Rick Just's Blog, page 74

December 17, 2022

A Message from Space (tap to read)

In July of 1969, much of the world’s attention was on the moon. At that same time, more than 34,000 scouts were attending the National Boy Scout Jamboree at Farragut State Park in Idaho. Astronaut Col. Frank Borman delivered a message from President Nixon on the closing night of the jamboree and presented a film from Neil Armstrong’s first step on the moon, which had occurred a few days before. Only a handful of Scouts had seen the televised event, so the entire crowd sat spellbound watching the scene from the moon and hearing Armstrong’s words. Both Borman and Armstrong were former Scouts.

Armstrong acknowledged the Scouts from space on his way to the moon, saying “Hello to my fellow scouts and scouters at Farragut National Park in Idaho.” No one bothered to tell Commander Armstrong that it was actually a state park.

Armstrong acknowledged the Scouts from space on his way to the moon, saying “Hello to my fellow scouts and scouters at Farragut National Park in Idaho.” No one bothered to tell Commander Armstrong that it was actually a state park.

Published on December 17, 2022 04:00

December 16, 2022

When the Idaho Burned in New York (tap to read)

Idaho's Lake Coeur d'Alene was known especially for its steamships that slid back and forth across the waters from the 1880s to the 1930s. One of the better-known boats was the sidewheeler, Idaho.

Would it surprise you to learn that a steamboat named Idaho burned to the waterline and sank on November 26, 1866? This Idaho never knew Lake Coeur d'Alene. Instead, it worked the waters of the East River, New York City.

The Idaho was one of the newer boats of the Brooklyn Ferry Company. Shortly after leaving the dock about 7:10 in the evening, what may have been a smoldering fire broke through the ferry's deck and started to rapidly consume the Idaho. Fortunately, a sister ferry, the Canada, was nearby. The captain of the Canada pulled alongside the burning boat long enough for most of the passengers to jump aboard. Heavy flames forced the Canada to pull away before everyone could get aboard. A woman and her child jumped into the water and were saved from drowning by two men. One of the men suffered serious burns in the rescue, but there were no fatalities.

The Idaho, which was not insured, was a total loss. Authorities estimated it was worth $64,000.

The fire aboard a boat named after the state didn't cause a ripple in Idaho newspapers at the time, so it falls to me to break the news to you 156 years later. You're welcome.

[image error]

Would it surprise you to learn that a steamboat named Idaho burned to the waterline and sank on November 26, 1866? This Idaho never knew Lake Coeur d'Alene. Instead, it worked the waters of the East River, New York City.

The Idaho was one of the newer boats of the Brooklyn Ferry Company. Shortly after leaving the dock about 7:10 in the evening, what may have been a smoldering fire broke through the ferry's deck and started to rapidly consume the Idaho. Fortunately, a sister ferry, the Canada, was nearby. The captain of the Canada pulled alongside the burning boat long enough for most of the passengers to jump aboard. Heavy flames forced the Canada to pull away before everyone could get aboard. A woman and her child jumped into the water and were saved from drowning by two men. One of the men suffered serious burns in the rescue, but there were no fatalities.

The Idaho, which was not insured, was a total loss. Authorities estimated it was worth $64,000.

The fire aboard a boat named after the state didn't cause a ripple in Idaho newspapers at the time, so it falls to me to break the news to you 156 years later. You're welcome.

[image error]

Published on December 16, 2022 04:00

December 15, 2022

UXB Boise (tap to read)

The purpose of a fuse in the placement of dynamite is to give the person lighting the charge time to get away. Typically, that time is measured in seconds, not years.

While building a road along the bank of the New York Canal in 1900, the crew doing the dirt work found a fuse. Digging a little more carefully, they found the fuse was attached to a charge of dynamite. Rather than move what might be an unstable explosive, they chose to light the fuse and light out of there. The dynamite went off, just as whoever had set the charge ten years earlier had intended.

Speculation was that the lost explosive had been put in place while another crew was digging the New York Canal in 1890. Maybe they stopped for lunch, or they went home at the end of the day forgetting about that particular charge, which was planted near the Foote House just below where Lucky Peak Dam is today. Whoever placed the dynamite and inserted the fuse probably never thought it would have a ten-year delay.

While building a road along the bank of the New York Canal in 1900, the crew doing the dirt work found a fuse. Digging a little more carefully, they found the fuse was attached to a charge of dynamite. Rather than move what might be an unstable explosive, they chose to light the fuse and light out of there. The dynamite went off, just as whoever had set the charge ten years earlier had intended.

Speculation was that the lost explosive had been put in place while another crew was digging the New York Canal in 1890. Maybe they stopped for lunch, or they went home at the end of the day forgetting about that particular charge, which was planted near the Foote House just below where Lucky Peak Dam is today. Whoever placed the dynamite and inserted the fuse probably never thought it would have a ten-year delay.

Published on December 15, 2022 04:00

December 14, 2022

The Sun Dance (tap to read)

When you think of dancing today, images of people having fun probably pop into your head. Yet, dancing has been prohibited in many times and places throughout history. Some adherents to religions from Islam to Baptists forbid dancing.

Dance is a vital part of other religions. That brings us to a moment in Idaho history where a particular dance was outlawed.

