Rick Just's Blog, page 75

December 7, 2022

Feminine Vigilantes (tap to read)

There were many incidents of vigilantism in the old West, but as a rule few of the vigilantes were women. Here is an exception that proves the rule.

Sometime prior to 1898—the date is uncertain—a Montpelier saloon keep named John Lewis married a 15-year-old local girl, Afton Marie Murdock. Her parents were not happy with her marrying someone twice Marie’s age, but Bishop Henry J. Horne inexplicably performed the ceremony. Inexplicably, because John Lewis—remember that saloon—wasn’t even a Mormon.

The marriage and the saloon-keeping made Montpelier an uncomfortable place to live for the couple. They moved across the border to Fossil, Wyoming, a coal mining town.

Marie soon gave John Lewis a son, but the man did not seem happy about it, or anything else. Lewis was a vicious man as evidenced by the multiple bruises the town folk noticed on his two-year-old son. When some women saw Lewis kicking his wife, that put them over the edge.

Some 40 of the grabbed weapons at hand, buggy whips and razor strops, and marched to Lewis’ saloon. They drug the man into the street. He broke free, grabbed his sawed-off shotgun, and started to menace the women with it. His bartender grabbed the gun from the man. The women proceeded to break out the lights in the saloon and in the darkness destroyed it. Lewis, wisely, left town.

This little snippet of a story comes from Betty Penson Ward’s book Idaho Women in History by way of telling by Bear Lake High School teacher J. Patrick Wilde.

Sometime prior to 1898—the date is uncertain—a Montpelier saloon keep named John Lewis married a 15-year-old local girl, Afton Marie Murdock. Her parents were not happy with her marrying someone twice Marie’s age, but Bishop Henry J. Horne inexplicably performed the ceremony. Inexplicably, because John Lewis—remember that saloon—wasn’t even a Mormon.

The marriage and the saloon-keeping made Montpelier an uncomfortable place to live for the couple. They moved across the border to Fossil, Wyoming, a coal mining town.

Marie soon gave John Lewis a son, but the man did not seem happy about it, or anything else. Lewis was a vicious man as evidenced by the multiple bruises the town folk noticed on his two-year-old son. When some women saw Lewis kicking his wife, that put them over the edge.

Some 40 of the grabbed weapons at hand, buggy whips and razor strops, and marched to Lewis’ saloon. They drug the man into the street. He broke free, grabbed his sawed-off shotgun, and started to menace the women with it. His bartender grabbed the gun from the man. The women proceeded to break out the lights in the saloon and in the darkness destroyed it. Lewis, wisely, left town.

This little snippet of a story comes from Betty Penson Ward’s book Idaho Women in History by way of telling by Bear Lake High School teacher J. Patrick Wilde.

Published on December 07, 2022 04:00

December 6, 2022

The Wilson Creek Fire (tap to read)

The National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) in Boise is a logistics and communication control center for fighting wildfire all over the United States. Its methods of communication are parsecs from the way instructions were sent to firefighters in 1929.

The Wilson Creek Fire in 1929 on the Salmon National Forest burned about 13,000 acres. Today that would hardly make headlines, but it was the largest fire the Forest had experienced at that time.

Firefighters rode in the back of trucks to get within hiking distance of the lightning-caused fire. When they piled out of the trucks, they still had 18 miles to pack all their equipment.

Earl Nichols started work as a runner that year on the Wilson Creek Fire. His job was to get instructions to each of about 8 crews who were fighting the fires. There were no radios. The country was so steep that horses were more trouble than they were worth. He made his rounds on foot, carrying messages from camp to camp as fast as he could move. More than once when he got to where the camp was supposed to be, he found only ashes. He worked the fire on foot for sixty days. It was a tough job, but it did not discourage Nichols. He retired from the Forest Service in 1969 after a 40-year career.

The Wilson Creek Fire came close to taking the lives of three firefighters, Kinney, Coles, and Wilson. The fire crowned up a hill and around them. The men clung to the side of a large boulder, keeping it between them and the flames. When the fire shifted, they worked themselves around the other side of the rock. The men doused themselves with water from their canteens. Still, the heat swelled their eyes shut.

Other fire crew members set out to find them, certain it was a recovery mission. They spotted tracks in the hot ash and followed them to where the men were staggering blindly. The rescuers led the blistered men back to camp. Most of their clothing had burned off them. They survived and regained their sight once the swelling went town.

These vignettes about the Wilson Creek Fire come from oral histories collected by the Salmon National Forest.

The Wilson Creek Fire in 1929 on the Salmon National Forest burned about 13,000 acres. Today that would hardly make headlines, but it was the largest fire the Forest had experienced at that time.

Firefighters rode in the back of trucks to get within hiking distance of the lightning-caused fire. When they piled out of the trucks, they still had 18 miles to pack all their equipment.

Earl Nichols started work as a runner that year on the Wilson Creek Fire. His job was to get instructions to each of about 8 crews who were fighting the fires. There were no radios. The country was so steep that horses were more trouble than they were worth. He made his rounds on foot, carrying messages from camp to camp as fast as he could move. More than once when he got to where the camp was supposed to be, he found only ashes. He worked the fire on foot for sixty days. It was a tough job, but it did not discourage Nichols. He retired from the Forest Service in 1969 after a 40-year career.

