Patrick O'Shaughnessy's Blog, page 29

May 27, 2015

Using the Price-to-Book Ratio

Having explored the history of the price-to-book ratio, we can now turn to its usefulness as a stock selection criterion. The data suggests a few important points about the price-to-book ratio:

It has worked quite nicely in small-cap

It has not worked as well in large-cap stocks

Price-to-book delivers the best returns when it is used to compare each stock against all others, but requires taking large sector bets

Price-to-tangible book may be a slight improvement over regular price-to-book, but not by much

The very cheapest stocks (those with the lowest price-to-book ratios) have performed poorly

Price-to-book should not be used in isolation

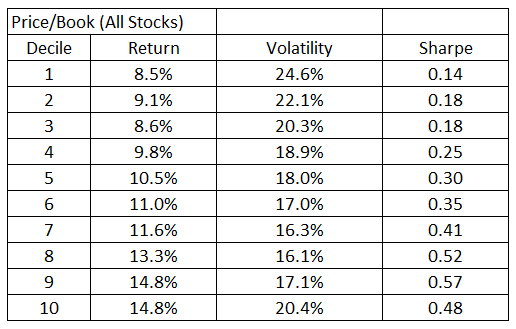

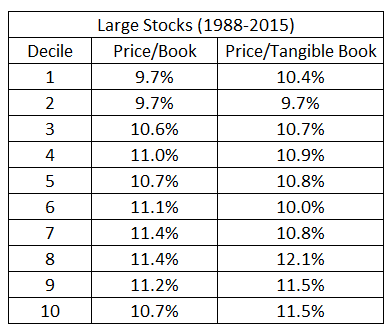

Here are decile returns (rebalanced on an annual basis) for price to book in two universes: large stocks (anything will a larger than average market cap) and all stocks (large stocks + any smaller stock down to $200MM in market cap) since 1963. Clearly, the factor has worked more effectively when smaller stocks are a part of the opportunity set (all stocks).

One key thing to note about price-to-book: it has tended to push investors towards financials, utilities, materials and industrials, and push them away from health care, technology, and consumer staples. Here is a historical sector weight distribution for the cheapest decile of stocks by price-to-book.

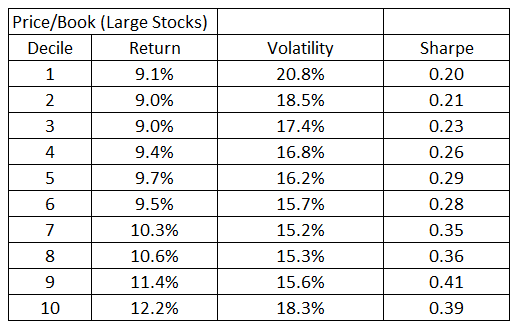

If you adjust the price-to-book calculation for economic sector or industry group (so you compare the ratio only to stocks in the same sector to determine relative cheapness), the factor works (not quite as well) but significantly smoothest sector exposures:

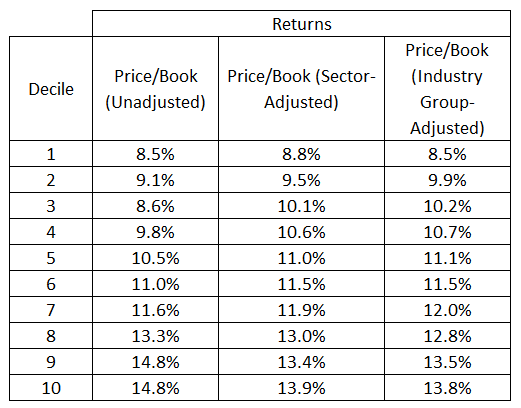

In my first post on the history of the price-to-book ratio, I noted that book value has become far less “tangible” over time: a large chunk of today’s total market book value comes from non-psychical assets like goodwill and intellectual property of various types. For example, here is the percentage of total assets represented by just goodwill across sectors.

And here are a few top names today, listed by goodwill as a percentage of total asset value.

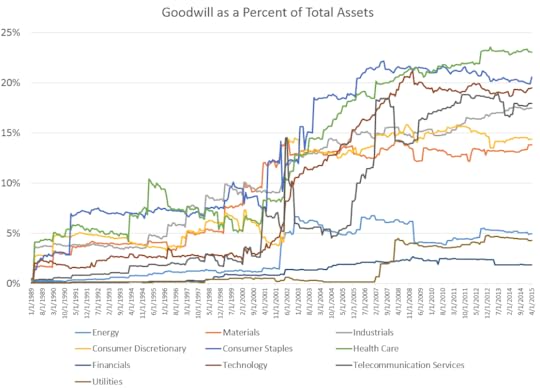

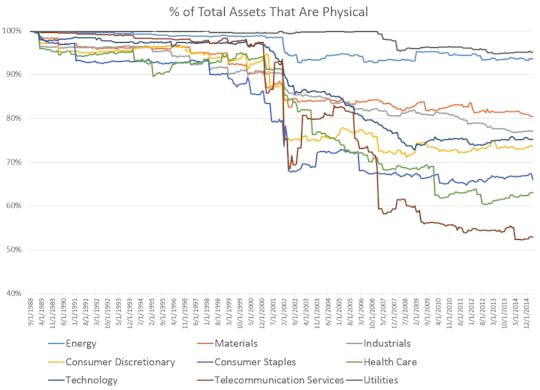

A second way to calculate price-to-book adjusts for (by removing) the value of the non-physical assets. The result is price-to-tangible-book. Here is a comparison of the two ratios since 1988 (when data for goodwill and intangibles becomes widely available). For these results, I’ve REMOVED any stock with negative tangible book value (which would all fall into the worst decile, but perform fine, roughly in line with the overall market).

