Patrick O'Shaughnessy's Blog, page 32

November 24, 2014

Value and Glamour Investing, Re-Envisioned

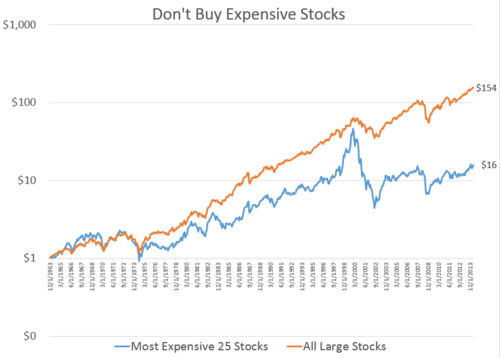

Did you know that the best performing glamour stocks outperform the best performing value stocks? Sounds exciting, right? Well it may be, but expensive stocks still stink. In this piece I visualize the performance of value and glamour stocks in a new way to make the point once more that value trumps everything.

Why in the world do people buy expensive stocks? Every shred of academic evidence shows that they underperform over the long term, and yet we keep buying.

We do this because we are so focused on the spectacular possible outcomes when we should instead be focused on the more sobering probable outcomes. I’ve referred to expensive stocks as lottery tickets in the past, because while investing in a group of expensive stocks (or lottery tickets) is usually a bad idea, sometimes you’ll get a winning ticket.

In the case of glamour stocks, these winning tickets have yielded incredible returns. Last October, Tesla and Cheniere Energy were the two most expensive large stocks trading in the U.S. Tesla was priced at 15 times its sales, Cheniere at 35 times sales. And yet over the next year, Tesla was up +51% and Cheniere +88%. People see results like this and think “valuations be damned.”

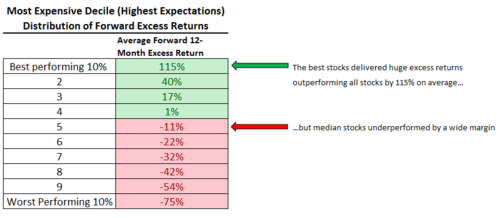

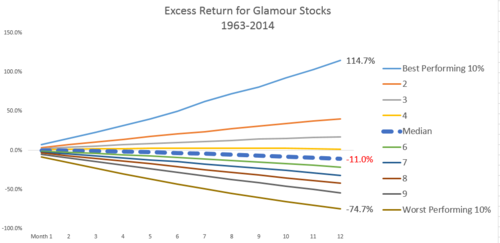

I define glamour stocks as the most expensive 10% of the market (rebalanced annually) by measures like p/sales and p/earnings. Glamour stocks as a group do poorly, but digging a little deeper we see that some are huge winners. Within the glamour stock universe, I sort stocks based on their forward 12 month return into ten equal groups. The average results are illuminating:

You notice that the best performing glamour stocks beat all stocks by an average of 115% over the coming year. Talk about winning the lottery. But here is the problem: the median glamour stocks lost to the market by -11%, on average and the worst glamour stocks lost by 75%. Over and over again, we are seduced by the possibility of earning huge excess returns and blinded to the probability that we will underperform the market. Probabilities are boring, possibilities are exciting. But probabilities are all that matter in an uncertain world.

The first lesson, as always: some expensive stocks kill it, but the category stinks.

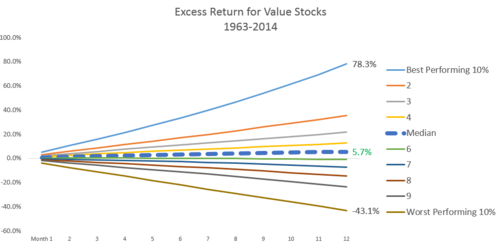

There is a flip-side which is much more enticing. Howard Mark’s (and many others successful investors) always highlight the importance of asymmetry in the investing process. The best way to succeed is to follow a strategy which is skewed in your favor on the upside.

