Rick Wayne's Blog, page 8

January 27, 2021

We Will Not Invade Cyberspace

Like the early internet, AR is mostly a novelty at this point, such as the London art project in the video below, but the applications are legion. Almost anything humans manipulate in the world, from the commercial (manufacturing, surgery) to the personal (learning a musical instrument, practicing origami), can benefit from in-vision guidance.

(And all that visual data of us doing stuff will be used to virtually train robots to do it better than us. Who’s ready to be operated on by a machine?)

There are now apps that let you see what you will look like older, or with a different hair style or color, what your bedroom would look like with a new floor or coat of paint. This trend will explode. And of course, there’s always the horror story:

But what’s more interesting to me is what AR represents: an invasion of the real world by the digital. This is the opposite of what early sci-fi writers first imagined. Human minds will not jack in and invade cyberspace. Cyberspace will invade us.

Augmented reality will simply become reality. It will be the way we parse and manipulate our environment, which will be increasingly digital and non-local, just as the internet is the way we increasingly interact with people. (It’s already the primary way we find a mate.)

It is ideas that will come to rule. Bits over atoms. And when we can transmute matter, bits will become atoms. Everything we can imagine will become real.

January 26, 2021

(Art) The King Dragons of Jan Ditlev

Besides his colossal wyrms, which positively bleed menace, Danish artist Jan Ditlev’s digital paintings are punctuated with dragonlike forms. His ocean-skimming sci-fi battleships look like dragon heads while the terrestrial and floating pyramids in his desert city seem like teeth in a pair of jaws.

Find more by the artist here.

January 24, 2021

(Fiction) They Eat Humans, Don’t They?

From the air, the planet looked like one continuous hilly park punctuated irregularly by immense tower complexes that reached into low orbit. The surface was almost entirely covered in a continuous manicured lawn that stretched between the deep artificial canyons from which innumerable offices and dwellings hung. Absolutely none of it belonged to the Local Economic Supercluster. They merely rented space on Proebdus, along with half a million other treaty organizations, trade associations, nongovernmental agencies, intergovernmental agencies, think tanks, research institutes, and companies of all kinds, both public and private. It was a bureaucratic haven. There was a small population of natives, but they were not indigenous. There was no indigenous life, apparently, which was why the planet had been lightly terraformed at some point in its past and why nothing grazed on the endless miles of rolling green carpet.

Still, the natives had been so long ago settled that no one remembered where they came from. Genetic analysis suggested they were descended from a now-extinct race of cephalopods that had originated halfway across the galaxy, but if so, no one had any idea how they could’ve arrived on Proebdus so long before discovery of the Strand, nor why their technology was limited to what on Earth would be called early-20th century. It was a mystery, and one Sawyer would’ve liked to investigate—or at least to see—but the delegation’s schedule was set and it seemed the closest she would get was the detour they were taking to an open-air market in the old sector, some 800 kilometers to the northwest, where Allafphallaggia had arranged a photo opportunity to highlight the plight of the human race. It was his hope that a snippet of footage would run on the news ahead of any reports on their testimony from later that day.

The shuttle landed near one of the space towers. Looking up from the landing bay, Sawyer could almost see the docking ring, a massive hemispherical disc resting near-weightless at the top of the enormous column, but the violet Proebdan sky was too hazy to reveal much detail. She did, however, catch a glimpse of the dark, angular Sanhaalen gunship that had apparently been escorting them from high above.

Allafphallaggia led the delegation like a tour guide. They stretched in a chain behind him as they walked along a narrow canal and into the old market. Sawyer had been told to stay behind the generals, but since no one had specified how far, she let herself drift toward the back. Gravity on Proebdus was weaker than on Earth, and she felt certain she could leap over the canal without much effort. But then what? If Allafphallaggia was to be believed, every one of them was a potential target. He had definitely prepared for the worst. The security was unbelievable. It seemed as if every one of the Sanhaalen androids she had seen on the Seabeam had been cloned a dozen or more times, and they formed a biomechanical barrier around the rectangular market, which they were told had been thoroughly scanned for weapons.

Unlike the narrow artificial canyons that meandered across most of the planet’s surface, the squat natural canyon that held the old town was shallow and nearly a mile wide. The structures of the nearby town were visible from the market only as dark shapes poking over the spikes of the “trees,” which had been imported along with every other living thing. The market sat in a depression in the land and was dim. Its dark-metal stalls looked more like something out of colonial Spain than the lost culture of an alien planet. But then, Sawyer supposed, there were only so many ways to economically cast metal into a shelter.

