Rick Wayne's Blog, page 99

December 11, 2015

Constructive Interference

According to a number of studies (do a search on “music for productivity”), music that is highly engaging, such as songs we enjoy — especially those with a lot of lyrics — are good for repetitive work. This is probably because they stimulate areas of the brain otherwise deadened by rote activity, which can be accomplished largely without “interference” from our higher brain centers. On the other hand, lyric-less music, silence, or even are best when we need to concentrate, when the music we enjoy might prove a distraction.

I would like to propose a third category. In the physics of waves (including sound), constructive interference is “the intersection of two or more waves of equal frequency and phase, resulting in their mutual reinforcement and producing a single amplitude equal to the sum of the amplitudes of the individual waves.”

In my writing, music provides such constructive interference, but as the studies referenced above indicate, not all music is equally productive. In the drafting and plotting stage, I tend to listen to music that complements the characters and/or narrative I am composing, even where that music is lyric-filled and engaging. At this point in the process, I’m merely typing notes, not even whole sentences let alone a coherent narrative, and music that puts my subconscious into a relevant mood is highly fecund.

This is why each of my characters gets a theme song, sometimes more than one. For example, I looped the following song from Gustavo Santaolalla while creating my Amazon-born, French-raised shaman-chef, Etude Etranger, whose defining traits — depth, mystery, power, ambivalence, hope — find voice in the great falls at Iguazu, which arise from mystery and disappear into uncertainty, and which are never the same from moment to moment.

But my other character from South America, the superhuman Hispanic-mulatto Xana Jace, needed something entirely different, a song that captured both her life-threatening illness and the loss of her son yet still left the listener with the certainty that she could become something much, much greater. This song directly inspired the scene towards the end of Episode Two of THE MINUS FACTION where Xana, on her knees, about to be defiled in front of a crowd, decides to stand and fight despite the cost to herself and those she loves.

But highly engaging songs like this are often not what I listen to while in heavy composition. For that, I need engaging and mood-appropriate music with little-to-no lyrics to muck up my wording engine. The following song has been getting heavy rotation recently as I work on the fourth course of my occult mystery, THE HERETIC ARCANUM, which features a little boy, Olafur, around whom swirls some very unusual phenomena.

In fact, Tangerine Dream is good for inspiring words regardless of the project, as are soundtracks to movies. After all, such music was specifically composed to elicit constructive interference — to augment an audio-visual narrative rather than distract from it. Trailer music in particular worked well for Episode Four of my superhero-ish serial novel THE MINUS FACTION. It is a reminder to me that each installment needs an emotional “hero moment,” a singular crisis where one or more of the characters are given a chance to walk a difficult but higher path, and that the entire plot should pivot on that fulcrum.

Finally, there are just some songs that I love so much, they are an enjoyment and an inspiration no matter what I am doing.

So that’s a little of what I do. What do you listen to?

November 23, 2015

Cenotaph for an Enlightenment Ideal: Why Europe Really Conquered the World

A cenotaph is a marker or monument to a person whose remains are interred somewhere else. Pictured above is Enlightenment architect Étienne-Louis Boullée’s famous design for a massive cenotaph in honor of Sir Isaac Newton. It is a wonderful example of the European hubris of the age, a hubris that cast a long shadow from which we, as Europe’s manufactured cultural heirs, have yet to fully emerge.

I am finishing William McNeill’s A World History, which, despite a handful of drawbacks, continues the author’s wonderful ability to step out of that shadow. For example, to appreciate Europe for what it is — a derivative culture (like Russia), a semi-barbarous fringe that, as it civilized, grafted itself imperfectly onto the high cultures it sacked and destroyed, namely Rome, and through her ancient Greece. Europe was never a true descendant. She wasn’t even adopted. She was just a really big fan.

That we are the legacy of ancient Greece is a myth invented after the Renaissance. Its falsity is evidenced by the sad fact that many of the works of Aristotle, who provided the entire foundation of medieval Scholasticism (on which the Renaissance was built), came to Europe, not from her supposed parentage, but through Islamic science, which had preserved them from the ravages of the very barbarian peoples now asking for them back. And in return we gave them the Crusades.

I want you to think about that for a moment. It’s as if we collectively invaded someone’s home, killed the family who lived there, burned most of their belongings, and then camped out on their front lawn for a few centuries. Staring at the husk of their house every day, and getting tired of living in a tent, we start to feel a kinship with the line we ended. So we make their house our own — with some changes of course — and tell everyone we’re the children of the people who lived there. And after asking the neighbors if they managed to save any of the dead family’s belongings — luckily they had — we tried to burn their house as well. Failing that, we put up a fence and mimic the dead family’s old habits, at least as near as we can glean from a handful of pictures, and remark how clever we are for it, despite that we have no relation to those people at all.

Its not just creepy, it’s downright psycho.

McNeill is also good at avoiding the traditional trap of world history texts, which is the silo approach (see J.M. Roberts or the Durants). In other words: here’s what was going on in China; here’s what was going on in Persia at the same time; here’s what was going on in Europe after that; etc. While his chapters are geographically organized, McNeill addresses the world in one lot. Thus he can cover the rapid political consolidation that happened in Japan under Hideyoshi, and thence Tokugawa Ieyasu, in less than one page simply by pointing out that Japan was succumbing to the same package of technological, military, and civil bureaucratic changes that half a world away had consolidated Prussia, a completely novel European state, from so many princely statelets.

It’s fascinating to me because as much as Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel explained why it was that people from the Eurasian landmass were always most likely to advance quickest (versus, say, Africa or the New World), Diamond did little to explain how it was that Europe, something of a backwater in 1450 — hence the need for her to invent auspicious parentage — managed to conquer the world rather than the most advanced society on the planet at the time, which was clearly China.

That, by the way, is the main reason I have always been fascinated by the “treasure fleets” of Zheng He, a eunuch admiral under the great Yongle Emperor, Zhu Di, third ruler of the Ming dynasty. The fleets were massive, with some of the individual ships larger than the Nina, Pinta, and Santa Maria combined. Over several campaigns, they sailed as far as Africa and the Middle East, and this some sixty years before Columbus. China had a massive head start. And a ridiculous numerical advantage. And she invented gunpowder!

McNeill proposes no radical new theory explaining China’s eclipse, but he does a nice job of synthesizing some of the front runners. Of course, such a complex topic is going to see a lot of disagreement, particularly among experts, who often spend too much time pruning the trees to appreciate the forest, which is what the world historians do.

But first, it’s important to note there are different kinds of valid explanations. This rubs some people the wrong way — the dogmatically scientific in particular, who always want there to be one and only one answer to any question — but it’s real and especially acute in historical analysis, which must not only explain the cause-and-effect of why something did happen, but also why something else, which might have happened elsewhere, did not.

