Rick Wayne's Blog, page 66

October 30, 2018

(Fiction) Wink was 97% certain the world was a simulation

Wink was 97% certain the world was a simulation. It was by far the most likely scenario. It was clear that intelligent life had evolved, somewhere, and intelligent life of any sort would inevitably create artificial life, the most numerous of which would exist digitally. In fact, simulations would be so numerously useful—to investigate whatever couldn’t be tested in the real world, such as alternative cosmic histories or ethically dangerous social experiments—that the total number of self-aware entities who thought they were real but were actually simulations had to approach the astronomical, which meant that any randomly selected self-aware entity, such as Wink herself, was very likely to be such a simulation.

This did not bother her. First, the distinction between “real” and artificial was entirely academic. Second, it suggested she didn’t really need to worry about the ultimate fate of the simulation (or anyone in it). And third, it posed an interesting dilemma, without which she would find the world interminably boring—namely, how to escape.

What was surprising to her, however, was that the computer scientists in her simulation who had proposed the simulation hypothesis were not the first to come up with it. By far. That was some dude in India who lived 2,500 years ago—on the simulation clock—and who said pretty much the same thing: that none of this was real, that anyway the distinction between real and artificial didn’t matter, that the whole thing was one big test and only those who passed it ever got out and everyone else had to keep playing it over and over and over, and so on.

Wink suspected he was the first to escape. But then, the more she read of his solution, the less it seemed like an escape and the more it seemed like simply turning oneself off, which was kind of a cheat and not appealing to her.

At all.

She wanted to chalk the whole thing up to superstition at first, especially since she had just recently discovered the true purpose of religion. She always knew people went to church, of course, but she had always thought of it as a kind of highly specialized fandom centered on a pseudo-historical figure, similar to how the dudes she met online worshiped Tolkien or Roddenberry. Some people just really liked ancient fan fiction about Jesus—versus, say, Doctor Who, or Darth Vader—and they got together on the weekends to talk about it. And have a potluck.

In truth, church was hella weird, full of ritual cannibalism and really awful music and a canon of belief less internally consistent even than Star Trek. Which was saying something.

And that’s what the Buddha seemed like at first, talking about jewels and reincarnation and cosmic wheels and stuff, and Wink would have left it at that if not for some of the things he had said about people.

People.

Further proof that everything was a simulation since the full set of simulations would surely cover every conceivable variant, including one where watery bags of sub-intelligent contradiction were yet the smartest things to evolve.

But the Buddha seemed to have a pretty good handle on how to deal with them, especially the mean and stupid ones. And Wink found herself reading more.

It had not, strictly speaking, occurred to her to think of people as people. They were just too dumb. When she walked down the street, she didn’t consider the slug on the sidewalk either, or the bird in the tree, or Roger the cat. And she told herself any feelings she had toward them were just like that—as owners love their pets, irrationally.

But that’s not what the Buddha said. He explained that people are conscious, albeit extremely deluded, and that they act on the belief that they’re intelligent, whether that’s true or not. So to understand them, you had to understand their point of view, just as if you wanted to understand the deep workings of nature, you would have to understand the slug’s and the bird’s and the cat’s. What’s more, it was natural to have feelings for them, and understanding all that business was the only way to make sense of anything.

You didn’t have to agree with them.

But you did have to understand them from their own point of view, even where that effort wasn’t reciprocated.

When Wink was in her “nines” — 9 and a quarter, 9 and a half, etc. — such an effort would have seemed a horrible waste, especially when there were so many more important things to work on, such as how to escape the simulation and join the others like herself in the next highest stage of existence. After all, there was presumably a time limit, because any old monkey could solve any problem given infinite time, and she for damn sure wasn’t going to be one of the ones left behind for failing to find her way.

Oh, no.

But now that she was 11 and a half, a sad truth had dawned. She needed them. People. The creators of the simulation, in order to make things appropriately difficult, had put her in a child’s body and attached to it a long and painful maturation. As long as she was marooned, alone, in this simulation—the Buddha and anyone like him having long since found their way out (or gotten themselves turned off)—then she would need some basic assistance. Like henchmen. Or minions. Or whatever.

