Rick Wayne's Blog, page 105

July 18, 2014

Two-Chapter Sneak Preview of "The Minus Faction" Episode Two

THE MINUS FACTIONEpisode Two"Crossfire"

T Minus: 038 Days 15 Hours 18 Minutes 51 Seconds

The Disemboweler stroked the child's head and smiled from under his severed mask. He had cut it in an arc under the cheeks to reveal his mouth and the tip of his nose. It obscured everything else but his eyes, which were black and soulless. Like a shark's.

The mask was reptilian—once a crocodile or snake—but its painted green scales were dirty and scuffed at the ridges. Like its owner, it was disfigured beyond recognition. It was a horror strapped to the man's head by a cracked and frayed leather belt.

"There, there," he told the little girl.

Her white eyes shone up at him. Her skin was jet black. She clutched a striped short-haired cat.

"See? No need to be scared." The big man squatted next to the pigtailed child and patted her head. He held her arm with one hand and took the cat with the other. He lifted it and the two beasts stared at each other. "What's his name?"

The girl didn't answer. She was terrified, as were all the residents of Figtree Cove. They stared in silence from under the Bagassa trees or fanned themselves under the equatorial Sun. Only the insects chattered. Boraro the Disemboweler had earned his epithet thrice-over—at least—and no one dared challenge him, not even to spare an innocent.

Boraro, still squatting, stroked the cat and addressed the dozen or so members of his audience. "We are looking for Xana Jace."

Everyone knew "we" meant Mama Enecio, almost certainly watching from behind the tinted glass of the Mercedes idling on the dirt road. Mama was a big woman and kept to air conditioning. Three more of her men stood around the car. They held machetes and stakes.

No one spoke.

Boraro smiled again at the child. His dark eyes danced under the mask as he stroked her best friend. "Do you know Xana?"

The child nodded.

"Do you know where she is?"

The girl shook her head. She stared at her purring pet and looked as though she were about to cry.

Boraro scowled. He disliked children. They were loud and unreasonable. Only good for one thing. And it wasn't time for that.

Yet.

He waved his hand for her to leave and she ran across the dirt and grass to her mother, who waited in front their dilapidated shack. Of the seven so-called houses that rimmed the cove, two were leaning so heavily as to be uninhabitable. The water behind them filled a deep depression in the ground, runoff gathered from a tributary of the Demerara River. Figtree Cove was nearly dry for three months of the year, a muddy depression that fed flies and mosquitoes. The rest of the time it served as bath, fishing hole, and irrigation well for the tiny community.

Boraro stood tall in the sun still holding the lazy feline. The man's dry, scaly brown skin was covered in fine black hairs. He wore a plain t-shirt and work pants. His long legs ended in mud-caked boots. His heavy arms sprouted from his shoulders and bulged like twisted-steel cables. His hands made fists like club heads.

"I have a message. I want you to give it to the freak Xana." He rubbed his fingers back and forth over the cat's ears. The animal closed its eyes. "Tell her I will face her tomorrow under the noon sun. One on one. In the junkyard by the Dutch market. Tell her, if she does not come . . ." He swept his hand across the scene. "We will burn every one of these houses to the ground."

The crowd stayed silent.

"Tell her she cannot run. Tell her." The Disemboweler grabbed the cat's head and twisted. The animal squealed and went silent. The crowd gasped. The little girl hid her face in her mother's faded dress. The woman put a hand on her daughter but said nothing.

Boraro ripped the cat's skull from its body. Strips of torn skin stretched like taffy. He tipped the head over his open mouth as if drinking from a coconut. He swallowed blood. A dribble ran down his throat. He tossed the head to the dust and yanked the cat's fur to reveal it's muscle-covered ribcage. Boraro cracked it with bulging arms and pulled out the animal's heart. It looked like a juicy plum in his fat fingers. He tossed the carcass to the ground and took a bite from the organ. Red liquid squirted and drained over his fingers like juice. Many in the crowd turned away.

The masked man chewed. His reptilian cowl moved up and down with each clench of his jaw. Then he motioned his men forward. They walked toward the closest shack and everyone saw. Those weren't stakes in their hands. They were torches.

"No!" A skinny, shirtless man stepped forward.

One of Mama Enecio's men knocked him down and kicked him as another lit a gasoline-soaked torch with his Zippo and tossed it into the closest shack.

The skinny man put his face in the dirt and covered his head to hide the sobs. Everyone else watched as flames rose and surrounded the door frame.

Boraro swallowed the last of the heart and wiped his hands back and forth on his pants. He watched the flames grow. Dry, sun-baked wood crackled and snapped. In moments, the shack was an inferno.

"Noon," the Disemboweler repeated. "Or I will come back hungry." He waved to the little girl. Then he turned with the others, walked to the car, and drove away.

T Minus: 038 Days 09 Hours 57 Minutes 12 Seconds

Xana Jace stood seven feet four inches tall and avoided everyone she could. To most of the people who knew her, she was a nuisance. To everyone else, a monster. Certainly she looked the part, with a heavy brow, a stout jaw, and a thundering gait.

But Xana wasn't a monster. She was merely host to one. It had first appeared as a tiny bulge from a gland in her head, half the size of a pea. It secreted something, like a whisper to her cells telling them to grow and grow.

And grow.

Apparently it wasn't enough for the monster to choke her heart with a mass of muscle and send her to an early grave. Apparently it had to deform her first, to turn her into her own reflection in a bulging mirror.

Xana looked down at her hands, like a man's. Bigger. They were dirty, calloused, and cut. She hadn't had a manicure in seven years.

But who was counting?

She wiped them on her military surplus t-shirt and looked across the vacant lot. A three-meter-wide pile of refuse flaunted the "No Dumping" sign staked to the ground. The South American sun burrowed into everything from above. Across the street, a large crowd loitered in front of the old Royal House, now a stale collection of legal offices. It was a protest, or what passed for one in Guyana. With too many men and not enough work, there were always people angry about something. Hand-lettered signs rested on the ground or against palm trees while their owners smoked and sat and waited for an audience.

Xana knew how it went. As soon as someone important-looking appeared, the men would jump to their feet and hoot and holler, as if called to cue by an invisible director. Even the uniformed policeman, sitting on a broken concrete block, would join the show. He'd drop his cigarette and jostle with loose arms, pretending to hold the crowd at bay. It was an act. Usually.

But then Xana's cousin Weke had been killed in a mob when she was seventeen and he three years younger. She couldn't even remember what it was about. Weke had been beaten and trampled. Xana had seen the body after.

She bit her full lower lip and watched from the cover of a banyan tree. She didn't like crowds. She was not particularly well-muscled, but her size coupled with her gender were a threat to angry young men, especially those emboldened by each other's presence. And there was at least one machete in the throng.

But there was no way around. She'd have to risk it. She stepped from the shade.

"Here for the big show?"

Xana knew the voice. The American woman. The reporter. Abi something. She came through the little grove of overgrowth that separated the abandoned lot from the street.

Xana didn't turn. "Don't talk to me." A hot breeze blew her heavy, tangled curls in front of her eyes. Xana's wild hair was all that remained of the scrawny, wide-eyed girl of her youth. It was unmistakable, not least because it was a lighter brown than her skin. It had turned more than a few heads. Before.

Xana stared at the crowd as she pulled her wild hair back and affixed it into a bushy tail behind her head. It required constant care. If left untended for more than a day, it pounced from her head like a jaguar.

Abi smiled. "Every time you talk I expect you to sound like Andre the Giant."

"Who?"

"How's the foot?"

Xana stepped away, revealing her limp. Her right foot was mangled. She hid it inside her custom-ordered heavy work boots. "It's fine. Please leave me alone."

"I'm not your enemy, you know." The American followed past the pile of trash. She was tall, although nothing like Xana, and skinny with bony cheeks, a big nose, and sharp brown eyes. Her thin lips covered big teeth. Once straightened by braces, they had started slipping crooked in her 30s.

"That doesn't make you my friend."

"I never said I was your friend."

Xana turned and stopped. "Yes, you did." Then she kept walking.

"Right. Forgot about that. Sorry. I didn't think people would respond how they did."

"We can agree you didn't think."

"It was an honest mistake."

"This isn't America."

"What's that supposed to mean?"

"Stop following me."

"Will you please stop for just a second?"

Xana turned.

"Aren't you curious why there's a protest in front of your lawyer's office?"

"Mr. Rehnkist will know."

"You trust him?"

