Rick Just's Blog, page 80

October 18, 2022

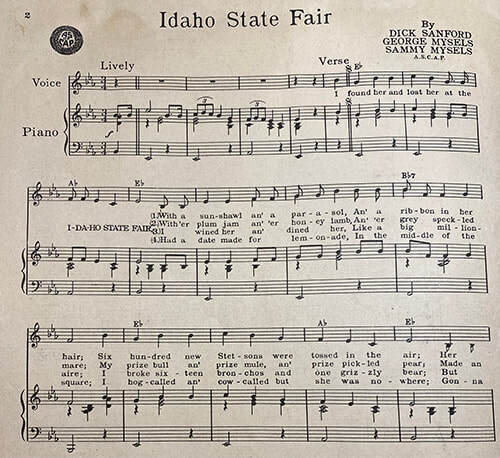

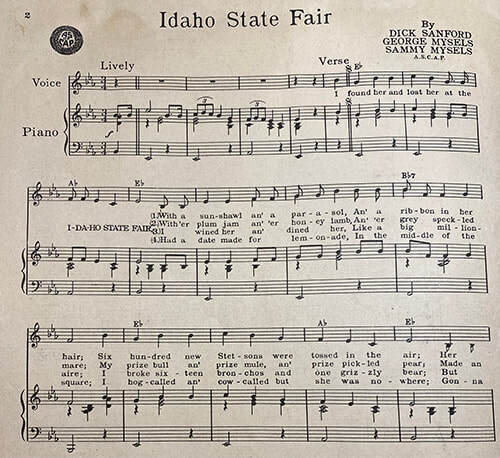

"Idaho State Fair" (Tap to read)

I grew up in Eastern Idaho where the Idaho State Fair is a big deal. In my formative years I heard the song “Idaho State Fair” enough for it to become an ear worm. It occurs to me that faithful readers of this blog might not all have had the chance to enjoy it. So, here’s a link to the song.

You probably didn’t hear this on top 40 stations in 1952—excluding KBLI of course—when it was recorded by Vaughn Monroe. That’s because it was the B side of the 45. The A side was “Lady Love,” which you likely didn’t hear either. As a public service I provide you with a link so you can determine for yourself why this might not have been a big hit. You’re welcome.

You probably didn’t hear this on top 40 stations in 1952—excluding KBLI of course—when it was recorded by Vaughn Monroe. That’s because it was the B side of the 45. The A side was “Lady Love,” which you likely didn’t hear either. As a public service I provide you with a link so you can determine for yourself why this might not have been a big hit. You’re welcome.

Published on October 18, 2022 04:00

October 17, 2022

Beehive Burners (Tap to read)

I have a special memory about beehive burners, sometimes called teepee or wigwam burners. Shaped something like each item they are named after, they were a common sight in 1960. My memory proves it.

My parents brought me along that summer on a trip that took us from our ranch on the Blackfoot River all the way to Edmonton, Alberta, Canada and back. We had a near-new 1959 Ford pickup and a new slide-in camper with a sleeping compartment hanging over the cab. They were the latest invention. We saw exactly two of them on our two-week trip.

And that has what to do with beehive burners? I spotted one on our way north out of Idaho Falls. Pop told me that they were used to burn off wood waste from lumber mills. Not many miles down the road, we saw another, then another. My mother had bought 10-year-old me a book, or series of books, called I Spy to keep me entertained on the long road trip. I was already geared up to check off various objects I spied from chickens to radio antennas, so it made sense for me to start counting beehive burners.

I spent much of the road trip sprawled across the bed above the cab staring out of the tiny forward-facing windows, flouting future road rules. If I didn’t see a beehive burner first, my parents would pound on the roof to let me know there was one nearby. By the time we got back home I had tallied 50 of them.

Take that same trip today and you might see a few, mostly relics of bygone days not yet turned into scrap.

Beehive burners were typically fed by a conveyor belt that moved sawdust, woodchips, and snaggled branches into a hole near their top. The wood detritus fell onto the pile of burning debris below. On top of the burners was a smoke vent covered in steel mesh to help keep sparks from flying too far.

Air quality concerns have shut the things down in many places. They belch a lot of smoke. Lumber operations produce much less waste today, too, using what was once burned for particle board and mulch.

This is a picture of a beehive or wigwam burner operating at the Louisiana-Pacific lumber plant near Post Falls in 1973. The photo is from the U.S. National Archives, David Falconer photographer.

This is a picture of a beehive or wigwam burner operating at the Louisiana-Pacific lumber plant near Post Falls in 1973. The photo is from the U.S. National Archives, David Falconer photographer.

My parents brought me along that summer on a trip that took us from our ranch on the Blackfoot River all the way to Edmonton, Alberta, Canada and back. We had a near-new 1959 Ford pickup and a new slide-in camper with a sleeping compartment hanging over the cab. They were the latest invention. We saw exactly two of them on our two-week trip.

And that has what to do with beehive burners? I spotted one on our way north out of Idaho Falls. Pop told me that they were used to burn off wood waste from lumber mills. Not many miles down the road, we saw another, then another. My mother had bought 10-year-old me a book, or series of books, called I Spy to keep me entertained on the long road trip. I was already geared up to check off various objects I spied from chickens to radio antennas, so it made sense for me to start counting beehive burners.