A headline in the Blackfoot Optimist in 1912 read, “Last Indian Sun Dance.” The tribes of the Fort Hall reservation were about to hold what would “be the last dance ever held on the reservation.”

The Indian Department in Washington, DC had issued an edict that the tribal custom of holding a sun dance would be prohibited in future years. Why? “It is claimed by those in authority that those dances interfere with and retard the process of teaching the Indians the necessity of following the white man’s example of engaging in agricultural pursuits, rather than those of their more savage ancestry,” the article explained.

Sun dances seem to have originated with the plains Indians. However, by the late 1900s, they had spread to the Shoshone of Wyoming and Idaho. The days-long ceremonies varied by tribe and varied from year to year depending on the vision a medicine man had received.

You may think of sun dances as the ritual where a warrior’s pectoral muscles are pierced and rawhide thongs run through the piercings. In that version, a rope is tied to a center pole and the embedded thongs while the warrior leans back to endure the pain. While some sun dances feature that display of personal sacrifice, they more commonly involve tribal members dancing from the center pole and back to the edge for hours on end, often fainting from exhaustion.

In the Shoshone Sun Dance, tribal members erected a circular enclosure of poles and brush, about 60-75 feet in diameter. The center pole was cut from a birch tree ceremonially chosen for that purpose.

A 1918 story in the Idaho Republican described the dance this way: “Around the edge of the dancing space were a number of peeled poles to which the dancers could hold or rest against when not in action. Each dancer had his own particular station, and the method of dancing was to dance straight up to the center pole and then backwards to the station to the outer ring.” The dance described in that article lasted “from sunset Tuesday to sunrise Saturday.”

That 1918 story, as clever readers will note, came after the “last dance” story in the Blackfoot paper in 1912. That’s because tribal members had held the dance despite the prohibition. They did so regularly and continue the tradition today. In 1978, Congress passed the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, which codified the right of Native Americans to freely practice their religious rights, including the Sun Dance.

In that same 1912 paper that mentioned their “savage ancestry,” the writer was troubled by the discontinuation of the ritual. “In compelling them to discontinue one of the most sacred forms of religion, there is a question as to whether any man has a right to forcibly interfere with anyone’s religious belief.”

Indeed.

A Shoshone sun dance on the Fort Hall Reservation in 1925.

A Shoshone sun dance on the Fort Hall Reservation in 1925.

Dance is a vital part of other religions. That brings us to a moment in Idaho history where a particular dance was outlawed.

A headline in the Blackfoot Optimist in 1912 read, “Last Indian Sun Dance.” The tribes of the Fort Hall reservation were about to hold what would “be the last dance ever held on the reservation.”

The Indian Department in Washington, DC had issued an edict that the tribal custom of holding a sun dance would be prohibited in future years. Why? “It is claimed by those in authority that those dances interfere with and retard the process of teaching the Indians the necessity of following the white man’s example of engaging in agricultural pursuits, rather than those of their more savage ancestry,” the article explained.

Sun dances seem to have originated with the plains Indians. However, by the late 1900s, they had spread to the Shoshone of Wyoming and Idaho. The days-long ceremonies varied by tribe and varied from year to year depending on the vision a medicine man had received.

You may think of sun dances as the ritual where a warrior’s pectoral muscles are pierced and rawhide thongs run through the piercings. In that version, a rope is tied to a center pole and the embedded thongs while the warrior leans back to endure the pain. While some sun dances feature that display of personal sacrifice, they more commonly involve tribal members dancing from the center pole and back to the edge for hours on end, often fainting from exhaustion.

In the Shoshone Sun Dance, tribal members erected a circular enclosure of poles and brush, about 60-75 feet in diameter. The center pole was cut from a birch tree ceremonially chosen for that purpose.

A 1918 story in the Idaho Republican described the dance this way: “Around the edge of the dancing space were a number of peeled poles to which the dancers could hold or rest against when not in action. Each dancer had his own particular station, and the method of dancing was to dance straight up to the center pole and then backwards to the station to the outer ring.” The dance described in that article lasted “from sunset Tuesday to sunrise Saturday.”

That 1918 story, as clever readers will note, came after the “last dance” story in the Blackfoot paper in 1912. That’s because tribal members had held the dance despite the prohibition. They did so regularly and continue the tradition today. In 1978, Congress passed the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, which codified the right of Native Americans to freely practice their religious rights, including the Sun Dance.

In that same 1912 paper that mentioned their “savage ancestry,” the writer was troubled by the discontinuation of the ritual. “In compelling them to discontinue one of the most sacred forms of religion, there is a question as to whether any man has a right to forcibly interfere with anyone’s religious belief.”

Indeed.

A Shoshone sun dance on the Fort Hall Reservation in 1925.

A Shoshone sun dance on the Fort Hall Reservation in 1925.

