Rick Just's Blog, page 90

July 9, 2022

The Iron Door Mine (Tap to read)

Stories of lost gold abound in Idaho, whether they’re about that mine that a prospector told of with his last dying breath, or stagecoach loot secreted away in some crevice, they usually have just enough detail to make them intriguingly plausible.

The detail that defines the Mine with the Iron Door story is, not surprisingly, that iron door. Before I get into the telling of the Idaho story, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that there are many such stories about lost mines in the Southwest that are hidden behind an iron door. There was a romance called The Mine with the Iron Door written by Harold Bell Right in 1923. It was made into a silent movie the following year, then remade as a talkie in 1934.

Most stories about the lost mine in the Southwest place it in the Santa Catalina Mountains north of Tucson. That mine has been lost a very long time, with the legends dating back to when the Spanish reigned over the region.

But the Mine with the Iron Door we’re concerned about today is allegedly located somewhere on Samaria Mountain near Malad City. The story has something most of the other iron door stories lack, the genesis of the door. It seems a bank in some Utah town—maybe Corinne, which was a major hub in the latter part of the 19th Century—burned down, leaving little that was salvageable, but the iron door used for its vault.

A trio of robbers planning to make off with stagecoach gold acquired that door thinking it would be a fine way to hide their loot. They found a cave on Samaria Mountain—need I say allegedly quite a lot during this telling? Let’s assume you can insert that where it needs to be, which is in approximately every sentence. Anyway, they installed the vault door in this cave, maybe part way down inside it so that the door was hidden.

Now that they had their own private “bank” the robbers did what robbers do. They robbed a stage and took quite a lot of bars of gold or coins or Bitcoins back to Samaria Mountain to secret away in their safe.

Befitting of a lost gold story, the robbers had a row resulting in them shooting each other, every last one. Though all were wounded, one got out and locked his co-conspirators in the cave behind the Iron Door. He found his way to a ranch where, knowing he was on death’s door, he blurted out his story, then stepped through the door at the end of his life, one that was presumably not iron.

But the story gets better. A few years later a young boy found the iron door! He’d heard the story of the robbery and knew he was about to be rich but—isn’t luck always like this?—he got lost himself during a storm. He was found, of course, and told of the iron door, which he was never able to find again.

Thomas J. McDevitt, MD, tells this and many other entertaining stories in his book, Idaho’s Malad Valley, a History . He even reveals the name of the boy, who grew to be a man, then an old man who never tired of telling it. He was known for telling some tall tales as well, but this one was surely true.

Now, that big hunk of iron shouldn’t be so difficult to find today with metal detecting technology constantly improving, and there is no shortage of people willing to try.

But, before you start packing for a trip to Samaria, you might ask yourself this question: Why would anyone go to the trouble of installing a heavy iron door in a cave to hide his loot? Simply hiding the gold in the cave would seem better than putting in a door that all but said, “Break this lock, for behind this door is something of value.”

I should also note that there’s a fair chance you might run into an IRON DOOR AT THE MOUTH OF A CAVE in Idaho (As below). Look closely there’s probably a sign on it that warns it is dangerous to enter unless you are an experienced spelunker. Also, it’s more likely to be a gate than a door, with plenty of room to let bats fly out at night and discover their own treasure.

The detail that defines the Mine with the Iron Door story is, not surprisingly, that iron door. Before I get into the telling of the Idaho story, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that there are many such stories about lost mines in the Southwest that are hidden behind an iron door. There was a romance called The Mine with the Iron Door written by Harold Bell Right in 1923. It was made into a silent movie the following year, then remade as a talkie in 1934.

Most stories about the lost mine in the Southwest place it in the Santa Catalina Mountains north of Tucson. That mine has been lost a very long time, with the legends dating back to when the Spanish reigned over the region.

But the Mine with the Iron Door we’re concerned about today is allegedly located somewhere on Samaria Mountain near Malad City. The story has something most of the other iron door stories lack, the genesis of the door. It seems a bank in some Utah town—maybe Corinne, which was a major hub in the latter part of the 19th Century—burned down, leaving little that was salvageable, but the iron door used for its vault.

A trio of robbers planning to make off with stagecoach gold acquired that door thinking it would be a fine way to hide their loot. They found a cave on Samaria Mountain—need I say allegedly quite a lot during this telling? Let’s assume you can insert that where it needs to be, which is in approximately every sentence. Anyway, they installed the vault door in this cave, maybe part way down inside it so that the door was hidden.

Now that they had their own private “bank” the robbers did what robbers do. They robbed a stage and took quite a lot of bars of gold or coins or Bitcoins back to Samaria Mountain to secret away in their safe.

Befitting of a lost gold story, the robbers had a row resulting in them shooting each other, every last one. Though all were wounded, one got out and locked his co-conspirators in the cave behind the Iron Door. He found his way to a ranch where, knowing he was on death’s door, he blurted out his story, then stepped through the door at the end of his life, one that was presumably not iron.

But the story gets better. A few years later a young boy found the iron door! He’d heard the story of the robbery and knew he was about to be rich but—isn’t luck always like this?—he got lost himself during a storm. He was found, of course, and told of the iron door, which he was never able to find again.

Thomas J. McDevitt, MD, tells this and many other entertaining stories in his book, Idaho’s Malad Valley, a History . He even reveals the name of the boy, who grew to be a man, then an old man who never tired of telling it. He was known for telling some tall tales as well, but this one was surely true.

