Rick Just's Blog, page 84

September 7, 2022

Early Ear Worms (Tap to read)

And now, something completely different. It’s our first audio oriented post, thanks to Art Gregory of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation.

If you were listening to radio in the 1960s in the Treasure Valley, you might remember the commercials from this short sample, featuring: Frosty Dog!Black Forrest Archery CenterYoung’s Dairy All Jersey MilkBank of IdahoIdaho First National BankWestern Idaho State Fair And, here’s the KIDO City of Trees jingle from 1961, featuring Gib Hochstrasser and Jeanie Hackett, cum Hochstrasser.

In 1962, KFXD had a song about the city where the station was located, which might have been called, Nampa-Nampa. Or, once you’ve heard it, you may think of something to call it yourself. Be kind.

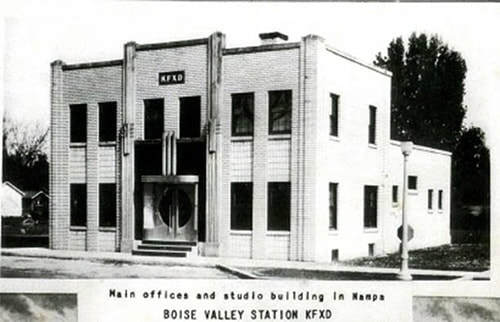

If you like broadcasting history, consider giving a little money to the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation. They’re creating a museum in the old KFXD building in Nampa. They’ve got a ton of memorabilia to display, and they’re hoping include recording studios. That’s the old KFXD building below. I looks much the same today.If you like broadcasting history, consider giving a little money to the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation. They’re creating a museum in the old KFXD building in Nampa. They’ve got a ton of memorabilia to display, and they’re hoping include recording studios. That’s the old KFXD building below. I looks much the same today.And finally, from 1978, KFXD’s I’ve Got a Song to Sing jingle, just a tad reminiscent of Coke jingles of the time.

If you like broadcasting history, consider giving a little money to the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation. They’re creating a museum in the old KFXD building in Nampa. They’ve got a ton of memorabilia to display, and they’re hoping include recording studios. That’s the old KFXD building below. I looks much the same today.

If you were listening to radio in the 1960s in the Treasure Valley, you might remember the commercials from this short sample, featuring: Frosty Dog!Black Forrest Archery CenterYoung’s Dairy All Jersey MilkBank of IdahoIdaho First National BankWestern Idaho State Fair And, here’s the KIDO City of Trees jingle from 1961, featuring Gib Hochstrasser and Jeanie Hackett, cum Hochstrasser.

In 1962, KFXD had a song about the city where the station was located, which might have been called, Nampa-Nampa. Or, once you’ve heard it, you may think of something to call it yourself. Be kind.

If you like broadcasting history, consider giving a little money to the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation. They’re creating a museum in the old KFXD building in Nampa. They’ve got a ton of memorabilia to display, and they’re hoping include recording studios. That’s the old KFXD building below. I looks much the same today.If you like broadcasting history, consider giving a little money to the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation. They’re creating a museum in the old KFXD building in Nampa. They’ve got a ton of memorabilia to display, and they’re hoping include recording studios. That’s the old KFXD building below. I looks much the same today.And finally, from 1978, KFXD’s I’ve Got a Song to Sing jingle, just a tad reminiscent of Coke jingles of the time.

If you like broadcasting history, consider giving a little money to the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation. They’re creating a museum in the old KFXD building in Nampa. They’ve got a ton of memorabilia to display, and they’re hoping include recording studios. That’s the old KFXD building below. I looks much the same today.

Published on September 07, 2022 04:00

September 6, 2022

The Second Fort Hall (Tap to read)

If you’ve lived in Idaho for a while, you’ve probably been confused at least a couple of times when someone made a reference to Fort Hall. Did they mean the reservation, the town, or the fort? If they meant the fort, one could certainly ask, which fort?

Fort Hall began as a fur trading post in 1834. It was located on the Snake River in what is now Bannock County, about 11 miles west of the town of Fort Hall. It served trappers, then Oregon Trail emigrants, and finally stagecoaches and freighters until it was largely destroyed by a flood in 1863, the year Idaho became a territory.

In May 1870, the US began to build a military fort not far from Blackfoot where Lincoln Creek—a warm water stream—flows into the Blackfoot River, some 40 miles east of the original fur trading site. Its purpose was to “maintain proper control” of some 1200 Indians who then resided on the reservation.

The post, situated on 640 acres, was surrounded by grassy fields, providing ample grazing. There were few trees in the area and none really suited for construction, so the bulk of the timber was shipped in from Truckee River, California, with the remainder of the sawed lumber coming from Corrine, Utah.

If you picture a fort as, well, fortified, you don’t have Fort Hall in mind. Without walls, perimeter wooden buildings arranged around a parade ground defined the installation. Most of the major buildings were put up in 1871.

The fort included a hospital, a commissary building, officer’s quarters, a company barrack, married soldier’s quarters, a guard house, a kitchen, and a mess hall. Ancillary buildings included a blacksmith shop, a carpenter shop, two stables, two granaries, a wagon shed, a harness shop, a saddler’s shop, an icehouse, and a barber shop. Of particular interest to my family was the post bakery, where Emma Bennett (soon to be Emma Just) baked bread for the soldiers.

