Rick Wayne's Blog, page 72

August 5, 2018

The Secret Libraries of Erik Desmazières

“Five hundred years ago, the chief of an upper hexagon came upon a book as confusing as the others, but which had nearly two pages of homogeneous lines. He showed his find to a wandering decoder who told him the lines were written in Portuguese; others said they were Yiddish. Within a century, the language was established: a Samoyedic Lithuanian dialect of Guarani, with classical Arabian inflections. The content was also deciphered: some notions of combinative analysis, illustrated with examples of variations with unlimited repetition. These examples made it possible for a librarian of genius to discover the fundamental law of the Library. This thinker observed that all the books, no matter how diverse they might be, are made up of the same elements: the space, the period, the comma, the twenty-two letters of the alphabet. He also alleged a fact which travelers have confirmed: In the vast Library there are no two identical books. From these two incontrovertible premises he deduced that the Library is total and that its shelves register all the possible combinations of the twenty-odd orthographical symbols (a number which, though extremely vast, is not infinite) that is, everything it is given to express: in all languages. Everything: the minutely detailed history of the future, the archangels’ autobiographies, the faithful catalogues of the Library, thousands and thousands of false catalogues, the demonstration of the fallacy of those catalogues, the demonstration of the fallacy of the true catalogue, the Gnostic gospel of Basilides, the commentary on that gospel, the commentary on the commentary on that gospel, the true story of your death, the translation of every book in all languages, the interpolations of every book in all books, the treatise that Bede could have written (and did not) about the mythology of the Saxons, the lost works of Tacitus.”

— Borges, “The Library of Babel“

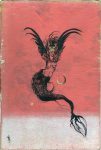

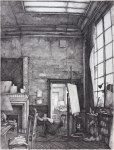

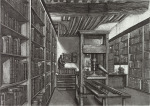

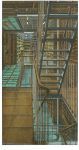

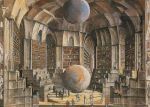

“There are printmakers and printmakers, and then there is Erik Desmazières, a Moroccan-born Frenchman who stands in a class by himself. A powerful, old-style draftsman whose work runs from fantasy to superrealism, he manipulates the techniques of etching and aquatint to produce masterly effects of space, light and shadow.

One of his greatest projects was a series of illustrations done in 1997 for Jorge Luis Borges’s ”Library of Babel,” an architectural rumination whose brilliance in conceiving and rendering offbeat spaces matches the prose of Borges. Several prints from the series are shown here.

A more conventional example of his skill with architectural space is a recent (2001) depiction of the main reading room of the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, La Salle Labrouste. More than three feet wide and done from a high perspective, the print captures the vast dimensions of the room with its arched walls and multidomed ceiling vis-à-vis the tiny figures of knowledge-seekers deployed at acres of tables.”

August 4, 2018

(Music) Yé-yé! Oh yeah!

Yé-yé was a style of pop music that emerged from Southern Europe in the early 1960s. The term “yé-yé” was derived from the English term “yeah! yeah!”, popularized by British beat music bands such as the Beatles. The style expanded worldwide, due to the success of figures such as the French singer-songwriters Serge Gainsbourg and Françoise Hardy.

Although originating in France, the yé-yé movement extended over Western Europe. The Italian singer Mina became the country’s first female rock and roll singer in 1959. In the following few years, she inclined to middle-of-the-road girl pop. After her scandalous relationship and pregnancy with a married actor in 1963, she developed her image into a grown up ‘bad girl’. An example of her style were the lyrics of the song “Ta-ra-ta-ta”: “The way you smoke, you are irresistible to me, you look like a real man”. By contrast, her compatriot Rita Pavone cast the image of a typical teeny yé-yé girl. For example, the lyrics of her 1964 hit “Cuore” complained how love made the protagonist suffer.

