Rick Just's Blog, page 72

January 6, 2023

The CCC-ID (tap to read)

The Civilian Conservation Corps was a storied program of FDR’s New Deal. Idaho embraced the program perhaps more than any other state, getting the largest number of CCC camps per population in the country. The total number of camps in Idaho, 270, was second only to California.

Less well-known was the impact of a parallel program called CCC-ID. In this case, the ID didn’t stand for Idaho but for Indian.

Records show that 80,000 to 85,000 men served in the CCC-ID. One remarkable feature of the program was that it was run mainly by the Tribes. They selected the men from their reservations who would participate. Those men learned animal husbandry, gardening, road building, conservation work, and academic subjects. Most of the work they did was on their home reservations.

Nationwide the CCC-ID men laid out almost 9,800 miles of truck trails, controlled pests on 1,351,870 acres, eradicated weeds on 263,129 acres, and built 1,792 dams and reservoirs. Those efforts were similar to the CCCs, but the Indian branch also focused on teaching native skills and arts.

The men receive $30 a month for working 20 days. Some were paid from $1 to $2 a day for the use of their teams of horses. If they took advantage of all the pay opportunities of the program, they could make up to $42 a month. The regular CCC men made at most $30.

One of the most important outcomes of the CCC-ID was that the program showed that Native Americans could succeed under their own tribal management.

Both the CCC and CCC-ID were disbanded in the early 1940s as the nation turned its attention to WWII.

A Fort Hall work crew of the CCC-ID working on a road.

A Fort Hall work crew of the CCC-ID working on a road.  Men from the Fort Hall CCC-ID seeding a hillside.

Men from the Fort Hall CCC-ID seeding a hillside.  Group picture, 20 men in front of tents, Fort Hall Reservation. All photos are from the Civilian Conservation Corps in Idaho Collection, Digital Initiatives, University of Idaho Library. Digital reproduction rights provided by Mary Washakie.

Group picture, 20 men in front of tents, Fort Hall Reservation. All photos are from the Civilian Conservation Corps in Idaho Collection, Digital Initiatives, University of Idaho Library. Digital reproduction rights provided by Mary Washakie.

Less well-known was the impact of a parallel program called CCC-ID. In this case, the ID didn’t stand for Idaho but for Indian.

Records show that 80,000 to 85,000 men served in the CCC-ID. One remarkable feature of the program was that it was run mainly by the Tribes. They selected the men from their reservations who would participate. Those men learned animal husbandry, gardening, road building, conservation work, and academic subjects. Most of the work they did was on their home reservations.

Nationwide the CCC-ID men laid out almost 9,800 miles of truck trails, controlled pests on 1,351,870 acres, eradicated weeds on 263,129 acres, and built 1,792 dams and reservoirs. Those efforts were similar to the CCCs, but the Indian branch also focused on teaching native skills and arts.

The men receive $30 a month for working 20 days. Some were paid from $1 to $2 a day for the use of their teams of horses. If they took advantage of all the pay opportunities of the program, they could make up to $42 a month. The regular CCC men made at most $30.

One of the most important outcomes of the CCC-ID was that the program showed that Native Americans could succeed under their own tribal management.

Both the CCC and CCC-ID were disbanded in the early 1940s as the nation turned its attention to WWII.

A Fort Hall work crew of the CCC-ID working on a road.

A Fort Hall work crew of the CCC-ID working on a road.  Men from the Fort Hall CCC-ID seeding a hillside.

Men from the Fort Hall CCC-ID seeding a hillside.  Group picture, 20 men in front of tents, Fort Hall Reservation. All photos are from the Civilian Conservation Corps in Idaho Collection, Digital Initiatives, University of Idaho Library. Digital reproduction rights provided by Mary Washakie.

Group picture, 20 men in front of tents, Fort Hall Reservation. All photos are from the Civilian Conservation Corps in Idaho Collection, Digital Initiatives, University of Idaho Library. Digital reproduction rights provided by Mary Washakie.

Published on January 06, 2023 04:00

January 5, 2023

Then and Now, Idaho Creatures (tap to read)

This is another of our occasional Now and Then features.

THEN:

In 1868 Joseph Rich owned a spa on Bear Lake in the southeast corner of Idaho. He wrote to the Deseret News in Salt Lake City and told a story he said he'd heard from local Indians. According to their legends, a serpentine monster prowled Bear Lake. It had short, stubby legs it sometimes used to scurry onto shore and snatch away maidens in its terrible jaws.

After the letter appeared, people all over the valley began seeing the monster. One said it was 40 feet long and swam faster than a horse could run. Another claimed it was 90 feet long and swam faster than a locomotive.

