s first billionaire. In 2007 he was the 89th richest person in the United States, with a personal fortune estimated to be about $3.6 billion dollars. When he passed away in 2008 at age 99, Jack Simplot was the oldest billionaire on the Forbes 400 list.

John Richard Simplot understood how to make a dollar. He struck out on his own at age 14, leaving family and school behind. Not far behind, though. Simplot moved into a boarding house in his hometown of Declo to avoid arguments with his father. Leaving school at that age was quite common at the time. Young men had to get on with their working lives.

Simplot learned the basics of being a billionaire in that boarding house because of the eight school teachers who also boarded there for a dollar a day. Those teachers may have made some effort to pass on some knowledge to Simplot, but what he really learned was that they were willing to pass on half their salaries to him.

It was the middle of the Great Depression and money was tight. Teachers were paid not in dollars, but in scrip. Scrip was essentially an IOU, promising to pay the teachers at a later date, with a little interest. The teachers couldn’t wait until a later date, because they had bills to pay right then, such as what it cost to stay at the boarding house.

J.R. had left his home with $80 in gold certificates, money he had made from the sale of fat lambs. Carrying around that much money during hard times wasn’t wise, so he started a bank account. When he found out the boarding house residents were willing to sell their scrip to him for half its face value, he put that account to good use. He could afford to wait until the scrip matured.

In his biography, J.R Simplot—A billion the hard way*, by Louie Attebery, Simplot is quoted as saying, “It wasn’t a lotta money, but it was enough to make some money. I’d buy that scrip every month when [they got paid]. They had to pay their board bill…Damn board bill was about half their [salary]. Tough. You talk about tough times; they were tough! Tough, boy! But I accumulated a few hundred dollars, and I made some money.”

He had a lot of stories like that, because spotting a bargain or a deal was his life. Simplot was known as the potato king because his company invented a way to process French fries that caught on just a little bit with companies such as McDonalds. He was big in fertilizer, raising cattle, and funding the development of microchips. The latter proving that he never lost the business acumen that he gained back at that boarding house in Declo.

J.R. Simplot was Idaho’s first billionaire. In 2007 he was the 89th richest person in the United States, with a personal fortune estimated to be about $3.6 billion dollars. When he passed away in 2008 at age 99, Jack Simplot was the oldest billionaire on the Forbes 400 list.

Published on May 20, 2022 04:00

May 19, 2022

Hold the Fries (Tap to read)

Do you want fries with that? Tough.

Hudson’s Hamburgers in Coeur d’Alene has been not selling fries with their hamburgers since 1907. And they do okay. You can get cheese on your hamburger, and you can order a pie for dessert. Just no fries.

Harley Hudson came to Coeur d’Alene from Brooklyn in 1905. The other Brooklyn. The one in Iowa. He sawed timber for a living for a couple of years, then thought the area could benefit from a good, basic burger. He built a rickety little stand out of canvas and boards and began selling hamburgers for a dime on the west end of the Idaho Hotel. He sold a lot of them. In 1910 he moved into a space next to the east end of the hotel that allowed him to have a counter and stools for a dozen customers.

When 1917 rolled around—the ten-year anniversary of Hudson’s Hamburgers—Harley had saved up enough money to buy a two-story brick building on the south side of Sherman Avenue, between Second and Third streets. He promptly named it the Hudson Building. The family operated the business from there until 1962 when they leased the spot to J.C. Penney and moved across the street to their present location, 207 E. Sherman Avenue.

Descendants of Harley Hudson still run the joint today. The menu is about the same as it was in 1907: plenty of burgers, no fries. They’ve been doing the burger thing so long and so well that there just isn’t much point in changing their business formulae. They’ve been named one of the top hamburger spots in the West by Sunset Magazine. The Wall Street Journal, USA Today, and Gourmet Magazine have all featured Hudson’s.

