Rick Wayne's Blog, page 67

October 23, 2018

(Fiction) Granny Tuesday

Rock salt crunched underfoot as I approached the door, which was odd seeing as how it was only fall. The weather had definitely turned chilly but not nearly enough for a freeze. It wasn’t until I had my hand on the handle that I realized the salt hadn’t been sprinkled on the walk so much as painted across it. There was a fat line, as if some lazy janitor had simply circled the building with his push dispenser and called it a day.

I opened the door marked “Enter” and the scent hit me before I even crossed the threshold—that tart, sour aroma of old people. The place reeked of it. Not even the heavy dose of deodorizing disinfectant could mask it. Beyond was a short hall sealed by a glass inner door, over which hung a few heads of garlic tied to a bunch of dried wildflowers. I recognized them as adderwort, although I had no idea why such a thing would be there, let alone why it hung in front of a small round reflective mosaic made from the irregular pieces of a shattered mirror. I tried the handle, but the door was locked. I had to be buzzed into the lobby from the nurses’ station, which was thankfully in clear view of the glass. I must have looked harmless because a thin nurse with bags under her eyes hit the button. Inside, fluorescent tubes hung from the ceiling in rectangular plastic casings. The walls were block concrete painted piss yellow. A waist-high rim of scuff marks dotted the hall ahead of me, made by the gurneys and wheelchairs the staff and residents had left sitting about. The floor was speckled linoleum tile buffed to such a shine that it made my shoes squeak.

I walked to the nurses’ desk and waited for one of the women to acknowledge me. Synthesized bossa nova played over the ceiling speakers. A pair of double-sided filing shelves stuffed with color-tabbed folders filled a nook behind the desk. I glanced to the women, but they ignored me.

To my left, across from the exit door, was a waiting area with a handful of sullen and silent occupants. A cork bulletin board on the wall was stuffed with community odds and ends. Brochures and announcements hung off it at every angle. To my right was some kind of common room. The door was only cracked open. A white-shirted orderly, who looked like the middle linebacker for an inner city high school, stood dead-eyed in front of a locked glass case, like he was guarding the Resident of the Month display: Mrs. Bodkin was too sick to smile for the picture of her hanging on the other side of the glass. She had an oxygen mask over her mouth and nose and her eyes were half closed.

The guard caught me looking. There was something terribly wrong with his eyes.

“Can I help you?”

The nurse had no expression. She was dead-eyed with heavy bags under her sockets. A machine would’ve had more charisma.

“Yes, I’m here to see—” I paused. Suddenly it seemed dumb to say her name out loud.

“She already has a visitor,” the woman said, turning to multi-task on her computer. “Are you buying or selling?”

The question took me aback. “Selling.”

“You can wait over there.” She pointed to the rows of white plastic seats with chrome legs.

I sat in one. I looked around. The staff were busy with paperwork. Occasionally the phones rang. A few seats down from me, a woman with a lisp tried to calm whatever wheezing beast was inside the collapsible pet carrier on her lap. When she saw me looking, she pulled the drape over the front. On the other side of the chairs, a goth girl all of sixteen sat biting her nails, which were already torn. She was engrossed in her phone. I wished I had mine.

I took out my instructions and read them again—not because I’d forgotten, or even that I was worried, so much as I just didn’t have anything else to do. I read them seven times.

Accept no bargain.

I folded the paper and put it back in my pocket. I sat. I read every sign visible from my seat and discovered that the John D. was proudly Medicare- and HIPAA-compliant. It was an hour or so before a nurse in blue scrubs and a short white coat came to get me.

“Selling?” she asked, as if that were my name.

I nodded. I’d been half-asleep. In my stupor, I hadn’t noticed the young girl leave.

“She’ll see you now.”

I followed the nurse down the hall to a T-intersection. Ahead was the rear exit, facing what looked like the staff parking lot. To my right and left were identical halls filled with patient rooms. There was a dark round knob above each door with the room number painted on both sides. It wasn’t until we turned left that I noticed one of the knobs was darkly lit, like a black light, indicating the patient in that room required attention. I peeked in as I passed and saw a shriveled man in an oxygen mask reaching out to me with his eyes as he panted for breath.

They were all like that, every one in every room, motionless and dying. That’s what the John D. Bailey Center was for: palliative care—attending to the pain and symptoms but not the disease, which I guessed in every case was terminal.

