Patrick O'Shaughnessy's Blog, page 27

September 3, 2015

25 books on how to think & create, be yourself, communicate, and learn from others

I learned more reading these 25 books than I did in four years of college. I think you will too.

These books—in four parts—are about thinking & creating, being happy and authentic, communicating, and learning from others.

I plucked these books from the 1,000+ that I’ve read. They have all made me better at what I do and have helped to make me a happier person. I hope they do the same for you.

I suggest you view in full screen by hitting the button on the bottom right:

July 31, 2015

Is Dividend Yield Still A Value Factor for U.S. Stocks?

Value factors rely, for the most part, on some comparison between current price and some fundamental measure of a company’s production like sales, earnings, or cash flow. Dividend yield—dividends paid divided by price—has been in the stable of value factors for a long time. But does a high dividend yield indicate cheapness for a U.S. company? Or do we need to incorporate other value factors when identifying attractive high yield companies? Let’s investigate.

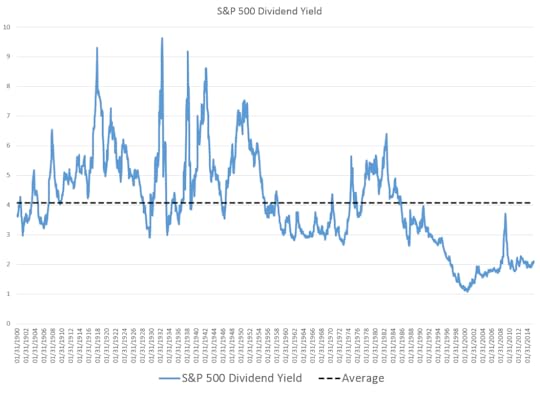

Here is the monthly dividend yield for the S&P 500 since 1900.

This chart is a little unfair, because it ignores return of capital to shareholders through share repurchase programs, which have become the more popular method. I’ve written a lot about buybacks here, here, and here.

Still, to get the capital return from a buyback program, you need to sell shares. Dividends are easier, steadier, and more reliable—and many investors prefer them. So the paltry yield available from the S&P 500 raises an interesting question. Is yield a good measure of cheapness? Short answer, for U.S. companies, is not anymore.

To see how that has the dividend yield factor has changed drastically since 2000, we can break all large U.S. companies into four distinct buckets by their dividend yield. Those buckets are 1) a dividend yield of zero, 2) a yield between 0-2%, 3) a yield between 2-4%, and 4) a yield above 4%. First, as we did with buybacks, let’s see how much of the total dividend pie is paid out by companies in these four buckets back to 1972 (when our data begins).

You can that in the 70’s—when the overall market’s yield was much higher—that most of the dividends being paid came from companies with a yield higher than 4%. But as time progressed, those high yielders represented a smaller piece of the overall pie. Visualized a little differently, here is the percent of companies in each yield bucket. The percent of companies without a dividend has risen, the percent with a higher yield (4%+) has fallen, and more companies pay a small yield (between 0-2%).

Now let’s turn to the valuations of these buckets through time. To evaluate cheapness, we calculate an independent value factor using sales, earnings, EBITDA, and free cash flow compared to prices and enterprise values. We calculate value it two ways: 1) comparing each stock to all other stocks, and 2) comparing each stock to other stocks in the same sector. This leaves us with a percentile score 0-100, where 0 means extremely cheap and 100 means extremely expensive relative to other stocks. Here is the rolling valuation of the various dividend buckets since 1972.

One trend is somewhat stable: companies without a yield tend to be more expensive than other stocks. But the more interesting trend is in the high yielders. Their valuation advantage has collapsed. Prior to the financial crisis bottom (pre-2009), the higher yielders were cheaper than the next bucket (2-4% yield) 92% of the time. Since 2009, they’ve only been cheaper 30% of the time. This is impossible to confirm, but the easiest explanation is that investors (especially older ones) have needed more income in this low rate environment, and have bid up the valuations of high yielders.

The story is quite similar (although not quite as extreme) if you calculate value relative to stocks in the same sector only.

This means that since 2000 or so, the highest yielding stocks (4%+) in each sector haven’t had a valuation advantage relative to other stocks in their sector, which they did on average prior to 2000.

Finally, we can chart the correlation between our two key data points: current dividend yield and current valuation percentile (market relative). Here it is since the peak in interest rates in 1981. Since 2001, it has been in a clear downtrend. Since the market peak in 2007, there has not been a meaningful relationship between yield and other measures of cheapness.

Conclusion

The implications for investors are as follows:

Don’t assume that high yield means a company is cheap here in the U.S.

If you are a value investor considering yield payers, use independent measures of valuation in your screening process.

Consider looking beyond just the U.S.—which only represents about 1/3 of the global dividend pie—when searching for higher yielding companies.

More generally, you should never rely on a single factor when making decisions about a company. I’ve discussed valuation, momentum, quality, and yield extensively on this site. Using all or some of these factors in combination has been a much more effective and consistent approach to stock selection through history than using a single factor. Yield can be good, so long as you are mindful of other important attributes of the companies in question.

P.S. thanks to Meb Faber (@mebfaber) for suggesting I write a piece on dividends similar to the one I wrote on buybacks.

The story is quite different in international markets, but that will be a different write-up

All U.S. companies that are both listed and domiciled in the U.S. so no ADRS, with market caps larger than the current market average. Today that is a floor of $7.5B or so, leaving roughly 500 companies.

