Patrick O'Shaughnessy's Blog, page 26

December 7, 2015

The Investor’s Podcast

The problem with the financial television shows is that it is very hard to have a good investing discussion in 5 minutes. These shows still have the reach, of course, but the short nature of the segments means you have to focus more on sound bites than truly helpful advice/information. I think of going on TV as a piece of bait that hopefully gets a few people interested in what one is doing.

Podcasts, in sharp contrast, let you wander down the more interesting side streets. This interview with the guys at The Investor’s Podcast is the most detailed podcast I have done, and certainly one of the most fun. Thank you to Preston, Stig and Toby for having me. Their caricature game is on point. Check it out for in depth discussions of value vs. growth, buybacks, the dangers of back-testing, and the importance of discipline.

Podcasts now rival books. Here are a few of my other favorites, discovered this year:

Exponent – Run by Ben Thompson who writes at Stratechery, another great resource.

Masters in Business – Everyone may already be familiar with Barry’s show, but its worth highlighting. His guest list is peerless.

Hardcore History – Check out the episode called “The American Peril.”

The Time Ferris Show – Another heavy hitter who gets great guests and is very good at getting them to talk about interesting aspects of their lives.

December 1, 2015

The Persistence of Growth

It is unlikely that the fastest growing companies from the past five years—think Tesla, Apple, and Under Armor which have grown sales 32x, 4x, and 4x respectively since 2010—will continue to be the fastest growing companies over the next five years.

Some high growth stocks will continue their torrent growth, but future growth rates have always been less impressive than past growth rates for the fastest growing companies.

The relationship between growth and valuation has been exploitable through history. A stock’s valuation is a collectively derived expectation for future growth. A high (expensive) price-to-sales means the market expects sales to grow a lot. A low (cheap) price-to-sales means the market expects sales to grow a lot less. We know that these expectations have often turned out to be overdone on both sides. For growth stocks, expectations have been too lofty (thus their under performance long term), and vice versa for value.

Since the 1960’s, companies trading at the most expensive price-to-sales multiples have had higher trailing sales growth, on average. In this first chart, we group all stocks into ten separate groups by their price-to-sales ratio (average price-to-sales for each group is shown with the blue line on the right scale), and then chart their average trailing growth rates (green bars, left scale). The most expensive stocks (trading at price-to-sales of 4x or so) grew sales by an average of 28% over the previous five years, and the cheapest (trading at 0.16x) grew sales by an average of 13%.

Reversion

Next, we sort by trailing sales growth instead of valuation. Now we can look at both the trailing and future growth rates for the highest and lowest growth companies.

The universe of stocks under consideration here is all U.S. companies between 1968 and 2010 (because we need 10 years of data, five trailing years and five future years) with market caps of at least $200MM. Companies are grouped into 10 deciles based on their trailing 5 years sales growth. The universe and time horizon are a bit arbitrary. Results look similar using large stocks only instead of all stocks, or using a 3-year horizon instead of 5-year.

You can see that on average, the highest growth firms have grown earnings at an impressive 46% per year clip (or, 562% cumulatively over five years). The lowest growth stocks have smaller earnings than five years earlier—their sales fell by -5% per year, -22% cumulatively.

But the forward looking growth numbers look much different. The previously high growth stocks still grow fast, at a rate of roughly 18% per year, but their total growth is much smaller than during the prior five years. The low growth stocks rebound, growing at an average of 12% after their five years of declining sales.

Of course, this is a long term average which various considerably. Here is a time series of the trailing and future 5-year sales growth difference (high growth minus low growth) through time.

Both the long term average and time series charts make this very clear: the growth rate advantage of high growth stocks from the past five years does not persist over the next five years. Growth stocks tend to keep growing, but their relative advantage over low growth narrows considerably. If and when the market prices stocks by extrapolating past trends into the future, there is an opportunity to bet against that misguided extrapolation (long value, short growth).

In markets, fundamentals level out.

Data Stuff

There are a lot potential biases when building tests like this using historical data, so let me be clear about what I required or didn’t for a firm to be in the sample:

Have a sales number on the starting date

I did not require a sales number five years or ten years in the future, so as not to exclude companies that fall out of the data. I effectively set the future sales for such companies to 0 and assume -99% future sales growth for these companies. Not necessarily the perfect handling, but I think better than excluding them altogether.

Trailing and future growth numbers > 100x were eliminated (that is, if a firm’s sales grew by more than 100 times over five years, I kicked them out).

This is all done with sales—instead of earnings or cash flows—because they are always positive and there are weird issues calculating growth rates when numbers flip from negative to positive.

Simply total sales today / total sales five years ago

November 18, 2015

Fun with F.A.N.G.

Growth stocks have killed value stocks lately, led in large part by four stocks. Let’s make the following arbitrary assumptions in order to have fun with the group of stocks know as F.A.N.G. (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and Google).