As we neared to the end of the hall, the piss-yellow block walls sprouted a constellation of butterfly shapes, each a different size and color—probably someone’s earnest attempt to “liven up the place.” A couple businessmen in drab suits walked past the butterflies, heading toward the front. They seemed so out of place. The taller one was visibly distraught. His companion was more resigned, like he’d gotten the same devastating news but would wait until later to deal. Whatever it was, it consumed them. They didn’t even notice me.

I was shown to a room opposite another enclosed staircase and was asked to wait inside. I saw an overstuffed bookshelf, a side table, and a rolling kitchen stand, all covered in bric-a-brac. There was a love seat in front of a glass oval coffee table topped only by a Mason jar sprouting half-dead flowers. Vintage Americana adorned the walls in red, white, and blue. There was a bronze statue of a ballet dancer, about a foot high, on the ledge of the bookshelf next to a treasure chest—shaped box, no more than five inches across. The lid was open. Inside was a pile of jagged, irregular stones. They were lobed and pocked like old coral. But they weren’t coral. They weren’t rock either.

“Don’t touch!”

My hand froze.

An old woman with gnarled skin and wild hair rolled into the room in a wheelchair. There was a green oxygen tank fixed to the back and a plastic mask trapped in a tangle of tubes. She wore a simple white apron over a calico dress. Her feet were covered in scuffed leather work boots too heavy for her sticklike legs, one of which dragged on the ground like a rudder as she rolled. I smelled tobacco and anise.

“Nettlestones,” she explained. Her face was gaunt and wrinkled like elephant hide.

“Nettlestones?” I’d never heard of such a thing.

“Where d’ya think gargoyles come from?” she asked. She pointed a shaky, bony finger. “Get one of those under you and you’ll spend the next few years watching horns and callouses grow outta every patch of skin.”

I turned back to the box. The irregularly shaped contents looked more like tree bark than anything, but denser and sharp. Easy to cut yourself.

“They was like lepers in the old days. Didn’t have nowhere to go, so the churches took ’em. In return, the miserable sots sat the night watch and kept an eye on things while the old vicars slept. Them carvings on the cathedrals were a just warning. Beware of Dog so to speak.”

Without so much as a pause for breath, she barked the words “Ground rules!” She held up three gnarled, arthritic fingers attached to a visibly trembling hand. “Rule number one, mind your manners.” She closed one finger. “Rule number two, speak when you’re spoken to. Don’t make me guess. I’m not a mind reader.” She closed another finger. “And number three, keep your seat and don’t make any sudden moves. I’m old and jumpy.” She motioned to the love seat with flower-print fabric. “Manage those and we’ll get on just fine.”

With her terms set, Granny Tuesday paddled with her foot to the messy work table at the back of the space. I didn’t see a bed. Old-timey lace curtains covered windows on two sides.

“Now, what can I do for you?” she asked.

“It’s the other way around, actually. I’m told I have something you might want.”

“Alright,” she said without a hitch. “Let’s see it.” She situated herself facing me and locked one of the wheels of her chair. Her osteoporosis was bad enough that her spine curled forward a little, which meant she hunched slightly in the chair. But her eyes twinkled like she was about to tell you a joke.

I took out the coin and held it up between my thumb and forefinger, unsure what to expect.

The old woman popped the wheel lock immediately and made like she was going to move toward it, which surprised me. I took the chef’s advice and slipped it back into my pocket.

She sat back. “Well, now . . . That is something. That is something indeed.” There was a long pause. “I don’t suppose you wanna tell me where you acquired that silver?”

“It was given to me.”

“By?”

“A friend.”

“Ahtt!” She shook a finger at the floor in front of the doorway. She paddled forward with her foot and leaned over so far she had to hold her breath. She came up with something pinched between her thumb and forefinger. She held it up for me to see.

I squinted without moving for a closer look. It looked like a stray hair from my beard, which I immediately rubbed to make sure it was clean.

“Lookit that,” she said. “And the staff here do such a good job keepin’ things tidy.”

It was true. The place was freakily spotless.

She threw me the briefest of disapproving glances before rolling toward the waste bin under the table. “Have we met?” she asked with her back turned.

“I don’t think so.”

She contemplated her next question. “You were asked to keep your seat,” she said.

“Ah,” I said apologetically. I was still standing. I sat on the love seat in front of the coffee table.

Granny noticed the wilted flowers in the screw-top Mason jar. “Where’re you from, sonny?”

“Atlanta.”