I spent much of the road trip sprawled across the bed above the cab staring out of the tiny forward-facing windows, flouting future road rules. If I didn’t see a beehive burner first, my parents would pound on the roof to let me know there was one nearby. By the time we got back home I had tallied 50 of them.

Take that same trip today and you might see a few, mostly relics of bygone days not yet turned into scrap.

Beehive burners were typically fed by a conveyor belt that moved sawdust, woodchips, and snaggled branches into a hole near their top. The wood detritus fell onto the pile of burning debris below. On top of the burners was a smoke vent covered in steel mesh to help keep sparks from flying too far.

Air quality concerns have shut the things down in many places. They belch a lot of smoke. Lumber operations produce much less waste today, too, using what was once burned for particle board and mulch.

This is a picture of a beehive or wigwam burner operating at the Louisiana-Pacific lumber plant near Post Falls in 1973. The photo is from the U.S. National Archives, David Falconer photographer.

This is a picture of a beehive or wigwam burner operating at the Louisiana-Pacific lumber plant near Post Falls in 1973. The photo is from the U.S. National Archives, David Falconer photographer.

Published on October 17, 2022 04:00

October 16, 2022

The Misses Mudge (Tap to read)

Sometimes you can go just so far in historical research. That can be frustrating if there is clearly a story there to uncover. Or, as in the case of the Misses Mudge, it can be a couple of hours spent getting the bones of a story from a single clue. That’s satisfying in itself, even if it doesn’t add much to the historical record.

I found a photograph among my great grandparent’s collections that sent me on a little journey. Nels and Emma Just were Idaho pioneers who came to the state (separately) in 1863. They met in 1870 during the construction of the military Fort Hall on Lincoln Creek. She was baking bread for the soldiers and living with her aunt and uncle nearby. He was a freighter who counted the fort an occasional customer.

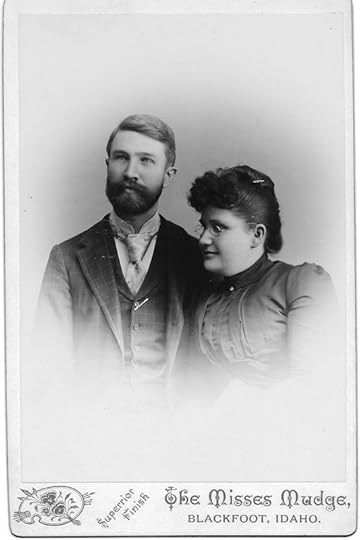

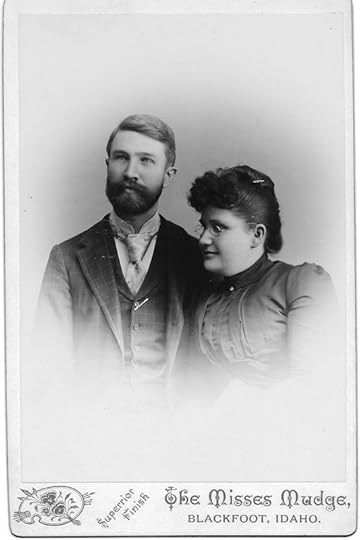

The photo, below, is of Fort Hall’s Dr. Gregory and his wife. I’ll research them for another post. This is not about the photo itself, but about the photographers, The Misses Mudge. I was able to develop an interesting post from a similar clue found on another photo in that collection, leading me to learn more about the Union Pacific Photo Car. I wasn’t as successful with this search, but I’ll tell you what I learned.

The photograph of the doctor and his wife is a good example of a cabinet card. Cabinet cards were introduced in the 1860s, and were especially popular in the 1870s, 80s, and 90s. They disappeared from popular use in the 1930s.

Cabinet cards, thin photos mounted on card stock that formed its own frame, were designed to be placed on a cabinet, shelf, or dresser to display a favorite photo. They were larger than the photographic type they replaced, small carte de viste photos most often displayed in an album. Cabinet card brought photos out for everyone to view.

It was common for photographers to put their imprint on the front and something about their business on the back. What drew me to the creator or creators of this cabinet card was the name, “The Misses Mudge.” I’m a sucker for alliteration and I’m always on the lookout for jobs women were doing in earlier days that one might not have expected.

Women photographers were not especially rare, but the Mudges were probably the first to set up shop in Blackfoot. Years later (the 1950s and 1960s) Grace Sandberg would be THE photographer in Blackfoot.

What drew the Mudges to Idaho? I wasn’t able to learn that, but we know it wasn’t accidental. The sisters Kathrine Raymond Mudge and Caroline Alide Mudge, sent samples of their work ahead of their arrival to be put on display in the Blackfoot Post Office. That was in May 1892.

“The Misses Mudge, of Randalis, Iowa, will be here in about two weeks to open a photograph gallery. They come highly recommended, but their work will be on exhibition at the post office within a few days and will speak for itself. Notice it and judge of it.”