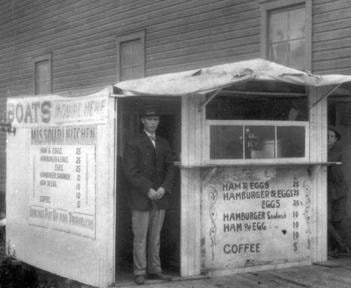

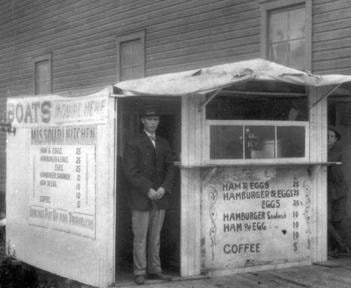

If you’re a history buff—and you probably are, if you’re reading this—stop in and take a look at the framed photos on the walls of big steamers and smaller boats that once plied the nearby waters. Maybe order a hamburger while you’re there. The original Hudsons Hamburgers looked a little different than it does today.

The original Hudsons Hamburgers looked a little different than it does today.

Hudson’s Hamburgers in Coeur d’Alene has been not selling fries with their hamburgers since 1907. And they do okay. You can get cheese on your hamburger, and you can order a pie for dessert. Just no fries.

Harley Hudson came to Coeur d’Alene from Brooklyn in 1905. The other Brooklyn. The one in Iowa. He sawed timber for a living for a couple of years, then thought the area could benefit from a good, basic burger. He built a rickety little stand out of canvas and boards and began selling hamburgers for a dime on the west end of the Idaho Hotel. He sold a lot of them. In 1910 he moved into a space next to the east end of the hotel that allowed him to have a counter and stools for a dozen customers.

When 1917 rolled around—the ten-year anniversary of Hudson’s Hamburgers—Harley had saved up enough money to buy a two-story brick building on the south side of Sherman Avenue, between Second and Third streets. He promptly named it the Hudson Building. The family operated the business from there until 1962 when they leased the spot to J.C. Penney and moved across the street to their present location, 207 E. Sherman Avenue.

Descendants of Harley Hudson still run the joint today. The menu is about the same as it was in 1907: plenty of burgers, no fries. They’ve been doing the burger thing so long and so well that there just isn’t much point in changing their business formulae. They’ve been named one of the top hamburger spots in the West by Sunset Magazine. The Wall Street Journal, USA Today, and Gourmet Magazine have all featured Hudson’s.

If you’re a history buff—and you probably are, if you’re reading this—stop in and take a look at the framed photos on the walls of big steamers and smaller boats that once plied the nearby waters. Maybe order a hamburger while you’re there.

The original Hudsons Hamburgers looked a little different than it does today.

The original Hudsons Hamburgers looked a little different than it does today.

Published on May 19, 2022 04:00

May 18, 2022

An Idaho Connection to a Famous Book (Tap to read)

If you’ve been hanging around Idaho for a few decades paying a little attention to who did what, you’ve run across the name Bowler from time-to-time. There’s Bruce Bowler who was a pioneer conservationist and attorney who pioneered the field of environmental law in Idaho. Drich (short for Aldrich) Bowler was an artist and inventor who hosted the 13-part Idaho Centennial series, produced by Idaho Public Television, "Proceeding on Through a Beautiful Country: A Television History of Idaho." Ned Bowler was a speech/language professor at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

But this is a story about their brother, Holden. Holden was an athlete, a military man, and a business man. He held a state record for high school track in Idaho, retired as a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Reserve, ran a Denver ad agency, and taught environmental education. But it was his passion for singing that gave him a couple of interesting connections to noted contemporary figures.

While going to school at the University of Idaho in the early 1930s, Holden met Thomas Collins. They became good friends over the years, and Holden became godfather to Tom’s daughter Judy Collins, the well-known folksinger.

Singing took Holden to sea. He became the headline singer for a cruise line on a cruise to South America. He met a young man named Jerome who was staff on the ship. They became fast friends. The two toured the towns where the cruise ship stopped and shot the breeze. Jerome told Holden he was a writer. He liked Holden’s unusual first name and told him he would probably use it someday in a story.

When Jerome got around to using Holden’s name, the writer was going just by his first initials, J.D. J.D. Salinger. The author of Catcher in the Rye once wrote to Holden Bowler and said about the character who borrowed his name, “what you like about Holden (Caulfield) is taken from you, and what you don't like about him, I made up.”

Holden Bowler passed his passion for singing on to his daughter, Belinda Bowler, who I’ve heard called “Idaho folk music royalty.”

But this is a story about their brother, Holden. Holden was an athlete, a military man, and a business man. He held a state record for high school track in Idaho, retired as a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Reserve, ran a Denver ad agency, and taught environmental education. But it was his passion for singing that gave him a couple of interesting connections to noted contemporary figures.