The military Fort Hall lasted until 1883 when the army abandoned it. The federal government transferred the land to the Bureau of Indian Affairs for use as a residential Indian school. Such schools, which attempted to immerse the indigenous children in white culture, were notoriously brutal. The school on the grounds of the old military fort was as bad as any. Students were torn from their families and forced to attend. Funding was low, so little actual teaching took place. Packed together in unsafe and unsanitary conditions the students were prone to disease. A scarlet fever epidemic in 1891 killed ten of them. There were at least two suicides at the school.

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 brought an end to the boarding schools and their policies of forced assimilation. As a result of that act the Lincoln Creek Day School, just a couple of miles from the Fort Hall site, was opened in 1937. It and a couple of other day schools on the reservation were a huge improvement over the boarding school. Kids returned to their families every afternoon. The day school operated only until 1944 when reservation students began attending local public schools.

Both the military Fort Hall site and the Lincoln Creek Day School are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. No buildings from the fort remain on the site. In recent years much work has been done on the nearby school to turn it into a community center for that part of the reservation.

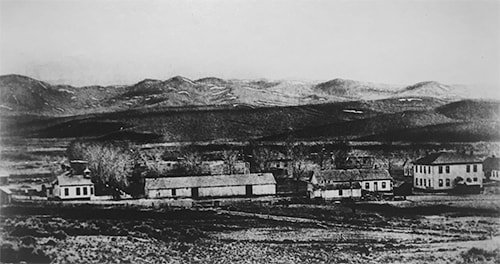

Fort Hall on Lincoln Creek in 1896. By this time the military had left. It had become a boarding school for Native American children. Photo courtesy of the Bannock County Museum and the Idaho State Historical Society.

Fort Hall on Lincoln Creek in 1896. By this time the military had left. It had become a boarding school for Native American children. Photo courtesy of the Bannock County Museum and the Idaho State Historical Society.

Fort Hall began as a fur trading post in 1834. It was located on the Snake River in what is now Bannock County, about 11 miles west of the town of Fort Hall. It served trappers, then Oregon Trail emigrants, and finally stagecoaches and freighters until it was largely destroyed by a flood in 1863, the year Idaho became a territory.

In May 1870, the US began to build a military fort not far from Blackfoot where Lincoln Creek—a warm water stream—flows into the Blackfoot River, some 40 miles east of the original fur trading site. Its purpose was to “maintain proper control” of some 1200 Indians who then resided on the reservation.

The post, situated on 640 acres, was surrounded by grassy fields, providing ample grazing. There were few trees in the area and none really suited for construction, so the bulk of the timber was shipped in from Truckee River, California, with the remainder of the sawed lumber coming from Corrine, Utah.

If you picture a fort as, well, fortified, you don’t have Fort Hall in mind. Without walls, perimeter wooden buildings arranged around a parade ground defined the installation. Most of the major buildings were put up in 1871.

The fort included a hospital, a commissary building, officer’s quarters, a company barrack, married soldier’s quarters, a guard house, a kitchen, and a mess hall. Ancillary buildings included a blacksmith shop, a carpenter shop, two stables, two granaries, a wagon shed, a harness shop, a saddler’s shop, an icehouse, and a barber shop. Of particular interest to my family was the post bakery, where Emma Bennett (soon to be Emma Just) baked bread for the soldiers.

The military Fort Hall lasted until 1883 when the army abandoned it. The federal government transferred the land to the Bureau of Indian Affairs for use as a residential Indian school. Such schools, which attempted to immerse the indigenous children in white culture, were notoriously brutal. The school on the grounds of the old military fort was as bad as any. Students were torn from their families and forced to attend. Funding was low, so little actual teaching took place. Packed together in unsafe and unsanitary conditions the students were prone to disease. A scarlet fever epidemic in 1891 killed ten of them. There were at least two suicides at the school.

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 brought an end to the boarding schools and their policies of forced assimilation. As a result of that act the Lincoln Creek Day School, just a couple of miles from the Fort Hall site, was opened in 1937. It and a couple of other day schools on the reservation were a huge improvement over the boarding school. Kids returned to their families every afternoon. The day school operated only until 1944 when reservation students began attending local public schools.

Both the military Fort Hall site and the Lincoln Creek Day School are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. No buildings from the fort remain on the site. In recent years much work has been done on the nearby school to turn it into a community center for that part of the reservation.

Fort Hall on Lincoln Creek in 1896. By this time the military had left. It had become a boarding school for Native American children. Photo courtesy of the Bannock County Museum and the Idaho State Historical Society.

Fort Hall on Lincoln Creek in 1896. By this time the military had left. It had become a boarding school for Native American children. Photo courtesy of the Bannock County Museum and the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on September 06, 2022 04:00