The sisters went by Kate and Carry. It took some sleuthing to learn that. Carry was mentioned by name exactly once in the Blackfoot paper, Kate a handful of times. Whenever the mention involved photography, and often when it didn’t, they were called The Misses Mudge.

In August 1892, they had set up their gallery “south of Hopkins lumber.” It was open four days a week, Wednesday through Saturday, saving Mondays and Tuesdays for “finishing work.” Portraits were their bread and butter, but the Mudge sisters made the papers when they travelled to Fort Hall to take pictures of various things, and when they shot group photos.

The Misses Mudge closed their gallery in December, probably to winter in California. They were back in Blackfoot the following spring taking photos and taking part in community activities. They often sang as a duet for various functions, particularly those sponsored by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

In July 1893 The Misses Mudge were advertising their cabinet photos for $3 a dozen. That seems like a bargain, at least until you consider what wages were at that time. A farmworker was making about $13 a month.

The sisters took a train to California in October 1893. They came back the following spring, but little mention was made of them after that. In 1904, Kate came back for a visit.

The Misses Mudge, and a third sister, Rosela Emma “Rose” Mudge, ended up in Redlands, California. All three had been teachers at some time in their lives. None of them ever married. The three sisters are buried in Redlands.

We will probably never know what brought them to Blackfoot that summer of 1892. They left their mark in family photo albums of the time, many of which are still around. One thing they did not leave behind, at least for me to find, was a picture of The Misses Mudge.

I found a photograph among my great grandparent’s collections that sent me on a little journey. Nels and Emma Just were Idaho pioneers who came to the state (separately) in 1863. They met in 1870 during the construction of the military Fort Hall on Lincoln Creek. She was baking bread for the soldiers and living with her aunt and uncle nearby. He was a freighter who counted the fort an occasional customer.

The photo, below, is of Fort Hall’s Dr. Gregory and his wife. I’ll research them for another post. This is not about the photo itself, but about the photographers, The Misses Mudge. I was able to develop an interesting post from a similar clue found on another photo in that collection, leading me to learn more about the Union Pacific Photo Car. I wasn’t as successful with this search, but I’ll tell you what I learned.

The photograph of the doctor and his wife is a good example of a cabinet card. Cabinet cards were introduced in the 1860s, and were especially popular in the 1870s, 80s, and 90s. They disappeared from popular use in the 1930s.

Cabinet cards, thin photos mounted on card stock that formed its own frame, were designed to be placed on a cabinet, shelf, or dresser to display a favorite photo. They were larger than the photographic type they replaced, small carte de viste photos most often displayed in an album. Cabinet card brought photos out for everyone to view.

It was common for photographers to put their imprint on the front and something about their business on the back. What drew me to the creator or creators of this cabinet card was the name, “The Misses Mudge.” I’m a sucker for alliteration and I’m always on the lookout for jobs women were doing in earlier days that one might not have expected.

Women photographers were not especially rare, but the Mudges were probably the first to set up shop in Blackfoot. Years later (the 1950s and 1960s) Grace Sandberg would be THE photographer in Blackfoot.

What drew the Mudges to Idaho? I wasn’t able to learn that, but we know it wasn’t accidental. The sisters Kathrine Raymond Mudge and Caroline Alide Mudge, sent samples of their work ahead of their arrival to be put on display in the Blackfoot Post Office. That was in May 1892.

“The Misses Mudge, of Randalis, Iowa, will be here in about two weeks to open a photograph gallery. They come highly recommended, but their work will be on exhibition at the post office within a few days and will speak for itself. Notice it and judge of it.”

The sisters went by Kate and Carry. It took some sleuthing to learn that. Carry was mentioned by name exactly once in the Blackfoot paper, Kate a handful of times. Whenever the mention involved photography, and often when it didn’t, they were called The Misses Mudge.

In August 1892, they had set up their gallery “south of Hopkins lumber.” It was open four days a week, Wednesday through Saturday, saving Mondays and Tuesdays for “finishing work.” Portraits were their bread and butter, but the Mudge sisters made the papers when they travelled to Fort Hall to take pictures of various things, and when they shot group photos.

The Misses Mudge closed their gallery in December, probably to winter in California. They were back in Blackfoot the following spring taking photos and taking part in community activities. They often sang as a duet for various functions, particularly those sponsored by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

In July 1893 The Misses Mudge were advertising their cabinet photos for $3 a dozen. That seems like a bargain, at least until you consider what wages were at that time. A farmworker was making about $13 a month.

The sisters took a train to California in October 1893. They came back the following spring, but little mention was made of them after that. In 1904, Kate came back for a visit.

The Misses Mudge, and a third sister, Rosela Emma “Rose” Mudge, ended up in Redlands, California. All three had been teachers at some time in their lives. None of them ever married. The three sisters are buried in Redlands.

We will probably never know what brought them to Blackfoot that summer of 1892. They left their mark in family photo albums of the time, many of which are still around. One thing they did not leave behind, at least for me to find, was a picture of The Misses Mudge.