While going to school at the University of Idaho in the early 1930s, Holden met Thomas Collins. They became good friends over the years, and Holden became godfather to Tom’s daughter Judy Collins, the well-known folksinger.

Singing took Holden to sea. He became the headline singer for a cruise line on a cruise to South America. He met a young man named Jerome who was staff on the ship. They became fast friends. The two toured the towns where the cruise ship stopped and shot the breeze. Jerome told Holden he was a writer. He liked Holden’s unusual first name and told him he would probably use it someday in a story.

When Jerome got around to using Holden’s name, the writer was going just by his first initials, J.D. J.D. Salinger. The author of Catcher in the Rye once wrote to Holden Bowler and said about the character who borrowed his name, “what you like about Holden (Caulfield) is taken from you, and what you don't like about him, I made up.”

Holden Bowler passed his passion for singing on to his daughter, Belinda Bowler, who I’ve heard called “Idaho folk music royalty.”

Published on May 18, 2022 04:00

May 17, 2022

A Legislative Riot (Tap to read)

The Civil War ended almost two years before a dust-up about it blew into the Idaho Territorial Legislature. This battle-come-lately started out over money. Idaho’s finances in 1867 were in poor shape thanks to mismanagement and malfeasance by a string of federal officials appointed to oversee the territory. So the Legislature decided to cut the salaries of Territorial Governor David Ballard and Territorial Secretary Solomon R. Howlett.

Governor Ballard thought the salary cuts were fair but insisted that the legislators also take a pay cut. They were unhappy with that quid pro quo. Their displeasure grew to the boiling point when the US Secretary of the Treasury Hugh McCulloch insisted that Idaho legislators sign an oath of allegiance to the country to get paid at all. They were to attest that they had never countenanced, nor encouraged, the South during the Civil War.

Most of the legislators were Democrats, many of whom had favored the Confederacy. Secretary Howlett tried to explain things to a joint session of the Legislature on a Friday afternoon. As the Idaho Statesman at the time termed it, “both houses were well described to be a paroxysm of rage.”

The threats of personal violence against the man were so fierce he felt the need for an Army officer to escort him to breakfast on Saturday. That afternoon about 25 of the Legislators dropped by the Secretary’s office to have a chat. Threats flew once again. The more level-headed of the crowd agreed to give Howlett until half-past two to consult with his attorneys before hearing his final answer on the matter.

In—let’s say “discussions”—carried on between lawmakers before the appointed hour, one lawmaker beat another over the head with a revolver to make a point, the essence of which is lost to history.

“Mr. Abbott” jumped on top of a table and shouted for order, saying, “Are we a riotous mob? Or are we sensible men met here peaceably to consult together?”

One could reasonably look at their behavior for a possible answer. During the Friday and Saturday sessions, much of the furniture in the meeting hall was destroyed or carried away. Lamps were thrown out of windows.

When Secretary Howlett returned to his office after consulting with his attorneys, he did not return alone. A squad of infantry lined up in front of the hall. This set off even more protest inside.

Still refusing to pay the men, Howlett heard shouts of “skin him!” and “shake it out of him!” He was now determined not to pay those who had not signed the oath in the days before, even if they reluctantly agreed to sign it now. The crowd lunged for the Secretary with murder in the men’s eyes at one point.

Perhaps that negotiating tactic worked. Howlett agreed to let the men sign the oath and get their pay when the temperature cooled a degree or two.

Had the men held out a couple more days, they could have avoided signing the hated oath. The United States Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional two days after they signed it.

Governor Ballard thought the salary cuts were fair but insisted that the legislators also take a pay cut. They were unhappy with that quid pro quo. Their displeasure grew to the boiling point when the US Secretary of the Treasury Hugh McCulloch insisted that Idaho legislators sign an oath of allegiance to the country to get paid at all. They were to attest that they had never countenanced, nor encouraged, the South during the Civil War.

Most of the legislators were Democrats, many of whom had favored the Confederacy. Secretary Howlett tried to explain things to a joint session of the Legislature on a Friday afternoon. As the Idaho Statesman at the time termed it, “both houses were well described to be a paroxysm of rage.”