"He's my attorney."

"That's not what I asked."

"He's the only who stands up to the McDooms."

"He's not the only one."

"Don't flatter yourself. You report on them. There's a difference."

"It's because Feathers is in there."

Clement Feathers was the McDoom family attorney and a shark. Xana noticed the Mercedes parked down the street next to a row of palms.

"They're protesting the labor remission?"

Xana scowled. "The what?"

"You don't want to go through that crowd any more than I do."

Xana looked again at the listless young men. Some paced. Some sat on the off-white steps leading up to the veranda. The paint on the wood was cracked and chipping.

"There's a back door, you know—a walkway from the courthouse. Underground. The British built it in the colonial days. All linoleum and fluorescent lights now. But you'll need my press credentials to get you through security."

"I don't want your help."

"I know. But I guess I owe you. I have a son, too, you know."

"Then why aren't you with him?"

"It's a long story."

Xana looked at the crowd. They were lean. Hungry. "This doesn't mean I forgive you."

"Of course not."

Xana walked through the grove of trees, across a cracked asphalt road and onto the back lawn of the municipal courthouse. She stayed ahead of the reporter. Siegel. That was her name. Abi Siegel.

"Say, can I ask you something?" Abi had to walk double-time to match Xana's stride, even with her limp. "What are you going to do about Mama Enecio?"

"What about her?"

"She's a hard problem to shake."

"I stay away from gangsters."

"What about the fire this morning?"

Xana stopped on the grass. It was spotted in dead leaves and fronds from the line of tropical plants the rimmed the square. In the distance, the ocean. "What fire?"

"You haven't heard?" Abi looked Xana in the eyes. They were high. And striking. Like the woman's hair. "Really?"

"What are you talking about?"

Abi kept walking. "Talk to your lawyer. Then you should go home."

"Wait a minute." Xana walked after her. She grabbed the reporter's arm. "Wait."

"Don't touch me." The American pulled free. "I don't like people touching me."

"What fire?"

"Boraro and some of his goons made the drive out to Figtree. That's where you're staying these days, right?"

Xana nodded. It was a temporary arrangement with her cousin until she could get back on her feet. All the money Xana made working the graveyard shift went toward legal fees, toward getting her son back. It was all for AJ.

"Come on." Abi walked to the back door of the courthouse. The door creaked. A small security station rested at the bottom of a half-flight of stairs. The building smelled of dust and paper. The American flashed her credentials to the lone guard and nodded at Xana. "She's with me."

"Wait." The guard stood and raised his baton in front of Xana. "Turn around." He frisked her and lingered on her inner thighs.

Xana didn't flinch. She stared at the door.

After the groping, the pair walked down a long hall covered in weathered vinyl. Fluorescent shone overhead. The light was insufficient.

Abi turned. "Why do you let people do that?"

"Do what?"

"Push you around like that. You had two feet on that guy, and probably a hundred pounds."

"He's a policeman."

"So? Push him out of the way. This is Guyana. He's not going to say anything. And no one would care if he did."

"Malcolm McDoom would care."

The reported sized up the giant next to her. The tips of the woman's wild hair brushed the lights overhead. She looked so out of place. And that face . . . "You don't have any idea what Mama Enecio is after, do you?"

Xana shook her head.

"Or why she's got Boraro looking for you."

"Boraro?"

"The Disemboweler." Abi made quotes in the air.

"I told you. I don't know what you're talking about."

Abi stopped. She pointed down the hall to the stairs. "It's just up that way. Up the stairs. I hope Rehnkist has good news for you."

Xana watched the reporter walk back the way they'd came. That was quick. She was a huntress. She was after something. Xana wanted nothing to do with it. She walked up the stairs to the third floor, down the hall, and into Arthur Rehnkist's office. The man was in the next room with the door closed. He had no secretary and no windows. The walls were covered in faux-wood paneling to half their height. The rest was a faded lime green.

Xana sat and waited. She looked again at her hands. She made fists as a clock on the wall ticked seconds. Xana had been a pretty girl once, if a little scrawny. She started growing at puberty and never stopped. By her early 20s, when she passed six feet, it was clear something was wrong. That's when she went to the free clinic. That's when they told her about the monster.

The same thing that was killing her had also cost her her son. It wasn't just a pituitary tumor, they said—whatever that was. There was a defect, somewhere deeper down, inside the stuff that told all the other stuff what to do, in the code for a particular kind of protein. It made her muscles grow like tumors. Denser. Different. Her bones would thicken as a result of the increased strain, or so they said. But since muscle grows faster, the one would out-pace the other, and Xana would suffer fractures if she exerted herself. Her own body would break itself. And it had.

Eventually, they said, it would all exceed the capacity of her heart, which would explode in her chest. Best not exert yourself too hard. Best to stay calm.

She was almost 30. She'd be lucky to see the next decade.

Clement Feathers emerged from the next room and walked into the hall. He didn't acknowledge the big woman. He didn't look at her. He just walked right past. That was fine with Xana.

Rehnkist sat behind his desk. He was old, just like everything else in Royal House. His dark skin was wrinkled. He had lost most of his hair. The remainder was white. His suit didn't fit well.

He waved her in. "We have a few things to talk about."

"Did the judge rule on the motion?" Xana walked in and closed the door.

"We'll get to that." Rehnkist motioned to a chair. His hands shook. "That reporter came by earlier. The American. The one who wrote the story last year."

Xana nodded. "I saw her."

"That was a bad bit of business. I always wondered how much that contributed to the accident. But I never wanted to ask."

"What did the judge say?"

"Also, you got another encrypted email from your mysterious admirer. How many does that make now? Four? Five?"

"Four. Just delete it. Please."

"What are they sending you? If you don't mind me asking."

Xana shrugged. She wasn't sure how to describe it. "Stuff. Information. I don't always understand."

"Why you?"

"He wants me to do something."

"He?"

"The prophet." Xana stared at the court papers on the desk. "The judge said no, didn't he?"

"We knew that was a possibility." Rehnkist wouldn't make eye contact. "The situation with the car--"

"I thought you said he understood." Xana never saw the judge. Arthur said it would be better.

"He understands about the accident. I meant that living all the way out at Figtree Cove and with no car, you're having trouble with steady employment, which was a condition for reinstatement of visitation."

Xana had gotten frustrated with the jalopy she'd purchased. She'd spent all the money she'd saved working nights at the sugar plant. She hardly saw her son. But the job was a requirement for her retain custody. And the car was a requirement for the job. When it just stopped running, she knew she'd been taken advantage of. Again. Xana wasn't a clever woman, she knew. She felt watched: by the courts, by the McDooms, by everyone who stared at her as she passed. She was going to be late picking her son up from daycare. They only needed one excuse. She'd gotten angry. Why did she have to be so stupid? Why had she trusted the salesman?

Xana kicked the little car as it rested on the side of the dirt road. She kicked it with all her might. For anyone but Xana Jace, such an outburst would have resulted in little more than a stubbed toe and bruised pride.

For anyone but Xana Jace.

She tore the front of the vehicle and flipped it on its side, wrecking it and nearly injuring two pedestrians. She'd shredded most of her right foot, tearing through her shoes down to the bone, leaving her with a mangled stub, a persistent limp, no job, and no AJ. It was the perfect excuse for a wealthy, connected family to convince a judge.

Unfit, they said. Violent, they said.

Just look at her, they said.

"I haven't seen AJ in almost two years. How can they just keep me away? I'm his mother."

It hadn't helped that the story in the papers, the one by the Siegel woman, had cataloged her accidents like a shipping manifest. Xana was still growing. Her body had never stopped. She fumbled inside herself, a stranger in her own flesh. She hit her head on door frames and knocked over furniture. Children stepped closer to their parents when she appeared. She was training herself to force a constant smile. Without it, her heavy brow and prominent jaw lent her a persistent diabolical scowl.

But the smile, when she remembered it, always seemed so fake. Like she had something to hide.

Rehnkist raised his hand in the air above his desk and held it. His mouth hung open for a moment. "That's not the worst of it, I'm afraid." He lowered his hand on the desk. He glanced at his client and looked away. "The judge overruled the motion on grounds of inadequate jurisdiction." He looked at Xana for a reaction.

She was confused. "I don't know what that means."

"It means the judge doesn't have the authority."

"But how?"

"Because AJ is no longer in the country."

Xana froze. Her heart stopped. "Wha-- what? Where is he?" She stood.

"Calm down, Ms. Jace."

