Rick Just's Blog, page 69

February 6, 2023

The American Dog Derby (tap to read)

Dog sleds were about the only speedy means of transportation around the turn of the century when snow blanketed the Island Park area in the winter. Humans, being human, turned transportation into a contest. Dogs, being dogs, went along with it, probably with a lot of eager huffing and some brag-barking of their own.

One of the oldest dog sled races in the country takes place each February in Ashton. The American Dog Derby is billed as “The oldest all-American dog sled race.” It celebrated its centennial in January 2017. You already know, if you’ve done your math, that the first race took place in 1917. Wikipedia throws a little water on the “oldest” claim by pointing out that there was a dog sled race in Truckee, California during the winter of 1914-15. The Ashton race seems to have the longest history in any case, though there were a few years it wasn’t run.

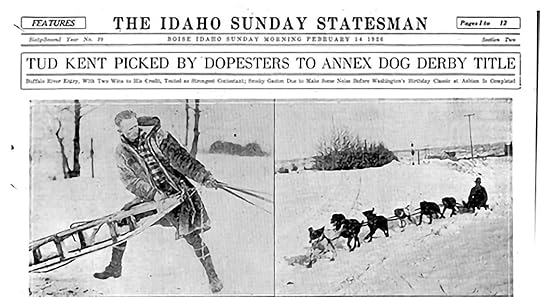

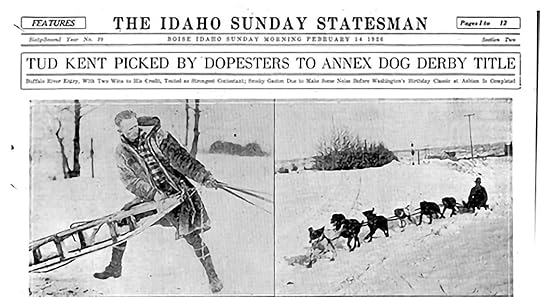

The race merited full-page coverage on February 14, 1926, in a story that was capped off with this observation: “Ashton is on the way to the dogs again, as it goes annually, when for a day the little town on the fringe of the Targhee forest is the sport capital of the nation while its famous dog derby is run.”

Tud Kent, who won the first American Dog Derby in 1917, was favored to win the 1926 race, according to the Statesman (below).

This year's Derby will be held on February 18. For details, check out their Facebook Page.

One of the oldest dog sled races in the country takes place each February in Ashton. The American Dog Derby is billed as “The oldest all-American dog sled race.” It celebrated its centennial in January 2017. You already know, if you’ve done your math, that the first race took place in 1917. Wikipedia throws a little water on the “oldest” claim by pointing out that there was a dog sled race in Truckee, California during the winter of 1914-15. The Ashton race seems to have the longest history in any case, though there were a few years it wasn’t run.

The race merited full-page coverage on February 14, 1926, in a story that was capped off with this observation: “Ashton is on the way to the dogs again, as it goes annually, when for a day the little town on the fringe of the Targhee forest is the sport capital of the nation while its famous dog derby is run.”

Tud Kent, who won the first American Dog Derby in 1917, was favored to win the 1926 race, according to the Statesman (below).

This year's Derby will be held on February 18. For details, check out their Facebook Page.

Published on February 06, 2023 04:00

February 5, 2023

The First Slave in Idaho (tap to read)

Idaho was not involved in the Civil War, though one can find vestiges of that sad chapter of American history in towns and places named by proponents of one side or another. Atlanta and Yankee Fork are two examples.

But slavery played a part in earliest Idaho history.

Lewis and Clark, those great and fortunate explorers who first came into what would later become Idaho brought slavery with them. William Clark owned an African-American man named York. Clark’s father had given the explorer the man when both were boys.

By all accounts York was treated well on the expedition and seemed to find some measure of freedom there, trusted to reconnoiter on his own. He was also given an equal vote with other members of the Corps of Discovery.

York’s taste of freedom turned bitter when he did not receive pay at the end of the journey, as others did. He asked for his freedom, but Clark at refused to grant it. Accounts are not in agreement about what happened to York in the ensuing years. Clark eventually gave him his freedom, but what York did with it is still unclear. One account has him living out his life as an honored member of the Crow tribe.

York has received some recognition. Wikipedia lists two books about him written by Frank X. Walker. A play and an opera were also written about York. Books about the Corps of Discovery often mention him admiringly. A statue of York (pictured) stands in Louisville, Kentucky.

York deserved better from Clark. But, both were men of their times and to expect Clark to behave differently would be to expect him to transcend his upbringing and the life he was accustomed to living.

I can’t resist adding a footnote to this story of a famous slave. York was not the only member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition who had been enslaved. Definitions can be tricky, but Sacagawea (or Sacajawea, if you prefer) was taken from her family at about age 12 in a battle between her Lemhi Shoshone Tribe and members of the Hidatsa Tribe. She was sold, or claimed as a gambling prize, by Toussaint Charbonneau and became his wife at age 13.

Statue of York in Louisville, KY.

Statue of York in Louisville, KY.

But slavery played a part in earliest Idaho history.

Lewis and Clark, those great and fortunate explorers who first came into what would later become Idaho brought slavery with them. William Clark owned an African-American man named York. Clark’s father had given the explorer the man when both were boys.

By all accounts York was treated well on the expedition and seemed to find some measure of freedom there, trusted to reconnoiter on his own. He was also given an equal vote with other members of the Corps of Discovery.

York’s taste of freedom turned bitter when he did not receive pay at the end of the journey, as others did. He asked for his freedom, but Clark at refused to grant it. Accounts are not in agreement about what happened to York in the ensuing years. Clark eventually gave him his freedom, but what York did with it is still unclear. One account has him living out his life as an honored member of the Crow tribe.

York has received some recognition. Wikipedia lists two books about him written by Frank X. Walker. A play and an opera were also written about York. Books about the Corps of Discovery often mention him admiringly. A statue of York (pictured) stands in Louisville, Kentucky.

York deserved better from Clark. But, both were men of their times and to expect Clark to behave differently would be to expect him to transcend his upbringing and the life he was accustomed to living.

I can’t resist adding a footnote to this story of a famous slave. York was not the only member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition who had been enslaved. Definitions can be tricky, but Sacagawea (or Sacajawea, if you prefer) was taken from her family at about age 12 in a battle between her Lemhi Shoshone Tribe and members of the Hidatsa Tribe. She was sold, or claimed as a gambling prize, by Toussaint Charbonneau and became his wife at age 13.

Statue of York in Louisville, KY.

Statue of York in Louisville, KY.

Published on February 05, 2023 05:14

February 4, 2023

Whacky Wallace (tap to read)

Wallace, Idaho is a quirky little town that you need to visit, if you haven’t done so. Quirky? Visit the Oasis Bordello Museum if you’re not convinced of its quirkiness. Or check out the stoplight in a coffin.

For years Wallace had the only stoplight on Interstate 90 anywhere along its 3,100-mile coast-to-coast length. A bypass took care of that little issue in 1991. The town held a funeral for the stoplight, complete with a horse-drawn hearse and solemn bagpipes. It now rests in its casket at the Wallace Mining Museum.

We’ve already got two museums in this story, so let’s round it out with one more. The Northern Pacific Railroad Museum is in the beautiful brick building that once served as the town’s railroad depot.

Wallace is proud to claim movie star Lana Turner as one of its own. And the town itself starred in a movie, once. Dante’s Peak, a 1997 film featuring Peirce Brosnan and Linda Hamilton, asked you to really, really suspend your disbelief for an hour and 48 minutes. It was shot in and around Wallace.

Wallace wasn’t always Wallace. It started out as an area called Cedar Swamp, because it was located in a swamp. With cedars all around it. Then, in 1884, it became Placer Center because of all the placer mining going on. When it finally incorporated, they named the town after Colonel W. R. Wallace, the owner of much of the town property and a member of the first city council. Not so quirky, that.

But, there’s the whole “Center of the Universe” thing. In 2004, the mayor gave a proclamation that read in part:

“I, Ron Garitone, Mayor of Wallace, Idaho, and all of its subjects, and being of sound body and mind, do hereby solemnly declare and proclaim Wallace to be the Center of the Universe.

“Thanks to the newly discovered science of 'Probalism' - specifically probalistic modeling, pioneered by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Health and Welfare, and peer-reviewed by La Cosa Nostra and the Flat Earth Society - we were further able to pinpoint the exact center within the Center of the Universe; to wit: a sewer access cover slightly off-center from the intersection of Bank and Sixth Streets.

“Upon discovering this desecration of the Center of the Universe, we proceeded forthwith to remove said manhole cover and replace it with this fine Monument, directing all who come upon it to the Four Corners of the Universe, these being the Bunker Hill, the Sunshine, the Lucky Friday and the Galena Mines.”

The photo of the manhole cover certainly proves that Wallace, center of the universe or not, is certifiably quirky.

For years Wallace had the only stoplight on Interstate 90 anywhere along its 3,100-mile coast-to-coast length. A bypass took care of that little issue in 1991. The town held a funeral for the stoplight, complete with a horse-drawn hearse and solemn bagpipes. It now rests in its casket at the Wallace Mining Museum.

We’ve already got two museums in this story, so let’s round it out with one more. The Northern Pacific Railroad Museum is in the beautiful brick building that once served as the town’s railroad depot.

Wallace is proud to claim movie star Lana Turner as one of its own. And the town itself starred in a movie, once. Dante’s Peak, a 1997 film featuring Peirce Brosnan and Linda Hamilton, asked you to really, really suspend your disbelief for an hour and 48 minutes. It was shot in and around Wallace.

Wallace wasn’t always Wallace. It started out as an area called Cedar Swamp, because it was located in a swamp. With cedars all around it. Then, in 1884, it became Placer Center because of all the placer mining going on. When it finally incorporated, they named the town after Colonel W. R. Wallace, the owner of much of the town property and a member of the first city council. Not so quirky, that.

But, there’s the whole “Center of the Universe” thing. In 2004, the mayor gave a proclamation that read in part:

“I, Ron Garitone, Mayor of Wallace, Idaho, and all of its subjects, and being of sound body and mind, do hereby solemnly declare and proclaim Wallace to be the Center of the Universe.

“Thanks to the newly discovered science of 'Probalism' - specifically probalistic modeling, pioneered by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Health and Welfare, and peer-reviewed by La Cosa Nostra and the Flat Earth Society - we were further able to pinpoint the exact center within the Center of the Universe; to wit: a sewer access cover slightly off-center from the intersection of Bank and Sixth Streets.

“Upon discovering this desecration of the Center of the Universe, we proceeded forthwith to remove said manhole cover and replace it with this fine Monument, directing all who come upon it to the Four Corners of the Universe, these being the Bunker Hill, the Sunshine, the Lucky Friday and the Galena Mines.”

The photo of the manhole cover certainly proves that Wallace, center of the universe or not, is certifiably quirky.

Published on February 04, 2023 04:00

February 3, 2023

Lesser Idaho (tap to read)

Idaho’s boundaries changed over the years before statehood with little say from Idaho residents. In 1881, some residents tried to have their say.

The Territorial House of Representatives sent a memorial to Congress asking that they lop off the northern part of the territory and give it to Washington Territory. Why?

In the words of the memorial, “That all that portion of said territory embraced and included within the boundaries hereinafter set forth and constituting what is known as north Idaho, is so situated in relation to the south and southeast portion of the territory, as to render their political union impracticable for the reason that nature has divided them by a high and rugged range of mountains over which there is no road except as what will admit of passage of riding or pack animal, and this only for about six months of the year. The remaining six months the snow is so deep as to cut off all communication except by telegraph or circuitous route through Washington territory, a distance of about 500 miles.”

That sentiment echoed down through the years, when In 1970, during his first successful run for governor, Cecil D. Andrus famously called Highway 95 a “goat trail.”

The 1881 memorial went on: “Politically, the two sections are united; socially, commercially and geographically, they never can be. We therefore respectfully but urgently pray that when the territory of Washington is admitted into the union that all that portion of Idaho hereinafter described be attached and made a part of the state of Washington.”

The vote was 15 to 8 in favor of the memorial. As is often the case with such missives sent by territories or states, Congress ignored it.

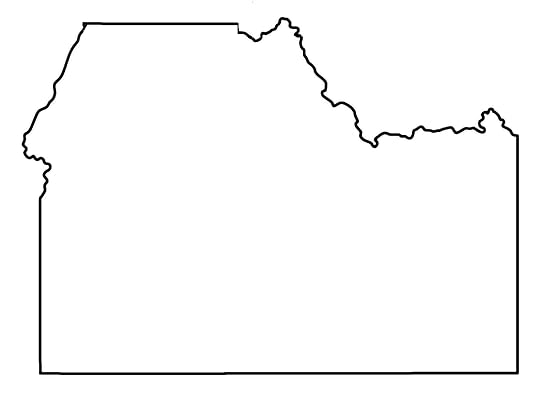

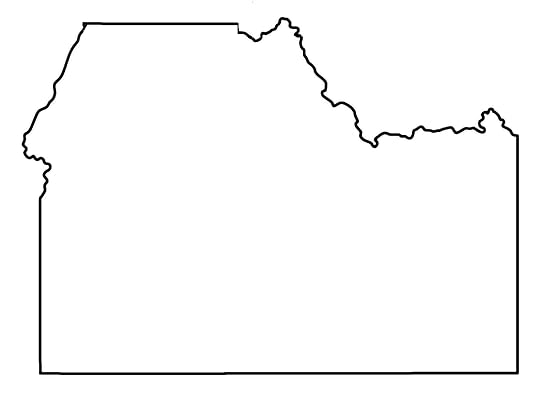

People get Iowa and Idaho confused now. Imagine their bewilderment of Idaho's shape looked like this.

People get Iowa and Idaho confused now. Imagine their bewilderment of Idaho's shape looked like this.

The Territorial House of Representatives sent a memorial to Congress asking that they lop off the northern part of the territory and give it to Washington Territory. Why?

In the words of the memorial, “That all that portion of said territory embraced and included within the boundaries hereinafter set forth and constituting what is known as north Idaho, is so situated in relation to the south and southeast portion of the territory, as to render their political union impracticable for the reason that nature has divided them by a high and rugged range of mountains over which there is no road except as what will admit of passage of riding or pack animal, and this only for about six months of the year. The remaining six months the snow is so deep as to cut off all communication except by telegraph or circuitous route through Washington territory, a distance of about 500 miles.”

That sentiment echoed down through the years, when In 1970, during his first successful run for governor, Cecil D. Andrus famously called Highway 95 a “goat trail.”

The 1881 memorial went on: “Politically, the two sections are united; socially, commercially and geographically, they never can be. We therefore respectfully but urgently pray that when the territory of Washington is admitted into the union that all that portion of Idaho hereinafter described be attached and made a part of the state of Washington.”

The vote was 15 to 8 in favor of the memorial. As is often the case with such missives sent by territories or states, Congress ignored it.

People get Iowa and Idaho confused now. Imagine their bewilderment of Idaho's shape looked like this.

People get Iowa and Idaho confused now. Imagine their bewilderment of Idaho's shape looked like this.

Published on February 03, 2023 04:00

February 2, 2023

The Yankee Fork Dredge (tap to read)

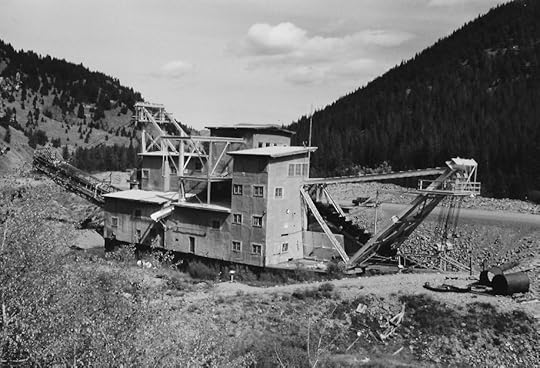

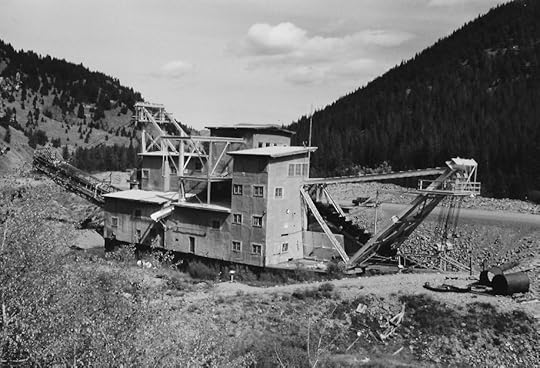

The Yankee Fork Dredge is probably the best-preserved machine of its kind in the lower 48. Built in 1940 by Bucyrus Erie, the machine was designed to pull out the $11 million worth of gold that allegedly sat there for the taking in the gravel bed along a 5 ½ mile stretch of Yankee Fork Creek just before it flows into the Salmon River.

The Silas Mason Company of New York assembled the dredge on site mostly from parts hauled in by train to Mackay, then by truck to the claim. The pontoons that let the dredge float were manufactured in Boise, as was the superstructure.

The dredge weighs 988 tons, and is 112 feet long by 54 feet wide by 64 feet high. Each of the 71 buckets that make up the mouth of the digging chain can hold 8 cubic feet and themselves weigh a little over a ton. Imagine a chain saw with iron buckets linked together instead of a chain. That’s what bit into the creek bottom relentlessly driven by twin 350 hp diesel engines. The gravel fed into a conveyor system inside the dredge where the gold was sifted out. A swinging arm behind the machine spit out gravel in neat arcs producing rock hills in its wake, the ridges of which look like the backbone of a buried dragon.

The dredge worked the claim off and on until 1952. The J.R. Simplot Company bought the operation in 1949.

The dredge didn’t find $11 million in gold, only about $1.5 million. It cost about that to operate, so turning the creek upside down didn’t pay much of a dividend.

Still, the dredge is an interesting place to visit. Regular tours are conducted Memorial Day Weekend through Labor Day. Google it for details.

The Forest Service is planning some ambitious restoration work in the valley, which is the best news the stream has had since 1952.

The photo of the dredge is courtesy of Mario Delisio who, sadly, passed away a few days ago.

The Silas Mason Company of New York assembled the dredge on site mostly from parts hauled in by train to Mackay, then by truck to the claim. The pontoons that let the dredge float were manufactured in Boise, as was the superstructure.

The dredge weighs 988 tons, and is 112 feet long by 54 feet wide by 64 feet high. Each of the 71 buckets that make up the mouth of the digging chain can hold 8 cubic feet and themselves weigh a little over a ton. Imagine a chain saw with iron buckets linked together instead of a chain. That’s what bit into the creek bottom relentlessly driven by twin 350 hp diesel engines. The gravel fed into a conveyor system inside the dredge where the gold was sifted out. A swinging arm behind the machine spit out gravel in neat arcs producing rock hills in its wake, the ridges of which look like the backbone of a buried dragon.

The dredge worked the claim off and on until 1952. The J.R. Simplot Company bought the operation in 1949.

The dredge didn’t find $11 million in gold, only about $1.5 million. It cost about that to operate, so turning the creek upside down didn’t pay much of a dividend.

Still, the dredge is an interesting place to visit. Regular tours are conducted Memorial Day Weekend through Labor Day. Google it for details.

The Forest Service is planning some ambitious restoration work in the valley, which is the best news the stream has had since 1952.

The photo of the dredge is courtesy of Mario Delisio who, sadly, passed away a few days ago.

Published on February 02, 2023 04:00

February 1, 2023

Roosevelt Lake (Tap to read)

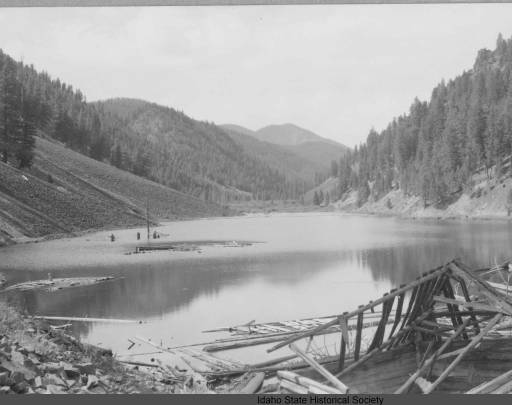

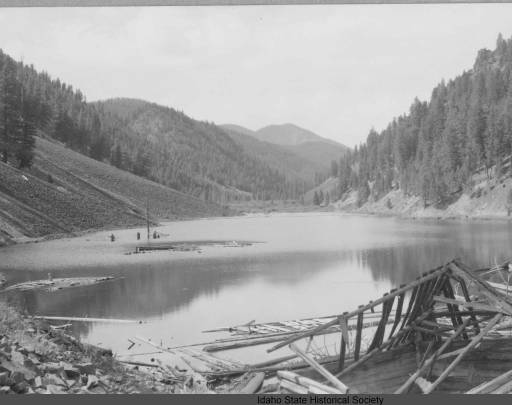

Named for Teddy Roosevelt, the mining town of Roosevelt, Idaho is a footnote in Idaho’s history of disasters. The ramshackle town, east of Yellowpine, started in 1902 when miners first came to the Thunder Mountain District on rumors of a major gold find. The Dewey Mine’s production fell far short of the rumors. It operated for five years, closing in 1907.

A few obstinate miners hung on, but Roosevelt was all but a ghost town in the spring of 1909 when “disaster” struck. It was the slow-moving kind of disaster that occurred without human casualty. A landslide three miles long and 200 feet high plugged Monumental Creek, backing up water and flooding the town. It took a couple of days for the slide to happen, so getting out of its way wasn’t much of a feat. The valley filled in slowly, causing most of the buildings in the town to float.

Mining may have contributed to the slide, but the area was prone to such events and heavy rains were probably the main cause.

There was a bright side to the slide. That mud, moved free of charge by the forces of nature, made some areas easier to mine.

For years the remains of the town bobbed around in Roosevelt Lake. Nowadays you may find a few boards here and there along the shoreline, a reminder of a slow-moving disaster.

The photo of floating buildings on Roosevelt Lake is from the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection. It was taken sometime after 1909.

A few obstinate miners hung on, but Roosevelt was all but a ghost town in the spring of 1909 when “disaster” struck. It was the slow-moving kind of disaster that occurred without human casualty. A landslide three miles long and 200 feet high plugged Monumental Creek, backing up water and flooding the town. It took a couple of days for the slide to happen, so getting out of its way wasn’t much of a feat. The valley filled in slowly, causing most of the buildings in the town to float.

Mining may have contributed to the slide, but the area was prone to such events and heavy rains were probably the main cause.

There was a bright side to the slide. That mud, moved free of charge by the forces of nature, made some areas easier to mine.

For years the remains of the town bobbed around in Roosevelt Lake. Nowadays you may find a few boards here and there along the shoreline, a reminder of a slow-moving disaster.

The photo of floating buildings on Roosevelt Lake is from the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection. It was taken sometime after 1909.

Published on February 01, 2023 04:50

January 30, 2023

The Fidler Murders (tap to read)

From time to time, I get questions from readers about an incident in Idaho history. I rarely get a question from out of the country, but I did receive one from the UK a few months back. Linda Bowditch was seeking information about an ancestor, Frederick Charles Cursons. About all she knew was that he was murdered in Placerville in 1865.

I was busy running for office at the time but circled around to the request again recently.

June 7, 1865, was a memorable day in Placerville. That was the day of four deaths, one accident, and three murders. It’s the murders that are remembered, including that of Fredrick Charles Cursons.

Cursons, an Englishman, was employed as a fiddler at Magnolia Hall in Idaho City. He had left his wife in Victoria, BC, to find his fortune in Idaho. It is unclear whether he hoped to find gold or make it with his music.

His musical endeavors ended when the Magnolia burned that June, taking much of Idaho City with it. Like many who found their beds turned to ashes, Cursons trekked to Placerville, looking for a place to live. He found a man named Larry Moulton there who had some skill with a banjo.

On Saturday evening, June 3, the pair set out for Centerville on foot, hoping to make a little coin there with their instruments. On their way, Cursons and Moulton stopped to chat and enjoy a drink of water with the gatekeeper at the toll gate.

Not long after they left, the two apparently encountered a robbery either in progress or just completed. George Wilson, a young miner, had been shot in the head at close range. The fiddler and the banjo player turned to run, only to feel bullets in their back.

So, three murders with robbery apparently the original motive—Wilson’s pockets were turned inside out, and his watch had been cut from its fob.

Deputy Sheriff Maloney gathered men by the dozens for a manhunt. Anger turned to rage, and there was talk of a lynching. Nearly a week later, three men, Charles Kimball, Ned Elwood, and one called Wiliams, who had an alias of Welch and another of Buck, were arrested. The guy with aliases was the prime suspect in the murder. He was wanted in California for a stage robbery and escape.

The men of the manhunt turned into a mob ready to string up Williams/Welch/Buck, but deputies escorted the prisoners out of town to the territorial jail in Idaho City.

The mob cooled down as the weeks passed while those in jail waited for the next sitting of the grand jury. When the jury finally convened, they found scant evidence against the three incarcerated men and set them free.

Musicians Cursons and Moulton were buried in the Placerville Cemetery without markers. Their killers, and the killers of George Wilson, were never brought to justice.

I was busy running for office at the time but circled around to the request again recently.

June 7, 1865, was a memorable day in Placerville. That was the day of four deaths, one accident, and three murders. It’s the murders that are remembered, including that of Fredrick Charles Cursons.

Cursons, an Englishman, was employed as a fiddler at Magnolia Hall in Idaho City. He had left his wife in Victoria, BC, to find his fortune in Idaho. It is unclear whether he hoped to find gold or make it with his music.

His musical endeavors ended when the Magnolia burned that June, taking much of Idaho City with it. Like many who found their beds turned to ashes, Cursons trekked to Placerville, looking for a place to live. He found a man named Larry Moulton there who had some skill with a banjo.

On Saturday evening, June 3, the pair set out for Centerville on foot, hoping to make a little coin there with their instruments. On their way, Cursons and Moulton stopped to chat and enjoy a drink of water with the gatekeeper at the toll gate.

Not long after they left, the two apparently encountered a robbery either in progress or just completed. George Wilson, a young miner, had been shot in the head at close range. The fiddler and the banjo player turned to run, only to feel bullets in their back.

So, three murders with robbery apparently the original motive—Wilson’s pockets were turned inside out, and his watch had been cut from its fob.

Deputy Sheriff Maloney gathered men by the dozens for a manhunt. Anger turned to rage, and there was talk of a lynching. Nearly a week later, three men, Charles Kimball, Ned Elwood, and one called Wiliams, who had an alias of Welch and another of Buck, were arrested. The guy with aliases was the prime suspect in the murder. He was wanted in California for a stage robbery and escape.

The men of the manhunt turned into a mob ready to string up Williams/Welch/Buck, but deputies escorted the prisoners out of town to the territorial jail in Idaho City.

The mob cooled down as the weeks passed while those in jail waited for the next sitting of the grand jury. When the jury finally convened, they found scant evidence against the three incarcerated men and set them free.

Musicians Cursons and Moulton were buried in the Placerville Cemetery without markers. Their killers, and the killers of George Wilson, were never brought to justice.

Published on January 30, 2023 04:00

January 29, 2023

Boise in Hot Water (tap to read)

We talk a lot about alternative energy these days. You’ll find solar panels on my house and a plug-in car in my garage. But alternative energy is not new in Idaho.

In 1890 well drillers found 177 degree water pure enough for domestic use near the state penitentiary in Boise.

The water was first used to create a hot water resort. Boise's beautiful natatorium was opened in May of 1892 to the delight of swimmers and soakers . That same year,

C.W. Moore decided to put the hot water to another use. He piped it into his home to provide heat. The system worked well, and H.B. Eastman, who had built a mansion nearby, began to use geothermal heat. Others along the street saw the advantage, and a community heat line was built, using wooden pipe at first. It cost two dollars a month to heat an eight-room house--three dollars would heat the larger ones along Warm Springs Avenue in Boise...You've probably already figured out why the street was named that.

The system is still in use today, and it's been expanded to include more homes, apartments, and businesses.

Boise City Hall, the Ada County Courthouse, Idaho's statehouse, and much of Boise State University are on the geothermal system. It was the first system of its kind in the United States.

In 1890 well drillers found 177 degree water pure enough for domestic use near the state penitentiary in Boise.

The water was first used to create a hot water resort. Boise's beautiful natatorium was opened in May of 1892 to the delight of swimmers and soakers . That same year,

C.W. Moore decided to put the hot water to another use. He piped it into his home to provide heat. The system worked well, and H.B. Eastman, who had built a mansion nearby, began to use geothermal heat. Others along the street saw the advantage, and a community heat line was built, using wooden pipe at first. It cost two dollars a month to heat an eight-room house--three dollars would heat the larger ones along Warm Springs Avenue in Boise...You've probably already figured out why the street was named that.

The system is still in use today, and it's been expanded to include more homes, apartments, and businesses.

Boise City Hall, the Ada County Courthouse, Idaho's statehouse, and much of Boise State University are on the geothermal system. It was the first system of its kind in the United States.

Published on January 29, 2023 04:00

January 28, 2023

Farragut Drill Halls (tap to read)

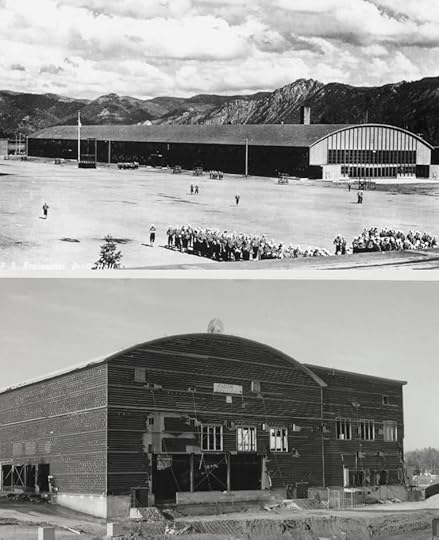

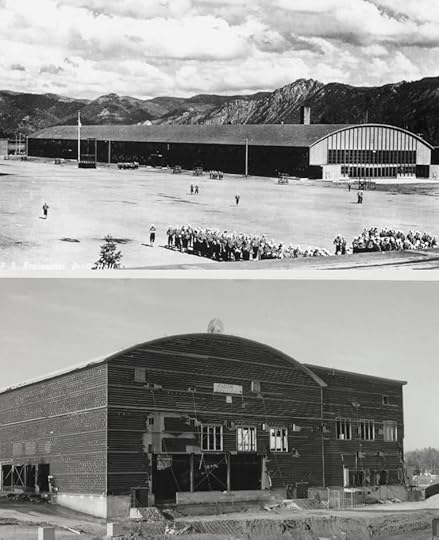

Farragut Naval Training Station, which is now Farragut State Park had some unique buildings.

Each of the training camps had drill fields called “grinders” where the recruits marched. The huge regimental drill hall in the background of the top photo allowed training during all kinds of weather. They were billed as the largest clear span (without posts) structures in the world at that time. This particular structure is probably the drill hall at Camp Bennion.

At least two of the drill halls found life after the Navy. One found a new usein Spokane for many years as a Costco. It is still there, just off the Division street exit, and now houses a Goodwill warehouse.

Another of the drill halls was donated to the University of Denver, disassembled, and reassembled on the DU campus in 1948-49. It was used as a hockey arena that fans called “the old barn.” It stood on campus for nearly 50 years.

Above, one of the drill halls at the Farragut Naval Training Station. Below, the drill hall that was converted into a hockey arena in Denver. It was being torn down in this shot.

Above, one of the drill halls at the Farragut Naval Training Station. Below, the drill hall that was converted into a hockey arena in Denver. It was being torn down in this shot.

Each of the training camps had drill fields called “grinders” where the recruits marched. The huge regimental drill hall in the background of the top photo allowed training during all kinds of weather. They were billed as the largest clear span (without posts) structures in the world at that time. This particular structure is probably the drill hall at Camp Bennion.

At least two of the drill halls found life after the Navy. One found a new usein Spokane for many years as a Costco. It is still there, just off the Division street exit, and now houses a Goodwill warehouse.

Another of the drill halls was donated to the University of Denver, disassembled, and reassembled on the DU campus in 1948-49. It was used as a hockey arena that fans called “the old barn.” It stood on campus for nearly 50 years.

Above, one of the drill halls at the Farragut Naval Training Station. Below, the drill hall that was converted into a hockey arena in Denver. It was being torn down in this shot.

Above, one of the drill halls at the Farragut Naval Training Station. Below, the drill hall that was converted into a hockey arena in Denver. It was being torn down in this shot.

Published on January 28, 2023 04:00

January 27, 2023

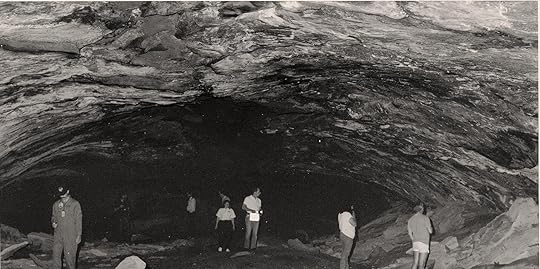

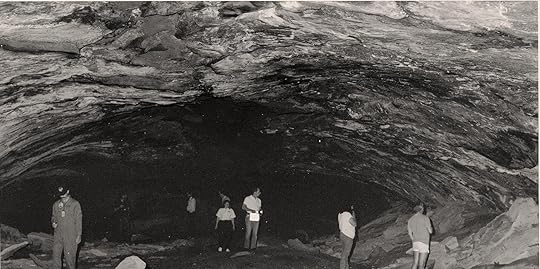

Aviator Cave (tap to read)

Spelunkers keep the location of most caves they know about secret. That’s to keep people who don’t have the proper training from hurting themselves and sometimes to protect cave environments.

