Rick Wayne's Blog, page 70

September 12, 2018

The Demented Comic Art of Stéphane Rosse (NSFW)

Full of penis noses and vagina heads and casting Picasso as a Victorian detective, Stéphane Rosse’s single-panel illustrations make Twin Peaks look like a children’s story.

September 10, 2018

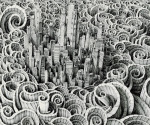

The hyper-detailed imaginary cities of Ben Sack

Benjamin Sack makes amazing, large-scale pen and pencil drawings of fantastic cities, both real and imaginary.

[image error]

Sadly, these imagines don’t do justice to the intricate detail of the works, which really need to be appreciated up close for their skill and whimsy. Thankfully, the artist has a number of close-up shots on his Tumblr page.

September 8, 2018

(Fiction) The casting of darkness

The train rocked as it slowed and the picture in my hand rocked with it. My finger traced the single splatter of blood that stretched across the scattered feathers, many of which seemed to have been cut obliquely by a swipe from something very sharp. The train lurched hard and I dropped the photo. I scanned the compartment as I bent to pick it up. People were rising from their seats and gathering their belongings as the conductor announced over the speakers that we would soon be arriving at Penn Station. No one seemed to be paying attention to me. I folded the photo and put it back in my pocket.

It felt strange being back in New York. It had only been a few months, but already it seemed like someone else’s city—a feeling that grew as I left the relative safety of the train car and stepped onto the bustling platform. I felt like I was visiting someplace new. I went right for the ladies’ room, where I had to wait in line. Construction in some distant part of the station had limited the number of womens’ toilets to a dangerous minimum. I spent the time casually scanning the crowd outside the short hall to the restrooms. I had left the relative safety of Saycroft House early that morning over Martin’s strenuous objections. It was too dangerous, he suggested. Word was coming in from all quarters about freak disappearances, freak reappearances, and numerous other odd and foreboding occurrences. I agreed that it was dangerous but noted I simply had no choice. Our enemies were multiplying, and I could no longer wait for Etude to make contact.

As I shuffled forward in line, the drawstring straps of my little cloth backpack bit into my shoulders and I shifted the heavy contents as I scanned the crowd nonchalantly. I had expected Annie to join her husband’s protest, but she knew better than to argue. She simply went through the attic to the other place and came back with the flat lead box that I had asked her to keep there, away from the prying eyes of the living world. Seeing there was no argument to be won, Martin joined her. He appeared in my door as I was packing and handed me a loaded WWII-era revolver. Out of habit, I immediately checked the cylinder. All six cartridges were silver-tipped.

“Would I could go with you,” he said with more than an ounce of regret in his voice.

By then, I had gotten the distinct sense that Martin Hightower’s fate was tied to that house and that he could no more step from it than any of us could step from the earth.

A bathroom stall opened and I went inside and locked the door behind me. The previous occupant had thankfully squirted some perfume in the air to mask the smell. I set my bag on the seat cover and took out the lead case. I ran a finger over the necromantic patterns etched into its surface. Annie had designed the box herself, and Martin had carved it in his shop to her exact instructions. It was made to repel both the scrying eyes of the living and the scratchings of the undead.

My first stop would be The Barrows, I had decided, partly because it was the nearest thing in our community to neutral ground, but mostly because it was the nearest of my destinations to Penn Station. Anson could at least give me the lay of the city. However, because of its importance, I was certain The Barrows, of all places, would be watched, which meant simply walking through the front door was not an option. But then, I had experience avoiding pursuers.

I unfastened the latch and lifted the lid of the box. The object inside was exactly as I remembered. It had been preserved in the basement of the inverted shadow of Saycroft House, and it was neither dusty nor tarnished. The amulet itself was typical, with a dark blue crystal in the center of a black disk carved in writhing forms that could’ve been snakes or eels or worms. It hung not from a chain but from the tip of a large, teardrop-shaped collar made of interlocking brass in a design similar to a Celtic flourish. The wide, intricate collar was hinged at the joints of the design such that it could only fold down, not up or to the right or left. It draped heavy over the shoulders where the points underneath, like dull spokes, pressed hard through clothing to the skin. No magician had ever confirmed it for me—I dared tell no one I had it—but I suspected the collar collected the pain it caused and directed it to the amulet and so powered the spell embedded in the tiny etchings in the dark crystal, which you could see if you raised it very close to your eye.

