Rick Wayne's Blog, page 69

September 29, 2018

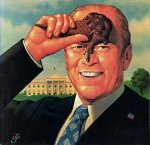

Liberalism’s Last Stand

William Gibson famously observed, a couple decades ago now, that the future had arrived, it just wasn’t evenly distributed. The fact that he had to say that and that people still find it insightful suggests they thought it would be evenly distributed, or reasonably so.

I’d like to say “I don’t know why that is” but I do know why that is. The public is quite deliberately refused a deep understanding of history, especially those in the technocratic classes (engineers, computer scientists, accountants, health care professionals, etc.) whose only real exposure to the subject is the memorization and regurgitation of names and dates and for whom, culturally, technology itself was (and sometimes still is) seen as the panacea, or at least the raw material from which it would be distilled.

There’s been an anti-utopian reaction to that in the last couple years, particularly among programmers of my generation who grew up on the hacker’s anarcho-utopian diet in the 1980s and 90s. There is no true believer as fanatical as the convert — the person who feels duped by their prior beliefs and who therefore makes it their mission to save the rest of us from the trap, for they alone know how easy it is to fall into.

You can see the passion play of historical ignorance in the debate over privacy, where privacy advocates act like its existed forever and people like Mark Zuckerberg, who declare it dead, act like nothing could possibly change. The first group takes the recent past and draws a straight line backwards. The second group takes the current trend and draws a straight line forward.

History has never, ever been a straight line.

The notion of property rights — of rights at all — dates roughly to the 17th century. (Let’s please not quibble.) For most of human history, both before and since, people didn’t have much privacy. Agents of both the crown and the church could enter your home on simple suspicion — the accusation of a neighbor, for example. They could arrest you and hold you indefinitely, which is still the case in China by the way, where most of the human species lives.

In the West, prior to the 20th century (when urban dwellers began to outnumber everyone else), privacy was minimal even where it was considered a legal right. Anyone who’s ever spent significant time in a small town understands this.

I’m not saying privacy is a fiction. I’m a big believer in it, actually, for all the reasons it was so hard won. I’m merely pointing out that the idea itself is no more than a few centuries old, and it only ever existed significantly in practice for the last hundred years or so. In that sense, privacy, like freedom and voting rights and racial equality, is a peak, a goal rather than a possession, something that must be continually striven for rather than cuddled jealously like a teddy bear.

Technology has corroded it; that’s true. But technology isn’t evil, not any more than acid is evil. Like acid, technology dissolves existing socioeconomic structures, thereby creating a gap at that point in society. Through that vacuum, old forces of inequality and oppression, which seem to be part of the human spirit, are now attempting a return from exile.

I’m borrowing the word corrosive from the British historian J.M. Roberts, who (along with many others) noted the effect that technological modernity had on traditional cultures around the world. That modernity arrived in European ships, riding a wave of gunpowder and pestilence, and it absolutely dissolved all it touched.

As the originators of the corrosion, Europeans were in a sense immune to its effects, since they cultured it. (Quite literally, as in it was a part of their culture.) They were also its beneficiaries. In taking the place of the traditional and parochial power systems that modernity destroyed, Europe conquered the world.

Now, however, the West is becoming the victim of the very same forces it unleashed. The structures of technological modernity, birthed at the same time as property rights, are being dissolved by the forces of hyper-technological post-modernity. The virus has mutated. The bacteria are resistant.

With the old structures failing, the question we now face is what to replace them with. I’ll give you a hint. Technology is not the enemy. Technology, like any tool, is only as good as the hand that wields it. There are better and worse designs of course, and we should strive for the former through legal or other means, but at the end of the day, hating technology is pointless. It’s the person at the helm of the machine that ultimately matters.

This is humanism, the belief that there’s more that unites than divides us, a once-liberal doctrine now seemingly abandoned by all sides in favor of wall-building — alternatively, to protect or to punish, to keep the good people in or the bad people out, to stop immigration or to stop cultural appropriation. In any case, there are groups of humans you are encouraged to join and those you are forbidden to.

