Rick Wayne's Blog, page 103

November 4, 2014

John's Theme

Composer Steven price, who won an Oscar for his score to the film Gravity, has an album of original music called Acoustic Reflections.

I looped this track near-continuously, sometimes for hours on end, when writing some the key sequences of The Minus Faction, Episode One.

So with all due respect to Mr. Price, here is John's Theme.

November 1, 2014

My Top Five Heroes

A few weeks ago someone I know asked everyone to name their heroes. It really got me thinking. What is a hero? Who qualifies? Why?

Picking a fictional character seemed like cheating, or at least a cop out. Fictional characters don't have to engage with a complex world like we do. Plus, what then is the difference between a list of heroes -- real heroes, which is what I took her to be asking -- and just a list of your favorite characters?

It also seemed like cheating to include fictionalized versions of (probably) real people, and for the same reason -- so no Robin Hood or Gilgamesh or Jesus. We no longer experience those people aspeople. They are living parables and what facts of their lives don't fit the story are discarded (such as almost everything Jesus did for the vast majority of his life from birth until he started his ministry).

This is important because of what a hero is, or should be. It seems to me they should be someone you could reasonably imitate. (Other people will give a different definition and would have you striving for an ideal you can never reach.) But try as I might, I will never be able to heal by touch or shoot lasers out of my eyes.

That's not to say fictional characters can't inspire. Obviously they can, and do. But picking fictional or fictionalized people for this list seems like stitching a quilt of platitudes and calling it a philosophy.

"My philosophy is that we should love each other and be fair and kind and always do the right thing. My heroes are Superman and Captain America because that's what they do."

Great. Except what's the right thing? Not in general. Right here. In this particular instance.

Everybody does what they think is the right thing. Even Hitler. Batman makes a choice Superman never would, the same choice that Lincoln made: in certain circumstances the right thing is to suspend the rule of law in order to save it.

People who disagree with you -- your enemies, the political opposition, whatever -- don't believe what they believe because they think it's wrong. They think it is just obviously the right thing, and that you are deluded and destined for harm. But the both of you will always say, "we should always do the right thing."

So this was actually a very useful exercise for me. It helped to clarify my ideals and some gaps I'm currently living in. And I think that's what heroes should do: live the ideal but stretch their hand to you across the gap. Here are my five:

1) The paragons of nonviolent resistance, those who appreciate that you do not make the world a better place by answering hate with hate or violence with violence, that there is a difference between outrage at a vile belief and outrage at the belief-holder, and that basic human respect must always be given even when it is not returned. For this I would pick Nelson Mandela, not because Gandhi or Dr. King (or anyone else) aren't heroes, but because I'm naming only five, and because out of the lot, Mandela suffered so greatly and for so long.

2) Those who exemplify that character is an emergent property and more than a collection of virtues. Again, there are many people one could pick, but I will go with Abraham Lincoln. You can buy a book of his complete writings, including telegrams and military orders and short letters. Inside is no great and original philosophy, no breakthrough in maths or science, no work of art. Yet, even just perusing his polite correspondence, flipping the pages at random, one comes to understand character.

3) Those who don't just create but revolutionize art -- which includes music, film, poetry, fiction, and humor -- and who do so spontaneously and authentically rather than as a concerted (and conceited) act of rebellion, like Joyce's or Picasso's. Here, if only because of my chosen profession, I would have to go with Lady Murasaki Shikibu for inventing the novel, and for doing so without being conscious of it. That is the essence of creativity.

4) Pioneers of thought rather than the noble accountants, like Maxwell or Newton (who often get the acclaim); those who stand on the threshold of the world and imagine non-fictional alternative realities. If I could pick only one -- and there are many who qualify, both male and female -- it would have to be Charles Darwin for exemplifying the inductive leap that distinguishes men from machines and science from math. Quite simply no act in the history science equals Darwin's. Other discoveries have been (and will be) more important -- in the long run, I expect Watson/Crick/Franklin's discovery of the structure of DNA will lead to a complete re-architecting of what it means to be human, or meta-human. But nothing equals Darwin's mix of unbounded imagination, elegance, and courage, and all without the use of math or complex machinery.