It was an amulet of Zaragoza, the very one I had stolen from The Handred Keep. As with all of its type, it cast its wearer in darkness. As such, it was key to my escape from that place. I lifted the heavy metal collar and draped it over me. The discomfort was immediate, and I tried shifting my shoulders, which helped not at all. I shut the box and stuffed it in the bag with Martin’s revolver and the rest of my belongings and left. I stored the box and a change of clothes in a locker. Then I walked to the center of the busy station and stood. The amulet was nearly 70 years old, and I wasn’t entirely sure it still worked. Nor did I dare test it on Annie and Martin, for their own sakes. The less they knew, the better. So I stood in the middle of the busy crowd and waited—waited for someone to come. No one did. No one approached me. No one even looked at me. No one bumped into me either. It was as if I occupied a dead space in the world. I stuck out my hand and a woman walked around it without raising her eyes from her phone.

There’s a medical condition I read about once called hemispheric neglect. It’s caused by a certain kind of brain damage. People who have it are simply unaware of the entire right or left half of their visual fields. Their eyes work correctly. So do their nerves. But interior damage to the brain means that it’s unable to do anything with the information it receives. If you ask these people to draw a clock or a house, they’ll draw two-thirds of one, or thereabouts, and stop, thinking they’d done the whole thing. Yet, the neglected half of the world is actually not fully absent from their mind. Their brain still receives information from it, just not consciously. For example, if you raise a picture of an elephant on their neglected side and ask them what they see, they’ll register nothing and report that. But if you then ask them to think of an animal, they’ll say elephant, and if you ask them why, they’ll completely confabulate a reason.

I remembered that article—and may even have saved it—because it seemed to me that’s exactly what being cast in darkness was like. You are not invisible. Light does not pass through you. Rather, you are obfuscated, neglected, unnoticed by the conscious mind. As with most magic, this works better on some people than others. The amulet works on everyone, but only to the degree the wearer doesn’t arouse anyone’s preconscious fight or flight response. That is, if you move suddenly, make a loud noise, or attack, others will become aware of you, although how clearly and for how long depends on their sensitivity and the circumstances. To put it another way, someone cast in darkness could be in the room with you right now, reading this over your shoulder, and as long as they moved casually and quietly, you’d be completely unaware of their presence, even if you had suspicions.

With one exception. Since Zaragoza distrusted his subordinates as much as his enemies, he designed his amulets such that two wearers in proximity would always be obliquely aware of one another and always in inverse proportion to their attention. That is, it was impossible for someone cast in darkness to sneak up on someone else cast in darkness, even though neither would ever be fully revealed. The more one concentrated on noises and signs, the harder such things were to note. You could only ever know that someone was there, not exactly where or who. It was, I suspect, Zaragoza’s means of avoiding assassination at the hands of his own invention without diminishing its efficacy in the war.

As you might expect, casting darkness became the subject of intense study at The Winter Bureau, but without an amulet of their own and without the ability to cast darkness themselves, their efforts were largely confined to the theoretical, which left ample gaps for pure speculation. Someone supposed, for example, that if you spun suddenly in front of a mirror, you could catch a glimpse of a shrouded person or object in the reflection. Innumerable such tricks were passed from agent to agent during the war, like old wives tales. I can’t remember most of them, nor do I expect any of them were true. Looking glasses and scrying orbs all succumbed equally to the effect. There was only one thing, in fact, that seemed genuinely able to discern objects cast in darkness: cats’ eyes, perhaps because they were ever half in darkness themselves. But then, without an amulet for training, it was almost impossible to teach cats that they could see what others could not, and their use was limited.

So it was, I passed through the station unnoticed, like a living ghost, and exited to the street. The spokes of the collar pressed through my clothes to my skin, which made keeping a brisk pace somewhat painful. I couldn’t imagine trying to run while wearing an amulet of Zaragoza. It was made, it seemed, for skulking, and I was giddy at the prospect of removing the painful collar once I was safely inside The Barrows. I turned the corner onto the little street of closed shops, under which were the remnants of the old goblin market, although Anson was, as far as I knew, the only goblin left. But as soon as I arrived, my heart sank. The front door of The Barrows had been ripped away. The subterranean interior was dark, but I could see clear enough that everything inside was twisted and broken. Everything. The shop itself had been wrung like a wet rag. The cracked cabinets and hardwood slats turned over each other in a spiral, as if the ends of the room had been twisted in opposite directions by giant hands. There were splinters and broken glass everywhere.