In a recent memo, Marks said, “The goal in investing is asymmetry: to expose yourself to return in a way that doesn’t expose you commensurately to risk, and to participate in gains when the market rises to a greater extent than you participate in losses when it falls. But that doesn’t mean the avoidance of all losses is a reasonable objective. Take another look at the goal of asymmetry set out above: it talks about achieving a preponderance of gain over loss, not avoiding all chance of loss.” (his emphasis)

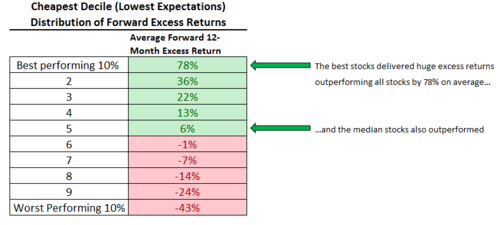

With that in mind, check out the same results for the value portfolio:

This shows that value investing offers the right kind of asymmetry that investor should seek: on average there is more to gain than to lose, because while some value stocks get killed, the average ones significantly outperform the market on an annual basis.

Glamour/lottery stocks, by contrast, have the wrong kind of asymmetry: some do exceptionally well, but the average ones significantly underperform the market.

It is fascinating that if you could see the future, you’d do the best if you bought the best of the glamour stocks: the best performing glamour stocks outperform the best performing cheap stocks. But you can’t predict the future, so don’t try. Forget the splendiferous possibilities of glamour stocks and focus your portfolio in value stocks that offer the highest probability of success.

November 21, 2014

Favorite Interviews

Interviews are my favorite. Lighter than presentations and easier than long pieces of text, interviews can provide fun and digestible insight into a topic--just look at the rise of the podcast!

Here are my favorite interviews so far:

Talking all things investing (whether you are a millennial or not) with the great Morgan Housel of the Motley Fool and Wall Street Journal

Talking millennials and money on Squawk Box

A wide ranging discussion with Carol Massar on Bloomberg Radio

Have a great weekend!

November 17, 2014

How Much Capital is Needed To Produce Sales?

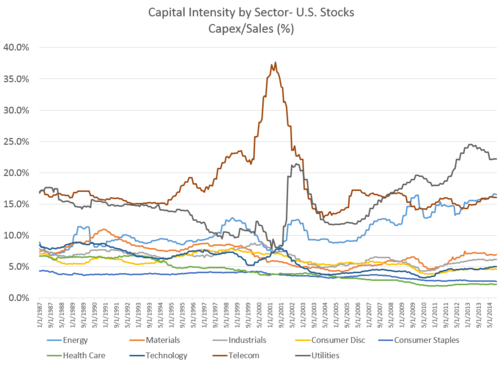

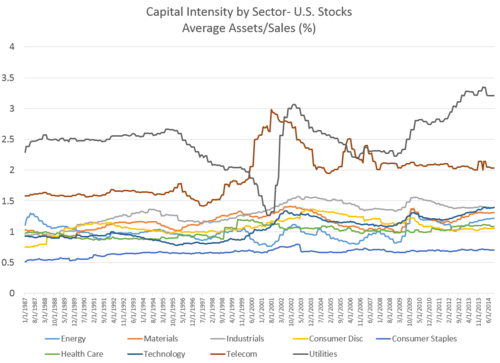

How much capital is required to produce sales? I think this is an interesting question across U.S. economic sectors. Some sectors require boatloads of capital, others very little. Below are two looks at capital intensity (using capex-to-sales and assets-to-sales). For both, higher numbers indicate more capital intensive businesses.

Utilities and Telecoms are traditionally the most capital intensive sectors, requiring tons of assets and capex to produce sales. Conversely, Consumer stocks have traditionally required far fewer assets to produce sales. Of note is the major rise in Capex/Sales for the energy sector, as more expensive means of extracting fossil fuels (tar sands, shale, etc) have become more important.

