Rick Just's Blog, page 78

November 7, 2022

Grays Lake (Tap to read)

First, Grays Lake isn’t a lake. It’s a “high elevation, 22,000-acre bulrush marsh” according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services webpage about the site in Southeastern Idaho. It’s located about 40 miles northeast of Soda Springs.

Much of the refuge was set aside in 1908 by the Bureau of Indian Affairs for the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes to use for an irrigation project. Water is drawn down annually in the spring for irrigation, taking out all but about six inches of water. In many years the whole marsh can dry up in the summer.

The unnatural hydrology isn’t always ideal for birds, but there have still been 250 species recorded at the refuge. About 100 of those are known to nest there. Notably, Grays Lake is typically home to about 200 nesting pairs of sandhill cranes. That’s the largest nesting population of the species in the world.

Grays Lake was named for mountain man John Grey. If you’re scratching your head about why he was named Grey and the lake is Grays Lake—with an a—there is much more to trouble your gray or grey hair over than that. The mountain man was also known as Ignace Hatchiorauquasha. That last name throws my spellchecker into a desolate land where it finds no road signs. Further, on many early maps Grays Lake is marked as Days Lake. Some thought it was named for John Day, an early trapper on the Astor Expedition. He has a town in Oregon named for him, so no sobbing.

But about that name, Hatchiorauquasha. It’s Iroquois. Gray/Grey/Hatchiorauquasha was half Scottish and half Iroquois. He chose the name Ignace because he considered St. Ignatius his patron saint.

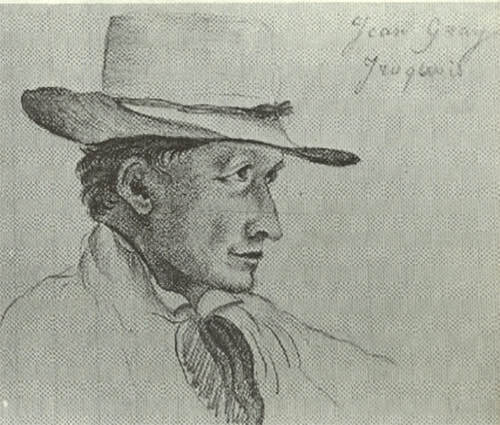

Father Nicholas Point’s sketch of John Gray. Father Point was one of the priests who traveled with Father Pierre De Smet.

Father Nicholas Point’s sketch of John Gray. Father Point was one of the priests who traveled with Father Pierre De Smet.

Much of the refuge was set aside in 1908 by the Bureau of Indian Affairs for the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes to use for an irrigation project. Water is drawn down annually in the spring for irrigation, taking out all but about six inches of water. In many years the whole marsh can dry up in the summer.

The unnatural hydrology isn’t always ideal for birds, but there have still been 250 species recorded at the refuge. About 100 of those are known to nest there. Notably, Grays Lake is typically home to about 200 nesting pairs of sandhill cranes. That’s the largest nesting population of the species in the world.

Grays Lake was named for mountain man John Grey. If you’re scratching your head about why he was named Grey and the lake is Grays Lake—with an a—there is much more to trouble your gray or grey hair over than that. The mountain man was also known as Ignace Hatchiorauquasha. That last name throws my spellchecker into a desolate land where it finds no road signs. Further, on many early maps Grays Lake is marked as Days Lake. Some thought it was named for John Day, an early trapper on the Astor Expedition. He has a town in Oregon named for him, so no sobbing.

But about that name, Hatchiorauquasha. It’s Iroquois. Gray/Grey/Hatchiorauquasha was half Scottish and half Iroquois. He chose the name Ignace because he considered St. Ignatius his patron saint.

Father Nicholas Point’s sketch of John Gray. Father Point was one of the priests who traveled with Father Pierre De Smet.

Father Nicholas Point’s sketch of John Gray. Father Point was one of the priests who traveled with Father Pierre De Smet.

Published on November 07, 2022 04:00

November 6, 2022

A Legendary Highwayman, Part 5 of 5 (Tap to read)

And now, after four days of build-up about Ed Trafton, we come to the heist that made him famous. We’ve followed him in and out of prison, trailed behind his rustled horses, and seen him betray his own mother over and over. Now we learn of the “Lone Highwayman of Yellowstone Park.”

Ed Trafton was nearing 60 in 1915, an age when most men would rather settle down and put rustling behind them. He had purchased a farm in Rupert with some of the money he had stolen from his mother. But he wanted at least one more heist before he gave up his guns.

Yellowstone National Park was country he knew well. One thing he knew about it was that in 1915 wealthy tourists who stayed at various establishments in the park toured in relative luxury, riding in spiffed up stages pulled by teams of horses. The practice was for these stages to leave every few minutes on the tour. Spacing them out assured that the well-dressed travelers did not have to endure dust from the stage ahead.

On Wednesday, July 29, 1914, the first stage left Old Faithful Lodge at about 8 am. They rolled along enjoying the scenery until they were about nine miles from the lodge. That’s when a single gunman, his lower face covered by a neckerchief, stepped out in front of the coach holding a gun.

Guns were illegal in the park, so no one in or on the stage had one.

James C. Pinkston, who was visiting Yellowstone from Alabama with his wife and daughter described the incident to Salt Lake City reporters.

“We were just passing Shoshone point when suddenly the bandit appeared, stopped our driver and issue an order for the tourists to step out of the vehicle preparatory to holding a big ‘convention,’ over which he evidently intended to act as presiding minister.

“Naturally, we got out.

“Once on the ground, we had to deposit our money in a rude sack which he had furnished for the occasion. He told all of us to put in nothing but money, and if he saw any rings or other jewelry going in, he rudely threw it aside.”

The bandit herded all the passengers to a natural amphitheater and ordered them to sit. Soon, a second coach pulled up behind the first. The highwayman ordered everyone out. When they hesitated, according to Pinkston, the man said, “I bet if you heard a dinner bell ringing you wouldn’t hesitate like that. Now get out. We’re going to hold a calm peaceful convention and I want to enlist your aid.”

The dropping of cash into a sack was repeated, then repeated again when another coach pulled up.

When the fifth coach rumbled up, it presented a special opportunity. Two friends, Miss Estelle Hammond of London, and Miss Alice Cay of Sydney, Australia, were aboard. According to the Salt Lake Telegram the women had been visiting in untamed Australia and had arrived in the genteel United States just a few days before.

“We were never held up in wild Australia,” Miss Cay told the paper, which reported that she smiled about the adventure. She was able to take five photographs of the highwayman for her scrapbook.

Talking about her photographic escapade, Miss Cay said, “I was afraid to try at first. [Some men] said, ‘for heaven’s sake, don’t try it. He’ll shoot you.’ I tried, though, and really, I believe he rather like it. I believe he is, oh, what’s your American word for it, oh, yes, a flirt. I really do

“He was chivalrous to the extreme. He ordered us to be perfectly comfortable and commanded us in threatening tones to make ourselves comfortable, saying that if we didn’t enjoy the procedure, he would blow our bodies into atoms. Oh, it was thrilling.”

For a hold-up story that needed no exaggeration, this one received quite a bit. One report stated that the Yellowstone Highwayman had held up as many as 300 tourists in 40 coaches for a haul of as much as $20,000. The real story was incredible enough. He held up 165 passengers on 15 coaches. The driver of coach number 16 saw what was going on ahead, turned around, and warned the oncoming stages.

The bandit ended up with less than $1,000 in cash, and a little over $100 in jewelry. Apparently, he decided to keep a few of the ladies’ trinkets.