The film crew was already waiting to record the tour, and as the delegation walked down the ramp, floating cameras moved over them, recording their reactions. There was much to take in. The diverse nature of the planet’s business meant that the market sold an unusual variety of foods from around the galaxy. Allafphallaggia stood back and let the delegation be filmed as they wandered in small groups. Samples of fruits and vegetables and things that were not fruits or vegetables were offered at many of the stalls, and some of the delegation were braver than others. Sawyer’s favorite were the betel nuts, which looked somewhat like walnut-sized coconuts but were much easier to peel. Under layers of fibrous husk was a hollow nut encasing a squirming grub. A lobster-sized species of soft-shelled crustacean used a stinger to implant their fertilized eggs inside the green buds of the betel plant, which it also defended. As the nuts ripened, the husks hardened, and the eggs hatched. The grubs ate the nutmeat from the inside, protected by the hard shell, until they were large enough to emerge and fly away. Betel nuts were an Ixct delicacy and popular holiday gift, and they were often boxed like chocolates. If chewed quickly, Sawyer discovered, the unpleasant sensation of a live grub in the mouth could be avoided, and it seemed more like the nuts contained a cream filling vaguely reminiscent of peanut butter. The nutmeat itself was fairly bland but contained a small amount of psychoactive stimulant, as did the leaves of the plant from which it grew, which had been chewed as an analgesic in the time before advanced medicine.

It was surprising, the ambassador explained to Sawyer, how similar clusters of molecules tended to have psychoactive effects on completely diverse species.

She was a prim, smartly dressed, uptight Indian woman, and Sawyer was surprised to note a slight flushing at her temples.

These effects were not identical, the ambassador was quick to note. Gnictarians, for example, had an extreme reaction to betel nuts, whereas she’d read that a few other species had no reaction at all. But for the most part, if a compound was psychoactive on one planet, it was highly likely to be elsewhere as well, which suggested that consciousness, despite its various manifestations across the universe, relied on some base physical characteristics.

“Don’t you think?” she asked Sawyer before peeling and chewing another nut.

The pair of them had had too many, Sawyer decided. The ambassador was getting gabby, and Sawyer was fighting the urge to giggle at the woman, who was getting high on an alien planet only hours before they were scheduled to testify in a last-ditch effort to save the species.

That urge to laugh faded quickly as Allafphallaggia revealed his big surprise. He pulled a tarp from a refrigerated box that displayed one half of a woman’s torso, single breast and all, along with several select cuts from her loins. A hush took the delegation as Sawyer’s Wealing Suit visually translated the sign over the box, which described the contents as “Fatty Human” and “98% Organic.” The sign also promised that any quantity of the meat could be ground for a small surcharge. Suddenly, she wanted to toss the bag of betel nuts she’d bought. She began to feel sick.

“The horror!” Allafphallaggia said. “We see it now as clear as starlight!”

He was laying it on a bit thick, she thought, especially since it was highly likely that to him the butchered corpse looked no different than the cormark meat did to her. (Cormark, she had learned four stalls back, was a kind of multi-armed flying grazer that tasted remarkably like chicken.)

All of the cameras were now focused on Allafphallaggia.

“Here goes any one of us,” he said gravely, pointing to the quartered corpse, “but for our lack of deliciousness.”

“KEELTHI FREEDOM NOW!” an alien shouted before exploding over the market.

Everyone ducked, but it was too late. All those nearby, including Sawyer and the ambassador, were splattered with red-violet Keelthi plasm, which stained both clothes and skin. Fearing an additional threat, a complement of Sanhaalen androids teleported into a circle around the delegation, rifles ready, as most of the market flickered and disappeared. Only the delegation, the androids, a handful of aliens, and a smattering of their wares remained. Everything else had been a hologram, including the human corpse and the three rows of stalls at the back, which apparently did not exist and had been added for effect—to make the market seem bigger and more bustling than it was. In truth, it was a damp, decrepit place and nothing like the vibrant photo opportunity Allafphallaggia and the delegation needed to make an impression on the cosmos.

