Rick Wayne's Blog, page 71

August 20, 2018

The Preternatural Elegance of Eyvind Earle

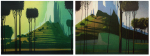

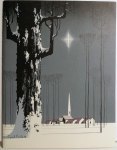

Even if you’ve never heard his name, you know the work of American painter and illustrator Eyvind Earle, who not only gave the Disney films of the 1950s their distinctive look but also inaugurated an entire genre of holiday greeting cards, whose style you’ll recognize in some of the images below.

But by the time he started work on “Sleeping Beauty” in 1951 — a film that had already been in production and wouldn’t be released until 1959, taking ten years to complete — Earle was already a successful artist, having earned his first solo show in New York in 1937. He was, to some degree, a victim of his own commercial success. With his distinctive flair now indelibly linked to the films that bear his mark, it’s hard for us to see his paintings as anything more than animation cels, but to me, Eyvind Earle, along with designer Saul Bass, is an archetype the mid-century style, with its emphasis on minimalism and straight lines. (You can decide for yourself what that says about the era.)

Like his earlier contemporary, Normal Rockwell, Eyvind Earle made beautiful “everyday art,” art meant to be looked at and enjoyed in the home — on the wall, on greeting cards, on magazine covers. Pay particular attention to his use of perspective, light, and shadow, in other words his use of angle and line. Also note the high influence of Eastern screen painting and woodcuts on his pastorals: the way a single branch drapes down in front of a view of an exaggeratedly broad forest or steep mountain face.

The Natural Elegance of Eyvind Earle

Even if you’ve never heard his name, you know the work of American painter and illustrator Eyvind Earle, who not only gave the Disney films of the 1950s their distinctive look but also inaugurated an entire genre of holiday greeting cards, whose style you’ll recognize in some of the images below.

But by the time he started work on “Sleeping Beauty” in 1951 — a film that had already been in production and wouldn’t be released until 1959, taking ten years to complete — Earle was already a successful artist, having earned his first solo show in New York in 1937. He was, to some degree, a victim of his own commercial success. With his distinctive flair now indelibly linked to the films that bear his mark, it’s hard for us to see his paintings as anything more than animation cels, but to me, Eyvind Earle, along with designer Saul Bass, is an archetype the mid-century style, with its emphasis on minimalism and straight lines. (You can decide for yourself what that says about the era.)

Like his earlier contemporary, Normal Rockwell, Eyvind Earle made beautiful “everyday art,” art meant to be looked at and enjoyed in the home — on the wall, on greeting cards, on magazine covers. Pay particular attention to his use of perspective, light, and shadow, in other words his use of angle and line. Also note the high influence of Eastern screen painting and woodcuts on his pastorals: the way a single branch drapes down in front of a view of an exaggeratedly broad forest or steep mountain face.

August 18, 2018

A joke in three bodies…

[image error]

Le Cadavre (1894) – Felix Vallotton

[image error]

Xteriors VIII (2004) — Desiree Dolron

[image error]

Happily Ever Cadaver (2013) — Grave Robbin’ Sam

Hardy-har-har…

Paintings like Felix Vallotton’s “Le Cadavre” (1894) are important in the history of Western art. Prior to the 19th century, almost all depictions of cadavers — which is to say bodies that are clearly dead, versus drowned maidens or heroes of Greek myth who always seem in a simple sleeplike repose — were of Christ the Redeemer. Vallotton is referring to those works explicitly since Christ, if not on the cross or being taken from it, was portrayed exactly like this: laid formally, hands at his side — a king in rags lying in state.

After the 17th century, there were some depictions of medical dissections, but the focus was almost always on the teacher, and of course the anatomy theater was crowded with lively young men seeking to learn. Death enters these works only obliquely, if at all. In fact, one could argue those paintings, in Whiggishly praising the heroes of medical science, were depicting the exact opposite: the battle with and eventual triumph of man over death.

Not so here. Vallotton’s cadaver is clearly dead, and he is only dead. He is not being dissected for science. He is not sleeping. Unlike the drowned maidens and fallen Greek heroes of yore, he has not simply sloughed his mortal coil. But neither is he consumed with disease and so turned from a man to a symbol of one or another social ill — pestilence or inequality. Nor is he Christ, whose humility in death precisely reveals his magnificence: the God who died for our sins and will rise again on the third day and yet who lays there still and humble as any man.