The threats of personal violence against the man were so fierce he felt the need for an Army officer to escort him to breakfast on Saturday. That afternoon about 25 of the Legislators dropped by the Secretary’s office to have a chat. Threats flew once again. The more level-headed of the crowd agreed to give Howlett until half-past two to consult with his attorneys before hearing his final answer on the matter.

In—let’s say “discussions”—carried on between lawmakers before the appointed hour, one lawmaker beat another over the head with a revolver to make a point, the essence of which is lost to history.

“Mr. Abbott” jumped on top of a table and shouted for order, saying, “Are we a riotous mob? Or are we sensible men met here peaceably to consult together?”

One could reasonably look at their behavior for a possible answer. During the Friday and Saturday sessions, much of the furniture in the meeting hall was destroyed or carried away. Lamps were thrown out of windows.

When Secretary Howlett returned to his office after consulting with his attorneys, he did not return alone. A squad of infantry lined up in front of the hall. This set off even more protest inside.

Still refusing to pay the men, Howlett heard shouts of “skin him!” and “shake it out of him!” He was now determined not to pay those who had not signed the oath in the days before, even if they reluctantly agreed to sign it now. The crowd lunged for the Secretary with murder in the men’s eyes at one point.

Perhaps that negotiating tactic worked. Howlett agreed to let the men sign the oath and get their pay when the temperature cooled a degree or two.

Had the men held out a couple more days, they could have avoided signing the hated oath. The United States Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional two days after they signed it.

Published on May 17, 2022 04:00

May 16, 2022

Those Hillside Letters (Tap to read)

Time for a little audience participation. Get your cameras ready.

Have you ever given any thought to the big letter on the hills above your town? You know, the A above Arco, the B on Table Rock in Boise, the C on the hillside above Cambridge, etc.

According to Wikipedia, there are at least 35 letters on hillsides in Idaho, and maybe as many as 42. Most of them are the first letter of the town’s name, or a letter representing a local high school sports team. Franklin, the first town founded in Idaho Territory, has its big F, but above that are the numerals 1860 for the year it was founded.

Pocatello had a big concrete I on Red Hill representing Idaho State University for many years. It was placed there in 1927. Travelers going south on I-15 knew it as a Pocatello landmark. But in 2014 it was removed because of the risk of a hillside collapse due to heavy erosion. The fear was that the concrete initial might come crashing down on trail users below.

In the book Quintessential Boise, An Architectural Journey *, by Charles Hummel, Tim Woodward, and others, they say the B on Table Rock above the Old Idaho Penitentiary, was placed there in 1931 by Ward Rolfe, Bob Krummes, Kenneth Robertson, and Simeon Coonrood, who were proud graduates of Boise High. As is the case with many such letters, the rocks often get a coat of paint to make them stand out.

Does your town have a letter? Post a picture in the comments section so we can all get a look. Do you have a story that goes along with the letter? An artifact of aliens, perhaps, or the site of your wedding proposal. Please share that, too.

The F above Idaho's first town, Franklin.

The F above Idaho's first town, Franklin.

Have you ever given any thought to the big letter on the hills above your town? You know, the A above Arco, the B on Table Rock in Boise, the C on the hillside above Cambridge, etc.

According to Wikipedia, there are at least 35 letters on hillsides in Idaho, and maybe as many as 42. Most of them are the first letter of the town’s name, or a letter representing a local high school sports team. Franklin, the first town founded in Idaho Territory, has its big F, but above that are the numerals 1860 for the year it was founded.

Pocatello had a big concrete I on Red Hill representing Idaho State University for many years. It was placed there in 1927. Travelers going south on I-15 knew it as a Pocatello landmark. But in 2014 it was removed because of the risk of a hillside collapse due to heavy erosion. The fear was that the concrete initial might come crashing down on trail users below.

In the book Quintessential Boise, An Architectural Journey *, by Charles Hummel, Tim Woodward, and others, they say the B on Table Rock above the Old Idaho Penitentiary, was placed there in 1931 by Ward Rolfe, Bob Krummes, Kenneth Robertson, and Simeon Coonrood, who were proud graduates of Boise High. As is the case with many such letters, the rocks often get a coat of paint to make them stand out.

Does your town have a letter? Post a picture in the comments section so we can all get a look. Do you have a story that goes along with the letter? An artifact of aliens, perhaps, or the site of your wedding proposal. Please share that, too.

The F above Idaho's first town, Franklin.

The F above Idaho's first town, Franklin.

