Rick Just's Blog, page 82

September 27, 2022

The Union Pacific Photo Car (Tap to read)

I ran across a photo in a family album from the 1880s that intrigued me. It wasn’t the subject of the picture; I don’t even know who the kid is. What caught my interest was the cardboard photo frame surrounding the portrait.

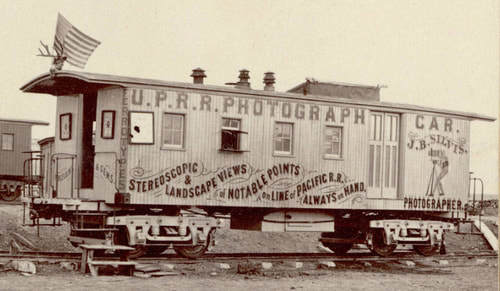

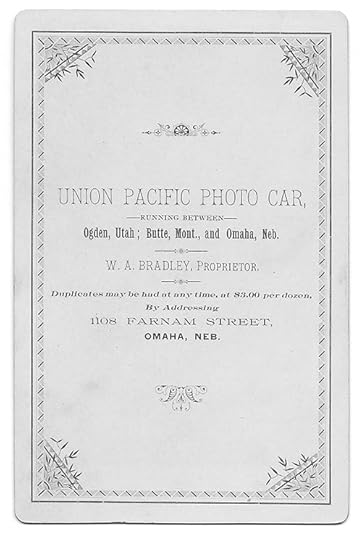

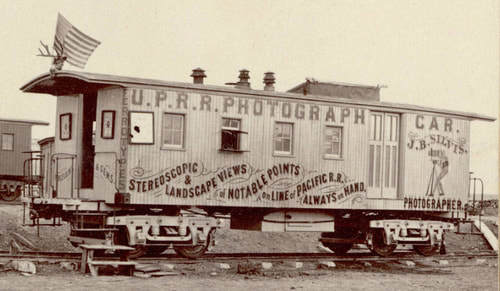

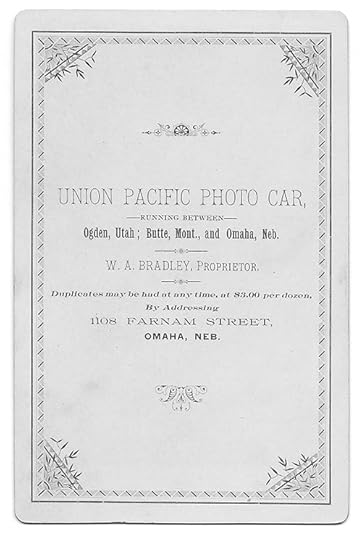

The photo, below was taken by W.A. Bradley and labeled “Union Pacific Photo Car.” The back of the photo (below, below) had a bit more information about the photo car and its route.

I found that the photographer who came up with the idea of building a rail car dedicated to photography was John B. Silvis, a miner who had given up that pursuit to try his luck at something that used the silver he hadn’t had much luck finding.

He had tried his hand at ranching but ended up as a partner in a Salt Lake City photo studio in 1867. The partnership was dissolving about the time they hammered home the golden spike at Promontory, Utah in 1869. Silvis missed taking that famous picture, but he did start taking photos up and down the railroad line as commerce caused a growth spurt.

The details of how he got hold of an old caboose and what his exact relationship with the railroad was are unclear. We know only that he turned the caboose into a photography studio, a darkroom, living quarters, and an office where he could conduct business. Then, he began to catch trains to various points around the West where he would park on a sidetrack and advertise his services to the local community.

I found several clips from the Ketchum Keystone in 1883 advertising Silvis’ services. “The U.P. car will remain there (Hailey) till after the Fourth. This affords all desiring pictures an opportunity to procure them.”

In 1885, the Wood River Times announced that the car was back and under new management. That may have been when Charles Tate took over the car from Silvis, who had retired.

In August of 1888, the Blackfoot News announced that the Union Pacific photograph car was in town and would remain as long as “work lasts.” By then, William A. Bradley was operating the rolling studio. That may have been when the photo of the unidentified toddler below was taken.

The photo car continued to operate for a year or two before disappearing. Others copied the idea, but the original caboose built by Silvis was said to be the best, and there still exist several photos of the photo car.

The Union Pacific Photo Car parked on a siding. Note the deer skull and antlers on the front. This was taken when Silvis still owned it.

The Union Pacific Photo Car parked on a siding. Note the deer skull and antlers on the front. This was taken when Silvis still owned it.  Unidentified infant from a Just family photo album.

Unidentified infant from a Just family photo album.

The back of the above photo frame.

The back of the above photo frame.

The photo, below was taken by W.A. Bradley and labeled “Union Pacific Photo Car.” The back of the photo (below, below) had a bit more information about the photo car and its route.

I found that the photographer who came up with the idea of building a rail car dedicated to photography was John B. Silvis, a miner who had given up that pursuit to try his luck at something that used the silver he hadn’t had much luck finding.

He had tried his hand at ranching but ended up as a partner in a Salt Lake City photo studio in 1867. The partnership was dissolving about the time they hammered home the golden spike at Promontory, Utah in 1869. Silvis missed taking that famous picture, but he did start taking photos up and down the railroad line as commerce caused a growth spurt.

The details of how he got hold of an old caboose and what his exact relationship with the railroad was are unclear. We know only that he turned the caboose into a photography studio, a darkroom, living quarters, and an office where he could conduct business. Then, he began to catch trains to various points around the West where he would park on a sidetrack and advertise his services to the local community.

I found several clips from the Ketchum Keystone in 1883 advertising Silvis’ services. “The U.P. car will remain there (Hailey) till after the Fourth. This affords all desiring pictures an opportunity to procure them.”

In 1885, the Wood River Times announced that the car was back and under new management. That may have been when Charles Tate took over the car from Silvis, who had retired.

In August of 1888, the Blackfoot News announced that the Union Pacific photograph car was in town and would remain as long as “work lasts.” By then, William A. Bradley was operating the rolling studio. That may have been when the photo of the unidentified toddler below was taken.

The photo car continued to operate for a year or two before disappearing. Others copied the idea, but the original caboose built by Silvis was said to be the best, and there still exist several photos of the photo car.

The Union Pacific Photo Car parked on a siding. Note the deer skull and antlers on the front. This was taken when Silvis still owned it.

The Union Pacific Photo Car parked on a siding. Note the deer skull and antlers on the front. This was taken when Silvis still owned it.  Unidentified infant from a Just family photo album.

Unidentified infant from a Just family photo album. The back of the above photo frame.

The back of the above photo frame.

Published on September 27, 2022 04:00

September 26, 2022

Talbot Jennings (Tap to read)

We’ve done stories before about the movie Northwest Passage, filmed near McCall at what is now the North Beach Unit of Ponderosa State Park. The location where the film was shot is the obvious Idaho connection. There is another link to Idaho that you may not know about.

Talbot Jennings, the screenwriter for the film, was born in Shoshone, Idaho in 1894. He attended high school in Nampa and, after serving in World War I, attended the University of Idaho. There he edited the yearbook and an English department publication before graduating Phi Betta Kapa in 1924. He got a master’s degree from Harvard and attended the Yale Drama School.

Jennings is best known for his screenplay for the 1935 movie Mutiny on the Bounty. He wrote or co-wrote 17 in all, receiving two Oscar nominations. His last screenplay was The Sons of Katie Elder, which came out in 1965.

Talbot Jennings died in 1985 at age 90.

Talbot Jennings, the screenwriter for the film, was born in Shoshone, Idaho in 1894. He attended high school in Nampa and, after serving in World War I, attended the University of Idaho. There he edited the yearbook and an English department publication before graduating Phi Betta Kapa in 1924. He got a master’s degree from Harvard and attended the Yale Drama School.

Jennings is best known for his screenplay for the 1935 movie Mutiny on the Bounty. He wrote or co-wrote 17 in all, receiving two Oscar nominations. His last screenplay was The Sons of Katie Elder, which came out in 1965.

Talbot Jennings died in 1985 at age 90.

Published on September 26, 2022 04:00

September 25, 2022

The Switchiest Senator (Tap to read)

There have been 21 U.S. Senators who have switched parties while serving since 1890. Idaho Senator Fred T. Dubois was the switchiest of them all.

Dubois was elected as a Republican in 1890, the year Idaho became a state. Her served a six-year term, and even headed the state’s delegation to the Republican National Convention in 1892 and 1896.

At that 1896 convention, there was a major split in the Republican Party. A faction of the party began calling themselves Silver Republicans. They were in favor of an expansionary monetary policy, the core of which was the minting of silver coins on demand, moving away from a gold-backed currency. It was a popular idea in Idaho and other western states where silver was plentiful. Dubois and other pro-silver Republicans left the convention in protest, forming their own party. He lost his 1896 bid for reelection.

As the turn of the century rolled around, Dubois led Idaho's Silver Republicans into a coalition with the Democrats. He became a rising star in the Democratic Party. Even so, he ran as a Silver Republican in 1900, and won. He was a Silver Republican when he was sworn in but switched to the Democratic party soon after. Dubois served one term as a Democrat, from 1901 to 1907, and did not seek reelection.

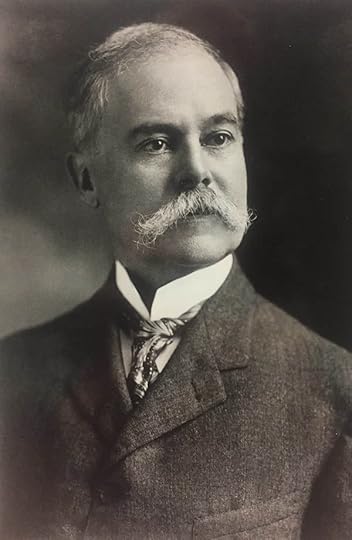

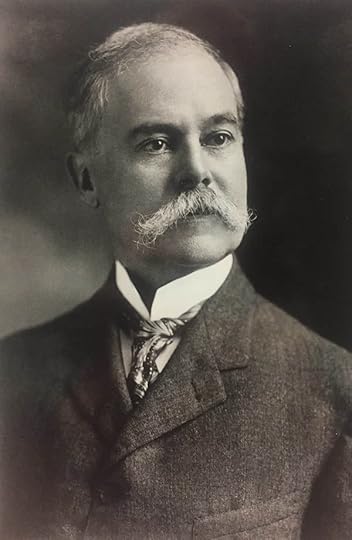

Senator Fred T Dubois (R, SR, D).

Senator Fred T Dubois (R, SR, D).

Dubois was elected as a Republican in 1890, the year Idaho became a state. Her served a six-year term, and even headed the state’s delegation to the Republican National Convention in 1892 and 1896.

At that 1896 convention, there was a major split in the Republican Party. A faction of the party began calling themselves Silver Republicans. They were in favor of an expansionary monetary policy, the core of which was the minting of silver coins on demand, moving away from a gold-backed currency. It was a popular idea in Idaho and other western states where silver was plentiful. Dubois and other pro-silver Republicans left the convention in protest, forming their own party. He lost his 1896 bid for reelection.

As the turn of the century rolled around, Dubois led Idaho's Silver Republicans into a coalition with the Democrats. He became a rising star in the Democratic Party. Even so, he ran as a Silver Republican in 1900, and won. He was a Silver Republican when he was sworn in but switched to the Democratic party soon after. Dubois served one term as a Democrat, from 1901 to 1907, and did not seek reelection.

Senator Fred T Dubois (R, SR, D).

Senator Fred T Dubois (R, SR, D).

Published on September 25, 2022 04:00

September 24, 2022

Serving Three Terms in a Job She Tried to Eliminate (Tap to read)

I was reading the Pupil’s Workbook in the Geography of Idaho one recent rainy Sunday, as one does. That particular workbook was published in 1924. Among its amazing facts and statistics was a comparison of the number of horses in Idaho at the time—284,000—with the number of registered automobiles in the state—54,577.

You might be surprised to learn that the number of horses has stayed fairly steady, with about 220,000 in the state in 2016, compared with a plague of automobiles—more that 600,000.

The workbook was “prepared and arranged” by Ethel E. Redfield, a former superintendent of public instruction in Idaho.

It seemed a little unusual to me for a Superintendent of Education to write a textbook, so I decided to see what her story was.

Ethel Redfield was born April 22, 1877 at Kamiah on the Nez Perce Reservation. She went to college in Portland, getting a BA from Albany College (later renamed Lewis and Clark College) in 1897, then earning a BS the next year from the same school. Redfield started her career at a one-room school in Detroit, Oregon. She soon returned to Idaho as the head of the Latin Department at Lewiston High School from 1906 to 1913, then served as the Nez Perce County Superintendent of Schools for 1906 to 1917.

Redfield ran for Idaho Superintendent of Public Instruction in 1917. Her platform, more or less, was that she wanted the office eliminated.

A new plan for organizing education in Idaho had been developed. Under that plan the office of superintendent of public instruction would be abolished. She ran under the assumption that the legislature would do away with the office in the next session, placing the duties of the position under the secretary of the state board of education.

Redfield won the office. A bill to eliminate it was killed in the Idaho senate, so she chose to serve in the position voters had handed her. She apparently did a good job. The next time elections rolled around, Redfield, a Republican, won easily. She was popular enough that in Canyon County she was nominated as a Democrat and as a Republican during the primary. She beat her Democratic opponent in the primary in that county.

Redfield served three terms as the head of Idaho’s schools, then began a string of jobs in education beginning as the state high school inspector, 1923-34; executive secretary of the State Board of Education, 1924-25; and the State Commissioner of Education, 1925-27. In her spare time, she taught summer school at Idaho State College and received an MS in Education there in 1925. She did additional graduate work at Stanford and Harvard and wrote the above-mentioned text.

In 1928, she began teaching full time at Idaho State College and stayed there until her retirement in 1947. Redfield’s alma mater, Lewis and Clark College in Portland, awarded her an honorary doctorate in 1955. Dr. Redfield, who passed away in 1957, has been called the “Dean of public education in Idaho.”

Thanks to Bud Cornelison for sending me the pupil’s workbook that started me off on this quest.

You might be surprised to learn that the number of horses has stayed fairly steady, with about 220,000 in the state in 2016, compared with a plague of automobiles—more that 600,000.

The workbook was “prepared and arranged” by Ethel E. Redfield, a former superintendent of public instruction in Idaho.

It seemed a little unusual to me for a Superintendent of Education to write a textbook, so I decided to see what her story was.

Ethel Redfield was born April 22, 1877 at Kamiah on the Nez Perce Reservation. She went to college in Portland, getting a BA from Albany College (later renamed Lewis and Clark College) in 1897, then earning a BS the next year from the same school. Redfield started her career at a one-room school in Detroit, Oregon. She soon returned to Idaho as the head of the Latin Department at Lewiston High School from 1906 to 1913, then served as the Nez Perce County Superintendent of Schools for 1906 to 1917.

Redfield ran for Idaho Superintendent of Public Instruction in 1917. Her platform, more or less, was that she wanted the office eliminated.

A new plan for organizing education in Idaho had been developed. Under that plan the office of superintendent of public instruction would be abolished. She ran under the assumption that the legislature would do away with the office in the next session, placing the duties of the position under the secretary of the state board of education.

Redfield won the office. A bill to eliminate it was killed in the Idaho senate, so she chose to serve in the position voters had handed her. She apparently did a good job. The next time elections rolled around, Redfield, a Republican, won easily. She was popular enough that in Canyon County she was nominated as a Democrat and as a Republican during the primary. She beat her Democratic opponent in the primary in that county.

Redfield served three terms as the head of Idaho’s schools, then began a string of jobs in education beginning as the state high school inspector, 1923-34; executive secretary of the State Board of Education, 1924-25; and the State Commissioner of Education, 1925-27. In her spare time, she taught summer school at Idaho State College and received an MS in Education there in 1925. She did additional graduate work at Stanford and Harvard and wrote the above-mentioned text.

In 1928, she began teaching full time at Idaho State College and stayed there until her retirement in 1947. Redfield’s alma mater, Lewis and Clark College in Portland, awarded her an honorary doctorate in 1955. Dr. Redfield, who passed away in 1957, has been called the “Dean of public education in Idaho.”

Thanks to Bud Cornelison for sending me the pupil’s workbook that started me off on this quest.

Published on September 24, 2022 04:00

September 23, 2022

Ohadi Treks to the Big Apple (Tap to read)

In the August 23, 1937 edition of the Idaho Statesman, Walt Beesley wrote, “Goin' to Heaven on a Mule,” that’s a song. “Goin’ to New York on a bull,” that’s an idea.

Some accounts say this loony idea started as a bet. Beesley wrote that it was all a promotional stunt to advertise Ketchum Idaho.

The stunters, or bettors, whichever you prefer, were Ted Terry, of Klamath Falls, Oregon; H.G. Wood, of Boise, and Vic Lusk of Butte, Montana. Their goal was to ride a bull to Madison Square Garden for the 1939 World’s Fair. They would pay their expenses by giving theatrical and radio performances as the Sawtooth Range Riders along the way, not coincidentally ginning up a little publicity.

The expedition included Josephine the pack mule, a horse named Silver Sally, and a dog named Skipper. The cowboys—bullboys?—would take turns riding the Durham-Herford bull fir which they paid $50. They figured it would take 18 to 25 months to complete the trip.

The bull started out with the name Ohadi, which clever readers will notice is Idaho spelled backward. Somewhere along the line, Ohadi became known as Hitler, no doubt a thumbing of the nose to the German dictator who was about to plunge the world into war.

Ernie Pyle, who would soon become a famous war correspondent, wrote a column about the adventure. He wrote that the Sawtooth Range Riders wore “three ten-gallon hats, checkered shirts, flowing bow ties, overalls, bright gloves, and high-heeled cowboy boots. They look just the way New Yorkers think cowboys look.”

Pyle noted that Ohadi had to be broken to ride all over again every morning.

By the time the group got to Chicago, more than two years after they left Ketchum, they weren’t a group anymore. Ted Terry was riding the bull alone, hoping one of his “boys” might join him again as he neared New York.

Three years and 3,000 miles later, Terry and his menagerie rode into the World’s Fair in 1940. Sally, Skipper, and Ohadi/Hitler were all in good shape. No word about what happened to Josephine the Pack Mule. No word, either, about any huge increase in visitation to Ketchum, Idaho, due to the bull-riding stunt. There were quite a few who began visiting the newly built Sun Valley Resort, though. And that’s no bull.

Some accounts say this loony idea started as a bet. Beesley wrote that it was all a promotional stunt to advertise Ketchum Idaho.

The stunters, or bettors, whichever you prefer, were Ted Terry, of Klamath Falls, Oregon; H.G. Wood, of Boise, and Vic Lusk of Butte, Montana. Their goal was to ride a bull to Madison Square Garden for the 1939 World’s Fair. They would pay their expenses by giving theatrical and radio performances as the Sawtooth Range Riders along the way, not coincidentally ginning up a little publicity.

The expedition included Josephine the pack mule, a horse named Silver Sally, and a dog named Skipper. The cowboys—bullboys?—would take turns riding the Durham-Herford bull fir which they paid $50. They figured it would take 18 to 25 months to complete the trip.

The bull started out with the name Ohadi, which clever readers will notice is Idaho spelled backward. Somewhere along the line, Ohadi became known as Hitler, no doubt a thumbing of the nose to the German dictator who was about to plunge the world into war.

Ernie Pyle, who would soon become a famous war correspondent, wrote a column about the adventure. He wrote that the Sawtooth Range Riders wore “three ten-gallon hats, checkered shirts, flowing bow ties, overalls, bright gloves, and high-heeled cowboy boots. They look just the way New Yorkers think cowboys look.”

Pyle noted that Ohadi had to be broken to ride all over again every morning.

By the time the group got to Chicago, more than two years after they left Ketchum, they weren’t a group anymore. Ted Terry was riding the bull alone, hoping one of his “boys” might join him again as he neared New York.

Three years and 3,000 miles later, Terry and his menagerie rode into the World’s Fair in 1940. Sally, Skipper, and Ohadi/Hitler were all in good shape. No word about what happened to Josephine the Pack Mule. No word, either, about any huge increase in visitation to Ketchum, Idaho, due to the bull-riding stunt. There were quite a few who began visiting the newly built Sun Valley Resort, though. And that’s no bull.

Published on September 23, 2022 04:00

September 22, 2022

Silver Set Lost to History (Tap to read)

In January 1975 thieves broke into the Utah State Historical Society and stole $22,380 worth of silver which had once been part of the officers’ mess on the USS Utah. The thieves entered the building via scaffolding that was in use for repairs. The collection included cups, plates, and trays made of sterling silver from the Utah and a sword from an unrelated collection.

And, it is about now that you’re wondering what this has to do with Idaho. Nothing. Maybe.

Just over a year later, the headline in The Idaho Statesman read, “Burglars Loot Museum, Steal Silver.” This time the burglary was in Idaho and the loot was from the USS Idaho. The value of the purloined silver service in Idaho was set as “several hundred dollars,” but it wasn’t the monetary value the Idaho State Historical Society was worried about. The silver tea service from the Idaho, along with a few silver ingots and medals given to Governor Cecil D. Andrus at the Western Governor’s Conference the year before, were prized for their historical value.

The sterling silver tea service had been used during inaugural balls ever since the Idaho had been decommissioned in 1946. It was irreplaceable.

In the Idaho burglary there was no handy scaffolding for the thieves to climb. They brought a ladder with them. One of the burglars—perhaps it was a single burglar—climbed up to reach a window on an enclosed porch, broke the window, then crawled in. This may have been a clue. The window was one foot by one-and-a-half feet, meaning the culprit must have been small.

Once inside the thief or thieves smashed the display case glass to get to the tea set. Police speculated that they used the punch bowl from the set as a basket, piling the rest of the loot inside. They went out a door and fled northeast across Julia Davis Park, marking their route when they dropped a serving tray from the set, not bothering to retrieve it.

And that, sadly, is the end of the story. None of the silver from either robbery was ever recovered. It was likely melted down and cashed in.

The tea service from the USS Idaho had a history with the WWII ship, but its connection to Idaho went even further back. The service was donated by the people of Idaho for use on the predecessor ship, the USS Idaho in 1912, so it had served on two ships bearing that name.

The silver serving set from the USS Idaho, most of which was stolen in 1976. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-2-19.

The silver serving set from the USS Idaho, most of which was stolen in 1976. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-2-19.

And, it is about now that you’re wondering what this has to do with Idaho. Nothing. Maybe.

Just over a year later, the headline in The Idaho Statesman read, “Burglars Loot Museum, Steal Silver.” This time the burglary was in Idaho and the loot was from the USS Idaho. The value of the purloined silver service in Idaho was set as “several hundred dollars,” but it wasn’t the monetary value the Idaho State Historical Society was worried about. The silver tea service from the Idaho, along with a few silver ingots and medals given to Governor Cecil D. Andrus at the Western Governor’s Conference the year before, were prized for their historical value.

The sterling silver tea service had been used during inaugural balls ever since the Idaho had been decommissioned in 1946. It was irreplaceable.

In the Idaho burglary there was no handy scaffolding for the thieves to climb. They brought a ladder with them. One of the burglars—perhaps it was a single burglar—climbed up to reach a window on an enclosed porch, broke the window, then crawled in. This may have been a clue. The window was one foot by one-and-a-half feet, meaning the culprit must have been small.

Once inside the thief or thieves smashed the display case glass to get to the tea set. Police speculated that they used the punch bowl from the set as a basket, piling the rest of the loot inside. They went out a door and fled northeast across Julia Davis Park, marking their route when they dropped a serving tray from the set, not bothering to retrieve it.

And that, sadly, is the end of the story. None of the silver from either robbery was ever recovered. It was likely melted down and cashed in.

The tea service from the USS Idaho had a history with the WWII ship, but its connection to Idaho went even further back. The service was donated by the people of Idaho for use on the predecessor ship, the USS Idaho in 1912, so it had served on two ships bearing that name.

The silver serving set from the USS Idaho, most of which was stolen in 1976. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-2-19.

The silver serving set from the USS Idaho, most of which was stolen in 1976. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-2-19.

Published on September 22, 2022 04:00

September 21, 2022

The Beautiful Nat (Tap to read)

Perhaps the first example of magnificent architecture in the Treasure Valley—before the valley had that name—was Boise’s Natatorium. Dedicated in 1892, the “Nat” cost $87,000 to build. Taxpayers in a town of 2500 would have been hard pressed to build a public pool of that grandeur. It was built as a money-making enterprise by the Boise Artesian Hot & Cold Water Company. Soon, houses along Warm Springs Avenue were advertising that they were heated with “Natatorium water.”

The three-story entrance building, designed in the Moorish style, had twin towers soaring 112 feet into the air on the two front corners. Patrons passed a smoking room on the left and a ladies parlor on the right as they entered. There was a fine café on the top floor, billiard and card rooms, a saloon, tea rooms, a gym, and a balcony dance floor. But the water was the real attraction.

The pool was 125 by 60 feet rippling beneath a 40-foot arched roof. At the south end water cascaded over rocks creating an artificial grotto. There were diving boards for every level of daredevil from five feet to 60 feet. A waterslide extended into the pool from the first balcony and for the particularly courageous a trapeze hung down from the roof.

You would expect people to be dressed in their finery for dances and special events at the Nat, but they didn’t undress much to enter the pool in the early years. Men wore two-piece swimming suits consisting of a short-sleeve shirt and long shorts, while women dipped their toes wearing below-the-knees bloomers and knee-length skirts. Their blouses, which were considered a bit daring, featured puffed sleeves. Just to assure flashes of skin were kept to a minimum, the ladies also wore long stockings.

Travelers to Boise seldom missed a chance to see the Natatorium in the early days. It was the biggest swimming pool in the West. If visitors craved even more entertainment, they could chance the carnival rides at the adjacent White City Park, one of many across the country playing up on the nickname of Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exhibition. The park had a fun house, a roller coaster, a lagoon for paddle boats, a miniature train, and a hot air balloon launch pad.

The Nat was the site of countless weddings, fund-raisers and even inaugural balls during its reign on Warm Springs Avenue. The temperature of the springs that fed the Nat was 170 degrees coming out of the ground and had to be cooled to a pleasant 85 for the pool.

Hot water was what made the Nat possible, but it was also hot water that proved its demise. Much of the classic building was built from wood. Steam and humidity took their toll on the structure.

An ad for the Natatorium that ran on April 29, 1934, led with the line, “Swimming at the NATATORIM is one sport that is not affected by weather.” The irony of that came to light a few weeks later in July, when a freak windstorm brought one of the humidity-weakened roof beams crashing down into the pool, miraculously missing the swimmers.

The owners soon tore down the deteriorating building. There was talk of reconstructing it, but talk was all it was. The City of Boise eventually bought the property and opened a new outdoor pool on the site. There’s a functional support building there behind Adams Elementary. It’s unlikely it will ever generate quite the love that Boise had for the Nat during its 42-year history.

Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)  The Nat’s main plunge featured a 60 by 125-foot pool. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

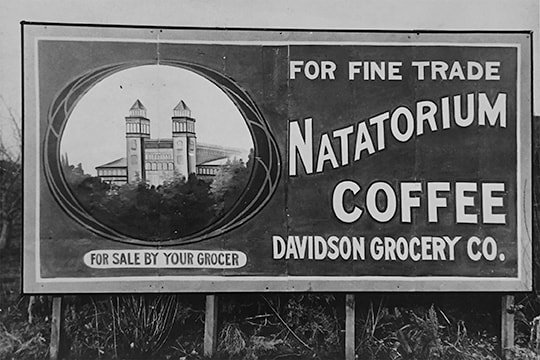

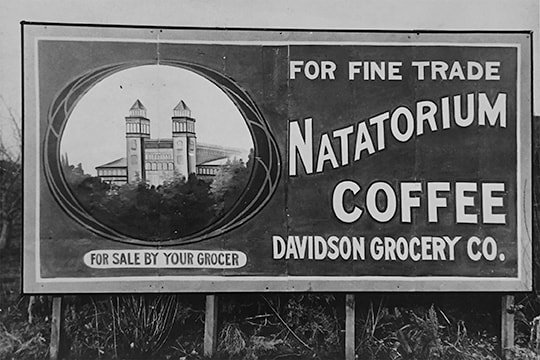

The Nat’s main plunge featured a 60 by 125-foot pool. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)  Natatorium Coffee was available locally, featuring a picture of Boise’s Nat. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo 74-15251F)

Natatorium Coffee was available locally, featuring a picture of Boise’s Nat. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo 74-15251F)

The three-story entrance building, designed in the Moorish style, had twin towers soaring 112 feet into the air on the two front corners. Patrons passed a smoking room on the left and a ladies parlor on the right as they entered. There was a fine café on the top floor, billiard and card rooms, a saloon, tea rooms, a gym, and a balcony dance floor. But the water was the real attraction.

The pool was 125 by 60 feet rippling beneath a 40-foot arched roof. At the south end water cascaded over rocks creating an artificial grotto. There were diving boards for every level of daredevil from five feet to 60 feet. A waterslide extended into the pool from the first balcony and for the particularly courageous a trapeze hung down from the roof.

You would expect people to be dressed in their finery for dances and special events at the Nat, but they didn’t undress much to enter the pool in the early years. Men wore two-piece swimming suits consisting of a short-sleeve shirt and long shorts, while women dipped their toes wearing below-the-knees bloomers and knee-length skirts. Their blouses, which were considered a bit daring, featured puffed sleeves. Just to assure flashes of skin were kept to a minimum, the ladies also wore long stockings.

Travelers to Boise seldom missed a chance to see the Natatorium in the early days. It was the biggest swimming pool in the West. If visitors craved even more entertainment, they could chance the carnival rides at the adjacent White City Park, one of many across the country playing up on the nickname of Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exhibition. The park had a fun house, a roller coaster, a lagoon for paddle boats, a miniature train, and a hot air balloon launch pad.

The Nat was the site of countless weddings, fund-raisers and even inaugural balls during its reign on Warm Springs Avenue. The temperature of the springs that fed the Nat was 170 degrees coming out of the ground and had to be cooled to a pleasant 85 for the pool.

Hot water was what made the Nat possible, but it was also hot water that proved its demise. Much of the classic building was built from wood. Steam and humidity took their toll on the structure.

An ad for the Natatorium that ran on April 29, 1934, led with the line, “Swimming at the NATATORIM is one sport that is not affected by weather.” The irony of that came to light a few weeks later in July, when a freak windstorm brought one of the humidity-weakened roof beams crashing down into the pool, miraculously missing the swimmers.

The owners soon tore down the deteriorating building. There was talk of reconstructing it, but talk was all it was. The City of Boise eventually bought the property and opened a new outdoor pool on the site. There’s a functional support building there behind Adams Elementary. It’s unlikely it will ever generate quite the love that Boise had for the Nat during its 42-year history.

Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)  The Nat’s main plunge featured a 60 by 125-foot pool. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

The Nat’s main plunge featured a 60 by 125-foot pool. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)  Natatorium Coffee was available locally, featuring a picture of Boise’s Nat. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo 74-15251F)

Natatorium Coffee was available locally, featuring a picture of Boise’s Nat. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo 74-15251F)

Published on September 21, 2022 04:00

September 20, 2022

The Turner Explosion (Tap to read)

Before rural electrification, many small communities relied on acetylene lighting systems, sometimes with disastrous results.

On the evening of January 27, 1927, there was a basketball game in Turner, Idaho, near present-day Grace. The boys were playing rivals from nearby Central, Idaho. About 200 people turned out for the match, which was held at the Mormon Chapel and Recreation Hall.

The game had just begun in the one-story frame building when the lights went out. Janitor James McCann went down into the basement to check on the acetylene tanks and lighting notoriously cranky system. Meanwhile, the crowd had started to make its way out of the only exit in the dark. Someone lit a match.

The explosion blew out the rear wall of the building. A portion of the ceiling fell, dropping timbers and plaster into the crowd. Soon, the front wall collapsed as well. When everyone was accounted for, dozens were injured, and six lay dead.

Janitor McCann was among the dead, as were his two sons and his brother, Brigham.

On the evening of January 27, 1927, there was a basketball game in Turner, Idaho, near present-day Grace. The boys were playing rivals from nearby Central, Idaho. About 200 people turned out for the match, which was held at the Mormon Chapel and Recreation Hall.

The game had just begun in the one-story frame building when the lights went out. Janitor James McCann went down into the basement to check on the acetylene tanks and lighting notoriously cranky system. Meanwhile, the crowd had started to make its way out of the only exit in the dark. Someone lit a match.

The explosion blew out the rear wall of the building. A portion of the ceiling fell, dropping timbers and plaster into the crowd. Soon, the front wall collapsed as well. When everyone was accounted for, dozens were injured, and six lay dead.

Janitor McCann was among the dead, as were his two sons and his brother, Brigham.

Published on September 20, 2022 04:00

September 19, 2022

Murder and the Mayor (Tap to read)

You might want to refill your coffee cup before reading today’s story. My posts are usually fairly short. This one just kept growing and growing as I learned more about the mayor and the murder.

Duncan McDougal Johnston was a WWI veteran who served in France with Battery B, 146th field artillery unit. He moved to Twin Falls from Boise in 1928 to open a jewelry store. By 1936 he was the Mayor of Twin Falls. That was the year he was briefly a candidate for congress in Idaho’s second congressional district, running against incumbent Congressman D. Worth Clark in the Democratic primary. In April 1938 he was the toastmaster at the Jefferson Day banquet in Twin Falls, lauding Congressman Clark. By December of 1938, at age 39, he was the former mayor of Twin Falls and he had been convicted of murder.

Johnston was convicted of killing a jewelry salesman by the name of George L. Olson of Salt Lake. Olson was found locked in his car at a Twin Falls hotel some days after being shot in the head. About $18,000 worth of Olson’s jewelry along with a .25-caliber gun believed to have been the murder weapon were found in the basement of Johnston’s jewelry store.

In one of many novel-worthy twists, the judge for Johnston’s trial, James W. Porter, had been the man’s commanding officer during the war.

Early in the investigation there was some question about Salt Lake City police officers getting involved with the case. Salt Lake City Police Bureau Sergeant Albert H. Roberts put that to rest when he said that Twin Falls Police Chief Howard Gillette “(knew) his onions” when it came to interviewing suspects. And, yes, I gratuitously included that otherwise unimportant quote simply because it sounded like something out of a Mickey Spillane novel.

It wasn’t the only pulp fiction moment. One headline in The Times News read, “Slain Man With Beautiful Boise Girl, Proprietors and Chef Assert.” The proprietors were Mr. and Mrs. Howard McKray, owners of the tourist park where Olson had stayed, and the chef worked at a nearby restaurant. They were witnesses who saw the beautiful girl.

“I know it was him because that was the name he used. He was registered with us from Salt Lake City, was a jewelry salesman, and the picture in the papers was an exact likeness of him,” Mrs. McKray told reporters. Breathlessly, perhaps.

“Olson ran up a bill of $16,” the chef said, “and finally he traded me a wedding ring and engagement ring which I am going to give to my girl, Flossie Colson, who is working for me, when I marry her.” No word on how Flossie felt about getting a $16 wedding set swapped for corned beef hash.

During the trial one witness was described—Spillane style—as “a pretty, bespectacled telephone operator.” The newspaper reporter noted that she gave one of her answers “with a toss of her head.”

Meanwhile, the victim’s wife was a “pretty, youthful widow” and another witness was described as “comely.”

Patrolman Craig T. Bracken was a key witness in the case. His role was to hide in the basement of the jewelry store and spy on Johnston. The basement was accessible not only from the jewelry store but from an adjacent dress shop. He watched the man come down the stairs, toss something in the furnace, then turn and stare at a break or crack in the basement wall for a few seconds. Johnston left, but came back down the stairs a few minutes later, again paying some attention to the hole in the wall. That’s when the jeweler noticed the patrolman hiding behind the furnace. Bracken called out to Johnston, saying “Well, Dunc, they put me down here to watch you and see what you were doing.” Bracken arrested Johnston and took him to the station. Chief Gillette and another patrolmen went to the store and into the basement where they found 557 rings tied up in a towel, keys to the murdered man’s car, and a .25-caliber pistol.

Johnston and his assistant in the Jewelry store, William LaVonde, were arrested on suspicion of murder. LaVonde was more than an assistant to Johnston. They had served in the war together and were long time buddies. LaVonde was also a former desk sergeant with the Twin Falls police.

The men, both well-known in the community, were arrested June 2. On June 6, while in jail, Johnston completed the sale of his jewelry store to Don Kugler, of Idaho Falls. Had Johnston’s business been in trouble? Was that a motive for murder and robbery?

There was no provision for posting bail in Idaho at the time when one was accused of first-degree murder. LaVonde, the assistant in the jewelry store, asked for a writ of habeas corpus on the grounds there was no compelling evidence against him. On September 16, the Idaho Supreme Court granted his petition and LaVonde went free. But not for long. A revised complaint got him tossed back in jail on the 20th. But not for long. A judge freed him on the 26th citing a lack of evidence against LaVonde in the case, but at the same time binding over Johnston for trial.

Even in an agricultural community it was a little odd that twelve men—11 of them farmers and the 12th a retired farmer—would pass judgement on Johnston. They were particularly qualified to understand when one of the prosecution witnesses explained why pieces of earth found in the victim’s car had not been analyzed. “There’s a lot of dirt in Twin Falls County,” the witness said.

The prosecution was built largely on the fact that the stolen jewels, the victim’s car keys, and an alleged murder weapon—the FBI could not say whether or not it had been the one used—were found in the basement of Johnston’s jewelry store. Meanwhile, the defense pointed out that furnace service men, the dress shop owners, employees of a Chinese restaurant, and a rooming house operator all had keys to the same basement.

The defense opted not to make a final statement in the trial, perhaps assuming that a case built on circumstantial evidence didn’t need a summation to point that out. Or, maybe it did. The jury came back after eight hours of deliberation with a guilty verdict. Johnston was sentenced to life in prison.

On December 15, 1938, Duncan Johnston greeted an old friend by saying, “Hello, Pearl,” and giving Pearl C. Meredith a smile. Meredith was the warden of the Idaho State Penitentiary.

In 1939, the Idaho Supreme Court ordered a retrial of Johnston, citing questionable testimony by the Twin Falls Chief of Police. Johnston spent much more time on the stand defending himself in this trial. It didn’t help. He was found guilty, again. Johnston appealed, again, to the Idaho Supreme Court.

Then the confession showed up. On March 19, 1941, Governor Chase Clark received a note using letters cut from The Salt Lake Tribune and pasted on the paper in the fashion of a ransom demand. The anonymous message sender claimed that Johnston was the victim of a “vicious frame-up.” Although a cut-up Salt Lake newspaper was used, the letter came from Klamath Falls, Oregon.

Though interesting, the note proved nothing. The supreme court denied Johnston a third trial.

So, in December of 1941, the convicted murderer petitioned the pardon board for clemency.

At his January 1942 hearing, Johnston stood up to give an impassioned speech as the pardon board was rising to leave. The Idaho Statesman quoted him as saying, “Three and one-half years ago, or a little more, I sat as you gentlemen here today. My word had never been doubted. My integrity was as high… as anyone.

“From the time I was arrested until the present day, I have been a dastardly liar. I have been a Capone. I have been the coldest blooded murderer in the State of Idaho. Dillinger is a sissy to the side of me…

“You gentlemen have no idea what it means to sit behind bars and listen to the clang of chains and keys, when you did not commit the crime that was framed against you. It is almost unbelievable that in the United States, where we criticize the Nazis and the Gestapo, that you can find it right here in your own community.”

His pardon was denied by a 2-1 vote of the board.

He was back, again, in April asking for a pardon. Again, the vote was 2-1 against.

Then, there was a new twist. On December 21, 1942, the front-page headline spread across eight columns in The Statesman read, “Duncan Johnston Escapes From Prison.”

Under the cover of “pea-soup” fog, Johnston ran through the freshly fallen snow to an awaiting car in the 1400 block of East Washington and made his escape. He had constructed a dummy to occupy his bed during his getaway. His breakout was made easier because he wasn’t living in the prison. Johnston was a trusty residing in a small house adjacent to the hot-water pumps that supplied water to Warm Springs Avenue homes.

At least, that was the sensational story on December 21. By the next day, the front-page story was not nearly so dramatic. The headline read, “Johnston Returns to Cell After Going Bye-Bye Third Time.” Wait. Third time? Yes, it turned out Johnston had walked away a couple of other times, visiting Public School Field and the Ada County Courthouse the previous two times. The warden had neglected to mention those incidents. Johnston wasn’t captured. He simply walked back to the prison after spending seven hours walking around trying to “relieve a feeling of despondency” over his prison term.

So, pardon was probably off the table, right? Stand by.

His appeal for pardon that December, which happened to be decided the day after he walked away—and back—was denied.

His fourth application for pardon came in April 1943. It was denied.

In July 1943, the board denied his fifth application. His six application was denied that October.

On his seventh application, the board vote flipped in Johnston’s favor when Attorney General Bert H. Miller changed his vote. Why? He had determined through exhaustive investigation that several jurors as well as the prosecutors, were not convinced that Johnston had fired the fatal shot. Miller thought there was no proof he had fired the shot, and therefore Johnston had not been proved guilty. Miller was quoted in The Times News as saying, “I am not voting to pardon Johnston, but to release him from punishment for a crime for which he was unjustly convicted.”

Mr. and Mrs. C.D. Merrill, of Ketchum, had taken on Johnston’s case almost as a hobby, continuing to pester the pardon board time after time. They truly believed in his innocence and didn’t have a personal dog in the fight. They didn’t even know Johnston before he was imprisoned.

Johnston was grateful to the Merrills, but remained bitter, saying he wanted a reversal of his murder conviction in court instead of a pardon. “Naturally, I am terribly thankful for my freedom,” he said, “And it is hard to say thanks for something you don’t want—that is, I am glad to be free, but I didn’t want it to come this way.”

Johnston planned to go into defense work for the military, perhaps in California. “I went through five campaigns in the last war and came out a disabled veteran. Nothing would please me more than to do something in this campaign.”

Whether Johnston ever served in any capacity in WWII is unknown. He apparently left Idaho shortly after his pardon. His grandniece contacted me after this story ran the first time to say that he had operated a successful jewelry store in the Mission District of San Francisco for many years. He lived to be 90, passing away in San Mateo California in 1989.

The Olson murder case was never reopened.

But what of Attorney General Bert H. Miller? Many were outraged at his vote that set Johnston free. There were grumblings that his time as attorney general would soon be over. It was, but not in the way those who disagreed with him on the Johnston case might have hoped. He was elected a justice of Idaho’s Supreme Court in 1944, then elected a U.S. senator from Idaho in 1948, defeating Senator Henry Dworshak. Miller served only nine months in that office before dying of a heart attack. In a twist that probably ruffled a few feathers, Governor C.A. Robbins appointed Dworshak, the man Miller narrowly defeated, to fill out his term. Dworshak would remain a senator until 1962, when he, too, died of a heart attack while in office.

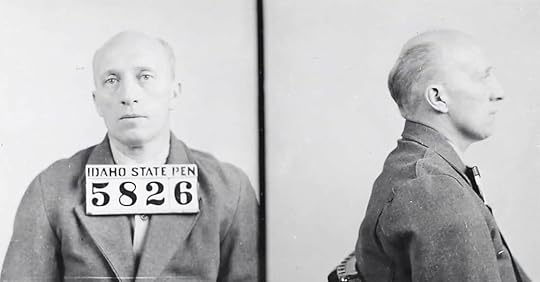

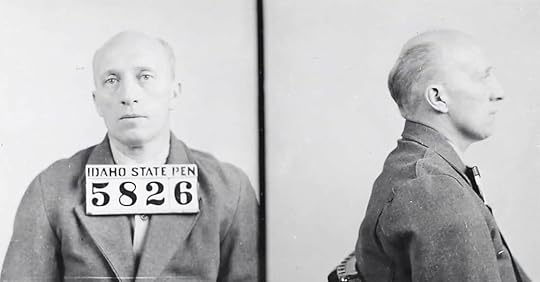

Duncan McDougal Johnston's prison mugshot, 1938.

Duncan McDougal Johnston's prison mugshot, 1938.

Duncan McDougal Johnston was a WWI veteran who served in France with Battery B, 146th field artillery unit. He moved to Twin Falls from Boise in 1928 to open a jewelry store. By 1936 he was the Mayor of Twin Falls. That was the year he was briefly a candidate for congress in Idaho’s second congressional district, running against incumbent Congressman D. Worth Clark in the Democratic primary. In April 1938 he was the toastmaster at the Jefferson Day banquet in Twin Falls, lauding Congressman Clark. By December of 1938, at age 39, he was the former mayor of Twin Falls and he had been convicted of murder.

Johnston was convicted of killing a jewelry salesman by the name of George L. Olson of Salt Lake. Olson was found locked in his car at a Twin Falls hotel some days after being shot in the head. About $18,000 worth of Olson’s jewelry along with a .25-caliber gun believed to have been the murder weapon were found in the basement of Johnston’s jewelry store.

In one of many novel-worthy twists, the judge for Johnston’s trial, James W. Porter, had been the man’s commanding officer during the war.

Early in the investigation there was some question about Salt Lake City police officers getting involved with the case. Salt Lake City Police Bureau Sergeant Albert H. Roberts put that to rest when he said that Twin Falls Police Chief Howard Gillette “(knew) his onions” when it came to interviewing suspects. And, yes, I gratuitously included that otherwise unimportant quote simply because it sounded like something out of a Mickey Spillane novel.

It wasn’t the only pulp fiction moment. One headline in The Times News read, “Slain Man With Beautiful Boise Girl, Proprietors and Chef Assert.” The proprietors were Mr. and Mrs. Howard McKray, owners of the tourist park where Olson had stayed, and the chef worked at a nearby restaurant. They were witnesses who saw the beautiful girl.

“I know it was him because that was the name he used. He was registered with us from Salt Lake City, was a jewelry salesman, and the picture in the papers was an exact likeness of him,” Mrs. McKray told reporters. Breathlessly, perhaps.

“Olson ran up a bill of $16,” the chef said, “and finally he traded me a wedding ring and engagement ring which I am going to give to my girl, Flossie Colson, who is working for me, when I marry her.” No word on how Flossie felt about getting a $16 wedding set swapped for corned beef hash.

During the trial one witness was described—Spillane style—as “a pretty, bespectacled telephone operator.” The newspaper reporter noted that she gave one of her answers “with a toss of her head.”

Meanwhile, the victim’s wife was a “pretty, youthful widow” and another witness was described as “comely.”

Patrolman Craig T. Bracken was a key witness in the case. His role was to hide in the basement of the jewelry store and spy on Johnston. The basement was accessible not only from the jewelry store but from an adjacent dress shop. He watched the man come down the stairs, toss something in the furnace, then turn and stare at a break or crack in the basement wall for a few seconds. Johnston left, but came back down the stairs a few minutes later, again paying some attention to the hole in the wall. That’s when the jeweler noticed the patrolman hiding behind the furnace. Bracken called out to Johnston, saying “Well, Dunc, they put me down here to watch you and see what you were doing.” Bracken arrested Johnston and took him to the station. Chief Gillette and another patrolmen went to the store and into the basement where they found 557 rings tied up in a towel, keys to the murdered man’s car, and a .25-caliber pistol.

Johnston and his assistant in the Jewelry store, William LaVonde, were arrested on suspicion of murder. LaVonde was more than an assistant to Johnston. They had served in the war together and were long time buddies. LaVonde was also a former desk sergeant with the Twin Falls police.

The men, both well-known in the community, were arrested June 2. On June 6, while in jail, Johnston completed the sale of his jewelry store to Don Kugler, of Idaho Falls. Had Johnston’s business been in trouble? Was that a motive for murder and robbery?

There was no provision for posting bail in Idaho at the time when one was accused of first-degree murder. LaVonde, the assistant in the jewelry store, asked for a writ of habeas corpus on the grounds there was no compelling evidence against him. On September 16, the Idaho Supreme Court granted his petition and LaVonde went free. But not for long. A revised complaint got him tossed back in jail on the 20th. But not for long. A judge freed him on the 26th citing a lack of evidence against LaVonde in the case, but at the same time binding over Johnston for trial.

Even in an agricultural community it was a little odd that twelve men—11 of them farmers and the 12th a retired farmer—would pass judgement on Johnston. They were particularly qualified to understand when one of the prosecution witnesses explained why pieces of earth found in the victim’s car had not been analyzed. “There’s a lot of dirt in Twin Falls County,” the witness said.

The prosecution was built largely on the fact that the stolen jewels, the victim’s car keys, and an alleged murder weapon—the FBI could not say whether or not it had been the one used—were found in the basement of Johnston’s jewelry store. Meanwhile, the defense pointed out that furnace service men, the dress shop owners, employees of a Chinese restaurant, and a rooming house operator all had keys to the same basement.

The defense opted not to make a final statement in the trial, perhaps assuming that a case built on circumstantial evidence didn’t need a summation to point that out. Or, maybe it did. The jury came back after eight hours of deliberation with a guilty verdict. Johnston was sentenced to life in prison.

On December 15, 1938, Duncan Johnston greeted an old friend by saying, “Hello, Pearl,” and giving Pearl C. Meredith a smile. Meredith was the warden of the Idaho State Penitentiary.

In 1939, the Idaho Supreme Court ordered a retrial of Johnston, citing questionable testimony by the Twin Falls Chief of Police. Johnston spent much more time on the stand defending himself in this trial. It didn’t help. He was found guilty, again. Johnston appealed, again, to the Idaho Supreme Court.

Then the confession showed up. On March 19, 1941, Governor Chase Clark received a note using letters cut from The Salt Lake Tribune and pasted on the paper in the fashion of a ransom demand. The anonymous message sender claimed that Johnston was the victim of a “vicious frame-up.” Although a cut-up Salt Lake newspaper was used, the letter came from Klamath Falls, Oregon.

Though interesting, the note proved nothing. The supreme court denied Johnston a third trial.

So, in December of 1941, the convicted murderer petitioned the pardon board for clemency.

At his January 1942 hearing, Johnston stood up to give an impassioned speech as the pardon board was rising to leave. The Idaho Statesman quoted him as saying, “Three and one-half years ago, or a little more, I sat as you gentlemen here today. My word had never been doubted. My integrity was as high… as anyone.

“From the time I was arrested until the present day, I have been a dastardly liar. I have been a Capone. I have been the coldest blooded murderer in the State of Idaho. Dillinger is a sissy to the side of me…

“You gentlemen have no idea what it means to sit behind bars and listen to the clang of chains and keys, when you did not commit the crime that was framed against you. It is almost unbelievable that in the United States, where we criticize the Nazis and the Gestapo, that you can find it right here in your own community.”

His pardon was denied by a 2-1 vote of the board.

He was back, again, in April asking for a pardon. Again, the vote was 2-1 against.

Then, there was a new twist. On December 21, 1942, the front-page headline spread across eight columns in The Statesman read, “Duncan Johnston Escapes From Prison.”

Under the cover of “pea-soup” fog, Johnston ran through the freshly fallen snow to an awaiting car in the 1400 block of East Washington and made his escape. He had constructed a dummy to occupy his bed during his getaway. His breakout was made easier because he wasn’t living in the prison. Johnston was a trusty residing in a small house adjacent to the hot-water pumps that supplied water to Warm Springs Avenue homes.

At least, that was the sensational story on December 21. By the next day, the front-page story was not nearly so dramatic. The headline read, “Johnston Returns to Cell After Going Bye-Bye Third Time.” Wait. Third time? Yes, it turned out Johnston had walked away a couple of other times, visiting Public School Field and the Ada County Courthouse the previous two times. The warden had neglected to mention those incidents. Johnston wasn’t captured. He simply walked back to the prison after spending seven hours walking around trying to “relieve a feeling of despondency” over his prison term.

So, pardon was probably off the table, right? Stand by.

His appeal for pardon that December, which happened to be decided the day after he walked away—and back—was denied.

His fourth application for pardon came in April 1943. It was denied.

In July 1943, the board denied his fifth application. His six application was denied that October.

On his seventh application, the board vote flipped in Johnston’s favor when Attorney General Bert H. Miller changed his vote. Why? He had determined through exhaustive investigation that several jurors as well as the prosecutors, were not convinced that Johnston had fired the fatal shot. Miller thought there was no proof he had fired the shot, and therefore Johnston had not been proved guilty. Miller was quoted in The Times News as saying, “I am not voting to pardon Johnston, but to release him from punishment for a crime for which he was unjustly convicted.”

Mr. and Mrs. C.D. Merrill, of Ketchum, had taken on Johnston’s case almost as a hobby, continuing to pester the pardon board time after time. They truly believed in his innocence and didn’t have a personal dog in the fight. They didn’t even know Johnston before he was imprisoned.

Johnston was grateful to the Merrills, but remained bitter, saying he wanted a reversal of his murder conviction in court instead of a pardon. “Naturally, I am terribly thankful for my freedom,” he said, “And it is hard to say thanks for something you don’t want—that is, I am glad to be free, but I didn’t want it to come this way.”

Johnston planned to go into defense work for the military, perhaps in California. “I went through five campaigns in the last war and came out a disabled veteran. Nothing would please me more than to do something in this campaign.”

Whether Johnston ever served in any capacity in WWII is unknown. He apparently left Idaho shortly after his pardon. His grandniece contacted me after this story ran the first time to say that he had operated a successful jewelry store in the Mission District of San Francisco for many years. He lived to be 90, passing away in San Mateo California in 1989.

The Olson murder case was never reopened.

But what of Attorney General Bert H. Miller? Many were outraged at his vote that set Johnston free. There were grumblings that his time as attorney general would soon be over. It was, but not in the way those who disagreed with him on the Johnston case might have hoped. He was elected a justice of Idaho’s Supreme Court in 1944, then elected a U.S. senator from Idaho in 1948, defeating Senator Henry Dworshak. Miller served only nine months in that office before dying of a heart attack. In a twist that probably ruffled a few feathers, Governor C.A. Robbins appointed Dworshak, the man Miller narrowly defeated, to fill out his term. Dworshak would remain a senator until 1962, when he, too, died of a heart attack while in office.

Duncan McDougal Johnston's prison mugshot, 1938.

Duncan McDougal Johnston's prison mugshot, 1938.

Published on September 19, 2022 04:00

September 18, 2022

When the Stars (sort of) Came to Boise (Tap to read)

February 20, 1940 was a much-anticipated date in Boise. That evening would be the world premiere of a major motion picture at the Pinney Theater.

The movie was Northwest Passage, filmed around McCall, particularly in what is today the North Beach Unit of Ponderosa State Park. It starred some big-name actors, Spencer Tracy, Robert Young, Walter Brennan, and Ruth Hussey.

Based on a popular novel of the same name by Kenneth Roberts, Northwest Passage was called an “epic” picture and “Hollywood’s Greatest Adventure Drama” in headlines leading up to the premiere. Roberts was billed as “America’s foremost historical novelist.”

Filming the movie had certainly been an epic adventure for the citizens of McCall. It was shot over two summer seasons. Some 900 locals worked as extras and at other jobs related to filming. The production set up shop on 50 acres bordering Payette Lake. Twelve freight cars brought in dozens of Indian drums, sugar kettles, gun racks, weaving frames, rush bottom chairs, spinning wheels, leather bellows, anvils, and 1,000 cannon balls. It was a virtual traveling museum including antique desks, tables and chests, pelts of every North American mammal worth mentioning, candlesticks, mahogany buckets, brass clocks, and on and on.

A blacksmith shop was built to look like it originated in 1750 for some of the movie scenes, and it was used to forge nails for the buildings the crew would set up. Every effort was made to assure the props looked like the real thing. Indian items were designed using tribal markings of the Abenakia (the setting for the movie was in Maine). For verisimilitude the 700 scalps hung from poles on the set were made with human hair, though the “scalps” were made of rubber.

The green buckskin uniforms Rogers’ Rangers wore in the movie seemed totally wrong to people used to brown or buttery yellow buckskin. In the book, Roberts had specified that they wore green buckskin, so MGM went with that, though it was a constant headache to keep the costumes dyed evenly.

This was to be two-time Academy Award-winner Spencer Tracy’s greatest role, playing Major Rogers, of Rogers’ Rangers. Legendary director King Vidor directed. So, the speculation in Boise was, who would show up for the premiere?

On January 10, Pinney Theater Manager J.R. Mendenhall announced that Robert Young would attend, along with others yet to be named. Also, yet to be named were the members of the local committee set up to plan the festivities surrounding the premiere. Governor C.A. Bottolfsen didn’t waste any time, naming Idahoans from Boise, Caldwell, Nampa, Weiser, Payette, and Emmett to the committee, with state Senator Carl E. Brown of McCall to head it. Brown, along with the McCall Chamber of Commerce and the Idaho Timber Protective Association had been instrumental in bringing the production to Payette Lake.

As the date approached there was continued speculation in The Idaho Statesman about who would attend. Would King Vidor be there? Tracy? Brennan? Young? There was also speculation about what reserved seats at the Pinney would cost, this during a time when a ticket to the movies was typically 15 cents. MGM, suggested $2.50 would be about right. The Pinney settled on $1.10, and assured those who might be outraged at the price that the film would stick around for at least a couple of weeks at regular prices.

Meanwhile, the Governor’s committee charged ahead with planning. The stars, whoever they were, would be greeted at the Boise Depot at 7:23 am by committee members and Mayor James L. Straight. Then, it was off to the Owyhee hotel for a breakfast to be attended by the committee members and their wives (no women were on the committee) and the stars. After breakfast the stars would be escorted (by the committee) to the governor’s office. All Idaho mayors were invited to be on hand for that meet and greet. Then, at 12:15 a public luncheon starring the stars would be sponsored by the Boise Chamber of Commerce, with tickets available to the masses. At 2 pm there would be a parade featuring high school students—participants in a costume contest—dressed in clothing as depicted in the movie. Along the way merchants were expected to have appropriate displays.

That evening, a radio broadcast would air from 8 until 8:30 outside the theater, around which would be Hollywood props and spotlights. Then, practically as an afterthought, they would show the film. The stars would catch the 11:20 out of town.

So, when the big day came, who of the Who’s Who showed up? Stars. Maybe none you’ve ever heard of, but it was still a big deal to welcome Ilona Massey, Virginia Grey, Alan Curtis, Isabel Jewell, and Nat Pendelton, luminaries all, to town. The crowd that came to see them was reportedly so enthusiastic that Boise’s new fire engine had to be called to rescue the actors, which was totally not a planned event. Certainly unplanned was the trampling of several cars when the star-struck climbed on hoods and roofs the better to capture a bit of stardust. And, as if to justify the firetruck, one of the klieg lights caught a tree branch on fire.

For those on tenterhooks, Shirley Weisgerber won the costume contest. Meanwhile, Spencer Tracy sent a telegram to the governor expressing his regrets for being unable to attend due to his “continued employment in Hollywood on Edison the Man.”

There was to be a sequel to Northwest Passage, but the studio never got around to making it. The movie won the Academy Award for best cinematography in 1941, in spite of the glowing green costumes.

From left to right, Robert Young, Spencer Tracy, and Walter Brennan commiserate beneath a ponderosa pine on the set of Northwest Passage near McCall. The world premiere for the movie was held at the Pinney Theater in Boise.

From left to right, Robert Young, Spencer Tracy, and Walter Brennan commiserate beneath a ponderosa pine on the set of Northwest Passage near McCall. The world premiere for the movie was held at the Pinney Theater in Boise.

The movie was Northwest Passage, filmed around McCall, particularly in what is today the North Beach Unit of Ponderosa State Park. It starred some big-name actors, Spencer Tracy, Robert Young, Walter Brennan, and Ruth Hussey.

Based on a popular novel of the same name by Kenneth Roberts, Northwest Passage was called an “epic” picture and “Hollywood’s Greatest Adventure Drama” in headlines leading up to the premiere. Roberts was billed as “America’s foremost historical novelist.”

Filming the movie had certainly been an epic adventure for the citizens of McCall. It was shot over two summer seasons. Some 900 locals worked as extras and at other jobs related to filming. The production set up shop on 50 acres bordering Payette Lake. Twelve freight cars brought in dozens of Indian drums, sugar kettles, gun racks, weaving frames, rush bottom chairs, spinning wheels, leather bellows, anvils, and 1,000 cannon balls. It was a virtual traveling museum including antique desks, tables and chests, pelts of every North American mammal worth mentioning, candlesticks, mahogany buckets, brass clocks, and on and on.

A blacksmith shop was built to look like it originated in 1750 for some of the movie scenes, and it was used to forge nails for the buildings the crew would set up. Every effort was made to assure the props looked like the real thing. Indian items were designed using tribal markings of the Abenakia (the setting for the movie was in Maine). For verisimilitude the 700 scalps hung from poles on the set were made with human hair, though the “scalps” were made of rubber.

The green buckskin uniforms Rogers’ Rangers wore in the movie seemed totally wrong to people used to brown or buttery yellow buckskin. In the book, Roberts had specified that they wore green buckskin, so MGM went with that, though it was a constant headache to keep the costumes dyed evenly.

This was to be two-time Academy Award-winner Spencer Tracy’s greatest role, playing Major Rogers, of Rogers’ Rangers. Legendary director King Vidor directed. So, the speculation in Boise was, who would show up for the premiere?

On January 10, Pinney Theater Manager J.R. Mendenhall announced that Robert Young would attend, along with others yet to be named. Also, yet to be named were the members of the local committee set up to plan the festivities surrounding the premiere. Governor C.A. Bottolfsen didn’t waste any time, naming Idahoans from Boise, Caldwell, Nampa, Weiser, Payette, and Emmett to the committee, with state Senator Carl E. Brown of McCall to head it. Brown, along with the McCall Chamber of Commerce and the Idaho Timber Protective Association had been instrumental in bringing the production to Payette Lake.

As the date approached there was continued speculation in The Idaho Statesman about who would attend. Would King Vidor be there? Tracy? Brennan? Young? There was also speculation about what reserved seats at the Pinney would cost, this during a time when a ticket to the movies was typically 15 cents. MGM, suggested $2.50 would be about right. The Pinney settled on $1.10, and assured those who might be outraged at the price that the film would stick around for at least a couple of weeks at regular prices.

Meanwhile, the Governor’s committee charged ahead with planning. The stars, whoever they were, would be greeted at the Boise Depot at 7:23 am by committee members and Mayor James L. Straight. Then, it was off to the Owyhee hotel for a breakfast to be attended by the committee members and their wives (no women were on the committee) and the stars. After breakfast the stars would be escorted (by the committee) to the governor’s office. All Idaho mayors were invited to be on hand for that meet and greet. Then, at 12:15 a public luncheon starring the stars would be sponsored by the Boise Chamber of Commerce, with tickets available to the masses. At 2 pm there would be a parade featuring high school students—participants in a costume contest—dressed in clothing as depicted in the movie. Along the way merchants were expected to have appropriate displays.

That evening, a radio broadcast would air from 8 until 8:30 outside the theater, around which would be Hollywood props and spotlights. Then, practically as an afterthought, they would show the film. The stars would catch the 11:20 out of town.

So, when the big day came, who of the Who’s Who showed up? Stars. Maybe none you’ve ever heard of, but it was still a big deal to welcome Ilona Massey, Virginia Grey, Alan Curtis, Isabel Jewell, and Nat Pendelton, luminaries all, to town. The crowd that came to see them was reportedly so enthusiastic that Boise’s new fire engine had to be called to rescue the actors, which was totally not a planned event. Certainly unplanned was the trampling of several cars when the star-struck climbed on hoods and roofs the better to capture a bit of stardust. And, as if to justify the firetruck, one of the klieg lights caught a tree branch on fire.

For those on tenterhooks, Shirley Weisgerber won the costume contest. Meanwhile, Spencer Tracy sent a telegram to the governor expressing his regrets for being unable to attend due to his “continued employment in Hollywood on Edison the Man.”

There was to be a sequel to Northwest Passage, but the studio never got around to making it. The movie won the Academy Award for best cinematography in 1941, in spite of the glowing green costumes.

From left to right, Robert Young, Spencer Tracy, and Walter Brennan commiserate beneath a ponderosa pine on the set of Northwest Passage near McCall. The world premiere for the movie was held at the Pinney Theater in Boise.

From left to right, Robert Young, Spencer Tracy, and Walter Brennan commiserate beneath a ponderosa pine on the set of Northwest Passage near McCall. The world premiere for the movie was held at the Pinney Theater in Boise.

Published on September 18, 2022 04:00