In a future post I'll analyze whether or not these have been useful factors for stock selection, both within and across sectors.

How do you think capital intensity should factor into the investing process? I'd love to hear your thoughts below on the utility of these factors.

November 5, 2014

How Concentrated Should You Make Your Value Portfolio?

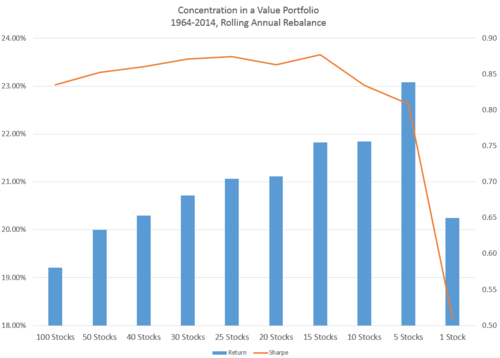

To take advantage of value investing, you need a smaller portfolio than you may think. I was curious to see what different levels of portfolio concentration would have produced in a value-only portfolio over the past 50 years, and report the results here.

I set up portfolios which bought the absolute cheapest stocks trading in the U.S. (including ADRs). Portfolios ranged from 1 stock to 100 stocks, and stocks needed to have a minimum market cap of $200MM (inflation adjusted). Cheapness is defined as an equal weighted combination of a stock’s price/earnings, price/sales, EBITDA/EV, Free Cash Flow/EV and total (shareholder) yield. Each portfolio was rebalanced on a rolling annual basis (meaning 1/12 of the portfolio is rebalanced every month. Think of it like maintaining 12 separate, annually rebalanced portfolios). This means that the “one stock portfolio” will have more than one stock, because different stocks rise to the top through the months. This process removes any seasonal biases and makes the test more robust.

Here are the results, including return and Sharpe ratio. The best returns came from a 5 stock (!) portfolio. The best Sharpe ratio came from the 15 stock version. Both return and Sharpe degrade after 15 stocks.

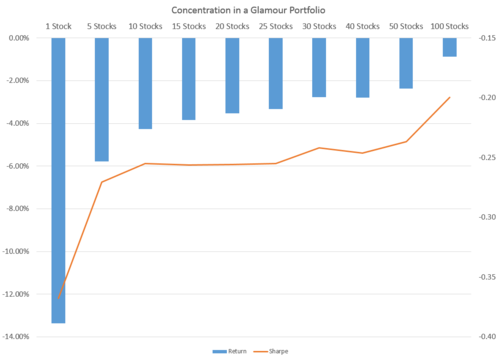

The same is true of glamour portfolios. The concentrated glamour portfolios have bad returns and are incredibly volatile. The 1-stock version had an annual standard deviation of 50% and the 5 stock version had a standard deviation of 40% (hint, I wouldn’t short these!).

I’ve written before about overdiversification. I’m also a huge believe in high active share, and that to beat the market you must dare to be great (that is, different). These results are further evidence support these beliefs.

null

October 28, 2014

The Contrarian (Sociopathic?) Mindset

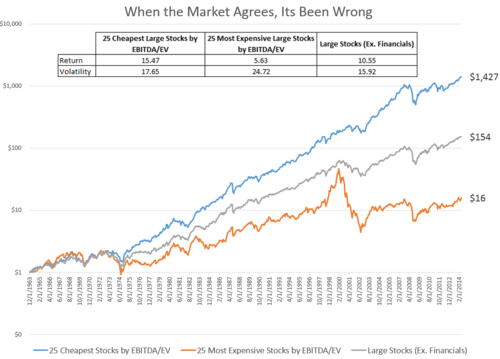

Expensive stocks suck. Cheap stocks are great. If you had followed these basic concepts through history, your results would have been incredible. Look below at the disastrous returns you’d missed by avoiding expensive stocks! And the huge returns you would have earned buying cheap stocks! On paper these results are enticing. But achieving results like this in the future would require a resilient and contrary mindset. Do you have what it takes?

These results are for the cheapest and most expensive large, non-financial stocks in the U.S. based on their EBITDA/EV ratios (rebalanced on a rolling annual basis). But “expensive” and “cheap” are not really the right words to be using to describe these two types of stocks. More accurate would be “exciting” and “terrifying.” Stocks at these market extremes are those for which the market has the greatest consensus—both positive and negative.

In the case of exciting stocks, the consensus opinion is that the future is bright. It helps to replace the word “valuation” with “expectation.” High expectations—for companies like Tesla—lead to “exciting” prices. In the case of terrifying stocks, the consensus opinion is that the future is bleak or non-existent. Again using “expectation” instead of “valuation,” low consensus expectations lead to “terrifying” prices.

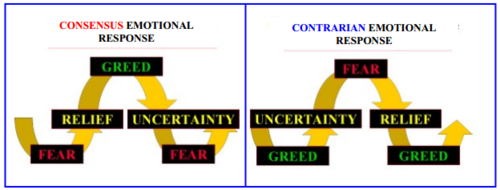

To buy into a terrifying portfolio, you need to have a contrary mindset. This mindset is almost sociopathic, because it requires not just ignoring the crowd, but actively trading against it. This flow chart below illustrates the counter-flow required to be a successful contrarian investor:

Case in point: today, 12 of the cheapest (most terrifying) 25 large stocks are large energy stocks. Would you buy a portfolio that was 50% energy right now? Oil has been in free fall. Because the energy sector has gotten more and more capital intensive over time, it requires higher energy prices to be very profitable. These companies may not be able to pay dividends in the future. If energy prices continue to fall, who knows what will happen to these stocks. It is easy to build a bleak narrative for energy stocks.

Let’s say you can stomach lots of energy stocks today. Would you then be able face similarly scary portfolios every year for the rest of your investing career? Remember, this isn’t a one-and-done trade. It is a constant cycling into the most hated stocks out there. This is not easy stuff.

One of the best books I’ve ever read is The Tiger by John Vaillant, which chronicles the search for a man-eating tiger in the Russian wilderness. This passage from the book (with my emphasis added) highlights aspects of the mental fortitude it takes to be a truly contrarian investor.

“The most terrifying and important test for a human being is to be in absolute isolation...A human being is a very social creature, and ninety percent of what he does is done only because other people are watching. Alone, with no witnesses, he starts to learn about himself—who is he really? Sometimes, this brings staggering discoveries. Because nobody’s watching, you can easily become an animal: it is not necessary to shave, or to wash, or to keep your winter quarters clean—you can live in shit and no one will see. You can shoot tigers, or choose not to shoot. You can run in fear and nobody will know. You have to have something—some force, which allows and helps you to survive without witnesses…Once you have passed the solitude test you have absolute confidence in yourself, and there is nothing that can break you afterward.”

Contrarian investing will require that you be “alone” almost all the time. The rewards can be great, but the journey is arduous. As Joesph Campbell said, "the cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek."

null

October 27, 2014

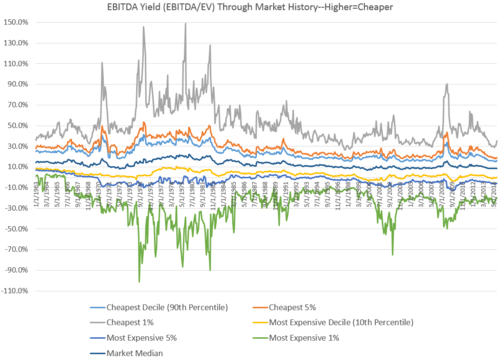

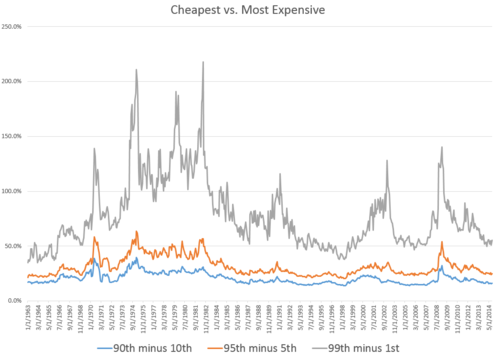

The Value Convergence

The valuation difference between the market's cheapest stocks and its most expensive has always fascinated me. Here are the EBITDA yields (EBITDA/EV, higher=cheaper) at different break points since the early 1960s.

At the market extremes (99th and 1st percentiles), things have converged a great deal. The cheapest percentile (25 or so stocks) are much more expensive (lower yields) than they were in 2009. The most expensive percentile is less expensive (although still has a negative EBITDA, just less so relative to its enterprise value).

No matter which breakpoints you choose, spreads have come in and sit near all-time lows. Are narrower spreads a sign of market complacency? Spreads have peaked at times of peak uncertainty (2009, aftermath of tech-wreck, early 80's).

October 23, 2014

Get Poor Quickly!

One of the best ways to measure how much luck is involved in the outcome of any competitive event is to ask how easy it would be to lose that event on purpose[i]. It would be very easy, for example, to lose a round of golf or a tennis match on purpose—implying that skill determines the outcomes in those sports, not luck. But what about investing? Here, the answer is less certain. Just as it’s hard to consistently pick stocks that beat the market, it is also difficult to consistently pick those that lose to the market.

But here is one strategy that you could have used to lose on purpose with great consistency over the past 50 years[ii]: every year, buy the 25 large cap stocks[iii] with the most expensive EBITDA-to-Enterprise-Value ratios and hold for one year. Rinse and repeat for 50 years.

If you had done so, you’d have lost money more often than the market (these stocks went down in 35% of 12-month periods, vs. just 24% for all large stocks), you’d have performed considerably worse overall than the market (5.6% annualized returns vs. 10.5% for all large stocks), and you’d have lived through a much more volatile ride (24.7% annual volatility vs. 15.9% for the market).

Here is the hard part. Many of the worst current offenders have been featured on 60 Minutes. They ignite our imaginations. They are damn exciting. Hidden within this list of 25 may be the next Google or the next Apple. The list includes Twitter, Tesla, Alibaba, and GoPro, to name just a few.

Still not convinced that buying these expensive stocks is a bad idea? This strategy of buying the most expensive stocks has underperformed the rest of the market in 87% of five year periods and 95% of 10 year periods. Would you play any game that had those odds? Investors do all the time.

The message here is pretty clear: Don’t buy expensive stocks. DON’T BUY EXPENSIVE STOCKS. DON’T BUY EXPENSIVE STOCKS!

That is unless you want to increase the odds of getting poor quickly.

[i] Michael Mauboussin explores this idea in depth in his great book The Success Equation

[ii] Starting in January of 1964 through June 2014

[iii] Those with market caps larger than the entire universe’s average, today that would mean a floor of roughly $7B

October 16, 2014

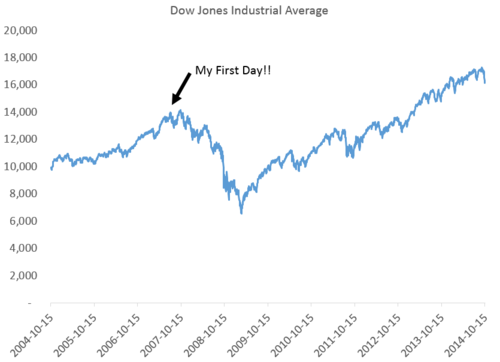

The Worst Time To Start In Finance

Getting started in finance and investing is hard if you never took a class on either topic in your life. That’s where I sat in the summer of 2007—fresh off a degree in philosophy and starting as an intern at O’Shaughnessy Asset Management. Full disclosure here: my start in the business was as classic a case of nepotism as you will ever find. My father was in the process of leaving Bear Stearns Asset Management and setting up O’Shaughnessy Asset Management, and offered me an internship. It was somewhat open-ended. It was unpaid. I never would have had that chance had it not been for the family connection. People bust their butts to get a first chance in the asset management business—I was just incredibly fortunate. In many ways I was like a member of Warren Buffett’s “lucky sperm club” who then went on to win the lottery.

