Rick Just's Blog, page 77

November 17, 2022

Importing Pheasants (Tap to read)

Countless species have been introduced into Idaho accidently and intentionally, often to the detriment of native plants and animals. Exotic species can be an enormous problem because they often nudge out existing flora and fauna, taking over a niche and exploiting some advantage to become a nuisance if not a threat. At the top of the list in Idaho is probably cheatgrass. We are aware of this today and go to great lengths to fight invasive species, such as zebra mussels. The Idaho Department of Fish and Game is one of several state agencies engaged in such fights.

It wasn’t always so.

In the early part of the 20th Century, Fish and Game—a much looser, less scientific entity then—went to some trouble to import an exotic species that is so common today that many people likely think it is native: the ring-necked pheasant, a native of Asia.

Pheasants have been in the U.S. since about 1773, though they didn’t really become common until the 1800s in the East. The birds with their extravagant tail feathers came West in 1881, but not under their own power. They were imported first into Oregon.

Idaho’s state game warden hatched a plan to hatch some pheasants in 1907, hoping to provide sport for hunters. There were likely a few pheasants in Idaho before that, perhaps moving in from Washington and Oregon. They may have also escaped or been set free from amateur breeding operations. A Lewiston hunting club imported some for the sport of its members. Farmers could buy pheasant eggs and read about how to raise pheasants in the Gem State Rural.

Other states had set up hatchery programs, so Idaho had some clues as to how to do it. Deputy State Game Warden B.T. Livingston set out on January 21 for Corvallis, Oregon to pick up 225 English and China pheasants. Forty pens had been set up on leased land on the G.A. Stevens farm just west of Boise. Each pen was 16 feet square and 6 ½ feet high. Wire netting kept the birds in while a few boards provided shelter from the sun and rain. To raise more chicks, pheasant eggs were gathered once they appeared, and placed under regular chickens to hatch.

To avoid unnecessary ruffling of feathers, the Oregon Shortline train carrying the cargo of exotic birds made a special stop at the Stevens farm to unload its cargo rather than offloading them at the depot and hauling them back by wagon.

Even with careful care the birds didn’t do very well that first year. The state hired a pheasant specialist to oversee the breeding operation. Additional hatcheries popped up across Southern Idaho in subsequent years to increase the release of the birds into the wild.

By 1910 pheasants were thriving and breeding rapidly. They were touted as a benefit to farmers because of the thousands of insects they eat. In 1911, “bird fancier” Roland Voddard, was travelling the state talking up pheasants to farmers. Several started raising and releasing them into their fields to go after grasshoppers, particularly. Voddard was quoted in the Idaho Statesman as saying, “The pheasants will form a mighty good advance army for the work in this state as they have elsewhere. They are not a crop-destroying bird and will not dig up the grain as will chickens if they are left in the fields.”

Well, that was one opinion. By 1918, the Farm Bureau had declared war on pheasants. Farmers in the Magic Valley had come to believe that the pest-eating function of pheasants was negligible, while their love of grain was a real problem. It was said that mother pheasants had a strategy of flying up through the stands of grain, knocking against the seeds with their wings, and scattering it to be consumed by their chicks.

That same year the Twin Falls Weekly News published a recipe to make a coal tar and linseed oil mix with which farmers could coat corn. This was said to make it unpalatable to pheasants and not affect its ability to germinate.

At the time, there was no hunting season on the birds. They were protected so that their population would increase. The Farm Bureau lobbied to get a season established to help control the pesky birds. Allowing hunters to shoot them had always been the plan, so hunting seasons for pheasants began.

Pheasants remain a popular game bird today. Fish and Game releases thousands of them into the wild every year. In 2020 they released 34,000 birds.

In 1909, the third year of the pheasant stocking program in Idaho, the state imported 1,000 birds in a special train car. Idaho Fish and Game Photo.

In 1909, the third year of the pheasant stocking program in Idaho, the state imported 1,000 birds in a special train car. Idaho Fish and Game Photo.

It wasn’t always so.

In the early part of the 20th Century, Fish and Game—a much looser, less scientific entity then—went to some trouble to import an exotic species that is so common today that many people likely think it is native: the ring-necked pheasant, a native of Asia.

Pheasants have been in the U.S. since about 1773, though they didn’t really become common until the 1800s in the East. The birds with their extravagant tail feathers came West in 1881, but not under their own power. They were imported first into Oregon.

Idaho’s state game warden hatched a plan to hatch some pheasants in 1907, hoping to provide sport for hunters. There were likely a few pheasants in Idaho before that, perhaps moving in from Washington and Oregon. They may have also escaped or been set free from amateur breeding operations. A Lewiston hunting club imported some for the sport of its members. Farmers could buy pheasant eggs and read about how to raise pheasants in the Gem State Rural.

Other states had set up hatchery programs, so Idaho had some clues as to how to do it. Deputy State Game Warden B.T. Livingston set out on January 21 for Corvallis, Oregon to pick up 225 English and China pheasants. Forty pens had been set up on leased land on the G.A. Stevens farm just west of Boise. Each pen was 16 feet square and 6 ½ feet high. Wire netting kept the birds in while a few boards provided shelter from the sun and rain. To raise more chicks, pheasant eggs were gathered once they appeared, and placed under regular chickens to hatch.

To avoid unnecessary ruffling of feathers, the Oregon Shortline train carrying the cargo of exotic birds made a special stop at the Stevens farm to unload its cargo rather than offloading them at the depot and hauling them back by wagon.

Even with careful care the birds didn’t do very well that first year. The state hired a pheasant specialist to oversee the breeding operation. Additional hatcheries popped up across Southern Idaho in subsequent years to increase the release of the birds into the wild.

By 1910 pheasants were thriving and breeding rapidly. They were touted as a benefit to farmers because of the thousands of insects they eat. In 1911, “bird fancier” Roland Voddard, was travelling the state talking up pheasants to farmers. Several started raising and releasing them into their fields to go after grasshoppers, particularly. Voddard was quoted in the Idaho Statesman as saying, “The pheasants will form a mighty good advance army for the work in this state as they have elsewhere. They are not a crop-destroying bird and will not dig up the grain as will chickens if they are left in the fields.”

Well, that was one opinion. By 1918, the Farm Bureau had declared war on pheasants. Farmers in the Magic Valley had come to believe that the pest-eating function of pheasants was negligible, while their love of grain was a real problem. It was said that mother pheasants had a strategy of flying up through the stands of grain, knocking against the seeds with their wings, and scattering it to be consumed by their chicks.

That same year the Twin Falls Weekly News published a recipe to make a coal tar and linseed oil mix with which farmers could coat corn. This was said to make it unpalatable to pheasants and not affect its ability to germinate.

At the time, there was no hunting season on the birds. They were protected so that their population would increase. The Farm Bureau lobbied to get a season established to help control the pesky birds. Allowing hunters to shoot them had always been the plan, so hunting seasons for pheasants began.

Pheasants remain a popular game bird today. Fish and Game releases thousands of them into the wild every year. In 2020 they released 34,000 birds.

In 1909, the third year of the pheasant stocking program in Idaho, the state imported 1,000 birds in a special train car. Idaho Fish and Game Photo.

In 1909, the third year of the pheasant stocking program in Idaho, the state imported 1,000 birds in a special train car. Idaho Fish and Game Photo.

Published on November 17, 2022 04:00

November 16, 2022

Fearless Farris, Cropduster (Tap to read)

Farris Lind, famous for his humorous signs advertising his Stinker Stations in Idaho, was a man of many interests. He was a flight instructor in World War II. Following the war, he saw an opportunity in the availability of cheap, surplus airplanes. He started Fearless Farris Crop Dusting in Twin Falls. His original planes were surplus Piper Cubs, but he soon graduated to biplanes.

He had a thriving business for a few years, but it began to seem more of a liability than an asset when a series of crashes destroyed several planes and killed a couple of his pilots. Only Llyods of London would insure the business. Lind eventually decided to focus on his gas stations and sold off his fleet of planes.

For more stories about Farris Lind, pick up a copy of the biography I wrote about him. You can buy a signed copy on this page, or order a copy of Fearless: Farris Lind, the Man Behind the Skunk from Amazon or your local bookseller.