This fellow is someone, but he is not anyone. His face is obscured, along with the background. He is dead, the painting tells us, and he is only dead. He is dead, it says, as one day you and I will be, too. This painting isn’t about gods or heroes or beauty or sin or any of the grand themes of earlier epochs. It isn’t about Death Who Rides a Pale Horse. It’s about a human being.

August 16, 2018

Good “Evening”

This phenomenal art by Andrey Surnov is called “Evening.” Not only is she a wonderfully potent figure, but note the zipper. Night can be undone, which makes her body the dawn. Note how the setting sun hits only her exposed skin.

[image error]

A few more by the artist.

The Dreadful Melancholia of Anton Semenov

With titles like “Sorry,” “Dust,” and “Goodbye,” the disquieting work of Russian artist Anton Semenov, who goes by the name Gloom82, is steeped in apprehension and dread. Occasionally nightmarish or even whimsical, most of his paintings seem to have been pulled directly from the anxiety dreams that afflict us all in the early hours before waking: failure, loss, regret, doubt, shame, fear, paranoia.

Disquieting, indeed.

You can see more of the artist here.

August 14, 2018

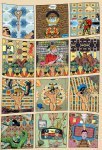

The Converse Comics of Samplerman

As an author and art-lover who has no talent for the visual arts, I’m fascinated by art that tells a story. I’m convinced there are pathways in our neuroanatomy that link our narrative interpretations of both prose and visual art.

These connections don’t have to be direct or linear. They can be oblique to one another, or even opposites. For example, I’ve often said that a novel is a painting whose canvas is stretched in time rather than in space. As such, the tools necessary to create artful prose are different than those for painting or illustration, but the two mediums share that relation.

Yvan Guillo, better known by the DJ-inspired name Samplerman, doesn’t tell stories with art, at least not the way we usually think about it. He does the converse. He “remixes” cast-off images from Golden and Silver Age comics, adopting the form of visual storytelling to create… something else.

I am a 46-year-old cartoonist. I’ve been writing and drawing comics for more than 25 years, without any popular success, I have to admit—perhaps because of a lack of self-confidence, not harassing publishers enough, taking no answer for a “no thanks,” and no longer posting my pages (lots of improvised and unfinished stories) on my obscure blogs.

I have always chosen the DIY way to make my fanzines and minicomics: it is affordable and it mostly requires commitment and time. Due to lack of feedback, I’ve felt discouraged from time to time. Sometimes I can’t believe that I’ve kept doing this for so long instead of finding a real job…

At the start, “Samplerman” was a side project. The first attempts sat on my hard drive for months before I posted them. These were very simple panels, in low resolution, that displayed samples of web-downloaded scans of “Superman” or “Fantastic Four” that I had duplicated and symmetrically joined: the most basic manipulation. The abstract visuals resulting from this treatment didn’t corrupt the seduction of the original drawings and colors, which were visually familiar though modified, like comics seen through a distorted mirror…

I make only the most minimal changes to the color. I may change the colors from parts of my samples for special effects, but I try to stay within the four-color spectrum of the letterpress printing technique that dominated comic books until the 1990s. It’s possible that I’ll break this rule in the future, and take the license to make more extreme adjustments.

Read the full interview with Yvan in The Comics Journal.

Click below for a larger image.

Find more work by the artist here.

August 12, 2018

(Fiction) The Seven Deaths of Harriet Chase

They call me Harry.

Despite what you may have heard, I’m nothing special. Trust me. But after you make it through a couple bad jobs, word gets around. You get on some short lists. They call you again. For transports, mostly. Escorts. To be honest, I haven’t been too picky about the clientele lately, although I do have a little guilt about that. But I gotta pay the rent, same as you. Heaven’s fun to work with and all, but Hell pays better. I figure when I win the lottery, I’ll donate my services to the Big Guy full time.

But that’s not what you wanna hear about. So here goes.

The first time I died was because of an angel on her way back to Heaven. It was kind of a big deal. Angels are majestic fucking creatures after all, and holy books all over the world are full of people falling to their feet and renouncing their sins at the sight of one. Physical manifestations of God’s grace and all that. Good things happen in their wake, I can tell you. Miracles. And you feel like a million bucks for days after.

That’s why the priests keep them shrouded – big, thick sunglasses; hoods; long coats; that sort of thing – and why they pretty much never speak. Supposedly that’s cheating. Supposedly people have to choose on faith or whatever, unswayed by angelic or demonic presence. It’s a bunch of horseshit, frankly, because both sides break that rule all the goddamned time. (Just don’t quote me on that.)