Like most philosophy majors, I had no idea what I wanted to do, but I knew it would be downright foolish to miss the chance to help set up a new company at the ground level. This involved looking for office space, collating, and calling clients to walk them through the logistics of transferring their accounts.

This wasn’t exactly scintillating stuff, so I spent my spare time learning. Reading is my first love, so I read as many books as I could on investing strategy and investor psychology. I remember being floored by David Dreman’s Contrarian Investment Strategies. I realized that I wanted to understand markets, and I wanted to go into the research side of the business—so that is what I did.

This all seemed great between July 2007 and the summer of 2008. I was learning fast and enjoying myself. Sure the market appeared to be in a bad lull—off of the November 2007 highs—but as I’d read, this was normal. Markets ebbed and flowed.

Then disaster struck—no history lesson necessary. Right away we were in crisis mode, just like everyone else in the business. At age 23 I was sent out to explain to clients why they had half the money they did less than a year prior. We are a very active manager (meaning our portfolios look very different than the overall market) so in some cases we were doing even worse than the market. These were extremely hard conversations.

To get in front of as many clients as possible, I did many presentations to 50+ financial advisors. In one of my first presentations, I was trying to preach a focus on the long-term and the importance of discipline and sticking to one’s plan. Can you imagine being 50 years old and having a snot-nosed kid tell you to stay the course in November 2008? I tried to quote Goethe (“to say is easy, to do is hard, to do what you say hardest of all” or something like that). Only a punk philosophy major with limited experience would ever quote a German poet to people struggling with the fact that their financial life was in ruins. I was nervous as hell, forgot the quote, and stared in horrified silence at the audience for 10 seconds as I tried to collect myself. Suffice it to say I never quoted Goethe again.

A few months later, a colleague and I met with a financial advisor who refused to look me in the eye or shake my hand. I was the representative from the portfolio management team there to explain bad performance, and had my whole spiel ready. Instead of listening, the advisor asked my colleague what a “limp d—k little a—hole” like myself was doing in his office. He said I looked like I was 15 (I did) and had no business in his presence (I probably didn’t).

I mention all of this because I learned more about markets in those 12-months in front of clients than I did across all three levels of the CFA program. Markets are, at their core, about emotions and how you handle them. It is so easy to be brave from a safe distance, to say that you will be cool when the tough times come. During 2008-09, I learned that that is naïve bullsh*t. Those were terrifying times. I was worried to my core about my family’s future, the business, and all of our clients who had trusted us with their money. I convinced some to stay the course, but failed more often than I succeeded. I was yelled at a lot. I questioned my career choice. It is because of my tough early experiences that I spend more chapters in my book discussing investor psychology and emotions than I do discussing investing strategies. Strategy is important, but controlling your emotions is even more critical. It is what you do during markets like 2008 which determine your long term results.

For the first time in years, we have a choppier, down market. It has happened fast so far, as these things tend to:

There is no way of knowing how much more downside there is (if any). I do know, however, that if it gets worse, reason will be thrown out the window and emotions will regain their spot atop the market throne. Everyone will start to cherry pick all the bad facts and data about markets and the world. Advertisements on Zero Hedge will get more expensive. Schiff, Hussman, Rickards, and Faber will have their moment. System 1 will rise from its long slumber and crush System 2. Going to cash will be very tempting.

It is hard to act rationally as markets spiral downwards. For young investors specifically, this may be one of those rare chances to take advantage of volatility. Take your dollar cost averaging and up the amounts a little bit. Remember Buffett’s maxim that when you read a headline to the effect of “investors lose as market falls,” you should re-adjust that headline in your brain to “dis-investors lose as market falls, but investors gain.” Do that, and you’ll do well.

As Geothe said…(just kidding).

October 15, 2014

The years teach much which the days never know

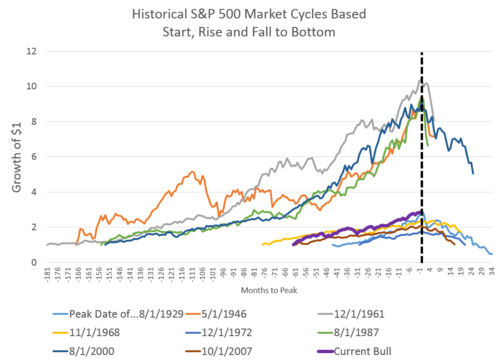

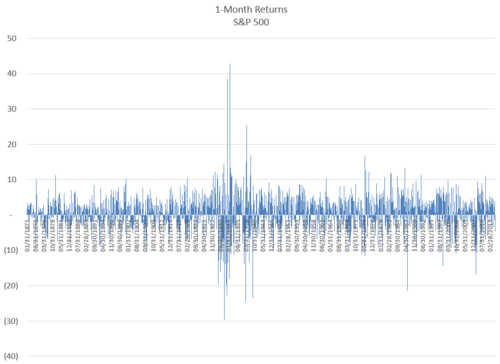

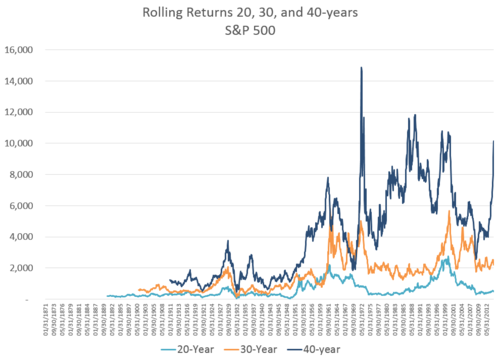

Here are the monthly returns for the S&P 500 since 1871. Chaotic. Sometimes terrifying. Sometimes very exciting. This is the market in which we live. These are the sometimes great and sometimes awful returns that make us greedy, euphoric, panicked, and fearful. These returns do not matter.

Source: Raw returns from Global Financial Data.

Here is what happens when you take these same monthly returns and compound them over 20-, 30-, and 40- years. These returns are hard to feel but they are the only ones that matter. If you are young, and you are a real investor, remind yourself that these long-term numbers are all that matter. This reminder is especially important on days like today, when the market is down 2.5%.

Source: Raw returns from Global Financial Data.

Frame things right, and you'll navigate the tough times just fine. Emerson said it best: "The years teach much which the days never know."

October 14, 2014

The Millennial Way Forward

If nothing changed about your current retirement plan, would you be able to easily support yourself and your loved ones come age 65? For many of my fellow millennials this is a sobering question. On the one hand, it is hard to think and plan four decades ahead. We are still young — scraping our way to better careers and salaries — so our focus is not on our twilight years, but on the here and now. On the other hand, we are cautious and worried about money because we have come of age during a rotten economy, and have watched the housing and stock markets crash, bringing financial ruin to those we love.

We are a generation obsessed with self-improvement. Most wake up in the morning and think, how can I improve my lot in life? Very few are just satisfied. Self-improvement is hard work, but luckily improving one’s personal financial situation is straightforward. It is one of the easiest ways to get better right away. The cruel irony is that we work tirelessly in our 20’s and 30’s to improve our careers and ourselves, but then spend so little time thinking about how to put our money and success to good use.