Farris Lind clowning around in one his crashed biplanes.

Farris Lind clowning around in one his crashed biplanes.  Lind started his business with Army surplus Piper Cubs.

Lind started his business with Army surplus Piper Cubs.  Lind flying one of his spray planes. He gave himself the nickname Fearless Farris, not because of his flying exploits, but because he liked the alliteration.

Lind flying one of his spray planes. He gave himself the nickname Fearless Farris, not because of his flying exploits, but because he liked the alliteration.  The headquarters for Lind’s crop dusting business.

The headquarters for Lind’s crop dusting business.

He had a thriving business for a few years, but it began to seem more of a liability than an asset when a series of crashes destroyed several planes and killed a couple of his pilots. Only Llyods of London would insure the business. Lind eventually decided to focus on his gas stations and sold off his fleet of planes.

For more stories about Farris Lind, pick up a copy of the biography I wrote about him. You can buy a signed copy on this page, or order a copy of Fearless: Farris Lind, the Man Behind the Skunk from Amazon or your local bookseller.

Farris Lind clowning around in one his crashed biplanes.

Farris Lind clowning around in one his crashed biplanes.  Lind started his business with Army surplus Piper Cubs.

Lind started his business with Army surplus Piper Cubs.  Lind flying one of his spray planes. He gave himself the nickname Fearless Farris, not because of his flying exploits, but because he liked the alliteration.

Lind flying one of his spray planes. He gave himself the nickname Fearless Farris, not because of his flying exploits, but because he liked the alliteration.  The headquarters for Lind’s crop dusting business.

The headquarters for Lind’s crop dusting business.

Published on November 16, 2022 04:00

November 15, 2022

Chautauquas in the Treasure Valley (Tap to read)

Chautauquas in the Treasure Valley during the early part of the 20th Century offered so much education and entertainment that, described in today’s terms, they were Ted Talks, the Osher Institute, Toastmasters, Khan Academy, the Shakespeare Festival, Treefort, and the Cabin Readings and Conversations all rolled into one. Author Dick d’Easum wrote, “When Chautauqua was in flower it must be remembered that radio was in its infancy, television was unborn, and the automobile was a box mounted on punctures.”

These travelling congregations of culture were started by a Methodist minister, John Heyl Vincent, and a local businessman, Lewis Miller at Chautauqua Lake, New York in 1874. It began as an outdoor summer school for Sunday school teachers. With those religious roots, it’s not surprising that many Chautauquas had religious elements, and were sometimes sponsored by various denominations. Most had ample entertainment and educational opportunities for those with more secular tastes.

Best known for their temporary manifestations, Chautauquas could be almost anything in a community. Chautauqua Circle women’s clubs popped up around the country to discuss books and better themselves in order to change the world. Inmates started Chautauqua Societies in prison for self-improvement.

Travelling Chautauquas operated much like a circus sideshow, rolling into town with massive tents and the accoutrements of speakers, musicians, and entertainers. In smaller towns they would stay a day or two. In larger towns, they were usually the center of attention for a week.

The first Idaho State Chautauqua took place in Boise in 1910. It lasted nine days. In the buildup to the event promoters extolled the quality of the speakers and the variety of entertainment. Sometimes calling it “the people’s university,” they described three divisions of each day.

The morning section would feature classes and schools, mostly designed around the domestic sciences and agriculture, but also including athletic instruction, discussions about literature and history, as well as bible classes. The University of Idaho supplied many of the instructors. In the afternoon the heavier lectures for book lovers and those seeking knowledge took place. The evening was a time for entertainment from musical acts and theater companies.

As the event—encompassing July 4—grew nearer, local businesses began to promote it to their own benefit. Tie-ins sold everything from lace curtains to building lots to flour with specials during Chautauqua.

The main speaker of the Chautauqua was to be Idaho Senator W.E. Borah, but there was speculation about who else might show up at the last minute. William Jennings Bryan was among the most popular speakers at such events across the country. Another was Dr. Russell Conwell, famous for his “Acres of Diamonds” speech, the point of which was that one could seek fortune far and wide yet miss the acres of diamonds in one’s own backyard. He delivered it more than 5,000 times.

The Chautauqua included ball games, cavalry drills, chalk art exhibitions, fireworks, readings, fashion shows, concerts, political speeches, exhibits, and more. The Chinese community in Boise was joyful because they were able to procure a “monster dragon” to wind along the parade route on the Fourth of July.

One feature of the celebration visible at the major entertainment venues was the Chautauqua salute. The waving of white handkerchiefs was a tradition that had grown from an event years earlier at the suggestion that a deaf speaker could not hear the applause of a crowd. Since almost everyone carried a white handkerchief, the resulting flutter was a glorious sight.

Chautauquas thrived in Idaho and elsewhere for a few more years, waning in the mid-twenties only as other forms of entertainment, especially radio, came to the forefront.

The end of the Chautauquas was perhaps foreshadowed in 1925 in Boise when former baseball player turned evangelist Billy Sunday deplored the rise of jazz music. Later, in that same tent, a Boise audience clapped “until their hands were sore” for a jazz performance.

These travelling congregations of culture were started by a Methodist minister, John Heyl Vincent, and a local businessman, Lewis Miller at Chautauqua Lake, New York in 1874. It began as an outdoor summer school for Sunday school teachers. With those religious roots, it’s not surprising that many Chautauquas had religious elements, and were sometimes sponsored by various denominations. Most had ample entertainment and educational opportunities for those with more secular tastes.

Best known for their temporary manifestations, Chautauquas could be almost anything in a community. Chautauqua Circle women’s clubs popped up around the country to discuss books and better themselves in order to change the world. Inmates started Chautauqua Societies in prison for self-improvement.

Travelling Chautauquas operated much like a circus sideshow, rolling into town with massive tents and the accoutrements of speakers, musicians, and entertainers. In smaller towns they would stay a day or two. In larger towns, they were usually the center of attention for a week.

The first Idaho State Chautauqua took place in Boise in 1910. It lasted nine days. In the buildup to the event promoters extolled the quality of the speakers and the variety of entertainment. Sometimes calling it “the people’s university,” they described three divisions of each day.

The morning section would feature classes and schools, mostly designed around the domestic sciences and agriculture, but also including athletic instruction, discussions about literature and history, as well as bible classes. The University of Idaho supplied many of the instructors. In the afternoon the heavier lectures for book lovers and those seeking knowledge took place. The evening was a time for entertainment from musical acts and theater companies.

As the event—encompassing July 4—grew nearer, local businesses began to promote it to their own benefit. Tie-ins sold everything from lace curtains to building lots to flour with specials during Chautauqua.

The main speaker of the Chautauqua was to be Idaho Senator W.E. Borah, but there was speculation about who else might show up at the last minute. William Jennings Bryan was among the most popular speakers at such events across the country. Another was Dr. Russell Conwell, famous for his “Acres of Diamonds” speech, the point of which was that one could seek fortune far and wide yet miss the acres of diamonds in one’s own backyard. He delivered it more than 5,000 times.

The Chautauqua included ball games, cavalry drills, chalk art exhibitions, fireworks, readings, fashion shows, concerts, political speeches, exhibits, and more. The Chinese community in Boise was joyful because they were able to procure a “monster dragon” to wind along the parade route on the Fourth of July.

One feature of the celebration visible at the major entertainment venues was the Chautauqua salute. The waving of white handkerchiefs was a tradition that had grown from an event years earlier at the suggestion that a deaf speaker could not hear the applause of a crowd. Since almost everyone carried a white handkerchief, the resulting flutter was a glorious sight.

Chautauquas thrived in Idaho and elsewhere for a few more years, waning in the mid-twenties only as other forms of entertainment, especially radio, came to the forefront.

The end of the Chautauquas was perhaps foreshadowed in 1925 in Boise when former baseball player turned evangelist Billy Sunday deplored the rise of jazz music. Later, in that same tent, a Boise audience clapped “until their hands were sore” for a jazz performance.