Published on October 16, 2022 04:00

October 15, 2022

The Tallest Dam (Tap to read)

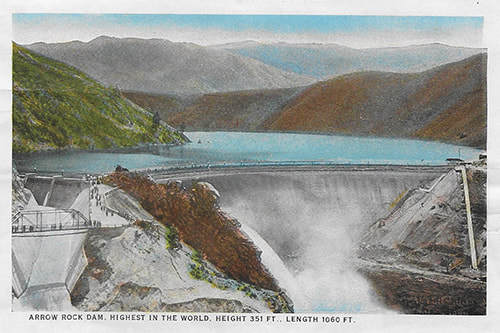

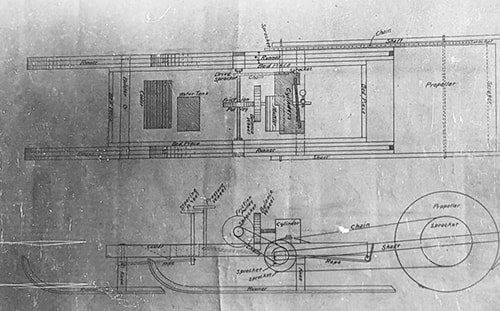

Arrowrock Dam may not seem like an engineering marvel, but it was the tallest dam in the world at one time. It didn’t hold that distinction for long. At 348, 350, or 351 feet—different writers used different rulers, apparently—it held that title from 1915 until 1932 when the Owyhee Dam in Oregon knocked it off its pedestal by about 50 feet.

The postcard below trumpeted the dam’s status by calling it the “highest dam.” I don’t know what dam would be the highest in the world, since “highest” refers to elevation. In Idaho the dam at the highest elevation would probably be Palisades Dam. Anyway, they meant tallest.

Arrowrock doesn’t even make the Wikipedia list of tall dams today. The tallest on that list is the Jinping Dam in China, at 1,001 feet.

The postcard below trumpeted the dam’s status by calling it the “highest dam.” I don’t know what dam would be the highest in the world, since “highest” refers to elevation. In Idaho the dam at the highest elevation would probably be Palisades Dam. Anyway, they meant tallest.

Arrowrock doesn’t even make the Wikipedia list of tall dams today. The tallest on that list is the Jinping Dam in China, at 1,001 feet.

Published on October 15, 2022 04:00

October 14, 2022

The Table Rock Hotel (Tap to read)

You know Table Rock above the Old Idaho Penitentiary in Boise as the flat-topped mountain where the lighted cross stands overlooking the valley. You might also know it as a place where numerous rowdy parties have been held over the years. Do you remember that it is the home of Boise’s rock quarry? Do you recall that the big Boise “B” is located on the west end of the mesa?

Table Rock is all those things. If a plan put forth in 1907 had come to fruition, it would be something quite different.

In November of 1907, the Idaho Statesman ran the headline, “Hotel To Be Built On Table Rock.” J.S. Jellison had purchased his brother’s interest in the quarry on Table Rock, including 685 acres of property.

The hotel Jellison envisioned would be “a delightful summer resort.” Part of the ambitious plan was to run a set of trolley tracks up to the top of the mesa and in a loop around the rim of Table Rock. There was to be a branch line to the quarry to facilitate bringing rock into the valley.

And readers never heard another peep about it again. A trolley loop around the rim of Table Rock would be one more reason today to lament the loss of the Interurban. Perhaps.

Table Rock is all those things. If a plan put forth in 1907 had come to fruition, it would be something quite different.

In November of 1907, the Idaho Statesman ran the headline, “Hotel To Be Built On Table Rock.” J.S. Jellison had purchased his brother’s interest in the quarry on Table Rock, including 685 acres of property.

The hotel Jellison envisioned would be “a delightful summer resort.” Part of the ambitious plan was to run a set of trolley tracks up to the top of the mesa and in a loop around the rim of Table Rock. There was to be a branch line to the quarry to facilitate bringing rock into the valley.

And readers never heard another peep about it again. A trolley loop around the rim of Table Rock would be one more reason today to lament the loss of the Interurban. Perhaps.

Published on October 14, 2022 04:00

October 13, 2022

Blackfoot Streetview (Tap to read)

The colorized photo of Main Street, Blackfoot on top below is probably from 1909 when the city was celebrating the Diamond Jubilee of the first Protestant service west of the Rocky Mountains being conducted in a grove near Fort Hall, and the first raising of the United States flag in the Pacific Northwest. I wrote about that in an earlier blog.

I noticed that the postcard photo doesn’t look a lot different from Main Street in Blackfoot today, so I grabbed a Google Streetview capture for comparison. It’s below the postcard.

If you follow with your finger straight down from where Main Street is printed on the postcard, you can just make out where Bridge Street intersects with it. Both buildings on either side of Bridge are still there today though the one on the far left has been much modified. Both have 45-degree corner entrances, though that’s difficult to make out in the contemporary photo.

Working back toward the right you can still make out the next two buildings, which are little changed. Then we see that the next three buildings in the 1909 photo have a metal facade tying them all together in the contemporary photo. Past the 1910 Groceries building we see a single gray building with a distinctive cornice running along the top. In the contemporary photo we see that part of the façade of that building has been modified to make it look like two distinct buildings.

The first photo was probably taken from near the train station, which is today the Idaho Potato Museum.