A small crowd from the old town had gathered at the barrier, and jeers started immediately. A line of aliens of seemingly every possible color and shape pushed against the android wall, which didn’t budge. But they weren’t protesting. They were laughing. As the delegation was hurried back to the waiting shuttle, the angular gunship appeared overhead, as if anticipating trouble. The crowd quieted to a whisper as its shadow fell over them. From the look on her face, Sawyer guessed the ambassador had been in on the ruse. She seemed more disappointed than angry. She was also stumbling slightly, and Sawyer held her arm, which she quickly removed. The betel nuts were wearing off. Dizziness was a common side effect.

Sawyer wiped slime from her face and arms and was thankful her Wealing Suit had prevented her skin from permanently turning an awful shade of red. Responding to a verbal query, her suit explained in words and pictures that the Keelthi were a mostly harmless species of sentient kelp who evolved under conditions of extreme seasonal variability and who underwent an uncontrollable urge to self-immolate whenever their numbers reached a certain size, the same way lemmings will sometimes throw themselves over a cliff or cells in the body will undergo apoptosis for the good of the whole. In a modern context, the urge was maladaptive, and most Keelthi fought it. But just as some humans succumbed to the compunction to over-eat or engaged in risky behavior for sex, immolation was both part of the Keelthi genome and part of their culture. They didn’t even need explosives. They simply inflated an internal elastic sac by gulping air until it finally ruptured with heat and force. According to whatever public database the suit had accessed, the Keelthi were not oppressed, but it was true they did not have a representative government, for every such institution had failed at one time or another in a bout of imitative immolation, and so a council of stable alien races was appointed to oversee Keelthi affairs. Of course, that didn’t stop a handful of zealots from believing in conspiracy and detonating themselves in public places across the galaxy.

“It was the cameras,” Allafphallaggia explained from the front. He had extended his appendages so that he was standing tall over everyone. “I must apologize. We should’ve known better. Publicity acts as a kind of trigger. We’re never the same when we’re watched!”

As she passed near the android barrier, Sawyer caught enough of an echo that her translator module could render some of the alien whispers.

“Humans?” one of them asked. “They eat humans, don’t they?”

Excerpt from my sci-fi short, They Eat Humans, Don’t They?

(Sunday Thought) What is going on?

In simple terms, the world has gotten big. Since I was a child in the early 1970s, the population of the planet has doubled. Imagine a 1970s earth, with all the chaos, all the strife, all the competition for resources. Imagine another right next to it. Now push the two together. That’s today.

At the same time, the world has also gotten small. In the 1970s, if I said “That’s stupid!” to something on the news, the only person who heard it was my spouse, or maybe the guys at the local. Now, everyone everywhere can see it and say “Yeah! That’s stupid!” and start a movement.

This makes it very difficult to make sense of things. Not only are many more things happening, we are aware of them faster, which inundates and overwhelms the legacy institutions we built to share and make sense of the world: universities, news organizations, and the like.

So if it seems like no one knows what’s going on, it’s because no one does. We have surpassed our collective ability to make sense of things.

But our brains keep trying.

Even if we know the world doesn’t make sense, we are unable to “turn off” the urge to find patterns and meaning, just as we can’t “turn off” the feeling of thirst or hunger. We can’t even temporarily satiate it, which is why even smart people fall for dumb things.

This leaves us vulnerable to exploitation. Ad-based information distribution like cable news and social media makes money on volume. More viewers = more cash. In other words, they have no incentive to restrict themselves to the truth versus some mix of truth and lie.

Neither do individual humans, by the way. If I invent a story and people believe it and share it widely, then I get likes and status. More viewers = more status. This is how social apes naturally behave.

This was true of old-timey gossips and newspapers as well. (Hence the phrase “yellow journalism.”) The reason few people mistook The National Enquirer for news was because it was clearly disconnected from what the institutions of sense-making agreed was true.

That benchmark is gone. At the same time, the scope of what’s possible has increased. Every crazy thing that happens in the world is instantly available to me, so my sense of what’s reasonable or just possible is wider.

We see this in relatively benign topics like UFOs, which have entered the mainstream consciousness as they never could’ve in 1970. We’re willing to contemplate more possibilities.

That also means that some platforms can claim Russiagate without any real evidence and people will believe it, and other platforms can claim Electiongate without any real evidence and people will believe it. (Or at least get very, very suspicious.)

This will get worse, and not simply because the information distributors have no incentive to fix it. They can’t. Making them apply labels or remove false posts assumes there is some benchmark to compare them to. If so, why don’t we just go there directly??

I’m being serious. What basically infallible repository of facts is the junior analyst at the tech company comparing a post to such that she knows whether it’s true or false? And where is it?