So here’s a cosmology lesson for you. The planes of existence aren’t all connected to each other. It’s fucking complicated, but basically it works like this. You can go from A to B and from A to C, but you can’t go from B to A, so if you’re on B, and you want to get to A, you gotta go through C.

Don’t ask me. I didn’t make the rules.

Earth is pretty much in the middle of everything, like the crossroads of existence. The Norse weren’t wrong about that. That’s why it’s so fucked up. We get the shit from everywhere. It’s also why there are so many transport jobs, and why it’s so risky. For all the lawyers and politicians we have – more per capita than just about anywhere, I’m told – Earth is still a mostly lawless, immoral ball of dirt, so if you’re looking to pinch someone from the other side, it’s better to try it here than just about anywhere else in existence.

Go us.

Only you can’t get to Heaven directly from Earth. You can go through Purgatory, but since that’s basically Hell-Lite, it’s not anyone’s preferred path. Next best thing takes you through three higher planes, which is fine since any number of nexuses on Earth can send you up one. You just need a ley line that runs in your direction, kinda like making sure you’re on the right track at the train station.

Used to be we listened to the geomancers and were careful where we built our shit. The Chinese still have the good sense to follow the rules of feng shui (for the most part), but the rest of the planet is all fucked up. Turns out there’s an upward-facing nexus at the top of the Hyatt Regency just outside O’Hare Airport, Chicago.

Who knew?

I was supposed to wait in the lobby until the angel showed up with her retinue. I was to nonchalantly follow in a separate elevator along with the rest of the crew, who were all milling about like we were waiting for a cab or something. And that’s pretty much exactly how it started. She came in like a pop star with monks for groupies. When they got into the elevator, I put down the magazine I wasn’t reading and followed.

Only I got stuck behind some members of a wedding party. This was a Sunday – angels try to do their traveling on the Sabbath – and the family were all leaving town after the wedding the day before. As the elevator stopped at each of their floors, they had to take like five fucking minutes to say their fucking goodbyes. By the time I got to the top, shit had already gone down.

Bodies slumped in the hall. Blood. A muffled scream from one of the rooms. The door was open, and I froze.

The monks and priests who organize this shit like to keep it all nonlethal. Fuckers. And they won’t fight themselves, which is what they hire us for. It was a condition of our employment that we could carry nothing more than a baton or a whiffer. I chose the latter, which, if you don’t know, is basically a battery-powered electrostatic air purifier with a blessed cross on the front, or maybe a reliquary of some kind. Fits in your hand. Blows holy air.

I’m not even joking.

If you get them in the eyes, it’s kind of like mace to a demon. Stuns them, blurs their vision, maybe puts them down, but also wears off quick. Holy water is better, but that does permanent damage and has even been known to kill, so it wasn’t allowed.

I thought about leaving. I really did. The pay wasn’t that good. But there were those tiny screams, like an animal – a bird or a puppy – helpless and crying. I cursed and pulled the whiffer and crept toward the room. I was alone in a hall full of the dead. I peered with one eye around the open door.

The demons were all in suits. They had dropped their disguises and their burned, ripped, skinless, deformed faces created quite a contrast with the Armani. They had the angel on her knees. One of the demons, a succubus with a pinned-open skull, held the angel’s arms behind her back. A male scourge demon had the angel’s head in his hands. He was forcing her mouth open while a second male stood over her and pursed his scaly lips. Two more stood by the door. They watched the action with their backs to me.

I fought back a gasp. A caustic ooze, full of fire and sin, bubbled up from the demon’s throat and fell in frothing drops into the angel’s open mouth.

Now, this is heresy, I know, but God has some fucked up sense of humor. He set it all up so the path of Good is full of patience and tenacity and wisdom and being the bigger person but not getting a big head about it and all that kinda crap. Being a saint is like swimming upstream. Every. Fucking. Day. It’s exhausting.

Meanwhile, falling into Hell is like falling down a hole. You don’t have to do much of anything except be lazy and not pay attention. God waits for us to choose, but the Devil claws at us, all the time, and it takes effort just to stand upright in the same damn place, let alone to climb upwards to Heaven.