She paddled forward with her rudder foot and removed the dripping plants. “Bah! Your roots, boy,” she said brandishing the stems. “You can cut them all you like but you never grow new ones. Where’re your roots?” She dumped the water on the floor, spat, and replaced the jar on the coffee table.

I looked at the puddle on the flat carpet. “I’d appreciate it if you didn’t call me boy,” I said before adding the word “Ma’am.”

“I ain’t mean nuthin’ by it.” She turned about and tossed the flowers in the trash. Half of them made it. “Just a word.”

“Not where I’m from.” I tried to sound polite. Nonconfrontational. Like you do in those situations.

“Fair enough. So what do I call ya?”

“Most people call me Dr. Alexander,” I explained.

“I see. And how many letters you got after your name, Doc?”

“Does it matter?”

“How many?” she insisted.

“Five.”

“And what are they?”

“MA and PhD.”

She leaned toward me. “Know how many letters I got after my name?”

“No, ma’am.”

“All of ’em.” Her short laugh was half cackle, half shriek.

Granny Tuesday leaned over in her chair, straining to reach the screw-top jar without having to roll herself closer to the coffee table.

“Can I help?”

“I got it,” she insisted. She lunged once, then twice, just managing to hook two fingers over the lip. She pulled it toward her. “There!” She moved the empty jar to the work table and wiped her fingers on her smock. “You were born in the hills, weren’tcha?”

I nodded. “Asheville. Why do you ask?”

“Well, ain’t that grand!” she exclaimed. “We’re practically kin! I’m from just up the road. Little house in the woods outside a’ Johnson City, Tennessee. Weren’t but a hour between us as the crow flies. Ain’t that something.”

“We’re a long way from home,” I said, making polite conversation.

“Yes, sir.” She nodded. “Have to go where we’re needed though, don’t we?”

The white-shirted orderly, the one I’d seen up front, stepped into the room with fresh flowers in a clean, water-filled Mason jar. His eyes were frosted. He didn’t say anything. He set the flowers on the coffee table in front of me and left. It was a full bunch, and the unusually large, striped blossoms completely blocked my view of my host.

“About that silver,” she said.

I shifted sideways in my seat so I could get up without knocking over the coffee table.

Granny lifted a piece of hard candy from a dish and put it in her mouth. She offered me the dish, which shook with her hands. I remembered my instructions.

Let nothing pass your lips. Accept neither food nor drink.

I declined with a wave. I stood and walked around the love seat.

“You were asked to keep your seat,” she said, knocking that candy around her teeth.

“I’d prefer to stand. If it’s alright with you.”

“You don’t want to parlay with me, Doc? And here I thought we was becomin’ friends.”

“I hope so,” I said with mock earnestness. “I wouldn’t want to think you were trying to take advantage of me, Granny.”

“Now, now,” she said calmly. “You were asked kindly to keep your manners.” She bit the candy. I heard it crack. “And your seat.”

“Why?” I asked. “So I can get giddy off the scent of the flowers and end up agreeing to something I shouldn’t?” I pointed. “Hyoscyamus niger. Commonly known as black henbane. Wouldn’t have remembered it if not for those distinctive striations. But then, poisonous flowers are a little like poisonous snakes.” I was looking squarely at her. “A deterrent does no good if you don’t advertise.”

Granny Tuesday smiled. She sat back in her wheelchair and relaxed for the first time. She even lifted her heavy rudder boot onto the footplate. But her hands were still shaking and she crossed them in her lap.

“You know what, Doc? I think I like you. A good Southern boy ain’t no fool. Excuse me. Southern man.” She waved a hand at the coffee table. “Go ahead and move those flowers outta there and no hard feelings.”

“I’m alright,” I said without moving. I looked very closely at my host. She sat patiently as if for a portrait. “You a hustler, Granny?”

“That’s a rude word and I don’t like it. I ain’t gonna warn you again to mind your manners.”

I leaned back against the bookcase and crossed my arms. “It’s just a word,” I said, copying my host. “I didn’t mean nothing by it. I’m kinda impressed, actually. Woman of your age and all.”

Granny squeezed her hands together as if she was frustrated with them. She turned her chair and paddled with her foot to a floor basket on her right. “And how old do you think I am?”

I shrugged and she put the smile back on her face as she reached into the basket and pulled out a short strip of twine from a bunch. It was brown and fuzzy.

“Do you mind?” She raised a hand to advertise her tremors. “I know it’s rude but it helps if they have something to keep them occupied.”

I motioned for her to proceed.