July 28, 2015

Under-the-Radar Investment Books

I cannot find a good new investing book. It’s driving me nuts. Maybe you are in the same boat? If so, here are several “under-the-radar” books from my Evernote archives. If you know of more, leave suggestions in the comments. If you want to receive suggestions like this every month, sign up for the book club over here.

Rational Expectations: Asset Allocation for Investing Adults (Investing for Adults Book 4) by William Bernstein

I really like all of William Bernstein’s books. This is a recent favorite, which is a short and readable e-book. Here are some fun passages:

Oh, yes, and one more thing. Make sure, absolutely sure, that you have enough riskless assets to tide you over during the bad times, when you are the most likely to see your income fall or even lose your job. Preferably, you should have yet more than this, so as to take advantage of that high exchange rate when it shows up, as it inevitably does. Even more simply: you must have patience, cash, and courage—and in that order. All else, as Hillel said, is commentary.

This is no small point: how much liquidity you have when blood runs in the streets is likely the most important determinant of how successful you’ll be in the long run, since this is the time you’re most likely to lose your job, need cash to purchase stocks on the cheap, or buy the corner lot you covet from your impecunious neighbor.

This likely goes double for “tilted portfolios,” the term used for small-cap- and value-oriented stocks. I’ve already alluded to how much of a fiction some of the time series in tables 1-1 and 1-2 are. Before about 1980 or so, a diversified list of small and value stocks was nearly impossible to assemble. For example, in the late 1930s, a young John Templeton decided that small stocks were a bargain and put together a portfolio consisting of the 100 companies selling on the New York and American stock exchanges for less than a dollar per share (market cap data, in those days, being hard to come by). He was able to do so only because his old employer, the firm of Fenner and Beane (a predecessor of Merrill Lynch), owed him some favors. Templeton made out, of course

The History of Money by Jack Weatherford

Not an investing book in the strictest sense, but a very fun and engaging history of man’s most important invention—as Gertrude Stein said, “The thing that differentiates man from animals is money.” It is cultural life-blood…”and it is from the Latin word currere, meaning “to run” or “to flow,” that the modern word currency is derived, along with other, related words such as current and courier.”

As Weatherford puts it,

Humans have found many ways to bring order to the phenomenological flow of existence, and money is one of the most important. Money is strictly a human invention in that it is itself a metaphor; it stands for something else. It allows humans to structure life in incredibly complex ways that were not available to them before the invention of money. This metaphorical quality gives it a focal role in the organization of meaning in life. Money represents an infinitely expandable way of structuring value and social relationships—personal, political, and religious as well as commercial and economic.

I highlighted more than 100 passages from this book.

The Tao Jones Averages: A Guide to Whole-Brained Investing by Bennett W. Goodspeed

Written decades ago, this was a fun read. Kind of like investing escapism. Some quick hits:

We are at war between consciousness and nature, between the desire for permanence and the fact of flux. It is ourself against ourselves. —ALAN WATTS, The Wisdom of Insecurity

Investing, however, remained more or less an art until 1963, when Donaldson, Lufkin, and Jenrette published the first “scientific” research report.

The World’s Smartest Man finds himself together with the president of the United States, a priest, and a hippie in a plane doomed to crash. On board are only three parachutes, which prompts the president to take one immediately and jump, with the declaration that he owes it to the American people to survive. The World’s Smartest Man next steps forth, claims that his life is an irreplaceable asset to humanity, and exits. The priest looks at the hippie and says: “I have lived my life and now it is in God’s hands; you take the last parachute.” The hippie replies: “No sweat, Padre, we’re both safe; the World’s Smartest Man jumped out with my knapsack!” Judging from the reactions I’ve received to this story, I’d say that people seem to find it entirely plausible that the “world’s smartest man” could be so dumb. Such a paradox is not only curious, but may have many implications for stock market investors. Don’t we all know people who are intellectually brilliant, but who lack common sense?

Don’t Count on It!: Reflections on Investment Illusions, Capitalism, “Mutual” Funds, Indexing, Entrepreneurship, Idealism, and Heroes by John C. Bogle

You may have read Bogle’s “little book,” but this is much better. This book, more than any other, made me realize the importance of what Bogle calls “the tyranny of compounding costs.” I obviously disagree with him that indexing is the best investing solution, but I agree that cost is one of the few “knowns” in investing, and managing them lower is one of the best way to produce superior results. I don’t talk much about costs (fees, trading, taxes) on this site because they are boring topics. But lower is obviously better. Great book from the founder of one of the most impressive investment companies in the world.

Expected Returns: An Investor’s Guide to Harvesting Market Rewards by Antti Ilmanen

A very good academic survey of market anomalies.

One study sorts firms on their 5-year growth rates and finds that ending valuations (P/B) are clearly higher for high-growth firms but beginning valuations display, if anything, the opposite pattern. Valuations appear to respond to the realized growth rate instead of anticipating it. Another study finds that the market is able to identify firms with a future growth edge but it overprices this advantage by a factor of 2.

More More Than You Know: Finding Financial Wisdom in Unconventional Places (Updated and Expanded) (Columbia Business School Publishing) by Michael J. Mauboussin

I am pushing the limits of under-the-radar here because many of you will no doubt have read a lot of Mauboussin’s writing. This was my favorite of his books. It will make you want to go out and investigate the market in new ways.

MONEY Master the Game: 7 Simple Steps to Financial Freedom by Tony Robbins

Just kidding

July 17, 2015

High Conviction Buybacks

Large U.S. companies spent nearly half a trillion dollars on net buybacks (cash spent on buybacks less cash raised through issuance) during the 12 months ending 6/30/2015. That’s almost as much as the buyback peak in 2007, which didn’t turn out too well. Scary! But hold on.

Something that gets lost beneath this broader trend is the level of conviction that the companies repurchasing shares have in their own share price. I define conviction as the percentage of shares repurchased by any company over the prior year. Looking at the percentage reduction in shares (heretofore “buyback yield”) is more useful than just looking at raw dollars.

After all, if Apple ($740B market cap) spends $1B on repurchases, its much different than if Marathon Petroleum ($30B market cap) spends $1B on buybacks. Arguably, that billion spent by Marathon would represent a higher conviction from Marathon’s executives in their own share price. They would be making a much bigger bet.

So what if we broke down all the buybacks into three groups by level of conviction. The low conviction group has repurchased between 0 and 5% of their shares in the past year. The higher and highest conviction groups have repurchases between 5-10% and more than 10% of their shares, respectively. When you add up the totals, you see that most of the raw dollars being spent on buybacks come from the low conviction group. Today, the cash spent on buybacks by the low conviction firms is about 70% of the total amount spent. That is very close to the long term average of 67%.

Let’s go one level further down.

Buying back shares at cheap prices is probably a good idea, especially if the company in question has no other promising potential uses of its capital. Conversely, buying back shares at expensive prices is probably a dumb idea. Buffett said something to this effect once, so it must be true.

It turns out that higher conviction buyback programs are conducted at cheaper relative prices, on average. I evaluate relative prices using an overall valuation percentile, which is just a relative ranking for each stock versus all large U.S. stocks (so the average score is always 50). The percentile is based on four value factors: EBITDA/EV, P/E, P/Sales, and Free Cash Flow/EV.

Here is a time series back to 1987. I’ve also included share issuers here. You can see that on average firms issue shares at higher relative prices.

More interesting, while low conviction buyback companies buyback shares a little cheaper than the market on average (45th percentile or so across this sample), the higher conviction programs (5+% buybacks) tend to repurchases at much cheaper prices (33rd percentile or so).

Finally, the high conviction companies have gone on to ourperform the average large stock by about 3.3% in the subsequent year, while the low conviction firms haven’t really delivered much excess return at all (just 0.5%, on average).

So, buybacks are popular once again, but most of the cash being spent is being spent by firms repurchasing a smaller percent of their total shares. A much smaller chunk is being spent by firms that are repurchasing a ton of their total shares, sometimes more than 10%. Historically, these higher conviction firms have gone on to deliver pretty impressive excess returns. You can read more here.

July 14, 2015

Biggest Investing Influences

PO: David Dreman, for his sharp insight into the power of contrarian investment strategies. Joseph Campbell, whose writing on mythology contains countless lessons for would be investing heroes. Daniel Khaneman and his various research partners, whose exploration of psychology gives me the comfort that our approach will continue to work in the future—because human nature doesn’t change. Jiddu Krishnamurti who taught me the value of investigating for oneself and never simply taking someone else’s word for it. Michael Mauboussin for his countless insightful papers. James Montier for the same reason. Philip Tetlock for curing me of any desire to forecast the future. Nassim Nicholos Taleb, Arthur Koestler, and Edward de Bono for building frameworks to help me think differently—although Taleb would probably not like my portfolio with its lack of disaster insurance. The sage authors of the Upanishads, for helping me stay calm. So many others! James O’Shaughnessy for too many reasons to list.

July 13, 2015

Bullet-Proof Book Recommendations

Every month for the past 16 months, I’ve emailed a group a list of 4-6 book suggestions. Last November, about 1,000 people were on the list, and today we are up to 4,000 and growing fast. I get a ton of feedback on the books I suggest along with dozens of recommendations for other books every week; please keep it coming!

Based on feedback, here are the 5 books that have been the most popular since the beginning of this book club, along with the write up that I originally sent. You can sign up for future recommendations here. I hope you enjoy them!

***

Shadow Divers: The True Adventure of Two Americans Who Risked Everything to Solve One of the Last Mysteries of World War II by Robert Kurson

This book has nothing to do with investing; I include more as a riveting summer read. Two divers discover a U-Boat sunk off of the New Jersey coast which cannot be identified, and then go to amazing lengths to explore and ultimately identify the boat. I could not put this book down. Kurson is a gifted storyteller. One good lesson for investors is to never trust official documents or data. We tend to believe that data is fact, but it is created/reported by fallible people. If a particular datum matters to you, you should always double check for accuracy. Data gets fudged all the time.

Letters of Note: An Eclectic Collection of Correspondence Deserving of a Wider A by Shaun Usher

One of the most enjoyable Christmas presents I’ve ever received. From Hunter S. Thompson’s brilliant life advice, to the never-used speech written in case of an Apollo 11 disaster, to the description of Aldous Huxley’s death (and final LSD trip), this book was full of surprises.

I am always on the lookout for market analogies in non-market books, and this quote from E.B. White struck me. Replace “weather” with “markets” and you’ve got a shrewd observation!

Sailors have an expression about the weather: they say, the weather is a great bluffer. I guess the same is true of our human society—things can look dark, then a break shows in the clouds, and all is changed, sometimes rather suddenly.

Two other passages that really froze me, one terrifying and one eerily wonderful. The first is a letter from Jack the Ripper to a police sergeant Lusk:

From hell

Mr Lusk, Sor I send you half the Kidne I took from one women prasarved it for you tother piece I fried and ate it was very nise. I may send you the bloody knif that took it out if you only wate a whil longer

signed

Catch me when you can Mishter Lusk

The second is Aldous Huxley’s wife describing his death:

He was very quiet now; he was very quiet and his legs were getting colder; higher and higher I could see purple areas of cyanosis. Then I began to talk to him, saying, “Light and free.” Some of these things I told him at night in these last few weeks before he would go to sleep, and now I said it more convincingly, more intensely—“go, go, let go, darling; forward and up. You are going forward and up; you are going, willingly and consciously, and you are doing this beautifully; you are doing this so beautifully—you are going towards the light; you are going towards a greater love; you are going forward and up. It is so easy; it is so beautiful. You are doing it so beautifully, so easily. Light and free. Forward and up. You are going towards Maria’s love with my love. You are going towards a greater love than you have ever known. You are going towards the best, the greatest love, and it is easy, it is so easy, and you are doing it so beautifully.

This is a brilliant book. Just buy it.

The Prize by Daniel Yergin

This might be the best book I’ve ever read. It is long, it is meandering, and it could probably have been 200 pages shorter. Still, it is full of more interesting stories, facts, and history than any book I can recall. Reading the history of the world since 1859 through a lens of oil and gas is just riveting stuff. I read this book because oil & gas investors told me it was their bible. I agree with their assessment, but I think just about anyone would enjoy it. Special extra tip: also read the first part of Yergin’s other book The Quest which fills in the missing history between the Gulf War and 2012.

A Few Lessons from Sherlock Holmes by Peter Bevelin

I wrote a post about how much I loved this book, so check that out here. (How Sherlock Holmes Can Make You a Better Investor)

The Fish That Ate the Whale: The Life and Times of America’s Banana King by Rich Cohen

I wrote an article called “Lessons from Warren Buffett and the Banana Man” which highlights some of my favorite sections from this incredible book. It’s the most fun book that I’ve read in a while.

Zemurray was an immigrant with odds stacked against him, but he won through hard work, cunning, determination and, at times, questionable moral fiber. Though Zemurray started small—selling individual bananas (called “ripes”) that had been discarded by the major fruit companies—he was soon running a fruit empire, almost single-handedly overthrowing Central American governments, and playing a large influence with the CIA.

It was, in fact, hard to distinguish United Fruit from the CIA in those years. The organizations shared personnel as well as equipment and intelligence. Throughout the Guatemala affair, the CIA used United Fruit ships to smuggle money, men, and guns. When the CIA’s funding fell short of its budget, U.F. made up the difference.

It is hard not to love this book.

July 6, 2015

Stolen Prose

Its summer, I don’t write about topics like Grexit, and I am deep into several research projects, so in the meantime I thought I’d post something entirely different, that just might help you find your next book.

The following is an arrangement of sentences and passages that I wish I’d written, pieced together into a narrative on life, death, spirituality and connection. They come from books that I love, written by authors that I revere. Hopefully certain passages will lead you to a new book to put on your list. All books are listed at the end of the post. The quotes are almost entirely direct, with a few small adjustments indicated by brackets.

Who are we—mites in a moment’s mist—that we should understand the universe? The universe is one vast, restless, ceaseless becoming[1]. Simply knowing there is something unknown beyond [our] reach makes [us] acutely restless. [We] have to see what lies outside – if only, as Mallory said of Everest, “because it’s there.” This is true of adventurers of every kind, but especially of those who seek to explore not mountains or jungles but consciousness itself: whose real drive, we might say, is not so much to know the unknown as to know the knower[2].

I’m not really having an existential crisis, if that’s what you’re worried about. No doubt you still feel pretty much in control of your brain, in charge, and calling all the shots. You will still feel that someone, you, is in there making the decisions and pulling the levers. This is the homuncular problem we can’t seem to shake: The idea that a person, a little man, a spirit, someone is in charge. Even those of us who know all the data, who know that it has got to work some other way, we still have this overwhelming sense of being at the controls[3]. For all intents and purposes, a conductor is now leading the orchestra, although the performance has created the conductor—the self—not the other way around. The conductor is cobbled together by feelings and by a narrative brain device, although this fact does not make the conductor any less real. The conductor undeniably exists in our minds, and nothing is gained by dismissing it as an illusion[4].

Nothing places the question “Who am I?” in such stark relief as the fact of death. What dies? What is left? Are we here merely to be torn away from everyone, and everyone from us? And what, if anything, can we do about death – now, while we are still alive? Most social life seems a conspiracy to discourage us from thinking of these questions. But there is a rare type for whom death is present every moment, putting his grim question mark to every aspect of life, and that person cannot rest without some answers[5].

Death: the ultimate frontier[6]. “The quick chaotic bundling of a man into eternity,” as Melville called it; the last impossible phase shift from being a person to being nothing at all[7]. Even with my lifelong meditation on death, my existence had still seemed something permanent and stable on the planet Earth—something dependable, like igneous rock…Atheism seemed like a pretty cruel thing to do to myself. I begged my brain to reconsider. I thought: Won’t I survive somewhere, in some form? Can I believe it? Please? Pretty please can I believe in the everlasting soul? In heaven or angels or paradise with sixteen beautiful virgins waiting for me? Pretty please can I believe that? Look, I don’t even need the sixteen beautiful virgins. There could be just one woman, old and ugly, and she doesn’t even have to be a virgin, she could be the town bike of the ever-after. In fact, there could be no women at all, and it doesn’t have to be paradise, it could be a wasteland—hell, it could even be hell, because while suffering the torments of a lake of fire, at least I’d be around to yell “Ouch!” Could I believe in that, please[8]? Dreams are real as long as they last. Can we say more of life?[9]

The word “religion” comes from the Latin for “binding together,” to connect that which has been sundered apart. It’s a very interesting concept. And in this sense of seeking the deepest interrelations among things that superficially appear to be sundered[10]. [But] this feeling of being lonely and very temporary visitors in the universe is in flat contradiction to everything known about man (and all other living organisms) in the sciences. We do not “come into” this world; we come out of it, as leaves from a tree. As the ocean “waves,” the universe “peoples.” Every individual is an expression of the whole realm of nature, a unique action of the total universe. This fact is rarely, if ever, experienced by most individuals. Even those who know it to be true in theory do not sense or feel it, but continue to be aware of themselves as isolated “egos” inside bags of skin[11]. It’s as if we live at the edge of a waterfall, with each moment rushing at us—experienced only and always now at the lip—and then zip, it’s over the edge and gone. But the brain is forever clutching at what has just surged by[12].

[The] wider field of consciousness is our native land. We are not cabin-dwellers, born to a life cramped and confined; we are meant to explore, to seek, to push the limits of our potential as human beings. The world of the senses is just a base camp: we are meant to be as much at home in consciousness as in the world of physical reality. This is a message that thrills men and women in every age and culture[13]. I use one central metaphor for conscious experience: the “Ego Tunnel.” Conscious experience is like a tunnel. Modern neuroscience has demonstrated that the content of our conscious experience is not only an internal construct but also an extremely selective way of representing information. This is why it is a tunnel: What we see and hear, or what we feel and smell and taste, is only a small fraction of what actually exists out there. Our conscious model of reality is a low-dimensional projection of the inconceivably richer physical reality surrounding and sustaining us. Our sensory organs are limited: They evolved for reasons of survival, not for depicting the enormous wealth and richness of reality in all its unfathomable depth. Therefore, the ongoing process of conscious experience is not so much an image of reality as a tunnel through reality[14].

The sole means now for the saving of the beings of the planet Earth would be to implant again into their presences a new organ … of such properties that every one of these unfortunates during the process of existence should constantly sense and be cognizant of the inevitability of his own death as well as the death of everyone upon whom his eyes or attention rests. Only such a sensation and such a cognizance can now destroy the egoism completely crystallized in them. As we now regard death this reads like a prescription for a nightmare. But the constant awareness of death shows the world to be as flowing and diaphanous as the filmy patterns of blue smoke in the air[15]. May we light the fire of Nachiketa That burns out the ego and enables us to pass from fearful fragmentation to fearless fullness in the changeless whole[16]. Most of our troubles stem from attachment to things that we mistakenly see as permanent[17]. Love and compassion are what we must strive to cultivate in ourselves, extending their present boundaries all the way to limitlessness[18]. Damyata datta dayadhvam, “Be self-controlled, give, be compassionate.[19].” The joy of the spirit ever abides, but not what seems pleasant to the senses. Both these, differing in their purpose, prompt us to action. All is well for those who choose the joy of the spirit, but they miss the goal of life who prefer the pleasant. Perennial joy or passing pleasure? This is the choice one is to make always. Those who are wise recognize this, but not the ignorant[20]. Those who see all creatures in themselves and themselves in all creatures know no fear. Those who see all creatures in themselves and themselves in all creatures know no grief. How can the multiplicity of life delude the one who sees its unity[21]?

The faculty of voluntarily bringing back a wandering attention over and over again is the very root of judgment, character and will. An education which should include this faculty would be the education par excellence[22]. Ancient Pali texts liken meditation to the process of taming a wild elephant. The procedure in those days was to tie a newly captured animal to a post with a good strong rope. When you do this, the elephant is not happy. He screams and tramples and pulls against the rope for days. Finally it sinks through his skull that he can’t get away, and he settles down. At this point you can begin to feed him and to handle him with some measure of safety. Eventually you can dispense with the rope and post altogether and train your elephant for various tasks. Now you’ve got a tamed elephant that can be put to useful work. In this analogy the wild elephant is your wildly active mind, the rope is mindfulness, and the post is your object of meditation, your breathing. The tamed elephant who emerges from this process is a well-trained, concentrated mind that can then be used for the exceedingly tough job of piercing the layers of illusion that obscure reality. Meditation tames the mind[23].

Above the senses is the mind, above the mind is the intellect, above that Is the ego, and above the ego is the unmanifested Cause. And beyond is Brahman [the Self], omnipresent, attributeless. Beyond the reach of the senses is [the Self], but not beyond the reach of a mind stilled through the practice of deep meditation. Beyond the reach of words and works is he, but not beyond the reach of a pure heart freed from the sway of the senses[24]. Those who realize the Self enter into the peace that brings complete self-control and perfect patience. They see themselves in everyone and everyone in themselves. Evil cannot overcome them because they overcome all evil. Sin cannot consume them because they consume all sin. Free from evil, free from sin and doubt[25]. When all desires that surge in the heart are renounced, the mortal becomes immortal. When all the knots that strangle the heart are loosened, the mortal becomes immortal[26]. As rivers lose their private name and form when they reach the sea, so that people speak of the sea alone, so [the separate self] disappears when the Self is realized. Then there is no more name and form for us, and we attain immortality[27].

As a heavily laden cart creaks as it moves along, the body groans under its burden when a person is about to die. When the body grows weak through old age or illness, the Self separates himself as a mango or fig or banyan fruit frees itself from the stalk, and returns the way he came to begin another life[28]. Thou hast existed as a part, thou shalt disappear in that which produced thee. . . . This, too, nature wills. . . . Pass, then, through this little space of time comfortably to nature, and end thy journey in content, just as an olive falls when it is ripe, blessing the nature that produced it, and thanking the tree on which it grew[29]. As a lump of salt thrown in water dissolves and cannot be taken out again, though wherever we taste the water it is salty, even so, beloved, the separate self dissolves in the sea of pure consciousness, infinite and immortal. Separateness arises from identifying the Self with the body, which is made up of the elements; when this physical identification dissolves, there can be no more separate self.[30]

The Self in man and in the sun are one. Those who understand this see through the world and go beyond the various sheaths of being to realize the unity of life. Those who realize that all life is one are at home everywhere and see themselves in all beings. They sing in wonder: “I am the food of life, I am, I am; I eat the food of life, I eat, I eat. I link food and water, I link, I link. I am the first-born in the universe; Older than the gods, I am immortal. Who shares food with the hungry protects me; who shares not with them is consumed by me. I am this world and I consume this world. They who understand this understand life.” This is the Upanishad, the secret teaching[31].

Books:

[1] Heroes of History by Will Durant

[2] The Upanishads (Classics of Indian Antiquity) by Eknath Easwaran

[3] Who’s in Charge?: Free Will and the Science of the Brain by Michael S. Gazzaniga

[4] Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain by Antonio Damasio

[5] The Upanishads (Classics of Indian Antiquity) by Eknath Easwaran

[6] Sleeping, Dreaming and Dying by the Dalai Lama

[7] WAR by Sebastian Junger

[8] A Fraction of the Whole by Steve Toltz)

[9] Havelock Ellis quoted in The Upanishads (Classics of Indian Antiquity) by Eknath Easwaran

[10] The Varieties of Scientific Experience: A Personal View of the Search for God by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan

[11] The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are by Alan Watts

[12] Buddha’s Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love, and Wisdom by Rick Hanson

[13] The Upanishads (Classics of Indian Antiquity) by Eknath Easwaran

[14] The Ego Tunnel by Thomas Metzinger

[15] The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are by Alan Watts

[16] The Upanishads (Classics of Indian Antiquity) by Eknath Easwaran

[17] How to See Yourself As You Really Are by the Dalai Lama

[18] How to See Yourself As You Really Are by the Dalai Lama

[19] The Upanishads (Classics of Indian Antiquity) by Eknath Easwaran

[20] The Upanishads (Classics of Indian Antiquity) by Eknath Easwaran

[21] The Upanishads (Classics of Indian Antiquity) by Eknath Easwaran

[22] Principles of Psychology by William James

[23] Mindfulness in Plain English: 20th Anniversary Edition by Bhante Gunaratana

[24] The Upanishads (Classics of Indian Antiquity) by Eknath Easwaran

[25] The Upanishads (Classics of Indian Antiquity) by Eknath Easwaran

[26] The Upanishads (Classics of Indian Antiquity) by Eknath Easwaran

[27] The Upanishads (Classics of Indian Antiquity) by Eknath Easwaran

[28] The Upanishads (Classics of Indian Antiquity) by Eknath Easwaran

[29] Heroes of History by Will Durant

[30] The Upanishads (Classics of Indian Antiquity) by Eknath Easwaran

[31] The Upanishads (Classics of Indian Antiquity) by Eknath Easwaran

June 27, 2015

Creating Unique Investment Strategies

I took a car service home from Newark airport at 1 a.m. this week after a tiring but fun west-coast trip. I’d just met with 15 very impressive teams—advisors, RIAs, etc—to discuss markets and investment strategies. It struck me that it must be very difficult for advisors–who are constantly bombarded by portfolio managers like me representing investment strategies–to find managers and strategies that are truly unique and therefore worth their time to consider.

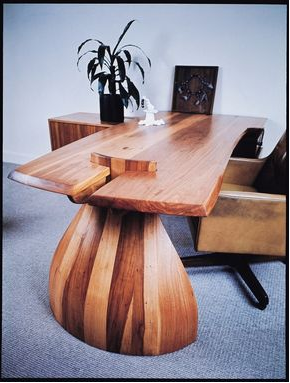

I was thinking about this challenge on the way home, and because I was still on west coast time, I had energy to talk to my driver David and thank god I did. It turns out that he had only been driving for 2 years, and only because a double hip replacement had ended his several decades long career as a master furniture craftsman and woodworker. Here is a desk he made.

His lifelong passion has been creativity. I’ve read a lot and written a bit on this topic, and think it is crucial for active management and for life in general. David was clearly an expert, someone who hadn’t just read about creativity, but lived it.

He outlined what he felt were the essential aspects of a creative life. Creativity is play, he told me. Play is like dancing. The best play happens when you don’t give a damn about convention, or about what other people think. Play is most delightful, he said, when it combines random different elements. When you tinker for fun, surprising results ensue. The scientific method, he said, is bullshit. Most major discoveries are accidents: the results of tinkering and play. Mixing things which don’t seem to make sense and which may make you look or feel silly in the short-run. Most people, David said, operate within a conventional set of rules or norms, the pre-established.

“The mind is the result of the known; it is the result of the past, which is the accumulation of time; and is it possible for such a mind to be free from the known without effort so that it can discover something original?”

What excites me most is finding something new. An original insight, a creative combination, and unexpected result. I am always chasing these moments. This is very hard to do in the world of finance and asset management, where themes, strategies and opinions tend to coalesce. The hunt for alpha is in many ways the hunt to free oneself from the markets conditioning. Perhaps true alpha requires redefining many taken-for-granted market concepts.

In investing, you want to do something that no one else is doing (or very few others are doing). But not just because there is no one else is doing it, but also because it makes sense to do. Value has worked historically because it is a clean way to buy stuff that others dislike. The best value stocks have a few other attributes as well (as Seth Klarman put it, you want to have a contrarian streak and a calculator).

But now everyone likes value. The “value tilts” which are introduced into portfolios in smart beta or similar strategies aren’t the real McCoy. Value should hurt!! It doesn’t hurt to buy a fundamental index. If it doesn’t hurt, it should at least scare you. Scare you because the stocks look terrible, because they’ve done badly, or because buying a particular basket of stocks introduces the career risk that we must accept if we are to own unique portfolios. Contrarian value strikes me as creative. Value tilts may have been once, but do not seem to be anymore.

Obstacles

Robert Shiller said something which nails this point exactly: “[I]f you swim with the current, you will be thinking the same things as everyone else. You have to recognize that your own thoughts are not your own thoughts. They kind of filtered and percolated in from other people. It all seems like my own common sense, but it’s just what everybody is saying now.”

That is a scary, powerful, and often accurate notion: your thoughts are not your thoughts. How to undo this mess? Jiddu Krishnamurti would say that to do so you must free your mind from all conditioning.

“When the mind is free from all conditioning, then you will find that there comes the creativity of reality, of God, or what you will, and it is only such a mind, a mind which is constantly experiencing this creativity, that can bring about a different outlook, different values, a different world.”

[You] must have immense patience to find out what is true. Most of us are impatient to get on, to find a result, to achieve a success, a goal, a certain state of happiness, or to experience something to which the mind can cling. But what is needed, I think, is a patience and a perseverance to seek without an end.

Seeking without end, that’s just play! A true understanding of self will also be required, otherwise you’ll be more likely to cave from outside pressures.

And so it is important to understand oneself, is it not? Self-knowledge is the beginning of wisdom. Self-knowledge is not according to some psychologist, book, or philosopher but it is to know oneself as one is from moment to moment. Do you understand? To know oneself is to observe what one thinks, how one feels, not just superficially, but to be deeply aware of what is without condemnation, without judgment, without evaluation or comparison. Try it and you will see how extraordinarily difficult it is for a mind that has been trained for centuries to compare, to condemn, to judge, to evaluate, to stop that whole process and simply to observe what is; but unless this takes place, not only at the superficial level, but right through the whole content of consciousness, there can be no delving into the profundity of the mind…creativity is something that comes into being only when the mind is in a state of no effort.

I often hear people say that they are influenced by their “priors,” which is a fancy word for thought-habits. I am guilty, too. I tend to seek out data which further supports my core investment believes (in factors like value, momentum, capital allocation, etc).

The best way to shed priors? I’m still trying to figure that out. I have found that conditioning is stripped away on a walk in the woods, or in the shower, or in the middle of the night. In certain moments like these, everything sometimes feels like a farce, a hoax, and with everything so exposed we can re-evaluate things on a blank slate.

David would say, just play! Operate outside established rules.

What might that mean in investing? For quants, it might mean that you forget about the “fundamental law of asset management” proposed by Grinold and Kahn. Perhaps high information ratios are not sacrosanct. Perhaps a more differentiated, concentrated application of investing factors is better. I wrote recently about buybacks as a factor: it turns out you don’t want a broad exposure (say several hundred stocks) to that factor but instead to a fairly concentrated subgroup: companies who are repurchasing significant amounts of their shares, not just a few percent.

I read a book recently called Waking Up to the Dark that is a little wonky, but is also compelling. It talks about waking up at odd hours. Meditating. Taking walks in the dark.

So I took a long walk in the dark the other night which 1) made my wife (and maybe some of you) think I was a weirdo and 2) created an incredible mental clarity and about five new ideas. I had never just walked in the pitch dark before. I had never considered it. A few years ago I would have said it was dumb. But it was was pretty great. If something appears stupid, or weird, or silly, it may mean that you are on to something.

***

At the end of my drive home, David said he has one day off a week and would love if I came by his house to talk about books and eat and drink wine. No surprise he is an expert cook. He proposed salad with what he calls “Greek Goddess” dressing, his playful take on green goddess dressing that uses tzatziki, along with some intricate sounding smoked ribs, made in a smoker he built, and a side of spicy coleslaw with sweet raisins. And some Malbec. How friggin good does that sound?

It is rare to meet someone whose life is driven by creative play, but each time I do I am reminded how important it is to keep an open mind, try different things, and try to deliver high quality results that only you or your firm could deliver in the first place. Creativity is the uninhibited expression of self. Thank you to David for reminding me of this truth.

Note: if any of this strikes you as worth thinking about more, I suggest you watch the third episode of Netflix’s fan-friggin-tastic new show “Chef’s Table.” The episode profiles chef Francis Mallmann who may embody all this more than anyone I’ve come across. It is a jarring and amazing hour of television.

For the quanty folks, this strategy may never look appealing because the IR will be lower due to lower breadth, but doesn’t it make a lot more sense that the high conviction buyback programs, say 10% plus, would be a more effective signal than low conviction ones?

June 26, 2015

Return on Equity Explored

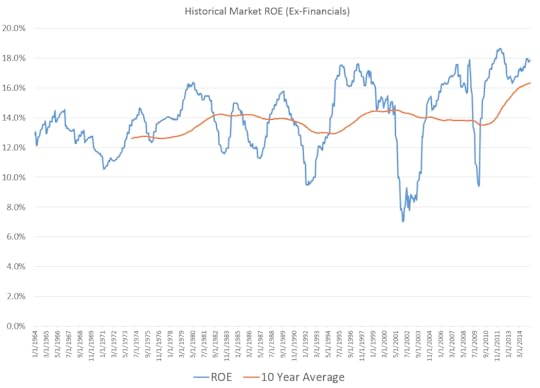

Non-financial firms are earning an impressive return on their collective equity value. As of April 30th, the U.S. markets return on equity was nearly 18%, well above the long term average of 14% for non-financial firms. Obviously, corporations like earning impressive returns on their equity. So what is driving today’s elevated rates, and what trends have mattered most for the trends in ROE? Here is the story, in chart form.

First up, the market’s overall ROE, along with a smoother 10-year average. You can see its been pretty consistent, with a notable bump recently.

The markets ROE is a function of three key ingredients: net profit margin, leverage (more leverage juices up ROE), and asset turnover (i.e. how many dollars of sales are companies producing for each dollar of assets–how productive are their assets). Here are the trends in those three factors.

As Warren Buffett put it in a classic 1977 Fortune article,

To raise that return on equity, corporations would need at least one of the following: (1) an increase in turnover, i.e., in the ratio between sales and total assets employed in the business; (2) cheaper leverage; (3) more leverage; (4) lower income taxes; (5) wider operating margins on sales.

The chart above shows that (1) asset turnover has been falling, and (3) financial leverage has been falling. So these two components are working against ROE.

So the story must be in net margin–and to reach net margin we simply combine numbers (2), (4), and (5) from Buffett’s simple explanation above. These are, respectively:

The rate of interest being paid (known as interest burden, this is the percent of operating earnings retained after paying interest on debt)

The effective tax rate (known as tax burden, this is the percent of pre-tax profits that remain after paying taxes)

And the operating margin

Multiply all three together, and you have net margin. It is simple: pay a lower tax rate, spend less on interest, and earn a higher margin on sales and margins go up. Here are the more recent trends (1980 on) in these components:

You can see that interest and tax measures are near highs, which companies like because it means they are losing less of their profits to interest and tax. This flows through to higher net margins, and therefore to higher ROEs. Operating margins are also strong, sitting about 1% lower than all time highs.

What do you think are the trends most likely to change or reverse?

June 24, 2015

Some Poetry

Sometimes, I find good poetry superior to everything else. Tonight is one such night. These are T.S. Eliot, except where otherwise noted.

In my beginning is my end.

The inner freedom from the practical desire,

The release from action and suffering, release from the inner

And the outer compulsion, yet surrounded

By a grace of sense, a white light still and moving,

Erhebung [German for elevating] without motion, concentration

Without elimination, both a new world

And the old made explicit, understood

In the completion of its partial ecstasy,

The resolution of its partial horror.

Yet the enchainment of past and future

Woven in the weakness of the changing body,

Protects mankind from heaven and damnation

Which flesh cannot endure.

The only wisdom we can hope to acquire Is the wisdom of humility: humility is endless.

And what there is to conquer

By strength and submission, has already been discovered

Once or twice, or several times, by men whom one cannot hope

To emulate—but there is no competition—

There is only the fight to recover what has been lost

And found and lost again and again: and now, under conditions

That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss.

For us, there is only the trying.

The rest is not our business.

You’ve got to walk / that lonesome valley / Walk it yourself / You’ve gotta gotta go / By yourself / Ain’t nobody else / gonna go there for you / Yea, you’ve gotta go there by yourself.—TRADITIONAL GOSPEL SONG

Old men ought to be explorers

Here and there does not matter

We must be still and still moving

Into another intensity

For a further union, a deeper communion

Through the dark cold and the empty desolation,

The wave cry, the wind cry, the vast waters

Of the petrel and the porpoise.

In my end is my beginning.

…

This is how a human being can change. There is a worm addicted to eating grape leaves. Suddenly, he wakes up, call it grace, whatever, something wakes him, and he is no longer a worm. He is the entire vineyard, and the orchard too, the fruit, the trunks, a growing wisdom and joy that does not need to devour. – Rumi

Have a great night.