All that means is that the artifacts of Heaven – like my stupid whiffer – repel demons, force them away, while artifacts of Hell – like the foam – have the opposite effect on angels. Demon venom is like heroin to the other side, only once it gets inside, the angel is corrupted.

That’s what demons do. Take a little good out of the world. Every. Fucking. Day.

To her credit, the angel struggled, but there were too many of them. Bastards. Unless an angel is one of the heavenly warriors – and there’s not many of them left these days – their power is not strength but grace and compassion, and while that’s great and all, it doesn’t do shit for you in a fight.

But those gurgles . . . And the fear in her eyes. And the knowledge that, if she swallowed too much of that crap, she’d never be allowed back into Heaven. It was too much.

I burst in with the whiffer and hit the two demons standing by the door. They turned and I got ‘em right in the eyes. They screamed and clawed at their faces. The others stopped. The angel dropped to the floor. Her eyes glazed. She was tripping hard on devil goo.

So, demons can play dead. It’s one of their many tricks. In the rush, I didn’t have a chance to check the hall. I took a risk and paid for it. One of the bodies on the floor wasn’t a victim. He was a guard. Playing possum. That’s why the others just waited. They saw him sneaking up behind me.

I felt a stab in my back. I went down. They laughed. I’m sure they all thought I was good as dead. And I should have been.

I mentioned before that I’d survived a couple bad jobs. There’s a reason for that. Turns out I’m immune to demon venom. It’s rare, but it happens, kind of like how some folks way back when were immune to the plague (which Hell totally started, by the way). Different demons have different kinds: shit that burns, shit that rots your flesh away, shit that drives you mad. So far, none of it’s done so much as give me a headache and a killer craving for Cheetos.

But still, being stabbed fucking hurts. So there I was cringing on one knee from the venom-filled talon some asshole hellspawn just jabbed into my back and with nothing to defend myself but a fistful of God’s holy farts.

The demons lifted the angel off the floor. She stumbled to her feet as they dragged her to the back toward a chair by the window. I could see downtown Chicago in the distance. Meanwhile, I was losing blood, and at any moment the demons would realize the venom hadn’t done the trick and would dispatch me the old fashioned way.

I didn’t really see where I had much of a choice, ya know? So I charged forward, tackled the angel, and crashed through the window. Sometimes it’s good to be husky.

Did I mention we were on the twelfth floor? That’s a loooooooong way down.

I’d like to say there was a pool at the bottom or a terrace just below. I’d like to say the hotel’s linen service was making a delivery at that exact time and that I landed on a pile of sheets.

But nope. Pavement city.

Didn’t hurt too bad seeing as how I died on impact.

And no, I wasn’t worried about the angel. Angels’ feet never touch the ground. The angel would float to a stop. The angel would be fucking fine.

All other things being equal, I should’ve gone straight down to the bad place. I haven’t been particularly evil, but I can’t say I’ve done much to swim upstream either. But seeing as how I died sacrificing myself for one of the Holy Host, I caught a break and ended up in between. Where the deals are made.

Technically, Limbo isn’t really anything, but what my mind saw was an endless hall of meeting rooms. I sat in one, behind a fold-out table – bureaucrats are cheap bastards everywhere – for what seemed like an eternity. And it probably was. I wasn’t sure what to expect. From what I heard, sometimes you got a deal from one side, sometimes from the other, sometimes both declined and you waited there in one of those rooms.

Forever.

I’m not sure what I expected, but it for damn sure wasn’t the bonus plan. Reps from both sides showed up and sat next to each other, expressionless. They slid their deals to me across the table. I said I needed a minute to look things over. You know, because it was such an important decision.

Sitting there alone in that room, eyes moving from packet to packet, I had a crazy thought. I lifted the pen-shaped needle they provided and pricked the index finger on both my right and left hands, then pressed them onto each deal simultaneously.

Guess what? No one had ever done that before, and apparently I shorted out some major shit. The deals canceled each other. Black was white. White was black. Whatever. I don’t know. But while they were running around trying to fix it all, I got sent back. I think they just wanted to be rid of me.

So there I was back on the pavement in front of the hotel, lying in a pool of my own blood. People are screaming. Next to me the angel is still tripping balls on demon spooge. I got a good look at her then. Wow.

Just wow.

I might have had a religious experience if a gang of Hell’s hooligans wasn’t about to come down and rip my face off.

So I stood up, wiped off the blood, smiled at the gasping bell hop, grabbed the angel’s arm, and bailed.

