Patrick O'Shaughnessy's Blog, page 30

May 6, 2015

The Rise of the Robots And What To Do About It

Companies need fewer and fewer employees to generate each dollar of profit. This trend is likely to continue. The best thing you can do is focus on areas which are less likely to be automated away: entrepreneurship, art, creation, ideas, and innovation. Let’s explore what is happening and what you can do about it.

Martin Ford begins his solid new book Rise of the Robots with the following anecdote:

Sometime during the 1960s, the Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman was consulting with the government of a developing Asian nation. Friedman was taken to a large-scale public works project, where he was surprised to see large numbers of workers wielding shovels, but very few bulldozers, tractors, or other heavy earth-moving equipment. When asked about this, the government official in charge explained that the project was intended as a “jobs program.” Friedman’s caustic reply has become famous: “So then, why not give the workers spoons instead of shovels?”

It was nice of Ford to start the book with a chuckle, because the rest of the book made me progressively more anxious. I am not a political guy, but the question of how to deal with more and more technology, automation, and robots in the workplace is intriguing and important.

In this piece I highlight interesting trends in the amount of sales and net income earned by U.S. companies per employee. The bottom line is that fewer people are needed to earn each dollar of profit—and this relevant to profit margins, investors, and employees of all stripes.

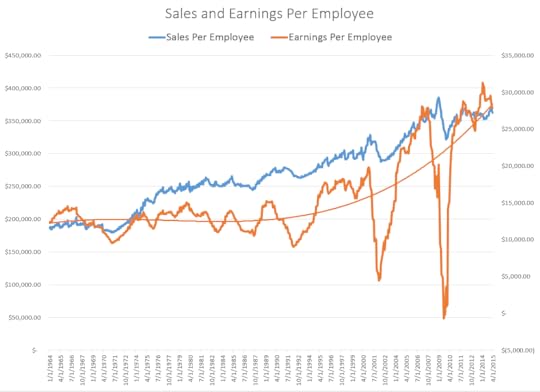

Here are the sales and earnings generated by each employee since 1963. I only include companies that 1) reported data for the number of employees and 2) reported sales data. This covers roughly 38 million employees today. Key point: all data is inflation adjusted to 2011 dollars. Since the early 1990s, U.S. companies have generated significantly more earnings per employee.

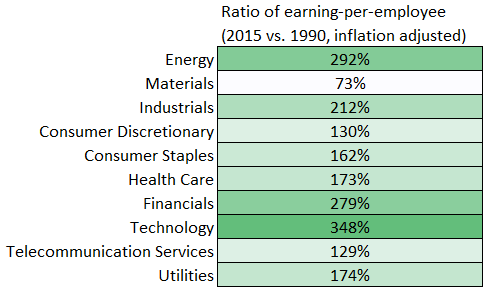

As we saw with profit margins within sectors, there are very interesting trends for earnings-per-employee at the sector level. Between 1990 and 2015, earnings per employee grew by 100% or more in all sectors except materials. Technology companies earn 348% more per employee today than in 1990. At the end of the post, you will find the time series charts for all sectors.

This is all good for business owners and ongoing employees, but could be quite awful for those being replaced (in part or in full) by technology of various types.

This isn’t just an issue for blue-collar workers:

One widely held belief that is certain to be challenged is the assumption that automation is primarily a threat to workers who have little education and lower-skill levels. That assumption emerges from the fact that such jobs tend to be routine and repetitive. Before you get too comfortable with that idea, however, consider just how fast the frontier is moving. At one time, a “routine” occupation would probably have implied standing on an assembly line. The reality today is far different. While lower-skill occupations will no doubt continue to be affected, a great many college-educated, white-collar workers are going to discover that their jobs, too, are squarely in the sights as software automation and predictive algorithms advance rapidly in capability… The fact is that “routine” may not be the best word to describe the jobs most likely to be threatened by technology. A more accurate term might be “predictable.” Could another person learn to do your job by studying a detailed record of everything you’ve done in the past? Or could someone become proficient by repeating the tasks you’ve already completed, in the way that a student might take practice tests to prepare for an exam? If so, then there’s a good chance that an algorithm may someday be able to learn to do much, or all, of your job.

One of my favorite automation examples in the book was Japan’s Kura sushi restaurant chain:

In the chain’s 262 restaurants, robots help make the sushi while conveyor belts replace waiters. To ensure freshness, the system keeps track of how long individual sushi plates have been circulating and automatically removes those that reach their expiration time. Customers order using touch panel screens, and when they are finished dining they place the empty dishes in a slot near their table. The system automatically tabulates the bill and then cleans the plates and whisks them back to the kitchen. Rather than employing store managers at each location, Kura uses centralized facilities where managers are able to remotely monitor nearly every aspect of restaurant operations. Kura’s automation-based business model allows it to price sushi plates at just 100 yen (about $1), significantly undercutting its competitors.

But this automation moves up the chain quickly:

Narrative Science’s technology is used by top media outlets, including Forbes, to produce automated articles in a variety of areas, including sports, business, and politics. The company’s software generates a news story approximately every thirty seconds, and many of these are published on widely known websites that prefer not to acknowledge their use of the service. At a 2011 industry conference, Wired writer Steven Levy prodded Narrative Science co-founder Kristian Hammond into predicting the percentage of news articles that would be written algorithmically within fifteen years. His answer: over 90 percent.

Most of the proposed solutions to job and wage stagnation are of the top-down variety (re-distribution of wealth, guaranteed income, granting of capital (shares in a mutual fund), etc.). But I am more interested in the bottom-up solutions, in what individuals can do to better their financial health.

Our options are to spend less and/or earn more (or at least earn steadily).