I’m told someday this will all be replaced by transhumanism, which is an irrational love of technology rather than an irrational fear of it. But that’s just as silly. Technology only enhances what is already there. Like Dr. Erskine’s super-soldier serum, it makes good people better and bad people worse. Transhumanists, like most utopians, give scant credence to the very real possibility that the mechanisms of conversion will be co-opted by the wealthy and powerful and therefore what will result will not be dreamlike singularity but a dystopian nightmare.

Here there are two camps. The first, typically conservative, sees humanity as fundamentally unalterable — nasty, brutish, and all that — so any change must be forced through economic or military coercion. These folks argue that, at the point of change, there’s nothing to be done but make sure we’re the ones who take control. You’re witnessing that effort now.

The second group includes everyone who believes, to a greater or lesser degree, in the founding myth of liberalism, a rather outdated bit of psychology called the tabula rasa. These folks typically advocate some kind tax-funded educational program on the theory that, as possessors of a blank slate, people do bad things out of ignorance of good ones.

The fact that such programs have, even under the most charitable conditions, very mixed results does not deter these folks. Quite the opposite. Belief in myths is pre-rational of course, so if such a program fails, it’s because we did it badly or didn’t fund it enough, not because human nature is refractory to such things.

Refractory, by the way, doesn’t mean opposed. It means stubborn and difficult to manage.

It’s not that education never works — says the educated man. It’s that, historically speaking, we got most of the low-hanging fruit. Human beings are not born with a blank slate, after all. They come pre-loaded with all kinds of bloatware. Sadly, the world is complex — societies doubly so. We’ve probably run out of easy solutions. Going forward, we should expect things to be more difficult. The virus has mutated. The bacteria are resistant. Welcome to the future, which is to say the post-modern era of human history.

Liberalism, which brought us notions like privacy, was a child of modernity. Most of its founding myths, like the tabula rasa, have since been shown to be wrong, or at least incomplete, which means that liberalism is as useful in the post-modern world as the medieval worldview was in the modern.

Conservatism, for its part, seems a terrible step back toward religious paternalism. Human beings are not blindly coarse and immutable. In fact, sometimes they can be downright noble. But neither are they the blank slate upon which we can inscribe all our hopes and dreams. Most of the time they appear rather shabby, frankly, and some of them are outright dreadful, a deficit no voluntary education program can cure.

As for the way forward, history suggests a synthesis. In other words, your political adversaries are not wrong, which seems inconceivable until you realize that’s simply the converse of the truism that you and your allies are not infallible. Certainly, going about it the way we have these last few years will be just as productive.

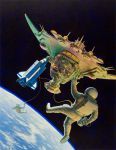

cover image by Paul Paetzel

September 28, 2018

The Man Who Lived His Dreams

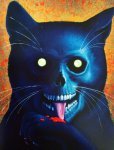

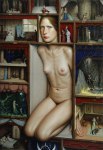

Painting by Vlada Mirkovic, “The Man who Lived His Dreams”

September 27, 2018

(Music) Pavane for a Dead Princess

A pavane is a slow, stately dance, two beats to the measure, popular in the 16th and 17th centuries and performed in elaborate clothing, or a piece of music written for the same.

“The original piano version of the Pavane pour une infante défunte was composed in 1899 and dedicated to the Princesse Edmond de Polignac (otherwise known as Winnaretta Singer), a French-American musical patron who was also the daughter of the nineteenth-century sewing-machine magnate, Isaac Singer. The orchestral arrangement wasn’t premiered for another eleven years.

The strikingly morose title of the work belies its actual inspiration: far from being about death, Ravel stated that ‘When I put together the words that make up this title, my only thought was the pleasure of alliteration’. While it’s literally true that the French should be translated as ‘Pavane for a dead Princess’, Ravel was at pains to point out that it ‘Is not a funeral lament for a dead child, but rather an evocation of the pavane that might have been danced by such a little princess as painted by Velázquez’. His comments went largely unheard, though; even today, many believe the piece to have a quite different meaning from the one the composer intended.” (from ClassicalFM.com)

Which do you hear?

I hear some lovely music for the changing of the seasons.

Follow the full ongoing playlist, All the Music You Missed, here.

cover image: Thomas Cooper Gotch, “The Child Enthroned” (1894)

September 26, 2018

Nations of experience

No matter how long I make a study of it, I cannot stop marveling at the slippery imprecision of English. It is not the most poetic language, but it is the most poetical in that it conflates single words with entire nations of experience.