You’d think that would have been the hard part. You’d think that after beating demons and saving an angel and jumping from the twelfth floor and dying and shorting out the whole sorting system and coming back, things would have gotten a little easier. You’d think.

But you’d be wrong.

The universe has rules, as you probably know – things like the fucking gravitational constant and the conversion of matter to energy and don’t cry over spilled milk and dropped toast always lands on the buttered side. Supposedly everything is set up so that anyone can die seven times without a hitch. I guess they thought that would be enough of a buffer. I mean, you’re only supposed to die once, right? But then Jesus brought Lazarus back. And himself. And the bones of the prophet Elisha are supposed to resurrect anyone who touches them.

But for all of human history, that’s how it’s been. Onesies and twosies. No one’s gotten close to seven. In fact, as far as I know, the most anyone ever died was three times, and that was a fucking exceptional case. But since no one ever hit seven, no one knows what happens when you get there. Some people say the whole cycle of life and death breaks. Some say you meet God. Some say you just stay dead, except that this time nothing can bring you back (except maybe the Word of the Head Honcho himself).

Seven times. That’s what the universe was built for. That’s important.

They call me Harry, but my real name is Harriet. Harriet Chase. And this is the story of how I died seven times.

An older version of Harriet Chase (who narrates the third course of my forthcoming occult mystery) that I never ended up doing anything with.

August 11, 2018

A fiction truer than reality

It might seem like all fiction tells stories, but that’s not true. I read Italo Calvino’s “Invisible Cities” last week, and like a lot of literature, it didn’t so much unfold as describe. At the border of storytelling are books like Lord Dunsany’s “The Gods of Pegana,” which I’m reading now, or even Lovecraft’s “At the Mountains of Madness,” where the events that transpire are really more about capturing a mood.

It seems to me that at a fundamental level, stories are meant to capture some kind of change in time. “At the Mountains of Madness” is only half a story for the same reason Borges’ “The Immortal” is. Indeed, both recount the discovery of an ancient abandoned city, something that is so old it is expressly intended to exist outside time. The authors do not give us change but something to digest. In Lovecraft’s case, an emotion. In Borges’, a philosophical question.

[image error]

This painting above by Juan Martinez Bengoechea functions that way. There is a kind of narrative to it in that we can imagine any number of explanations for how these people got here and what’s going on, but there’s no sense of change in time. Indeed, the subject matter, photography, implies an eternal moment, and that implication is amplified by the fact that this clearly takes place in the past.

What makes it brilliant is how the camera’s subject — the thing to be preserved — is outside the frame of the image, and all the subjects are turned away from us, as well as from each other. As with “Invisible Cities,” we are not given a story so much as something to ponder.

[image error]

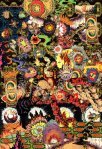

I’m not talking about that. I’m talking about storytelling in the way the Pixar guys talk about it, and I’ve been coming at it sideways through the medium of art, which exists in space and not in time (versus prose, which exists in time and not space), so it has to be very economical in how it tells a “story.”

Comic art — editorial, strips, books — is the master of this since the whole point is to tell a story. Even if it’s a single panel, a comic is, as Scott McCloud defined it, sequential art — art that uses space to represent time.

[image error]

This work by Sam Bosma tells us a story in that way, in that it tells us a kind of joke, and jokes are stories that introduce but do not resolve unexpected tensions at the punchline. (Incidentally, this is why humor fiction often ends where it begins. A joke isn’t funny if you explain or resolve it.)

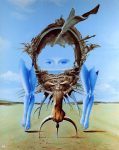

[image error]

To me, this work by Juan Carlos Paz excellently captures parenthood. Not many human children hang upside down and drink their own pee (although I’m sure it’s happened), but when you’re a parent, that’s how it feels sometimes. Also, you’re exhausted.

But look at how much of the “story” — which I read as the humorous destruction of this poor fellow by his offspring — is captured in the detail. We immediately recognize the two figures as adult and child based on their different characteristics. The one is larger and bears the marks of maturity — the horn and the heavy brow.

Then there is the brilliant contrast between the subjects and their almost photo-realistic environment. I imagine parents of young children feel this way often. Not only do they subsist on a steady diet of children’s TV, which features cartoony creatures like this, they are surrounded by toys and often are a toy to their kids. And yet, the world around them is still the “real” adult one. I think this feeling is what they are getting at when they tell a friend how nice it is to have an adult conversation.

