Rick Wayne's Blog, page 73

July 26, 2018

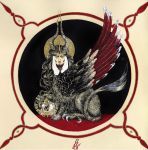

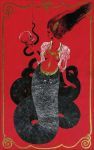

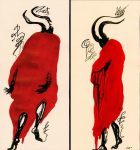

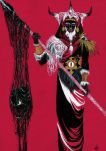

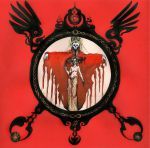

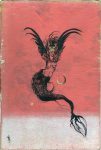

The High-Fashion Occult Art of Luciana Lupe Vasconcelos

Luciana Lupe Vasconcelos (b. 1982) is a self-taught illustrator and former tattoo artist from Brazil whose highly stylized works explore motivating mythos of dark ritual, often with the brilliantly simple color scheme of black and blood red.

July 25, 2018

(Fiction) The Scent of Dreaming

As I ascended the ladder-like steps to the cupola, my mind was on thread and silk and how I wanted to look my best for Benjamin’s funeral. When I reached the top, I found that reaching the trap door to close it unfortunately required me to ascend halfway into the octagonal room, which was barely large enough for three people to stand. There was a conical roof overhead rimmed in slat windows. Small statues, no more than two feet tall, rested in the concave nooks at the center of each of the eight walls, with the exception of one, whose figure had fallen to the floor. It wasn’t until I stepped into the space and lifted it that I realized I could see everything clearly, despite that it was then the middle of the night and there were no electric lights above me. The windows let in a hazy orange glow, as if it were dusk in a sand storm. I looked down at the statue in my hand, a prancing satyr who grinned at me as if he knew something terrible was about to happen. I replaced him in his nook and turned his face toward the wall, which is how all of the other statues rested, before quickly descending and locking the trap door behind me.

My feet reached the floor of the attic and I turned in the direction of an old chest where I had before noticed a torn satin dressing gown only to find that the chest was missing. In fact, everything was missing. I turned slowly. The room in which I stood was was very different. It was still an attic and it was still appointed with stacked chests and clutter, but it was different clutter. And the room itself was both larger and L-shaped, which was never the case before. It was as if in descending from the cupola, I had entered the attic of a different house.

I looked up to the trap door. Perhaps it was best to retrace my steps. I climbed the stairs only to find that the lock was no longer on the exterior of the door, which was immovable. I was certain then that there was something moving on the other side, something man-sized, at least. I thought I heard shallow breathing near the hinges, as if something were watching me through the crack, and the hairs on my arms stood, as did the ones on the back of my neck, just like when little Mattie appeared. I decided it was better to try a different way. I climbed down again slowly, stood, and listened. But other than the rustle of an occasional breeze, there was nothing.

The house groaned then, just as it had right before the spire fell, and the attic to my left seemed to stretch away from me. I walked swiftly to my right and around a corner, where I almost ran into a full suit of horse armor on a Trojan stand. I stepped around it and made my way down the stairs, which exited not into a open room but into a kind of secret passageway. There were joists over my head. To my left was a solid wall made of struts that oozed dried glue between them. To my right was a thin wall beyond which was the house—or whatever version of the house existed in that place.

I heard sounds. Voices. I couldn’t make the words, but I recognized Annie and Martin.

“Annie!” I called “Annie! Annie!” I pounded on the walls and repeated the name. “Annie!”

Her voice got louder then but still sounded as though she were yelling through a stack of pillows. There was a silence pause, and just as I was to begin pounding again, I both heard and felt scraping.

I pulled my hand back.

“Mila?”

It was Annewyn’s voice. It rang clear, as if there were truly nothing but drywall between us.

“Mila? [indecipherable muttering] hear me?” Her voice faded in and out as if someone was adjusting the sound on a radio.

“Yes! Annie, I can hear you! The cupola was open. I went to close it. I seem to be stuck. Somewhere.”

“You’re going [indecipherable muttering] your way out!” she called.

Already her voice sounded further away, as if she had stepped to the far side of the room. Whatever spell she had cast was already fading—or perhaps was being countered.

“Do you hear [indecipherable muttering] find your way. There’s nothing [indecipherable muttering] to you. Okay?”

“Annie?” She seemed even further away then. “I hear you. But I don’t know the way!”