The Wilson Creek Fire came close to taking the lives of three firefighters, Kinney, Coles, and Wilson. The fire crowned up a hill and around them. The men clung to the side of a large boulder, keeping it between them and the flames. When the fire shifted, they worked themselves around the other side of the rock. The men doused themselves with water from their canteens. Still, the heat swelled their eyes shut.

Other fire crew members set out to find them, certain it was a recovery mission. They spotted tracks in the hot ash and followed them to where the men were staggering blindly. The rescuers led the blistered men back to camp. Most of their clothing had burned off them. They survived and regained their sight once the swelling went town.

These vignettes about the Wilson Creek Fire come from oral histories collected by the Salmon National Forest.

Published on December 06, 2022 04:00

December 5, 2022

A Steamboat Collision (tap to read)

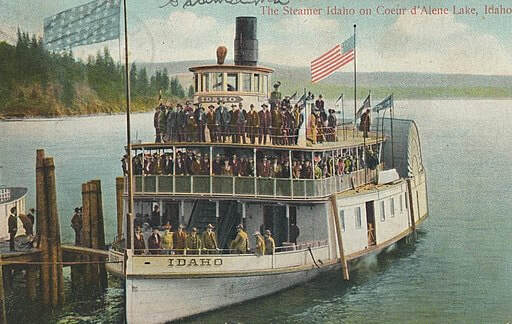

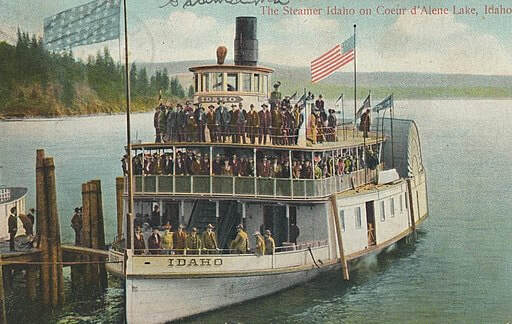

Monday, July 17, 1905, was a typical summer day on the St. Joe River. Steamboats were traveling up and down the "Shadowy" St. Joe, which locals claimed, incorrectly, to be the world's highest navigable river.

Captain George Reynolds was at the helm of the Bonita on her regular run up the river to St. Maries. He'd navigated those waters many times before and had held a master's license for 25 years. Reynolds was also part-owner of the boat, which had been constructed the summer before at Johnson's boat works in Coeur d'Alene. This was

the Bonita's first run in a few days, having spent some time getting a blown cylinder repaired.

Meanwhile, the fast steamer Idaho was on her regular run downstream on the St. Joe, captained by Jim Spaulding. The Idaho was a sidewheeler built-in 1903.

Reynolds was expecting to encounter the Idaho at any moment, given their common schedules. According to his account, he blew one long blast with his steam whistle to alert any boat that he was approaching a blind bend in the river known as Bend Wah, about three miles above Chatcolet Bridge.

"Just then, the Idaho hove in sight coming around the bend," Reynolds told the Coeur d'Alene Press. 111 then blew two whistles to pass her on my right. She answered the alarm whistle but never answered the passing whistle."

Both captains had different versions of what whistles blew when and what each meant. To say there was some confusion understates it.

Captain Spaulding refused to talk with the press. Red Collar Line management-the company that owned the Idaho-said they "did not care to enter into a newspaper controversy."

Captain Reynolds talked quite a lot, accusing the Idaho's captain of deliberately ramming the Bonita.

"When I saw that she was going to run me down if she kept on that course, I stopped my boat and backed, expecting that she would do the same, but she continued to come full head-on.

"I swung my boat across the river to try to avoid a collision.

The Idaho's pilot then swung the Idaho and followed me, still continuing to work his boat full steam ahead. Then when within 20 feet of me he stopped his engines."

The Idaho rammed into the Bonita, punching a big hole in the side of the boat about one-third of the way back from the bow. Captain Reynolds quickly grounded the Bonita. Still, she partially sank in about 15 feet of water.

Meanwhile, the Idaho paused long enough to be sure no one was injured, then continued on her way downriver, her bow scraped a bit and sporting a broken jackstaff . The five passengers who were on the Bonita were unhurt. A team of horses also rode out the collision with no injury.

The owners later raised the Bonita, and she began operating again on Lake Coeur d'Alene and the St. Joe. Although the arguments about who was to blame went to trial, the court could not determine culpability.

Captain George Reynolds was at the helm of the Bonita on her regular run up the river to St. Maries. He'd navigated those waters many times before and had held a master's license for 25 years. Reynolds was also part-owner of the boat, which had been constructed the summer before at Johnson's boat works in Coeur d'Alene. This was

the Bonita's first run in a few days, having spent some time getting a blown cylinder repaired.

Meanwhile, the fast steamer Idaho was on her regular run downstream on the St. Joe, captained by Jim Spaulding. The Idaho was a sidewheeler built-in 1903.