You can see that these ratios provide very similar results. For those uncomfortable with valuing intangible assets, price-to-tangible book may be the better ratio to use.

One key final point: price-to-book has NOT been useful for building concentrated portfolios, and should therefore only be considered as a factor tilt (think smart beta) rather than a tool to be used in isolation for individual stock selection.

To see why, consider this final chart (I’ve included a methodology behind this chart at the bottom, it’s a little tricky). The general idea is that we ran simulations which randomly lop off half the stocks eligible for selection and half the dates historical to test how the price-to-book ratio works on different subsets of the universe (you’d like to see the factor work in any random group of stocks). The results tell us that even if you get really unlucky with the batch of stocks you have to pick from, the ratio still has delivered some excess return (albeit very little). This test is done at different levels of concentration from 1-stock per month to 300-stocks per month.

Two messages stand out: 1) price-to-book has delivered some small excess return even when the universe is “unlucky,” but 2) you should not build concentrated portfolios based only on price-to-book as they’ve tended to lose to the market by wide margins.

***

This has been a somewhat high-level fly by on the price-to-book factor. What other details would you like to know? Let me know below. I started with this ratio as I believe it to be the least useful valuation ratio. It has worked, but not nearly as well as several others that we will explore. Next up: the price-to-sales ratio.

Methodology: To arrive at the final chart, we ran 1,000 simulations which did the following: 1) for every monthly date since 1962, randomly remove half of the stocks in the all stocks universe (so say go from 3,000 down to 1,500). Then, build a portfolio which buys x number of stocks per month with an annual holding period (listed on the x-axis). Then 2) calculate the forward monthly returns of that portfolio (i.e. for each level of concentration, be it a 5-stock or 300-stock portfolio based on price-to-book). Then 3) randomly lop off half of the monthly returns. Finally, calculate the excess returns above or below all other stocks and dates that made the cut. This does two things: it gives the investor confidence that a factor isn’t reliant on any one set of stocks to work. The middle line is the average observation, where we see a similar pattern as the decile results from earlier (price-to-book peaking at around 3% annualized excess return). The top and bottom lines are the 100th and 900th observations out of the 1000 that we ran, which act as confidence intervals.

Another Note: These results are all for U.S. domiciled stocks only (I’ve sometimes included ADRs in the past but for this factor series will focus on U.S. stocks)

May 26, 2015

Lessons From A Weekend With Special Forces

I spent the weekend with a U.S. Army Special Forces team. Their captain—my best friend from childhood—was getting married.

Many members of the team were Rangers before graduating to Special Forces and had done several tours in the Middle East. The best man—a captain of another Special Forces team and a Ranger school classmate of my friend—once spent 26 out of 30 days in live fire combat.

Here is an amalgam of the team: average height, build like brick sh*thouses, unassuming. Kind, easy to talk with, quick to smile. Unbelievably modest and humble considering what they have done and continue to be willing to do.

I spent a lot of time with the best man, and asked him what it was that set these guys apart. What allowed them to get through the intense selection and training? To operate at an elite level in the face of constant danger? The answer was quite simple: he said “we are more stubborn than anyone you’ll ever meet. Nothing will stop us from achieving what we need to. Perseverance is what sets us apart.”

Sure enough, everyone that I spoke with had an insane story about other-level discipline and persistence. Acts of valor too many to list. Running into enemy fire to grab children. Throwing a wounded officer out of the way before charging his assailant. Refusing a stretcher (despite a bullet having ripped through an abdomen) because others needed it more.

Yet each man would struggle to give a reason for why they did what they did. Pure selflessness, performed automatically.

Something I have discovered is that those whom I admire most have two things in common: they put others before themselves and they never give up. We can’t all be so exceptional, but we can do it in other ways. Listen to Barry Ritholtz’s recent interview with Vanguard CEO Bill McNabb and you’ll see what I mean.

It is so hard to act beyond self-interest—I am as guilty as anyone of thinking too much about myself. But this weekend re-enforced my conviction that these two qualities—selflessness and perseverance—are the noblest to which we can and should aspire.

***

My young son has been sick quite a bit (he’ll be OK), and I have this overwhelming desire to suck all the pain and illness out of him and inject it into myself. These men are doing that for us—constantly.

Thank you to every one of the men I met, and to everyone who has or does serve. Thank you to the families of those same people, who have to endure their own intense hardships. Whatever you may think of the army, or the politics, or anything else, the men and women of our armed forces deserve our utmost respect and deep gratitude. Happy belated Memorial day. Sua Sponte. De Opresso Liber.

May 20, 2015

Why Reading Books Is the Best Thing You Can Do

I was asked a fun question the other day: what is your top advice is for new college graduates? On CNBC, several of us answered the question, and my advice was simple: read as many books as possible. If you want to be interesting, interested, successful, and happy, then there is no substitute for reading.