September 5, 2022

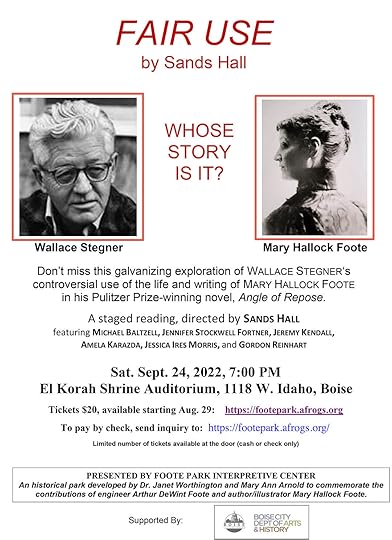

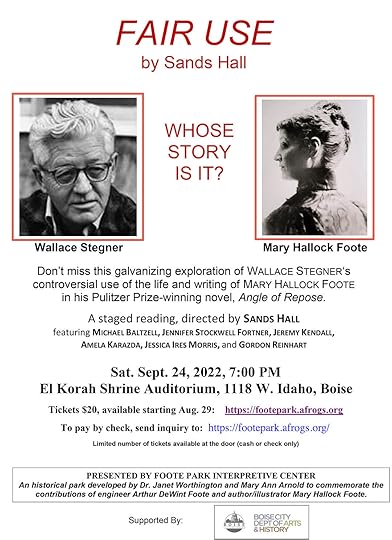

Fair Use (Tap to read)

Mary Hallock Foote was a somewhat reluctant Idahoan. Her husband, Arthur DeWint Foote, was the engineer who designed the canal system that made the Treasure Valley come to life. Wallace Stegner is the man who wrote about their lives in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Angle of Repose.

That book was controversial because of how heavily Stegner relied on the diaries of Mary Hallock Foote in its creation.

Now, you have an opportunity to learn about the Footes, Stegner, and the controversy in a play written by Sands Hall.

A staged reading, directed by Sands Hall, will be performed Saturday, September 24 at 7 pm at the El Korah Shrine Auditorium, 1118 W Idaho in Boise. See the flyer below for additional details. For tickets, click here.

Proceeds will benefit the Foote Park Interpretive Center, which can be accessed by driving south across Lucky Peak Dam, then taking the first road to the right.

I’ve seen the play Fair Use. If you love Idaho history, you won’t want to miss this.

That book was controversial because of how heavily Stegner relied on the diaries of Mary Hallock Foote in its creation.

Now, you have an opportunity to learn about the Footes, Stegner, and the controversy in a play written by Sands Hall.

A staged reading, directed by Sands Hall, will be performed Saturday, September 24 at 7 pm at the El Korah Shrine Auditorium, 1118 W Idaho in Boise. See the flyer below for additional details. For tickets, click here.

Proceeds will benefit the Foote Park Interpretive Center, which can be accessed by driving south across Lucky Peak Dam, then taking the first road to the right.

I’ve seen the play Fair Use. If you love Idaho history, you won’t want to miss this.

Published on September 05, 2022 04:00

September 4, 2022

The Governor You Never Hear About (Tap to read)

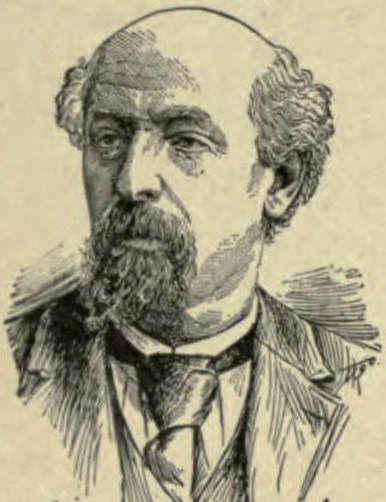

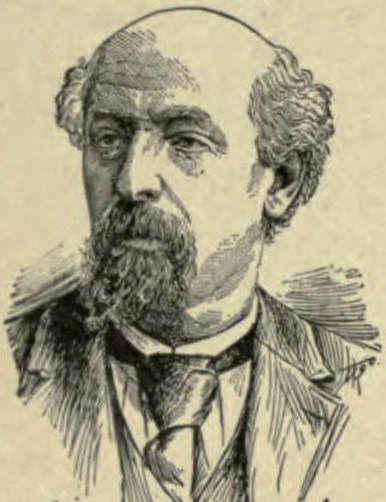

George Shoup is celebrated as Idaho’s first governor. He was also the state’s last territorial governor and one of its first senators. Setting aside some disturbing Shoup history, let’s take a minute to examine his term as the state’s first governor. Well, not examine it, exactly, but measure it. George Shoup was the governor of the State of Idaho for 79 days. As the territorial governor he had agreed to stay on as the state’s governor only with the understanding that he would soon be a US senator, selected in those days by state legislatures. Shoup hand-picked his lieutenant governor knowing full well the man would be filling his gubernatorial shoes when he packed up for Washington, DC.

We don’t hear much about Norman B. Willey, Idaho’s second governor. That’s too bad, because it was really on his watch that most of the details of transition from territory to state took place. It was during his term that state agencies were set up and Idaho got its state seal. He served from December 18, 1890 to January 2, 1893. His political career, which included a term on the Idaho County school board, stints as an Idaho County commissioner and county treasurer, and several terms as a territorial legislator, came to an end when he did not win his party’s nomination for a second term as governor.

Willey had come to Idaho as a miner, and he left the state to become a mine superintendent in California. Things went downhill for him from there. He suffered a string of setbacks. Hearing of his financial situation, the Legislature appropriated $1200 to send to him as something of retirement gift. Then he fell from the public conscious until the headlines read “Former Governor Dies as a Pauper.”

Governor Willey had passed away in a Kansas City poor house after dropping out of sight for a number of years. To add a probably unintentional sting to his ignominious end, the Blackfoot Republican misspelled Norman B. Willey’s name in the announcement of his death. He became “Normal” B. Willey.