In Italy the yé-yé wave ended around 1967, vanishing under the emergence of British rock-blues / pop, and psychedelia. Parisian-born singer Catherine Spaak had a massive success in Italy, with a style very close to Françoise Hardy. Other significant yé-yé girls include Mari Marabini, Carmen Villani, Anna Identici and the girl-groups Le Amiche, Le Snobs and Sonia e le Sorelle.

In Spain, yé-yé music was at first considered to be against Catholicism. However, this did not stop the yé-yé culture from spreading, although a bit later than in the rest of Europe; in 1968 Spanish yé-yé girl Massiel won the Eurovision song contest with “La, la, la”. Subsequently, she failed to maintain her success, and the sweet, naïve-looking singer Karina enjoyed success as the Spanish yé-yé queen with her hits “En un mundo nuevo” and “El baúl de los recuerdos”.

At the end of the 1970s there was a brief but successful yé-yé recurrence in France, spreading across the charts of western continental Europe, with electro-pop influenced acts like Plastic Bertrand, Lio and Elli et Jacno and in a more rocking vein, Ici Paris and Les Calamités (a subgenre dubbed “Yé-yé Punk” by Les Wampas leader Didier Wampas). Lio especially had a string of hits during 1980, the most famous of which was “Amoureux Solitaires”. This new brand of yé-yé, although short lived, made good use of the new electronic keyboards and synthetic drums that had surfaced recently with new wave music.

Yé-yé grew very popular in Japan and yé-yé music is in the origins of Shibuya-kei in the 1990s and Japanese idol music. There is a Japanese version of the 1965 Eurovision-winning song “Poupée de cire, poupée de son” composed by Serge Gainsbourg and performed by France Gall. Japan has released a DVD copy of Cherchez l’idole featuring Johnny Hallyday, a notable yé-yé singer. One of the more popular yé-yé vocal groups was Les Surfs who appear in Cherchez l’idole performing their hit song “Ca n’a pas d’importance”. (Wikipedia)

For more:

https://www.mixcloud.com/widget/iframe/?feed=%2FFeral_House%2Fferal-house-deluxe-y%25C3%25A9-y%25C3%25A9-mix-1%2F&hide_cover=1&light=1

https://www.mixcloud.com/widget/iframe/?feed=%2FFeral_House%2Fferal-house-deluxe-y%25C3%25A9-y%25C3%25A9-mix-deux%2F&hide_cover=1&light=1

Yé-yé! Oh yeah!

Yé-yé was a style of pop music that emerged from Southern Europe in the early 1960s. The term “yé-yé” was derived from the English term “yeah! yeah!”, popularized by British beat music bands such as the Beatles. The style expanded worldwide, due to the success of figures such as the French singer-songwriters Serge Gainsbourg and Françoise Hardy.

Although originating in France, the yé-yé movement extended over Western Europe. The Italian singer Mina became the country’s first female rock and roll singer in 1959. In the following few years, she inclined to middle-of-the-road girl pop. After her scandalous relationship and pregnancy with a married actor in 1963, she developed her image into a grown up ‘bad girl’. An example of her style were the lyrics of the song “Ta-ra-ta-ta”: “The way you smoke, you are irresistible to me, you look like a real man”. By contrast, her compatriot Rita Pavone cast the image of a typical teeny yé-yé girl. For example, the lyrics of her 1964 hit “Cuore” complained how love made the protagonist suffer.

In Italy the yé-yé wave ended around 1967, vanishing under the emergence of British rock-blues / pop, and psychedelia. Parisian-born singer Catherine Spaak had a massive success in Italy, with a style very close to Françoise Hardy. Other significant yé-yé girls include Mari Marabini, Carmen Villani, Anna Identici and the girl-groups Le Amiche, Le Snobs and Sonia e le Sorelle.

In Spain, yé-yé music was at first considered to be against Catholicism. However, this did not stop the yé-yé culture from spreading, although a bit later than in the rest of Europe; in 1968 Spanish yé-yé girl Massiel won the Eurovision song contest with “La, la, la”. Subsequently, she failed to maintain her success, and the sweet, naïve-looking singer Karina enjoyed success as the Spanish yé-yé queen with her hits “En un mundo nuevo” and “El baúl de los recuerdos”.