“Thankya.” With hands shaking like an unbalanced washing machine, Granny Tuesday tucked one end of the twine under the other and pulled a knot tight. She tugged the ends a couple times to test it, which seemed to satisfy her.

“All that’s just business,” she said, nodding to the henbane. “That’s what I am, a businesswoman. So how about you and me get down to business? How much for the penny?”

“How much are you offering?” I said, playing the chef’s game, as instructed.

“Well . . .” She ruminated as she tied a second knot, “Seein’ as how we’re just passin’ by the bye and don’t know each other right well, I imagine you’ll have to tell me what you want.”

I had the sense that if I suggested something in trade, anything at all, no matter how fanciful—a pot of gold, the method for cold fusion, the Empire State Building—Granny Tuesday would’ve immediately spat in her hand, slapped her knee, and shouted the word “Deal!” and I would have blundered right into whatever trap the chef had warned me to avoid.

I contemplated my response as she kept her shaking hands busy with the string.

“Oh, poo,” she breathed. “I used to be able to tie one a’ these in a hot second. Now look at me. Shakin’ like a pastor in a whore house.”

“Can I help?” I asked, buying myself a little time.

“No, no,” she said with a sigh. “It don’t help my hands none if yours do all the work.” She tugged another knot tight, this time with a grimace. “So?” she asked. “What can Granny do for you? Seems to me it has to be a mighty fine thing in trade.” She nodded to the coin in my pocket.

I went to shift my weight, as you do after you realize you’ve been leaning in the same spot for a while, but instead of obeying my command, my right foot sat like a cannon ball and I lost my balance and fell sideways to the carpet. My cheek fell in the puddle of henbane water she’d dumped earlier. I could smell the sap—sticky and sweet.

I tried to get up, but I couldn’t move. I had such a bad Charlie horse in my back that I couldn’t do anything but lie on the ground and hold myself as stiff as a board, breathing in shallow gasps. It hurt.

“By knot of one,” Granny Tuesday chuckled as she turned the twine between her fingers like a rosary. “The spell’s begun.”

She stood from her wheelchair, shakily. “By knot of two, it cometh true.” She walked toward me slowly, singing the words. “By knot of three, so mote it be.”

I watched her spindly legs lift those heavy boots in awkward shuffling steps. She still had the twine in her hand. “By knot of four, my powers roar. By knot of five, the spell’s alive.”

When finally she was over me, I could see a series of irregularly-spaced knots in the cord. She dangled the line in front of my eyes for a better look. The first knot bound my beard hair, black and curly.

“By knot of six,” she cackled, “it’s you I fix. By knot of seven, you pray to heaven. By knot of eight, comes your fate.”

I babbled in protest as Granny leaned against the nearby love seat and she tied the final knot, hands still shaking like running motors. Then, with a single hand to brace her, she bent down with a grunt.

“By knot of nine, what’s yours”—she reached into my pocket with fumbling fingers—“is mine.” She took the coin.

Granny Tuesday flipped the tarnished silver and caught it in the air with surprisingly steady hands.

She stood over me and held her prize between her thumb and forefinger. “I’ve been after this penny for nigh on seventy years,” she said. She slipped it into the pocket of her apron and tapped it. “And here you just waltz in with it, like you found it on the street. It’s fishy, mister. Now hows about you tell ol’ Granny the truth?”

I could barely move, and that included my throat.

“Righty.” She stood straight. “Guess’n you’ll hafta be my guest for a spell. Some time in the garden, I think, will straighten you out.”

She turned to a pair of white-shirted orderlies, including the linebacker-looking kid who had brought the henbane. Neither of them spoke.

“Virgil. Horace. Take this fella out to the garden and see that he gets all fixed up.”

snippet from the first course of my forthcoming five-course occult mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS.

Each of the five courses is a separate mystery, although together they tell the story of the protagonist, a shaman-chef, who is never the narrator.

cover image by Yuliya Litvinov

October 22, 2018

Well of Enigmas

The first image is “Forty-Two Kids” (1907) by American painter George Bellows.

The second image is 10,000-year-old art from the “Cave of Swimmers” in Gilf Kebir on the Egyptian-Sudanese border, discovered in 1933.

[image error] [image error]

Over the weekend, one of my nieces left food in the trash and this morning I awoke to a miniature invasion. A horde of red-eyed fruit flies huddled around the lip of the wine glass I had left near the sink, as if mesmerized by it.