This astonishing creature had everyone in an uproar.

The Salt Lake newspaper carried many accounts of monster sightings, and efforts to trap the beast.

Then, Joseph Rich wrote another letter to the paper expressing his sorrow that some didn't believe in the monster. He said, "they might come up here someday, and through their unbelief, be thrown off their guard and gobbled up by the Water Devil." There was a tone to that letter though, that not everyone caught. Mr. Rich was writing tongue in cheek and having a wonderful time with the tale he had invented to attract customers to his resort.

Many more people claimed to have spotted the Bear Lake Monster over the years, and they started seeing monsters in other nearby lakes... which must have been an endless source of amusement for the monster's father, Joseph Rich.

NOW:

Other entrepreneurs are using a mythical creature to attract tourists today. Francis Conklin and Dennis Sullivan are husband and wife artists who live in Cottonwood. They had great success in 1995 when their chainsaw carvings of dogs were featured on QVC. They had to work like—sorry—dogs to keep up with the orders.

Their studio and shop are near the highway as it passes by Cottonwood. To draw people in, they carved up the “world’s biggest beagle” and parked it out front. That worked so well that they had another big idea. How about a dog big enough that you could sleep in it?

Dennis and Francis built the 30-foot high, two-bedroom beagle and started booking reservations at Dog Bark Park Inn. It drew tourists off the highway, all right, but the big dog’s fame grew in other ways. The beagle, which also has a balcony, has been featured in dozens of magazines, blogs, videos, etc. To name a few, O Magazine, the Ellen DeGeneres Show, the Washington Post, LA Times, CNN, and on and on.

They have at least as much fun with their invention as Joseph Rich did with his 127 years earlier.

No, this isn't the Bear Lake Monster.

No, this isn't the Bear Lake Monster.

THEN:

In 1868 Joseph Rich owned a spa on Bear Lake in the southeast corner of Idaho. He wrote to the Deseret News in Salt Lake City and told a story he said he'd heard from local Indians. According to their legends, a serpentine monster prowled Bear Lake. It had short, stubby legs it sometimes used to scurry onto shore and snatch away maidens in its terrible jaws.

After the letter appeared, people all over the valley began seeing the monster. One said it was 40 feet long and swam faster than a horse could run. Another claimed it was 90 feet long and swam faster than a locomotive.

This astonishing creature had everyone in an uproar.

The Salt Lake newspaper carried many accounts of monster sightings, and efforts to trap the beast.

Then, Joseph Rich wrote another letter to the paper expressing his sorrow that some didn't believe in the monster. He said, "they might come up here someday, and through their unbelief, be thrown off their guard and gobbled up by the Water Devil." There was a tone to that letter though, that not everyone caught. Mr. Rich was writing tongue in cheek and having a wonderful time with the tale he had invented to attract customers to his resort.

Many more people claimed to have spotted the Bear Lake Monster over the years, and they started seeing monsters in other nearby lakes... which must have been an endless source of amusement for the monster's father, Joseph Rich.

NOW:

Other entrepreneurs are using a mythical creature to attract tourists today. Francis Conklin and Dennis Sullivan are husband and wife artists who live in Cottonwood. They had great success in 1995 when their chainsaw carvings of dogs were featured on QVC. They had to work like—sorry—dogs to keep up with the orders.

Their studio and shop are near the highway as it passes by Cottonwood. To draw people in, they carved up the “world’s biggest beagle” and parked it out front. That worked so well that they had another big idea. How about a dog big enough that you could sleep in it?

Dennis and Francis built the 30-foot high, two-bedroom beagle and started booking reservations at Dog Bark Park Inn. It drew tourists off the highway, all right, but the big dog’s fame grew in other ways. The beagle, which also has a balcony, has been featured in dozens of magazines, blogs, videos, etc. To name a few, O Magazine, the Ellen DeGeneres Show, the Washington Post, LA Times, CNN, and on and on.

They have at least as much fun with their invention as Joseph Rich did with his 127 years earlier.

No, this isn't the Bear Lake Monster.

No, this isn't the Bear Lake Monster.