At the end of the 1970s there was a brief but successful yé-yé recurrence in France, spreading across the charts of western continental Europe, with electro-pop influenced acts like Plastic Bertrand, Lio and Elli et Jacno and in a more rocking vein, Ici Paris and Les Calamités (a subgenre dubbed “Yé-yé Punk” by Les Wampas leader Didier Wampas). Lio especially had a string of hits during 1980, the most famous of which was “Amoureux Solitaires”. This new brand of yé-yé, although short lived, made good use of the new electronic keyboards and synthetic drums that had surfaced recently with new wave music.

Yé-yé grew very popular in Japan and yé-yé music is in the origins of Shibuya-kei in the 1990s and Japanese idol music. There is a Japanese version of the 1965 Eurovision-winning song “Poupée de cire, poupée de son” composed by Serge Gainsbourg and performed by France Gall. Japan has released a DVD copy of Cherchez l’idole featuring Johnny Hallyday, a notable yé-yé singer. One of the more popular yé-yé vocal groups was Les Surfs who appear in Cherchez l’idole performing their hit song “Ca n’a pas d’importance”. (Wikipedia)

For more:

https://www.mixcloud.com/widget/iframe/?feed=%2FFeral_House%2Fferal-house-deluxe-y%25C3%25A9-y%25C3%25A9-mix-1%2F&hide_cover=1&light=1

https://www.mixcloud.com/widget/iframe/?feed=%2FFeral_House%2Fferal-house-deluxe-y%25C3%25A9-y%25C3%25A9-mix-deux%2F&hide_cover=1&light=1

August 3, 2018

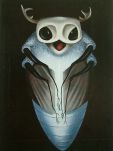

The Noumena of Félix Labisse

Félix Labisse (1905 – 1982) was a French surrealist painter and set designer known for his series of blue women and for his demonic figures, which seem like outtakes from the works of Hieronymus Bosch.

Although it doesn’t quite match the explicit thoughtfulness of Magritte, seven years his senior, Labisse’s work is also more accessible, more purely symbolic, and so asks less of the viewer than the former’s. As is true of most surrealist art, any meaning is very much in the mind of the observer.

August 2, 2018

(Fiction) The Winter Bureau

That was my welcome to America. Prison.

Upon my release, I was placed into the custody of a man of ill health, ill fortune, and ill name: Spurgeon Fount, a parapsychologist-acolyte of Richard Hodgson—the man who, as an analyst for the Psychical Research Society, had discredited and disgraced HPB for speaking openly of The Masters. Spurgeon had no taste for politics, however, and turned instead to vampire hunting. Our time together was lively. Spurgeon was lustful and repressed, as were so many of his peers, and he wound up naked and drained by one of his prey after she lured him into one of his own traps. The beast traveled under cover of a circus, which is why I had been recruited. Many circus performers in those days were foreign, lured from across Europe with promises of streets of gold. Thanks to Durance, I was handy with a lock pick and a blade, which meant, with some training, I could perform minor feats of escapistry and knife throwing and so was inserted into the circus as an apprentice in order to discover the identity of the foul creature, who I understand played some important role for our as-yet unidentified enemy. She also had a voracious appetite. Alas, I was a very poor spy and didn’t succeed in my mission in time to save Spurgeon’s life. But I avenged him. Our vampiress was a tumbler and quite a difficult woman to pin down. I managed to impale her on a tent pole, but only by throwing her off of me, whence I was bitten.

I cannot describe what followed since I was not conscious to witness it. For the longest time, two curses waged war within me: one granting me eternal life, the other eternal undeath. It seemed neither could get the better of the other. I was wracked with tremors and night sweats that emerged between long bouts of still coma, by which I mean years. Twenty-three, in total. I was kept in a sanitarium, expenses covered by The Masters, or rather by their proxies. This was not done out of charity or obligation but rather because mine was a unique case deemed worthy of study. It seems no one in the world knew what would happen—or what to do. I’m told that at first, countless learned men came and went, as if they were carnival-goers vying for the high score at strongman’s hammer. Eventually, the number dwindled and I became just another curiosity, locked behind a steel door.