I noticed that the postcard photo doesn’t look a lot different from Main Street in Blackfoot today, so I grabbed a Google Streetview capture for comparison. It’s below the postcard.

If you follow with your finger straight down from where Main Street is printed on the postcard, you can just make out where Bridge Street intersects with it. Both buildings on either side of Bridge are still there today though the one on the far left has been much modified. Both have 45-degree corner entrances, though that’s difficult to make out in the contemporary photo.

Working back toward the right you can still make out the next two buildings, which are little changed. Then we see that the next three buildings in the 1909 photo have a metal facade tying them all together in the contemporary photo. Past the 1910 Groceries building we see a single gray building with a distinctive cornice running along the top. In the contemporary photo we see that part of the façade of that building has been modified to make it look like two distinct buildings.

The first photo was probably taken from near the train station, which is today the Idaho Potato Museum.

Published on October 13, 2022 04:00

October 12, 2022

Joseph Sherwood, Part 2 (tap to read)

Yesterday I wrote a post about entrepreneur and Island Park pioneer Joseph Sherwood.

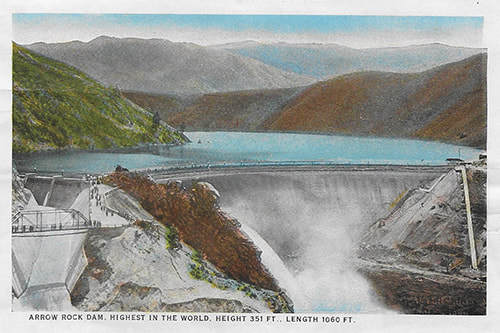

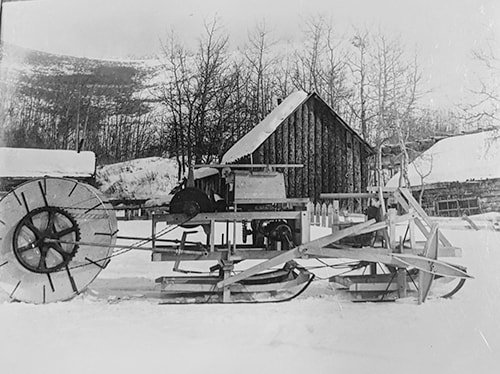

Sherwood built his own sawmill on the north shore of Henrys Lake using a canvas flume carrying water from ponds he had constructed for power. He was a mechanically minded man.

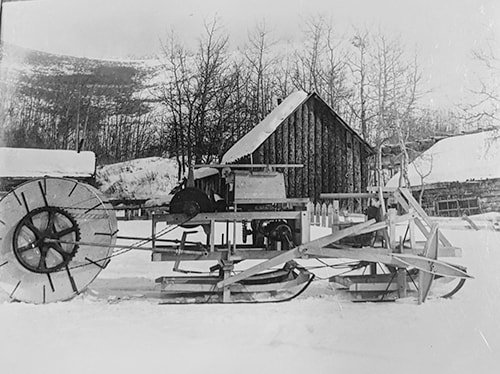

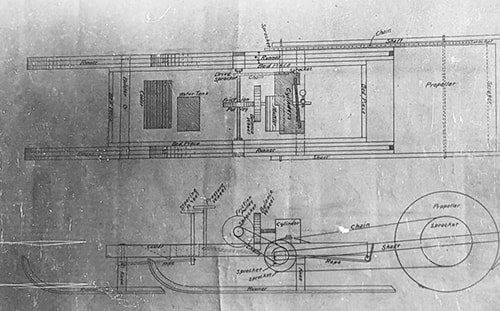

Did Sherwood have the first snowmobile in Idaho? I don’t know, but I’d like to hear if anyone knows of an earlier one. He received a patent, number 844,963 for his “auto snow-car.” He patterned it after a four runner, horse-drawn sled. A 1 ½ horsepower gasoline engine was connected gearbox and flywheel by a chain drive. Another set of chains wrapped around sprockets on a large wooden drum in the rear. That was the equivalent to the track on a modern snowmobile. To steer the contraption you moved the front runners from side to side by means of a lever.

The snow machine weighed something under 1,000 pounds. It wouldn’t win any races with a top speed of 12 miles per hour.

Sherwood didn’t apply for a patent on his car. He just built it. It was called “The Black Car.” He used magazine pictures as his construction guide.

The Sherwood store had been a stage stop for years. As motor vehicles began to appear in the Island Park area—his own was probably the first—Sherwood began selling gasoline and motor oil.

Joseph Sherwood died in 1919 due to complications from diabetes. The store he built continued in operation until the mid-1960s. The building has undergone extensive renovation and restoration. According to an article in the Rexburg Standard Journal, it may soon see another chapter in its history.

Joseph Sherwood’s snow machine.

Joseph Sherwood’s snow machine.  The schematic for Sherwood’s patented vehicle.

The schematic for Sherwood’s patented vehicle.  “The Black Car,” built by Joseph Sherwood.

“The Black Car,” built by Joseph Sherwood.

Sherwood built his own sawmill on the north shore of Henrys Lake using a canvas flume carrying water from ponds he had constructed for power. He was a mechanically minded man.