Published on December 14, 2022 04:00

December 13, 2022

The Governors Stevenson (tap to read)

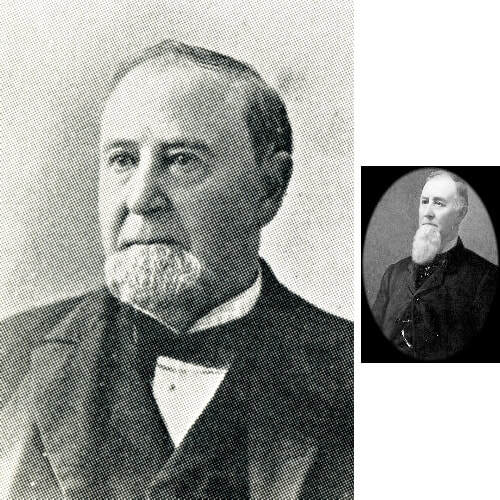

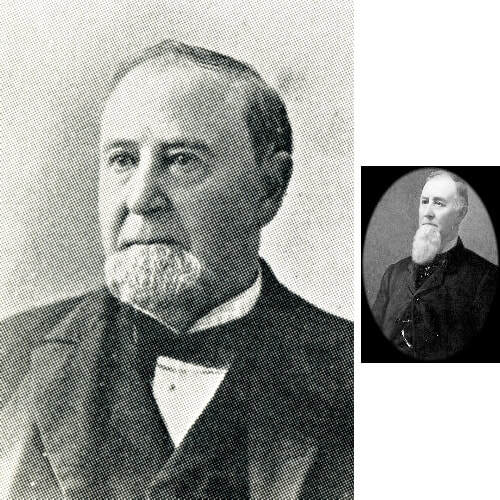

Edward A. Stevenson was the governor of Idaho Territory from October 10, 1885, to April 30, 1889. Governors during territorial days were all appointed by the president. The qualifications for the post were scant, beyond knowing the president or knowing someone who knew the president.

Stevenson, though, had some qualifications. One of the forty-niners drawn to the West by gold, he had been a Justice of the Peace and a state legislator while living in California. He rose to be the Speaker pro Tempore in the legislature. He also served at one time or another as a deputy sheriff and the mayor of Coloma, California.

In 1863, Stevenson followed rumors of gold to Idaho, settling in the Boise Basin. The following year he was elected as a Justice of the Peace. He ran for the Idaho Territorial Legislature half a dozen times, winning half those races, and ultimately became Speaker of the House.

Having some solid political credentials wasn’t Stevenson’s only claim to fame. He was the first Idaho Territorial Governor who resided in the state at the time of his appointment. He was also the only Democrat to serve as governor of the territory.

Edward A. Stevenson probably gave some pointers about being a governor to his older brother, Charles C. Stevenson, who was governor of the State of Nevada from January 3, 1887, to September 21, 1890. The terms of the brother governors overlapped for a couple of years.

Idaho Territorial Governor Edward A. Stevenson on the left. On the right is his brother, Nevada Governor Charles C. Stevenson, his brother.

Idaho Territorial Governor Edward A. Stevenson on the left. On the right is his brother, Nevada Governor Charles C. Stevenson, his brother.

Stevenson, though, had some qualifications. One of the forty-niners drawn to the West by gold, he had been a Justice of the Peace and a state legislator while living in California. He rose to be the Speaker pro Tempore in the legislature. He also served at one time or another as a deputy sheriff and the mayor of Coloma, California.

In 1863, Stevenson followed rumors of gold to Idaho, settling in the Boise Basin. The following year he was elected as a Justice of the Peace. He ran for the Idaho Territorial Legislature half a dozen times, winning half those races, and ultimately became Speaker of the House.

Having some solid political credentials wasn’t Stevenson’s only claim to fame. He was the first Idaho Territorial Governor who resided in the state at the time of his appointment. He was also the only Democrat to serve as governor of the territory.

Edward A. Stevenson probably gave some pointers about being a governor to his older brother, Charles C. Stevenson, who was governor of the State of Nevada from January 3, 1887, to September 21, 1890. The terms of the brother governors overlapped for a couple of years.

Idaho Territorial Governor Edward A. Stevenson on the left. On the right is his brother, Nevada Governor Charles C. Stevenson, his brother.

Idaho Territorial Governor Edward A. Stevenson on the left. On the right is his brother, Nevada Governor Charles C. Stevenson, his brother.

Published on December 13, 2022 04:00

December 12, 2022

The Newspaper Exchange (tap to read)

Newspapers in 19th Century Idaho contained stories from all over the state, long before they had wire services. This was possible because of some progressive thinking in Congress. Yes, you read that right.

Beginning in the early 1800s, Congress allowed publishers to send their newspapers to other publishers for free through the US Postal Service. This newspaper exchange was an important program to encourage freedom of the press. Unfortunately, it did have at least a couple of unintended consequences.

Land promoters sometimes threw together a tiny newspaper in their otherwise barren community to extoll the virtues of their particular tract of sagebrush. Knowing no better, editors of newspapers in other parts of the country would pick up the story and run it just as if it were true. “I read it in the newspaper” was likely proof for many that something was so. If this reminds you of people “doing my own research” on the internet today, you are not alone.

Land scams probably caught more people a thousand miles away than they did Idahoans in neighboring communities. That doesn’t mean the practice of sharing stories from other newspapers was always a positive thing. For instance, readers in Sandpoint probably didn’t care much about what an average citizen in Blackfoot was doing, even though it might be exciting news locally. But newspapers would pick up quirky or scandalous stories because they knew that would interest their readers. This tended to skew the news toward sensationalism.