Published on November 15, 2022 04:00

November 14, 2022

John Gideon's Career in Crime (Tap to read)

As villains go John Gideon barely qualified. He didn’t kill anyone; he didn’t even hurt anyone. His claim to fame was that he probably participated in one of the heaviest heists of any Idaho bad guy. And that wasn’t even in Idaho.

With a biblical surname and an employee of a mine called the Golden Rule, he really should have been a more upstanding citizen. It was the golden part of that mine name that caused his downfall, as it does so many.

In July 1905, a single bandit held up the Meadows-Warren stage. Hoping not to be recognized, the robber covered his entire face with a kerchief, not even bothering with eyeholes. The weave of the cloth was probably loose enough for him to see out without witness eyes seeing in well enough to identify him. To complete his outfit, the man brandished a mismatched pair of pistols.

The highwayman demanded that the driver of the coach “throw down the sack.” Pretending not to understand precisely what the bandit was after; the driver threw down a sack filled with bottles. This not being the exact sack the outlaw wanted, he specified that it was the registered mail bag that interested him. The driver reluctantly tossed that to the ground, at which point the bandit told him to jump down and open it.

Once the contents were revealed, the bandit signaled for the stage to move on down the road.

The robber made off with $300 in cash and $1,200 in gold, most of the latter being the property of the Golden Rule operation. That would be the equivalent of about $40,000 today.

John Gideon did not wait a tick to start spending money fast enough to draw suspicion onto himself. No one could identify the bandit, but they had little trouble identifying a shirt and pistols found in Gideon’s possession.

Many men in Idaho’s criminal history paid for murder with a few years in jail. Gideon paid a little more for the theft of gold and currency. Robbing the mail is and was a federal offense. He was convicted of the crime and given a life sentence.

Following the trial, which took place in federal court in Moscow, Gideon came close to a moment of excitement. He confided in a cellmate that he had committed the crime, but he didn’t intend to pay for it. He planned to stomp the leg of the federal marshal assigned to transport him to prison at McNeill’s Island in the Puget Sound, a federal facility. It was a real threat because Gideon would be wearing an Oregon Boot on his foot. That was an iron device designed to make escape more difficult. It was heavy enough to break the bone of a man who might drop his guard. Fortunately, the cellmate told the story before the train left with Gideon, making the marshal sufficiently leery of that booted foot.

After spending about a year in the lockup at McNeill’s Island, Gideon was transferred to the federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas. It was there that he found another day or two of fame.

On April 21, 1910, Gideon and five coconspirators overpowered a locomotive crew to make an escape. A switch engine was in the prison yard—probably not an uncommon occurrence, there being tracks to facilitate that. Using pistols carved for the occasion to look real, they pressed the barrels of the faux weapons into the necks of crew members. The engineer, valuing his life appropriately, crashed the steam engine through the closed prison gates.

The prisoners were not well-acquainted with train schedules, so did not know when or if an oncoming train might slam into them. One-by-one they jumped off the roaring train. They hadn’t gone more than a mile. All but one of them, including Gideon, were captured within a matter of hours.

The bold escape made headlines across the country, failed though it ultimately was. Perhaps the fame gave Gideon some satisfaction, though it clearly did not make up for a life in prison. He became, as they say, a model prisoner. In 1920, John Gideon walked away from the prison farm where he was working, never to be heard from again.

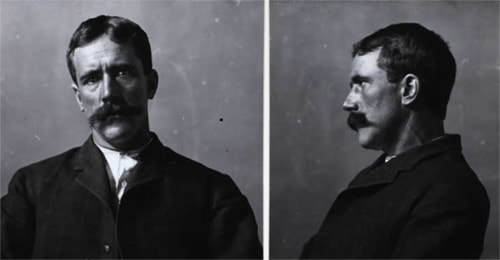

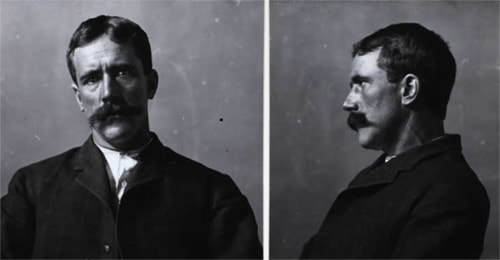

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, was taken while John Gideon was awaiting trial in 1905.

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, was taken while John Gideon was awaiting trial in 1905.

With a biblical surname and an employee of a mine called the Golden Rule, he really should have been a more upstanding citizen. It was the golden part of that mine name that caused his downfall, as it does so many.

In July 1905, a single bandit held up the Meadows-Warren stage. Hoping not to be recognized, the robber covered his entire face with a kerchief, not even bothering with eyeholes. The weave of the cloth was probably loose enough for him to see out without witness eyes seeing in well enough to identify him. To complete his outfit, the man brandished a mismatched pair of pistols.

The highwayman demanded that the driver of the coach “throw down the sack.” Pretending not to understand precisely what the bandit was after; the driver threw down a sack filled with bottles. This not being the exact sack the outlaw wanted, he specified that it was the registered mail bag that interested him. The driver reluctantly tossed that to the ground, at which point the bandit told him to jump down and open it.

Once the contents were revealed, the bandit signaled for the stage to move on down the road.

The robber made off with $300 in cash and $1,200 in gold, most of the latter being the property of the Golden Rule operation. That would be the equivalent of about $40,000 today.

John Gideon did not wait a tick to start spending money fast enough to draw suspicion onto himself. No one could identify the bandit, but they had little trouble identifying a shirt and pistols found in Gideon’s possession.

Many men in Idaho’s criminal history paid for murder with a few years in jail. Gideon paid a little more for the theft of gold and currency. Robbing the mail is and was a federal offense. He was convicted of the crime and given a life sentence.

Following the trial, which took place in federal court in Moscow, Gideon came close to a moment of excitement. He confided in a cellmate that he had committed the crime, but he didn’t intend to pay for it. He planned to stomp the leg of the federal marshal assigned to transport him to prison at McNeill’s Island in the Puget Sound, a federal facility. It was a real threat because Gideon would be wearing an Oregon Boot on his foot. That was an iron device designed to make escape more difficult. It was heavy enough to break the bone of a man who might drop his guard. Fortunately, the cellmate told the story before the train left with Gideon, making the marshal sufficiently leery of that booted foot.

After spending about a year in the lockup at McNeill’s Island, Gideon was transferred to the federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas. It was there that he found another day or two of fame.

On April 21, 1910, Gideon and five coconspirators overpowered a locomotive crew to make an escape. A switch engine was in the prison yard—probably not an uncommon occurrence, there being tracks to facilitate that. Using pistols carved for the occasion to look real, they pressed the barrels of the faux weapons into the necks of crew members. The engineer, valuing his life appropriately, crashed the steam engine through the closed prison gates.

The prisoners were not well-acquainted with train schedules, so did not know when or if an oncoming train might slam into them. One-by-one they jumped off the roaring train. They hadn’t gone more than a mile. All but one of them, including Gideon, were captured within a matter of hours.

The bold escape made headlines across the country, failed though it ultimately was. Perhaps the fame gave Gideon some satisfaction, though it clearly did not make up for a life in prison. He became, as they say, a model prisoner. In 1920, John Gideon walked away from the prison farm where he was working, never to be heard from again.

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, was taken while John Gideon was awaiting trial in 1905.

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, was taken while John Gideon was awaiting trial in 1905.

Published on November 14, 2022 04:00

November 13, 2022

Two Train Wrecks, One Cause? (Tap to read)

In 1949, and again in 1951, head-on train crashes in Southern Idaho made headlines.

The first collision took place at 4:05 a.m. on January 30 in a lava rock cut-through about six miles west of American Falls. A westbound steam locomotive had been trying to climb the grade with little success, losing traction until the train came to a full stop. Crew members had reported their difficulty and noticed that a nearby signal had turned yellow. Engineer William Cramer wondered at first if a second locomotive had been sent from Pocatello to help them get up the grade. His story appeared in the Idaho State Journal on January 31.

“Then I saw the other freight about one half mile ahead of us as it rounded a curve,” Cramer said. “I knew it couldn’t stop in that short distance downhill, so I yelled to the fireman and brakeman, ‘get off, get off’

“They were working about five feet away, but they knew by my voice that we had to get off quick.”