Published on January 05, 2023 04:00

January 4, 2023

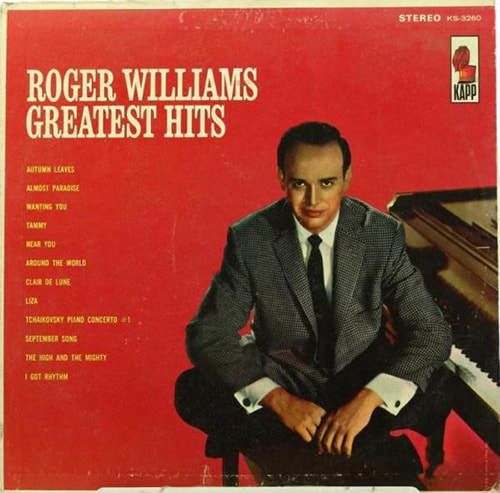

Roger Williams (tap to read)

Louis Jacob Weertz came to Idaho in 1943. He was one of almost 300,000 men who trained for World War II at Farragut Naval Training Station, where Farragut State Park is now. He played piano well even then, but at Farragut, he was probably best known for his boxing. Weertz was the welterweight champion boxer on the base.

Weertz was one of a handful of Farragut recruits who received part of their training at what was then the University of Idaho Southern Branch in Pocatello. He must have liked the city, because he came back after the war to attend college. He received a BA in music from ISU, then went on to get a Master's from Drake University. He studied further at Julliard in New York.

For whatever reason, Weertz decided to change his name while living in Pocatello. He allegedly pulled out a telephone book and ran his finger down the columns until he found one he liked. That name was Roger Williams.

There was only one Roger Williams in the phonebook at that time, according to the Roger Williams I knew. My friend, Roger, was a long-time Fish and Game employee and gained some measure of fame, along with Syd Tate, by charting out Idaho’s Centennial Trail.

The faux or, perhaps better-said, newly named Roger Williams gained quite a bit of fame in his time.

First, he won "Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts" program, with a lively piano rendition of I Got Rhythm. But it wasn't until 1954, that a record company executive heard him playing piano in a Manhattan cocktail lounge, and signed him to a contract. His first, and still most famous, hit record was Autumn Leaves. By 1968 he had recorded 52 albums, and sold nearly 15 million records. At 43, he became the best-selling instrumentalist of all time.

Roger Williams, name borrower, Farragut Naval Training Station recruit, ISU graduate, and world-renowned pianist and composer passed away in 2011.

Weertz was one of a handful of Farragut recruits who received part of their training at what was then the University of Idaho Southern Branch in Pocatello. He must have liked the city, because he came back after the war to attend college. He received a BA in music from ISU, then went on to get a Master's from Drake University. He studied further at Julliard in New York.

For whatever reason, Weertz decided to change his name while living in Pocatello. He allegedly pulled out a telephone book and ran his finger down the columns until he found one he liked. That name was Roger Williams.

There was only one Roger Williams in the phonebook at that time, according to the Roger Williams I knew. My friend, Roger, was a long-time Fish and Game employee and gained some measure of fame, along with Syd Tate, by charting out Idaho’s Centennial Trail.

The faux or, perhaps better-said, newly named Roger Williams gained quite a bit of fame in his time.

First, he won "Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts" program, with a lively piano rendition of I Got Rhythm. But it wasn't until 1954, that a record company executive heard him playing piano in a Manhattan cocktail lounge, and signed him to a contract. His first, and still most famous, hit record was Autumn Leaves. By 1968 he had recorded 52 albums, and sold nearly 15 million records. At 43, he became the best-selling instrumentalist of all time.

Roger Williams, name borrower, Farragut Naval Training Station recruit, ISU graduate, and world-renowned pianist and composer passed away in 2011.

Published on January 04, 2023 04:00

January 3, 2023

Counting State Parks (tap to read)

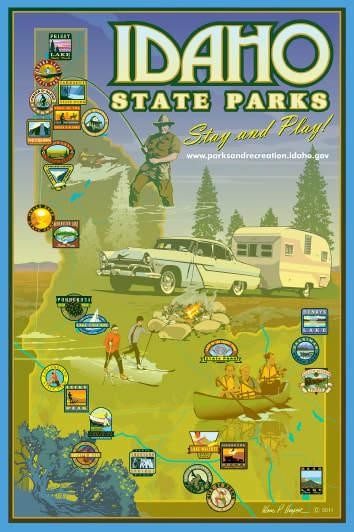

One of the most common questions I get is, how many state parks are there in Idaho? Right now, 30 with an asterisk.

Idaho has always had a hard time defining the term state park. For decades one meaning was something like: any land owned by the state of Idaho that invited citizens to use it. That included rest areas and roadside stops that happened to have a picnic table. As a result, state parks were managed at various times by the Idaho Department of Transportation, Public Works, and the Idaho Department of Lands. It wasn’t until 1965 that a dedicated state parks agency was formed.

Today’s “30” state parks include at least one you’ve never heard of and is difficult to visit and one that isn’t actually managed as a state park anymore.