I recently ran across a story with an Idaho connection that had made the rounds. It was quirky, sensational, and certainly a complete figment of someone’s imagination. I saw it in an 1866 issue of the Vincennes Times, a newspaper in Vincennes, Indiana. They had picked up the story from the Newville, Pennsylvania Star of the Valley. It seems that a young man visiting Idaho about four months previous had been drinking from a small pond. While quenching his thirst, a snake found its way into his mouth and slipped all the way down into his stomach.

The young man did not feel good about it. He was sure he was about to die, so he went home to Pennsylvania to do so.

The victim consulted several medical men about his snake-in-the-stomach problem, complaining especially that he couldn’t shake a feeling of cold in that region of his body. Several things—unlisted—were tried without success. Finally, a doctor prescribed an emetic. The young man vomited up an 18-inch-long snake, which tried to take its revenge by trying to strangle him when it came out.

And that’s the news for today.

Beginning in the early 1800s, Congress allowed publishers to send their newspapers to other publishers for free through the US Postal Service. This newspaper exchange was an important program to encourage freedom of the press. Unfortunately, it did have at least a couple of unintended consequences.

Land promoters sometimes threw together a tiny newspaper in their otherwise barren community to extoll the virtues of their particular tract of sagebrush. Knowing no better, editors of newspapers in other parts of the country would pick up the story and run it just as if it were true. “I read it in the newspaper” was likely proof for many that something was so. If this reminds you of people “doing my own research” on the internet today, you are not alone.

Land scams probably caught more people a thousand miles away than they did Idahoans in neighboring communities. That doesn’t mean the practice of sharing stories from other newspapers was always a positive thing. For instance, readers in Sandpoint probably didn’t care much about what an average citizen in Blackfoot was doing, even though it might be exciting news locally. But newspapers would pick up quirky or scandalous stories because they knew that would interest their readers. This tended to skew the news toward sensationalism.

I recently ran across a story with an Idaho connection that had made the rounds. It was quirky, sensational, and certainly a complete figment of someone’s imagination. I saw it in an 1866 issue of the Vincennes Times, a newspaper in Vincennes, Indiana. They had picked up the story from the Newville, Pennsylvania Star of the Valley. It seems that a young man visiting Idaho about four months previous had been drinking from a small pond. While quenching his thirst, a snake found its way into his mouth and slipped all the way down into his stomach.

The young man did not feel good about it. He was sure he was about to die, so he went home to Pennsylvania to do so.

The victim consulted several medical men about his snake-in-the-stomach problem, complaining especially that he couldn’t shake a feeling of cold in that region of his body. Several things—unlisted—were tried without success. Finally, a doctor prescribed an emetic. The young man vomited up an 18-inch-long snake, which tried to take its revenge by trying to strangle him when it came out.

And that’s the news for today.

Published on December 12, 2022 04:00

December 11, 2022

German Harassment in Boise (tap to read)

In a previous post, I mentioned that the lettering above the building at 6th and Main had been sandblasted away. It had once read “Boise Turnverein,” marking the entrance to a club for those of German descent. The club was disbanded, and the building sold when anti-German fever was rampant in Boise at the beginning of World War I.

I ran across another example of that sentiment in a couple of issues of the Idaho Statesman from November 1917.

C.G. Goetling, who ran a farm near Eagle, was surprised to see a crowd of men approaching him one November day. They were upset about his hay derrick. Goetling sensed some danger, but he tried joking with them about it. They didn’t like the colors he had used to paint the derrick. The pole was red and white with a strip of black tar on one end. Those were the colors of the German flag. Since Goetling was of German descent, the men confronting him did not think it an accident.

Goetling told them that he had painted the derrick with paint he happened to have on hand about seven years earlier. The ruffians demanded that he paint it red, white, and blue in honor of the American flag. They had brought along paint for that purpose. With sufficient prodding, he did as they asked. It still wasn’t enough for them.

The men produced an American flag, placed it on the ground, and demanded Goetling kneel and kiss it.

“Boys, this is asking too much,” Goetling said. “I kneel only to my Gott.” Someone in the crowd murmured, “And the Kaiser.”

As the paper reported, “He refused stubbornly until one of the party, a husky lad of considerable weight and conviction approached him with the command: ‘Get down on your knees and kiss that flag, before we get tough with you.’”

Goetling saw there was no way out, so he knelt and buried his face in the folds of the flag.

The crowd still wasn’t done with him. They accused him of donating $1,000 to Germany for the war effort and demanded he agree to donate $50 to the YMCA. After getting his agreement to that, they left the farmer alone.

Two days later, Goetling appeared in the offices of the Statesman to defend himself. He told a reporter that the paint on the derrick was old, that he had not donated any money to Germany, and that his son was serving in the army. The Statesman checked that last part of the story and found it to be true.

Goetling told the paper he had come to the U.S. in 1880 and was a naturalized citizen, having lived in Idaho for 12 years. His wife, born in Canada, said, “Charges of this kind are hard to bear when we have done what we could. My husband gave apples for the soldiers, and I have helped with Red Cross work. The red, white, and black paint on the derrick was put there seven years ago, and the black was not paint but a stripe of tar put on to protect the wood.”