The scale of our explanations matter, as Richard Lewontin pointed out in his wonderfully short Biology as Ideology. Is the reason so many people died of cholera in the 19th century because they contracted a bug? Or because the economy and class structure of European capitalism prevented access to clean water by the poor?

One can give a seemingly satisfactory account of the turn in the balance of power from Far East to Far West that occurred from 1500-1850 solely by appealing to Europe’s intrinsic awesomeness — that she had the gumption to develop property rights, or a market economy, or a proselytizing faith, or whatever aspect of your current ideology you are looking to justify — and leave it there, completely omitting any discussion of why. You can do this kind of shoddy history and get major grants from conservative organizations looking for evidence that a low marginal tax rate on the wealthy is key to both national security and economic prosperity, and so make a big name for yourself.

But you’d be wrong.

One of the things science teaches us is that humans are not genetically diverse, less even than our closest relatives, chimpanzees. We’re simply too young of a species. All the peoples of the earth are, when gathered in sufficient number, possessed of the same basic faculties. There are smart, inventive people everywhere, and appeals to “intrinsic” superiority, besides being morally distasteful, flatly contradict the evidence from molecular genetics.

One can claim cultural superiority, but even if that’s true — and it’s never quite clear how we would measure it — that doesn’t really answer the question. It’s the same as blaming the cholera epidemic on a bug. If you accept that Europe’s culture was inherently superior, whatever that means, you still have to explain why or else you’ve merely passed the buck to the next turtle down.

The East-to-West turn has to be built on something solid, such as the physiography of the lands in question: their natural endowments, their flora and fauna, their diseases and disease vectors, and so on. Diamond’s book peeled back each of these layers so meticulously that it’s hard for me to imagine he might be wrong about Eurasia as a whole (but of course it’s possible). We’re on less solid ground when it comes to “why Europe and not China?”

McNeill’s synthesis is multifactorial, so those looking for a silver bullet will be disappointed. But it starts with landmass. China is effectively a broad plain centered around two massive river systems, the Yellow and the Yangtze, whereas Europe is one giant glacial scar pockmarked by high mountains — the Alps, unlike the Rockies, are still growing — and deep valleys with numerous and independent fast-moving rivers. China’s geography favors political consolidation, especially after the Grand Canal (segments dug in the 5th century BC but not completed until the Sui dynasty a thousand years later, about the time Rome was being sacked) linked the Yellow and Yangtze together. Europe’s geography does not.

What’s more, the prevalence of so many fast-moving rivers allowed for the creation of a middling mercantile exchange based on rough commodities. That is, the medieval sheep herders in the hills could afford to send their wool to market because there’s a river that takes it directly there, avoiding the exorbitant, largely road-less cost of land transport, as well as any kind of central canal system where commodities would be taxed by both middlemen and the sovereign. The goods brought to market in China, such as silk or that country’s famous porcelain, were predominantly for the wealthy since they were the only people who could afford to buy at market price. Goods bartered in Europe on the other hand included items common folk could afford, such as coarse woolen cloth, and this proto-middle burger economy, underwritten by geography, tilted power subtly away from central authority, especially compared to China.

Take Magna Carta. One has a hard time imagining a group of nobles squeezing such protections from the Chinese Emperor. But even for all its significance, Magna Carta applied only in England, one country in Europe — and at the time not even a very important one — whereas the Son of Heaven ruled all that he could see.

Furthermore, China’s advanced arts and sciences as well as her abundant rain fall — rice requires significantly more water than wheat but also produces significantly more calories per hectare — and proximity to the spice islands meant that there was little to interest her in the world. Zheng He brought nothing back that the Chinese coveted. In fact, he confirmed their suspicions that they were the Middle Kingdom, the center of the earth. When later Ming emperors tallied the cost of the treasure fleets and dismantled them in favor of a Great Wall and land-based military to protect her border with Mongolia, they made overseas travel — and the import of dangerous ideas — illegal. China’s political consolidation meant the entire nation had to comply. That no aristocrats significantly objected, or turned secretly to piracy, shows just how little they believed the rest of the world could inflate their position at home. China was just that far ahead.

By comparison, Europe was so politically (and religiously) fractured that she had no hope of ever mounting a coherent response to the Ottoman Turks, who overran the Christian Byzantine Empire in 1453, right about the time the Ming outlawed overseas travel. That gave the Muslims a foothold in the Balkans, and thereafter they inched closer to Vienna. But it also meant that, when a firebrand Christian fundamentalist couldn’t get support for his crazy ideas from his own sovereign, that wasn’t the end of it. He had choices. He could peddle his plan to conquer the Holy Land next door in Spain, who gave Columbus three ships. (His ultimate goal, by the way, was exactly conquest, but not of the New World. A short route to the spice islands would be lucrative and could finance a huge army with which to finally realize the Crusaders’ dream of a knife in the heart of Islam.)

Europe’s dense forests, rocky soil, and cool climate, especially its significant annual cloud cover, meant that much of the rare fruits and spices — pepper, bananas, sugar, etc. — that the wealthy so coveted couldn’t be grown. They had to be imported. Europe was just impoverished enough to make her covet her neighbors’ wealth, and after Columbus, she found much in the world to tempt her. What followed was an explosion: Cabral, Magellan, de Gama, Pizarro, Cortes, and so on — an arms race of discovery, not to conquer but to provide exactly what the Chinese didn’t find: wealth and leverage for the political struggle back home.

But Europe had a problem. China’s ample but dirt-poor peasantry ensured a steady supply of forced labor such that her aristocrats had no need to augment it with either machines or slaves from overseas. By contrast, Europe’s agricultural base, determined by her climate, couldn’t approach the Chinese model. Europe’s numerous swift-moving rivers, however, gave her an easy means of augmenting her labor deficits by harnessing the power of gravity — first in the form of highland mills (closer to the sheep, you see), which later provided a mechanical knowledge base upon which to realize the steam engine. Personally I’m not at all surprised Watt was a Scotsman.

But just as the Europeans began their penetration of the globe, the geographic separation of the New World tribes ensured their utter decimation at the hands of diseases that had long since become endemic across Eurasia. The Americas offered a bounty of natural resources, and enough silver to trigger a price revolution that stretched all the way to Japan. Yet, while the local peoples were incapable of mounting a defense — a circumstance that had never before in the history of the world faced a group of would-be conquerors and which arose, not from European inventiveness, but from complete geographic and biological happenstance — the lands those peoples now sparsely inhabited were absent the labor necessary to exploit them.

The European solution was cruel but effective. The combination of slavery and automation proved so ruthlessly efficient that within two centuries England could purchase slaves from Africa, ship them at heavy losses across the Atlantic, ship the cotton they grew to the textile mills back home, and ship the finished product from England all the way to India, and still undercut the price of locally-produced cloth. (No, globalization is not new.) It’s easy to imagine a more humanitarian solution would not have put Europe on such favorable terms vis-à-vis the rest of the world, and if European culture contributed anything unique, it was to extend the application of technologies invented elsewhere to their cold-blooded extreme: slavery, gunpowder, disease.