It wasn’t excellent detective work that led to Trafton’s capture. It was a woman. Not the woman who took pictures of him, but a woman he knew well.

A few months after the robbery, when Trafton was back in Rupert, Minnie caught him with another woman. For her revenge, she located the Yellowstone loot that he had hidden in a barn and took it to authorities. After Ed was arrested, Minnie filed for divorce and moved her family to Ogden, Utah. She eventually remarried.

After spending nine months in the Cheyenne jail, Trafton sat for days through a trial that included some 50 witnesses, photographs of him during the robbery, and positive identification of the jewelry found in the barn by those who owned it. It took the jury 30 minutes to reach a guilty verdict. He was sentenced to spend five years at the federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas.

After Trafton was convicted, special agent Melrose, who pops up now and again in this story, told the press that the Yellowstone Bandit had been a suspect in the kidnapping of Alonzo Ernest Empy, which I’ve written about before, and was part of a plot to kidnap Joseph F. Smith, the nephew of the Church of Latter Day Saints founder Joseph Smith, then serving as the sixth president of the church. Trafton wasn’t involved in the Empy kidnapping, as far as we know. Melrose believed that three men were plotting to take Smith, hide him away somewhere in the Jackson Hole area, and hold him for $100,000 in ransom.

After just a few months in prison Trafton wrote a letter to Special Agent Melrose, claiming that he was at death’s door and asking to be moved from Kansas to the prison in Colorado where he had recently resided following the theft of his mother’s money.

“It’s a hard job to put a ‘bull elk,’ who has lived in the open most of his life, into a closet and expect him to ‘make it.’” Trafton wrote to Melrose. “You’ve done your part, as any man with red blood in his veins would do, when he swore allegiance to Uncle Sam. But give me a chance for my life. It’s all I’ve got that’s worthwhile.”

The line about Melrose doing his part referenced the fact that the special agent, whom Trafton had befriended, was the man who escorted him to Cheyenne for trial.

Whether Melrose attempted to honor Trafton’s request is unknown. For the first time in his life, Ed Harrington Trafton served out his entire sentence.

Trafton got out of Leavenworth in 1920. There was nothing for him anymore in Driggs. He thought Hollywood might be interested in his story, so he travelled there in 1922 with that glowing letter about his past exploits from Melrose in his pocket.

That his life ended while he was enjoying an ice cream soda seems every bit as absurd as his claim that he was the model for The Virginian. Trafton’s life story is worthy of a book, but probably not one in which he was the hero.

Early photo of a Yellowstone coach on the left. One the coaches in a museum on the right.

Early photo of a Yellowstone coach on the left. One the coaches in a museum on the right.

Ed Trafton was nearing 60 in 1915, an age when most men would rather settle down and put rustling behind them. He had purchased a farm in Rupert with some of the money he had stolen from his mother. But he wanted at least one more heist before he gave up his guns.

Yellowstone National Park was country he knew well. One thing he knew about it was that in 1915 wealthy tourists who stayed at various establishments in the park toured in relative luxury, riding in spiffed up stages pulled by teams of horses. The practice was for these stages to leave every few minutes on the tour. Spacing them out assured that the well-dressed travelers did not have to endure dust from the stage ahead.

On Wednesday, July 29, 1914, the first stage left Old Faithful Lodge at about 8 am. They rolled along enjoying the scenery until they were about nine miles from the lodge. That’s when a single gunman, his lower face covered by a neckerchief, stepped out in front of the coach holding a gun.

Guns were illegal in the park, so no one in or on the stage had one.

James C. Pinkston, who was visiting Yellowstone from Alabama with his wife and daughter described the incident to Salt Lake City reporters.

“We were just passing Shoshone point when suddenly the bandit appeared, stopped our driver and issue an order for the tourists to step out of the vehicle preparatory to holding a big ‘convention,’ over which he evidently intended to act as presiding minister.

“Naturally, we got out.

“Once on the ground, we had to deposit our money in a rude sack which he had furnished for the occasion. He told all of us to put in nothing but money, and if he saw any rings or other jewelry going in, he rudely threw it aside.”

The bandit herded all the passengers to a natural amphitheater and ordered them to sit. Soon, a second coach pulled up behind the first. The highwayman ordered everyone out. When they hesitated, according to Pinkston, the man said, “I bet if you heard a dinner bell ringing you wouldn’t hesitate like that. Now get out. We’re going to hold a calm peaceful convention and I want to enlist your aid.”

The dropping of cash into a sack was repeated, then repeated again when another coach pulled up.

When the fifth coach rumbled up, it presented a special opportunity. Two friends, Miss Estelle Hammond of London, and Miss Alice Cay of Sydney, Australia, were aboard. According to the Salt Lake Telegram the women had been visiting in untamed Australia and had arrived in the genteel United States just a few days before.

“We were never held up in wild Australia,” Miss Cay told the paper, which reported that she smiled about the adventure. She was able to take five photographs of the highwayman for her scrapbook.

Talking about her photographic escapade, Miss Cay said, “I was afraid to try at first. [Some men] said, ‘for heaven’s sake, don’t try it. He’ll shoot you.’ I tried, though, and really, I believe he rather like it. I believe he is, oh, what’s your American word for it, oh, yes, a flirt. I really do

“He was chivalrous to the extreme. He ordered us to be perfectly comfortable and commanded us in threatening tones to make ourselves comfortable, saying that if we didn’t enjoy the procedure, he would blow our bodies into atoms. Oh, it was thrilling.”

For a hold-up story that needed no exaggeration, this one received quite a bit. One report stated that the Yellowstone Highwayman had held up as many as 300 tourists in 40 coaches for a haul of as much as $20,000. The real story was incredible enough. He held up 165 passengers on 15 coaches. The driver of coach number 16 saw what was going on ahead, turned around, and warned the oncoming stages.

The bandit ended up with less than $1,000 in cash, and a little over $100 in jewelry. Apparently, he decided to keep a few of the ladies’ trinkets.

It wasn’t excellent detective work that led to Trafton’s capture. It was a woman. Not the woman who took pictures of him, but a woman he knew well.

A few months after the robbery, when Trafton was back in Rupert, Minnie caught him with another woman. For her revenge, she located the Yellowstone loot that he had hidden in a barn and took it to authorities. After Ed was arrested, Minnie filed for divorce and moved her family to Ogden, Utah. She eventually remarried.

After spending nine months in the Cheyenne jail, Trafton sat for days through a trial that included some 50 witnesses, photographs of him during the robbery, and positive identification of the jewelry found in the barn by those who owned it. It took the jury 30 minutes to reach a guilty verdict. He was sentenced to spend five years at the federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas.

After Trafton was convicted, special agent Melrose, who pops up now and again in this story, told the press that the Yellowstone Bandit had been a suspect in the kidnapping of Alonzo Ernest Empy, which I’ve written about before, and was part of a plot to kidnap Joseph F. Smith, the nephew of the Church of Latter Day Saints founder Joseph Smith, then serving as the sixth president of the church. Trafton wasn’t involved in the Empy kidnapping, as far as we know. Melrose believed that three men were plotting to take Smith, hide him away somewhere in the Jackson Hole area, and hold him for $100,000 in ransom.

After just a few months in prison Trafton wrote a letter to Special Agent Melrose, claiming that he was at death’s door and asking to be moved from Kansas to the prison in Colorado where he had recently resided following the theft of his mother’s money.