Mowry State Park, on Lake Coeur d’Alene, became a state park in 1972 when the Mowry family made a partial donation of the property to the state. It’s the one you’ve probably never heard of. The property is on two small peninsulas with a beautiful beach between the two. The problem is that the state doesn’t own the beach. It hoped to acquire it but was unsuccessful. That left one peninsula that is too high about the water and too small to be of much use, and another peninsula that can be reached only by boat. That one, called Gasser Point, is managed as a boat-in picnic site by Kootenai County Parks and Waterways.

Veterans Memorial State Park opened in 1982. The Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation (IDPR) turned management of the site over to Boise Parks and Recreation in 1997. It’s still listed as a state park in statute, and is still owned by the State of Idaho, but is rarely mentioned by the agency.

Another thing that makes counting state parks confusing is local usage. Many people call Malad Gorge, Billingsley Creek, Box Canyon, Ritter Island, and Niagara Springs state parks. IDPR calls them “units” of Thousand Springs State Park.

Even this nifty IDPR poster created by Boise artist Ward Hooper shows only 27 state parks, which is off from the “official” count of 30 in statute. Why? Well, they didn’t bother creating a logo for Mowry or Veterans because see above. And—I’m just speculating here—they didn’t order a logo for Glade Creek State Park because of the nature of the place. Glade Creek, on Lolo Pass, was where Lewis and Clark first made camp in what would become Idaho. IDPR manages the site as a natural area and doesn’t encourage use other than brief visits to the interpretive overlook. So, you do the math!

Idaho has always had a hard time defining the term state park. For decades one meaning was something like: any land owned by the state of Idaho that invited citizens to use it. That included rest areas and roadside stops that happened to have a picnic table. As a result, state parks were managed at various times by the Idaho Department of Transportation, Public Works, and the Idaho Department of Lands. It wasn’t until 1965 that a dedicated state parks agency was formed.

Today’s “30” state parks include at least one you’ve never heard of and is difficult to visit and one that isn’t actually managed as a state park anymore.

Mowry State Park, on Lake Coeur d’Alene, became a state park in 1972 when the Mowry family made a partial donation of the property to the state. It’s the one you’ve probably never heard of. The property is on two small peninsulas with a beautiful beach between the two. The problem is that the state doesn’t own the beach. It hoped to acquire it but was unsuccessful. That left one peninsula that is too high about the water and too small to be of much use, and another peninsula that can be reached only by boat. That one, called Gasser Point, is managed as a boat-in picnic site by Kootenai County Parks and Waterways.

Veterans Memorial State Park opened in 1982. The Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation (IDPR) turned management of the site over to Boise Parks and Recreation in 1997. It’s still listed as a state park in statute, and is still owned by the State of Idaho, but is rarely mentioned by the agency.

Another thing that makes counting state parks confusing is local usage. Many people call Malad Gorge, Billingsley Creek, Box Canyon, Ritter Island, and Niagara Springs state parks. IDPR calls them “units” of Thousand Springs State Park.

Even this nifty IDPR poster created by Boise artist Ward Hooper shows only 27 state parks, which is off from the “official” count of 30 in statute. Why? Well, they didn’t bother creating a logo for Mowry or Veterans because see above. And—I’m just speculating here—they didn’t order a logo for Glade Creek State Park because of the nature of the place. Glade Creek, on Lolo Pass, was where Lewis and Clark first made camp in what would become Idaho. IDPR manages the site as a natural area and doesn’t encourage use other than brief visits to the interpretive overlook. So, you do the math!

Published on January 03, 2023 04:00

January 2, 2023

The Caxton Fire (tap to read)

In 1937, Caxton Printers was ready to celebrate its 30th anniversary. Starting as a printing and office services company, the printer had also begun publishing books in 1925 as Caxton Press. In January of 1937 Caxton released Idaho: A Guide in Word and Pictures, by Vardis Fisher, the first book from the Works Project Administration. It looked like a banner year for the company.

Then, on the morning of St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1937, someone in the building noticed smoke. Just after 9 am, word ran through the offices that there was a fire in the west stockroom where countless books and printing supplies were stored. Employees scramble to put the fire out with fire extinguishers, but the blaze had a good hold. Flames roared in a flash up the wall and into the second-floor offices.

There wasn’t even time to close the office safes before employees were forced to escaped through fire and smoke down the back stairs.

The head of the offset printing department on the east side of the building, G.H. Spurgeon, grabbed three expensive camera lenses before jumping through a window. Other employees scrambled to get equipment out, including two small lithographic presses.

A stroke of luck protected many of the company’s records. One of the office safes, door open, crashed through the weakened floor of the building. The door slammed shut when it landed, saving the contents.