China, for her part, remained completely content at home — although no less brutal to her peasantry — and necessarily ignorant of what was going on in the Atlantic. When she abandoned overseas travel in the 15th century, Korean and Japanese pirates quickly invaded her coasts. When the Portuguese, with their superior ships and weaponry, displaced them in the 16th century, the Chinese barely took notice. To them, one group of barbarians had simply supplanted another. Smart, reasonable governors saw no reason for alarm because, as McNeill notes, there was none. There was no grand European plan, no hint of conquest. At each stage of the story, there were only people making the best decisions they could with what they’d been given, which is why understanding what they’d been given is so important.

Of course, I’ve hardly given the whole story, as if I could cover it all here! It’s important to remember that, even as late as the Napoleonic Wars, it was far from certain that Western culture would prove so enticing and corrosive that the Chinese, even as they cast off overt British rule a century later, would replace the political theory of Confucius, which had guided them for over two millennia, with that of a European, Karl Marx. (At least, for a time anyway… Hint hint.) We must remember that nothing is set and change always a possibility. At each era we must understand the why as well as the why not, and we must never look on the past as determined. For it was to those who lived it as the future is to us now.

However, I hope I’ve given you a taste of the kinds of novel scholarship now emerging from the long shadow of Enlightenment hubris, where the best explanations, even into the late 20th century, were some version of “Europeans are just intrinsically awesome.” Let’s hope the point of view implied by Boullée’s cenotaph is as dead as the man it honors.

November 16, 2015

A Measure of Sympathy

The second wave responds to the iniquities of the latter. Someone inevitably points to the numerous other tragedies, often very recent — tragedy is a near-constant in this world — with a higher death toll but less attention-grabbing circumstances and therefore on which everyone was silent, the implication being that people are hypocrites for caring about the one and not giving a flying fuck about the other.

I would like to suggest there is a difference between caring about everyone and caring about everyone equally. The former is humane, the latter simply inhuman. It’s natural, for example, that I should be moved by my brother’s motorcycle injury more than an acquaintance’s, even where the acquaintance’s was more severe. And we would think someone mentally ill who, passing the site of a lethal accident, jumped from their car and collapsed in tears over the death of a complete stranger. That most of us remain in our cars is not evidence that we don’t give a shit.

Attacks in the industrialized West are going to garner more support and sympathy from Western people than attacks in, say, Africa or even Russia. In fact, I suspect an attack in some place like Bulgaria, which is geographically and culturally intermediate, would see more coverage than Africa but less than nearby Germany.

Allied nations tend to be both culturally similar and operate within the same geopolitical economy. (Hence the need for an alliance.) Suggesting that we should react the same to a tragedy in Uzbekistan as in France is saying we should react the same to a home invasion in rural Wyoming as to one in our hometown.

Yes, it’s certainly true that more people died from influenza today alone than in Paris on Friday, and that the same is true of automobile accidents, heart disease, and a bunch of other nasty things. But those are generally known and understood phenomena. What’s more, they are absent human agency (flu) or result from our conscious lifestyle choices (car accidents).

I don’t think it’s unreasonable to be shocked by deliberate murder in an area of presumed safety, even in cases where there is only a single victim, especially if that victim is both an innocent and physically close to us, such as a child in the apartment building we pass every day on our way to work.

Lastly, I doubt any of us will have the same reaction to our failure to exercise, or when we might have eaten too much, as to the sudden onset of a cold, and yet the cold won’t kill us whereas overeating and lack of exercise will. School shootings and terrorist attacks present a similar face, despite that gun violence is active and ongoing.

HOWEVER, with that said, there is often clearly a bandwagon effect to this stuff, and frankly it’s hard for me to stomach a bunch of hand-wringing over, say, the disappearance of a single newsworthy child, from people who seem completely oblivious to any tragedy that isn’t also popular.

For example, I would be curious to know how many people died in the French retaliatory airstrikes over the weekend. Has anyone even bothered to count?

All these things are tragedies, and they need not affect us equally, but that doesn’t mean our behavior, as the best evidence of our beliefs, isn’t morally problematic. Sometimes it really is. And sometimes we don’t like to hear that. And sometimes the people who say it are assholes using a tragedy to flaunt their presumed superiority.

In the case of Paris, it really is — despite what some people are saying — one more episode in a large pattern of alternating violence that stretches back at least 1200 years. (Or have we already forgotten je suis Charlie?)

I don’t say that to minimize the event at all. Just the opposite in fact.

Until we appreciate the genuine root cause of the problem, we will by necessity ignore actual, often difficult solutions in favor of political and emotional conveniences, and in so doing ensure something like this will absolutely happen again.

And again.

And again.

And again.

And again.

And that to me is an even bigger tragedy, and one we can yet do something about.

Until then, all my best to the French people. This fucking sucks.

November 15, 2015

The Sheer Limits of Disgust

It’s remarkable to reflect on how much disgust completely permeates our lives, from the lowest form — yuckiness — all the way up to moral disgust. It is especially remarkable considering the only innately disgusting artifact appears to be spoiled meat. Everything else, from piles of dead bodies to handling human feces to eating the brains from a live monkey (which happens in China), is learned and therefore highly variable between cultures.

Being in Japan, I can definitely see the differences, at the 30,000-foot level, between East and West — the sensitivity to bowel movements, for example, which Rachel Herz notes in her book That’s Disgusting (which I’m reading now) is particularly anathema in the western world to a degree not often encountered elsewhere. A Japanese man, Taro Gomi, can write Everybody Poops, and a major museum in Tokyo can have a whole interactive exhibit on poop and it’s no big deal.

But that’s mere ickiness. More interesting to me is moral disgust, which Ms. Herz notes is probably something closer to anger justified as disgust — at the breaking of a tabu, for example, which exist in every culture and are usually handed down from God (or liberal elite thought-leaders) and are therefore more sacrosanct than natural law.

Orine and I watched part of a sketch comedy show the other day the gist of which involved a 45 year-old man interviewing and then hitting on three women aged 23, 25, and 21, something that I know would “disgust” a fair number of people back home, which is to say anger them.

I even looked at the show sideways at first until I realized it was basically a set up to make fun of the man, who is a professional comedian. All three women shot him down.

Orine and I are 16.5 years apart, so it’s something I’m very sensitive to. In fact, I expressed a great deal of reservation at the start of our relationship. When I met her two years ago, I wouldn’t even consider it. Not that I haven’t gone out with women her age before. I have. But it was never serious (for either party), and that to me is a big difference.

She explained a number of times that, while not exactly common here, such an age difference wasn’t necessarily that big of a deal either, and that I was making it weird (basically — my word, not hers) by bringing it up all the time. I have since stopped.