The former is simple: embrace material minimalism. I find this can be quite liberating. This isn’t a personal finance website, so maybe check this out.

To achieve the latter, two things stand out.

First, we should be investors and strive for more widely dispersed ownership of financial assets. We should buy shares in the corporations which have benefited from these trends in efficiency and profitability. Wages have basically gone nowhere since I was born in 1985. The stock market is up 2,000% (nominally, but still).

Second, we should focus on developing talent in areas that machines will lag. Machines are fantastic at answering questions, but humans are still much better at asking and discovering the questions in the first place. Humans are still better innovators, creators, and artists. But even this advantage is in doubt:

Most of us quite naturally tend to associate the concept of creativity exclusively with the human brain, but it’s worth remembering that the brain itself—by far the most sophisticated invention in existence—is the product of evolution. Given this, perhaps it should come as no surprise that attempts to build creative machines very often incorporate genetic programming techniques. Genetic programming essentially allows computer algorithms to design themselves through a process of Darwinian natural selection. Computer code is initially generated randomly and then repeatedly shuffled using techniques that emulate sexual reproduction. Every so often, a random mutation is thrown in to help drive the process in entirely new directions. As new algorithms evolve, they are subjected to a fitness test that leads to either their survival, or—far more often—their demise. Computer scientist and consulting Stanford professor John Koza is one of the leading researchers in the field and has done extensive work using genetic algorithms as “automated invention machines.” Koza has isolated at least seventy-six cases where genetic algorithms have produced designs that are competitive with the work of human engineers and scientists in a variety of fields, including electric circuit design, mechanical systems, optics, software repair, and civil engineering. In most of these cases, the algorithms have replicated existing designs, but there are at least two instances where genetic programs have created new, patentable inventions. Koza argues that genetic algorithms may have an important advantage over human designers because they are not constrained by preconceptions; in other words, they may be more likely to result in an “outside-the-box” approach to the problem.

I am no Luddite. I cannot wait to see what the future of technology holds–we will no doubt benefit in innumerable ways. But we will be better off if we spend less, invest the savings, and seek jobs that are about art, creation, ideas, and new combinations. Doing so, we stand the best chance of being protected as the robots continue to rise.

p.s. I will be writing more about the act of creation and innovation in the near future, so stay tuned.

Human Hardware and Human Software

Us humans have hardware and we have software. Our hardware (biology) evolves–very slowly–across generations. Our software (culture) evolves–very quickly–within generations. The difference in speed means that many aspects of our minds and bodies are vestigial: they we optimized for a very different environment than the one in which we find ourselves today. This helps explain why we eat like crap and why we tend to make poor investing choices. Our biology is optimized to hoard calories, so we love sweets and fast food. It is optimized to avoid danger, so we sell after market crashes, when we should do the opposite.

This is a pretty common argument these days. I’ve made it a lot, and I’ve heard it a lot. Even though I’ve grown slightly bored of the topic, I loved the book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari. Here, the author explains the curious nature of our rapid ascent:

It was only 400,000 years ago that several species of man began to hunt large game on a regular basis, and only in the last 100,000 years – with the rise of Homo sapiens – that man jumped to the top of the food chain. That spectacular leap from the middle to the top had enormous consequences. Other animals at the top of the pyramid, such as lions and sharks, evolved into that position very gradually, over millions of years. This enabled the ecosystem to develop checks and balances that prevent lions and sharks from wreaking too much havoc. As lions became deadlier, so gazelles evolved to run faster, hyenas to cooperate better, and rhinoceroses to be more bad-tempered. In contrast, humankind ascended to the top so quickly that the ecosystem was not given time to adjust. Moreover, humans themselves failed to adjust. Most top predators of the planet are majestic creatures. Millions of years of dominion have filled them with self-confidence. Sapiens by contrast is more like a banana republic dictator. Having so recently been one of the underdogs of the savannah, we are full of fears and anxieties over our position, which makes us doubly cruel and dangerous. Many historical calamities, from deadly wars to ecological catastrophes, have resulted from this over-hasty jump.

If technology is doing more with less, cooking ranks right up there:

The advent of cooking enabled humans to eat more kinds of food, to devote less time to eating, and to make do with smaller teeth and shorter intestines. Some scholars believe there is a direct link between the advent of cooking, the shortening of the human intestinal track, and the growth of the human brain. Since long intestines and large brains are both massive energy consumers, it’s hard to have both. By shortening the intestines and decreasing their energy consumption, cooking inadvertently opened the way to the jumbo brains of Neanderthals and Sapiens. Fire also opened the first significant gulf between man and the other animals… When humans domesticated fire, they gained control of an obedient and potentially limitless force. Unlike eagles, humans could choose when and where to ignite a flame, and they were able to exploit fire for any number of tasks. Most importantly, the power of fire was not limited by the form, structure or strength of the human body. A single woman with a flint or fire stick could burn down an entire forest in a matter of hours. The domestication of fire was a sign of things to come.

Lawyers, politicians, and businesspeople are modern day sorcerers, having conjured up constructs which exist because we believe in them, trust in them, and agree that they do, in fact, exist.

People easily understand that ‘primitives’ cement their social order by believing in ghosts and spirits, and gathering each full moon to dance together around the campfire. What we fail to appreciate is that our modern institutions function on exactly the same basis. Take for example the world of business corporations. Modern business-people and lawyers are, in fact, powerful sorcerers. The principal difference between them and tribal shamans is that modern lawyers tell far stranger tales… The sculptor from the Stadel Cave may sincerely have believed in the existence of the lion-man guardian spirit. Some sorcerers are charlatans, but most sincerely believe in the existence of gods and demons. Most millionaires sincerely believe in the existence of money and limited liability companies. Most human-rights activists sincerely believe in the existence of human rights. No one was lying when, in 2011, the UN demanded that the Libyan government respect the human rights of its citizens, even though the UN, Libya and human rights are all figments of our fertile imaginations… Ever since the Cognitive Revolution, Sapiens have thus been living in a dual reality. On the one hand, the objective reality of rivers, trees and lions; and on the other hand, the imagined reality of gods, nations and corporations. As time went by, the imagined reality became ever more powerful, so that today the very survival of rivers, trees and lions depends on the grace of imagined entities such as the United States and Google.