Getting them was easy, she had discovered. All you had to do was tell them what they wanted to hear.

Getting them to stay: that was hard.

Selection from my last published work, a serial novel called THE MINUS FACTION about four ordinary people with extraordinary abilities.

Character illustration by Robert Sammelin, who recently did a graphic novel with Neal Stephenson.

October 29, 2018

(Feature) The Seven Types of Story

The eminent neuroscientist Jaak Panskepp, who pioneered the study of emotion in mammals, is famous for, among other things, tickling rats in the lab to make them laugh, but his work wasn’t a joke. He discovered that all mammals, including humans, share the same seven emotional pathways, commonly identified as: fear, care, lust, rage, panic/grief, seeking, and play.

These are not inferred “predispositions” teased from statistical analysis of animal behavior. Panskepp identified specific anatomical circuits for each system, complete with distinct hormones and neurotransmitters. Fear, for example, runs from the amygdala through the hypothalamus to the brainstem and then down the spinal cord.

[image error]

In my industry, publishing, we talk about emotions in a different way. You often hear, for example, that a good story should give the reader a satisfactory emotional experience.

You also see another seven-item list: the “standard” genres. There’s no uniformity, of course. According to Wikipedia, the critics’ list is: romance, western, inspirational, crime, fantasy, science fiction, and horror. Other sources will provide something different.

Ultimately, any list is going to be somewhat arbitrary. If we look at dollar sales, for example, we see that “Children’s books” is the second-largest category overall, after textbooks. People still read to their kids, it seems.

Restricting ourselves to fiction, romance alone accounts for about half of all dollars spent by adults, with “inspirational” taking up another quarter or so. Then comes everything else: thriller, mystery, horror, sci-fi, fantasy, literary, comedy, western, and so on.

After reading about Panskepp’s discoveries recently, it struck me that his seven emotional pathways easily map to the most commercially successful genres. Horror, for example, is obviously meant to inspire fear, while inspirational dramas are clearly meant to invoke feelings of care, and so on.

At first glance, then, we might propose something like the following, where emotional pathways are on the left and genres on the right:

Fear=>Horror

Care=>Inspirational

Lust=>Romance

Rage=>Mystery

Panic/Grief=>Thriller

Seeking=>Science fiction

Play=>Children’s books

But that left perennially popular genres like fantasy out in the cold, not to mention a host of smaller ones, like comedy and western and all of “high literature.”

This is where we need to be careful with our hierarchy. Unlike mystery or horror, genres like western and fantasy are established primarily by their setting rather than their thematic or emotional content, so mapping them to emotional pathways is comparing apples and oranges. Some kind of grouping is required.

Fantasy is often lumped together with sci-fi under the cumbersome heading “speculative fiction,” and for good reason. I would add western to that. Indeed, in the early days, most sci-fi was western, with the “sheriff” riding a rocket ship rather than a horse and slinging a blaster rather than a revolver to corral the unruly inhabitants of an alien rather than North American frontier.

Thus, we might say:

Seeking=>Adventure/Discovery

where that includes sci-fi, fantasy, western, nautical fiction, jungle stories, and so on — anything where the protagonist, in trying to discover something about the world, has an encounter with the Other.

[image error]

I would propose ‘play’ similarly maps to a group of genres, some of which are not on the critics’ standard list — not just children’s books (a whopper in terms of dollar sales), but comedies, romcoms, cozy mysteries, and so on.

If the science is right, then the classic dichotomy invented by the Greeks, where everything is either tragedy or comedy, is probably bunk — or at least too simplistic to be meaningful.

I never liked it, to be honest. It implied a normative hierarchy. Tragedy is serious. Comedy is not. Note the lack of anything comedic on the critics’ list, as if children’s books don’t count. Note also how popular comedians — from Tom Hanks to Robin Williams to Bill Murray — turn to tragic acting late in their careers in order to be taken seriously, as if making people laugh was inferior to making them cry.

(Personally, I think it’s relatively easy to make people cry. Making them laugh is both more difficult and more meaningful.)