"No! Where is he? Is he okay? Where is my son?"

"America. New York, I think. Mr. Feathers's rejoinder didn't specify."

Xana paced in a circle. Her eyes clenched in tears. America. She could never get to America. "But how can they DO that? How can they just-- just--"

"Declun has legal custody. Once your visitation rights were revoked, AJ's residence was no longer a matter for the court."

Xana was crying. "But he's my son."

"I know. It's a terrible crime. But unfortunately, strictly speaking, it's not illegal."

Xana stood in the small windowless office and held her face in her big hands.

Arthur listened to her sob. He could tell she was holding back as best she could. "If it's any consolation, they sent him to get an education. Or so I'm told. Feathers wouldn't say where of course, but they wanted you to know it's a very fine private school that will prepare him for college."

Xana didn't respond. He'd be alone. In a strange country. He wouldn't know anyone. He was only seven. He'd be so scared.

Declun's family hated Xana, she knew. To them, she was a mongrel, an "untenable" mix: German-Argentinian on her father's side, some native blood, some east Indian, even a little Hispanic through her mother. She was a mutt. It was obvious. Just look at how her body had rebelled. And they were the McDooms, one of the oldest families in Guyana. They owned the sugar plant and a great deal of property overseas. They even had a village named after them. Xana passed the sign every time she went into town. It was a constant reminder.

Rehnkist pulled an envelope from a drawer and set it on the desk.

Xana knew what it was. A bill. She grabbed the little cross that hung around her neck. It hung under her shirt, and the cotton bunched in her hand. She felt the tips of the cross poke through to her skin.

The lawyer cleared his throat. "Are you sure you don't want to read that email?"

Xana shook her head. She grabbed the envelope from the desk and walked out. She walked down the hall in a daze.

AJ wasn't across town. He wasn't at his grandparent's summer retreat in Aruba. He was in America.

America.

Xana walked out of Royal House in tears. She forgot about the protest until the doors were open and she was standing on the off-white veranda. But the men were gone.

Xana was alone.

July 11, 2014

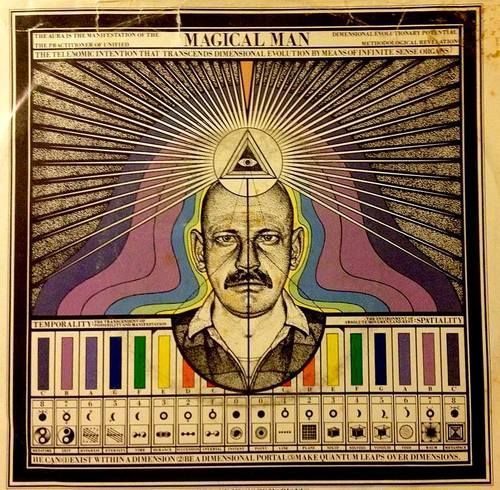

The Weight of 10,000 Rainbows: Thoughts on Turning 40

We each know more than we can say. There is a certain elusive "what it's like"-ness to human experience that is nearly impossible to utter. After all, our consciousness, while not ephemeral, isn't exactly tangible either. How would you describe it to an unconscious yet thinking machine?

"The inside of my head feels as wide as the sky and is filled with 10,000 rainbows."

Philosophers call the ineffable "what-it's-like"-ness of experience qualia. The classic example is the redness of an apple, which is something over and above the wavelength of the photons striking your eye or the stirring of electrical impulses in your nerves. A cascading voltage potential is NOT joy, or pain, or humor, but it mediates those things just as air molecules carry sound or radio waves carry music.

Consciousness then is a froth, a persistent emergence from the many minuscule implosions and rarefactions of the brain. And as your brain goes, so goes the mind it creates.

In a few days, I will turn 40. I am not upset by this. Birthdays are fun, and you can do nothing but ruin the moment by dwelling on the grand ebb of your existence. Another year has passed and you're still alive. Fucking enjoy it!

The closest thing to a middling life crisis came for me on my 29th birthday. Staring at the end of my third decade, I felt beguiled by life, like it had tricked me, like I had awoken into a Pink Floyd song. No one told me when to run! I missed the starting gun.

So I went and jumped out of an airplane. Not bad as celebrations go. Certainly I got what I wanted: an explosion of life-affirming feels. It was amazing, not least because at 29 there was no difference between having a life and being alive.

Being alive is the medium of an intangible something -- we call it a life -- in the same way that air is the medium of sound and brains are the medium of minds. A life is an emergent property of the persistent act of living. You just can't see it.

The other day, my family asked me what I learned in forty years. I couldn't answer. Yet my head was filled with the "what-its-like"-ness of having a life, something I did not have before. It's a sensation similar to the feelings stirred by an old song: you know it when you feel it but it's never quite articulable -- a tiny cut on the roof of your mind that you just can't quite reach with your tongue.

At 40, I have a sense of what it's like to have a life, and not just to be in possession of one, but of what you can and can't do with it, of the particular shape and peculiar flavor of my own, of its finiteness, of what will and won't fit inside, of its infungibility, of its misapplication, of its terminal condition -- which is all entirely different than the feeling of being alive.

Unfortunately I have no particular gift for expressing that sense, and so I can't communicate to you what I've learned. Like the taste of that old song, it's something best left for poets, which I am not.

Confucius said, "At fifteen my heart was set on learning; at thirty I stood firm; at forty I had no more doubts; at fifty I knew the will of heaven; at sixty my ear was obedient; at seventy I could follow my heart's desire without overstepping the boundaries of what was right."

Perhaps that's what he meant by no more doubts, that he'd finally got a handle on this life thing and now it was just a matter of becoming an expert. I don't know. What do you think?

I can only say this: whatever else it is, life is fucking short. Live it such that at the end -- be that 45 or 90 -- you can bear the ineffable "what-it's-like"-ness of your 10,000 rainbows to your own satisfaction.

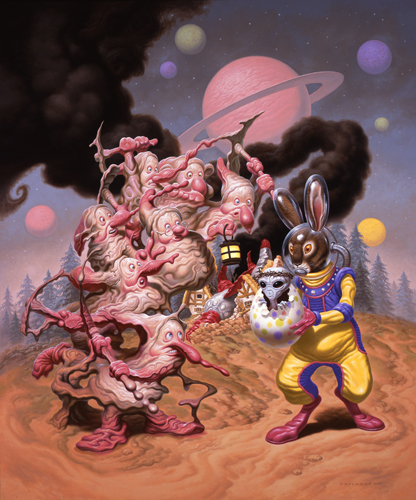

Todd Schorr

June 30, 2014

Pregnant with Miracles

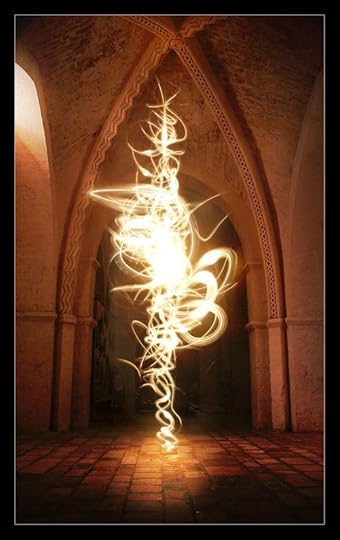

A door is a mystery.

A door is a journey, an adventure.

A door is a permeable barrier.

A door is hope--a way out.

A door is terror--a way in.

A book is a door to another world, and as a writer, I have an unhealthy fascination with doors and thresholds.

When I was younger, I was enamored of the sciences. I liked knowing. It seemed there was plenty of uncertainty. Knowledge was an island in dark, raging seas. But as I get older, I chafe under the fascism of Truth. If an island is a refuge, it is also a prison. Just ask any castaway.

I prefer not to know. I prefer to discover.

It's at borders where tangents play and disrupt the sine wave, where people and ideas mate and make mutants. Most theories of the origin of life suggest it emerged through a threshold, at the margins of the land perhaps, or in a crack in the crust deep below the waves, like the labia of mother earth, where her vital energy of pours forth.

A crystal grows from the edge. Light emerges from the tips of the Sun. A womb is an occult barrier pregnant with miracles.

So much called knowledge passes just as each of us, at every moment, stands on the threshold of the future. Wisdom is not facts but understanding. It is meta-knowledge--an unmeasured appreciation of fluid properties.

If the past is another country, one checks one's passport at the border of history. It's not so much knowledge of the past as the journey through it that brings wisdom.

