Rick Wayne's Blog, page 3

May 2, 2021

(Sunday Thought) Illusions Are More Real Than Reality

We like illusions because they create a deeply subjective sense of incongruity. That is, they “break” our brains. In this case, the circles appear to be moving, but they also appear stationary, which creates a feeling that can only be described as “Whoa…”

The psychologist Steven Pinker likes to share illusions on Twitter because of what they reveal about our brains. For example, we read in textbooks that the human brain is not a naive observer of the world but actively constructs what it observes. But none of us really believes that. Persistently throughout daily life, we act as if what we perceive is really “out there” and treat illusions like this, not as if they’re typical of observation, but as if they’re edge cases, special exemptions to the brain’s normally reliable function.

It’s important here to realize that what makes the illusion an illusion is not the illusion bit. It’s the juxtaposition of that with a benchmark which simultaneously demonstrates what we’re actively observing cannot be the case.

Certain drawn illusions depict two images in one — it’s either a duck or a rabbit, or it’s the face of an old woman or that of a young woman turning away. Our brain cannot see both at the same time. That’s really important, because it shows there is some extra layer that we do not perceive between the image and our sense of it. That is, we don’t see the image as it is. We see a drawing of a duck or a drawing of a rabbit — or a face in the electric socket.

That extra unperceived layer of perception that interprets those lines on a page doesn’t go away when we stop looking at optical illusions. It is always there. We’re normally not aware of it, not because it isn’t active, but because the juxtaposition present in the illusion that tells us it can’t be real is missing everywhere else, giving us the subjective sense that our everyday observations are stable and reliable, even when they may not be.

Thus, in a very real sense, illusions are closer to reality than our sense of reality because they reveal where our sense of reality is broken.

April 30, 2021

(Art) The Savage Chaos of Bastien Lecouffe Deharme

Bastien Lecouffe Deharme has illustrated numerous games for some of the biggest names in role-playing, and I can see why. His dark goddesses rule over savage realms of blood and violence, where the cruel and the damned fight for survival by chaos and magic. His subjects, at once resigned and desperate, wield great power but seem to understand that they can be consumed by it as well, and as such are the perfect vehicles for the gamer and his grim contests.

April 27, 2021

(Fiction) The Mandela Spheres

Some advanced readers were so excited about THE ZERO SIGNAL that they have nominated it for Best of the Year on Goodreads, where (at the time of writing) it is #2 on the list!

Readers also nominated it for Can’t Wait Sci-fi/Fantasy, Strong Female Lead, and What to Read in Summer. If you have a Goodreads account, go over and vote.

You can also read the advanced reader reviews here or pre-order here.

Read the beginning here. The selection below is from the middle where the cover image is explained.

Quinn stepped into the conference room at the Boston FBI office. Nio was sitting at the table in her brand-new jacket tapping gently on a laptop.

“What is it with you and high collars?”

“Old habit,” she said without stopping. “I spent a lot of years dodging facial rec. Biometric scans. You start to get so comfortable hiding your face that it feels weird not to.”

Quinn noticed her hands were trembling. “How you feel? You throw up again?”

“Not since this morning.” She stopped typing and stretched both her arms and legs. “And my legs aren’t as stiff.”

“That’s good. Maybe you’re through the worst of it.”

“Silver lining: I haven’t had a headache since I lost the implants.”

“Careful. You’re gonna start sounding like me.”

Quinn pulled her coffee from the carrier and set it on the table. “You know, you’ve been at that stuff non-stop for the last 36 hours. Maybe give it a break?”

“Not gonna ask me how I cracked it?”

“You’ve trained me well. I’ve learned it’s pointless.”

She sat back and rubbed her eyes. “It’s actually fascinating, this stuff he was working on, but I can see why Sol wouldn’t talk about it.”

“Dangerous?” Quinn walked over and shut the door.

“No. Well, not in the sense you mean. Dangerous to his career, absolutely. Humans are all closet essentialists, as a professor of mine used to say.”

Quinn leaned against the glass and crossed his arms. “Essentialists.”

Nio spun her chair. “Okay, let’s say I have a high-resolution maker like they have up at MIT and I make a very high-resolution, 3D reproduction of the Mona Lisa. I program the maker to include more detail than the human eye can actually perceive, meaning it looks completely real. The voxels of pigment are smaller than the width of the rods and cones in your eye.”

“More detail than we can see. Got it.”

“People will still view it as fundamentally missing something, as fake. In their minds, the original has some aura about it that makes seeing it on a wall more memorable and moving experience than seeing the reproduction, even though the reproduction contains all the same perceptible information. If you tell them later it was a copy, they’ll feel cheated. It’s why people collect clothing worn by celebrities and serial killers. People will say a knife used by Charles Manson has some extra evil essence in the metal versus one from their kitchen, which might actually make a much better weapon.”