Where other languages strive admirably to, for example, parse the diverse and various emotions of the heart, English piles them all into the word ‘love’ — four letters meant to convey, without distinction, the feelings of a man for his country, his mother, his child, his lover, his dog, his fishing pole, his god, his neighbor, his enemy, his best friend, the internet, and the pizza he is about to slavishly enjoy. Love is his ruin, his salvation, his benefactor, his nemesis, his charity, his insanity, the reason for his crimes, and the cause of his pardon.

Recently I was taking exception to a friend’s insistence — there, friend, is another nation of a word — that I didn’t like certain foods. I was trying to correct his misunderstanding, which is to say I was trying to speak with precision in the English language, which is a bit like trying to excise a tumor with a mallet.

I was left performing almost physical gyrations as I tried to get round, or penetrate, the word ‘like.’ I objected because to say in English “I don’t like liver” implies I won’t eat it. I don’t particularly like liver, but I do like liverwurst, and I absolutely love foie gras — just not the same way I love my dogs.

The first time I met my ex-wife’s parents, I was served a traditional Indian meal that included chickpeas. No sooner had they been set on the table than my now-ex-wife loudly declared “Rick doesn’t like chickpeas,” which I must have mentioned to her at some point. Horrified at the prospect of offending her guest and future son-in-law, her mother quickly moved the chickpeas as far from me as possible.

My protestations that I would be happy to eat them, while true, sounded like a polite whitewash. The damage had been done, and no matter how many times I demonstrated the falsity of the claim by actually eating chickpeas, it became a truism among the family that I didn’t do any such thing.

Now, as a matter of course, there is nothing I will not eat. Nothing. I ate spiders in China, pan fried and sprinkled with salt. I’ve eaten snails and frog’s legs in Paris and fresh caught garden snake in India. Surely I can manage a vegetable curry.

There are things I enjoy more or less than others, things I might not order for myself given other choices — almost anything with coconut, for example. But then, toasted coconut in trail mix is sublime. And given my notorious sweet tooth, if coconut cream pie, while likely my last choice on any menu, were the only option available over no dessert at all, or if I was served it at a dinner party, I would happily partake — and without gagging!

The same goes for liver, which I find a bit bilious in its raw form, or even Brussels sprouts, which I had recently, so thoroughly dredged in butter that I finished the whole plate. It’s fair to say I do not like any of those things. But I’d eat them. I would even eat human — provided it were ethically sourced.

I wonder if the damnable imprecision of English is part of the reason terms of service are so abominably wordy and why we have so many arguments about identity in this country, where we’re arguing over ownership of words meant for all. If so, it seems a high price for so much literature.

Bukowski wrote “a poem is a city where God rides naked through the streets, a poem is the nation, a poem is the world…” I’ll leave it there.

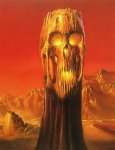

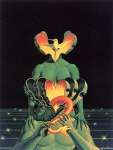

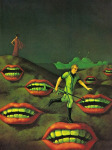

The head-warping fantasy art of Don Ivan Punchatz

Don Ivan Punchatz was a painter and illustrator famous in the latter half of the 20th century for his science fiction and fantasy book covers for Ace, Warner, Berkley, and Dell. He also made covers for TIME, Newsweek, and National Lampoon and editorial art for Playboy, National Geographic, Boys Life, and Penthouse, among others. Elected a Spectrum Art Grandmaster, he also served on that organization’s advisory board. However, he’s probably best known through his iconic art for the video game DOOM.

[image error]

September 23, 2018

On the cult of decline

“On every new thing there lies already the shadow of annihilation. For the history of every individual, every social order, indeed of the whole world, does not describe an ever-widening, more and more wonderful arc, but rather follows a course which, once the meridian is reached, leads without fail into the dark. Knowledge of that descent into the dark, for Browne, is inseparable from his belief in the day of the resurrection, when, as in theatre, the last revolutions are ended and the actors appear once more on stage, to complete and make up the catastrophe of this great piece. As a doctor, who saw disease growing and raging in bodies, he understood mortality better than the flowering of life. To him it seems a miracle we should last so much as a single day. There is no antidote, he writes, against the opium of time. The winter sun shows how soon the light fades from the ash, how soon night enfolds us. Hour upon hour is added to the sum. Time itself grows old. Pyramids, arches and obelisks are melting pillars of snow. Not even those who have found a place amidst the heavenly constellations have perpetuated their names: Nimrod is lost in Orion, and Osiris in the Dog Star. Indeed, old families last not three oaks. To set one’s name to a work gives no one a title to be remembered, for who knows how many of the best of men have gone without a trace? These are the circles Browne’s thoughts describe.”