In cold and dark, humans similarly huddle around the light and warmth of a fire. But when we are not so oppressed, when we are free, people on all continents and in all times gather spontaneously around wells, springs, waterfalls, lakes, ponds, rivers, and watering holes, even when there are closer sources of food and water.

The ocean, seemingly boundless, is undrinkable and seems to repel us with its waves and storms. Standing before it is like standing before an uncaring god.

But fresh water is the source of life. We emerge from it. Each of us was born from a tiny pool inside our mother, which of course is the origin of baptism and holy cleansing, which offers a kind of rebirth.

Fresh water is both still and in motion, and we can see our reflection on its surface. In that, it is both inviting and dangerous, for it is impossible to know what dangers lurk underneath: the nymphs and nix.

Vivienne, the Lady of the Lake, was Merlin’s undoing. Like an insect to the candle flame, he could not escape his fascination with the magical and otherworldly and so was entombed there.

That danger compels us. We get drunk on holiday and dive from high rocks. Children launch themselves from rope swings.

I suppose that’s why there’s something saccharine and sterile about chlorine pools and their plastic verge and why young children hover at the edge of the watering hole before taking their very first step. Thence comes the crocodile to pull us to our death.

Mirror, portal, prison, font of life, eternal rest — we stand round it, entranced.

cover image: “Swimming Hole” by Jonathan Wateridge (British, b.1972)

October 21, 2018

The one writer worse than you

Before his death, Timothy Dexter was hailed as the worst writer of all time.

Born in 1748 to a poor working family in the British colony of Massachusetts, Dexter took to the fields around age 8 and never received much of an education. By chance, he married a wealthy widow whose equally wealthy friends liked to make fun of him for being a “plain-spoken man” — which is to say, a man lacking refinement: a wide-mouthed asshole.

And he was. Timothy Dexter had opinions on everything, usually quite awful, and his wife’s friends, being narrow-mouthed assholes, liked to tease him with terrible business advice on the hopes that it might “teach him a lesson.”

They told him to ship coal to Newcastle, for example, which was a major coal producer. So he did. It arrived shortly before a coal miner’s strike, and he sold it at a profit.

They told him to ship winter gloves to the Caribbean islands. So he did, where he sold them to Asian sailors on their way to Siberia.

He sold bed-warmers as molasses ladles, Bibles to missionaries, and invested foolishly in a near-worthless “Continental currency” — which expanded his fortune again when, against everyone’s best predictions, the American colonists defeated the most powerful empire in the world.

Dexter built a mansion, which later became a hotel, and filled the grounds with statues of great men of the age: George Washington, Napoleon Bonaparte, and himself. But try as he might, he could never win the respect of the upper class, who found his arrogance and vulgar opinions distasteful.

At one point, he faked his own death just to see who would show up at his funeral. When he noted his wife wasn’t crying, he leapt forth immediately, revealing the hoax, and took a cane to her.

At the age of 50, after amassing a fortune, Timothy Dexter decided he would write a book — about himself. “A Pickle for the Knowing Ones, or Plain Truth in a Homespun Dress” ran to a mere 8,000-and-some words, an essay by modern standards, and was nothing but one long gripe: about politicians, about the clergy, about foreigners, and about his wife, without whose fortune he would have stayed a very poor man.

But the little book’s most notable quality, that for which it is best remembered, was that through all 33,864 letters, there was not a single punctuation mark. No periods. No commas. Nothing. There wasn’t even regular capitalization.

Dexter paid for the printing himself and handed the book out for free, just like any good indie author today. But following the same ridiculous luck he’d experienced his entire life, the damned thing took off, and Timothy Dexter’s tiny monstrosity ran through eight separate printings, despite widespread criticism from the literati that the lack of punctuation made it a grade-school farce.

Alas, the great public beast eats what it wants.

Dexter responded to his critics in typical style in the second edition. He appended an extra page to the book filled with nothing but punctuation — 13 lines of it, in fact — along with instructions that his readers should “peper and solt” the text as they pleased.

We all like what we like. Sometimes we even have reasons for it. I often pick on Neal Stephenson (not that he would give a shit) because I don’t particularly enjoy his books but the people who do REALLY do, and I enjoy poking them.

He lumbers. There’s action, of course, but his plots read like slow-motion recordings of a baseball pitcher in windup, which makes me think he’s the kind of guy who’s so proud of the delicious strike he’s about to deliver that he wants to make sure you see it in all its glorious detail.

Of course, if in your estimation he really does deliver a delicious strike, then all of that will seem worth it.