Did Sherwood have the first snowmobile in Idaho? I don’t know, but I’d like to hear if anyone knows of an earlier one. He received a patent, number 844,963 for his “auto snow-car.” He patterned it after a four runner, horse-drawn sled. A 1 ½ horsepower gasoline engine was connected gearbox and flywheel by a chain drive. Another set of chains wrapped around sprockets on a large wooden drum in the rear. That was the equivalent to the track on a modern snowmobile. To steer the contraption you moved the front runners from side to side by means of a lever.

The snow machine weighed something under 1,000 pounds. It wouldn’t win any races with a top speed of 12 miles per hour.

Sherwood didn’t apply for a patent on his car. He just built it. It was called “The Black Car.” He used magazine pictures as his construction guide.

The Sherwood store had been a stage stop for years. As motor vehicles began to appear in the Island Park area—his own was probably the first—Sherwood began selling gasoline and motor oil.

Joseph Sherwood died in 1919 due to complications from diabetes. The store he built continued in operation until the mid-1960s. The building has undergone extensive renovation and restoration. According to an article in the Rexburg Standard Journal, it may soon see another chapter in its history.

Joseph Sherwood’s snow machine.

Joseph Sherwood’s snow machine.  The schematic for Sherwood’s patented vehicle.

The schematic for Sherwood’s patented vehicle.  “The Black Car,” built by Joseph Sherwood.

“The Black Car,” built by Joseph Sherwood.

Published on October 12, 2022 04:00

October 11, 2022

Joseph Sherwood, Part One (Tap to read)

I’m going to write a couple of posts about Joseph Sherwood, an enterprising man who came to what is now known as the Island Park area in about 1889. Today I’ll focus on the entrepreneurial Sherwood. Tomorrow we’ll talk about Sherwood the inventor.

Joseph Sherwood built a store on the north shore of Henrys Lake. We don’t know a lot about the structure, except that it burned and was subsequently replaced in about 1899. As a community focal point, the store became the post office of Lake, Idaho. Sherwood was named the postmaster.

Along with his wife Susan, Sherwood built a going enterprise. They raised cattle and in something of a precursor to Idaho’s famous Magic Valley trout farms, Sherwood packaged fish caught by locals and shipped them off to customers in Montana and California. This was no small operation. Sherwood once wrote in a letter that “The amount of fish usually caught in winter here varies from 50 to 90,000 pounds.”

Sherwood also ran a sawmill that was powered by gravity-fed water running in a canvas flume from a series of ponds he had developed above his place. He sold lumber commercially and used the sawmill to build his store.

And what a building it was—and is. It has since been modified, but the structure built in 1899 was 55 feet wide, 37 feet deep, and 46 feet high. It contained 27 rooms. The general store and post office was on the first floor, along with a family living area. The second floor had four bedrooms for rental to overnight stagecoach guests, a display room for Sherwood’s taxidermy, a photographic darkroom, and a photo gallery. A half-story attic was used for storage.

The store and museum was the home base for Sherwood’s boats. He rented them and often took visitors out on the lake from his launch.

About that taxidermy… Sherwood took a correspondence course to learn how to do it. He shared his knowledge with his second wife, Ann, after Susan’s death. Together they set out to mount at least once specimen of every critter native to Island Park. That room full of taxidermy mounts was why the store was often called the Sherwood Museum.

To say that Joseph Sherwood was self-sufficient would be like saying there were a few fish in Henrys Lake. One story, told in the National Register of Historic Places application for his building, was about his medical skills. He delivered he and Ann’s children himself, including Clarence Sherwood, who told this story. One day his father was thrown from a wagon some distance from their home. Joseph Sherwood fashioned a splint for his leg, got back into his wagon, and drove home. When he got home, with Ann’s help he set his leg. Then he hopped back in the wagon and headed for St. Anthony to attend a board meeting of the local bank, where he served as president.

Tomorrow I’ll conclude the Joseph Sherwood story with a little bit about his inventions.

Joseph Sherwood’s store as it appeared in the application for its listing on the National Register of Historic Places. It was approved for that listing in 1996.

Joseph Sherwood’s store as it appeared in the application for its listing on the National Register of Historic Places. It was approved for that listing in 1996.

Joseph Sherwood built a store on the north shore of Henrys Lake. We don’t know a lot about the structure, except that it burned and was subsequently replaced in about 1899. As a community focal point, the store became the post office of Lake, Idaho. Sherwood was named the postmaster.

Along with his wife Susan, Sherwood built a going enterprise. They raised cattle and in something of a precursor to Idaho’s famous Magic Valley trout farms, Sherwood packaged fish caught by locals and shipped them off to customers in Montana and California. This was no small operation. Sherwood once wrote in a letter that “The amount of fish usually caught in winter here varies from 50 to 90,000 pounds.”

Sherwood also ran a sawmill that was powered by gravity-fed water running in a canvas flume from a series of ponds he had developed above his place. He sold lumber commercially and used the sawmill to build his store.