The three jumped from the gangway of the cab and scrambled through about three feet of snow, getting about 30 feet from their abandoned engine.

“It seemed like Providence that we jumped on the south side,” Cramer said, “because most of the box cars piled up on the north side of our locomotive after the diesel telescoped into it.”

And there’s a point to remember. The stalled westbound engine was steam powered, while the speeding eastbound locomotive was powered by diesel.

The three trainmen in the diesel died in the smashup. The three who had jumped from the steam engine lived to tell the story.

Crews worked quickly to clear the tracks of the locomotives and 24 freight cars that had derailed. Railroad authorities set up a shuttle bus service from Pocatello to Shoshone to get some 400 people from scheduled passenger trains around the wreck. The line was cleared the next day.

Early estimates of the damage caused by the head-on collision were in excess of $1 million, making it Idaho’s most expensive train accident to date.

The second, eerily similar head-on collision between trains in Idaho occurred at Orchard, about 30 miles southeast of Boise on November 25, 1951. This time, both engines were diesel, and both were moving. The crew in the westbound freight spotted the oncoming engines and made an emergency stop. As that train was coming to a halt, Brakeman Ted Royter leapt from the four-engine train and ran to pull a switch that would route the eastbound engines onto a spur line. He arrived too late.

The grinding crash killed three crewmen in the lead eastbound engine and two in the westbound diesel cab. Of the 185 cars being pulled by the engines, 43 of them derailed, tearing up tracks as they tumbled and skidded. Three men in the caboose of the eastbound train escaped injury, as did two men in the westbound train’s caboose.

The sensational wreck, which happened on a Sunday, brought out carloads of people from Boise to see the pile-up. Police estimated that 5,000 people came to see the aftermath of the collision. A Boise camera club would later hold a special meeting to show photos club members had taken. (Note: If anyone has one, please post)

In both of the train wrecks all the crewmembers who might have shed some light on what happened perished in the collisions. There was no evidence that either of the engineers of the speeding trains had attempted to slow down.

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) investigated both wrecks without coming to a conclusion about the cause of either. But after the second collision the ICC “indulged in speculation,” according to the April 21, 1952 issue of Railway Age, a trade publication for the railroad industry. The investigators thought conditions might have been right for the occupants of both cabs of the diesel-electric locomotives to have been overcome by toxic gases seeping in from the train’s exhaust.

This speculation was bolstered by testimony of the operator at the Orchard station who tried to signal the speeding train to stop. It blew through the station without slowing down. The station operator did not see anyone in the cab and noted that all the windows and doors were closed.

The ICC’s report included weather conditions that indicated that the exhaust from the train could have travelled along with the engines because of the speed and direction of winds, finding its way into air vents. Under those conditions carbon monoxide poisoning could happen quickly and without preliminary symptoms. An autopsy had not been conducted on the engineers in either crash, so determining the exact cause of their incapacity—if they were indeed unable to control the engines—could not be determined.

The Times News carried the story of five men from Glenns Ferry being killed in the 1951 crash.

The Times News carried the story of five men from Glenns Ferry being killed in the 1951 crash.

The first collision took place at 4:05 a.m. on January 30 in a lava rock cut-through about six miles west of American Falls. A westbound steam locomotive had been trying to climb the grade with little success, losing traction until the train came to a full stop. Crew members had reported their difficulty and noticed that a nearby signal had turned yellow. Engineer William Cramer wondered at first if a second locomotive had been sent from Pocatello to help them get up the grade. His story appeared in the Idaho State Journal on January 31.

“Then I saw the other freight about one half mile ahead of us as it rounded a curve,” Cramer said. “I knew it couldn’t stop in that short distance downhill, so I yelled to the fireman and brakeman, ‘get off, get off’

“They were working about five feet away, but they knew by my voice that we had to get off quick.”

The three jumped from the gangway of the cab and scrambled through about three feet of snow, getting about 30 feet from their abandoned engine.

“It seemed like Providence that we jumped on the south side,” Cramer said, “because most of the box cars piled up on the north side of our locomotive after the diesel telescoped into it.”

And there’s a point to remember. The stalled westbound engine was steam powered, while the speeding eastbound locomotive was powered by diesel.

The three trainmen in the diesel died in the smashup. The three who had jumped from the steam engine lived to tell the story.

Crews worked quickly to clear the tracks of the locomotives and 24 freight cars that had derailed. Railroad authorities set up a shuttle bus service from Pocatello to Shoshone to get some 400 people from scheduled passenger trains around the wreck. The line was cleared the next day.

Early estimates of the damage caused by the head-on collision were in excess of $1 million, making it Idaho’s most expensive train accident to date.

The second, eerily similar head-on collision between trains in Idaho occurred at Orchard, about 30 miles southeast of Boise on November 25, 1951. This time, both engines were diesel, and both were moving. The crew in the westbound freight spotted the oncoming engines and made an emergency stop. As that train was coming to a halt, Brakeman Ted Royter leapt from the four-engine train and ran to pull a switch that would route the eastbound engines onto a spur line. He arrived too late.

The grinding crash killed three crewmen in the lead eastbound engine and two in the westbound diesel cab. Of the 185 cars being pulled by the engines, 43 of them derailed, tearing up tracks as they tumbled and skidded. Three men in the caboose of the eastbound train escaped injury, as did two men in the westbound train’s caboose.

The sensational wreck, which happened on a Sunday, brought out carloads of people from Boise to see the pile-up. Police estimated that 5,000 people came to see the aftermath of the collision. A Boise camera club would later hold a special meeting to show photos club members had taken. (Note: If anyone has one, please post)

In both of the train wrecks all the crewmembers who might have shed some light on what happened perished in the collisions. There was no evidence that either of the engineers of the speeding trains had attempted to slow down.

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) investigated both wrecks without coming to a conclusion about the cause of either. But after the second collision the ICC “indulged in speculation,” according to the April 21, 1952 issue of Railway Age, a trade publication for the railroad industry. The investigators thought conditions might have been right for the occupants of both cabs of the diesel-electric locomotives to have been overcome by toxic gases seeping in from the train’s exhaust.

This speculation was bolstered by testimony of the operator at the Orchard station who tried to signal the speeding train to stop. It blew through the station without slowing down. The station operator did not see anyone in the cab and noted that all the windows and doors were closed.

The ICC’s report included weather conditions that indicated that the exhaust from the train could have travelled along with the engines because of the speed and direction of winds, finding its way into air vents. Under those conditions carbon monoxide poisoning could happen quickly and without preliminary symptoms. An autopsy had not been conducted on the engineers in either crash, so determining the exact cause of their incapacity—if they were indeed unable to control the engines—could not be determined.

The Times News carried the story of five men from Glenns Ferry being killed in the 1951 crash.

The Times News carried the story of five men from Glenns Ferry being killed in the 1951 crash.

Published on November 13, 2022 04:00

November 12, 2022

The Table Rock Quarry (Tap to read)

The Jellison brothers, C.O., C.L., and E.A., homesteaded near Table Rock in the 1890s with a stone and timber claim. What timber there might have been is long gone, but the stone from the quarries they established is part of Boise’s foundation. So to speak.

Table Rock sandstone makes up the greater part of the old Idaho State Penitentiary, and is used to good effect in the Emmanuel Lutheran Church, the Bown House, St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, the Union Block, Boise City National Bank, the United States Assay Office, Temple Beth Israel, the Borah Building, St. John’s Cathedral, and many others.

In 1906, the Capitol Commission, in charge of building Idaho’s statehouse, purchased one of the Jellison Brothers’ quarries on Table Rock in order to facilitate the construction of Idaho’s seat of government. The Idaho State Capitol is probably the most visible and dramatic use of Table Rock sandstone in Boise.

Sandstone from Table Rock found its way to major buildings all over the state, including the First Presbyterian Church in Idaho Falls, the Administration Building and Brink Hall at the University of Idaho, and Strahorn Hall at the College of Idaho in Caldwell.

Out of state the stone went to a building on the campus of Yale University and was a popular construction material for several downtown Portland buildings.