— W.G. Sebald, in “The Rings of Saturn” (1998), paraphrasing a 1658 commentary on burial urns by physician and Renaissance man Thomas Browne.

Paraphrasing might be generous. It is impossible to know in the text, unless one is familiar with the source material, where it is Sebald and where it is the others he encounters, alive or dead, on his walking tour of the English coast. But then that’s part of his point: culture as ceaseless borrowing and re-inscription.

In short, he’s turned plagiarism into art, a kind of literary version of Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans.” At one point, Sebald spends the better part of three pages directly summarizing Borges’ short story “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius.” A report on Thomas Browne fills most of the first chapter.

The meaning of the title “The Rings of Saturn” is hinted at in a quote from the Brockhaus Encyclopedia included in the frontispiece: “The rings of Saturn consist of ice crystals and probably meteorite particles describing circular orbits around the planet’s equator. In all likelihood, these are fragments of a former moon that was too close to the planet and was destroyed by its tidal effect (see Roche limit).”

Sebald is making a symbolic tour of the debris of Western culture, which he finds both grotesque and beautiful, moreso now that it is — he argues — crumbling to sand.

“As I strolled through Somerleyton Hall that August afternoon, amidst a throng of visitors who occasionally lingered here or there, I was variously reminded of a pawnbroker’s or an auction hall. And yet it was the sheer number of things, possessions accumulated by generations and now waiting, as it were, for the day when they would be sold off, that won me over to what was, ultimately, a collection of oddities. How uninviting Somerleyton must have been, I reflected, in the days of [its] industrial impresario, Morton Peto, MP, when everything, from the cellar to the attic, from the cutlery to the waterclosets, was brand new, matching in every detail, and in unremittingly good taste. And how fine a place the house seemed to me now that it was imperceptibly nearing the brink of dissolution and silent oblivion. However, on emerging into the open air again, I was saddened to see, in one of the otherwise deserted aviaries, a solitary Chinese quail, evidently in a state of dementia, running to and fro along the edge of the cage and shaking its head every time it was about to turn, as if it could not comprehend how it had got into this hopeless fix. The grounds, in contrast to the waning splendor of the house, were now at their evolutionary peak, a century after the heyday of Somerleyton. The flower beds might well have been better tended and more gloriously colorful, but today the trees planted by Morton Peto filled the air above the gardens, and several of the ancient cedars, which were there to be admired by visitors even then, now extended their branches over well-nigh a quarter of an acre, each an entire world unto itself.”

In my youth, I thought — which is to say I wanted — history to be the result of impersonal mechanical forces, be they physical or social, as distinct from, firstly, “heroic” histories, popular on the Right, which sees history as the gain of a few great-willed men moving chess pieces on a field of battle, and secondly, from Marxist theory, popular on the Left, which, following Hegel’s dialectical materialism, imbued history, a thing in itself, with a kind spiritual manifest. (Indeed, Marx is basically equal parts Hegel, Rousseau, and Adam Smith.)

Being a product of the Age of Discovery, Marx saw history like the course of a jungle river: existing separately from us, having a determined form that already extends into the future, inescapable. Society traverses this river like a man in a canoe, bounded by its shores and destined to be carried to its terminus, which Marx described as a utopia.

This vision of history almost exactly matches “The Voyage of Life” paintings by Thomas Cole, which were produced in 1842, just two years before Marx met Engels. All three men were products of their time.

Marx’s vision is in a sense the opposite of Browne’s, as summarized by Sebald above. Where Browne saw life — which is our paradigm for society and thence history — as a parabola that, after reaching its zenith, descended in an arc into darkness, Marx saw it instead as an exponential progression, extending ever more rapidly to the heavens, like the chart of housing prices just before the crash.