I’m told also that for 17 of those 23 years, I was tended by the same nurse. She rose every day to check on me before her morning meal, twice during the day, and once again before bed. For seventeen years. She wasn’t devoted to me. She couldn’t have been. She never knew me. She was merely faithful in her occupation. My own Florence Nightingale. And yet I never met her. She died of pneumonia some twenty months before I awoke, one more victim of a much wider epidemic.

The man who woke me, who discovered the means to push the eternal battle within me towards the white curse and against the black, was, of course, an American. It seemed in those days as if suddenly everyone was American. It didn’t matter if you were in Paris or Istanbul. They were everywhere, both on the streets and in the papers. They invented industrious processes and married old European aristocrats and invested incredible fortunes and lost them. They made motion pictures and jazz music and war. My American was Professor Henry Hunter, a classicist, which is to say a scholar of ancient literature. He was not a practitioner. Strictly speaking, he was a magus, an expert on magic—lost magicks in particular—and he had pursued the conundrum of my case as a kind of intellectual past time, the way a mathematician might become obsessed with a peculiar chess move, or a detective a cold case. I was a terrible mystery, it seemed. The sleeping beauty. The woman who could not be roused, who needed neither food nor drink, who simply rested—barring the rare bout of catalepsy—in a locked cell at the end of a long hall in a basement floor of a sanitarium, seemingly forever.

When I awoke, he was speaking to the nurse.

“Well,” he said, looking down at me through his wire-rimmed spectacles, “there you are.”

It may seem odd to say it, but I didn’t miss the years, at least not in themselves. I didn’t miss them for the same reason I had fallen easy victim to opium—and probably would to heroin or cocaine if I allowed myself to try. I have a surplus of days. They travel quickly in aggregate, yes, but ever slow in the singular. I would never have minded the ability to fast-forward a bit, to use a modern phrase.

Still, it was uncanny the way the world changed in my absence. I had seen automobiles in London, but they were, much like dirigibles, little more than a novelty, a new way for the rich to spend their millions. I had heard a phonograph as well. As a matter of historical record, Thomas Edison gave one to Madame Helena before she set sail for England and thence India. She kept it in the star-shaped library of Ardor House. But since the technology was terribly new, the quality was terribly bad. The first records didn’t play music—just random sounds: the honk of a buggy horn, the chirp of a bird, bits of human speech. It was a novelty, something to give the guests a giggle—that noises could be trapped in a box—and after clustering around it excitedly for a week, the bearded gurus and I never touched it again.

But when I finally awoke from my coma, cars choked the streets. Music—once the monopoly of the musician—played from every open window. There were machines to wash clothes, machines to refrigerate food, even machines to send messages through the air. It was as if the record of my life had skipped an entire song but kept spinning all the same, and the tune it played was all the stranger for it.

The biggest news, however, wasn’t industrial. In my absence, the warlocks had launched a major offensive, and the result was a world war. The conflict had stretched round the globe. Many wizards and millions of civilians had died. I couldn’t believe it. Truly, I thought someone was trying to trick me at first. It was easy enough to accept that a man could be so cruel, or a handful of them, perhaps even a nation, but this insanity had engulfed the species. It didn’t seem possible. What had gone wrong?

Dr. Hunter—“Hank” to those who knew him—arranged for me a convalescence at a “women’s home” run by a religious charity. It seemed that most of the women there had been with child or were escaping the fists of their husbands or fathers. A few were what today we would call alcoholic. As a condition of our board, the only responsibility my fellow inmates and I had was to follow the rules of the house, which were strict, but no more so than what I had suffered under the Countess Wachtmeister. Our time was otherwise our own, and I spent many hours confiding in Hank, either in letter or in person, the whole of my life’s story, pieced together over multiple visits. I needed to say it out loud, I think, if only to prove to myself that it was real, that it had all really happened.