[image error]

But comic art isn’t alone in its desire to tell a story. Pulp art (which includes things like book covers and editorial illustrations) is meant to function in the same way, and I realized that’s probably why both of those forms are so popular and why I like them so much.

This is Tom Lovell’s “The Occupation of Paris.” I’ll let you decipher the story.

[image error]

But the true masters of storytelling in art are advertising and propaganda, where propaganda is simply political advertising. And again, it’s the tiny details that both reveal and subvert.

When you see an advertisement, including (especially) a political advertisement, you are reading a story. You are being given a narrative. There is a clear protagonist and a clear antagonist and a pair of changes in time, one that’s taken place in the past and one that must take place in the future: buying a car or a breakfast cereal or voting for the Democratic Party.

You the viewer are recruited to be part of that story. Indeed, you’re told it can’t be resolved without you. You are the aid to the heroine. You are the heroine.

This effect reaches its peak with the game advertisement, which urges you to be the hero to yourself by purchasing a product in which you can be the hero yourself.

(Slay the beast of your thirst with Rainier Beer.)

[image error]

The difference between a beer or game advert and political propaganda, however, is that there’s no sense that the game world has any relation to the real one. In fact, video game companies go to great lengths to convince you their product isn’t anything like the real world, for what they are offering is an escape from it.

A political narrative, on the other hand, is supposed to mean something. It’s supposed to represent the world as it essentially is, even if that’s not how it actually is — in other words, a fiction truer than reality.

[image error]

August 9, 2018

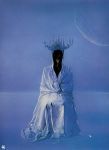

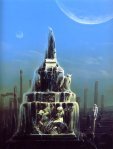

The Otherworlds of Wojtek Siudmak

Wojtek Siudmak (b. 1942) is a highly prolific Polish sci-fi surrealist painter, primarily of book covers and album art. Across the last 50 years, he’s produced staggering number of works. In fact, if you’re a reader of science fiction at all, then you’ve surely seen his paintings before. (The Internet Science Fiction Database has a fine catalog of his book covers and interior art going back to 1970.)

Siudmak’s style is comfortably in the “sci-fi surrealist” tradition, similar to the Dutch painter Karel Thole. His fantastic, otherworldly, often godlike subjects stand on broad planes or other expanses which give his covers a sense of depth and space appropriate to the subject matter.

August 7, 2018

(Fiction) The knife that killed Albert Gallagher twice

We descended into the bowels of the Keep of Solomon, running at full speed. If it hadn’t been so labyrinthine, with stone platforms and passageways erupting from each other at oblique angles, we might have been caught. Several of The Masters appeared, one at a time, at various turns, and I pulled Etude right and left as we scurried downstairs and through dark halls deeper and deeper into the castle, not stopping until we stood amid the arches and columns at the very bottom of the library, holding the whole of it aloft.

“What is this? Now we are trapped!” He glanced nervously behind.

“I thought you were a shaman,” I said.

“Of course! I don’t see—”

“Then you can lead us through the shadow realm, can you not?”

“Through? Yes, but the veil must be pierced. I do not have my drum or flute. We have no ritual fire, no fall of water, and I do not know the spirits of this place.”

“But I do,” I said.

I nodded to the darkest, lowest arch, where a maid’s pale face, and nothing else, was barely visible in shadow for only a moment before it retreated completely.

I suspect she had come and gone so many times through the barrier, the veil between our world and the shadow-place, that it had been worn thin under that arch, but that is mere speculation. All I know for sure is that Etude and I passed through it as easy as through a curtain. He took my hand and with a silent look made it clear I should stay silent as well, and also that I should not let go.

It would take a thousand pages to describe what we saw. It was like walking for hours through someone else’s dark and anxious dreams, and he navigated it as only a spiritwalker can, a man trained since birth not only to battle evil spirits but also to retrieve the lost souls of the sick. We emerged some time later in a church across the Adriatic, in a small town in the Alps above the city of Milan. We gave the parish priest quite a fright as we stepped from the gap in a marble ensconcement at the back of the sepulcher. The clock tower in the square outside made it clear we had covered not only distance but time. It was then several hours earlier than when we had left. He had done it intentionally—to give us a head start. It was odd, I told him, to think that right then, the two of us were also standing in the grand hall before the High Arcane. Could we not go and alter events, I asked, and he said no, that it was impossible to exit the shadow realm at any point whatsoever. He explained that no matter which path we took from there—train, automobile, helicopter—we would not be able to reach the Keep of Solomon one moment before we left, and so the paradox was always avoided.

“Such is the nature of space and time,” he said.

An older gentleman, a head shorter than me with long sideburns and a derby hat, shuffled by and made a face at our clothes, and again at Etude’s bare feet.

“I have heard that time is also money. Perhaps you could find a way to render it so.” I lifted the legs of my cotton pants. “We need new clothes. We look like cultists in these outfits.”

“Really?” He looked down at his shirt. “I rather liked them.”

We were in Bergamo, in the foothills of the Alps. Like most Italian towns, the three- and four-story buildings were all of a similar design and they lined the streets on both sides without gaps, as if forming the walls of a maze whose paths were never straight. The avenues all bent slightly and at odd times seemingly for no reason other than to make them away from you such that you never quite knew where you were. It was a world unto itself and made to be so. It existed for the people who lived there. We found a quiet nook off a blind alley too narrow for cars to pass. There, after a brief meditation, Etude called upon the animals of the city, not just rats and pigeons but kestrels, blackbirds, red foxes, bright finches, mouse-sized bats, feral cats—even wall-climbing lizards and a handful of frogs who hopped out of gutters and from dark pipes that fell from the rooftops. He asked them if they knew of the shiny metals and bits of paper that the humans valued, and they said yes. He asked if they might bring them, and they agreed. They seemed quite eager, in fact, for no one had bothered to talk to them in a very long time.

A brown rat the size of a small dog was the first to reappear. It walked headfirst down a drain pipe carrying something in its teeth. It dropped it on the ground near Etude’s bare feet. It was a silver ring, quite large and heavily tarnished, with swirling bands at the top that held in place a sapphire of at least ten karats. Etude bowed to the rat and introduced himself and me. The rat was a kind of wise man and he told my friend he had come as soon as he heard, for it was rare anymore for people to honor the old ways. He said that under the city many babies were starving, and Etude promised to knock over a rubbish bin near the river, which he did on our way out of town. The wise rat thanked him and left.

On and on it went like that. An animal appeared bearing a small treasure, something lost in the cracks and sewers of the city, and asked an equally small favor of the shaman, which he happily obliged. Most of the requests were quite simple. A kestrel had some plastic netting caught on its feet and tail and asked that it be removed, which I was happy to do. She left us a single diamond earring. A mother cat with Gucci collar and name tag brought a snarling kitten, a child from a recent litter—a matted, angry little menace of a kitten that her owners had discarded. The mother had rescued it and kept it in secret, but it was a nasty thing that bit her and refused to eat.

The young shaman wasted not a moment. He lifted the tiny terror by the scruff of its neck, and it hissed and tried to bite him, but he merely moved his hands over it and spoke in a low voice. Even animals can be possessed, it seems. When the spirit was mesmerized, Etude passed his hand through the kitten’s body and brought it out in a closed fist. He whispered words to his fingers, then opened them and blew, and black ash scattered on the breeze. He returned the tiny kitten, now mewing plaintively to its mother, whose gave us her owner’s gold money clip, stuffed with neatly folded bills.

Before long, there was a line of animals stretching around the corner, and I felt like Etude and I were royalty, receiving gifts and entreaties from our noble subjects. We were polite to them, and they were polite to us. There was much bowing and speaking of ancient oaths. Soon, as word spread to the wilds that a true shaman had appeared in the city, all semblance of order was dropped. As their numbers grew, the animals took to frenzy, agitated to excitement by the mere chance to see the strange bald man who remembered the old ways, when men and beasts were neighbors. Birds of all stripes and colors swooped into the alley and dropped prizes. Bullfrogs croaked and hopped laboriously forward amid a tangle of rats and mice and more than a few voles who scurried back and forth so quickly that it was very hard to see them. Each deposited before the feet of the shaman the shiny detritus of the city—metals and papers and strange cut rocks.

As the animals swarmed, the pile at Etude’s feet grew, and he raised his arms in thanks. And so he stood amid the chaos, hands high, like the barefoot conductor of a great pastoral symphony. And then, just like that, it was done. Etude brought his hands down and the animals scurried away in all directions and we were alone.