Truth is, it’s just another news source, which means what’s at stake here is which news source gets the seal of approval from the largest corporations in history to be peddled and remarketed as “the truth.”

Contemplate the global financial incentive there.

You are not simply being misinformed. You are being baited. You are the enemy in someone else’s world view. The more you act out that role, the more you threaten to riot or silence others, the more you can be monetized — to keep someone else nervously glued to their screen.

I’ll leave you with a rule of thumb. If the information you’re consuming makes you angry or scared, if it tells you there are enemies behind every bush waiting to hurt you, it’s probably a limbic hack. For the most part, real news is boring.

(Morning Thought) What is going on?

In simple terms, the world has gotten big. Since I was a child in the early 1970s, the population of the planet has doubled. Imagine a 1970s earth, with all the chaos, all the strife, all the competition for resources. Imagine another right next to it. Now push the two together. That’s today.

At the same time, the world has also gotten small. In the 1970s, if I said “That’s stupid!” to something on the news, the only person who heard it was my spouse, or maybe the guys at the local. Now, everyone everywhere can see it and say “Yeah! That’s stupid!” and start a movement.

This makes it very difficult to make sense of things. Not only are many more things happening, we are aware of them faster, which inundates and overwhelms the legacy institutions we built to share and make sense of the world: universities, news organizations, and the like.

So if it seems like no one knows what’s going on, it’s because no one does. We have surpassed our collective ability to make sense of things.

But our brains keep trying.

Even if we know the world doesn’t make sense, we are unable to “turn off” the urge to find patterns and meaning, just as we can’t “turn off” the feeling of thirst or hunger. We can’t even temporarily satiate it, which is why even smart people fall for dumb things.

This leaves us vulnerable to exploitation. Ad-based information distribution like cable news and social media makes money on volume. More viewers = more cash. In other words, they have no incentive to restrict themselves to the truth versus some mix of truth and lie.

Neither do individual humans, by the way. If I invent a story and people believe it and share it widely, then I get likes and status. More viewers = more status. This is how social apes naturally behave.

This was true of old-timey gossips and newspapers as well. (Hence the phrase “yellow journalism.”) The reason few people mistook The National Enquirer for news was because it was clearly disconnected from what the institutions of sense-making agreed was true.

That benchmark is gone. At the same time, the scope of what’s possible has increased. Every crazy thing that happens in the world is instantly available to me, so my sense of what’s reasonable or just possible is wider.

We see this in relatively benign topics like UFOs, which have entered the mainstream consciousness as they never could’ve in 1970. We’re willing to contemplate more possibilities.

That also means that some platforms can claim Russiagate without any real evidence and people will believe it, and other platforms can claim Electiongate without any real evidence and people will believe it. (Or at least get very, very suspicious.)

This will get worse, and not simply because the information distributors have no incentive to fix it. They can’t. Making them apply labels or remove false posts assumes there is some benchmark to compare them to. If so, why don’t we just go there directly??

I’m being serious. What basically infallible repository of facts is the junior analyst at the tech company comparing a post to such that she knows whether it’s true or false? And where is it?

Truth is, it’s just another news source, which means what’s at stake here is which news source gets the seal of approval from the largest corporations in history to be peddled and remarketed as “the truth.”

Contemplate the global financial incentive there.

You are not simply being misinformed. You are being baited. You are the enemy in someone else’s world view. The more you act out that role, the more you threaten to riot or silence others, the more you can be monetized — to keep someone else nervously glued to their screen.

I’ll leave you with a rule of thumb. If the information you’re consuming makes you angry or scared, if it tells you there are enemies behind every bush waiting to hurt you, it’s probably a limbic hack. For the most part, real news is boring.

January 22, 2021

(Art) The Hi-Tech Wastelands of Ignacio Bazan-Lazcano

The illustrations of Ignacio Bazan-Lazcano depict grungy hi-tech frontiers pitted with dust and danger. Sometimes post-apocalyptic, always remote, many of his works look like something out of Mad Max. His subjects are rebels and explorers fleeing the center or returning to conquer it.

Find more by the artist on here.

January 20, 2021

What is going on?

In simple terms, the world has gotten big. Since I was a child in the early 1970s, the population of the planet has doubled. Imagine a 1970s earth, with all the chaos, all the strife, all the competition for resources. Imagine another right next to it. Now push the two together. That’s today.