This is a tiny taste of a great book. Read it and you’ll better understand what makes us human.

If you are a fan of books, check out my book club: I send 3-4 of the best books I’ve read to you in an email each month, culled from the best of the 100 or so I read per year (you’ll also get an investor curriculum right away filled with books, articles, videos, and papers). You can sign up here.

April 27, 2015

The Investor's Field Guide

Starting today, I am embarking on one year journey through the stock market jungle. Here is a little preview of the new website:

All content on this site has been ported over to http://investorfieldguide.com/ and all inbound links will be forwarded there, beginning in a few days.

Thanks so much for reading over the past year, it is about to get better!

April 10, 2015

In Wildness is the Preservation of the World: The Thinking of Peter Thiel and H.D. Thoreau

There is a remarkable connection between two of my favorite thinkers—Peter Thiel and H.D. Thoreau. Each offers the same prescription for life, a prescription that we need more of today:

Live (and think) at the frontier, on the edge of discovery, not in the cozy establishment.

Favor radical discovery and exploration over incremental—and conventional—improvement.

Free yourself from the known, get lost in the hidden and unknown.

These passages are from Peter Thiel’s Zero to One and H.D. Thoreau’s essay Walking.

Thoreau: It is remarkable how few events or crises there are in our histories; how little exercised we have been in our minds; how few experiences we have had.

Thoreau: Hope and the future for me are not in lawns and cultivated fields, not in towns and cities, but in the impervious and quaking swamps.

Thoreau: My desire for knowledge is intermittent; but my desire to bathe my head in atmospheres unknown to my feet is perennial and constant. The highest that we can attain to is not Knowledge, but Sympathy with Intelligence.

Thiel: EVERY ONE OF TODAY’S most famous and familiar ideas was once unknown and unsuspected.

Thiel: The clearest way to make a 10x improvement is to invent something completely new. If you build something valuable where there was nothing before, the increase in value is theoretically infinite.

Thiel: You can’t find secrets without looking for them.

I think Thiel would agree that the best opportunities are “in the swamps.”

Thiel: As you craft a plan to expand to adjacent markets, don’t disrupt: avoid competition as much as possible.

Thiel: Indeed, if your company can be summed up by its opposition to already existing firms, it can’t be completely new and it’s probably not going to become a monopoly.

Thiel: Competition can make people hallucinate opportunities where none exist.

Both authors disparage the value of a conventional education (an attitude to which I am sympathetic):

Thoreau: In literature it is only the wild that attracts us. Dulness [sic] is but another name for tameness. It is the uncivilized free and wild thinking in “Hamlet” and the “Iliad,” in all the Scriptures and Mythologies, not learned in the schools, that delights us.

Thiel: The best place to look for secrets is where no one else is looking. Most people think only in terms of what they’ve been taught; schooling itself aims to impart conventional wisdom.

Thiel: The most contrarian thing of all is not to oppose the crowd but to think for yourself.

Thiel: All Rhodes Scholars had a great future in their past.

In this next grouping, think of Thoreau’s “West” as “zero to one” and “East” as “globalization” or “one to N”

Thoreau: We go eastward to realize history and study the works of art and literature, retracing the steps of the race; we go westward as into the future, with a spirit of enterprise and adventure…To use an obsolete Latin word, I might say, Ex Oriente lux; ex Occidente FRUX. From the East light; from the West fruit.

Thoreau: The West of which I speak is but another name for the Wild; and what I have been preparing to say is, that in Wildness is the preservation of the World. Every tree sends its fibres forth in search of the Wild. The cities import it at any price. Men plow and sail for it. From the forest and wilderness come the tonics and barks which brace mankind. Our ancestors were savages. The story of Romulus and Remus being suckled by a wolf is not a meaningless fable. The founders of every State which has risen to eminence have drawn their nourishment and vigor from a similar wild source. It was because the children of the Empire were not suckled by the wolf that they were conquered and displaced by the children of the Northern forests who were.

Thiel: The act of creation is singular, as is the moment of creation, and the result is something fresh and strange… the best paths are new and untried.

Thiel: The paradox of teaching entrepreneurship is that such a formula necessarily cannot exist; because every innovation is new and unique, no authority can prescribe in concrete terms how to be innovative.

Thiel: Indeed, the single most powerful pattern I have noticed is that successful people find value in unexpected places

Thiel: There are two kinds of secrets: secrets of nature and secrets about people. Natural secrets exist all around us; to find them, one must study some undiscovered aspect of the physical world. Secrets about people are different: they are things that people don’t know about themselves or things they hide because they don’t want others to know. So when thinking about what kind of company to build, there are two distinct questions to ask: What secrets is nature not telling you? What secrets are people not telling you?...Secrets about people are relatively underappreciated. Maybe that’s because you don’t need a dozen years of higher education to ask the questions that uncover them: What are people not allowed to talk about? What is forbidden or taboo?