Being a child of the 20th century, I had a hard time seeing history as an impersonal force. I also had difficulty with the idea of a predetermined path, ending in utopia, which seemed at least to contradict the findings from the physical sciences, which I think would have shocked Marx: that the fundamental state of things is uncertain until observed. Even rivers are not set. They change course, frequently.

It seemed to me history was more like the weather, or perhaps the ocean — governed at the large scale by forces that pulled against each other like so many vectors, but on the smaller scale bubbling with chaos, which was then all the rage in mathematics. I set out, then, to try to understand some of these forces. I read Braudel and the Annales school, William McNeill, and of course Jared Diamond, all of whom identified currents and tidal forces in the ocean of history.

Everyone, especially teenagers and old men, is obsessed with decline and convinced it’s just around the corner. The problem with the cult of decline is that is presupposes a certain point of view. In the case of Somerleyton, the house is falling apart, but for the trees, things have never been better! In that sense, the cult of decline is at the very least anthropocentric. It declares human physiology all one needs know of biology, and finding every human body on an inevitable march toward death, concludes that must be the fate of all.

I began to doubt it in school, as I read about the end of the Graeco-Roman world and “the Dark Ages,” which were an invention of the Renaissance, and especially as I escaped my Eurocentrism and learned, for example, about the dynastic cycle in China and it’s domino-like effects across Eurasia, and about the contiguity of past and present in places like Japan and Dravidic India.

From the standpoint of a single culture or locality, things certainly seem to rise and fall, just as if one stands on a beach, one will experience the repeated shifting of the tides and subsequent erosion of the shore. But what are the tides from the standpoint of the ocean, which moves about but doesn’t change? The erosion of one beach leads to its deposition elsewhere.

It’s the most curious and damnable trait of the brain that it’s not bounded by rationality (but rather the reverse). People can believe — and I’ve met folks on here who think this way — that things today are falling apart but that we’re also on the verge of the singularity. I find it hard to reconcile the disintegration of society with the immortality of all its constituents inside the most complex construct ever invented. How does that work exactly?

History is the story we tell ourselves about the past. The Christian story is a tragedy: Christ is murdered and everyone’s a sinner. But, as Browne notes, at the end of every tragedy, all the actors, even those killed on stage, are resurrected and take a bow before the director. Indeed, for someone like Calvin, the script was set and all you could do was play your part.

The cult of decline worships a tautology, a cognitive bias, a bank run. If you believe things are failing, then you won’t expend the energy necessary to sustain them.

The Roman Empire didn’t succumb to insurmountable tidal forces, a tsunami of invasion that wiped it away. Everything it faced at the end it had faced at least once before, to a greater or lesser degree. The difference is that people no longer believed it was worth saving.

I don’t think society, or Western culture, is disintegrating. It’s boiling, which looks the same from inside the pot. If the ancient world was solid and the modern world liquid, perhaps we’re entering the gaseous phase. The thing about gases is that they’re more flexible and adaptable than solids or liquids. And yet, they remain governed by natural forces — Boyle’s Law, for example, and the laws of thermodynamics.

Same for the rings of Saturn, which are far more beautiful than any moon.

———————–

cover image by Suzanne Moxhay

[image error]

September 21, 2018

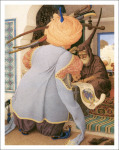

The mad fanciful fairy tales of Andrej Dugin and Olga Dugina

Husband-and-wife team Andrej Dugin and Olga Dugina combine the style of classic Russian illustration with the grotesque fantasies of Bosch and Bruegel in a series of children’s books, including a collaboration with Madonna. Their colorful, lavishly textured art is reminiscent of Renaissance tapestry, with all its symbolism, and while it sometimes borders on the surreal, like the works of Roald Dahl, it never quite crosses over.

Originally from Russia, the couple now live in Stuttgart. You can find more about them on their website.

These images are definitely worth clicking for more detail, which is opulent.