At the same time, the world has also gotten small. In the 1970s, if I said “That’s stupid!” to something on the news, the only person who heard it was my spouse, or maybe the guys at the local. Now, everyone everywhere can see it and say “Yeah! That’s stupid!” and start a movement.

This makes it very difficult to make sense of things. Not only are many more things happening, we are aware of them faster, which inundates and overwhelms the legacy institutions we built to share and make sense of the world: universities, news organizations, and the like.

So if it seems like no one knows what’s going on, it’s because no one does. We have surpassed our collective ability to make sense of things.

But our brains keep trying.

Even if we know the world doesn’t make sense, we are unable to “turn off” the urge to find patterns and meaning, just as we can’t “turn off” the feeling of thirst or hunger. We can’t even temporarily satiate it, which is why even smart people fall for dumb things.

This leaves us vulnerable to exploitation. Ad-based information distribution like cable news and social media makes money on volume. More viewers = more cash. In other words, they have no incentive to restrict themselves to the truth versus some mix of truth and lie.

Neither do individual humans, by the way. If I invent a story and people believe it and share it widely, then I get likes and status. More viewers = more status. This is how social apes naturally behave.

This was true of old-timey gossips and newspapers as well. (Hence the phrase “yellow journalism.”) The reason few people mistook The National Enquirer for news was because it was clearly disconnected from what the institutions of sense-making agreed was true.

That benchmark is gone. At the same time, the scope of what’s possible has increased. Every crazy thing that happens in the world is instantly available to me, so my sense of what’s reasonable or just possible is wider.

We see this in relatively benign topics like UFOs, which have entered the mainstream consciousness as they never could’ve in 1970. We’re willing to contemplate more possibilities.

That also means that some platforms can claim Russiagate without any real evidence and people will believe it, and other platforms can claim Electiongate without any real evidence and people will believe it. (Or at least get very, very suspicious.)

This will get worse, and not simply because the information distributors have no incentive to fix it. They can’t. Making them apply labels or remove false posts assumes there is some benchmark to compare them to. If so, why don’t we just go there directly??

I’m being serious. What basically infallible repository of facts is the junior analyst at the tech company comparing a post to such that she knows whether it’s true or false? And where is it?

Truth is, it’s just another news source, which means what’s at stake here is which news source gets the seal of approval from the largest corporations in history to be peddled and remarketed as “the truth.”

Contemplate the global financial incentive there.

You are not simply being misinformed. You are being baited. You are the enemy in someone else’s world view. The more you act out that role, the more you threaten to riot or silence others, the more you can be monetized — to keep someone else nervously glued to their screen.

I’ll leave you with a rule of thumb. If the information you’re consuming makes you angry or scared, if it tells you there are enemies behind every bush waiting to hurt you, it’s probably a limbic hack. For the most part, real news is boring.

January 18, 2021

(Art) The Dark Towers of Reza Afshar

Iranian artist Reza Afshar creates stunning towers and dark fantasy scenes from pop culture and his own imagination. One could easily see these as book covers.

Find more by the artist on his ArtStation page.

January 17, 2021

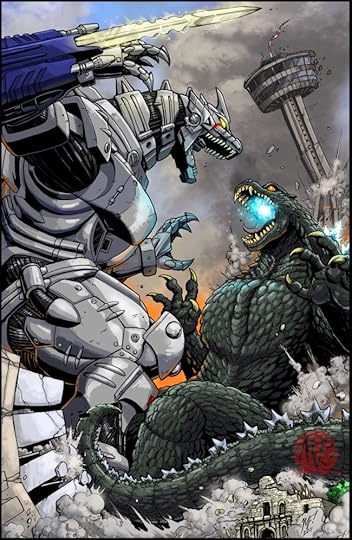

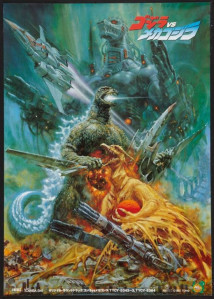

Let Them Fight: Godzilla and Mythic Symbolism

I grew up on Godzilla movies. Well, I grew up on a lot of TV, but those too. As a kid, I often didn’t understand them — some of the plots are pretty outrageous — but I was mesmerized by the imagery, so much so that I put a battle between a giant monster and its robot doppelganger at the end of my first book, Fantasmagoria.