Thiel: At the macro level, the single word for horizontal progress is globalization—taking things that work somewhere and making them work everywhere. China is the paradigmatic example of globalization; its 20-year plan is to become like the United States is today…The single word for vertical, 0 to 1 progress is technology. The rapid progress of information technology in recent decades has made Silicon Valley the capital of “technology” in general. But there is no reason why technology should be limited to computers. Properly understood, any new and better way of doing things is technology… most people think the future of the world will be defined by globalization, but the truth is that technology matters more. Without technological change, if China doubles its energy production over the next two decades, it will also double its air pollution. If every one of India’s hundreds of millions of households were to live the way Americans already do—using only today’s tools—the result would be environmentally catastrophic. Spreading old ways to create wealth around the world will result in devastation, not riches. In a world of scarce resources, globalization without new technology is unsustainable.

Thiel and Thoreau are great, but it is hard to top yet another author with a “T” surname.

The Road goes ever on and on

Down from the door where it began.

Still round the corner there may wait

A new road or a secret gate,

And though we pass them by today,

Tomorrow we may come this way

And take the hidden paths that run

Towards the Moon or to the Sun.

The road doesn’t have to be infinite after all.

Take the hidden paths. – J.R. Tolkien

So where are the hidden paths? This is the million (or billion) dollar question. As many great creative thinkers have said, the hard part is to find the right problem/ask the right questions.

For now, I can offer one suggestion: journey inward. We spend so much time collecting information so that we can know more, but tend to spend very little time getting to know the knower.

Having spent many hours across several years developing a meditation practice, I can attest that inward exploration is equally difficult and rewarding.

The mindset that slowly develops with a consistent meditation practice is compatible with wildness and the existing on the frontier. You learn to look at the world with a fresh, open set of eyes. Meditation helps you develop what’s known as a “beginner’s mind,” a mind unencumbered by convention and accumulated baggage. I’ve noticed I use two words a lot more now: “why” and “no.” These two words, used liberally, are powerful. They’ve made me happier. I think they can do the same for you.

P.S. can you believe I got through a Thiel post without asking/quoting “what important truth do very few people agree with you on?” Oh wait, I already did that post.

March 26, 2015

Lessons for Investors and Entrepreneurs: The Nature of Value

It is always fun to read a book that is useful for investors and entrepreneurs/businesspeople. Nick Gogerty’s The Nature of Value covers a lot of ground—below I quote and highlight some of the most useful lessons and idea from the book. I also met Nick last week, and it helps that he is a very nice and smart guy.

VALUE, IN THE SIMPLEST sense, is the human perception of what is important. As such, it is subjective and context dependent.

I have to remind myself often that market prices are a collective opinion or perception, and that the only sustainable advantage in investing is finding perception (price)/reality gaps. The book talks a lot about changes in the perception of value, and how quickly a hot technology can fade away, its value diminished.

Evolution…favors the energy efficient.

all things can be considered dissipative structures—that is, all forms evolve for energy to flow through at increasing levels of efficiency. We will see that the study of evolution across economic and ecological domains is actually the study of dissipative structures adapting over time and through selective processes.

I love Peter Thiel’s definition of technology which “to do more with less.” This is a key lesson for the entrepreneur (companies like Uber and Airbnb--efficiency machines--best exemplify these ideas), but also for businesspeople. Companies tend to add layers of bloat over time and must constantly fight this slowly accumulated business baggage. It’s very hard to innovate as companies get older and older. Gogerty continues:

Innovation, as suggested, is both a giver and a destroyer of value. The entrepreneur—and society—sees innovation as a positive option that can potentially deliver new forms of value. But innovation expressed outside one’s own firm is a negative option viewed from the firm’s perspective. A competitor’s positive option can kill other firms. This negative optionality is unpredictable and extremely difficult to avoid. The allocator must guess the scope and scale of negative options that may be created by others. Firms with well-known fat margins can become negative option magnets, attracting entrepreneurs.

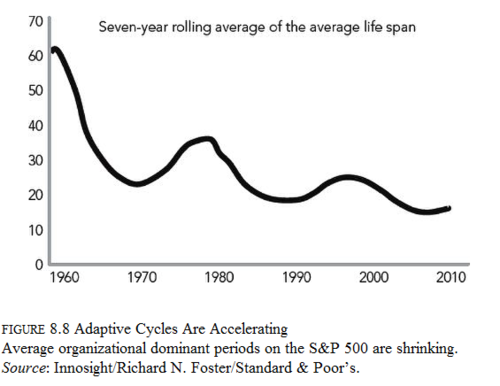

Negative options look like radical innovation to existing competitors. James M. Utterback, an MIT professor of innovation, has done in-depth innovation research and said the following about radical innovation and corporate death. A product’s life could end quite suddenly with the appearance of a radical new competing product that invades and quickly conquers the market. Not many firms have the dexterity to retool their capabilities in order to survive successive waves of innovation. Over the life of a product, few of the firms that enter the market to produce the product survive. Firms holding the largest market share in one generation of a product or process seldom appear in the vanguard of competition in the next.

This means that, surprisingly, no technology leader managed to hold onto the lead in the next iteration. For an investor in the technology sector, the leading firm must provide incredibly high returns on equity due to the short value-creating life span. Innovation-led companies are often severely overpriced, with little regard for the forces of negative optionality that lead to short life spans. Looking at the big picture over time makes this obvious. Focusing on today’s single “lottery ticket” firm ignores the silent negative options held by others.

One of the best finds in the book is a list of ten aspects of innovation made famous by the Doblin Group. If you work at a business or plan on starting one, going through this list is very valuable. Check it out here. You want to be unique in as many of these ten ways as possible. Having just one or two advantages probably won’t cut it:

Businesses that rely on a single unique capability for market share or margins are highly vulnerable to negative optionality (we explore businesses like this in chapter 6, in the discussion of “hero products”). Many technology firms fall into this category, and thus are weak candidates for sustainable value creation and capital allocation. Paradoxically, many of these firms are mispriced at high earnings multiples.