Let’s explore a few reasons why reading books matters more than ever.

Solving Your Puzzle

Creativity is a surprisingly simple process. Moments of creative insight are simply the recognition of a new pattern among old parts. Therefore, there are two stages that matter: 1) collecting old parts and 2) finding new relationships between them.

There is no better way to collect old parts than reading a variety of great books. If you collect the ideas found in books, you will have the pieces to create new and interesting combinations. The number of possible combinations rises the more ideas you collect. And the potential quality of those combinations rises the more different the ideas are from one another.

Creativity is a puzzle. The desired insight—your eureka moment—is the image. But there is no puzzle box to guide you, no predefined edges to help you isolate your creative image. The more puzzle pieces you collect, the better the odds you’ll recognize the image–your idea. Pieces come in lots of forms, and they are scattered everywhere. The sooner you start collecting, the better.

Distilled Wisdom

Regular “table” grapes—the kind you’d buy at the supermarket—are plump, thin skinned, and have a light amount of sugar content; their flavor fades quickly. They are grown hanging under vines, which limits exposure to the sun but maximizes the volume and quantity produced.

Wine grapes are much smaller, with thick skins and more flavor (sugar content). They are grown to maximize exposure to the sun, which makes them more concentrated in every sense. Each vine of wine grapes yields just one-third as much volume as each vine of table grapes.

Most of what there is to read—articles, news, blogs—are like table grapes. But books are like wine grapes.

Having written a book, I can attest that what ends up in a book is a small subset of what is originally written or considered by the author. I scrapped entire chapters, and jettisoned at least 20 sources which I first thought would be integral to the book. A good book is the distilled wisdom of the author, refined down to the most what is most useful and interesting (non-fiction) or beautiful and enthralling (fiction).

It takes roughly 75 gallons of water to create one gallon of wine, and it probably takes each author a few hundred other books to create one book of their own. It is fun to sit down with a glass of wine and a great book and think about how much has gone into the production of each.

Feeling Alive—Even Immortal

The third and final reason is pure enjoyment. The level of joy one experiences when reading compounds as you read more and more. For me, it feels like a runner’s high—that feeling of invincibility when everything else falls away. It is a kind of bliss.

The more books you read, the more associations you will find, and the more you will realize that people through history have had all the same struggles and all the same joys. Experiencing those ups and downs vicariously is invigorating.

You begin to feel a connection that approaches ecstasy when you read again and again about people through history all making the same journey. As you read more, you begin to identify with a sense of unity that binds us all together and that renders anxiety and fear inert.

Here is an example of the type of associations which spring up as you read more and more. It is a quick journey from 1944, to 5,000 B.C.E., and back to 2006.

This was written in 1944 in a brilliant novel called The Razor’s Edge:

“I wish I could make you see how much fuller the life I offer you is than anything you have a conception of. I wish I could make you see how exciting the life of the spirit is and how rich in experience. It’s illimitable. It’s such a happy life. There’s only one thing like it, when you’re up in a plane by yourself, high, high, and only infinity surrounds you. You’re intoxicated by the boundless space. You feel such a sense of exhilaration that you wouldn’t exchange it for all the power and glory in the world. I was reading Descartes the other day. The ease, the grace, the lucidity. Gosh!”

The title The Razor’s Edge derives from the Katha Upanishad, which was (by historians’ best guess) written 7,000 years ago. The Katha is a conversation between a young boy and the god of death. I remember reading the Katha for the first time and being completely blown away:

See how it was with those who came before,

How it will be with those who are living.

Like corn mortals ripen and fall; like corn

They come up again.

May we light the fire

That burns out the ego and enables us

To pass from fearful fragmentation

To fearless fullness in the changeless whole.

Above the senses is the mind, above

The mind is the intellect, above that

Is the ego, and above the ego Is the unmanifested

Cause. And beyond is Brahman, omnipresent,

Attributeless. Realizing him one is released

From the cycle of birth and death.

He is formless, and can never be seen

With these two eyes. But he reveals himself

In the heart made pure through meditation

And sense-restraint. Realizing him, one is

Released from the cycle of birth and death.

Fast forward once again 7,000 years. Given that we are all artists in our own way, this passage from Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost, written in 2006, is a fitting way to end this ode to reading books.

Certainly for artists of all stripes, the unknown, the idea or the form or the tale that has not yet arrived, is what must be found. It is the job of artists to open doors and invite in prophesies, the unknown, the unfamiliar; it’s where their work comes from, although its arrival signals the beginning of the long disciplined process of making it their own. Scientists too, as J. Robert Oppenheimer once remarked, “live always at the ‘edge of mystery’—the boundary of the unknown.” But they transform the unknown into the known, haul it in like fishermen; artists get you out into that dark sea… Leave the door open for the unknown, the door into the dark. That’s where the most important things come from, where you yourself came from, and where you will go.

OK, I got a little carried away there, but you get the idea! Winston Churchill said, “The empires of the future are the empires of the mind.” The emperors of the future will be those who read voraciously and then use the ideas which they have collected to build new wonders, small and large. So for new graduates—hell, for anyone—the best advice I ever received was to read read read, and it’s the best advice I can offer.

P.S. if this wasn’t a good advertisement for joining a book club, I don’t know what would be! I run one which sends out 3-4 books each month—you can learn more and sign up here.

P.S.S. A helpful tip on idea collecting: Evernote and similar programs are a gift to would be creatives because they make it easy to collect and document your ideas and experiences. Every little thing can be material used in a new combination. I started doing this about 2 years ago, and so far I have 357 notes (one per book that I’ve read since starting this process). Each note has the best insights from the book—a distillation of a distillation. I return to these notes constantly. I highly recommend using a similar system to collect your ideas.

May 19, 2015

The Original Value Factor: Price-to-Book

Cheaper stocks have outperformed the market – Everyone

As I write and think about “factor investing,” I worry about what Aruther Koestler called the “struggle against the deadening cumulative effect of saturation.” Value investing was revolutionary when Graham was writing about it, and was still fairly revolutionary when Fama/French, Lakonishok, and–shameless plug–Jim O’Shaughnessy (among others) were exploring it in the early 1990’s. Today, it is an overly saturated concept. Everyone wants a value tilt which of course is a catch-22 because if everyone tilts towards value, value stocks will stop being value!

Still, while value is a well-covered topic, it is still a bedrock principle for successful active managers that requires a lot of our attention in this Field Guide. As we will see in future posts, the real opportunity in factor investing is the application of factors to build portfolios which are more concentrated than a typical “tilted” market portfolio.

In exploring value, we will start with the OG value factor: price-to-book.

Book value (or “common equity” calculated as total assets minus total liabilities) has some advantages. Unlike earnings, it is fairly stable through time and almost always a positive number. This makes calculation easy and leads to lower turnover in a live value portfolio based on price-to-book. Many famous style indexes and money managers use price-to-book to define value.

Here is the total book value of U.S. stocks and the overall, market level price-to-book ratio for U.S. stocks since 1963. There hasn’t really been a “normal” price-to-book ratio, as it’s ranged widely between 1x and 5x. It is amazing that the market traded at book value twice (in 1974 and 1982) given that the market’s common equity was still very productive: the market’s return on equity was above 13% both times and was stable.

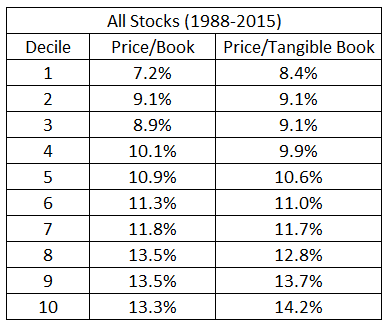

Price-to-book ratios are also quite spread out by sectors, seen below:

Here is an average, max, and min price-to-book for each of the ten sectors since 1963. Clearly, some sectors have structurally higher ratios.

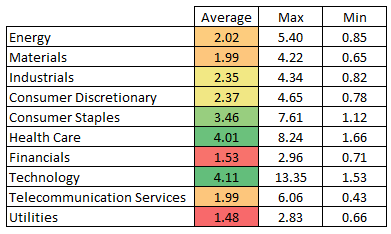

Book value used to be referred to as liquidation value: if you went out of business, book value gave you a sense for how much would you have left over if you sold all your stuff and then covered your liabilities. But the nature of that “stuff” has changed. It used to be mostly psychical stuff (e.g. property, equipment), now a sizable chunk of assets are “intangible,” or non-physical stuff (e.g. patents, brands, client lists, goodwill, trademarks, etc). Today, nearly one fourth of all assets owned by U.S. companies are intangible.

A very different picture emerges when you calculate price-to-tangible book value (where tangible book is total book value minus goodwill and other intangibles). Granted it is unfair to remove a chunk of assets without removing any liabilities, but I still find the comparison interesting.

For some sectors today, intangible assets represent more than 50% of total assets. Check out the progression since 1989, when data on goodwill and intangibles first become available. Some sectors, like telecom and health care, carry huge amounts of goodwill and intellectual property.

One final interesting note: the spread between cheap stocks and expensive stocks (based on p/book) has been rising in recent years. The price-to-book ratio for stocks in the most expensive 25% (75th percentile) has risen from 2.4x in February 2009 to 5.6x today.

***

We should be equally excited and worried that factor investing—which I’ll define as buying a basket of stocks based on proven metrics like value and momentum, rather than buying them because of fundamental research—has become the rage. Excited because it has—historically—been a superior way to invest. But worried because as Yogi Berra said of some restaurant’s popularity, “nobody goes there anymore, it’s too crowded.” We will continue by examining the relative merits of price-to-book as a stock selection factor in detail, and we will try to assess the “popularity” of each factor to see which factors the market may still be ignoring. Stay tuned.

May 18, 2015

Should You Use Active Managers?

How much of what you do in your life is the result of what others expect of you?

I’ve been trying to remove small talk from my life and replace it with what Larry David calls “medium talk.” If you want to try medium talk, I’d steer clear of the above question. I’ve tried it, and it bombs. It bombs hard because most people’s answer is “a lot of what I do is the result of what others expect of me,” and this is a disheartening realization.