Published on May 16, 2022 04:00

May 15, 2022

Steam Donkeys (Tap to read)

What would you call a locomotive without wheels? Loggers called them donkeys. About 20 Willamette donkeys, stationary steam engines that made rolls of steel cable spin, operated in the St. Joe drainage at one time. Their purpose was to drag logs off a mountain and into a holding pond where they could be readied for a trip downriver.

Fueled by wood or oil the donkeys turned drums around which 8,000 to 12,000 feet of cable fed. That meant that the donkey puncher (the guy who operated the machine) was usually out of sight of the choker (the man up the mountain rigging the cable around downed trees). To facilitate communication between the donkey puncher and the choker—who might be a mile and-a-half apart—they would run a line all the way back to the steam engine’s whistle. The line was typically in the hands of youngster yet too small for felling trees. He was called the whistle punk. He’d yank on the line a certain number of times when the choker would signal he was ready, or not ready, for the donkey puncher to start rolling in the cable and skidding the logs downhill.

A couple of these old donkeys are still around. The St. Joe Ranger District has built a short hiking trail to one at Marble Creek, called the Hobo Historical Trail, not far from St. Maries. They can give you information how to see it. If you don’t feel like hiking, you can also see one in St. Maries (below), a town very proud of its logging history. In 1958 they rescued one and brought it to a new home on Main in a city park dedicated to that history. You’ll see a statue of John Mullen in the same park, and learn a bit about that famous first road the captain built.

Fueled by wood or oil the donkeys turned drums around which 8,000 to 12,000 feet of cable fed. That meant that the donkey puncher (the guy who operated the machine) was usually out of sight of the choker (the man up the mountain rigging the cable around downed trees). To facilitate communication between the donkey puncher and the choker—who might be a mile and-a-half apart—they would run a line all the way back to the steam engine’s whistle. The line was typically in the hands of youngster yet too small for felling trees. He was called the whistle punk. He’d yank on the line a certain number of times when the choker would signal he was ready, or not ready, for the donkey puncher to start rolling in the cable and skidding the logs downhill.

A couple of these old donkeys are still around. The St. Joe Ranger District has built a short hiking trail to one at Marble Creek, called the Hobo Historical Trail, not far from St. Maries. They can give you information how to see it. If you don’t feel like hiking, you can also see one in St. Maries (below), a town very proud of its logging history. In 1958 they rescued one and brought it to a new home on Main in a city park dedicated to that history. You’ll see a statue of John Mullen in the same park, and learn a bit about that famous first road the captain built.

Published on May 15, 2022 04:00

May 14, 2022

A Diamond-Toothed Smile (Tap to read)

First, let’s concede that there were at least a couple of women who went by the name of Diamond Tooth Lil. One, real name Honora Ornstein, was a vaudeville performer well-known in Klondike Gold Rush days. Her affectation of diamonds included much jewelry and several gold teeth studded with diamonds.

Idaho’s Diamond Tooth Lil was an entertainer and entrepreneur who bounced around the West from Silver City to San Francisco, spending significant time in Boise as a manager of rooming houses which were rumored to offer unadvertised recreational activities. Her birth name was Evelyn Fialla (some sources say Prado was her last name), and she was born in Austria-Hungary in about 1877. She married at least eight times, but the name she preferred to use was her first husband’s surname of Hildegard. Everyone else preferred Diamond Tooth Lil.

Lil loved to tell the story of her life to any reporter who would listen. She often told about her gold right front tooth with the diamond, about 1/3 carat, mounted in the center of it. She won that piece of art from a Reno dentist in a bet on a horse race in 1907. More than once she promised to leave the tooth and its diamond to the Idaho Children’s Home orphanage. What finally happened to it is open to speculation.

Diamond Tooth Lil’s stories were often about the love of her life, Diamond Field Jack. They spent time with each other over the years in Idaho and Nevada. She said he asked her to marry him many times, but she declined. They lost track of each other for 30 years, but reunited briefly at a Las Vegas casino in 1946, and in Los Angeles shortly before his death.

When Diamond Field Jack was struck by a cab in 1946 at age 84, it was Diamond Tooth Lil who alerted the Idaho Statesman. Before his death she reported that he had exonerated the taxi driver, saying, “I just wasn’t looking where I was going.”