Let’s assume:

That each company’s market cap grows by 7% per year for the next 10 years (roughly the market’s historical growth rate). 7% for 10 years leads to a doubling of market cap.

That in 10 years, they each trade for 21.9X trailing 12-month earnings, which is the current multiple on the S&P 500

Obviously, none of this will happen, but that shouldn’t stop a little fun.

Here, in the final column, are the annual earnings growth rates that would be required to satisfy our assumptions.

Let’s take Amazon as the best example. It’s trailing 1-year earnings as of 10/31/2015 were $328MM. Its market cap was $293B. So if it doubles in the next ten years, to nearly $600B in market cap, and trades at 21.9x earnings, that means it will have to grow its earnings at 55% PER YEAR for 10 years. That is possible but highly improbable. I looked back to 1973 and found that a small percentage of companies (0.28% of them) did grow earnings at that rate for 10 years (many off of a much smaller base than Amazon).

Michael Mauboussin wrote a great Chapter on what he calls the inside view versus the outside view. I recommend the whole chapter.

In our case, the inside view is trying to explain why Amazon in particular can achieve this amazing growth rate, which would go something like this: Amazon is my favorite company, it is doing things no one else can or has. AWS is amazing, and is a higher margin business. Slight upticks in margin would significantly grow earnings.

The outside view, by contrast, is the historical base rate (percentage chance) of ALL companies hitting that type of growth rate over ten years. Again, a fraction of 1% of companies have been able to achieve this rate.

The inside view is always more seductive, but the outside view is more sobering and usually more useful.

Will Amazon be the next company to grow that fast? Could be. But based on the outside view, the odds are about 9 times worse than hitting a random number in roulette.

October 29, 2015

Metaphors and Mental Models: The Key to Understanding

When I first read the sequence of passages that I quote below, I felt like I had discovered a diamond while exploring a shop of horrors. The passages come from a book by Julian Jaynes, whose controversial (and carefully thought out) theory is that just a few thousand years ago, human beings weren’t conscious like us, but instead did what they were told to do by god-like voices in their heads. The book is an intellectual shop of horrors in a good way, because it makes you think hard about the possibility of the seemingly impossible.

But rather than get into Jaynes’s broader theory, I want to focus on a small section that I think can be useful for how you think about the world, one that I think jives well with Charlie Munger’s “mental models” approach to thinking.

Munger believes in collecting little packets of understanding for how things work, little models of the world. When you collect models from lots of different fields—say psychology, literature, science, math, and so on—you will then be able to recognize lots of interesting connections. Models are reference points of understanding.

Jaynes writes not about models but about metaphors. I think that by collecting what Jaynes calls “metaphiers,” you can position yourself to better understand new things in the future. His explanation is useful for those trying to understand the world, come up with something new, or combine things into creative new patterns (which could be a piece of art of a company). It also has implications for salespeople or for anything trying to convince or explain. Conveying an idea through metaphor is almost always a good idea.

Metaphors and Understanding

Jaynes begins by defining metaphor, which is made up of two components:

the thing to be described, which I shall call the metaphrand, and the thing or relation used to elucidate it, which I shall call the metaphier. A metaphor is always a known metaphier operating on a less known metaphrand.

Yesterday I used two hypothetical basketball teams to describe quirks of value style indexes like the Russell 1000 Value. I did so because the difference between the two teams I made up is much easier to understand than the difference between the investment strategies I was trying to explain. The metaphrands (thing to be explained) were the Russell Value indexes, the metaphier (reference point used to explain) was the odd made up NBA team of the five best centers in the league.

It is through metaphors that language and understanding grow from simple things to more complex things. We start with things we understand, like the body, and our own simple behaviors, and create new language:

The human body is a particularly generative metaphier, creating previously unspeakable distinctions in a throng of areas. The head of an army, table, page, bed, ship, household, or nail, or of steam or water; the face of a clock, cliff, card, or crystal; the eyes of needles, winds, storms, targets, flowers, or potatoes… and so on and on …All of these concrete metaphors increase enormously our powers of perception of the world about us and our understanding of it, and literally create new objects. Indeed, language is an organ of perception, not simply a means of communication.

In early times, language and its referents climbed up from the concrete to the abstract on the steps of metaphors, even, we may say, created the abstract on the bases of metaphors.

We aren’t aware of this slow building up of metaphors through time.

Because in our brief lives we catch so little of the vastnesses of history, we tend too much to think of language as being solid as a dictionary, with a granite-like permanence, rather than as the rampant restless sea of metaphor which it is.

We have a “fixed” view of the world. We think language is fixed, that models of the world are fixed, but they are not. Language and models and understanding are forever changing, and the best way to be at the vanguard of this change is to collect packets of understanding: metahpiers which will be used to understand (and explain) new metaphrands.

what are we really trying to do when we try to understand anything? Like children trying to describe nonsense objects, so in trying to understand a thing we are trying to find a metaphor for that thing. Not just any metaphor, but one with something more familiar and easy to our attention. Understanding a thing is to arrive at a metaphor for that thing by substituting something more familiar to us. And the feeling of familiarity is the feeling of understanding.

A theory is thus a metaphor between a model and data. And understanding in science is the feeling of similarity between complicated data and a familiar model.

This is the same thing as I’ve written about before on the topic of creativity. The creation of something new and interesting results from the combination of “familiar models.”

The “mental model” approach to life suggested by Charlie Munger is a version of this entire thing. Having more “models,” or reference points of understanding, is like casting a wider net when fishing (you see what I did there!!).

Here is Munger (much more here) on the need for models (which are just big metaphiers).

You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience ‑ both vicarious and direct ‑ on this latticework of models. You may have noticed students who just try to remember and pound back what is remembered. Well, they fail in school and in life. You’ve got to hang experience on a latticework of models in your head.

Things aren’t static, they change. Our understanding and communication changes on the basis of new metaphors. We understand new things in reference to some older thing that we already understand. What will we be trying to understand in the future? Who knows? Don’t try to predict the future, but instead collect models and metaphiers so that you’ll recognize opportunity for new combinations, patterns, and ideas when they come. Since I’ve relied on other’s thinking in this post, I may as well close it out with a great quote from Paul Graham.

It seems to me that beliefs about the future are so rarely correct that they usually aren’t worth the extra rigidity they impose, and that the best strategy is simply to be aggressively open-minded. Instead of trying to point yourself in the right direction, admit you have no idea what the right direction is, and try instead to be super sensitive to the winds of change.

END NOTE: for those still interested (Bueller?), here is a continuation that deals more with consciousness. This book tripped me out!

If understanding a thing is arriving at a familiarizing metaphor for it, then we can see that there always will be a difficulty in understanding consciousness. For it should be immediately apparent that there is not and cannot be anything in our immediate experience that is like immediate experience itself.

I realize that my argument here is becoming fairly dense. But before coming out into the clearing, I wish to describe what I shall mean by the term analog. An analog is a model, but a model of a special kind. It is not like a scientific model, whose source may be anything at all and whose purpose is to ad as an hypothesis of explanation or understanding. Instead, an analog is at every point generated by the thing it is an analog of. A map is a good example. It is not a model in the scientific sense, not a hypothetical model like the Bohr atom to explain something unknown. Instead, it is constructed from something well known, if not completely known. Each region of a district of land is allotted a corresponding region on the map, though the materials of land and map are absolutely different and a large proportion of the features of the land have to be left out. And the relation between an analog map and its land is a metaphor. If I point to a location on a map and say, “There is Mont Blanc and from Chamonix we can reach the east face this way,” that is really a shorthand way of saying, “The relations between the point labeled ‘Mont Blanc’ and other points is similar to the actual Mont Blanc and its neighboring regions.”

I think it is apparent now, at least dimly, what is emerging from the debris of the previous chapter. I do not now feel myself proving my thesis to you step by step, so much as arranging in your mind certain notions so that, at the very least, you will not be immediately estranged from the point I am about to make. My procedure here in what I realize is a difficult and overtly diffuse part of this book is to simply state in general terms my conclusion and then clarify what it implies. Subjective conscious mind is an analog of what is called the real world. It is built up with a vocabulary or lexical field whose terms are all metaphors or analogs of behavior in the physical world. Its reality is of the same order as mathematics.

Consider the language we use to describe conscious processes. The most prominent group of words used to describe mental events are visual. We ‘see’ solutions to problems, the best of which may be ‘brilliant’, and the person ‘brighter’ and ‘clearheaded’ as opposed to ‘dull’, ‘fuzzy-minded’, or ‘obscure’ solutions. These words are all metaphors and the mind-space to which they apply is a metaphor of actual space. In it we can ‘approach’ a problem, perhaps from some ‘viewpoint’, and ‘grapple’ with its difficulties, or seize together or ‘com-prehend’ parts of a problem, and so on, using metaphors of behavior to invent things to do in this metaphored mind-space.

Now when we say mind-space is a metaphor of real space, it is the real ‘external’ world that is the metaphier. But if metaphor generates consciousness rather than simply describes it, what is the metaphrand?

Consider the metaphor that the snow blankets the ground. The metaphrand is something about the completeness and even thickness with which the ground is covered by snow. The metaphier is a blanket on a bed. But the pleasing nuances of this metaphor are in the paraphiers of the metaphier, blanket. These are something about warmth, protection, and slumber until some period of awakening. These associations of blanket then automatically become the associations or paraphrands of the original metaphrand, the way the snow covers the ground. And we thus have created by this metaphor the idea of the earth sleeping and protected by the snow cover until its awakening in spring. All this is packed into the simple use of the word ‘blanket’ to pertain to the way snow covers the ground.