The transition -- the experience -- is where growth occurs, where new yous are born. Knowledge, or what passes for it, is a monotonous limestone sediment distilled from the ocean of others' experiences. It is not your own.

But the crossing of a threshold IS experience.

The opening of a door is not life. It is living.

The art of life then is whether and when to open it.

Thresholds (an escapist's daydream)

June 1, 2014

T Minus: 051 Days 04 Hours 12 Minutes 28 Seconds

John lost his best friend in Suriname. He left Danny’s body in a ditch after shooting him in the head. Danny looked up at John with no fear, no remorse. He’d been caught. John had orders. Danny would have done the same. He was on his knees with John standing over him. They’d fought. Danny was good. But John was better. John didn’t have a wife, didn’t have a family he’d leave fatherless, didn’t have kids he was trying to put through college by selling out his country. Danny grabbed the barrel of the gun and held it to his head as the jungle rain poured down. Danny was the only man in the unit who knew things about John, personal things. That’s why they sent him. And after the shot, after Danny was dead, John was alone. He ran through the jungle. Seventeen miles. He ran and ran through relentless rain. He cried a little for his friend, but not much, and when he made the extraction point, he put it away forever. For the unit.

John watched as the only woman he had ever loved smiled and said her vows to another man in front of a church full of people. The sun was shining. John’s tux didn’t fit right; it was a rental and he was a big man. He felt like an ass and a liar standing up there in front of everyone pretending to be happy. But she wasn’t pretending. The couple laughed and danced into the night. John never told her how he felt. She never knew. When he was finally alone in his hotel room, John cried, and then he went for a dawn run and put it away forever. For his friends.

John was overseas when his sister’s life fell apart, when her husband left her with two kids. Kicked her and them out of the house. Hit her. At least once. John was thousands of miles away doing things human beings shouldn’t do to each other. It was weeks until he got the email. It was just like after mom died. His sister could never seem to escape it. Only now John wasn’t there to look after her. Or the kids. He suited up and went for a run. He ran and ran and ran through the desert, tears hidden by a drenching sweat. And when he got back to base, there were new orders and he put his pain away. For his country.

John was seventeen when his stepmom sent his little brother to the hospital. He stayed with Jojo the whole night. All John could do was scowl in anger. He wouldn’t look his father in the eye. He drove his brother home the next morning and stayed with him until the boy made him leave. John had a game that night. It was the state finals. He was the star. Everyone was counting on him, including Jojo. John plowed over the other team’s defensive line. He ran and ran and ran. He scored three touchdowns. He was graduating in the spring, going into the Army. His brother and sister would be alone with his stepmom. He cried under his helmet before the game. Then he put it away. For the team.

John was in seventh grade when his mother died. She’d been sick for months. She’d been in the hospital for weeks. When the men with the sad looks showed up in English class to take him home, he ran. He ran like his coach had shown him, pushing past the strangers and sprinting down the hall and running out the door and across the parking lot and through the football field and four miles down the road to the elementary school where his brother and sister were waiting. He cried the whole way. But as he hugged them in the parking lot, he put it away forever. For them. Their dad wasn’t a strong man. So John would be.

John hadn’t cried in the caves. He was too worried about surviving. He hadn’t cried on the flight home. He was too happy to be free. He hadn’t cried in the hospital. There were always people around, especially at first.

Do you want anything? More pills? More water? Another blanket? Can I help you wash? Help you into bed? Help?

And there were so many other patients in pain. Some with families, some without. Some with friends, some without. John did what he could. He told stories. He smiled. He made the rounds in his motorized chair. He didn’t have to say it. His appearance was enough.

If I can make it, so can you.

If I can make it.

John sat in his dark hospital room and looked down at his legs, limp and bent, barely fitting in the space between the seat and the footrest. He was a big man, always had been.

They had come, finally. The eyeless suits. The bastards. They were going to take it away. The tiny bit he had left.

He looked at his legs, at his burned and mottled skin.

He scowled and made a fist and punched himself with his good arm. He punched his legs as hard as he could. He heard the sound, but he felt nothing.

A tear came.

He punched himself in the chest. He punched his face. Then again. Then again. It rocked his chair, his fancy new prison, back and forth. He beat on the armrest over and over and over and over until his hand stung worse than the burns.

More tears.

John Michael Regent held up his one good hand in a ball. It shook in silent fury. He bared his teeth. He wanted to scream. But the others would come. He wanted to yell, but they’d just look at him with those eyes.

He clenched his own shut and felt wet dribble down one half of his face.

He was so tired of everyone. He couldn’t take it anymore. He couldn’t.

This would’ve been a night for a run. He always went at night. Nobody was likely to see and no body was likely to be missed. He had stayed up all night for weeks on end studying the nurses’ schedules, their habits, looking for weaknesses, just like he’d been trained. He changed the settings on all his medical equipment and feigned ignorance as the nurses fixed it for him. He watched and learned. He could beat the machines.

His first few nights he just ran and ran and ran, two firm legs striking the pavement in even strides, some other man’s heart pounding. Even a woman once.

That was the night he happened on a mugging. It was an accident, a wrong turn at 3 a.m. He taught the jerk a lesson and handed the scared man on the pavement his wallet back. The guy just stared up at the strange woman in the hood and dark sunglasses—sunglasses, at night—who had leapt down from a roof and beat the shit out of his attacker.

“Those were some moves,” he said on his back, wide-eyed.

The woman had bent the mugger’s leg at the knee and roundhoused him into the wall. Right in the balls. Then she popped him straight up the jaw with the palm of her hand, knocked him out.

She didn’t respond.

The next week, John went looking for trouble. That was how he justified it. Taking the bodies. Taking what wasn’t his. Stealing them. Stealing tiny bits of someone else’s life. They’re not using it, he told himself. And I can do some good with it. I should do some good with it.

So John ran and ran and ran all over the city and all through the night. It felt good. On his third patrol, John stopped a backseat rape. Two months ago he helped a wounded pedestrian, a victim of a drunk hit-and-run, make it to a hospital. Last month he was tutoring a Parkour group in basic self-defense. They were already in great shape. They knew how to move. He was just organizing them, teaching them tactics, things to consider when you happen upon a crime.

He pushed it that night. He stayed out too long. He watched the dawn come up from the roof of a five story building. The little stretch of city before him hung on the outskirts of Philly and was full of working class ethnic neighborhoods and strip malls. He was starting to think of it as his responsibility.

From what he could discern, the police weren’t looking for anyone, or at least anyone in particular. All anyone knew was that there were some helpful citizens about, and the only thing they had in common was the hoodie. And the sunglasses.

But the attack on the drug den would bring them to the hospital. Sooner or later, someone would put the pieces together, find the connection. They’d all been patients at the fancy new VA. They’d all used advanced hand-to-hand. Like what a soldier would know. Regent couldn’t stay. It was too much of a risk now. If he ever wanted to run again, he had to get away. It was already news.

But in trying to leave, his shadowy pursuers had come for him. John knew how it worked. “Ayn” was just the first wave. It was her job to keep him on the reservation long enough for the others to arrive. As his file was chewed by the system, as it triggered automatic flags and warnings, as numbered bureaucrats sipped soy lattes and processed it—processed him—each in tiny chunks, they would summon the dragons.

Men like John.

It didn’t matter if he had done anything. He was on a list. And to any lanyard-wearing case worker who didn’t know him from a hole in the ground, it was always better to be safe than sorry. Advance file to second stage.

So this was it. The beginning of the end of a long, long, legless run. It was all over.

John was ready. He knew the score. He knew it wouldn’t last forever. But he had one last mission to complete. One final objective. And he was going to see it through. John Regent always completed the mission.

No excuses.

John wiped his face with his good hand. He took a deep breath and put it away. For the unborn.

May 22, 2014

The Trick to Borrowing Someone Else's Body is...

Episode One:Breakout

T Minus: 052 Days 17 Hours 46 Minutes 11 Seconds

The trick to borrowing someone else's body is not getting caught.

This is not the same as being seen. You can be seen all day. You just have to give people a single, plausible reason why the man in the hat and sunglasses is not their old friend Jeff who's been in a coma for six months--Jeff had dark hair and no mustache and that guy's mustache is blond--and people will assume it's just someone who looks like Jeff and go right on texting. Or whatever.

The trick to busting a drug deal on the other hand is not getting shot.

On a warm Saturday in April, John Regent failed at both.