This story about Mark Twain reminds me of the cautious tale of automobile companies (which consolidated from more than one hundred to three major companies). Someone with a crystal ball about future technology might still fail to make any money from their knowledge of the future because competition is so fierce and it is hard to pick the winners!

History is filled with famous lottery ticket betters. The author Mark Twain was an early venture capitalist. He correctly saw the potential of the early typewriter, and invested in it. The typewriter flourished as a smash hit product for over a century, but the particular firm Twain bet on didn’t last long. Twain lost so much money he was forced to go on a global speaking tour to recoup his losses.

I also found lots of subtle references to the idea of shareholder yield investing (which is a preference for disciplined capital allocation).

Investors should beware, as well, of firms that are pushing innovation simply for the sake of innovation. This is usually nothing more than costly activity, driven by fear, masquerading as productivity. Bad innovation like this happens all the time, and is endemic at firms where analysts, boards of directors, and shareholders insist on “pushing the envelope” and keeping up with R&D initiatives regardless of the return on invested capital (ROIC). Activity like this may push share prices up in the short term, but it does not create value.

A typical organizational response to the cluster death process is to fight to the last penny even as it destroys shareholder equity, which is perversely considered more noble than quitting and handing back shareholder capital.

Allocators should seek long capability-cycle processes with fast, efficient cash flow turnover cycles. Expanding on the biological metaphor, bet on a slow, stable niche and a stable, quick-learning species within that niche that survives and thrives relative to others.

Our research shows that these ideas are right. Companies paying down stakeholders (buybacks, debt payback) significantly outperform those issuing new capital.

Finally here are some fun fast quotes from the book. I highly recommend it.

Remember Henry Ford’s saying that many people missed opportunity, because it showed up dressed in overalls and looked like work. [I always thought this was Edison, but forget it, he’s rolling]

Having the best product doesn’t matter. Efficiently delivering the best perceived user experience is what determines survival.

A cheap ticket on a sinking ship is never cheap enough to make the ride worthwhile. [i.e. a value strategy can probably be improved using other metrics—avoid the absolute worst quality can help in some situations…more posts on this in the future]

I suggest books like this once per month to members of the book club, you can sign up here.

March 25, 2015

How Expensive Are Expensive Tech Stocks?

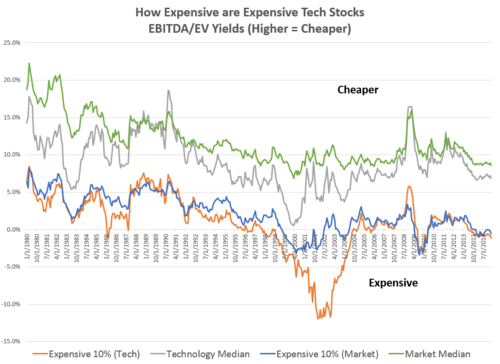

The answer: not much more expensive than OTHER expensive stocks in the market. Granted, this is all based on publicly traded companies, not privately funded start-ups. If I had a thorough history against which to compare current fintech or other start-up valuations this might look quite different.

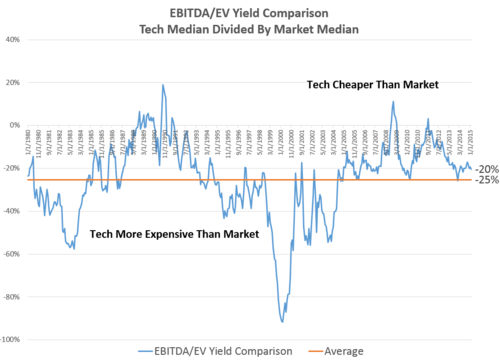

But here is the story. This chart shows the EBITDA/EV yield (higher = cheaper) for both tech stocks and the overall market. On top is the median valuation for tech vs. market, and on bottom is the EBITDA/EV yield for the most expensive 10% of tech vs market. You can see that in the late 90's/early 00's expensive tech stocks were MUCH more expensive than expensive stocks in the market in general. Not so today.

Its also fun to look at the median valuation difference between tech and the market median. Tech is typically 25% more expensive, and today is 20% more expensive based on EBITDA/EV yield.

Doesn't exactly scream bubble, does it!

March 17, 2015

Art And Fear And Investing

“I must not fear. Fear is the mind-killer. Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration. I will face my fear. I will permit it to pass over me and through me. And when it has gone past I will turn the inner eye to see its path. Where the fear has gone there will be nothing. Only I will remain.” Dune, by Frank Herbert

Fear—in its many forms—is our worst enemy. It’s true in life, and it’s true in investing. Natural selection has imbued us with an over-sensitivity to all things negative or dangerous. This aversion to loss has helped us survive, but it hurts us in many other ways. it lets fear reign. So what to do about it? A great place to start is to read Art & Fear: Observations on the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking by David Bayles, Ted Orland.

Art-making—which also comes in many forms—is one way to fight fear.

In large measure becoming an artist consists of learning to accept yourself, which makes your work personal, and in following your own voice, which makes your work distinctive.

The most important point in the book is that art-making won’t happen without persistence. In all my reading on creativity, genius, success, and happiness, persistence is sited again and again as the secret ingredient. In investing too, sticking to one’s investment strategy is the most important thing. You can have the best investing strategy in the world, but without persistence to match, you’ll never be a great investor.

talent is rarely distinguishable, over the long run, from perseverance and lots of hard work.

THOSE WHO WOULD MAKE ART might well begin by reflecting on the fate of those who preceded them: most who began, quit.

To see far is one thing: going there is another. — Brancusi

Throughout the book, I was constantly asking myself, is investing an art or a science? It seems to be a bit of both.