5) Those who demonstrate that, in any worthwhile relationship, you shouldn't be afraid to be the one who loves more, and if you are, either the relationship isn't worth it (and should be let go) or you aren't, and that you should make sure you know which is which. Someone like my ex-great-grandmother-in-law, who never had any children of her own but who raised many others well, who was 17 and already married four years when the British left India.

Some runner ups: Zheng He, Bernard Williams, Rosalind Franklin, Joseph Campbell, whoever carved the Thinker of Cernavoda, Aphra Behn, Michael Faraday, CS Lewis.

So there you go. Name your five!

art by rafael silveira

null

October 28, 2014

What We Talk About When We Talk About What We Talk About

Since I'm apparently not writing any fiction for awhile, I've been thinking about a blog post called:

What We Talk About When We Talk About What We Talk About

which would itself be about the popularity of providing the world with meta-level commentary on your own utterances, worthy as they are of such analysis -- and hey, if other people won't do it, then roll up your sleeves and do it yourself, I say -- but I just don't care enough about people's self-referential points of view to deal with the ire it would surely generate.

I am not ironic enough for the internet.

October 16, 2014

A Carnival of Loss

in my writing i often tackle the carnival-esque-ness of contemporary culture, but i do so ironically. much of the media we consume is self-consciously mythic, which doesn't necessarily mean it has swords and wizards and shit, although obviously some of it does. it means it fills the role of myth.

back before culture was lifted out of space-time, before wrist watches and a money economy, myth-making was integral to the social order and so was restricted to a few, and the myths themselves were highly conserved. new stories about the buddha or king arthur would appear, but there were always strong pressures toward conservation.

once myth-making became a commodity, something distanciated (but not wholly removed) from the cultural power-narrative, it is appreciated as something superficial. we think we think game of thrones is just a tv series.

but the cognitive necessity of myth-making means we still appropriate it deeply, even if we don't think we do. it just doesn't have a very long half-life. the new myths aren't so much abandoned as they simply fade away like a decaying atom: brilliant in their time but unnoticed in death.

this is why we experience that flash, that epiphany, whenever someone mentions something we haven't heard in a long time. "ah! i remember that! man, i haven't heard that in forever."

some myths well and truly die. others seem to be immortal. but most simply stop bobbing above the surface and slip unnoticed into the depths of the collective unconscious where they wait to be stirred.

this is what makes contemporary culture a carnival. every tent is the most exciting for five minutes, but when it's all over, little of any persists.

what's fascinating, then, is how the cohesive function of myth seems to have escaped to the meta level. it is no longer our collective experience of the same carnival, over and over, that binds us together, as it did in pre-modern societies. rather, it is our shared experience of the experience of many carnivals, the "what-it's-like-ness" of being a carnival-goer, that anchors us. whatever myths we experience, we share the experience of experiencing myths.

i don't wonder if that's why so many people these days are writers and filmmakers. yes, i'm sure it helps that the costs of production are so low, but i can't help but wonder if people are attempting to fill a lost connection -- something they would have gotten through shared experience of the bible, or the antics of krishna -- by fleeing to that meta-level where our last human connections remain.

if so, that suggests a sort of feed-forward mechanism where, as more and more myths are made, our experience of them is shared by fewer and fewer people, and we retreat further into the aether.

that would explain why so many people are compulsively self-expressive and yet what they express is loneliness and despair. we sit alone outside our own carnival, waiting for passers-by.

October 13, 2014

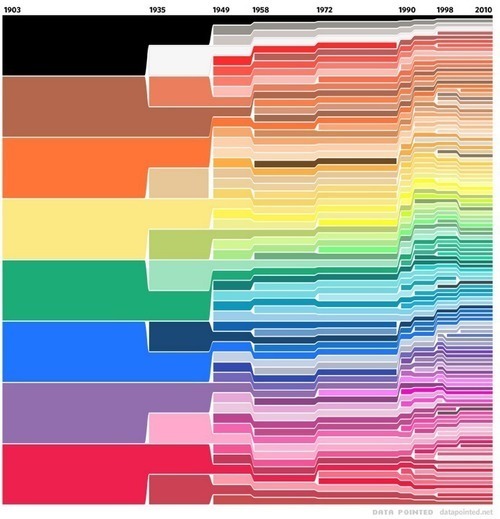

Holy Crayola!