Reynolds was expecting to encounter the Idaho at any moment, given their common schedules. According to his account, he blew one long blast with his steam whistle to alert any boat that he was approaching a blind bend in the river known as Bend Wah, about three miles above Chatcolet Bridge.

"Just then, the Idaho hove in sight coming around the bend," Reynolds told the Coeur d'Alene Press. 111 then blew two whistles to pass her on my right. She answered the alarm whistle but never answered the passing whistle."

Both captains had different versions of what whistles blew when and what each meant. To say there was some confusion understates it.

Captain Spaulding refused to talk with the press. Red Collar Line management-the company that owned the Idaho-said they "did not care to enter into a newspaper controversy."

Captain Reynolds talked quite a lot, accusing the Idaho's captain of deliberately ramming the Bonita.

"When I saw that she was going to run me down if she kept on that course, I stopped my boat and backed, expecting that she would do the same, but she continued to come full head-on.

"I swung my boat across the river to try to avoid a collision.

The Idaho's pilot then swung the Idaho and followed me, still continuing to work his boat full steam ahead. Then when within 20 feet of me he stopped his engines."

The Idaho rammed into the Bonita, punching a big hole in the side of the boat about one-third of the way back from the bow. Captain Reynolds quickly grounded the Bonita. Still, she partially sank in about 15 feet of water.

Meanwhile, the Idaho paused long enough to be sure no one was injured, then continued on her way downriver, her bow scraped a bit and sporting a broken jackstaff . The five passengers who were on the Bonita were unhurt. A team of horses also rode out the collision with no injury.

The owners later raised the Bonita, and she began operating again on Lake Coeur d'Alene and the St. Joe. Although the arguments about who was to blame went to trial, the court could not determine culpability.

Published on December 05, 2022 04:00

December 4, 2022

Boise Welcomes (?) Jesse Owens (tap to read)

Jesse Owens was one the biggest Olympic heroes of all time. When he took four gold medals in the 1936 Olympics in Germany, it put the lie to Hitler’s claims of Aryan superiority.

After his Olympic success, Owens often struggled to make a living. For a time, he put on exhibitions where he traveled around the country racing local runners in the 100-yard dash, giving them a 20-yard head start. He also raced against horses, preferring thoroughbreds that tended to startle when the starting gun was fired. That gave him a little edge.

Owens took a little swing through Idaho in 1945, appearing in Idaho Falls, Payette, and Boise. In Payette, he beat Payette Lady, a thoroughbred owned by Ike Whiteley. No time for his run was recorded.

In Boise, the holder of seven world records, ran for a crowd of 3500 at Airway Park. His appearance in the Capitol City wasn’t against horses, but select members of the Globetrotters and Bearded Davidites, exhibition baseball teams. The Statesman reported that “Owens won as he pleased, crossing the line first in the century after giving his opponents a 10-yard lead; then running the low hurdles while two players ran on the flat and finally circling the bases against four opponents, each running only one base.”

The crowd applauded, glad to welcome Owens to Boise. But the welcome was not universal. No Boise hotel would rent a room to the Black man. He stayed instead with Warner and Clara Terrell in their house on 15th Street.

After his Olympic success, Owens often struggled to make a living. For a time, he put on exhibitions where he traveled around the country racing local runners in the 100-yard dash, giving them a 20-yard head start. He also raced against horses, preferring thoroughbreds that tended to startle when the starting gun was fired. That gave him a little edge.

Owens took a little swing through Idaho in 1945, appearing in Idaho Falls, Payette, and Boise. In Payette, he beat Payette Lady, a thoroughbred owned by Ike Whiteley. No time for his run was recorded.

In Boise, the holder of seven world records, ran for a crowd of 3500 at Airway Park. His appearance in the Capitol City wasn’t against horses, but select members of the Globetrotters and Bearded Davidites, exhibition baseball teams. The Statesman reported that “Owens won as he pleased, crossing the line first in the century after giving his opponents a 10-yard lead; then running the low hurdles while two players ran on the flat and finally circling the bases against four opponents, each running only one base.”

The crowd applauded, glad to welcome Owens to Boise. But the welcome was not universal. No Boise hotel would rent a room to the Black man. He stayed instead with Warner and Clara Terrell in their house on 15th Street.

Published on December 04, 2022 04:00

December 3, 2022

Ivory, Exploding Billiard Balls, and More! (tap to read)

I traveled down a path of good intentions today, trimmed in ivory. It led past the carcasses of elephants to gigatons of trash.

My exploration started with an article from a story in the August 4, 1864 edition of the Idaho Statesman. Headlined, “Where Our Ivory Comes From,” the piece caught my attention because I thought the answer was all too obvious. Ivory has been treasured by artisans for centuries because it is easy to carve yet durable. Elephants have been the largest source of ivory, though walrus, hippopotamus, narwhal, sperm whales, and elk all provide ivory. Providing it usually costs the animal its life.

But the 1864 article was not about elephants.