“It’s a hard job to put a ‘bull elk,’ who has lived in the open most of his life, into a closet and expect him to ‘make it.’” Trafton wrote to Melrose. “You’ve done your part, as any man with red blood in his veins would do, when he swore allegiance to Uncle Sam. But give me a chance for my life. It’s all I’ve got that’s worthwhile.”

The line about Melrose doing his part referenced the fact that the special agent, whom Trafton had befriended, was the man who escorted him to Cheyenne for trial.

Whether Melrose attempted to honor Trafton’s request is unknown. For the first time in his life, Ed Harrington Trafton served out his entire sentence.

Trafton got out of Leavenworth in 1920. There was nothing for him anymore in Driggs. He thought Hollywood might be interested in his story, so he travelled there in 1922 with that glowing letter about his past exploits from Melrose in his pocket.

That his life ended while he was enjoying an ice cream soda seems every bit as absurd as his claim that he was the model for The Virginian. Trafton’s life story is worthy of a book, but probably not one in which he was the hero.

Early photo of a Yellowstone coach on the left. One the coaches in a museum on the right.

Early photo of a Yellowstone coach on the left. One the coaches in a museum on the right.

Published on November 06, 2022 04:00

November 5, 2022

A Legendary Highwayman, Part 4 of 5 (Tap to read)

Yesterday we left Ed and Minnie Trafton when they were Teton Valley entrepreneurs, shearing and dipping ship, running a boarding house and saloon, and possibly expediting the transfer of livestock from one hapless owner to another without benefit of paperwork.

The sideline rustling business, for which Ed had already served a couple of sentences in the Idaho State Penitentiary, was starting to bring a little heat onto the Traftons. Some ranchers looked upon their herd shrinkage as an annoyance and part of the cost of doing business. But a couple of the cattlemen had begun to plot to catch Ed in the act.

It may have been good luck for Ed that his mother asked for his help in 1909, providing a good excuse to leave Teton Valley and let things cool down.

Annie Knight was the same mother from whom Ed had stolen money, a ham, and a horse for his grubstake in a failed attempt to get rich mining for gold in the Black Hills many years earlier. She was the same mother who allegedly bribed officials to get him out of prison.

Trafton’s forgiving mother asked he and Minnie to move to Denver to help her with her boarding house. Her husband, Ed’s stepfather, James Knight, was in poor health.

It was while running the Denver boarding house that Ed met Special Agent James Melrose, the U.S. Justice Department official who would one day write the glowing letter of reference that was found on Trafton when he died.

Melrose was fascinated by Trafton’s stories of the wild West. He learned that, according Trafton, Ed was the inspiration for Owen Wister’s lead character in The Virginian. He heard tales of gunfights and cattle drives and narrow escapes. Melrose ate it up. To be fair, Trafton probably gave short shrift to his rustling exploits, if he mentioned them at all.

The special agent was so gullible, he probably didn’t even notice that Trafton was having an affair with Melrose’s wife in his spare time.

But all good things must end. In early 1910, James Knight passed away, leaving his wife Annie to collect on a $10,000 insurance policy.

Not trusting banks, Annie buried the money. Her loving son spent some time looking for it, to no avail. Eventually, Annie decided to trust a bank and to trust Ed Trafton to deposit the money.

Stand by for a big shock. Ed did not deposit the money. Writer Wayne Moss interviewed a grandson of Trafton’s to get family details for a story that ran in the Teton Valley Times in 2015. As Moss related it, Ed buried $4,000 in his own hiding spot in the backyard, hid $3,000 in a dresser drawer, intending it as a gift for his wife, and secreted away the remaining $3,000 under some floorboards.

Ed told his mother he had been robbed. No wait, that wasn’t it, he’d forgotten the money in a satchel he left on a trolly.

Annie Knight was not swayed by either story. She called the police, and they quickly found the $3,000 in Minnie’s drawer. Lickety split Ed and Minnie were behind bars.

Ed was convicted and sentenced to from 5 to 8 years in prison. Minnie, who protested her innocence, was convicted and sentenced to from 3 to 5 years. They would both reside in the Colorado State Penitentiary for the next couple of years.

The Trafton’s eldest daughter, Anna—probably lovingly named after the woman Ed stole $10,000 from—removed the $3,000 from beneath the floorboards and took her siblings to Pocatello to live. Minnie would join them upon her release in 1912. They opened a boarding house there.

Ed, who had a way of getting reduced sentences, was released in 1913. He dug up the remaining $4,000, collected his wife in Pocatello, and moved to Rupert where he was purchased a farm. (Note that some accounts say he worked on a Rupert farm, but did not own it)

Nearing 60, his thieving days were over.

Just kidding. Come back tomorrow for the final chapter in the story of Ed Trafton.

[image error] Ed Harington Trafton's Idaho State Penitentiary booking photo.

The sideline rustling business, for which Ed had already served a couple of sentences in the Idaho State Penitentiary, was starting to bring a little heat onto the Traftons. Some ranchers looked upon their herd shrinkage as an annoyance and part of the cost of doing business. But a couple of the cattlemen had begun to plot to catch Ed in the act.

It may have been good luck for Ed that his mother asked for his help in 1909, providing a good excuse to leave Teton Valley and let things cool down.

Annie Knight was the same mother from whom Ed had stolen money, a ham, and a horse for his grubstake in a failed attempt to get rich mining for gold in the Black Hills many years earlier. She was the same mother who allegedly bribed officials to get him out of prison.

Trafton’s forgiving mother asked he and Minnie to move to Denver to help her with her boarding house. Her husband, Ed’s stepfather, James Knight, was in poor health.

It was while running the Denver boarding house that Ed met Special Agent James Melrose, the U.S. Justice Department official who would one day write the glowing letter of reference that was found on Trafton when he died.

Melrose was fascinated by Trafton’s stories of the wild West. He learned that, according Trafton, Ed was the inspiration for Owen Wister’s lead character in The Virginian. He heard tales of gunfights and cattle drives and narrow escapes. Melrose ate it up. To be fair, Trafton probably gave short shrift to his rustling exploits, if he mentioned them at all.

The special agent was so gullible, he probably didn’t even notice that Trafton was having an affair with Melrose’s wife in his spare time.

But all good things must end. In early 1910, James Knight passed away, leaving his wife Annie to collect on a $10,000 insurance policy.

Not trusting banks, Annie buried the money. Her loving son spent some time looking for it, to no avail. Eventually, Annie decided to trust a bank and to trust Ed Trafton to deposit the money.

Stand by for a big shock. Ed did not deposit the money. Writer Wayne Moss interviewed a grandson of Trafton’s to get family details for a story that ran in the Teton Valley Times in 2015. As Moss related it, Ed buried $4,000 in his own hiding spot in the backyard, hid $3,000 in a dresser drawer, intending it as a gift for his wife, and secreted away the remaining $3,000 under some floorboards.

Ed told his mother he had been robbed. No wait, that wasn’t it, he’d forgotten the money in a satchel he left on a trolly.

Annie Knight was not swayed by either story. She called the police, and they quickly found the $3,000 in Minnie’s drawer. Lickety split Ed and Minnie were behind bars.

Ed was convicted and sentenced to from 5 to 8 years in prison. Minnie, who protested her innocence, was convicted and sentenced to from 3 to 5 years. They would both reside in the Colorado State Penitentiary for the next couple of years.

The Trafton’s eldest daughter, Anna—probably lovingly named after the woman Ed stole $10,000 from—removed the $3,000 from beneath the floorboards and took her siblings to Pocatello to live. Minnie would join them upon her release in 1912. They opened a boarding house there.