Nothing more of the incident was reported. I could find only two more mentions of the Goetlings in the paper. A couple of weeks after the incident, Mrs. Goetling went home to Canada, whether for a visit or for good, was not stated. Then, in August of 1918, the Goetling house burned to the ground, with nothing left to be salvaged. No cause of the fire was given.

I ran across another example of that sentiment in a couple of issues of the Idaho Statesman from November 1917.

C.G. Goetling, who ran a farm near Eagle, was surprised to see a crowd of men approaching him one November day. They were upset about his hay derrick. Goetling sensed some danger, but he tried joking with them about it. They didn’t like the colors he had used to paint the derrick. The pole was red and white with a strip of black tar on one end. Those were the colors of the German flag. Since Goetling was of German descent, the men confronting him did not think it an accident.

Goetling told them that he had painted the derrick with paint he happened to have on hand about seven years earlier. The ruffians demanded that he paint it red, white, and blue in honor of the American flag. They had brought along paint for that purpose. With sufficient prodding, he did as they asked. It still wasn’t enough for them.

The men produced an American flag, placed it on the ground, and demanded Goetling kneel and kiss it.

“Boys, this is asking too much,” Goetling said. “I kneel only to my Gott.” Someone in the crowd murmured, “And the Kaiser.”

As the paper reported, “He refused stubbornly until one of the party, a husky lad of considerable weight and conviction approached him with the command: ‘Get down on your knees and kiss that flag, before we get tough with you.’”

Goetling saw there was no way out, so he knelt and buried his face in the folds of the flag.

The crowd still wasn’t done with him. They accused him of donating $1,000 to Germany for the war effort and demanded he agree to donate $50 to the YMCA. After getting his agreement to that, they left the farmer alone.

Two days later, Goetling appeared in the offices of the Statesman to defend himself. He told a reporter that the paint on the derrick was old, that he had not donated any money to Germany, and that his son was serving in the army. The Statesman checked that last part of the story and found it to be true.

Goetling told the paper he had come to the U.S. in 1880 and was a naturalized citizen, having lived in Idaho for 12 years. His wife, born in Canada, said, “Charges of this kind are hard to bear when we have done what we could. My husband gave apples for the soldiers, and I have helped with Red Cross work. The red, white, and black paint on the derrick was put there seven years ago, and the black was not paint but a stripe of tar put on to protect the wood.”

Nothing more of the incident was reported. I could find only two more mentions of the Goetlings in the paper. A couple of weeks after the incident, Mrs. Goetling went home to Canada, whether for a visit or for good, was not stated. Then, in August of 1918, the Goetling house burned to the ground, with nothing left to be salvaged. No cause of the fire was given.

Published on December 11, 2022 04:00

December 10, 2022

Protesting Coxeyites end up in Boise (tap to read)

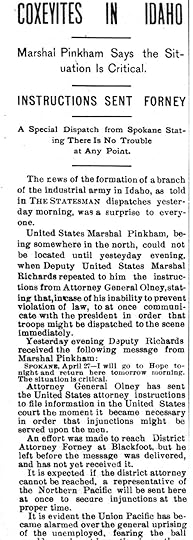

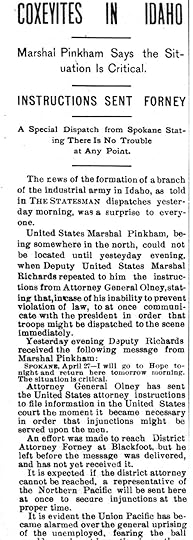

“Two Hundred Coxeyites Sentenced in Boise, Idaho,” read the headline in The Christian Recorder Magazine's June 7, 1894 edition.

That caught my attention while searching for Idaho subjects to research. First, when you sentence 200 people for anything, there must be a story behind it. Second, what the heck were Coxeyites?

Those commonly known as Coxeyites or Coxey's Army were also the Army of the Commonwealth in Christ. They were unemployed workers who organized for what was the first significant protest march on Washington, DC.

In 1894 there were plenty of unemployed people. The country was in the middle of the worst economic depression to date. Those out of work began to get behind Jacob Sechler Coxey, Sr. He had a big idea about infrastructure in the nation. A Socialist Party member, Coxey wanted to issue $500 million in paper money backed by government bonds. That money would land in the pockets of workers building roads nationwide. The idea would be echoed in the New Deal programs of the Great Depression a few decades later.

To say that he had some support is akin to saying there are a few stars in the sky. Tens of thousands of jobless men began to make their way toward Washington to have their voices heard.

There were a few problems associated with the march. First, these were men without money. How would they get to DC? Once they got there, where would they stay? What would they eat?

A large number of Coxeyites set out from the Pacific Northwest. Many of them had formerly been railroad workers who blamed their problems on their employer. So the army of workers hopped freights headed east.

As they traveled across the country, members of Coxey's Army were cheered along and often given food by local supporters. Railroads were less eager to help.

Coxeyites, frustrated by that lack of eagerness, began commandeering trains to take them east. In reaction, the railroads began throwing every obstacle they could in the way of the men. They parked dead train engines on the tracks in Montana and Kansas, emptied water tanks—essential for steam engines—and even tore up tracks. The Coxeyites often just laid new track around the obstacles. To refill the purloined engines, they would stop at wells and use buckets and cups to dump water into the tanks.