“You carry a beautiful cane—it cost $3.50—$1.50 extra, on account of its beautiful pure ivory head. Your wife has a costly fan, with a pure ivory handle. In your pocket is your pure ivory-handled pocketknife, very pretty and fine. On your table is a set of knives and forks with pure ivory handles, and little they have cost for being pure ivory. The ring in which are the reins of your costly double harness is pure ivory. The handles of parasols are pure ivory—and so on, with many articles useful and ornamental. But it happens that this “pure ivory” is manufactured from the shin bones of the dead horses of the U.S. Army.”

Well, that took a turn. I found the article by accident, which is often the case when I’m looking for interesting Idaho tidbits. I was searching for something about harness when this little piece popped up because it included that word in the text.

Encouraged by the quirkiness the article offered, I did a quick search on ivory. And that’s where the trouble began.

Early billiard balls were made of ivory. It gave the perfect heft, click, and bounce players enjoyed. But in the 1860s there was something of a billiard ball panic because ivory was allegedly in short supply. It wasn’t. Nevertheless, the belief that it was set billiard ball manufacturers on a quest for a material to replace ivory balls.

British inventor Alan Parkes came up with something he called Parkesine in 1862. It was the first plastic. It didn’t work well for billiard balls, so the quest was still on for the perfect synthetic material. John Wesley Hyatt, hoping to win a $10,000 prize from Big Billiard (a name I made up to represent the industry, so don’t call me on that) came up with celluloid. Celluloid is better known for its use in early motion picture film stock. That early film was highly flammable, and billiard balls made from celluloid had a similar, annoying feature. They exploded.

Exploding billiard balls would have been a health hazard for those who hung out in establishments where the game was played, but the explosions weren’t like grenades going off. They occasionally made a sharp pop, causing little damage even to the felt on billiard tables. The percussion sounded much like a gunshot, which reportedly caused quite a few “sports” to drop the hand of cards they’d been dealt to frantically look around the room.

Today, billiard balls are made from resin, another type of plastic. And, today, we are buried by plastic of all kinds because it shares something with the ivory it replaced. It is durable. Too durable, as it turns out.

One last note: Inventor John Wesley Hyatt never received the $10,000 prize, but he did start the Albany Billiard Ball Company. It stayed in business for 118 years.

My exploration started with an article from a story in the August 4, 1864 edition of the Idaho Statesman. Headlined, “Where Our Ivory Comes From,” the piece caught my attention because I thought the answer was all too obvious. Ivory has been treasured by artisans for centuries because it is easy to carve yet durable. Elephants have been the largest source of ivory, though walrus, hippopotamus, narwhal, sperm whales, and elk all provide ivory. Providing it usually costs the animal its life.

But the 1864 article was not about elephants.

“You carry a beautiful cane—it cost $3.50—$1.50 extra, on account of its beautiful pure ivory head. Your wife has a costly fan, with a pure ivory handle. In your pocket is your pure ivory-handled pocketknife, very pretty and fine. On your table is a set of knives and forks with pure ivory handles, and little they have cost for being pure ivory. The ring in which are the reins of your costly double harness is pure ivory. The handles of parasols are pure ivory—and so on, with many articles useful and ornamental. But it happens that this “pure ivory” is manufactured from the shin bones of the dead horses of the U.S. Army.”

Well, that took a turn. I found the article by accident, which is often the case when I’m looking for interesting Idaho tidbits. I was searching for something about harness when this little piece popped up because it included that word in the text.

Encouraged by the quirkiness the article offered, I did a quick search on ivory. And that’s where the trouble began.

Early billiard balls were made of ivory. It gave the perfect heft, click, and bounce players enjoyed. But in the 1860s there was something of a billiard ball panic because ivory was allegedly in short supply. It wasn’t. Nevertheless, the belief that it was set billiard ball manufacturers on a quest for a material to replace ivory balls.

British inventor Alan Parkes came up with something he called Parkesine in 1862. It was the first plastic. It didn’t work well for billiard balls, so the quest was still on for the perfect synthetic material. John Wesley Hyatt, hoping to win a $10,000 prize from Big Billiard (a name I made up to represent the industry, so don’t call me on that) came up with celluloid. Celluloid is better known for its use in early motion picture film stock. That early film was highly flammable, and billiard balls made from celluloid had a similar, annoying feature. They exploded.

Exploding billiard balls would have been a health hazard for those who hung out in establishments where the game was played, but the explosions weren’t like grenades going off. They occasionally made a sharp pop, causing little damage even to the felt on billiard tables. The percussion sounded much like a gunshot, which reportedly caused quite a few “sports” to drop the hand of cards they’d been dealt to frantically look around the room.

Today, billiard balls are made from resin, another type of plastic. And, today, we are buried by plastic of all kinds because it shares something with the ivory it replaced. It is durable. Too durable, as it turns out.

One last note: Inventor John Wesley Hyatt never received the $10,000 prize, but he did start the Albany Billiard Ball Company. It stayed in business for 118 years.