I paused.

“Annie!”

I heard more muttering, but this was as faint as before. Nor did it sound any clearer after several minutes of waiting. In fact, it seemed then that whatever was being said was no longer directed at me, that Annie and Martin had given up trying to contact me and were talking worriedly to each other.

I knew where I was—in the general sense, at least. I knew where I was in the same way that, when one is lost in a forest, one knows it’s a forest—perhaps even which forest—but I had no idea how to get out. I was in the spirit world. What I did not know was which spirit, for there are two: one above and one below. The latter is sometimes called the shadow realm since it is the inverted shadow cast by the light of higher dimensions striking our thin film of reality, where as the former, what the Aborigines called the Dreaming, is the kaleidoscopic refraction of that light. Of course, I imagine it goes without saying that, given the choice of where to be stranded, the one is infinitely better than the other.

I looked up and down the narrow passage, whose ends curved away from me as if seen through a lens, making it impossible to guess just how far they actually stretched. It could be either. I supposed I would find out soon enough; the shadow realm was host to terrors that would never suffer the living, mortal or immortal.

Westminster chimes rang then, as if from a grandfather clock. But it wasn’t a clock. It was a recording of a clock. A vinyl record had started playing. I could faintly hear the scratches as the sound moved like a pale echo through the halls. After the chimes, the music started, but I already recognized it even though I hadn’t heard the song in ages—not since my time with Hank. We had danced to it, in fact, the one and only night we slept together. It was “Three O’Clock in the Morning” by Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra, recorded in the early 1920s. I listened as the gentle swinging horn section danced off the walls amid the crackle of the scratches.

Since I could no longer see the staircase that had deposited me, I started again down the narrow passage behind the walls which, despite subtle changes in texture or appearance, remained basically the same. The path was straight and never-ending, and despite that I traversed it for some time, the song never seemed to end, nor did it start over. Neither did it get louder or softer as I walked. Given the distances that stretched before and behind me, it seemed like there should be an echo. Its absence only amplified the overpowering sense that there was something wrong with that place. That it wasn’t right.

It was dusty in the passage, as you might expect, and at some point I had to press a finger under my nose to keep from sneezing. It ran, and I sniffed, which is when I noticed the complete lack of scent. I inhaled deeply through my nostrils, let it out, and did it again. But there was nothing, which was uncanny—more so than I expected. Scent is not a way by which humans typically make their way in the world. You don’t realize just how much you rely on it until it’s stripped from you.

I stopped. The hairs on my neck had stood. I was being watched. I turned and saw Anna and her stringy hair standing silently some ten paces behind. She was still wearing the drab brown dress we buried her in. She was next to a door that hadn’t been there when I passed. It was open, and upon noticing it, I heard the music louder, as if the space beyond held its source. After a pause, she went through. I of course followed as quickly as I could lest the door disappear as fast as it came.

On the other side was a billiard room with an impossibly high ceiling. The walls were lined with bookshelves to a height of about eight feet. All of the books were backwards such that their spines faced the wall. A large Victrola, complete with wooden horn, turned in the corner, spewing Whiteman’s seemingly endless song. Four pool tables took up the rest of the space. Each was topped in red velvet. The one in the back corner was the only in use. Six figures stood silently behind, including little Matti, the ghost who had come to see the stranger that invaded her home. A diagonal shadow his her face. The adult figures around her held pool sticks. The long lamps that hung over the tables obscured their faces as the shadow did hers, but by their stance, and their silence, I was sure each was watching me—partly curious, partly impatient for me to leave them to their eternal reverie.

Anna should’ve been just in front of me as I entered the room, but as I turned through the door, I saw she was waiting for me in another door on the far side. She was leading me past the ghosts, deeper into whatever realm I had entered. As I walked toward her, the hanging lamps, covered in frosted green glass, always managed to hide the faces of the others, who never moved. Not wishing to press my luck, I stepped through the door swiftly but without seeming afraid, and it shut behind me.