She ran an auto court called the Depot Inn on the bench near the Boise Depot, and a hotel at 219 S. Ninth, among other Boise properties. She moved to Los Angeles to retire in 1943, but visited Boise regularly. In 1953 she sent photos and other items to the Boise Chamber of Commerce with a note, “just sending a little momento (sic), so you’ll not forget me.”

There’s little chance Diamond Tooth Lil will be forgotten. Mae West wrote a successful Broadway play called Diamond Lil in 1928, which was turned into a movie called She Done Him Wrong, and was revived on Broadway in 1949. Many say it was inspired by one Diamond Tooth Lil or the other, or perhaps the pair of them.

Lil with a picture of her younger self.

Lil with a picture of her younger self.

Idaho’s Diamond Tooth Lil was an entertainer and entrepreneur who bounced around the West from Silver City to San Francisco, spending significant time in Boise as a manager of rooming houses which were rumored to offer unadvertised recreational activities. Her birth name was Evelyn Fialla (some sources say Prado was her last name), and she was born in Austria-Hungary in about 1877. She married at least eight times, but the name she preferred to use was her first husband’s surname of Hildegard. Everyone else preferred Diamond Tooth Lil.

Lil loved to tell the story of her life to any reporter who would listen. She often told about her gold right front tooth with the diamond, about 1/3 carat, mounted in the center of it. She won that piece of art from a Reno dentist in a bet on a horse race in 1907. More than once she promised to leave the tooth and its diamond to the Idaho Children’s Home orphanage. What finally happened to it is open to speculation.

Diamond Tooth Lil’s stories were often about the love of her life, Diamond Field Jack. They spent time with each other over the years in Idaho and Nevada. She said he asked her to marry him many times, but she declined. They lost track of each other for 30 years, but reunited briefly at a Las Vegas casino in 1946, and in Los Angeles shortly before his death.

When Diamond Field Jack was struck by a cab in 1946 at age 84, it was Diamond Tooth Lil who alerted the Idaho Statesman. Before his death she reported that he had exonerated the taxi driver, saying, “I just wasn’t looking where I was going.”

She ran an auto court called the Depot Inn on the bench near the Boise Depot, and a hotel at 219 S. Ninth, among other Boise properties. She moved to Los Angeles to retire in 1943, but visited Boise regularly. In 1953 she sent photos and other items to the Boise Chamber of Commerce with a note, “just sending a little momento (sic), so you’ll not forget me.”

There’s little chance Diamond Tooth Lil will be forgotten. Mae West wrote a successful Broadway play called Diamond Lil in 1928, which was turned into a movie called She Done Him Wrong, and was revived on Broadway in 1949. Many say it was inspired by one Diamond Tooth Lil or the other, or perhaps the pair of them.

Lil with a picture of her younger self.

Lil with a picture of her younger self.

Published on May 14, 2022 04:00

May 13, 2022

Boise's 7th Street (Tap to read)

If I were to say that 7th Street was the best-known street in Boise, you’d probably have to pause a minute to think just where that is and why some fool thinks it’s famous. You could find it between 6th and 8th streets, but the signs won’t be any help. They all say Capitol Boulevard.

It wasn’t always so.

Boise architect and president of the Boise Civic Improvement Association, Charles Wayland, first proposed turning 7th Street into a grand entrance boulevard to the City of Boise. That was in 1914. The proposal was almost an afterthought to his larger idea of channeling the Boise River. Wayland envisioned “saddle paths, footpaths, and parkways” following the course of the newly controlled river with residential areas opening up in what had been floodways. Does that sound a little like today’s Boise Greenbelt?

It wasn’t until 1925 that city officials began to get serious about building that grand entrance. That was the year the new Boise Depot was built, dominating the skyline on the bench directly in front of the capitol building. Those striking architectural icons just begged to have a mile-long boulevard between them. New York architects Carrere and Hastings who designed the mission–style depot pushed for a grand promenade to visually and physically connect the two buildings. A municipal bond made it all happen, with the completion of the Capitol Boulevard Bridge in 1931.

Keeping the view down Capitol Boulevard free from intruding buildings, business signs, and a tangle of traffic control devices has been a constant struggle ever since. It’s a struggle that hasn’t always been won (I’m looking at you, US Bank building), but keeping a vigilant eye on what happens on the boulevard is worth doing to preserve the city’s “grand promenade.”