Troops were called up in some states to stop the Coxeyites. But, more than once, the unemployed men turned the tables on those who would keep them from their destination, capturing the firearms meant to capture the Coxeyites.

At Huntington, Oregon, just a few miles from the Idaho border, about 250 Coxeyites demanded that the Union Pacific Railroad give them a ride east. UP resisted at first, fearing that caving in would set a precedent that would result in hundreds more Coxeyites demanding free passage up and down the West Coast.

Ultimately, the company relented “under protest” and agreed to let the Coxeyites ride across Idaho.

Many locals across Southern Idaho cheered this victory for the unemployed men. In Pocatello, when about 300 Coxeyites pulled into town, sympathizers raised money for food and clothing.

Meanwhile, Union Pacific officials decided letting the men ride for free was a mistake. As feared, other members of Coxey's Army started demanding a free ride. It was time to put a stop to it.

At the railroad's request, U.S. Marshall for Idaho, Joseph Pinkham, sent men to the border with Oregon to keep more Coxeyites from coming into the state. He headed up a cadre of marshals and volunteers that went to Montpelier to keep the Coxeyites from entering Wyoming.

Coxey's army had other ideas. The men spent a day and most of a night arguing with the citizens of Montpelier, then with Marshall Pinkham, in what one newspaper reporter called "the most exciting day in the history of southeastern Idaho." Pinkham arrested a local man who was encouraging the Coxeyites to ignore a federal order to stand down. The crowd of the unemployed demanded his release, but Pinkham did not acquiesce. The tense standoff broke when Pinkham's train retreated from Montpellier with the arrestee.

A short time after the Pinkham train left, several of the men broke into the roundhouse and stole a locomotive. That engine jumped the tracks at a switch, disabling it. The men stole two more engines in Montpelier and charged into Wyoming at 6:22 in the morning.

That Montpelier triumph was short-lived for the Coxeyites. The train-nappers were overpowered in Green River and arrested.

The men found themselves back on a train, the occupants of guarded cattle cars on their way west, not east. About 200 were on their way to Boise for trial related to the stolen locomotive caper in mid-May 1894.

Housing 200 prisoners would prove a challenge. At first, they were to be housed at the prison. When authorities determined there wasn't room there, they decided to quarter them in the old post office. Again, not enough space.

When the Coxyites pulled into town, the boxcars they rode in rolled into the roundhouse and stopped. And that's where they stayed. Officials parked the boxcars around and within the roundhouse and charged two companies of troops and a posse of deputies with guarding them.

The roundhouse and surrounding grounds, where the newspaper reported the prisoners "frolicked around on the grass like boys out for a holiday," quickly became known as Camp Pinkham. For his part, Pinkham looked out for his prisoners' interests. He ordered a 28-foot by 100-foot building erected for them to sleep in while waiting for Judge Beatty to come back from a trip to North Idaho.

On the judge's return in late May, the trial began. Justice was swift. On June 5, the judge handed out sentences. Those who led the Coxeyites in stealing the train in Montpelier got the worst of it, each sentenced to six months in jail. The remainder of the men got sentences of 30 to 60 days. They spent their sentences in a temporary prison near Huntington, Oregon.

So, the Coxeyites who chose the path through southern Idaho on their aborted journey to Washington, DC, spent their summer in a crude enclosure along the bank of the Snake River instead.

Several delegations of Coxey's Army did make it to Washington, DC over that summer. Their protests changed little, but it marked the beginning of many marches on Washington for various causes that continue to this day.

That caught my attention while searching for Idaho subjects to research. First, when you sentence 200 people for anything, there must be a story behind it. Second, what the heck were Coxeyites?

Those commonly known as Coxeyites or Coxey's Army were also the Army of the Commonwealth in Christ. They were unemployed workers who organized for what was the first significant protest march on Washington, DC.

In 1894 there were plenty of unemployed people. The country was in the middle of the worst economic depression to date. Those out of work began to get behind Jacob Sechler Coxey, Sr. He had a big idea about infrastructure in the nation. A Socialist Party member, Coxey wanted to issue $500 million in paper money backed by government bonds. That money would land in the pockets of workers building roads nationwide. The idea would be echoed in the New Deal programs of the Great Depression a few decades later.

To say that he had some support is akin to saying there are a few stars in the sky. Tens of thousands of jobless men began to make their way toward Washington to have their voices heard.

There were a few problems associated with the march. First, these were men without money. How would they get to DC? Once they got there, where would they stay? What would they eat?

A large number of Coxeyites set out from the Pacific Northwest. Many of them had formerly been railroad workers who blamed their problems on their employer. So the army of workers hopped freights headed east.

As they traveled across the country, members of Coxey's Army were cheered along and often given food by local supporters. Railroads were less eager to help.

Coxeyites, frustrated by that lack of eagerness, began commandeering trains to take them east. In reaction, the railroads began throwing every obstacle they could in the way of the men. They parked dead train engines on the tracks in Montana and Kansas, emptied water tanks—essential for steam engines—and even tore up tracks. The Coxeyites often just laid new track around the obstacles. To refill the purloined engines, they would stop at wells and use buckets and cups to dump water into the tanks.

Troops were called up in some states to stop the Coxeyites. But, more than once, the unemployed men turned the tables on those who would keep them from their destination, capturing the firearms meant to capture the Coxeyites.

