Rick Just's Blog, page 67

February 26, 2023

Bunn and Guns (tap to read)

Was there gunplay between two Idaho elected officials? The officials in question were Territorial Governor William M. Bunn and perennial politician Fred T. Dubois.

First, a little about Bunn. He was born in Philadelphia, served as a Union soldier, and was wounded and captured in the Civil War. After the war he became a wealthy newspaperman. He put some of his wealth into mining claims in Arizona and Idaho. As a businessman, he thought it might be convenient to live near one of those claims. He lobbied to be named Territorial Governor of Arizona, without success. In 1884 he had better luck with a new president, Chester Arthur, who named him governor of Idaho territory.

Bunn loved the social life. In Philadelphia he was an active speaker at events and was known for his flamboyant dress. That reputation followed him to Idaho, where he became known as the “dude governor.”

But that gunplay.

Some 40 years after the fact—if it was a fact—S.H. Hays, a onetime Idaho attorney general, recounted a story that involved a gun, Bunn, and (maybe) Fred T. Dubois, who was the US Marshal for Idaho Territory when the incident did or did not take place.

According to Hays, the gunplay happened shortly after both houses of the Territorial Legislature passed the Mormon Test Oath bill in 1884. Voters would be required to sign an oath that stated they were not practitioners of polygamy, nor were they members of any organization that ever believed in polygamy.

The bill hit the Governor’s desk and languished there. Bunn was not a fan of polygamy, but he wasn’t inclined to sign such a bill.

Enter H.W. (Kentucky) Smith of Blackfoot, George Gorton of Soda Springs, and US Marshal Fred T. Dubois. Literally. They entered Bunn’s office, demanding that he sign the legislation. As Hays told it, Smith pulled a gun on the Governor, saying, “Governor, you will not leave this room alive unless you sign that bill and sign it at once.” Whether that account is accurate or not, Governor Bunn signed the bill.

Dubois had another version of the story, again, according to Hays. As Dubois told it, “Kentucky” Smith did threaten the Governor at gunpoint, but he entered the office alone.

But wait, there’s more!

Dubois and Bunn were friends, which calls into question the first account of Hays as related above. At one point, Bunn gave Dubois the honor of naming Bingham County after one of his friends. Bunn also appointed a slate of officers for the newly named county that Dubois had submitted. Almost. Bunn refused to name one officer submitted by Dubois.

This resulted in a confrontation between the two men at the Overland Hotel in February of 1885. Dubois verbally attacked the Governor, and by some accounts, grabbed him by the collar, shouting into his face. By one account—that of Governor Bunn—Dubois threatened him with a gun. The Governor walked away from the confrontation without involving the local constabulary. Dubois was later said to have regretted the incident.

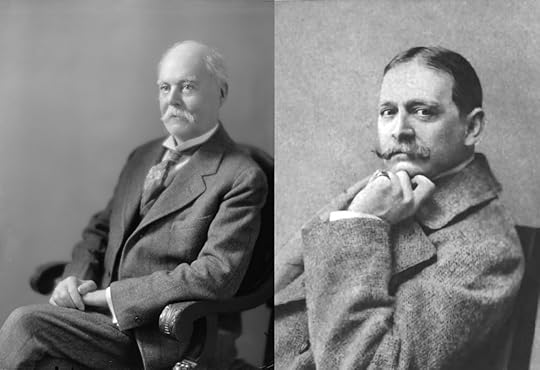

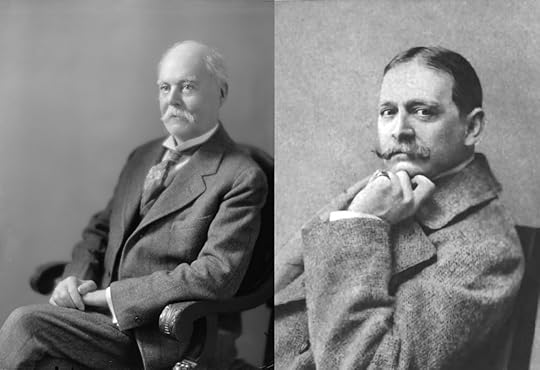

U.S. Senator Fred T. Dubois (left) and Idaho Territorial Governor William M. Bunn.

U.S. Senator Fred T. Dubois (left) and Idaho Territorial Governor William M. Bunn.

First, a little about Bunn. He was born in Philadelphia, served as a Union soldier, and was wounded and captured in the Civil War. After the war he became a wealthy newspaperman. He put some of his wealth into mining claims in Arizona and Idaho. As a businessman, he thought it might be convenient to live near one of those claims. He lobbied to be named Territorial Governor of Arizona, without success. In 1884 he had better luck with a new president, Chester Arthur, who named him governor of Idaho territory.