And what a building it was—and is. It has since been modified, but the structure built in 1899 was 55 feet wide, 37 feet deep, and 46 feet high. It contained 27 rooms. The general store and post office was on the first floor, along with a family living area. The second floor had four bedrooms for rental to overnight stagecoach guests, a display room for Sherwood’s taxidermy, a photographic darkroom, and a photo gallery. A half-story attic was used for storage.

The store and museum was the home base for Sherwood’s boats. He rented them and often took visitors out on the lake from his launch.

About that taxidermy… Sherwood took a correspondence course to learn how to do it. He shared his knowledge with his second wife, Ann, after Susan’s death. Together they set out to mount at least once specimen of every critter native to Island Park. That room full of taxidermy mounts was why the store was often called the Sherwood Museum.

To say that Joseph Sherwood was self-sufficient would be like saying there were a few fish in Henrys Lake. One story, told in the National Register of Historic Places application for his building, was about his medical skills. He delivered he and Ann’s children himself, including Clarence Sherwood, who told this story. One day his father was thrown from a wagon some distance from their home. Joseph Sherwood fashioned a splint for his leg, got back into his wagon, and drove home. When he got home, with Ann’s help he set his leg. Then he hopped back in the wagon and headed for St. Anthony to attend a board meeting of the local bank, where he served as president.

Tomorrow I’ll conclude the Joseph Sherwood story with a little bit about his inventions.

Joseph Sherwood’s store as it appeared in the application for its listing on the National Register of Historic Places. It was approved for that listing in 1996.

Joseph Sherwood’s store as it appeared in the application for its listing on the National Register of Historic Places. It was approved for that listing in 1996.

Published on October 11, 2022 04:00

October 10, 2022

Hemingway's Cats (Tap to read)

Give me one word that you associate with Ernest Hemingway. Writer? Outdoorsman? Fishing? Hunting?

How about, cats? If you look hard enough you can find a picture of Hemingway with a hunting dog, but you'll find many pictures of him with his cats or just pictures of his cats. Here are a few I thought you might enjoy.

Ernest Hemingway’s cat Big Boy Peterson sits among papers in front of a window with a view of Bald Mountain at Hemingway’s home in Ketchum, Idaho, undated. Ernest Hemingway Photographs Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

Ernest Hemingway’s cat Big Boy Peterson sits among papers in front of a window with a view of Bald Mountain at Hemingway’s home in Ketchum, Idaho, undated. Ernest Hemingway Photographs Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.  Ernest Hemingway and his cat, Boise, outside his home, Finca Vigia, in Cuba. Ernest Hemingway Photographs Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

Ernest Hemingway and his cat, Boise, outside his home, Finca Vigia, in Cuba. Ernest Hemingway Photographs Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.  Patrick “Mouse” Hemingway, Ernest Hemingway, and Gregory “Gigi” Hemingway with three cats (Good Will, Princessa, and Boise) at Finca Vigia, Cuba, November 1946. Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

Patrick “Mouse” Hemingway, Ernest Hemingway, and Gregory “Gigi” Hemingway with three cats (Good Will, Princessa, and Boise) at Finca Vigia, Cuba, November 1946. Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.  Mary Hemingway with cat, Boise. Finca Vigia, San Francisco de Paula, Cuba. Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

Mary Hemingway with cat, Boise. Finca Vigia, San Francisco de Paula, Cuba. Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.  A whole lot of cats with Mary Welsh Hemingway in the doorway. Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

A whole lot of cats with Mary Welsh Hemingway in the doorway. Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

How about, cats? If you look hard enough you can find a picture of Hemingway with a hunting dog, but you'll find many pictures of him with his cats or just pictures of his cats. Here are a few I thought you might enjoy.

Ernest Hemingway’s cat Big Boy Peterson sits among papers in front of a window with a view of Bald Mountain at Hemingway’s home in Ketchum, Idaho, undated. Ernest Hemingway Photographs Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

Ernest Hemingway’s cat Big Boy Peterson sits among papers in front of a window with a view of Bald Mountain at Hemingway’s home in Ketchum, Idaho, undated. Ernest Hemingway Photographs Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.  Ernest Hemingway and his cat, Boise, outside his home, Finca Vigia, in Cuba. Ernest Hemingway Photographs Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

Ernest Hemingway and his cat, Boise, outside his home, Finca Vigia, in Cuba. Ernest Hemingway Photographs Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.  Patrick “Mouse” Hemingway, Ernest Hemingway, and Gregory “Gigi” Hemingway with three cats (Good Will, Princessa, and Boise) at Finca Vigia, Cuba, November 1946. Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

Patrick “Mouse” Hemingway, Ernest Hemingway, and Gregory “Gigi” Hemingway with three cats (Good Will, Princessa, and Boise) at Finca Vigia, Cuba, November 1946. Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.  Mary Hemingway with cat, Boise. Finca Vigia, San Francisco de Paula, Cuba. Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

Mary Hemingway with cat, Boise. Finca Vigia, San Francisco de Paula, Cuba. Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.  A whole lot of cats with Mary Welsh Hemingway in the doorway. Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

A whole lot of cats with Mary Welsh Hemingway in the doorway. Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

Published on October 10, 2022 04:00

October 9, 2022

The Guv's House (Tap to read)

The Pierce House was built in 1914 as a wedding present for the bride of Walter E. Pierce. Pierce had come to Boise in 1890 with ambitions to be instrumental in the building of a city. He was a young developer itching to ply his trade in the West. He probably picked Boise because it was about to become the capitol city of the country’s newest state.

