Rick Wayne's Blog, page 16

August 7, 2020

The Shape of the Universe

The model described in this article — the “Big Bounce” instead of the Big Bang — is potentially a big deal. It’s merely theoretical at this point and may be discarded in a week, but I believe it’s important to think about all the same.

Quanta Magazine: Big Bounce Simulations Challenge the Big Bang

A full explanation of why would take more time than I have — feel free to throw some patronage my way

(Art) The Cinematic Sci-fi of Friendly Robot

[image error]

The work of French artist François Leroy, AKA Friendly Robot, looks like keyframes from some of the most awesome sci-fi movies never made, including several from the Star Wars universe.

Find more by the artist on his ArtStation page.

August 6, 2020

The Shape of the Universe

The model described in this article — the “Big Bounce” instead of the Big Bang — is potentially a big deal. It’s merely theoretical at this point and may be discarded in a week, but I believe it’s important to think about all the same.

Quanta Magazine: Big Bounce Simulations Challenge the Big Bang

A full explanation of why would take more time than I have — feel free to throw some patronage my way

August 5, 2020

(Art) The Creeping Dread of Stefan Koidl

[image error]

I’ve featured Austrian artist Stefan Koidl before. His “visual horror story” about dark supernatural events at Chernobyl develops similar themes as the rest of his work: that kind of eerie, detached creepiness we feel at the moment we realize something’s not right…

Find more by the artist on his ArtStation page.

August 3, 2020

The Shape of the Universe

The model described in this article — the “Big Bounce” instead of the Big Bang — is potentially a big deal. It’s merely theoretical at this point and may be discarded in a week, but I believe it’s important to think about all the same.

Quanta Magazine: Big Bounce Simulations Challenge the Big Bang

A full explanation of why would take more time than I have — feel free to throw some patronage my way

July 31, 2020

(Fiction) The Winter Bureau

At the start, I was a very poor spy. I lost my first partner to a vampiress. But then, Spurgeon Fount was an awkward man. He had Napoleon’s stature but not his confidence, and like so many of his Victorian peers, was lustful and repressed. The beast we chased traveled under cover of a circus, which is why I had been recruited. Many American circus performers were foreign, lured from across Europe with promises of streets of gold. Thanks to my time with the mizzen, I was handy with a lock pick and a blade, which meant, with some training, I could perform minor feats of escapistry and knife throwing, and with Spurgeon as my handler, I was inserted as an apprentice performer in order to discover the identity of the foul creature, who played some important role for our shadowy adversaries. The vampiress was at least as old as me, and after several months, neither of us could get the better of the other. Alas, I did not take adequate precautions to protect Spurgeon, who was observed sneaking out of my tent and who subsequently met a gruesome end.

I avenged him at least. Our vampiress was a tumbler—quite a difficult woman to pin down. I managed to impale her on a tent pole, but only by throwing her off me, whence I was bitten. I cannot describe what followed since I was not conscious to witness it. For the longest time, two curses waged war within me: one granting me eternal life, the other eternal undeath. It seemed neither could get the better of the other. I was wracked with tremors and night sweats that emerged between long bouts of still coma—seventeen years of it. I was moved to a sanitarium, expenses covered by proxies of The Masters. Mine was a unique case, it seemed. No one in the world knew what would happen—or what to do. Countless learned men came and went at first, like carnival-goers. Gradually, the number dwindled and I became just another curiosity, locked behind a steel door. For many of those years, I was tended by the same nurse. She rose every day to check on me, returned thrice during the day, and once again before bed. My own Florence Nightingale. And yet, I never met her. She was caught with millions of others in the influenza pandemic of 1918.