Historians divide the last 250 years into the "long Nineteenth Century" (stretching from the French Revolution to the First World War/Russian Revolution) and the "short Twentieth Century" (running from the inter-war period to the fall of the Berlin Wall).

Obviously this is a sociopolitical rather than chronological division -- minutes and seconds don't care what happens in them -- and I think there's something to it. The long Nineteenth Century was about industrialization and the birth of ideology and the consequent destruction of pre-modern ways of life. British historian J.M. Roberts called western culture of the high modern period "corrosive," and it was. It dissolved traditional modes of life wherever it appeared.

The short Twentieth Century was about post-industrialization and the extremes of ideology leading to dissolution and Durkheim's social anomie. Everything that has happened since the end of the Cold War -- including the birth of the internet, the wars in the Middle East, and the succession of bursting economic bubbles -- is sociopolitically part of the Twenty-First Century.

What's always fascinated me is how, unlike earlier eras -- which were very aware of the changes creeping over them -- people today are largely ignorant of the "social structure," that there even is such a thing, that they exist in one, of what their relation to it is, of the current structure's relation to the past, of what the alternatives are, and of how we might go about realizing them.

People of earlier eras were born with landmarks and watched them fade beyond the horizon of history. But if you were born on a hazy sea and have never seen a mooring or landmark, then you never know you're adrift. The very idea of being adrift will seem alien, as if a lie imposed on you by some meddling Other. "Adrift? Adrift relative to what?"

I would like to give you a landmark. This is every color of crayon offered by Crayola over time.

Note first the historical divisions mentioned above. The end of the Nineteenth Century and span of the Twentieth jump right out, as does the birth of the Twenty-first.

This is a map of history colored in crayon, and it can be replicated across almost any aspect of your life: where to live, what kind of job to get, what breakfast cereal to buy, the number and kind of potential mates on offer, the quantity of diversions at your fingertips, and so on.

If you're not happy with any of these, when would you ever be?

September 30, 2014

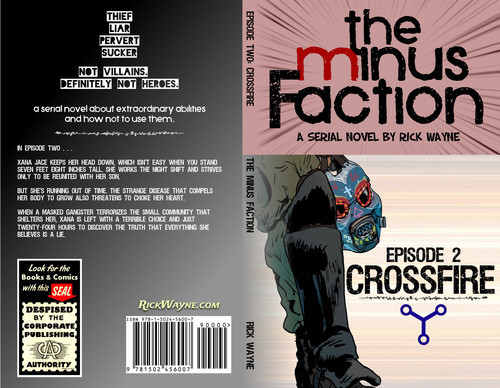

THE MINUS FACTION Episode Two Print Cover!

Notice the blended art at the spine! I am the master of the layer mask. No, I'm not. In fact, before yesterday, I didn't even know what a layer mask was. BUT this should hopefully solve the pesky variable-spine-fold problem from before.

September 26, 2014

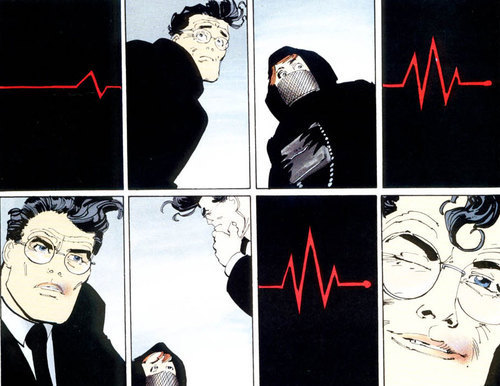

The Myth of the Batman, or Why I Love Reboots

Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns casts a long shadow over the Batman mythos. Not only is it considered paradigmatic for the character, it's also considered part of the larger comic book canon. I very much doubt DC is interested in challenging that status with a reboot of the premise.

But they should.

Batman isn't just a comic book character. Not anymore. He is, like Hercules or Robin Hood, a legend. He has entered our cultural mythology, and as such, our enjoyment comes -- as with any myth -- from the telling and re-telling and re-re-telling, just as Jesus's story has been told and retold in different media for centuries: painting, stained glass, books -- each the same, but each also subtly different.