We don’t hear much about Norman B. Willey, Idaho’s second governor. That’s too bad, because it was really on his watch that most of the details of transition from territory to state took place. It was during his term that state agencies were set up and Idaho got its state seal. He served from December 18, 1890 to January 2, 1893. His political career, which included a term on the Idaho County school board, stints as an Idaho County commissioner and county treasurer, and several terms as a territorial legislator, came to an end when he did not win his party’s nomination for a second term as governor.

Willey had come to Idaho as a miner, and he left the state to become a mine superintendent in California. Things went downhill for him from there. He suffered a string of setbacks. Hearing of his financial situation, the Legislature appropriated $1200 to send to him as something of retirement gift. Then he fell from the public conscious until the headlines read “Former Governor Dies as a Pauper.”

Governor Willey had passed away in a Kansas City poor house after dropping out of sight for a number of years. To add a probably unintentional sting to his ignominious end, the Blackfoot Republican misspelled Norman B. Willey’s name in the announcement of his death. He became “Normal” B. Willey.

Published on September 04, 2022 04:00

September 3, 2022

A Peck of Foolishness (Tap to read)

Earl Parrot had a good job as a telegrapher until his eyesight changed. He went color blind in 1898. Those operating a telegraph key had to be able to distinguish the colors on railroad signals and he could no longer do so.

Parrot tried a little prospecting in the Klondike for a bit, but by 1900 he was in Idaho. Exactly when he established his nest on the rim of Impassable Canyon overlooking the Middle Fork of the Salmon River is anyone’s guess, but he was there by 1917 and remained there for most of his remaining 28 years.

The best researched sketch of Earl Parrot’s life can be found in Cort Conley’s entertaining book, Idaho Loners . I got the bulk of this post from that book and encourage you to read it to find out more about Parrot as well as other Idaho loners from Sylvan Hart to Claude Dallas.

Conley quoted Francis Wood who was working on a Forest Service survey crew when he bumped into Parrot. Wood said, “One day we spotted a small cabin and noticed smoke coming from the chimney. We decided to stop and have lunch with the occupant. He was busy at a stove cooking some kind of berries. The mixture had not come to a boil. Above the stove, lying on a shelf, was a big cat. When he saw us he made a pass at the cat, knocking it into the fruit. Reaching into the pot, he pulled the cat out and ran his hand over it, draining the berries back into the pot. He then threw the cat out the door. Needless to say, we did not stay for lunch.”

It seemed that everyone who encountered him came away with a good story about the recluse.

Parrot panned a little gold for his annual trips to civilization (often Shoup) to purchase a few supplies. He raised a garden, had a menagerie of animals worthy of a petting zoo, trapped, and hunted. He lived off the land and wasn’t particularly thrilled when visitors dropped by. Your standard hermit stuff.

Conley’s book has some great photos of Parrot, who is said to have thought getting his picture taken was “a peck of foolishness.” The photo included in this post is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo files. It shows Parrot, on the left, with Frank Swain at Parrot’s cabin.

Earl Parrot passed away in 1945 at age 76 in a Salmon nursing home after a couple of strokes and a lengthy illness.

Earl Parrot on the left.

Earl Parrot on the left.

Parrot tried a little prospecting in the Klondike for a bit, but by 1900 he was in Idaho. Exactly when he established his nest on the rim of Impassable Canyon overlooking the Middle Fork of the Salmon River is anyone’s guess, but he was there by 1917 and remained there for most of his remaining 28 years.

The best researched sketch of Earl Parrot’s life can be found in Cort Conley’s entertaining book, Idaho Loners . I got the bulk of this post from that book and encourage you to read it to find out more about Parrot as well as other Idaho loners from Sylvan Hart to Claude Dallas.

Conley quoted Francis Wood who was working on a Forest Service survey crew when he bumped into Parrot. Wood said, “One day we spotted a small cabin and noticed smoke coming from the chimney. We decided to stop and have lunch with the occupant. He was busy at a stove cooking some kind of berries. The mixture had not come to a boil. Above the stove, lying on a shelf, was a big cat. When he saw us he made a pass at the cat, knocking it into the fruit. Reaching into the pot, he pulled the cat out and ran his hand over it, draining the berries back into the pot. He then threw the cat out the door. Needless to say, we did not stay for lunch.”

It seemed that everyone who encountered him came away with a good story about the recluse.

Parrot panned a little gold for his annual trips to civilization (often Shoup) to purchase a few supplies. He raised a garden, had a menagerie of animals worthy of a petting zoo, trapped, and hunted. He lived off the land and wasn’t particularly thrilled when visitors dropped by. Your standard hermit stuff.

Conley’s book has some great photos of Parrot, who is said to have thought getting his picture taken was “a peck of foolishness.” The photo included in this post is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo files. It shows Parrot, on the left, with Frank Swain at Parrot’s cabin.

Earl Parrot passed away in 1945 at age 76 in a Salmon nursing home after a couple of strokes and a lengthy illness.

Earl Parrot on the left.

Earl Parrot on the left.

Published on September 03, 2022 04:00

September 2, 2022

Smoking Craters (Tap to read)

Once, while visiting Hawaii, I had the chance to break off a delicate, lacey piece of lava so new it was still warm. Looking out over that fresh flow it struck me how like it was to some of the features in Craters of the Moon National Monument. There are lava flows there so untouched by seed or seedling that they might have happened yesterday.