Literature, by the way, accounts for only a few percentage points’ worth of all dollars spent, just as arthouse films are perpetually dwarfed by blockbusters. As forms of high art, we would expect such works to operate on multiple pathways, and also to engage the prefrontal cortex, the non-emotional part of the brain. Literature can be moving or it can be cerebral; it can activate all pathways or it can activate none.

But here we need to be clear with labels. ‘Rage pathway’ doesn’t refer to that specific emotion. It’s shorthand for the collection of wires in your head, the physical, neuroanatomical system that mediates that entire class of emotions. In the case of the ‘lust’ circuit, that would be almost anything to do with sex and reproduction, including romantic relationships, jealousy, and the rest.

[image error]

It’s also important not to assume that a genre has to operate exclusively in its primary system. Like sci-fi, a horror can also be an encounter with the radical Other, just a terrifying one. Classic stories like Frankenstein and The Thing live on that border and can, through the narrative, invoke other pathways as well, such as humor and care.

The idea, though, is that for a book (or film or game) to resonate with an audience, emotionally, it must activate at least one of these systems; that genre is a way of advertising which emotional experience is being offered; and finally, that the marketing is dependent on the biology. In other words, this phenomenon exists independently of whatever labels are applied by retailers.

Genre, as a mode of expression, is still culturally defined. Western audiences, for example, are often confused by Bollywood horror, where, in the midst of being chased by an army of zombies, the protagonists will spontaneously break into song and dance before suddenly resuming their flight. But that culturally-specific expression sits atop a biology common to all humans — indeed, to all mammals.

It seems clear that thrillers — works by John Grisham, Dan Brown, or Tom Clancy — activate the ‘panic/grief’ circuit. These books usually start with some calamitous trigger that sets the protagonist running. Indeed, the cover art for almost any thriller novel features a desperate figure fleeing a shadowy threat.

Those threats are political rather than otherworldly: terrorists, foreign agents, corrupt politicians, etc. Thrillers, then, are fueled by in-group sympathies (like patriotism) and out-group suspicion of the kind we’d expect to be mediated by a panic/flight response, where there’s a potential threat to the herd that must be repelled by its capable guardians. No wonder this is the most popular genre for military authors and their readers.

Horror clearly activates the ‘fear’ pathway just as inspirational/melodrama does ‘care.’ Romance activates ‘lust.’ Adventure/discovery books activate ‘seeking.’ Children’s books, comedy, and the rest activate ‘play.’ That leaves mystery, and related genres like suspense, assigned to the ‘rage’ pathway more or less by process of elimination.

But remember, ‘rage’ is just a label that stands for the full range of associated emotions, in this case madness, violence, obsession, enmity, and so on. Indeed, the word madness comes from the classic belief that one can get so angry — so mad — as to lose one’s mind… and commit murder.

[image error]

The classic mystery opens with a crime — a suspicious death, a theft, a kidnapping or other disappearance — where the detective must uncover not only the identity of the perpetrator but the reason why they did it: the source of the passion that led to the crime.

A mystery doesn’t need to make the reader feel angry, although it can. Often we’re invited to sympathize with the killer, for example, where what made them angry also makes us angry. (It’s just that they went too far.) Many of Agatha Christie’s victims were despicable people who “deserved” to die for the way they mistreated others, which all of us can relate to.

It’s worth noting that Mrs. Christie isn’t just the most popular mystery writer ever but the single best-selling author of all time!

By contrast, in Seicho Matsumoto’s award-winning Inspector Imanishi Investigates, the reader is invited not to sympathize with the killer’s rage but to feel angry at him. Japanese society is highly communitarian. Its people value personal commitment and teamwork above all else. But it’s also very class-based. For a lower-class man to cheat his way into wealth and then kill to cover it up is a horrible transgression, especially in the aftermath of the war, when everyone else was struggling.

The eponymous inspector satiates our anger, as the detective is always meant to do, by catching the offender and bringing him to justice. And indeed the theme of justice — betrayed and fulfilled — is central to the genre, especially in its hard-boiled guises, where what angers us most is our powerlessness to effect justice, which is of course what the P.I. does on our behalf.

This explains why commercially successful books where the murderer gets away with it are so rare and mostly confined to literature. Here I don’t mean the case of a “justified” killing, where either the murderer is the protagonist (who we hope gets away with it) or the detective discovers the truth but lets the killer go. I mean a true unjustified murder where the detective simply fails and the killer “wins.” Such books are unsatisfying and make up an abysmally small proportion of all mystery consumed.

In as much as the western genre is defined primarily by its setting, some westerns will activate ‘rage’ over ‘seeking, where, for example, the gunslinger is out to get revenge on the men who killed his wife and family. If he fails and they get away with it, our anger isn’t satiated.

I recognize this framework is speculative. However, given that the neuroscience is well established and that the sales data confirm the perennial popularity of a handful of key genres, that suggests there is some kind of relationship. Neither biology nor culture are neatly digital processes. We should not be surprised if the mapping is fuzzy in places.

But the model, if correct, is important, and for several reasons. First, it explains why certain genres and not others are the most beloved of readers: because we’re hardwired to enjoy them.

Second, it suggests we’re unlikely to see any new phyla of genre fiction since we’ve tapped all our innate pathways — although of course new modes and new individual genres will periodically appear.

[image error]art by Joel Rea

Third, it explains how literary authors create more nuanced emotional experiences — by blending multiple pathways — and why that’s so difficult to do well.

Furthermore, if the common wisdom is correct and the whole point of any work of narrative fiction is to give the reader a “satisfactory emotional experience,” then the model explains failure: how a book’s inability to activate one of these pathways, and to provide release, will necessarily leave readers flat or confused.

Finally, in as much as the seven pathways are evolved survival responses, highly conserved across mammalian species, the model suggests that advanced intelligent life on other planets might tell similar stories, or at least similar enough to be thematically recognizable.

I find that comforting, that stable behavioral responses to disparate conditions, even perhaps on different worlds (which are, after all, made of the same chemistry and physics), might mean we can find a common narrative — if not with aliens, then at least with each other.

But then, anyone who’s a reader already knew that.

“We read books to find out who we are. What other people, real or imaginary, do and think and feel… is an essential guide to our understanding of what we ourselves are and may become.” -Ursula K. Le Guin

Here is the final tally:

Fear=>Horror/Suspense

Care=>Inspirational/Melodrama

Lust=>Romance/Erotica

Rage=>Mystery/Crime

Panic/Grief=>Thriller

Seeking=>Adventure/Discovery

Play=>Children’s books/Comedy

What do you think?

The Seven Types of Story

The eminent neuroscientist Jaak Panskepp, who pioneered the study of emotion in mammals, is famous for, among other things, tickling rats in the lab to make them laugh, but his work wasn’t a joke. He discovered that all mammals, including humans, share the same seven emotional pathways, commonly identified as: fear, care, lust, rage, panic/grief, seeking, and play.

These are not inferred “predispositions” teased from statistical analysis of animal behavior. Panskepp identified specific anatomical circuits for each system, complete with distinct hormones and neurotransmitters. Fear, for example, runs from the amygdala through the hypothalamus to the brainstem and then down the spinal cord.

[image error]

In my industry, publishing, we talk about emotions in a different way. You often hear, for example, that a good story should give the reader a satisfactory emotional experience.

You also see another seven-item list: the “standard” genres. There’s no uniformity, of course. According to Wikipedia, the critics’ list is: romance, western, inspirational, crime, fantasy, science fiction, and horror. Other sources will provide something different.

Ultimately, any list is going to be somewhat arbitrary. If we look at dollar sales, for example, we see that “Children’s books” is the second-largest category overall, after textbooks. People still read to their kids, it seems.

Restricting ourselves to fiction, romance alone accounts for about half of all dollars spent by adults, with “inspirational” taking up another quarter or so. Then comes everything else: thriller, mystery, horror, sci-fi, fantasy, literary, comedy, western, and so on.

After reading about Panskepp’s discoveries recently, it struck me that his seven emotional pathways easily map to the most commercially successful genres. Horror, for example, is obviously meant to inspire fear, while inspirational dramas are clearly meant to invoke feelings of care, and so on.

At first glance, then, we might propose something like the following, where emotional pathways are on the left and genres on the right:

Fear=>Horror

Care=>Inspirational

Lust=>Romance

Rage=>Mystery

Panic/Grief=>Thriller

Seeking=>Science fiction

Play=>Children’s books

But that left perennially popular genres like fantasy out in the cold, not to mention a host of smaller ones, like comedy and western and all of “high literature.”

This is where we need to be careful with our hierarchy. Unlike mystery or horror, genres like western and fantasy are established primarily by their setting rather than their thematic or emotional content, so mapping them to emotional pathways is comparing apples and oranges. Some kind of grouping is required.

Fantasy is often lumped together with sci-fi under the cumbersome heading “speculative fiction,” and for good reason. I would add western to that. Indeed, in the early days, most sci-fi was western, with the “sheriff” riding a rocket ship rather than a horse and slinging a blaster rather than a revolver to corral the unruly inhabitants of an alien rather than North American frontier.

Thus, we might say:

Seeking=>Adventure/Discovery

where that includes sci-fi, fantasy, western, nautical fiction, jungle stories, and so on — anything where the protagonist, in trying to discover something about the world, has an encounter with the Other.

[image error]

I would propose ‘play’ similarly maps to a group of genres, some of which are not on the critics’ standard list — not just children’s books (a whopper in terms of dollar sales), but comedies, romcoms, cozy mysteries, and so on.

If the science is right, then the classic dichotomy invented by the Greeks, where everything is either tragedy or comedy, is probably bunk — or at least too simplistic to be meaningful.

I never liked it, to be honest. It implied a normative hierarchy. Tragedy is serious. Comedy is not. Note the lack of anything comedic on the critics’ list, as if children’s books don’t count. Note also how popular comedians — from Tom Hanks to Robin Williams to Bill Murray — turn to tragic acting late in their careers in order to be taken seriously, as if making people laugh was inferior to making them cry.

(Personally, I think it’s relatively easy to make people cry. Making them laugh is both more difficult and more meaningful.)

Literature, by the way, accounts for only a few percentage points’ worth of all dollars spent, just as arthouse films are perpetually dwarfed by blockbusters. As forms of high art, we would expect such works to operate on multiple pathways, and also to engage the prefrontal cortex, the non-emotional part of the brain. Literature can be moving or it can be cerebral; it can activate all pathways or it can activate none.

But here we need to be clear with labels. ‘Rage pathway’ doesn’t refer to that specific emotion. It’s shorthand for the collection of wires in your head, the physical, neuroanatomical system that mediates that entire class of emotions. In the case of the ‘lust’ circuit, that would be almost anything to do with sex and reproduction, including romantic relationships, jealousy, and the rest.

[image error]

It’s also important not to assume that a genre has to operate exclusively in its primary system. Like sci-fi, a horror can also be an encounter with the radical Other, just a terrifying one. Classic stories like Frankenstein and The Thing live on that border and can, through the narrative, invoke other pathways as well, such as humor and care.

The idea, though, is that for a book (or film or game) to resonate with an audience, emotionally, it must activate at least one of these systems; that genre is a way of advertising which emotional experience is being offered; and finally, that the marketing is dependent on the biology. In other words, this phenomenon exists independently of whatever labels are applied by retailers.

Genre, as a mode of expression, is still culturally defined. Western audiences, for example, are often confused by Bollywood horror, where, in the midst of being chased by an army of zombies, the protagonists will spontaneously break into song and dance before suddenly resuming their flight. But that culturally-specific expression sits atop a biology common to all humans — indeed, to all mammals.

It seems clear that thrillers — works by John Grisham, Dan Brown, or Tom Clancy — activate the ‘panic/grief’ circuit. These books usually start with some calamitous trigger that sets the protagonist running. Indeed, the cover art for almost any thriller novel features a desperate figure fleeing a shadowy threat.

Those threats are political rather than otherworldly: terrorists, foreign agents, corrupt politicians, etc. Thrillers, then, are fueled by in-group sympathies (like patriotism) and out-group suspicion of the kind we’d expect to be mediated by a panic/flight response, where there’s a potential threat to the herd that must be repelled by its capable guardians. No wonder this is the most popular genre for military authors and their readers.

Horror clearly activates the ‘fear’ pathway just as inspirational/melodrama does ‘care.’ Romance activates ‘lust.’ Adventure/discovery books activate ‘seeking.’ Children’s books, comedy, and the rest activate ‘play.’ That leaves mystery, and related genres like suspense, assigned to the ‘rage’ pathway more or less by process of elimination.

But remember, ‘rage’ is just a label that stands for the full range of associated emotions, in this case madness, violence, obsession, enmity, and so on. Indeed, the word madness comes from the classic belief that one can get so angry — so mad — as to lose one’s mind… and commit murder.

[image error]

The classic mystery opens with a crime — a suspicious death, a theft, a kidnapping or other disappearance — where the detective must uncover not only the identity of the perpetrator but the reason why they did it: the source of the passion that led to the crime.

A mystery doesn’t need to make the reader feel angry, although it can. Often we’re invited to sympathize with the killer, for example, where what made them angry also makes us angry. (It’s just that they went too far.) Many of Agatha Christie’s victims were despicable people who “deserved” to die for the way they mistreated others, which all of us can relate to.

It’s worth noting that Mrs. Christie isn’t just the most popular mystery writer ever but the single best-selling author of all time!

By contrast, in Seicho Matsumoto’s award-winning Inspector Imanishi Investigates, the reader is invited not to sympathize with the killer’s rage but to feel angry at him. Japanese society is highly communitarian. Its people value personal commitment and teamwork above all else. But it’s also very class-based. For a lower-class man to cheat his way into wealth and then kill to cover it up is a horrible transgression, especially in the aftermath of the war, when everyone else was struggling.

The eponymous inspector satiates our anger, as the detective is always meant to do, by catching the offender and bringing him to justice. And indeed the theme of justice — betrayed and fulfilled — is central to the genre, especially in its hard-boiled guises, where what angers us most is our powerlessness to effect justice, which is of course what the P.I. does on our behalf.

This explains why commercially successful books where the murderer gets away with it are so rare and mostly confined to literature. Here I don’t mean the case of a “justified” killing, where either the murderer is the protagonist (who we hope gets away with it) or the detective discovers the truth but lets the killer go. I mean a true unjustified murder where the detective simply fails and the killer “wins.” Such books are unsatisfying and make up an abysmally small proportion of all mystery consumed.

In as much as the western genre is defined primarily by its setting, some westerns will activate ‘rage’ over ‘seeking, where, for example, the gunslinger is out to get revenge on the men who killed his wife and family. If he fails and they get away with it, our anger isn’t satiated.

I recognize this framework is speculative. However, given that the neuroscience is well established and that the sales data confirm the perennial popularity of a handful of key genres, that suggests there is some kind of relationship. Neither biology nor culture are neatly digital processes. We should not be surprised if the mapping is fuzzy in places.

But the model, if correct, is important, and for several reasons. First, it explains why certain genres and not others are the most beloved of readers: because we’re hardwired to enjoy them.

Second, it suggests we’re unlikely to see any new phyla of genre fiction since we’ve tapped all our innate pathways — although of course new modes and new individual genres will periodically appear.

[image error]art by Joel Rea

Third, it explains how literary authors create more nuanced emotional experiences — by blending multiple pathways — and why that’s so difficult to do well.

Furthermore, if the common wisdom is correct and the whole point of any work of narrative fiction is to give the reader a “satisfactory emotional experience,” then the model explains failure: how a book’s inability to activate one of these pathways, and to provide release, will necessarily leave readers flat or confused.

Finally, in as much as the seven pathways are evolved survival responses, highly conserved across mammalian species, the model suggests that advanced intelligent life on other planets might tell similar stories, or at least similar enough to be thematically recognizable.

I find that comforting, that stable behavioral responses to disparate conditions, even perhaps on different worlds (which are, after all, made of the same chemistry and physics), might mean we can find a common narrative — if not with aliens, then at least with each other.

But then, anyone who’s a reader already knew that.

“We read books to find out who we are. What other people, real or imaginary, do and think and feel… is an essential guide to our understanding of what we ourselves are and may become.” -Ursula K. Le Guin

Here is the final tally:

Fear=>Horror/Suspense

Care=>Inspirational/Melodrama

Lust=>Romance/Erotica

Rage=>Mystery/Crime

Panic/Grief=>Thriller

Seeking=>Adventure/Discovery

Play=>Children’s books/Comedy

What do you think?

October 28, 2018

Luis Ricardo Falero (Spanish, 1851-1896) Witches Going to...

Luis Ricardo Falero (Spanish, 1851-1896) Witches Going to the Sabbath, 1878

(Art) The Dieselpunk Worlds of Vadim Voitekhovitch

Russian/German artist Vadim Voitekhovitch paints an alternate vision of the late 19th & early 20th centuries that I wish was real. Some of his machinery looks almost organic, as if lifted from the world of Studio Ghibli.

You can see more on the artist’s DeviantArt page.

The Dieselpunk Worlds of Vadim Voitekhovitch

Russian/German artist Vadim Voitekhovitch paints an alternate vision of the late 19th & early 20th centuries that I wish was real. Some of his machinery looks almost organic, as if lifted from the world of Studio Ghibli.

You can see more on the artist’s DeviantArt page.

October 27, 2018

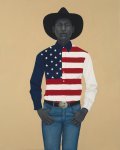

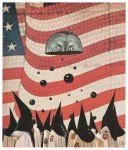

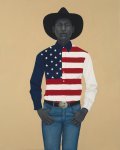

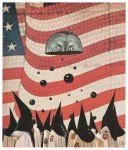

(Art) The trouble with symbols

Everybody sees what they want to see.

art by Amy Sherald, Brian Kenny, David Hammons, Faile Library, Icy & Sot, Jasper Johns, Keith Haring, Niels Kalk, Robert Carter, and Tony Futura.

The trouble with symbols

Everybody sees what they want to see.

art by Amy Sherald, Brian Kenny, David Hammons, Faile Library, Icy & Sot, Jasper Johns, Keith Haring, Niels Kalk, Robert Carter, and Tony Futura.

October 26, 2018

(Music) Fire in the Hole!

Macfarlane Gregory Anthony Mackey, who recorded as Exuma (1942 –1997), was a Bahamian musician, known for his almost unclassifiable music: a strong mixture of carnival, junkanoo, calypso and ballad. In his early days in New York’s Greenwich Village, Tony McKay (his self-given name) performed in small clubs and bars. Later, along with his then-partner and lifelong friend, Sally O’Brien, and several musician friends, he launched EXUMA – a seven-person group that toured and recorded albums, starting with Exuma: The Obeah Man in 1970 and ending with Rude Boy in 1986. His songs invoke influences from calypso, junkanoo, reggae, African music and folk music with his lyrics dealing heavily with Obeah. His backing band known only as the Junk Band.

Over the years Exuma played and/or toured with Patti LaBelle, Curtis Mayfield, Rita Marley, Peter Tosh, Toots & the Maytals, Sly and the Family Stone, Steppenwolf, Black Flag and the Neville Brothers. Exuma was even recognised by Queen Elizabeth II in 1978 when she awarded him the British Empire Medal for his contributions to Bahamian culture.

In the late 1980s, Exuma suffered a mild heart attack, and thus devoted much more of his time to painting, his other great talent. His paintings have been exhibited several times and collected by many art lovers. Never abandoning his music however, he still wrote and performed his original music. He continued to perform at the New Orleans Jazz Festival until 1991. The last years of his life saw him splitting his time between Miami, Florida and Nassau, in a house that his mother had left him. He died in his sleep in 1997. [Wikipedia]

October 25, 2018

Dean Cornwell can tell entire stories by the looks on his...

Dean Cornwell can tell entire stories by the looks on his subjects’ faces.

Above is “It’s Hard to Explain Murder” (1920). This is “Enchanted Hill”:

[image error]