There’s one cave in Idaho that gets a lot of extra protection. It’s called Aviator’s Cave and it is within the boundaries of the Idaho National Laboratory, which is in the desert between Idaho Falls and Arco. Since 1949 “the Site,” as it’s known locally, has been a national center for nuclear research. Because of the sensitive nature of that research, security at INL is high. In 1985, that included regular helicopter flyovers to make sure people weren’t intentionally or accidentally trespassing on the federal property.

In January 1985 pilot Mike Atwood was flying about 500 feet above the desert on a routine patrol when he spotted what looked like smoke. Circling around to investigate, he saw that it wasn’t smoke, but steam coming from a visible rift in the lava rock below. Atwood assumed it was condensation from warm air inside a lava tube hitting the sub-zero air in the desert above. He noted the GPS coordinates of the site and paid no more attention to it.

Lava tubes are common there in the Idaho desert, not far from Craters of the Moon National Monument. The caves were formed some 30,000 years ago when rivers of lava spewed from the earth, flowing downhill like water. The lava rivers would cool from the outside first forming a tube or roof over the molten lava still flowing beneath. Like a garden hose when the water is shut off the molten lava would drain out leaving a cave sometimes miles long.

Three years after his winter encounter with the steam and in a warmer season, Atwood’s curiosity surfaced. He decided to go back and investigate the hole he had found. When he flew to the coordinates he’d noted, Atwood saw that the vegetation around the dark shadow on the ground was a brighter shade of green than the surrounding rabbit brush.

About 30 feet from the hole he found a spot clear enough to land. As he walked closer to the cave he began to see buffalo skulls and other bones inside. He climbed down to the opening, stooped to get inside, and found that the cave opened up once past the lip. Standing up was easy.

It was immediately obvious that Atwood was not the first person to stand in that cave, though he was the first to stand there in a very long time. Among the scattered bones were obsidian chips and projectile points, evidence that native hunters had at least stopped in the cave if they had not lived there. Atwood, and later others, found more fragile evidence of human occupation, including objects made from plant material and fur.

Today this important archeological site remains doubly protected by its status as a place of scientific study and a place within a modern well-protected place of scientific study. Aviator’s Cave was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2009.

The INL photo shows Shoshone-Bannock tribal members and archeologists exploring the cave.

There’s one cave in Idaho that gets a lot of extra protection. It’s called Aviator’s Cave and it is within the boundaries of the Idaho National Laboratory, which is in the desert between Idaho Falls and Arco. Since 1949 “the Site,” as it’s known locally, has been a national center for nuclear research. Because of the sensitive nature of that research, security at INL is high. In 1985, that included regular helicopter flyovers to make sure people weren’t intentionally or accidentally trespassing on the federal property.

In January 1985 pilot Mike Atwood was flying about 500 feet above the desert on a routine patrol when he spotted what looked like smoke. Circling around to investigate, he saw that it wasn’t smoke, but steam coming from a visible rift in the lava rock below. Atwood assumed it was condensation from warm air inside a lava tube hitting the sub-zero air in the desert above. He noted the GPS coordinates of the site and paid no more attention to it.

Lava tubes are common there in the Idaho desert, not far from Craters of the Moon National Monument. The caves were formed some 30,000 years ago when rivers of lava spewed from the earth, flowing downhill like water. The lava rivers would cool from the outside first forming a tube or roof over the molten lava still flowing beneath. Like a garden hose when the water is shut off the molten lava would drain out leaving a cave sometimes miles long.

Three years after his winter encounter with the steam and in a warmer season, Atwood’s curiosity surfaced. He decided to go back and investigate the hole he had found. When he flew to the coordinates he’d noted, Atwood saw that the vegetation around the dark shadow on the ground was a brighter shade of green than the surrounding rabbit brush.

About 30 feet from the hole he found a spot clear enough to land. As he walked closer to the cave he began to see buffalo skulls and other bones inside. He climbed down to the opening, stooped to get inside, and found that the cave opened up once past the lip. Standing up was easy.

It was immediately obvious that Atwood was not the first person to stand in that cave, though he was the first to stand there in a very long time. Among the scattered bones were obsidian chips and projectile points, evidence that native hunters had at least stopped in the cave if they had not lived there. Atwood, and later others, found more fragile evidence of human occupation, including objects made from plant material and fur.

Today this important archeological site remains doubly protected by its status as a place of scientific study and a place within a modern well-protected place of scientific study. Aviator’s Cave was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2009.

The INL photo shows Shoshone-Bannock tribal members and archeologists exploring the cave.

Published on January 27, 2023 04:00