At Huntington, Oregon, just a few miles from the Idaho border, about 250 Coxeyites demanded that the Union Pacific Railroad give them a ride east. UP resisted at first, fearing that caving in would set a precedent that would result in hundreds more Coxeyites demanding free passage up and down the West Coast.

Ultimately, the company relented “under protest” and agreed to let the Coxeyites ride across Idaho.

Many locals across Southern Idaho cheered this victory for the unemployed men. In Pocatello, when about 300 Coxeyites pulled into town, sympathizers raised money for food and clothing.

Meanwhile, Union Pacific officials decided letting the men ride for free was a mistake. As feared, other members of Coxey's Army started demanding a free ride. It was time to put a stop to it.

At the railroad's request, U.S. Marshall for Idaho, Joseph Pinkham, sent men to the border with Oregon to keep more Coxeyites from coming into the state. He headed up a cadre of marshals and volunteers that went to Montpelier to keep the Coxeyites from entering Wyoming.

Coxey's army had other ideas. The men spent a day and most of a night arguing with the citizens of Montpelier, then with Marshall Pinkham, in what one newspaper reporter called "the most exciting day in the history of southeastern Idaho." Pinkham arrested a local man who was encouraging the Coxeyites to ignore a federal order to stand down. The crowd of the unemployed demanded his release, but Pinkham did not acquiesce. The tense standoff broke when Pinkham's train retreated from Montpellier with the arrestee.

A short time after the Pinkham train left, several of the men broke into the roundhouse and stole a locomotive. That engine jumped the tracks at a switch, disabling it. The men stole two more engines in Montpelier and charged into Wyoming at 6:22 in the morning.

That Montpelier triumph was short-lived for the Coxeyites. The train-nappers were overpowered in Green River and arrested.

The men found themselves back on a train, the occupants of guarded cattle cars on their way west, not east. About 200 were on their way to Boise for trial related to the stolen locomotive caper in mid-May 1894.

Housing 200 prisoners would prove a challenge. At first, they were to be housed at the prison. When authorities determined there wasn't room there, they decided to quarter them in the old post office. Again, not enough space.

When the Coxyites pulled into town, the boxcars they rode in rolled into the roundhouse and stopped. And that's where they stayed. Officials parked the boxcars around and within the roundhouse and charged two companies of troops and a posse of deputies with guarding them.

The roundhouse and surrounding grounds, where the newspaper reported the prisoners "frolicked around on the grass like boys out for a holiday," quickly became known as Camp Pinkham. For his part, Pinkham looked out for his prisoners' interests. He ordered a 28-foot by 100-foot building erected for them to sleep in while waiting for Judge Beatty to come back from a trip to North Idaho.

On the judge's return in late May, the trial began. Justice was swift. On June 5, the judge handed out sentences. Those who led the Coxeyites in stealing the train in Montpelier got the worst of it, each sentenced to six months in jail. The remainder of the men got sentences of 30 to 60 days. They spent their sentences in a temporary prison near Huntington, Oregon.

So, the Coxeyites who chose the path through southern Idaho on their aborted journey to Washington, DC, spent their summer in a crude enclosure along the bank of the Snake River instead.

Several delegations of Coxey's Army did make it to Washington, DC over that summer. Their protests changed little, but it marked the beginning of many marches on Washington for various causes that continue to this day.

Published on December 10, 2022 04:00

December 9, 2022

Bringing Back the Body (tap to read)

Pro tip: Tempting as it may be to stand on a snow cornice on the edge of a deep crater, wind howling around you, then lean over to peer into the abyss, don’t. Just don’t.

We are meant to learn from history, so here’s the cautionary tale of C.E. Bell

In February 1907, Bell and two companions were walking in the Owyhees near the head of the Bruneau River. What they were doing out there goes unsaid in the reports about Bell’s fate, but they were part-time miners, so let’s assume searching for some precious metal was their goal.

The three were trudging across a snowy mountain when Bell got ahead of his companions. Breathless, the companions got to the top of the ridge and saw that it was a volcanic crater. Bell, maybe a hundred yards ahead of them, seemed determined to peek into the crater. From their vantage point they saw that Bell had walked out onto an ice bridge covered with several feet of snow. They yelled to Bell to warn him of his precarious position, but whipping wind took their words away.

While the two watched helplessly, C.E. Bell reached the edge of the cornice and leaned over to peer into the crater. It will not be a shock to you a century and more away to learn that the cornice gave way, sending Bell windmilling into the crater bowl.

Bell’s companions, never named in newspaper reports, trekked back to Jarbidge to stir up a rescue effort. A large party responded. One would-be rescuer dropped over the edge of the crater on a rope to see what he could see. When he reached a depth of 200 feet he saw an empty ledge another 400 feet below him, then a drop-off into the dark.

Determining that rescue was impossible, the men returned to Jarbidge.

On May 28, two other prospectors found the body of C.E. Bell 800 feet below the rim of the crater.

Bell had been a member of the Oddfellows Lodge of Twin Falls. That group paid a reward of $300 to bring his body back.

We are meant to learn from history, so here’s the cautionary tale of C.E. Bell

In February 1907, Bell and two companions were walking in the Owyhees near the head of the Bruneau River. What they were doing out there goes unsaid in the reports about Bell’s fate, but they were part-time miners, so let’s assume searching for some precious metal was their goal.