September 18, 2018

17 Chicks (portrayals of women)

Margaret Bowland, “White Fives”

Harumi Hironaka

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, self portrait of the artist

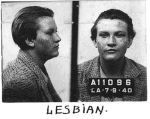

mugshot

Tom Bagshaw, “Tomoe Gozen – Onna-bugeisha”

Sarah Bishop

David Uzochukwu

Tiyan Muhammad

Dino Valls, “PROSCAENIA”

Icky H, “Mother Tribe”

Rahzzah Murdock

Bianca Bagnarelli

Hiroshi Furuyoshi

Lu Cong

Rosemary Valero-O’Connell, “Spider-Gwen”

Marina Bychkova, breast cancer doll

Ronit Baranga

September 17, 2018

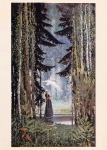

The Martial Mytho-fantasies of Konstantin Vasilyev

“Konstantin Vasilyev died on October 29, 1976 in a railway accident near Kazan. His family and friends never believed in the official version of his death and suspected that the painter was murdered. Vasilyev was buried in the village of Vasilyevo, where he lived since 1949.

Recognition came posthumously. Vasilyev’s oeuvres steadily gained in popularity through the late Soviet and early post-Soviet periods, until they have reached a virtually iconic status among Russian nationalists, neo-pagans and fantasy geeks. A documentary “Vasilyev from Vasilyevo” was released in 1978. The minor planet 3930 Vasilev, discovered by Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Zhuravlyova in 1982, is named after him. The Konstantin Vasilyev Museum opened in Moscow in 1998. In 2013, the Konstantin Vasilyev Art Gallery was opened in Kazan.” (Adapted from Wikipedia)

It’s hard to know what to make of Russian symbolist painter Konstantin Vasilyev (1942-1976). In depicting Slavic and Teutonic myth, his work are now beloved of Russian nationalists, which is disturbing, but in composition, there’s nothing you wouldn’t find on the pages of any Dungeons and Dragons manual, or in museums across the Western world. Indeed, Marvel has a major character and a whole series of movies taken directly from Teutonic myth. That’s the problem with symbols; they’re fluid and easily co-opted by later generations, for good or bad.

Little is known about Vasilyev’s personal beliefs, especially since his fame came posthumously, but his apparent assassination at the hands of the Soviet state would suggest he wasn’t a good communist. I suspect he was simply a man who liked battles and fantasy stories and who drew upon the only inspiration he had.

He was certainly prolific, producing over 400 works in his short lifespan. My favorite is his portrait of Nastasia Mikulichna, a female warrior from a Russian epic myth. I love in particular how one of her gauntlets has been thrown, and how the seemingly innocent tree in the foreground cuts her in half, foreshadowing a gruesome fate.

[image error]

September 14, 2018

(Fiction) In the Web of the Maze Master

I was not then entirely sure where I was, but it seemed clear we had reached our destination, for a congress of cats waited. Felines of all breeds and colors—a few with collars, like my tabby, but most without—sat on the walls and ledges, fence posts and trash cans above and around me. It would’ve been unnerving had they been looking at me. But they weren’t. Most had their eyes on the tunnel ahead, as if waiting for something to emerge from shadow.

My tabby sat on the ground several paces in front of me, erect, as if protecting me from whatever was about to make an appearance. Her collar was green, but I couldn’t read the tag. I was studying it from a distance when I noticed the eyes—hundreds, at least, shining in the dark ahead. Not cats. Rats. Only a handful emerged into the light. They raised their little snouts and sniffed and moved their whiskers about. After a short silence, where the congress of cats neither moved nor made a sound, more felines appeared dragging one of their own, a feral male—long-haired, mangy, and hobble-legged, with only one good eye. He was big. In fact, he had the widest girth of any of the cats present, and it took three of them to drag him forward, his hind claws scraping across the pavement. He was a fugitive, it seemed, for he protested in frantic caterwauls. Seeing no escape, and that his pleas were being ignored by his fellows above, he turned from fear to anger and hissed at the crowd, as if hurling terrible insults.

An old rat scuttled from shadow and raised his head and sniffed. By the look of his eyes, he could no longer see, but he discerned from the air—from scents and the motion of the breeze against his long white whiskers—all he needed to know of the world. He seemed to communicate that way as well, by flicking his whiskers this way and that, for he made no noise. I couldn’t say for sure what I was witnessing, but it seemed to me a transgression had occurred, perhaps against some kind of truce or treaty. Perhaps there had been a war. Perhaps both sides had lost many comrades, for while the cats were bigger and stronger, the rats were numerous. In the scene before for me, there were at least ten times as many rats, and I suspected there were a hundred more further in the dark, gathered from across the city.

And then it seemed to me the deal was concluded and the mangy cat was given to the rats, who bit it with their long front teeth—those incisors that continually grow and which they use to chisel through pipes and brick. They gripped him in numbers such that he could barely contract his body. His limbs were stretched, and he seemed terrified. For a moment I thought they might quarter him, but they didn’t. They simply hauled him away. Whatever fate befell him, I do not know, but as he disappeared with one plaintive wail, several of the cats got up and started to walk away slowly, as if heavy with sorrow at what had to be done.

My tabby and I were meant to follow the rats. It seemed she was to be my companion and to share whatever danger awaited us. I would be lying if I said I didn’t linger there at the edge of that tunnel, for rats are known to be fickle and to serve both sides. It was the rats who delivered the plague to man at the behest of the elder gods. It was the rats who betrayed those gods and ended it when threatened by man. My tabby seemed to understand the predicament. She glanced at me before trotting ahead confidently. She had the most interesting heterochromia. Her right eyes was flecked gold that faded to green at the center, near the iris. Half of her left eye was the same. The other half was deep blue. The boundary line was somewhat fuzzy but exactly coincided with the change in color of her surrounding fur. She kept her head up and eyes straight, resisting the urge to hiss at the rats, who made subtle clicking noises at her as she passed. After a moment, I followed.

Our guides led us under the city and into the most impenetrable labyrinth one could imagine—impenetrable because it was not, like other labyrinths, a contrivance. It was an accident, made entirely of gaps, nooks, crawlspaces, and debris—remainders of centuries of overlapping human construction. In a normal labyrinth, even if one is lost, one at least knows which ways one can go. Walls clearly mark the options: forward, back, right, or left. The holes and shafts through which we were led, however, offered no such visual clue. I had to duck, shimmy, squeeze, and crawl through most of it, and if not for the cluster of rats that both led and followed us, I would’ve had no idea which way it was even possible to go, let alone how to get out.

My tabby waited at every opening, the tip of her tail flicking cautiously. She also saved one of my fingers from being clipped off. I was flat on my stomach trying to squeeze through old mortared brick when I got stuck. After some struggle, when it was clear I couldn’t make it through, the rats came, crawling over each other, and began to gnaw on the mortar with those continuously growing teeth. The overlapping sound of so much scratching was much like nails on a chalkboard, and I closed my eyes as I fought to keep my stomach from emptying and my spine from dancing out of my back, for I could not only hear but feel the vibrations. So it was I didn’t see one of the rats working closer and closer to my index finger, which gripped a brick. I felt a nip and recoiled just as my tabby swatted the creature out of the way with a hiss. The rats stopped then, and for several moments, everyone was still. Stuck in that hole, I had no chance of offering any resistance, and I prepared to push myself backward if necessary, my muscles as taut as the tension in the air. But then it passed. Our guides resumed their feverish gnawing, and within a minute or two, at most, I was able to kick through the gap with nothing but some scratches and a nipped finger that was already scabbing over.

I bent to thank my tabby, which is when I saw her collar. Apparently her name was Purcival.

“Purcy,” I said, and her ears perked up in surprise, as if I’d just performed the most spectacular trick by guessing her name. The two of us barely made it thirty yards before a pallet-wood floor gave way under our feet. It had clearly been stacked in such a way as to hide the hole underneath, through which we tumbled. Which way we fell, I couldn’t say, for my head was spinning and I lost all sense of direction. I remember only confusion followed by the ringing of cowbells and a hard splash. I surfaced and took a deep breath. We had landed in a pool that filled the irregular base of a large, vaguely dome-shaped space, although no two sides of it were the least bit symmetrical. Light fell from a single round shaft at the top, which suggested an exit to the surface—a vent of some kind to equilibrate pressure between the sewer and the atmosphere above—although there was no way to reach it. The opening was at least twenty feet above the surface of the water.

The rest of the room was almost LEGOlike, made of various block protrusions and concrete platforms of different heights. Water dribbled from small open pipes. Larger ones zigzagged up and down between the platforms, changing direction at right angles. I paddled to the lowest platform and pulled myself out of the grimy water. There was a kind of square manhole built in the concrete, but a quick check revealed it was too heavy for me even to budge. Purcy leapt onto the concrete then, dripping wet and snarling in disgust. Her back was arched as if she were trying to hold her limbs away from her nose. I knew how she felt. It wasn’t raw sewage, but it was definitely dirty and smelled vaguely of rotten food. I looked up at the hole in the wall from which we fell. It was dark. The hinged bar that stretched in front of it was attached to a string from which half a dozen cowbells hung—a makeshift alarm. Someone—or something—was alerted to our presence. My little friend shook then and drops flew. I laughed at first, but in turning my head to avoid the spray, I caught sight of the tiny bones that littered the margins of the space. There were dozens, maybe hundreds—far too many to have been the remnants of natural death. They were too pristinely white as well. Picked clean.

I stood and listened.

There was a low arched grate across the water to our left. It was too small for me, but my tabby could squeeze through the bars quite easily. It seemed to me then that the space was a kind of hub, a meeting point of several paths, for there were at least four separate openings converging there—the grate, the manhole, and the two gaps above, one lit and one dark—and I suspected there were yet more more hidden in the shadows and around the corners of the block-filled space. Like the center of a web.

I glanced again to the bells hanging in a string from the ceiling. “We need to get out of here,” I said in a whisper. Purcy seemed to understand me and bounded light-footed and silent from platform to platform, right to the arched grate, where she stopped and turned back to me, as if just realizing there was no way I could fit.

“Go on,” I urged. “Get help.”

But she saw through my ruse and sat near the grate and cleaned herself, as if somewhat perturbed that I had tried to trick her. I scowled.

“There’s no reason for you to be eaten as well,” I chided, but she ignored me. “Suit yourself. But you wouldn’t stay if you knew what lived here.”

We’d been betrayed. That much was certain. The rats, it seemed, were angry at Etude over the affair with the dagger, in which many of their kind had been bewitched and killed. They blamed him, or so I gathered. They’d deposited us in a nest—almost certainly the home of a trillig, sometimes called a maze master, a distant relative of the troll which had adapted much better to urban life than its mountain-dwelling cousin. In their behavior, maze masters were somewhat like beavers, or perhaps hermit crabs, in that they preferred to move into a ready-built “maze,” which included anything even remotely mazelike: dense copses, subway tunnels, abandoned asylums, and so on. There they would gradually make modifications, like a beaver to a dam, that made it easier for the random wayward traveler to get lost inside. In my time with the mizzen, I had been reliably informed that there were at least three maze masters in the Paris catacombs and that they squabbled with each other over territory. In America, I had heard of another that constructed an elaborate roadside attraction somewhere in the middle of the country—Minnesota I think—a maze of arched stucco in whose walls were embedded countless baubles: glass bottles, batteries, plastic toys, dishware, postcards, shoes, walking sticks, eyeglasses, fake beards, rings, toothbrushes, playing cards, old cigar boxes, fishing rods and lures, hammers, saws, vases, dolls, tins, typewriters, and memorabilia from countless other such attractions across the country—miniature replicas of the House of Mud and the World’s Largest Frying Pan. The lone and curious tourist, tempted by a rarely open door at the very center of the maze, would, if they were not careful, disappear without a trace.

This maze master, I was fairly sure, had once guarded a vault for Granny Tuesday. Granny had collected all kinds of such nasties, some for no other reason than to let them loose on the city and so annoy Etude. After her arrest and incarceration, this monster had apparently wandered into the tunnels under the city, where it had been subsisting on a diet of sewer rats, or so the litter of bones suggested. I’m sure that contributed to rats’ choice: this thing was known to them as a voracious killer. It was also somewhat catlike in as much as maze masters liked to play with their food before devouring it. They had a constitutional predilection for puzzles and games, which is how they found their way into human folklore: as riddlekeepers who would offer their victims a chance of escape in exchange for a contest. Of course, maze masters preferred to cheat over losing a meal, but they were not known as outright liars. It ruins the suspense and excitement of a game if you know in advance your opponent has no chance of winning. That meant there was definitely an exit hidden somewhere in that room. I just had to find it.