But for investors in general, and active managers in particular, this is a very important question. The extent to which you care what everyone else thinks or is doing determines the extent to which you should dabble in truly active management (that is, own something other than a simple market index). Emerson had it nailed when he wrote:

It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude… the voices which we hear in solitude [grow] faint and inaudible as we enter into the world.

Greatness in active management—an elusive quality—requires two traits: the manager must be different and they must be right (on average). Both traits require a confidence—or even arrogance—that is rare.

The ability to select unpopular (and undervalued) stocks, and the patience to stick with those stocks may be a genetic advantage, as Seth Klarman has suggested:

“I actually think there is a gene for this stuff. Whether it is a value investing gene or a contrarian gene, I think that everybody appreciates a bargain, but when the market is going down most people overreact and get scared…for me it’s natural, but for a lot of people it’s fighting human nature.”

But whether the right independent psychology is determined by nature or nurture, it is essential; caring what others think about your portfolio will cause issues when times get tough. So, how different should you be?

Being Different

The best way to measure how different a manger is from the benchmark is to measure their “active share.” This statistic roughly represents the percentage of the portfolio (1-100) which is different from the benchmark. An active share of zero indicates an index fund, an active share of 95 means there is almost no overlap between the portfolio in question and the overall market.

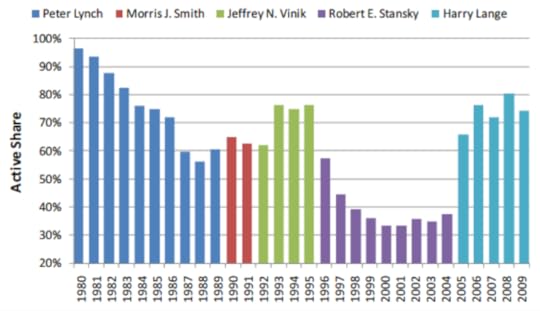

Active managers have a cost hurdle to overcome. They are handicapped by higher fees, transaction costs, and taxes. To overcome this hurdle, active managers should be different—but the opposite has been happening. Here is the industry trend: away from very unique, differentiated portfolios (active shares >80) and towards more similar, market-like portfolios (active shares < 60).

Source: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf...

But as this chart from a great Fidelity paper on active share makes clear, the more different, the more unique the returns, both good and bad. As active share for the observed mutual funds go up, so do excess returns (both good and bad).

Source: https://www.fidelity.com/bin-public/0...

Holdings which are very similar to a benchmark may not underperform by much, but they won’t outperform by much, either.

Active share has probably been a bit overblown by its supporters. It is not some silver bullet that identifies managers who will outperform. Instead it is just one statistic that can be helpful alongside several others. Read these two papers (here and here) for a balanced opinion on the merits of active share.

Being different is merely the first step towards the potential for lasting outperformance. Equally important is being right. How to be right is, of course, the holy grail of investing and is the broader subject of this Field Guide.

Should Investors Hire Active Managers?

I was with Jason Zweig last week for a CFA Institute event called “Putting Investors First.” I agreed with Jason that the best way to put investors first was not to quibble over basis point fee differentials but instead to focus on several percentage points being left on the table by terrible investor behavior.

The answer to whether you should use active strategies is not a binary yes or no. The answer to the question is unique to each individual and it is dependent on that investor’s temperament. To use active strategies, you must truly be willing to be different and (often) wrong for extended periods of time. If you can’t do that, you should probably own an index-like portfolio (which is completely fine!).

Therefore, finding a strategy that each investor can stick with is the most valuable thing any advisor can do for their client.

I love robo-advisors, and send a lot of young people their way. But there are not 8 or 9 strategies that fit all. Emerson again:

No law can be sacred to me but that of my nature. Good and bad are but names very readily transferable to that or this; the only right is what is after my constitution; the only wrong what is against it…What I must do is all that concerns me, not what the people think. This rule, equally arduous in actual and in intellectual life, may serve for the whole distinction between greatness and meanness.

It is very hard to have a different portfolio when the S&P 500 is rocking and rolling, but a good advisor can help the investor keep their eye on the prize. One thing a good advisor can do is assess how each investor may react in difficult market environments. The more independent the spirit, the more appropriate truly active strategies may be.

It is so easy to dole out the advice “do what is right for you,” but much harder to follow through on that advice. We are social creatures, and most people (myself included) DO care what others think or expect of them. Sadly, this tendency is an obstacle to investing success. Emerson for the trifecta:

Insist on yourself; never imitate. Your own gift you can present every moment with the cumulative force of a whole life’s cultivation; but of the adopted talent of another you have only an extemporaneous half possession.

I generally believe that the hierarchy of equity strategies looks like this: Stock picking < index funds < titled index funds (smart beta) done right < higher conviction factor investing (say, a portfolio of 50-100 stocks based on factors like value, momentum, and shareholder yield).

While the latter category has provided the most impressive results, it has more extreme short term results (above and below the market). Accordingly it is only the best strategy if the investor in question can withstand those shorter term periods of pain.

I’ll leave you with passage from Jiddu Krisnamurti, which rephrases the question that we began with and challenges you to be creative and self-reliant.

[External] authority prevents the understanding of oneself, does it not? Under the shelter of an authority, a guide, you may have temporarily a sense of security, a sense of well-being, but that is not the understanding of the total process of oneself. Authority in its very nature prevents the full awareness of oneself and therefore ultimately destroys freedom; in freedom alone can there be creativeness. There can be creativeness only through self-knowledge. Most of us are not creative; we are repetitive machines, mere gramophone records playing over and over again certain songs of experience, certain conclusions and memories, either our own or those of another.

Knowing oneself, and investing accordingly, is the biggest advantage you can have.

May 14, 2015

Knights, Warlord Entrepreneurs, and Innovation

I am invigorated by the amount of innovation that is flowing today, no matter how crazy the associated business valuations may be; there is nothing more exciting than dealing in ideas that may change things for the better—from the individual to the global scale. To keep the momentum and motivation going, we can learn a lot about entrepreneurship, innovation, and where we should focus from Medieval Knights and modern warlords whose histories and stories serve as further inspiration to keep pushing.

The lesson they teach us is that one of the best advantages in life, business, and thinking is not being the incumbent, not having some existing paradigm to protect.

The key to innovation (and creativity) is living on the bleeding edge. Less energy spent maintaining what is already established (which we are prone to guard) means more energy to spend creating uniquely new methods, ideas, and companies.

Medieval knights are one of the best examples of the cycle from innovation, to incumbency, to irrelevance. The four stages of this evolution are laid out quite brilliantly in the new book Warlords, Inc. and provide a framework for thinking about the world today.

A key point made by the authors is that “most established organizations—whether in government, business, or civil society—are poorly positioned to adapt.” As you read through these stages, think of the investing industry—there are many related examples.

The first stage of this process is that of entrepreneurism and experimentalism. A weapons system was required to contend with the barbarian raiders that had plagued Western Europe for centuries. These raiders were greatly responsible for the destruction of the Roman Empire and precipitated the shift from the classical to the medieval age. By the Battle of Tours, it was apparent that heavy cavalry was the solution to this threat. This required taking infantry and mounting them on horseback. The Carolingians and other empires of the era—essentially lead by local warlords and strongmen who had seized power—had to go through a trial-and-error process to make this new system work. The entire arms and armor, training and organization, and logistical support system (like the mass breeding and sustaining of warhorses) had to be created from the ground up. As this system was established, heavy cavalry forces grew increasingly deadly.

So, step one, innovation to solve a pressing problem. Like most innovation, tinkering was a key to find a successful solution. This is almost always the case in the creative process.

The second stage in this process is institutionalization. In this stage, not only have “things been worked out” but also standard operating procedures have developed. Mounted cavalrymen not only became the first line of defense for western Christendom but also gained position and privilege on their way to legitimacy within the new civilization that had formed. Lands were won, castles erected, and ultimately the knight allowed the empire and kingdoms of the West to go on the offensive in what were essentially crusades in eastern Europe and the Holy Lands.

Step two, the innovation matures and reaches the peak of its usefulness.

Ritualism characterizes the third stage of this process. The effectiveness of the knight on the battlefield began to be severely degraded as technological threats matured. Dogma and oppressive bureaucracy set in, with armor becoming heavier and heavier and with cumbersome ornamentation beginning to appear. In this stage, things are done because that is the way they have always been done; process becomes more important than progress. Further, a climate of zero tolerance and risk aversion exists. Questions about the efficacy and logic of directives are suppressed while new and creative ideas are stifled.

Step three, institutional bloat creeps in. Can you imagine fighting in this thing below? Me neither, but many companies have the equivalent of this suit of armor’s ornamentation—superfluous fluff that indicates complacency and incumbency.

An investment analogy here: closet indexing. Here is the “active share” (percent of the portfolio unique vs. the benchmark, where higher means a better chance of very unique returns) of Fidelity’s Magellan Fund through time under different managers. Small, nimble, and daring to start. Large, bloated, and risk-averse later. Read Michael Kitces on this topic for more.

The final and fourth stage of this historical process is satirical in nature. That visionary brute with a hunger in his eyes, quite willing to kill quickly and without remorse, who existed in the first stage has now been fully neutered. Strong arms and armor and a stout warhorse have given way to orders based on fluff, the wearing of gaudy dress, and cushy saddles. Once heroic figures, embodied in images such as St. George the Dragon Slayer, devolved into old men on broken-down mounts fighting monsters made out of windmills. The time of knights had passed and to field them now in battle would be blatantly suicidal.

The cycle repeats—new entrants dethrone the knights:

In fact, the knight had been stalked for some time by a new visionary businessman and killer, one wielding early firearms and siege cannon. This warlord entrepreneur was not of polite society and was not an agent of the state; in fact, he was considered little better than a common criminal—if not worse, as his weapons smelled of fire and brimstone and suggested that dark and demonic forces were at play. His weapons were strange and disruptive, he had no stake in the prevailing status quo, and he would readily kill if disrespected or if the contract was lucrative enough. Against such entrepreneurs and their brethren, the technologically inferior knight was no more than prey and was eventually hunted into extinction.

The types of weapons—physical, financial, or technological—that dominate at a given time have a huge impact on society. An analogy can be drawn to finance and banking. Carroll Quigley explores the consequences of weapons technology in his book Tragedy and Hope.

Periods of specialist weapons [e.g. knights] are generally periods of small armies of professional soldiers (usually mercenaries). In a period of specialist weapons the minority who have such weapons can usually force the majority who lack them to obey; thus a period of specialist weapons tends to give rise to a period of minority rule and authoritarian government. But a period of amateur weapons is a period in which all men are roughly equal in military power, a majority can compel a minority to yield, and majority rule or even democratic government tends to rise… The medieval period in which the best weapon was usually a mounted knight on horseback (clearly a specialist weapon) was a period of minority rule and authoritarian government.

Think of access to information, trading, markets and finance in general. Often through history,

[the] parts of the system concerned with the production, transfer, and consumption of goods, were concrete and clearly visible so that almost anyone could grasp them simply by examining them, while the operations of banking and finance were concealed, scattered, and abstract so that they appeared to many to be difficult. To add to this, bankers themselves did everything they could to make their activities more secret and more esoteric. Their activities were reflected in mysterious marks in ledgers which were never opened to the curious outsider.

This opaqueness and privileged access is a type of weapon itself, one wielded most powerfully in the early 20th century, when a group known as “Society” or the “400” (as in 400 people total) controlled most of the global banking system. “Sailing the ocean in great private yachts or traveling on land by private trains, they moved in a ceremonious round between their spectacular estates and town houses in Palm Beach, Long Island, the Berkshires, Newport, and Bar Harbor; assembling from their fortress-like New York residences to attend the Metropolitan Opera under the critical eye of Mrs. Astor; or gathering for business meetings of the highest strategic level in the awesome presence of J. P. Morgan himself.”

So now the key question, where are today’s knights? And what can be done about neutering their weapons? These are the questions that innovators and entrepreneurs should be (and are) asking. It is already happening in the realm of financial technology and elsewhere, so young people and entrepreneurs should take note.

Back to Warlords Inc. One final quote stirred me, as it seems applicable for anyone’s role in their business, large or small:

Everybody else has a policy. Warlord entrepreneurs have obligations. Everybody else has a hierarchy. Warlord entrepreneurs are accountable to the situation.

Obligations and accountability are advantages over policy and hierarchy. They allow upstart Davids to dethrone Goliaths. The next decade will be fun to watch, hopefully we can all participate.

If you are a fan of books, check out my book club: I send 3-4 of the best books I’ve read to you in an email each month, culled from the best of the 100 or so I read per year (you’ll also get an investor curriculum right away filled with books, articles, videos, and papers). You can sign up here.

May 13, 2015

O’Doul’s Part 2

I posted the other day about fundamental indexation being the O’Doul’s of value investing, because it is just the first step away from a market cap weighted index and towards a more differentiated value portfolio.

I received lots of emails about the post, so figured I would spend more than 20 minutes on the time series (probably a good rule in general!). First thing to note: I had removed return outliers (stocks with bogus or unreasonably high returns) but did not remove valuation outliers (stocks that rate as extremely cheap with earnings yields or cash flow yields way above the rest of the market). When I remove the valuation outliers (which carried very high weights because of their high earnings yields), the results change. Returns were about 1.5% per year lower (because some of the large weights did very well) and standard deviations 2% per year lower (i.e. less volatile, because the large weights were very volatile). These results offer what I think are a more fair representation of the “value weighted” strategies I presented.

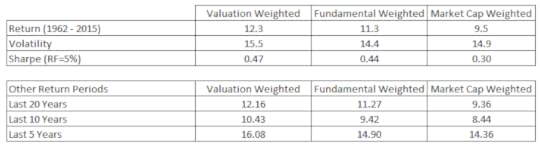

This time I am combining measures like a fundamental index would, instead of presenting several single factor results. I use cash flow, sales, and earnings to determine weights in both a “fundamental” style index and a “valuation” style index. Now, all valuation outliers are stripped out (stocks with a P/E or P/CF under 2 or a P/Sales under 0.1 were removed). The results are as follows (someone asked for more recent results as well, which are included below):

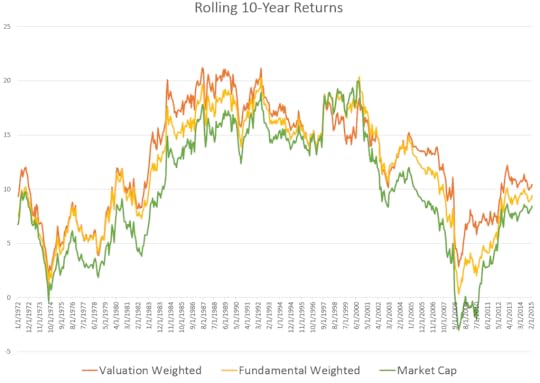

Like before, value works better than fundamental which works better than market cap. Here are the rolling-10 year results historically. Both outperform market cap weighting roughly 93% of the time in 10-year periods, with the periods ending 1998 and 1999 being the only exceptions (no surprise as that was value investing’s worst period).

Once again, the advantage of favoring cheaper stocks is clear. The issue I have with the valuation index, having spent a little more time with it, is that it is extremely diversified–too much so. Its top 10% holdings today represent just 6% of the portfolio and the top 100 40% of the portfolio. Compare that to fundamental index where the top 10 represent 22% and the top 100 69%. Value works great when you focus on the cheapest companies, but given that this method requires owning some weight in all large U.S. stocks, it restricts the size of the bet we can place on the cheapest stocks.