Now, that big hunk of iron shouldn’t be so difficult to find today with metal detecting technology constantly improving, and there is no shortage of people willing to try.

But, before you start packing for a trip to Samaria, you might ask yourself this question: Why would anyone go to the trouble of installing a heavy iron door in a cave to hide his loot? Simply hiding the gold in the cave would seem better than putting in a door that all but said, “Break this lock, for behind this door is something of value.”

I should also note that there’s a fair chance you might run into an IRON DOOR AT THE MOUTH OF A CAVE in Idaho (As below). Look closely there’s probably a sign on it that warns it is dangerous to enter unless you are an experienced spelunker. Also, it’s more likely to be a gate than a door, with plenty of room to let bats fly out at night and discover their own treasure.

Published on July 09, 2022 04:00

July 8, 2022

Beaver Tails and Beaver Tails (Tap to read)

Idaho has two Malad Rivers, both named such because of encounter early trappers had with bad beavers. No, not juvenile delinquent beavers, or beavers gone rogue because of bad upbringing or the crowd they ran with. These were beavers that were eaten and got their revenge by passing on some malady to the person who feasted on their flesh.

Alexander Ross had the honor of naming Idaho’s Malad River that empties into the Bear River. He called it “River Aux Malades.” He recorded the experience in his journal in the fall of 1824. After breakfast that day many of his men were taken ill—so many that Ross was quite certain it was something they ate. He did a survey of the ailing and the fit and found that those who had partaken of fresh beaver that morning were the former.

Thirty-seven men in his party “were seized with grippings and laid up. The sickness first showed itself in a pain about the kidneys, then the stomach, and afterwards the back of the neck and all the nerves, and by and by the whole system became affected. The sufferers were almost speechless and motionless, having scarcely the power to stir yet suffering great pain, which caused froth about the mouth.”

It's at this point that Ross described the medicine they had on hand in their camp: none. So, of course a leader improvises. “The first thing I applied was gunpowder. Drawing therefore a handful or two of it into a dish of warm water and mixing it up I made them drink strong doses of it.”

The gunpowder smoothie had no positive effect, shockingly. Next he boiled up a kettle of fat and spiced it up with pepper for the ailing to drink. Ross reported that did the trick. Everyone started getting better. A skeptic might think the ailment had simply run its course or the men began to feign improvement for fear of whatever Ross might concoct to pour down their throats next.

The theory Ross came up with was that the beaver, which had little bark in the area to feast on, had ingested some poisonous roots. An Indian they happened upon made them to understand that you could roast the local beaver meat, but if you boiled it, you’d get sick every time.

So, note that in your recipe book. When eating Oneida County beaver, roast, don’t boil. You’re welcome.

Yummy beaver tails. Note that this depiction is of a Canadian pastry, not to be confused with the delicacy you might be tempted to try from either of Idaho’s Malad rivers.

Yummy beaver tails. Note that this depiction is of a Canadian pastry, not to be confused with the delicacy you might be tempted to try from either of Idaho’s Malad rivers.

Alexander Ross had the honor of naming Idaho’s Malad River that empties into the Bear River. He called it “River Aux Malades.” He recorded the experience in his journal in the fall of 1824. After breakfast that day many of his men were taken ill—so many that Ross was quite certain it was something they ate. He did a survey of the ailing and the fit and found that those who had partaken of fresh beaver that morning were the former.

Thirty-seven men in his party “were seized with grippings and laid up. The sickness first showed itself in a pain about the kidneys, then the stomach, and afterwards the back of the neck and all the nerves, and by and by the whole system became affected. The sufferers were almost speechless and motionless, having scarcely the power to stir yet suffering great pain, which caused froth about the mouth.”

It's at this point that Ross described the medicine they had on hand in their camp: none. So, of course a leader improvises. “The first thing I applied was gunpowder. Drawing therefore a handful or two of it into a dish of warm water and mixing it up I made them drink strong doses of it.”

The gunpowder smoothie had no positive effect, shockingly. Next he boiled up a kettle of fat and spiced it up with pepper for the ailing to drink. Ross reported that did the trick. Everyone started getting better. A skeptic might think the ailment had simply run its course or the men began to feign improvement for fear of whatever Ross might concoct to pour down their throats next.

The theory Ross came up with was that the beaver, which had little bark in the area to feast on, had ingested some poisonous roots. An Indian they happened upon made them to understand that you could roast the local beaver meat, but if you boiled it, you’d get sick every time.

So, note that in your recipe book. When eating Oneida County beaver, roast, don’t boil. You’re welcome.

Yummy beaver tails. Note that this depiction is of a Canadian pastry, not to be confused with the delicacy you might be tempted to try from either of Idaho’s Malad rivers.

Yummy beaver tails. Note that this depiction is of a Canadian pastry, not to be confused with the delicacy you might be tempted to try from either of Idaho’s Malad rivers.

Published on July 08, 2022 04:00

July 7, 2022

A Tenuous Connection (Tap to read)

Okay, rock and rollers, we’re going on a little journey today, so buckle in. This will take at least an airplane to get from where we’re starting to where we’re going. Maybe a starship.

Marcus and Narcissa Whitman along with Henry Harmon Spalding were Presbyterian missionaries who were the first people to roll into what is now Idaho. Literally, they had the first set of wheels to enter the country. Four wheels were on a wagon that got them almost to Fort Hall in 1836 before they decided that a cart would work better to cross the desert land. So, they took two wheels off and converted the wagon to a cart.