I love reboots. I love seeing the familiar played out in new ways. I like original stories, too. Saying you like something isn't the same as saying you only like it. But reboots are fun. While everyone else seems to groan and roll their eyes when someone announces a reboot, I squee and clap like a little girl.

That being said, some are definitely better than others. With Batman, you have to respect the myth. I enjoyed The Dark Knight Rises when it came out, but I haven't returned to it like I have The Dark Knight Returns (and the other two films in the cinematic trilogy) because, for me, it broke the myth.

"Breaking the myth" is not changing continuity or putting a character in a new role (or new gender). Those things are part of the fun! I love seeing familiar characters shuffled into a new "slot" and suffering new setbacks. Rather, breaking the myth is breaking the structure of the story, which at its heart is a cycle: The Eternal Return.

The Eternal Return is the only story. It's is the story of life, the story of the universe, the annual cycle of the seasons. For mere mortals -- who are praised in "serious" literature rather than myths and comics -- there is birth, marriage, and death and that's the end. For us, everything is comedy (you find a mate) or tragedy (you die).

But for gods, there is one more step after birth, marriage, death: return. Osiris dies and is brought back by his wife. Jesus dies and returns to redeem mankind. Odysseus is lost coming home from war and returns to save his wife. The story of Gilgamesh was read aloud at the Babylonian new year to ensure the repetition of the annual cycle -- the return of spring, which is life conquering death. Even though we know in time it will succumb again to winter, there is always hope, always the eternal return.

Batman isn't a mere mortal. Batman is a god, and gods don't quit. They don't get laid and ride off into the sunset like some petty outlaw. They return. They must return, for the story must be retold, over and over, so that the world -- and our soul -- is renewed.

The cycle of the Batman is simple: He beats back evil (usually at the last second) through his intellect, his will, his sheer human potency. (I always loved that the Batman had no super powers.) In so doing, he experiences acts so depraved they would haunt a mere mortal like you and me for the rest of our lives. He returns home bruised. He gets a little rest. And the next night he's back on the rooftops solving new crimes, facing new horrors. A silent guardian. The Dark Knight.

Incidentally, his mythical, god-like nature is the reason why Bruce Wayne himself is not all that interesting. He doesn't change. We don't want him to. A big part of what makes the Batman mythos so enduring is his gallery of rogues. The Joker, for example -- a man who faces a psychological shock like young Bruce, but who, in not being a god, cracks under the strain and goes mad -- has always been more human (although certainly not humane) than his counterpart, the silent, stoic, unchanging hero.

Batman returns, just like Jesus, Odysseus, Osiris, and every other god-like hero in the great stories of mankind. Batman always returns. That's the myth. Miller understood that where Nolan (apparently) did not. MIller ends The Dark Knight Returns with Clark hearing that wonderful, wonderful heartbeat.

Art by you-know-who

He's not dead. It was all a ruse, all part of a plan to carry out his work unhindered by politicians and the press. You thought the return mentioned in the title was Old Man Bruce coming out of retirement at the beginning of the story. But it wasn't. The return was at the end.

I still get goosebumps!

The Dark Knight Returns came out in 1986. I think it's time for a reboot, a re-re-telling. Let me give you my version of the return of the Batman. Call it Eternal Knight.

The year is 1995. After a long career fighting crime, Batman looks out on a city reborn. Saved. Bad things happen, of course. We're still human. But it's not like before. Organized crime has fled to other shores. The major maniacs are all dead, missing, or locked away. No one's heard from The Joker in years. And under Commissioner Gordon's patient reforms, the police force is competent again.

Who needs the Batman?

Jim is the first to go, and although Bruce mourns his friend and lifelong partner in the war to save the city, he also knows that Gordon made a difference. His life mattered. He leaves behind a family. His legacy continues.

Bruce has no family. And he's getting older.

After returning home from another quiet night where there was little for him to do, Bruce finds Alfred dead in a chair, a feather duster in his hands. He had stopped to take a rest from cleaning the house he'd tended his entire life and passed away peacefully.

The house is empty. It's quiet. Bruce is alone. He won't take another Robin. Not after what The Joker did.

So he comes up with a plan. (Bruce always has a plan.) He puts his public persona's affairs in order. He seals himself inside the Batcave. He sends a note to his best and only friend. I need a favor, he says. When its time, he says.