“The main thing to keep in mind,” as Douglas Hofstadter noted, “is that science is about classes of events, not particular instances.” Art is just the opposite. Art deals in any one particular rock, with its welcome vagaries, its peculiarities of shape, its unevenness, its noise. The truths of life as we experience them — and as art expresses them — include random and distracting influences as essential parts of their nature. Theoretical rocks are the province of science; particular rocks are the province of art.

There is room for both, I believe. The success of quantitative strategies suggests that there is a science to investing. The success of history’s best fundamental investors (Marks, Klarman, et al) suggests there is also some art. What do these two types of successful investors have in common? They are fearless. To beat the market, you’ll need to be very different. If you are very different, you’ll occasionally be very wrong. To endure periods of being wrong, you cannot fear.

Fears arise when you look back, and they arise when you look ahead.

When asked to list their top regrets, dying hospice patients gave this as their most common response: “I wish I'd had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.” Being an artist is a way around this regret.

But while others’ reactions need not cause problems for the artist, they usually do. The problems arise when we confuse others’ priorities with our own. We carry real and imagined critics with us constantly — a veritable babble of voices, some remembered, some prophesied, and each eager to comment on all we do.

To thine own self, be true. Easy advice to give, very hard advice to follow. But living (and investing) according to your needs, your goals, your joys will certainly be better than worrying about what everyone else is doing or thinking. I think this book should have been called Art Kills Fear. Go read it.

You can receive suggestions like this one once per month if you sign up for the book club that I manage. I’ll send you 3-4 suggestions every month, culled from the 100 or so books I read per year.

March 12, 2015

Does Value Still Work?

Everyone knows about value investing now, and everyone is tilting towards value, so its going to stop working. Everyone is saying this to me lately--sometimes as a question, sometimes as a statement of fact.

Yogi Berra famously said, "no one goes to that restaurant anymore, its too popular." Is the same thing happening to value?

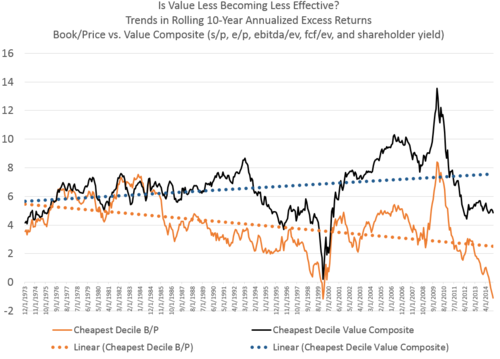

The most common definition of value, courtesy of Fama/French, is book/price. But book/price has many limitations. It is not as effective as a combination of other factors which work better in large cap (B/P works best in illiquid small/micro cap). We prefer a composite factor (equally weighted calculation using s/p, e/p, ebitda/ev, fcf/ev and shareholder yield).

Here are the rolling 10-year excess returns (versus an equally weighted benchmark) for two value factors: book/price and the value composite. You can see that 1) the composite is vastly superior to B/P alone and 2) the very simple trend lines are moving in opposite directions.

I don't read a ton into the declining B/P trend line. I think that value works because it exploits behavioral issues in the market and because so few investors can stick with it. Case in point, a book to price value investor has underperformed for the last 10 years. I still think even B/P will work in the future. But the data from the value composite debunks this idea that value is dead.

March 6, 2015

What Millennials Want (Or, How You Can Win Their Business)

Millennials are still in the very early stages of market participation: those under 35 own just 4% of mutual fund assets, but the 80-90 million millennials will soar in importance to everyone in the wealth/asset management business before too long. Through inheritance alone, millennials stand to receive $30 trillion in the next few decades. Where they start will often be where they grow. Some, like Wealthfront and forward thinking financial advisors, are tapping into this young potential already. So, if you are in the financial services business, how can you do the same?

I’ve learned a lot about young people and what they want since publishing Millennial Money late last year, and I believe these findings are relevant for financial advisors, millennial investors, and all those trying to win their business. The book has given me great access. Here’s what I’ve learned.

Young People Don’t Trust You

Millennials have a big issue with trust. In a very recent survey of wealthier millennials, just 19% agreed that advisors in general have their clients’ best interests at heart. 40% actively disagreed with this notion. Millennials are selfish (in a good way): with everything they buy, they want to know they are getting the most value possible for the price. In this same survey, 72% of them responded that they are “self-directed” investors and 41% said they’d received no financial advice.

Most of the millennials in this survey had more than $3M to invest and more than a quarter of them had more than $10M. They equated advisors with salesmen.

The solution is to educate them, rather than sell them. I like the idea that “when you sell, you break rapport, but when you educate, you build it.” [i]

This education can come in many forms. Regular white papers, commentary, blog posts, even twitter messages that teach investors why your style of investing/way of doing business makes sense and will work. If you are a financial advisor, do an event with your clients AND their children. The single most effective event I’ve done was a night at a club in LA, hosted by one of the best advisor teams we work with. I made a short presentation to 50 or so young people, many of whom were the children of the advisor’s top clients. These people were extremely hungry to learn, but just hadn’t had the chance or the time. I’ve heard from many of them since that night and two things stand out. One, they want to hear more about investing strategies, and two they want to build a relationship with an advisor who can help them learn.

Education is key. It builds trust and can secure multi-generational relationships.

Young People Like Three Key Attributes In Investing Strategies

A specific style of investing strategy resonates with millennials. Three criteria stand out: these strategies are rules-based, transparent, and mindful of fees and costs. Millennials have thus far liked index funds because they meet these criteria so well. I am naturally a bit biased given that O’Shaughnessy Asset Management manages quantitative/systematic strategies. We like to think that we are marrying the best aspects of active and passive investing: the disciplined, consistent, rules based approach of an index with a much more effective strategy based on principles like valuation, quality, momentum, and total yield.