Ed, who had a way of getting reduced sentences, was released in 1913. He dug up the remaining $4,000, collected his wife in Pocatello, and moved to Rupert where he was purchased a farm. (Note that some accounts say he worked on a Rupert farm, but did not own it)

Nearing 60, his thieving days were over.

Just kidding. Come back tomorrow for the final chapter in the story of Ed Trafton.

[image error] Ed Harington Trafton's Idaho State Penitentiary booking photo.

Published on November 05, 2022 04:00

November 4, 2022

A Legendary Highwayman, Part, 3 of 5 (Tap to read)

As I wrote in previous posts, Ed Harrington Trafton was an outlaw and entrepreneur.

His escapades as the former were often ignored by locals while his business side was praised.

Trafton received a pardon from his 25-year sentence for horse stealing, serving just two. He got out of prison in 1889 and returned to the Teton Valley.

It wasn’t long until Ed found, inexplicably, that he had a surplus of horses that he needed to get rid of. He herded them to Hyrum, Utah where the locals wouldn’t recognize the altered brands. There he met 18-year-old Minnie Lyman. Ed, now 34, proposed to the daughter of the gentleman who was buying the horses.

The newlyweds moved to Colter Bay on Jackson Lake and set up their new home. Some sources say their main business there was working with rustlers to move stolen horses and cattle. It was at the place on Jackson Lake where Owen Wister, author of The Virginian, may have spent some time with Trafton.

After a few years at Jackson Lake, the Traftons moved back to the Teton Valley where their five children, four girls and a boy, were born.

In 1899, Ed Trafton was arrested for dynamiting the Brandon Building in St Anthony, which was under construction, allegedly acting as a hired bomber. The bomb broke windows nearby and damaged a lawyer’s office but did little damage to the stone structure that was the apparent target. Trafton, if he was the incompetent bomber, was acquitted of those charges.

1901 was a memorable year for the Traftons. In February, the family was startled by a bullet smashing through the window of their home and grazing Minnie. How could anyone have a beef with such a nice family?

Later that year, Trafton was caught rustling beef, again, and was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. He got out in two and returned to the Teton Valley where he seemed to focus more on his business side for a few years, including the boarding house and restaurant.

Trafton’s sheep shearing business was one of large scale. In 1904 he told the Teton Peak newspaper in St. Anthony that he expected to shear 125,000 sheep and noted that dipping vats would also be available.

Exciting as sheep dipping is, we’re going to leave the tale there for a day. Come back tomorrow when we get to the stories that made the sheep dipper famous.

[image error]

His escapades as the former were often ignored by locals while his business side was praised.

Trafton received a pardon from his 25-year sentence for horse stealing, serving just two. He got out of prison in 1889 and returned to the Teton Valley.

It wasn’t long until Ed found, inexplicably, that he had a surplus of horses that he needed to get rid of. He herded them to Hyrum, Utah where the locals wouldn’t recognize the altered brands. There he met 18-year-old Minnie Lyman. Ed, now 34, proposed to the daughter of the gentleman who was buying the horses.

The newlyweds moved to Colter Bay on Jackson Lake and set up their new home. Some sources say their main business there was working with rustlers to move stolen horses and cattle. It was at the place on Jackson Lake where Owen Wister, author of The Virginian, may have spent some time with Trafton.

After a few years at Jackson Lake, the Traftons moved back to the Teton Valley where their five children, four girls and a boy, were born.

In 1899, Ed Trafton was arrested for dynamiting the Brandon Building in St Anthony, which was under construction, allegedly acting as a hired bomber. The bomb broke windows nearby and damaged a lawyer’s office but did little damage to the stone structure that was the apparent target. Trafton, if he was the incompetent bomber, was acquitted of those charges.

1901 was a memorable year for the Traftons. In February, the family was startled by a bullet smashing through the window of their home and grazing Minnie. How could anyone have a beef with such a nice family?

Later that year, Trafton was caught rustling beef, again, and was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. He got out in two and returned to the Teton Valley where he seemed to focus more on his business side for a few years, including the boarding house and restaurant.

Trafton’s sheep shearing business was one of large scale. In 1904 he told the Teton Peak newspaper in St. Anthony that he expected to shear 125,000 sheep and noted that dipping vats would also be available.

Exciting as sheep dipping is, we’re going to leave the tale there for a day. Come back tomorrow when we get to the stories that made the sheep dipper famous.

[image error]

Published on November 04, 2022 04:00

November 3, 2022

A Legendary Highwayman, Part 2 of 5 (Tap to read)

Yesterday we started the story of Edwin B. Trafton with an account of his death and how his life was the possible inspiration for the novel The Virginian, by Owen Wister. Today we’ll look at the high and low points of that life. Mostly the low.

Born in New Brunswick, Canada in 1857 to immigrants from Liverpool, Edwin Burnham Trafton seemed bent on outlawry from an early age. A few years after his father’s death and his mother Annie’s marriage to a neighbor, James Knight, Ed found himself in Denver, a juvenile delinquent who had a habit of appropriating guns from the residents of his mother’s boarding house.

At around age 20 Ed decided to set out on his own. He left Annie Knight a note, stole $40, a smoked ham, and her best horse, and took off for the Black Hills in search of gold.

His taste for gold never left him, but mining it was not his preferred method of acquisition.

After striking out in the Black Hills gold rush, Trafton settled in the Teton Valley near present day Driggs in 1878. The following year he homesteaded in the valley along Milk Creek and started a variety of endeavors, including sheep shearing, and eventually operating a small store that included a saloon and boarding house.

Ed Trafton lived parallel lives. He ran his legitimate businesses while at the same time robbing other businesses and stealing livestock. This seemed to be widely known and widely tolerated.

Arrested for horse stealing in 1887, Ed was sent to the jail in Blackfoot to await trial along with his alleged partner in the crime, Lem Nickerson. The theft had occurred in the Teton Valley, but Blackfoot was the county seat of a much larger Bingham county at that time. Ed was going by the name Harrington then, but I will continue to call him Trafton to help readers through a confusing story.

Nickerson’s wife was visiting regularly in the weeks before the trial. She got to be such a regular visitor that the guards let down their, well, guard. She slipped a long six-shooter into the pocket of her spouse during visitation.

Soon after noon on June 22, 1887, the leisurely escape began. Guard William High looked down the hall to the jail and saw that he was also looking down the barrel of a 45. Nickerson demanded that the guard “throw up your hands and deliver me the keys to this jail or down and out you go.”

Trafton and Nickerson overpowered another deputy on duty and locked the two officers in a cell. The accused horse thieves poked around the county offices and found three other men to lock away.

Then it was time for Ed Harrington Trafton to pen a little note to Judge Hayes, who he was scheduled to appear before: “We are off for the hills and the mountains which we love so dearly. We are familiar with the mountain trails and the officers cannot catch us, for we are well mounted and well armed. You cannot get a crack at me this time and when I meet you again it will be in hell.”

Perhaps while Trafton was working on that note, Nickerson strolled from the courthouse to where his family was staying in Blackfoot to retrieve some horses stashed there by his brother, bringing them back to the jail.

It was nearing dusk by the time the men were ready to make their escape.

A Pocatello man named Hughes, accused of murder, was also locked up in the jail. Nickerson and Trafton freed him, perhaps to provide an additional diversion to pursuers. Hughes was a black man. He was aware that Indians often sympathized with dark-skinned people who were in trouble with white men, so he made his way to a scattering of tepees south of town. To his delight, the Indians did take him in, putting ocher on his face and giving him native clothes to wear. He hung around Blackfoot in that disguise for a few days before hopping a train to Montana.

While Hughes was making friends with the Indians, the other escapees made their way to Willow Creek in the Blackfoot Mountains where they looked up an old acquaintance, Johnnie Heath. They had a leisurely breakfast with him the next day, then headed out. Trafton and Nickerson made their way for several days through the Wolverine country, and eventually headed north, planning to cross the Snake River near present day Heise Hot Springs. High water made the crossing too dangerous. With a posse now in hot pursuit, Trafton and Nickerson took refuge in the willows on Pool Island.

Law enforcement officials from several towns came together to smoke out the escapees. A several days siege ensued, the result of which was that Trafton was shot in the foot and both men surrendered.

Their fellow escapee, Hughes, was recognized in Butte, Montana and brought back to Blackfoot to face execution days later.

It’s likely that Ed Harrington Trafton regretted his snarky note to Judge Hayes. “Well, Mr. Harrington,” the judge said, “we have met again—but not in hell!” He then sentenced Harrington/Trafton to 25 years at hard labor in the Idaho State Penitentiary.

Warden C.E. Arney, who took Trafton in at the penitentiary related a story years later that may shed some light on how the man led his parallel lives of businessman and outlaw. “Harrington was a clever fellow and aside from his outlaw traits was a pleasant companion, interesting and truthful. These traits elicited sympathy for him, and petitions soon circulated for his release. In 1888 I saw [him] in the penitentiary and in 1891 when I was running a newspaper in Rexburg, he was pardoned and I saw him in the wild pose of a cowboy, once more breathing the free mountain air, and astride a well gaited cayuse, ride down the streets of Rexburg wildly waving his broad brimmed hat at the friends who greeted him from the streets and store buildings, stopping only long enough to shake hands with those who had befriended him and then hurrying on to his old haunts in the Teton Basin and Jackson Hole Districts.”

Trafton had gotten out in two years, perhaps with the help of his mother who may have bribed someone. If so, she would come to regret that.

Tomorrow I’ll continue the story of the outlaw/entrepreneur.

An early photo of the original Bingham County Courthouse.

An early photo of the original Bingham County Courthouse.

Born in New Brunswick, Canada in 1857 to immigrants from Liverpool, Edwin Burnham Trafton seemed bent on outlawry from an early age. A few years after his father’s death and his mother Annie’s marriage to a neighbor, James Knight, Ed found himself in Denver, a juvenile delinquent who had a habit of appropriating guns from the residents of his mother’s boarding house.

At around age 20 Ed decided to set out on his own. He left Annie Knight a note, stole $40, a smoked ham, and her best horse, and took off for the Black Hills in search of gold.

His taste for gold never left him, but mining it was not his preferred method of acquisition.

After striking out in the Black Hills gold rush, Trafton settled in the Teton Valley near present day Driggs in 1878. The following year he homesteaded in the valley along Milk Creek and started a variety of endeavors, including sheep shearing, and eventually operating a small store that included a saloon and boarding house.

Ed Trafton lived parallel lives. He ran his legitimate businesses while at the same time robbing other businesses and stealing livestock. This seemed to be widely known and widely tolerated.

Arrested for horse stealing in 1887, Ed was sent to the jail in Blackfoot to await trial along with his alleged partner in the crime, Lem Nickerson. The theft had occurred in the Teton Valley, but Blackfoot was the county seat of a much larger Bingham county at that time. Ed was going by the name Harrington then, but I will continue to call him Trafton to help readers through a confusing story.

Nickerson’s wife was visiting regularly in the weeks before the trial. She got to be such a regular visitor that the guards let down their, well, guard. She slipped a long six-shooter into the pocket of her spouse during visitation.

Soon after noon on June 22, 1887, the leisurely escape began. Guard William High looked down the hall to the jail and saw that he was also looking down the barrel of a 45. Nickerson demanded that the guard “throw up your hands and deliver me the keys to this jail or down and out you go.”

Trafton and Nickerson overpowered another deputy on duty and locked the two officers in a cell. The accused horse thieves poked around the county offices and found three other men to lock away.

Then it was time for Ed Harrington Trafton to pen a little note to Judge Hayes, who he was scheduled to appear before: “We are off for the hills and the mountains which we love so dearly. We are familiar with the mountain trails and the officers cannot catch us, for we are well mounted and well armed. You cannot get a crack at me this time and when I meet you again it will be in hell.”

Perhaps while Trafton was working on that note, Nickerson strolled from the courthouse to where his family was staying in Blackfoot to retrieve some horses stashed there by his brother, bringing them back to the jail.

It was nearing dusk by the time the men were ready to make their escape.

A Pocatello man named Hughes, accused of murder, was also locked up in the jail. Nickerson and Trafton freed him, perhaps to provide an additional diversion to pursuers. Hughes was a black man. He was aware that Indians often sympathized with dark-skinned people who were in trouble with white men, so he made his way to a scattering of tepees south of town. To his delight, the Indians did take him in, putting ocher on his face and giving him native clothes to wear. He hung around Blackfoot in that disguise for a few days before hopping a train to Montana.

While Hughes was making friends with the Indians, the other escapees made their way to Willow Creek in the Blackfoot Mountains where they looked up an old acquaintance, Johnnie Heath. They had a leisurely breakfast with him the next day, then headed out. Trafton and Nickerson made their way for several days through the Wolverine country, and eventually headed north, planning to cross the Snake River near present day Heise Hot Springs. High water made the crossing too dangerous. With a posse now in hot pursuit, Trafton and Nickerson took refuge in the willows on Pool Island.

Law enforcement officials from several towns came together to smoke out the escapees. A several days siege ensued, the result of which was that Trafton was shot in the foot and both men surrendered.

Their fellow escapee, Hughes, was recognized in Butte, Montana and brought back to Blackfoot to face execution days later.

It’s likely that Ed Harrington Trafton regretted his snarky note to Judge Hayes. “Well, Mr. Harrington,” the judge said, “we have met again—but not in hell!” He then sentenced Harrington/Trafton to 25 years at hard labor in the Idaho State Penitentiary.

Warden C.E. Arney, who took Trafton in at the penitentiary related a story years later that may shed some light on how the man led his parallel lives of businessman and outlaw. “Harrington was a clever fellow and aside from his outlaw traits was a pleasant companion, interesting and truthful. These traits elicited sympathy for him, and petitions soon circulated for his release. In 1888 I saw [him] in the penitentiary and in 1891 when I was running a newspaper in Rexburg, he was pardoned and I saw him in the wild pose of a cowboy, once more breathing the free mountain air, and astride a well gaited cayuse, ride down the streets of Rexburg wildly waving his broad brimmed hat at the friends who greeted him from the streets and store buildings, stopping only long enough to shake hands with those who had befriended him and then hurrying on to his old haunts in the Teton Basin and Jackson Hole Districts.”

Trafton had gotten out in two years, perhaps with the help of his mother who may have bribed someone. If so, she would come to regret that.

Tomorrow I’ll continue the story of the outlaw/entrepreneur.

An early photo of the original Bingham County Courthouse.

An early photo of the original Bingham County Courthouse.

Published on November 03, 2022 04:00

November 2, 2022

A Legendary Highwayman, Part 1 of 5 (Tap to read)

Starting at the beginning is so conventional in storytelling. In recognition of the irregular nature of this tale’s subject, I’m going to start at the end. On top of that, I’m going to start with something that doesn’t even seem to relate to the subject.

I always thought it odd that the book many scholars consider the first Western novel was called The Virginian. It is set in Wyoming where the lead character, who was born in Virginia, works as a cowboy. He is never referred to by name, only as The Virginian.