Working in a quarry is dangerous, and it was often left to inmates at the Idaho State Penitentiary in the early days. In 1903, two inmates were “hurled into eternity” while working on a troublesome boulder. The 10-foot-high rock, said to be 25 feet square, had a crack running through the middle of it. Workers set charges in the split, hoping to blow the rock apart. The blasts had little effect. Inmates John Stewart and William Maney scrambled up to the top of the boulder to clear away rubble for another go at it. That was when the rock came apart, splitting in two and throwing the men 40 feet down the side of the ridge. Neither survived.

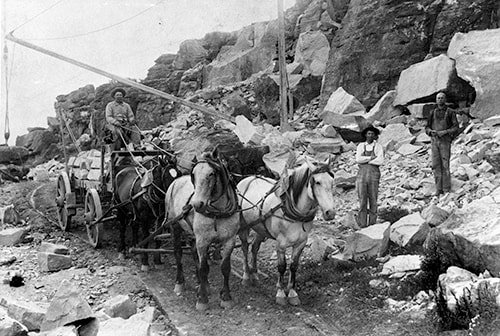

Manpower and horsepower moved a lot of rock from the quarries. In 1912, a new owner of one of the quarries, put electrical power to work. Harry K. Fritchman, a former mayor of Boise, constructed a tramway on rails from the quarry to the Oregon Shortline Railroad, more than a mile away. You can still see the scar of the tramway line on the southeast side of Table Rock.

Ambitious as the tramway was, it was not nearly as aspirational as an idea born in 1907. That year one of the Jellison brothers announced that he was going to build a luxury hotel on top of Table Rock. He envisioned spectacular views from the resort which would rise up from the center of a 685-acre parcel appropriately landscaped. An extension from the Boise Valley Electric line would run to the top of Table Rock and circle around the perimeter. One can imagine geothermal water from nearby wells heating pools and spas in the development. The quarry would be stubbed into the line for transport of stone.

Alas, 1907 was also the year of the “Banker’s Panic,” which sank big money plans like a rock. So, Table Rock is not known today for its splendid hotel. Its history is written in rock, though, still providing sandstone for Boise and beyond.

Wagons brought most of the stone off of Table Rock in the early days. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Wagons brought most of the stone off of Table Rock in the early days. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.  A tramway built in 1912 connected the Table Rock quarry with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Each flatbed car could carry 20 tons of rock. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

A tramway built in 1912 connected the Table Rock quarry with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Each flatbed car could carry 20 tons of rock. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Table Rock sandstone makes up the greater part of the old Idaho State Penitentiary, and is used to good effect in the Emmanuel Lutheran Church, the Bown House, St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, the Union Block, Boise City National Bank, the United States Assay Office, Temple Beth Israel, the Borah Building, St. John’s Cathedral, and many others.

In 1906, the Capitol Commission, in charge of building Idaho’s statehouse, purchased one of the Jellison Brothers’ quarries on Table Rock in order to facilitate the construction of Idaho’s seat of government. The Idaho State Capitol is probably the most visible and dramatic use of Table Rock sandstone in Boise.

Sandstone from Table Rock found its way to major buildings all over the state, including the First Presbyterian Church in Idaho Falls, the Administration Building and Brink Hall at the University of Idaho, and Strahorn Hall at the College of Idaho in Caldwell.

Out of state the stone went to a building on the campus of Yale University and was a popular construction material for several downtown Portland buildings.

Working in a quarry is dangerous, and it was often left to inmates at the Idaho State Penitentiary in the early days. In 1903, two inmates were “hurled into eternity” while working on a troublesome boulder. The 10-foot-high rock, said to be 25 feet square, had a crack running through the middle of it. Workers set charges in the split, hoping to blow the rock apart. The blasts had little effect. Inmates John Stewart and William Maney scrambled up to the top of the boulder to clear away rubble for another go at it. That was when the rock came apart, splitting in two and throwing the men 40 feet down the side of the ridge. Neither survived.

Manpower and horsepower moved a lot of rock from the quarries. In 1912, a new owner of one of the quarries, put electrical power to work. Harry K. Fritchman, a former mayor of Boise, constructed a tramway on rails from the quarry to the Oregon Shortline Railroad, more than a mile away. You can still see the scar of the tramway line on the southeast side of Table Rock.

Ambitious as the tramway was, it was not nearly as aspirational as an idea born in 1907. That year one of the Jellison brothers announced that he was going to build a luxury hotel on top of Table Rock. He envisioned spectacular views from the resort which would rise up from the center of a 685-acre parcel appropriately landscaped. An extension from the Boise Valley Electric line would run to the top of Table Rock and circle around the perimeter. One can imagine geothermal water from nearby wells heating pools and spas in the development. The quarry would be stubbed into the line for transport of stone.

Alas, 1907 was also the year of the “Banker’s Panic,” which sank big money plans like a rock. So, Table Rock is not known today for its splendid hotel. Its history is written in rock, though, still providing sandstone for Boise and beyond.

Wagons brought most of the stone off of Table Rock in the early days. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Wagons brought most of the stone off of Table Rock in the early days. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.  A tramway built in 1912 connected the Table Rock quarry with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Each flatbed car could carry 20 tons of rock. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

A tramway built in 1912 connected the Table Rock quarry with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Each flatbed car could carry 20 tons of rock. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on November 12, 2022 04:00

November 11, 2022

An Early Medal of Honor (Tap to read)

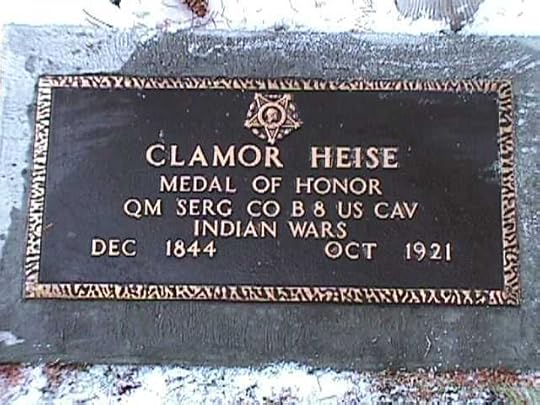

As I wrote in a previous post, Richard Clamor Heise was the founder of Heise Hot Springs in eastern Idaho. He is buried on the grounds of the resort.

One thing about Heise that may come as a surprise to many is that he was a Medal of Honor winner. The details of the action for which he was awarded the medal are sketchy. He was recognized for his service between August 13 and October 31, 1868 during the Indian Wars in the vicinity of the Black Mountains of Arizona. He was cited for “Bravery in scouts and actions against Indians.”

Heise’s actions may have well been heroic, but one must remember that the Medal of Honor requirements were less strict inn the early days of its existence. Heise was one of 40 soldiers of Company B, 8th US Cavalry who were so honored for their actions during that time and at that place.

One thing about Heise that may come as a surprise to many is that he was a Medal of Honor winner. The details of the action for which he was awarded the medal are sketchy. He was recognized for his service between August 13 and October 31, 1868 during the Indian Wars in the vicinity of the Black Mountains of Arizona. He was cited for “Bravery in scouts and actions against Indians.”

Heise’s actions may have well been heroic, but one must remember that the Medal of Honor requirements were less strict inn the early days of its existence. Heise was one of 40 soldiers of Company B, 8th US Cavalry who were so honored for their actions during that time and at that place.