The world is organized, highly organized, and the concrete metaphiers that are generating consciousness thus generate consciousness in an organized way. Hence the similarity of consciousness and the physical-behavioral world we are conscious of. And hence the structure of that world is echoed —though with certain differences—in the structure of consciousness.

One last complication before going on. A cardinal property of an analog is that the way it is generated is not the way it is used—obviously. The map-maker and map-user are doing two different things. For the map-maker, the metaphrand is the blank piece of paper on which he operates with the metaphier of the land he knows and has surveyed. But for the map-user, it is just the other way around. The land is unknown; it is the land that is the metaphrand, while the metaphier is the map which he is using, by which he understands the land. And so with consciousness. Consciousness is the metaphrand when it is being generated by the paraphrands of our verbal expressions. But the functioning of consciousness is, as it were, the return journey. Consciousness becomes the metaphier full of our past experience, constantly and selectively operating on such unknowns as future actions, decisions, and partly remembered pasts, on what we are and yet may be. And it is by the generated structure of consciousness that we then understand the world.

October 28, 2015

Benchmark Oddities

Imagine two NBA teams. Team one starts Anthony Davis, Russell Westbrook, Stephen Curry, Kevin Durant, and James Harden. Team two starts Hassan Whiteside, DeMarcus Cousins, Brook Lopez, Marc Gasol, and Nikola Vucevic. Who wins?

The two teams above were determined by a stat called PER (player efficiency rating) with the twist being that while team one is simply the five best players in the league, team two is the five best BIG players (who play the center position). If you think of these as a simple models for building a team, there are two factors: size and player efficiency. In this case, using efficiency alone produces a far better team.

The investing parallel here are style indexes like the Russell 1000 Value or Russell 2000 Growth. Style indexes are very popular, but when you really examine their methodology, they are also rather odd, sort of like team two.

The “strategy” for each style benchmark has two steps. First, determine what stocks are in the index, and second, determine what weight each stock gets. Benchmark constituents (the stocks IN the index) are determined by relative valuation (book-to-price and expected growth), but each stock’s weight is then determined by size (market cap).

The strategy behind these value indexes could be phrased this way: Cheap is good, but big and moderately cheap is better than smaller and really cheap.

For example, Exxon Mobile has a price-to-book of 1.95, but is a huge company so has a weight of 3.3% in the Russell 1000 Value index. Seadrill—a maligned energy stock—has a price to book of 0.28. So it is much “cheaper” than Exxon, but it’s only a $2B company, so its weight in the index is 0.02%, which may as well be zero.

If Exxon went up 40%, it would push the overall index up 1.35% or so. If Seadrill went up 40%, it would push the index up 0.01%. So for the Russell 1000 Value, Exxon is the far more important stock. But if you cared more about value than size, then the weights would be very different. Exxon is the biggest stock, but it’s only in the 50th percentile when sorted by price-to-book instead of by market cap. Seadrill is in the cheapest percentile.

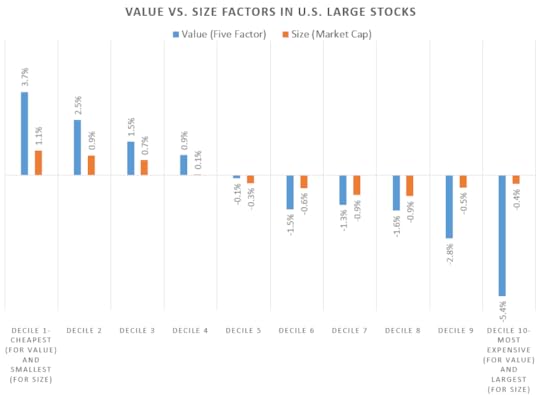

This is odd because the relative merit of one stock over another (and therefore, its weight in your portfolio) is far better determined by its cheapness than by its size. Here is a comparison of the size and value factors in the U.S. Large Cap market, since 1963. These are the historical excess returns for factor deciles, which are rebalanced like the style indexes are, on an annual basis.

Relative valuation (measured here by a five factor model using sales, earnings, free cash flow, EBITDA, and total yield) has been far more predictive than relative size, but the index is weighted in the opposite way.

For people running money, building a rules-based index/strategy which weights stocks based on their size is a wonderful business idea, though, because it scales. Bigger names have more liquidity, so you can manage a lot of money in a market-cap weighted strategy. This is especially true in small cap. The Russell 2000 Value ETF (IWN) has nearly $6 billion dollars in it. Even at a reasonable 0.25% expense ratio, that’s still $15,000,000 in revenues for iShares. This level of assets would be totally impossible for most small cap value managers unless their turnover was extremely low (which can be good, but can also be bad because it means that you aren’t rotating into the best new opportunities).

To be fair, value indexes do have advantages: mainly a lower cost structure (fees, trading, taxes), which is huge. Higher costs are the reason active managers in aggregate do so badly versus indexes.