I stepped in cautiously. Walking the floor was a bit like navigating a rocky beach. Several of the splintered planks and shelf boards were turned up like spikes, and I had to step carefully to avoid a fall. After several tentative steps, my foot fell on something hard and flat and unforgiving and I stopped suddenly and nearly lost my balance in the dim light, as one does sometimes when trying to find the bathroom in the middle of the night. I reached instinctively into my pocket for my phone so I could use it as a flashlight, but then I remembered I didn’t have one. I cursed softly and knelt to examine the object on which I’d stepped. The movement caused the collar to shift slightly, and I grimaced. The object was hard and flat—cast iron, it seemed—and cool to the touch. I ran my hand around it and found square edges. I tried to lift it, but it was heavy and I had to shift my stance before I could try again. With a grunt, I heaved it up such that the faint light from the open door behind me caught the letters.

THE BARROWS

Est. 1676 (A.D.)

REINTERRED 1848

at this location with

Generous Donations from

THE ROEBLING FAMILY

& H. Morton Ramsay & Sons

& Eleanor Peas

I knew one of the sons of H. Morton Ramsay—a grandson, actually. He was H. Morton Ramsay III, my mysterious Mr. H, who sent me to Everthorn after I impolitely refused his offer to become a spy. The Winter Bureau hadn’t yet been founded in those days and each of The Masters maintained their own, often competing, networks of informants. Mr. H worked for Master Thrangely, who was a prodigious hunter and who was said to have tasted the flesh of every animal that walked, swam, or flew. His offices in Cairo were fully adorned with the taxidermied remnants of his numerous hunting campaigns, which he could summon to life when needed. His death at the hands of one of them remains one of the great unsolved mysteries, for when his body was discovered torn to shreds, nothing else in his sanctum was out of place.

I frowned and looked around the shop. The Barrows had been my first stop in America, where I arrived carrying HPB’s manuscript. It had been a fixture of my time there, at once a landmark and a resource and a meeting place. Hank and I had attended its formal re-dedication in 1931. And yet, there it was strangled to death around me. That’s what they’d done. They’d strangled knowledge, wrung the place dry of it. I dropped the heavy plaque, which hit the ground with a loud thud and sent several shards and splinters into the air. I realized my mistake immediately. As soon as the plaque had left my hands, it had been freed from the spell of darkness, and whatever noise it made could be heard. I cursed again, this time in pure frustration—not so much for what I’d done but for what it represented. Cautious habits that had once been second nature to me were now distant and alien. I didn’t have time to relearn them.

There was a slight clink behind me then and I turned. It was still dark, but it certainly seemed as if someone had knocked loose a piece of glass. I scanned the floor for something I could use as a weapon, which is when I noticed the blood near the corner. Someone had been impaled on one of the ruptured floorboards and their body hauled away, or so it seemed from the streaks. I heard a step to one side, as if I had just been passed by. I grabbed a shard of glass and listened. And listened. But all I heard was the rush of my own heart in my ears. I was obliquely aware someone or something was in the room with me, but I couldn’t detect a single trace, which meant that they were shrouded as well. I was certain they were aware of me, and that they stepped just as lightly as I did in an attempt not to be detected. That’s how it went for some time. The interloper and I circled each other like submarines at depth, both listening for the other while trying not to make a sound, terrified we would step into the point of a knife. Since I dared not remove my bag, where I stowed Martin’s gun, my only weapon was a shard of glass, sharp only at the tip, and I began to contemplate the many ways in which a fight could go badly, not least because it was dark and my adversary and I were standing in a field of foot-long splinters. Any sudden loss of balance would be potentially fatal. I would return, of course, but if I died at the hands of the enemy, I would almost certainly wake to captivity and torture.

I withdrew as quickly as I could out the door to the street. I ran at first but stopped after three strides due to the pain, and walked as briskly as I was able. It was light out, but it wasn’t until I reached traffic and safety that I noticed the dark smudges on my hands. They were black and powdery, like ash. They were also faint and irregular, suggesting they hadn’t come from a coating of dust on the cast iron plaque. It seemed like they had been transferred, that perhaps someone with dirty feet had stepped on the plaque on the ground and its ridges had caught the soot. I wiped them on my slacks and didn’t think anything else about it until I was crossing the river on the subway, still wearing the amulet, despite that the longer I wore it, the more it pinched my skin, which I felt flush and grow warm with the pain. I grimaced and shifted my shoulders and tried to adjust the spokes of the heavy collar, which is when I caught a whiff of my hands. The scent was faint but unmistakable. I sniffed and smelled burnt sulfur: brimstone. But it was very weak. Fresh brimstone is potent, not unlike the smell of rotten eggs charring over a spit, which is why everyone mentions it when it appears. It’s almost impossible not to. The scent on my hands, however, was very faint, which meant the brimstone was very old.