Published on November 11, 2022 04:00

November 10, 2022

Red is Dead (Tap to read)

(Note: Today I’m running a guest blog written by Ben Knapp. Ben grew up in New Plymouth and lives in Boise. He has an associate degree from the College of Western Idaho and is a senior history major at BSU. Ben is the History Day associate coordinator for the Idaho State Historical Society. He interned for for Speaking of Idaho in 2021)

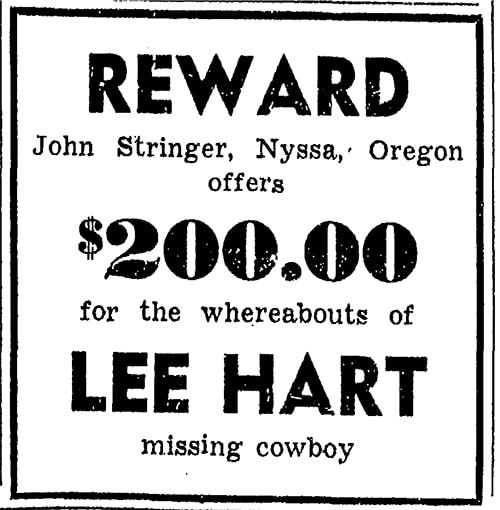

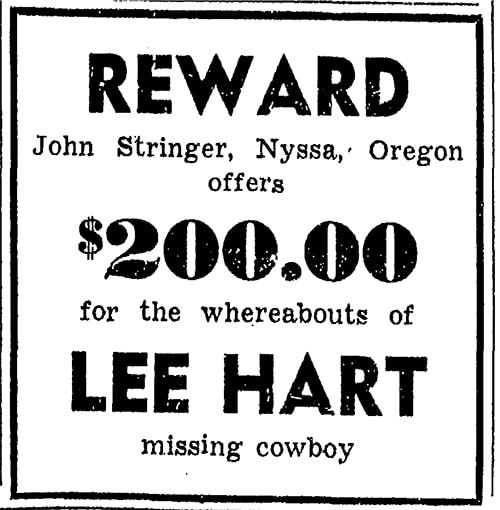

Red McCullough disappeared without a trace from the Sand Hollow area on October 28, 1945. McCullough was a tried and true cowboy, known for calf roping and cow cutting in the local rodeo scene. Nobody seemed to notice McCullough’s disappearance until his cattle partner and cabin-mate, Lee Hart, also vanished less than a month later. Once word spread about the two missing cowboys, the Washington County Sheriff opened an investigation into the matter.

The Sheriff recruited a posse of 20 men to search the surrounding area. They learned from a neighboring rancher that Hart was seen riding McCullough’s palomino stallion on November 18. The horse later returned to the neighbor’s ranch without a saddle or bridle. Two days later, on November 20, Hart briefly stopped at a friend’s house to eat a quick meal. There, Hart uttered three words that changed the Sheriff’s investigation from missing persons to homicide:

“Red is dead.”

A $200 reward was offered for information related to the whereabouts of McCullough, or Hart, and the Sheriff’s search intensified. Before long, the Sheriff theorized that the two men were both dead. He began probing reservoirs for signs of their bodies. On December 13, Hart was spotted nearly 160 miles south of his last known location in the Owyhee badlands. Five ranchers from that vicinity accurately described his appearance. By the next day, Hart was in law enforcement custody. He was found wandering in the desert between Murphy and Marsing.

Hart survived a total of 24 days on foot, without food or notable shelter. His only real protections against the elements were his trusty Levi overalls and a button up shirt. For sustenance, Hart ate rangeland grass by the handful. He once killed a porcupine with a club and cooked it on a small daytime fire, though he felt reluctant to ever light a fire at night. The Sheriff estimated that Hart walked a total of 500 winding miles. By the time he was found, Hart’s boots had given out, and his feet were badly frostbitten.

After eating his first real meal in over three weeks, Hart led the Sheriff and a small group of men to McCullough’s initial grave. It was less than a mile from the two cowboy’s shared cabin. He displayed disbelief that the body was missing. The coroner took a sample of dirt. When heated, it produced an odor which established that a body had been there for an unknown period of time. The next day Hart took the party to another shallow rock grave, located about five miles from the cabin. There, they found his body. It was evident that McCullough had died from a gunshot to the throat. Hart confessed that he was the person who fired the gun that killed his former partner, so he was formally arrested and charged with murder.

The question remained, why?

Hart claimed the killing was done in self defense. His attorney, future U.S. Senator Herman Welker of Payette, argued during the preliminary hearing that the charges should be dropped from murder to manslaughter. The Judge refused this request, and Hart’s jury trial was set for February. Hart was held without bail in the Washington County Jail for more than two months.

When February finally arrived, Hart pleaded his innocence. He entered the court wearing a brand new suit. True to his cowboy nature, Hart was quoted as saying, “I would feel a lot more comfortable if I was dressed in overalls, and had on my boots instead of these shoes.”

The prosecution sought a second degree murder charge, which carried a maximum penalty of life in prison. Their star witnesses were two high school students who were with McCullough earlier on the night of his death. The boys claimed McCullough became belligerently drunk at a local dance hall, so they escorted him back to his cabin. McCullough resisted, but Hart and the two boys convinced McCullough to stay. By the time the boys left, they claimed, Hart and McCullough had not started fighting.

Hart testified that McCullough wanted to sell his half of their cattle and leave their joint ranching operation. Hart suggested that McCullough sleep off his intoxication, and they could discuss the idea further the next day. This angered McCullough, Hart claimed, and McCullough “grabbed a rifle, and I grabbed a revolver and we started shooting. Red fell forward at my feet. I looked at him, saw he was dead, took a big drink of whisky and went to bed. The next morning I went out and fed the horses, and when I came back into the cabin and saw Red’s body lying there, I went loco crazy. I loaded his body on a horse, took it about a quarter of a mile away and buried it. Then I drank all the whisky I could pack.”

At that point, Hart said, he started hearing the voices of two imaginary men. These hallucinations convinced Hart to move McCullough’s body and eventually go on the run. Hart stated this was the first, and last, major disagreement he had ever had with McCullough. He finished his testimony by stating he “shot Red because he had a rifle and would have shot me.”

Hart’s defense revolved around this plea of insanity. Three doctors concurred that Hart was insane, either during or directly after the shooting. Two doctors disagreed, claiming Hart was fully “responsible except for the alcohol that was in him.” A total of seven other cowboys from Washington and Payette counties vouched that Hart was a peaceful and law abiding citizen, with generally good character and reputation.

At the conclusion of the trail, the Judge ordered the jury to return with one of four verdicts: guilty of murder in the second degree, guilty of voluntary manslaughter, guilty of involuntary manslaughter, or not guilty. The jury only deliberated for an hour before they returned with a “not guilty” acquittal verdict, and Hart and his new imaginary friends cheered.

Red McCullough disappeared without a trace from the Sand Hollow area on October 28, 1945. McCullough was a tried and true cowboy, known for calf roping and cow cutting in the local rodeo scene. Nobody seemed to notice McCullough’s disappearance until his cattle partner and cabin-mate, Lee Hart, also vanished less than a month later. Once word spread about the two missing cowboys, the Washington County Sheriff opened an investigation into the matter.

The Sheriff recruited a posse of 20 men to search the surrounding area. They learned from a neighboring rancher that Hart was seen riding McCullough’s palomino stallion on November 18. The horse later returned to the neighbor’s ranch without a saddle or bridle. Two days later, on November 20, Hart briefly stopped at a friend’s house to eat a quick meal. There, Hart uttered three words that changed the Sheriff’s investigation from missing persons to homicide:

“Red is dead.”

A $200 reward was offered for information related to the whereabouts of McCullough, or Hart, and the Sheriff’s search intensified. Before long, the Sheriff theorized that the two men were both dead. He began probing reservoirs for signs of their bodies. On December 13, Hart was spotted nearly 160 miles south of his last known location in the Owyhee badlands. Five ranchers from that vicinity accurately described his appearance. By the next day, Hart was in law enforcement custody. He was found wandering in the desert between Murphy and Marsing.

Hart survived a total of 24 days on foot, without food or notable shelter. His only real protections against the elements were his trusty Levi overalls and a button up shirt. For sustenance, Hart ate rangeland grass by the handful. He once killed a porcupine with a club and cooked it on a small daytime fire, though he felt reluctant to ever light a fire at night. The Sheriff estimated that Hart walked a total of 500 winding miles. By the time he was found, Hart’s boots had given out, and his feet were badly frostbitten.

After eating his first real meal in over three weeks, Hart led the Sheriff and a small group of men to McCullough’s initial grave. It was less than a mile from the two cowboy’s shared cabin. He displayed disbelief that the body was missing. The coroner took a sample of dirt. When heated, it produced an odor which established that a body had been there for an unknown period of time. The next day Hart took the party to another shallow rock grave, located about five miles from the cabin. There, they found his body. It was evident that McCullough had died from a gunshot to the throat. Hart confessed that he was the person who fired the gun that killed his former partner, so he was formally arrested and charged with murder.