Books have been written about both sets of missionaries, so we’re going to do just a touch and go with our airplane-cum-starship, saying only that the Spaldings set up the first mission in what would become Idaho at Lapwai, not far from what would become Lewiston. The Whitman’s mission was near Walla Walla. They were murdered by Indians, and, we don’t have time to tell that whole story, so off we go into the air.

From our perch in the metaphorical sky we spot Perrin Beza Whitman, the adopted son, and nephew, of Marcus and Narcissa. He survived the massacre because he was in the Dalles on an errand when it happened. Zooming over the years Perrin Whitman is seen moving to Lapwai in 1863 to work as an interpreter in the Indian schools. In 1883 he and his family moved to Lewiston, where he became a trusted businessman for his remaining years, passing away in 1899.

Here’s where we swoop to pick up the trail of Perrin Whitman’s daughter, Elizabeth Auzella “Lizzie” Whitman, born in 1856. We’re picking up speed, so skipping to 1875 we find Lizzie marrying Harry K. Barnett, a title company executive in Lewiston. Lizzie was a singer, entertaining the community with her voice, and playing guitar and violin as well. No time for a standing ovation, though, because we’re back in the air and following Lizzie’s son, Marcus—no doubt named after the murdered Marcus.

Marcus Barton had a wife, but we’re going too fast to mention her—nearing light speed now. Marcus had a daughter who was named Virginia. Virginia—buckle in tight—met a man named Wilford Wing at the University of Washington where both were students. They married and had some kids, one of whom was named Grace Barnett Wing, born in 1939. The family ended up in Palo Alto, where Grace went to high school before building the nearby city of San Francisco out of rock and roll.

And that’s the Marcus and Narcissa Whitman—and Idaho—connection to Grace Slick, one of rock and roll’s greats and the lead singer of Jefferson Airplane-cum-Jefferson Starship.

Marcus and Narcissa Whitman along with Henry Harmon Spalding were Presbyterian missionaries who were the first people to roll into what is now Idaho. Literally, they had the first set of wheels to enter the country. Four wheels were on a wagon that got them almost to Fort Hall in 1836 before they decided that a cart would work better to cross the desert land. So, they took two wheels off and converted the wagon to a cart.

Books have been written about both sets of missionaries, so we’re going to do just a touch and go with our airplane-cum-starship, saying only that the Spaldings set up the first mission in what would become Idaho at Lapwai, not far from what would become Lewiston. The Whitman’s mission was near Walla Walla. They were murdered by Indians, and, we don’t have time to tell that whole story, so off we go into the air.

From our perch in the metaphorical sky we spot Perrin Beza Whitman, the adopted son, and nephew, of Marcus and Narcissa. He survived the massacre because he was in the Dalles on an errand when it happened. Zooming over the years Perrin Whitman is seen moving to Lapwai in 1863 to work as an interpreter in the Indian schools. In 1883 he and his family moved to Lewiston, where he became a trusted businessman for his remaining years, passing away in 1899.

Here’s where we swoop to pick up the trail of Perrin Whitman’s daughter, Elizabeth Auzella “Lizzie” Whitman, born in 1856. We’re picking up speed, so skipping to 1875 we find Lizzie marrying Harry K. Barnett, a title company executive in Lewiston. Lizzie was a singer, entertaining the community with her voice, and playing guitar and violin as well. No time for a standing ovation, though, because we’re back in the air and following Lizzie’s son, Marcus—no doubt named after the murdered Marcus.

Marcus Barton had a wife, but we’re going too fast to mention her—nearing light speed now. Marcus had a daughter who was named Virginia. Virginia—buckle in tight—met a man named Wilford Wing at the University of Washington where both were students. They married and had some kids, one of whom was named Grace Barnett Wing, born in 1939. The family ended up in Palo Alto, where Grace went to high school before building the nearby city of San Francisco out of rock and roll.

And that’s the Marcus and Narcissa Whitman—and Idaho—connection to Grace Slick, one of rock and roll’s greats and the lead singer of Jefferson Airplane-cum-Jefferson Starship.

Published on July 07, 2022 04:00

July 6, 2022

Goddin's River (Tap to read)

Now, here’s an interesting theory. You’ve probably heard that Idaho’s Lost Rivers (Big and Little) are so named because they disappear into the desert lava, the water eventually finding its way into the vast Snake River Aquifer. That makes sense, and I’m not disputing it, but I ran across a somewhat alternate theory while researching the original name of Lost River.

Antoine Godin (also referred to in some sources as Thyery Goddin), was an Iroquois who was in what would become Idaho with Donald Mackenzie’s fur hunters. They were looking for whatever might grow fur, particularly beaver, for the North West Company out of Montreal. Godin, or Goddin, found what we today call Lost River. He was impressed enough with the area that he gave the valley and river his name, i.e., Godin River and Godin Valley.

According to Lalia Boone’s well-researched book Idaho Place Names, a Geographical Dictionary, when Godin later returned to the area, he couldn’t find the river, thus the name Lost River became popular. Of course, either explanation could be describing the same phenomena.

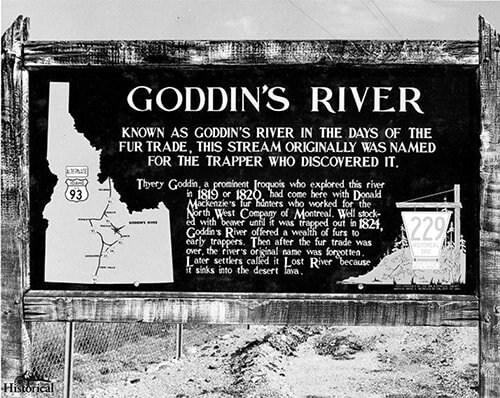

Thanks to Godin’s discovery, the river was trapped out of beaver by 1824. A 1956 photo of the Idaho Historical Marker telling the story of Goddin (or Godin) River. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

A 1956 photo of the Idaho Historical Marker telling the story of Goddin (or Godin) River. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Antoine Godin (also referred to in some sources as Thyery Goddin), was an Iroquois who was in what would become Idaho with Donald Mackenzie’s fur hunters. They were looking for whatever might grow fur, particularly beaver, for the North West Company out of Montreal. Godin, or Goddin, found what we today call Lost River. He was impressed enough with the area that he gave the valley and river his name, i.e., Godin River and Godin Valley.

According to Lalia Boone’s well-researched book Idaho Place Names, a Geographical Dictionary, when Godin later returned to the area, he couldn’t find the river, thus the name Lost River became popular. Of course, either explanation could be describing the same phenomena.

Thanks to Godin’s discovery, the river was trapped out of beaver by 1824.

A 1956 photo of the Idaho Historical Marker telling the story of Goddin (or Godin) River. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

A 1956 photo of the Idaho Historical Marker telling the story of Goddin (or Godin) River. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on July 06, 2022 04:00

July 5, 2022

Idaho's Drowned Towns (Tap to read)

I’ve written about how the citizens of American Falls moved their town to keep it out of the rising waters of the American Falls Reservoir. That took place between 1925 and 1927. I didn’t know that there were two smaller towns inundated by the reservoir, Fort Hall Bottoms and Yuma.

I only know it now thanks to “The Atlas of Drowned Towns,” a project spearheaded by BSU professor of history Bob Reinhardt.

Hundreds of communities in the West were inundated when reservoirs backed up the waters of the rivers alongside which they were built. In Idaho, that included Center, and Van Wyck, both of which went under in 1957 with the construction of the Cascade Dam. Van Wyck had all but merged with the city of Cascade by that time, but much of it went underwater. The name is retained locally in the Van Wyck campground, a part of Lake Cascade State Park.

The C.J. Strike Reservoir, named for Clifford J. Strike, general manager of Idaho Power in the 30s and 40s, drowned the little town of Comet and a place sometimes called Garnet and sometimes called Halls Ferry. That was in 1952.

The town of pine went under in 1950 when Anderson Ranch Reservoir filled.

The most recent submerging of towns was in 1966. The Dworshak Dam took Dent and Big Island off the maps. Dent is now the name of a campground on the lake in Dworshak State Park.

All these drowned towns made way for hydroelectric and irrigation progress. They bring to mind at least two other towns that disappeared. Roosevelt was inundated because of an accidental dam. Most of the site of Morristown lies beneath Alexander Reservoir near Soda Springs, but the town ceased to exist years earlier.

Do you know of other drowned towns? Professor Reinhardt would like to know about them for the Atlas of Drowned Towns.

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive, is of a two-story cement block building being moved to higher ground in 1925.

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive, is of a two-story cement block building being moved to higher ground in 1925.

I only know it now thanks to “The Atlas of Drowned Towns,” a project spearheaded by BSU professor of history Bob Reinhardt.

Hundreds of communities in the West were inundated when reservoirs backed up the waters of the rivers alongside which they were built. In Idaho, that included Center, and Van Wyck, both of which went under in 1957 with the construction of the Cascade Dam. Van Wyck had all but merged with the city of Cascade by that time, but much of it went underwater. The name is retained locally in the Van Wyck campground, a part of Lake Cascade State Park.

The C.J. Strike Reservoir, named for Clifford J. Strike, general manager of Idaho Power in the 30s and 40s, drowned the little town of Comet and a place sometimes called Garnet and sometimes called Halls Ferry. That was in 1952.

The town of pine went under in 1950 when Anderson Ranch Reservoir filled.

The most recent submerging of towns was in 1966. The Dworshak Dam took Dent and Big Island off the maps. Dent is now the name of a campground on the lake in Dworshak State Park.

All these drowned towns made way for hydroelectric and irrigation progress. They bring to mind at least two other towns that disappeared. Roosevelt was inundated because of an accidental dam. Most of the site of Morristown lies beneath Alexander Reservoir near Soda Springs, but the town ceased to exist years earlier.

Do you know of other drowned towns? Professor Reinhardt would like to know about them for the Atlas of Drowned Towns.

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive, is of a two-story cement block building being moved to higher ground in 1925.

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive, is of a two-story cement block building being moved to higher ground in 1925.

Published on July 05, 2022 04:00

July 4, 2022

Happy Fourth of July (Tap to read)

The Fourth of July has been celebrated in Idaho at least since July 4, 1861 when workers building the Mullan Road paused in their labors to celebrate. They marked the occasion by carving “M.R. 1861” on the trunk of a 250-year-old white pine on top of what would become to be known as Fourth of July Pass. “M.R.” could have stood for Mullan Road, as it is most often referred to today, but the initials meant Military Road. The tree where the men carved those initials stood until 1988 when it was split by a lightning strike. What was left of the trunk continued to mark the spot for several years, but continuing vandalism to the tree prompted authorities to cut the carving out of the trunk. You can see it today at the Museum of North Idaho in Coeur d’Alene.

Celebrations went on informally in the early days of the territory, often consisting of an Independence Day Ball, a picnic, street games, and perhaps a little drinking. It wasn’t until 1870 that Congress declared the Fourth of July a national holiday. In 1938 they went a step further and declared it a paid federal holiday.

Street games, by the way, were mainly races. They held sack races, foot races, and bicycle races. In 1886 they had something called “target practice” on the streets of Boise. Contestants were blind-folded and given a brace and bit—a hand operated drill. It is unclear all these years later exactly what they were supposed to do with it. There was a target 50 feet away and the winner was the one who came closest to the bullseye. One wonders if they were to throw the tool, or stumble forward blind-folded trying to find the target and drill a hole in it.

That same Fourth you might have won $2.50 for being the fastest to climb a greased pole. You could also win money by throwing a heavy hammer the farthest or by coming in first in the blindfold wheelbarrow race.

In 1890 the Fourth of July was going to be special. Word had made its way by telegraph that Congress had passed the statehood act for Idaho. The speculation was whether President Benjamin Harrison would sign it on the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, or maybe even the 5th. As it turned out, the pen hit the paper on July 3rd, now known as Statehood Day in Idaho.

That 1890 parade featured a “Ship of State,” a float decked out as a large ship on wheels “gaily decorated with National colors, manned by a gallant crew of Boise youths.” It was followed by a float displaying the wealth of the new state, loaded down gold, silver, copper, and lead ores. Then came five huge saw logs pulled by powerful horses. The Coffin Brothers had a tin shop on wheels “going full blast.”

Miss Carrie Mobley rode in a Car of Liberty to personify the Territory of Idaho. She had not yet heard that Idaho was a state. Governor Shoup brought her up on a stage and addressed her as the newly formed state and informed her of the great change that had occurred. He made this point by removing a sash draped on one of her shoulders that read “Idaho” and replacing it with on that said in larger letters, “State of Idaho.”

Enjoy the day however you’re going to celebrate it.

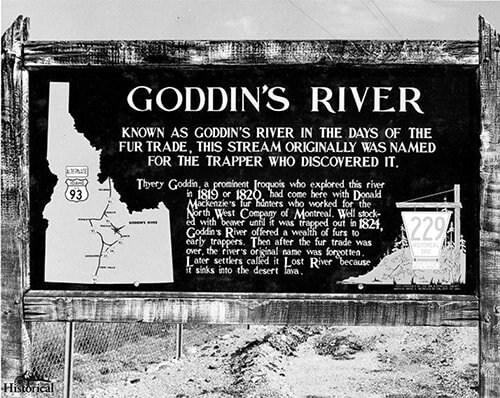

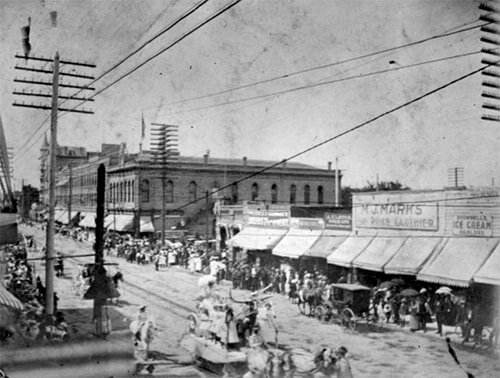

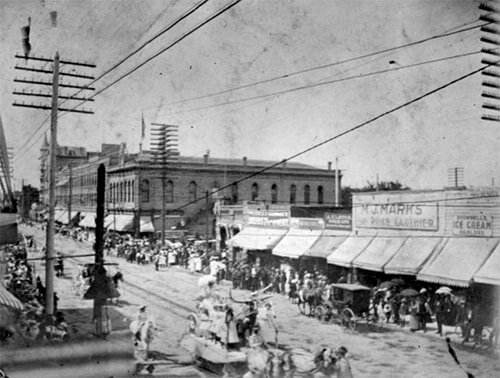

A fuzzy Fourth of July picture from 1880, the Boise Parade, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

A fuzzy Fourth of July picture from 1880, the Boise Parade, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Celebrations went on informally in the early days of the territory, often consisting of an Independence Day Ball, a picnic, street games, and perhaps a little drinking. It wasn’t until 1870 that Congress declared the Fourth of July a national holiday. In 1938 they went a step further and declared it a paid federal holiday.

Street games, by the way, were mainly races. They held sack races, foot races, and bicycle races. In 1886 they had something called “target practice” on the streets of Boise. Contestants were blind-folded and given a brace and bit—a hand operated drill. It is unclear all these years later exactly what they were supposed to do with it. There was a target 50 feet away and the winner was the one who came closest to the bullseye. One wonders if they were to throw the tool, or stumble forward blind-folded trying to find the target and drill a hole in it.

That same Fourth you might have won $2.50 for being the fastest to climb a greased pole. You could also win money by throwing a heavy hammer the farthest or by coming in first in the blindfold wheelbarrow race.

In 1890 the Fourth of July was going to be special. Word had made its way by telegraph that Congress had passed the statehood act for Idaho. The speculation was whether President Benjamin Harrison would sign it on the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, or maybe even the 5th. As it turned out, the pen hit the paper on July 3rd, now known as Statehood Day in Idaho.

That 1890 parade featured a “Ship of State,” a float decked out as a large ship on wheels “gaily decorated with National colors, manned by a gallant crew of Boise youths.” It was followed by a float displaying the wealth of the new state, loaded down gold, silver, copper, and lead ores. Then came five huge saw logs pulled by powerful horses. The Coffin Brothers had a tin shop on wheels “going full blast.”

Miss Carrie Mobley rode in a Car of Liberty to personify the Territory of Idaho. She had not yet heard that Idaho was a state. Governor Shoup brought her up on a stage and addressed her as the newly formed state and informed her of the great change that had occurred. He made this point by removing a sash draped on one of her shoulders that read “Idaho” and replacing it with on that said in larger letters, “State of Idaho.”

Enjoy the day however you’re going to celebrate it.

A fuzzy Fourth of July picture from 1880, the Boise Parade, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

A fuzzy Fourth of July picture from 1880, the Boise Parade, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on July 04, 2022 04:00

July 3, 2022

Astronauts in Idaho (Tap to read)

So, where do you go if you want to give astronauts a crash course in lunar geology? Idaho, of course. It’s not called Craters of the Moon for nothing!

Just a few weeks after Neil Armstrong made that famous boot print on the moon, NASA astronauts Alan Shepard, Gene Cernan, Ed Mitchell, and Joe Engle took a trip to Idaho’s moon-like national monument to do a little exploring. All were highly educated men who had gone through rigorous training to become astronauts. Cernan had even been to the moon already, though he didn’t get to set foot there. He was the lunar module pilot for Apollo 10, which was a dress rehearsal swing around our natural satellite that did not include a landing.

Educated though the astronauts were, none of them were geologists. NASA wanted to give them a little hands-on training on rock gathering and how to identify various volcanic features. These atypical tourists only spent a day at Craters of the Moon, on August 22, 1969.

Shepard went on to command Apollo 14, becoming the fifth person to set foot on the moon. Ed Mitchell was stepper number six. Gene Cernan went to the moon a couple of times and spent more time there than anyone else. He was also the last man to walk on the moon when he commanded Apollo 17. Engle didn’t make it to the moon, but he did make it back to Craters of the Moon. He, Mitchell, and Cernan all came back to participate in the park’s 75th anniversary celebration in 1999. Alan Shepard had passed away from leukemia in 1998.

By the way, the lunar astronauts did bring back some rocks; 842 pounds of them all told. They’re pricey little bits. A federal judge set their value at $50,800 per gram based on what it cost the federal government to go get them. That came up in a case where someone was trying to make some unauthorized sales of moon rocks.

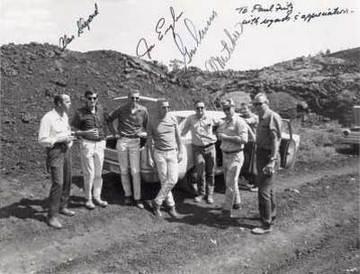

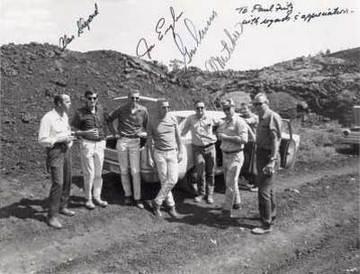

Astronauts at Craters of the Moon National Monument, August 22, 1969. The signatures (from left to right) are: Alan Shepard, Joe Engle, Gene Cernan, and Ed Mitchell. NPS photo.

Astronauts at Craters of the Moon National Monument, August 22, 1969. The signatures (from left to right) are: Alan Shepard, Joe Engle, Gene Cernan, and Ed Mitchell. NPS photo.

Just a few weeks after Neil Armstrong made that famous boot print on the moon, NASA astronauts Alan Shepard, Gene Cernan, Ed Mitchell, and Joe Engle took a trip to Idaho’s moon-like national monument to do a little exploring. All were highly educated men who had gone through rigorous training to become astronauts. Cernan had even been to the moon already, though he didn’t get to set foot there. He was the lunar module pilot for Apollo 10, which was a dress rehearsal swing around our natural satellite that did not include a landing.

Educated though the astronauts were, none of them were geologists. NASA wanted to give them a little hands-on training on rock gathering and how to identify various volcanic features. These atypical tourists only spent a day at Craters of the Moon, on August 22, 1969.

Shepard went on to command Apollo 14, becoming the fifth person to set foot on the moon. Ed Mitchell was stepper number six. Gene Cernan went to the moon a couple of times and spent more time there than anyone else. He was also the last man to walk on the moon when he commanded Apollo 17. Engle didn’t make it to the moon, but he did make it back to Craters of the Moon. He, Mitchell, and Cernan all came back to participate in the park’s 75th anniversary celebration in 1999. Alan Shepard had passed away from leukemia in 1998.

By the way, the lunar astronauts did bring back some rocks; 842 pounds of them all told. They’re pricey little bits. A federal judge set their value at $50,800 per gram based on what it cost the federal government to go get them. That came up in a case where someone was trying to make some unauthorized sales of moon rocks.

Astronauts at Craters of the Moon National Monument, August 22, 1969. The signatures (from left to right) are: Alan Shepard, Joe Engle, Gene Cernan, and Ed Mitchell. NPS photo.

Astronauts at Craters of the Moon National Monument, August 22, 1969. The signatures (from left to right) are: Alan Shepard, Joe Engle, Gene Cernan, and Ed Mitchell. NPS photo.

Published on July 03, 2022 04:00

July 2, 2022

The River that doesn't go to Sea (Tap to read)

People seem to love superlatives. You know, the first, the biggest, the best. Bear River holds a few distinctions like that.