Capitol Boulevard from the depot.

Capitol Boulevard from the depot.

It wasn’t always so.

Boise architect and president of the Boise Civic Improvement Association, Charles Wayland, first proposed turning 7th Street into a grand entrance boulevard to the City of Boise. That was in 1914. The proposal was almost an afterthought to his larger idea of channeling the Boise River. Wayland envisioned “saddle paths, footpaths, and parkways” following the course of the newly controlled river with residential areas opening up in what had been floodways. Does that sound a little like today’s Boise Greenbelt?

It wasn’t until 1925 that city officials began to get serious about building that grand entrance. That was the year the new Boise Depot was built, dominating the skyline on the bench directly in front of the capitol building. Those striking architectural icons just begged to have a mile-long boulevard between them. New York architects Carrere and Hastings who designed the mission–style depot pushed for a grand promenade to visually and physically connect the two buildings. A municipal bond made it all happen, with the completion of the Capitol Boulevard Bridge in 1931.

Keeping the view down Capitol Boulevard free from intruding buildings, business signs, and a tangle of traffic control devices has been a constant struggle ever since. It’s a struggle that hasn’t always been won (I’m looking at you, US Bank building), but keeping a vigilant eye on what happens on the boulevard is worth doing to preserve the city’s “grand promenade.”

Capitol Boulevard from the depot.

Capitol Boulevard from the depot.

Published on May 13, 2022 04:00

May 12, 2022

Interviewing Nixon (Tap to Read)

Here’s a little trivia question for you: Who was the first person to interview Richard Nixon live following his resignation?

Walter Cronkite would be a good guess. Paul J. Schneider would be a better one.

Schneider was a Boise Broadcasting icon for some 50 years. He was on TV now and then but is best remembered as the voice of BSU Bronco football for 35 years. He and Lon Dunn also did a legendary two-man morning show on KBOI. He was such a part of that station that they named the building after him when he retired.

But Richard Nixon?

Speaking at an Idaho Broadcast History group gathering Schneider told how that came about. He said that he had been interviewing his friend, baseball Hall of Famer, Harmon Killebrew. Killebrew asked Schneider afterwards if he wanted to go somewhere else in his career. Paul J. said that he was quite happy right where he was. Killebrew pressed him, asking if there was one thing he’d like to do in radio. Schneider answered that he’d like to interview former President Richard Nixon. Killebrew said, “I can make that happen.”

Schneider was skeptical, but a few days later Killebrew called and said he’d set it up. Schneider was to call Nixon on his birthday for the live interview. One condition: No questions about politics.

“So, we had him predict the Super Bowl,” Schneider said.

Newspeople all over the world were eager to get a Nixon interview. Apparently, none of the rest of them knew Harmon Killebrew.

That’s Tom Scott on the left with Nixon interviewer Paul J. Schneider on the right. Photo courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation.

That’s Tom Scott on the left with Nixon interviewer Paul J. Schneider on the right. Photo courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation.

Walter Cronkite would be a good guess. Paul J. Schneider would be a better one.

Schneider was a Boise Broadcasting icon for some 50 years. He was on TV now and then but is best remembered as the voice of BSU Bronco football for 35 years. He and Lon Dunn also did a legendary two-man morning show on KBOI. He was such a part of that station that they named the building after him when he retired.

But Richard Nixon?

Speaking at an Idaho Broadcast History group gathering Schneider told how that came about. He said that he had been interviewing his friend, baseball Hall of Famer, Harmon Killebrew. Killebrew asked Schneider afterwards if he wanted to go somewhere else in his career. Paul J. said that he was quite happy right where he was. Killebrew pressed him, asking if there was one thing he’d like to do in radio. Schneider answered that he’d like to interview former President Richard Nixon. Killebrew said, “I can make that happen.”

Schneider was skeptical, but a few days later Killebrew called and said he’d set it up. Schneider was to call Nixon on his birthday for the live interview. One condition: No questions about politics.

“So, we had him predict the Super Bowl,” Schneider said.

Newspeople all over the world were eager to get a Nixon interview. Apparently, none of the rest of them knew Harmon Killebrew.

That’s Tom Scott on the left with Nixon interviewer Paul J. Schneider on the right. Photo courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation.

That’s Tom Scott on the left with Nixon interviewer Paul J. Schneider on the right. Photo courtesy of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation.