The question remained, why?

Hart claimed the killing was done in self defense. His attorney, future U.S. Senator Herman Welker of Payette, argued during the preliminary hearing that the charges should be dropped from murder to manslaughter. The Judge refused this request, and Hart’s jury trial was set for February. Hart was held without bail in the Washington County Jail for more than two months.

When February finally arrived, Hart pleaded his innocence. He entered the court wearing a brand new suit. True to his cowboy nature, Hart was quoted as saying, “I would feel a lot more comfortable if I was dressed in overalls, and had on my boots instead of these shoes.”

The prosecution sought a second degree murder charge, which carried a maximum penalty of life in prison. Their star witnesses were two high school students who were with McCullough earlier on the night of his death. The boys claimed McCullough became belligerently drunk at a local dance hall, so they escorted him back to his cabin. McCullough resisted, but Hart and the two boys convinced McCullough to stay. By the time the boys left, they claimed, Hart and McCullough had not started fighting.

Hart testified that McCullough wanted to sell his half of their cattle and leave their joint ranching operation. Hart suggested that McCullough sleep off his intoxication, and they could discuss the idea further the next day. This angered McCullough, Hart claimed, and McCullough “grabbed a rifle, and I grabbed a revolver and we started shooting. Red fell forward at my feet. I looked at him, saw he was dead, took a big drink of whisky and went to bed. The next morning I went out and fed the horses, and when I came back into the cabin and saw Red’s body lying there, I went loco crazy. I loaded his body on a horse, took it about a quarter of a mile away and buried it. Then I drank all the whisky I could pack.”

At that point, Hart said, he started hearing the voices of two imaginary men. These hallucinations convinced Hart to move McCullough’s body and eventually go on the run. Hart stated this was the first, and last, major disagreement he had ever had with McCullough. He finished his testimony by stating he “shot Red because he had a rifle and would have shot me.”

Hart’s defense revolved around this plea of insanity. Three doctors concurred that Hart was insane, either during or directly after the shooting. Two doctors disagreed, claiming Hart was fully “responsible except for the alcohol that was in him.” A total of seven other cowboys from Washington and Payette counties vouched that Hart was a peaceful and law abiding citizen, with generally good character and reputation.

At the conclusion of the trail, the Judge ordered the jury to return with one of four verdicts: guilty of murder in the second degree, guilty of voluntary manslaughter, guilty of involuntary manslaughter, or not guilty. The jury only deliberated for an hour before they returned with a “not guilty” acquittal verdict, and Hart and his new imaginary friends cheered.

Published on November 10, 2022 04:00

November 9, 2022

The Tunnel Builder (Tap to read)

The Channel Tunnel between Great Britain and France is an engineering marvel that might have remained on the drawing board if it weren’t for the man who maintained his office in a converted home in Boise’s North End.

Jack Lemley graduated in 1960 from the University of Idaho with a degree in architecture. He worked for a few years as an engineer for a San Francisco company before moving his family to Boise in 1977 to take a job with Morrison Knudsen. He came on at MK as the executive vice president in charge of heavy construction. He managed major projects there until 1988 when he was passed over for the position of the CEO in favor of Bill Agee. One can’t help but wonder if MK would still be around if the decision had gone the other way.

Lemley’s resignation from MK came just in time for him to land the contract to supervise the construction of the Chunnel. It was about as big a job as they get. More than 15,000 people worked on the project. It resulted in two train tunnels and a service tunnel, more than 31 miles long and as deep 380 feet below sea level.

For his work on the project, Lemley was awarded the Order of Merit and Queen Elizabeth named him a Commander of the British Empire.

After the Chunnel was complete, Lemley became the CEO of U.S. Ecology in Houston. He moved the firm’s headquarters to Boise.

Even Boiseans who are well travelled probably see another project of Lemley’s much more often than they see the Chunnel. His firm designed and constructed the Idaho Water Center at the corner of Front and Broadway. It’s the home of the University of Idaho graduate engineering programs in Boise.

Lemley had his hand in dozens of major projects from Seattle’s Interstate-90 and Interstate-5 interchange to the Trans-Panama Pipeline.

A popular figure in Great Britain because of his success with the Chunnel project, Lemley was chosen to build the venues and infrastructure for the 2012 Olympics in London. Frustrated with political wrangling, he resigned the position in 2006.

Jack Lemley was inducted into the Idaho Hall of Fame in 1997 and into the Idaho Technology Council’s Hall of Fame in 2011.

Lemley’s son, Jim, is a manager of a different kind of big projects. He is a film producer best known for the Diving Bell and the Butterfly and Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Slayer.

Jack Lemley

Jack Lemley

Jack Lemley graduated in 1960 from the University of Idaho with a degree in architecture. He worked for a few years as an engineer for a San Francisco company before moving his family to Boise in 1977 to take a job with Morrison Knudsen. He came on at MK as the executive vice president in charge of heavy construction. He managed major projects there until 1988 when he was passed over for the position of the CEO in favor of Bill Agee. One can’t help but wonder if MK would still be around if the decision had gone the other way.

Lemley’s resignation from MK came just in time for him to land the contract to supervise the construction of the Chunnel. It was about as big a job as they get. More than 15,000 people worked on the project. It resulted in two train tunnels and a service tunnel, more than 31 miles long and as deep 380 feet below sea level.

For his work on the project, Lemley was awarded the Order of Merit and Queen Elizabeth named him a Commander of the British Empire.

After the Chunnel was complete, Lemley became the CEO of U.S. Ecology in Houston. He moved the firm’s headquarters to Boise.

Even Boiseans who are well travelled probably see another project of Lemley’s much more often than they see the Chunnel. His firm designed and constructed the Idaho Water Center at the corner of Front and Broadway. It’s the home of the University of Idaho graduate engineering programs in Boise.

Lemley had his hand in dozens of major projects from Seattle’s Interstate-90 and Interstate-5 interchange to the Trans-Panama Pipeline.

A popular figure in Great Britain because of his success with the Chunnel project, Lemley was chosen to build the venues and infrastructure for the 2012 Olympics in London. Frustrated with political wrangling, he resigned the position in 2006.

Jack Lemley was inducted into the Idaho Hall of Fame in 1997 and into the Idaho Technology Council’s Hall of Fame in 2011.

Lemley’s son, Jim, is a manager of a different kind of big projects. He is a film producer best known for the Diving Bell and the Butterfly and Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Slayer.

Jack Lemley

Jack Lemley

Published on November 09, 2022 04:00

November 8, 2022

The Idaho Buildings (Tap to read)

If you think of the Idaho Building at 8th and Bannock in Boise as THE Idaho Building, you’re missing a bit of history. The downtown Boise Building’s story goes back to 1910, when it replaced a livery barn. The building, designed by Tortellotte & Co., made the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

Today, we’re looking at three other Idaho Buildings that gained a measure of fame, none of them located in Idaho.

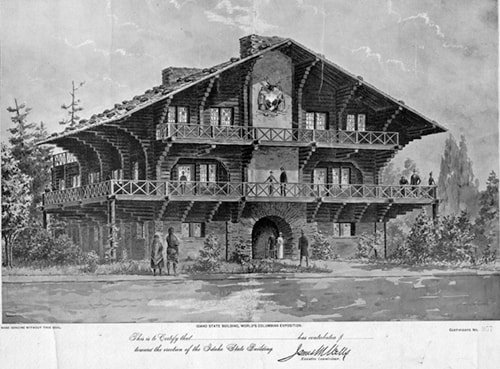

Giddy with statehood, Idaho was eager to participate in the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It was a celebration of the quadricentennial of Columbus’ “discovery” of the new world, albeit celebrated a year late.

The exhibition structure was designed by Spokane architect K.K. Cutter, but the Idaho Building was otherwise all Idaho. It used 22 types of lumber, all from Shoshone County. The stonework came from Nez Perce County and the foundation veneer was lava rock from Southern Idaho, which had an abundance.