The author, at first glance, seems like an odd one to have invented the genre. Owen Wister was born in Philadelphia, attended schools in Britain and Switzerland, and ultimately graduated from Harvard, where he was a Hasty Pudding member. He studied music for a couple of years in a Paris conservatory before turning to the law, and eventually to writing.

Wister became friends with Teddy Roosevelt and, like Roosevelt, spent many summers in the West, mostly in Wyoming.

The Virginian was a monster hit, reprinted fourteen times in 1902, the year it came out. It remains one of the 50 top-selling works of fiction.

So, the author was from Philadelphia, the book was set in Wyoming, where they named a mountain after Wister, and this is a blog about Idaho history. What’s the connection?

Possibly none. However, one-time Idaho State Penitentiary Warden C.E. Arney insisted that Ed Harrington Trafton, one-time inmate of his prison, was the man Wister used as his model for the hero in Wister’s story. That according to an article in the Idaho Statesman of September 17, 1922.

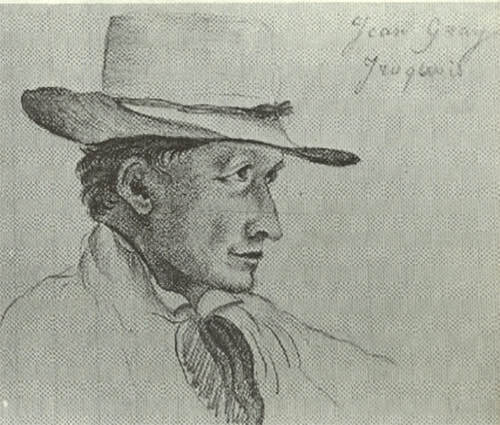

It wasn’t just the Statesman making this claim. On August 16, 1922, the Los Angeles Times ran a story with the stacked headline:

“THE VIRGINIAN”

DIES SUDDENLY

---

Owen Wister Novel Hero

Was Real Pioneer

---

Blazed First Trails Into

Jackson Hole Country

---

Ed Trafton Whacked Bulls

With Buffalo Bill

As proof of the connection, the Times offered a letter of introduction found on Trafton and written by James W. Melrose, who was a special agent in the Department of Justice for 16 years in Denver.

“This will introduce Edwin B. Trafton,” the letter states, “better known as ‘Ed Harrington.’”

“Mr. Trafton is the man from whom Owen Wister modeled the character, The Virginian, in his famous story of that name.”

Melrose went on to laud Trafton/Harrington as a well-known guide for 35 years in the Yellowstone country and a prolific big game hunter. According to the letter he built the first log cabin and blazed the first trails there in 1880. Harrington, Melrose said, was one of the first into the Black Hills for the gold rush there in 1875. He “whacked bulls out of old Cheyenne with the celebrated Buffalo Bill Cody.”

Perhaps the most important detail on his resume, as far as the Virginian connection goes, was that “He fought a duel with the original ‘Trampas,’ better known as Black Tex, who had given Ed until sundown to leave camp.”

Trampas was the name of the villain in The Virginian.

Left out of the Melrose letter were the multiple arrests of Trafton/Harrington, his history as a highwayman, and that time he stole $10,000 from his mother.

Did the author use Trafton/Harrington as the model for one of his characters? Given the man’s shady side, maybe he was the model for Trampas, the bad guy. Trampas and Trafton are a bit similar.

Wister himself never said that the Virginian was modeled after any single person.

The Times noted that, “The man whose adventurous life inspired Owen Wister to write The Virginian, one of the most popular stories of the pioneer West, dropped dead at Second Street and Broadway late yesterday afternoon while drinking an ice cream soda.” The cause of death was listed as apoplexy. He was 64 or 65 and is buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California.

And thus, with Trafton’s end, we begin his story. It will continue with tomorrow’s post.

I always thought it odd that the book many scholars consider the first Western novel was called The Virginian. It is set in Wyoming where the lead character, who was born in Virginia, works as a cowboy. He is never referred to by name, only as The Virginian.

The author, at first glance, seems like an odd one to have invented the genre. Owen Wister was born in Philadelphia, attended schools in Britain and Switzerland, and ultimately graduated from Harvard, where he was a Hasty Pudding member. He studied music for a couple of years in a Paris conservatory before turning to the law, and eventually to writing.

Wister became friends with Teddy Roosevelt and, like Roosevelt, spent many summers in the West, mostly in Wyoming.

The Virginian was a monster hit, reprinted fourteen times in 1902, the year it came out. It remains one of the 50 top-selling works of fiction.

So, the author was from Philadelphia, the book was set in Wyoming, where they named a mountain after Wister, and this is a blog about Idaho history. What’s the connection?

Possibly none. However, one-time Idaho State Penitentiary Warden C.E. Arney insisted that Ed Harrington Trafton, one-time inmate of his prison, was the man Wister used as his model for the hero in Wister’s story. That according to an article in the Idaho Statesman of September 17, 1922.

It wasn’t just the Statesman making this claim. On August 16, 1922, the Los Angeles Times ran a story with the stacked headline:

“THE VIRGINIAN”

DIES SUDDENLY

---

Owen Wister Novel Hero

Was Real Pioneer

---

Blazed First Trails Into

Jackson Hole Country

---

Ed Trafton Whacked Bulls

With Buffalo Bill

As proof of the connection, the Times offered a letter of introduction found on Trafton and written by James W. Melrose, who was a special agent in the Department of Justice for 16 years in Denver.

“This will introduce Edwin B. Trafton,” the letter states, “better known as ‘Ed Harrington.’”

“Mr. Trafton is the man from whom Owen Wister modeled the character, The Virginian, in his famous story of that name.”

Melrose went on to laud Trafton/Harrington as a well-known guide for 35 years in the Yellowstone country and a prolific big game hunter. According to the letter he built the first log cabin and blazed the first trails there in 1880. Harrington, Melrose said, was one of the first into the Black Hills for the gold rush there in 1875. He “whacked bulls out of old Cheyenne with the celebrated Buffalo Bill Cody.”

Perhaps the most important detail on his resume, as far as the Virginian connection goes, was that “He fought a duel with the original ‘Trampas,’ better known as Black Tex, who had given Ed until sundown to leave camp.”

Trampas was the name of the villain in The Virginian.

Left out of the Melrose letter were the multiple arrests of Trafton/Harrington, his history as a highwayman, and that time he stole $10,000 from his mother.

Did the author use Trafton/Harrington as the model for one of his characters? Given the man’s shady side, maybe he was the model for Trampas, the bad guy. Trampas and Trafton are a bit similar.

Wister himself never said that the Virginian was modeled after any single person.

The Times noted that, “The man whose adventurous life inspired Owen Wister to write The Virginian, one of the most popular stories of the pioneer West, dropped dead at Second Street and Broadway late yesterday afternoon while drinking an ice cream soda.” The cause of death was listed as apoplexy. He was 64 or 65 and is buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California.

And thus, with Trafton’s end, we begin his story. It will continue with tomorrow’s post.

Published on November 02, 2022 04:00

November 1, 2022

A WWI Casualty--in Weiser (Tap to read)

It’s September 30, 1918. A young man from Kentucky is shot in the abdomen, later dying of his wounds. His draft registration listed John T. Chesnut as a sheepherder working for Hallstrom and Company in Midvale, Idaho.

Just another casualty of World War I?

In a way, perhaps. Chesnut was watching the Wild West parade in Weiser when mounted cavalry members came trotting by, not in formation, but in a skirmish with an invisible enemy. Their ammunition, appropriate for invisible enemies, was blank. Except for that one round.

Harley McCullough fired at Chesnut, striking him in the stomach. The 28-year-old went down. The parade stopped. Chesnut died.

McCullough was described by the Payette Enterprise as “about twenty years of age and well-known in Payette, …a respectable young man (who) is much grieved over the sad accident.”

The shooter was arrested but released on bail. Charges were likely dropped. I found no evidence of his incarceration.

Chesnut’s hometown paper, the London Sentinel, London, Kentucky, made the leap that it was a military demonstration gone wrong during wartime. I think it’s more likely that the “cavalry” were parade participants dressed up as cavalry members from days gone by. Nevertheless, a tragic accident. Chesnut’s headstone in the Rough Creek Cemetery, Brock, Laurel County, Kentucky. Photo courtesy of Find A Grave.

Chesnut’s headstone in the Rough Creek Cemetery, Brock, Laurel County, Kentucky. Photo courtesy of Find A Grave.

Just another casualty of World War I?

In a way, perhaps. Chesnut was watching the Wild West parade in Weiser when mounted cavalry members came trotting by, not in formation, but in a skirmish with an invisible enemy. Their ammunition, appropriate for invisible enemies, was blank. Except for that one round.

Harley McCullough fired at Chesnut, striking him in the stomach. The 28-year-old went down. The parade stopped. Chesnut died.

McCullough was described by the Payette Enterprise as “about twenty years of age and well-known in Payette, …a respectable young man (who) is much grieved over the sad accident.”

The shooter was arrested but released on bail. Charges were likely dropped. I found no evidence of his incarceration.

Chesnut’s hometown paper, the London Sentinel, London, Kentucky, made the leap that it was a military demonstration gone wrong during wartime. I think it’s more likely that the “cavalry” were parade participants dressed up as cavalry members from days gone by. Nevertheless, a tragic accident.

Chesnut’s headstone in the Rough Creek Cemetery, Brock, Laurel County, Kentucky. Photo courtesy of Find A Grave.

Chesnut’s headstone in the Rough Creek Cemetery, Brock, Laurel County, Kentucky. Photo courtesy of Find A Grave.

Published on November 01, 2022 04:00

October 31, 2022

A Ghost Story for Halloween (Tap to read)

One can rarely prove or disprove a ghost story. Such is not the case of the Ghost Flutist (or flautist if you prefer) of Sun Valley.

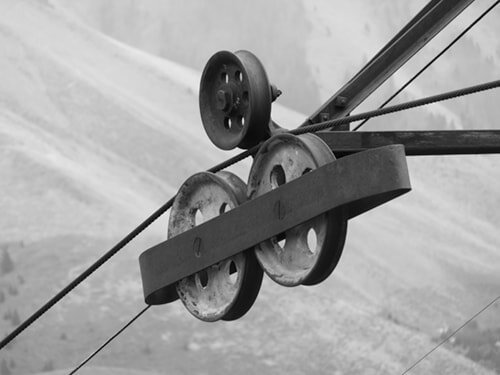

In December 1936, Margaret E. Wood took a job as a housekeeper at the Sun Valley Lodge. She had transferred from the Mount Washington Hotel in New Hampshire. For some reason, she seemed a little hesitant to explore her new surroundings. Associates at the lodge persuaded her to get out and enjoy the beautiful scenery and take the Proctor Mountain Tramway to the top.

The housekeeper was enjoying the ride in the fresh air when about halfway up she heard a flute playing in the distance. Why would anyone be playing a flute somewhere out there in the snow? Wouldn’t their bottom lip freeze to the instrument?

She heard the music all the way to the top and heard it again on the way back down.

Curious, Miss Wood asked around. No one knew of any lonely shepherd soothing his flock with a flute or, for that matter, a teenager told to practice that dang thing outside. She happened to tell the story to Charles Williams, who worked as a bridge inspector for Union Pacific. His reaction was one of relief.

“Did you really hear it?” Williams said. “That’s great. I was afraid I was the only one. It’s been worrying me for days.”

Miss Wood and Mr. Williams took a little trek to the tram in search of the answer. Williams had installed the lift, so he was particularly interested.

Together, they found the ghost flutist. A pipe that connected one chair to the cable had some holes in it. As the lift traveled up the mountain, the breezes it encountered blew a haunting melody through those holes. Another good ghost story dashed by physics.

In December 1936, Margaret E. Wood took a job as a housekeeper at the Sun Valley Lodge. She had transferred from the Mount Washington Hotel in New Hampshire. For some reason, she seemed a little hesitant to explore her new surroundings. Associates at the lodge persuaded her to get out and enjoy the beautiful scenery and take the Proctor Mountain Tramway to the top.

The housekeeper was enjoying the ride in the fresh air when about halfway up she heard a flute playing in the distance. Why would anyone be playing a flute somewhere out there in the snow? Wouldn’t their bottom lip freeze to the instrument?

She heard the music all the way to the top and heard it again on the way back down.

Curious, Miss Wood asked around. No one knew of any lonely shepherd soothing his flock with a flute or, for that matter, a teenager told to practice that dang thing outside. She happened to tell the story to Charles Williams, who worked as a bridge inspector for Union Pacific. His reaction was one of relief.

“Did you really hear it?” Williams said. “That’s great. I was afraid I was the only one. It’s been worrying me for days.”

Miss Wood and Mr. Williams took a little trek to the tram in search of the answer. Williams had installed the lift, so he was particularly interested.

Together, they found the ghost flutist. A pipe that connected one chair to the cable had some holes in it. As the lift traveled up the mountain, the breezes it encountered blew a haunting melody through those holes. Another good ghost story dashed by physics.

Published on October 31, 2022 04:00

October 30, 2022

Three Island Crossing (Tap to read)

Three Island Crossing was a terror for Oregon Trail pioneers. The ford at the Snake River near the present-day town of Glenns Ferry was one of the most feared parts of the journey. The river, some 200 yards wide, was deceptively placid looking. The current was relentless. About half those traveling the Oregon Trail risked a crossing there. Half chose to stay on the south side of the river where the trail was worse and longer but the chance of losing everything to the river did not loom.

Narcissa Whitman, one of four missionaries on their way to historic and tragic roles in history, wrote this about the crossing in August of 1836: "We have come fifteen miles and have had the worst route in all the journey for the cart. We might have had a better one but for being misled by some of the company who started out before the leaders.

“It was two o'clock before we came into camp. They were preparing to cross Snake River. The river is divided by two islands into three branches, and is fordable. The packs are placed upon the tops of the highest horses and in this way we crossed without wetting. Two of the tallest horses were selected to carry Mrs. Spalding and myself over. Mr. McLeod gave me his and rode mine. The last branch we rode as much as half a mile in crossing and against the current too, which made it hard for the horses, the water being up to their sides. Husband had considerable difficulty crossing the cart. Both cart and mules were turned upside down in the river and entangled in the harness. The mules would have been drowned but for a desperate struggle to get them ashore. Then after putting two of the strongest horses before the cart, and two men swimming behind to steady it, they succeeded in getting it across.

“I once thought that crossing streams would be the most dreaded part of the journey. I can now cross the most difficult stream without the least fear. There is one manner of crossing which husband has tried but I have not, neither do I wish to. Take an elk skin and stretch it over you, spreading yourself out as much as possible, then let the Indian women carefully put you on the water and with a cord in the mouth they will swim and draw you over. Edward, how do you think you would like to travel in this way?"

John C. Fremont told of another crossing in 1842: “About two o’clock we had arrived at the ford where the road crosses to the right bank of the Snake River. An Indian was hired to conduct us through the ford, which proved impracticable for us, the water sweeping away the howitzer and nearly drowning the mules, which we were able to extricate by cutting them out of the harness. The river is expanded into a little bay, in which there are two islands, across which is the road of the ford; and the emigrants had passed by placing two of their heavy wagons abreast of each other, so as to oppose a considerable mass against the body of water.”

Fremont mentions just two islands, not three. Like other travelers he probably ignored the third island, using just two to make his crossing. The interpretive center at Three Island Crossing State Park tells the story.

One thing not related to the famous crossing at all frustrates rangers there. In recent decades the name Three Island Crossing is often confused with Three Mile Island in the minds of those who remember the nuclear accident that happened a continent away.

The three islands of Three Island Crossing are easy to spot in the picture. The first one is in the center of the photo, with the second one to the left. The third island, the last on the left, wasn’t used by Oregon Trail travelers.

The three islands of Three Island Crossing are easy to spot in the picture. The first one is in the center of the photo, with the second one to the left. The third island, the last on the left, wasn’t used by Oregon Trail travelers.

Narcissa Whitman, one of four missionaries on their way to historic and tragic roles in history, wrote this about the crossing in August of 1836: "We have come fifteen miles and have had the worst route in all the journey for the cart. We might have had a better one but for being misled by some of the company who started out before the leaders.

“It was two o'clock before we came into camp. They were preparing to cross Snake River. The river is divided by two islands into three branches, and is fordable. The packs are placed upon the tops of the highest horses and in this way we crossed without wetting. Two of the tallest horses were selected to carry Mrs. Spalding and myself over. Mr. McLeod gave me his and rode mine. The last branch we rode as much as half a mile in crossing and against the current too, which made it hard for the horses, the water being up to their sides. Husband had considerable difficulty crossing the cart. Both cart and mules were turned upside down in the river and entangled in the harness. The mules would have been drowned but for a desperate struggle to get them ashore. Then after putting two of the strongest horses before the cart, and two men swimming behind to steady it, they succeeded in getting it across.

“I once thought that crossing streams would be the most dreaded part of the journey. I can now cross the most difficult stream without the least fear. There is one manner of crossing which husband has tried but I have not, neither do I wish to. Take an elk skin and stretch it over you, spreading yourself out as much as possible, then let the Indian women carefully put you on the water and with a cord in the mouth they will swim and draw you over. Edward, how do you think you would like to travel in this way?"

John C. Fremont told of another crossing in 1842: “About two o’clock we had arrived at the ford where the road crosses to the right bank of the Snake River. An Indian was hired to conduct us through the ford, which proved impracticable for us, the water sweeping away the howitzer and nearly drowning the mules, which we were able to extricate by cutting them out of the harness. The river is expanded into a little bay, in which there are two islands, across which is the road of the ford; and the emigrants had passed by placing two of their heavy wagons abreast of each other, so as to oppose a considerable mass against the body of water.”

Fremont mentions just two islands, not three. Like other travelers he probably ignored the third island, using just two to make his crossing. The interpretive center at Three Island Crossing State Park tells the story.

One thing not related to the famous crossing at all frustrates rangers there. In recent decades the name Three Island Crossing is often confused with Three Mile Island in the minds of those who remember the nuclear accident that happened a continent away.

The three islands of Three Island Crossing are easy to spot in the picture. The first one is in the center of the photo, with the second one to the left. The third island, the last on the left, wasn’t used by Oregon Trail travelers.

The three islands of Three Island Crossing are easy to spot in the picture. The first one is in the center of the photo, with the second one to the left. The third island, the last on the left, wasn’t used by Oregon Trail travelers.

Published on October 30, 2022 04:00

October 29, 2022

The Cowpuncher (Tap to read)

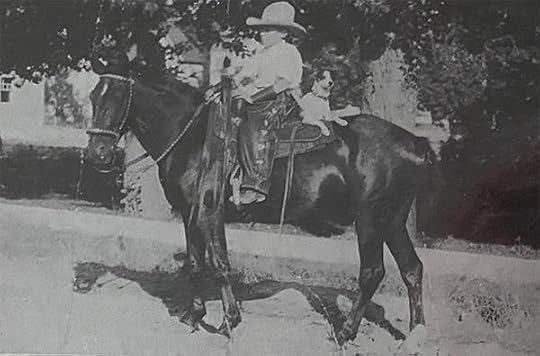

The first motion picture filmed in Idaho left few tracks. One still from the picture remains along with a copy of the play it was developed from, and a poor-quality publicity shot from a newspaper.

Shot in 1915, The Cowpuncher used sites in and around Idaho Falls, including Wolverine Canyon, Taylor Mountain, and various street scenes. Much of the movie revolved around the War Bonnet Roundup that year.

The filming caused quite a stir in Idaho Falls, with the Idaho Register reporting that “Several thousand people forgot to go to church Sunday morning,” going instead to see the shooting of one of the big scenes of the movie.

There might have been a touch of hype when writers described the film. The Evening Capital News in March 1916 said, “Some of the best known motion picture stars were brought to Idaho to film this feature and that they have turned out a masterpiece is conceded by all who have seen the picture.”

C.M. Griffin, Claudia Louise, and Maria Ascaraga were the “best known” stars in the film, none of who even rate an IMDb mention today.

Motion Picture News in its December 25, 1915 edition stated, “It is not likely that a more massive and pretentious Western Picture will ever be attempted.” Clearly, Heaven’s Gate, also shot in Idaho, was decades beyond the writer’s imagination.

Tom Trusky, who knew how to track down information on lost films, was able to locate an Idaho Falls man, Paul Fisher, in 1990. Fisher had appeared in the film as a boy, and he gave Trusky the still below.

Paul Fisher and his dog Spot riding Duke on location in Idaho Falls for the 1915 film, The Cowpuncher.

Paul Fisher and his dog Spot riding Duke on location in Idaho Falls for the 1915 film, The Cowpuncher.

Shot in 1915, The Cowpuncher used sites in and around Idaho Falls, including Wolverine Canyon, Taylor Mountain, and various street scenes. Much of the movie revolved around the War Bonnet Roundup that year.

The filming caused quite a stir in Idaho Falls, with the Idaho Register reporting that “Several thousand people forgot to go to church Sunday morning,” going instead to see the shooting of one of the big scenes of the movie.

There might have been a touch of hype when writers described the film. The Evening Capital News in March 1916 said, “Some of the best known motion picture stars were brought to Idaho to film this feature and that they have turned out a masterpiece is conceded by all who have seen the picture.”

C.M. Griffin, Claudia Louise, and Maria Ascaraga were the “best known” stars in the film, none of who even rate an IMDb mention today.

Motion Picture News in its December 25, 1915 edition stated, “It is not likely that a more massive and pretentious Western Picture will ever be attempted.” Clearly, Heaven’s Gate, also shot in Idaho, was decades beyond the writer’s imagination.

Tom Trusky, who knew how to track down information on lost films, was able to locate an Idaho Falls man, Paul Fisher, in 1990. Fisher had appeared in the film as a boy, and he gave Trusky the still below.

Paul Fisher and his dog Spot riding Duke on location in Idaho Falls for the 1915 film, The Cowpuncher.

Paul Fisher and his dog Spot riding Duke on location in Idaho Falls for the 1915 film, The Cowpuncher.

Published on October 29, 2022 04:00