Millennials like index funds, but they also like systematic strategies. I won’t explore Smart Beta here, because it means so many things, but the idea of a rules-based, systematic strategy has resonated well with young investors. They can understand it because they understand the rules. They are transparent. They tend to charge reasonable fees. Only 20% of wealthy millennials though that fees in our business were reasonable. Reaching them with these kinds of strategies works. They like index funds, but are also open to active strategies.

Young Investors Will Demand Automation—So Embrace Technology Now

Have you tried signing up for Wealthfront or Acorns? I have. It’s insanely easy. I get physically uncomfortable and annoyed when I want something and I can’t get it easily—in under 10 minutes, from my iPhone, sitting on my couch. And I am probably on the patient end of my generation. We are spoiled rotten by technology, so financial services solutions need to be easy, accessible, and fast as possible. Obviously there will be limitations depending on your line of business, but the smoother and easier and more automated you can make the experience the better your chances with millennials now and in the future.

If you run a business and don’t have a programmer, hire one. If you have one, hire more. At O’Shaughnessy Asset Management, our large programming team has become the lifeblood of our firm. We are quantitative investors who test myriad different strategies on historical data. Back in 2007, when I had an idea that I wanted to test, it took me roughly 36 hours to set up the test, run the historical simulation, collect the results, and perform the analysis. That same sequence takes me about 10-15 minutes today. I can answer just about any question about market history in minutes because of the technology at my fingertips. Doing the same in your business by automating as much as possible can make a huge difference. Imagine if all the repetitive tasks associated with your business went away, and imagine the time that would free up to focus on the areas where you are really skilled. These kinds of tasks are a hassle, removing them is good for you.

I am no proponent of modern portfolio theory or the efficient market hypothesis, yet I still send tons of people to Wealthfront. I do so because it is so easy that I know people will actually get started, and because friends who have $10,000 to invest will appreciate the very solid service. It’s not perfect, but it’s infinitely better than doing nothing. In ten years, those same people might have $1,000,000 with the same company.

Don’t Be Evil, Be Human

I am repentant for my former skepticism of blogs and twitter. For a long time I thought they were unprofessional. I couldn’t have been more wrong. These venues sync up with the millennial audience so well. They are transparent, they build trust, they help you educate your audience, and to connect with them in a way that is human, not just professional.

I think that is all young people (or maybe just people) really want: helpful services, charging fair prices, offered by people who are fundamentally good and honest.

It is amazing how different the world of finance is. Here is a passage from Tragedy and Hope (an amazing history of the early 20th century), about banking and the bankers that more or less ran the world:

“they remained as private unincorporated firms, usually partnerships, until relatively recently, offering no shares, no reports, and usually no advertising to the public…This period, 1884-1933, was the period of financial capitalism in which investment bankers moving into commercial banking and insurance on one side and into railroading and heavy industry on the other were able to mobilize enormous wealth and wield enormous economic, political, and social power. Popularly known as “Society,” or the “400,” they lived a life of dazzling splendor. Sailing the ocean in great private yachts or traveling on land by private trains, they moved in a ceremonious round between their spectacular estates and town houses in Palm Beach, Long Island, the Berkshires, Newport, and Bar Harbor; assembling from their fortress-like New York residences to attend the Metropolitan Opera under the critical eye of Mrs. Astor; or gathering for business meetings of the highest strategic level in the awesome presence of J. P. Morgan himself.”

Some might argue that this still happens to some extent today. But remember that when millennials were asked to identify their ten most hated brands, the four big banks all made the list.

Google’s motto “don’t be evil” is a great starting point for the financial services industry today.

Getting Them to Act Is the Hardest Part

Usually we need to be discontent or frustrated to take action. The further away a problem is in time, the less motivated we are to do something about it. The problem should be clear: millennials have decades before retirement.

The philosopher Eric Hoffer wrote an amazing book on mass movements called The True Believer, which I recommend to everyone. In the book he says, it is not the distant kind of hope, but the “around-the-corner brand of hope that prompts people to act.” It is so hard to envision a period 40-50 years in the future, and even harder to get people to act for a reward so distant. I’ve learned this firsthand the hard way. I spent too much time selling young people on 40-year returns, trying to appeal to their reason. They all nod their heads, agree, and then do nothing.

Instead I should have been appealing to emotions and immediate needs. If you are an advisor, don’t just sell the potential for long term wealth (although that is good), but also the benefits of working with you that they will feel immediately that may be frustrating them now.

Think of Maslow’s pyramid, his hierarchy of human needs. People will act most readily to satisfy their most basic needs. In the case of investing, shelter is key. Millennials need the equivalent of a financial shelter, but with a negative 2% savings rate, they aren’t building financial shelters. I think introducing first the idea of building a financial shelter—to cover short term needs when they arise—is a powerful way to get millennials interested and started saving.

Investing comes next. Again, a 40 year compound growth number sounds great, but it doesn’t precipitate action. So frame it differently. We are twice as sensitive to losses and negative things as gains or positive things. Frame the need to invest negatively. Don’t say invest with me and you’ll be rich in 40 years. Say save and invest more now and you won’t risk being without support now and in the future. You might think this is a slimy sales tactic, but it’s not. Anything that gets young people started sooner is a good thing.

Consider this. Two groups were asked to explore a virtual world using virtual reality goggles. In the virtual world, the members of each group eventually came across a mirror which showed either their current face or a version of their face which had been digitally enhanced to make them look like what they will at age 70. When asked later in the experiment, the group which saw the aged photos said they’d plan to save at twice the rate as those which saw the normal photos. The effect of the aged photo made them emotional but also made old age seem closer, and more immediate. These are useful lessons in motivation.