The interior was uniquely Idaho. A frying pan clock with golden hands was set to Idaho time. The men’s reception room had a hunting knife for a latch. Some chairs were made from antlers and mountain lion skins. Guests drank from silver cups made in Idaho, until most of them disappeared. There was needlework from the ladies of Albion, watercolors of Idaho wildflowers from Post Falls, fossil rocks from Boise, and a mastodon tusk from Blackfoot.

Boise’s Columbian Club, which is active to this day, was named for its original mission, which was to furnish the Idaho Building.

The Columbian Exposition was billed as the “White City.” This huge log cabin drew attention to itself simply for not being white.

At the end of the exposition the building was taken down log by log and moved to… No, not some lake in Idaho. It was sold at auction and moved to Wisconsin where it was to be used on Lake Geneva as a retreat for orphaned boys. The wealthy owner who had it rebuilt on the lakeshore lost interest in the project, so the orphans never saw the building. It was used for a time as a residence for laborers building a road, then for ice storage. Somehow it got the reputation as being haunted by “Idaho cowboys.” That did not raise its resale value. In 1911, the building was torn down. Some of the logs were used for a municipal pier. The rest of the building seemed to vanish along with those ghosts.

But we have no time to mourn the demise of that Idaho Building. There were other expositions ahead that beckoned to chambers of commerce in Idaho.

The next Idaho building went up in 1904 at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Unlike the 1893 building, this one was modest in size. At 60 feet square, it was the smallest state exhibit at the celebration. Even so, it took second prize among those exhibits.

The hacienda style architecture of the ranch house was so popular the architect had more than 300 requests for the plans. With a roof of red clay tiles and an adobe exterior, it might as well have represented the Southwest. At the end of the exposition a Texan purchased the building for $6,940. It was moved piece-by-piece to San Antonio by rail. Rather than simply put it back together the buyer decided to make two houses out of it. The pair of homes are still standing side by side today on Beacon Hill.

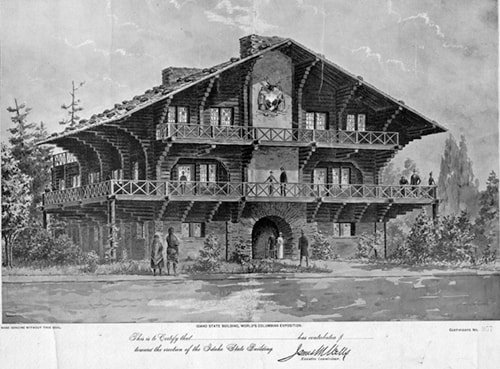

The third Idaho Building to appear in an exposition was closer to home. Idaho was represented at Portland’s 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition by a 100-foot by 60-foot building that resembled a Swiss chalet. Boise architects Wayland and Fennell designed it. Portland’s Idaho Building was noted for its striking colors, depicted in the hand-painted photo accompanying this article.

Idaho was generous with its $8,900 building, allowing Montana, Wyoming, and Nevada to use it for their state’s days at the fair. Several Idaho cities got use of the building on certain days, showing exhibits from Boise, Weiser, Pocatello, Wallace, Moscow, and Lewiston. The Idaho Statesman called the building “a cold-blooded business getter.” That was supposed to be a compliment.

The building generated a movement in Boise to have it brought to the city as a permanent exhibit. There was much excitement about this until it was pointed out that the Idaho Building was not meant to be a permanent structure. It wouldn’t stand being disassembled, transported, and reassembled, so the idea was abandoned. The structure, like many others at the exposition, was ultimately torn down.

So, this trio of Idaho buildings never made it to the state. We’ll have to be satisfied with the six-story Idaho Building in downtown Boise that was built to last, and hope it survives long into the future. It has already twice dodged a wrecking ball in the name of urban renewal.

This hand-colored black and white photo shows the Idaho Building that drew crowds at the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland in 1905. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

This hand-colored black and white photo shows the Idaho Building that drew crowds at the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland in 1905. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.  Those who contributed toward the construction of the Idaho Building featured in the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago got a certificate with a sketch of the grand structure. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Those who contributed toward the construction of the Idaho Building featured in the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago got a certificate with a sketch of the grand structure. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Today, we’re looking at three other Idaho Buildings that gained a measure of fame, none of them located in Idaho.

Giddy with statehood, Idaho was eager to participate in the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It was a celebration of the quadricentennial of Columbus’ “discovery” of the new world, albeit celebrated a year late.

The exhibition structure was designed by Spokane architect K.K. Cutter, but the Idaho Building was otherwise all Idaho. It used 22 types of lumber, all from Shoshone County. The stonework came from Nez Perce County and the foundation veneer was lava rock from Southern Idaho, which had an abundance.

The interior was uniquely Idaho. A frying pan clock with golden hands was set to Idaho time. The men’s reception room had a hunting knife for a latch. Some chairs were made from antlers and mountain lion skins. Guests drank from silver cups made in Idaho, until most of them disappeared. There was needlework from the ladies of Albion, watercolors of Idaho wildflowers from Post Falls, fossil rocks from Boise, and a mastodon tusk from Blackfoot.

Boise’s Columbian Club, which is active to this day, was named for its original mission, which was to furnish the Idaho Building.

The Columbian Exposition was billed as the “White City.” This huge log cabin drew attention to itself simply for not being white.

At the end of the exposition the building was taken down log by log and moved to… No, not some lake in Idaho. It was sold at auction and moved to Wisconsin where it was to be used on Lake Geneva as a retreat for orphaned boys. The wealthy owner who had it rebuilt on the lakeshore lost interest in the project, so the orphans never saw the building. It was used for a time as a residence for laborers building a road, then for ice storage. Somehow it got the reputation as being haunted by “Idaho cowboys.” That did not raise its resale value. In 1911, the building was torn down. Some of the logs were used for a municipal pier. The rest of the building seemed to vanish along with those ghosts.

But we have no time to mourn the demise of that Idaho Building. There were other expositions ahead that beckoned to chambers of commerce in Idaho.

The next Idaho building went up in 1904 at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Unlike the 1893 building, this one was modest in size. At 60 feet square, it was the smallest state exhibit at the celebration. Even so, it took second prize among those exhibits.

The hacienda style architecture of the ranch house was so popular the architect had more than 300 requests for the plans. With a roof of red clay tiles and an adobe exterior, it might as well have represented the Southwest. At the end of the exposition a Texan purchased the building for $6,940. It was moved piece-by-piece to San Antonio by rail. Rather than simply put it back together the buyer decided to make two houses out of it. The pair of homes are still standing side by side today on Beacon Hill.

The third Idaho Building to appear in an exposition was closer to home. Idaho was represented at Portland’s 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition by a 100-foot by 60-foot building that resembled a Swiss chalet. Boise architects Wayland and Fennell designed it. Portland’s Idaho Building was noted for its striking colors, depicted in the hand-painted photo accompanying this article.

Idaho was generous with its $8,900 building, allowing Montana, Wyoming, and Nevada to use it for their state’s days at the fair. Several Idaho cities got use of the building on certain days, showing exhibits from Boise, Weiser, Pocatello, Wallace, Moscow, and Lewiston. The Idaho Statesman called the building “a cold-blooded business getter.” That was supposed to be a compliment.

The building generated a movement in Boise to have it brought to the city as a permanent exhibit. There was much excitement about this until it was pointed out that the Idaho Building was not meant to be a permanent structure. It wouldn’t stand being disassembled, transported, and reassembled, so the idea was abandoned. The structure, like many others at the exposition, was ultimately torn down.

So, this trio of Idaho buildings never made it to the state. We’ll have to be satisfied with the six-story Idaho Building in downtown Boise that was built to last, and hope it survives long into the future. It has already twice dodged a wrecking ball in the name of urban renewal.

This hand-colored black and white photo shows the Idaho Building that drew crowds at the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland in 1905. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

This hand-colored black and white photo shows the Idaho Building that drew crowds at the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland in 1905. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.  Those who contributed toward the construction of the Idaho Building featured in the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago got a certificate with a sketch of the grand structure. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Those who contributed toward the construction of the Idaho Building featured in the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago got a certificate with a sketch of the grand structure. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on November 08, 2022 04:00