Bunn loved the social life. In Philadelphia he was an active speaker at events and was known for his flamboyant dress. That reputation followed him to Idaho, where he became known as the “dude governor.”

But that gunplay.

Some 40 years after the fact—if it was a fact—S.H. Hays, a onetime Idaho attorney general, recounted a story that involved a gun, Bunn, and (maybe) Fred T. Dubois, who was the US Marshal for Idaho Territory when the incident did or did not take place.

According to Hays, the gunplay happened shortly after both houses of the Territorial Legislature passed the Mormon Test Oath bill in 1884. Voters would be required to sign an oath that stated they were not practitioners of polygamy, nor were they members of any organization that ever believed in polygamy.

The bill hit the Governor’s desk and languished there. Bunn was not a fan of polygamy, but he wasn’t inclined to sign such a bill.

Enter H.W. (Kentucky) Smith of Blackfoot, George Gorton of Soda Springs, and US Marshal Fred T. Dubois. Literally. They entered Bunn’s office, demanding that he sign the legislation. As Hays told it, Smith pulled a gun on the Governor, saying, “Governor, you will not leave this room alive unless you sign that bill and sign it at once.” Whether that account is accurate or not, Governor Bunn signed the bill.

Dubois had another version of the story, again, according to Hays. As Dubois told it, “Kentucky” Smith did threaten the Governor at gunpoint, but he entered the office alone.

But wait, there’s more!

Dubois and Bunn were friends, which calls into question the first account of Hays as related above. At one point, Bunn gave Dubois the honor of naming Bingham County after one of his friends. Bunn also appointed a slate of officers for the newly named county that Dubois had submitted. Almost. Bunn refused to name one officer submitted by Dubois.

This resulted in a confrontation between the two men at the Overland Hotel in February of 1885. Dubois verbally attacked the Governor, and by some accounts, grabbed him by the collar, shouting into his face. By one account—that of Governor Bunn—Dubois threatened him with a gun. The Governor walked away from the confrontation without involving the local constabulary. Dubois was later said to have regretted the incident.

U.S. Senator Fred T. Dubois (left) and Idaho Territorial Governor William M. Bunn.

U.S. Senator Fred T. Dubois (left) and Idaho Territorial Governor William M. Bunn.

Published on February 26, 2023 04:00

February 25, 2023

A Famous Mail Pilot (tap to read)

There was no bigger celebrity in 1927 than Charles Lindbergh. On May 27 of that year the 25-year-old US Mail pilot had landed his single-engine plane, the Spirit of St. Louis in Paris to complete the first solo flight across the Atlantic. Then he took a real trip. The Daniel Guggenheim Fund sponsored a three-month flying tour that would take him to 48 states, where he would visit 92 cities and give 147 speeches.

Lindbergh landed in Boise on September 4 and was greeted by a crowd of 40,000 people. This picture, from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, shows, left to right, Leo J. Falk, Gov. H.C. Baldridge, and Boise Mayor Walter F. Hanson with Lindbergh. The Spirit of St. Lewis is in the background.

The Idaho Statesman described Lindy’s departure thusly: “Lindy made a graceful take-off, just as he had landed the day before. He circled over the city, then headed northeast over the hills, rising higher and higher into the clouds until the Spirit of St. Louis appeared a little speck in the sky. Lindy was gone.”

It was his only stop in Idaho on the tour, but folks in the northern part of the state had a chance to see him and his famous plane land in Spokane on September 12.

Lindbergh landed in Boise on September 4 and was greeted by a crowd of 40,000 people. This picture, from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, shows, left to right, Leo J. Falk, Gov. H.C. Baldridge, and Boise Mayor Walter F. Hanson with Lindbergh. The Spirit of St. Lewis is in the background.

The Idaho Statesman described Lindy’s departure thusly: “Lindy made a graceful take-off, just as he had landed the day before. He circled over the city, then headed northeast over the hills, rising higher and higher into the clouds until the Spirit of St. Louis appeared a little speck in the sky. Lindy was gone.”

It was his only stop in Idaho on the tour, but folks in the northern part of the state had a chance to see him and his famous plane land in Spokane on September 12.

Published on February 25, 2023 04:00

February 24, 2023

The First Dog Across the Craters (tap to read)

Robert Limbert was a renaissance man of the West. He was a taxidermist, a hunting guide, an exhibit designer, an explorer, a writer, a photographer, and a tireless promoter of Idaho. Limbert was known as “Two-Gun Bob” when he was demonstrating his shooting skills for an audience. He built Redfish Lake Lodge, and on and on… More stories to follow, but today’s story is a little footnote (you’ll forgive me for that one, maybe?) in his most famous accomplishment.

Limbert was the man who explored what we now know as Craters of the Moon, and wrote the 25-page article that appeared in National Geographic in 1924 that intrigued the nation enough for Calvin Coolidge to proclaim it a national monument later that year. The article is available online and includes many of Lambert’s pictures that are still stunning today.

The National Geographic article documented a trip he and a friend took across the forbidding black desert. Here’s the cavalier way he described it:

“One morning in May W. L. Cole and I, both of Boise, Idaho, left Minidoka, packing on our backs bedding. an aluminum cook outfit, a 5 x 7 camera and tripod, binoculars, and supplies sufficient for two weeks, making a total pack each of 55 pounds.”

And now, to the footnote:

“We also took with us an Airedale terrier for a camp dog. This was a mistake, for after three days' travel his feet were worn raw and bleeding. In some places it was necessary to carry him or sit and wait while he picked his way across.”

The dog of the adventure was not named Scout, or Hercules, or Intrepid. He was named Teddy. He was mentioned once more in the article: “The dog was in terrible shape also: it was pitiful to watch him as he hobbled after us.”

Left at what Limbert wrote for National Geographic you might think he just watched his companion animal suffer. He did much more than that for the Airedale. He cut up clothing to make booties for the dog, then did it again when they wore out.

The three of them—two men and a dog—covered 80 miles in 17 days.

The picture below, which appeared in National Geographic, is “a lava spout in Vermilion Canyon.” Teddy is resting to the right while Limbert and Cole pose for the picture. Limbert was the photographer. He was in most of the pictures he took of the expedition, which were apparently shot using a timer or remote shutter release. Limbert was a tireless promoter of Idaho, and of Robert Limbert, for which we should be glad. The photo comes from the Robert Limbert papers, Boise State University Library, Special Collections and Archives.

Limbert was the man who explored what we now know as Craters of the Moon, and wrote the 25-page article that appeared in National Geographic in 1924 that intrigued the nation enough for Calvin Coolidge to proclaim it a national monument later that year. The article is available online and includes many of Lambert’s pictures that are still stunning today.

The National Geographic article documented a trip he and a friend took across the forbidding black desert. Here’s the cavalier way he described it:

“One morning in May W. L. Cole and I, both of Boise, Idaho, left Minidoka, packing on our backs bedding. an aluminum cook outfit, a 5 x 7 camera and tripod, binoculars, and supplies sufficient for two weeks, making a total pack each of 55 pounds.”

And now, to the footnote:

“We also took with us an Airedale terrier for a camp dog. This was a mistake, for after three days' travel his feet were worn raw and bleeding. In some places it was necessary to carry him or sit and wait while he picked his way across.”

The dog of the adventure was not named Scout, or Hercules, or Intrepid. He was named Teddy. He was mentioned once more in the article: “The dog was in terrible shape also: it was pitiful to watch him as he hobbled after us.”

Left at what Limbert wrote for National Geographic you might think he just watched his companion animal suffer. He did much more than that for the Airedale. He cut up clothing to make booties for the dog, then did it again when they wore out.

The three of them—two men and a dog—covered 80 miles in 17 days.

The picture below, which appeared in National Geographic, is “a lava spout in Vermilion Canyon.” Teddy is resting to the right while Limbert and Cole pose for the picture. Limbert was the photographer. He was in most of the pictures he took of the expedition, which were apparently shot using a timer or remote shutter release. Limbert was a tireless promoter of Idaho, and of Robert Limbert, for which we should be glad. The photo comes from the Robert Limbert papers, Boise State University Library, Special Collections and Archives.

Published on February 24, 2023 04:00

February 23, 2023

An Idaho Automobile (tap to read)

In the early days of automobiles many entrepreneurial mechanics tried building their own. A few even started their own brands, some of which live on today. Many towns in the Northwest had their own automobiles being built in small assembly plants in the teens and twenties. Lost brands such as the Totem, the Spokane, the Tilikum, and the Seattle were the result. By the 1930s most of those upstarts had disappeared. Then, in 1975 Don Stinebaugh of Post Falls, Idaho decided to build a car.

Stinebaugh was an inventor with at least 48 patents to his name. He’d invented a snowmobile engine that made him a fair amount of money, for one. His cars grew out of his tinkering with off highway vehicles. He built several all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) that people liked, including tandem axel models that pre-dated today’s side-by-side utility task vehicles (UTVs) . Had he continued down that (non) road, he might have done well with his vehicles. He got distracted, though, when people started to encourage him to convert his ATVs for street use.

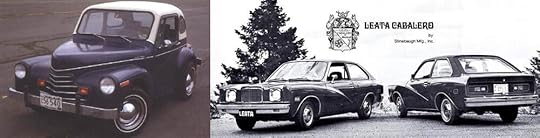

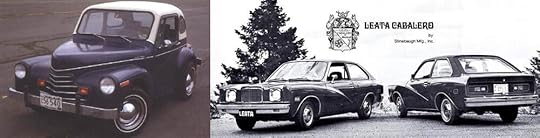

Cutting to the chase, the 1975 Leata was born from those early off-road vehicles. It had a hand-laid fiberglass body, an 83-HP Pinto engine, and a diamond tuft interior that would not be out-of-place in a hot rod. The first Leatas looked a bit like a British Morris (left in the photo) with a continental kit on the back. Stinebaugh built about 20 of them. One was returned because it went too fast for the owner.

There was no 1976 Leata, but Sinebaugh wasn’t through. He brought out the Leata Cabalero in 1977 (right in the photo). It came in several models, including a convertible and a pickup. The Cabalero was basically a Chevette with a custom body. Where the original Leata could claim snappy performance, the 1977 models were sluggish. The automotive press panned them. Stinebaugh made and sold about 70 of them, then closed up shop.

Leata’s were not aesthetically pleasing. They filled no real automotive need a Pinto couldn’t fill for less money. Still, my hat is off to Mr. Stinebaugh for following his dream and creating an Idaho original.

Stinebaugh was an inventor with at least 48 patents to his name. He’d invented a snowmobile engine that made him a fair amount of money, for one. His cars grew out of his tinkering with off highway vehicles. He built several all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) that people liked, including tandem axel models that pre-dated today’s side-by-side utility task vehicles (UTVs) . Had he continued down that (non) road, he might have done well with his vehicles. He got distracted, though, when people started to encourage him to convert his ATVs for street use.

Cutting to the chase, the 1975 Leata was born from those early off-road vehicles. It had a hand-laid fiberglass body, an 83-HP Pinto engine, and a diamond tuft interior that would not be out-of-place in a hot rod. The first Leatas looked a bit like a British Morris (left in the photo) with a continental kit on the back. Stinebaugh built about 20 of them. One was returned because it went too fast for the owner.

There was no 1976 Leata, but Sinebaugh wasn’t through. He brought out the Leata Cabalero in 1977 (right in the photo). It came in several models, including a convertible and a pickup. The Cabalero was basically a Chevette with a custom body. Where the original Leata could claim snappy performance, the 1977 models were sluggish. The automotive press panned them. Stinebaugh made and sold about 70 of them, then closed up shop.

Leata’s were not aesthetically pleasing. They filled no real automotive need a Pinto couldn’t fill for less money. Still, my hat is off to Mr. Stinebaugh for following his dream and creating an Idaho original.

Published on February 23, 2023 04:00

February 22, 2023

A Famous Horse Thief? (tap to read)

Most of the stories I relate through Speaking of Idaho are well-known and can be corroborated by more than one source. Sometimes I run across a story that is of some interest, but is little more than hearsay. Today, presented as hearsay, is a story about Kit Carson.

Christopher Houston “Kit” Carson was well known in his own time through dime novels that told often exaggerated stories of the West. He was an army officer, a mountain man, and famously a guide for John C. Fremont. Nowhere in his resume does it list “horse thief.”

However, such a tale was told about the man in the May 20, 1923 edition of the Idaho Statesman. The article was part of a continuing series of stories told by the son of Captain Stanton G. Fisher. The elder Fisher had over the years been an Indian trader, chief of scouts, and the Indian Agent at Fort Hall. The time period when he held various posts and titles seems to have been from the late 1860s into the 1890s. He was involved in what some call the Nez Perce War.

Fisher’s son heard from his father that Kit Carson and Jim Beckworth, a freed slave who was a mulatto and himself a well-known mountain man, stole a string of 6 or 8 horses and mules from someone near Fort Hall. The teller of the tale was careful to say that stealing horses at that (unspecified) time was not necessarily looked upon with great disfavor if one didn’t steal them from a friend or neighbor.

The tale-teller said the owner of the small herd offered a beaver trap worth $16 for every animal returned to him. Jim Bridger, ANOTHER well-known mountain man who was also at the fort at that time, told a little Frenchman named Meachau LeClair about the reward offer. LeClair and a young Mexican named Thomas Lavatte set out to earn those beaver traps.

They caught up with Carson and Beckworth somewhere outside of Soda Springs. The pair waited until well into the night to approach the camp of the two men. They first silenced a bell tied around the neck of one horse, then quietly led the herd away without waking anyone. Not relishing the idea of being overtaken on their way back to Fort Hall by Carson and Beckworth, the men decided to steal the personal horses of the mountain men as well as the previously purloined herd. With some tense moments delivered courtesy of a growling guard dog, they were able to sneak the mounts away.

With Carson and Beckworth now on foot, LeClair and Lavatte pounded back to Fort Hall with the herd, which they would trade for the promised beaver traps. Along the way they stopped at Soda Springs where a store proprietor noticed the men had the Carson and Beckworth horses, to which the Frenchman allegedly said, in the third-hand telling of the tale, “Yas, you tell de man Kit Carson and de man Jim Beckworth dat de little Frenchman got his mool. You bet he no folly me.”

A grain of truth or a grain of salt? You be the judge.

Christopher Houston “Kit” Carson was well known in his own time through dime novels that told often exaggerated stories of the West. He was an army officer, a mountain man, and famously a guide for John C. Fremont. Nowhere in his resume does it list “horse thief.”

However, such a tale was told about the man in the May 20, 1923 edition of the Idaho Statesman. The article was part of a continuing series of stories told by the son of Captain Stanton G. Fisher. The elder Fisher had over the years been an Indian trader, chief of scouts, and the Indian Agent at Fort Hall. The time period when he held various posts and titles seems to have been from the late 1860s into the 1890s. He was involved in what some call the Nez Perce War.

Fisher’s son heard from his father that Kit Carson and Jim Beckworth, a freed slave who was a mulatto and himself a well-known mountain man, stole a string of 6 or 8 horses and mules from someone near Fort Hall. The teller of the tale was careful to say that stealing horses at that (unspecified) time was not necessarily looked upon with great disfavor if one didn’t steal them from a friend or neighbor.

The tale-teller said the owner of the small herd offered a beaver trap worth $16 for every animal returned to him. Jim Bridger, ANOTHER well-known mountain man who was also at the fort at that time, told a little Frenchman named Meachau LeClair about the reward offer. LeClair and a young Mexican named Thomas Lavatte set out to earn those beaver traps.

They caught up with Carson and Beckworth somewhere outside of Soda Springs. The pair waited until well into the night to approach the camp of the two men. They first silenced a bell tied around the neck of one horse, then quietly led the herd away without waking anyone. Not relishing the idea of being overtaken on their way back to Fort Hall by Carson and Beckworth, the men decided to steal the personal horses of the mountain men as well as the previously purloined herd. With some tense moments delivered courtesy of a growling guard dog, they were able to sneak the mounts away.

With Carson and Beckworth now on foot, LeClair and Lavatte pounded back to Fort Hall with the herd, which they would trade for the promised beaver traps. Along the way they stopped at Soda Springs where a store proprietor noticed the men had the Carson and Beckworth horses, to which the Frenchman allegedly said, in the third-hand telling of the tale, “Yas, you tell de man Kit Carson and de man Jim Beckworth dat de little Frenchman got his mool. You bet he no folly me.”

A grain of truth or a grain of salt? You be the judge.

Published on February 22, 2023 04:00

February 21, 2023

A Park Not A Park (tap to read)

Island Park is an area in Southeastern Idaho. It’s also a town within that area. It is not, however, a park. It isn’t an Island either.

When I say it isn’t a park, I’m talking about a government designation. Although there are two state parks within the Island Park area, Harriman and Henrys Lake. If you prefer a definition for “park” that broadly describes an area left largely in its natural state, you’re probably closer to the meaning those who named it had in mind. No, we don’t know who named it.

But, where did “island” come from? There are a few theories on this. In the earliest days of Idaho history there were apparently large mats of reeds and foliage floating on Henrys Lake. The name might have come from those. Another theory is that the “islands” referred to the open meadows in the otherwise heavily forested area. Yet a third theory is just the opposite. That one holds that the “islands” were islands of timber on the sagebrush plain. This is the one that Lalia Boone, author of Idaho Place Names , seems to prefer, since it came from Charlie Pond, one of the early lodge owners in the area.

So, we don’t have a definitive answer about where the name came from, but we know how the town of Island Park came about. In the late 1940s local lodge owners wanted to serve liquor to their customers. Idaho law allowed liquor licenses to be awarded only to establishments within an incorporated city. Changing the law would be difficult given strong religious influences on the Legislature, so the lodge owners created a town.

Island Park is unique in its dimensions, running some 33 miles end-to-end along US 20, but having a width of only 500 feet for much of its length. That weird shape pulled in the lodges and enough people to call it a town. Those people sometimes claim that they have the world’s longest “Main Street.” Whether that is true is probably open to debate. Maybe you’d be interested in a bar bet on it? That’s something you can do at certain establishments in the thriving community of Island Park.

When I say it isn’t a park, I’m talking about a government designation. Although there are two state parks within the Island Park area, Harriman and Henrys Lake. If you prefer a definition for “park” that broadly describes an area left largely in its natural state, you’re probably closer to the meaning those who named it had in mind. No, we don’t know who named it.

But, where did “island” come from? There are a few theories on this. In the earliest days of Idaho history there were apparently large mats of reeds and foliage floating on Henrys Lake. The name might have come from those. Another theory is that the “islands” referred to the open meadows in the otherwise heavily forested area. Yet a third theory is just the opposite. That one holds that the “islands” were islands of timber on the sagebrush plain. This is the one that Lalia Boone, author of Idaho Place Names , seems to prefer, since it came from Charlie Pond, one of the early lodge owners in the area.

So, we don’t have a definitive answer about where the name came from, but we know how the town of Island Park came about. In the late 1940s local lodge owners wanted to serve liquor to their customers. Idaho law allowed liquor licenses to be awarded only to establishments within an incorporated city. Changing the law would be difficult given strong religious influences on the Legislature, so the lodge owners created a town.

Island Park is unique in its dimensions, running some 33 miles end-to-end along US 20, but having a width of only 500 feet for much of its length. That weird shape pulled in the lodges and enough people to call it a town. Those people sometimes claim that they have the world’s longest “Main Street.” Whether that is true is probably open to debate. Maybe you’d be interested in a bar bet on it? That’s something you can do at certain establishments in the thriving community of Island Park.

Published on February 21, 2023 04:00

February 20, 2023

The Longed for Interurban (tap to read)

File this one under “You don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone.”

Boise had a streetcar system in 1890. They were built in many cities in the latter part of the 19th century as an efficient way to get people around town. Boise’s system soon became Treasure Valley’s system, with lines going in a 60-mile loop to Eagle, Star, Middleton, Caldwell, Nampa, Meridian and back to Boise.

It was popular for people to pack a picnic lunch and take the loop on a Sunday just for the fun of it. Spurs were extended from Caldwell to Wilder and Lake Lowell, as well.

Several companies ran portions of the system, which become generally known as the Interurban, over the years. The light rail trains were powered by electricity, so it shouldn’t come as a big surprise that Idaho Power Company ran the trains for a time.

Wouldn’t something like that be a wonderful resource today? So why weren’t “we” smart enough to save the Interurban?

First, you need to know that it wasn’t a public system. Several companies were involved over the years, each trying to make a profit, and none really succeeding. Yes, there’s a conspiracy theory that General Motors bought up all the light rail lines in the country and closed them down so that people would have to buy cars. And, yes, GM was convicted for plotting to monopolize transportation systems post-World War One. But it wasn’t GM that killed the systems. Not exactly. They were trying to make a profit from their National City Lines (which did NOT run a system in the Treasure Valley).

Cars did help kill the trollies when people began buying them. But it was buses that proved their demise. It was simply much cheaper to add a bus route and a few bus stop signs as cities grew. Quicker, too. Interurban tracks were taken out in some places as buses, and cars became the dominant forms of transportation. Often they didn’t even bother pulling up the tracks, instead they just paved over them like the useless relics they had become.

Ah, but, wouldn’t it be nice to hop on a smooth running trolley and watch the cities and sagebrush go by while you enjoyed an ice cream cone on a Sunday afternoon?

The photo is a packed Boise and Interurban car from 1910, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

For more on the Interurban, read Treasure Valley's Electric Railway by Barbara Perry Bauer and Elizabeth Jacox.

Boise had a streetcar system in 1890. They were built in many cities in the latter part of the 19th century as an efficient way to get people around town. Boise’s system soon became Treasure Valley’s system, with lines going in a 60-mile loop to Eagle, Star, Middleton, Caldwell, Nampa, Meridian and back to Boise.

It was popular for people to pack a picnic lunch and take the loop on a Sunday just for the fun of it. Spurs were extended from Caldwell to Wilder and Lake Lowell, as well.

Several companies ran portions of the system, which become generally known as the Interurban, over the years. The light rail trains were powered by electricity, so it shouldn’t come as a big surprise that Idaho Power Company ran the trains for a time.

Wouldn’t something like that be a wonderful resource today? So why weren’t “we” smart enough to save the Interurban?

First, you need to know that it wasn’t a public system. Several companies were involved over the years, each trying to make a profit, and none really succeeding. Yes, there’s a conspiracy theory that General Motors bought up all the light rail lines in the country and closed them down so that people would have to buy cars. And, yes, GM was convicted for plotting to monopolize transportation systems post-World War One. But it wasn’t GM that killed the systems. Not exactly. They were trying to make a profit from their National City Lines (which did NOT run a system in the Treasure Valley).

Cars did help kill the trollies when people began buying them. But it was buses that proved their demise. It was simply much cheaper to add a bus route and a few bus stop signs as cities grew. Quicker, too. Interurban tracks were taken out in some places as buses, and cars became the dominant forms of transportation. Often they didn’t even bother pulling up the tracks, instead they just paved over them like the useless relics they had become.

Ah, but, wouldn’t it be nice to hop on a smooth running trolley and watch the cities and sagebrush go by while you enjoyed an ice cream cone on a Sunday afternoon?

The photo is a packed Boise and Interurban car from 1910, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

For more on the Interurban, read Treasure Valley's Electric Railway by Barbara Perry Bauer and Elizabeth Jacox.

Published on February 20, 2023 07:00

February 19, 2023

"Children Cried in Horror" (tap to read)

The writing style of reporters from days gone by was often a little more colorful than we’re used to today. Take for example this dispatch from Grangeville as reported in the October 5, 1906 edition of the Idaho Statesman.

“Women fainted, men groaned, children cried out in horror, this afternoon when Aeronaut E. Yates fell a distance of 150 feet from his balloon to the sidewalk in the center of about 2000 people who were attending the Woodmen street fair, and watching the ascension. It is feared Yates will not recover, his injuries being principally internal. He fell from his balloon about 2 o’clock, and was unconscious for half an hour. The accident was due to Yates mistaking the wave of a man’s hand as the signal to descend. He was not sufficiently far from the ground to permit his parachute to open and he struck the sidewalk with a thud.”

Aeronauts made the news frequently in those days of balloon exhibitions. More often than one would hope the story ended something like this one.

The photo is of a much happier balloon event, and serves no purpose other than to tie a balloon picture to a balloon story. It shows Idaho’s Centennial Balloon just above the hills at Hells Gate State Park in 1990, 84 years and about 70 miles from the Grangeville incident.

“Women fainted, men groaned, children cried out in horror, this afternoon when Aeronaut E. Yates fell a distance of 150 feet from his balloon to the sidewalk in the center of about 2000 people who were attending the Woodmen street fair, and watching the ascension. It is feared Yates will not recover, his injuries being principally internal. He fell from his balloon about 2 o’clock, and was unconscious for half an hour. The accident was due to Yates mistaking the wave of a man’s hand as the signal to descend. He was not sufficiently far from the ground to permit his parachute to open and he struck the sidewalk with a thud.”

Aeronauts made the news frequently in those days of balloon exhibitions. More often than one would hope the story ended something like this one.

The photo is of a much happier balloon event, and serves no purpose other than to tie a balloon picture to a balloon story. It shows Idaho’s Centennial Balloon just above the hills at Hells Gate State Park in 1990, 84 years and about 70 miles from the Grangeville incident.

Published on February 19, 2023 04:00

February 18, 2023

Aviation in the Future (tap to read)

Local newspapers are all about local news nowadays, but that wasn’t always the case. In the late 1800s and early 1900s the local newspaper was often where one got all their news of the world. There were news cooperatives that local papers could subscribe to, including the Associated Press, which goes all the way back to 1846. Newspapers often traded subscriptions with each other so that stories told in one town could be retold in another, usually with attribution.

This came to mind when I ran across the March 4, 1914 edition of the Salmon Recorder. Page three was devoted to national news without a single word about Salmon. The story that caught my eye had been written upon the occasion of the ten-year anniversary of the Wright Brothers flight. It pointed out that Wilbur Wright flew his plane for 59 seconds that day at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. In just ten years the record for sustained flight was up to 14 hours and 1,300 miles.

