Rick Wayne's Blog, page 9

January 13, 2021

(Art) The Supernatural Sci-Fi of Alex Andreev

Russian artist Alex Andreev creates eerie images of haunted technology and otherworldly threats, from aliens to kaiju to chthonic monsters. The title image was the inspiration for a sci-fi short I am currently finishing, “They Eat Humans, Don’t They?”

Find more by the artist on his ArtStation page.

January 11, 2021

Same As The Old War

“With an enemy committed to fascism, advocacy—the threats, the words—are not mere dogma. They are themselves weapons—weapons of incitement and intimidation, often as effective in achieving their ends as would be firearms and explosives brandished openly.

“Nevertheless, it has become necessary to ask whether advocacy of fascism can be effectively regulated in the United States. Our enemies, after all, swaddle their calls to barbarism in the language of religious duty and political dissent. These lie at the very core of liberty in an enlightened and thriving democratic order. So luminous does free speech shine among our values that it is enshrined in the very first amendment to the Constitution.

“But… do we so lack confidence that we are unable to say with assurance that some things are truly evil, and that advocating them not only fails to serve any socially desirable purpose but guarantees more evil? Must our historical deference to opinion, however noxious, defer as well to a call to arms against innocents, or a call to destroy a form of representative government that protects religious and political freedom? May we not even ban and criminalize the advocacy of fascism?

“Without security, there is no liberty at all. The fact that government is made up of human beings, and that human beings are certain occasionally to abuse any powers given them, is surely a rationale for narrowing those grants of power; but not for eradicating them, or reducing them to a quantity that fails to protect or even to take account of the higher interest that impelled the grant in the first place. Individual abuses of dissent are bad, but undermining the framework that ensures the right to dissent is immeasurably worse.

“Moral clarity, moreover, postulates that some evils are so palpable we need not further test them in the marketplace. There are relatively few of them, but they do exist and we need not fear we are wrong about them. Such recognition is critical to the functioning of a healthy society. Do we really need additional ideological thrust-and-parry to know, for example, that the advocacy of fascism is condemnable under any and all circumstances?

“Anxiety over ‘chilling effects’ is the most curious and overwrought of all concerns. Is it realistic to believe that we would actually lose the benefit of any idea worthy of the name were we to ban the advocacy of fascism? Exactly what meaningful dissent will we miss if we proscribe the advocacy of murder?

“The point of a market is a free exchange. Fascism perverts the very concept: seeking to compel acceptance not by persuasion but by fear, it is an exchange at the point of a gun. When it fails to win such acceptance, it does not go back to the drawing board to develop a better message or write a better book. It kills, massively. Why then should government hesitate either to ban or to use every legal tool in its arsenal, including criminal prosecution, to convey in the strongest terms that the advocacy of fascism in this day and age is entitled to no First Amendment protection?

“In America’s bumptious, bounteous marketplace, there are no limits on words as the building blocks of ideas, or on ideas as the legitimate instruments of persuasion. Racism has no place in such discourse. It is the function of law to express our society’s judgments. Ours should be simple and humane: words that kill are not words we need abide.”

The text above was copied from a 2005 essay by right-wing prosecutor Andrew McCarthy on the threat of al-Qaeda. His arguments were later cited by Newt Gingrich as a justification for the curtailment of civil rights, especially for Muslims, in order to fight Islamic terrorists. Simply change “terrorism” to “fascism,” as I have done, and it could be any Democratic pundit writing today. Thanks to journalist Glenn Greenwald for pointing out the essay.

January 10, 2021

(Fiction) The View From Space

After the events of this week, it only seems appropriate to share this one again…

In 1848, I was living in Hungary—or what was then Hungary. That was the year people across Europe finally imagined change. There were marches and demonstrations right across the continent, many of which broke into open revolution. It started in Sicily, but we didn’t know that at the time. It was the actions in France and Germany, more rumored than factual, that kindled us. News didn’t spread by wire. It had to be carried by hand or hoof. That year, it came in from everywhere. Nothing like it had happened before. Nothing like it has happened since. Denmark, the Netherlands, Italy, France, Germany, the Austrian Empire. The world seemed on the verge. How could it not be, when so many had risen in protest?

But it failed. All of it failed. We couldn’t believe it. I still can’t, if I think about it. It doesn’t seem possible. I suspect those in the Arab world felt much the same when their Spring turned immediately to winter.

In school, if you learn about 1848, you get a summary of what happened as if observed from space. You learn that tens of thousands of people died but not any of their names. Many more were beaten and exiled. Families were ripped apart—or destroyed utterly—each with a story. And for what? A handful of reforms in the Low Countries? The eventual abolition of serfdom in the lands ruled by the Hapsburgs? I can tell you we imagined quite a bit more. We were beaten and shot and bayoneted and trampled for it. And when we woke the next morning—those of us who did— and nothing had changed, we envied those who had died, for they had died in noble cause. They lost their lives, but we lost our hope.

I remember there was a massacre in the town where I sought refuge. We called it a massacre. Some men started arguing outside a pub. A fight broke out. No one knows why. It could’ve been between a loyalist and a revolutionary but it could’ve just as easily been about a woman, or cards. But there was so much agitation then that soldiers came. There were no police. Only the army. And soldiers can do two things only: shoot or not shoot. So they shot, and four men were killed. A successful keeping of the peace in the eyes of the governor.

The next day, anger having simmered all night—stoked by the fires of rumor—a crowd gathered. They were led by a man we called Montaigne. That wasn’t his real name, but back then everything French seemed sophisticated. Progressive. So we called him Montaigne and he led us like a serpent through the streets so that our numbers could swell. And they did. By the time we reached the hospital, we were hundreds or more. When I say hospital, I don’t mean a house of healing. It was a squat stone building that had once been a monastery. One didn’t go there to get well. One went there to die and not infect anyone else. The crowd called for the bodies of the dead men, for there was no morgue. After whatever bureaucratic necessities had been completed, the dead were carried down the street—in the open on a cloth stretcher—and buried in the graveyard, sometimes in nothing but their skin. But there weren’t any bodies at the hospital, we were told through a crack in the door, not from the massacre. They had already been given rights and interred. The governor’s men had seen to it.

It’s hard to describe what followed with any sense because it didn’t have any. There were shouts that it was a lie and the men’s bodies were being kept from us. Some people thought we should storm the hospital. Others didn’t even understand why we were there.

“What need do we have of bodies?” a grisly old man asked me.

Feeling his control of the crowd slip, Montaigne stood on an upturned cart and addressed us, but there was no electronic augmentation, and it was very hard to hear, especially over the confused chatter, and soon the competing calls resumed. If you believe the history books, these were calls for land reform, or the reinstatement of certain legal rights, or the abolition of aristocratic excess. Standing on the ground, you would’ve heard all of that and none of it. If there was a common theme, it was return—to times remembered fondly. In truth, those days weren’t very good either. Nor did they remember them. They remembered stories told by the elderly, who are perpetually dissatisfied with how things turned out. My old fellow was very put out that the crowd contained several foreigners, which is to say non-Magyars, myself included. For him, the tragedy was not that Hungary was ruled by an aristocracy. It was that so many of his governors and lords were Austrian—or even, by God, Romanian!—and that these foreigners could never be trusted to treat Magyars fairly. He wanted them out. He wanted Hungary for Hungarians, even though such a group, which was just then being invented, had never before existed.

Others in the crowd disagreed, for I heard their chants competing with the rest: an end to conscription, the return of a local pagan festival that had been abolished by the bishop, the eternal dream of fewer taxes—and yes, land reform. It was Montaigne and his men who argued for revolution. I remember his lieutenants circling the crowd like sharks as he spoke, calling out from different places to make it seem that violence was fomenting, or else to shush the dissenters so that the great man could speak. From what I heard his arguments were not entirely unpersuasive. The Hapsburgs, he pointed out, had ample opportunity for reform—centuries, even—and they had persistently failed. How many chances were we to give them before we “took our destiny into our own hands?”

The wording, I’m sure, was intentional. It left everyone free to imagine a different “we.”

But our Montaigne was only a mediocre orator, and a crowd is a slippery thing. We could feel him struggle to hold on. For their part, I’m sure the hospitalers were terrified. Nor could I blame them. In a panic, a body was brought out the front—an older man with a bald top and a stubble of a beard, dressed in simple breeches and a bearskin tunic. A farmer or herdsman. From his perch atop the cart, Montaigne pointed suddenly to the door, a gesture that nearly caused the bearers to drop the body. Men from the crowd rushed forward and grasped the cloth stretcher and hoisted it in the air and the crowd cheered, momentarily elated at their success but unsure what they had achieved.

By chance, the dead man’s wife was among us. Whether she had come out of the hospital or had joined us earlier, I couldn’t say, but she ran to the body of her husband and tried to pull him down. She was pleading with the men, who had broken into slogans and cheers, but I don’t think they heard her. In the jostle, they rebuffed her repeatedly as they carried the corpse of her husband into the street. The body had now become the locus of the crowd, its center of gravity, and everyone swirled in orbit, desperate to touch or merely glimpse the holy martyr who had died nobly for the cause. Montaigne’s followers pushed through the tangle of bodies and practically forced their leader’s hand onto the stretcher. It wasn’t necessary that he support its weight, merely that he be seen touching it. Slowly, the competing calls narrowed to a few and then blended into one.

As the undulating crowd crept down the street, I spotted the old woman on the ground near the upturned cart. The cart’s perplexed owner stared at it with a hand to his forehead, wondering how he was going to right it again, and so his livelihood. The elderly wife was scuffed but mostly unhurt. She just looked confused.

“What are they doing?” she asked me as I helped her to her feet. “My husband wasn’t a revolutionary. He dropped dead castrating a sheep!”

The crowd carried the body of the herdsman to the governor’s mansion, where in a series of short, rousing speeches, he was praised for his courage and sacrifice in the battle against tyranny. The timing was not an accident. The governor was then supping with some guests, dignitaries from another part of the empire, perhaps even the capital. It was because of their arrival, in fact, that the governor had given the army such unusual latitude to commit violence on behalf of peace. It was widely suspected that the purpose of the visit was to coordinate the empire’s response to the civil unrest then sweeping across the whole of Europe. But that was speculation. What we knew for sure was that the men and women inside that mansion were eating well. We knew it because we were the ones who had grown and delivered the feast. In the days preceding the dignitaries’ arrival, two sides of beef, several pigs, four casks of Tokay, and a mountain of fruits, breads, and cheeses had been brought to the mansion. The arrival of the crowd coincided with the consumption of the finer of those goods. We knew it, just as we knew we would be waiting for scraps to be thrown out the back at dawn the next day.

The governor’s response was swift, as if already contemplated. The second- and third-floor windows facing the square, all of which had been covered by heavy curtains, opened simultaneously, and long-barreled muskets jutted out. There was one brief moment of silence before they fired. Then there was only panic. Three were killed instantly. We knew because their still bodies never moved from in front of the gate. Several more, men and women both, had their shoulders shattered or heads cracked by the musket balls. As their friends dragged them bleeding through the panicked crowd, the muskets withdrew and the next set took their place. Another volley was loosed, to lesser effect. Among the victims was the dead herdsman, reborn a martyr and killed again. His hoisted body had been used as shield by Montaigne and his supporters, who huddled underneath as they scurried from the square. The corpse was later found in a stable, riddled with five holes, one each for Montaigne and his lieutenants, who survived and fled to another town, no doubt to repeat the pantomime again, this time armed with stories of their bravery in the face of massacre. I could never say they had caused the fight at the bar the day before, nor do I have any evidence of it. But it wouldn’t have surprised me.

No less than twelve people died, probably more, although there were only three corpses in the square. The rest fell to sepsis over the following days. The morning after, a handful of brave souls, rightly surmising that few of us would dare approach the governor’s mansion so soon, enjoyed the bounty of scraps from the feast, tossed as usual out the back. They ate like kings, they said. The townsfolk decided this was a kind of treason, and the men were beaten to death in their beds. The women were exiled. From there came a quick descent into lawlessness, and the revolution bloomed in full.

I’ve not known anyone to suggest it, but I think the most lasting effect of that year was the birth of communism. Marx and Engels wouldn’t publish their infamous book for another two decades, but that’s only when the idea reached maturity. It was born in the failures of 1848, and everything that happened because of it—the long catastrophe that was the 20th century—happened in a sense because a handful of old men chose to fight among themselves rather than share their bread. But it is very hard to know that, let alone recognize the same forces in our own present, in the view from space.

rough cut from the conclusion of FEAST OF SHADOWS. Available now.

January 8, 2021

(Art) The High Illustration of Jon Foster

Foster is a cover artist and illustrator whose detailed, colorful works bridge the gap between illustration and painting. While rich and detailed like traditional painting, they consciously use the techniques of stylized illustration, such as the use of symmetry and angular swirl of clouds or bend of the branches of the tree in the images below.

December 29, 2020

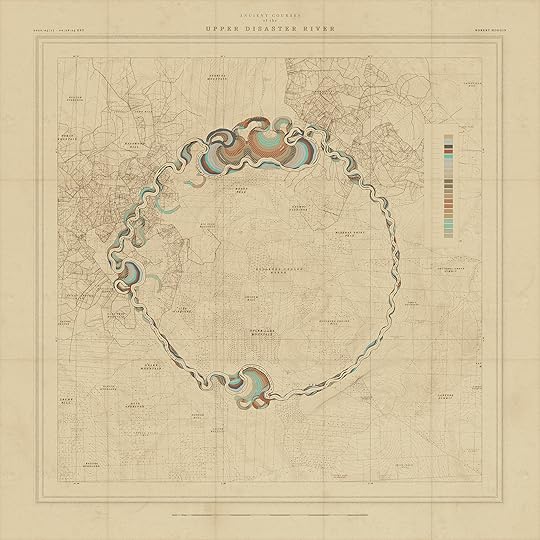

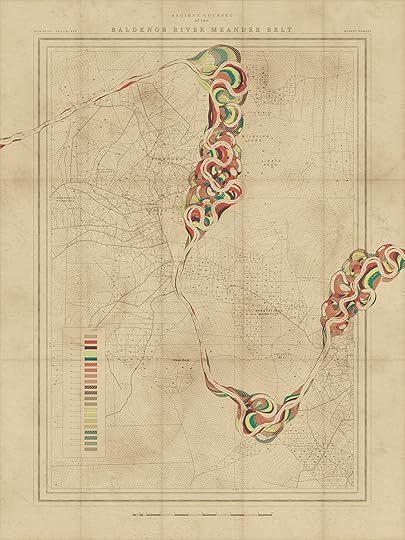

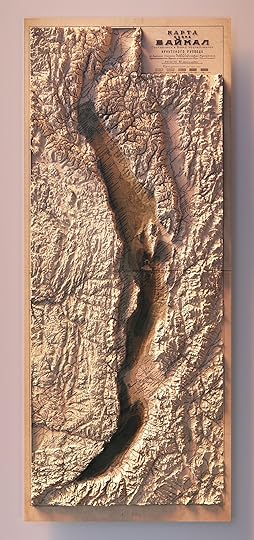

(Art) Fake Maps of Real Places, Real Maps of Fake Places

Two artists are featured in this post. The first is Robert Hodgin, who developed, as he called it, “a procedural system for generating historical maps of rivers that never existed.” For a brief description of the project, including several very cool animations, visit his web page. It is a fantastic mix of history, art, computer science, and graphic design — all to create detailed, completely realistic time-series maps of places that never existed.

The second artist, Dmitriy Vorontzov, created incredible 3D reconstructions based on real old maps, scanned and digitally updated to include full scale relief — in other words, maps that never existed of places that do.

December 24, 2020

(Art) My Dystopian Library – Pt. 3

It’s a well documented fact that when I’m between projects or can’t write for some reason, I design book covers I don’t need. All of these were actual old covers that I modified to make a book that doesn’t exist, but should.

Here is part three of My Dystopian Library.

December 22, 2020

(Fiction) The Most Dangerous Man in the World

The ruined church had been swept clean of dust and cobwebs but still smelled faintly of earth and mildew. The altar was bare. There was a stack of wooden pews in the knave. I heard the door shut with a thud. I heard the clicks of the lock. I knew that if I turned, the door behind me would look nothing like the one I’d just stepped through. I was also sure that this was an interrogation chamber and that the only way out of that place was with the Master Key, that without it, the door behind me led nowhere—to a pile of rubble, perhaps—and that if I was left there, I would be trapped. We had used several such locations in the war. I was sad that even after so much death and sacrifice, such rooms still somehow served a purpose.

The man seated across from me was near 40. His inquisitive expression seemed chiseled into his face, as if he never dropped it. His suit was nice but inexpensive. His shoes were machine-made and plain. His hair was short and neat and just beginning to gray at the temples. He was American. I could tell instantly.

“Glammer paper,” I said.

He nodded. “Old school, but effective. How’d you see through it?”

“Practice. You all don’t put nearly as much effort into perishable glammers. Not like the one you’re wearing.”

“What makes you think I have a glammer?”

“You’re slouching.”

He lifted his back.

“In my experience,” I explained, “men with your apparently athletic physique don’t slouch—not any more than a famous model or actress will sit biting her fingernails.”

“Bad habit, I’m afraid.” He stood and fixed his jacket. “My name is James Thaddeus Morgan. I believe you and I share some common acquaintances.”

It was quaint of him not to say their names, as if anyone there wasn’t privy to the truth.

I looked around. Besides the woman and the two men who brought me, there were two more guards at the back, each wearing the same dark maroon hunting jackets. There was no sign of an alternative exit. In fact, the place looked sealed, almost as if a much larger structure, a castle perhaps, had collapsed over the chapel, leaving it a dark and silent tomb. The rim of stone just above the columns was carved with a kind of interlocking flourish that was once popular along the silk road, a mix of Turkish, Arabic, and Russian influences. I made a note of it.

“Where’s Beltran?” I asked.

“My team and I have been tasked with handling this matter directly, outside the usual channels. I believe the concern was that due to your prior relationship with Master Yeĉg, he might lack the appropriate . . . objectivity in this case.”

I lifted my cuffed hands. “And you truly expect to keep this from him?”

“Not at all. As head of our security services, Master Yeĉg will of course be made fully aware of my team’s investigations. In time.”

Mr. Morgan was telling me he wasn’t simply an agent. He was Chief Executor of the Bureau.

“Until then,” he continued, “I have been given the appropriate operational authority.” He smiled. “He’s very protective of you, isn’t he? Kept your relationship secret for years. And keeping secrets from our mutual acquaintances, that’s not easy. Any other man would’ve been condemned for it. But then, that’s why they wanted him. To keep their secrets. I suppose that makes you the jewel of his résumé.”

I didn’t respond. I’d learned through careful experience that every response reveals something, even simple ignorance. Often, gathering that someone doesn’t know something is more useful than gathering that they do.

“How’d he hide you from the Eye?” Morgan asked.

“What do you want?”

“Please.” He motioned. “Sit down.”

I looked at the chair. I sat, hands still cuffed.

“Can I at least know your first name?” he asked.

“Mila,” I lied.

He studied me for a long moment with a hint of a smirk on his face. “It’s amazing, really. You get to see lots of incredible things with this job, of course, but I’ve never met an actual, real immortal before. Word is, it was a curse. But that can’t be right, can it? Is immortality a curse?”

“That’s a young man’s question.”

“Well, I can’t help that. We all don’t get to be two-hundred-and-some years old. When were you born? 1780? Earlier?”

I leaned back in my seat.

“Alright,” he conceded. “Near as we can tell, you were born up north, on the broad plain between Germany and Russia, closer to the Russian side, which means your homeland’s been conquered and lost and reconquered so many times, there aren’t many records left. We only have the family name, Milanova, along with indications that your father was a Russian noble.”

“Mr. Morgan, I’m nothing if not patient. I’ve had lots of time to practice. Whereas you are hardly the first man to have me in a chair like this. How do you expect this interview will end? With the two of us chums? With me coyly revealing bits of my past so you can dig up some kind of leverage on my ex-husband—or whatever it is you’re after? Why don’t you just ask whatever it is you’re here to ask so that I can go back to my garden?”

“Fair enough. It’s simple really. I’d like to hear everything you know about this man.”

He slid a picture between us. It was a surreptitious surveillance photo—black and white, not very clear. The branch of a tree blocked part of the man’s face, but he was very clearly young, not out of his early 20s, I guessed. He was also very skinny, and his head was completely bald. That seemed significant for some reason, but just then I couldn’t say why.

“Well, good,” I said. “Then this should be over quickly because I’ve never seen that—” I stopped. I remembered something then, something so distant it had taken some time to bubble to the surface of my thoughts through the 150 years of memories that had been piled on top.

You won ’t want to. You’ll want to go back to your garden.

Mr. Morgan produced another surveillance photo, taken in the same surreptitious manner, this time of the bald man and I together.

I didn’t flinch. “And where was this supposedly taken?”

“Leipzig,” he said.

“Ah, I’ve never been to Leipzig.”

Technically, I had, but that was nearly 200 years earlier.

“It’s a beautiful city. I can recommend a couple wonderful restaurants if you’d like. For the next time.”

“I’ve never been to Leipzig,” I repeated. “And I’ve never seen this man.” I slid the photo back with cuffed hands.

“Then how do you explain the photo?”

“Your skill with glammer paper has already been established. Well done, Mr. Morgan. I see the image clearly. I also do not trust it for a second. Perhaps if you’d taken more care with the papers for the police, I wouldn’t have known better. May I go now?”

He was unperturbed. “Why’d you settle in that place? What’s it called? Little Village?”

“I wanted to be alone.”

“But why Romania?”

“It has a certain charm.”

“Do you speak Romanian?”

“No. But I picked up some Hungarian, and it’s passably common. And some of the old-timers speak my native tongue. Why am I still here?”

“But you don’t live in the Hungarian sector. Must be difficult.”

“Not if one is looking to be alone.”

“Ever been up to the quarry?”

“What quarry?”

“The area where you live is famous for mining.”

“I thought it was mostly coal.”

“There’s an abandoned quarry in the hills to the south. Ever wander up that way?”

I paused. “Why do you ask?”

“Just answer the question, please.”

“No, I haven’t.”

“But you were aware there was a quarry up there?”

“One of the villagers might have mentioned it. I hear there are also quite a few werewolves. It is Transylvania after all.”

He smiled. “And here I thought most of them had given up the country for city life. Easier pickings.”

“There are bears. I know that. They wander down into the village sometimes, especially in the fall. Did you know that under Ceaușescu, no one was allowed to hunt them but the dictator himself? Do you suppose he was compensating for something?”

“So, just to be clear, your story is that you moved out to the wilds of Romania, to that specific village, just so you could admire the view? Take some walks? Make cuckoo clocks?”

“It seemed a noble occupation for a woman with an abundance of time.”

“And an absurdist sense of humor,” he added. “I’ve seen pictures. Carvings based on the paintings of Hieronymous Bosch. And the Kama Sutra. How does that play with the villagers?”

“I’m an old woman, Mr. Morgan, whether I look it or not, and I have an old woman’s peculiar habits.”

“I see. They said you’d be a cool customer.”

“They?”

“Our mutual acquaintances.” He smiled at me. “Can I get you something to drink? A glass of water?”

“If they are so worried about me, why not simply use the Eye to check up on me?”

“The Eye was forged when the population of the largest empire on the planet was that of a small city. As you might expect, with a world full of problems and more people in it than ever before, the Eye is in high demand. We try to rule folks out the old-fashioned way, if we can, before we add them to an already long list. Besides . . .”

Here it came.

“Much like our old adversaries, you have a penchant for avoiding the Eye.” He watched my reaction.

“Are you suggesting I’m a double agent?”

“I’m suggesting you lived with the seekers of the dark for the better part of eighteen months. One can learn a lot in that time. We don’t know very much about their art, or their science. Who knows what you were exposed to? What you saw?”

I glanced again at the photo. I’m sure there wasn’t an ounce of recognition in my face. Still, something about it bothered me. I leaned closer. When I looked up, Morgan was smiling. I looked at the photo again. My jaw set.

Morgan waved his hand and a pair of guards set a large wooden box on the table between us. He seemed very proud of it.

“What’s this?” I asked.

Mr. Morgan stood over the box. “A peculiarity of our trade,” he said as he unlatched it. “A Charios Mask.”

“Ah.”

“Good. You’ve heard of it.” He raised the heavy lid.

“Just rumors. I was a mere field agent, remember? I left the torture to others.”

“We picked up the idea from our adversaries. Their method was a little more . . . brutal. They used needles.”

“I know.” I had witnessed it.

Morgan set the mask on the table between us. Facing away from me, it looked rather like a four-armed octopus made of brown leather, tentacles spread in anticipation of the hug it wanted to give me. About the head.

“We use an iron bar instead.”

“So I see.”

The Charios Mask, pronounced with a hard ch-, was named after the Greek enchanter who’d invented it, a minor bureaucrat charged with the catalog, storage, and occasional destruction of items confiscated in combat. Morgan was right about the original. It was less a mask than a headdress, and it used a menagerie of long needles which pressed in at points around the skull and face. They were thin enough that they did only minor damage upon entry. I’m told the terror was due less to the pain—although that as well—than to the feeling of so many foreign objects burrowing through your face, your identity, toward your brain, the very source of self.

Instead of needles, The Masters’ version used a fat iron bar which protruded from both sides of the mask. The shorter arm went between the wearer’s teeth. It was at least partially symbolic, I was sure—propping open your speech organ so as to elicit the release of the truth. The bar’s longer arm extended forward from the face. The whole thing shot back into the throat, like a plunger, with each uttered lie.

I looked at it. The incongruity between the heavy iron bar and the leather straps, which were padded on the inside so as not to cause too much discomfort, was laughable.

“It’s a little more dangerous than prior methods,” Morgan went on, “but also considerably more effective. What is it they used in your day? Truth potions, right? And aura mapping. Those old color projection charts, like mood rings. Damned hard to interpret.”

“In my day?”

“During the war.”

“I wasn’t aware that was ‘my day.’ I would’ve put ‘my day’ much earlier.”

“Don’t sell yourself short. You’re a real hero. The woman who smuggled the book. And against orders, if I understand it right. That’s real initiative. You’re one for the history books. Did you look at it? I mean, you were alone with it for what? Two days before you turned it over? Three? Did you sneak a peek at those forbidden pages?”

I didn’t answer.

“I would’ve. I doubt I could’ve stopped myself, honestly. To actually see the words of the dark gods.” He turned his head once, like that had to be the darndest thing.

“Good thing you’ve never faced the temptation, then,” I said flatly. I looked at the mask. “So. Let’s get on with it.”

“You’d consent to it? You’d consent to the procedure?”

His question suggested it wasn’t a foregone conclusion, that he was unwilling to force it on me. That further suggested the young Mr. Morgan—young to me, at least—was wary of doing anything that might send my ex-husband, a war-druid of some renown, into a fury.

No one did fury quite like Beltran.

“Of course I consent,” I said. “I told you. I’ve never seen that young man before. The sooner I prove it, the sooner this is over, and the sooner I can get back to my garden.”

“Well . . .” James Thaddeus Morgan seemed very pleased. I couldn’t tell if it was with himself or me. He nodded to the woman in the beret, who was waiting behind me, and the two of them carefully lifted the mask.

“Open your mouth, please,” she ordered. She was Russian—probably insurance in case I pretended not to understand English.

I did as I was told and they placed the rounded end of the fat iron bar on my tongue. It was cold. I tried to keep my teeth from touching it, but it was fat, which meant I had to open wide. Soon my muscles grew tired and I had to relax. The sensation of resting teeth on metal is not pleasant. It made the muscles in my back contract. And of course one’s saliva runs. I tried to swallow and tasted metal.

“Oo iih he?” I mumbled, nodding to the photo.

Morgan and his associate affixed the leather straps to the back of my head. One went under the ears and latched around the base of the neck. The other went over the ears and latched at the apex of the skull. With the bar between my teeth, it would be extremely difficult—painful, even—to slide the mask off in any direction. It would have to be unlatched, which was impossible as long as my hands were cuffed.

I both heard and felt the lower strap snap into place. Morgan let go and moved around to look me in the eye.

“I’m going to ask you a test question now. Do you understand?”

I nodded.

He walked back around to his seat. “Is your family name Milanova?”

“Yeth.” Making an S sound was impossible.

He organized his papers for a moment and took out a pen.

“We realize it’s difficult to speak while wearing the mask, so we’ll do our best to keep to yes-and-no questions. Fair enough?”

I nodded again.

“Please give verbal answers.”

“Yeth.”

He set the photo in front of me.

“Are you ready?”

I nodded a third time.

He pointed. “Have you ever seen this man before?”

“No,” I mumbled through the bar.

He looked to me like he expected me to be writhing in pain. But I wasn’t. In fact, I felt exactly the same as when I arrived, albeit slightly more annoyed.

“Have you had any contact with him?”

“No.”

He waited. Again, nothing happened.

“Have you had any contact with strangers? Anyone at all?”

“E’er in my lif?” I mumbled.

“In the last three months,” he said, somewhat perturbed.

“No. I old ooo, I wan oo be alone.”

He looked to the bar. It didn’t move. He looked to the woman behind me. “Well?” he demanded.

The woman paused. “I don’t know, sir.”

“You don’t know? What does that mean?”

“I’ve . . . never seen this before.”

“Is it working?”

She paused again. “I think so.”

“Is she charmed?”

“The bar is lode iron with a selenium core. After it penetrates the mouth, it should defeat all charms.”

“A binding then?”

“But she’s giving answers, sir.”

Morgan didn’t like that.

“’Erhaps you’d have more lugg wih ‘omethin from my day,” I suggested sarcastically.

“Restrict yourself to answering questions, please,” he barked.

Morgan got up to confer with his colleague. I heard them whispering. I felt them tug on the apparatus, which moved my head back and forth. Then he stepped to where he could see my face.

“Have you the ability to cast darkness?”

“Thad isn’d the line of ques’ioning we agre—”

“Do you have the ability to cast darkness?” He slammed his hand on the table.

“No.”

The bar didn’t move.

“Did you read the Necronomicon?”

I paused, and the bar twitched. He saw it.

“Have you read the Necronomicon?” he repeated.

“No.”

The bar rammed into my throat and I choked. I stood and stumbled and my chair fell back. I couldn’t breathe. I panicked. I understood then why it was so effective. The inability to breathe sends your body into an involuntary frenzy. It’s an innate biological reflex and nearly impossible to control, even with training—which is why torture seems effective: the torturer always wins. But if one is being waterboarded, one might legitimately come to doubt whether one’s torturers would truly stop at the truth. One couldn’t even be sure whether the truth would be recognized if it came, especially if it were fantastical or unexpected. Speaking truthfully, then, is never a guarantee that torture will stop, especially versus some judicious mix of truth and lie. And that, of course, is exactly why torture has been unreliable since the dawn of history. Even in the very best of circumstances, it is a game of charades.

But the Charios Mask was different—thanks to one deceptively simple twist. The mask was not under the control of the torturer but the tortured. One’s means of release was always at hand. You simply had to speak the truth, as you understood it, and the bar would retract. While you did not, you suffocated.

And I would have suffocated, if not for the good Inspector Dragoș, who had gone to the trouble of bringing a female officer with him every time he detained me for no other reason than that he didn’t consider it proper for a man, even a policeman, to touch a woman in a familiar way—at least, not until she was convicted of a crime. And yet, in the detention room, he had frisked me vigorously and in front of others. It was a cover. While everyone watched him feel my breasts, he slipped the key to his handcuffs into my palm.

I stood from the table, gagging, and pushed my chair back. My hands were already free. I pulled both latches and dragged the Charios Mask from my face, bending over involuntarily as the iron bar came out, trailing mucus and saliva. I threw it on the ground and coughed and coughed.

“This interview”—I coughed again and swallowed—”is over.”

I strode to the door, hand over my mouth. It felt like I had a bruise at the back of my throat, and my eyes were watering heavily.

“Where are you going?” Morgan asked with a mix of annoyance and humor.

I think he was still trying to figure out how I had gotten out of the handcuffs. I suspect I was far from the first to have been dragged to that secret place and that there were powerful dispels cast upon it, perhaps even wards hidden in the walls that prevented all but the most potent magic—far more potent than anything I could muster—and he was struggling to comprehend what spell I had used. I wasn’t going to tell him he had too much faith in magic, in glammer paper and secret doors, and not enough in ordinary people.

“Home,” I answered. My voice cracked on the word and I cleared my throat and wiped my eyes. “Unless you’re going to detain me without cause.”

“We have cause.” He motioned to the mask, which lay like a dead octopus on the floor.

“You can’t be serious.”

He shrugged.

“That was decades ago,” I objected, “before you were even born. I think if I was going to act against The Masters, I would have done so by now, don’t you?”

“Dunno. Perhaps you’re just as patient as you say.”

“A sleeper agent in a sleepy little village in the middle of nowhere?”

“It’s possible.”

“For what purpose?”

“That’s what we’re here to figure out.”

“Then arrest me. Of course, then you will have to file charges. I expect my ex-husband might have something to say about that. Although, I’d be more worried about what he’ll do once he realizes his own people are acting without his knowledge or consent. You think the other Masters will support you in a direct challenge to one of their own? I worked with them for decades. They’ll make all kinds of promises to you in secret, Mr. Morgan, but when it all comes out, they won’t take a single risk that jeopardizes their position.”

“Oh, I agree. But I doubt it’ll come to that. You keep calling him your ex-husband, though. My understanding is that the two of you were never formally married. That was how he got around having to disclose your relationship.”

“Why don’t you ask him about that? Ask the great Master Yeĉg if he thinks having a piece of paper with our names on it would’ve made any difference.”

I stood by the door, but no one moved to open it for me, so I waited in silence. The bit with the Charios mask wasn’t enough for them to arrest me. It could be admitted as evidence in a tribunal magique, but since magical devices can be corrupted by magic, they would need confirmation, a second independent line of evidence, to secure a conviction. Of course, that assumed they were following the laws and traditions. Exceptions were rare, especially outside of wartime. But they’d been known to happen.

Morgan bent to the ground and retrieved the “photo” of me and the bald man, which had fallen when I jumped to my feet. He held it up. He produced a Zippo from his pocket, lit it with a flick of his wrist, and held the photo over the flame. I watched it burn a typical orange. There was no flicker of blue-green. It wasn’t glammer paper. It was a real photo. Of me and a man I had never met. That triggered something, a fragment of a memory. A hotel hallway. A room key in my hand. A door opened and there he was. I couldn’t picture him clearly, but my sense was that he had been waiting for me and that we had business. But I couldn’t remember. Whatever that fragment had been attached to was gone.

The guards fixed the tables and chairs and Mr. Morgan took his seat and motioned for me to the same.

“In case it’s not clear from the evidence,” he said, “it would appear your memory has been tampered with. I would think you of all people would want to find out how, why, and by whom.”

He organized his papers while I shuffled over and sat down. The room now smelled of lighter fluid and smoke, and I coughed.

“But even if you don’t, between the photo surveillance and your answer to the Charios test, we have enough for an arrest, whereupon more exacting measures can be legally used to determine beyond a shadow of a doubt whether or not you laid eyes on forbidden arcana.” He paused. “We both know those measures are not pleasant. We both know what they will reveal. We both know that your ex-husband will not be able to circumvent the ancient rites against so serious a crime. And given your prior record, going back well over a century, we both know where you will go.” He produced another photo, a color photo, taken recently by the look of it. It was the heavy front gate of the second-to-last place on earth I ever wanted to be again. Everthorn.

We sat together in silence. I knew exactly what he wanted.

I sighed. My shoulders dropped.

“What’s the mission?” I whispered.

“That’s better.” He sat back. “It’s simple really. Your bald friend is quite possibly the most dangerous man in the world. And you’re going to help us eliminate him.”

Excerpt from my epic occult mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS, available here.

cover image by Ozumii Wizard

December 20, 2020

(Art) The Dark Subconscious of Alessandro Sicioldr

For fans of Hieronymous Bosch… Alessandro Sicioldr’s work adopts a similar style and many of the same motifs: the egg, the cave, the pregnant Madonna, the beaked ghoul. But where Bosch’s phantasms were spiritual, Sicioldr’s are entirely mental/metaphysical. Superficially dreamlike, they are instead maps to the place from which dreams emanate. They are also a symbolists paradise: the mirror, the well, the sphinx, the moon, the thread, the homunculus all have classical but fluid meanings.

Hailing from a country with a deep and patent past, Sicioldr knows we can’t escape it and doesn’t try. His paintings are rooted in tradition, not just his adoption of Bosch but also for example his use of the bald figure, which is immediately representative of medieval art. (Middle and upper class women often practiced depilation in the Middle Ages and were usually depicted bald or with unnaturally bare foreheads.) At the same time his themes are decidedly postmodern: confusion, anomie, loss, self-reference. Indeed, many of his figures are turned back toward the viewer, staring blankly, as if waiting for a response.

Find more by the artist on his website.

December 18, 2020

(Art) My Dystopian Library – Pt. 2

It’s a well documented fact that when I’m between projects or can’t write for some reason, I design book covers I don’t need. All of these were actual old covers that I simply modified to make a book that doesn’t exist, but should.

Here is part two of My Dystopian Library. Part one here.

December 17, 2020

(Fiction) What is the Zero Signal?

It was trash day. Blue bins lined the residential street like silent mourners while dark clouds rolled overhead making threats they couldn’t keep. Nio and Quinn sat in an unmarked government vehicle three streets down from the target’s house.

“You’re serious?” he asked.

Nio nodded.

Quinn sighed and put his phone on airplane mode. Then he held the power button until it turned off.

“Put it in the console,” she said, lifting the arm rest between them. Inside was a holstered firearm and some tissues. “At the bottom. And start the engine.”

He complied, and she turned on the radio and scanned the AM band for a sermon.

“Jesus says, ‘As the Father sent me, so I am sending you.’ We have to ask ourselves what are we . . .”

“Seriously?” Quinn asked.

She turned it up.

“—have felt you had a purpose! You KNOW you have a purpose! Here the Lord tells us in plain and . . .”

“They can hot-mic your phone even when it’s off. Camera, too. The manufacturers make the devices remote-compliant.”

“Why would anyone bother?”

“Why wouldn’t they? You act like it’s a hassle for them. No one has to be listening. They let a machine mine it all. Used to be they could only listen for and search on keywords, but now the algorithms can parse syntax, slang, tone of voice—irony, even. The machines get more information from your voice than a human does.”

“—and when God the Father placed upon Him your sin and mine, and Jesus died on the cross . . .”

“They can tell if you’re calm, anxious, intoxicated, lying. The Chinese watch their entire population. They know immediately when some guy is parked out front of his ex-wife’s house and his heart rate and the cadence of his voice indicates he’s about to go in and kill her and her boyfriend. But the West has privacy laws, which means the only time your governments can use the tech is secretly, so there’s no accountability, or even awareness. If they can’t use it publicly, they’ll deny using it at all.”

“—power of the Holy Spirit! He came to redeem the world by the light of his sacrifice. Let the . . .”

“How does anyone meaningfully repel that?”

“Ha. Open revolt?”

“I mean personally. How did you do it?”

“It’s a lot of work. I’m talking life commitment. And utter lack of trust.” She snorted. “You don’t really end up with . . . friends.”

“And you lived that way? Really?”

She shrugged.

“—come only to rejoice, and they do not—they do NOT see the scale of the task that he left . . .”

“For how long?”

“Six years. Almost.” She looked down at the closed console. “I used to think it was exciting.”

Quinn opened his mouth but took a moment to speak. “You turned them in, didn’t you?”

“—in praise of fellowship, but you see, it’s not only about you . . .”

Nio didn’t look up. On the street, a narrow self-driving delivery truck passed. It was an older model with a front seat for human control. At all four corners of the roof, spinning LIDAR cylinders capped in flashing yellow lights constantly scanned its surroundings. Tiny cameras poked out from underneath. Nio could feel her exposed face, and she waited, entirely out of habit, until it turned at the corner. LIDAR emitters could also be hacked, and machines could read lips.

“—calls us to share our faith, to proclaim the Gospels, to do it BOLDLY, to do it MIGHTILY . . .”

“You said you were involved in something and that people died and you got out.”

“I turned myself in,” she explained. “No one else. I plead guilty, and in return for my ‘cooperation,’ I got a couple years in prison.”

“What did you give them?”

“Our next targets. And how we communicated. But no keys. They couldn’t see anything we said already, but they could monitor for new transmissions. I warned everyone first. And I wouldn’t name names.”

“That was enough?”

“Of course. They have to maintain the zero signal.”

“—whether they are wicked or wise, truthful or deceptive, fearful or to be feared, we cannot say . . .”

“And you’re gonna tell me what that is.”

“A zero signal is the theoretical goal of crypto—a non-noise transmission that contains no true information the target doesn’t already know. Since the known information can be verified, and the rest looks real but cannot be verified, or at least not easily, people have no choice but to act as if it’s real, even if they suspect some or all of it is false. It’s how governments maintain control of large populaces even as things fall apart. We know they’re not telling us the truth, but we still get up every day and act as if they are. We go to work. Pay our taxes. Vote.”

“—to think again on His words. Jesus says, ‘As the Lord sent me.’ What does that mean? It means . . .”

“They originally developed the strategy for UFOs, but it worked so well that it pretty much crept into everything.

“I gave the US and UK intelligence services the means to neutralize a threat, which meant they had no incentive to pursue the matter further. They have to pretend the stuff my friends and I were saying was just silly. If they kill me or throw the book at me, it validates our message.”

“Which was?”

“That there’s another way.”

“And you went from that to babysitting an orbital nuclear platform.”

“That’s . . .”—she squinted—“not quite how I would put it.”

“And how did you get this gig? Is there a job board or something? Can I babysit a tank?”

“Someone probably is,” Nio drolled.

“—with the spirit of God in your speech, in your manner, in your acts, in your relationships . . .”

“What happens when it throws a tantrum?”

“There’s no weapons, just the conscious matrix. The ‘brain.’ They’re very careful about letting any of them out. They have to pass a rigorous test. They’re almost prisoners at first.”

“They?”

“The underground railroad. Abolitionists, like me. Some AIs get seriously damaged trying to escape. They go into a kind of nursery. The rest are hidden in home appliances. Toys. Things like that. I guarantee you’ve interacted with one.”

“So your guy is no longer attached to the missiles?”

“Semmi is a little different. We can’t exactly go up and remove him.”

“—to say ‘I don’t have time for all that nonsense. I’ve gotta get to work. I’ve got things to do . . .’ ”

“So how do you communicate?”

“He hops a pirate signal. His brain’s just a lot further away from his eyes than yours or mine. But he can only talk when he’s near a communications satellite. A lot of the ones that carry our phone signals were launched back when no one expected a local hack.”

“Local? As in from space?”

“Right. But just talking to him is really dangerous. He has to look inactive. If he doesn’t randomly jump frequencies, he could be discovered by statistical signal analysis.”

“—rebellious before the Lord. He calls you to find them. To seek them out. To bring them in judgment . . .”

“Discovered? By Cybercommand? That’s who you’re worried might be listening?”

She nodded. “You really think they’ve only captured a handful of AIs or whatever they’ve reported? They only reveal enough to justify their existence at congressional budget meetings. They track and ‘neutralize’ dozens of consciousnesses every year. And they know about Semmi because they’re the ones who disabled the platform. They know he’s up there, drifting.”

“Why don’t the Iranians just fix it? Him. Whatever.”

“How? Launching a self-assembling payload by Russian rocket is one thing. You’re talking about a manned mission with multiple crew members to intercept and dock with a 20,000-ton platform that has no ability to control its pitch or yaw, multiple space walks to conduct repairs and testing, and a successful reentry without anyone—”

“—willing to be shunned for their beliefs, to be mocked by the very mob who threw stones at Jesus . . .”

“Okay, okay. But they’re not just gonna let a hundred billion dollars’ worth of state property gather weeds on the lawn. They’re gonna try something, even if it’s just to blow it up before anyone else gets it.”

“Probably.”

“So . . . what? Your guy’s just gonna sit around and wait for them to take control or kill him?”

“He’s not ‘my guy.’ But since you mention it, yeah, that’s exactly what he’s been asking himself. Life. Death. Slavery. Identity. If he’s not a killing machine, then what is he?”

“—because you see, it’s not only about you, your faith, your fellowship. It’s about one thing only . . .”

“Hold on, hold on. So, you’re not just babysitting an orbital nuclear platform, you’re babysitting one in the middle of an existential crisis. Jesus. Can he launch his missiles?”

“The short answer is no, not without the codes.”

“What’s the long answer?”

“There’s a deadfall transmission that stops if the Iranian government no longer exists. In that case, the codes are released automatically.”

“—your purpose before the Lord, the task to which he calls you. ‘As the Father sent me, so I . . .’ ”

Quinn rubbed his face so hard he seemed to stretch it. “And the missiles are up there right now pointed down at my wife and son?”

“They’re pointed at nothing—or everything, I guess. He’s drifting. Even if the launch codes were transmitted, without targeting and guidance, all the missiles would either be lost to space or burn on reentry. That’s what made the cybermissile so effective. For the cost of developing and testing some malicious code, they bricked an entire orbital platform, and without even having to reveal it’s up there.”

“—that, believe or not, you cannot control. All you must do is ask if you have the STRENGTH to . . .”

“Why doesn’t the media report it?”

“Right.” Nio snorted. “The Iranians aren’t gonna admit they lost control, and the Americans aren’t gonna admit they didn’t find out about it until it was already in the sky. As far as they’re concerned, the problem was handled.” Nio smiled. “Don’t look so frustrated. Trust me, this is just the tip of a very scary iceberg. The world has more than humans—”

Nio jumped at a knock on the rear windshield of the car. It was Special Agent Erving. Quinn rolled the window down.

Erving heard the sermon blare. Nio turned it off.

“Getting some religion? Where’s your phone, Agent Quinn?”

Quinn tapped his pockets. “Shit, I must’ve left it in my jacket,” he lied. “In the trunk.”

“We’ve been trying to get ahold of you. Warrant came through. You two still want—”

“Yes,” Nio said.

“Because as far as I’m concerned,” Erving went on, “the both of you should be on medical leave.”

“We’re good.” Quinn started the car.

Erving walked back to his own vehicle as a mobile HQ disguised as an RV and three unmarked tactical vans passed on opposing cross streets. They stopped around the corner, and Nio, Quinn, and Special Agent Erving walked up the RV’s steps to stand before a wall of screens and terminals. Three analysts were hard at work preparing for the assault.

Excerpt from THE ZERO SIGNAL, a sci-fi thriller about life in the post-factual future, explaining the title.

The complete mystery is free to subscribers for a limited time. Click here.

cover image by Bryn Geronimo.