The fire did not reach the basement but, the water firefighters used to quench the blaze cascaded into the $50,000 worth of school supplies stored there, ruining them.

The second edition of Fisher’s Idaho Guide was under production at the time of the fire. About 15 minutes before the alarm sounded a truckload of pictures left the lithographic department and went to the bindery room where they were destroyed.

Annuals for Northwest Nazarene college, Gooding College, the University of Idaho southern branch (now ISU), the College of Idaho, and Albion State Normal School, along with those of seven area high schools were under production at the time. The fire got them all.

Many books under production were also destroyed, but the owners and staff of the publishing company showed a remarkable resilience. As the sun was setting on the day of the fire—the largest in Caldwell history at that time—crews were working on various projects at other nearby printing companies. A meeting of the board of directors took place that same night to select equipment to be shipped in for a new plant. Orders for the equipment went out the next day.

Caxton Printers and Publishing erected a much larger building and kept one of the most famous publishing houses in the West alive. It still thrives in Caldwell today.

Why did J.H. Gipson choose to call his printing company Caxton? A man by the name of William Caxton produced the first book printed in English. That was in 1473 in Bruges, Belgium. In 1476 he was the first to bring a press to England, his home country. The first book he printed was a version of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. A.E. Gipson borrowed not only the name, but William Caxton’s printers mark (below) which is used to this day on Caxton’s books to honor that early printer.

For more on the history of Caxton Press, watch Idaho Experience on Idaho Public Television. The Caxton Press story previewed December 5, 2021. Here’s a link to the story.

Then, on the morning of St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1937, someone in the building noticed smoke. Just after 9 am, word ran through the offices that there was a fire in the west stockroom where countless books and printing supplies were stored. Employees scramble to put the fire out with fire extinguishers, but the blaze had a good hold. Flames roared in a flash up the wall and into the second-floor offices.

There wasn’t even time to close the office safes before employees were forced to escaped through fire and smoke down the back stairs.

The head of the offset printing department on the east side of the building, G.H. Spurgeon, grabbed three expensive camera lenses before jumping through a window. Other employees scrambled to get equipment out, including two small lithographic presses.

A stroke of luck protected many of the company’s records. One of the office safes, door open, crashed through the weakened floor of the building. The door slammed shut when it landed, saving the contents.

The fire did not reach the basement but, the water firefighters used to quench the blaze cascaded into the $50,000 worth of school supplies stored there, ruining them.

The second edition of Fisher’s Idaho Guide was under production at the time of the fire. About 15 minutes before the alarm sounded a truckload of pictures left the lithographic department and went to the bindery room where they were destroyed.

Annuals for Northwest Nazarene college, Gooding College, the University of Idaho southern branch (now ISU), the College of Idaho, and Albion State Normal School, along with those of seven area high schools were under production at the time. The fire got them all.

Many books under production were also destroyed, but the owners and staff of the publishing company showed a remarkable resilience. As the sun was setting on the day of the fire—the largest in Caldwell history at that time—crews were working on various projects at other nearby printing companies. A meeting of the board of directors took place that same night to select equipment to be shipped in for a new plant. Orders for the equipment went out the next day.

Caxton Printers and Publishing erected a much larger building and kept one of the most famous publishing houses in the West alive. It still thrives in Caldwell today.

Why did J.H. Gipson choose to call his printing company Caxton? A man by the name of William Caxton produced the first book printed in English. That was in 1473 in Bruges, Belgium. In 1476 he was the first to bring a press to England, his home country. The first book he printed was a version of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. A.E. Gipson borrowed not only the name, but William Caxton’s printers mark (below) which is used to this day on Caxton’s books to honor that early printer.

For more on the history of Caxton Press, watch Idaho Experience on Idaho Public Television. The Caxton Press story previewed December 5, 2021. Here’s a link to the story.

Published on January 02, 2023 04:00

January 1, 2023

Building Bogus Basin (tap to read)

Downhill skiing has been around for a while, but maybe not as long as you think. It started to emerge as a recreational pursuit in the 19th century and didn’t become an Olympic sport, in the form of slalom racing, until 1936. That same year, in December, the Sun Valley Ski Resort opened in Idaho, becoming the first destination winter resort in the U.S.

Young, fit Boiseans, enthralled with Sun Valley, were eager to bring this new sport of downhill skiing closer to home. They formed the Boise Ski Club at a time when all skis were made of hickory and ski poles were made from bamboo.

The most convenient places to ski were at the American Legion Golf Course at the end of 8th Street, and on the summit of Horseshoe Bend Hill. Both meant a fair amount of trudging. Even so, the members of the ski club were hooked. They began looking for a better place to ski close to town.