“Manson didn’t actually kill anyone,” Quinn corrected. “He got other people to do it—like your guy, actually.”

“Okay, but you see my point. It’s the mystique of a vintage car, which drives terribly and keeps breaking down but which gives its owner much greater pleasure than owning a new car, which is faster, cheaper, and safer. If it came out that Sol was looking into occult and conspiracy theories, there would’ve been a ready-made explanation: that he was deranged in some way, that the cloning process was somehow incomplete and what resulted was a biological machine similar to Einstein but missing that mysterious essence that made the ‘original’ so potent. We’re all just copies, right? No one would’ve taken a risk on him again.”

“Damaged goods,” Quinn said.

“It’s the quandary we all realized very early. Fundamentally, I think it’s why Chancery never contemplated writing a novel, even though her head is full of stories. Which it is. It’s why she lies compulsively. She has no other outlet. No matter what she wrote, no matter how awesome it was, it would never measure up. It couldn’t. Nothing can match the mystique of the past, of history. Our genetic donors have all passed into myth, and a real person can’t compete with a myth. Chancery’s ego could never handle not measuring up, so she invents that whole story about Charlotte being limited by her time and how if things were different, she could’ve been Prime Minister or whatever.”

“Could be true.”

“It could. She definitely felt the need to publish under a pen name. I’m just saying the reason Chaz makes such a big deal of it is because people believe in mystical essences. Even scientists, which is why Sol kept this project secret.”

“I thought he was working on the hologram theory.”

“The holographic principle, yes. But then last summer, out of the blue, he started getting into conspiracies in a big way.”

“Last summer? You mean Caulfield?”

“After seeing all those people die and then watching helpless with the rest of the world as we drifted toward another civil war, he found it hard to work.”

“Everyone did.”

“Kinda hard to concentrate on the deep nature of the universe when everything is falling apart around you. I think as a way to deal with it, he started applying the mathematical tools he’d developed on the holographic principle to current events. But to get a useful mathematics of society he needed a baseline. That’s how he got together with Gerry. It was really clever, actually. He wanted a robust data set on things he knew to be false—conspiracy theories like QAnon—to test his null hypothesis.

“That’s how we cracked the encryption, if you want to know. We assembled a key set of words and phrases common to discussions of the Mandela Spheres, which I knew had to be in there.”

“The what?”

“You don’t spend much time on the internet, do you?”

“I try not to.”

“But you’ve heard of the Mandela Effect?”

Quinn scrunched his face. “That’s supposed to be a change in the Matrix, right?”

“Some people think it’s proof we’re living in a complex virtual reality, yes. Others will tell you it’s just a collective false memory.”

“You don’t sound convinced,” Quinn said.

“Well, I dunno. I mean, you’d expect there to be some things like that, just at random. It’s one thing for lots of people to misremember an easy misspelling of a name, but the complexity and size of some of the others makes it hard not to at least be curious.”

“I read once that a majority of people believe angels are an active force in their lives.”

“Whatever. I don’t want to argue. The point is that for people like Gerry, this stuff is real. Someone on the internet noticed that there were large spherical structures, like hi-tech radar installations, in the general vicinity of places tied to various Mandela effects, like Rocky Flats in Denver.”

“So, what are they?”

“The Mandela Spheres? No one knows.”

“What do you mean no one knows?”

“They’re just there. At least with HAARP there was a cover story.”

“Harp?”

“Jeez. You really are out of it.”

“Enlighten me.”

“The High-frequency Active Auroral Research Program is a very large antenna array in Alaska, built by the US government in the ‘90s. Both the Canadian government and the European Parliament held hearings on it.”

“Hearings?”

“Oh, it’s worse than that. Jesse Ventura, the former wrestler and governor of Minnesota, once showed up at the front gate with a film crew claiming it was bouncing mind control waves off the ionosphere.”

“Ah.”

“The community that Gerry is connected to had worked for years assembling an absolutely massive data wiki on various conspiracies—not just QAnon but ghosts and Bigfoot and all that. It’s the kind of project no university would waste its time on. Sol found a reference to it online and reached out. He wanted to analyze the set, look for patterns, for a baseline.”

“What kind of patterns?”

“Entropy, for one. He was trying to create common ground, to show that, whatever we believe, whatever we’re willing to kill each other over, we should all at least be able to agree on what’s false. Because of all the attention that things like HAARP and the Kennedy assassination get, there’s lots of data on them, and that data has characteristics, such as high entropy/low order.”

“How can data have entropy?”

“If you model it like a cloud of moving dots, you can describe it thermodynamically. Sol was doing a bunch of transformations like that. More importantly, he was doing meta-analyses on the transformations. Data can take a variety of distributions, right? It can have a random distribution or a Pareto distribution, like a hockey stick, or a Poisson distribution, and so on. The central limit theorem, which is sort of like the sovereign of statistics, says that a distribution of distributions will tend toward the normal, toward the so-called bell curve, which explains why the bell curve pops up all the time. In most cases, what we actually measuring isn’t a discrete variable but a multitude of them rolled together—public opinion, for example, or human intelligence, which are aggregates of millions of legitimately discrete variables: your genes, your education and upbringing, how much sleep you got the night before the IQ test, all that. The central limit theorem says that as you roll a whole bunch of variables together into an aggregate measure, the shape of their individual distributions will sort of cancel out and make a nice, even bell curve.

“Sol expected to see that in his meta-analysis. In fact, he never thought he wouldn’t. He started out looking for other things. But as he crunched the numbers, he found some anomalies. The distributions for the really wacko theories, like HAARP or Bigfoot, were all over the place, which you would expect if they were fake—random noise, basically. Real conspiracies, on the other hand, are made of real variables, so you expect them to be normally distributed. And that’s what he found, that things like MKUltra and Watergate were legit, that there actually was a conspiracy.”

“Because the data behaved normally,” Quinn confirmed.

“But there was a third category. The data on the Mandela Spheres, for example, was not randomly distributed. It had a structure, just not a nice, normal bell curve. It was skewed.”

“Why?”

“He thought it was an artifact of computation. We don’t have nearly as much data on the older events, which makes them easier to analyze. We collect so much data these days that it’s impossible to crunch it all on a PC. Just the data people’s phones and cars collect by driving by the spheres millions of times a day is massive. Sol guessed that if we had the same amount on the older events, they might show the same skew, that there was a hidden selection bias in what we were retaining from the past, but without the ability to run all the modern data through his equations, he couldn’t prove it. Honestly, it makes me wonder what he was expecting. He would’ve had to have known—” Nio stopped.

“What?”

Her face turned red.

“What?” he repeated.

“Okay, say you’re a scientist and you’re developing a theory, but it’s controversial and may get you fired. You need a powerful computer to crunch all the data, but to get time on an AI or a supercomputer, you have to submit a proposal, and this theory doesn’t fit inside any of the standard research paradigms, which means no institution will fund it. Without the hundreds of thousands of dollars necessary to rent that kind of server time, you’re stuck, right?”

“Right.”

“Unless… you just happened to know the CEO of a major quantum computing company.”

“Jesus.” Quinn stood. “It was right in front of us the whole time.”

Nio didn’t move. She shook her head.

“You were right. You kept pushing me to follow up on the others. And I kept resisting. I wanted it to be…”

“A conspiracy?”

“No. Maybe. I dunno. I didn’t want to believe any of us could’ve had anything to do with Sol’s death.”

“Most people are killed by someone close to them, often someone they love. It’s not your fault. All it means is that you’re right: you guys are human, same as the rest of us.”

“We’ll need warrants. And people who understand physics.”

“I can help with one of those.”

The door opened then and Agents Erving and Cortines entered.

“Sir,” Quinn said, surprised. “What are you doing here?”

“I’m glad to see you both on your feet. Unfortunately, I’m afraid you’re not going anywhere. Agent Cortines, would you please take Ms. Tesla to the hotel and keep her there?”

“Hold on!” Quinn stepped in front of Nio. “She hasn’t done anything. She’s been with me the whole time.”

“I’m very glad to hear that,” Erving said. “It makes for a nice change.”

“What did you tell him?” Nio asked.

“Is there something to tell?” Erving waited a moment, but no one answered. “Agent Quinn, the confinement is for her protection. I don’t have time to go into details right now. We’re busy trying to find the rest of her brothers and sisters.”

“Brothers and sisters?” Nio’s lips pursed. “Wait, what happened?”

“Chancery Brontë appears to have been abducted from her home this morning.”

Nio looked stunned. She didn’t move.

“Given the circumstances, we’re not ruling anything out, including the possibility that you all are being targeted.”

Erving nodded at Agent Cortines, who took Nio by the arm.

“We’ll keep you in the loop, but for now, we need you where no one can get to you.”

Nio turned. “Quinn…”

With that, she was led away.

You can read the advanced reader reviews here or pre-order here.

April 25, 2021

(Sunday Thought) The Arrow of Reality

We are witnessing the reversal of an arrow. For all of human history, it was the physical world that impinged our minds. In the future, it is our minds that will impinge the physical world.

At the smallest scale, this is nothing new. When early man faced the need to smash a hard tuber or crack a nut, he imagined a hammer and fashioned it out of whatever materials were at hand. With experience, he imagined and forged ever more sophisticated tools. That is an example of an idea moving out of the mind and into the physical world, and it is as old as tool use (which is older even than our non-human ancestors since we find tool-making behavior in animals like monkeys and ravens). Everything from art to architecture to computer systems to completely intangible creations like laws and organizational hierarchies are ideas made manifest.

