Patrick O'Shaughnessy's Blog, page 28

June 22, 2015

A Wealth of Common Sense

You are who you read. Those who read Ben Carlson’s writing are better for it. He is honest, succinct, and full of insight for investo rs of all stripes. I’ve never interviewed anyone or published a guest post, but today I make an exception because this guy has become such a valuable resource for investors, and we need to spread the word.

rs of all stripes. I’ve never interviewed anyone or published a guest post, but today I make an exception because this guy has become such a valuable resource for investors, and we need to spread the word.

Today, Ben’s book A Wealth of Common Sense hits shelves. I read an early copy and it is what you would expect from Ben: clean, engaging, and useful. It is a great book. Go buy it for yourself and for a few loved ones.

I sent Ben a list of questions, leaving out all that normal “why did you write this book” type stuff. I am sure he’s answered that question 50 times elsewhere. Here’s what he had to say:

What does your personal portfolio look like? How often do you rebalance or adjust it?

I utilize a barbell approach – my investment portfolio is all in stocks for long-term growth and then I have a liquid, online savings account for shorter-term goals. That will obviously change over time. My portfolio is full of index funds and ETFs and broadly diversified by geography, market cap and risk factors. I’m fairly slow to make changes. For example, for the past two years or so I’ve been slowly rebalancing from U.S. stocks to increase my foreign holdings because I probably had too much of a home bias in U.S. stocks. I don’t rebalance too often to allow short-term momentum to do its thing, but I will if certain investments get too far from their target weights.

How much exposure do you have to “factors” like value, momentum, and quality in your portfolio?

My portfolio is heavily tilted towards value stocks and I also like to diversify by market cap into small and mid caps. In some ways I view broad market indexes as something of a momentum play, but it’s obviously not a pure play. I’m a huge fan of the momentum factor, mainly for its diversification benefits. It’s also the least understood of the well-known risk factors. I’ve done a ton of work on momentum in my day job, but haven’t been too impressed with the retail products available. Most cost too much or they’re not tax efficient because it’s a higher turnover strategy. But some new ETFs should help take care of these problems, so I’ll be adding this factor to my portfolio in the future.

If you could design the perfect equity investment strategy, what would be its key features (or, if it already exists, what is it?)

I’ve given up looking for the perfect strategy because I’m not sure it exists. You can poke holes in every strategy out there based on historical data or potential future scenarios. I’ve learned to be wary of a perfect-looking back-test because the odds are that it would have been impossible to implement in real-time or too expensive based on the costs involved. The perfect strategy is the one you can live with over time without bailing out.

What financial technology company impresses you most and why?

I like what Betterment and Wealthfront are doing because they’ve made the onboarding process so simple for investors to sign up on their platforms. So many financial firms still make things much too difficult on their potential clients.

If you could recommend just one book that would be useful to investors at all levels of sophistication, what would it be and why?

Thinking, Fast & Slow by Daniel Kahneman. I feel one of the most important aspects of a sound investment approach is the ability to make good decisions. I don’t think it’s possible to make good decisions without an understanding of human psychology and this book gives the reader a master’s degree on human nature.

What is your biggest shortcoming as an investor?

I probably try to multi-task too often and pay attention to everything that’s going on. It’s amazing how going away for a week on a vacation makes you realize how pointless every headline or market development is, but when I’m sitting at my desk all day I can’t help myself.

What do you wish you were better at?

Predicting the future…

OK, based on my previous answer, I wish I was better at focusing my attention on a single task, instead of trying to pay attention to everything else that’s going on in the markets.

What do you think is the fairest fee structure for active managers? What do you think fees will look like in 10 years? Will it still be based on AUM? Can performance fees be justified?

I’ve thought a lot about this over the years and I’m not sure there is an optimal fee structure. You could look at every fee structure out there today and make a case that it creates a misalignment of interests. I think it all comes down how comfortable investors are with the firms they choose to work with and whether or not they will likely use poor judgement with the inherent incentives involved.

Professional investors have been clamoring for changes for a number of years now, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the fee structure looks fairly similar to the way it does today. It takes a long time to see changes in these things. Although there’s a good possibility expense ratios will be lower in 10 years. Performance fees can be justified in certain situations, but I’m not sure it makes sense when you combine it with a 2% management fee. I wouldn’t mind seeing active funds set up with index fund expense ratios but performance fees on top of that.

In your day job, you speak to many active managers. Two questions: what are you most sick of hearing? What is the most unique thing a manager has said to you?

“Here’s how we’re differentiated” gets said by nearly everyone. I liked the Peter Thiel quote from Zero to One where he said, “The most contrarian thing of all is not to oppose the crowd but to think for yourself.”

It’s nothing ground-breaking, but I’m always pleasantly surprised when a portfolio manager is willing to admit their flaws. The best investors are often humble and unassuming. Many firms try to promise their clients the world and then have to backtrack if and when things go wrong. Of course, many clients invite this on themselves in the due diligence process when they basically say, “We have the money…now impress us.” So I always find it unique when a manager is able to discuss their process in terms of reducing behavioral errors and which environments it does and does not work very well. These days it’s also unique when an investment firm refrains from mentioning the Fed.

Is it possible to identify the small group of active managers who will outperform in the future or is it just a fool’s game, the triumph of hope over experience?

It’s possible, but the key word here is small — the number of people or teams who can do it is small and as you increase the number of managers used you lower your chances of outperforming, so I don’t think it’s sustainable with a large number of managers or funds. The reason it’s so difficult is that career risk is ever present. Not only do you have to be able to identify a process that will work over the long-term, but you also have to give yourself a long enough runway to allow it to work. Very few investors are willing to sit through periods of underperformance without making a change, mainly because of outside pressure to hit short-term benchmarks.

There are teams who can do this, but the number of professionally-managed funds who are trying to outperform is much larger than the number who actually will outperform. The competition may be more intense now than it’s ever been.

If you could ask your ten favorite investors one question, what would it be?

What’s your secret to a happy life outside of the markets?

June 17, 2015

Exploring One of the Greatest Investment Passages Ever Written

Here’s how to find amazing quotes and passages: find great writers, and then find the passages that they reference. Having followed this plan quite a lot, I’ve noticed that many of the best writers are J.M. Keynes junkies. The man was as quotable as they come. One great writer, George Goodman (aka “Adam Smith”), put the following passage (“one of the most acute passages ever”) towards the end of his great book The Money Game, with the descriptor, “That is the way it is, and no one has ever said it better.” Let’s explore this illuminating, timeless summary of the investing game.

It might have been supposed that competition between expert professionals, possessing judgment and knowledge beyond that of the average private investor, would correct the vagaries of the ignorant individual left to himself. It happens, however, that the energies and skill of the professional investor and speculator are mainly occupied otherwise. For most of these persons are, in fact, largely concerned, not with making superior long-term forecasts of the probable yield of an investment over its whole life, but with foreseeing changes in the conventional basis of valuation a short time ahead of the general public. They are concerned, not with what an investment is really worth to a man who buys it “for keeps,” but with what the market will value it at, under the influence of mass psychology, three months or a year hence. Moreover, this behavior is not the outcome of a wrong-headed propensity. For it is not sensible to pay 25 for an investment of which you believe the prospective yield to justify a value of 30, if you also believe that the market will value it at 20 three months hence. Thus the professional investor is forced to concern himself with the anticipation of impending changes, in the news or in the atmosphere, of the kind by which experience shows that the mass psychology of the market is most influenced … (thus) there is no such thing as liquidity of investment for the community as a whole. The social object of skilled investment should be to defeat the dark forces of time and ignorance which envelop our future. The actual, private object of the most skilled investment today is “to beat the gun,” as the Americans so well express it, to outwit the crowd, and to pass the bad, or depreciating, half-crown to the other fellow. This battle of wits to anticipate the basis of conventional valuation a few months hence, rather than the prospective yield of an investment over a long term of years, does not even require gulls amongst the public to feed the maws of the professional; it can be played by the professionals amongst themselves. Nor is it necessary that anyone should keep his simple faith in the conventional basis of valuation having any genuine long-term validity. For it is, so to speak, a game of Snap, of Old Maid, of Musical Chairs—a pastime in which he is victor who says Snap neither too soon nor too late, who passes the Old Maid to his neighbour before the game is over, who secures a chair for himself when the music stops. These games can be played with zest and enjoyment, though all the players know that it is the Old Maid which is circulating, or that when the music stops some of the players will find themselves unseated.

There is so much here. Some quick hits:

A study of psychology, game theory, and market incentive structures is probably the most valuable use of your time if you want to be an active investor. Every active investor should focus on two things: finding/building an investment strategy that consistently identifies different opportunities (I know, I know, everyone says they are a contrarian—but still), and finding limits to arbitrage. This is why I recently wondered if it is now smart to be dumb.

Time horizon is critical. Short time frame? Momentum works very well, until it occasionally crashes and burns. Medium horizon? Value works very well because the market overdoes it at extremes and, on average, corrects those mistakes slowly (as Jim Grant said, the key to successful investing is to have everyone agree with you…later). Long/Indefinite horizon? I have no idea.

Maybe buying and holding forever (“for keeps”) is best, and then quality matters greatly, but replicating the Buffett approach is extremely difficult and probably requires a hefty dose of luck—it’s either hard or impossible to consistently predict long term outcomes in a complex adaptive system like the stock market. Again, Keynes says it better than I can: “The outstanding fact is the extreme precariousness of the basis of knowledge on which our estimates of prospective yield have to be made. Our knowledge of the factors which will govern the yield of an investment some years hence is usually very slight and often negligible. If we speak frankly, we have to admit that our basis of knowledge for estimating the yield ten years hence of a railway, a copper mine, a textile factory, the goodwill of a patent medicine, an Atlantic liner, a building in the City of London amounts to little and sometimes to nothing; or even five years hence. In fact, those who seriously attempt to make any such estimate are often so much in the minority that their behaviour does not govern the market.”

I’ll follow Goodman’s lead and leave you with another Keynes passage, also from his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money:

If the reader interjects that there must surely be large profits to be gained from the other players in the long run by a skilled individual who, unperturbed by the prevailing pastime, continues to purchase investments on the best genuine long-term expectations he can frame, he must be answered, first of all, that there are, indeed, such serious-minded individuals and that it makes a vast difference to an investment market whether or not they predominate in their influence over the game-players. But we must also add that there are several factors which jeopardise the predominance of such individuals in modern investment markets. Investment based on genuine long-term expectation is so difficult to-day as to be scarcely practicable. He who attempts it must surely lead much more laborious days and run greater risks than he who tries to guess better than the crowd how the crowd will behave; and, given equal intelligence, he may make more disastrous mistakes. There is no clear evidence from experience that the investment policy which is socially advantageous coincides with that which is most profitable. It needs more intelligence to defeat the forces of time and our ignorance of the future than to beat the gun.

God damn was he good.

June 16, 2015

Buyback Extravaganza

When important people on Wall Street and Capitol Hill are actively criticizing an aspect of corporate America, we’d better take notice. Share buybacks—the open market repurchase of a company’s shares by the company itself—have been under a lot of fire. The amount spent on buybacks is matching records, and that money would be better spend on capital expenditures, research & development, higher employee wages, and so on. So goes the now vitriolic anti-buyback argument.

What follows is a sober-as-possible assessment of where we stand with buybacks today.

Who is doing them and in what true quantity (raw dollar amount is a useless measure of buyback intensity)?

Do firms conducting buyback programs do so at exactly the wrong time (which is the current consensus), or are some firms quite good at timing the repurchase of their shares at fairly cheap relative prices?

Can share repurchase programs be a useful tool for active stock selection?

First things first: the companies under consideration are all U.S. listed/domiciled public companies with a market cap higher than the average (this is about 750 stocks or so, with market caps higher than roughly $8 billion today). Most buybacks are conducted by larger firms, and larger firms represent a cleaner dataset for this analysis. Smaller firms tend to be raising more capital from stakeholders, whereas larger firms tend to be returning more capital to stakeholders.

Cash Spent on Buybacks

Sure enough, we are reaching peak dollar amounts on a rolling 12-month basis.

But this is a useless number. All that matters is the amount spent on buybacks relative to the size of the overall market. Here is the buyback yield (total buybacks over last 12 months divided by total current market cap) for the U.S. large cap market, in both gross (cash spent on buybacks only) and net (cash spent on buybacks minus cash raised through any share issuance). Net is the number that really matters. The yield of 2.1% is high but well below the early 2008 high of 3.6%.

The fairly smooth line at the market level gets much messier at the sector level. I have to separate it into a few graphs to be readable, so here break it out by cyclical and defensive sectors. Defensive first:

Note some goofiness. Telecom is just a few companies really so it’s all over the place. Utilities tend to be net issuers. Energy as a whole had one of the highest buyback yields in 2008 at more than 6% (whoops).

Even more extreme readings through history for cyclical sectors. The yield for Consumer Discretionary stocks nearly hit 8% at one point, and the yield on financials spiked negative due to massive share issuance during the hellhole of 2008/09.

So Does Any of This Matter For Investors?

Interesting stuff, but we have to remember that these charts are just aggregated data. What is more relevant for active investors is: have ongoing shareholders (those who don’t sell their shares back to the company as it is repurchasing shares) benefitted from the companies’ decision to buyback stock?

Here is the key point: the magnitude of buybacks is very important. A company which repurchases 10% of its shares in one year is much different than a company which repurchases 2%. Arguably, a higher buyback yield indicates higher conviction from the company in question that their shares are attractively value and/or they are being more disciplined in their allocation of capital (i.e. are spending a lot on buybacks due to a lack of attractive opportunities elsewhere). I know plenty of people who would take the opposite side of that argument. Luckily, we have data!

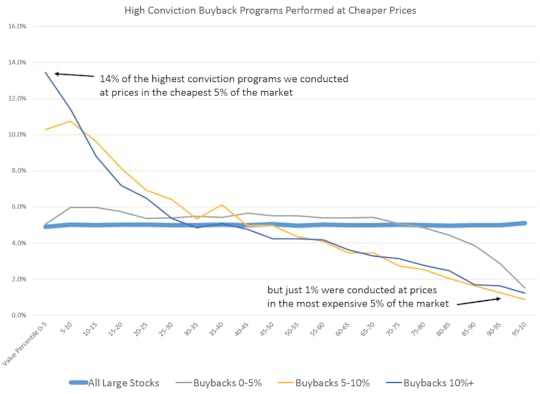

Let’s look at the valuations at which companies have tended to repurchase shares at varying levels of buyback conviction. I’ll define low conviction as buyback yields between zero and five. Higher conviction means buyback yields between five and ten, and highest conviction means buyback yields of ten or higher.

Next we calculate an independent valuation for each company on each date relative to all other large U.S. stocks (which gives us a percentile score 0-100, with 0 being cheapest). For this valuation, we use four factors: price-to-sales, price-to-earnings, free cash flow-to-enterprise value, and EBITDA-to-enterprise value. These factors are equally weighted in the calculation.

Armed with these two things, 1) companies bucketed by buyback yield and 2) relative valuation percentiles, we can see if companies tend to buy back stock at good relative prices or bad ones.

To see how the distributions look historically, let’s first compare the distribution of all large stocks by valuation percentile vs. companies that are issuing shares (negative buyback yield). The x-axis is the valuation percentile buckets, so anything on the far left, in the 0-5 bucket, is in the cheapest five percent of the market. The y-axis is the percent of the companies falling in each bucket.

As you would suspect, the line for large stocks is flat: our relative value score 0 to 100 is equally distributed. But the result for share issuers is different. What this chart shows you is that on average, companies tend to slightly mistime share issuance—issuers have tended to be a little more expensive that other stocks in the market, this the skew towards the right (expensive) side of the distribution.

Now let’s look at the same thing for varying levels of buyback conviction.

You see the reverse: that companies with higher conviction (5-10, and 10+ percent yields) have tended to, on average, buyback stock at much cheaper relative prices. In fact, the average valuation percentile is 33 or so (so in the cheapest third), when from a random sample you’d expect the average score to be 50. Companies buying back between 0-5% of their shares (which is far more common, and makes up most of the dollars spent on buybacks) don’t display nearly as strong a pattern.

Buybacks may not be well timed in aggregate, but they have been timed well (at least, timed at cheaper relative prices) by companies with the highest conviction buyback programs. These can get lost in the shuffle because, on average, the cash spent on buybacks by these high conviction firms represent 22% of the total cash being spend on buybacks (gross).

Debt Matters

So are companies just issuing debt at low rates to finance share buybacks? Obviously it’s hard to say for sure. We can, however, test two different stock selection factors to estimate the impact on debt issuance or reduction in the most recent low interest rate environment.

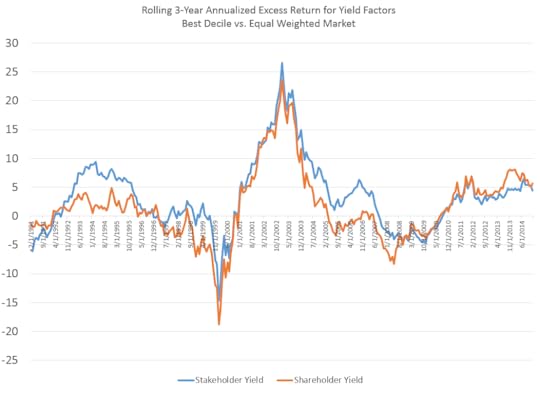

We create two “shareholder yield” factors.

First take all cash spent on buybacks, subtract all cash raised from issuance, plus all cash spent on dividends. Then divide by current market cap for a “yield.” (net bb + divs))/market cap

Same as above, but now include net debt issuance/reduction, where companies paying down debt in addition to dividends and buybacks are ranked more favorably. (net bb + divs + net debt reduction)/market cap

We will call the first “shareholder yield” and the second “stakeholder yield” because debt is part of the equation. For these purposes, I am excluding financial stocks, because they use of debt is so much different from other sectors. In practice, you’d want to make sector specific adjustments to measurements of debt, but here I am just keeping things pretty simple.

Now let’s run at typical test of the returns for stocks in the top decile by these two yield factors. Both have been strong selection factors. Here is the rolling 3-year excess return earned since the late 1980’s by the highest “yielding” stocks.

On this scale it looks quite normal, so let’s look at just the difference between the two.

Across the entire period, Stakeholder yield has delivered a return of 14.5%, and Shareholder yield a return of 12.4%. This means that investors have been rewarded more by buying stocks which are both paying back shareholders AND reducing their debt. But that script has flipped somewhat after the global financial crisis, arguably because interest rates have been so low. Companies taking advantage of cheap money in recent years seem to have had an edge.

Conclusion

So, here is what we know:

Buybacks, in dollar terms, are high and have historically peaked at inopportune times, but the raw dollars don’t matter as much as the yield, which remains much lower than the late 2007/early 2008 high.

Buybacks are very different across time and across sectors, so painting them with just a market-wide brush isn’t fair.

The level of conviction in a buyback program (measured as a percent of shares repurchased) has a relationship to relative cheapness: high conviction buyback programs have been conducted at solid prices on average through the last few decades.

Buying companies with the highest buyback/shareholder yields has been a great investing strategy.

For most of our history, you’d also want to favor companies reducing debt, but less so during the recent low interest rate environment.

What else would you like to know about buybacks?

June 12, 2015

Using the Price to Sales Ratio

Price to sales is a very simple valuation ratio. It has the tendency to bias you towards lower margin and higher debt companies, all else equal, but it has still been a very effect measure of cheapness and a fine standalone factor for stock selection. Having explored the history of the ratio, let’s now turn to its measurement and usefulness in stock selection.

Here is a summary of the finding which will be explored below:

The largest return spread for best minus worst is in the simplest factor: plain old price-to-sales, un-adjusted for debt, sector, or size.

Sales-to-enterprise value—which controls for the bias towards high debt companies—works well.

Adjusting for sector does not materially change results, but it does control for large potential sector exposures that result from using the un-adjusted factor.

Like all value factors, the various iterations of price-to-sales work better in small stocks than in large stocks.