In fact, I hadn’t thought about it at all until we saw that show about the same time I started this book and the intersection led me to some lengthy cafe ruminations today on disgust and tabu and how they define their reciprocal entities: norms/mores and, subsequently, social approval.

I’m no stranger to this topic. I started researching disgust in earnest while working on my first novel, FANTASMAGORIA, which uses the grotesque to advance the plot and underscore the action, and while I was writing it I also curated a collection of the most disgusting and offensive images on the Internet and posted them every Friday at midnight — medical abnormalities, deranged corpses, crime scenes, deviant sexual practices, “transgressive” art, insults, sacrilege, and so on. I would then count the number of people who stopped following me and post it for all to see the next morning.

There was never a mass exodus. In fact, I think the record was a mere eight people. That was the point and the lesson (besides the obvious entertainment value): there is no common sense, as there would have been a century or two ago, despite everyone’s repeated admonishment that they are its sole remaining possessor.

The fact is, we all draw the line in a slightly different place, and most weeks my efforts saw a very mixed bag of reactions. People who cheered me on at first would later be unmoved and then either tune out or find that I finally crossed a line — such as a woman drinking horse semen (right from the source!) or a cartoon making fun of soldiers with PTSD. They would usually persevere until I crossed a second line, at which point they felt “icky,” almost as if they were contributing in some small measure to the activities presented, many of which were not consensual.

(I never posted the outright abuse of animals or children for the simple reason that I can’t handle that myself. I did however depict some art that represented underage girls, some of the more thoughtful of which can be seen in major galleries and some of the baser of which took me to some very dark places on some very dark networks.)

But despite the death of common sense, some general themes emerged. For example, English-speakers, which comprised the vast majority of my audience, generally reacted more to rape than to murder, even when the latter clearly involved rather lengthy pre-mortem torture, such as being skinned alive (which Mexican cartels still do, continuing a long tradition in that country). Culturally, English speakers are descended from Protestant — particularly Puritan — stock, and since disgust is learned, not innate, therefore the forceful insertion of a foreign object into a vagina (or anus, in the case of a man) generally evoked greater disgust than the forceful insertion of a blade or hangar wire into an open eyeball. It’s apparently worse to take someone’s “purity” than their sight, or even their entire life. I’ll admit to not understanding that one.

For the record, my own personal view is that I’m not sure such things can — or should — be ranked, and that those who try tend to be projecting their own unresolved trauma on the rest of us, a topic I have written on before.

As with my Friday night tests, I don’t have a conclusion to this. I’m not trying to bring you around to some particular point of view as much as poke you in a sensitive spot you might not have realized you had, and therefore to stimulate — in the reflective among you anyway; there’s no reaching some people — a wider appreciation of a world which admits of a great many more points of view than yours.

Reconciling them remains the significant unfinished legacy of modernity.

November 9, 2015

The Asshole at the End of the Lane

I suspect that growing up we all had the relative or friend in school — or maybe it was you — who liked to take things apart, the kid who, if left alone for a few minutes, would have someone’s favorite toy disassembled on the living room carpet, or maybe the remote control to the television right about the time your dad wanted to watch the big game.

I’m not talking about the kid who broke things. He was just a dick. I’m talking about the kid who wasn’t happy with the toy car until he could take it apart and get a sense of how it worked, the kid whose favorite subject was shop or maybe art class, and who learned better from pictures than from words.

I’m that way with stories. In fact, you might have noticed I don’t often talk about the books I read, even though as a writer it would totally make sense for me to do so — like Scorsese on film or a professional athlete on the state of the league.

But I have learned (the hard way) that taking a story apart — regardless of how many times I repeat that I enjoyed it — still comes across like criticism. It doesn’t matter that dissection is fun for me, that it’s part of my enjoyment to rip it open and see how it works, how it all fits together, to appreciate the subtext, to interrogate the myth.

The fact is, you can’t go around disassembling people’s toys and expect them to be happy about it.

Also, I hate pointless criticism and negativity. I can’t sit listening to someone bemoaning some movie or song as “the worst piece of trash ever” or otherwise making it clear that anyone who worked on it is a hack and anyone who enjoyed it a fool — or worse, a moron — because they don’t share the refined aesthetic sensibilities of the speaker.

So I made a deal with myself. “Rick, you jerk, you can open your mouth only to ask questions, or to make brief, factual statements, or to express enjoyment, but if you are going to take something apart in public, you have to put enough effort in that you’re sure it’s criticism of the academic rather than vulgar kind. And you’re still an ass for doing so.”

Here’s the deal: Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane is a song in praise of mediocrity. It is a well written song, concordant rather than discordant, but carrying a lazy, disheartening tune, and I reject it.

But first, just to get it out of the way, he is a much better writer than I am. Certainly I’m something a lot closer to what I fear than what I hope. Also, I should say I am otherwise a twenty-year fan of his, having started Sandman somewhere around issue #7 and collecting a nearly complete set.

And Ocean has some redeeming qualities, in addition to said lyric prose. It’s short, for example, and easy enough to get lost in, which is not easy to pull off. Any pothole or speed bump throws a reader out of a story, and Gaiman weaves around any impediments gracefully.

Of course, some of my criticisms are going to be mere matters of taste, and so there’s no point in listing them all. For example, the plot resolves with a big, fat deus ex machina, like something out of a 2,500-year-old Greek tragedy. (A goddess appears at the last minute and fixes everything.)

Now, I don’t think Mr. Gaiman wrote himself into a corner, which is the charge usually levied at writers resorting to that tired device. I give him enough credit to suppose he did it intentionally. I find it to be lazy, tension-less storytelling all the same.

Indeed, it is Mr. Gaiman’s stature as a writer along with the mythical, fairy tale-ish nature of the book that are the surest evidence that he meant to give the thing a point, and it’s the point I found so distasteful.

Stories intended to be myths, those with transrational meaning like the Bible, will have any number of interpretations, but it’s hard to say that the authors of the canonical Gospels, regardless of whatever else they were trying to do, did NOT intend Jesus’s message to be one of hope and redemption for the lowest members of society. (See comments about camels and needles.)

I can get behind telling lepers, slaves, the destitute, the castoffs of Hellenic society that they have intrinsic value, that God loves them, and that there is hope. That’s a wonderful message for people who are being told the opposite every day of their lives.

Paul had a different audience. His task was to wrangle the disparate churches that had sprung up around the Mediterranean, to resolve doctrinal squabbles, and to set a focus. Whatever else is carried in his Epistles, he surely meant to remind people that even though Jesus’s sacrifice redeemed the world, sin was still bad, and that someone who truly had Christ in their hearts genuinely doesn’t want to sin, even though they may sometimes fail.

In other words, even the redeemed still have to put in effort. We have to try, genuinely, to be the better versions of ourselves, even where we know we won’t always succeed, lest we set evil loose in the world. I can get can get behind that message as well.

I will always have difficulty with the message that it’s okay to be shabby, that you are who you are and you can’t change and so you shouldn’t even try, and that even the lazy and privileged deserve the universe to intervene on their behalf.

The unnamed narrator of The Ocean at the End of the Lane is a (presumably) white, middle class male from a wealthy country (England), and while his family isn’t wealthy, they’re far from destitute. In fact, the biggest sacrifices they have to make are live in an older house and have their children share a room to accommodate a boarder (for a little extra income).

On par with leprosy, that.

In fact, by the end of the book, Mr. Gaiman is explicit that even these modest financial difficulties resolved and life went on for this family more or less as middle class Westerners feel entitled it should.

The troubles start when the nameless narrator — admittedly, a child — fails to follow instructions from a goddess, which results in all kinds of genuinely bad things. Fine. He is a boy of seven. And bad things happen. But then neither he nor any other character ever tries to make up for it. In fact, he doesn’t do anything except cause more trouble and mope about feeling bad about all the trouble he caused.

As an adult, remembering all these events (and relating them to us), Gaiman’s narrator comes to the conclusion that he didn’t change because he was seven, but that people don’t change anyway, that we are who we are and the universe is how it is and there’s not a damn thing anyone can do about it. It is the perfect argument to never turn off your television.

In other words, if who we are is rather shabby, if we cheat on our spouses, if we’re spoiled, if we act petty with others, or don’t do much of anything with our lives or work in any way to help other people, especially those less fortunate — all things appearing in the book — that’s not just okay, we’re still entitled to Jesus’s sacrifice. We don’t, as Paul urged, actually have to bring Christ into our hearts, or put in any effort, or even follow God’s commandments.

We’re special.

Which is fine, I suppose, if you want to be a couch potato Daoist and simply accept whatever befalls you rather than, say, the stoner who complains about his lot but does nothing to change it. But the climax of the book, the big resolution (and as a reminder: I credit Mr. Gaiman with enough skill to be both thoughtful and intentional) is that a goddess sacrifices herself to save the narrator so that he can go on to live, as is described in the beginning, a perfectly lazy middle class European life, full of the same wasted opportunity as the rest of us.

I will never, ever, ever, ever truck with that, not from the mouth of someone at the top of society, not in regards to such a comfortable character, not at the implicit expense of anyone infinitely more deserving, not when it would have been SO EASY to have the unnamed narrator exhibit some tiny aspect of mankind’s capacity for good — abortive though it is — instead of being an ordinary, self-centered little worm.

There is nothing redeeming about a message of redemption for the privileged, that laziness (like resorting to deus ex machina in your writing?) is a worthy call for divine sacrifice, that not only should you not expect to be perfect, but Paul was wrong and you don’t even have to try. You’re just that special.

Fantasy indeed.

October 26, 2015

Chit Shat From Japan

This is an ongoing, updated list of my pictures and essays on Japanese culture and food. Most links are to Ello since I love how the platform lets you tell a story back and forth in images and words. All posts are public and should be visible to anyone, even those without an account.

(A chit, by the way, is a brief official note, memorandum, or voucher.)

General Culture:

The Identity Politics of Fandom From Afar (or, Japan Isn’t It’s Pop Culture)

Asakusa Night Photography: Part 1; Part 2

Popular Japanese TV Persona Matsuko Deluxe, cross dresser

Notes on the Japanese Aesthetic: Wabi Sabi; Kintsugi

Shunga (Traditional Erotic Art): Main post; Addendum

Thoughts on Cake After a Month in Japan

Sasebo, Japan (A Letter from my Grandfather, December 4th, 1945)

A Note About Cultural Difference in Intimacy

Nissin’s CUPNOODLES Museum; Addendum 1; Addendum 2 (Orine and Me)

Tokyo Exists in Three Dimensions

Photobook:

Kamakura 1; Kamakura 2; Kamakura 3; Kamakura 4

A Stroll Along the Kanda River

Japanese Food:

Home Cooking: Dinner 1; Dinner 2; Dinner 3;

Natto! (Fermented Soybeans)

October 22, 2015

Who Are the Superheroes of the 21st Century? (And a New Release!)

When I started working on THE MINUS FACTION, I decided that I wanted way more realism than you would find in a standard comic book. I also wanted to avoid mere replication of the classic superhero canon, which is to say:

-a (usually white) male meta-human prince (Superman, Thor, Namor, Black Panther, etc.)

-a (usually white) male titan of industry (Batman, Iron Man, Green Arrow, and so forth)

-a (usually white) male accident of occult science (Flash, Spider-man, Hulk, and many more)

Nor did I want them to be simply female versions of those things — or worse, mere knock-offs like Supergirl, She-Hulk, Batgirl, Spider-woman, and the rest — for as much as Wonder Woman was an advance, she still reinforced traditional race and class divisions. Diana rules because she’s best fitted to because she’s an aristocrat: as ennobled of character as of physical strength. And is anything whiter than a star-spangled master meta-race of mythologized Graeco-Roman-European-Americans?

I think not.

The old heroes, as Mal McDoom notes in Episode Two, are fundamentally conservative power-fantasies where we as readers project ourselves into the entitled and beautiful classes to do battle with external threats: Nazis, aliens, supervillains seeking to enslave mankind. That kind of thing.

To be fair, some of that is born of necessity. It’s hard to write Superman directly into any actual historical event as his involvement would necessarily change the outcome. And then there is the commercial necessity of not offending your readers, only half of whom are likely to share your politics on any given subject. Thus you have to keep your evil as ecumenical as possible, something that threatens everyone rather than one or another segment of society. An invading force from across the sea (or another dimension) fits that bill nicely.

But more importantly, we like our mythic superheroes to be exactly that, mythic. The exploits of the superhuman Gilgamesh were read aloud at the Babylonian New Year, every year, because his story exists singularly outside linear time, rather than for a mere moment as our lives do. The Babylonians didn’t experience the epic as we experience an audiobook, or even a biography. To them, it represented mankind’s climb from barbarism — symbolized by Gilgamesh’s accord with the wild-man and near-equal Enkidu — and our ultimate mortality. These were timeless truths whose lessons needed to be continually reaffirmed as part of the annual cycle, the eternal return.

This is why superhero stories are so often rebooted, and no one ever really dies. They are mythic, not linear. They gain their power not by advancing from cause to effect and ultimate end, but by being told and retold, Just like the parables of Jesus or antics of Krishna, Peter Parker must keep learning, over and over, that with great power comes great responsibility, because his is a parable of entry into adulthood, and the more the story deviates from that, the worse it tends to be.

But despite all those good reasons, the fact remains that you rarely see superheroes directly tackling actual problems normal people face. Poverty, for example. Or racism. If present, it’s usually a side note to the story, something that’s noted on the way to or from the fight with the bad guy, something the superhero could get to if only he weren’t so busy constantly battling a more immediate (but ultimately toothless) evil. As much as Bruce Wayne or Tony Stark might sacrifice for the rest of us, at the end of the day, they’re still princes, just like Gilgamesh or the Buddha. They still retire to a secure and private castle full of servants and luxury and beautiful companions where they don’t actually have to rub elbows with any of the people they just saved from imminent doom.

That all sounds very political, but really I’m not aiming for it to be. In fact, with THE MINUS FACTION I wanted to explicitly avoid the implicit politics we inherited in the myths of the 20th century. I wanted a clean slate. So I asked myself “Who are the superheroes of the 21st Century? And what would they face?”

Coming up with challenges is easy. Just read the news. Wealth inequality. Environmental decay. The use of technology to control and suppress rather than enlighten and empower.The loss of authenticity that follows the loss of autonomy that follows the loss of privacy.

Of course, starting fresh doesn’t mean reinventing the wheel. Archetypes resonate for a reason. So right away I knew I wanted — indeed, I needed — a character who was super-strong. Physical power is the purest, simplest superhuman trait. It was also clear, in answer to my question, that a super-strong character in the 21st century should be female. But that left me at immediate risk of knockoff syndrome, of creating a superficially female tough guy: a butt-kicking, name-taking celebrity/scientist/entrepreneur/princess who undergoes a super-powered transformation that reveals or mimics her “true form.” Ben Grimm was the kind of guy who would give you a clobberin’ long before he became The Thing.

I love inverting tropes. It’s what I do best. There are so many weaklings-turned-strong. Why not make the super-powerful character powerless? Such a person would be resisted, especially if that person were female in a poor country. (Let’s face it. In the era of rapid globalization, all the heroes can’t come from North America, even though that is my major market.) The social structure abhors a deviant, after all.

No, you aren’t a deviant. Not really. The social structure lets you think you are to keep you from being an actual deviant, such as a pedophile. The social structure first tells deviants that really they’re not. “You’re not really gay. It’s all in your head. We can cure you.” Failing that, the social structure resorts to threats, followed by actual violence.

But actual violence doesn’t work so well against a woman who can curl Volkswagens. So the social order tells her, “You’re not really super-strong. It’s all in your head. We can cure you.” And that is the origin of Xana. From Guyana. A country in the AmaZON. Named after the mythical all-female race.

Of course, a lifetime of being shat upon is not something you just cast off in one day, even a day where you beat Boraro the Disemboweler in a single blow. It takes a little more than that. Like having a city bus dropped on your head…

I took exactly the same approach with John, but where Xana’s inversion is psychological, his is physical. Every superhero team needs a super-warrior, of course, someone trained in actual combat. Otherwise there’s not much hope anyone would survive, at least not in the real world. But how to make that new?

By making him a contradiction, a man whose physical realities are at odds with his potency and whose power is at odds with his conscience. Not Steve Rogers, weakling-turned-hero, but the opposite, the inversion: Captain America turned weakling

After John, I had a clear strategy and coming up with my team got easier. I knew I wanted to have a genius, a master architect (often of questionable morality) who serves as the foil to the conscience of the team: Batman to Superman, Iron Man to Captain America, Ozymandias to Rorschach. What’s a bigger contradiction/inversion than putting that ability in the body of an eleven-year-old girl?

Excuse me, eleven-and-a-half.

Where Xana is the heart of the team and John the spirit, Wink is the brain. That left only one thing: the folly. And since every great team is bestowed from beyond — Thor’s hammer, Green Lantern’s ring — it made sense (and was another contradiction/inversion) to put the most power in the body of the least competent: an everyman.

But that creates an immediate imbalance. If Ian’s abilities were under his direct and conscious control, he’d be more than a match for anyone in my slightly-more-realistic superhuman universe. On the other hand, if his powers merely manifest at random, the character becomes a mere vessel, and that strays awfully close to deus ex machina, a plot device I abhor. (His powers, if not under his control, would need to keep appearing ex nihilo to save his life.) But more to the point, it’s hard for readers to root for an inanimate object. Ian-as-host becomes an annoying distraction.

My answer was to put his abilities under his autonomic rather than somatic nervous system — which meant he could only get at them indirectly — and to make their use a genuine threat to his own safety so that he couldn’t just keep whipping them out all the time. And I even snuck in a reference to Mjolnir. In Episode Three, the Professor mentions the Oric was named after the Bronze Age god in whose statue it was found, and that the meteor-like vessel that brought it to earth would have appeared to those Bronze Age people as if their god had smote the sky with his hammer. (Then he adds, “I think we were meant to find it.”)

But it’s the formation of the team, how they are brought together, that most directly answers my question — who are the superheroes of the 21st century. It’s not what you think. At least not yet. You’ll have to wait for Episode Five: Aftershock to discover the truth. Let’s just say that team really is a four-letter word.

Before that, we need to see the gang in action together, both for and against each other. Episode Four: Blackout sees John vs. Ian, Xana vs. Wink, and all four against a resurgent menace, including everyone’s favorite psychopathic bolt-thrower alongside a new enemy: a former Royal Marine and current paranoid schizophrenic who may be the only person on the planet stronger than Xan.

All Deadbolt and Brickbat need is the cover of darkness, which the team accidentally provides. And I promise nothing is the same after.

Episode Four: Blackout, available now!

October 18, 2015

Notes on the Japanese Aesthetic

I am not the world’s biggest Japanophile. I enjoy the country for its foreignness and follow The Economist, which said that the greatest experience of being foreign — for the Westerner anyway — still comes from time spent in Japan. But I don’t lust after her mysteries. I am a casual explorer. A one-night stand rather than a seasoned lover. I’m here because my friend is here and because he’s possessed of that most treasured asset: a free place to crash.

I first visited in 2001 when he was teaching English in Kyoto. (He is now a researcher at the University of Tokyo, having since completed his PhD in Applied Math.) I returned in 2013 after the dissolution of my marriage — simply because I needed to get away, and nowhere on earth is more away than Japan — and used it as a launch point for a tour of China. Eighteen months later, I returned and fell in love.

Now on my fourth trip to the country, and entangled with a native, I am just beginning to orient myself, to let slip that sense of foreignness, even if just a little, like a loosened kimono. Nihon and I have gotten to second base.

Take wabi sabi, the difficult-to-translate traditional Japanese aesthetic. Wabi originally evoked the loneliness of living remotely in nature but has since evolved to reflect a pastoral or rustic simplicity somewhat akin to Shelley’s romanticism. Similarly, sabi, once the withering of age, now connotes its serenity — an appreciation for imperfection and the implied wisdom of experience, like the pleasing softness of the natural-worn holes in your favorite pair of jeans.

To understand wabi sabi, you need to understand a little about yourself — assuming you are also gaijin — if only to appreciate the contrast. So take a moment and feast on this painting by (arguably) the most famous artist of the Western canon, Vincent van Gogh:

It’s opulent, as most still lifes are, whether of ripe and rare fruits or a cornucopia of flowers, like this.

From the nude to the landscape, classical Western art is nothing if not lush. Fecund. Exuberant. And what is a portrait if not a very expensive selfie? (No, we didn’t invent that.)

And we don’t need to restrict ourselves to the aristocracy, as in Willem van Haecht’s “The Gallery of Cornelis van der Geest” (above). Take this middle class Flemish home as painted by Frans Francken II, ca. 1615.

The painting at the center, which features a Madonna and child in the New World, where this man presumably made his fortune (note the feathered headdress), is clearly his prized possession, with the second being his wife and third his rare imported pets (also clues to his New World fortune).

The man’s son, who would take his name and carry on the family tradition, is naturally behind him as a successor, rather than a loved one, should be. His daughter, if he had one, is not even present, although he does manage to sneak in a shot of his bedroom. Proud of that, apparently.

Note the jewelry in the cabinet, the nod to Graeco-Roman statuary in the miniatures, the near-absence of any real religion (that being confined to themes in the paintings in the painting rather than the painting itself, which would have been the case a century or two earlier), and finally the luxuriant bouquet on the table, which is both larger and more colorful than the man’s own offspring.

And here you thought Americans invented conspicuous consumption. Nay, we were merely handed that torch from Europe. (But we do it better.)

Compare that bouquet, and van Gogh’s, to this one:

Flower arranging is one of the classical arts in Japan, and you will often see more than one bloom, but this is certainly not atypical, and it is very representative of wabi sabi. The natural beauty of the flower — the wabi (rustic simplicity) — is the focus, not to be overtaken by the vase, which is itself earth-toned and “pleasingly imperfect” (sabi).

The tea ceremony, probably the most purely Japanese activity ever invented, features a simple sweet, usually in the shape of a flower, served individually before and as a complement to the bitter tea. But both are consumed on their own. Just as the vase does not detract from the flower, both the sweet and the tea are the focus of their own singular moment.

When you accept this sweet from your host, you will be seated on tatami, as in the picture, meaning there’s no chair, no table, usually no decoration on the walls of the tea house. Rather, there is only a carefully crafted view of the host’s garden, which will itself be pregnant with meaning.

The tea will be served in cups decorated, if at all, with a simple but elegant (natural, wabi) motif and — in the best ceremonies — featuring pleasing and intentional imperfections (sabi) meant to invoke the scars of experience, the patina of long use, the wisdom of age (having derived from the Buddhist concepts of emptiness and impermanence).

Note the lip:

You see the same mode of construction in every other traditional Japanese art form, from music to Noh theatre to painting to archery to jujutsu, which uses an economy of movement and an attacker’s own momentum for defense, like the flow of a river or the wind through the leaves.

“Maple Leaves” by 瀧和亭 Taki Katei (1830 – 1901)

That is wabi sabi. And although modern Japan has in many ways expanded and evolved it beyond its minimalist origins, it is still very much the pounded earth on which the Japanese world view is built.

For example, even now, the Japanese by and large don’t use credit cards. It’s unusual that a merchant even accept them (the international retail chains being the exception). You carry and pay in cash. The packaging around what you buy is immaculate. The salesperson will fold your item and/or place it in a bag inside another bag and seal it with tape. The serving size is appropriate. And you buy only what you need.

It may sound like I am advocating. I am not. I am merely describing. At home I buy bananas almost every week. One or more will often spoil. I tell everyone that I am not buying bananas. I am buying the option of bananas, should I want one. And that is the difference.

You, of course, can decide for yourself.

(.gif adapted from an image in the Japanese design journal Shin-bijutsukai, 1901-02.)

tea bowl repaired by the kintsugi method — using gold (or other precious substance) to accent rather than hide prior damage, to celebrate the vessel’s history rather than obscure it.

October 13, 2015

SHUNGA! The Art of the Woodblock Money Shot

Last Sunday, my buddy and I went to see an exhibit on shunga, traditional Japanese erotic art, mostly dating to the Edo and Meiji eras. The term shunga translates as “pictures of spring”, a euphemism for sex, and many of the works were similarly titled — “Placing the peach in the golden vase.”

It’s difficult to describe the Japanese attitudes on sex. On the one hand, there were many more pictures of this type produced in Japan than similar works in Europe, and they were created by some of the greatest artists of the time, including Hokusai, whose famous wave off the coast of Mount Fuji is a global icon for the country.

On the other hand, sex is still considered somewhat “shameful,” and these pictures would not have been openly displayed in the home (as erotic art was in ancient Rome, for example). Consider that this very exhibit only took place after a successful curation at the British Museum — it was their idea — and that no major museum in Japan would host it. They all thought it disgraceful to show this art in public.

To see it, you have to go to the Eisei-Bunko Museum — Bunkyo is a ward in the city — a little archive in northern Tokyo that houses the documents and artifacts of the Hosokawa clan, one of the more important aristocratic families from the feudal era. Their regents were a little more daring. No one else would touch it, even in the Twenty-first Century. (Indeed, when I said I was going with my buddy, my Japanese girlfriend looked at me cockeyed and asked, “Do you like that?” I explained that I wasn’t secretly masturbating to 18th century Japanese woodblock prints in the bathroom.)

Japanese views on sex are complex, and after several years and multiple visits dating back to 2001 — I was in Kyoto on 9/11 — I still can’t explain it very well. It’s best not to think in terms of our Victorian dichotomy: open or repressed. Sex is not repressed here. But it’s not open either. Rather, it’s a completely unique cultural expression with its own norms and mores.

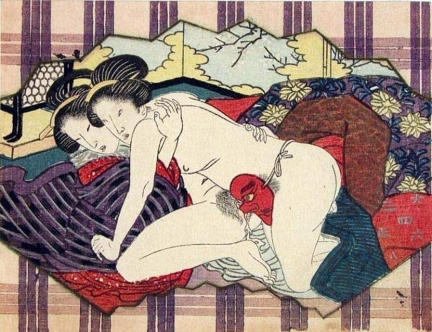

Most of the works in the exhibit, like Hokusai’s (below), were woodblock carvings that were then used to make high quality prints, and it’s the prints that are on display rather than the work that actually came from the artist’s hand.

“Manpuku Wagojin (The Gods of Intercourse)” (c.1821) is a series of shunga by Katsushika Hokusai

Besides woodblock prints, other mediums included paintings on silk, such as the one below, which has quite vivid colors not captured well in this scan. (Photography was forbidden at the exhibit, so I had to raid the internet.) There were also several paper scrolls and even large folding screen, such as you might change your clothes behind.

(Painting on silk, one out of four similar kakemonos from a series named “Pleasure Competition in the Four Seasons.” This is Summer.)

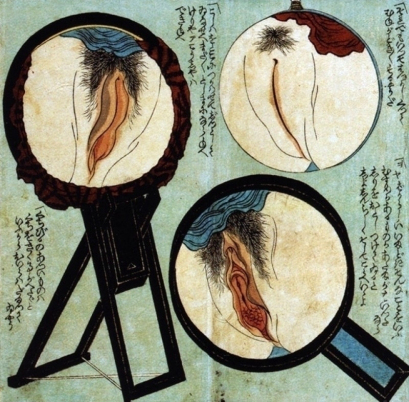

Most of the works were simple heterosexual couplings like this, but on display were depictions of homosexuality (mostly lesbianism, probably to titillate men), threesomes, 69, cunnilingus, dildos (including strap-ons), money shots, bestiality (usually to some fantastic or divine purpose — think dreams or animal spirits), even a glory hole!

above: Kitagawa Utamaro (喜多川 歌麿; c. 1753 –1806)

below: This was not on display, but I couldn’t find the picture of the big black strap-on that was there.

above: Ehon haikai yobuko-dori 会本拝開夜婦子取 (Haikai Book of the Cuckoo (or Worshipping a Woman’s Pussy at Night))

below: attributed to Tsukioka Settei (月岡雪鼎; 1710 – 1786)

And as always happens with sex, there was satire. (No, the Hollywood porn industry didn’t invent the sex-parody.) This picture from the British Museum’s collection is a riff on the parinirvana of the Buddha — his death, many years after achieving Enlightenment — and so depicting it this way is analogous to nailing a penis to a cross, although this is more lighthearted than that would have been.

My buddy bought the book to the exhibit, which is massive and includes a great many more works than were on display. (It was $40 and I’m a poor writer.) But I did get a T-shirt. :)

But despite all the shame and hoopla, there are signs that Japanese attitudes to shunga might be changing. Weeks after it opened, there are still long lines to see the exhibit. We had to wait thirty minutes to get in, even late on a Sunday. And although there were quite a few foreigners, the crowd was overwhelmingly Japanese.

September 18, 2015

Science is a Myth

When I was an undergraduate, I took a political science class called “Ideas and Ideologies” that had a significant impact on me, and still does to this day.

I was interested in politics then, much more so than I am now, so I was fascinated to see the raw material laid out in a huge schematic, a kind of circuit diagram connecting the mechanisms of liberalism, conservatism, socialism, fascism, feminism, environmentalism, anarchism, and their derivates like libertarianism, communism, and fundamentalism.

It was an upper division honors colloquium and so not an easy class. There was an English-crap-tonne of reading, for example, including works with some really obtuse language like Hobbes’ Leviathan (1651) and Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), the founding document of conservatism.

And it was all very serious. There was no classroom. We sat in high-backed chairs around a long table inside the conference room of the Carl Albert Congressional Research Center.

There were no lectures. We were expected to have done the reading and to show up prepared for 90 minutes of moderated discussion. (Our professor did an excellent job of masking his own beliefs. By the end of the term, we still had no idea.)

There were no tests. Our grade came entirely from our contributions in class and a series of papers, including a big fat one at the end.

One of the assignments was pure genius, so much so that I used it with my own students during my very brief teaching career. (It was a temporary second job the year after I quit med school. So after I was done at the office, I lectured, or led a lab, and spent my weekends grading and preparing next week’s material. It was not fun.)

It was a “news tasting”, a cross-sectional analysis similar to how vintners will successively taste multiple wines of the same varietal in the same crop-year so as to appreciate subtle (or not-so-subtle) differences. Here, we had to pick a current event and report on the coverage of that event using at least five different sources — although we were all overachievers in that class — including a minimum of two in each medium, broadcast and print.

It was eye-opening. Some of the differences were obvious of course. NBC didn’t have a very strong political bias but they were very sensationalistic. They used language that subtly increased tension, at least compared to other sources I studied, and would occasionally fail to mention a highly likely outcome in order to extend the “drama” and get you to tune in one more night.

But simply watching back-to-back news coverage is easy. The real value of the exercise came from the paper we had to write, from thinking. It’s often been said the best way to learn is to teach, which is true. Real insight comes when you have to explain what you think you know, which is often far less well than you thought.

Writing the paper and defending it in class required us to apply what we had learned about the various ideologies to craft a “meta-level” theoretical framework.

It tuns out I was in the middle of my History of Science education at the time — the following year I did my senior thesis in the field — and as I peeled back the news to reveal the ideology, I realized you could keep peeling. To the scientism underneath.

Scientism is the belief in the universal applicability of the scientific method and that the human-constructed edifice of science constitutes the most authoritative worldview, or simply the most valuable part of human learning, to the exclusion of other viewpoints.

Most people stiffen a little at that definition. I think to them it implies that relativism is true, or weakly that science is just another point of view the same as any other superstition. But that definition is actually a scientific one. It presumes no answer, even that there’s anything special about science.

Most people are not scientists, yet scientism — the belief that science is the best or only path — is the unifying factor of every modern ideology. Even Christian fundamentalist thought-leaders will tell you there are coldly rational reasons for what they believe, same as any liberal or conservative.

The point is not whether that’s true. There will always be squabbles over orthodoxy, over who practices the One True Faith and who should die a heretic. The point is, when John Locke set out to justify the English revolution, and so founded liberalism, the first modern ideology, he did so with tools that had already become popular with the educated elite (far less so with regular folks) and on the belief that the rational reorganization of the world would lead to human happiness.

I’ve said before that liberalism orients its Golden Age in the future, whereas Conservatism puts it in the past. Both alienate you from your authentic present.

It is a point wonderfully made in C.S. Lewis’s The Discarded Image, his final printed lecture series in which he describes the medieval world view, the one we threw away. He is up-front that he preferred the old way and that, as he said, his Faith makes sense of his Reason and not the other way around.

Almost no one believes that anymore. And in that regard, scientism is the religion of our era, our founding myth, for even fundamentalists put the need for rational proof ahead of God.

One of the reasons Eastern religions, and Buddism in particular, have appealed to so many late modern Westerners is because they never succumbed to scientism. Not truly. Not finally. And where Hinduism and Shinto and the traditional Chinese melange are inexorably bound to their parent cultures, Buddhism preaches an ecumenical path. In fact, of all the religions of man, only Christianity and Islam have been proselytized more.

I’m not suggesting science is wrong, just that scientism is. Science is wonderful, but like any human creation, it has its flaws. More importantly, it has its limits, distant though they be.

It is often supposed that science and religion are at odds in our time, and that in fighting the fundamentalisms of the world, what we need is “MOAR SCIENCE!” It is the battle cry of scientism, of an orthodoxy fighting a heretical sect of the same religion.

But consider this. “Controversial” theories like evolution are already well-established, and if any collection of scientific facts were going to sway some people, it would have happened already. I predict throwing MOAR SCIENCE! at it isn’t going to change a god-damned thing.

What we need is more humanity. And that is something different.

(Picture: Kryžių kalnas, or Hill of Crosses, Lithuania)