Published on December 03, 2022 04:00

December 2, 2022

Ellen Trueblood (tap to read)

To many Idahoans, Ted Trueblood, born in Boise, was the Ernest Hemmingway of nonfiction. Trueblood taught generations how to hunt, fish, and enjoy the outdoors through his articles in Field and Stream magazine over the years and through his books about outdoor life. He was a founding member of the Idaho Wildlife Federation as well as an award-winning writer.

But this column isn’t about Ted Trueblood. His fame overshadowed the remarkable accomplishments of Ellen Trueblood, Ted’s wife.

Ellen, also born in Boise, was a writer in her own right. She reported for the Boise Capital New and the Nampa Free Press. Ellen was an accomplished hunter, angler, and photographer when she met Ted Trueblood, so the match seemed a natural. Following their 1939 marriage, the Truebloods honeymooned all summer long in the Idaho wilderness. That summer cemented her already strong love for the study of nature.

In the 1950s, Ellen was an amateur collector of plants. She began to focus on something that is often overshadowed by Idaho’s beautiful wildflowers. Ellen grew passionate about fungi. Although she took a few classes, she was mostly self-taught in mycology, the scientific study of fungi. As she became more proficient, she found mentors in the field to take her to the next level. After a few years of collecting, identifying, and sharing her knowledge she became the leading expert on fungi in southwestern Idaho, eastern Oregon, and northern Nevada, concentrating mostly in the Owyhees.

Fungi in the Owyhees are mostly found beneath sagebrush, though Ellen discovered them in desert ponds and creeks as well. Some are larger than a softball; some smaller than the head of a pin. If you think of mushrooms as brown, you’ve missed the colors that range from robin-egg blue through purple to vivid yellows and reds. Ellen Trueblood is credited with discovering more than 20 species of fungi.

Ellen was often seen with a slide carousel under her arm, off again to speak to a garden club about mushrooms. She had more than 2,700 slides. In 1975, when Boise State University added mycology to its curriculum, Ellen was the obvious choice to teach it.

In a 1962 article in the Idaho Free Press, Ellen Trueblood confessed a fear that many mushroom hunters have. “I spent a restless night the first time I served oyster mushrooms to my family—even though I was sure of my identification and was reassured by the book I had with me. There was that fear of toadstools that I couldn’t forget. I had to check in the night to see if my family was alive.”

After that sleepless night she educated herself and her family on how to identify a poisonous mushrooms. Her two sons, 5 and 7 at the time could quickly spot the tell-tale signs.

Some 6,500 of Ellen’s collections are housed at the University of Michigan Herbarium in Ann Arbor, College of Idaho in Caldwell, and Virginia Polytechnic Institute in Blacksburg. Ellen Trueblood passed away in 1994.

Note: I received a letter about Ellen from the Southern Idaho Mycological Association after this post ran the first in December of 2021. I’ve included much of it here because it adds much to Ellen’s story.

Ellen Trueblood was instrumental in the formation of the Southern Idaho Mycological Association, January, 1976.

Under Ellen's guidance SIMA (Southern Idaho Mycological Association) was established as an organization of amateur mycologists dedicated to studying the ecology of fungi and its interaction with plants and animals. Mycology, like Ornithology, is one of the few sciences left with an active role for amateurs.

The North American Mycological Association contacted Ellen Trueblood and Dr Orson K Miller Jr about establishing a mycological society affiliated with NAMA to host a national foray in the McCall area for the fall of 1976. The McCall area is a transition zone between the Blue Mountain and Rocky Mountain Biomes, and is rich in diversity of fungal species. With Ellen's guidance SIMA was formed and hosted a national mycological foray in 1976. SIMA also hosted a second national foray in September 2008.

Ellen shared her extensive knowledge of the fungi of Owyhee county freely with SIMA members, leading many short weekend forays into the Owyhee mountains.

SIMA's data base of over 2000 individual species reflects Ellen's collections and other fungi collected by SIMA in Owyhee, Ada, Boise, Elmore, Canyon, Gem, Payette, Washington, Adams, Valley, Idaho Counties of Idaho plus Malheur and Baker Counties of Oregon.

SIMA still exists today, hosting spring and fall forays in the McCall area yearly, adding to the work Ellen started years ago. SIMA has a membership of 50-plus dedicated amateur scientists studying mycology.

Genille Steiner, Robert Chehey, past presidents of SIMA. Ted Trueblood, left, holds a fish caught by his wife Ellen. Both loved the outdoors. Ted wrote for Field and Stream for many years. Ellen was an accomplished mycologist. Photo from the Ted Trueblood Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Boise State University.

Ted Trueblood, left, holds a fish caught by his wife Ellen. Both loved the outdoors. Ted wrote for Field and Stream for many years. Ellen was an accomplished mycologist. Photo from the Ted Trueblood Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Boise State University.

But this column isn’t about Ted Trueblood. His fame overshadowed the remarkable accomplishments of Ellen Trueblood, Ted’s wife.

Ellen, also born in Boise, was a writer in her own right. She reported for the Boise Capital New and the Nampa Free Press. Ellen was an accomplished hunter, angler, and photographer when she met Ted Trueblood, so the match seemed a natural. Following their 1939 marriage, the Truebloods honeymooned all summer long in the Idaho wilderness. That summer cemented her already strong love for the study of nature.

In the 1950s, Ellen was an amateur collector of plants. She began to focus on something that is often overshadowed by Idaho’s beautiful wildflowers. Ellen grew passionate about fungi. Although she took a few classes, she was mostly self-taught in mycology, the scientific study of fungi. As she became more proficient, she found mentors in the field to take her to the next level. After a few years of collecting, identifying, and sharing her knowledge she became the leading expert on fungi in southwestern Idaho, eastern Oregon, and northern Nevada, concentrating mostly in the Owyhees.

Fungi in the Owyhees are mostly found beneath sagebrush, though Ellen discovered them in desert ponds and creeks as well. Some are larger than a softball; some smaller than the head of a pin. If you think of mushrooms as brown, you’ve missed the colors that range from robin-egg blue through purple to vivid yellows and reds. Ellen Trueblood is credited with discovering more than 20 species of fungi.

Ellen was often seen with a slide carousel under her arm, off again to speak to a garden club about mushrooms. She had more than 2,700 slides. In 1975, when Boise State University added mycology to its curriculum, Ellen was the obvious choice to teach it.

In a 1962 article in the Idaho Free Press, Ellen Trueblood confessed a fear that many mushroom hunters have. “I spent a restless night the first time I served oyster mushrooms to my family—even though I was sure of my identification and was reassured by the book I had with me. There was that fear of toadstools that I couldn’t forget. I had to check in the night to see if my family was alive.”

After that sleepless night she educated herself and her family on how to identify a poisonous mushrooms. Her two sons, 5 and 7 at the time could quickly spot the tell-tale signs.

Some 6,500 of Ellen’s collections are housed at the University of Michigan Herbarium in Ann Arbor, College of Idaho in Caldwell, and Virginia Polytechnic Institute in Blacksburg. Ellen Trueblood passed away in 1994.

Note: I received a letter about Ellen from the Southern Idaho Mycological Association after this post ran the first in December of 2021. I’ve included much of it here because it adds much to Ellen’s story.

Ellen Trueblood was instrumental in the formation of the Southern Idaho Mycological Association, January, 1976.

Under Ellen's guidance SIMA (Southern Idaho Mycological Association) was established as an organization of amateur mycologists dedicated to studying the ecology of fungi and its interaction with plants and animals. Mycology, like Ornithology, is one of the few sciences left with an active role for amateurs.

The North American Mycological Association contacted Ellen Trueblood and Dr Orson K Miller Jr about establishing a mycological society affiliated with NAMA to host a national foray in the McCall area for the fall of 1976. The McCall area is a transition zone between the Blue Mountain and Rocky Mountain Biomes, and is rich in diversity of fungal species. With Ellen's guidance SIMA was formed and hosted a national mycological foray in 1976. SIMA also hosted a second national foray in September 2008.

Ellen shared her extensive knowledge of the fungi of Owyhee county freely with SIMA members, leading many short weekend forays into the Owyhee mountains.

SIMA's data base of over 2000 individual species reflects Ellen's collections and other fungi collected by SIMA in Owyhee, Ada, Boise, Elmore, Canyon, Gem, Payette, Washington, Adams, Valley, Idaho Counties of Idaho plus Malheur and Baker Counties of Oregon.

SIMA still exists today, hosting spring and fall forays in the McCall area yearly, adding to the work Ellen started years ago. SIMA has a membership of 50-plus dedicated amateur scientists studying mycology.

Genille Steiner, Robert Chehey, past presidents of SIMA.

Ted Trueblood, left, holds a fish caught by his wife Ellen. Both loved the outdoors. Ted wrote for Field and Stream for many years. Ellen was an accomplished mycologist. Photo from the Ted Trueblood Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Boise State University.

Ted Trueblood, left, holds a fish caught by his wife Ellen. Both loved the outdoors. Ted wrote for Field and Stream for many years. Ellen was an accomplished mycologist. Photo from the Ted Trueblood Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Boise State University.

Published on December 02, 2022 04:00

December 1, 2022

The First Senator Just (tap to read)

My election to the Idaho Senate in November rekindled my interest in my grandfather’s term as an Idaho State Senator. I knew a little about it but hadn’t done much research. None of the Blackfoot newspapers printed during that time have been digitized, so that makes looking into his state senate career doubly difficult. Fortunately, the Idaho Statesman from the 30s is readily available.

Bingham County’s Senator James Just served during two biennial sessions of the Idaho Legislature, the 23rd session in 1935-1936, and the 24th in 1937. The 23rd session included three shorter special sessions and the 24th had one special session. He was still a senator in 1938, but the Legislature managed to get along without a special session that year.

When Jim Just served in the Legislature, senators were elected by county. Today, all legislators are elected by district, with one senator per district and two representatives. In 1935, Bingham County’s population would have been about 20,000 people. Today, each of Idaho’s 35 districts have about 52,000 residents. District 15, which I serve, covers a portion of Boise and Meridian, with a tiny little strip in unincorporated Ada County.

My first clue about what kind of a senator Jim Just was came from John Corlett. John was the dean of Idaho political writers for many years, reporting for the Idaho Statesman. In his later years, he became friends with my mother, Iris Just Adamson, when they were both living in a Boise assisted living center.

I asked John once what he remembered about Senator James Just. His favorite memory was how grandad got his nickname—a nickname I didn’t know about until then.

“He would march up to the podium to pontificate about some bill,” Corlett said. “He’d hook his thumbs through his suspenders and bounce up and down on the balls of his feet while speaking. It didn’t take long for him to earn the nickname, ‘Jumpin’ Jimmy Just.’”

In those days—1935-1938—the Legislature was the big entertainment in town. The Idaho Statesman covered it blow-by-blow, often reporting the full debate on contentious issues in committee and on the floor of the Senate.

Senator Just was vigorous in his debate. Reporters often painted a picture of him “violently” objecting or “indignantly” springing to his feet to debate.

Today, the decorum of the Senate would shut that down right away, but back then, the rules were much looser.

The Senator was not a big fan of higher education. Just hated being bothered by lobbyists. He was a proponent of cutting agency budgets by 10 percent, and he fought hard (though unsuccessfully) to recognize and honor US Senator Fred T. Dubois with a grave marker.

When a move came forward to divide Bingham County, putting Aberdeen into Power County with American Falls, “Senator Just of Bingham took the floor with his maps and telegrams and letters, and explained how the natural flow of trade from the area went into Blackfoot,” according to the Idaho Statesman. The move to split the county failed.

Just fought to retain an exemption in Idaho’s lien laws for automobiles valued under $200 on the grounds that poor people needed their cars to get to work and town. Often automobile liens came into play because of medical debt. Senator Just remarked that “instead of taking a poor man’s automobile, the doctor should take a mechanic’s lien on the baby.”

In a side note during the 1935 session, the Idaho Statesman reported this exchange:

“Senator Just of Bingham county: ‘The senate is made up of lawyers and honest men.’

Senator Friend of Latah county: ‘I hope the senator from Bingham doesn’t draw the line too close between those two groups.’”

In a debate about how to carry out the death penalty in Idaho, the proposal was to switch from hanging to lethal gas.

“Senator Just of Bingham said he had first been against the bill, for he feared lethal gas might be used on the majority members of the legislature, but the more he studied the matter the more he was favorably impressed,” according to the Idaho Statesman.

“I can build a gallows for $4.80,” said the senator from Bingham, “so I judge it is a fair estimate that the state would have to spend $2500 for a new gallows. Therefore, this is an economy measure.”

The Church of Latter-Day Saints proposed turning over Ricks College to the State of Idaho in 1937. Senator Just was against it, as he was most higher education measures, but he took the time to pay tribute to the Mormon Church for their fine work in educating students at the school.

There are echoes today of the debates they were having back then. Senator Just pointed out what he considered a lot of waste. Each legislative bill and journal had a cover on it. Just thought they should be reused rather than tossed out with the trash. Recycling.

Just wanted radios banned in cars because they were distracting to drivers. That bill failed, but decades later, a bill was passed to outlaw texting and driving on the same grounds. Note that the texting bill was championed by Just’s great great granddaughter, Leslie Dolenar and her husband Dan. Dan received serious and permanent injuries due to a texting driver a few years ago.

That automobile safety was on Senator Just’s mind seems oddly out of character. I barely remember him, but I do remember much family talk about what a terrible driver he was. His first year in the Idaho State Senate marked the beginning of a requirement that all drivers have a license to operate a vehicle.

When the Legislature came back into session in 1937, the Idaho Statesman reported that, “Senator James Just of Bingham county is back in his familiar post on the front line of the upper house, although he protested the arrangement was against his will. Senator Just planted his paraphernalia on a rear desk, staked out a claim, as it were. Senator L.L. Burtenshow of Adam, offered advice to the contrary.

“Now, Jim,” he said, “think how tired you’ll get walking from clear back here up to the front every time you deliver an oration.”

The paper ended the piece with, “Senator Just is up front.”

Because I’m currently unable to research Blackfoot papers from the time of his service, I don’t know if Jim Just decided not to run for a second term or if he was defeated.

One clue might be a quote from the Senator in the Statesman regarding his regrets about coming to Boise and leaving his cows back home on the borders of the Blackfoot Reservoir.

“Sometimes,” confided the Bingham county solon, “my service in the legislature seems like nothing but a dream, and a bad dream at that.”

Now that voters in District 15 have given me a chance to follow in my grandfather’s footsteps, I’m eager to see just what kind of dream it is.

Idaho State Senator James Just

Idaho State Senator James Just

Published on December 01, 2022 04:00

November 30, 2022

November 29, 2022

Boxing Comes to Idaho (Tap to read)

In 1919, boxing was legalized in Idaho. The Legislature created a boxing commission (also in charge of wrestling) to oversee the sport. The law specified 20-round bouts with four-ounce gloves.

Mrs. Carrie White, one of two female representatives at the time, was enthusiastic. “I don’t want my sons to be mollycoddles,” she said. “This bill will prevent a race of mollycoddles.”

The need for the prevention of mollycoddling seemed urgent. The Idaho Statesman noted that since the bill didn’t have an emergency clause, it wouldn’t take effect for 60 days. They predicted that when the waiting time was up, promoters would be “busy as the knob on the single door of the one saloon in a mining town on payday.”

Mrs. Carrie White, one of two female representatives at the time, was enthusiastic. “I don’t want my sons to be mollycoddles,” she said. “This bill will prevent a race of mollycoddles.”

The need for the prevention of mollycoddling seemed urgent. The Idaho Statesman noted that since the bill didn’t have an emergency clause, it wouldn’t take effect for 60 days. They predicted that when the waiting time was up, promoters would be “busy as the knob on the single door of the one saloon in a mining town on payday.”

Published on November 29, 2022 04:00

November 28, 2022

Mishapen Blaine County (Tap to read)

Have you ever wondered why Idaho’s Blaine County is shaped so weirdly? Each county shape in the state is unique, but Blaine County calls attention to itself by sending a tentacle far south of its bulk, like an amoeba reaching out to snatch a snack. It reminds one of the shapes of those tortuous voting districts some states have where politicians string together partisans from one party or the other in order to win elections.

Political intrigue partly explains the weird shape of Blaine County. It is something of a leftover county, with its shape changing four times between March 5, 1895, and February 6, 1917.

There was much drama over the shape of counties in February 1895 when the question of Blaine County was first debated in the Idaho Legislature. Rumors abounded that Nampa wanted to be a part of Ada County and that Boise County was about to be split up with part of it to be named Butte County. The rumors were so frequent and contradictory that one legislative wag ginned up a phony bill to create one giant county called Grant County. It would have consolidated the 21 counties that then existed into a single county. Grant County’s county seat was to be the city of Shoshone, which was one of the towns then embroiled over a debate regarding what was to become of Alturas and Logan counties. The bill writer, tongue in cheek, thought that making one county, the boundaries of which would match the boundaries of the state, would solve all the boundary problems.

The proposal to create a county called Blaine, named for 1854 Republican presidential nominee James G. Blaine, was contentious because of the financial pickle of Alturas County, which was in a state of bankruptcy. Citizens of Logan County, which was to be combined with Alturas to form Blaine County, objected to taking on the debt of Alturas.

Poor Alturas. Its last gasp would come on March 5, 1895 when the Blaine county bill prevailed. It was a bloated county upon its creation by the Idaho Territorial Legislature in 1864. Taking up more map space than the states of Maryland, New Jersey, and Delaware combined, it was doomed to be whittled down to nothing.

The new Blaine County didn’t retain its original shape for long, either. The Legislature carved Lincoln County from it just a couple of weeks later, on March 18. It lost a little more weight in January of 1913 when Power County was extracted from Blaine. The dieting county slimmed down to its present shape in February 1917 when Butte and Camas counties were trimmed away.

Through all that reduction in size, Blaine County managed to keep that weird little strip reaching down to Lake Walcott because it improved the county’s tax base. That narrow reach of land encompassed a bit of railroad property, taxes for which helped Blaine County keep its books balanced.

Political intrigue partly explains the weird shape of Blaine County. It is something of a leftover county, with its shape changing four times between March 5, 1895, and February 6, 1917.

There was much drama over the shape of counties in February 1895 when the question of Blaine County was first debated in the Idaho Legislature. Rumors abounded that Nampa wanted to be a part of Ada County and that Boise County was about to be split up with part of it to be named Butte County. The rumors were so frequent and contradictory that one legislative wag ginned up a phony bill to create one giant county called Grant County. It would have consolidated the 21 counties that then existed into a single county. Grant County’s county seat was to be the city of Shoshone, which was one of the towns then embroiled over a debate regarding what was to become of Alturas and Logan counties. The bill writer, tongue in cheek, thought that making one county, the boundaries of which would match the boundaries of the state, would solve all the boundary problems.

The proposal to create a county called Blaine, named for 1854 Republican presidential nominee James G. Blaine, was contentious because of the financial pickle of Alturas County, which was in a state of bankruptcy. Citizens of Logan County, which was to be combined with Alturas to form Blaine County, objected to taking on the debt of Alturas.

Poor Alturas. Its last gasp would come on March 5, 1895 when the Blaine county bill prevailed. It was a bloated county upon its creation by the Idaho Territorial Legislature in 1864. Taking up more map space than the states of Maryland, New Jersey, and Delaware combined, it was doomed to be whittled down to nothing.

The new Blaine County didn’t retain its original shape for long, either. The Legislature carved Lincoln County from it just a couple of weeks later, on March 18. It lost a little more weight in January of 1913 when Power County was extracted from Blaine. The dieting county slimmed down to its present shape in February 1917 when Butte and Camas counties were trimmed away.

Through all that reduction in size, Blaine County managed to keep that weird little strip reaching down to Lake Walcott because it improved the county’s tax base. That narrow reach of land encompassed a bit of railroad property, taxes for which helped Blaine County keep its books balanced.

Published on November 28, 2022 04:00