That was more than rabid fandom. (Everything I do in my books I do for a reason.) Godzilla is not just another Cold War-era cinematic monstrosity, like The Blob or Them! or The Thing. He is the latest in a long line of elemental giant beasts from the depths, including Cthulhu, Grendel, the Kraken, the Leviathan of the Bible, and so on, going all the way back to Tiamat, if you know your Sumerian mythology.

“Depths,” by the way, doesn’t have to be the ocean, or even deep space. It can also be the subconscious, a cave, a lost island (or planet), the Negative Zone, or any extra-human void. They are the unknowable chaos — marked “Here Be Dragons” on any old map — that exist outside our ken and which must be tamed for human society to flourish, but not destroyed, for they represent the essential vitality to which we must forever return.

In the old days, we were only ever one drought away from starvation. A swarm of locusts could descend at any time. Or a new plague. Or barbarians. Indeed, for most of civilization’s history, it was the exception rather than the rule, and our best chance of survival was to turn forest into field. Man over nature. Thus, in the earliest recorded creation myth, Marduk, the sky-god (the order of the cosmos), slays the monster-from-the-depths, Tiamat (the chaos from the void) — a story the Sumerians retold and honored as part of every annual cycle.

In our era, where civilization isn’t quite so tenuous, this same symbolism manifests as the psyche in stories like Frankenstein. What does the eponymous doctor do if not summon his monster from the literal unknown, like a sorcerer? Or Poseidon summoning the Kraken? And the beast consumes him. In the Lovecraftian mythos, which challenges our very sanity, the Old Ones are never more than one wrong turn of a key from returning from the void to destroy us.

Whatever else you might say about the 1998 Hollywood production of Godzilla, it was not actually a Godzilla movie, not because it didn’t feature a giant lizard stomping on a major city but because it ignored the fantastical, mythical elements in favor of a veneer of realism. The creature of that movie is a mutated iguana. No more. No less. It doesn’t breathe nuclear fire. It has no motivation save the mechanical urges of survival and reproduction. And it’s destroyed by a couple F-16s. A tornado would’ve been a bigger threat.

In his sixty-plus-year history, the big guy has been both friend and foe, but the best movies, in my opinion, portray him as neither hero nor villain — merely a force of nature and just as unpredictable. An earthquake or tsunami isn’t evil. It isn’t out to get you. But it is violent and destructive as it erupts from the depths and it may take everything from you, including your life. No matter how hard you try, you can’t beat it. You can only endure.

Fanboys like me frost our shorts when Godzilla — not good, not evil, just indomitable — is turned against a force that is evil… such as aliens trying to conquer the earth or some mad scientist’s experiment gone awry. Humanity may marvel at our ingenuity when we lure Godzilla into a volcano and bury him, but we’re kicking ourselves a few months later when a flying saucer drops King Ghidorah from its belly.

Three-headed space dragon. Aw, fuck.

Lucky for us, not even a volcano can hold back a god, the unconquerable and capricious force of nature manifest on two legs. Alien, meet Mother Nature’s bodyguard.

But I did not return from my first trip to Japan with a Ghidorah toy. Or Rodan. Or Mothra. I came back with Godzilla and his nemesis, his true opposite: MechaGodzilla. The machine — the logical invention — is the perfect symbolic counterpart to the monster, like Gilgamesh and Enkidu, Beowulf and Grendel, Bruce Banner and the Hulk, or even Batman and the Joker. Their battles are ours, individual and society.

In the original Toho movie arc from the 70s, MechaGodzilla was built by a race of invading aliens specifically to kill the king of the monsters, who was the only creature that could stop them from taking over the earth. Here we see anxieties about the enslaving power of technology, which turns us all into numbers, wage slaves, interchangeable parts. We are rescued by our invigorating animal soul.

In the 90s-era reboots, at the dawn of the internet and all its promise (before it became the Eye of Sauron), “MechaG” was built by the human race to resist Godzilla after he destroyed Moguera, our first attempt at a robotic counterthreat. While the machine doesn’t succeed — it can’t because Godzilla is that which also animates us — it is successful at driving him back to the depths… for now.

However else it might save us, our animal soul must also be kept in check. Too little, and we become a machine. Too much, and civilization is lost to chaos.

And now I will go back to playing with my toys.

posing with the missus

we want the funk. give us the funk.

the big guy about to lay it down on the smog monster

you heard me! i said you can suck it!

January 15, 2021

(Art) My Dystopian Library – Pt. 4

At this point, I seem unable to stop myself!