The pile we had amassed was nothing short of amazing. There were rings, bracelets, necklaces, loose gems and pearls, earrings, cash, and coins. Quite a bit of the jewelry was costume, of course, and amid the coins, I found several bottle caps, a penny slug, and some brass tokens to various laundromats and arcades. There was also a dog’s tag, three key chains with keys still attached, and a ring fashioned from a nail. The birds had snagged a handful of restaurant receipts, presumably mistaking them for cash, including one bearing a freshly written phone number next to a hand-drawn heart. They had also pilfered someone’s grocery list and part of a newspaper crossword puzzle, all in Italian.

Even still, by the time the symphony reached it sudden climax, enough had been delivered to fill a small chest. It was a genuine treasure. I had never seen a treasure before. Etude knelt and thrust a hand into it and lifted a full fist. Gold fell from between his fingers and clinked on the cobblestones.

“Will this do?” he asked.

I nodded meekly.

It took us some time to gather and sort it all. The crown jewel was an emerald necklace that I was certain dated to the 18th century. There was also a casino chip worth ten million lire and a Roman-era coin that we would later sell for a sizable sum.

“This this looks old,” I said, raising another coin from the pile. I held it up.

It was about the size of a silver dollar and irregularly circular. The markings, as well as the faces that had been stamped onto both sides, were worn with age. Etude went pale when he saw it and cursed softly in his mother tongue, a language I rarely heard pass his lips.

We would later discover it had been lost by an American GI during the liberation of Italy. His name was Albert Gallagher and he had wagered it in a card game against a fellow serviceman. Although no one knew it, Private Gallagher regularly cheated at cards using magic. In fact, he hadn’t lost a single game the entire war. Private Gallagher met his match, however, in a man from a different regiment, a mizzen from New Orleans named Paul Remi. Facing the prospect of losing everything, Private Gallagher played the penny. He was certain he couldn’t lose, for he knew there was no magic that could overturn it. But lose he did, to a seven-high straight, and after carrying that coin across the whole of North Africa and through seven near-death encounters, he watched it walk away in the pocket of the smiling Cajun, along with all his cash.

It was only later, after he was sober, that Private Gallagher realized the mizzen had cheated—but not with magic. Or at least, not only with magic. For Gallagher had also cheated with magic, which meant the mizzen had cheated with sleight of hand as well. He must have. There was no other explanation. Albert Gallagher was furious—furious that he had been beaten with parlor tricks, with the lowest form of false art, and when finally he found Corporal Remi, they quarreled and Private Gallagher was killed. He had already spent the Moirai penny, you see, and Fate makes no allowances for unfair play. In trying to take it back, to retrieve what he had spent, Gallagher’s luck reversed, and he slipped and fell on his own knife—the knife that killed Albert Gallagher twice.

As it happened, the man who died that day in Italy, the day the coin was ripped from a pocket and lost down a gutter, was not the real Albert Gallagher from Ames, Iowa. The real Private Gallagher, aged 20, had lost his parents and two brothers to various unfortunate circumstances through the years and when the war broke out, felt that volunteering was the best way to honor their memory. However, before reporting for duty at an army base outside Mobile, Alabama, the young recruit thought he might see some of the country he was pledging his life to preserve. He hitched south and one night found himself playing a swell game of cards with some fellas in back of a service station. The men were smoking and drinking and shared stories of their lives. The young and inexperienced recruit let slip he was alone in the world—an innocent admission, but one that sealed his fate, for it meant there was no one alive who could identify him.

After the card game, Albert went to relieve himself by a tree, where one of the other players snuck up behind him and slit his throat with the knife. His body was buried in a bog, but not before his uniform and papers were taken. So it was the man who reported for duty in Mobile was not Albert Gallagher from Ames, Iowa, who knew nothing of magic, but one Wilbur Tuesday, aged 28, who was then wanted by the law in eight states.

To keep him safe in wartime, his teenage wife, Livonia, who loved the violent, reckless Wilbur as nothing else in the world, gave her husband a gift, something she had stolen from her mother. She gave her Wilbur a silver penny, which she had been instructed not to touch. She gave it to her husband along with similar instructions. He was never to spend that penny nor even let it fall from his person lest grave things happen. Of course, once Livonia’s mother, an old-timey witch from the hills of Tennessee, discovered it was missing, she had words with her daughter. The two fought, as mothers and daughters do—but also not as mothers and daughters do—and one of them wound up in the corn field.

Etude took the penny from my hands without a word.

from Bright Black, the fifth and final course of my forthcoming occult mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS.