Rick Wayne's Blog, page 2

May 24, 2021

(Fiction) Remnants

The area affected by the anomaly was too large to cordon completely, but warning signs had been hammered into the ground at regular intervals, and a barbed-wire fence surrounded the most dangerous areas, including the main compound, where several temporary structures had been erected in the remains of the abandoned neighborhood, including an enormous white-walled hangar. Quinn and Clo flashed their IDs at the gate and signed a digital logbook before being given brief instructions: protective gear was required at all times, they had to be out of the cordon by dark, all liability was theirs, etc. They were each handed a thick plastic packet, inside of which was a thin white hazmat suit, including soft head covering. They explained they had their own, but the guards insisted sternly that visitors were only allowed to wear EPA-approved protective gear. After rolling their eyes at each other, they parked near a large dump truck and slipped the thin suits over their much more robust SCA uniforms.

The land had been razed as far as either of them could see. The anomaly was radioactive, which meant the material it deposited was as well, albeit less so, and every inch of earth to a depth of six inches had to be dug up and carted off by train to the Nevada desert. Trees, grass, homes, absolutely everything inside the anomaly had been pulled down by the EPA, whose backhoes were still hard at work in the distance. There was nothing left. It was apocalyptic.

“What a mess,” Clo said through her head covering, which muffled her voice.

After several moments of bleak silence, a noticeably short man in a much fancier orange suit and black galoshes walked over to greet them. Ezra followed.

“I’m Nelson,” he said through some kind of suit-mounted speaker. “Gary Nelson. I’m the site director here for the EPA.”

“Nice to meet you, Gary.” Quinn took his hand. “I hear you got a body for us.”

“Yes. Well, there’s that, too. We didn’t touch it, as ordered. We kept it in the temporary structure there.” He pointed to the enormous tarp-walled hangar, but he was already walking in a different direction.

Quinn noticed that Ezra had wrangled one of the nicer suits, whereas his own made it difficult to see. The flexible plastic of the visor had been folded inside the case, and the crease cut right through Quinn’s line of vision. The hood was also poorly ventilated, and Quinn felt like he needed to shout over the sound of his own breathing.

“Is it still very radioactive?” he asked.

“Only where we’re working. But chronic exposure even to low levels can cause all kinds of long-term problems. Best to be careful.”

“You said ‘that too.’” Clo also raised her voice to be heard. “Was there something else?”

“Yeah, I’ve been briefing your colleague here.” He motioned to Ezra. “The house and body can be preserved. We could even move them if you needed us to. It’s the other one that’s the problem. We weren’t sure what you wanted us to do with it.”

“Other one? You mean another body?”

“No.” Gary shook his head.

“You just have to see it,” Ezra said ominously.

“It’s down in grid six. We can ride in this.”

Gary motioned to a small covered ATV, one in a row, all marked with the EPA logo. It was a tight fit that required Ezra’s feet to hang off the back, but they got everyone inside, and as the tires rolled over bare, crumbly earth, Quinn watched men and equipment slowly working in small, distant teams. One group was spraying liquid from tanks on their backs which gathered into a rolling red stream, almost like flowing lava. The ATV drove through it.

“Helluva operation you got here, Gar.”

“It’s not toxic,” he said. “It helps absorb radiation and also nitrogenates the soil. Best thing for this place is to get the plant cover back as soon as possible. Is it true what they say? About what happened here?”

“I dunno. What do they say?”

“That you guys disabled the anomaly with a cryogenic bomb.”

Quinn nodded once. “Something like that.”

“You know, I have a degree in chemistry. Lots of experience cleaning up dangerous compounds.”

“Oh yeah?”

“It’s just. I heard you guys were hiring. So, maybe . . . You know.”

Quinn gave Clo a look.

“You wanna be a Crimes Division officer, Gar?”

“You guys got all the cool stuff. I heard Arkane made you pulse rifles.”

“What’s a pulse rifle?” Clo asked.

“You don’t know?” Gary turned. He seemed shocked.

“If we did,” Quinn told him, “we couldn’t say, now could we? Something like that would have to be kept secret.”

“Of course.” Gary made a zipping motion over his visor near his lips. “So, how about it?”

“Well, unfortunately, all that stuff has to go through the director. But if you wanted to submit a resume, I’m sure he’d take a look.”

“I did. I wondered if maybe you guys could put in a good word.”

“That we will, Gar. That we will.”

After a short, bumpy ride, the ATV stopped at a small rise.

“This is it.”

Clo stood slowly, eyes glued to the object in the wide, shallow depression below.

“Whoa . . .”

“That’s what I said,” Ezra told her.

An enormous metal sphere rested still in the dirt.

Gary got out and walked toward it. “We’ve been dousing it with liquid nitrogen every ten minutes,” he said. “We’re not sure if that’s doing anything, but since cold worked on the big one, we thought it was better to be safe.”

A man in a white hazmat suit sat in a lawn chair near the sphere reading a book. Next to him was a liquid nitrogen dispersal backpack, complete with tank and heavy-nozzled sprayer.

While the others stood staring, Quinn approached the dull sphere. It was almost twice as tall as him and perfectly smooth. He reached out a gloved hand to touch it, but stopped a few inches away. He could see his own dark, blurry reflection. It was warped and twisted even though the surface didn’t appear to be.

“It’s okay,” Gary explained, running his hand across the surface. “It’s completely inert.” He knocked on it, but there was no sound. “Seems to be solid.”

“Where did it come from?”

“Well, according to FEMA, it wasn’t here originally, which meant it must’ve formed after you guys knocked that thing out.”

“Like a spore,” Ezra said.

Clo took a step back. “You mean it could make another one of those things?”

“It’s just a guess,” Ezra added quickly. “But single-celled organisms often form spores when environmental conditions become too hostile for growth. Spores found on the exterior of the International Space Station survived in a vacuum, constantly bombarded by cosmic rays, for decades. Spores have survived inside Antarctic ice cores for tens of thousands of years, only to be successfully revived.”

“That sounds like it should be illegal,” she drolled.

“It is,” Quinn said. “The court ruled the Species Resurrection Act applies broadly to microbes.”

“Well, that’s good to know.”

“And you’re sure it hasn’t grown?” Quinn asked Gary.

“Yup,” he said. “Hasn’t changed at all. It’s 3.47 meters in diameter, exactly the same as when we found it. We’re trying to keep it below -30 centigrade. That seems to be doing the trick.”

“Well . . .” Quinn sighed. “Someone’s gonna have to take this to the containment facility. And find a way to keep it cold on the way.”

Everyone slowly turned to Ezra, who blushed.

“Let’s clear the house first,” Quinn said, “so Gary and his team can finish their work.”

“We’d appreciate that.”

“Then, Ez, you’re gonna have to take the point on this.”

“Why me?” he pouted.

“Well. Because you don’t have any homicide experience.”

He sighed disappointedly.

“Next time,” Quinn consoled him.

They all looked at the sphere one more time before riding back to the main compound. As they approached, Quinn saw Sheriff Landry waiting by the main gate. She was in her regular jacket and uniform. The guards clearly didn’t like her lack of protective gear, but she apparently agreed not to move from the gate, so they tolerated her insubordination.

“Can’t stay away, can you?” she called as Quinn walked over.

“Sheriff,” he said, taking off his helmet. They shook hands. “Good to see you. How’s Delmer?”

“Oh, he’s sittin’ in jail.”

“I thought you agreed to tear up all his warrants.”

“The old ones, sure. I didn’t say anything about anything new. He assaulted one of those army guys.”

“The one who tased him?”

She nodded. “He knows damned well he can’t go around punching people in the face. Even if they deserve it.” She held up a packet of documents paperclipped to a manila envelope.

“Ah. You got it.”

“You wanna tell me what it means?”

“I sent it early because I thought you might want your lawyers to take a look at it.”

“I’d rather hear it from you.”

“Fair enough. That document says that due to a lack of resources and subject matter expertise, you officially request the investigation into the origin of these events be led by the Crimes Division of the Science Control Agency, US Department of Education.”

Sheriff Landry smiled wryly. She knew there was some hidden significance to the transaction he was proposing, but she also knew that, whatever it was, Quinn was deliberately protecting her from it, so she let him talk, and when he was done with his spiel, she signed the packet in three places without fanfare.

“There.” She handed it back. “We good?”

“We are excellent,” Quinn said, extending his hand again.

The sheriff took it. “I know you got all this nonsense goin’ on, but if you can, you should stick around for some pie.”

“Pie?”

She motioned down the road. “Town’s having a little do. You know, to celebrate not being wiped off the map’n all. I can think of a few folks that’d like to shake your hand.”

“Well, if it’s not too late when we’re done, we’ll stop by. Or I will. I can’t speak for the others.”

“Can’t say I’d blame them if they skipped out. I’m not much for these things either. But you know how it goes. Got an election coming up.”

She winked and walked back toward her patrol car.

“What’s that all about?” Clo asked from several paces back.

“Just a joke. She’s a shoo-in for reelection.”

“I meant that,” she said, pointing at the packet in Quinn’s hand.

“Oh.” He held it up. “Nothing exists to the director that isn’t on a piece of paper. So, here’s paper.”

Clo unlocked the rental car so Quinn could put it inside. “And what’s he gonna do when he sees that?”

“Hopefully, not have an arrhythmia,” he joked.

Clo scowled. “Something going on I need to know about?”

“Nope. Just typical agency bullshit.”

She thought for a moment. “He told you not to investigate it.”

“Not exactly.”

“I don’t get it. Isn’t this exactly the kind of thing we’re supposed to investigate?”

“To be fair, I think the director sees this whole episode as a failure.” He motioned to the decimated landscape. “He wants us to focus on threat reports because he thinks that’s our best chance of getting ahead of this kinda stuff, of stopping it before it happens rather than after.”

“Bad guys aren’t gonna apply for a science license.”

“Yeah, well, try telling him that.”

As the pair headed toward the enormous white hangar, Clo nodded back toward the car. “Are a couple signatures gonna be enough to convince him?”

“Dunno. I’m having a hard time reading the man.”

“Might that be because he’s wasting away in a hospital bed?”

“Maybe. Part of me says he’s got some sort of plan, that he wants FEMA to issue their incident report absent a cause so he can use the omission as an excuse to wrangle for a bigger budget or something. Or, maybe we’re the pointy end of a cover up.”

“A cover up?” Clo scowled. “For who?”

“No idea. Then again, part of me also thinks he’s just a career bureaucrat who can’t see beyond his own nose, and if the incident report comes out absent any progress on the investigation and people start demanding answers, he’ll just throw one of us under the bus and introduce a bunch of reactionary policies. Either way, I’m trying to head him off at the pass.”

Clo shook her head as they went through a decontamination tunnel. Signs instructed them to raise their arms as jets of treated air hit their bodies.

“You’d think that after something crazy like this they’d back off a bit and let us do our jobs.”

“Yeah, well, no matter where you are, management always thinks we exist to support them rather than the reverse.”

The giant white hangar had no floor. Under their feet was the same bare dirt as outside. Resting on it at even intervals were all the things salvaged from the chaos, including everything inorganic, which was mostly trash, arranged by size, along with several of the strange spires Quinn had seen from the air. Multiple trees that had been wholly replicated by the anomaly stood in a cluster like a charcoal sculpture of a forest. At the back of the enormous space was the boarded, derelict house, which stood alone against the white wall of the hangar.

“That’s not at all creepy,” Clo said.

Ezra had prepared their equipment on a folding-leg table in what would’ve been the home’s front yard.

“Everything’s working,” he said as the others approached. The spherical drone hovered in the air behind him.

“Coms check,” Quinn said.

“Loud and clear,” Thalia replied from her desk at Section 08.

“Drone’s on camera duty,” he told her. “Record everything.”

“10-4.”

“Ez, you’re handling equipment and taking samples.”

“Got it.”

“I don’t have to tell you all what almost happened here, how close this was to a tragedy. A unknown technology darn near swallowed an entire town.” Quinn paused to let that sink in. “Someone is responsible for that. Several families lost everything. Three people are confirmed dead. Two seem to be accidental, according to our friends at FEMA. The third”—Quinn pointed to the house—“is certainly not. Based on the state of the body, we’re proceeding as if this was a murder. However, we should not immediately assume it’s related to the anomaly. It could be this guy was just in the wrong place at the wrong time. The kids Ez and I spoke to said he’d been hanging around the place for a couple months. Maybe it was just bad timing. Or, someone might’ve saw the anomaly as an opportunity to rid themselves of a body. Or, neither of those. That means for today, our job is two-fold. We have two separate lines of evidence we’re tracking. We need to discover the identity of this man and what happened to him, and we need identify the cause of the anomaly and how it got loose, taking this house as the point of origin. For that reason, as we go through it, I want Clo and Kripke to focus on the anomaly. Thalia and I will focus on the murder. When we’re done, we’ll switch up and go back through the whole thing again to make sure we didn’t miss anything. Make sense?”

Everyone nodded.

“All right. Let’s get to work.”

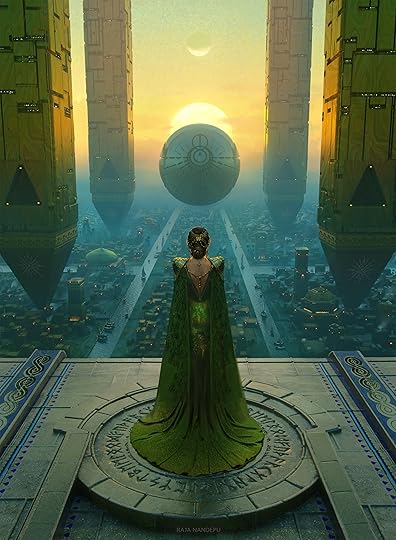

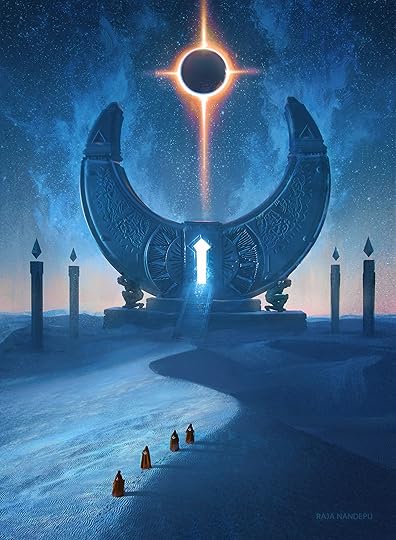

Rough cut from the second installment of the Science Crimes Division series, tentatively called ANACHRON. (They do not have to be read in order.)

The first, THE ZERO SIGNAL, goes on sale Wednesday!

cover image by Edward Burtynsky

May 23, 2021

(Sunday Thought) The Hard Thing

Dear aspiring novelist,

Thank you for your letter. I don’t wish to offend. But I’ve been asked that question before, and I’ve learned something like the following is the best advice I can give. It may or may not be good advice.

No one is born knowing how to write a novel. Some spring writers succumb to the idea that if they just work hard enough — and want it bad enough — they can create something compellingly good their first time at bat. Probably not. (Imagine a surgeon believing that.) Probably we’ll need to practice, where practice doesn’t mean writing and rewriting paragraphs and chapters. A surgeon isn’t a surgeon because she’s really good at cutting, and we’re not chapterists. We’re novelists. That means we’re probably going to have to write a few novels before we’re any good. (An author’s first published novel is rarely their first novel written.) There are exceptions, but probably you’re not one. I wasn’t either.

That’s not to be discouraging. I encourage everyone to write a book. I even convinced my 70-year-old father, who blames me entirely for the cowboy trilogy he’s almost finished. I think there’s value in writing, as there is in learning a musical instrument or foreign language, even where you don’t intend to become a musician or interpreter. But there’s a difference between learning the guitar for personal growth and playing it professionally, where you expect people will pay you for the pleasure of listening, just as there is a difference between running a marathon for the challenge and competing to win. I doubt very many pro runners win their first marathon. I expect they have to lose a few first.

There’s something about writing a novel that makes people think it’s not like those other things, that it’s something they can sufficiently master the first time out, whereas you hardly hear anyone say they want to compose a symphony, just one, and have it played by the Royal Philharmonic.

I am not surprised you are struggling. The bad news is, it’s not immediately going to get easier. The good news is, the struggle is where you learn.

Definitely don’t write anything you’re not excited to write. Our words are our babies. If you’re not excited about yours, no one else will be by a long shot. Readers are not forgiving. And they can smell a cheat. It’s hard enough to convince them to give you a chance. You don’t get a second. And remember, if you’re going to do it professionally, you’re not going for the sale. The few dollars or whatever you make isn’t even going to buy you a coffee. You’re going for the recommendation, and you’re not going to get it if you know or even suspect a big chunk of your book is a slog. That’s point number one.

Point number two you already mentioned: editing. There is no version of this book that won’t require major rewrites before it’s worth reading. Accept that in your bones, and accept that you can’t get to the second draft until the first is done. So, finish it.

That might seem to contradict the first bit about not forcing it. Here, there’s some advice from one of the big name fantasy authors (I forget who) that applies. It’s simple: Get there. Are your characters planning a heist? Get there. As soon as they decide on the idea, cut to it in the next chapter and let the reader figure out the plan as it unfolds — and then goes horribly wrong. You as the author need to know what the characters did in the intervening time, but the reader doesn’t. Get there.

I don’t know what that means specifically for your work in progress. It seems to me a journey of some distance through a ravaged land gives ample space to explore, by adventure, the world you’ve created, but if you’re not excited about the opportunity, get there. You have to write the story that comes out, not the one you wished had come out. And keep in mind that just because you have a novel-sized space doesn’t mean any idea will fill it. I’m not saying that’s the problem. I genuinely don’t know. But there’s nothing that necessitates every idea for a novel actually is a novel. Some of the worst novels I’ve read probably would’ve made excellent short stories. (I think Jorge Luis Borges was one of the greatest writers of all time, and he never wrote a single novel. It was all shorts.)

What you absolutely should not do is write filler to, say, turn a novella into a novel. (I started out writing novellas, which became The Minus Faction.) Instead, get there, even if the story seems awkward as a result. Finish the damned draft. Get it down using only the parts that excite you and then see what you have. Often, the mere act of writing spurs more, but if you get to the end and find your story is not a novel and you think it should be, then address that in the second draft, along with whatever else needs addressing. It’s your first time, so you may need four or more major rewrites, where you cut and delete large chunks, perhaps even the majority of the manuscript, before you can’t make the story any better. Don’t get discouraged by that. We learn by doing, so regardless of the outcome, your second novel will definitely be easier. People may even pay you for it.

Sincerely,

me

May 22, 2021

(Fiction) The Attic

Quinn was waiting in the hotel lobby when Nio stepped from the elevator in her high-collared coat. It was crowded on the main floor. People milled or sat idly in chairs. Several had their laptops open and were working at impromptu offices.

“What happened?” Nio asked. “A tour bus break down?”

“Apparently one of the subway lines is down.”

“Seriously?”

Elegant flat screens were affixed to each side of the marble-lined square column near the front. As each visitor passed, their phones and biometrics were read and a custom advertisement was displayed. Nio got birth control.

“I hate being in the city.” She made a beeline for the coffee stand, which had a short line. “Why couldn’t we stay somewhere else?”

Quinn followed. “Not feeling any better, I see.”

“Meaning?”

“Nothing. It’s just you were in a bit of a mood when we got in last night.”

“This shackle is a pain.” She knelt to scratch under it, but the device was too tight.

“You’re lucky you don’t have one of the old ones. They weren’t waterproof. You would’ve had to put your foot in a plastic bag and close it with a rubber band.”

“How long is this meeting supposed to take?”

“With Erving? Probably not long. He’s a busy man. But we’re also set to coordinate with Agents Willis and Cortines, who originally investigated the case. We were supposed to have a teleconference with them a couple days ago in—”

“In Minneapolis. Yes, you’ve mentioned Minneapolis. Several times.”

“Okay.”

Nio ordered a coffee and donut from the teenager behind the counter and stepped to the side.

“Nothing for me,” Quinn said with a smile. He watched Nio eat the donut in three large bites. “You wanna tell me what’s wrong?” he asked.

“Nothing,” she said with her mouth full.

“Nothing… Okay. For the record, the only woman who gets to play the Guessing Game with me is my wife.”

“Whatever.”

The barista leaned over the counter. “Here’s your coffee.”

Nio left the lid on the counter and walked out the front, blowing on the hot liquid. The sliding doors parted for her and a man walked past wearing bright red shoes. Nio turned to look just as gunshot broke and the glass of the door shattered. She ducked and spilled her coffee over the sidewalk as screams erupted all around.

“STAY DOWN!” Quinn pulled his sidearm and ran in a crouch toward the sound of the shot.

Half the traffic in the immediate vicinity screeched to a halt. Several drivers left their car doors open and joined pedestrians hiding behind poles and mailboxes. Self-driving vehicles, intent on their destination and oblivious to anything but the roadblocks now in their path, either weaved through the chaos or turned to find an alternate route. Several were apparently sophisticated enough to realize there was some kind of danger to their passengers and tried to escape by accelerating. There was a collision almost directly in front of Agent Quinn, who leapt over it easily with prosthetic feet and ran incredibly fast toward the sole open window on the fourth floor of a building down the street.

“Miss, are you okay?” the concierge asked Nio, helping her off the ground. “We should get inside,” he said urgently.

Nio faced the shattered door, looking for the man in red shoes.

“There was no bullet,” she said.

“What?”

With no reflection to warn her, she didn’t see the revving silver sedan until it was nearly on her. She pushed the concierge and dove into a brick-lined garden display. The car smashed up over the little wall, nearly crushing her, before impacting the frame of the door. Glass fell.

And then it stopped. A tire spun over her head. She could smell the rubber.

The silence of confusion was broken only by the screaming of a child in the back seat of the sedan.

A child!

Nio crawled out from under the angled vehicle just in time to see the driver, a middle-aged woman in a flower-print blouse and glasses, drop to the brick sidewalk. Her eyes were wild as she fell on top of Nio.

“What’s the matter, Ms. Tesla?” she said. “Don’t you want to play with me?” Her eyes burned.

Nio knew she wasn’t supposed to believe the driver was Amok. She was supposed to believe he was controlling the woman somehow.

“There’s no such thing as mind control,” she accused.

And yet, the woman’s bioelectrics were all wrong. Despite her panicked outward appearance, despite the screaming child in the back of the car, the woman on top of Nio had no frenzied cycling. Her pattern signaled concentration. Intent.

Quinn leapt over the car and pulled her off. He raised a heavy fist and but stopped as if just realizing she was female.

“Wait!” she called, holding up her hands. “Please! He was going to hurt us!”

“Who?”

“The voice on the radio. We were driving to Samuel’s daycare. I was getting caught up on email when the car announced it was recalculating the route. I couldn’t take control. There was a voice, a deep voice on the radio. It gave me very precise instructions, but I can’t do it. I just can’t. Please, please help my son!”

Nio darted to the car and removed the toddler, who was barely old enough to walk and wailing at the top of his lungs.

“What were you supposed to do?” Quinn asked.

She handed the child to the terrified woman, who was still on the ground. Her embrace did nothing to calm her son. In fact, the boy was squirming to get away from her.

“I was supposed to act like he had taken over my mind. I was supposed to tell you things. He said as long as I—I wasn’t violent, that you’d—”

“What were you supposed to say?” Nio interrupted.

The woman looked between them. He settled on Quinn. “You must be Agent Quinn. I was supposed to tell you that your wife’s hydrangeas are coming in nicely.”

Quinn and Nio turned to each other.

“Khora…” he breathed. He replaced his weapon and went for his phone.

Sirens were already approaching.

“Am I in trouble?” the woman on the ground asked. “I didn’t want to do it! I was just protecting—”

“Stay there,” Nio said.

“Honey!” Quinn said to the phone. “Are you okay? Is everything okay?” A pause. “Where’s Gregory?” Pause. “Please check on him. Yes, right now.” Pause. “No, it’s fine. Everything’s fine. Just please go check.” He covered the microphone and turned to Nio. “I need to get the Bureau over there.”

“Don’t let your people go in,” she said.

“What if he did something—”

“Your family’s been there and nothing has happened! The FBI barging in might be the trigger. Have them leave, calmly. Tell them not to get into the car, just walk calmly down the street.”

“There’s a small park a couple blocks away.”

“That’s good. Have them go for a nice early morning walk. Your people can pick them up at the park. Just get them out of—”

“Right,” Quinn said to his wife. “That’s great. Honey, listen to me. I need you to take Greg and go for a little walk. Don’t get your coat. Don’t get anything. Don’t lock the door, just go. Right now. Take him and walk calmly to the park down the street. No, it’s fine. It’s just a precaution. Just take Greg and go. Don’t argue with me, please!” A moment later, he lowered the phone. “Okay, they’re going.”

He took out his ID and held it high for the approaching police officers. Then he replaced the phone to his ear.

“Honey, listen to me. Just go to the park. I’ll call you right back. No, no. I just need to make sure everybody’s on their way. Okay? I’ll call you right back.”

Quinn asked the cops to get a statement from the woman on the ground, who was clinging to her son and trying to calm him as the boy repeatedly flailed and went limp.

“And search that building!” He pointed. “We may have a shooter.”

A third patrol car arrived and Quinn stepped to it.

“I need to get to Federal Plaza!”

After a very short call with Special Agent Erving in the car, who felt certain the shot was a diversion to leave Nio exposed, Quinn was back on the phone with his wife, who had almost reached the little park around the corner from their house.

“You’re doing great, hon. They’re almost there.”

A crowd had already gathered by the time Nio and Quinn reached the command room on the fifth floor of the federal building. Men and women sat around a table and stood at the walls looking at a bank of flat screens. The large one at the center was flanked by several smaller screens on both sides. The smaller displays fed video from several armed agents’ bodycams, and Agent Quinn’s white-picket house was visible from several odd angles. It was an older neighborhood, and the lots were close together. Neighbors standing on their porches were asked to go back inside.

“There goes our invite to the neighborhood BBQ,” Quinn joked under his breath.

“Signal jamming in place,” one of the technicians at the table said. “ULFR is up.”

“Show me the inside,” Erving said. “I assume we have your permission, Agent Quinn.”

Immediately, the central image of the house was replaced by a 3D, grayscale overlay which revealed the entire interior as if by ultrasound or sonar. It was glitchy in spots, but as it moved forward, penetrating the house, everything was revealed: the wiring in the walls, the nails in the boards, the contents of cabinets and boxes. Everything. The computer highlighted potentially suspicious objects in different colors, but after several minutes of back-and-forth scanning, there didn’t appear to be anything of immediate note.

“Did you check the attic?” Nio asked.

“Roger that,” Erving said next to her. Then into the radio: “Check the attic.”

The rendered display moved up.

“What the hell is that?” someone said.

There was a cluster of wires and equipment, along with what appeared to be animal bones, in the middle of the attic. But with each piece overlaid on top of the other on the screen, it made no sense to anyone.

“We need to get up there,” Erving said.

“We’re ready to cut the power,” someone reported.

“Cut the power,” came the order over the radio.

Lights inside the house went off, but nothing else happened. It was a bright morning and the house was still well lit.

“Wait two minutes,” Erving said. He turned to Nio. “We wait in case there’s an explosive on a dead-switch timer.”

“Timer could be longer,” she said, unimpressed.

“That’s why we use drones,” he replied flatly.

The central feed switched to a drone camera as it slowly approached the front door of the house. A pair of armored officers crouched on either side of the front door, ready to open it.

“Begin your reconnoiter,” Erving said as the counter on the screen wound down.

The door opened and the drone moved forward. The living room was neither neat nor messy. It was lived in. Most objects appeared to be in their place, but there were colorful toys on the floor and a few dishes on the counter that separated the small living room from the kitchen. Beyond was the door to the backyard.

“I’m reading several independent power signals,” the drone pilot said over the radio.

“That’ll be anything with a battery,” a man in the corner explained quietly to someone else.

“First is in the kitchen,” said the pilot.

The drone was sophisticated and the image didn’t wobble as it flew over the couch and into the kitchen.

“That’s my kid’s RC car,” Agent Quinn said into the radio. “Both it and the remote have batteries.” He turned to Nio with a question on his face.

“Unlikely,” she said. “But have them take it out just in case.”

“Flag the car for removal,” Erving said, “and continue your reconnoiter.”

“Roger that.”

“Three more signals,” the pilot said.

“What are we looking for?” Special Agent Erving asked Nio.

She shook her head. “Could be anything. Literally.”

“Second signal located.”

“That’s my wife’s tablet,” Quinn said. He was doing his best to stay calm, but the video feed from a surveillance drone flying through his house was obviously disconcerting.

“Third signal upstairs.”

The drone hovered upward through the gap in the ceiling over the stairs. It moved down a short hall and into a bathroom.

“That’s my sonic toothbrush.”

“Last signal is in the attic.”

“The stairs to the attic are spring loaded,” Quinn told Special Agent Erving. “That drone isn’t going to get them open. Even I have to give it a good tug.”

“Copy that,” came a voice from the radio. “Are we authorized to enter the dwelling?”

“Yes!” Quinn said.

“Yes,” Erving repeated into the radio. “Remove the flagged items one at a time before proceeding to the attic.”

“Roger that.”

Everyone in the command room waited while the armed and armored officers entered the house single-file, weapons raised, and completed their tasks with methodical precision. Several minutes later, the hinges to the stairs squealed as a pair of officers pulled them down. The others were kneeling with their rifles pointed toward the roof. The drone rose straight up into the attic, which was dimly lit by a round gap at one end.

“Jesus,” the pilot on the radio exclaimed. “What the hell is that?”

An old CRT monitor had been suspended by LPT1 cables from the rafters, along with a handful of other pieces of archaic equipment, all at different heights. Some of it had been “skinned”—casings removed to expose the circuitry underneath. The monitor had been smashed. Inside sat a doll. A wide-beaked bird’s skull had been affixed to the doll’s naked body in place of its head. One of its arms was a modified game controller. On the floor underneath was a pentagram, apparently hand-drawn in blood. A white cord ran from the base of the monitor to the rectum of the dead white mouse in the middle of the pentagram, as if it was a bio-occult Ouja board. Cords also ran from the monitor to various other objects placed in a circle around the pentagram, as well as to bloodied animal organs further out at each of the five points.

There were two electrical signals. The first came from a vintage Nintendo Gameboy, covered in black paint except for a circle at the center of the screen, which repeated a scrolling message. The second came from the early-2000s JBL Pro computer speakers that flanked the mouse.

“I’m picking up hypersonic sounds from the speakers,” the technician said.

“Ask him to lower the pitch,” Nio said softly.

“Working on it,” the man said.

Everyone heard typing.

“What’s it say on the screen?” Erving asked.

“It’s a Gothic poem,” Nio answered.

“A poem?” Erving scowled as if he’d never heard of such a thing.

“The Gashlycrumb Tinies.”

Agent Quinn read some of the lines as they scrolled upward in monochrome pixels, like reverse Tetris. “C is for Che who wasted away. D is for Di thrown out of the sleigh. E is for Ed who choked on a peach. F is for Flow, sucked dry by a leech.”

“What does it mean?” someone asked.

“He’s changed the names,” Nio said. “Those are my siblings.”

“M is for Max who was swept out to sea,” Quinn read. “N is for Nio who died of ennui.”

“I have the sound,” the technician said.

“Play it,” Erving ordered.

There was a burst of static. “Murder,” a man’s voice said calmly as if announcing the day’s weather. “Murder,” he repeated a moment later. “Murder… A pleasant murder. Today you will murder.”

“Is it a transmission?” someone asked.

“Transmissions are jammed,” someone else reminded him.

“Looks to be on a 20-second loop,” the pilot said.

Agent Quinn turned to Nio. “That was being broadcast in my house? What is it, like subliminal messages or something?”

“That’s what we’re supposed to think,” she whispered.

“Do you have something to say, Ms. Tesla?” Special Agent Erving asked.

“It’s nothing. An unfinished thought.”

“We need a plan of action, people.”

“Bag it,” someone suggested. “It’s a crime, no matter how you slice it.”

“Clearly,” Erving said sarcastically. “But do we have any evidence of a threat?”

“Chem sniffer is negative for explosives,” the pilot said through the radio.

“Then get a HazMat crew in there. Don’t let anybody touch any of that stuff directly. Might be boobytrapped.”

“That’ll take time,” a man on the radio complained.

“Is it the time you’re worried about or the money?” Erving asked.

“Well, honestly sir, both.”

“I’ll get you the money. I’ll ignore the rest. Get busy.”

“Yes, sir.”

Erving took of his headset and someone switched on the lights. Chatter rose to a small din. Agent Quinn already had his phone and was dialing.

Nio leaned in. “Can I talk to you a second?”

“I need to call my wife.”

“Just a second.”

Quinn nodded, and Nio led them out the door around the corner and down the hall.

“Where are we going?”

“Just gimme a sec.”

When they got to the far staircase, she held out her hand for Quinn’s phone.

“I need to call her,” he objected. “She’s probably freaking out.”

“Please.”

He sighed and handed it over. Nio lifted the case of a potted plant in the corner and put the phone under it. Quinn held up his hands in confusion, but she simply walked through the door and down the concrete stairway three levels to a fire exit that deposited them on the parking garage driveway. There was only a small ledge on which to stand.

“What’s going on?” Quinn held the door half-closed. For security reasons, there was no reentry through the fire door, and after a moment, an alarm droned in one long warning and he had to let it shut.

Nio watched it close. “How did he know we were going to Newark?”

Quinn scowled.

“Okay,” she said, “I got a better question. What happened to the woman who nearly ran me over?”

Quinn shook his head. “Uniforms would’ve taken a statement and sent her to the hospital to get checked out.”

“Can we call them?”

“What? Why?”

Nio wasn’t sure how best to answer.

“You think she was in on it?” Quinn asked incredulously. “With a kid in the back seat?”

“Exactly,” she said. “The kid. It’s what we call an anchor, a single little detail that clinches the story regardless of almost anything else crazy that happens. Notice that kid wasn’t old enough to talk. He can’t tell anyone what happened. And he was near in age to your son, meaning you couldn’t help but empathize.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Fifty bucks says she’s already disappeared from the hospital.”

Quinn was scowling.

“It’s a psyop.”

“A what?”

“A psychological operation, an intelligence maneuver designed to manipulate a target’s emotions or thought process—”

“Oh, come on.” Quinn turned away.

“Think about it! How would Amok know we were going to Newark? We only found out a few hours before we left.”

“You can’t be serious. You think it was faked? Where would somebody get a kid for fuck’s sake? At a rental store?”

“There are ways.”

“Come on.” He started for the front.

Nio grabbed his arm. “Okay, listen. I once walked down a street holding the hand of a three-year-old like she was my own. Some acquaintances of mine paid a woman at a daycare center—who happened to be a high-functioning drug addict—a lot of money to let us borrow the child for a couple hours.”

“Borrow?”

“Children are like fucking magic. If you have one, you’re immediately less suspicious, especially if you’re a woman. It’s like a rule of biology. Strangers will actually go out of their way to protect you.”

Quinn stared. “Are you even fucking serious right now?”

“I know how it sounds! But look at the frickin’ facts! Who knew we were going to Newark?”

Quinn thought. “The Bureau. You think our guy’s an agent?”

“No!” Nio sighed. “But if the Bureau knows, then any agency with legitimate ties to the Bureau could find out—Homeland Security or any of the intelligence services, all of whom have a network of operatives in every major city.”

Quinn was obviously skeptical.

“Look at the house!” Nio yelled. Then she got quiet. “Look at the house.”

“Which house?”

“Your house, doofus. It took him a couple weeks to set things up with Maureen. And the intent was to kill us.”

“To kill you.”

“Exactly. And he didn’t hesitate. He didn’t leave us a fucking occult Rubic’s cube in the attic. Amok would have no compunction skinning your family—”

“Excuse you!”

“I’m serious! All his schemes have been about hurting people. You can’t do that if you scare them off. Now, all of a sudden, he leaves your family unharmed and wants to send us on a scavenger hunt? What’s the point of the technopagan altar, other than to be creepy as fuck? Subliminal messages don’t work. Not like that anyway. The whole thing was designed to be unnerving.”

“It succeeded!”

“Whoever was in your house long enough to set all that up could’ve easily killed your wife and son. I’m sorry to say it. I’m not trying to upset you. But think. Why not? Killing them would be the surest way to hurt you, and through you, me. Instead, he left a million potential clues to his identity buried inside a Satanist’s erector set. I don’t buy it.”

Agent Quinn kept a perpetual scowl on his face.

Nio covered her eyes in frustration. “Okay, look at it from a different angle. Look at the end result of this act. What’s happened because of it? They’ve re-tasked the FBI, who will see this as an attack on one of their own.”

“Because that’s exactly what it is.”

“See! You’re not thinking. Even if you assume our guy somehow knew we were going to Newark the very moment we did, he still would’ve had less than twelve hours to set this all up. And how did he find out where your family lives? You don’t even wear a ring.”

Quinn looked down at his hand.

“You told me you had motion sensors installed in your house. How did he get around them?”

“There are ways.”

“But in one night?” she exclaimed. “An intelligence service, on the other hand, would know your address. They would’ve had access to your file, the one you swear we all have, and they would’ve pulled it the moment you were assigned to me, before you and I even met! Officially,” she corrected. “The plan was we were supposed to go Minneapolis, right? Answer me this: have you had any unplanned service calls lately?”

Quinn’s face went pale.

“What?”

“I called Khora from the hospital. After Sleepy Eye. I asked how everything was. She laughed at the question, but I didn’t want to talk about what happened. I was fur—” He stopped. “It doesn’t matter. I asked her to talk about home. She said the power company showed up to cut the limbs from around the lines again. She was annoyed because they just did that last year. We used to have nice shade in our bedroom in the morning. After they cut the limbs, the sun shines through the window bright and early. We had to get blackout curtains.”

“In other words,” Nio said, “not two days ago, strange dudes in cranes were hanging around your roof with power tools making all kinds of noise, and because they were wearing the right uniforms, no one paid any attention.”

“Fuck.” Quinn turned and walked to the street. He stopped suddenly and turned back. “What the fuck!” He covered his mouth. “How the hell did they—” He stopped.

“Somebody wants us off-task. And I gave them the perfect excuse. A psychopath.”

“We need to tell Erving. We need to find that woman with the car and—”

“Whoa, whoa, whoa. We can’t do anything.”

“What the fuck are you talking about?” Quinn was yelling. “Those assholes were in my house!”

“Keep your voice down! I know that. And if we go following up on the woman in the car, what are they gonna think? We’re not gonna find her anyway. If I’m right, she’s gone and your family was never in any real danger. But if you want to keep it that way, we have to pretend like we fell for it.” She studied his face. “Do you understand?”

“We have to tell Erving.”

“How do you know he wasn’t the one—”

“I don’t know! But what the fuck am I supposed to do? Nothing? I have to tell someone.”

“Right now, you can’t trust anybody.” She paused. “Honestly, not even me.”

“What the f—No. Nononono. Maybe that’s okay for someone who hates people, but I’m not living my life like that. I’m not.”

Quinn stormed out of the garage and down the street toward the front door.

“Where are you going?” Nio followed.

She grabbed him but he pulled free.

“I’m not turning into you,” he said.

Nio followed Quinn back through security screening and up the elevator to the fifth floor.

“This is a mistake,” she told him in the cab. The other passengers turned and looked.

“Where is he?” Agent Quinn asked one of his colleagues in the hall.

“In his office. He was looking for you.”

Nio followed Quinn in silence around the corner to an open reception nook with rear windows overlooking the nearby buildings. Nameplates adorned the doors on both sides. The one marked ERVING opened and the man himself shook the hands of a pair of suits, a man and a woman, both older. They didn’t even glance at Quinn as they passed.

“Sir?”

“Come in Agent Quinn. Shut the door behind you.” He sighed. “I need to apologize. To both of you. For not taking this threat seriously earlier.”

“Who were those people?” Nio asked.

“Lawyers,” he said. “Covering our ass on the mess in Sleepy Eye.”

Quinn looked to Nio, who shook her head as if to talk him out of it.

“Something wrong?” Erving asked.

“Sir, if you have a moment, Ms. Tesla has a theory I think you should hear.”

“Alright.” He turned to Nio, who was obviously reluctant to speak. “Well?”

After a moment, Quinn started speaking in her stead. “Ms. Tesla has reason to—”

“I can explain,” she insisted.

The room was quiet.

“Special Agent Erving, have you ever had any experience with counterintelligence?”

“Some. Why?”

“I need you to hear me out.”

“I thought that’s what I was doing.”

“No, I mean not interrupt.”

He thought for a moment. He looked at Quinn. He walked to the window and looked out at New York.

“Okay.”

And he didn’t. He didn’t ask questions. He just stood and listened. He listened as Nio summarized her previous encounters with the victims of the man on the internet. He listened as she described her theory about the woman on the street who had nearly run her over. He listened as Quinn explained about the power lines and the morning light in his bedroom. He listened. And when they couldn’t think of anything else to say, he stood in silence.

“Minus your little detour in Sleepy Eye,” Erving said finally, still facing the glass, “Agent Quinn has been keeping me apprised of your progress. He mentioned your theory about the equipment in Sol’s house and the connection to the paranormal group in Maine.”

Nio nodded. “That’s the trigger.”

“The what?” Quinn asked.

“For the psyop. They wouldn’t bother to hit the frickin’ FBI unless we were getting too close to something. That’s it. That has to be it.”

Erving was scowling. “I’m not saying I believe you, but let’s assume for a moment you’re right. About all of it. Why would anyone care about some fringe group in the middle of nowhere?”

“They must know something.”

“It’s at least worth a trip to Maine to find out, no?” Agent Quinn asked.

“Not unless we can do it in secret,” Nio objected. “It has to look like we fell for it or they’ll come back with something worse. Or burn it all and hide. As of now, they haven’t hurt anybody. We need to keep it that way.”

“I’m inclined to agree.” Special Agent Erving walked around to his desk. “Agent Quinn, I’m going to arrange for you to take a short leave of absence. Officially, you’re looking after your family. You’re not obliged to make contact with this office for the next 36 hours. Understand?”

“Yes, sir.”

“That’s dinnertime Thursday. I expect to hear from you promptly at that time, at which point we will decide whether or not the facts warrant any further inquiries.”

“What about my family?”

“I’ll arrange for a safe house for the next couple days. Our agents will bring them whatever they need.” Erving pointed a stiff finger at Nio. “You still want this one or no?”

Quinn looked at her. “Ms. Tesla is… unorthodox.”

“To say the least.”

“But effective. We wouldn’t have found any of this if not for her.”

“Maybe. But that’s not how it works, son. There are only two, maybe three other agents in this entire building that would’ve stuck their necks out like you just did. The only way we can hold our people accountable for their mistakes is if we also recognize their contributions. However you made it happen, this is your case, Agent Quinn. I’m extending this leeway to you to conduct it how you see fit with whatever resources you see fit.” Special Agent Erving picked up the receiver on his desk phone. “36 hours,” he repeated. “I hope it goes without saying that since you’ll officially be on family leave and Ms. Tesla will officially be detained in her hotel room, I can’t guarantee a prompt response should the you two get into trouble.”

“Rural Maine is a blue jurisdiction,” Quinn explained.

“You should consider yourselves on your own.”

“What about Amok?” Nio asked. “The real one? He’s still out there.”

“We’ll be looking for him. He’s caused the death of multiple people and nearly blew up an agent. We’re going to act as if today’s actions were his until such time as we know better, which means as of right now, he is this department’s primary task. I agree there’s something fishy, but I’m not ready to take it as far as you—not without evidence. So I’m gonna run as much interference for you as I can. What I told you the other day applies broadly. I don’t appreciate the good faith of this office being manipulated for outside gain. I’ll make it look like we swallowed the bait. You have 36 hours to prove me wrong. After that, people will start asking questions I can’t answer.”

“That may not belong enough,” Nio said.

Quinn put a hand on her arm to stop her. “Thank you, sir.” He stood to leave.

“Agent Quinn.” Erving stuck out the phone. “Perhaps before you leave you should call your wife.”

Quinn stared at the receiver.

“Jesus, what do I tell her?”

Snippet from The Zero Signal, a standalone Science Crimes Division mystery, which releases next Wednesday!

May 20, 2021

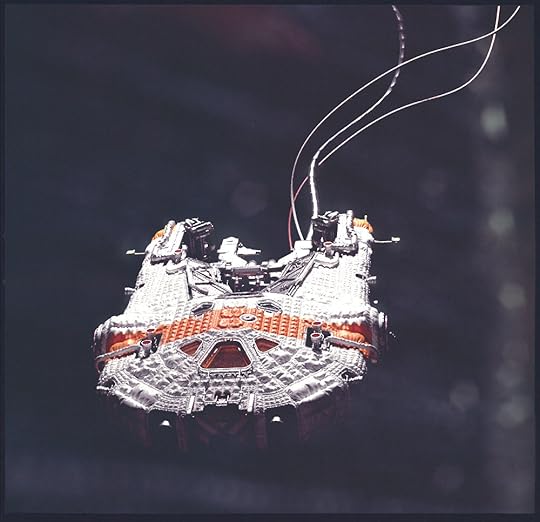

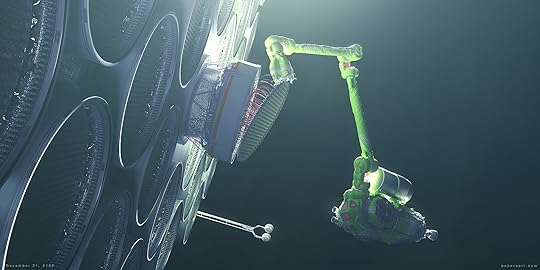

(Art) The Ultra-Real Spaceships of Paul Pepera

There’s not much you can say about the spaceships of digital artist Paul Pepera that does them justice. His NASA-inspired images of space travel in the 22nd century border on the real, partially because of the detail, of course, but mostly I think because of the lighting. Light in space gives everything an ethereal quality, which is probably easier to approximate than grungy atmosphere.

Still, some of these pictures are legitimately stunning, which is why I’ll shut up now. As always, be sure to check out more by the artist here.

May 17, 2021

(Fiction) Cages

The tea kept falling.

The peg that held the shelf was loose, and every time it slipped, the canister of tea would hit the floor and spread its contents over the soft wood. It happened first in the middle of the night, and the sound, although not loud, seemed like an explosion amid the silence of the forest. Nio jumped out of bed thinking an animal had somehow gotten inside. Her left hand was still heavily bandaged then, and she had to pick up the dried leaves one at a time with her right. The following morning, she hammered the peg back into its hole over the sink, but much like the log cabin to which it was attached, the peg was old and hand-carved and the fit was poor and some days later, it came loose again, the shelf dropped, and the canister of tea hit the floorboards a second time, spilling its contents in exactly the same place. It was an expensive tea, imported from a shop in Taipei near the international school where Nio and her siblings were raised in exile. There was no hope of getting more before the end of her convalescence, which meant those few ounces, whose every scent reminded her of her youth, was all she had, and the second spilling awoke in her an irrational frustration, as if it were her life that was falling apart, and she threw down her tools at the sound of it and walked outside to pace.

The cabin was perched at the edge of a crooked wood overlooking an alpine valley through which a small river meandered indecisively. After swelling its banks with the spring thaw, it flooded the surrounding wetland and nursed a small but thriving ecosystem. There was no time Nio had looked out the front and not seen at least one bird swooping among the reeds. Elk and even moose were occasional, if wary, visitors. The sloping ridge opposite was not very high as mountains go and was mostly bare of trees, which made for a less-than-spectacular view, but on clear mornings, the top positively glowed amber in the light of the rising sun, and if Nio hiked the steep rise behind the cabin, ascending through the clusters of lodgepole pines to the castle of rock at the top, she could catch glimpses of the snowy peaks beyond, so many in fact that they seemed to go on forever.

What mattered to her more than the view was that her retreat, deep in the Canadian wilderness, was nowhere near another human being. In fact, for all but the handful of people who knew it from experience, it was effectively impossible to find. She had only heard about it on accident. There were no roads there. She had to be flown in a small aircraft to a remote lake, where the plane landed on the water and deposited her on the shore. From there it was a five-hour hike to the east with only a hand-drawn map to guide her. Everything but the firewood had to be carted on her back, and it took three trips over four days to bring all her food and supplies from the lake shore to the cabin, including the Taiwanese tea that was then scattered over the floor. But that was what she had wanted, a place definitively out of reach of the modern world, and if not for the plague of mosquitoes that seemed to descend on the valley every other day or so, Nio might’ve considered moving there permanently, or so she had told herself at the resplendent sunrise of her second day.

But as that excitement subsided, the prolonged lack of internet stretched every calm minute to the unbearable, which surprised her. She’d been without it plenty of times before, including months at a time when she was an international fugitive, and it wasn’t at first obvious why life at the cabin should be any different. After all, she still had access to a small library in the form of a slim e-reader, from which every nonessential app had been removed (so as not to become a distraction). Other than the accompanying wallet-sized solar charger, it was the only piece of electronic equipment she had brought, and only then because it was impractical to carry enough books on her back to last the duration. But her selections, chosen well before her surgery, were insufficient. She had covered all the usual bases, including an advanced copy of a new paper on cellular automata that she had been excited to read. But after perusing the conclusions, she quickly lost interest. Her brain didn’t want to study rule sets and algorithms. Nor was it very interested in the impressive collection of turn-of-the-century science fiction novels she’d borrowed, most of which had nothing especially interesting to say.

By her third week of convalescence, Nio had already chopped enough firewood to last the entire stay, and she had the arm muscles, and the cut on her left hand, to prove it. She had cleaned the cabin, including removing from it everything that could be removed and wiping down the floors and rafters. The latter in particular were caked in a good bit of particulate ash from the fireplace, and she had spent more time sitting atop those beams than she had on the porch. But it felt good when she was done. It felt good that she was leaving the place better than when she found it. And that, she realized, was what she missed. Unlike earlier episodes in her life, when Nio could look ahead to an entire adult life, the patent fact of her healing incisions reminded her that her time was slipping away, which mean romantic notions about communing with nature and contemplating the meaning of existence, perhaps even writing a memoir on her life as a fugitive, were not what her head or her heart had truly wanted.

There was one unfinished task in particular that vexed her. More than once in those early weeks at the cabin, she woke in the night, her heart pounding at her brain’s reminder that the killer—or killers—known as Amok was still out there, and that it was only a matter of time before he resumed his wicked hobby. She repeated to herself what the doctors told her: she didn’t know for sure the man the FBI had arrested the previous year wasn’t actually him, she didn’t know he hadn’t otherwise stopped or fallen ill, and anyway, she wasn’t responsible for what he did. All of that was true, of course, but every few nights or so, a momentary panic would grip her, and she would wake with a start and get no more sleep until dawn. She’d hoped that some time away, a forced isolation, would break his distant hold over her. If she took away her own ability to get up and check the mod boards for signs of activity, then she might come to accept that the doctors were right—or at the very least, that Amok would come when he would come and that until then, there was nothing she could do.

But the tea kept falling and spilling its contents over the floor. After the second time, she tried using mud as mortar. When that also failed, she moved the canister to another shelf and left the broken one bare. After finding an awl in the shed out back, she took to widening the hole in anticipation of the new peg she would carve. (Nio had never carved wood before. But how hard could it be?) The next morning, when the sun lit the top of the ridge, she finished washing the blankets in the river and hung them to dry. She changed the bandages on her hand, and when the mosquitoes returned, she hiked to high ground, inspecting every passing tree for an adequate branch to claim for her project.

She heard the helicopter well before she could see it. The sound of the blades fluttered faintly on the breeze, so faintly in fact that at first she thought it was the wind. Only after catching an echo did she climb to the top of the rock castle and scan the horizon. She saw it then: a tiny black dot approaching from the south. But as she stood and watched, curiosity turned to concern. Was there some danger? There was no reason why anyone would want to hurt her, but then, there was also no reason for a helicopter to be heading straight up the valley toward the cabin. No one was supposed to know where she was. She had left enough of a trail, she supposed, that she wasn’t impossible to find, but it would take no small effort. Someone would have to be motivated, which instantly made some possibilities more likely than others.

As the sound of the helicopter’s blades grew louder, the cold calculus of risk versus reward got the better of her, and she dropped down below the rocks, which she hoped would be sufficient to shield her. If the interlopers were friendly, then they would eventually reveal themselves as such. And if not . . . Nio had only intended to enjoy a short hike and return to the cabin before dark, which meant she had no flashlight, no provisions, and no shelter from the elements. Her pockets held only a multi-tool and small folding saw. There was some chance she could hike back to the lake shore and from there to an abandoned logging road some miles distant, which, if she followed it south, would eventually deliver her back into civilization. But that was a journey of many days, and she wasn’t even carrying a coat.

The helicopter suddenly grew very loud, and even though she couldn’t see it through the crack in the rocks, there was no question that it had turned the bend in the valley and was descending on the cabin. A moment later, it came: a long-range drone, superficially similar to a twin-bladed cargo helicopter, but larger and with a sophisticated hooking mechanism in place of a cab. Its dual set of counter-rotating blades were very long, like albatross wings, which helped it fly over great distances at high altitude, where wind resistance was lower. The heavy, multi-armed hooking mechanism hung low enough to wrap around the sides of a shipping container, giving the angular black drone a vaguely wasp-like appearance. But it was not carrying a shipping container. It was carrying a cube roughly one-meter square, which it set down swiftly in a clearing between the wetland and the cabin—so swiftly that Nio was worried for a moment that the whole thing might crash. But then, just as swiftly, it rose again and turned back south through the valley.

It was possible of course that someone was watching from the cameras that no doubt covered every inch of space around the machine, but given the drone’s behavior, it seemed more likely that it was operating independently, that it had been given a set of GPS coordinates and a package and it did what it was programmed to do. To the drone, there was nothing any more special about Nio’s remote hideaway than any other place on the planet. Drones just like it, she knew, routinely delivered pallets of food and medical supplies to remote villages in India or herdsman the middle of the Gobi desert or researchers in Antarctica. For all she knew, that particular drone had been to all of those places and more, and would be heading back shortly.

After watching from cover as it departed, Nio turned her gaze to the mysterious gray cube it left in the grass near a stream that cut a furrow to the wetland below. She did not immediately descend to inspect it. Instead, she returned to the cabin to make tea. With the warm cup in her hands, she lit citronella candles and sat on the porch and waited for something to happen. But nothing did, and as the sun got lower, threatening to descend behind the ridge and bring an hour-long dusk, it seemed silly then to think someone was trying to hurt her. Too much time alone was turning her paranoid.

“How long before you start talking to yourself?” she asked aloud.

Nio stomped in her unlaced boots to the grassy knoll where the cube rested at a very slight angle above the water. She stopped when she saw the name. To communicate clearly that the cube’s appearance had not been an accident, her name had been printed in small letters near the top: NIOBIUM TESLA. But there was no return address, no shipping label, not even a corporate logo. There was only a metal handle, pressed to the side, that was affixed to a pair of wires such that if she pulled it, it would tear a triangular section of the cube away and reveal the contents—or so the little printed diagram told her. She did so, and the staccato sound scared a bird from a nearby tree. Inside, some kind of large electronic device—exercise equipment perhaps, or maybe a specialty computer—was inserted obliquely and in pieces, all of which were wrapped in plastic. It smelled strongly of it, in fact, as if the cube had come directly from the manufacturer. There was no note and no instruction manual. The only paper she found was a slim customs receipt, affixed near the top, suggesting the cube had entered Canada at a port in British Columbia and that it had originated in Vietnam.

After pulling the side panels open, Nio was able to slide the heavy base of the device onto the grass, along with a medley of smaller components, and to drag the lot one at a time up to the cabin, even as the last light faded. (The empty cube she left until morning.) With all of the pieces unwrapped and arrayed on the rug in the middle of the cabin floor, she still wasn’t sure what she had. It wasn’t until she attached the curved railing to the heavy circular base that it became clear. It was a personal VR platform. The central section of the round pedestal had a raised rubbery inset that could slide with her steps in any direction, like an omni-directional treadmill, and although it flexed softly under her weight when she stepped on it, she knew it could be stiffened to simulate harder landscapes like concrete or rock. The collapsible railing fit into the base and lifted around her once the machine was active, preventing her from falling off and giving her hands something to grasp if she lost her balance, which often happened in highly active games, and during sex, which were virtual realty’s two biggest uses.

To her surprise, the pedestal had already been charged. Once the control panel clicked into its pedestal at the front, the machine started automatically. The screen indicated it had enough charge for 67 hours of continuous use. But its memory was empty. No VR matrix was locally stored. Instead, there was a small satellite receiver, a puck-shaped device no wider than a coffee mug that could be clamped anywhere with a clear view of the sky. The platform was already paired with the receiver and was configured to connect to a single IP address. Changing the address required an authorization code, which ensured the device could only be put to one use. Nio either agreed to see what someone wanted to show her, or she threw the lot of it in the river.

After sliding the sleeved gloves over her elbows, she put the transparent visor over her eyes and hit ‘Start.’ It took a moment to acquire a satellite connection, but immediately thereafter, the machine displayed a selection box virtually in the air in front of her, asking if she would like to play: Yes or No? All other menu options were grayed, which suggested she had to answer in the affirmative to continue. When she raised her hand to touch the ‘Yes’ button, everything around her appeared to change. There was a brief strobing flash, where she seemed to move sideways through a hyperspace tunnel, accompanied by a jiggle of the pedestal such that it felt as if she truly had been whisked away, and despite herself, she lifted the visor slightly to make sure she was actually still in the cabin.

The VR matrix deposited her in an old brick factory warehouse, not more than two stories high. Rows of arcade video games, all broken and in complete disrepair, were covered in dust and the occasional cobweb. The stochastic detail in the image was exceptional, and for a moment, she thought it was very good VR. In front of her was a standing mirror with a carved wooden frame, like something from Victorian times, and by its reflection, Nio could see she was controlling a telepresence bot—a cheap, headless bipedal robot often used by businesses and government agencies in place of costly travel, or when a needed participant was ill or otherwise unable to make the journey. That suggested her surroundings weren’t virtual at all, that she was receiving a video feed from someplace real.

The robot’s left arm was missing, so Nio raised her right hand and watched in the mirror as the robot did the same. Since executives and dignitaries were rarely robotics experts, they were often hard on the devices, accidentally walking them into pools or off balconies, and the machines’ yellow torsos were like bulky, rubber-trimmed tanks. A heavy bar bent around the back to prevent all the expensive bits from breaking if the machine fell backward, or if it were hit by a car. The small touchscreen control panel was recessed into the front chest for the same reason. Another bar bent over the top to prevent damage from falling, or from falling objects. The arms and legs, however, being the only moving parts, tended to wear out quickly, and were typically replaced instead of repaired. As such, they were lightweight and easily detachable.

Nio opened and closed her fist and watched the robot match her movement as best it could with only two large fingers and one thumb. Telepresence bots were not finesse machines. They could only be used for simple grasping—carrying a tray of drinks, for example, or retrieving a page from the printer—and not for remotely hacking internal systems via a keyboard. The arm looked like it was made of corrugated plastic wrapped around an articulated carbon-fiber tube. Movement at the elbow and fingers was myoelectric. Translucent yellow sacs under the plastic functioned as muscles, contracting or relaxing in response to a fiber optic signal, which triggered an electrical realignment of the fibers. They were not very strong, but then that was the point. A telepresence bot had the approximate strength and dexterity of a five-year-old child—a hard-earned lesson for the manufacturers after the first disgruntled employee used one to beat his former boss within an inch of his life.

Nio raised one leg, lowered it, and raised the other. There the illusion faltered. The leg movements were jerky, and the robot shifted hard with each footfall, which was less a function of technology than cost. Already there were robots that could outperform the most graceful of gymnasts, but grace was expensive, whereas the only movements a telepresence bot had to master were walking, standing, and sitting, preferably without falling over, although they did that quite often as well. Still, the interface was working smoothly, and Nio was able to walk around the mirror with no issues. The room itself was mostly empty. Other than the rows of arcade games and odd bits of debris on the floor. Glass-tile windows near the top tempted a view of her surroundings, but they were too high to reach. The doorway was the only exit, and it led to a long hall that ran left and right along the side of the old building. With no clue as to which direction she was supposed to go, Nio turned left on the theory that there was some significance to her missing arm. Her strides on the sliding track of the VR pedestal were almost perfectly translated into robot movement, and very quickly it felt like she was actually in the factory. The only missing sense was smell, but then, she didn’t imagine it could smell very good anyway. It clearly hadn’t been used in decades. Glimpses of other dilapidated roofs poking above the high windows suggested she was in an abandoned industrial park. There was daylight, whereas it was dark outside her cabin retreat, which gave her a clue as to location, but only a very general one: the factory was somewhere on the other side of the planet.

At the end of the hall was a short staircase going down, as if the adjacent buildings were on a slope and one was slightly lower than the other. Before exploring further, she thought she ought to clear the rest of the floor, a standard video game strategy. You never knew when you might miss something. So, instead of descending, she turned around, only to find debris blocking the other end of the hall. Fallen bricks and metal pipes were strewn across the floor in one spot in a such a way as to prevent the robot’s advance, which seemed awfully convenient. The rest of it was very much clear. When she tried to approach the mess, however, the robot stopped as if it hit an invisible barrier. The track on the VR pedestal wouldn’t budge, and Nio was forced to study the debris from two strides away. It seemed real, but the fact that she wasn’t allowed to approach it suggested it wasn’t really there, that the blockade was programmed, and that her surroundings were neither real nor virtual but a mix of the two: augmented reality—live video seamlessly overlaid with select digital alterations. It was entirely possible that much of what she was seeing wasn’t actually there. The factory might’ve had no roof, for example, or it might not be a factory at all. The robot could be in someone’s home or office with every contrary detail faked by a computer.

Nio turned and explored the space around her by attempting to move the robot toward the walls, but it wouldn’t budge from the central path, not until she reached a “gap” several meters away, where she was allowed to reach the wall under the windows. A long pipe lay on the floor, and she picked it up and returned to the virtual debris, where she used the pipe to dislodge some of the bricks, which instantly caused the rest to fall and clear a path. The lazy player, discouraged by the blockage, would presumably miss whatever lay beyond.

After another right turn, Nio entered a squat nook. On the floor in front of her was a mechanical arm exactly matching the one attached to her telepresence bot. Since robotic joints could pivot 360 degrees, there was no difference between a right and left limb, and when she attached the arm to the bot using the Victorian mirror as a guide, it automatically adjusted for her left side. She now had two hands and half expected a window to appear announcing “Achievement Unlocked!” Since there was nothing else down the hall to the right, Nio returned to the staircase and walked down to the next floor, where she entered a second large storage space at the corner. The room was small compared to the others. Its once-whitewashed brick walls were now cracked and pale. The floor was stacked with old plumbing equipment, most of which had a fine layer of rust. To her right, another open doorway led to a very long brick hall entirely roofed in glass tiles, most of which were shattered or missing. In the middle of the large space, which was dark at the far end, was an enormous industrial vise, like something a junkyard might use to crush old cars.

Sitting inside was a woman.

She had long, dark hair that appeared recently styled and she wore a fancy green dress, as if she had just come from a dinner party. She was trapped and sitting with her back to the heavy cage door that had closed over the space between the steel slabs, presumably to keep anything large from squeezing out while in use. She had her face in her hands and was trembling. Nio moved immediately to help but froze when she saw the dribbles of red that had dried to the side of the bottom slab. She stared at them for a long moment, registering their meaning.

The vise shuddered suddenly and the woman screamed as a tree-sized piston began pushing the metal slab slowly toward the floor.

Snippet from my work in progress, the second installment of Science Crimes Division. The first book, The Zero Signal, goes on sale next week!

May 12, 2021

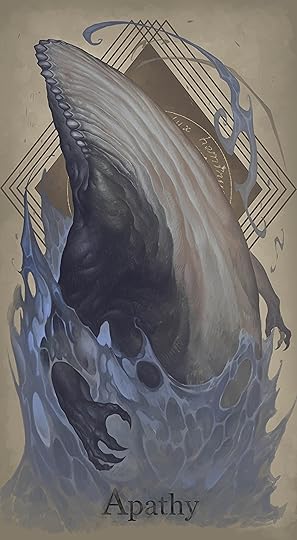

(Art) The Sins of Yin Zhe

Chinese artist Yin Zhe, AKA Midnight-98, has created a series of nightmares, or what we might call demons manifesting various sins and weaknesses. Some of the designs are particularly apt. Prejudice burns with righteous fire. Hate has long, reaper-like arms that allow it to lash out from a distance. Apathy is a whale of a beast. Deceit (who is not labeled in the set below) has a head that is one big smile.

Some of the others suffer in translation. “Inferior” would probably be rendered in English as Inferiority and “Lonely” as Loneliness or Depression, which we tend not to differentiate from Despair. Similarly, while we can understand what the artist was getting at with the nightmares “Rash” and “Evade” — we know people who are rash or evasive — they’re not words that resonate as sins.

But that is not a criticism. Simply, it’s important to remember as you peruse the gallery that these are translations and that the “sins” are more Confucian than Christian, and refer to anything that is not a virtue. If anything, we might be surprised at the overlap.

As as always, don’t forget to check out more by the artist here.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error][image error][image error]

[image error][image error][image error]

May 9, 2021

(Sunday Thought) The New World

Imagine you are good at chess. You have played it since you were a kid, and although you’re not going to win any grand championships, you have competed successfully before.

Now imagine they change chess. In the future, it is announced, chessboards will be a 16 times bigger. Instead of eight squares on a side, there will be 32, meaning the total number of squares will increase from 64 to 1,024.

To accommodate the change in board size, the total number of pieces will also increase from 32 (16 per side) to 128 (64 per side). But that is merely a derivative change, you are told, to fit the game to the new board. Don’t worry! Everything else stays the same. It is still chess. It’s just BIGGER chess. More of what you love!

Very quickly, of course, it’s discovered that humans actually have great difficulty playing on a board of that size. Many of the traditional moves and feints no longer apply, or only apply in certain cases, such as when pieces are clustered in a corner. Players start winning and losing effectively at random, obliterating any merit in their play.

Because f the change, new strategies are required, and all the guides and educational materials have to be updated. Anyone can do that, the proctors say, with a little time and effort. Thus, they say, the game is still fair.

Of course, some players realize you can build those new tools and strategies much, much quicker with machine learning. All it requires is a team of researchers and a couple millions dollars to develop.

Now who wins? The best players in a fair competition? Or the ones hired and trained by the technocrats?

Note, we haven’t changed any of the rules of chess. The “laws” are all the same. The board simply got bigger, introducing more degrees of freedom to move. Anything else was simply derivative.

This is what has happened, and continues to happen, in the developed world this century. You are being told that nothing has fundamentally changed, that the laws are all the same, and everything is basically as stable and fair as it was in 1980.

May 8, 2021

Creativity is part of human nature. It can only be untaught. —Ai Weiwei

May 6, 2021

(Fiction) The Prestidigitator