Little wonder then that people over the years have sometimes been convinced a new eruption was going on. During the dedication of the monument on June 15, 1924 there was one such startling incident. The day was full of speeches from dignitaries such as energetic Idaho promoter Bob Limbert who almost single-handedly created the monument, C.B. Sampson of Sampson Roads fame, Blackfoot Republican publisher Byrd Trego, and Idaho State Automobile Association President T.E. Bliss. Stirring as the oration probably was, it could not match the belching volcano. While the speakers were still speaking spectators spied smoke boiling up from a nearby crater. Some in the gathering began to move briskly away from the smoke, but Commercial Club President Otto Hoebel calmed the crowd by telling them it was just a stunt designed expressly for the occasion by R.M. Kunze, amateur purveyor of pyrotechnics.

It also was smoke, and allegedly the smell of Sulphur that set gandy dancers on edge during the construction of the Oregon Shortline railroad outside of Shoshone in 1882. Reports were that “Smoke and flame of peculiar odor, color, and shape issued from chasms and seams in the lava beds.” The Idaho Statesman also reported that one observer said, “General commotion over the lava fields and unusual agitation of the boiling springs cause many railroad hands to leave, terror stricken. The whole area has the appearance from a distance of being on fire.”

Was the whole area on fire? That is, were workers spotting one or more range fires, never uncommon on the Idaho desert? There were reports of lava glowing at night and even bubbling. Indians from Fort Hall scoffed at the concern of the railroaders, saying that it happened regularly when the devil had a bellyache. There was also a rumor that rival railroaders were starting fires and spreading chemicals around to scare off the Oregon Shortline men. When the rains came, the smoke went away along with the concerns of the workers.

In 1911, reports—if not fresh lava—circulated again. The Blackfoot Republican, published south and a bit east of the lava fields quoted A.E. Byers of Blackfoot as saying smoke and great quantities of gas “rose to great height and spread like an umbrella.” Meanwhile residents who lived near the smoke thought it was just a brush fire.

No doubt many have looked out across that landscape, seeing smoke, perhaps even emanating from one of the three volcanic buttes in the area, and had a moment of pause. At that moment they might not have been comforted by the fact that park rangers speculate the most recent eruption was about 2,000 years ago.

Not an actual working volcano.

Not an actual working volcano.

Little wonder then that people over the years have sometimes been convinced a new eruption was going on. During the dedication of the monument on June 15, 1924 there was one such startling incident. The day was full of speeches from dignitaries such as energetic Idaho promoter Bob Limbert who almost single-handedly created the monument, C.B. Sampson of Sampson Roads fame, Blackfoot Republican publisher Byrd Trego, and Idaho State Automobile Association President T.E. Bliss. Stirring as the oration probably was, it could not match the belching volcano. While the speakers were still speaking spectators spied smoke boiling up from a nearby crater. Some in the gathering began to move briskly away from the smoke, but Commercial Club President Otto Hoebel calmed the crowd by telling them it was just a stunt designed expressly for the occasion by R.M. Kunze, amateur purveyor of pyrotechnics.

It also was smoke, and allegedly the smell of Sulphur that set gandy dancers on edge during the construction of the Oregon Shortline railroad outside of Shoshone in 1882. Reports were that “Smoke and flame of peculiar odor, color, and shape issued from chasms and seams in the lava beds.” The Idaho Statesman also reported that one observer said, “General commotion over the lava fields and unusual agitation of the boiling springs cause many railroad hands to leave, terror stricken. The whole area has the appearance from a distance of being on fire.”

Was the whole area on fire? That is, were workers spotting one or more range fires, never uncommon on the Idaho desert? There were reports of lava glowing at night and even bubbling. Indians from Fort Hall scoffed at the concern of the railroaders, saying that it happened regularly when the devil had a bellyache. There was also a rumor that rival railroaders were starting fires and spreading chemicals around to scare off the Oregon Shortline men. When the rains came, the smoke went away along with the concerns of the workers.

In 1911, reports—if not fresh lava—circulated again. The Blackfoot Republican, published south and a bit east of the lava fields quoted A.E. Byers of Blackfoot as saying smoke and great quantities of gas “rose to great height and spread like an umbrella.” Meanwhile residents who lived near the smoke thought it was just a brush fire.

No doubt many have looked out across that landscape, seeing smoke, perhaps even emanating from one of the three volcanic buttes in the area, and had a moment of pause. At that moment they might not have been comforted by the fact that park rangers speculate the most recent eruption was about 2,000 years ago.

Not an actual working volcano.

Not an actual working volcano.

Published on September 02, 2022 04:00

September 1, 2022

The Chicken Inn (Tap to read)

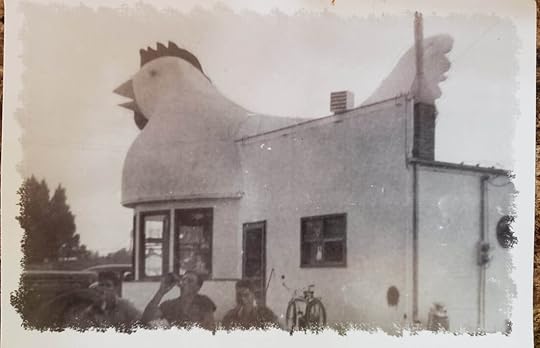

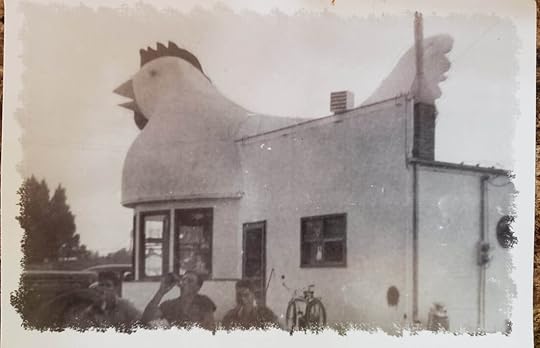

There is a long, perhaps proud, tradition of building restaurants that look like food in the United States. Food-shaped eating establishments include hot dogs, donuts, ice cream cones, a pig, a tamale, an apple, an orange, a pineapple, a banana, a coffee pot, a milk bottle, a soda bottle, and on and on.

Perhaps all the good café designs that resembled food were all taken when some restaurants started popping up with other odd shapes, an owl, a toad, a shoe, a chili bowl, an airplane, teepees, a flower pot, a sphinx, a piano, a blimp, a cream can, and a derby. That last one gives it away that this was a list just from California.

Idaho was not infested with restaurants that looked like food, nor was it immune. There were at least a couple. Many fondly remember the Chicken Inn, a drive in at 323 11th Avenue North. Offering Nampa’s first curb-side service, the Chicken Inn boasted “clear-finish woodwork and modernistic furnishings” inside with a stucco exterior. That exterior is what people remember. The roof was a chicken hunkered down as if sitting on a nest.

The giant chicken probably distinguished Nampa’s Chicken Inn from the other establishments named the Chicken Inn across the state. There was one in McCall, Jerome, Rupert, and Idaho Falls. Boise had a couple of them, at different times.

The advantage of having a restaurant shaped like a chicken was that you didn’t really have to go into detail about what was on the menu. If you wanted tofu, you went somewhere else.

Coeur d’Alene’s Fish Inn used the same strategy. When you walked into the mouth of that sucker (or trout, or whatever), you knew what you were there for. Built in 1932 it operated until the Fish, clearly out of water, burned in 1996.

Nampa’s Chicken Inn opened in February 1940. Joe and Mary Tycz built the place. Joe was born in Moravia in 1905 and moved to the US with his family when he was seven. He married Mary Salek in 1928. Living in South Dakota at the time, they planned to move to Corvallis, Oregon in 1933, but they stopped in Nampa to visit friends, and never left.

The Chicken Inn operated through the 40s and into the 50s though the date of its demise is uncertain. Joe Tycz, who was a member of the Czech community, was also a farmer who raised peaches and spuds. He is remembered for the Chicken Inn, but also for providing the first permanent community Christmas tree to the City of Nampa. Citizens had been cutting trees and decorating them for the season for years. In 1954, Tycz donated a 20-foot-tall living blue spruce for the annual celebrations. It was planted in City Hall Park and became a focal point of community Christmas celebrations for several years.

The Chicken Inn offered Nampa’s first curbside service. It nested on the roof—was the roof—at 323 11th Avenue North in the 40s and 50s. Photo courtesy of Pauline Nielsen.

The Chicken Inn offered Nampa’s first curbside service. It nested on the roof—was the roof—at 323 11th Avenue North in the 40s and 50s. Photo courtesy of Pauline Nielsen.

Perhaps all the good café designs that resembled food were all taken when some restaurants started popping up with other odd shapes, an owl, a toad, a shoe, a chili bowl, an airplane, teepees, a flower pot, a sphinx, a piano, a blimp, a cream can, and a derby. That last one gives it away that this was a list just from California.

Idaho was not infested with restaurants that looked like food, nor was it immune. There were at least a couple. Many fondly remember the Chicken Inn, a drive in at 323 11th Avenue North. Offering Nampa’s first curb-side service, the Chicken Inn boasted “clear-finish woodwork and modernistic furnishings” inside with a stucco exterior. That exterior is what people remember. The roof was a chicken hunkered down as if sitting on a nest.

The giant chicken probably distinguished Nampa’s Chicken Inn from the other establishments named the Chicken Inn across the state. There was one in McCall, Jerome, Rupert, and Idaho Falls. Boise had a couple of them, at different times.

The advantage of having a restaurant shaped like a chicken was that you didn’t really have to go into detail about what was on the menu. If you wanted tofu, you went somewhere else.

Coeur d’Alene’s Fish Inn used the same strategy. When you walked into the mouth of that sucker (or trout, or whatever), you knew what you were there for. Built in 1932 it operated until the Fish, clearly out of water, burned in 1996.

Nampa’s Chicken Inn opened in February 1940. Joe and Mary Tycz built the place. Joe was born in Moravia in 1905 and moved to the US with his family when he was seven. He married Mary Salek in 1928. Living in South Dakota at the time, they planned to move to Corvallis, Oregon in 1933, but they stopped in Nampa to visit friends, and never left.

The Chicken Inn operated through the 40s and into the 50s though the date of its demise is uncertain. Joe Tycz, who was a member of the Czech community, was also a farmer who raised peaches and spuds. He is remembered for the Chicken Inn, but also for providing the first permanent community Christmas tree to the City of Nampa. Citizens had been cutting trees and decorating them for the season for years. In 1954, Tycz donated a 20-foot-tall living blue spruce for the annual celebrations. It was planted in City Hall Park and became a focal point of community Christmas celebrations for several years.

The Chicken Inn offered Nampa’s first curbside service. It nested on the roof—was the roof—at 323 11th Avenue North in the 40s and 50s. Photo courtesy of Pauline Nielsen.

The Chicken Inn offered Nampa’s first curbside service. It nested on the roof—was the roof—at 323 11th Avenue North in the 40s and 50s. Photo courtesy of Pauline Nielsen.

Published on September 01, 2022 04:00

August 31, 2022

Pop Quiz, August 2012

Published on August 31, 2022 04:00

August 30, 2022

Carol Ryrie Brink (Tap to read)

Some writers are born from adversity. One of Idaho’s celebrated authors knew three notes of tragedy early in her life.

Carol Ryrie Brink’s birth was attended by her grandfather, Dr. William Woodbury Watkins. When the baby girl emerged, she did so silently. Her grandmother, Carol Woodhouse Watkins, who was also there, whispered, “Stillborn.” Dr. Watkins had none of that. He picked up the infant and began breathing into its mouth. After a few moments the baby began to squirm and cry. As Brink said in her autobiography, A Chain of Hands, “He gave me my life more surely than my parents did.”

Her first tragedy was when her father, Alex Ryrie, died from tuberculosis when she was five. When Brink was six years old, she would know her second heartbreak. On August 4, 1901, her grandfather turned 55. It would be his last birthday.

On that Sunday, Dr. Watkins was driving a phaeton on his way to his office in Moscow where he was to attend to a sick young girl. As he approached an intersection a man on horseback rode up in front of Watkin’s carriage. Recognizing the man as William Steffans a local farmer and fellow Mason, he stopped and greeted him. Watkins knew Steffans as a violent man, one whom he had previously confronted after Steffans had beaten his own mother.

Steffans was not headed to church that day. He had a to-do list with him of the worst possible kind. The name of Dr. Watkins was on it. Steffans promptly pulled his pistol and shot the doctor. Watkins’ horse startled and ran, stopping only when it arrived at the familiar office of the man now sprawled dead on the seat of his carriage.

Meanwhile, Steffans rode through the streets of Moscow looking for people on his list that he had grudges with. He wasn’t having any luck finding them, so he began shooting randomly at anyone he saw, wounding several. The police were soon in pursuit. Foretelling the plot device of countless future movies, they shot not the tire of a criminal’s car, but the leg of his horse.

Afoot now, Steffans ran across the fields to his house and holed up inside. The townspeople formed a posse, gathered guns, and began a siege of the house. Steffans returned fire and the battle went on for some two hours. The mother he had treated so badly called out from inside the house that her son was dead. Whether from his own hand or a posse bullet is unclear.

In addition to Dr. Watkins a deputy died from wounds inflicted by Steffans.

Dr. Watkins was an engaged man, active not only in Moscow, but statewide. He was the first president of the state’s medical association, a member of the Board of Regents at the University of Idaho, and the chair of the first Idaho State Republican convention, during which he turned down a nomination for governor.

Brink honored her grandfather when she wrote a novel called Buffalo Coat in 1944. Based on his life, the book was on the New York Times bestseller list for weeks.

The final early tragedy in Brink’s life was the suicide of her mother when Carol was nine following a disastrous marriage. After that the young girl went to live with her widowed grandmother, Carol Woodhouse Watkins. It was her grandmother’s story, fictionalized in the book Caddie Woodlawn that won Brink the 1936 Newbery Medal for “distinguished contribution to American Literature for children.”

In all, Carol Ryrie Brink would write more than 30 books, including her acclaimed adult trilogy Buffalo Coat, Strangers in the Forest, and Snow on the River, the last of which won the National League of American Pen Women Fiction Award.

Carol Ryrie Brink passed away at age 85 in 1981.

Carol Ryrie Brink’s birth was attended by her grandfather, Dr. William Woodbury Watkins. When the baby girl emerged, she did so silently. Her grandmother, Carol Woodhouse Watkins, who was also there, whispered, “Stillborn.” Dr. Watkins had none of that. He picked up the infant and began breathing into its mouth. After a few moments the baby began to squirm and cry. As Brink said in her autobiography, A Chain of Hands, “He gave me my life more surely than my parents did.”

Her first tragedy was when her father, Alex Ryrie, died from tuberculosis when she was five. When Brink was six years old, she would know her second heartbreak. On August 4, 1901, her grandfather turned 55. It would be his last birthday.

On that Sunday, Dr. Watkins was driving a phaeton on his way to his office in Moscow where he was to attend to a sick young girl. As he approached an intersection a man on horseback rode up in front of Watkin’s carriage. Recognizing the man as William Steffans a local farmer and fellow Mason, he stopped and greeted him. Watkins knew Steffans as a violent man, one whom he had previously confronted after Steffans had beaten his own mother.

Steffans was not headed to church that day. He had a to-do list with him of the worst possible kind. The name of Dr. Watkins was on it. Steffans promptly pulled his pistol and shot the doctor. Watkins’ horse startled and ran, stopping only when it arrived at the familiar office of the man now sprawled dead on the seat of his carriage.

Meanwhile, Steffans rode through the streets of Moscow looking for people on his list that he had grudges with. He wasn’t having any luck finding them, so he began shooting randomly at anyone he saw, wounding several. The police were soon in pursuit. Foretelling the plot device of countless future movies, they shot not the tire of a criminal’s car, but the leg of his horse.