As soon as I turned, it was gone. The music stopped abruptly. Now there was only a distant hollow breeze. I was in a long, narrow hallway, as in a mansion, but without doors or windows. As before, it stretched in either direction as far as I could see. The walls rose so high that the ceiling was completely obscured by shadow. Whether it was ten feet tall or fifty, I couldn’t tell. The brown wainscoting on the walls was heavily scuffed while the wallpaper above it was pale tan with faded brown pinstripes. On it hung a myriad of framed pictures. Thousands and thousands of them. More, even. They were hanging close to each other but were tastefully arranged, and they filled the walls to their height. No two were the same. Most were rectangular, although a few were round or oval. Even fewer still were oddly-shaped. I saw a cast-iron frame in the shape of a fleur-de-lis and a wooden one in the shape of a cat. Inside each was a still photo captured from a memory—my memory. The hall was my life. I stood at the point of my last parting, when Beltran and I decided we could no longer live as husband and wife. Behind me was the past. Somewhere ahead was my first meeting with the young shaman who would change my life forever.

I lifted a round frame, like a wooden plate, from the wall. It hung from a nail on a loop of yellow ribbon. The border, which was wider than the picture, was seemingly hand-painted in a repeating floral pattern. Inside the circular window, Beltran and I posed for a picture that had never been taken. He was wearing his high fur hat with the mighty buckle. I was in a wool coat with a high collar. The sun shone. The mountain wind blew. We looked so happy, but our eyes were tinged with sadness. He had then begun asking for what I could not give.

My finger traced the firm line of his jaw. It had been years since I’d seen his face. Decades, even. It took every ounce of strength not to cry at the sight of it, although my lip did quiver. And I smiled. However it ended, he did love me. Genuinely.

I replaced the picture on the wall and turned my eyes over the others nearby. I began walking forward. As much as I would’ve loved to see the face of my father one last time—or even that of my mother, who died in childbirth and who I only knew from a single painting that hung over the hearth in the great room—I knew that there were no surprises in the past, only traps and peril. Whatever I was there to discover, I was sure it lay forward in the wastes of the unknown, and I took up a brisk pace. I saw Istanbul and Little Village and a ceramic terrine in my kitchen in which I cooked most of my meals and of which I used to be quite fond.

Still I walked. And then came the gaps, spaces where many of the pictures were missing, frame and all. The only evidence of their prior existence was the slight discoloration on the pinstriped wallpaper. In a few steps, the walls were all but bare. Only a few pictures remained. I saw the derelict train station in the woods and the cafe where I tasted the Nectar of Death. I saw a cemetery grown with trees and a grave filled with books. And I saw Etude. Younger. Skinnier. Softer. With a sheepish grin under that great bald head that contained the world.

Then, just like that, the gaps ended and the walls were full again. So many pictures, so many frames. I saw the hall of The Masters, and the Great Eye shattered. I saw Beltran as a very old man. I saw a fantastic coat and the Safari Gastronomique and a leopard-man and the towering horns of a long-dead beast. I saw the Great Wall and a voodoo woman jumping into a pyre and Granny Tuesday and the Dunvluddich Furnace and our flight from what was released there. I saw my first night with Benjamin and our first visit from Oliver Waxman. I saw poor Dr. Alexander hanging in the poison garden. I saw Cerise’s dead body curled in a pot and the detective woman and the tree in the sanctum burning like an effigy to hope.

And then I saw the chair. Benjamin’s precious cargo. Only this picture was no mere photo, as were all the others. It was a portrait, a painting in oil and at least four feet high with a frame of pure gold that looked like it had been pilfered from the halls of Versailles. In it, the chair was cracked—and gloating. To one side, I saw a black and white photo of Saycroft House flooded by the ocean to a height of three feet, and that was it. For before me the entire wall of the house was missing. Beyond was the water of the Chesapeake, which had risen in catastrophe to lap at the house, exactly as in the picture. It seemed like it had been doing so for a very long time—long enough to have pulled down the windward wall. The floorboards under my feet poked out, cracked and jagged, over empty space. Below were the two lower floors of the house, while far out to sea, so distant as to be shrouded in haze, was a monster the size of a mountain. It strode slowly northward, up the bay, as if moving in slow motion, its upper half shrouded in orange hazy clouds. Its massive tentacles, too numerous to count, alternated between the earth and its mouth as if it were a grazing elephant.