Playing the Millennial Long Game

Young investors haven’t built up a huge collective fortune—so right now they are not the biggest or most important clients. By time will take care of that. Should robo-advisors—who are counting on riding this millennial wave—be valued at the multiples they are? As a group, probably not. But one or more of them will be huge because they are finely tuned in to the preferences of their current and prospective clients.

I believe that the profile of a firm or strategy that will win millennials’ business and help them succeed is as follows. It will use technology to automate as much as possible and make working with the company easy and efficient, because millennials will demand it. It will be transparent and good. It will focus on rules based asset allocation and selection strategies with low fees. Finally, it will deal with them in a way that educates and builds trust and provides not just solid long term results, but also immediate help in areas that millennials are frustrated.

As Gretzky always said, skate to where the puck is going.

Sources:

http://www.pbig.ml.com/Publish/Content/application/pdf/GWMOL/ARDJPSCD.pdf

http://www.fastcompany.com/3027197/fast-feed/sorry-banks-millennials-hate-you

http://www.npr.org/2012/04/11/150424912/your-virtual-future-self-wants-you-to-save-up

http://www.wsj.com/articles/savings-turn-negative-for-younger-generation-1415572405

http://www.ici.org/pdf/2014_factbook.pdf

[i] I believe this was from Chet Holmes, but cannot remember for sure.

March 5, 2015

Why The Grandpa Portfolio Will Crush The Millennial Portfolio

Ever heard that joke about how if you are young and you aren't a democrat, you have no heart, but if you are old and you aren't a republican, you have no brain? Well, there seems to be something similar happening with the portfolios of young and old investors. Stocks with the youngest median owners are very expensive (but so exciting!), but stocks with the oldest median owners are much more fairly valued.

I spoke at the CFA's 2015 national Wealth Management conference yesterday on the topic of "Millennials and Money" and sadly, I had to report that millennials are making three big mistakes: they aren't saving enough (-2% savings rate), their asset allocation is back asswards (very heavy on cash, light on stocks), and their stock selection stinks.

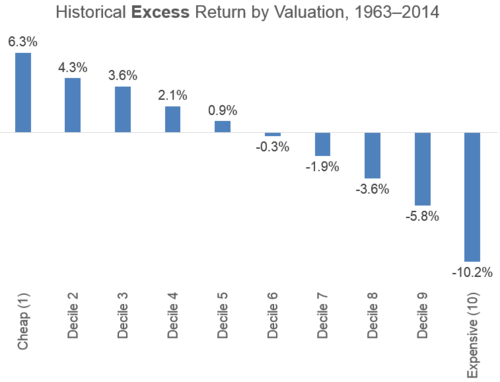

It is this third category--poor stock selection--that I found most interesting. First, a quick reminder of how powerful valuations are for predicting future stock returns, on average. Value here is a combination of P/E, P/S, EBITDA/EV, FCF/EV and Shareholder Yield (deciles rebalanced annually).

By just buying the cheapest stocks, you can significantly outperform over the long term (much easier said than done). Expensive stocks do so poorly that they have delivered a negative real return (after inflation). Simply put, you shouldn't buy expensive stocks (even though some of them crush, the group gets killed).

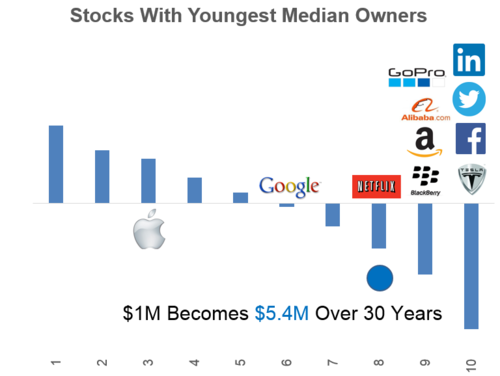

So now let's plot the stocks that have the youngest median owners (this is according to data from SigFig, which tracks 2.5 million portfolios representing about $350 billion in assets...their data is awesome). Look where they fall on the value spectrum.

I wasn't surprised by these (although I'm not sure what Blackberry is doing there...), but the key point is how expensive they are, on average. If you take them as an equal weighted portfolio, they are priced in about the 80th percentile of the market. Not good. Stocks in this valuation decile have done poorly through history. An average 30-year return would turn $1M into $5.4M (nominal).

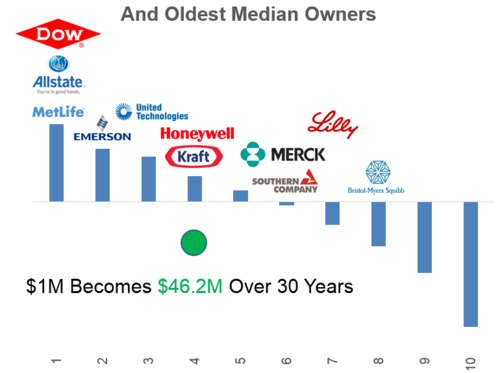

Now, let's contrast the millennial portfolio with the boring (but much better valued) grandpa portfolio:

This group of stocks is about as exciting as watching paint dry. And yet, taken as a group, it is priced to do much better than the millennial portfolio. Using the average historical return for stocks falling in a similar valuation bucket, the grandpa portfolio would grow from $1M to $46.2M over 30-years.

Millennials are notoriously skeptical of the market, but have started dipping their toes in with stocks that they know and love. Unfortunately, these stocks are priced to do poorly. Millennials should embrace value investing, but value stocks are no fun. Returns earned from value stocks, however, are quite fun indeed. Millennials could learn a lot from their grandparents.