Afoot now, Steffans ran across the fields to his house and holed up inside. The townspeople formed a posse, gathered guns, and began a siege of the house. Steffans returned fire and the battle went on for some two hours. The mother he had treated so badly called out from inside the house that her son was dead. Whether from his own hand or a posse bullet is unclear.

In addition to Dr. Watkins a deputy died from wounds inflicted by Steffans.

Dr. Watkins was an engaged man, active not only in Moscow, but statewide. He was the first president of the state’s medical association, a member of the Board of Regents at the University of Idaho, and the chair of the first Idaho State Republican convention, during which he turned down a nomination for governor.

Brink honored her grandfather when she wrote a novel called Buffalo Coat in 1944. Based on his life, the book was on the New York Times bestseller list for weeks.

The final early tragedy in Brink’s life was the suicide of her mother when Carol was nine following a disastrous marriage. After that the young girl went to live with her widowed grandmother, Carol Woodhouse Watkins. It was her grandmother’s story, fictionalized in the book Caddie Woodlawn that won Brink the 1936 Newbery Medal for “distinguished contribution to American Literature for children.”

In all, Carol Ryrie Brink would write more than 30 books, including her acclaimed adult trilogy Buffalo Coat, Strangers in the Forest, and Snow on the River, the last of which won the National League of American Pen Women Fiction Award.

Carol Ryrie Brink passed away at age 85 in 1981.

Published on August 30, 2022 04:00

August 29, 2022

Boise's Airship Crash (Tap to read)

Oh, the humanity! Fortunately, Boise’s airship crash involved neither fire nor death.

The year was 1908, and it was Fair time. Fairgoers were excited because officials had booked an amazing exhibition. The Strobel Airship, which had just won first prize in the International Races in St. Louis, was coming to Boise.

Charles J. Strobel of Toledo, Ohio had built the contraption. The dirigible looked a bit like a flying sausage. The silken bag was filled with hydrogen and had a rudder and 15 horsepower motor spinning a propeller installed on the framework that hung suspended beneath.

The Strobel Airship was to be piloted by Captain Evan Jenkins Parker. He made some bold promises to Boise Mayor John M. Haines. The Idaho Statesman quoted him as saying he would sail his big aerial craft from the fairgrounds to the business district and guide its course around the peaks on the city hall building and play with his toy over the tops of business buildings.

On October 20, Parker made a couple of successful runs at the fair much to the delight of the crowds. Then, on October 24, he set out to keep his boast to the mayor.

Parker took off and was making rapid progress toward his circumnavigation of city hall when a gust of wind twisted the gas bag in such a manner that the propeller caught one of the airship’s suspension ropes. The whirling prop pulled the rope down tight against the bag, tearing a 12-foot hole in the air sack.

The hydrogen began escaping and the ship started to drop. Parker scrambled to the front end of the frame to tip the airship at an angle that would keep some of the gas from leaking out. In that unconventional manner he brought the dirigible down on River Street without further damage to the ship or to himself.

It was Parker’s first crash with the Strobel Airship. It wouldn’t be his last. A gust of wind pushed the machine into a roller coaster in Manchester, New Hampshire in 1910. In 1911 he hit electrical wires at a fair in Lynn, Massachusetts. Shortly thereafter he retired from flying gas bags, going to work for Eastman Kodak where he had a 38-year career.

Thanks to the Early Birds of Aviation, Inc. website for much of this story.

Captain Parker flying the Strobel Airship at an exhibition, site unknown.

Captain Parker flying the Strobel Airship at an exhibition, site unknown.

The year was 1908, and it was Fair time. Fairgoers were excited because officials had booked an amazing exhibition. The Strobel Airship, which had just won first prize in the International Races in St. Louis, was coming to Boise.

Charles J. Strobel of Toledo, Ohio had built the contraption. The dirigible looked a bit like a flying sausage. The silken bag was filled with hydrogen and had a rudder and 15 horsepower motor spinning a propeller installed on the framework that hung suspended beneath.

The Strobel Airship was to be piloted by Captain Evan Jenkins Parker. He made some bold promises to Boise Mayor John M. Haines. The Idaho Statesman quoted him as saying he would sail his big aerial craft from the fairgrounds to the business district and guide its course around the peaks on the city hall building and play with his toy over the tops of business buildings.

On October 20, Parker made a couple of successful runs at the fair much to the delight of the crowds. Then, on October 24, he set out to keep his boast to the mayor.

Parker took off and was making rapid progress toward his circumnavigation of city hall when a gust of wind twisted the gas bag in such a manner that the propeller caught one of the airship’s suspension ropes. The whirling prop pulled the rope down tight against the bag, tearing a 12-foot hole in the air sack.

The hydrogen began escaping and the ship started to drop. Parker scrambled to the front end of the frame to tip the airship at an angle that would keep some of the gas from leaking out. In that unconventional manner he brought the dirigible down on River Street without further damage to the ship or to himself.

It was Parker’s first crash with the Strobel Airship. It wouldn’t be his last. A gust of wind pushed the machine into a roller coaster in Manchester, New Hampshire in 1910. In 1911 he hit electrical wires at a fair in Lynn, Massachusetts. Shortly thereafter he retired from flying gas bags, going to work for Eastman Kodak where he had a 38-year career.

Thanks to the Early Birds of Aviation, Inc. website for much of this story.

Captain Parker flying the Strobel Airship at an exhibition, site unknown.

Captain Parker flying the Strobel Airship at an exhibition, site unknown.

Published on August 29, 2022 04:00