But still, the strategy itself leaves a lot to be desired. Costs for more “active” strategies will continue to come down, reducing the cost advantage currently enjoyed by indexes.

Benchmarks of the Future

Cap weighting is of course relevant to some extent because Exxon is a far more important stock in general than Seadrill. But cap-weighting also produces weird portfolio outcomes. The smallest 500 stocks in the Russell 3000 Value, for example, have a combined weight of 0.5%. The bottom 1000 stocks have a combined weight of 2.59%. So in the Russell 3000 Value, Exxon (3.1% weight) is more important than the bottom 1000 stocks. That makes most of the stocks near the bottom irrelevant for performance comparisons.

My guess is that with the proliferation of ETFs, we will see more specific “benchmarks” continue to pop up. Deep value managers will have to beat a true deep value benchmark (of say the 100 cheapest stocks in the overall market based on the value metric I used above) rather than the Russell 3000 Value. In these custom benchmarks, the smaller names could play a much larger role. If the future is anything like the past, these more tailored benchmarks will be even harder to beat.

A slight nuance, to avoid seasonality, the stocks in each decile are held for one year like with an annual rebalance, but it’s done on a rolling monthly basis.

October 15, 2015

Are You A Paul Revere or William Dawes?

You know Paul Revere, but you probably don’t know William Dawes. They both left Boston with the same mission on April 18th, 1775: to alert others that the British were coming. Their message reached an area of 750 square miles by the next morning: an incredibly fast diffusion of information given the lack of communications technology at the time. But it was all because of Revere; Dawes was ineffective. You can see the diffusion here:

Revere is in every elementary school curriculum. Dawes is a historical nobody. The reason is that Revere had a far more potent network than Dawes.

Because of his involvement in the Boston Tea Party, Revere was well connected to key persons of influence along his route. He knew the right people to help him spread the message. Dawes, meanwhile, just knocked on random doors.

So Revere’s notoriety was the result not of a faster horse, but of a faster and more connected network. Networks are leverage. Revere told someone who then alerted all the right people in his village. Dawes told someone who often just went back to bed. This is classic “give me a lever large enough, and I can lift the world” stuff.

I write all this because the most important points of leverage in the financial writing world just turned 10 years old. Tadas at Abnormal Returns makes sure that readers around the world get access to some of the best stuff written on markets. A good message isn’t all that useful if no one hears it, and Tadas fixes that problem for so many of us.

If I’ve learned anything in the business world, it is that you should seek out and cultivate points of leverage. I am not naturally good at it, I but I force myself to do it because it is so effective. I encourage you to do the same. Thanks so much to Tadas for everything that he does, and happy 10th.

October 5, 2015

Buybacks and Debt

One advantage for investors and corporations is to be really good at boring stuff. Two things that are boring are capital structure and capital allocation. There are no Apple or Tesla-like events to unveil new strategies for mixing debt and equity, although such an event is funny to imagine.

I’ve written about buybacks (here and here) and how high conviction buyback programs (conducted at cheap relative valuations) have historically signaled good investment opportunities.

A common objection to this “high conviction buyback” strategy is that companies just issue debt to buy back shares, and that the party may end with higher interest rates (you know, the ones right over the horizon).

So are those repurchasing their shares becoming irresponsibly levered to do so? All of what follows is for all U.S. stocks with market caps above $200MM and excludes financial companies.

A Story in Charts

Firms have bought back a lot of stock since the financial crisis. Here is the amount firms have spent on a rolling 12-month basis on gross buybacks, alongside how much they’ve raised by issuing shares (shown as a negative number). The two numbers are combined to get the “net buybacks” line.

Some companies—most notably Apple—have issued tons of debt and simultaneously bought back stock. This is an easy way for a company to change its capital structure. In Apple’s case it may be due to the amount of cash they have overseas, on which they prefer not to be taxed. The number one question I get about the shareholder yield factor is whether or not this debt-funding-buybacks is a big issue and something that should scare us. Asked differently, are companies that are taking on more debt to buy back shares ticking time bombs?

A company gets money from three places: from positive cash flow through its normal business (earnings, basically), from issuing debt, and from issuing equity. There is a “pecking order” for these three options. Companies prefer to finance themselves with internally generated cash first, debt second, and precious equity third.

Here is a comparison of total debt issuance and total equity issuance over the past few decades. You can see that firms vastly prefer to use debt financing, and that there has been a huge surge in debt issued (again on a rolling one year basis) since the financial crisis.

This rise in rolling debt issuance looks scary, but debt is one thing and interest is another. Rates have fallen while operating earnings have continued to grow. Here is the ratio of operating earnings (EBIT) to total interest expense for U.S. firms.

Of course, this drop has happened alongside a steady drop in general interest rates. But it doesn’t exactly look like companies are being reckless.

Buyback Companies vs. Non-Buyback Companies

Let’s create two groups:

Companies that haven’t bought back shares (net buyback yields

Companies with positive net buybacks (buyback yields >0)

We can look at debt in a few different ways for these groups. There is some choppiness to these lines because companies can flip back and forth from one group to the other, but the overall trends are clear.

First, here is the overall debt/equity ratio. The firms buying back shares are less levered.

Here is interest as a percent of operating earnings (interest expense/EBIT), again the companies buying back shares are less levered; they have a smaller interest burden.

Finally, here is the net debt yield of both groups. This yield is calculated as net new debt (issuance minus paydown) divided by total debt. The groups look roughly similar. This means that the buyback companies aren’t really issuing new debt at a higher rate than non-buyback companies.

If you buy an index fund, you are levered because companies use leverage. There is no reason to assume that more debt is a bad thing. It’s been a really cheap source of financing, and it even has tax benefits. Even if you isolate the group down to what I call “high conviction” buyback stocks (those repurchasing more than 5% of their shares in the past year), the numbers all look similar. Debt/equity is 1.45x for this group, less than the market’s 1.6x. The net debt yield is 11%, just a point above the market’s 10%. Ditto for interest burden: high conviction companies spend the equivalent of 11% of their operating earnings on interest expense, while the entire U.S. market spends 16%.

There is way too much nuance within corporate finance to paint the market with a broad brush. Perhaps corporate managers aren’t all dummies and several have instead used the less-than-glamour side of their jobs—managing capital structure and allocating capital—to benefit their shareholders.

September 16, 2015

To Gain an Edge, Run Up Stairs

Where can you find an advantage? This is the question I ask myself more than any other. There are many ways, but this (from Paul Graham) is one of the best:

Suppose you are a little, nimble guy being chased by a big, fat, bully. You open a door and find yourself in a staircase. Do you go up or down? I say up. The bully can probably run downstairs as fast as you can. Going upstairs his bulk will be more of a disadvantage. Running upstairs is hard for you but even harder for him. What this meant in practice was that we deliberately sought hard problems. If there were two features we could add to our software, both equally valuable in proportion to their difficulty, we’d always take the harder one. Not just because it was more valuable, but because it was harder. We delighted in forcing bigger, slower competitors to follow us over difficult ground. Like guerillas, startups prefer the difficult terrain of the mountains, where the troops of the central government can’t follow. I can remember times when we were just exhausted after wrestling all day with some horrible technical problem. And I’d be delighted, because something that was hard for us would be impossible for our competitors.

Start by picking a hard problem, and then at every decision point, take the harder choice.

I see two important ideas in this analogy.

The first is the degree of difficulty. As Paul Graham points out, there is a huge advantage to going the harder way (up vs. down, the road less traveled so to speak).

The second is the stairs themselves. I am 5’11 and weigh 165 pounds. I’d want stairs with lots of turns and twists, and I’d want each step to be short (not steep) because I am more agile than strong. If I was 6’5 and strong as hell I’d want each stair to be steep, to play to my strength. It took me many years to realize it, but there is no point in trying to be well-rounded. The biggest advantages (which lead to the greatest successes) come from strength. When I hear “well-rounded” I think “mediocre.”

The most reliable path to success is to gain an exponential advantage in some area. That can only happen if you start with the stuff you are best at and build on it. At first, I wanted to be well-rounded because I was thinking linearly. Then I realized that I can be 10x or even 100x more productive and skilled in certain very specific areas, if I worked at it. I am not there yet, but I am on the right path. And as the Turkish proverb says, no matter how far down the wrong path you are, turn back.

The recipe, then, goes something like this.

identify your strengths

find the hardest problems for which your strengths may be an advantage in solving

drive hard in that direction.

Find the right stairway, and run up it.

September 10, 2015

Another Thing That Worked in the Past That Won’t In the Future

Meb Faber, one of my kindred investing spirits, has a new book out. He asked twitter for book title ideas. One of my favorite twitter cynics (@ianjoblingrox) joked that he should name it “another thing that has worked in the past that won’t in the future: mean reversion is a bitch.” I laughed pretty hard at that one. I bet Meb did too.

One of the great challenges for quantitative investors is finding new ideas that haven’t yet reached critical mass. So often, a new factor or category rises to the top of a back-testing pile when it is already too late. Like a ton of others, I started checking out asset class trend following stuff AFTER 2008 (Meb had shrewdly done it well before the crash). This stuff happens all the time.

All of my personal money is invested in value/momentum/shareholder yield strategies. New iterations of these pop up all the time (I do a lot of this testing myself). The market has a cruel sense of humor, though. Beware: whatever idea you are hearing the most about may be overly ripe. I hate even writing this because it’s cliché and self-evident, but the key to winning with these factors (if they are going to keep working) is to stick with them for the long term. This is really hard. Backtests are like diet books: tons of great evidence, studies, and so on. They make it really easy to invest or to cut out gluten. But what about a year later, or two, or three? Some new book (with a new diet or backtest) will appear, and we like the new stuff. The worst thing you can do is style hop, but we always do it because stupid evolution made us impatient performance chasers.

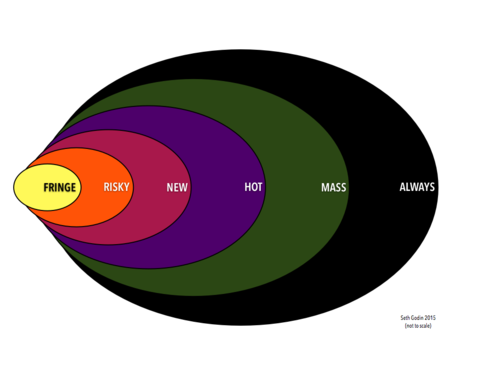

I talk with a lot of people in the investing world, from end investors and advisors, to endowments, pension funds, foundations, and all other kinds of institutions. Everyone is talking about smart beta and factor investing. I even give presentations drafting off this trend (because we have been doing it for a long time and have a much different take on it). This chart below, from Seth Godin via Derek Hernquist, outlines how idea adoption works. As an investor seeking alpha, you want to be towards the left—maybe not all the way (you know the quote about the market’s irrationality and your solvency) but certainly left of center. As Jim Grant always says something like, “successful investing is about having everyone agree with you…later.” Where do you think smart beta is today? I think somewhere between hot and mass. If there was an investing version of this you’d probably want to rename “mass” to “mess.”

Smart beta has been around a long time (ask anyone several decades into a relationship with DFA). But it turns out that while you cannot teach an old dog new tricks, you can give an old strategy a spiffy new name with tremendous results (at least in terms of AUM).

Remember what most of these strategies do: they introduce a tilt (usually a small to moderate one) towards smaller cap value stocks and away from larger cap growth ones. Value = low expectations + general pessimism. If everyone buys value a little bit blindly, that may lead to slightly higher overall expectations (i.e. higher p/e or p/b or ev/ebitda ratios) even though those buying these cheap stocks through a “smart” strategy know nothing about those individual stocks.

With all this in mind, the idea adoption chart is a useful tool for those making or recommending investments. Ask yourself, where does a given strategy lie on the continuum? There is nothing more seductive than a strategy with a compelling narrative and a strong recent track record. Buying those kinds of strategies can still be very good for the long term (I think value qualifies here), but just make sure you aren’t constantly rotating your portfolio from one hot dot to the next. If there is any attainable edge/alpha in investing, this is it: find earlier stage stuff and stick with it through its cycle of efficacy (which may last forever, even if it is diminished like many argue value has become).

The best paths for the future aren’t paths yet, they have yet to be blazed. Question your biases and preferences, hunt where others aren’t.

September 8, 2015

Improvisation

I began to think of children not as immature adults, but of adults as atrophied children. – Keith Johnstone

The topic of this post is an obscure book called “Impro: Improvisation and the Theatre” which was recommended to me twice in a day by 1) a standup & comedy writer (my sister) and 2) a coder turned philosopher (Kevin Simler). Two very different people, same strong book recommendation. It is not a book title that would normally catch my attention. I hate the theatre. I haven’t fully digested the book yet, but it could turn out to be an all-time great.

Good improvisation (or creativity) requires that we “unlock” ourselves and let down our defenses. The methods presented in this book for unlocking ourselves, and rediscovering child-like creativity, are odd and often unappealing, given that we like to project ourselves as sane and in control. But as the author points out, “Sanity has nothing directly to do with the way you think. It’s a matter of presenting yourself as safe.”

Peter Thiel’s Zero to One tells you what you need to do: be truly creative and original in entrepreneurship. This book, without trying to, tells you how to do it. I doubt it’s any coincidence that one of the two people who recommended the book (Simler) was an early and seemingly important employee/coder at Thiel’s big data company Palantir, and that he put this book atop his list of “all time most influential” books.

Three key lessons emerged from the book. Here they are, with quotations to support each:

First, to be creative, we need to bring down our defenses and rigid world views. We should find our most biased beliefs and hunt there. We have to crush our own egos to let the subconscious do our work for us. I always loved the idea that the best creatives (artists, entrepreneurs) aren’t themselves geniuses, instead they each “have” a genius, something for which they are merely a conduit, and their success happened because they stayed out of their genius’s way. Defenses and bias get in the way of each of our geniuses.

Schiller wrote of a ‘watcher at the gates of the mind’, who examines ideas too closely. He said that in the case of the creative mind ‘the intellect has withdrawn its watcher from the gates, and the ideas rush in pell-mell, and only then does it review and inspect the multitude.’He said that uncreative people ‘are ashamed of the momentary passing madness which is found in all real creators … regarded in isolation, an idea may be quite insignificant, and venturesome in the extreme, but it may acquire importance from an idea that follows it; perhaps in collation with other ideas which seem equally absurd, it may be capable of furnishing a very serviceable link.

We have an idea that art is self-expression—which historically is weird. An artist used to be seen as a medium through which something else operated. He was a servant of the God.

As I grew up, everything started getting grey and dull. I could still remember the amazing intensity of the world I’d lived in as a child, but I thought the dulling of perception was an inevitable consequence of age—just as the lens of the eye is bound gradually to dim. I didn’t understand that clarity is in the mind… I’ve since found tricks that can make the world blaze up again in about fifteen seconds, and the effects last for hours. For example, if I have a group of students who are feeling fairly safe and comfortable with each other, I get them to pace about the room shouting out the wrong name for everything that their eyes light on. Maybe there’s time to shout out ten wrong names before I stop them. Then I ask whether other people look larger or smaller—almost everyone sees people as different sizes, mostly as smaller. ‘Do the outlines look sharper or more blurred?’ I ask, and everyone agrees that the outlines are many times sharper. ‘What about the colours?’ Everyone agrees there’s far more colour, and that the colours are more intense. Often the size and shape of the room will seem to have changed, too. The students are amazed that such a strong transformation can be effected by such primitive means—and especially that the effects last so long. I tell them that they only have to think about the exercise for the effects to appear again.

According to Louis Schlosser, Beethoven said: ‘You ask me where I get my ideas? That I can’t say with any certainty. They come unbidden, directly, I could grasp them with my hands.’ Mozart said of his ideas : ‘Whence and how they come, I know not; nor can I force them. Those that please me I retain in the memory, and I am accustomed, as I have been told, to hum them.’ Later in the same letter he says : ‘Why my productions take from my hand that particular form and style that makes them Mozartish, and different from the works of other composers, is probably owing to the same cause which renders my nose so large or so aquiline, or in short, makes it Mozart’s, and different from those of other people. For I really do not study or aim at any originality

I tell improvisers not to feel in any way responsible for the material that emerges… An artist has to accept what his imagination gives him, or screw up his talent.

I was coaxing students into areas that would normally be ‘forbidden’, and that spontaneity means abandoning some of your defences.

My attitude is like Edison’s, who found a solvent for rubber by putting bits of rubber in every solution he could think of, and beat all those scientists who were approaching the problem theoretically.

Second, traditional education destroys creativity by creating rigid and homogenous structures for thinking and for evaluating the world.

Maybe our artists are the people who have been constitutionally unable to conform to the demands of the teachers. Pavlov found that there were some dogs that he couldn’t ‘brainwash’ until he’d castrated them, and starved them for three weeks.

At about the age of nine I decided never to believe anything because it was convenient. I began reversing every statement to see if the opposite was also true. This is so much a habit with me that I hardly notice I’m doing it any more. As soon as you put a ‘not’ into an assertion, a whole range of other possibilities opens out… In a normal education everything is designed to suppress spontaneity, but I wanted to develop it.

Reading about spontaneity won’t make you more spontaneous, but it may at least stop you heading off in the opposite direction; and if you play the exercises with your friends in a good spirit, then soon all your thinking will be transformed. Rousseau began an essay on education by saying that if we did the opposite of what our own teachers did we’d be on the right track, and this still holds good.

People think of good and bad teachers as engaged in the same activity, as if education was a substance, and that bad teachers supply a little of the substance, and good teachers supply a lot. This makes it difficult to understand that education can be a destructive process, and that bad teachers are wrecking talent, and that good and bad teachers are engaged in opposite activities.

Third, every human interaction is a show of status. Understanding what conveys high and low status (and when to deploy them) can be very powerful. For example, try speaking without moving your head AT ALL. This is a high status power move, and it’s very hard to do.

When we tell people nice things about ourselves this is usually a little like kicking them. People really want to be told things to our discredit in such a way that they don’t have to feel sympathy. Low-status players save up little tit-bits involving their own discomfiture with which to amuse and placate other people.

There are people who prefer to say ‘Yes’, and there are people who prefer to say ‘No’. Those who say ‘Yes’ are rewarded by the adventures they have, and those who say ‘No’ are rewarded by the safety they attain. There are far more ‘No’ sayers around than ‘Yes’ sayers, but you can train one type to behave like the other.

Finally I explain that I’m keeping my head still whenever I speak, and that this produces great changes in the way I perceive myself and am perceived by others. I suggest you try it now with anyone you’re with… Officers are trained not to move the head while issuing commands… ‘I find that when I slow my movements down I go up in status… status transactions aren’t only of interest to the improviser. Once you understand that every sound and posture implies a status, then you perceive the world quite differently, and the change is probably permanent.

I have been applying some of these exercises to market research (and in normal conversations) with some really odd and interesting results. Whatever business you are in, or whatever strong feelings or biases you have outside of business, I suggest you question them and tinker with alternatives. The results may surprise you and enrich your life. Also, if you are like me, your neck will be stiff from trying to keep it still.