This runs counter to our sense of how things work. We’re taught that the world is reductive, that big things are built of progressively smaller things, and that if you want to know how something works, you have to take it apart and see how the pieces fit together. This belief is enshrined in the dogma that physics undergirds chemistry which undergirds biology which undergirds psychology which undergirds the social sciences.

Another way to say it is that everything you need to know about something, all possible information about it, is contained in its particles such that if you have all the information on its particles, you have all the information there is. There is nothing “higher”.

And yet… we don’t find a single fragment of consciousness in any of the atoms that make up our brains. Similarly, a one-tenth piece of a dollar bill is not worth a dime, and there is nothing in the particles of that one-tenth piece that predicts the value of the whole thing.

We spend a lot of time arguing about justice and we say we want to see more of it in the world, but there is no species of quark that combines to make it.

The reductive materialist can’t admit of justice. To him, it’s an affectation, a label we hang on certain particle-states. It doesn’t correspond to anything “real”. (So, too, the value of money, but we don’t see any of them giving it up!)

On the reductive account, the collection of particles in and around the prehistoric inventor of the flint knife is supposed to contain all the pieces of her invention such that if you just had a complicated enough equation to describe that little corner of the universe, the flint knife would spontaneously appear. No consciousness or creativity is required because no consciousness or creativity can be found in the particles.

The same is true for the invention of writing, the cathedral at Nantes, Beethoven’s 5th symphony, the recipe for Coke, and the sacrifice of every man who died at Normandy. They couldn’t have died for freedom, because no particle of freedom exists.

Note here that reductionism is not the same as materialism or determinism, even though they’re often peddled together. Materialism says the only stuff is physical stuff, while determinism says any complete blueprint of the universe predicts all other blueprints, past and future.

When we admit the existence of emergent properties, which are not contained in bits and atoms, we are not trying to sneak magic back into the world (although I would argue love and humor are a kind of magic). We’re simply trying to take account of everything in it, which includes things like music and memes.

We’re also not arguing for or against determinism, which may yet be true, despite the assault of 20th century physics. Any complete blueprint of the universe, including everything emergent, could theoretically still predict all other blueprints.

In short, emergent properties don’t destroy science. In fact, they enrich our understanding of the world and are just as valid a topic of study as anything else. Science itself, if that word actually refers to any-thing, is one such emergent property.

Back to the arrow of reality. The final turn will come when we can transmute matter. Since it’s all made of the same stuff, it should be possible to pull matter apart and reassemble it into whatever we want. Star Trek, in a very limited way, imagined we would use that power no differently than we use any other tool, to make food or build ships. In other words, a replicator was just a faster way to make tea.

The cyberpunk writers got closer to the truth when they imagined virtual brothels and the exploitation of cyberspace for theft and espionage. But cyberspace, like the Star Trek holodeck and the Matrix, was not imagined to be “real,” and in fact, all of those science fiction properties kept the direction of the arrow unchanged. Physical humans invade those places for shenanigans, only to return to a world that remained more or less as it was before they left.

(Technically, the holodeck used real matter and energy, “force fields” and matter replicators, to simulate reality. The point is that it was a simulation and that it was contained in a box, and when you exited that box, everything was as you left it. Any deviations from that — the emergency medical hologram from ST: Voyager, or that time Riker got copied by the transporter — were expressly represented as malfunctions rather than intended uses.)

Blade Runner and its offshoots got closer to reversing the arrow when it imagined what it would be like to be a synthetic human. But again, even there, the point was to create a replica of a real thing, and so to remain bound by the attributes of the physical world.

We will still make replicas of course, even when we can transmute matter, but that will be among the most pedestrian of its uses. Our creations will not remain in a box. They will not be shackled as slaves. Our ideas will alter the very structure of the physical world. Like a bower bird clearing the forest floor to make room for its showcase, we will alter our environment on a whim, and alter it again moments later. We won’t just make replicas of things molecularly indistinguishable from the originals. We’ll make things only imagined, like unicorns, and things that were never presumed to exist. We’ll eat colors and live in houses that change shape with a gesture. We’ll alter our bodies, exit them, or inhabit several at the same time. We’ll be a fish, and then a dream.

To the degree we wish it, everything will be determined by the contents of our minds, not the other way round, meaning that Morpheus’s question in The Matrix (“What is real? How do you define reality?”) will be irrelevant. There will be no meaningful border between our mind and reality. Our mind will be reality.

Before transmutation — probably long before — there will be programmable matter. It will not be infinitely plastic, but it will be able to change in a variety of ways: to assume different shapes of the same mass, perhaps to change color, temperature, or conductivity within a given range, and so on. A recent science fiction example, which will probably bear little resemblance to the real thing, is the Iron Man suit in Avengers: Endgame, which uses nanotechnology to break itself down and reform into various preset configurations.

Of course, even the more realistic version of that is a helluva long way off. But to give you a sense of how the arrow is genuinely drifting, even in our time, this is the work of Chinese artist Zhelong Xu, who has all but destroyed the difference between digital and physical sculpture.

One of the two images below is a photograph. The other is a digital render. Can you tell the difference? I can’t.

More important than the distinction is how Xu’s art moves between realms. The statue in the photograph (whichever one that is) was created from a render. By 3D printing molds of his creations, Xu can cast them in ceramic or bronze, meaning his ideas flow on the reverse arrow — from his head into bits (0’s and 1’s), and from bits into atoms, and from atoms back the traditional direction into his head, where he can ponder and alter them again.

Of course, the process now is fairly time consuming and still requires a good amount of expertise. But it’s amazing to me how indistinguishable the versions are. The white goat below is a digital render with extra surface texture added. The black goat is a photograph of a glazed and fired ceramic cast created from a 3D print of the original base digital sculpture. (Click for detail.)

You can find more by Zhelong here. I recommend checking him out. (See if you were right about the images above.) I would guess that you won’t know what’s “real” unless he tells you, because it no longer matters.

Digital renders are things in the world. In other words, they exist, and our sense of reality must expand to include them, just as it must expand to include justice and humor. All of those things are real; they’re just not made of atoms. One day, they are going to rule everything that is.

April 22, 2021

A bank is a place that will lend you money if you can prove that you don’t need it. ― Bob Hope

April 19, 2021

(Art) The Dark Gods of Andres Rios

Mexican artist Andres Rios sculpts dark gods, both old and new (including several Aztec deities). While some are divine, others are machine. All are tortured and immortal, their skulls bared or barely covered by masks, and they walk among us dealing death and punishment in the name of whatever dark faith animates and perverts them. But we worship them still, and cling to their violent affections.

Find more by the artist here.

April 16, 2021

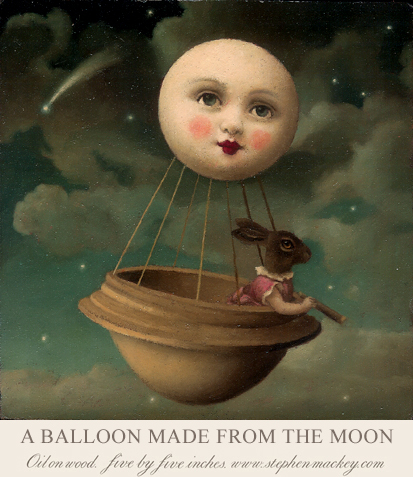

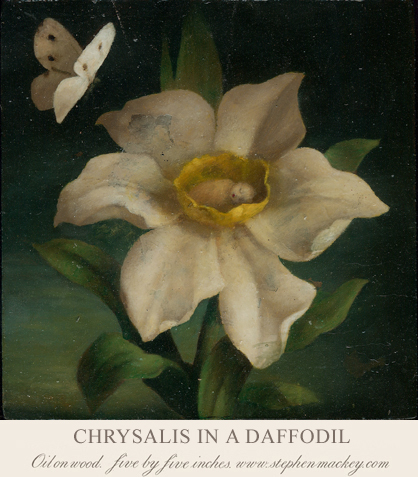

(Art) Stephen Mackey’s Illustrations From a Book You’ve Never Read

I love art that tells a story.

Stephen Mackey’s art tells of dark romances and children’s fables from the world behind the wardrobe or the other side of the looking glass. The self-taught UK artist paints Georgian and Regency fantasy scenes — ghost stories and village myths — that hint of sinister plots, whimsical adventures, and the eternal fancy of youth. They are, as the artist himself described them, “illustrations from a book you’ve never read.”

Some of his paintings are quite small, a mere five by five inches, which adds to their secretive folly. You have to lean so close to see them that it seems you might fall in. If you do, don’t linger. I’m told those that linger may never get out again.

Find more by the artist on his website.

April 14, 2021

(Fiction) The Score

Esmeralda Gonzales was more pregnant than any woman had a right to be. She carried a baby and a load of bad news and bore both with grace and good deal of pride. She was going to be a mother, and she was going to be happy, even if she had to do it alone.

She sat in the bright foyer of the hospital and watched John Regent approach from a bank of elevators. Angled glass stretched to the height of four floors overhead and cast the sunlight in all directions. It was like being inside a giant sculpture of a waterfall.

Esme waved as he passed the information desk. She had only met Captain John once before, but she felt she knew him well. Her husband hadn’t shut up about his new friend. She’d heard all Regent’s stories secondhand.

“Captain John.” She smiled. She struggled to rise from the waiting room chair.

“Don’t get up.” Regent raised his hand as he stopped and took Esme’s grasp in a firm but awkward finger-shake. “You look tired.”

Esme gave a look as if to say it’s expected. She wore the clothes of a woman who cleaned floors for a living. She had dark hair, a plump face, and broad shoulders that reminded John of a wide river, wise and strong. But she was worried.

“Thank you for coming down.” She spoke with the spice of a lifelong bilingual.

The TV on the wall switched from scrolling weather forecasts to footage of the Chinese nuclear disaster. Smoke rose from a city near the coast. When the plume reached the clouds, it bent like a broken limb as the prevailing winds carried radioactive dust out over the mainland. No one knew how bad it would be.

Esme saw John looking. “It’s horrible what happened. Those poor people.”

John nodded. “Gabe’s checked himself back in.”

Esmeralda turned from the disaster. “He called, said he was being admitted, but I didn’t believe him.”

“That’s understandable. After everything.”

“I want him to get help.” Esme felt her stomach.

“How’s the baby?”

The young mother smiled. “So good. I went for a checkup this morning. The doctor says another two weeks. I don’t think I will make it!”

“You’re gonna do great.”

Esme kept her smile but the rim of her eyes froze in a panic as she turned her gaze to the side. “I’m not ready yet. We’ve been so busy. Dealing. And work. I have to put the baby first now.”

John knew what that meant. He waited for the rest.

“Will you look after him?”

“I may not be around for very long, but I’ll do what I can.”

“He needs help, Captain John. I told him I can’t be with him anymore. Not until he’s better. Not now that the baby’s here.”

John nodded. Esmeralda Gonzales had been patient enough. Gabe was a lucky man.

Esme rubbed her belly. She gave Regent a weak smile. “I just wanted to thank you. In person.”

“It’s no problem. I didn’t do much.”

“Yes, you did. I don’t know how, but you brought him back.” Esme looked at Regent with her head tilted to the side. “Thank you. So, so much. Thank you.”

“Am I interrupting?”

The voice came from behind him, but John knew it. He’d seen her around. Ayn.

“No.” Esme looked up.

Ayn stood behind the captain with one hand on his chair.

“I have to go to work. I just wanted to say thank you. That was all. I think Gabe wishes he was more like you.”

John wanted to help her up, but she was on her feet before he could move his chair. “Take care of yourself. That’s precious cargo.”

“Thank you. Goodbye, Captain John.” Esme smiled again and walked to the sliding doors at the front of the hospital.

Regent looked at the TV. Some scientist was explaining the dust was likely to reach into central Asia. Everyone was worried about what would happen to the rice crop and whether it would be able to feed a few billion people. One disaster breeding another.

Ayn walked around to face the soldier. She was holding a thin file.

“Captain, I’m—”

“I know who you are. What do you want?”

“I thought it was time we had a chat.”

John didn’t respond.

“I went to your room but you weren’t there.” Ayn waited for a moment, but John didn’t extend an invitation. “Fine. We can do it here. Mind if I sit down?” She sat in Esme’s chair without waiting for a response. “John Michael Regent. Army code name Nomad. That’s right, isn’t it?”

“Not anymore.”

“You have family coming to get you.”

Regent watched through the windows as Esme waddled down the sidewalk toward the parking garage next to the main building.

“Dr. Zabora hasn’t discharged you yet.”

“Nope.”

“Your dad’s retired, is that right? He could always come later.”

“What’s your point?”

“It’s a long drive from Fort Washington. Wouldn’t want him to come all that way for nothing. Or are you counting on your stepmother?”

“What about her?”

“According to Dr. Zabora’s notes, there was some conflict between you and her. When you were a teenager. The doc seems to think that’s why you joined the army instead of accepting that athletic scholarship—so you didn’t have to go home for the summer or on holidays.”

“We don’t get along so well.”

“And yet, here you’re ready to pick up and go live with her again. Why is that?”

“That’s where Pops lives.”

A group of people, including two doctors, laughed on the far side of the bright room. Must be good news. John watched them smiling.

“You have a younger sister in Delaware. Thirty-seven, divorced, two kids. Works at Walmart and rents a two-bedroom apartment. No room, I take it? Did you even ask?”

John didn’t answer.

“Your little brother is out West. But you cut ties with him years ago. He got involved with a gang, is that right?”

Regent was stoic. He stared at the smiling faces.

“According to Dr. Zabora’s notes, you gave him an ultimatum. Get out of the gang or leave the family. How’d that work out?”

John looked back. “My stepmom isn’t a healthy person. He’s the youngest, so she took things out on him longer. When he grew up, he acted out. For a long time, I thought I was responsible for him, for what happened. But I’m not. He’s responsible for himself.”

“Meaning what?”

“Meaning it worked out as best as it ever could.”

“We both know why I’m here, Captain. I’ve spent the last few days becoming an expert on you. You’ll be happy to know the staff here has nothing but good things to say. Seems you’re one helluva guy. Every single one mentioned you like to tell stories. I got to hear a couple. I liked the one about the dead cat.”

“I’m so happy.”

“What happened to that guy?”

John squinted at the light coming in through the high glass. He was getting a headache. “Just say what you gotta say.”

“I don’t have many stories, not that I can share anyway, but I think my new favorite has to be good ol’ Private Millard. Do you know him?”

John shook his head.

“He’s a patient here. I’m not surprised you haven’t met him. He doesn’t get out much. He’s in a coma.”

“That’s tough.”

“Yeah. There was an accident at a base down South. Something broke. Something fell. Lots of yelling and shouting. Poor Alvin was just in the wrong place, I guess.”

“This story sucks.”

“Oh, I’m not to the good part yet.” Ayn leaned over the arm-rest. “Private Millard gets hit in the head and he goes into a coma. He gets shipped here to the military’s fancy new trauma center. Nothing happens for a week or so. But then, last Saturday afternoon, Alvin—who never scored above average on any of the army’s aptitude tests—woke up from his coma, disabled his monitors so that the nurses wouldn’t be aware of his absence, locked his door from the inside, snuck past the hospital security cameras—not a single one so much as caught a glimpse of him, and you know how hard that is—procured street clothes and a disguise, infiltrated a crack house across town, and took down three armed men after being shot in the leg. Isn’t that amazing?”

“You need to work on your delivery. The story takes way too long to develop and the punchline is predictable.”

“Maybe you could give me your version.”

“Never met the man.”

“What’s this symbol?” Ayn pulled a color printout from her file. Three circles connected in the center by three lines. “You Googled it from the fourth-floor nurse’s station shortly after you were admitted.”

John didn’t answer.

“After that, you either figured out we had the whole network on watch or you learned to cover your tracks better.”

Regent looked Ayn up and down. She was a blank. She was dressed nicely in a white shirt and gray slacks, but there was nothing to identify her as a human being, nothing personal. That wasn’t an accident. He knew the type.

Ayn put the sheet back in her file. “What were you looking for, Captain?”

“Funny thing about you people.” John shook his head in disgust.

Ayn raised her eyebrows. “Us people?”

“Bureaucrat spooks. You act all noble, but you don’t actually care if the country’s secrets are being stolen.”

“Oh?”

“Not as long as you know they’re being stolen. Known security breaches take months to fix, years sometimes. I’ve seen it. And why would you care? That’s a score for the other team. They already got it. Fixing it quick doesn’t change anything. They already got one over on you.

“But when something new pops up . . . Well, then you’ll move mountains. It’s a chance to score, to get one over on someone else. It’s all about reputation, appearances, being seen as the best, the smartest, the most ruthless. Ain’t got a damn thing to do with national security.” John said it with acid.

Ayn didn’t deny it. “And leaving Special Forces for a team that doesn’t exist had nothing to do with ego? With ‘being seen as the best?’”

“You like stories, huh? Okay, here’s one for you. Once upon a time, something falls out of the sky. Something big. Lands in Siberia near the Kazakh border. Only it doesn’t burn up, not totally. Leaves a big scar in the ground. Suddenly everyone’s worried that the Russians or the Chinese had a satellite—or worse, some kind of orbital platform—that no one knew about. My God, that could affect the score.”

Ayn scowled.

“My team gets mobilized. And we’re the best, so we get there first. Only for us, being the best means we don’t ever get seen. Radar absorbent wingsuits out of the back of a modified commercial aircraft, dropped with oxygen masks from thirty-five thousand feet. We each covered almost a hundred miles in the fall, crossed the border in the night sky. We met at the rendezvous and made it the rest of the way on foot. When we got—”

“Don’t tell me.” Ayn was flat.

Regent stopped. “I thought you’d have seen the files, big important person like you.”

“They’re gone.” Ayn sat back and crossed her legs. She was unapologetic.

“Huh.” The soldier frowned. She must have looked into the symbol during her investigation. “You tellin’ me you aren’t curious?”

“No.”

John smiled. “Yes, you are. You hate not knowing. What happened? You ask and get an earful of ‘don’t ever ask again’?”

Ayn leaned forward again and pulled more pictures from her file. She tossed them onto a little side table covered in old magazines. “The police documented six incidents, but I’m guessing there were more.”

Regent ignored her. “This thing, this smoking wreck, whatever, was over eighty meters long.”

“Very few witnesses. But like you said, you guys are trained not to be seen.”

“Burnt to a crisp. But it was clutching something. It had curled around it, protected it with its life. Looked like an egg.”

“The eyewitnesses described some pretty bad ass hand-to-hand techniques.”

“But it’s still hot, and before we can get it open, another team shows up. We heard them coming, thought they’d be Russian.”

“Do you know what poor Alvin Millard did before the accident that put him in a coma?”

“But they were private security. Contractors. Only not like any I’d ever seen.”

“He was a helicopter technician. Guidance systems, mostly. Gyroscopes or something.”

“They had some crazy tech. And signed, authenticated orders for us to hand over everything to them.”

“According to his records, the last combat training he received was in basic.”

“They knew about us, knew we’d be there. And the Russians never showed.”

“You and I both know about the only thing they teach in basic these days is how to follow orders and piss in a pot.”

“That smoking hulk was something, but those orders are by far the damnedest thing I’ve ever seen.”

“Since he’s in a coma and can’t do physical therapy, he may never walk right.”

Regent stopped and the pair stared into each other in the eyes.

John went on. “Their uniforms, their tech, it all had that symbol on it. Looks like there’s a new team in the spy league, and it looks like they’re winning.”

“Listen, brother—”

“Ha! That why they sent you? They think you my sista?”

“No, they sent me because I’m damned good at what I do.”

“But here you is leanin’ on it.”

“Come off it—”

“I ain’t your brutha.” Regent leaned into it. “My granddad taught me what it means to be black. It’s about a helluva lot more than the color of your skin. You stopped being black a long time ago.”

Ayn did her best, but John was serious, and it stung.

Ethan walked over and looked down at John. He was worried. “John.” Very worried. “It’s Gabe.”

“Shit.” Esme must have said something.

Ethan was pale. “He’s upstairs.”

Ayn shot Ethan a look. “The Captain and I are—”

“We’re done.” Regent spun his electric chair and rolled toward the elevator.

Ayn stood and held up the folder. “This was suspicious enough to get some serious people interested.”

John stopped but didn’t look back.

“You know the people I mean.”

Ethan looked between the captain and the spy.

Ayn took a step forward. “They’ll be here any minute now.”

Regent looked at the clock on the wall. “But they ain’t here yet.” He did his best work under pressure. And his mission wasn’t over. He turned to Ethan. “What floor?”

Excerpt from Episode One of THE MINUS FACTION, free to download on Amazon.

April 12, 2021

(Sunday Thought) Two Temporal Paradoxes

The second installment of the SCIENCE CRIMES DIVISION series involves a murderer who remembers the future instead of the past. As I’ve been working through the plot, which is tricky, it occurred to me that there are at least two kinds of temporal paradox.

The first we’ll call a hard or cut-loop paradox. This includes the famous grandfather paradox, where you go back in time and kill an ancestor such that you can never be born to do it.

The second type, what we might call a soft or closed-loop paradox, would include closed, timelike curves, a theoretical space-time loop first proposed in 1937. Here, two or more temporally distant events can be seen as both cause and effect of each other. For example, if you went back in time and gave the scientist who invented time travel the means to do it, then your travel to the past would be both a cause and an effect of itself.

Although cut-loop paradoxes are the most commonly imagined, closed-loop paradoxes are hardly new to science fiction. Heinlein used one in a short story, and a three-point version was used in “All Good Things…”, the concluding episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation — although in that case, it was a contrivance by the omnipotent being Q and not considered part of the “real” timeline, which is a convenient plot device for sidestepping the issue!

Physicists like to think paradoxes are impossible. Stephen Hawking’s chronology protection conjecture and Igor Novikov’s self-consistency principle suggest that the universe is structured to prevent them (even while admitting they happen at the quantum scale). There’s also a version of the Fermi paradox that gets at the same skepticism by asking: if time travel is possible, where are all the time travelers?

But these are little more than thought experiments. While there is no solution to a hard paradox, strictly speaking, we don’t know that the soft variety violates the laws of physics. In fact, the possibility of closed, timelike curves was confirmed to be consistent with the theory of relativity by Einstein’s friend and famed mathematician Kurt Gödel. The history of the entire universe may be such a curve.

Whether that’s the case or not, it does seem as though local, closed-loop paradoxes could appear as tiny anomalies inside space-time, eddies that exist as both cause and effect of themselves, a possibility I will be exploring here on earth in the second SCIENCE CRIMES DIVISION novel, where it will pose a thorny challenge to Nio and the team. How do you catch a man who already remembers your every attempt to do so?

Speaking of temporal paradoxes, you may wonder how it is a Sunday Thought appears on a Monday. The world may never know…

But while you’re pondering that, go vote! Someone nominated THE ZERO SIGNAL for Goodreads’ Best Books of 2021, but it needs votes!

Voting is easy. Just click here and scroll down to the book…