The train had exited the tunnel and was riding elevated tracks. The light was ambient and I could see the skyline of Manhattan in the distance, not unlike the view from the sanctum before it burned. I examined my hands and sniffed again, and that’s when downtown erupted suddenly as if a volcano had opened under the financial district. I looked up to see a dozen skyscrapers obliterated at once. The shockwave traveled the length of the island. You could follow it with your eyes as it blew windows from buildings in every direction. The train rocked then and kept moving, as if it had felt the psychic shade of the blast. There were few clouds and no wind that day, so the plume of smoke was as wide as the island and reached straight up to the sky. I watched ash and debris fly up and out as if in slow motion. A hole had opened underneath, and the city began to fall in, as if consumed by a massive sinkhole, thirty miles wide. Building after building tumbled and fell, one after the other, with trucks and cars and bicycles from the street. The East River and Hudson disappeared as their bedrocks crumbled, dragging the bridges down with them. The ocean itself began to drain into the hole, from which an army emerged, a black army on flapping wings—horned devils, some bearing burning hellions on their backs. They poured forth from the center of the hole in a streaming mass, like a torrent of black water. And behind them . . . something worse. The ground shook—

The vision stopped. Downtown was as it had been. I looked at my fellow passengers staring at their phones and reading books and chatting softly to each other. My hands were shaking, but everyone around me was oblivious.

September 6, 2018

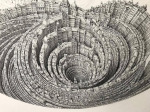

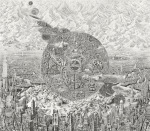

Remedios Varo: The Sorceress Who Left Too Soon

Born María de los Remedios Alicia Rodriga Varo y Uranga in Anglès, in a small town in the province of Girona, north of Spain in 1908, she helped her mother get over the death of another daughter — hence the name.

Varo’s father, Rodrigo Varo y Zajalvo, was a hydraulic engineer, and the family traveled the Iberian Peninsula and into North Africa for work. To keep Remedios busy during these long trips, her father had her copy the technical drawings of his work with their straight lines, radii, and perspectives, which she reproduced faithfully. He encouraged independent thought and supplemented her education with science and adventure books, notably the novels of Alexandre Dumas, Jules Verne, and Edgar Allan Poe. As she grew older, he provided her with text on mysticism and philosophy.

[image error]

After receiving a formal education in art in Spain, Varo fled to France to escape the Spanish Civil War and then to Mexico City to escape the Nazis. Her brother, Luis, died fighting for Franco.

Varo often painted images of women in confined spaces, achieving a sense of isolation. Later in her career, her characters developed into her emblematic androgynous figures with heart-shaped faces, large almond eyes, and the aquiline noses that represent her own features. Varo often depicted herself through these key features in her paintings, regardless of the figure’s gender. Some of Varo’s art clearly elevated women, but it was not necessarily her intention to address problems in gender inequality.

This is “Woman after a visit to the psychoanalyst:”

[image error]

Varo was influenced by styles as diverse as those of Francisco Goya, El Greco, Picasso, and Braque. She considered surrealism as an “expressive resting place within the limits of Cubism, and as a way of communicating the incommunicable”. Even though Varo was critical of her childhood religion, Catholicism, her work was influenced by religion. She differed from other Surrealists because of her constant use of religion in her work.

She also turned to a wide range of mystic and hermetic traditions, both Western and non-Western for influence. She was very connected to nature and believed that there was strong relation between the plant, human, animal, and mechanical world. She turned with equal interest to the ideas of Carl Jung as to the theories of Helena Blavatsky, Meister Eckhart, and the Sufis, and was as fascinated with the legend of the Holy Grail as with sacred geometry, witchcraft, alchemy and the I Ching. The books Illustrated Anthology of Sorcery, Magic and Alchemy by Grillot de Givry and The History of Magic and the Occult by Kurt Seligmann were highly valued in her circle. She saw in each of these an avenue to self-knowledge and the transformation of consciousness.