The man who woke me, who discovered the means to push the eternal battle within me towards the white curse and against the black, was an American. It seemed in those days as if suddenly everyone was American. It didn’t matter whether you were in Paris or Istanbul. They were everywhere, both on the streets and in the news. They invented industrious processes and married European aristocrats and earned incredible fortunes or lost them. They made motion pictures and jazz music and chemicals and machines and war. My American was Professor Henry Hunter, a classicist and scholar of lost magicks. He was not a practitioner. Strictly speaking, he was a magus, and he pursued the conundrum of my case as a kind of intellectual past time, the way a mathematician might become obsessed with an unsolved proof or a detective, a cold case. I was a terrible mystery, it seemed. The sleeping beauty. The woman who could not be roused, who needed neither food nor drink, who simply rested—seemingly forever—in a locked cell at the end of a long hall in a basement floor of a sanitarium.

When I awoke, he was speaking to a nurse.

“Well,” he said, looking down at me through his wire-rimmed spectacles, “there you are.”

It may seem odd to say it, but I hadn’t missed the years, at least not in themselves. I have a surplus of days. They travel quickly in the aggregate but drag in the singular. After a century, one is very much like the next. I would never have minded the ability to fast-forward a bit, to use a modern phrase. Still, it was uncanny the way the world had changed in my absence. I had seen automobiles in London, but they were little more than a novelty, a new way for the rich to spend their fortunes. I had heard a phonograph as well. As a matter of history, Thomas Edison gave one to Madame Helena Blavatsky, whom I accompanied to India. She kept it in the library. The first records didn’t play music. The quality was too poor. Rather, they played random sounds: the honk of a buggy horn, the chirp of a bird, bits of human speech. It was a novelty, something to give the guests a giggle—that noises could be trapped in a box—and after clustering around it excitedly for a week, the bearded gurus and I never touched it again.

But when I finally awoke from my coma, cars choked the streets. Music, once the monopoly of the musician, played from every open window. There were machines to wash clothes, machines to refrigerate food, even machines to send messages through the air. Greater still, our mysterious enemies had launched a major offensive. The result was total war. It had stretched round the globe. Many wizards and millions of civilians had died. I couldn’t believe it. Truly, I thought someone was trying to trick me. It wasn’t until Dr. Hunter brought me stacks of old newspapers that I began to appreciate the scale. It was easy enough to accept that a lone man could be cruel, or a handful of men, perhaps even a nation, but this insanity had engulfed the species. It didn’t seem possible. What had gone wrong?

Dr. Hunter—“Hank” to those who knew him—arranged for me a convalescence at a women’s home run by a religious charity, where I spent many hours reading. I confided in Hank, either by letter or in person, the whole of my life’s story. A cover had been invented for me while I was in a coma. I was said to be a poor girl who had fallen victim to meningitis as a child. I knew that such a disease could affect the mind. After waking from so long a sleep, I needed to say my life out loud, to repeat it continuously if only to prove to myself that it was real, that it had all really happened and hadn’t simply been a dream, as the rest of the world then seemed to be, that I wasn’t Dorothea, a deranged sanitarium girl from Montana, but the immortal daughter of a Russian noble. Some days, it seemed like one had invented the other.

Eventually, when I was well, Hank admitted his own selfish ends. The war had surprised everyone, he explained, even the High Arcane. No one was sure what was coming next. I promise you, the followers of the dark were never stronger, more numerous, or more openly influential than in the early decades of the 20th century. As a result, a new organization had been chartered, of which Hank and I were founding members—a kind of magical intelligence agency operating under Master Crowley, whose public shenanigans were nothing but a means of keeping the public focused on a fantasy, a cartoonish magic, and so away from the truth, even as he carried it out right in front of them.

It was called The Winter Bureau, and its mission was to engage our enemies directly through espionage and subterfuge—even, where necessary, by means of the black arts, which were for all other persons expressly forbidden. Its aim was to discover, in advance this time, the enemy’s secret intents. Dr. Hunter had convinced Master Crowley that I was singularly qualified. I was attractive, he said, and skilled in the social arts, including deception. I spoke five (and two half-) languages, I could pick a lock, use both a knife and a revolver, and quote classic poetry. I had more than a passing knowledge of magic, from books as well as practical experience, not to mention almost no fear of death. Indeed, I could be killed and still return with information. I was, he intoned emphatically, “the perfect spy.”

I remember being somewhat surprised at my own resume as it was recited to me. I felt absolutely no loyalty to my superiors, who had sent me to rot in Everthorn, but I did to the good Dr. Hunter. He was a decent man. An honest man. More than that, he was an optimist, like any good American. Americans do not see the world as it is, which often makes them seem clumsy or naive. Rather, they see the world as they want it to be, which is why they have often been successful in making it so. And in those days, I needed to believe we could win. That the world could go off and get itself into such trouble in my absence made me question my faith in our very humanity. If the 20th century proved anything, it’s that cruelty and rationality were not bitter enemies, as had been assumed since Plato, but in fact the best of friends. I knew that I had no chance of believing we could win, of holding on to hope, anywhere but in the good doctor’s company.

He was certainly a sharp fellow, if a bit bookish, but in a way that you don’t find much anymore. He was an athlete as well as a scholar—a fit, vigorous, studious man who had once rowed competitively for Harvard. He hated guns, but he could throw a punch if need be. He could read and write almost every ancient language, and although enjoyed his old books immensely, never more than people. He didn’t drink, except for the occasion celebratory toast. Yet, if you played the right tune, he would dance like Fred Astaire. If he had a fault, it was most certainly his naivety, which is a poor trait for a spy and one that got us into trouble on numerous occasions. My time with the mizzen aside, I had never thought of myself as particularly deceitful, at least not by nature, but in Hank’s company, it became necessary—even fun—to indulge that side of me. During our many adventures through the radio era, we made quite the pair, a fact we demonstrated to the high society of Berlin on our first mission together. The room practically fell silent as we lightly joined a gala. That is how I remember him, as that dapper young man, hands in the pockets of his jacket, reaching for a cigarette to calm his nerves. He had forgone the wire-frame glasses that night at my request—we were, after all, undercover—and with impaired eyesight, he tripped and fell over a crystal punch bowl at just the right time to avoid getting shot. The crowd broke into screams and we were off on the first of many adventures: Timbuktu, Moscow, Shanghai, Baghdad. Automobiles and radios and airplanes with ghost pilots and boats that descended to a city under the sea.

from the conclusion of my epic urban fantasy FEAST OF SHADOWS.

July 30, 2020

July 28, 2020

(Art) The Dark Angels of Isis Sangaré

[image error]

Swiss artist Isis Sangaré creates dreamy demigods and dark angels of wisdom and horror, similar to the Angelarium of Pete Mohrbacher but with a noticeably darker edge.

Find more by the artist on her ArtStation page.

July 26, 2020

Carnival of Loss

Much of the media we consume is self-consciously mythic, which doesn’t necessarily mean it has swords and wizards, although obviously some of it does. It means it fills the role of myth.

Back before culture was lifted out of space-time, before wrist watches abstracted and idealized time and a money economy abstracted and idealized value, myth-making was so integral to the social order that it was restricted to a special few and the myths themselves were highly conserved. New stories about the Buddha or King Arthur did appear, but often with decades- or centuries-long gaps between, and not without a deep understanding of the canon.

Once myth-making became a commodity, something distanced from the “hegemonic cultural narrative” — the way people in a culture collectively see the world (as linear versus circular, for example) — it is appreciated as superficial. We think we think Game of Thrones is just a book-turned-TV series.

But the cognitive necessity of myth-making means we still appropriate it deeply, even if we don’t think we do. It just doesn’t have a very long half-life. The new myths aren’t so much abandoned as simply fade away like a decaying atom: brief and brilliant life followed by a long and unnoticed senescence. By definition, we aren’t aware of the myths we’ve forgotten, only those near-to, which is why we experience that flash, that epiphany, whenever someone mentions something we haven’t heard in forever. “Ah! I remember that!”

Of course, some myths well and truly die. A rarer few seem to be immortal — or at least incredibly long-lived. Most simply linger. They stop bobbing above the surface and slip unnoticed into the depths of the collective unconscious, where they wait to be stirred.

This is what makes contemporary culture a carnival. Every tent is the most exciting thing — for five minutes. When it’s all over, little of it persists. But it doesn’t entirely disappear.

It is no longer our collective experience of the same carnival, over and over every year, that binds us, as it did in pre-modern societies. Rather, it is our shared experience of many carnivals, the “what-it’s-like-ness” of being a carnival-goer. We’re all fans of something, even if we’re not fans of the same thing.

I don’t wonder if that’s why so many people these days are writers and filmmakers. Yes, I’m sure it helps that the barriers to entry are almost zero, but I suspect people are also attempting to replace something they would have gotten through the antics of Krishna without having to treat a deliberate fantasy as if it were an organic truth. We want others to experience our myths.

If true, it suggests a sort of feed-forward mechanism where, as more and more myths are made, experience of them will be shared by fewer and fewer people, and we will retreat still further into the aether, into narrower and narrower self-made myths, which would further explain why so many people are compulsively self-expressive and yet what they express is loneliness and despair.

So we each sit alone outside our own carnival, waiting for passers-by.

July 24, 2020

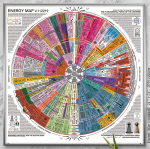

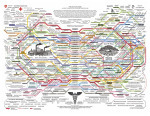

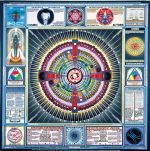

(Art) The Strange Uniformity of Madness II (QAnon)

[image error]

There is a kind of conformity of vision in cognitive nonconformity, which I have pointed out before. It has always suggested to me that, although the content of these people’s beliefs couldn’t be more divergent, their derangement is probably similarly located.

To understand the comparison, you might want to check out that post first. For those who don’t want to make the click, here are a few examples from “outsider artists” Paul Laffoley and Adolf Wofli.

For this update, you also might want to read more about QAnon, a far-right conspiracy group, started in 2017, that believes many Hollywood actors and Democratic politicians are members of an international Satan-worshiping child sex trafficking ring, which overlaps the Deep State and the Illuminati and is opposed only by Donald Trump, who is waging a secret war against them.

The movement looks suspiciously like an alternate reality game, where posts on 4Chan from the group’s anonymous originator, called “Q drops,” periodically trigger a new round of speculation and activity. But there’s no question these folks really believe it. In May of 2018, a QAnon believer occupied a tower in Tuscon cement plant for nine days before police talked him down. He claimed the plant was secretly a child sex-trafficking camp.

The following month, an armed man in an armored vehicle blocked traffic to the Hoover Dam for 90 minutes, demanding that the Justice Department release the “full” OIG report on Hillary Clinton’s private email server. The report had actually been released the day before, but QAnon members believed it had been heavily redacted.

In March of 2019, Staten Island resident Anthony Comello shot Gambino crime family underboss Frank Cali ten times, believing he was a member of the Deep State pedophile ring. At his first court appearance, Comello flashed QAnon symbols and “MAGA forever.”

QAnon beliefs have so many variations and offshoots, and have changed so often, that they’re virtually impossible to summarize, although, as you might expect, they borrow heavily from Christian millenarianism, which has a long history in this country

QAnon may best be understood as an example of what historian Richard Hofstadter called in 1964 “The Paranoid Style in American Politics“, related to religious millenarianism and apocalypticism. The vocabulary of QAnon echoes Christian tropes—for instance “The Storm” (the Genesis flood narrative or Judgement Day), and “The Great Awakening”, which evokes the historical religious Great Awakenings from the early 18th century to the late 20th century. The forthcoming reckoning is said by some QAnon supporters to be a “reverse rapture” which means not only the end of the world as it is now known, but a new beginning as well, with salvation and a utopia on earth for the survivors. [Wikipedia]

Thankfully, a QAnon supporter and former graphic designer who worked in New York’s fashion industry, Dylan Louis Monroe, has created a series of maps to help his fellow believers keep track of it all. For those wanting to go down the rabbit hole, an interview with Monroe on bookseller Sam Jaffe Goldstein’s Substack reads like a piece of contemporary magical-realist short fiction.