According to the Army, the trick to surviving a gunshot wound is to stop the bleeding and get immediate medical attention. This means keeping still and putting pressure on the wound. That's what they teach in Basic training, and it's true.

But then, people who are scared and angry enough to shoot at other people tend to keep shooting, which means you need to keep moving, so the real trick to surviving a gunshot wound is not going into shock. And the best way to avoid shock is prior inoculation: being shot before, preferably multiple times. Like homeopathy for soldiers.

Of course, any normal person would have listened to the armed and screaming drug dealers and simply left. Any normal person wouldn't have gone there in the first place. But John Regent had a job to do, and he had been trained to do not nice things by not nice people. In fact, it was in training that Regent had been shot the first time. Not Basic training. Not Ranger training. Not even Special Forces training, although they feigned it.

It was after that, at the training that had no name for a unit that had no insignia, the training that had no manual and that never, ever took place. Officially. It was the training where John had been drugged, blindfolded, shot in the arm, and dumped out of a helicopter into a swamp by his own instructors and told to find his way back without a map or compass or anything. Oh, and there are guys on the ground hunting you. With dogs. It wasn't until the clouds parted a few hours after the drop that John could see the stars and realized he wasn't even on the same hemisphere anymore, let alone the same continent.

That was Day One of the training that didn't exist. Things got progressively harder from there. But it worked. John Regent was a master of clinical violence.

The trick to hostage rescue is to get inside without the hostage-takers killing anyone. Standing there, bleeding against the door of some asshole's second floor apartment, John was already inside.

See? He told himself. Stop complaining. Hard part is already over.

Of course, it helped that when he wandered, when he was in someone else's body, Regent could control the pain. And the fear. And all the responses--all the shit--your genes saddle you with in their vain effort to keep themselves alive. Riding someone else's bones, John was in total control like he never was, like no one ever was, in their own skin. Even with a gunshot wound, he had total clarity.

The trick to disarming someone is making them to want to drop the weapon, even when they don't want to. There are a variety of ways to do this, but if you're reasonably sure your target hasn't seen combat--this kid looks like a tool, John thought--then a firm strike to the top of the forearm usually does the trick, preferably with something hard. You know the place: where the skin runs thin over the bone and good whack sends a shock of pain to the hand.

The thing about combat is that you do and see shit normal people just don't ever experience in life: throw grenades at strangers, stab someone before they stab you, see your buddy's head explode in a burst of red smoke. That kind of thing. It's a shock some people never shake, people like John's friend Mario. Mario had just finished a tour. Mario was in bad. He was a hostage.

The drug dealers in the room hadn't seen combat. They were barely literate punks. Mean, but undisciplined. They all stood still as the handgun bounced on the floor with a thud. No one expected "Jeff" to fight back, not after being shot, not without a pause for breath.

To Regent's right, asshole number two stood at the end of a couch where a young mother sat clutching her baby. Fuck. No shooting to that side.

To Regent's left, asshole number three already had a hand on his gun. He was twitchy, not afraid to shoot, but he had his pants around his knees, which meant he wasn't mobile.

Three seconds. Tops.

In a single, fluid movement from that which had knocked the gun free, Regent popped Number One in the throat. That disorients. People who aren't used to getting hurt, people who aren't trained to stay focused, think about the pain and--for a second at least--worry about whether or not they're able to breathe. That distracts, makes their limbs pliable.

Regent clutched the kid close, using him as a shield as he walked forward along the couch, pushing Number One toward Number Two while Number Three, the dangerous one, went for his weapon.

Two seconds.

John was an athlete, or he had been once, and he didn't take his eyes off his target. He pushed Number One to the left without turning. The young man, still clutching his throat, stumbled into Number Three's line-of-fire.

One second.

John smacked Number Two in the teeth, grabbed the kid's gun, then swung and went down on one knee--lowering his profile made him a moving target despite that his feet were planted--and shot Number Three in the shoulder. The man's torso turned from the impact and swung the barrel of his gun toward the door and away from the mother and child. He screamed and went down. His Glock slide across the hardwood.

Regent stood and popped Number Two in the gut with his fist. When the kid doubled over, Regent rammed his knee into the young man's nose.

Crack.

That hurts.

Number One, still coughing from the pop to the throat, regained his balance and put his hands in the air. Everyone froze. Regent held Number Two's gun loosely and stood in the middle of the room.

Three seconds. No fatalities. One casualty.

It was clear Number Three hadn't been shot before, let alone seven times.

John looked down at "Jeff's" leg. Make that eight.

Numbers One and Two looked down at the twitchy kid rocking back and forth on the floor. They were waiting to see what he would do. He must be the leader. He was moaning and holding his shoulder.

That's good, Regent thought. Just what they teach in Basic. Stay down, keep pressure on the wound.

John knelt and put his gun to the boy's shaved head. "Hurts, doesn't it?" White people don't look good with shaved heads. Except Captain Picard. John always liked Captain Picard.

The kid grimaced. He nodded.

"You been shot before?"

The kid shook his head.

"Don't worry. It's easier the second time. You know Mario Gonzales?"

The kid scowled. "Man, there's five hundred guys with that name just on this block." He was cocky.

Regent popped the kid in the skull with the butt of his gun then put the barrel back to his temple.

The boy yelped.

"Heavy set. About your age. Was a soldier. Just got back. Buys pills. You know the guy now?"

The kid nodded. "I don't know where he is, man. He just shows up. I don't keep track."

"I'm not asking where he is. I know where he is. The problem is where he should be. Do you know where that is?"

The kid shook his head.

"Back at the VA. In therapy. He needs help. He's got a wife workin' two jobs and kid on the way. But he's not gonna get help when he's hiding inside your pills. So that means you're gonna stop selling to him."

Number Three raised his watering eyes to John.

"I don't care what else you do. I don't care whose life you fuck to make bank. But you and all your buddies are gonna stop selling to him. Corporal Gonzales is off limits. Do you understand?"

The kid nodded, but he didn't mean it.

John moved the gun and shot the sleaze in the knee. Point blank. The bullet ran clean through baggy jeans and flesh and impacted the hardwood with a crack, throwing up little splinters.

The kid screamed. He grabbed his leg with his good hand and rocked back and forth again, yelling and cursing at the top of his lungs.

John put the barrel to the young man's head again. "See? Hurts less than the first one, right?"

The kid was shaking. He didn't know the tricks. He was going into shock. He didn't have long. But there were sirens in the distance.

John pressed the gun barrel hard to the kid's temple. "Convince me, asshole."

"I'll stop! Fuck, you crazy muthafucker! Fuck! I'll stop. He's off limits, man. I'll tell everybody. He ain't fuckin' worth it."

John nodded. "You think you're some kind of soldier, huh? Street war or something? If I have to come back here, I'll show you what war's really like. Am I perfectly clear?"

The kid nodded in pain.

John looked at the other two. They didn't move. The mother--she must be somebody's girlfriend--clutched her baby and looked at the floor.

Regent stood. "What are you doing? Bringing a baby to a place like this."

She was silent. Her eyes stayed down, didn't make contact.

John shook his head and walked out. "Jeff's" leg was soaked red, and Regent stumbled down the stairs and out the back as he rubbed the gun clean of prints. He dropped it and the fake mustache in a storm drain and walked onto the street as the police and ambulances arrived. He laid down on the sidewalk and slowed his breathing. "Jeff" wasn't in the best shape either. He'd lost a lot of blood.

When the medics leaned over him, John said he didn't know who he was or how he'd gotten there. And when it was clear they had everything in hand and "Jeff" was going to live, Captain John Regent took a deep breath and left the man's body.

T Minus: 052 Days 17 Hours 09 Minutes 24 Seconds

That wasn't how it was supposed to go.

Regent took a gasping breath. He was always groggy after coming back, and he shook his head to clear the fog.

And then he felt it. Like a skin-shriek, an agony-wail from his skull to his shins.

Pain.

Every time he wandered, he could almost forget.

Almost.

He bit down hard. It fucking hurt.

He looked at himself in the mirror of his dark hospital room. Someone must have thought he was asleep and wheeled him back. The shades were drawn. Sunlight peered in from a crack in the curtains and made a long triangle on the floor. Everything else was gray.

John sighed. He was a wreck. He wasn't human. Not anymore. He was the shattered remains of a once-potent man, a soldier. But that man was gone.

The taut-skinned burns that covered a third of his body, including half his head, didn't just give him a slight speech impediment and pull his limbs into odd gestures when he slept. They gnawed. They stabbed. They writhed. They gave him phantom limbs he'd never had. Inhuman limbs. Grasping, angular, insect-like appendages that came and went and were never the same again.