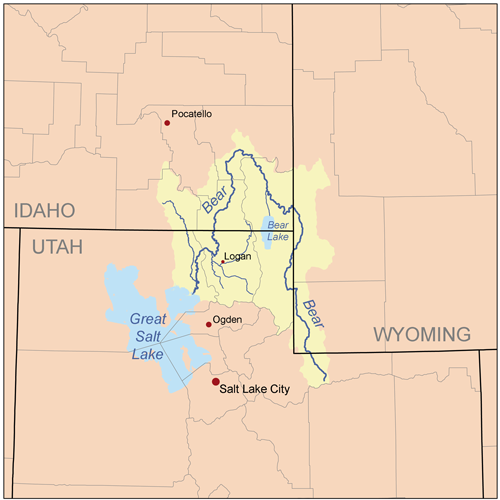

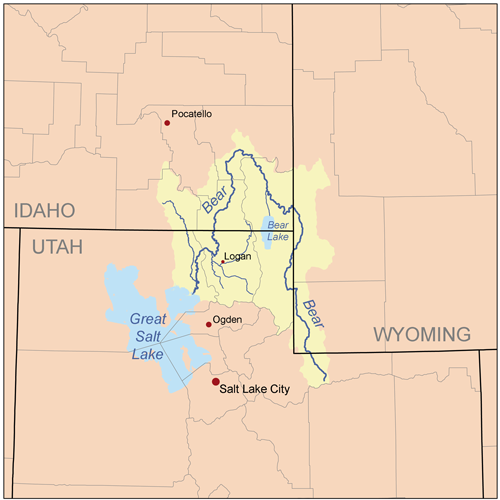

First, though it is probably not unique in this sense, the Bear River flows through three states, Utah, Wyoming, and Idaho. It starts in Utah, winds into Wyoming, drifts back into Utah, then into Wyoming again, before entering Idaho. The longest stretch of the river is in Idaho, looping up past Montpelier to Soda Springs, then plunging down and back into Utah, where it flows into the Great Salt Lake.

That’s where its one, true superlative comes from. The Bear River is the largest river in the United States whose waters never reach an ocean. The outflow of the river is less than 100 miles from where it began, but the water journeys some 350 miles to get there.

It wasn’t always so. The Bear River once—geologically once—flowed into the Snake River like most other respectable streams in southern Idaho. Lava flows that occurred long before you were born—maybe before anyone was born—diverted the flow south from Soda Springs.

Kmusser [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)]

Kmusser [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)]

First, though it is probably not unique in this sense, the Bear River flows through three states, Utah, Wyoming, and Idaho. It starts in Utah, winds into Wyoming, drifts back into Utah, then into Wyoming again, before entering Idaho. The longest stretch of the river is in Idaho, looping up past Montpelier to Soda Springs, then plunging down and back into Utah, where it flows into the Great Salt Lake.

That’s where its one, true superlative comes from. The Bear River is the largest river in the United States whose waters never reach an ocean. The outflow of the river is less than 100 miles from where it began, but the water journeys some 350 miles to get there.

It wasn’t always so. The Bear River once—geologically once—flowed into the Snake River like most other respectable streams in southern Idaho. Lava flows that occurred long before you were born—maybe before anyone was born—diverted the flow south from Soda Springs.

Kmusser [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)]

Kmusser [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)]

Published on July 02, 2022 04:00

July 1, 2022

Body Records (Tap to read)

First, don’t read this if you’re squeamish. Second, I know you’re still reading whether you’re squeamish or not because I’ve piqued your interest.

There are no rules in journalism about how a writer is supposed report on the discovery of a body. There are, however, conventions. Today, for instance, a reporter is not likely to give an elaborately detailed description of the recovery of the body, in respect for the relatives of the deceased if for no other reason.

Not so, apparently, in 1915. While researching a sensational kidnapping that took place that year in Bingham County, I noticed a story in The Idaho Republican headlined “Kleinschmidt’s Body is Found.” It caught my attention because the name reminded me of an Idaho place name, Kleinschmidt Grade in Hells Canyon. I read enough to see that there was no connection—just enough to “hook me in.” And, you don’t even know that’s a pun yet.

Although the story had a note about the funeral of William Kleinschmidt, it did not mention how he had died. From context, he drowned in the Snake River. The story mainly concerned itself with the remarkably short amount of time it took to find Kleinschmidt’s body, then went on to ponder about the length of time it had taken to find other bodies in the river over the preceding 30 years.

The body was discovered in a near record 53 hours. It was apparently more common to find a body after it had been in the water “nine days which marks a change in the weight of the body,” causing it to float.

“The means employed to find the body was a rope stretched across the stream, with floats to keep it from sinking in the stream and lines nine feet long dropping into the water with sinkers and hooks at the ends.” When anything heavy was encountered, the lines would quiver, and the men would pull up whatever the hook had snagged. This included a 50-pound lava rock that had a hole in it situated just right for the hook.

After describing exactly how and where the body was found in the river—face down, feet downstream, “the face only slightly marked by contact with moss and sand and gravel”—the reporter talked about the records that his readers were, no doubt, wondering about. “Vigils for lost bodies have usually covered a period varying from nine to 600 days. The longest period recorded was about 22 months in the case of George Neal, and the shortest was about one hour in the case of John Loveridge.”

In a mood for reminiscing, the reporter went through the details of the Loveridge drowning of 1890 or 1891, complete with a report on how the family of the man was doing all these years later. They had moved to Utah.

The paper noted that in 1912, one of Loveridge’s sons had come to Blackfoot searching for his father’s grave so he could put some flowers on it. In spite of the fact that Mr. Loveridge held the record for Fastest Recovery of a Body from the Snake River, which should surely have warranted a plaque, no one could find the man’s grave.

There are no rules in journalism about how a writer is supposed report on the discovery of a body. There are, however, conventions. Today, for instance, a reporter is not likely to give an elaborately detailed description of the recovery of the body, in respect for the relatives of the deceased if for no other reason.

Not so, apparently, in 1915. While researching a sensational kidnapping that took place that year in Bingham County, I noticed a story in The Idaho Republican headlined “Kleinschmidt’s Body is Found.” It caught my attention because the name reminded me of an Idaho place name, Kleinschmidt Grade in Hells Canyon. I read enough to see that there was no connection—just enough to “hook me in.” And, you don’t even know that’s a pun yet.

Although the story had a note about the funeral of William Kleinschmidt, it did not mention how he had died. From context, he drowned in the Snake River. The story mainly concerned itself with the remarkably short amount of time it took to find Kleinschmidt’s body, then went on to ponder about the length of time it had taken to find other bodies in the river over the preceding 30 years.

The body was discovered in a near record 53 hours. It was apparently more common to find a body after it had been in the water “nine days which marks a change in the weight of the body,” causing it to float.

“The means employed to find the body was a rope stretched across the stream, with floats to keep it from sinking in the stream and lines nine feet long dropping into the water with sinkers and hooks at the ends.” When anything heavy was encountered, the lines would quiver, and the men would pull up whatever the hook had snagged. This included a 50-pound lava rock that had a hole in it situated just right for the hook.

After describing exactly how and where the body was found in the river—face down, feet downstream, “the face only slightly marked by contact with moss and sand and gravel”—the reporter talked about the records that his readers were, no doubt, wondering about. “Vigils for lost bodies have usually covered a period varying from nine to 600 days. The longest period recorded was about 22 months in the case of George Neal, and the shortest was about one hour in the case of John Loveridge.”

In a mood for reminiscing, the reporter went through the details of the Loveridge drowning of 1890 or 1891, complete with a report on how the family of the man was doing all these years later. They had moved to Utah.

The paper noted that in 1912, one of Loveridge’s sons had come to Blackfoot searching for his father’s grave so he could put some flowers on it. In spite of the fact that Mr. Loveridge held the record for Fastest Recovery of a Body from the Snake River, which should surely have warranted a plaque, no one could find the man’s grave.

Published on July 01, 2022 04:00

June 30, 2022

Pop Quiz (Tap to read)

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture. If you missed that story, click the letter for a link.

1). What entry won the Boise war bond contest to name a B-17 in 1942?

A. Ada’s Victory Bondadier

B. Adavenger

C. Cruis-Ada

D. Esto Perpetua

E. Arrowrock Whizz Bang

2). What happened to the Columbian Liberty Bell?

A. It was melted down during the Bolshevik revolution

B. It went on permanent display in San Francisco

C. It was melted down to make miniature souvenir bells

D. It went on permanent display in Chicago

E. It was melted down and became part of the USS Boise

3). What happened to Steamboat Spring?

A. It was capped and put on a timer so it goes off every hour

B. It was piped into a plant to make Idanha bottled water

C. It dried up

D. It was drowned by the Alexander Reservoir

E. It became the main feature of a park in Soda Springs

4). What did Ralph Dixey give his wife in 1919?

A. A Stutz Bearcat roadster

B. An Appaloosa horse

C. A pinto pony

D. A beaded white leather dress

E. A quarter horse

5) What distinction does Boise’s Columbian Club hold?

A. It was the first Columbian Club ever formed

B. It had the largest membership of any Columbian Club in the country

C. Writer Carol Ryrie Brinks was its first president

D. Writer and artist Mary Hallock Foote was its first president

E. It is the only Columbian Club to still exist

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

1, B

2, A

3, D

4, A

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). What entry won the Boise war bond contest to name a B-17 in 1942?

A. Ada’s Victory Bondadier

B. Adavenger

C. Cruis-Ada

D. Esto Perpetua

E. Arrowrock Whizz Bang

2). What happened to the Columbian Liberty Bell?

A. It was melted down during the Bolshevik revolution

B. It went on permanent display in San Francisco

C. It was melted down to make miniature souvenir bells

D. It went on permanent display in Chicago

E. It was melted down and became part of the USS Boise

3). What happened to Steamboat Spring?

A. It was capped and put on a timer so it goes off every hour

B. It was piped into a plant to make Idanha bottled water

C. It dried up

D. It was drowned by the Alexander Reservoir

E. It became the main feature of a park in Soda Springs

4). What did Ralph Dixey give his wife in 1919?

A. A Stutz Bearcat roadster

B. An Appaloosa horse

C. A pinto pony

D. A beaded white leather dress

E. A quarter horse

5) What distinction does Boise’s Columbian Club hold?

A. It was the first Columbian Club ever formed

B. It had the largest membership of any Columbian Club in the country

C. Writer Carol Ryrie Brinks was its first president

D. Writer and artist Mary Hallock Foote was its first president

E. It is the only Columbian Club to still exist

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)1, B

2, A

3, D

4, A

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on June 30, 2022 04:00