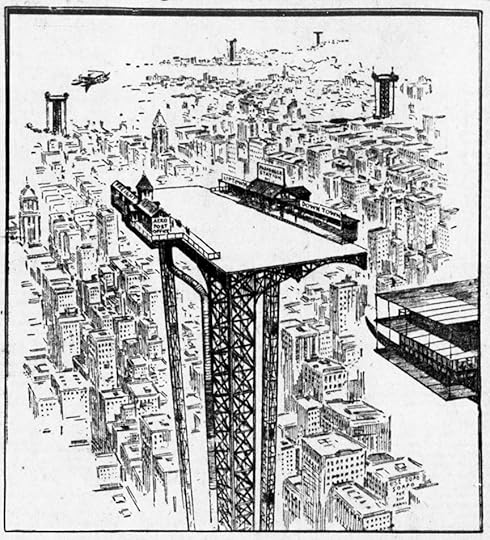

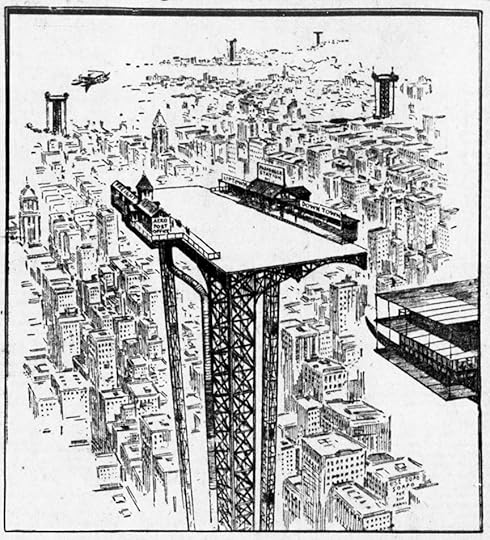

There were some predictions about what the future of “aeroplanes” would bring. An accompanying illustration, below, showed towering terminals in a city a little larger than Salmon could dream of becoming. There were about 1400 residents in 1914. Aeroplane users of the future were expected to take an elevator into the sky where they could catch an “uptown” or “downtown” plane to the destination of their choice.

Note to editors: If you stick your neck out and predict the future in print, the future will always come back to bite you.

This came to mind when I ran across the March 4, 1914 edition of the Salmon Recorder. Page three was devoted to national news without a single word about Salmon. The story that caught my eye had been written upon the occasion of the ten-year anniversary of the Wright Brothers flight. It pointed out that Wilbur Wright flew his plane for 59 seconds that day at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. In just ten years the record for sustained flight was up to 14 hours and 1,300 miles.

There were some predictions about what the future of “aeroplanes” would bring. An accompanying illustration, below, showed towering terminals in a city a little larger than Salmon could dream of becoming. There were about 1400 residents in 1914. Aeroplane users of the future were expected to take an elevator into the sky where they could catch an “uptown” or “downtown” plane to the destination of their choice.

Note to editors: If you stick your neck out and predict the future in print, the future will always come back to bite you.

Published on February 18, 2023 04:00

February 17, 2023

TV Celebrity Philo T. Farnsworth (tap to read)

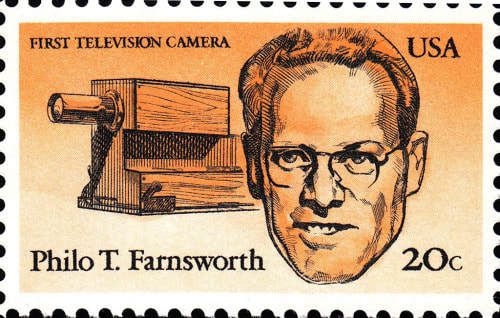

When Philo T. Farnsworth appeared on the 1950s TV show, "I've Got a Secret," he leaned over and whispered his secret in the game show host's ear. When the secret was flashed on the screen for the audience and viewers at home, there was a lot of oohing and ahhing. Philo Taylor Farnsworth's secret was amazing. He had invented television. Perhaps even more amazing, he had done it when he was a high school student in Rigby, Idaho in 1922.

As a high school student, Farnsworth had recently heard radio broadcasts for the first time, and he was enchanted with the medium. But, wouldn't it be great if you could send pictures through the air, too? The young inventor sketched his idea for the cathode ray tube on a high school blackboard. That tube became the basis for modern television.

At the age of 20, Farnsworth produced the first all-electronic television image. In 1930, he received the first patent for television.

The former Rigby High School student went on to invent the first simple electron microscope. He did pioneering work on radar, black light viewing, and the peaceful use of atomic energy.

In all, Philo T. Farnsworth held over 300 U.S. and foreign patents. In 1983 the inventor was honored with a postage stamp. He is one of only three Idahoans so honored.

You can visit the Farnsworth TV and Pioneer Museum in Rigby, if you’d like to learn more.

As a high school student, Farnsworth had recently heard radio broadcasts for the first time, and he was enchanted with the medium. But, wouldn't it be great if you could send pictures through the air, too? The young inventor sketched his idea for the cathode ray tube on a high school blackboard. That tube became the basis for modern television.

At the age of 20, Farnsworth produced the first all-electronic television image. In 1930, he received the first patent for television.

The former Rigby High School student went on to invent the first simple electron microscope. He did pioneering work on radar, black light viewing, and the peaceful use of atomic energy.

In all, Philo T. Farnsworth held over 300 U.S. and foreign patents. In 1983 the inventor was honored with a postage stamp. He is one of only three Idahoans so honored.

You can visit the Farnsworth TV and Pioneer Museum in Rigby, if you’d like to learn more.

Published on February 17, 2023 04:00