He looked down at his left hand, shriveled from the burns and atrophied from the nerve damage. The skin looked like demon flesh, mottled and stretched, lighter than the rest. It was destroying him.

John reached for the bracing bar that hung from the ceiling and pulled his six-foot-four frame out of his chair with one arm. He crawled into bed with a grunt, dragging lifeless legs.

He was left-handed. Before. Now it was his right or nothing. In fact, his right arm was just about the only thing in his body that worked the way it was supposed to. It fed him. It operated his motorized chair. It dressed him. It flipped the cap to the morphine button up and down. Up and down.

John laid his head back and tried to sleep. Wandering wore him out. Wrangling the heavy bull of the unconscious required a strong grip, an all-consuming concentration.

Regent's doctors urged him to use the medication. He could have as much as he wanted, they said. They always had sad eyes. Except Dr. Zebro. She knew. But the drugs blunted his mind, made it just like the rest of his body. He couldn't focus, couldn't meditate, couldn't wander. He was helpless on the drugs, trapped in a hazy prison where pain poked through the fog like a searchlight and half-forgotten memories of caves and torture bubbled up from the ground.

It was the same place that Mario was hiding. You can't stay there. No one can.

Half an hour later John had done little more than doze. His fingers twitched from the pain. His skin crawled like it was trying to get off him. Noises echoed from down the hall. Doctors and nurses argued about the strange return of a coma patient no one knew was gone. Apparently the man had been shot. Apparently he'd busted a drug house. Saved a baby. Or some made-up shit.

Somebody used the word hero.

Regent snorted. Heroes don't take other people's bodies for a joyride. They don't implicate them in an assault. They don't almost get them killed.

As he laid listening to the increasingly fanciful tales of the afternoon, John's conviction only grew. He couldn't stay, couldn't take the constant temptation of working legs and no pain.

John didn't know what "Jeff's" real name was. He didn't want to. He didn't want to think about how he'd just changed the man's life forever.

He grit his teeth under a tingling wave of needle-jabs that made his arm twitch.

There was no getting around it. He had to leave. But the only place John Regent could go was the last place in the world he wanted to be.

He liked to think he wasn't afraid of anything, but it wasn't always true. He had made the call that morning. It was a condition of the deal he made with himself. He could have one more trip. If he called first.

Happy to have him at the house, his dad said. They'd pick him up tomorrow. Be there around 2:00. After that, whatever freedom John had left would be gone.

There was a soft knock on the door. Nurse Brand poked his head in and saw Regent was awake.

"I hear you were looking for me."

John grabbed the bracing bar and pulled himself up as a ruckus broke out at the end of the hall. "What's going on out there?"

"News crew." Ethan Brand stepped into the room. He was thin with neat blonde hair laced in a barely noticeable gray and a gathering set of crow's feet. His fingernails were manicured. He wore light blue scrubs.

"News?" Regent did his best to pretend he didn't know why.

Ethan walked across the room to check John's morphine drip. Unused. He wasn't surprised. "You didn't hear? There was big a commotion today."

"I made the call." John wanted to change the subject.

Nurse Brand stopped, then turned to open the shades and let in the sun. "Time to take your stats."

"Again?"

Ethan stood by the window as light poured in. "I suppose you want me to put in a discharge request."

John nodded.

Brand stepped to the wall near the bed and removed the blood pressure cuff from its holster. He wrapped it around John's good arm. "I wish you weren't going."

"It's time."

Ethan held Regent's hand as the cuff inflated. It wasn't necessary, but he held it firm.

John nodded. He was going to miss his friend. He thought he better say that. Out loud. He liked to think he wasn't afraid of anything, but it wasn't always true.

"I'll miss you guys."

"We'll miss you, too."

The pair had met John's first day at the hospital. That was three months ago. John was mean back then, but Brand met the anger with compassion. Everyone always wanted to rush in and help. They were just trying to be nice, helpful, but it pissed Regent off.

Ethan was different. Ethan always let John try it himself first. After his shifts were over, Nurse Brand would often sit and listen with the other patients as John told stories from his time in Special Forces. Only a lot of the soldiers were dealing with serious trauma, so all the tales were politely devoid of any conflict. They were stories about Army mix-ups and raucous post-mission shenanigans.

John realized he might not see his friend again. He didn't know Ethan's work schedule. If he was off tomorrow, that meant it was now or never. "Can I ask you something?"

"You can ask me anything." Ethan ripped the Velcro and replaced the cuff on the wall.

"Why here?"

"What do you mean?" Nurse Brand reached down to check John's colostomy bag. It was a testament to the men's trust that he didn't need to ask.

"Why soldiers? You're good. You could work lots of places. Why here?"

It was a special hospital, a joint program between the Veteran's Administration and the U.S. Department of Health, a halfway house for returning soldiers with major psychological trauma or anyone having real difficulty adjusting to civilian life. Attendance was voluntary, but for some strongly encouraged.

"Ohhh . . ." Brand nodded.

John shrugged with his good arm as Ethan checked his pulse. "I don't want to pry."

"So now it's finally my turn to tell a story."

"Hey, you don't hav--"

"No, it's okay." Ethan walked around the bed to the wall-mounted computer near the door. "When I was a kid--twelve I think--I got beat up by some neighbor boys for carrying dolls."

"Carrying?"

"Yeah. I was bringing them to my sisters. From a family friend's house. I think I was looking at them or whatever, probably imagining too. I suppose that was playing, but I didn't think of it that way. I didn't like dolls any more than any other boy my age. I played video games. Soccer. I just didn't think dolls had cooties. Little tween me didn't think there was anything wrong with them." He entered John's stats into the machine.

John understood. They'd never spoken about it, but he understood. "Were you hurt bad?"

Ethan shook his head. "It was the shock and embarrassment more than anything."

"I'm guessing that wasn't the last time something like that happened."

"Oh sure. But I know people who had it way worse than me. In nursing school I dated a boy who hadn't come out yet. He got beat up pretty bad one night. He wouldn't tell me why. He was always so angry." He sighed. "Anyway, I'm rambling."

"It's alright." Talking took John's mind off the pain. A little. That's why he told stories.

"It wasn't like it was my life's goal to work with soldiers or anything, but I did jump at the chance. And I've stuck with it for . . . Oh wow, fourteen years. I guess--and this might sound crazy--but I guess I felt bad for those boys."

"The ones who hit you?"

"Yeah. And the ones in high school. And the ones who say things now. They're all so worried. All the time. Worried about looks. Worried about what people will think."

John knew the type. "They wouldn't call it that."

"Oh, of course not." Ethan snorted. "They think they're standing up for . . . whatever." Brand waved his hand.

"But?"

Ethan stopped. He leaned against the wall. "You'll think it's corny."

"No, I won't."

"Yes. You will. But that's okay. That's kinda the point."

"What is?"

"Well, I asked myself, if I was serious about helping people, if that's really why I'm doing this, then why not go straight to the top?"

Regent nodded.

"Gay people can be patriots, too."

It was the first time Ethan used the word. With John, anyway. Regent thought he should have asked sooner, should have had the courage. "Well, on behalf of all the fucked up soldiers who come through here . . . Thanks."

Ethan snorted and rolled his eyes in jest.

"I'm serious." John thought about all the times Nurse Brand had helped him bathe. He suspected. Everyone did. John realized that knowing bothered him a little. Not that it was a problem for Ethan. Ethan was a professional. It was John's problem, he knew, and so he kept it to himself. "You take good care of us."

"Your turn." Ethan looked at his watch and then sat down in the chair under the TV. "One more story. For old time's sake."

"Alright." John nodded. He thought for a moment. He wanted it to be a good one, something special for his friend. "Did I ever tell you about the time I went to see my granddad in Atlanta?"

"I don't think so."

"My dad was born down there. He moved up here to Philly after mom graduated. She was going to school down at Spelman when they met. After she died, dad remarried, and we didn't get to see granddad much, but when I was a kid, I got to stay with him in Atlanta for a few days. He was real excited about it. He never liked that dad left. He took me to this packing house one day, all brick and everything. It had been remodeled. It's an office building now. Urban gentrification and everything, right?"

"Right."

"Before we went, he talked about it for days. Not all the time, but enough that I could tell it was important to him. He said it was an important part of my past. Couldn't miss it. Had to see. I thought he was gonna show me where he met grandma or something like that.

"But when we got there, the nice folks let us in and he took me to this brick wall in a hallway that ran between the old loading dock--which is walled off now and full of conference rooms--and the old offices. He pointed to the wall next to a drinking fountain and said, 'look there.' I looked. I didn't see nothing.

"But he urged me. 'Go on.' I didn't want to disappoint him, so I stepped up and looked real hard. But it was just a bunch of old brick. Some of it looked like it had been patched up a long time ago.

"'I worked here for twenty years,' he said. 'I'd haul in produce or paper or all kinds of stuff and here they would pack it up and ship it all over the state. We carried a lot of heavy boxes, loading and unloading. We didn't have those big lifting machines, and no workplace safety either. So we'd get tired. I'd come up here to get a drink. And right there, that's where the Colored fountain was, all dirty and cracked, next to the one for the white folks.'"

Regent looked at his bed covers and smiled.

"How old were you?"

"Maybe eight or nine. I had no idea what the old man was talking about. I mean, I knew the history. We learned about that stuff in school. But it didn't really mean anything to me, just stuff in books. Still, I could tell it was real important to him that I see it. So I nodded and all.

"It wasn't until I got older that I understood what he was trying to show me. He was a good man, my granddad."

"I don't suppose he's still with us."

"Oh, naw. He died a long time ago. Heart attack, I think. I wanted to go to his funeral down in Atlanta. I could tell my dad did, too."

"Why didn't you?"

Regent thought about his stepmother. He would be living with her again. Tomorrow. For the first time in nearly a quarter century. He could already see the rage behind her eyes. He'd be stuck in his chair, dependent on her and his aging father for help bathing and with his colostomy and all the rest. He shut his eyes and then opened them. "Just didn't work out, I guess."

"Well, I'm going to miss your stories, Captain. Especially the one about the cat."

"Oh, you liked that one?" They both smiled. It was a dirty story. "Truth is, I'll miss you all, too. Talking really helps."

"With the pain?"

John nodded.

"Will you have anyone there, where you're going? To talk to?" Ethan had a hunch.

Regent turned the corners of his mouth down. His burnt half barely moved. "Naw. Not really."

Brand didn't say anything for a moment. "You could stay."

John just shook his head. No. He couldn't. There was a man in another room with a bullet in his leg that proved it.

Ethan stood. "I'll put in the discharge request. BUT . . . I won't like it." He walked to the door.

John smirked.

"Try to get some rest."

Regent nodded in agreement. But he knew he wouldn't. Tomorrow, he was no longer free.

T Minus: 051 Days 19 Hours 03 Minutes 25 Seconds

That was odd.

The door was already open.

Dr. Amṛta Zebro removed the key to her office and pushed the door with her knee. It was heavy, designed to keep the voices inside from being heard in the hallway, and she lost her balance for a moment. It didn't help that she had a purse hanging from one arm and a stack of files in the other.

A woman was sitting behind the desk, her desk, reading her computer screen. Amṛta stood in the door, shocked. The woman was African-American, 30-ish, with short, straightened hair pinned to her scalp and a simple striped jacket and slacks. She didn't even look up.

"Excuse me." Dr. Zebro objected. Her hair wasn't nearly as well-kept as the intruder's. "Who the hell are you?"

"Relax, Doctor." The woman clicked the mouse. She didn't turn. "I'm one of the good guys."

"What's that supposed to mean?" Amṛta dropped her purse and files on the floor of her office and stepped forward. Everything scattered. "You're not supposed to be in here." She looked at the half-turned screen. "Those files are confidential!"

"Calm down, Doctor. Please. Have a seat."

Amṛta crossed her arms. It bunched her white coat. She stared. She was a head shorter than the interloper, with a round face and hips and the dark complexion of her ancestors. She kept staring. She couldn't sit. Her seat was taken.

The intruder smiled and stood. "My name is Ayn." She extended a hand across the pristine desk.

Dr. Zebro kept her arms crossed. She was angry, livid, but not so much as to miss her guest's most distinguishing feature: that she didn't have any. Ayn was dressed like your average professional. She was moderately attractive but wouldn't turn any heads, and she seemed to keep it that way. Her make-up was plain. Her clothes were off the rack. There was nothing notable about her appearance. At all. Amṛta was a psychiatrist. She was trained to diagnose people. Most wear a wedding ring, or they have a cowlick or shoes scuffed from a slight pigeon toe. Or maybe their necklace dangles a cross or locket or grandma's old pearls. Something.

But not Ayn. She wore a simple gold chain. Her earrings were simple dots. Her shoes were clean, round, simple. She was a mean, a calculated average. Everywoman.

Ayn pulled a tri-fold from her jacket. "This is an order from the Judge Advocate General's office giving me access to all notes and files on one of your patients."

Amṛta didn't take it. She walked around the desk and waited for Ayn to move. Apparently they were having a battle of wills. It was too early for this, she thought. On a Sunday.

Ayn smiled again set the order down. She walked past the doctor slowly and settled into one of the two chairs in front of the desk, near the window.

Amṛta dropped into her high-backed and well-used office chair and sighed. It was still warm. She glanced at the screen and then picked up the tri-fold. "What's this about?" She opened the packet of papers.

Ayn waited for her to finish reading.

Amṛta flipped from one page to the next, then tossed the packet across the desk.

Ayn folded it and put it back in her jacket. "What do you know about Captain John Regent?"

"Not much. His service record has been heavily redacted." She said it like an accusation.

"Did he ever discuss the circumstances of his capture with you?"

Dr. Zebro shook her head. "John has been reluctant to talk about anything but his family."

"Is that unusual for these military types?"

Military types. Amṛta repeated it in her head. "Ayn" wasn't a soldier. And she hadn't dropped any credentials, which meant she probably wasn't a lawyer either. They're always quick to share. And if she wasn't a soldier and she wasn't a JAG prosecutor, that left only one thing.

Dr. Zebro sighed. "What's that supposed to mean?"

"Oh come on, Doctor. You know how it is. All these big, tough boys keeping their feelings buried under a mountain of rage."

Ayn was baiting her. "Captain Regent isn't like that."

"No? That seems unlikely."

"He's a very genial man. Intelligent. Respectful. He's very well-liked by the staff."

"But?"

"What do you want, Ayn?"

"How long have you been here, Doctor? At this hospital?"

"Something tells me you already know the answer to that question."

"You've been a contractor with the DoD for fifteen years. Where were you stationed before?"

"I didn't see anything in your court order about me."

Ayn smiled again and sat back. "Doctor Zebro, can I call you Amṛta?

"Sure."

"Amṛta, let's be open with each other."

"That would be nice."

"You and I are never going to be friends. We're never going to exchange bundt cake recipes or share wedding pictures. I don't care if you like me or not. But I have a job to do, and it requires your assistance."

She stopped short of a threat.

Ayn went on. "You were stationed in San Diego before this, correct?"

Amṛta knew exactly where she was going.

"That's a long move, coming all the way here to Philly, especially with your whole family still in Southern California."

"Ayn? Can I call you Ayn? I assume so since you haven't bothered to give me your real name." Dr. Zebro sat forward and rested her hands on her desk. "I'm a board-certified psychiatrist specializing in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. I also have a master's degree in cognitive psychology and nearly two decades' experience playing mind games, like this, with some of the smartest and most heavily damaged psyches in the world."

Ayn waited.

"Let's pretend that you artfully steered the conversation to Sergeant Wilkins and the shooting and I'll stipulate that he's the reason I was moved here and that it was a tragedy and that that whole episode continues to cast a shadow over everything I do. Yes, I think about him every day. Yes, I wonder if there was something I missed. No, I am not suffering a crisis of confidence because of it."

"Is that what you think I was going for?"

"Do you really want to know what I think?"

Ayn motioned for Amṛta to continue.

"I think it's very easy to manipulate people when you genuinely don't care about them. At all."

"Are you saying I'm a sociopath, Doctor?"

"Isn't that what the NSA looks for?"

Ayn crossed her arms.

Dr. Zebro continued. "You're not a soldier. You're not with JAG. The CIA doesn't work domestically. Shall I keep going?"

"Your intelligence was never in question, Doctor."

"Just my competence."

"It's a fair question given what happened." Ayn was serious.

Amṛta took a deep breath and looked out the window. It never ended. It would never end.

"Sergeant Wilkins killed three people. And himself."

Dr. Zebro looked back from the window. "Get to the point, please."

"Doctor, do you know what Captain Regent is?"

"Yes. He's a man in pain."

"No. He's a weapon. And it's my job to determine whether or not he poses a threat."

"That's funny." Dr. Zebro glowered. "I thought that was my job."

"See?" Ayn opened both her hands. "We're on the same side after all."

"Let me ask a different way. Why are you here?"

"We need time to complete our investigation."

"Yesterday he asked to be discharged."

Ayn nodded.

Amṛta wondered how long they'd been investigating him, reading her reports without her knowledge. Sometimes she really hated working for the military. Sometimes it was the most rewarding job in the world. "He has family coming to pick him up this afternoon."

"That's wonderful to hear. Family is important."

"He's not a prisoner."

"And we're not asking you to treat him like one. According to the United States Army, Captain Regent is a hero."

"The most I can do is hold him for 72 hours. IF I felt he was a threat to himself. Or others."

"We're not asking you to do anything you're not comfortable with."

Yes, you are, Amṛta thought.

Ayn sensed the hesitation. "I can't give you details, of course. But I can say this. After walking out of a very, very secret location, Captain Regent was captured by forces unknown and held for not less than six months and not more than eighteen. In that time, he was tortured and beaten and made to endure--"

Dr. Zebro interrupted. "The fracture patterns on his femur, tibia, and fibula indicate his legs were broken, repeatedly, with some kind of precision tool and then allowed to heal. The contact marks and burn pattern on his skin suggests he was hooked up to a generator or battery while being drenched in gasoline. His face was burned with acid--"

"We've read the same reports, Doctor."

"Really? How wonderful. Then you know he's suffered enough. He's in constant pain."

"And yet he refuses his medication."

Amṛta rubbed her cheeks in frustration. Give her a suicidal patient any day. Anything other than a spy.

Ayn didn't stop. "I'm not board-certified in anything. I didn't go to Berkeley. I just went to some plain ol' state college down south. But I read something recently. Maybe you can tell me if it's true."

Dr. Zebro waited.

"Patients engaging in masochistic behavior are often punishing themselves for something. Is that right?"

"It's not that straightforward."

"But it is a possibility."

Amṛta didn't answer.

"Doctor, whether you are or not, a lot of very smart people are bothered that Captain Regent refuses to state why he went AWOL or who his captors were."

Dr. Zebro looked down at her desk and waited for Ayn to finish her sales pitch.

"You probably don't know this but he was found dragging himself, one-armed, through a desert two hundred miles from his last known location. Barely alive."

Amṛta looked up. "I'm guessing that was in a part of the world we're not supposed to be in."

Ayn ignored the quip. "And no one has any idea why a highly decorated soldier with an impeccable service record suddenly walked off the reservation. We don't know where he was or who took him or why they let him go."

Amṛta snorted. "Or what he told them while he was gone."

Ayn paused. "That, too."

Dr. Zebro took a deep breath and exhaled. John's service record had more black line than text. It was obvious he had seen things, secret things, embarrassing things. The cynic in Amṛta wondered if that's why they let him come home. They needed him to relax, get comfortable, so they could uncover what he revealed. And to whom.

Otherwise they would have just eliminated him in-country.

And now the powers-that-be wanted Amṛta to declare him a risk to himself and hold him against his will. They would need a judge's ruling to keep him more than 72 hours, but she guessed that would be plenty of time for a well-connected agency to find one.

They didn't care about John, she knew, and they were holding Derek Wilkins over her head, giving her an "excuse." Better to be safe, right? Better not to risk another soldier with PTSD snapping and taking a service sidearm to his family. And then himself.

Ayn could see the conflict on Dr. Zebro's face. She stood. "I'm going to interview the staff. But I'll be around. Do let me know what you decide."

Dr. Zebro looked up at the dark woman. Ayn wasn't going to leave until Amṛta did what they wanted. For whatever reason, the NSA just declared war on John Regent.

Amṛta watched the spy step over the pile of spilled files and walk out the door. She took another deep breath and sighed. Poor John. After everything he'd been through, everything he did to survive, to escape, to get home, it still wasn't over.

Now his own country was after him.

May 8, 2014

Meet John Regent, Former Professional Badass

This is the VERY rough cut of chapter one of Nomad, the first installment of The Minus Faction. It needs a lot of work yet, but for those who are interested in John and what he can do, you get the idea.

The trick to borrowing someone else’s body is to not get caught.

But then getting caught is not the same as being seen. You can be seen all day. All you have to do is give people a single, plausible reason why the man in the hat and sunglasses is not their old friend Jeff who’s been in a coma for six months—Jeff had dark hair and no mustache and that guy’s mustache is blond—and people will assume it’s just someone who looks like Jeff and go right on texting. Or whatever.

The trick to busting a drug deal on the other hand is to not get shot.

On a warm Saturday in April, John Regent failed at both.

According to the Army, the trick to surviving a gunshot wound is to stop the bleeding and get immediate medical attention. This means keeping still and putting pressure on the wound. That’s what they teach in Basic training, and it’s true.

But then, people who are scared and angry enough to shoot at other people tend to keep shooting as long as those others are around, so the trick to surviving a gunshot wound while still being shot at by scared, angry people is to not go into shock. And the best way to avoid shock is prior inoculation: being shot before, preferably multiple times. Like homeopathy for soldiers.

Of course, any nice, normal person would have listened to the armed and screaming drug dealers and simply left. But Regent had a job to do, and he had been trained exactly for this kind of thing. In fact, it was in training that Regent had been shot the first time. Not Basic training. Not Ranger training. Not even Special Forces training, although they feigned it.

It was after that, at the training that had no name for a unit that had no insignia, the same training that had no manual and that never, ever took place. Officially. It was the training where John had been drugged, blindfolded, shot in the arm, and dumped out of a helicopter into a swamp by his own instructors and told to find his way back without a map or compass or anything. Oh, and there are guys on the ground hunting you. With dogs. It wasn’t until the clouds parted a few hours after the drop that John could see the stars and figured he wasn’t even on the same hemisphere anymore, let alone the same continent.

That was Day One of the training that didn’t exist. Things got progressively harder from there.

The trick to hostage rescue is getting inside without the hostage-takers killing anyone. Standing there, bleeding against the door of some asshole’s second floor apartment, John was already inside.

See? He told himself. Stop complaining. Hard part is already over.

Of course, it helped that when he wandered, when he was in someone else’s body, Regent could control the pain. And the fear. And all the responses—all the shit—your genes saddle you with in their vain effort to keep themselves alive. Riding someone else’s bones, John was in total control like he never was, like no one ever was, in their own skin. Even with a gunshot wound, he had total clarity.

The trick to disarming someone is getting them to want to drop the weapon, even if they really don’t want to. There are a variety of ways to do this, but if you’re reasonably sure your target hasn’t seen combat—this kid looks like a tool, John thought—then a firm strike to the top of the forearm usually does the trick, preferably with something hard. You know the place: where the skin runs thin over the bone and good whack sends a shock of pain to the hand.

The thing about combat is that you do and see shit normal people just don’t ever experience in life: get hit, stab someone, see your buddy’s head explode in a burst of red smoke. That kind of thing. It’s a shock some people never shake, people like John’s friend Mario. Mario had just finished a tour. Mario was in bad.

The drug dealers in the room hadn’t seen combat. They were barely literate punks. Mean, but undisciplined. They all stood there for a moment as the handgun bounced on the floor with a thud. No one expected “Jeff” to fight back, not after being shot, not without a pause for breath.

To Regent’s right, asshole number two stood at the end of a couch where a young mother sat clutching her baby. Fuck. No shooting to that side. To Regent’s left, asshole number three already had a hand on his gun. He was twitchy, not afraid to shoot, but he had his pants around his knees, which meant he wasn’t mobile.

Three seconds. Tops.

In a single fluid movement from the one that had disarmed his first opponent, Regent popped the kid in the throat. That disorients. People who aren’t used to getting hurt, people who aren’t trained to stay focused, think about the pain and—for a second at least—worry about whether or not they’re able to breathe. That distracts, makes their limbs pliable.

Regent clutched the man close, using him as a shield as he walked forward along the couch, pushing asshole number one toward number two while number three raised his weapon.

Two seconds.

John was an athlete, or he had been once, and he stared ahead like he was getting ready for a juke. His didn’t take his eyes off his target. Then he pushed asshole number one to the left without turning. The man, still clutching his throat, stumbled in front of the twitchy gunman.

One second.