Then he climbs into Mr. Freeze's box, the original cryogenic chamber where the villain held his wife frozen for decades and which Bruce kept -- after freeing her years ago -- with his other trophies: the T. Rex skeleton, the giant penny, his collection of old batsuits.

Bruce closes the chamber, the only one of its kind, and it clicks on.

...

The year is 2086. A heavy seal is broken, but it's moved like a pebble in the ocean. There are footsteps in the Batcave. The cryogenic chamber is opened. Bruce wakes up and looks into the face of his friend.

It's time, Clark says. Two alien empires are clashing, and their war threatens to consume the earth. Bruce asks what Clark needs.

Nothing, Clark says. The war just means he doesn't get to come around much anymore. Not like he used to. Bruce -- ever the detective -- notices the heavy dust in the cave has been disturbed in places and then covered again by time. This isn't Clark's first visit. Or his second. Bruce wonders how many times his friend has come to check on him.

I can handle everything up there, Clark says. There's a new Lantern. She's helping. That's not why I woke you. It's your city. Gotham needs you. Cyborg street gangs terrorize the people. Protection rackets have sprung up in place of the ineffectual police force. The city has swollen to 50 million inhabitants and grown on top of the ruins of the past. A vast underground network exists, lorded over by a messianic cult ruler: the reptilian (and therefore unnaturally long-lived) Killer Croc, who has found new purpose as a spiritual leader of a race of genetic mutants, cast-offs from a failed society.

They need a beacon, Clark says. They need hope.

But why now, Bruce asks.

Clark says he suspects Brainiac had something to do with it. With him.

Clark explains that people wear computers now: screens on contact lenses in their eyes, or implanted inside their retinas; processors under their skin running on bioelectric power. Everything's wired. Someone -- something -- has been whispering to the people through those devices, driving them mad, making them do horrible, awful, unspeakable things... A cyberintelligence that calls itself The Joker.

Clark stops. He listens to the air. Lois is in trouble, he says. My great-granddaughter. I have to go. Bruce doesn't say thank you. Clark doesn't say you're welcome. They don't have to.

Bruce is a stranger in the city. He doesn't know it's pulse like he used to. It's a different beat. He gets into trouble quick and barely gets away. The cyborgs are strong, fast. And he's not as young as he used to be. His old suit won't cut it. He needs something new.

He has to get inside Wayne Enterprises, now a tech giant, but he's not ready for the world to know about him. He hears about a sharp but struggling network security consultant, Evelyn Nygma, a young woman desperate to grow out of the shadow of her notorious (now deceased) grandfather, Edward -- The Riddler.

Evelyn has been working in her spare time to track down "the twins," the anarchist hacker duo known as White Hat/Black Hat. She doesn't believe the man before her really is Bruce Wayne, but he's obviously handy in a scrape, so she agrees to an exchange: they'll help each other.

Evie reminds Bruce of Barbara, especially in her role as Oracle, and he feels better having the young woman's help. He starts to train her.

The pair hack the personnel files of Wayne Enterprises. Bruce doesn't find anything useful at first, but then he sees a name: A. Fox, PhD. Fox is in his sixties, thinking about retirement rather than revitalizing the war on crime, but he remembers his grandfather's stories of the Caped Crusader, and he signs on. Wayne Enterprises has a few things he can put together. I can make a suit, he says, but it'll be ridiculously expensive.

My investments have been growing for nearly a century, Bruce tells him. How much do you need?

Meanwhile, the cyborg bikers roam the streets. Croc's genetically-enhanced biomutants attack the people on the surface. Lords of organized crime play all sides off each other so they can continue their extortion rackets. The cops are crooked. Feeling hopeless, many people turn to drugs or escape into complex virtual reality worlds, the evolution of the computer games of old.

Then the creature known as The Joker strikes again. This time it's the police. Inside their workroom at police headquarters, members of the special task force set up to catch the killer have turned on each other, turned cannibal, torn each other to shreds with their teeth. Only one woman survived, and she's stark raving mad.

Bruce visits her in Arkham. He breaks in through an old, forgotten door. When he hears her laugh, he knows. The creature, the cyberintelligence, it isn't some replica. It's not a program. The Joker found a way to become immortal. Bruce has to stop him.

Fox tells him the suit isn't ready yet. Bruce says it will have to do. With Evie in his ear, the new Oracle -- or cyber-Robin -- he takes to the streets.

In the wake of the massacre at headquarters, the old police commissioner has been sacked by the mayor. Newly-appointed Commissioner Jane Grayson has had a helluva first day. Someone stole the three-ton statue of the Batman right off the steps of City Hall, almost like it came to life and flew away. And now there's some commotion upstairs.

She joins her people on the roof of Police Tower. There's a crowd. Someone has installed a new light on the roof. It points to the sky. A symbol is reflected on the clouds of the night. It's a promise to Gotham's citizens. It's a warning to her criminals.

The Batman has returned.

Art by Jim Lee

September 22, 2014

The Heartbeat of the City

Released May 20th, 1971, Marvin Gaye's "What's Going On" is undeniably one of the greatest albums of the 20th Century. While superficially one long lament, Gaye's characteristic depth and soul -- unmatched on Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology) -- turn a eulogy for mankind into a call for hope.

The album's theme -- the individual struggling to find peace in the face of the corrosive sweep of history that was the last century -- can find root almost anywhere outside the rust belt of America where it was born, from war and economic decline in Europe to social revolution in Asia, from the birth of the assembly line (and its effect on work and life) to the emergence of the city as the primary home of humanity.

Which brings us to my favorite track on the album, Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler). The 20th Century saw the rise of the greatest megalopolises in history, each of which dwarfed the greatest empires of centuries past: Mexico City, Shanghai, Delhi, Sao Paolo, Tokyo, Jakarta, New York, Karachi.

Put on your headphones. Turn off the TV. Don't look at anything. Just listen.

That percussion is the heartbeat of the city, any city in the world...

September 17, 2014

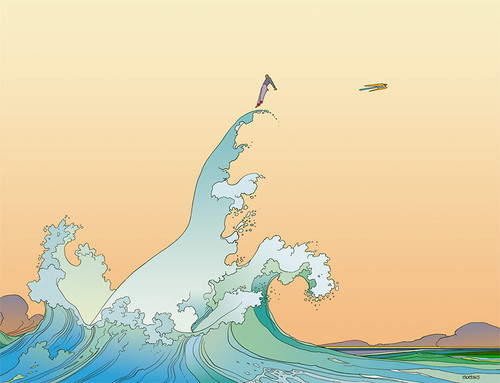

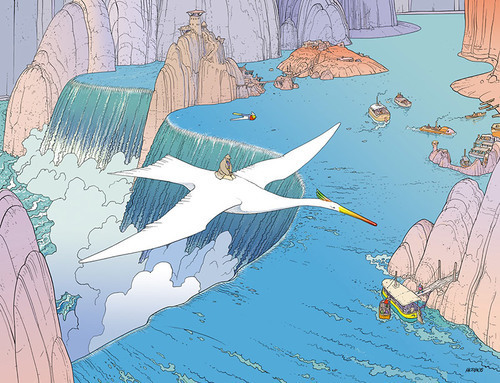

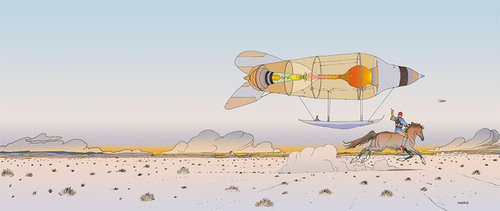

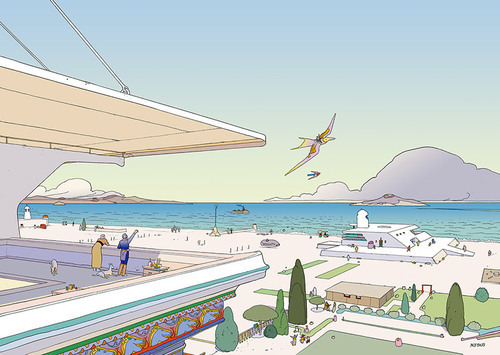

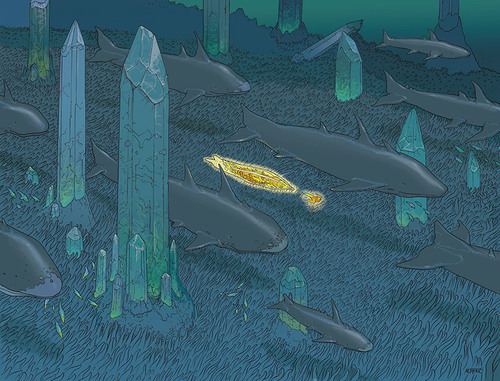

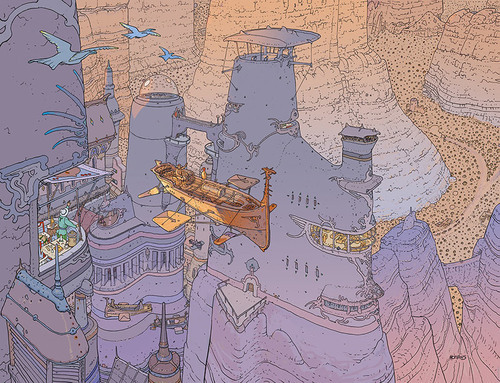

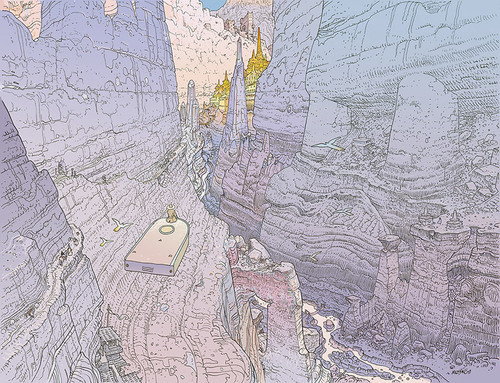

Moebius's Voyage d'Hermes

That time Jean Giraud (AKA Moebius) shilled for luxury brand Hermes Paris.

September 6, 2014

They Call Me The Asshole Whisperer

I spent my late 20s and early 30s critiquing: mostly movies & books or politics & international affairs, but also other people and their choices. I told myself that I was trying to make the world better, which is how a critic justifies it. It's worth doing, it means something, because it's a torch on the path to a better world.

It is possible to be a good critic. I've read them. But criticism -- GOOD criticism -- is as much an art as art itself, and so your average critic is as worthy of critique (of their criticism) as the artist or writer he criticizes! But sadly there are no professional critic-critics. Regular professional critics eschew it as a kind of professional courtesy (although it does occasionally happen).

So being a critic is safe, certainly safer than being a creator.

People who go around critiquing everything -- and this very much applied to me -- believe their opinion matters, that it's worth voicing, that they're smart, and that they need to be conspicuously smart so you'll recognize it. Smart people feel capable. Immature smart people have no life experience save their education, which values smarts over other things like character or even hard work. You don't have to work hard in school if you're very smart. You can just cram the night before the test and ace it.

But smarts alone only take you so far in the world, and people who get so much of their self-esteem from being smart that they need to be conspicuously smart all the time -- hence the constant critiquing -- leave school and immediately fall into the gap between their sense of their self-worth and the world's actual valuation of them.

It's a big fucking hole.

Within a few years they realize that, from the world's point of view, they've done nothing to deserve what they expect they're owed. They've achieved little -- if only because achievement usually takes time and sacrifice -- so they go around pointing out that no one else has achieved either.

Just like the loudest homophobes are always secretly gay, projecting their self-loathing onto the world, so the constant critiquer is acting out what they themselves fear: that if they created something, that if they tried to do something more than cram the night before the test, it wouldn't measure up, that they wouldn't measure up.

A good, artful critique takes time to create. As an art itself, it takes all the same effort, maybe even more. An artful critique is poetry and philosophy, educational and intriguing, informative and fair. It demonstrates mastery without having to strut. And that is something else entirely.

"But I'm trying to make things better you see."

No, you're not.

Sometime in my middle 30s, I stopped critiquing everything. I suppose I grew up a little. I realized that critiquing the world doesn't make it any better. Making the world better makes it better.

Go do that.

Art by Brecht Vandenbrouke