It was grazing, in fact. It was too far to see clearly, but somehow I knew then not only that it was grazing, but that it was grazing on people, plucking them from huddled crowds hiding under the ruins of skyscrapers. It slid its tentacles into the gaps of the buildings like the tongue of an anteater through a termite mound. It wrapped up whole families and pulled them screaming to its seven-holed maw. What they became after stewing in its intestines, what emerged dripping and snarling from its anus, I cannot begin to describe. Pray only that you never meet one.

It was the future, I was sure. It’s what was coming to the earth, a return to the bondage we had slipped eons ago. But it wasn’t the distant future. It wasn’t what would come if some arcane string of whether-or-nots came to pass. This future was days from us. At most.

Days.

Our last days.

Suddenly the giant creature turned as if it had heard a noise. It lumbered at first as it swung its feet around. But soon it picked up speed. I had a sense then of its power, for its legs were pushing an ocean in front of it, and yet it came right toward me, toward the broken remnants of Saycroft House. I turned about looking for some kind of escape. I was certain there was no way back down the hall, for that was my past—one unbroken line of action to the dead end of my birth—whereas what lay in front of me was the wide open future.

But the floorboards were shattered and two floors below was the shallow ocean. I didn’t know where to go. I didn’t know where I could run or what place could possibly shelter me from the beast, who was one of the six Nameless. It had sensed me, I was sure, and although it was in the future, I knew that place was a timeless shade of the real and a being such as that could pluck me from it and I would reenter the real world at that terrible point, having skipped over all that came between. I needed to escape.

I heard a buzzing and a flapping then, as if from a swarm of large, batlike insects. I looked up and saw black dots swirling in the sky. Devils. Thousands of devils. Preparing to pounce. I caught movement one floor down and saw Anna in her burial dress. She was looking silently up at me. She was waiting. On the floor near my feet was a loose photo, unframed. A long room of cabinets and hardwood was twisted and splintered, as if the room itself had been wrung like a wet rag. The devastation was incredible, but still, I recognized. It was The Barrows. I looked to Anna. I looked again at the picture.

“There’s no frame,” I whispered. I raised my eyes to her again. “You’re showing me the future.”

She moved out of my sight and I folded the picture and stuffed it in my pocket. I dropped to my hands and knees and made my way carefully over the shattered boards, whose ends were capped in sharp splinters. I glanced to the orange-tinted sky and could just make out the faces of the descending devils. Behind me, I could hear the crash of the ocean pushed forward by the ancient god as it strode mightily. I lost my concentration and slipped and fell, and a long splinter buried itself in my hand as it was ripped across the wood.

Anna had already moved across the broken sitting room and into the hallway beyond, and I forced my feet to follow as I pulled the bloody splinter free with a shriek. When I reached the hall, she disappeared around a far corner. Each movement of her seemed instantaneous. I heard devils land on the roof. I heard their scratching. I heard their shrieks. I heard the first waves of the impending tsunami fill the ground floor of the house with a rush. I heard clatter as it lifted clocks and furniture and cast them against the walls. I heard a rumble then, like the cross between an elephant and a lion, and the whole house shook. Glass clinked in cabinets. Pictures rattled and turned crooked on their nails.

The ancient nameless god had come.

The devils broke into the house as Anna moved at last. She raised an arm to direct me around the left corner of the hall, where there was a short nook with two doors, one next to the other, on the back wall.

I stopped. Which did I take?

I turned to her, but her arm had again fallen to the side. She simply looked at me, scared but helpless.

Devils entered the hall, whooping and snarling, and I turned with a fright. They had me—or so I thought. But Anna raised both her arms and a door shut in front of them where there had been none a moment before. They clawed and pounded against it. It would not take them long to break through.

The house groaned. The giant wave pushed by the striding god crashed over the roof. Sea water fell from every crack and drenched everything. I turned to the doors. The motion spun my wet hair and it struck my face. I had been given a vision. I looked to her.

“You’re giving me a choice.”

I looked between the doors. One was scuffed and shabby, the other painted and pristine. Did that mean I was to take the lesser door or the greater?

I heard the bellow then, directly overhead, and a terrible crash. The god was tearing the house apart. I turned again to Anna, hoping to plead some guidance from her, and I felt the heavy coin shift in my pocket.

Of course.

The Moirai penny. I would surrender to Fate.

I took it out and flipped it in the air and caught it with one hand and pressed to the back of the other. I held it there for a moment.

“Heads, to the left. Tails, to the right.”

I removed my hand. Heads. I went for the scuffed door to the left just as the entire roof and upper floor of the house was torn free, lifted off in one piece as if by a tornado. It flew high into the air and I saw dark clouds and swirling devils and the tendrils of the mighty god and its seven-hold maw lined with millions upon millions of teeth. I saw a giant tentacle plunge for me.

At the last moment, Anna shoved the empty air before her and I was propelled through the door with force. The last thing I saw was the tentacle wrapping around her and pulling her to the sky, her arms reaching for me, a scream on her lips. For the beast had ripped her from shadow just before I fell out of a broom closet. Its door swung open and I tumbled to the hardwood as long handles and plastic bottles hit the floor beside me. I stood immediately and slapped my palm against the back wall, but it was solid.

“ANNA!”

I was back in Saycroft House. The sun was shining. I stood in a puddle amid a tangle of broom handles and sideways spray cleaners. I was drenched. I smelled of sea salt and iron. Watery blood dribbled from the splinter gash in my palm. I looked at it. My arm was shaking. Pain throbbed down to the elbow. Behind me, the foyer of the house had been cleared in anticipation of Benjamin’s funeral.

“There you are,” Annewyn said from the stairs, as if a sundered world were whole again. “I knew you’d make it out.” Then she saw my face and my bloody hand and the puddle that had dripped form my clothes and hair. “What happened?”

I fell to the floor, crying. “Anna . . .”

July 24, 2018

Now With More Pulp!

July 22, 2018

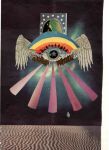

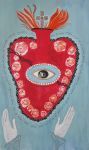

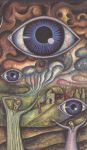

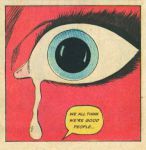

The eyes have it

“Everything in the world is strange and marvelous to well-open eyes.”

― José Ortega y Gasset, The Revolt of the Masses

July 21, 2018

Ambush from Ten Sides

Han Chinese are the single largest ethnic group in the world. At 1.3 billion people, they constitute 18% of the total population of the human species. There is simply nothing analogous to it in the West — not just their size but their unbroken antiquity. Chinese people speak the same language(s) as their forebears. Mandarin and Cantonese have evolved of course, but there was nothing like the bastardization due to foreign appropriation that characterizes Latin derivatives like French and Spanish.

In fact, that unbroken continuity is the reason Mandarin Chinese in particular is so distinctive. Human mouths are lazy. We tend to slur our words in casual speech, which is why, in the days before widespread literacy when almost all speech was colloquial, hard consonants tended to erode over time — because they take more effort to pronounce. That Chinese has so few hard consonants is linguistic evidence of its great age. It is as weathered as a Roman ruin.

But it isn’t just the language. The Han Chinese occupy the same politico-geographic area as their forebears in a way that has no corollary in the West. The Jewish people, for example, are recognizably and historically ancient, but for most of that time they’ve occupied no lands, had no state, and so their history — by which I mean the narrative of their people, not a scientific accounting of events — is a “private” history consisting mostly of their thoughts about themselves along with records of what has been done to them.

The Han people are also ancient — bewilderingly so. They occupied the Yellow River Valley at least back to neolithic times. But unlike the Hebrews or the Greeks, after establishing the Han Dynasty in 202 BC, they never left. For the Chinese, Han culture is “classic” in much the same way that Graeco-Roman culture, a contemporary, is for Europeans. Indeed, the Chinese still use “Han characters” in the sense that we still use “Arabic numerals” (which the Arabs adapted from the Indians).

Incidentally, the dynasty before the Han was the Qin, the first formal dynasty in Chinese history, from which we get our name “China,” as the land of the Hindu people is “Hindia.” The Qin Dynasty, however, lasted a mere 15 years, from 221-206 BC. If language were less serendipitous, our name for China would probably be something like “Hania,” the land of the Han people, who make up 92% of mainland Chinese.

Theirs is a very “public” history. Any Chinese citizen can look back on thousands of years where people who looked like them and spoke like them did more or less the same stuff they do and in the same place where they still do it — writing music, gardening, filling books with calligraphic poetry, winning battles, giving great speeches, etc. (The same is true of Japan, who trace their history unbroken from about the year 800 but which of course extends back to prehistory, to the Jomon period.)

Therein lies the big lie of world history classes: that Western culture is the successor of the Graeco-Roman. It most certainly is NOT. Your great-great-grandfather was not a Roman consul — not genetically, not linguistically, not culturally. If you’re European by ancestry, your great-great-grandfather was the sweaty barbarian who sacked and burned Rome. We’re not her heirs. We’re her assassins.

Western culture really began in the Renaissance. Of course, at the point of its formulation, it was very much an elite enterprise, which is to say most people in Europe — even most of the wealthy and powerful — were still living a fundamentally medieval-feudal lifestyle (pockets of which survived well into the 20th century). Renaissance culture didn’t spring from nowhere. It built on both medieval and Graeco-Roman antecedents. Nor did it appear “fully formed.” It has continued to grow and change. But still, our fundamental approach to the world — humanistic, rational, ideological — was born in the Renaissance.

Not surprisingly then that in casual use, “classical” refers to Renaissance and related periods. (In academic discourse, it means antiquity.) Yes, we still don medieval dress when we graduate. Yes, there are still lots of people practicing the religion of the Roman Empire. But the fact remains, most major cities in the Western world have a “classical music” station, and what is being played on it right now is not music from ancient Rome. Nor is it even Renaissance music to be honest. As I mentioned, daily life during the intellectual Renaissance was still more or less as it had been, and that included music. Renaissance music was still fundamentally medieval.

It wasn’t until the elite ideas of the intellectual Renaissance began to seep out of the universities that artists and musicians took note. So, for example, you probably can’t name a single Renaissance (or earlier) composer off the top of your head, but you can almost certainly name some of the stars of the very next era of Western art, the Baroque, which includes household names like J.S. Bach, Vivaldi, Handel, and Pachelbel, whose Canon in D is a perennial favorite at weddings. Ours is a Renaissance, not an antique culture.

Not so in China, whose culture is contiguous with its ancient past. As an example of this pervasive antiquity, I present the song below. The instrument is the pipa, a kind of four-stringed lute. Of course, the pipa isn’t popular like rap music is popular, but then neither is the violin. Yet, both are still learned and played. There are pipa virtuosos alive today. You can get tickets to pipa concerts in large music halls. It is a classical instrument.

The difference between the violin and the pipa is the difference between Western and Chinese culture. Its origins are murky of course, but the first recorded mention of the pipa came during — you guessed it — the Han Dynasty, around the 2nd century AD. This song, whose origins are also murky, has existed in some form for at least 500 years and commemorates the Battle of Gaixia, where in 202 BC the Han leader Liu Bang decisively defeated his rival, the warlord Xiang Yu from the state of Chu.

The closest thing to the Battle of Gaixia in the West is probably the Battle of Salamis (480 BC), where the Greeks decisively defeated the Persians, thereby creating a Europe free of oriental rule, which had defined civilization up to that point. Alternatively, you could pick the defeat of Marc Antony and Cleopatra (a Greek descendant of one of Alexander’s generals) by the forces of Caesar Augustus at the Battle of Actium in 27 BC. But in either case, it’s not really the same. For the analogy to hold, everyone in Europe and North America would have to speak Greek — or Latin, but that shift is already indicative of a change not present in the history of China.

To illustrate, imagine getting off work to attend your kid’s Greek lyre recital wherein they pluck a song commemorating Salamis, a song whose tune everyone knows by heart, like Beethoven’s fifth. Imagine going to a wedding this weekend where the pastor reads relevant sections of Paul’s epistles in their original Greek, and you can almost kinda understand parts of it. Imagine the bride walks down the aisle accompanied by flute music that could’ve easily been heard at the Greek-speaking court of Charlemagne. Imagine Fourth of July celebrations where the marching bands don’t sound terribly different than those of Sparta (or imperial Rome) because many of the instruments are very similar.

The fact that none of that is the case shows that our culture is not ancient — certainly not in the way that Chinese culture is. To be native Chinese is to be the recipient of 2,300 years of contiguous history, which is awe-some to me.

One final point. I need only show that we could’ve been the heirs of Greece or Rome to prove that we are not. As a matter of record, when the Greek-speaking Byzantines marched out to face the marauding Turks in 1453 (one generation before Columbus), they called themselves Ῥωμαῖοι, or Romaioi, which is Greek for “Romans,” despite that few of the soldiers, if any, had ever once seen the old city. Alas, Constantinople fell to the Turks and with it the last political vestiges of an empire that had existed at the same time as the Han.

Elsewhere in 1453, the Ming emperors were building a great big wall to prevent exactly that kind of thing from happening. Again. They didn’t know that the next invasion would come not by land, as it always had before, but by sea — in the form of British warships.

Anyway, here is “Ambush from Ten Sides,” classical music for the pipa. There are roughly four “movements.” The first introduces the combatants. The second, a medley of point and counterpoint, describes the battle. The third is a kind of lament — the defeat of Xiang Yu and his subsequent suicide by the river. The last, in frenetic strumming reminiscent of the roaring of crowds, proclaims the victory of Liu Bang and the founding of the Han Dynasty, the first stable, long-lived dynasty in a series of the same that stretched all the way to the 20th century. Perhaps you can understand then why the person who posted the video wrote at the end of the title: “I still can’t breathe when I hear this!”

This version was made for Chinese TV in the late 60s or early 70s (I think) and is a solo performance by pipa master Liu Dehai, who is still alive. Note the delicate finger work, especially around 2:30 mark. The composition is apparently so difficult it can only be approached by a virtuoso.

July 20, 2018

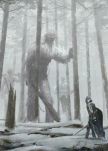

Encountering the Old Gods

There’s a trend in contemporary fantastic art so pervasive that I feel it needs it’s own genre: the casual hierophany.

A hierophany is a manifestation of the divine other. The name implies more than a mere appearance, however, which could come simply in a vision. A hierophany is an eruption of divine force in our world that brings both awe and terror.

In classic art and literature, hierophanies were often intentional conversions, an appearance of the divine intended to bring about a change in man. The classic case is probably the Biblical story of Saul on the road to Damascus, painted many times but most famously by Caravaggio in 1600.

[image error]

Caravaggio’s manipulation of light and shadow is what makes this a masterpiece. The divine force which knocks Saul from his horse and blinds him is not depicted in the painting, but seems to pervade it nonetheless.

And yet, the focus is clearly on the man, both in the composition and in the story. Saul fills the painting from side to side. Not only is God is absent, His only reason for “appearing” is Saul, whose outstretched arms catch the divine light as well as the viewer’s gaze like a funnel, focusing them on him, on his face and breast. (The gaze and stoop of both attendant and mount do the same.)

This preoccupation with ourselves continued even into less explicitly religious eras. Take Caspar David Friedrich’s 1818 “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog,” one of the defining works of the Romantic movement.

[image error]

Once again, man is the focus of the image, which was supposed to be about nature. The standing figure is the largest element of the composition save for the precipice and the sky, both of which are devoid of any real detail and, as mirror images of each other, focus your attention back on the human being at the very center of everything. Even as your eye wanders, you are constantly brought back to the man, who stands noble above it all almost as if in command of the world (which is the reason this image was used for the cover of Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra).

Now compare those two images with the infamous cover of the classic D&D box set, with art by Larry Elmore.

[image error]

Once again, the human figure is in the foreground and stands in sharpest relief. The dragon, although larger, blends into the wall and treasure. In the very center is the shield and glowing sword, whose stroke we can almost see moving. In conjunction with the brilliant use of white space (which creates a 3D-like effect where the dragon practically reaches out from the box to embrace you), the weapons serve as a promise: inside lies adventure. We are invited to identify with the faceless barbarian, whose features are completely obscured. “He” could be anyone, even — conceivably — a woman.

This image, besides being wonderful fun, is an utterly brilliant bit of marketing. It’s also the archetypal fantasy art, replicated many times over. There may be a basilisk instead of a dragon, a mage instead of a warrior, or perhaps even multiple figures battling multiple foes, but the fundamental themes are set. The magical Other is larger than life, but its attention — as with God in the Caravaggio — is on the players, who are human (even if the literal representation is of, say, elves or dwarves). The humans are the true focus of the action, the symbolic center.

And there is quite a lot of action. Those humans are not passive recipients of grace nor stoic observers of nature but are in active resistance against the Other, which has come to devour them. As players, we both are and make the world.

Now, contrast that image with this one by Bjarke Pedersen.

[image error]

Or these of encounters with dragons by Mateusz Lenart and others. (Click for larger image.)

Or even this.

[image error]

This morning I collected nearly 80 images like this, all with the same fundamental features, and yet, I only seemed to scratch the surface. Indeed, I had to force myself to stop looking because it seemed as if there were no end to this kind of thing!

Not all were explicitly fantastic. Some, for example, were whimsical.

Nor is this phenomenon limited to fantastic art (although it clearly flourishes there). This is work by fine artist Dawid Planeta, who has a whole series like this.

[image error]

The significant features, as I’m sure you can tell, are fundamentally identical to each other and different from what’s come before. First and foremost, the human figures are very small. They still occupy the foreground and may often be “centered,” but they are tiny. They are not the focus. The god is the focus — or rather the encounter itself, which is nuanced rather than combative.

Even more important than their change in relative size, however, is how the people in these images are no longer active. They are typically standing in silence or otherwise going about their day. Occasionally, a weapon is drawn, but it seems fundamentally defensive. And also somewhat useless. There is no sense, as with the Elmore painting, that we could do the god any harm. Nor is it clear the god, dragon, monster, or robot has any interest in the puny mortals before it.

[image error]

[image error]

In the image below, the summoned god doesn’t even seem to care about the sacrifice its supplicants have prepared for it. Whatever it’s after, it’s indifferent to us.

[image error]

That’s not to suggest these beings are harmless. Indeed, they could wipe us away with the swoosh of their pant leg and barely be aware. Rather, it’s that we are no longer the raiders of their treasure. We are not their foes, nor are they the object of our worship. They are, if anything, mere novelties whose movements have no real effect on our lives.

[image error]

To be clear: for an image to qualify in the genre, I propose three essential features. First, it must depict an encounter. In other words, humans (or humanlike entities) must be present, otherwise it’s just a picture of a big monster.

Second, the god or monster or demon or whatever must be epic in scale and not, for example, an orc warily passing a man on a mountain road.

Third, the encounter between the two must be incidental. It needs to depict a fundamental disconnect between the participants. These are not images of worship, where people supplicate themselves before the deity. These are not images of attack, such as Godzilla destroying Tokyo. There can be (and often is) a sense of awe or terror, but there doesn’t have to be. The encounter must be unexpected and both parties must remain fundamentally unchanged by it.

The last point is tricky, for as I indicated, the god may sweep us aside, may step on our buildings, may burn us all to a cinder, but if so, it’s in pursuit of a higher aim. That is, mankind is not the focus of its rage, as in eras past. Indeed, the god may already be dead.

[image error]

But if so, the man is not devastated by the discovery, nor is the god revived by his prayers.

The examples are legion and expand almost infinitely to include symbolic “gods,” such as in this now famous work by Yuri Schwedoff:

[image error]

Or this work by Beeple:

[image error]

where the “gods” are alien, are our creations, or are ourselves as we used to be, our lost potency.

Examples abound. Note in all of the images below the three fundamental features: the tiny, passive figures; the towering elemental force; the relative indifference between the two.

As I mentioned, at some point I simply had to stop collecting for it seemed there was no end to this kind of thing, which of course raises the question: Why?

Do we no longer fear nature? Do we not care whether it is living or dead? Do we not fear the past or the future? Do we not fear anything? Do we not feel anything? Is the world itself a mere novelty? Are we perfect and no longer in need of salvation?

July 19, 2018

Imaginary Architectures

James Jean

Demetrios Zissiadis

Ben Tolman

Jacob Van Loon

Catarina Stewart

Henry Vincent

Click for larger image

July 18, 2018

The fairy tales of Cory Godbey

Godbey is an illustrator, chiefly of children’s books, based out of Greenville, SC who has done work for several notable clients, including the Jim Henson Company, for whom he illustrated graphic versions of the fantasy film classics Labyrinth and The Dark Crystal. He just kickstarted an art book collecting the first five sketchbooks of his career.

Find more of his work at: http://corygodbey.com/

July 16, 2018

The Chapel in the Woods

John Caple

Karl Friedrich Lessing, Die Waldkapelle

Christof Grobelski, The Temple

Grant Wood, Arbor Day

Van Gogh, The Church in Nuenen