Alf Engen of Sun Valley was an early competitive skier and ski-jumper commissioned by the Forest Service to look for a site on the Boise National Forest that might work. Joining him in the search were Boise Ski Club President John Hearne and Boise Forest Landscape Architect Yale Moeller. They did some trudging, some looking, and a lot of skiing from Horseshoe Bend Hill to Pilot’s Peak near Idaho City—some 85 miles across the ridges—before settling on Shafer Butte and nearby Deer Point, a site that seemed to offer dependable snow.

Of course, finding the site and getting people up the hill to enjoy it were two different things. The Boise Jaycees backed the effort to develop a ski area. They applied for and received a Works Project Administration (WPA) grant to build a road to the site and provide some basic utilities along with picnic and camping facilities. The road project began in 1938 and would end up costing $307,000.

Bogus Basin Road is today one of the most prominent facilities in southwestern Idaho that owes its existence to the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). It took 120 men to accomplish the road work, while another 75 CCCs built facilities on the mountain.

The opening of the ski area was delayed a year because of World War II. Bogus Basin opened on December 20, 1942, with 200 skiers coming out to test the slopes, 50 of them soldiers from Gowen Field. Many carpooled up the road because of gas rationing. Skiing that day was delayed a bit because someone had stolen the cable from the lift, and it had to be replaced.

Early in the road’s history, the popularity of the ski area caused a major change to something we take for granted today. The City of Boise had selected a site not far from Bogus Basin road as the location of a landfill. Skiers put the kibosh to that, and the landfill was built where it is today, near Seamans Gulch.

Bogus Basin today is better than ever with snow-making capabilities, jazzy lifts, and a panoply of summer activities from a climbing wall to the Glade Runner mountain slider. During the 2018-19 season, they hosted 377,000 visitors, quite a jump from that first 200-visitor day. There is much more fascinating history than I can plug into a short blog post. I recommend Building Bogus Basin by Eve Chandler if you’d like to find out more. Skiers lined up for the Bogus Basin rope tow in 1950. The first rope tow on the mountain was powered by a Model A engine. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-164-116e. Skiers lined up for the Bogus Basin rope tow in 1950. The first rope tow on the mountain was powered by a Model A engine. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-164-116e.

Skiers lined up for the Bogus Basin rope tow in 1950. The first rope tow on the mountain was powered by a Model A engine. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-164-116e.

Young, fit Boiseans, enthralled with Sun Valley, were eager to bring this new sport of downhill skiing closer to home. They formed the Boise Ski Club at a time when all skis were made of hickory and ski poles were made from bamboo.

The most convenient places to ski were at the American Legion Golf Course at the end of 8th Street, and on the summit of Horseshoe Bend Hill. Both meant a fair amount of trudging. Even so, the members of the ski club were hooked. They began looking for a better place to ski close to town.

Alf Engen of Sun Valley was an early competitive skier and ski-jumper commissioned by the Forest Service to look for a site on the Boise National Forest that might work. Joining him in the search were Boise Ski Club President John Hearne and Boise Forest Landscape Architect Yale Moeller. They did some trudging, some looking, and a lot of skiing from Horseshoe Bend Hill to Pilot’s Peak near Idaho City—some 85 miles across the ridges—before settling on Shafer Butte and nearby Deer Point, a site that seemed to offer dependable snow.

Of course, finding the site and getting people up the hill to enjoy it were two different things. The Boise Jaycees backed the effort to develop a ski area. They applied for and received a Works Project Administration (WPA) grant to build a road to the site and provide some basic utilities along with picnic and camping facilities. The road project began in 1938 and would end up costing $307,000.

Bogus Basin Road is today one of the most prominent facilities in southwestern Idaho that owes its existence to the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). It took 120 men to accomplish the road work, while another 75 CCCs built facilities on the mountain.

The opening of the ski area was delayed a year because of World War II. Bogus Basin opened on December 20, 1942, with 200 skiers coming out to test the slopes, 50 of them soldiers from Gowen Field. Many carpooled up the road because of gas rationing. Skiing that day was delayed a bit because someone had stolen the cable from the lift, and it had to be replaced.

Early in the road’s history, the popularity of the ski area caused a major change to something we take for granted today. The City of Boise had selected a site not far from Bogus Basin road as the location of a landfill. Skiers put the kibosh to that, and the landfill was built where it is today, near Seamans Gulch.

Bogus Basin today is better than ever with snow-making capabilities, jazzy lifts, and a panoply of summer activities from a climbing wall to the Glade Runner mountain slider. During the 2018-19 season, they hosted 377,000 visitors, quite a jump from that first 200-visitor day. There is much more fascinating history than I can plug into a short blog post. I recommend Building Bogus Basin by Eve Chandler if you’d like to find out more. Skiers lined up for the Bogus Basin rope tow in 1950. The first rope tow on the mountain was powered by a Model A engine. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-164-116e.

Skiers lined up for the Bogus Basin rope tow in 1950. The first rope tow on the mountain was powered by a Model A engine. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-164-116e.

Skiers lined up for the Bogus Basin rope tow in 1950. The first rope tow on the mountain was powered by a Model A engine. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-164-116e.

Published on January 01, 2023 04:00

December 31, 2022

December 30, 2022

Tom and Nel (tap to read)

This is a photo of Tom Trusky, who was a professor at BSU who happened to be a good friend of mine. Tom loved to find little treasures that were lost to history. He discovered that there was once a movie studio on the shores of Priest Lake run by a woman named Nell Shipman. Little was known about her, and the films she produced there had mostly been lost to time. Tom decided he’d find them. He had no idea how difficult that would be. He searched archives in Canada, the United Kingdom, and in Russia. He began finding them, one after another until he found every single one of her films.

On top of that, he found her unpublished autobiography and convinced BSU to publish it under the title The Silent Screen and My Talking Heart.

Tom Trusky wrote the following about Nell in 2008: “In the summer of 1922, Nell Shipman Productions moved from Spokane, Washington to its final residence, Priest Lake, in the Panhandle of North Idaho. There, the company would complete shooting of what historians and silent film fans term Shipman’s magnum opus, The Grub-Stake (1922), and four noteworthy two-reel films in a series titled The Little Dramas of the Big Places (1924). Although Shipman and her crew could not have known it, this was sundown for the democratic, “Indie,” one-girl-do-it-all days of cinema. Dawn of the next day, the studio system and male movie moguls would define for decades what Hollywood meant, prior to the advent of television, Gloria Steinem, Sundance, satellite feeds, and on-line downloads.”

Nell Shipman was the screenwriter, director, star, and stunt woman in her movies. They featured strong women more likely to save men from danger than the other way around. Her pioneering included what by today’s standards would be a PG-rated nude scene of her showering beneath a waterfall. The movie was hyped with the slogan, “Is the nude, rude?” Shipman Point in Priest Lake State Park is named for this early film pioneer.

Because of the scholarship of Professor Trusky, who passed away in 2009, Boise State University is the home to a digital collection of Shipman photographs and other memorabilia. Many of her films are available online. Revival of interest in Shipman resulted in an award-winning 2015 documentary called Girl From God’s Country,” by Boise filmmaker Karen Day.

On top of that, he found her unpublished autobiography and convinced BSU to publish it under the title The Silent Screen and My Talking Heart.

Tom Trusky wrote the following about Nell in 2008: “In the summer of 1922, Nell Shipman Productions moved from Spokane, Washington to its final residence, Priest Lake, in the Panhandle of North Idaho. There, the company would complete shooting of what historians and silent film fans term Shipman’s magnum opus, The Grub-Stake (1922), and four noteworthy two-reel films in a series titled The Little Dramas of the Big Places (1924). Although Shipman and her crew could not have known it, this was sundown for the democratic, “Indie,” one-girl-do-it-all days of cinema. Dawn of the next day, the studio system and male movie moguls would define for decades what Hollywood meant, prior to the advent of television, Gloria Steinem, Sundance, satellite feeds, and on-line downloads.”

Nell Shipman was the screenwriter, director, star, and stunt woman in her movies. They featured strong women more likely to save men from danger than the other way around. Her pioneering included what by today’s standards would be a PG-rated nude scene of her showering beneath a waterfall. The movie was hyped with the slogan, “Is the nude, rude?” Shipman Point in Priest Lake State Park is named for this early film pioneer.

Because of the scholarship of Professor Trusky, who passed away in 2009, Boise State University is the home to a digital collection of Shipman photographs and other memorabilia. Many of her films are available online. Revival of interest in Shipman resulted in an award-winning 2015 documentary called Girl From God’s Country,” by Boise filmmaker Karen Day.

Published on December 30, 2022 04:00

December 29, 2022

Tarzan's Idaho Connection (tap to read)

Tarzan of the Apes. The setting for those stories was deepest, darkest Africa, but the author spent some of his early days in deepest, darkest... Pocatello.

Edgar Rice Burroughs came to the state in the mid 1890s. His brothers worked on a ranch their father had purchased near Yale, Idaho (which the brothers, Yale graduates, had convinced the postal service to name) and he got a job there, too, as a cowhand. But he didn’t stick with any job very long. Burroughs worked for a local dredge company for a while, then found himself unemployed.

With the help of his brother Harry, Edgar Rice Burroughs purchased a stationery and cigar store in Pocatello at 233 West Center Street in 1898. He also established a Pocatello delivery service, sometimes delivering newspapers himself from the back of a black horse named Crow. It turned out that Burroughs was not as successful at selling books as he would later become at writing them. He sold the failing Pocatello store a year after he bought it.

He tried ranching again. He worked for a dredge company again, this time in Minidoka. He lived in the Stanley Basin for a while, and even ran for office in 1904 in Parma, where he was elected alderman.

Eventually Burroughs moved out of Idaho. His continued bouts of unemployment gave him time to try his hand at writing. In 1914 he published a book called "Tarzan of the Apes," and its character became an international fictional hero. Edgar Rice Burroughs, a writer shaped in part by his many years in Idaho.

For much more on his Idaho connection, just Google Edgar Rice Burroughs Idaho.

Edgar Rice Burroughs came to the state in the mid 1890s. His brothers worked on a ranch their father had purchased near Yale, Idaho (which the brothers, Yale graduates, had convinced the postal service to name) and he got a job there, too, as a cowhand. But he didn’t stick with any job very long. Burroughs worked for a local dredge company for a while, then found himself unemployed.

With the help of his brother Harry, Edgar Rice Burroughs purchased a stationery and cigar store in Pocatello at 233 West Center Street in 1898. He also established a Pocatello delivery service, sometimes delivering newspapers himself from the back of a black horse named Crow. It turned out that Burroughs was not as successful at selling books as he would later become at writing them. He sold the failing Pocatello store a year after he bought it.

He tried ranching again. He worked for a dredge company again, this time in Minidoka. He lived in the Stanley Basin for a while, and even ran for office in 1904 in Parma, where he was elected alderman.

Eventually Burroughs moved out of Idaho. His continued bouts of unemployment gave him time to try his hand at writing. In 1914 he published a book called "Tarzan of the Apes," and its character became an international fictional hero. Edgar Rice Burroughs, a writer shaped in part by his many years in Idaho.

For much more on his Idaho connection, just Google Edgar Rice Burroughs Idaho.

Published on December 29, 2022 04:00

December 28, 2022

Peg Leg Annie (tap to read)

Annie McIntyre came to the gold camp of Rocky Bar on July 4th, 1864. And she came in a most unusual way.

Annie was just four years old, and she arrived in a backpack carried by her father.

It was when she was 38 years old and had five children of her own that Annie--then Annie Morrow--experienced the tragedy that made her an Idaho legend.

In the late spring of 1898 she and a lady friend called Dutch Em decided to make a snowshoe trip from Atlanta over the mountains to Rocky Bar. A trip over the hump that late in the winter shouldn’t have been a problem, but a howling snowstorm caught Annie and Dutch Em by surprise. The blizzard raged for three days.

When searchers found Annie, she was crawling through the snow, delirious, wearing only a thin covering of clothes. She had given almost all her clothing to Dutch Em, trying to keep her friend warm. It was a futile attempt. Dutch Em froze to death.

Annie survived the ordeal, but her feet were so badly frost bitten they had to be amputated. She was a fighter, though, and the loss of her feet didn't slow her down much. Though friends made crude artificial limbs for her, Annie usually found it faster to get around by crawling.

For many years after that Annie ran a restaurant and rooming house. The miners had a lot of respect for the tough Idaho lady they nick-named Peg Leg Annie.

Annie was just four years old, and she arrived in a backpack carried by her father.

It was when she was 38 years old and had five children of her own that Annie--then Annie Morrow--experienced the tragedy that made her an Idaho legend.

In the late spring of 1898 she and a lady friend called Dutch Em decided to make a snowshoe trip from Atlanta over the mountains to Rocky Bar. A trip over the hump that late in the winter shouldn’t have been a problem, but a howling snowstorm caught Annie and Dutch Em by surprise. The blizzard raged for three days.

When searchers found Annie, she was crawling through the snow, delirious, wearing only a thin covering of clothes. She had given almost all her clothing to Dutch Em, trying to keep her friend warm. It was a futile attempt. Dutch Em froze to death.

Annie survived the ordeal, but her feet were so badly frost bitten they had to be amputated. She was a fighter, though, and the loss of her feet didn't slow her down much. Though friends made crude artificial limbs for her, Annie usually found it faster to get around by crawling.

For many years after that Annie ran a restaurant and rooming house. The miners had a lot of respect for the tough Idaho lady they nick-named Peg Leg Annie.

Published on December 28, 2022 04:00