[image error]

She was also greatly influenced by her childhood journeys. She often depicted out of the ordinary vehicles in mystifying lands. These works echo her family travels in her childhood.

In 1963, at the age of 54, Varo died of a heart attack in Mexico City, prompting the surrealist poet Andre Breton, one of the founders of the movement, to comment that she was “the sorceress who left too soon.” (adapted from Wikipedia)

Click below for a larger image.

September 1, 2018

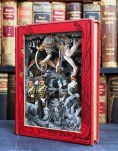

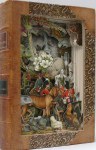

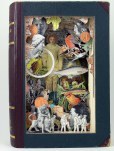

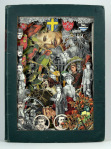

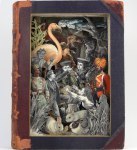

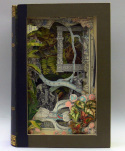

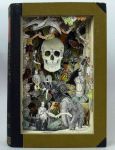

The amazing antiquarian book sculpture of Alexander Korzer-Robinson

“I make book sculptures by working through a book, page by page, cutting around some of the illustrations while removing others. In this way, I build my composition using only the images found in the book.

Through my work in the tradition of collage, I am pursuing the very personal obsession of creating narrative scenarios in small format. Using antiquarian books makes the work at the same time an exploration and a deconstruction of nostalgia. We create our own past from fragments of reality in a process that combines the willful aspects of remembering and forgetting with the coincidental and unconscious. On a general level, I aim to illustrate this process that forms our inner landscape.”

[image error]

“By using pre-existing media as a starting point, certain boundaries are set by the material, which I aim to transform through my process. Thus, an encyclopedia can become a window into an alternate world, much like lived reality becomes its alternate in remembered experience. These books, having been stripped of their utilitarian value by the passage of time, regain new purpose. They are no longer tools to learn about the world, but rather a means to gain insight about oneself.”

Click on an image below to enlarge the detail.

You can find the artist on his website.

August 29, 2018

Women with swords and sensible armor

Alexandre Chaudet

Dirty Robot

Basha Beliaev

Alexandra Dvornikova

Team Couscous

Sarah Kipin

JiHun Lee

Eve Venture

Serge Birault

Jakub Rebelka

Philipp Kruse

Choong Yeol Lee

Alexander Beardin

Sam Bosma

August 27, 2018

The only original American art

It’s been said that blues, jazz, and their progeny, which includes rock n roll and hip hop, are the only indigenous American art forms — that is, ones that did not exist earlier somewhere else.

This is not a slight to the first nations. Native peoples of the southwest, notably the Navajo, are famous for a highly distinctive and original style of sandpainting, for example, but sandpainting (and other forms of dry painting) have been practiced for literally tens of thousands of years, going back some 30,000 years in Australia and perhaps even earlier in parts of Africa.

Whether native Americans invented it themselves or brought it with them from somewhere else isn’t really the point. The art existed earlier, as did oil painting, sculpture, classical music, wood carving, pottery, dance, poetry, prose, printing, fashion, pyrotechnics, glass-blowing, jewelry-making, architecture, cooking, theater, film, photography, and of course music.

It’s always tricky to say something is an original (or the first or the best of its category or whatever). As soon as you do, someone comes along to say “Well actually…” Categories of art are overlapping and nonexclusive. We can always go up or down a level or parse things a different way to get a different “first.”

Take music. It’s been around forever. It certainly predates our Homo sapiens. Whether you count nonhuman forms, such as bird or whale song, as music will depend on your criteria. Personally, I don’t see a significant difference between a male humpback courting females from afar with vocalization he composed himself and a rock star gyrating in front of fans on stage, or a troubadour strumming a lyre for a lady, but if you do, more power to you.

That’s not to say what a whale is doing is creatively identical to what a classical composer does; simply that the human composer didn’t invent composing, and humans didn’t invent music, only more complex styles of it.

I would argue that the blues inaugurated a new form in that archaic medium in the same sense that the invention of oil-based paint inaugurated a new form in that medium, which goes back at least to our caveman days when early hominins applied color pigment to walls. As such, the blues (and its diverse and explosive progeny) is the only art form in any medium to originate in America.

I am not the originator of this idea, by the way, but it does seem correct to me. It all turns, of course, on how you define “form,” which really only becomes clear in arrears. That is, if the blues appeared and flourished and waned and nothing else was done with it and what was played on the radio today was more like, say, old-timey ballads or operatic aria, I’m not sure we would recognize it as a distinct form versus simply an American brand of the kind of folk music that’s been sung the world over for centuries. As with life, species of art emerge with growth and differentiation.

One could argue — and some people do — that hip hop has emerged as its own separate form that way. If it continues to grow and diversify, I would say that’s true. But then, that could also be said of electronic music. Hip hop is only 40 years old. (Electronic music roughly ten years older.) We can’t predict its future any more than someone in 1940 could’ve predicted that rock n roll would emerge before the end of the decade and that it would supplant the wildly popular Big Band music of the day. We won’t really know until we see what happens.

For now, I’m still inclined to lump jazz, rock, and hip hop together as highly diverse and creative variants of a single something that started with…

For those who want to go back even earlier, well… it gets hard. The term”blues” doesn’t appear until 1905-8, and most of the classic recordings date from the 1920s, when the technology became cheap enough to be cost effective — not only to make but to distribute.

Prior to that, songs were passed orally and so varied significantly. There was no “official” version. When finally recorded, it was usually by white folks, who “dressed them up proper,” as indicated in this passage from The Encyclopedia of Great Popular Song Recordings about a popular late-19th-century African American tune known as “The Bully” (recording below):

W. C. Handy in his autobiography recalled it as being popular among black stevedores along the Mississippi River levees of St. Louis when he was stranded there for a time in 1893. The earliest known contemporary reference to the song was in a Kansas City black newspaper, the Leavenworth Herald, on December 8, 1894.

It would not be until eleven months after this reference that the song was published. There were actually six different copyrighted versions within a six-month period, the first on November 12, 1895, as Looking for A Bully, followed by three in January, 1896 (Dat New Bully, The New Bully, and De New Bully), and the final one in April again as The New Bully, all with different authors and various different lyrics or musical elements. The one that hit it big was Charles Trevathan‘s song, published on February 19, 1896, under the title Ma Irwin’s Bully Song. Based on the black Southern rural version transcribed by Howard W. Odum in 1908 and published three years later in the Journal of American Folklore. Muir believes the original black folk song used a straight 12-bar structure without the 16-measure chorus that is found in five of the six copyrighted treatments, including Irwin’s, and which was probably added for commercial purposes. He also views The Bully as “an early manifestation” of the Frankie & Johnny song family and cites a number of similarities in phrase structure and harmony between it and Stack-o-Lee Blues.

Another striking element is that the Charles Trevathan/May Irwin song, unlike any of the other “Bullies,” contains a couplet that would become very familiar in later years: “When you see me comin’, hist your windows high / When you see me goin’, hang your head and cry.” This “floating folk strain” had previously been collected by Gates Thomas in 1892 as the last verse of a black folk song: later it turned up in many songs. including a 1928 record by Henry “Ragtime Texas” Thomas, Texas Easy Street Blues, and the 1941 Count Basic/Jimmy Rushing hit Goin’ to Chicago Blues. Despite all this, The Bully is not a blues. G. Malcolm Laws (in Native American Balladry) classified it as a “Negro ballad” in the tradition of bad-man tales. J. W. Myers was perhaps the first artist to record it as The New Bully for Berliner on April 18, 1896.

Born Ada Campbell in Whitby, Ontario, Canada, on June 27, 1862, May Irwin performed at Tony Pastor’s theater in New York and became a Broadway star in the end-of-1893 show A Country Sport. She introduced The Bully, her trademark song, in the stage production The Widow Jones, which opened in February 1896. Irwin happened to be traveling by train when she saw sportswriter Trevathan entertaining passengers by singing an early, bawdy version of the number (which he had, in turn, learned from Pullman porters); she encouraged him to develop it into a full song. According to blues scholar Paul Oliver, Trevathan may have picked up the number from traveling black songsters; a St. Louis brothel singer known as Mama Lou is said to have performed it in the mid-1890s at Babe Connors’ club. Sigmund Spaeth makes the point that the song was “not as raggy as some of the other syncopated tunes of its day, but it had the spirit unfettered rhythm.” It’s lyrics, though simple, had “something of the belligerent mood” of that raw early American classic by minstrel man Dan Emmett, Old Dan Tucker.

The year 1896 was big for May Irwin for another reason, as she made history by repeating for the Edison motion picture cameras a kissing scene from Widow Jones

with her stage partner John C. Rice; The Kiss gained national renown and controversy, denounced as immoral by some religious leaders. May became particularly associated with ragtime-style numbers, most notably Ben Harney’s Mister Johnson, Turn Me Loose, which she unveiled in the December 1896 show Courted in Court. More than a decade after she first performed the song, May finally recorded The Bully at her debut session for Victor in 1907 (one of just six songs she would record). As was unfortunately the custom for “coon songs” of the time, it briefly uses language that would soon be unacceptable. (“I’m a Tennessee nigger…”)

The song below is obviously a trussed-up version made for the stage (i.e., for white people), which raises another important point. It would be decades before black folks would be able to record their own music — which is why I wanted you to hear this version. However, if you’re clever, you can hear the original poking through. Also, note the topical similarity to modern rap, which participates in the long history of its development.

This 2015 reproduction by the Cincinnati’s University Theater Orchestra is faithful to the original, meaning it includes the N-word and some other offensive language.

You were warned.

From a century later in 1997:

August 26, 2018

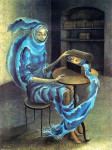

mrazь

So much going on in this work by Russian artist Maria Zolotukhina, right down to the arms and legs of the chair.

[image error]

August 23, 2018

The Radiant Solaria of “Ascending Storm”

Some legitimately awesome, highly detailed work by an artist known as “Ascending Storm,” are meant to invoke conscience and consciousness, which of course feels as wide as the sky despite that it all fits in the walls of your brain.

Click below or see more of the artist’s work here.

August 22, 2018

(Fiction) The Dunvluddich Furnace

Buried underneath a brick warehouse, and near another that had been into upscale shopping was an enormous spherical chamber made entirely of the heavy industrial steel of a bygone era. Two hemispherical sections were joined at their collars by giant bolts. Inside the five-story space was a structure of tanks and piping held aloft by four stone pillars which bore a vague resemblance to the legs and feet of an elephant, ten times normal size. The pillars disappeared into dark water at the bottom of the enormous tank while a cluster of four large pipes at the top bent at an L junction before running straight to the roof, where the steam they once carried fed an engine, long since absent.

I was inside the Dunvluddich Furnace, a kind of giant boiler. It was named for its creator, Abraham Dunvluddich, who was a Lithuanian American magician and scientist. He was sure there was a way to marry the “estranged sisters” as he called them—that is, science and magic—and spent his life in search of the means: perpetual energy machines, incandescent orbs of healing, crystal transmitters to communicate with the other side, or across the globe. His designs were legion. As far as I know, he could never get any of them to work.

After he moved to America, where heresy was weakly tolerated, Dunvluddich began designing and conducting his experiments, which I only heard about later, when the two of us shared a cell in Everthorn. His furnace was unusually large because it was built to contain the full heat of a hellion, which Abraham acquired from an Arab sheik in Tangiers. The beast tried to get out, of course, and in the process filled the furnace with hellfire and brimstone, heat from which boiled a huge quantity of water, producing steam. Alas, the engine could only run for short periods before its intakes were choked by the accumulating brimstone, which was porous and crumbly, like foam charcoal. All of Abraham’s experiments suffered such infirmities. No matter his effort, it seemed there was always some peculiarity of the magic that made it impossible to harness industrially.

While seeking a solution to the brimstone problem, and for reasons unknown, the heavily reinforced furnace exploded. The damage was still visible in the upper corner, where the thick metal turned outward like shark’s teeth. That hole was now the primary ingress to the space. Of course, in the conflagration that followed the explosion, the true nature of Dunvluddich’s experiments was revealed and he was sanctioned by The Masters and told to stop at once upon punishment of dispossession—or worse. He didn’t, of course. He moved instead to Chicago, where the hellion ultimately escaped, triggering the Great Fire of 1871. Abraham Dunvluddich was tried and convicted by a tribunal magique and imprisoned. By the time I met him, he’d been locked in a cell so long that he was both quite aged and quite mad. He never stopped designing, however. The walls of our cell were covered in arcane engineering diagrams, one on top of the other.

In the intervening century and a half, his furnace—which had been buried, since smelting was deemed prohibitively expensive—had become the stronghold of the mizzen…

a snippet from my forthcoming occult mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS