Rick Wayne's Blog, page 12

November 6, 2020

(Fiction) This is kidnapping, you know that right?

I tripped hard that night. I don’t remember all of it. Supposedly, I freaked out at some point and told everyone death was stalking me, that it was coming, that I could feel it. I started hyperventilating and Shanna cleared the room and that was it. Party over, oops, out of time.

The next morning, I woke around noon to find a strange man standing over me. Considering the events of the night before, this didn’t immediately surprise—not until I saw how he was dressed.

I shrieked and fell backward to the floor between the couch and the wall, claws up, ready to scratch his eyes out. But he just stood there, hands at the sides of his black suit, while his companion, a tall, thin black man with narrow sideburns, checked my closet and the bathroom.

“Clean,” he said, knocking over a beer bottle with his foot.

The man in the suit had a bulbous metal object in his hand, like a vajra or two-sided scepter. He slipped it into a holster under his blazer—a holster for a spiritual object. He bent to pick up one of the empty boxes of cordials from the floor. He counted the others among the empty beer bottles and trash around the room. My place was a disaster.

“. . . three . . . four . . . five.” He looked at me.

“I got hungry,” I said.

He tossed the box in the trash. His cheeks were pockmarked and his hair was heavily pomaded. He looked like door security for a pay-by-the-bottle club in Midtown. He even had the requisite merino turtleneck in place of a shirt and tie.

“Put some clothes on,” he said flatly. “Mr. Rottheim would like to see you.”

I looked down. I was in nothing but a Care Bears T-shirt and a new pair of granny panties. “Who?”

I genuinely didn’t know, but bouncer-man didn’t care.

“Let’s go.” He snapped.

“And what happens if I tell this guy to go fuck himself?” I asked.

“Trust me.” He picked up my jeans from the floor and tossed them to me. “It’s in your best interest to come.”

“Is that a threat?”

I slipped them on and went to pee. I closed the door but the man in the turtleneck blocked it.

“You wanna watch?” I asked.

He stood in a wide stance with his arms crossed.

“Fine.”

I peed and washed my hands and face and put my hair back.

“’Iss is ’idnappin,” I said, gargling. I spit. “You know that, right?”

“I’ll take you to the police after,” he drolled.

I swiped my mirrored aviators off the giant stuffed bunny in the living room and was ushered out the door. Sideburns stood guard on the sidewalk like I was a celebrity exiting a show. The stretched limo waiting at the curb took us uptown. There was a large touchscreen panel in the center that controlled the temperature and the music and the WiFi and the privacy window and everything, and all the seats in the back had their own foldout screens, like on an airplane. Sideburns drove. Bouncerman sat in the back across from me and watched me, expressionless, the entire way.

“You got any gum?” I asked. I still had a terrible taste in my mouth.

We stopped in front of an old stone-block mansion, not far from Maleficium. I looked up at it from the window. It was more tall than wide and wedged carefully between a pair of brick condo towers. Bouncer-man opened the door for me before walking to the front of the mansion. The limo pulled away, leaving me alone on the sidewalk with a bald pedestrian. He was watching the mansion like the roof was on fire. So I did the same.

The block stone of the building’s first three floors had dark runoff stains at the edges of the gutters that spoke to old age. A huge bay window rose from the second and third floors, suggesting there was a single tall space behind, like a ballroom or long dining hall. The very top floor was a later addition. The front of it was all windows, tinted and impenetrable.

“What are we looking at?” I asked.

The bald man turned to me then with a curious gaze, like he was utterly amazed I was even aware of his presence. That was when I noticed his coat.

A coat. In June.

Still, I can see why he was so fond of it. It was awesome. It was an old-style chuban, like they used to wear on the mainland centuries ago, only the buttons had been replaced. Each was different. One was stamped metal. Another was polished amber. Whatever had been printed on the fabric had long-since faded to wisps. Now it appeared as an early morning fog, or maybe smoke from a campfire. The man who wore it had skin of an odd color. It had a faint ocher hue.

“Dig the coat,” I said.

“Ms. Song,” Bouncerman urged me from the front door.

“Song,” the bald man said, as if both perplexed by my name and committing it to memory.

He didn’t move as I walked in the front, and I returned his gaze from the foyer until Bouncerman closed the door behind me.

“You know that guy?” I asked.

“Mr. Rottheim makes a lot of enemies,” he said, urging me toward an open elevator.

“An elevator in a house,” I said. “Huh. Will wonders never cease.”

It was narrow but elegant. By the buttons, the house had four floors and a basement. We rode to the very top, which had a mid-century, Frank-Lloyd-Wright-y feel. The stairs descending to my left were simple planks that jutted from the wall with open air between. The railing was solid glass. There was a waterfall in a nook and a library-office straight ahead, which is where I was directed.

I stepped into the room. I was alone.

“Wait here,” Bouncerman said.

A huge formal desk presided over the space, which included a full-sized boardroom table, complete with teleconferencing kid. The screen saver, a Finnish flag, bounced slowly across the TV. Between them, a couch faced matching upholstered chairs. Behind the desk hung a five-foot-tall portrait of a young man with brown curls standing before a bleak wall of chiseled rock. He rested an arm on it the way you might lean against a fireplace mantle. Everything smelled like new carpet—nice new carpet.

But it was the wall of glass that got you. The view was killer. I looked down to the sidewalk, but the bald man was gone.

The other three walls were paneled in well-oiled oak. Spaced evenly along the panels were ornately framed pages from old manuscripts. I browsed as I waited, leaning over the antique occasional furniture to squint at the once-dark scratch, which was so old it had faded to pale brown. I was studying a very large parchment, the size of a small poster, when Mr. Rottheim rolled in. Or at least I assumed it was him. It was the same man as in the painting, only thinner and sicklier and riding a wheelchair. He wore a loose padded house vest over a collared shirt. His feet were in leather house slippers.

“What do you think?” he asked.

He was considerably younger than I expected, which made me angry—that someone so young could have that much money.

“What do I think?” I replied. “I think you’re looking at five to ten for kidnapping.”

He nodded to the framed parchment, which was different than the others. Most of the pages had little hand-drawn diagrams, but the sheet in front of me contained a large illustration. A naked man, crudely drawn and out of proportion, stood under a gallows. The rope that had held him had snapped and part of it dangled from the wood. He held a flaming staff and there were symbols all over his body that matched those in the circle on the ground around him. Three long knives, each different than the other, poked up from the foreground.

“It’s from the eleventh century,” he explained with a little bluster. “Nearly a thousand years old.”

He had some kind of European accent, faint enough that he had probably been speaking English since he was a kid.

“Is that when the eleventh century was?”

My host pointed to the symbols. “Remind you of anything?”

I squinted. The UV-protective glass preserved the document inside but made it a little difficult to see with the glare from the big windows.

“Sort of looks like a circuit diagram.”

There were zigzags and T-junctions, all of which ended in a small circle, just like you’d see on an electrical schematic.

“People forget that modern science grew directly out of alchemy,” he explained. “Properly understood, they are the same. I’m Lykke Rottheim.”

“Louka,” I said, trying to pronounce it.

“Everyone calls me Luke.” He motioned to the pair of chairs in front of the desk. “Please have a seat.”

I hesitated. I had planned to take a stand, literally, but my host wasn’t at all what I expected. Given his condition, standing seemed rude. I sat on the couch. It was soft and I sank in comfortably.

Rottheim rolled closer and handed me a card. I recognized it. It was my plastic Duane Reade club card.

“It was in the pocket of your jeans,” he explained. Then he nodded to a wrapped parcel on a side table. “Everything has been cleaned and pressed.”

“Pressed?” I scoffed. I couldn’t help myself. Who presses jeans?

“You’re not an easy person to find,” he said with a smirk.

“Seems like your guys did alright.”

“But you’re not where the government thinks you are, are you? Do you even have a lease agreement with the Arab or is it all under the table?”

“The Arab? His name’s Abdul, thank you. And since you seem to know everything, you tell me.”

He took out his phone and read the screen. “Ce-Lei-Zi Song. Hong Kong native. Granddaughter of Wai-Ling Lau, a local restaurateur of some renown, it seems. Merit scholarship to Parsons School of Design.” He glanced to me like he was impressed.

I shrugged.

“Dropped out your second year, shortly after being arrested for assault?”

He glanced over me again. I think the idea was that I’m hardly big enough to assault anyone.

“I’m scrappy.”

“Charges were dropped. Second arrest for vandalism last year. Apparently you put a mural on the wall of a shopping center.”

“Trust me. It was an improvement.”

“Charges still pending,” he finished. He put the phone back in his vest pocket. “And of course, now breaking and entering. If one didn’t know better, one would think you were trying to get deported.”

“One does one’s best.”

“You’re here on student visa. Does ICE know you’re no longer enrolled?”

“If not, I’m sure they’ll figure it out.”

There was a moment of silence where both of us examined the other.

“I’m sure you’re wondering why you’re here,” he said finally. He took a sudden deep breath, as if it was a struggle to talk for very long. “I’m on the board of the private club you broke into the other night.”

I rolled my eyes and leaned forward to get up. “Jeez, what is it with you pe—”

“I’m dying, Ms. Song.”

It was calm and candid and I settled back down.

“Rare genetic disorder,” he explained, “which is poetic, really, considering the effort my parents put into ensuring my lineage.” He snorted softly. “I’ll see to it that the charges against you are dropped. All of them.”

“I’m not gonna dress up like a little girl or whatever Make-A-Wish fantasy—”

“It’s nothing like that!” he barked. Then he caught himself. “But as it happens, you’re not far off the mark.” He rolled to the wall of windows. “I have been living a kind of fantasy these last few months. Recently, it came to an end.”

He turned around again.

“It was with a young woman from the club. I know, I know,” he said, looking down wryly. “One ought to know better, et cetera, et cetera. But one does silly things when one is dying. One has to, to balance out all the seriousness: doctor’s visit and blood tests and long sobbing reunions with childhood friends who, not twelve months ago, couldn’t care less about you, as if they’ve only come to gloat.” He stopped. He smiled at his own bitterness. “The young woman’s name is Lily Ann Sobriecki, although she went by ‘Laïs’ at the club.” He glanced sheepishly to me. “I suppose you can guess what happened.”

“Pregnant?”

“Recently, after discovering her . . . condition, she disappeared. Left the club. No phone call. No email. I understand she’s distraught. Let’s just say we did not part on good terms. Unfortunately, while I wouldn’t quite call her a junkie, Ms. Sobrieki has a”—he paused—“vigorous recreational drug habit, which I was of course happy to fund. I would very much like to find her before she does irreparable harm to the child. I didn’t think I would ever have offspring, Ms. Song. I thought my family would die with me. Now that I do . . . Well, I can think of little else.” He paused. “Are you a religious person?”

“Not really.”

“No. Of course not. Me neither. You’ll understand the significance, then, when I say I’ve been praying at night, literally begging God to let me make it to the birth of my child.” He laughed once. “So far, He hasn’t answered. Nor do I expect Him to. But I’m honest when I tell Him there’s nothing I wouldn’t give. Nothing.”

“Look,” I said, “I’m very sorry you’re sick. And I don’t wanna be rude, at least not any more than I have to. But I’m struggling to see where any of this justifies breaking into my apartment.”

“Yes. I do apologize for that. But time is of the essence. I have nightmares of the police finding Lily in an alley somewhere, needle in her arm. That’s not a figure of speech. I awoke just this morning—” He stopped when he saw me getting restless. “But of course. The point. I will pay you one million dollars to find her.”

I sat up. “What?”

“I will deduct ten thousand dollars from that million every hour she is not found.”

“Wait. Did you say a million dollars?”

He nodded solemnly. “Technically, I think we’re down to $960,000 as of this morning, but close enough.”

“Down?” I squinted. “Who’s down?”

“I’ve already made the same offer to several private detectives. The police, of course, are none too interested since no crime has been committed.”

“Okay, I think maybe there’s been a misunderstanding. I’m not a private detective. You just said it: I’m an art school dropout squatting above a halal market.”

“The men I hired are all very good at their jobs, Ms. Song. You know the type—ex-police, ex-military. Very experienced. Very efficient. Very professional. I feel I’ve motivated them as well as I can. They have lists of probable locations and are working them in priority order. Some of them give me hourly reports. Still, one feels they lack a little . . . originality. Whereas you . . .”

“Don’t mind breaking the law,” I finished.

“You tracked Mr. Hardaway to his father’s exclusive club, only rumored to exist, and got past our security on your first try with absolutely no planning.” He paused. “That’s a helluva résumé.”

“I appreciate the vote of confidence or whatever, but I’m not whatever it is you think I am. I don’t have a business or an investigator’s license or any of that.”

“I’m confident my lawyers can draft an agreement that protects us both.”

“No. You don’t understand. Even if I was interested in helping you, and even if I thought I could keep up with those other guys, I don’t have a career or reputation to worry about.”

“Ah,” he said, nodding. “You mean you don’t want to spend the next several days looking for someone only to lose out and be left with nothing.”

That wasn’t quite it, but as I struggled for a better way to explain it, he rolled to the side table with a parcel and opened a drawer. He rolled back and tossed a thick stack of bills on the coffee table in front of me. It was heavy enough to shake the glass. It was brand new, by the looks of it. Even the little paper band around the middle was crisp. The label had a bank logo and said $10,000.

I sat up. I’d never seen that much money. I took it cautiously and flipped through the bills. They were stiff and had the pleasant feel of fine stationery. The smell of fresh cash hit my nostrils.

“Damn,” I said with a snort. “Now I know why rappers are always making it rain.” I sniffed again. “Someone should bottle this.”

“I believe they’ve tried.” He sat back, smirking. “Agree to my terms, and you can walk out of here with that. Call it a non-refundable retainer to cover expenses. I won’t even report it to the IRS.”

I returned the cash to the coffee table and stared at it.

Cerise, what are you doing?

“There is an ex-boyfriend,” he said. “Or perhaps they’re still seeing each other. I was none too particular, you understand.” He motioned to the door, where Bouncerman was waiting in his turtleneck, hands clasped in front of him. “William will give you everything we know so far. But understand, the clock is ticking.”

I swiped the cash and flipped through it again. The stack was so much denser than I expected. Like it could stop a bullet.

I waved it. “You’re gonna give me a million dollars to find your ex?”

“No,” he corrected. “I will give you $960,000, minus $10,000 an hour, to find the child she’s carrying in her womb. My understanding is they’re attached.” He held out his hand. “Do we have a deal?”

[image error]

This is kidnapping, you know that right?

I tripped hard that night. I don’t remember all of it. Supposedly, I freaked out at some point and told everyone death was stalking me, that it was coming, that I could feel it. I started hyperventilating and Shanna cleared the room and that was it. Party over, oops, out of time.

The next morning, I woke around noon to find a strange man standing over me. Considering the events of the night before, this didn’t immediately surprise—not until I saw how he was dressed.

I shrieked and fell backward to the floor between the couch and the wall, claws up, ready to scratch his eyes out. But he just stood there, hands at the sides of his black suit, while his companion, a tall, thin black man with narrow sideburns, checked my closet and the bathroom.

“Clean,” he said, knocking over a beer bottle with his foot.

The man in the suit had a bulbous metal object in his hand, like a vajra or two-sided scepter. He slipped it into a holster under his blazer—a holster for a spiritual object. He bent to pick up one of the empty boxes of cordials from the floor. He counted the others among the empty beer bottles and trash around the room. My place was a disaster.

“. . . three . . . four . . . five.” He looked at me.

“I got hungry,” I said.

He tossed the box in the trash. His cheeks were pockmarked and his hair was heavily pomaded. He looked like door security for a pay-by-the-bottle club in Midtown. He even had the requisite merino turtleneck in place of a shirt and tie.

“Put some clothes on,” he said flatly. “Mr. Rottheim would like to see you.”

I looked down. I was in nothing but a Care Bears T-shirt and a new pair of granny panties. “Who?”

I genuinely didn’t know, but bouncer-man didn’t care.

“Let’s go.” He snapped.

“And what happens if I tell this guy to go fuck himself?” I asked.

“Trust me.” He picked up my jeans from the floor and tossed them to me. “It’s in your best interest to come.”

“Is that a threat?”

I slipped them on and went to pee. I closed the door but the man in the turtleneck blocked it.

“You wanna watch?” I asked.

He stood in a wide stance with his arms crossed.

“Fine.”

I peed and washed my hands and face and put my hair back.

“’Iss is ’idnappin,” I said, gargling. I spit. “You know that, right?”

“I’ll take you to the police after,” he drolled.

I swiped my mirrored aviators off the giant stuffed bunny in the living room and was ushered out the door. Sideburns stood guard on the sidewalk like I was a celebrity exiting a show. The stretched limo waiting at the curb took us uptown. There was a large touchscreen panel in the center that controlled the temperature and the music and the WiFi and the privacy window and everything, and all the seats in the back had their own foldout screens, like on an airplane. Sideburns drove. Bouncerman sat in the back across from me and watched me, expressionless, the entire way.

“You got any gum?” I asked. I still had a terrible taste in my mouth.

We stopped in front of an old stone-block mansion, not far from Maleficium. I looked up at it from the window. It was more tall than wide and wedged carefully between a pair of brick condo towers. Bouncer-man opened the door for me before walking to the front of the mansion. The limo pulled away, leaving me alone on the sidewalk with a bald pedestrian. He was watching the mansion like the roof was on fire. So I did the same.

The block stone of the building’s first three floors had dark runoff stains at the edges of the gutters that spoke to old age. A huge bay window rose from the second and third floors, suggesting there was a single tall space behind, like a ballroom or long dining hall. The very top floor was a later addition. The front of it was all windows, tinted and impenetrable.

“What are we looking at?” I asked.

The bald man turned to me then with a curious gaze, like he was utterly amazed I was even aware of his presence. That was when I noticed his coat.

A coat. In June.

Still, I can see why he was so fond of it. It was awesome. It was an old-style chuban, like they used to wear on the mainland centuries ago, only the buttons had been replaced. Each was different. One was stamped metal. Another was polished amber. Whatever had been printed on the fabric had long-since faded to wisps. Now it appeared as an early morning fog, or maybe smoke from a campfire. The man who wore it had skin of an odd color. It had a faint ocher hue.

“Dig the coat,” I said.

“Ms. Song,” Bouncerman urged me from the front door.

“Song,” the bald man said, as if both perplexed by my name and committing it to memory.

He didn’t move as I walked in the front, and I returned his gaze from the foyer until Bouncerman closed the door behind me.

“You know that guy?” I asked.

“Mr. Rottheim makes a lot of enemies,” he said, urging me toward an open elevator.

“An elevator in a house,” I said. “Huh. Will wonders never cease.”

It was narrow but elegant. By the buttons, the house had four floors and a basement. We rode to the very top, which had a mid-century, Frank-Lloyd-Wright-y feel. The stairs descending to my left were simple planks that jutted from the wall with open air between. The railing was solid glass. There was a waterfall in a nook and a library-office straight ahead, which is where I was directed.

I stepped into the room. I was alone.

“Wait here,” Bouncerman said.

A huge formal desk presided over the space, which included a full-sized boardroom table, complete with teleconferencing kid. The screen saver, a Finnish flag, bounced slowly across the TV. Between them, a couch faced matching upholstered chairs. Behind the desk hung a five-foot-tall portrait of a young man with brown curls standing before a bleak wall of chiseled rock. He rested an arm on it the way you might lean against a fireplace mantle. Everything smelled like new carpet—nice new carpet.

But it was the wall of glass that got you. The view was killer. I looked down to the sidewalk, but the bald man was gone.

The other three walls were paneled in well-oiled oak. Spaced evenly along the panels were ornately framed pages from old manuscripts. I browsed as I waited, leaning over the antique occasional furniture to squint at the once-dark scratch, which was so old it had faded to pale brown. I was studying a very large parchment, the size of a small poster, when Mr. Rottheim rolled in. Or at least I assumed it was him. It was the same man as in the painting, only thinner and sicklier and riding a wheelchair. He wore a loose padded house vest over a collared shirt. His feet were in leather house slippers.

“What do you think?” he asked.

He was considerably younger than I expected, which made me angry—that someone so young could have that much money.

“What do I think?” I replied. “I think you’re looking at five to ten for kidnapping.”

He nodded to the framed parchment, which was different than the others. Most of the pages had little hand-drawn diagrams, but the sheet in front of me contained a large illustration. A naked man, crudely drawn and out of proportion, stood under a gallows. The rope that had held him had snapped and part of it dangled from the wood. He held a flaming staff and there were symbols all over his body that matched those in the circle on the ground around him. Three long knives, each different than the other, poked up from the foreground.

“It’s from the eleventh century,” he explained with a little bluster. “Nearly a thousand years old.”

He had some kind of European accent, faint enough that he had probably been speaking English since he was a kid.

“Is that when the eleventh century was?”

My host pointed to the symbols. “Remind you of anything?”

I squinted. The UV-protective glass preserved the document inside but made it a little difficult to see with the glare from the big windows.

“Sort of looks like a circuit diagram.”

There were zigzags and T-junctions, all of which ended in a small circle, just like you’d see on an electrical schematic.

“People forget that modern science grew directly out of alchemy,” he explained. “Properly understood, they are the same. I’m Lykke Rottheim.”

“Louka,” I said, trying to pronounce it.

“Everyone calls me Luke.” He motioned to the pair of chairs in front of the desk. “Please have a seat.”

I hesitated. I had planned to take a stand, literally, but my host wasn’t at all what I expected. Given his condition, standing seemed rude. I sat on the couch. It was soft and I sank in comfortably.

Rottheim rolled closer and handed me a card. I recognized it. It was my plastic Duane Reade club card.

“It was in the pocket of your jeans,” he explained. Then he nodded to a wrapped parcel on a side table. “Everything has been cleaned and pressed.”

“Pressed?” I scoffed. I couldn’t help myself. Who presses jeans?

“You’re not an easy person to find,” he said with a smirk.

“Seems like your guys did alright.”

“But you’re not where the government thinks you are, are you? Do you even have a lease agreement with the Arab or is it all under the table?”

“The Arab? His name’s Abdul, thank you. And since you seem to know everything, you tell me.”

He took out his phone and read the screen. “Ce-Lei-Zi Song. Hong Kong native. Granddaughter of Wai-Ling Lau, a local restaurateur of some renown, it seems. Merit scholarship to Parsons School of Design.” He glanced to me like he was impressed.

I shrugged.

“Dropped out your second year, shortly after being arrested for assault?”

He glanced over me again. I think the idea was that I’m hardly big enough to assault anyone.

“I’m scrappy.”

“Charges were dropped. Second arrest for vandalism last year. Apparently you put a mural on the wall of a shopping center.”

“Trust me. It was an improvement.”

“Charges still pending,” he finished. He put the phone back in his vest pocket. “And of course, now breaking and entering. If one didn’t know better, one would think you were trying to get deported.”

“One does one’s best.”

“You’re here on student visa. Does ICE know you’re no longer enrolled?”

“If not, I’m sure they’ll figure it out.”

There was a moment of silence where both of us examined the other.

“I’m sure you’re wondering why you’re here,” he said finally. He took a sudden deep breath, as if it was a struggle to talk for very long. “I’m on the board of the private club you broke into the other night.”

I rolled my eyes and leaned forward to get up. “Jeez, what is it with you pe—”

“I’m dying, Ms. Song.”

It was calm and candid and I settled back down.

“Rare genetic disorder,” he explained, “which is poetic, really, considering the effort my parents put into ensuring my lineage.” He snorted softly. “I’ll see to it that the charges against you are dropped. All of them.”

“I’m not gonna dress up like a little girl or whatever Make-A-Wish fantasy—”

“It’s nothing like that!” he barked. Then he caught himself. “But as it happens, you’re not far off the mark.” He rolled to the wall of windows. “I have been living a kind of fantasy these last few months. Recently, it came to an end.”

He turned around again.

“It was with a young woman from the club. I know, I know,” he said, looking down wryly. “One ought to know better, et cetera, et cetera. But one does silly things when one is dying. One has to, to balance out all the seriousness: doctor’s visit and blood tests and long sobbing reunions with childhood friends who, not twelve months ago, couldn’t care less about you, as if they’ve only come to gloat.” He stopped. He smiled at his own bitterness. “The young woman’s name is Lily Ann Sobriecki, although she went by ‘Laïs’ at the club.” He glanced sheepishly to me. “I suppose you can guess what happened.”

“Pregnant?”

“Recently, after discovering her . . . condition, she disappeared. Left the club. No phone call. No email. I understand she’s distraught. Let’s just say we did not part on good terms. Unfortunately, while I wouldn’t quite call her a junkie, Ms. Sobrieki has a”—he paused—“vigorous recreational drug habit, which I was of course happy to fund. I would very much like to find her before she does irreparable harm to the child. I didn’t think I would ever have offspring, Ms. Song. I thought my family would die with me. Now that I do . . . Well, I can think of little else.” He paused. “Are you a religious person?”

“Not really.”

“No. Of course not. Me neither. You’ll understand the significance, then, when I say I’ve been praying at night, literally begging God to let me make it to the birth of my child.” He laughed once. “So far, He hasn’t answered. Nor do I expect Him to. But I’m honest when I tell Him there’s nothing I wouldn’t give. Nothing.”

“Look,” I said, “I’m very sorry you’re sick. And I don’t wanna be rude, at least not any more than I have to. But I’m struggling to see where any of this justifies breaking into my apartment.”

“Yes. I do apologize for that. But time is of the essence. I have nightmares of the police finding Lily in an alley somewhere, needle in her arm. That’s not a figure of speech. I awoke just this morning—” He stopped when he saw me getting restless. “But of course. The point. I will pay you one million dollars to find her.”

I sat up. “What?”

“I will deduct ten thousand dollars from that million every hour she is not found.”

“Wait. Did you say a million dollars?”

He nodded solemnly. “Technically, I think we’re down to $960,000 as of this morning, but close enough.”

“Down?” I squinted. “Who’s down?”

“I’ve already made the same offer to several private detectives. The police, of course, are none too interested since no crime has been committed.”

“Okay, I think maybe there’s been a misunderstanding. I’m not a private detective. You just said it: I’m an art school dropout squatting above a halal market.”

“The men I hired are all very good at their jobs, Ms. Song. You know the type—ex-police, ex-military. Very experienced. Very efficient. Very professional. I feel I’ve motivated them as well as I can. They have lists of probable locations and are working them in priority order. Some of them give me hourly reports. Still, one feels they lack a little . . . originality. Whereas you . . .”

“Don’t mind breaking the law,” I finished.

“You tracked Mr. Hardaway to his father’s exclusive club, only rumored to exist, and got past our security on your first try with absolutely no planning.” He paused. “That’s a helluva résumé.”

“I appreciate the vote of confidence or whatever, but I’m not whatever it is you think I am. I don’t have a business or an investigator’s license or any of that.”

“I’m confident my lawyers can draft an agreement that protects us both.”

“No. You don’t understand. Even if I was interested in helping you, and even if I thought I could keep up with those other guys, I don’t have a career or reputation to worry about.”

“Ah,” he said, nodding. “You mean you don’t want to spend the next several days looking for someone only to lose out and be left with nothing.”

That wasn’t quite it, but as I struggled for a better way to explain it, he rolled to the side table with a parcel and opened a drawer. He rolled back and tossed a thick stack of bills on the coffee table in front of me. It was heavy enough to shake the glass. It was brand new, by the looks of it. Even the little paper band around the middle was crisp. The label had a bank logo and said $10,000.

I sat up. I’d never seen that much money. I took it cautiously and flipped through the bills. They were stiff and had the pleasant feel of fine stationery. The smell of fresh cash hit my nostrils.

“Damn,” I said with a snort. “Now I know why rappers are always making it rain.” I sniffed again. “Someone should bottle this.”

“I believe they’ve tried.” He sat back, smirking. “Agree to my terms, and you can walk out of here with that. Call it a non-refundable retainer to cover expenses. I won’t even report it to the IRS.”

I returned the cash to the coffee table and stared at it.

Cerise, what are you doing?

“There is an ex-boyfriend,” he said. “Or perhaps they’re still seeing each other. I was none too particular, you understand.” He motioned to the door, where Bouncerman was waiting in his turtleneck, hands clasped in front of him. “William will give you everything we know so far. But understand, the clock is ticking.”

I swiped the cash and flipped through it again. The stack was so much denser than I expected. Like it could stop a bullet.

I waved it. “You’re gonna give me a million dollars to find your ex?”

“No,” he corrected. “I will give you $960,000, minus $10,000 an hour, to find the child she’s carrying in her womb. My understanding is they’re attached.” He held out his hand. “Do we have a deal?”

[image error]

October 27, 2020

It is impossible for a man to learn what he thinks he already knows. ― Epictetus

October 25, 2020

(Fiction) In the Library of Thieves

After Beltran’s visit, some of my restrictions were lifted. I was not allowed to speak to Etude and had no idea where in the cavernous dungeons he was being held—the same dungeons where the Eye was discovered by the first maestri some seven centuries before. I was also kept from the high towers, where everything important seemed to happen. But there was a garden promenade left open to the sky and I was allowed access to it and to the library. Both were utterly, unspeakably magnificent. The library was large enough that one could genuinely get lost. I was never a scholar like Hank, but being raised in the centuries before television, books have remained my first love, and over the next several weeks, I spent many hours between those stacks in the company of voices past—not just the books but also the ghosts that would sometimes steal them when my back was turned. I learned quickly to feign disinterest before making a selection, lest the book I had chosen be whisked away behind me. Their thefts were an attempt, I’m sure, to get me to go innocently searching, to explore the buttressed vaults, caged nooks, and octagonal chambers that connected each to the other inside that great place.

Of all the spirits that pestered me, I made acquaintance with only one. Judging from her dress, which I only caught in glimpses, my girl was a servant in the time of Cromwell. She must have spent much of her life scrubbing the floor, for that is what she did compulsively. When she spoke, it was always to herself or to someone else not present. I heard only fragments of stories, and she would often disappear midway through. Sometimes she would glance at me first, like a wild animal, as if just realizing I was there before blinking away in fright. But as one week turned to two, and two to three, my continued presence in the library coaxed a certain calm, as with a tiger, and her stories lengthened. She didn’t relate them directly, but if I sat and read near the lower arches—which were close enough to the sea that in the quiet I could hear the gentle lapping of the Mediterranean—she would often appear, scrubbing the floor (always scrubbing, scrubbing) and talking to herself, which was of course talking to me. She seemed terribly lonely, and I would put a finger in my book and close it and look away from her and listen as she told a friend named Charlotte, who was never present, all the reasons she should stay away from the farm boy down the lane, for he was a ne’er-do-well if ever there was one. I listened to numerous one-sided arguments about why she hadn’t cleaned the kitchen or brushed the horses. She told a great many lies, especially about where she went when she wasn’t needed and why it was she lingered so long there.

How she came to the Keep of Solomon, I could only guess, but the reason for her departure seemed clear. Her unconsummated dalliance with the farm boy down the lane had turned sour after she caught him mounting her friend Charlotte behind a tree. Realizing he had no intention of honoring his promises, she demanded the return of her dowry. But the boy had already spent it on drink. My maid immediately reported him to her lord but was told she shouldn’t have been so foolish as to give it to such a man in the first place, and the matter was dropped. It was only later, after the farm boy had broken Charlotte’s heart as well, that my maid plotted her revenge.

She visited a “lady of the dells”—a witch—and gave of her hair and of her womb. It was not meant to damage him. She repeated that many times. It was merely supposed to teach the boy a lesson. What happened next, I was not told, but having dealt with a number of witches, it’s easy enough to guess. My maid was arrested and spent several years in a brutish prison, as I had, before being offered clemency in exchange for a report on the witch, who was later hanged. In consequence of her service, she was indentured to the servants of The Masters and later met her end within the walls of the Keep of Solomon, where she remained as a wayward spirit.

Early one morning, while busy with a pale and brush, my new friend airily explained to Charlotte that she was so beautiful and could do so much better than a simple farm boy from down the lane, and that if she would go to the city, she was sure to catch the eye of a gentleman. Amid the rambling, which clearly predated the rest of the tale, I heard a stray word: escape. It was spoken in the same voice, but the tone and cadence were different, as if interjected from a different time and place. I looked up and the young woman was peering at me. Then she disappeared again.

Amid the shelves of the library, I rediscovered bits of my past, including a rare manuscript by Wilm Castleby, penned in his hand. Seeing his familiar scratch brought back memories I had completely forgotten—not ones eaten by the forest but those simply lost in the years. I also discovered a collection of antique photographic plates made of glass, some of which had cracked and been mended with tape or glue. They filled a series of chests inlaid with wood grooves, each holding a single vertical slab. The Masters, or rather the librarians and scribes who worked for them, had used the new medium of photography to record the last of the woodfolk and the other child-races, whose numbers had by then precipitously declined. Many had fled to other realms after the pogroms of the 17th century, but many more had been “harvested” a century later during the so-called Age of Enlightenment, when innumerable pieces were cut from their bodies, living or dead, and sold to fill wunderkammer and gentlemen’s cabinets of curiosity. By the 19th century, precious few were left, and The Masters’ scribes made portraits, etched into glass with salts of silver. I saw twig-fingered treeherders mourning ricks of corpses, giggling gnomes hidden under furniture and machinery, preens of pixies pushed under rulers and tape measures, naked and ashamed. Some of the images were quite poignant, such as the satyr mother bent over the still body of her faun, her breasts still heavy with milk. Others were inimitably disturbing. Many of the pixies were cowed by rough-gloved fingers, their tiger-striped wings forcibly and painfully spread. The presence of several empty slots in the progression suggested there were images missing—I expect the most explicit ones.

But my greatest discovery was a set of secret writings that I myself had smuggled to America, for which I was later imprisoned for heresy. I assumed they had been destroyed, along with my freedom, and as soon as I recovered from my shock at their continued existence, I shuffled to the nearest chair and scoured the yellowed pages. I didn’t stop reading for hours.

After being rescued from the attic in Whitechapel, I was arrested and given a choice: prison or deportation, which is how I found myself sailing to India. I had finally caught the attention of the lords of magic. I had triggered it, in fact. I had never completely given up my desire to be rid of my curse, and as it happened, two years before the madness in the attic and shortly after Durance and I came to London, I happened upon a speaker standing before a large crowd—a woman, which was unusual, more so that she had the distinctive cadence of a Russian accent. There were not many Russians in London then. The British had expelled most of my countrymen during the war in the Crimea. It was rare to find one at all, let alone speaking openly before a large crowd. So I stopped.

In five minutes, I could tell she was from Ukraine, not all that far from where I was born. She was also apparently a spiritual leader, a representative of something called the Theosophical Society, a kind of magico-religious fraternity built on Eastern mysticism and worship of the occult. The Masters had been so successful in their persecution of magic, which was part of daily life as late as the seventeenth century, that by the nineteenth it was making a comeback. Not in earnest, of course. More as a quaint affectation, the way certain fashions of a bygone era will reappear ironically. Victorian gentlemen in particular, having made a fortune in machine industry, were often members of secret societies based loosely on Egyptology, Hindu spiritualism, or other bland cults of the Orient. These were generally toothless but attracted many followers. Indeed, as I moved around the crowd, I realized the speaker had already packed the hall on whose steps she now stood and that she was giving a second, abbreviated talk to the poor and the latecomers who had gathered in the hundreds outside. Since there was little chance of meeting her amid such numbers, I made a note of her name, which was printed on the marquee—Madame Helena Blavatsky—and went on with my business.

I wrote to her, explained my heritage, and told her enough of my encounter with the woodfolk and resulting curse that I thought I might at least get an audience. I delivered it to the hotel where she stayed, but the disinterest of the clerk suggested my post was only one of perhaps dozens or more. Several days passed and I noted in the paper that “Mme. Blavatsky, Noted Medium and International Speaker, Sails for Hindustan.” Life went on and I forgot all about it. Thus, I was quite surprised when the police, having thrown me in a prison hospital to recover, informed me that I had a solicitor and that he had secured for me an exit from a lengthy prison sentence. The solicitor, a Mr. Bentley, told me he was employed by another attorney, an American named Olcott, who had been part of the tribunal charged with investigating the death of President Lincoln. When I asked why Mr. Olcott had freed me, Mr. Bentley said he didn’t know, that he was instructed merely to secure my release, which he did. I was then taken under police custody to a steamer ship, the first I had ever seen, and placed immediately aboard.

We stopped in Cairo. I have never been so hot. I saw the pyramids and so much more squalor than I had presumed could exist in the world. The British seemed as interested in their empire as a dog its fleas. But of course in that, they were hardly unique. Within the week, thankfully, we set sail again from a port in the Red Sea. It was a further two weeks before I met the woman who had freed me. She was as curious a figure as any I would encounter—warm and genial but also much coarser in her manners than I expected. She made crude jokes, often involving bodily functions, and cackled at them herself. Her clothes never fit, her hair was frizzy and unkempt, and she never shaved. Her insults were rare, but when they came, they were vicious, direct, and incisive. I cannot recall anyone the Madame insulted who did not instantly become a lifelong enemy—including, eventually, Mr. Olcott, who had been her first and staunchest patron.

When I was finally able to ask my lady why I had been summoned, I was told that after receiving my letter, she had attempted to contact me “on the astral plane,” but that she had been rebuffed by “an immense psychical power,” so strong that she was weary for many days. By the time she recovered, she had to leave for India. Thinking I was a medium of rare and notable ability, she had her agents at the Theosophical Society’s London lodge, which included a number of state luminaries, report on my movements. She said I had been summoned to India so that the truth of the “psychical emanance” could be discovered and would not be lost in some brutish prison. In the meantime, I was given an occupation. I was to be a servant and tutor in my lady’s house. Like many colonial Europeans, she sponsored a small school where poor children were given a rudimentary education.

Though remanded to the Theosophical Society, I was not kept as a prisoner, nor did I think of fleeing. India bewitched me. It wasn’t simply beautiful. It was opulent, and I understood why the British coveted it so. The wealth they drained seemed eternally replenished by the constant motion of the people—more than I had ever seen before. Everything there danced and grew over and above everything else, a boiling mixture of faiths and languages and food. Pickpockets and saints walked elbow-to-elbow in the crowded markets with gods and livestock. There didn’t seem to be any order in any of it, and yet, somehow, everything got done. Fields were planted and harvested. Levees were built or reinforced. Bright festivals were held. Fish were caught and brought to sale. Oh, the British strutted about admirably and said “Here, here!” and “What, what!” but they knew it was a show, and any man outside the range of their artillery was free to live exactly as his fellows had since before the time of Christ.

Despite my many years in her service, I would never come to know Madame Blavatsky well. I was but one part of a very large retinue. From time to time, however, she would quiz me about the “emanance,” and eventually my defenses crumbled before her potent wit. I told her I had known only one person who could rightly be called psychic, and that she had been wracked by strange and debilitating visions.

“By the heavens, woman!” my madame exclaimed, “I hope you wrote them down!”

I explained to her that Anya and I had been scullery maids, that we barely had enough to eat and there was no question of affording paper and ink.

“She’s haunting me,” I admitted one rare evening when the two of us were alone. A gentle breeze brought cooler air up to the garden where it mixed with the scent of jasmine and roses. “I left her son in a work house.”

Madame Helena chuckled and shook her head. “It’s not a haunting,” she explained in our native language. She held the bit of a hookah between her lips. “She is not a ghost. You cannot think of her experience of these events as you do your own.”

When I asked for clarification, she took several long drags from her water pipe.

“Imagine your life as a tapestry,” she said, “or a scroll rolled out before you. You would be able to see it all at once—as if it were a single coherent thing. When your friend expired, that is what she saw: your life, her life, the flow of time as a tapestry. These acts you experience as discrete events are for her instances of a single moment whereby she pushed from that tapestry all the threats in it—at once. Not one at a time with years between. For her, it is a single psychic rebellion accompanying the moment of her death. You, trapped here in time, are forced to see each appearance singly. I regret that we have not been able to make contact. At each of these moments we experience, she is just ascending to a higher existence. She would have much to teach.”

I marked my one-hundredth birthday meditating cross-legged on the bank of the Adyar River. I wore shoes of fragrant sandalwood and a beautiful red-patterned sari with a gold necklace. My hair, having not long to regrow, was then very short, a style I have been partial to ever since, even when it was neither stylish nor convenient. By most measures, a century of life made me a very old woman. But I felt young there. It wasn’t just that everything was new, or new to me. It was that all those things that were new to me were so very, very old—timeless, even. It made me feel like a little thing, a young thing after all, and if in my tiny century I had become heavy with misfortune, I shed it like a snake skin somewhere between the river and the elephant grass.

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky died in 1891 from a mixture of poor health and acute influenza. At her funeral, I was given a parcel. Inside was some cash, a letter addressed to me, and the loosely bound pages of a manuscript, which I was to smuggle to America.

Do not read it, she warned in her letter, or you will be complicit in my heresy.

I didn’t then. Not for many days, in fact. I didn’t read it until I was locked in my cabin, steaming my way to America.

During her life, Madame Helena claimed publicly to have contact, by means of astral projection, with an ancient and arcane order whom she called The Masters. She described them as Indian swamis and said they had been manipulating the course of human events for centuries from their fortress deep in the mountains of Tibet. All of that is a matter of historical record. And yet, it was not entirely true.

Since The Masters did not allow anyone to speak openly of their existence, she had hoped that by altering certain facts and circumstances, she might escape reprobation. It was also, I suppose, another example of how she was ever willing to knead the basic facts of the world to better suit her ends, especially where that deception made others more susceptible to some higher truth she wanted them to see. Her invented Masters better fit the common preconception of what such a mystical order might look like, with robed ascetics chanting over incense in some mystical mountain monastery. Like many eccentrics, Madame Blavatsky’s profound insights into the universe were matched by an almost perplexing naivete about the people in it. The fact that one of The Masters was in fact Indian meant that even her altered version was too close for their comfort, and as the Theosophical Society grew in popularity, she was warned, repeatedly, to refrain from speaking of the High Arcane. In typical Blavatsky fashion, she laughed off the threats, only to suffer character assassination at the hands of the Psychical Research Society, which issued its infamous report denouncing her, and she was forced from the very organization she had founded.

In her unpublished chapters, Madame Helena argued, with her critics, that we can discern the nature of the deep universe from the basic facts in evidence: that the earth spends half of each day in light and half in darkness and that correspondingly there is both suffering and joy in the world. In such conditions, it was impossible for pre-modern thinkers to conceive of the world as existing anywhere but on the border between great warring realms—stuck, as it were, in the middle. For the Norse, Earth was Midgard, the middle realm, just as China considers herself the Middle Kingdom, with heaven above and darkness below. So, too, in Christianity and Islam, where we inhabit neither Hell nor Paradise but some space between.

Madame Blavatsky asked how anyone could possibly believe this. It was perhaps forgivable, she said, when we considered the earth a bowl or plate covered in a shroud of fixed stars—a canopy through which holes had been poked so as to let the divine light peek through and remind us even here of the glory of God. Once it was clear that was not the case, that each of those tiny twinkling lights in the sky was not a pinprick but its own distant sun, our ancient conception of ourselves as the center of things was never updated. It was, like that old canopy, fixed in place. Belief in the middle, she said, was psychologically pleasing rather than true. It suggested that everything was in some way about us, that we were yet the axle of the universe—albeit symbolically rather than literally—that the earth was the field of sport upon which every gaze in the universe was transfixed, and that our choices alone would decide the fate of the cosmic battle between light and darkness.

Hardly, she said. The night sky was not a shroud but something closer to an infinite well—cold, barren, and immeasurably vast. We didn’t seem to be in the middle of things at all. We seemed quite far flung in fact. That our planet was tilted and turned every day between light and dark certainly suggested a struggle, a supposition supported by the common occurrences of suffering and joy. And it was also true that the earth seemed to be neither heaven nor hell, as the old religions had correctly assumed. But, she asked, if our planet was the focus of the conflict, if we were the front of the war, why could we not see the forces of light? Why was there only darkness, darkness, darkness on all sides? An endless quantity of it, in fact. Our planet was swimming in an ocean of the stuff, as was the galaxy itself. Here on earth, evidence of malice was patent and universal, while evidence of grace was scant and indirect. What of it existed seemed only to come by our hand. If the divine were acting on earth, she said, it could only be very weakly, as if at a great distance.

But the crown jewel of her argument was what she called “the state of immanent corruption,” whereby the whole of life, as the gurus in India had taught her, survived only by consuming other life. Anything that remained motionless, that took no act, inevitably succumbed to rot, and this applied even to the mountains and the rivers. All things not only suffered, they degraded. Where, then, was the influence of the light, of the incorruptible and unchanging divine whose power flowed from itself and from no other thing? Everywhere on earth there were agents of evil. One tripped over them outside every door. Yet, how rare was the saint? How rarer still were his qualities: knowledge, love, courage, wisdom, and compassion?

The truth, Madame Blavatsky argued, was obvious. We were not the middle kingdom. Earth was not the center of the universe, nor was our universe the center of all universes. Ours was patently a realm of corruption, a realm of the dark powers as other universes were realms of light. Adrift in some distant corner, we had cast off our shackles in a great conflagration, just as the ancient texts had taught us, but we had not been strong enough to embrace the divine, which is why things stood as they did, where the earth spins equally between light and dark. Our planet is not the focus of the fighting. It is an enclave of resistance well behind enemy lines.

If this doesn’t seem heretical to you, it is only because science would eventually come to vindicate it, at least in its significant facts. My lady’s views on “immanent corruption” presaged the laws of thermodynamics, which were just then being formulated. She also suggested that the distant dots of light in the sky were, like our sun, symbolic of individual acts of rebellion and that the true nature of a dark universe must be cold, bleak, and unradiant. And in as much as our cold, dark universe had been created—forged was the word she used—by the lords of night as a font of suffering from which they could power their armies, that suggested, first, that suffering should be plentiful and grace scant, and second, that such a place would have a violent beginning: a big bang. This latter observation is especially noteworthy since it contradicted the prevailing scientific view of the time that the night sky was a reflection of the divine creator: glorious, eternal, infinite, and unchanging. And that was the danger. For if people knew—if they really knew—that our dismal planet was adrift among the dark gods, they might lose hope. More than that, they might come to question The Masters’ grand enterprise. And that could not be tolerated.

Madame Helena bid me give the manuscript to a young goblin, Anson Gruel, who had recently taken proprietorship of The Barrows in New York City, where my lady had lived for a time. It was her hope that by surrendering it, I might negotiate clemency on the remainder of my sentence, and that by keeping it in trust with Anson, who was as greedy with books as most goblins were with money, it might avoid the flames.

I shut the loose-bound pages and held them to my chest. One of those, at least, had come to pass.

Selection from the forthcoming conclusion to my unheralded epic urban fantasy, FEAST OF SHADOWS. Part One is available now.

cover image: Denise Grünstein – Looking at the Overlooked (2014)

October 22, 2020

(Fiction) Dark Opera of the Gods

Crows.

I heard them before I saw them.

“Get down!”

Etude didn’t move. He stood in the bramble above the narrow river and watched the far shore as agents of The Winter Bureau walked in and out of Cafe Cinota, carrying all his worldly possessions through the red portal and loading them into a truck. All that remained was the jewel, which hung around his neck. It had been cut and polished, although I no longer remember how. I only know we had carried it in a lead box at first because it had to be cut before it was struck by the sun’s rays, which it now turned to a faint rainbow against his linen shirt.

The crows descended and swirled around the cafe. Dozens, looking for places to land. But my young friend hardly noticed.

“We have to go,” I urged from between the reeds. I tried to pull him down, but he pushed my hand away and took off down the narrow lane toward the main road, which crossed the river half a kilometer ahead.

As soon as we were out of sight, he stopped suddenly and turned. “How did they find us?”

I stood straight, indignant. “What are you suggesting?”

“You know exactly what I am suggesting.”

I turned to make sure no one was watching. “You want to argue about this here? With half the Bureau on our backs?”

He jabbed a finger toward the restaurant. “That is my life! And they are carting it away.”

“It will be the very same story at my house. Not that you ever bothered to ask. How do you think we’ll get everything back? By shouting?”

“For many months I have come and gone without incident. ONE DAY after your arrival and we are discovered. Do not tell me that is an accident!”

“You may chastise me later.”

“There will be no later. Goodbye.” He turned and walked away.

“You need me.” He didn’t answer, and I followed, glancing back repeatedly. “You need me to breach the forest. No one but an immortal has a surfeit of memories.”

Nothing.

“How many have I sacrificed on your adventure?”

He spun. “You wanted them gone! Well, congratulations. You got what you wanted. I release you from our bargain.” He waved his hands over me and started walking again.

The cawing of the crows faded as I continued after him down a slow slope toward the main road ahead. A car passed carrying a disinterested driver.

“Where are you going?” I demanded.

“That is none of your concern,” he replied, marching.

“And these?” I held up my marked palms.

He stopped again. He scowled. He extended his hands to me, palms down, and I took them. After a moment, he turned his to check.

The marks hadn’t moved.

He scoffed at them like they were spoiled child and started again down the road. “It’s no matter. They will return in time. Goodbye!”

“This is ridiculous!” I strode after him. “Stop!”

He didn’t.

“Please?”

He turned a corner and was gone.

I sighed and ran after him, but when I turned the same corner, he was gone. There was no one on the sidewalk but a few townsfolk going about their midday errands. I saw a small side street just ahead and ran to it, but the way was empty. A pair of old women on a distant stoop cackled to each other as they knit a heavy rug from opposite ends. At the corner, a man sat reading the paper and smoking a pipe in front of an auto yard fenced in leaning sheet metal. I asked in Hungarian if he had seen a young man pass. Judging by his scowl, he didn’t speak Hungarian, and I hacked through enough Romanian to get the point across. He shook his head.

The crows took to the air. I heard their discordant chorus as it rose above me, and I ducked under the eaves of a locked door. But it wasn’t necessary. They weren’t looking for me. They weren’t looking for anyone. They knew exactly where they were going. They flew in churning mass, like giant black boomerang, whirling toward the embankment park along the river.

He’d used magic to move himself somehow. They had sensed it.

“Idiot.”

I ran back to the corner. Weeds gathered along a wood-slat fence. Just past it, a short, round man in an aging sport coat removed an open-topped box from the trunk of a boxy Communist-era sedan. He had stopped on the road in front of a multi-family dwelling. A middle-aged woman and her daughter chatted with him excitedly from the front porch. It seemed they were happy to receive whatever he was carrying.

Cars honked down the road as three black SUVs passed me on the river road and gunned their engines.

“Shit.”

The man with the boxes had walked up the steps, where he kissed the cheeks of the woman and disappeared inside with his treasure. The trunk of his squat sedan, which had once been yellow, was still open. The engine was sputtering. I looked down at the marks on my hands.

“Dammit.”

I got in, released the brake, and drove off. The vehicle had absolutely no amenities—part of the dash was missing, and the seat was nothing but stitched vinyl stretched over a frame—but it was built like a communist tank. I turned onto the river road as the owner came running onto the street behind me. The women were behind him. I accelerated through traffic, honking and swerving around the lazy cars. Agents of The Winter Bureau were arresting Etude in the narrow park. I slammed the pedal to the floor and the once-yellow sedan chugged: a little faster, a little faster. Luckily, the grade was with me, and I picked up enough speed to ram the rear corner of the middle SUV, forcing it to strike the one in front like a billiard ball. The lead vehicle struck a tree. The one I hit bounced off it and rolled down the embankment and into the river with a splash. All things considered, the force of the collision should’ve hurt me—at least caused a bruise. I had badly dented the hood of my tanklike sedan and dislodged some part of the internal mechanisms such that the timing belt squeaked on and off loudly. But I remained unhurt.

“Get in!” I yelled to Etude, who was on the ground, along with everyone else.

I hit the gas before he shut the door. In the side mirror, I caught one of the agents casting a spell. I don’t know if it worked. The other got to his feet and fired a gun that would’ve killed me if the trunk hadn’t been left open. The solid metal lid was still raised in front of the rear window. Several bullets impacted it and left large circular dents. Etude noticed the mahogany-haired woman in the side mirror. She had pulled out in the third SUV and was giving chase.

“Well . . .” I said, raising my voice over the loud, shimmying squeak of the engine, “we’re not going to get far in this.” It could barely pass 45 KPH.

I turned onto a narrow cobbled street and wove through an old neighborhood at speed. Our pursuer was right behind us, but on the narrow lane there was little she could do. When the way was blocked by an outdoor cafe, I turned sharply onto a main thoroughfare, where there were enough oncoming cars to keep the mahogany-haired woman from getting around us in the other lane. That would change, I knew, as soon as we reached the edge of the city, where the roads would no longer be medieval in width, but there was no other choice. If we turned and drove in circles through the old town, it would keep our immediate pursuer at bay, but it would also give her compatriots ample time to involve the police, or gather reinforcements. Or both.

“Are you okay?” I asked.

Nothing.

Apparently, I was getting the silent treatment.

“Oh, poor you,” I mocked. “You don’t trust me. Is that it?”

“There was a very adequate binding on the cafe,” he shouted over the engine. “For months now, I have come and gone—”

“So you said. But your face is plastered across every police station in the valley. Did you know that?” I had the WANTED notice folded in my pocket. I pulled it out and threw it at him.

He unfolded it and read in silence. He looked down at his bare palms.

Behind us, the mahogany-haired woman kept a close follow. A wood fence lined the road. She could easily swerve around and knock us into it. Her car had the power, whereas ours was sounding more and more like the little engine that could. But she wanted us alive, and there were cattle fields ahead.

“If you have any tricks left, now is the time.”

The moment the mahogany-haired woman had space in the oncoming lane, she gunned her engine and jerked around us—right into a massive buffalo. A heavy-uddered cow had stepped in front of the SUV and bellowed deeply as it was struck. The front of the SUV crumpled and flew apart as both went flying. I swerved off the road to avoid hitting them and rumbled down the embankment to the field. It was not very steep, but the boxy car was top-heavy and turned on its side and slid down the grass to the dirt. No serious damage was done, but we weren’t going anywhere.

I hit the steering wheel.

Etude opened his door, which was now the top of the car, and clambered out.

“Where are you going?”

“I cannot leave it to suffer.”

I crawled out after him, but by the time my shoes hit the dirt, he was already kneeling before the prone and bloody buffalo. It was still breathing, despite that most of its viscera were exposed. He stroked its neck and whispered with closed eyes as the mahogany-haired woman struggled noisily out of her upside-down vehicle, like a butterfly from its cocoon. I walked to her. When she stumbled free, I punched her hard in the nose, which made a very satisfying crack, and she fell back. I checked her for weapons. One revolver, full barrel. I checked the rounds. Standard-issue etched silver, very effective against creatures of the night. Some things hadn’t changed.

Sirens approached. Etude was still bent over the animal, which had finally expired. I turned back to the sideways car.

“We’re stuck,” I said.

“No.” He stood, grim.

“What do you mean?”

When I turned again to plead my case, I saw the other cows wandering toward it languidly. A pair of them pressed their heads to the roof and righted it with a nudge. It bounced on its tires and we got in as the angry herdsman ran at us from across the field. The car struggled to get going at first, but when it did, it resumed its high-pitched squeal, and we left the man in the dirt. We drove over the bumpy ground and pulled onto the road, where behind us the rest of the herd milled about the pavement, completely blocking the ingress from the town. The last black SUV, the one that had struck the tree, was stopped before a hoofed wall, along with a complement of police vehicles. The men got out and I waved out the window as we drove away.

“Are you hurt?” I asked him.

The left knee of his linen trousers was torn. I could see smears of blood. I don’t think it was from the crash. I think the agents had tackled him.

He glanced with a scowl to the symbols on my hands. “I will live.” He looked around us. “You are going the wrong way. This will not take us to the forest.”

“They may be watching the forest.”

“Such an effort would be useless. The area is too large.”

“Not if they discovered our rope path.”

We had left it half-buried in the leaves so we could return.

“One inch in ten thousand acres? Unlikely.”

“But not impossible,” I countered.

“We have no choice,” he growled. “We cannot make another path. The muskroot is in the cafe, along with all of our supplies. The nectar. My notes. All my work!”

I banked right and moved up a country lane that followed the course of a large stream. “I think it’s time you told me what this is all about, don’t you?”

The suggestion seemed to perturb him. “You asked not to know.”

“If people are trying to kill us, then I think we’re past the point of caring about what I do or don’t want.”

“It’s not a question of safety.”

“Then what?”

He was quiet. He continued to sulk as we rose into the foothills. The road curved with the falling water and trees sprung up all around. Within a few miles, now under cover of a forest, we came up on a cart hauling hay. The driver sat at the front of what seemed an impossibly tall pile of the stuff as a pair of stocky horses, barely larger than donkeys, click-clacked laboriously. The man didn’t even look as our car passed making that awful racket. I looked again at the marks on my palms. The engine struggled with the slope and I shifted gears. At a slight bend, where the rising road was wider on the left, I pulled to a stop.

“What are you doing?”

“Get out,” I demanded.

He seemed shocked.

“Get out,” I repeated.

His jaw set. “Very well.”

He climbed out in a huff, and I began accelerating, faster and faster. I didn’t stop, even as the car began to shimmy dangerously. The deep stream fell across the rocks in a ravine about ten feet below the road. At the very next bend, I turned hard and drove straight over the side. The car hung in the air a moment before smashing hard into three feet of water under which was a field of boulders and gravel. Glass broke. Water poured into the car and drenched me. As expected, I suffered no serious injuries. I had been whipped hard, but I had been wearing my seatbelt.

The car settled in the water, tilting up and to one side. The movement caused a rock in the creek bed to shift and everything slid backward with a jolt. Water poured through the broken windshield. The shallow flow wasn’t more than a meter deep, but it could drown me if I were trapped in the seat. I fumbled with the belt as the stiff flow cascaded over my neck and chin, which I kept elevated to breathe. The water was freezing, and my hands shook as I tried to pull myself free.

I felt another hand on mine and pulled. Etude was under the water. The seatbelt came free and I pushed myself through the torrent and out the door. The vehicle rested at an odd angle, propped up by a round boulder. The back tires were still spinning slowly. Getting out proved to be more of a challenge than I expected. Both of us ended up falling more than once on our return to the shore, where we collapsed on a grassy embankment two meters below the road. He laid on his back and tried to catch his breath.

“Perhaps it’s time to be honest with each other,” I suggested.

“It would be a nice change.”

“The Winter Bureau seems to think you’re the most dangerous man in the world. Why? What are you after?”

He was smiling. He started to laugh. Deeply. Genuinely. He glanced to me and laughed louder.

I had to force back a smile. “What’s so funny?”

“Truly,” he said, “you are as unpredictable as you are aged.”

We sat up and looked down at the car, crumpled and tilted. The force of the water finally got the better of it, and it fell to its side with a splash. It was done.

“We needed to ditch it,” I said. “This way they’ll wonder what happened. They’ll have to check all the hospitals, in case we are injured.”

“Aye,” he nodded. Then he laughed again. It was giddy.

I glanced around at the tall pines of the forest. It was so peaceful. It reminded me of home.

“The Necronomicon,” he said.

A bird called plaintively from the branches.

“What?”

“I seek the Necronomicon.”

He sat on the grass cross-legged and coughed. Every part of him was dripping. Same for me.

I was silent a long moment. “You lie,” I accused.

But it didn’t seem like he was lying.

“The book was destroyed,” I said. “After the war. I smuggled it out of The Handred Keep. I risked everything—”

“Exactly,” he interrupted. “Which is why you told me never to tell you the truth.”

“I . . .? Have we had this conversation before?”

“Yes,” he said, shaking his hands of water. “Several times.” He sighed. “And each time, it is the same. You ask how it could’ve endured, and I explain to you that it’s not a book.”

“If it’s not a book, then what is it?”

“Nebuchadnezzar transcribed what was whispered to him through the flames into a language of his own devising, which was why it was undecipherable.”

“I know that.”

“But he was a fool. It’s not the language that matters. That’s why the ancients spoke of the power of the Word—logos in the Greek. It’s why Master Newton was obsessed with Biblical numerology. He understood the patent truth: that’s simply how gods talk. They don’t make guttural noises, like animals. Divine language has a—a higher structure, something very difficult for us even to comprehend. You think the Nameless are so silly as to send across a code that could be broken simply by writing it backwards, or in a foreign tongue? They had to transmit it as a text because in Nebuchadnezzar’s time that was the height of our art. The only way anyone here could record information was by scribbling symbols on pages. If they had it to do over, today they might send a sequence of DNA for us to grow in a lab. Or machine code. But it was never the script that mattered. What mattered were the second-order glyphs embedded in the information itself. You see?”

I didn’t.

His head and shoulders dropped in frustration. “I suspect they can rearrange themselves, and in so doing, they can also rearrange the text. It isn’t a book of spells and incantations, but it contains those things—many more than are displayed on its pages at any one time. The ancient ones knew the old king would try to trick them. He was nothing if not vain. So they made certain the book could be found. It is a well—or battery, if you prefer—from which endless darkness flows. It can be used to power spells, like the amulets of Zaragoza. When it sensed it was lost, it became a kind of antenna—a transmitter, calling out to seekers of the dark.

“The Necronomicon is all of those things and none of them. It is not anything so crude as a mechanism. It is closer to the emergent complexity of life than it is to a book or a machine. That is why it could never be copied. Many reproductions were made, but each was stillborn. For there is no one here who speaks the language of the gods.”

“Then why not send more?”

“The barter was for a text. A kingdom for a revelation. Nothing more. Theoretically . . . the glyphs could sustain a portal, if one could be opened, from which more like it could come across. However, if the seekers of the dark could achieve that, then there would be no need to send another matrix. They could simply summon the old ones themselves, or their armies.” He studied my face, dour as it was. “Now do you see? It is not a book. It is a spy, a master saboteur sent to destroy us. It has but one purpose: to return mankind to slavery. So tell me. Do you think that such a thing could be destroyed by beating on it with a hammer? Or shouting incantations at it?”

“No,” I said softly.

I was quiet a long time.

“Then why do you seek it?” I asked finally. “If it’s hidden, why not leave it alone?”

He closed his eyes. “Do not make me say. Not again.”

I felt the grass under my fingers. “Please. I must know.”

He touched his chest in the same place he had when he told me of his master and teacher.

“When the seed snapped,” he said, “my master was confused. Was I not the one whose coming was foretold? Was I not meant to serve my people in his stead? It was a conundrum. So he inquired of my future. While I writhed in pain, he retired from the village and ate of the sacred fungus, which turns death into life, and summoned the ancestors and asked for shades of the future. They—” He stopped. “They revealed a dark destiny. They said I would be responsible for loosing a great darkness upon the world. That it would fly free by my hand. And that all evil would fly with it.” He curled his legs into a sitting position. “That is why I must find it. To finally see it destroyed.”

“How? If even The Masters failed?”

He shook his head. “That was their folly. Only a saint can perform a miracle.” He got up slowly from the grass, still wet.

“A saint?” I scoffed. “I have walked this world for two centuries. I have met many strange and wondrous people. Not one of them was a saint.”

“Surely that is a sign, no? That the darkness is rising. For where have they all gone?”

October 21, 2020

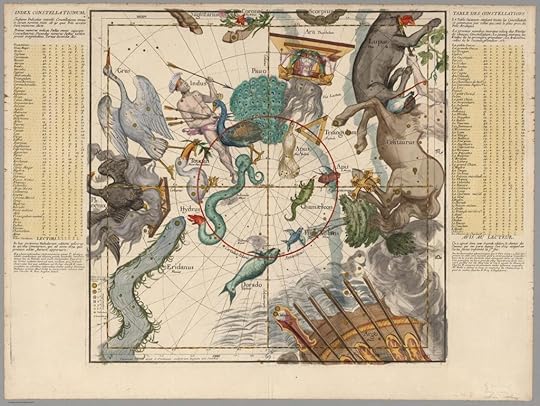

(Art) The Heavens of Ignace-Gaston Pardies

Ignace-Gaston Pardies was a 17th century French Jesuit physical scientist known as an insightful critic of Newton’s early experiments on light and as one of the earliest proponents of a wave theory of light.

Although Pardies was a prolific writer, his star atlas is very rarely mentioned in studies of celestial cartography, which is perplexing, since his Globi coelestis is one of the most pleasing and harmonious star atlases ever published.