But, you say, just because I don’t like his stories doesn’t mean I can’t appreciate his writing ability, right?

Sure, especially versus someone like Stephenie Meyer. But then, as popular as Stephenson is, the Twilight series has pretty much blown him away, commercially. It even spawned a whole second series that ALSO blew him away — 50 Shades started its career as Twilight fan fiction.

I know people who enjoyed both. In each case, the writing, as a vehicle, for better or worse, delivered something they loved.

The problem is that, in fiction as in art, there is no sensical definition of “better.” Any criteria we choose will inevitably be a reflection of our own tastes. Does “better” mean “more technically proficient,” as Meyer’s critics often claim? If so, then the “best” writers are poets and authors of literature you don’t know and may never read, some of them quite astounding — people like Nayyirah Waheed, who self-published a book of her Instagram poetry:

you broke the ocean

in half to be here.

only to meet nothing that wants you.

—immigrant

For a lot of people, “better” seems to mean more enjoyable, regardless of diction or style. But then, how would we measure total enjoyment if not by sales? Fans of Stephen King and J.K. Rowling like this definition because it validates their tastes, but on that measure, Stephenie Meyer is also a great writer — much better, in fact, than Neal Stephenson or N.K. Jemisin, or the author of that one book you really liked.

The truth is, we don’t expect the same things from different books. What I want when I open a pulpy thriller is different than what I want from an erotic gay romance, or a book of poetry, or the latest Hugo Award winner, or whatever, and none of us judges any one of those on the same criteria as another even across our own tastes. How could we possibly reconcile our view with everyone else’s?

Some hundred years after Timothy Dexter died, James Joyce played the same trick with punctuation, to widespread critical acclaim, in his book Ulysses, which is often hailed as the greatest English-language novel of the 20th century. Which is the “better” punctuationless tome: the one the critics loved or the one that made lots of money?

I’ll end with this. In all the world, there is only one writer worse than me: the writer I was yesterday.

[image error]

cover image: René Magritte (Belgian, 1898-1967) “The Art of Conversation,” 1963

Ralph Goings (1928-2016) – “Still Life With Peppers,” 1981

Ralph Goings (1928-2016) – “Still Life With Peppers,” 1981

October 20, 2018

Queens of Night and of the Dawn

Utterly amazing work by Russian artist Exellero, whose majestic sorceresses seem able to conjure the night or its end. Pity the weary traveler who stumbles upon them.

October 19, 2018

(Fiction) For the unborn

John lost his best friend in Suriname. He left Danny’s body in a ditch after shooting him in the head. Danny looked up at John with no fear, no remorse. He’d been caught. John had orders. Danny would have done the same. He was good. But John was better. John didn’t have a wife, didn’t have a family he’d leave fatherless, didn’t have kids he was trying to put through college by selling biological weapons on the black market. John picked up his gun from the mud. Danny was on his knees, blood mixing with rain. Danny was the only man in the unit who knew things about John, personal things. That’s why they sent him. After the shot, John ran through the jungle, seventeen miles in a relentless rain, and mourned his friend. But when he made the extraction point, he put it away. For the unit.

John lost the only woman he had ever loved when she smiled and said her vows to another man. The sun was shining. The church was full of people. John’s tux didn’t fit right. He was best man. He felt like an ass and a liar standing up there in front of everyone pretending to be happy. But she wasn’t pretending. The couple laughed and danced into the night. John never told her how he felt. She never knew. Later that night, when he was finally alone in his hotel room, John cried for his love in quiet, feather-light heaves. Then he went for a dawn run and put it away forever. For his friends.

John was overseas on his first big mission when his sister’s life fell apart, when her husband left her with a toddler and a baby, kicked her and them out of the house. And hit her. At least once. John was thousands of miles away doing things human beings shouldn’t do to each other. It was weeks before he got the email. It was just like with their stepmom. His sister could never seem to escape it. Only now John wasn’t there to look after her. Or the kids. He suited up and ran through the wind-blown desert, tears evaporating in the heat along with the sweat. When he got back to base, there were new orders and he put his pain away. For his country.

John was seventeen when his stepmom sent his little brother to the hospital. He stayed with him until the boy made him leave. John had a game that night. It was the state finals. He was the star. Everyone was counting on him, including Jojo. John plowed over the other team’s defensive line. He ran and ran and ran. He scored three touchdowns. He was graduating in the spring, going into the army. His brother and sister would be alone with the woman. He cried under his helmet before the game. Then he put it away. For the team.

John lost his mother in seventh grade. She’d been sick for months. When the men with the sad looks showed up in English class to take him home, he ran. He ran like his coach had shown him, pushing past the strangers and sprinting down the hall and running out the door and across the parking lot and through the football field and four miles down the road to the elementary school where his brother and sister were waiting. He cried the whole way. But as he hugged them in the parking lot, he put it away forever. For them. Their dad wasn’t a strong man. So John would be. Always.

John hadn’t cried in the caves. He was too worried about surviving. He hadn’t cried on the flight home. He was too happy to be free. He hadn’t cried in the hospital. There were always people around, especially at first.

Do you want anything? More pills? More water? Another blanket? Can I help you wash? Help you into bed? Help?

And there were so many other patients in pain. Some with families, some without. Some with friends, some without. John did what he could. He told stories. He smiled. He made the rounds in his motorized chair. He didn’t have to say it. His appearance was enough.

If I can make it, so can you.

If I can make it.

John sat in his dark hospital room and looked down at his legs, limp and bent, barely fitting in the space between the seat and the footrest. He was a big man, always had been.

They had come, finally. The eyeless suits. The bastards. They were going to take it away. The tiny bit he had left.

He looked at his legs, then at his burned and mottled skin.

He scowled and made a fist and punched himself with his good arm. He punched his legs as hard as he could. He heard the sound, but he felt nothing.

A tear came.

John Michael Regent held up his one good hand in a ball. It shook in silent fury. He bared his teeth as teardrops fell from his lips. He wanted to scream. But then everyone would come. He wanted to yell. But they’d just look at him with those eyes.

He clenched his own shut. He was so tired. Of everything.

This would’ve been a night for a run. He always went at night. Nobody was likely to see and no body was likely to be missed.

His first few times he just ran and ran and ran, two firm legs striking the pavement in even strides, some other man’s heart pounding. Even a woman’s once. John had to take what he could get.

That was the night he happened on a mugging. It was an accident, a wrong turn at 3 a.m. He taught the jerk a lesson and handed the scared man on the pavement his wallet back. The guy just stared up at the strange woman in the hood and dark sunglasses—sunglasses, at night—who had leapt down from a roof and beat the shit out of his attacker.

“Those were some moves,” he said on his back, wide-eyed.

The woman had bent the mugger’s leg at the knee and roundhoused him into the wall. Right in the balls. Then she popped him straight up the jaw with the palm of her hand, knocked him out.

She didn’t respond. She just dropped the wallet and ran away.

The next week, John went looking for trouble. That was how he justified it. Taking the bodies. Taking what wasn’t his. Stealing them. Stealing tiny bits of someone else’s life. They’re not using it, he told himself. Like an idle computer or a fallow plot of earth. And I can do some good with it. I should do some good with it.

So John ran and ran and ran all over the city and all through the night. It felt good. On his fourth patrol, John stopped a backseat rape. Last month he helped a wounded pedestrian, a victim of a drunk hit-and-run, make it to a hospital. Two weeks ago he was tutoring a parkour group in basic self-defense. They were already in great shape. They knew how to move. He was just organizing them, teaching them tactics, things to consider when you happen upon a crime.

He pushed it that night. He stayed out too long. He watched the dawn come up from the roof of a five-story building. The little stretch of city before him hung on the outskirts of Philly and was full of working-class ethnic neighborhoods and strip malls. He was starting to think of it as his responsibility.

From what he could tell, the police weren’t looking for anyone, or at least not for anyone in particular. All anyone knew was that there were some helpful citizens about, and the only things they had in common were the hoodie and the sunglasses.

But the attack on the drug den would bring them to the hospital. Sooner or later, someone would put the pieces together, find the connection. They’d all been patients at the fancy new VA. They’d all used advanced hand-to-hand, like what a soldier would know. Regent couldn’t stay. It was too much of a risk now. If he ever wanted to run again, he had to get away. It was already on the news.

But in trying to leave, he had aroused his shadowy pursuers. John knew how it worked. “Ayn” was just the first wave. It was her job to keep him on the reservation long enough for the others to arrive. As his file was chewed by the system, as it triggered automatic flags and warnings, as numbered bureaucrats sipped soy lattes and processed it—processed him—each in tiny chunks, they would summon the dragons.

Men like John.

It didn’t matter if he had done anything. He was on a list. And to any lanyard-wearing case worker who didn’t know him from a hole in the ground, it was always better to be safe than sorry. That’s how they got people to give up their freedoms and to take other people’s away. Make it about safety, and never ask for more than a tiny bit at a time.

Advance file to next stage.

So this was it. The beginning of the end of a long, legless run. They’d get him. He knew. It was just a matter of time. But John was ready.

Almost.

He had one last mission. One final objective. And he was going to see it through. John Regent always completed the mission.

No excuses.

John wiped his face with his good hand. He took a deep breath and put it away. For the unborn.

The pivot of the first “episode” of my serial novel, THE MINUS FACTION, about extraordinary abilities and how not to use them.

October 18, 2018

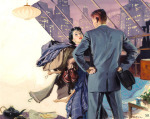

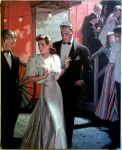

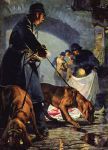

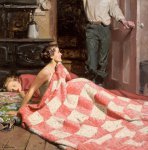

The Pulp Mysteries of Tom Lovell

Tom Lovell (1909-1997) was an American illustrator and painter best known for his pulp fiction magazine covers.

“Painting for the pulps was great training,” he said. “You learned to tell a story in close compass. You couldn’t spread out over two pages, and you couldn’t take three months to research it. You had to get the job out in ten days. This took discipline.”

His works are famous for their use of bright colors and for the way Lovell “focused” his images, painting the action in high contrast and leaving the fore- or background less sharply defined.

In the cover image to this post, for example, the chairs and table are almost completely black. The woman, trapped in a gazebo reminiscent of a prison cell, throws a high shadow even though it’s not at all clear where the light is coming from.

He often depicted men’s magazine stalwarts like the Old West and ancient Rome. On historical research methods, he said:

“When you’re painting history, it always comes down to fundamentals. Reading is a help. But writers don’t need the depth of information that a painter does. With a few well chosen words, a writer can set the scene, whereas an artist must know the costumes, the weapons, what the interiors looked like, the horse tack – all the thousand things to make it come alive. I wasn’t there when Alexander marched across India. But I was able to do a painting of what Alexander did by working like hell at it.”

I prefer his mysteries. In the depiction of the family Christmas below, for example, there is clear tension between the towering figure of the wife and her husband, in uniform on the floor, while their child opens presents gleefully. Indeed, it’s precisely that ability to capture human conflict and vulnerability in a single moment that makes him such an excellent illustrator.

“I consider myself a storyteller with a brush,” he said “I try to place myself back in imagined situations that would make interesting and appealing pictures. I am intent on producing paintings that relate to the human experience.”

October 17, 2018

There should be a rule that says a comment can’t be longe...

There should be a rule that says a comment can’t be longer than the original post.

The Book of Symbols

“I brought together all creatures, birds, beasts, reptiles, all trees and plants, usages and appearances, that are found in all tropical regions, and assembled them together in China and Indostan. From kindred feelings, I soon brought Egypt and all her gods under the same law. I was stared at, hooted at, grinned at, chattered at, by monkeys, by paroquets, by cockatoos. I ran into pagodas: and was fixed, for centuries, at the summit, or in secret rooms; I was the idol; I was the priest; I was worshiped; I was sacrificed. I fled from the wrath of Brahma through all the forests of Asia: Vishnu hated me. Siva laid wait for me. I came suddenly upon Isis and Osiris. I had done a deed, they said, which the ibis and the crocodile trembled at. I was buried, for a thousand years, in stone coffins, with mummies and sphinxes, in narrow chambers at the heart of eternal pyramids. I was kissed, with cancerous kisses, by crocodiles; and laid, confounded with all unutterable slimy things, amongst reeds and Nilotic mud.”

— Thomas De Quincey, “Confessions of an English Opium-Eater” (1821)

“The Book of Symbols” is something I simply assumed every creative had on their shelf. This week it was pointed out to me that that might not be the case. If not, you really ought to look into it.

800 pages of art and short essays, like encyclopedia entries, on the archetypes of thought organized into five categories — the cosmos, the human world, the spirit world, the plant world, and the animal world — each with its own colored ribbon affixed to the spine for handy bookmarking.

I can’t imagine doing half of what I do without it. Besides being a handy reference, I use it as a kind of text-based tarot, flipping pages randomly and reading the entries.

It’s a tad pricey, but you get what you pay for.

[image error] [image error]

cover image by Edward Gorey, from his tarot