If our hypothetical index removed the most expensive half, or three quarters, or worst 90% of stocks entirely, and then weighted across the remaining cheaper stocks, the results would be quite a bit better. For example, the cheapest 10% of large U.S. stocks across this same period delivered a return of around 14.5%–more than 2% per year higher than the valuation-weighted index.

I’ve written a lot about value investing, and think that more concentrated applications of the discipline work best. But even in diluted form, value has provided a strong edge against cap-weighted benchmarks.

May 12, 2015

Robo-Advisors, Financial Advice, and Millennials

I had a great time today with Jason Zweig and Beth Hamilton-Keen talking all things millennials, robo-advisors, and investor behavior.

We talk alot about the importance of using automation and technology to our advantage, so its fun that the set is completely virtual. Check out the video below:

May 11, 2015

The O’Doul’s of Value Investing

Note: Please also read part two which corrects for a few outliers in the below results

Traditional index funds are gaining record market share. The weight of each stock in these index funds is determined by its market capitalization. But bigger is not better.

Enter fundamental index. These improved indexes weight stocks by variables “smarter” than size, like book value and sales. But these changes are just the first step towards true value investing. Fundamental index is the O’Doul’s of value investing*.

I don’t really get why anyone would prefer fundamental index to more concentrated, pure-play bets on value or shareholder yield. Let’s see why.

Here are a number of ways you could weight stocks in an index like fund. Key point: every one of these strategies owns (mostly) the same stocks (all large U.S. domiciled stocks), but weights them according to different variables. The only reason a stock would be included in one but not another is because it has a negative value for the variable (say, a company with negative earnings or cash flow, which screw up the math).

Market cap is the worst variable by which to weight stocks.

Market cap is the worst variable by which to weight stocks.

“Fundamental” weights do better with similar volatility and thus improved Sharpe ratios.

Value weighting (using “yields” like earnings yield (earnings/price)) to do the weighting delivers the best returns. Using shareholder yield to weight stocks works great: solid returns with lower than market volatility.

Think of it this way: the benefit of fundamental index is that it removes price from the equation and replaces it with some sort of fundamental value (sales, earnings, book value). This removes a persistent bias towards more expensive stocks. But these results show that for earning better returns, you want to re-introduce a price-bias, just in the other direction: towards cheap stocks.

Here’s the thing, I ran this in 20 minutes–yet market cap weighted index funds are garnering record inflows.

I realize that the future may be different: maybe expensive stocks, or those paying no dividends and issuing shares, will dominate for decades. I doubt it.

There are no costs (fees, transaction costs) baked into these results, but at the very least, these simple results expose a key flaw of market cap weighting.

*I had a more vulgar joke in here but thought the better of it, thanks to Tobias Carlisle for talking me out of it and giving me a replacement

May 8, 2015

The Active Manager’s Toolkit

There are only so many aspects of the investing process that we can control. Categorizing these elements will serve as an outline for our research. Let’s outline the active management process and try to leave no aspect uncovered. Your comments here—on elements that I’ve missed—would be much appreciated!

This outline will be for a portfolio of stocks only. Several of these elements blend together.

Strategy

This is a huge category. But ultimately every active manager is collecting, adjusting, and processing data, evaluating that data (deciding what matters and what doesn’t), and reaching buy/sell decisions. Active managers approach these three steps in a million ways. We will do our best to evaluate each of the three levels.

Concentration & Portfolio Construction

How many stocks should you own? How much diversification is too much? We will explore this under appreciated topic in detail, mainly in the context of factor investing.

Trading frequency and method, time horizon

This overlaps with portfolio construction. How does a manager put their strategy into action? This includes behavioral foibles, because buy and sell decisions are often the result of our mis-calibrated psychology. Turnover is demonized, but in order for some of the best investment strategies to work (e.g. momentum), turnover is necessary.

Costs

Taxes

Market impact

Commissions

Fees

Donald Rumsfeld might call these costs the “known knowns” in investing. We can keep costs down in a number of different ways to avoid what Jack Bogle calls “the tyranny of compounding costs.” These will be important to consider alongside #3. The key is a balance of costs with the benefits expected by incurring those costs.

***

We will consider these important categories in isolation. What are the options within each? What are the relative merits and dangers of each option? How can investors find the style that best suits their needs and their temperaments?

While important in isolation, these categories are most important in combination. For example, it may make sense to concentrate a value-based portfolio more than a momentum-based portfolio. Ditto for trading/rebalance strategies.

There are never silver bullets in investing. There is no perfect strategy. There are a number of strategies—themselves quite different from one another—that have worked well historically.

There is no one statistic that is best for evaluating a strategy, either. Instead, a suite of statistics is best: t-stats, returns, consistency (base rates), sortinos, omega ratios, drawdowns, diversification, liquidity, and so on.

Perfect is the enemy of good, in this case. Nothing will be perfect, but perhaps we can put the odds more firmly in our favor.

What have I missed? What else should we consider? Let me know in the comments below.

P.S. Luck would be a fifth and final determining factor—one that is sadly out of our control. We can investigate measures of skill like information ratio, but there will always be some component of luck in any investment outcome.