Published on May 12, 2022 04:00

May 11, 2022

Those Confusing Camas Prairies (Tap to Read)

Not that Camas Prairie, the other one

After you’ve topped White Bird Pass, look to your left as you enter the rolling farm country around Grangeville. If you’re there in the early spring you can see patches of blue sometimes so thick they look like rippling ponds. If you’re paying attention you might pull over and read the Idaho Historical Society marker that explains that swatch of color. Camas. The flowering root was a key part of the diet of the Nez Perce.

If you’re a fan of historical markers, you probably already stopped at the one part-way up the steep White Bird grade that marks the beginning of the Nez Perce War. The first shots in that months-long running battle were fired from the top of a low hill as the Indians created a diversion there that allowed Chief Joseph and his people, who were camped on the prairie above, to slip away from soldiers.

When we talk about Camas Prairie, we could be talking about that one. Or we could be talking about the other Camas Prairie near Fairfield. It wasn’t part of the Nez Perce War, but it was the site of a war over the edible bulb itself, just one year later.

Farmers and ranchers were encroaching on land promised to the Bannock Tribe in 1878, and no one took the Tribe’s complaints seriously. The dispute turned into a war when hogs were found rooting in the camas fields. One can imagine the seething anger of the Bannocks when they saw pigs tearing up the plants that had been a staple for them for time beyond memory.

The Indians went on a rampage, stealing cattle and horses, attacking and burning a wagon train, and sinking the ferry at Glenn’s Ferry. The Bannocks joined up with Paiutes pillaging across southeastern Oregon. Troops pursued them and the Indians suffered a final defeat in the Blue Mountains, though small raiding parties trickled back into Idaho stirring up trouble well into the fall.

There’s a historical marker about the Bannock War on U.S. 20 near Hill City.

So, now we know there are two… Wait. There’s ANOTHER historical marker on Idaho 62 between Craigmont and Nez Perce that talks about THAT Camas Prairie. Lalia Boone, in her book Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary, says that “Camas as a place name occurs throughout Idaho,” and doesn’t even bother to count up all the prairies and creeks so named.

If you’re still confused just know that camas is a beautiful flower that has been a key part of the unwritten and written history of this place we call Idaho.

After you’ve topped White Bird Pass, look to your left as you enter the rolling farm country around Grangeville. If you’re there in the early spring you can see patches of blue sometimes so thick they look like rippling ponds. If you’re paying attention you might pull over and read the Idaho Historical Society marker that explains that swatch of color. Camas. The flowering root was a key part of the diet of the Nez Perce.

If you’re a fan of historical markers, you probably already stopped at the one part-way up the steep White Bird grade that marks the beginning of the Nez Perce War. The first shots in that months-long running battle were fired from the top of a low hill as the Indians created a diversion there that allowed Chief Joseph and his people, who were camped on the prairie above, to slip away from soldiers.

When we talk about Camas Prairie, we could be talking about that one. Or we could be talking about the other Camas Prairie near Fairfield. It wasn’t part of the Nez Perce War, but it was the site of a war over the edible bulb itself, just one year later.

Farmers and ranchers were encroaching on land promised to the Bannock Tribe in 1878, and no one took the Tribe’s complaints seriously. The dispute turned into a war when hogs were found rooting in the camas fields. One can imagine the seething anger of the Bannocks when they saw pigs tearing up the plants that had been a staple for them for time beyond memory.

The Indians went on a rampage, stealing cattle and horses, attacking and burning a wagon train, and sinking the ferry at Glenn’s Ferry. The Bannocks joined up with Paiutes pillaging across southeastern Oregon. Troops pursued them and the Indians suffered a final defeat in the Blue Mountains, though small raiding parties trickled back into Idaho stirring up trouble well into the fall.

There’s a historical marker about the Bannock War on U.S. 20 near Hill City.

So, now we know there are two… Wait. There’s ANOTHER historical marker on Idaho 62 between Craigmont and Nez Perce that talks about THAT Camas Prairie. Lalia Boone, in her book Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary, says that “Camas as a place name occurs throughout Idaho,” and doesn’t even bother to count up all the prairies and creeks so named.

If you’re still confused just know that camas is a beautiful flower that has been a key part of the unwritten and written history of this place we call Idaho.

Published on May 11, 2022 04:00