So far, a nice chunk of the millennial population has done something about long term financial planning: 43% of millennials have a 401(k) and 23% have an IRA. That is a good start, but it’s not enough. So how can millennials get started? The key is an education on the basics of money, personal finance, and investing.

Reaching millennials is tough because fully one quarter of them “trust no one” on money matters. Still, a large percentage — about one third — say that they trust their parents for advice on money. By laying some basic groundwork — either on their own or with encouragement from their parents — millennials can get off on the right foot and set themselves up for success.

The easiest way to understand the power of starting young is to focus on is the potential of every single one of your dollars.

The Potential of Each DollarWhat can every invested dollar grow to by the time you retire? The answer varies greatly depending on where and when you invest.

Those millennials that have saved and invested are very conservative with their money — opting for cash over stocks. The aforementioned stock market and housing crashes have been imprinted on our brains, and made us wary of “risky” investments like stocks. Because of our biological wiring, we are about twice as sensitive to losses as we are to gains. Once burned, twice shy as the saying goes — and we've been burned several times.

This biological imperative to be extra-sensitive to danger works great in a primitive, survival setting, but it wreaks havoc on our investments. Human nature compels us to sell after market crashes and buy at market peaks, even though we are supposed to be doing the opposite. These emotional reactions are very short-term in nature: our emotions make us avoid immediate dangers and pursue immediate opportunities.

The remedy is to redefine risk as a long-term rather than short-term concept. Here are four key lessons about the potency of your dollars.

The potential of every dollar fades quickly with time. If you start investing younger, you will harness the most important variable in the investing equation: time in the market. $1 invested in the stock market at age 25 has typically grown to $15 by retirement. The same dollar invested at age 40 has typically grown to $5 by retirement. Read that again. Dollars have typically had three times the potential when invested at age 25 versus age 40. Warren Buffett wasn’t a billionaire until he was sixty years old. He started investing when he was eleven. Step one, start young.

The potential of every dollar is maximized by spending long periods in the global stock market rather than in cash or bonds. If your time horizon is long enough — which it is if you are a millennial — then stocks have always trumped the alternatives. Millennials have built cash-heavy portfolios thus far, so consider the same potential of each dollar kept in cash (savings accounts, CDs). The average result for $1 invested at age 25 is growth to $1.20—a paltry return compared to the $15 from stocks. We think of bonds as the next safest option after cash, but the average $1 invested in bonds at age 25 has grown to $2.7. The long-term historical record is clear: stocks win out. Step two, if you are young, focus your portfolio in the stock market. Stocks are dangerous in the short term, but we are young so the short term is irrelevant.

The potential of every dollar fades the more often you check your portfolio. You are supposed to buy low and sell high. Most do the opposite. Human nature is great for many things, but investing is not one of them. The less you look at your results, the fewer chances you’ll have to screw yourself up. Step three, ignore short-term fluctuations in markets.

The potential of every dollar will be maximized if you make your investing automatic. Default options are powerful because we are lazy. If you automatically deposit a percentage of your income into your investment accounts (401(k), IRA, brokerage account), then you’ll build wealth without effort. Step four, automate contributions to your investing accounts.

The Way ForwardIf you just invest a little bit of time and planning early in your life, you can effect significant change in your long term financial health. You can set yourself up so that your answer to the question “if you changed nothing about your current financial plan, will you retire comfortably?” is a resounding yes. Nothing is as powerful in the world of investing as starting young.

Here is something you can do today: check out companies like Wealthfront, Liftoff, and Acorns. These companies sit at the intersection of investing and technology. Sign up today. Focus on stocks. Once you are set up, get out of your own way.

You’ll notice that a lot of this plan is simply protecting your dollars’ potential and letting them grow. But your dollars won’t work for you unless you get things started. Like millennials themselves, these young dollars are full of potential. They just need to be put to work.

For more on how to get started, check out my new book Millennial Money: How Young Investors Can Build a Fortune, which is on shelves today.