Patrick O'Shaughnessy's Blog, page 24

September 20, 2016

Michael Mauboussin – Active Asset Management [Invest Like the Best, EP.02]

In this episode, Michael Mauboussin and I discuss everything about asset management: the state of the industry, the active investment process, and Michael’s simple but genius “input/output” method for daily life. This is a full seminar on asset management. It was an awesome conversation.

Be sure to check out all of Michael’s research and his four books, which are linked below. I especially enjoyed his book Expectations Investing, which is mercifully now available on kindle.

If you are not already, subscribe to Invest Like the Best here:

Itunes

Stitcher

Google Play

TuneIn

Books & Resources Mentioned in this Conversation

Reflections on the Ten Attributes of Great Investors (this is a must-read paper by Mauboussin)

(1:31) Contrarian Investment Strategies – David Dreman

(1:38) Expectations Investing – Alfred Rappaport and Michael Mauboussin

(7:05) The Nature of Value : How to Invest in the Adaptive Economy – Nick Gogerty

(16:33) Margin of Safety: Risk-Averse Value Investing Strategies for the Thoughtful Investor – Seth Klarman

(26:39) – Creating Shareholder Value: A Guide for Managers and Investors – Al Rappaport

(54:58) – The Outsiders: Eight Unconventional CEOs and Their Radically Rational Blueprint for Success – William Thorndike

(1:08:18) – Beat the Dealer: A Winning Strategy for the Game of Twenty-One – Ed Thorpe

(1:30:04) – Thinking, Fast and Slow – Daniel Kahneman

(1:31:42) – The Story of the Human Body: Evolution, Health, and Disease – Daniel Lieberman

Show Notes

1:50 – (First question) – Questions Michael about his personal habits and system to being successful. Michael highlights that sleep, exercise, diet are key to being more productive, but the most important one is that he does a lot of reading.

3:41 – A look at how Michael discovers new books to read and why he looks at books of a broad topics and opinions.

5:59 – The books beyond business and investing that are of interest to Michael

7:13 – The discussion turns to whether you can actually learn more through writing and teaching verses reading

10:06 – The conversation shifts to investing and Michael looks at the key function of active managers

11:37 – Where will the market settle in its ratio of active to passive managers and why the market needs active managers

15:23 – Is more passive management good or bad for the active management community?

21:20 – Patrick questions whether industry dynamics are impacting the pool of active managers

25:45 – A deep dive into active management, starting with where the framework of “Expectation Investing” came from.

28:47 – Biggest mistake active managers make is not distinguishing between fundamentals and expectations.

31:10 – High jumper metaphor for value vs expectations.

34:01 – Why Michael is critical of P/E ratios and earnings as the appropriate proxy for the health and success of a business, and what he prefers to use as an overall indicator.

41:05 – Are there qualitative ways of picking visionary leaders and companies that will enjoy huge success like Amazon?

45:24 – Michael turns the table and asks Patrick how they do capital allocation?

47:35 – A look at buybacks and whether companies should be spending as much as they do on them.

51:20 – The focus shifts to whether companies should really be paying a dividend when investors can basically create their own

55:40 – What is the edge that distinguishes active managers from each other.

1:01:42 – The focus shifts to whether the same skill sets are needed for selling assets.

1:03:46 – A look at the state of portfolio construction skill out there and what method Michael would choose to weight a portfolio once the selections are made.

1:07:10 – A look at the often underutilized but possibly effective system known as the The Kelly Criterion

1:12:11 – Patrick looks to get Michael’s take on quantitative investing and if it is taking away the skill from other active managers.

1:16:20 – Why a combination of humans and computers making decisions is the ideal combination.

1:19:26 – The role of intuition in investing

1:22:05 – What would Michael prefer, active stock pickers or index tracking funds?

1:25:39 – Patrick questions Michael about the aspects of his career/life that stand out as being most satisfying.

1:28:00 – Now a shift to see what is Michael most looking forward in his career.

1:30:04 – Michael says Thinking, Fast and Slow would be the one book he would have everyone read.

1:31:23 – A look at Michaels habits when it comes to sleep and nutrition to keep in his best form.

Learn More

For more episodes go to InvestorFieldGuide.com/podcast.

Sign up for the book club, where you’ll get a full investor curriculum and then 3-4 suggestions every month at InvestorFieldGuide.com/bookclub

Follow Patrick on twitter at @patrick_oshag

September 14, 2016

Jeff Gramm – Activist Investing [Invest Like the Best, EP.01]

Welcome to the first episode of Invest Like the Best! You can subscribe here:

Itunes

Stitcher

Google Play

TuneIn

My guest today is Jeff Gramm. Jeff is the founder and portfolio manager at Bandera Partners, an Adjunct Professor at Columbia Business School, and the author of Dear Chairman: Boardroom Battles and the Rise of Shareholder Activism. Jeff and I discuss the history and current state of shareholder activism, and explore how Jeff invests himself, taking large stakes and often board seats in undervalued companies.

My favorite parts of this episode include the history of activism, Jeff’s story about studying and then teaching at Colombia Business School, and our discussion of share buybacks.

Enjoy!

Show Notes

1:30 – (First question) – The Beginning of Shareholder Activism – Ben Gramm spearheaded the active shareholder movement by investigating Northern Pipeline starting in 1920’s. Companies didn’t release nearly as much information and he took it upon himself to travel to Washington, DC to do research on these companies and discover more value for the shareholders.

10:08 – The Proxyteer Movement – The beginning of pro-shareholder populism, folks like Robert Young and Louis Wolfson who got a lot of press when they said that the companies had to protect their shareholders. It was the first time people started to call for having more rights and flex their muscles.

12:30 – The Conglomerate Wars – Hostile M&A and the rise of active investors like Warren Buffet.

13:30 – The Corporate Raiders – Companies are forced to look for new ways to protect themselves from active investors bent on grabbing up the most cash and business as possible. How Warren Buffett was different from other more well-known investors.

15:51 –What happened when Boone Pickens went after Phillips but winds up getting bought out

17:10 – The public perception of the corporate raiders and hostile M&A’s.

19:41 – The remaining history of shareholder activism through the 90’s and early 2000’s

22:07 – Looking into the major shareholders of companies and getting past the massive asset players, like Vanguard, that are most likely passive players but who have major influence on the company.

25:52 – What moves actually provide the most value to shareholder, which is a more recent trend, and is the focus on shareholders actually best for companies?

31:03 – How do companies balance the short term goals of providing shareholder with earnings results verses those that are focused on the long term growth of the company. Jeff argues that share price is not the only metric you can use to really measure the performance of a company or its executives.

36:05 – Shifting into Jeff’s history. He got started in music. (Sample from the band Aden) Why this lifestyle was hard but still educational for him.

38:07 – How did Jeff make the transition from playing in a band to attending Columbia business school. He didn’t know that he was going to focus on investing. He didn’t even know who Warren Buffet was. It was the Joel Greenblatt class on securities analysis that changed his life.

41:52 – Looking into the Joel Greenblatt class and how that class was structured

43:34 – How Jeff got back into teaching at Columbia, with the help of Eddie Ramsden of Caburn Capital, who now teaches at the London Business School. He also saw it as a form of speech therapy to help him face his stutter.

45:44 – A look at Jeff’s actual portfolio. With a special focus on three holdings, Star Gas, Popeye’s, and Tandy Leather.

47:14 – Star Gas, their largest position, the Dan Loeb letters, and investor fatigue.

55:45 – Patrick asks “what does it mean to be good capital allocators?”

57:42 – Patrick questions Jeff on the value of stock buybacks and their real value. They look at some of the thinking of Popeye’s when it came to stock buybacks and why boards don’t understand valuation enough to use buybacks correctly.

1:05:02 – Tandy Leather – Jeff explains their business, which is quite unique, as well as the reason that he owns such a large amount of their outstanding shares.

1:12:28 – A look at how Jeff benchmark’s himself and what impact the investors play into his fund.

1:16:55 – The kindest thing anyone ever did for Jeff professionally

1:18:28 – The one skill that Jeff has the helps him perform better than the average population is his ability to see the big picture.

1:19:34 – Jeff explores why books have a different impact on you when you are younger verse older. But he would force people to check out “The Snowball.”

1:23:17 – Wants to hear interesting people who are productive but have diverse interests, like Tyler Cowen.

Books Mentioned in this Conversation

(26:30) Lynn Stout – The Shareholder Value Myth

(41:36) – Roger Lowenstein – Buffett: The Making of an American Capitalist

(41:42) – Robert Hagstrom – The Warren Buffet Way

(1:21:19) – Alice Schroeder – The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life

(1:21:43) – Benjamin Graham – The Intelligent Investor

(1:21:45) – Benjamin Graham, David Dodd – Security Analysis

Links

For more episodes go to InvestorFieldGuide.com/podcast.

Sign up for the book club, where you’ll get a full investor curriculum and then 3-4 suggestions every month at InvestorFieldGuide.com/bookclub

Follow Patrick on twitter at @patrick_oshag

September 1, 2016

Books That Changed Your Life

A fun question to ask yourself: what books have you read that literally changed your life? I read a lot of great books, but when I went through my list of about 1,000, there were only 8 (!!) that rewired me so much that I can say I was changed after reading them. These books are old—median: 119 years old, average: 743 years old. I explain the impact of these 8 books below.

This post is a replication of an email I sent to members of the book club. I post examples like this a few times per year so you can get a feel for the club. You can sign up here, if you are not already.

These all pair nicely with one of the more popular articles I’ve written, an explanation of my personal philosophy: Growth Without Goals.

I’d love to hear your answer to this same question. What book(s) changed your life? Let me know in the comments.

***

We lie in the lap of immense intelligence, which makes us receivers of its truth and organs of its activity. When we discern justice, when we discern truth, we do nothing of ourselves, but allow a passage to its beams.

***

Self- Reliance by Ralph Waldo Emerson (175 years old)

The opening quote above comes from Emerson, who urges us to LISTEN to ourselves. Sadly, almost no one does. Instead we rely on others, “experts,” conventional viewpoints. If only we would cultivate an independent, seeking mind, we’d be better and happier people. We must grow from the inside out, not the other way around.

In every work of genius we recognize our own rejected thoughts…[we must realize that] envy is ignorance; that imitation is suicide.

Emerson didn’t mince words, when I read the below passage, I always think of George Bernard Shaw’s quote, “the reasonable [wo]man adapts himself to the world; the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable [wo]man.” Emerson was “unreasonable.”

Society everywhere is in conspiracy against the [wo]manhood of every one of its members. Society is a joint-stock company, in which the members agree, for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater. The virtue in most request is conformity. Self-reliance is its aversion. [Society] loves not realities and creators, but names and customs.

Emerson thought that “one should strive for an original relation to the universe. Not a novel relation, just one’s own.” As his biographer put it, “Emerson’s lifelong search, what he called his heart’s inquiry, was ‘Whence is your power?’ His reply was always the same: ‘From my nonconformity.’”

Since reading this for the first time, I have worked hard on nonconformity. It’s a wonderful pursuit.

BONUS: If you like Self-Reliance, you’ll love most of what Paul Graham writes. Especially, What You Can’t Say.

Upanishads (~2,800 years old)

The closest thing I have to a religious text. No book changed my perspective as much as this one. I was a different person when I finished it for the first time, years ago. My wife would confirm this fact! If you want to understand the power of destroying your ego and being kind and generous, this will be your guide. Try starting with the Katha Upanishad—a story of a young boy having a conversation with the God of death on life, knowledge, and liberation.

The hair on the back of my neck stands up every time I read this:

The Self in man and in the sun are one. Those who understand this see through the world And go beyond the various sheaths Of being to realize the unity of life. Those who realize that all life is one Are at home everywhere and see themselves In all beings. They sing in wonder: “I am the food of life, I am, I am; I eat the food of life, I eat, I eat. I link food and water, I link, I link. I am the first-born in the universe; Older than the gods, I am immortal. Who shares food with the hungry protects me; Who shares not with them is consumed by me. I am this world and I consume this world. They who understand this understand life.” This is the Upanishad, the secret teaching.

Influence by Robert Cialdini (32 years old)

The single best book on, well, influence. Once you understand how to use reciprocity, consistency, social proof, liking, authority, and scarcity, you’ll be far better at convincing people agree with you, to do things you want, or to buy things from you. These principles can be used for nefarious purposes. Use them with integrity, and they are powerful. This book is ten times better than others in its category. It is probably the best business book of all-time.

A Hero with a Thousand Faces / Reflections on the Art of Living by Joseph Campbell (67 years old)

The story arc of heroes is similar across time and cultures because this arc reflects the universal story of human life and experience. Many never follow the “call to adventure” by crossing the threshold into the unknown, but those that do can be “heroic.” Campbell urges us, like many authors on this list, to make the leap. This is one of those books/authors that have you saying “Wow!” to yourself as you read. I’ve listed two of Campbell’s books here. I loved Hero with a Thousand Faces, but it’s somewhat academic. Reflections on the Art of Living is more accessible and has lots of the same ideas.

“A bit of advice given to a young Native American at the time of his initiation: “As you go the way of life, you will see a great chasm. Jump. It is not as wide as you think.” And so, to return to our opening question: What is—or what is to be—the new mythology? It is—and will forever be, as long as our human race exists—the old, everlasting, perennial mythology, in its “subjective sense,” poetically renewed in terms neither of a remembered past nor of a projected future, but of now: addressed, that is to say, not to the flattery of “peoples,” but to the waking of individuals in the knowledge of themselves, not simply as egos fighting for place on the surface of this beautiful planet, but equally as centers of Mind at Large—each in his own way at one with all…

Walking by H.D. Thoreau (156 years old)

This essay pushed me into the woods, which is where I now do almost all of my productive thinking and spend time with my family. I now spend 10% of my time walking or running through the forest, and it started with this essay years ago.

“No wealth can buy the requisite leisure, freedom, and independence, which are the capital in this profession. It comes only by the grace of God. It requires a direct dispensation from Heaven to become a walker. You must be born into the family of the Walkers.”

I love this because my middle name (and my mom’s maiden name) is Walker.

Antifragile by N.N. Taleb (4 years old)

This book is thrilling to read. It sparkles with intelligence and authenticity. Say what you will about Taleb, but he lives by his code: “if you see a fraud and don’t say fraud, you are a fraud.” I read this book as a guide to sources of power, and as such it ties in nicely with Self-Reliance (interesting connection: Taleb and Emerson were both heavily influenced by Montaigne—an authentic person if there ever was one). Here are a few passages which reflect what I love about this book.

How do you innovate? First, try to get in trouble. I mean serious, but not terminal, trouble. I hold—it is beyond speculation, rather a conviction—that innovation and sophistication spark from initial situations of necessity, in ways that go far beyond the satisfaction of such necessity (from the unintended side effects of, say, an initial invention or attempt at invention). Naturally, there are classical thoughts on the subject, with a Latin saying that sophistication is born out of hunger… The excess energy released from overreaction to setbacks is what innovates!

There is an Irish revolutionary song that encapsulates the effect: The higher you build your barricades, the stronger we become.

Curiosity is antifragile, like an addiction, and is magnified by attempts to satisfy it—books have a secret mission and ability to multiply, as everyone who has wall-to-wall bookshelves knows well.

As One Is by Jiddu Krishnamurti (~80 years old)

My modern(ish) triumvirate of philosophers: Emerson, Thoreau, and Krishnamurti. Maybe Krishnamurti is the most penetrating and challenging. Krishnamurti will knock you over. He is aggressive. He confronts you. He won’t let you escape. I wrote about one passage in particular that stopped me in my tracks in Growth without Goals.

I kept this list to books and essays, but this is a good spot to mention a 9th work that changed my life: T.S. Eliot’s poem Four Quartets. Like Krishnamurti’s work, Eliot’s poem focuses on the ideas of past, present, and future–making it clear that past and future are illusions.

Tao Te Ching (~2,600 years old) Translation 1 or Translation 2

I read this as much as possible. It is a way of re-orienting yourself and your behavior if you’ve wandered a bit astray. It describes the fundamental truth about the world (Tao) and existence in general, and offers methods for living well. A few ideas that are wonderfully simple and effective:

“create without possessing” “accomplishing without taking credit” “Desiring not to possess or accumulate which is only temporal”… doesn’t exactly describe the western mindset, does it!

“The five colors blind the eyes The five sounds deafen the ears The five flavors deaden the taste Excessive desires will madden the mind Excessive possessions preoccupy the mind with fear The more you desire, the more you’ll be discontented from what you have The Sage fills his belly, not his eyes The Sage satisfies his inner desires with what cannot be seen, not with the external temptations of the world”

A question I always ask myself because of this book: on what external things am I dependent? What desires drive my actions? Then: remove or reduce external dependencies. Don’t just act according to desire. Find stillness. Recognize and participate in unity.

What a beautiful text this is.

***

You have probably ascertained the most common theme in these 8 books: power and well-being come from within, not from without. But we spend so much time defining ourselves and making decisions based on that which is external and deprives us of power and the potential to experience abiding joy.

Maybe Joseph Campbell said it best: “It takes courage to do what you want. Other people have a lot of plans for you. Nobody wants you to do what you want to do. They want you to go on their trip, but you can do what you want. I did. I went into the woods and read for five years.”

Collectively, these books have given me courage. I hope they do the same for you.

August 4, 2016

Growth Without Goals

I.

Four years ago, soon after learning that my wife was pregnant with our first child, I was sitting on the Metro-North commuter train, reading. I was thinking about being a father; specifically, I was wondering what it would take to be a great father. Unconditional love and support seemed obvious. Patience too. But what could I teach my son Pierce and future kids that would help them live good, fulfilling lives? That day, I read the following passage from Jiddu Krishnamurti:

Man lives by time. Inventing the future has been his favorite game of escape. We think that changes in ourselves can come about in time, that order in ourselves can be built up little by little, added to day by day. But time doesn’t bring order or peace, so we must stop thinking in terms of gradualness. This means that there is no tomorrow for us to be peaceful in. We have to be orderly on the instant.

It is only then [when the mind is completely still] that the mind is free because it is no longer desiring anything; it is no longer seeking; it is no longer pursuing a goal, an ideal—which are all the projections of a conditioned mind. And if you ever come to that understanding, in which there can be no self-deception, then you will find that there is a possibility of the coming into being of that extraordinary thing called creativity.

II.

Inventing the future is another way of saying “setting goals.” Success, especially in the West, then becomes about achieving those goals. We accumulate accomplishments and call it success. Success means something very different to me, and I think being a great father will be about effectively communicating this different definition of success to my kids. Success is about building a set of daily practices, it is about growth without goals. Continuous, habitual practice(s) trumps achievement-based success.

I think “accomplishments” are traps. Accomplishments, by their very definition, exist only in the past or future—which are not even real things. Pride is the worst of the seven sins and it is closely related to past and future accomplishments.

[T]he world moves

In appetency, on its metalled ways

Of time past and time future

Here is a place of disaffection

Time before and time after

III.

Most of the things we do and believe result from stories that we tell ourselves. The modern secular world looks down on religious traditions for their faith in unempirical stories, but we tell ourselves stories in the same way. “Most millionaires sincerely believe in the existence of money and limited liability companies.” To be fair, many of these stories have indeed led to human security and luxury—a better world. Some stories, though, are silly and destructive.

The story that we are told in America is that achievement—money, power, awards—equals success. I had this idea deeply imbued at a young age. We are desire-fulfilling machines: the mind literally IS desire. My desires–and therefore my actions–were shaped by these stories, like the story of achievement. Now I try to ask, what stories are we telling ourselves that are bullshit?

I wanted to write a book. Rather, I wanted to have written a book because I could carve a notch on my achievement belt. I even wanted to do it at an earlier age than my father had (he was 33 when his first book came out). How ridiculous! It felt good—not great—for a day.

Now I just want to explore. That may mean blog posts, research papers, new investing strategies, letters, podcasts, long periods of nothing, or maybe another book. Who knows? Exploration is continuous, there is no end point. Focusing on exploration is very rewarding all the time. It may produce things that look like end points, like achievements, but those things are just byproducts.

The same idea applies to investing. The continuous goal, in my case, is a portfolio that has distinct advantages versus the market along dimensions like value, momentum, capital allocation, etc. There are no price targets, no return targets, no staking my results on a given outcome for a given company. A goalless process like this is incredibly hard to maintain in an industry which has convinced itself (I despise this particular “story” we’ve told ourselves) that the passage of three months requires that we get together and retrofit a narrative to explain what was likely pure noise. But hard as it is to maintain, I believe that a continuous process, informed by deep research, is the only way to beat Vanguard.

IV.

Jeff Bezos is an incredible figure. He is known for his focus on the long term. He has even funded a clock in West Texas which ticks once per year and is built to last 10,000 years—an ode to thinking long-term.

But I now realize that the key isn’t thinking long-term, which implies long-term goals. Long-term thinking is really just goalless thinking. Long term “success” probably just comes from an emphasis on process and mindset in the present. Long term thinking is also made possible by denying its opposite: short-term thinking. Responding to a question about the “failure” of the Amazon smartphone, Bezos said “if you think that’s a failure, we’re working on much bigger failures right now.” A myopic leader wouldn’t say that.

My guess is that Amazon’s success is a byproduct, a side-effect of a process driven, flexible, in-the-moment way of being. In the famous 1997 letter to shareholders, which lays out Amazon’s philosophy, Bezos says that their process is simple: a “relentless focus on customers.” This is not a goal to be strived for, worked towards, achieved, and then passed. This is a way of operating, constantly—every day, with every decision.

V.

There is an app called “Way of Life” which helps put this idea of “continuous goals” into practice. It’s just a daily checklist of things you want to do. As you check things off day after day, you create a long chain of green that you won’t want to break. It’s very effective. Here are the key ones on my list.

No complaining

100 push ups

Run

No sugar

Write 500 words

Read

Don’t eat until noon (intermittent fasting)

Floss

Spend time in the woods (running or hiking)

Family Time

Level Up

The last one—level up—is my favorite. To be able to put a check mark next to “level up,” I have to do something that day which is new or better than what I have done before. I recorded an interview with a really interesting author and investor the other day. Level up. I ran a new trail in the woods that I’d never explored before. Level up. I sent my wife flowers and a note. Level up. This simple reminder has proved invaluable.

These things are their own reward. I did not back into these things from some other goal. They are continuous goals themselves. They make daily life quite wonderful, and I bet they will continue to lead to things that look like achievements from the outside.

Maybe Scott Adams said it best:

To put it bluntly, goals are for losers. That’s literally true most of the time. For example, if your goal is to lose ten pounds, you will spend every moment until you reach the goal—if you reach it at all—feeling as if you were short of your goal. In other words, goal-oriented people exist in a state of nearly continuous failure that they hope will be temporary. That feeling wears on you. In time, it becomes heavy and uncomfortable. It might even drive you out of the game… If you achieve your goal, you celebrate and feel terrific, but only until you realize you just lost the thing that gave you purpose and direction. Your options are to feel empty and useless, perhaps enjoying the spoils of your success until they bore you, or set new goals and reenter the cycle of permanent presuccess failure.

Goals still sneak their way into my brain. I try, but sometimes fail, to snuff them out. I am working on it. There is always that stupid interview question: where do you see yourself or your company in five years. Instead, we should ask, what things do you think are important to do every day?

VI.

I am incredibly happy in the woods. I love trees that grow sideways out of rocks and hills. They start small and survive because of some available sunshine. They grow whatever direction they must to reach more light. Their slow growth allows them to ultimately reach a form that looks tenuous or even impossible, but they are firmly rooted. I like to imagine the early days, the tree’s roots tinkering in the soil, quickly abandoning failed paths, building deep systems along better paths. These bizarre and beautiful trees end up this way because of a simple process. They operate according to a continuous goal, from the bottom up.

It is in these woods that I’ve begun to teach my son (and will soon teach my daughter) this lesson: explore for the sake of exploration, without expectation. Discover essence in your surroundings and in yourself, free from external conditioning (stories) and expectations. Build from the inside out and bottom up. Great habits and practices make a great and successful life. Cultivate those and the rest will take care of itself.

If you haven’t read Krishnamurti, please do. Try As One Is or Freedom From the Known.

T.S. Eliot

Yuval Noah Harari (Sapiens author)

July 20, 2016

Peculiar Stock Leadership in 2016

The below exploration of market returns in 2016 was written by my colleague Travis Fairchild.

Bank of America started tracking the performance of active managers in 2003, and 2016 has—thus far—been the worst year on record for active managers: only 18% of large cap managers outperforming the Russell 1000 through June 30th. The Russell 1000 Value has beaten the Russell 1000 Growth, but the companies with the best returns this year have had a peculiar profile. You don’t see many pitch books that say: “we buy stagnating or low growth businesses trading at average prices,” but that is the profile of the stocks which have led the market in 2016. Let’s explore.

Most Value Factors are underperforming Price to Book; Russell’s definition of Value

Below is a chart showing the year-to-date cumulative excess return for various value factors (measured by the performance of the best decile for each factor) versus our equal-weighted U.S. Large Stocks benchmark. Year-to-date all but dividend yield are negative and price to book is beating all other factors. Any active managers with a focus on cheap valuation (based on something other than dividend yield) is likely seeing that focus detract from performance. It is likely that dividend managers represent a large portion of that 18% of managers that are outperforming.

Our preferred definition of value uses a combined measure from price-to-sales, price-to-earnings, free cash flow-to-enterprise value, EBITDA-to-enterprise value, and shareholder yield; the gap between this value composite and Book to Price is 6% year to date. This is a significant gap and a very uncommon one.

The histogram below shows just how uncommon this gap is; in only 6% of all observations on record have we seen a gap this large. Since 1963 the value composite has outperformed price to book in 57% of 6 month rolling periods and in over 70% of rolling 1 year periods.

The histogram below shows just how uncommon this gap is; in only 6% of all observations on record have we seen a gap this large. Since 1963 the value composite has outperformed price to book in 57% of 6 month rolling periods and in over 70% of rolling 1 year periods.

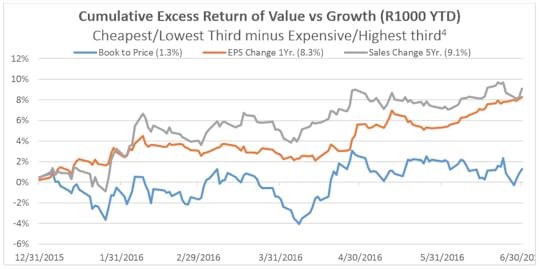

Low Growth Companies are Driving the Outperformance of Value Indices

Year to date, the Russell 1000 Value is beating the Russell 1000 Growth by a margin of almost 5%. But as we saw above, most measures of “value” are doing poorly so far this year, so why the large gap between Russell’s value and growth indexes?

The answer lies in how Russell defines value vs. growth. Russell uses a ranking formula which is 50% value (Price to Book) and 50% growth (EPS growth and 5 Year Sales Growth) to decide where each stock falls on the Value/Growth spectrum. Anything cheap and/or with horrible growth is considered value and anything with great growth and/or that is extremely expensive is considered growth. This methodology creates a dynamic where a portion of the Russell Value index is actually slightly expensive stocks that have very bad trailing sales growth and expected EPS growth. Likewise a portion of the growth index will be stocks with below average or negative growth but defined as growth due to their extremely expensive valuations.

In rare occasions these little talked about groups of stocks can drive performance of the style indices, and that is exactly what we are seeing this year in the Russell 1000 Value. Below is a chart that shows the excess return of value vs growth for each of the factors used in Russell’s methodology. While we used decile portfolios to highlight different value factors above, we now tailor the analysis to more closely match Russell’s method (which carves the market into thirds). We start with the constituents of the Russell 1000, and calculate the return difference between the top third and bottom third by each factor. For example, the return of +1.3% for the price to book in the chart below is the result of

Ranking the cheapest third of stocks by price-to-book in the Russell 1000 to build our portfolio

Calculating the return (weighted by market capitalization) of that portfolio for the year

Doing the same for the most expensive third

Subtracting one from the other

You can see that while the cheapest third of stocks by price-to-book has outperformed the most expensive third within the Russell 1000, the difference is relatively small. The real story is the outperformance of low growth over high growth. Companies with the worst sales and earnings growth have outperformed those with the best growth by 8-9% so far this year. The gap of value vs growth indices is more a surge in stocks with terrible sales and earnings growth, and less a triumph of traditional cheap over expensive.

Any active manager avoiding companies with dismal growth will avoid the companies driving returns in the benchmark.

Top 10 Contributors in Russell 1000 Value are Not Cheap and have Negative Growth

This becomes even more apparent when you look at the profile of the top performers in the Russell 1000 Value index. The ten names below—which were the top contributors to the benchmark return— make up 20% of the benchmark and contributed 3.5% to the benchmark’s return of 6.3%; over half of the year to date return.

For each stock, we show the percentile rank at the start of the year within the Russell 1000 of the Price to Book Ratio, EPS growth, and 5 year sales growth numbers where 1 would be the cheapest/highest growth percent and 100 the most expensive/lowest growth. Only 3 of the 10 stocks are even in the cheapest 1/3 of U.S. companies by price to book and the average is just under the median. Further, 9 of the 10 names had negative (i.e. shrinking earnings) to start the year and more than half had shrinking sales numbers. The average of these 10 names had earnings that shrunk -27.5% over the last year, a reduction in total sales of -8.5% over the last five years, and they were only slightly less expensive than the market median.

Using Russell style benchmarks to build a market narrative makes sense: they are widely followed benchmarks. But so far this year, the returns of value versus growth are misleading. Cheap is not beating expensive, on average, but low growth is crushing strong growth. Over the longer term, the best strategy is to be long cheap stocks—not long low growth businesses. But being long cheap stocks has thus far failed in 2016.

Bank of America Merrill Lynch US Equity and Quant Research. They began tracking performance of active managers in 2003.

Defined as all publicly traded U.S. companies that have market caps greater than average (non-ADRs).

All rolling periods from 1963 to 2015 using all investable U.S. Large Stocks in the COMPUSTAT database.

From 1/1/2016 to 6/30/2016 the Russell 1000 Value returned 6.3% while the Russell 1000 Growth is up 1.35%

July 19, 2016

Full Reading List

In April, 2014, I decided to start emailing my friends book recommendations every month. After two years, hundreds of books, and seven thousand new readers, I’ve finally pulled the full list together. This is the full archive of everything I’ve ever recommended.

This list is meant to foster a community of book lovers. Share it! Send the PDF (which you can download below) or link (http://investorfieldguide.com/wp-cont...) to your family, friends, co-workers, and enemies (broad reading, like extensive travel, kills prejudice).

Happy Reading,

Patrick (patrick.w.oshaughnessy@gmail.com, send me book recs!).

Here is the link: Full Reading List

p.s. If you aren’t already on the email list, you can get 3-4 books every month by signing up for the “Book Club” here.

June 23, 2016

The Market’s Buyback Yield Is Not A Timing Tool

Almost nothing written about investing is actionable. It’s why I’ve read less and less on investing and tried to instead do more and more work myself—to reach my own conclusions, conclusions which can be applied over long investing horizons. The action most appropriate is almost always: do nothing.

One thing that is written about a lot (way too often) is the level of buyback activity in the market (I’ll use the S&P 500 to represent the market). While certain aspects of buybacks are indeed very actionable at the stock level (i.e. using buyback yield as an investment “factor”, read here and here), the market’s overall buyback yield is not something on which you should base any investing decisions.

Quickly, here is the history of buybacks, first in raw dollars terms (a useless but frequently quoted statistic—imagine someone saying “beware: earnings in raw dollars at all time high”) and then in yield terms (more useful/interesting). I show both gross buybacks and net buybacks (subtracting share issuance) in both charts.

Let’s focus on net buyback yield to see if there is any relationship (since 1987 when the best data on buybacks and issuance becomes available on the statement of cash flows) between current buyback yield and forward returns.

You don’t have to get too fancy with the statistics here to see there is no real relationship over the past 30 years. With R-squared’s of 3% and 9% for forward 1- and 3-year returns, not much of the variance of stock returns are explained by starting buyback yield.

The periods on the lower right are all the periods surrounding the global financial crisis: when buyback yield was high, and subsequent returns were very low. Net buyback yield back then was 4.0%. Today we are at about 2.5%. Note: this 2.5% is still inflated, because my way of calculating net buybacks is simple cash used for buybacks minus cash raised through issuance. This does not take into account share issuance which results in no cash inflow (like in a cash + stock or all stock acquisition). Because large-cap companies tend to acquire smaller ones, this brings the S&P 500’s weighted average change in share count down close to zero (0.6% or so).

Other measures like “Shiller’s CAPE” of my friend Jesse Livermore’s “Percentage allocation to equities” have much stronger statistical relationships with forward returns—and even those may not be actionable (CAPE has been “elevated” for decades). For more on buybacks at the market level, this is very sensible.

I am not saying buybacks aren’t interesting and important. I am just saying that they aren’t a good tool for getting excited or worrying about the market and its near-term potential for returns. Stay tuned for a much longer story that focused on buybacks at the stock level—which is far more interesting!

May 31, 2016

Two Star Managers and the Wheel of Fortune

Here is an idea that is doomed to fail: a podcast or interview series with 2-star fund managers. We hear about strategies, portfolio managers, and asset classes after the fact—when they’ve delivered performance numbers that make our mouths water. We cannot blame the financial complex for focusing on strongest returns: it leads to more interesting stories, more sales, more page views, more…pick your metric. To do it any other way would be like putting the Boston Celtics on the cover of Sports Illustrated after this year’s NBA playoffs, instead of the Lebron James- or (more likely) Steph Curry- led champions, which would make no sense.

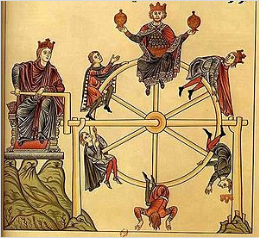

Interviewing, profiled, and buying at performance peaks is the central problem in active investing along the entire chain: from end/individual investor, to intermediary, to asset manager. Styles and strategies tend to be cyclical, but we are humans and we extrapolate in straight lines, not in circles. The entire industry is branded with “past performance is not indicative of future results” because we are wired to think that way: in most other places, past performance is indicative of future results!

When I said I would love an interview series with 2-star fund managers, the most common response was “just go watch the 5-star interviews from a few years ago.” That is funny, because it is so often true. We know that strategies—and the portfolio managers behind them—mean revert. The wheel of fortune, “rota fortunae,” follows this pattern of mean reversion (you can read more in Deep Value). Starting from the top in the image below, we see these four stages: 1) I reign (5-stars!) 2) I reigned (2-3 stars) 3) my reign is finished (massive outflows) 4) I shall reign (performance comeback).

Picture this big wheel of fortune, because it sits–always turning–behind financial markets. 5-star managers (or, in institutional-speak, top quartile/decile managers) “reign.” Some reigns last a long time, but the numbers show that precious few last forever—especially when AUM grows and reduces one’s potential edge. When a manager reigns, it is usually because of strong performance, which brings spoils: assets, personal wealth, clout, and requests for interviews. Hidden behind the spoils: scrutiny, attention, competitors who mimic, steal, or improve your strategy, and an increased probability that the strategy will work less well or not at all in the near- to mid- term future. This all fuels the wheel!

Having lived all of this myself, I can say with a confidence earned through several spins of the wheel that the most important things, for any strategy/portfolio manager are:

i. To remain extremely disciplined by working a system.

Having a system is the most important thing, but that is pretty common these days. Abandoning a system happens most often at the top and bottom of the wheel. At the top, many managers who relied on less liquid/smaller cap opportunities to achieve strong performance move up the capitalization spectrum, or launch new strategies (spreading/diluting their attention) to accommodate more assets under management. (Side note: I have no clue how any non-quant could manage multiple strategies/portfolios and succeed). At the bottom, any system will feel broken—out of date and out of touch. Which leads to…

ii. Can withstand increased external pressure causes by periods of underperformance

This should be 1A), because it is related to discipline. The pressure to change your stripes during periods of underperformance is immense. In my experience, managers have more resolve than their investors (on average—I know many wonderful exceptions to this rule). During initial drawdowns, investors understandably want to know what managers are doing to “fix” the problem. The problem is usually that there is nothing to fix. Even the best system will fail very often. Just a little more than 50% of value stocks beat the market, on average. This is so frustrating, because, in almost every other pursuit, failure means something can be improved upon. In investing, you are guaranteed to have lots of failures, and most of those failures say very little about the quality of the system that produced them! What produces so many awful investor outcomes is mistaking a single failed investment for a failed system.

iii. Humility

When I see hubristic PMs, my first thought is always: they have not dug deep enough. I am often reminded, studying financial markets, of Umberto Eco’s concept of the “anti-library:” a collection of books not yet read. What I find is that the more I dig—on a factor, a stock, a strategy, whatever—the less I know. Sure I learn as I dig, but for every one thing I learn, I become aware of three new things that I don’t know. I know a few incredibly talented, deep fundamental stock pickers who have had great and sustained success. They are confident, but they are also insanely humble—because they realize how much they don’t or can’t know.

iv. A willingness on the part of the portfolio manager(s) to communicate and educate as much as possible, especially during tough times.

For all involved, maybe this is the most important thing. To survive a full turn of the wheel, you need true conviction. The only way for investors to gain that conviction is to understand the strategy. This requires a lot of care, because there is always more to learn. This is all I do and all I think about, yet still there are still nuances I find, almost every time I go looking. This means that for an investor to stick with a strategy—especially an active once which is unique enough to make it worth the investor’s while–net of fees—they need to understand it deeply.

v. Be open to change, which means admitting you don’t do everything perfectly

I always hear the joke that allocators/investors in the industry love innovation but hate change. Again, funny because it’s true. Investing strategies need an immutable underlying set of principles—a bedrock philosophy—like, say, value investing. For me, it’s that certain factors drive returns (value, momentum, shareholder yield). But the implementation of that philosophy can and should evolve and improve. We can measure “value” far more accurately than we could 15 years ago. Constant tinkering is bad, but smart, infrequent improvements almost always make sense.

***

While an interview series with 2-star or bottom quartile managers may be doomed to failure, it may prove to be a great hunting ground for managers you want to invest with—provided they have attributes like the ones listed above (humility is all but assured ;). The same system that makes you feel brilliant at the top will make you feel like a moron at the bottom, and the wheel will keep turning. Markets are incredibly hard to beat. You can probably only gain a small edge. Letting that edge work is the hardest part.

There is a Taoist story of an old farmer who had worked his crops for many years. One day his horse ran away. Upon hearing the news, his neighbors came to visit.

“Such bad luck,” they said sympathetically.

“We’ll see,” the farmer replied.

The next morning the horse returned, bringing with it three other wild horses.

“How wonderful,” the neighbors exclaimed.

“We’ll see,” replied the old man.

The following day, his son tried to ride one of the untamed horses, was thrown, and broke his leg. The neighbors again came to offer their sympathy on his misfortune.

“We’ll see,” answered the farmer.

The day after, military officials came to the village to draft young men into the army. Seeing that the son’s leg was broken, they passed him by. The neighbors congratulated the farmer on how well things had turned out.

“We’ll see” said the farmer.

May 3, 2016

Shrinkage vs. Growth

The most interesting story in the history of capital allocation was the rapid growth and then steady shrinking of Teledyne, a conglomerate formed by Henry Singleton in 1960. Teledyne spent the 60’s growing through acquisitions—130 companies in total, bought for twelve times earnings or less—funded in large part by the issuance of new shares of Teledyne stock and debt. One of its last acquisitions in this period was Ryan Aeronautical in 1969—to which we will return. During this acquisitive phase, between 1961 and 1971, sales and earnings grew 244x and 556x alongside large growth in shares outstanding and debt. Earnings were sometimes volatile, but Singleton didn’t care: he focused on cash flow.

Singleton grew the company by using expensive Teledyne stock to acquire less expensive businesses. When no more cheap businesses were available, he completely changed his strategy and began cannibalizing his own company. Between 1971 and 1984, he’d become the pioneer of large scale share repurchases. During this second period, sales and earnings still grew, but by just 2.2x and 7.1x. Earnings per share, however, exploded from $8.55 to $353. When it was all said and done, Singleton bought back an extraordinary 90% of Teledyne’s shares.

Singleton was a value investor on the way up and on the way down. During his period of acquisitions, he issued shares at an average multiple of 25x earnings (and, as noted, paid less than 12x earnings for the companies he was buying). During the period of massive share repurchases, he paid an average of just 8x earnings for Teledyne’s stock. The full journey is remarkable: In 1961, Teledyne had 400,000 shares and 13 cents of EPS. In 1984, Teledyne had 900,000 shares and $353(!) of EPS. During Singleton’s reign, Teledyne stock returned more than 20% per year while the S&P 500 returned just 8%.

***

In 1999, Teledyne sold Ryan Aeronautical to what is now Northrup Grumman, then in the midst of an acquisitions binge of its own:

http://www.northropgrumman.com/AboutU...

At the start of 2005—when its total shares outstanding peaked after 10+ years of large acquisitions—Northrup Grumman had 364MM shares outstanding.

Ever since they’ve embarked on a Singleton-esque reduction of total shares through repurchases. Today they have 181MM shares outstanding, a reduction of about 50%. Over the same period, Northrup’s market cap and net income have roughly doubled (a little more impressive than the overall S&P 500, where total market cap is up about 78% and net income up 58%). Yet over this same period(1/31/2005-2/28/2016), Northrup’s stock is up 460% (16.7%/year) while the S&P 500 is up 124% (7.5%/year).

Why the huge gap in returns, despite growth numbers in the same ballpark? Returns can come from 1) growth of earnings 2) changes in valuation and 3) return of capital to shareholders through dividends and buybacks. Grumman’s earnings have grown, but its P/E ratio is the same today as it was in 2005. The major source of returns has been dividends (straight cash return) and buybacks, which have significantly affected earnings per share. While net income has doubled, earnings per share have almost quadrupled because of the steady reduction in share count.

In the first paragraph of Northrup’s 2015 annual report to shareholders, they highlight the $3.2B spent on repurchases in 2015 and the $4.3B that it is still authorized to repurchase in the future. They, like Singleton, care about cash flows. As they say later in the report, “We believe free cash flow is a useful measure for investors to consider as it represents cash flow the company has available after capital spending to invest for future growth, strengthen the balance sheet and/or return to shareholders through dividends and share repurchases. Free cash flow is a key factor in our planning for and consideration of strategic acquisitions, payment of dividends and stock repurchases.” We don’t know what the future holds for Northrup, but clearly, the significant reduction in share count since 2005 has been a huge part of its total return to shareholders.

These stories are important because while we tend to want growth in all things—from corporate earnings to overall GDP—growth isn’t everything. Often names like Northrup go unnoticed because their sales, earnings, and market caps aren’t growing as fast as the most exciting stocks in the market.

Looking over the same period (2005-2016) for other stocks in the S&P 500, we see a similar trend as we saw with Northrup. The 10% of stocks which have reduced their share counts by the greatest percentage since 2005—stocks like Autozone, Travelers, Coca-Cola Enterprises, AmerisourceBergen, or Fiserv—have done very well as a portfolio. On average, they’ve reduced share count by 47% and they’ve outperformed the S&P 500 by an average of 88%. What’s interesting is that this strong performance has happened despite the fact the median market cap and net income growth has been lower for these companies than for the average S&P 500 stock.

Buybacks are not a panacea. But used properly, share repurchases can be a powerful tool. Through smart share repruchases (that aren’t simply fueled by debt, and that are performed at cheap prices) companies can produce extremely attractive, decade-long returns for shareholders that surpass their underlying fundamental growth.

The Outsiders by William Thorndike

IBID

IBID

Please note this is a simple, equal weighted average of the returns for these stocks minus the return of the (cap-weighted) S&P 500. Because equal weighting tends to do better, some of this 88% is attributable to the equal-weight phenomenon.

April 8, 2016

Alpha or Assets

More and more investors are buying “factor” based strategies which invest using measures like valuation and low volatility, but the most popular strategies are applying factors in the wrong way. Strategies should be built for alpha, not scale—but the asset management industry has gone in the opposite direction.

Most factor-based strategies—commonly called Smart Beta—have hundreds of holdings and high overlap with their market benchmark. The far more powerful way to apply factors is to use them first to avoid large chunks of the market and then build more differentiated portfolios of stocks with only the best overall factor profiles. While not as scaleable as smart beta, this alpha-oriented approach has led to much better results for investors.

***

Professionally managed investment strategies have two components: an investing component (seeking alpha) and a business component (seeking assets). Outperformance is one goal, scale is another. Factors—like valuation, momentum, quality, and low volatility—have been largely applied by firms with the business in mind. In the asset management business, two variables matter: fees and assets. Smart Beta has risen to prominence alongside index funds and ETFs, and indexing has significantly reduced fees across the industry. With fees lower across the board, scale becomes a more important consideration for asset managers when deciding what strategies to offer the investing public. When fees fall, assets need to rise. For assets to rise across a business, the strategies offered need to be able to accommodate more invested money.

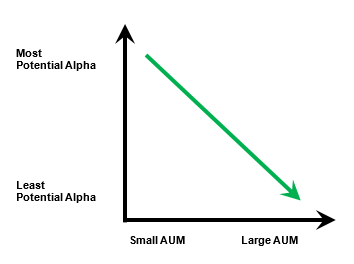

More assets may be good for the business, but it’s often bad for returns. As the level of assets under management rise, the investable universe of stocks shrinks, trading impact costs rise, and the potential for alpha erodes. In asset management, we find diseconomies of scale—as mutual funds and hedge funds get larger, their performance tends to suffer.

Of course, fees matter a great deal, and the nearly free access to broad market index funds is a wonderful thing. But management fees are one thing, and key factors like valuation another. I would rather pay 0.75% for an S&P 500 index fund trading at 12 times normalized earnings than 0.05% for the same market trading at 25 times earnings, which it does as of April 2016. To have a large advantage versus the market—on factors like valuation or shareholder yield—you must build strategies with an emphasis on alpha and the consistency of alpha above all else.

To achieve what we call factor alpha, we believe that investors should use multiple, unique factors to build a more concentrated portfolio of stocks (as few as 50) with the best possible factor profiles. That means not owning wide swaths of the market. Relative to Smart Beta, a focus on factor alpha allows for better returns and significantly better factor advantages. In the rest of this post, I explore the dangers of scale and widespread adoption of any strategy and offer an alternative solution for using factors in the investment process.

Watch Scale Eat Returns

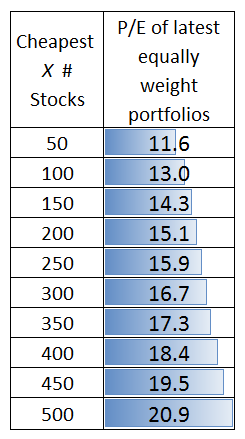

The difference between any portfolio and the market is determined by 1) what stocks you own and 2) how you weight those stocks in a portfolio. To show the impact that these two variables have, we start with the constituents of the S&P 500 and create different portfolios based on a single factor that has worked well historically—valuation—to demonstrate the effect of moving further and further away from the index. We use this basic example not to recommend this as a strategy but rather to show the effects of both concentration and weighting scheme.

What we tested

I show three versions of this strategy.

The first sorts all stocks in the S&P 500 on each date by valuation and portfolios of between 50-500 stocks (so the 50 stock version would be the 50 cheapest stocks on that date, and so on). Positions are equally-weighted (e.g. 2% each in the 50 stock portfolio or 1% each in the 100 stock portfolio).

The second takes the same portfolios with the same stocks (between 50-500 holdings) but weights the positions according to market cap. This method can create very top heavy weightings in the more concentrated portfolios (e.g. IBM at 11.3% of the most recent 50-stock portfolio).

The third forms the portfolios using a market-cap adjusted valuation factor, which multiplies a stock’s weight in the index by its relative valuation. This cap-adjusted value factor rewards companies that are big and cheap and penalizes companies that are small and expensive. Again we use the factor to build portfolios between 50-100 stocks. This is the most scaleable version of the value strategy whose holdings look a lot like major value indexes.

What we found

Here are the results, highlighting two key variables. First, the average forward 1-year excess returns versus the S&P 500 and second the average active share (i.e. the percent of the portfolio that is different from the S&P 500; higher means less overlap with the index).

What we learned

From this simple exercise, we learn the following:

Concentration and equal weighting lead to portfolios which have better average excess returns and higher active shares.

The equal weighted portfolios outperform cap-weighted and cap-adjusted value portfolios by an average of 1.8% and 2.0% per year, respectively—a wide margin in the U.S. large cap market.

More concentrated portfolios have a much better valuation edge: stocks in the portfolio have much cheaper average value percentile scores.

Why this happens

Value (measured by something like a price-to-earnings ratio) is just another way of saying “market outlook.” A low relative valuation for IBM means that the market is pessimistic—relative to other stocks—about IBM’s future. We believe that value works over time because markets become too pessimistic about these stocks. Pessimism is good—and the lower the P/E, the more pessimistic the market.

Now, notice the trend in the price-to-earnings ratios (figure to the right) for the different portfolios today (the equally weighted versions). If market pessimism (low P/E) signals an opportunity, then the opportunity clearly grows as the portfolio gets more and more different from the S&P 500.

It helps to see what these simple value portfolios would hold today. Here are the top ten holdings for each of the 50-stock versions of our value strategy, along with each portfolio’s weighted average market cap. You can see, as you move left to right, that the top ten look more and more like the overall market, because the market caps get bigger and bigger.

Size vs. Edge

If you are a value investor, or a quality investor, or a yield investor, a key question is: how big is your edge versus the overall market? If you believe in price-to-book, your goal should be to achieve significant portfolio discounts versus the market on that measure.

But the most notable difference across the above portfolios is their size. When market cap is used as a variable when building a portfolio, it obscures any other edge that exists. Exxon Mobile has a price-to-book of 1.95x but is a huge company so has a weight of 3.6% in the Russell 1000 Value index. Seadrill—a maligned energy stock—has a price to book of 0.18x. So it is much “cheaper” than Exxon, but it’s only a $1.6B company, so its weight in the index is 0.01%, which may as well be zero.

If Exxon went up 40%, it would push the overall index up 1.44%. If Seadrill went up 40%, it would push the index up 0.004%. Seadrill would have to go up 14,400% to have the same impact as Exxon going up 40%.

For the Russell 1000 Value, Exxon is the far more important stock. But if you cared more about value than size, then the weights would be very different. Exxon is the biggest stock, but it’s only in the 50th percentile when sorted by price-to-book instead of by market cap. Seadrill is in the cheapest percentile.

From the perspective of an active investor, this is very odd because cheapness should matter much more than market cap when deciding a stock’s weight in a portfolio.

Different Means More Potential

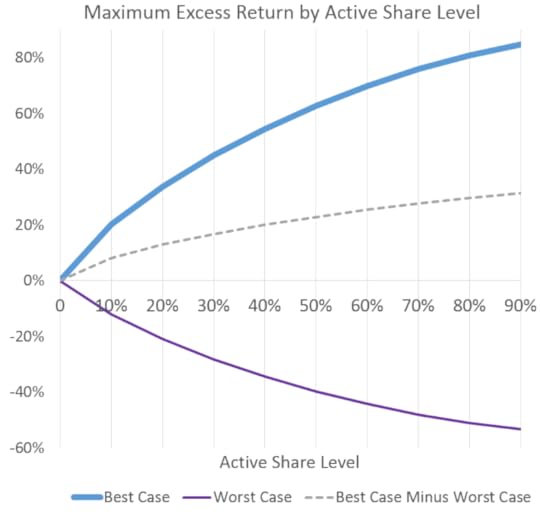

If you weight stocks based on market cap—like the Russell 1000 Value does—then your portfolio will always have a lot of overlap with the market (a low active share). With a lot of overlap, there is only so much alpha you can earn.

Active share—our preferred measure of how different a portfolio is from its benchmark—is not a predictor of future performance, but it is a good indicator of any strategy’s potential alpha. The chart to the right shows why. On every date through history (1962-2015), we bestow ourselves with perfect foresight so that we can build portfolios that will achieve the highest possible 1-year forward excess return at each level of active share between 0% and 90%. We use only stocks in the S&P 500 itself and allow a maximum position size of 5% in the portfolios, to avoid piling into just a few of the best-performing stocks. This chart shows the maximum possible excess return (average of all historical periods) vs. the S&P 500 by active share level. This potential cuts both ways, so we also show the worst case scenarios by active share level. At any given level of active share, the “potential” excess return skews more to the positive (dotted-line).

More active portfolios have more potential for excess than less active portfolios. No one has perfect foresight, so nobody achieves alpha like this with any consistency. But these “best case scenarios” show the power of being different.

Factors like value have been a good way of putting yourself on the positive side of this potential curve above. Indeed, we saw the same thing with our different value portfolios: the more concentrated portfolios (higher active share), the better the average results. What is amazing is that in the early 1980’s, well over half of mutual funds had an active share above 80%, but as of 2009, only 20% or so of funds were this active. Large, scaled up institutions now control a majority of the market. In 1950, between 7-8% of the market was managed by large institutions. In 2010, that number was 67%.

Costs Matter

So far we’ve discussed paper returns only. We saw that—gross of costs—returns to the S&P 500 value strategy get worse as the number of stocks grows. Now let’s look at the same issue net of trading costs. Simple trading commissions are a real cost, but our focus here is on market impact costs, which matter more for big asset managers. Once you start getting too big (trading billions of dollars), your trading moves the price of the names you are buying and selling—you pay a higher price when buying and get a lower price when selling than if you were an individual trading a $100,000 account. Market impact is a cost that doesn’t get enough attention, because end investors can’t see it, and asset managers don’t report it. The table below shows how annualized market impact costs grow with assets (these are estimates, skilled traders can beat these estimates by a little or a lot).

To show the cost drag, we expand our universe to the Russell 3000, which includes small- and mid-cap stocks where market impact is even more important. We again build portfolios based on valuation that have between 50 and 3000 stocks, and assets under management between $50MM and $50B. We rebalance these portfolios on a rolling annual basis, so the holding period is at least one year for each position. It is important to note that the more concentrated equal-weight portfolios have more exposure to smaller-cap stocks, so the impact numbers are higher than if we performed the same analysis on the S&P 500 universe.

The cost estimates reported in the table are based on 5 years of simulated trading in the actual value portfolios between 2010 and 2015. These are based on actual market conditions, not hypotheticals. We’ve highlighted the point at which impact (annualized) crosses 1%. For cap-weighted portfolios, you reach $30 billion in the most concentrated portfolio before crossing 1% impact costs. But in the equal weighted portfolios, you reach the 1% threshold much more quickly in the more concentrated portfolios. We’ve already seen that equal weighting and concentration have delivered better results. This table proves that the more concentrated value portfolios cannot accommodate the kind of scale that large asset managers are after. If you are seeking alpha, you’d equal weight and you’d be willing to have fewer names in the portfolio. If you were seeking assets, you’d do what the industry has done: build broader smart beta indexes that focus on the large cap market or weight based on market cap.

Back to Smart Beta

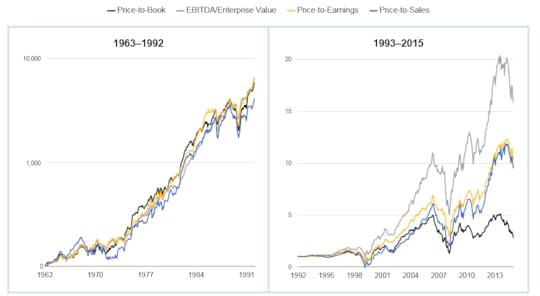

We’ve seen that scale and excess return are mortal enemies. As Buffett said in his 1994 letter to shareholders, in which he warned of lower future growth rates for Berkshire Hathaway, “a fat wallet…is the enemy of superior investment results.” Price-to-book was arguably the first smart beta factor and has likely suffered from its own popularity as a measure of value. Hundreds of billions are invested based on price-to-book, but we’ve watched it deteriorate since 1993, when Fama and French first held it out as the defining value factor:

Science fiction master William Gibson wrote in his book Pattern Recognition that “commodification will soon follow identification.” In another passage, also from Pattern Recognition, Gibson is talking about clothes, but he could be talking about Smart Beta ETFs:

This stuff is simulacra of simulacra of simulacra. A diluted tincture of Ralph Lauren, who had himself diluted the glory days of Brooks Brothers, who themselves had stepped on the product of Jermyn Street and Savile Row, flavoring their ready-to-wear with liberal lashings of polo knit and regimental stripes. But Tommy surely is the null point, the black hole. There must be some Tommy Hilfiger event horizon, beyond which it is impossible to be more derivative, more removed from the source, more devoid of soul.

Smart Beta is the commodification of the most common historically proven factors. By definition, a commodity must be widely available. In asset management, that means it must be able to accommodate lots of invested money. We haven’t seen many active strategies with hundreds of billions of dollars behind them consistently beat a simple market index. Even Warren Buffett has been slowed—though not stopped–by scale.

Factor investing has huge potential benefits. Factor investing strategies tend to be cheaper than traditional active management. Properly managed, factor-investing strategies are also very disciplined. But, if a given strategy can accommodate $100B in assets, you may want to look elsewhere. Always avoid saturated strategies. For most of history, the factors behind Smart Beta strategies weren’t big targets. Now they are. Beware of popularity, beware scalability, and beware newly accepted “measures” of a strategy or idea. Too often, popular measures become targets and then lose their meaning and their edge.

Factor Alpha

The philosophical roots of the factor-alpha approach are notably different than those of Smart Beta.

First, what you don’t own matters. If Apple or Microsoft don’t look attractive, we believe you should own none of either in your portfolio. We start with a weight of zero in every stock, not with the market weight. Stocks are guilty until proven innocent. This naturally leads to higher active share and a portfolio with a greater overall potential for alpha.

Second, alpha comes from the relative advantage a portfolio has versus the market measured across key factors. Greater spreads—like bigger discounts or higher shareholder yields—have led to better excess returns through time. Portfolios should focus on just the stocks with the best factor profiles. To achieve these big factor advantages, portfolios should be more concentrated than has become typical for smart beta strategies.

Sample the most popular Smart Beta ETFs and you’ll find the opposite: high overlap with the S&P 500 or Russell 1000. USMV, the popular “low volatility” ETF has an active share of 46% to the S&P 500. That means it has more in common with the S&P 500 than does an equal-weighted version of the S&P 500 with an active share around 50%. Strategies designed for factor alpha often have active shares higher than 80%. They are still well diversified, but more diversification is not always better. In the case of factor investing, diversification often means diluted factor exposures. If factors work best at their extremes, then diversification means moving away from your edge and towards the market return.

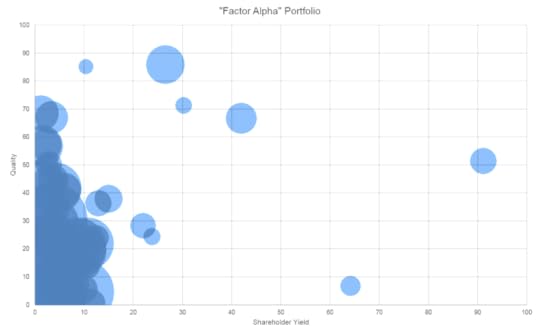

Often, a picture tells the story better than words can. Below, we show the unmistakable difference between popular smart beta approaches vs. the factor alpha approach. We recreate the spirit of a Morningstar style box, but instead of using market cap and value vs. growth as the dimensions on the chart, we instead use the factors that we’ve found to be most predictive of future excess return: shareholder yield and quality (where quality is a combination of valuation, earnings growth, earnings quality, and financial strength).

The goal is to show where the different portfolios plot on the yield and quality continuum. A portfolio in the lower left would have the strongest relative readings on both quality and yield. The central dot in each circle represents the average current shareholder yield and quality readings for the portfolio, and the surrounding circle encompasses 75% of the portfolio’s weight. The trend is clear. As you move from the broad Russell 1000 (in grey), to the Russell 1000 Value (in green), to the biggest “fundamental index” smart beta approach (in orange), what you see is a tilt towards factors, but with very broad exposure. The factor alpha approach is entirely different, by design: a much better and tighter exposure to the key factors.

We can get even more granular a visualization: by plotting the position (good to bad on quality, vertical axis, and shareholder yield, horizontal axis) and portfolio weight (size of the circle) of every stock in a variety of popular ETF smart beta strategies: S&P 500 (SPY), Russell 1000 Value (IWD), Fundamental Index (PRF), and Minimum Volatility (USMV). Compare these with the final chart: the factor-alpha approach, and you can see the clear difference in portfolio construction and position in the shareholder yield and quality themes.

There are some outliers in the factor-alpha approach: these are positions whose factors profiles are deteriorating. The one of the far right, for example, is XL group, which had a strong shareholder yield until it issued a big chunk of shares for an acquisition last year. As the strategy rebalances, these positions will be sold down in favor of stocks in the lower left corner.

Wonky calculation note: these all use different starting universes, so percentiles are calculated on the broadest set of investable U.S. stocks, about 2,500 or so. This is why you see a slight skew towards higher shareholder yield everywhere in these charts: these are all large cap-ish strategies which have higher dividend and buyback yields than smaller cap companies which are included when calculating the percentages but often not shown on the chart.

Into the Future

Indexes and Smart Beta factors are affected and changed by asset flows into strategies which target those indexes. Hundreds of billions of dollars flowed into low price-to-book strategies, and price-to-book has suffered as a result. Fund flows affect everything.

Mark Twain said, “I was seldom able to see an opportunity until it had ceased to be one.” We often become aware of market strategies only after they’ve been identified, commodified, and scaled away. Smart Beta factors are a commodity. There is an ETF for everything, from value, to obesity, to put writing. When making an investment, consider the motivations of the manager or sponsor company—are they oriented toward gathering assets or earning alpha over time? If you believe in value, is a market-cap weighted value portfolio–where, for example, Exxon is your top holding despite being in the 50th percentile by price-to-book– really the best expression of that factor? Factor alpha has won for investors in the past.

Nothing is perfect. Other quants will disagree, citing the fact that fewer positions likely means higher tracking error, lower information ratios, and so on. I believe that as asset managers continue to put out hundreds of smart beta strategies, that a more differentiated approach will continue to win in the future. My suggestion is: if you believe in factors enough that you are willing to move away from the simple, cheap, market portfolio, don’t do it via tilt. Do it in a way that gains true exposure to factors. A neat parting idea: consider blending a 5-basis point S&P 500 or Russell 1000 fund with a truly deep value portfolio (or some other factor). The combination might get you similar overall factor exposures as a smart beta option, but at a cheaper price.

Always always always, ask yourself: is this strategy about alpha, or about assets?

Does Fund Size Erode Mutual Fund Performance? The Role of Liquidity and Organization By JOSEPH CHEN, HARRISON HONG, MING HUANG, AND JEFFREY D. KUBIK*

How AUM Growth Inhibits Performance By Andrea Gentilini

Prior to 1990, we use the top 500 stocks by market cap to represent the S&P 500 rather than its actual constituents which are not available.

Value defined as sales/price, earnings/price, ebitda/ev, free cash flow/ev, and shareholder yield, weighted equally

valuation percentile * weight in the S&P 500, think of it like a “contribution to total cheapness”

Sorted by value ranking for equal weighted and cap-adjusted value portfolios

The potential works both ways: more active portfolios also have more potential for underperformance.

https://www.sec.gov/News/Speech/Detai...

ITG TCI analysis

Shareholder yield = dividend yield + net buyback yield (percent of shares outstanding repurchased, net of any issuance, over the past 1-year period.

There are, or course, issues beyond flows that affect factor performance