Our universe is all U.S. stocks trading at market caps greater than $200MM back to 1963. Everything is rebalanced as usual, on a rolling annual basis (although the signal can last longer than 12 months).

Here are some high level results.

Broken value investing record: the factors have worked! Here is how sales to price has done in rolling five year periods (versus equal weighted benchmarks of all stocks and large stocks). The factor has worked at roughly the same times in the large and all stock universes.

One notable feature of this factor is that the best decile is 70% industrial and consumer stocks on average.

As we did with price-to-book, we can adjust the calculation of price to sales to be relative only to other stocks in the same sector, which results in the following balanced allocations and results.

Finally, we saw that price to sales biases you towards companies with higher debt and lower margins. One way to adjust for the debt bias is to use the sales to enterprise value multiple instead. Here are the results for that method (quite similar).

And here are the results through time comparing sales-to-price and sales-to-enterprise value. I overlay the trend in interest rates not to show that one causes the other but merely that the declining relative advantage of Sales/EV over Sales/Price has coincided with a steady decline in interest rates.

The bottom line is that like all other value factors, price to sales works. Be aware of the biases inherent in the factor (and ideally use it in combination with other factors, we will get there). If value works by helping to identify stocks for which the market has grown overly pessimistic, we should be careful not to invest in a company that looks cheap (i.e. out-of-favor) but is really just a lower margin business that uses more debt than others.

June 11, 2015

Mass Movements in Money Management

Wouldn’t it be great to create a mass movement that improved lives and/or created a successful business? Like so many phenomena which recur through history, mass movements have a sort of formula. This formula is a great tool for sales, for innovation, for creating communities, and for building new categories within an existing business. There are several perfect examples in money management and finance today—the move towards passive indexing and smart beta being two of the most prominent. Each fits cleanly into the formula for a mass movement.

So what is the secret recipe that can catalyze a population to adopt some new set of beliefs, use new products and services, and make collective changes for the better or for the worse?

Our guide is the fantastic book The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements by Eric Hoffer. Hoffer outlines all of the key components for a mass movement to take hold: what kind of social environments they require, what kinds of people join a movement, and what kinds of leaders are the most effective at leading and sustaining a new mass movement. Let’s explore his findings and how they are reflected in today’s world of money management.

The Seeds of Discontent

Step one, find the fuel of mass movements: widespread frustration. Frustration is the middle ground between comfort and complacency on one end, and hopelessness and destitution on the other end. People at the extremes do not like change. But those in the middle—who want something more—can precipitate mass movements. In all of our businesses, we can ask: where are people frustrated? They should be the target audience.

Through history, mass movements have tended to be religious or nationalistic, but the structure is the same.

In the past, religious movements were the conspicuous vehicles of change. The conservatism of a religion—its orthodoxy—is the inert coagulum of a once highly reactive sap. [Note from Patrick: how great is this line?!] A rising religious movement is all change and experiment—open to new views and techniques from all quarters. Islam when it emerged was an organizing and modernizing medium. Christianity was a civilizing and modernizing influence among the savage tribes of Europe. The Crusades and the Reformation both were crucial factors in shaking the Western world from the stagnation of the Middle Ages.

If frustration is the fuel, then hope is the flame that ignites a mass movement.

Those who would transform a nation or the world cannot do so by breeding and captaining discontent or by demonstrating the reasonableness and desirability of the intended changes or by coercing people into a new way of life. They must know how to kindle and fan an extravagant hope. It matters not whether it be hope of a heavenly kingdom, of heaven on earth, of plunder and untold riches, of fabulous achievement or world dominion. If the Communists win Europe and a large part of the world, it will not be because they know how to stir up discontent or how to infect people with hatred, but because they know how to preach hope.

Hope orients us towards the future. Selling hope works because it takes advantage of our brain chemistry. Surges of dopamine—the stuff in our brains that makes us feel great—peak during stages of anticipation, not during stages of reward. We feel better when a reward is about to come than when we actually receive the reward. This makes hope a powerful motivator. One key, however, is that the reward which is being dangled is not one which will be granted in the distant future, but soon.

There is a hope that acts as an explosive, and a hope that disciplines and infuses patience. The difference is between the immediate hope and the distant hope. A rising mass movement preaches the immediate hope. It is intent on stirring its followers to action, and it is the around-the-corner brand of hope that prompts people to act…The intensity of discontent seems to be in inverse proportion to the distance from the object fervently desired.

The powerful can be as timid as the weak. What seems to count more than possession of instruments of power is faith in the future. Where power is not joined with faith in the future, it is used mainly to ward off the new and preserve the status quo. On the other hand, extravagant hope, even when not backed by actual power, is likely to generate a most reckless daring. For the hopeful can draw strength from the most ridiculous sources of power—a slogan, a word, a button. No faith is potent unless it is also faith in the future; unless it has a millennial component.

Some examples from history:

Rising Christianity preached the immediate end of the world and the kingdom of heaven around the corner; Mohammed dangled loot before the faithful; the Jacobins promised immediate liberty and equality; the early Bolsheviki promised bread and land; Hitler promised an immediate end to Versailles’ bondage and work and action for all. Later, as the movement comes into possession of power, the emphasis is shifted to the distant hope—the dream and the vision.

I’ve encountered this first hand. My book preaches a focus on the long term and the power of compounding. The potential reward? Huge investment returns (and comfortable retirement) for young people. The problem? Everyone agrees with the argument, and then does nothing. It is very difficult to ACT NOW to achieve a reward so distant and intangible. “When we ‘hope for that we see not, then do we with patience wait for it.’” Wait, as in, do nothing.

So, the first part of the formula is find frustrated people and dangle a hope that will quell their frustration, and make it something imminent.

Members of Mass Movements

Next, find people who are most likely to join and advance the movement. Here is a profile of the people who can be most easily persuaded. This is where things get interesting.

Though the disaffected are found in all walks of life, they are most frequent in the following categories: (a) the poor, (b) misfits, (c) outcasts, (d) minorities, (e) adolescent youth, (f) the ambitious (whether facing insurmountable obstacles or unlimited opportunities), (g) those in the grip of some vice or obsession, (h) the impotent (in body or mind), (i) the inordinately selfish, (j) the bored, (k) the sinners…The discarded and rejected are often the raw material of a nation’s future.

The funny thing is that true freedom of choice (and the responsibility that comes with it) is unappealing to many.

Unless a man has the talents to make something of himself, freedom is an irksome burden.

We join a mass movement to escape individual responsibility, or, … “to be free from freedom.”

Read those quotes again and then think about asset flows into passive index funds and Smart Beta. First a note: I am not saying these are bad moves, I suggest these types of products to lots of investors! One of the brilliant aspects of these two products is that they offload the responsibility from the investor or advisor onto the mass movement (strategy) itself, and onto the leaders of that movement. Messrs. Arnott and Bogle owe their success not only to good products but also to the fact that they are shouldering the responsibility for the masses. Keep thinking about indexing and Smart Beta:

A rising mass movement attracts and holds a following not by its doctrine and promises but by the refuge it offers from the anxieties, barrenness and meaninglessness of an individual existence. It cures the poignantly frustrated not by conferring on them an absolute truth or by remedying the difficulties and abuses which made their lives miserable, but by freeing them from their ineffectual selves—and it does this by enfolding and absorbing them into a closely knit and exultant corporate whole.

Most people were/are terrible at picking stocks. It is hard work, it loads risk onto the investor/broker/advisor, it is stressful, and it usually didn’t pan out.

Faith in a holy cause is to a considerable extent a substitute for the lost faith in ourselves.

Enter these popular options which undo those problems. Indexing and Smart Beta represent simple concepts. They simplify as much as possible, not trying to get every detail right but instead communicate a core, essential idea. This works because:

The facts on which the true believer bases his conclusions must not be derived from his experience or observation but from holy writ…“To illustrate a principle,” says Bagehot, “you must exaggerate much and you must omit much.”

How simple and amazing does this sound: “market cap indexes are flawed because they overweight expensive stocks. We remove that bias but keep everything else great about an index. We weight by strong results like sales and cash flow instead of by market opinion. Doing so adds 2% per year.” Genius! Nevermind that I could write an entire book as to why this strategy is just half-assed value investing, those are boring details! This headline idea—combining strong elements of both active and passive—is what matters and creates a legion of advocates.

Furthering the Cause—Movements are Defined in Opposition to Their Devils

Given what we know about loss aversion—that we are doubly sensitive to the bad as we are to the good—it also makes sense that many mass movements unite their followers by introducing a common enemy. In this case, think of active management as the devil.

Mass movements can rise and spread without belief in a God, but never without belief in a devil. Usually the strength of a mass movement is proportionate to the vividness and tangibility of its devil… It is perhaps true that the insight and shrewdness of the men who know how to set a mass movement in motion, or how to keep one going, manifest themselves as much in knowing how to pick a worthy enemy as in knowing what doctrine to embrace and what program to adopt.

Again, like an ideal deity, the ideal devil is omnipotent and omnipresent. When Hitler was asked whether he was not attributing rather too much importance to the Jews, he exclaimed: “No, no, no! … It is impossible to exaggerate the formidable quality of the Jew as an enemy.” Every difficulty and failure within the movement is the work of the devil, and every success is a triumph over his evil plotting.

This “us-versus-them” mentality has always been a powerful driving force behind human action.

We do not usually look for allies when we love. Indeed, we often look on those who love with us as rivals and trespassers. But we always look for allies when we hate.

Active management is an enemy with great credentials. It takes more from the investor in the form of higher fees (which hurts more during lean years like those between 2000-2009). It has a poor history of relative performance versus benchmarks (even though this is just a mathematical necessity due to the tyranny of compounding costs). Rich portfolio managers in Greenwich, CT make fine devils.

Leadership

Hoffer writes, “A movement is pioneered by men of words, materialized by fanatics and consolidated by men of action.”

Given that financial technology companies are on fire, and are operating in an area of frustration, the characteristics of a good leader are very relevant today.

Exceptional intelligence, noble character and originality seem neither indispensable nor perhaps desirable. The main requirements seem to be: audacity and a joy in defiance; an iron will; a fanatical conviction that he is in possession of the one and only truth; faith in his destiny and luck; a capacity for passionate hatred; contempt for the present; a cunning estimate of human nature; a delight in symbols (spectacles and ceremonials); unbounded brazenness which finds expression in a disregard of consistency and fairness; a recognition that the innermost craving of a following is for communion and that there can never be too much of it; a capacity for winning and holding the utmost loyalty of a group of able lieutenants…The leader has to be practical and a realist, yet must talk the language of the visionary and the idealist.

Does this describe the CEO of your favorite Fintech company?

Conclusion

The most fascinating characteristic of mass movement adherents is that they are not seeking self-improvement, but are instead seeking to purge or deny the aspects of themselves with which they are unhappy (again, in this case maybe for failing to pick stocks or managers effectively in the past).

For men to plunge headlong into an undertaking of vast change, they must be intensely discontented yet not destitute, and they must have the feeling that by the possession of some potent doctrine, infallible leader or some new technique they have access to a source of irresistible power. They must also have an extravagant conception of the prospects and potentialities of the future. Finally, they must be wholly ignorant of the difficulties involved in their vast undertaking. Experience is a handicap.

This formula seems applicable everywhere. When used for good it can be powerful. Indexing and Smart Beta are a huge improvement over stock-picking for the vast majority of people. Their popularity is a net positive for investors.

Our key lessons:

Find people who are frustrated. Advisors and investors since 2000 qualify.

Create a hope which can be achieved by joining a movement/using a product. Indexing, Smart Beta

Create unity by finding the perfect enemy. Active Management.

Focus on simply ideas. Exaggeration, simplification (i.e. the omission of too many details) are powerful tools when framing the idea behind the movement. “Indexes beat 80% of active managers, low cost, best net after tax return.” “Same stream of market returns, smarter weighting strategy, 2% more per year.”

So what is the next mass movement? In asset management specifically, I believe it is rules-based strategies that are truly active, not merely tilts towards value and momentum. Many firms do this already, and I believe you will see more of it in the future. The question remains, can these truly active strategies generate a mass counter-movement against the prevailing trends towards passive investing. What might start this movement? Well, indexing and smart beta are boring, and:

There is perhaps no more reliable indicator of a society’s ripeness for a mass movement than the prevalence of unrelieved boredom. In almost all the descriptions of the periods preceding the rise of mass movements there is reference to vast ennui; and in their earliest stages mass movements are more likely to find sympathizers and support among the bored than among the exploited and oppressed.

I will leave you with what is perhaps the most perfect distillation of these many concepts in the poem “The New Colossus” by Emma Lazarus, which is inscribed on the Statue of Liberty.

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

June 9, 2015

Lessons from Market Extremes

We know that markets overdo it at extremes. At the market level, we call these bubbles or manias, panics or crashes. At the stock level, we call them glamour and value. Let’s collect some lessons from the best performing stocks from the two categories where investors have the most extreme (good or bad) expectations for the future—value and glamour stocks.

A quick definition: glamour stocks are those stocks that are in the most expensive 10% of the market at any given time, value stocks are those in the cheapest 10% (both rebalancing annually). Keep in mind that when I say “expensive” I actually mean “high expectations” and when I say “cheap” I mean “low expectations.” The whole premise of value investing isn’t that value stocks are good companies (more often they stink), only that the expectations are too low (and vice versa for glamour).

Starting with these two categories, we then further divide stocks into 10 more groups based on their forward 1-year returns (for this experiment we can forecast the future). I’ve discussed this before, but here are the results.

The best performing glamour stocks are incredible: outperforming by 112% on average. But the median result is underperformance of 11%. Great possibilities, bad probabilities.

The best performing value stocks do really well too, but deliver a slightly less exciting 78% average excess return. But the median result is a positive 5%. Great possibilities and great probabilities.

But now let’s go a level deeper by focusing on just the best performers from each category (the top green line in these graphs). If there are roughly 3,500 tradable stocks in the U.S. today, this means we are narrowing our gaze to 35 stocks on either end of the spectrum, 1% of the market each from value and glamour. We check in on these 35 or so names (there are fewer back in history) every year back to the early 1960’s.

The key lesson we learn is that the excess returns of the best value stocks are far more consistent, if not as impressive. The standard deviation of the return for value’s best performers is 45% historically. For glamour, it is 107%! Here is a distribution of the excess returns.

Consistent with the first few charts, glamour has a much longer tail: more instances of incredible excess returns.

Most of the best value stocks—82% of the total observations—delivered an excess return up to 100%, leaving 18% with higher than 100%. For glamour, almost half (46%) delivered excess returns higher than 100%.

Further, of the best performing glamour stocks, roughly 25% of them delivered an excess return of 150% or higher in a one year period. Only 6% of the best performing value stocks did the same. The best performing glamour stocks are the ultimate winning lottery tickets.

No wonder growth investing is so damn enticing! Now if only we could figure out a way to consistently identify these high-flying glamour stocks (spoiler: you can’t).

These results confirm that value is less exciting than glamour in every way—except for their long term median results. The stories are better for glamour, the futures for the companies appear brighter, and the best performers end up delivering more impressive returns. Yet through it all, value stocks—with their lame outlooks, boring stories, and more homogenous returns—are the ones which, as a category, have delivered the best results to investors.

Bottom line: value wins again for consistency the fact that the median value stock has outperformed nicely. Glamour has the more fun and exciting outliers, but the median glamour stock gets killed and even the best ones are extremely volatile.

Note: I removed anything with a 12-month return of 1,000% or higher to control for extreme outliers. Eligible stocks must have a market cap > $200MM (inflation adjusted) and be a U.S. company.

June 8, 2015

The Best Books on Creativity

Two or so times per year, I share one of the emails which I send out to members of our growing book club, which just passed 3,500 people. Below, I share my favorite list of books in a while.

Over the past 6-12 months, I’ve read almost 50 books on my favorite topic: creativity. I am more and more convinced that engaging in creative activity is the key to both happiness and career success. From the fifty books, I’ve chosen the six best ones to help get you started exploring this crucial and fascinating topic.

The first four books deal directly with the creative process, and the last two deal with what I believe to be the appropriate creative mindset. Enjoy!

The Act of Creation by Arthur Koestler

This book is old and out of print. My copy is a tattered paperback that looks like someone forgot it on the beach. It has an old-school, academic feel to it. This is my favorite book on creativity. I used to think others were pioneers on the topic: De Bono, Csikszentmihalyi, Thiel. Then I read this book and realized they are all just borrowing from him.

Koestler identifies humor, discovery (science, business), and art as the three primary areas of creative potential and explores each in detail. This book is a history of creativity, a how to guide, and a philosophical journey. Creativity is all about collecting pieces and making new associations. One must move away from habitual thinking and over-saturated concepts:

These silent codes can be regarded as condensations of learning into habit. Habits are the indispensable core of stability and ordered behavior; they also have a tendency to become mechanized and to reduce man to the status of a conditioned automaton. The creative act, by connecting previously unrelated dimensions of experience, enables him to attain to a higher level of mental evolution. It is an act of liberation– the defeat of habit by originality … It has been said that discovery consists in seeing an analogy which nobody had seen before.

I could write a whole book based on the insights from this book.

Innovation and Entrepreneurship (Routledge Classics) by Peter Drucker

If you want the most business oriented book on creativity, you cannot do better than Peter Drucker. The book explores these seven areas: the unexpected event, incongruities, process need, changes in market structure, demographics, changes in perception, and new knowledge. Each can be used to find areas of a market ripe for innovation.

Like most books I’ve read on innovation and creativity, this one de-emphasizes the idea of the “individual genius.” Drucker agrees that creativity doesn’t require special genius. Rather, it is a process that requires hard work:

innovation is a discipline, with its own, fairly simple, rules. And so is entrepreneurship. Neither of them requires geniuses. Neither of them will be done if we wait for inspiration and for the ‘kiss of the muse’. Both are work

whatever changes the wealth-producing potential of already existing resources constitutes innovation.

Drucker makes a compelling case that most innovation isn’t in the technology field (in fact, technology is one of the hardest fields in which to innovate). Instead, innovation is about recognizing a new pattern which fits an emerging need in the world:

There was not much new technology involved in the idea of moving a truck body off its wheels and onto a cargo vessel. This ‘innovation’, the container, did not grow out of technology at all but out of a new perception of the ‘cargo vessel’ as a materials-handling device rather than a ‘ship’, which meant that what really mattered was to make the time in port as short as possible. But this humdrum innovation roughly quadrupled the productivity of the ocean-going freighter and probably saved shipping. Without it, the tremendous expansion of world trade in the last forty years – the fastest growth in any major economic activity ever recorded – could not possibly have taken place.

This next passage sounds a lot like Peter Thiel’s Zero to One:

Still, successful entrepreneurs aim high. They are not content simply to improve on what already exists, or to modify it. They try to create new and different values and new and different satisfactions, to convert a ‘material’ into a ‘resource’, or to combine existing resources in a new and more productive configuration.

Drucker encourages us to use the seven areas listed above to find current opportunities. Forecasting is too hard so “don’t try to innovate for the future. Innovate for the present!”

Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

This book studies creative people and creates a common framework for creativity based on their lives and insights. What sets this book apart is its discussion of the environment in which creative people make their discoveries. Csikszentmihalyi highlights the importance three aspects:

creativity results from the interaction of a system composed of three elements: a culture that contains symbolic rules, a person who brings novelty into the symbolic domain, and a field of experts who recognize and validate the innovation. All three are necessary for a creative idea, product, or discovery to take place… creativity does not happen inside people’s heads, but in the interaction between a person’s thoughts and a sociocultural context. It is a systemic rather than an individual phenomenon.

Changing the conditions of your environment can increase the potential for creative insight. You’ll want to incorporate people and ideas from a lot of different areas.

It also seems true that centers of creativity tend to be at the intersection of different cultures, where beliefs, lifestyles, and knowledge mingle and allow individuals to see new combinations of ideas with greater ease. In cultures that are uniform and rigid, it takes a greater investment of attention to achieve new ways of thinking. In other words, creativity is more likely in places where new ideas require less effort to be perceived.

That was just two of my 125 highlights from this book. There is a ton in here to ponder and to help you better set yourself up for creative success.

A Technique for Producing Ideas by James Webb Young

If you prefer fast reads and only want to read one of these books, this is the one for you. This book lays out the creative process almost like the scientific method. This book is entirely free of fluff or hero-worship (a common problem I’ve had with books on creativity).

Here is a distillation. Each of these five stages below is carefully considered. This is the book that cemented my goal to constantly collect ideas from a lot of different fields and store them in one place.

First, the gathering of raw materials—both the materials of your immediate problem and the materials which come from a constant enrichment of your store of general knowledge. Second, the working over of these materials in your mind. Third, the incubating stage, where you let something beside the conscious mind do the work of synthesis. Fourth, the actual birth of the Idea—the “Eureka! I have it!” stage. And fifth, the final shaping and development of the idea to practical usefulness.

Essays and Lectures: (Nature: Addresses and Lectures, Essays: First and Second Series, Representative Men, English Traits, and The Conduct of Life) by Ralph Waldo Emerson

The first part of creative success if gathering pieces (ideas). The second part is putting those pieces together into new patterns, which requires that the creative person make new associations, or sees a pattern amongst pieces that others have overlooked.

Collecting pieces is simple, but it is hard work. The second stage—associative combination—is a little trickier. I believe that the key is to foster an independent, authentic mind and world-view. Most people are “repetition machines,” automatons that function by habit and never explore new things. When I am feeling conventional (happens often), Emerson’s essay Self Reliance is my favorite antidote.

Along with Jiddu Krishnamurti and Thoreau, Emerson challenges us directly to be our own individuals and see the world through our own eyes, rather than through those of others. This is MUCH harder than it sounds, because habits are the brain’s way of saving energy. Overcoming habit and conventional thought/behavior requires great effort. But the resulting “clean” mindset may be the key to making new associations, because you’ll be able to view the pieces you’ve collected with a fresh perspective. Here are a few choice passages from Emerson’s essay Self Reliance.

I READ the other day some verses written by an eminent painter which were original and not conventional. The soul always hears an admonition in such lines, let the subject be what it may. The sentiment they instil is of more value than any thought they may contain. To believe your own thought, to believe that what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men,—that is genius… for the inmost in due time becomes the outmost, and our first thought is rendered back to us by the trumpets of the Last Judgment.

A man should learn to detect and watch that gleam of light which flashes across his mind from within, more than the lustre of the firmament of bards and sages. Yet he dismisses without notice his thought, because it is his. In every work of genius we recognize our own rejected thoughts; they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty.

There is a time in every man’s education when he arrives at the conviction that envy is ignorance; that imitation is suicide; that he must take himself for better for worse as his portion; that though the wide universe is full of good, no kernel of nourishing corn can come to him but through his toil bestowed on that plot of ground which is given to him to till.

Society everywhere is in conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members. Society is a joint-stock company, in which the members agree, for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater. The virtue in most request is conformity. Self-reliance is its aversion. It loves not realities and creators, but names and customs… Whoso would be a man, must be a nonconformist. He who would gather immortal palms must not be hindered by the name of goodness, but must explore if it be goodness. Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind.

Let Your Life Speak: Listening for the Voice of Vocation by Parker J. Palmer

This final book is along the same lines as Emerson (the author is a quasi-Emerson/Thoreau for modern times).

“Ask me whether what I have done is my life.” For some, those words will be nonsense, nothing more than a poet’s loose way with language and logic. Of course what I have done is my life! To what am I supposed to compare it? But for others, and I am one, the poet’s words will be precise, piercing, and disquieting. They remind me of moments when it is clear-if I have eyes to see-that the life I am living is not the same as the life that wants to live in me.

Palmer emphasizes the importance of having a “beginner’s mind” and being receptive and open.

Perhaps the key to making new associations is casting a wide net, listening, and simply being ready to catch or receive combinations as they fly by. This final book, along with Self Reliance can help you foster the appropriate mindset for creative discovery.

***

Lest you think none of this applies to investing, it does! Consider this quote from Efficiently Inefficient: How Smart Money Invests and Market Prices Are Determined, by Lasse Heje Pedersen:

In summary, when you are looking for new cool trading ideas, think about whether there is information that most investors overlook, new ways to combine various sources of information , a smart way to get the information fast, or what type of information is not fully reflected in the price because of limited arbitrage.

Said differently, apply the principles of creativity to find the best potential investment ideas.

If you have more book suggestions on this topic, let me know. If you know of a book loving friend, forward him or her this post so that they can join our growing book club (http://investorfieldguide.com/bookclub/). Have a great month.

June 2, 2015

The Best Quote from the Last Five Investing Books I’ve Read

The $10 I spend on a book buys me a batch of passages and notes. I love to extract the best bits of good books. With some books, I highlight more than 100 passages. 20 is more typical. Here is my single favorite passage from the last five investing books I’ve read (I had to go back more than 50 books to find 5 investing books!).

Efficiently Inefficient: How Smart Money Invests and Market Prices Are Determined by Lasse Heje Pedersen (15 passages highlighted, 1 note)

when you are looking for new cool trading ideas, think about whether there is information that most investors overlook, new ways to combine various sources of information, a smart way to get the information fast, or what type of information is not fully reflected in the price because of limited arbitrage.

This is a helpful guide to active investing. If you are going to bother trying to beat the market you need to be different and have an edge. This advice pretty much applies to any pursuit (art, entrepreneurship, etc).

Successful Investing Is a Process: Structuring Efficient Portfolios for Outperformance by Jacques Lussier (20 passages highlighted, 5 notes)

Some managers should never have existed, a majority of them are good but unremarkable and a few are incredibly sophisticated (but, does sophistication guarantee superior performance?) and/or have good investment processes. However, once you have met with the representatives of dozens of management firms in one particular area of expertise, who declare that they offer a unique expertise and process (although their “uniqueness” argument sometimes seems very familiar), you start asking yourself: How many of these organizations are truly exceptional?

Notice the common theme. For example, “we buy high quality companies at good prices” is not unique. If someone told me “we buy terrible companies at high prices,” I’d be very curious to hear more, if only for a little variety!

The Dao of Capital: Austrian Investing in a Distorted World by Mark Spitznagel (30 passages highlighted, 4 notes)

As we know, roundabout production—bearing the costs of capital investment—typically results in an immediate hit on profits (particularly from noncapitalized investment such as research and development). Our constant refrain sounds again: We live in the seen (what is available to us), and we extrapolate the seen such that we are deceived as it curves (minor leaguers hit linearly extrapolated fast balls, major leaguers hit curve balls); the roundabout is hard, and we are not biologically cut out for it. Thus, the stock market tends to be about immediate bets (or expectations) on distant outcomes—yet all that matters to the bettors tends to be the immediate outcomes. That is, among high ROIC firms, stock valuations and the resulting Faustmann ratios seem to anticipate future profits in the short run so accurately that they miss the curves and the changeups.

One of the most important variables in any investing process is time horizon. Momentum is a great strategy if you favor very recent information and hold for a fairly short period. Value is a great strategy if you can sit patiently. Perhaps quality is the best of all if you can hold indefinitely. People complain about Wall Street’s myopic focus on quarterly results, but I love it! It creates the chance to differentiate one’s investing process by focusing on the longer term.

The Value Investors: Lessons from the World’s Top Fund Managers by Ronald Chan (23 passages highlighted, 4 notes)

Instead of asking questions about the company’s latest earnings outlook or long-term strategic plan, Eveillard’s goal was always to get a sense of the management team’s personality. He explained, “There is no point asking about a company’s earnings outlook because if we are investing for the long term, then short-term earnings never affect our intrinsic value calculation. Asking management about long-term plans is also pointless to me because the world changes. No one can predict what will happen, and so what is more important for us as analysts is to discover the underlying strengths and weaknesses of the business ourselves.”

Short-term earnings won’t affect our outcome because we will hold for a long time and long-term earnings are unpredictable so screw it! Lovely.

Value Investing: Tools and Techniques for Intelligent Investment by James Montier (22 passages highlighted, 0 notes)

The near fatal mistake that investors seem to make repeatedly is to assume that market risk is like roulette. In roulette, the odds are fixed and the actions of other players are irrelevant to your decision. Sadly, our world is more like playing poker. In poker, of course, your decisions are influenced by the behaviour you witness around you.

This Black Swan-y quote is perfect. We so badly want to quantify risk and the odds of bad outcomes, but the market is just US, and who knows how and when we will all go crazy.

If you are a fan of books, check out the book club that I run: I send 3-4 of the best books I’ve read to you in an email each month, culled from the best of the 100 or so I read per year. You can sign up here.

May 29, 2015

A History of The Price-to-Sales Ratio

Price-to-sales is a very simple ratio. Arguably, it is the least nuanced and therefore least manipulated valuation measure. A sale, for the most part, is a sale. Unlike earnings, book value, and other fundamental measures which are sometimes more opinion than fact, sales is a more straightforward number. To be fair, there are still issues like aggressive revenue-recognition and channel stuffing that can be used to manipulate sales numbers (one of the joys of public markets is the felt need to constantly satisfy shareholders with strong quarterly results). Let’s see how the market has valued sales historically. First, here are the raw sales and sales growth for all U.S. stocks since 1963, and the price-to-sales for the overall market.

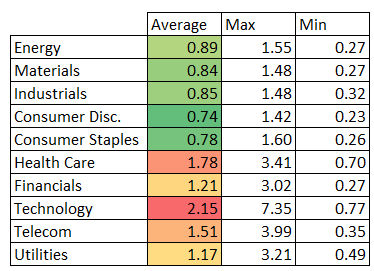

Just as we saw with the price-to-book ratio, there are large average differences in the price-to-sales ratio across sectors.

You’ll notice that higher margin businesses tend to trade at higher price-to-sales multiples. Which brings us to two important quirks about the p/sales ratio: margins and leverage.

First, If you sort all large stocks into five buckets based on their price-to-sales, and then calculate the total net margin for each bucket (total income/ total sales), you see a clear trend: higher price-to-sales = higher average margins, and lower price-to-sales = lower average margins.

A second quirk is that companies with more debt (high debt/equity ratios) tend to trade a cheaper multiples of sales, whereas those with little or no debt tend to look more expensive (as their sales are being generated with less borrowed capital).

The easiest way to adjust for a companies use of debt is to instead use the Sales/Enterprise Value ratio (which adds debt to market cap in the denominator). We will explore that metric in the next post on using the price-to-sales ratio. You can’t really adjust for margin, as a “margin-adjusted” p/sales is just a price-to-earnings ratio!

The easiest way to adjust for a companies use of debt is to instead use the Sales/Enterprise Value ratio (which adds debt to market cap in the denominator). We will explore that metric in the next post on using the price-to-sales ratio. You can’t really adjust for margin, as a “margin-adjusted” p/sales is just a price-to-earnings ratio!

Finally, we see a similar trend in the spread between cheap and expensive stocks using the p/sales measure as we did with price-to-book.

As we will see in future posts, price-to-sales is a great metric to use in combination with other valuation ratios. As a standalone measure, it has the advantage of being quite simple. You can use it to value stocks with negative earnings and cash flow (usually young, growth stocks). Just be mindful that stocks with low price-to-sales may only be cheap because of very low margins or because of very high debt levels.

May 28, 2015

Is it now smart to be dumb?

Maybe one of the only ways to outsmart a group of really smart people is to hold positions that seem very dumb. The dumbest stocks to hold might be those with the lowest consensus expectations for the future. The best way to find stocks for which the market has very low expectations is to use a variety of valuation ratios, because a low valuation = a low collective expectation for the future.

One way to apply this idea is to use stock selection screens. Screens are simple. Most indexes are simple screens. Index screens select stocks because of criteria X, Y, and/or Z (usually market cap, sometimes something simple like dividend growth or price-to-book). Value screens buy because of low price-to-earnings, low price-to-sales, and so on.

Given that stock screening and backtesting tools are cheaper and more ubiquitous than ever, will investment strategies based off of screens continue to work in the future? This is an important question for prospective and current investors in quantitative strategies.

The hard part is sticking with it. I believe the most pertinent question to ask about any systematic/quantitative strategy is not “how hard would this be to replicate” but rather “how hard would this be to stick with.” I think strategies with the most persistent advantage will fall in the latter category. The best secret sauce, to borrow a funny quote from Wes Gray, is to take as much “career risk” as possible.

You will never feel dumber than when you are looking back at a few years of really bad relative performance, which was earned by blindly buying stocks the market collectively thought were dumb investments, using what will feel in hindsight like an overly simple (and dumb) stock screen.

“Wait, you bought XYZ a year ago? Without investigating the company at all? All you had to do was scratch the surface to see that it was a complete basket case with declining earnings and terrible management—and the market knew it! There was a reason it was priced so cheaply! How can you expect to outperform by buying stocks like that?”

This straw man sounds like he has a point. But the weird thing is that value works because you are willing to continue buying what looks like garbage in the face of bad news and poor prospects–even after living through the above scenario.

We have reams of evidence that the low expectations for cheap stocks are too low, on average.

You’ll have to buy through fear, and hold through shame, but value stocks have consistently rewarded those who are willing to ride out (or for the lucky psychopaths out there, ignore) those emotions. The positions value investors hold may seem laughable, but the returns they deliver have been anything but.

Maybe it is the ability to endure feeling like an idiot for a long time that distinguishes the world’s best investors. Maybe feeling dumb is the smartest thing an investor can do.