With his partners, Lindley H. Cox and John M. Haines, doing business as W.E. Pierce and Company, he developed most of the North End’s subdivisions and platted others along State Street and in the East End. He was at one time the owner of Boise’s Natatorium and was a principle in the Boise & Interurban. Pierce was also instrumental in the development of the Hotel Boise, today known as the Hoff Building.

But this is about Pierce House, which served as the Governor’s House from 1947 to 1989. Built for $11,000 in 1914, it was sold it to the State of Idaho by a subsequent owner in 1947 for $25,000. It needed some major upgrades, including a new heating system.

Having a residence for a governor at all was novel for Idaho. Governors lived in their own homes during most of Idaho’s early history. If they didn’t already live in Boise, finding housing was sometimes difficult. C.A. Bottleson, a newspaper publisher from Arco, lived in the Owyhee Hotel during his first term and at the Hotel Boise (thank you Walter Pierce) during his second term. His successor, Arnold Williams, lived with his wife in a remodeled garage while serving as governor.

C.A. Robbins was the first Idaho governor to take up residence at 21st and Irene. The Len B. Jordan family was next. The Robert E. Smylie family called the place home for three terms. When the Samuelsons moved in, Ruby Samuelson took it on as a project to equip the house with the necessities for hosting state dinners, this in spite of the fact that hosting much more than a family dinner was a challenge in the home. She raised funds for the purchase of china, crystal, sliver, and other permanent furnishings for the Governor’s House, much of it featuring the state seal. Mrs. Samuelson raised more than $4,000 for that purpose.

Having a nice set of dinnerware didn’t make the house much more useable for state functions in the opinion of Carol Andrus, the next first lady to live there. It was still small, and as Mrs. Andrus said, “If you plug two teapots into one plug-in in the kitchen, you blow a fuse.”

When Andrus was appointed Secretary of the Interior by President Jimmy Carter in 1977—the first Idahoan to hold a cabinet position—John and Lola Evans moved into the Pierce House. They were the last governor and first lady to occupy it. Andrus was elected governor again and began serving the third of his four terms in 1987. He and Carol were not interested in moving back into the Pierce House, and it was sold in 1989.

Though J.R. Simplot donated his grand house on the hill overlooking Boise in 2004 for use as the governor’s mansion, it had a lot of issues that precluded that use. It was given back to the Simplot family in 2016 and soon after demolished.

Providing Idaho’s governor with an official residence has not been a burning issue for many years.

With his partners, Lindley H. Cox and John M. Haines, doing business as W.E. Pierce and Company, he developed most of the North End’s subdivisions and platted others along State Street and in the East End. He was at one time the owner of Boise’s Natatorium and was a principle in the Boise & Interurban. Pierce was also instrumental in the development of the Hotel Boise, today known as the Hoff Building.

But this is about Pierce House, which served as the Governor’s House from 1947 to 1989. Built for $11,000 in 1914, it was sold it to the State of Idaho by a subsequent owner in 1947 for $25,000. It needed some major upgrades, including a new heating system.

Having a residence for a governor at all was novel for Idaho. Governors lived in their own homes during most of Idaho’s early history. If they didn’t already live in Boise, finding housing was sometimes difficult. C.A. Bottleson, a newspaper publisher from Arco, lived in the Owyhee Hotel during his first term and at the Hotel Boise (thank you Walter Pierce) during his second term. His successor, Arnold Williams, lived with his wife in a remodeled garage while serving as governor.

C.A. Robbins was the first Idaho governor to take up residence at 21st and Irene. The Len B. Jordan family was next. The Robert E. Smylie family called the place home for three terms. When the Samuelsons moved in, Ruby Samuelson took it on as a project to equip the house with the necessities for hosting state dinners, this in spite of the fact that hosting much more than a family dinner was a challenge in the home. She raised funds for the purchase of china, crystal, sliver, and other permanent furnishings for the Governor’s House, much of it featuring the state seal. Mrs. Samuelson raised more than $4,000 for that purpose.

Having a nice set of dinnerware didn’t make the house much more useable for state functions in the opinion of Carol Andrus, the next first lady to live there. It was still small, and as Mrs. Andrus said, “If you plug two teapots into one plug-in in the kitchen, you blow a fuse.”

When Andrus was appointed Secretary of the Interior by President Jimmy Carter in 1977—the first Idahoan to hold a cabinet position—John and Lola Evans moved into the Pierce House. They were the last governor and first lady to occupy it. Andrus was elected governor again and began serving the third of his four terms in 1987. He and Carol were not interested in moving back into the Pierce House, and it was sold in 1989.

Though J.R. Simplot donated his grand house on the hill overlooking Boise in 2004 for use as the governor’s mansion, it had a lot of issues that precluded that use. It was given back to the Simplot family in 2016 and soon after demolished.

Providing Idaho’s governor with an official residence has not been a burning issue for many years.

Published on October 09, 2022 04:00