The three were trudging across a snowy mountain when Bell got ahead of his companions. Breathless, the companions got to the top of the ridge and saw that it was a volcanic crater. Bell, maybe a hundred yards ahead of them, seemed determined to peek into the crater. From their vantage point they saw that Bell had walked out onto an ice bridge covered with several feet of snow. They yelled to Bell to warn him of his precarious position, but whipping wind took their words away.

While the two watched helplessly, C.E. Bell reached the edge of the cornice and leaned over to peer into the crater. It will not be a shock to you a century and more away to learn that the cornice gave way, sending Bell windmilling into the crater bowl.

Bell’s companions, never named in newspaper reports, trekked back to Jarbidge to stir up a rescue effort. A large party responded. One would-be rescuer dropped over the edge of the crater on a rope to see what he could see. When he reached a depth of 200 feet he saw an empty ledge another 400 feet below him, then a drop-off into the dark.

Determining that rescue was impossible, the men returned to Jarbidge.

On May 28, two other prospectors found the body of C.E. Bell 800 feet below the rim of the crater.

Bell had been a member of the Oddfellows Lodge of Twin Falls. That group paid a reward of $300 to bring his body back.

Published on December 09, 2022 04:00

December 8, 2022

Chuck Wells (tap to read)

Today’s post is an example of history being made while we don’t even notice it.

In the early 1970s, Chuck Wells’ dream job at the Idaho Department of Parks came along. Wells had a degree in recreation from the University of Oregon, and at the time, was working as the manager of Idaho’s Heyburn State Park. The agency was adding Recreation to its name, and they needed someone to figure out how to develop a program for off-road motor vehicles. ATVs were still a new thing, but motorbikes were really taking off. Snowmobiles had been around for a while, but they were finally starting to be reliable and easy to run. People needed places to ride.

So, Chuck Wells started making riding opportunities, not with a shovel and an ax, but with his pen. He worked on legislation, creating the Motorbike Recreation Fund Act in Idaho in 1972, the first registration program for off-highway motorbikes. But it wasn’t a way to make money for the state. It was a way to pool money from trail users to maintain the trails they enjoyed.

Chuck used that user-pay philosophy in most of the nine pieces of legislation he wrote and got passed. It had worked for motorbikes, so he took the idea to snowmobilers and OHV riders. It resulted in vastly improved trails for summer users and a whole new system of trails in Idaho for snowmobilers. State after state copied Chuck’s ideas. And it wasn’t just motorized trail users who benefited. They got to use the same trails, but they also benefited from Chuck’s imagination when it came time to develop Idaho’s Park N’ Ski cross-country ski system.

We sometimes disparage bureaucrats, maybe when we’re waiting in line at the DMV. Wells was a bureaucrat in the best sense of the term. He dedicated his life to giving thousands of outdoor recreationists opportunities to enjoy Idaho.

These days, more than 165,000 Off-Highway Vehicles use the trail systems Chuck created with his programs during the summer. In addition, more than 4,500 miles of snowmobile trails are groomed each winter.

Wells received many honors for his dedication to providing recreational trails and was inducted into the International Snowmobile Hall of Fame. Chuck Wells passed away in July 2021 a legend in the history of Idaho outdoor recreation.

In the early 1970s, Chuck Wells’ dream job at the Idaho Department of Parks came along. Wells had a degree in recreation from the University of Oregon, and at the time, was working as the manager of Idaho’s Heyburn State Park. The agency was adding Recreation to its name, and they needed someone to figure out how to develop a program for off-road motor vehicles. ATVs were still a new thing, but motorbikes were really taking off. Snowmobiles had been around for a while, but they were finally starting to be reliable and easy to run. People needed places to ride.

So, Chuck Wells started making riding opportunities, not with a shovel and an ax, but with his pen. He worked on legislation, creating the Motorbike Recreation Fund Act in Idaho in 1972, the first registration program for off-highway motorbikes. But it wasn’t a way to make money for the state. It was a way to pool money from trail users to maintain the trails they enjoyed.

Chuck used that user-pay philosophy in most of the nine pieces of legislation he wrote and got passed. It had worked for motorbikes, so he took the idea to snowmobilers and OHV riders. It resulted in vastly improved trails for summer users and a whole new system of trails in Idaho for snowmobilers. State after state copied Chuck’s ideas. And it wasn’t just motorized trail users who benefited. They got to use the same trails, but they also benefited from Chuck’s imagination when it came time to develop Idaho’s Park N’ Ski cross-country ski system.

We sometimes disparage bureaucrats, maybe when we’re waiting in line at the DMV. Wells was a bureaucrat in the best sense of the term. He dedicated his life to giving thousands of outdoor recreationists opportunities to enjoy Idaho.

These days, more than 165,000 Off-Highway Vehicles use the trail systems Chuck created with his programs during the summer. In addition, more than 4,500 miles of snowmobile trails are groomed each winter.

Wells received many honors for his dedication to providing recreational trails and was inducted into the International Snowmobile Hall of Fame. Chuck Wells passed away in July 2021 a legend in the history of Idaho outdoor recreation.

Published on December 08, 2022 04:00