It was on one such visit—after I told him for the fifth time that I could not stay in the women’s home any longer, that I needed to make my way in the world—that he told me he needed my help. The war had surprised everyone, he explained, even the High Arcane. No one was sure what was coming next. I promise you, the followers of the dark were never stronger, more numerous, or more openly influential than in the early decades of the 20th century. In response, a new organization had been created, of which Hank was a part, a kind of magical intelligence agency operating under Master Crowley, whose public shenanigans were nothing but a means of keeping the public focused on a fantasy, a cartoonish magic, and away from the truth, even as he carried it out right in front of them.

The organization was called The Winter Bureau, and its mission was to engage our enemies directly through subterfuge or even, where necessary, by means of the black arts, which were for all other persons expressly forbidden. Its aim was to discover, in advance this time, the enemies’ secret intents. Dr. Hunter had convinced Master Crowley that I was singularly qualified. I was attractive, he said, and skilled in the social arts, including deception. I spoke six languages, could pick a lock, use a knife, and quote classic poetry. I had more than a passing knowledge of magic, the maturity of age, and almost no fear of death. Indeed, I could be killed and still return with secrets.

I remember being somewhat surprised at my own resume as it was recited to me. I hadn’t seen myself that way. I was well over a hundred years old but still thought of myself as basically my father’s daughter, which is to say a fallen aristocrat, despite that by then most of the world I grew up with had completely disappeared.

For his part, it seemed Hank had caused something of a stir by waking me, which no one had thought possible. Indeed, it was his success, along with some of his scholarship, that led to his recruitment. My case was trickier. Technically, I was still a criminal, but rather than return me to Everthorn, Hank convinced Master Crowley to apply my years in coma as time served and to commute the remainder of my sentence if I agreed to join The Winter Bureau and work for The Masters as a spy.

I agreed, of course. I felt no loyalty to my superiors, but I did to the good Dr. Hunter. He was a decent man. An honest man. More than that, he was an optimist, like any good American. Unbounded optimism bloomed in the New World as nowhere else. Americans do not see the world as it is, which often makes them seem clumsy or naive. Rather, they see the world as they want it to be, which is why they have been so successful in making it so. And in those days, I needed to believe we could win. That the world could go off and get itself into such trouble in my absence made me question my faith in our very humanity. If the 20th century proved anything, it’s that cruelty and rationality are not bitter enemies, as had been assumed at least since Plato, but in fact the best of friends. I knew that I had no chance of believing we could win, of holding on to hope, anywhere but in the good doctor’s company.

He was a sharp fellow, after all, and very convincing—a bit bookish perhaps, but in a way that you don’t find much anymore. He wasn’t, as we might say, a geek. He was an athlete as well as a scholar and had nearly competed in the 1920 Olympics. He was a fit, vigorous, studious young man who had rowed competitively for Harvard. He was by no means a fighter, like Durance, nor a firebrand like Wilm Castleby, but then, Hank Hunter could throw a punch when he needed to, and he could rally troops to cross a beach if it came right down to it. He could read and write almost every ancient language known, and even a few that had been forgotten. He enjoyed his old books immensely but never more than people. He didn’t drink, except for the occasion celebratory toast. Yet, if you played the right tune, he would dance like Fred Astaire. If he had a fault, it was most certainly his naive honesty, which is a poor trait for a spy and one that got us both into trouble on numerous occasions.

My time with Durance aside, I had never thought of myself as particularly deceitful, not by nature, but in Hank’s company, it became necessary—even fun—to indulge that side of me. During our many adventures through what became “the radio era,” we made quite the pair, a fact made known the high society of Berlin one evening in the early 1930s when he and I came down the grand staircase at the same time, he from the right, me from the left, both in our formal wear. He was in pinstripes. I was in a slim lipstick-red dress. The room practically fell silent as we lightly joined the gala. That is how I will remember him always, as that dapper young man, hands in the pockets of his jacket, slight smirk hanging below blushed cheeks. He had forgone the wire-frame glasses that night at my request—we were, after all, undercover—and while dancing, he tripped and fell over a crystal punch bowl at just the right time to avoid getting shot. The crowd broke into screams and we were off.

Still, as dear to me as he became, I made absolutely sure that we were never more than most excellent friends, and I know for a fact he was conscious of the same—because he told me so. He didn’t say why, but he didn’t have to. We both knew we would be terrible as romantic partners, which is to say I would be terrible for him. Dr. Hunter was wise in the ways of the world, a true statesman, but he was ever hasty in the ways of the heart. Hank needed someone like him, a good woman of stout conviction with firm stature and broad hips with which to bear him many children. He found exactly that in Nancy Willard, a sweetheart from his childhood days, with whom he kept in constant contact—a fact that often put her in direct danger from our enemies. Had I ever conspired to take her place, I could’ve done nothing but hurt him.

In its mission, our new organization was both successful and not. We missed the stock market crash but correctly reported that the seekers of the dark were orchestrating the Nazi rise to power, although that knowledge did little to alter the course of events. The Masters had paid too much attention to their enemies, to Rasputin in particular, and not enough to their allies, who failed to act at decisive moments to stifle the threat. The rest is quite literally history.

After the war, thinking peace was upon us, Hank and I retired for a time. He married Nancy and started a family—a bit late, perhaps, but I was happy for him. I visited the couple at their home in Chicago whenever I could, but I never stayed long. Although she was only ever polite to me, Nancy was a straightforward woman from the middle of the continent who didn’t quite know what to make of her husband’s relaxed, casual joking with a foreign woman who always dressed sharply and who never seemed to grow a wrinkle. Rather than create trouble for my friend, I kept my visits brief and always withdrew without warning, as if to underline what an irresponsible person I was. Truth be known, I was jealous—not of Nancy, per se. Rather, of the both of them. Seeing the happy couple and their young children stirred something in me that I hadn’t felt before, and I did my best to ignore it.

As it happened, our parting was brief. We were revived by The Masters in the middle of the century. After conventional warfare had failed, Hitler’s sponsors turned to more directly occult mechanisms. Before the war, casting darkness—which is to say hiding objects or people in plain sight—had required an experienced warlock, someone to perform the ritual, as well as the Necronomicon itself, from which the darkness emanated. As such, our focus in the 20th century had shifted from elimination of the book—which had eluded us for decades—to the elimination of the senior warlocks such that there would be too few of them to use it effectively. The warlocks distrusted each other almost as much as us, which meant very few of them were ever allowed to set eyes on its pages. That gave us the edge. Our unity was our strength.

Of course, that meant Hank and I were, for all intents and purposes, assassins—even where we didn’t pull the trigger.

After the war, a black magician named Zaragoza, an acolyte of Rasputin, developed the means to imbue the power of the book within specially designed objects—amulets, mostly—such that they could cast the wearer in darkness indefinitely and without need of a talented magician. Suddenly, everything changed. Agents of the dark, though depleted in number, could now move about in secret as never before. Almost overnight, half of my colleagues were murdered in their beds, along with their families—including many children—and finding and destroying the book once again became our organization’s singular mission.

As the surviving members of The Winter Bureau reassembled in a secret chamber, families in tow, I remember asking the aged Master Crowley why we had ever stopped seeking it. I was told that what was done was done and that right then was not the time for questions and that the focus had to be on our own preservation. I suggested to him that in my experience, that’s all anyone ever focused on, preservation—if not life then wealth—which is why both were constantly imperiled. No one lifted their head from the counting desk long enough to see what was coming. Only I didn’t say it very nicely, and Master Crowley warned me never to speak to him that way again. His words and demeanor suggested I was, to him, still nothing but an accursed freak, and a criminal: a mizzen, a thief, and through my association with HPB, a heretic as well.

I suppose I was becoming disillusioned. I was starting to understand why it was The Masters had been so long unable to deliver the warlocks a knockout blow. Still, leaving America to join the fight was convenient for me. I had no family to protect, and my adoptive home was becoming ever more hostile to anyone of Russian ancestry. But I begged Hank to stay. He was then past 50, and I tried to impress upon him the immense value of what he had. But then, one would sooner convince the tides not to turn than Henry Hunter to forgo his duty, and after seeing Nancy and the kids placed into hiding, once again we were off.

It wasn’t the same, which he appreciated immediately. He was heavier and grayer and used to life as a suburban father and teacher, and our enemies were desperate and vicious and nimble as never before. (Only I was the same—always ever the same.) On our second mission, we met young Beltran, gregarious and cocksure. He kissed my hand wearing an amulet of steel and obsidian, and of course that fur hat that made him seem ten feet tall. He was barely twenty, and I laughed. We met him again a few years later when he was our contact in Turkey on the fateful trip that saw the gray-haired Dr. Hunter shot by Zaragoza himself.

“Stupid, stupid man,” I chided as I frantically tried to stop the blood from pouring from his chest. It covered his shirt and my hands and arms and everything.

We were on the floor of a truck which shook violently back and forth as young Beltran, behind the wheel, weaved at speed through traffic and secured our escape.

“I know,” Hank said, smiling up at me. “Tell Nancy—”

They were his last words.

I was stunned.

I realized that day the true weight of my curse, for some part of me died with Professor Henry Hunter. I could imagine that, in time, the rest of me would as well—all the parts that mattered, anyway—and I would walk the world a zombie. Or worse, as a wicked, uncaring thing.

My dear friend had stepped in front of the bullet, you see, which had been meant for me. It had been enchanted. No one knew whether or not it would work, whether it was finally the thing that could kill me, whether it would send me into another coma, or whether it would do nothing at all. I remember pausing for the briefest of moments at the sound of the shot. I saw it coming, and a fleeting thought took me.

Perhaps I wanted to find out.

Of course, by the cold calculus of fate, Hank should’ve stayed put. There was at least a chance I would survive, whereas by stepping in front of it, his fate was sealed. But in those moments of life and death, we act without thinking. It’s when our true characters are revealed, a lesson I would learn again some years later while in the company of a bald man from the Amazon.

I was devastated. Shocked. Silent. I wanted to deliver his body to Nancy in person, to explain that her husband had died a hero—and perhaps to let it be known that I had asked him not to leave his family. I suppose I feared that she blamed me. It’s natural in such circumstances for a spouse to wonder if, perhaps, there wasn’t something more to our relationship, something that compelled him to go. I wanted her to know Hank was just as she knew him: a soldier and a gentleman to the very end.

But I was denied entry at the border. Now a superpower, almost against its will, America was beginning its long turn away from the freedom of its youth. It’s still turning.

I wanted to grieve but Hank’s death, along with several others, had left us critically shorthanded. We were in real danger of losing everything, not just our lives but the world itself, so within days of his death, I was given new orders: an urgent mission, an impossible mission, one that made it clear both how desperate we were and how expendable I was, even to the point of damnation.

Beltran, who had helped me transport Hank’s body across the ocean out of sheer respect for the man, warned me not to accept, just as I had warned Hank. He said we should run.

“We?” I asked.

It seemed so presumptuous. I felt I barely knew him. In my grief, I hadn’t yet noticed how Beltran looked at me when my eyes were turned. I told him there was no “we” and that I was going to complete the mission, as ordered, but not for The Masters. Nor even for the world. I would do it for my friend, because that’s what he would’ve wanted me to do. I never saw Nancy or the children again.

Winter of the following year, haggard and alone, I was on a train through the Urals. It was a ride that I will never forget—quite possibly the defining moment of my long life, the fulcrum on which it all balanced. I traveled under a fake identity and didn’t dare leave my locked compartment. In my hands I held the most wanted item in the entire world. The most wanted item in the history of the world.

A book.

A book that should never have been written.

I was rushing to meet Beltran, who had been my handler from afar. If I didn’t reach him, the fate that awaited me . . . Well, I’ll simply say that immortality truly can be a curse—like the endless hours in that attic in Whitechapel, starving and alone with a corpse, when all I wanted was finally to die. That is the fate I risked, a fate worse than death: eternal damnation.

When I found Beltran, all Hell was at our footsteps. The horizon itself was dark as if at the approach of a violent storm. Thunder cracked—

July 31, 2018

Visual Storytelling

This digital painting by Christophe Young is called “Post-Race Breather” and I chose it because it’s a self-consciously sexy image. This to me is an example of doing it well.

Presumably this woman has been racing inside some sci-fi mecha or spacecraft, and she’s quite hot. She’s sweaty and exhausted from being under that helmet in some kind of cockpit moving at ungodly speed. What’s more, unlike many images, her breasts, while full, are not overly large, and she’s showing less skin than you’d see at the beach. The artist uses her form-fitting suit, practical attire for a sci-fi racer, to reveal her taut muscles.

What’s more, her pose is blatantly sexy, but it’s confident. She’s not covering anything coyly. She’s not peeking coquettishly at the viewer. She’s fucking tired, and she’s collapsed on the ground and she doesn’t give a shit if anyone’s looking. Indeed, her eyes are closed. Her head is up, indicating that exhaustion, but in a way that could be indicative of something else, especially in conjunction with her spread legs, to which the dual-tone of the suit expertly directs our eyes. And then there’s the way the knobs of the suit grip her torso.

I’m heard to say many times that there’s nothing wrong with depicting either gender sexually. The problem is depicting one of them predominantly that way and in lieu of any other aspect of our humanity, of which our sexuality is one. In other words, the problem isn’t within any single image — despite the recurrent cries that pop up on the internet. It’s in the collective mass.

However, that doesn’t mean there aren’t better and worse ways to go about it, and if you’re going to do a “sexy sci-fi girl,” it seems to me this is one of the better. This image is blatantly sexual. You’re meant to imagine more. But the subject is not simply a sexual object by virtue of her being but by virtue of her doing. She’s sexy because, whether she won or lost, she’s a confident, athletic competitor — of course, with an amazing body.

[image error]

July 30, 2018

(Fiction) The Ghost in the Labyrinth

After Beltran’s visit, some of my restrictions were lifted. I was not allowed to speak to Etude, and I had no idea where in the cavernous dungeons he was being held—the same dungeons where the Eye was discovered some seven centuries before. I was also kept from the high towers, where everything important seemed to happen, but there was a garden in a square left open to the sky, and I was allowed access to it and the library, my one luxury. It was utterly, unspeakably magnificent and so large that one could easily get lost. I was never a scholar like Hank, but being raised in the centuries before television, books have remained my first love. I spent many, many hours between those stacks in the company of ghosts who would sometimes steal one of my treasures when my back was turned—at least, until I learned to be more cautious and to feign interest in books I had no intention of opening again. Their thefts were an attempt, I’m sure, to get me to go innocently searching, to explore the dark archways, caged nooks, and octagonal chambers that abounded at all levels of the library. It wasn’t explicitly a labyrinth, but it was certainly labyrinthine. I was sure that through at least one of those arches—which were especially numerous at the lower levels, full as they were of columns holding the whole of it aloft—I could fall into the shadow realm. The dead are often attracted to the living, to the signs of life, to mirth and breath and joy and pain, which they do not feel, and they will try to take it if they can.

I made acquaintance with one—if one can have a ghost for an acquaintance. The dead are disembodied and not at all rational. Their world is memory, and they speak in dreams. Judging from her dress, which I only caught in glimpses between the shadows, my girl was a servant in the time of Napoleon. She must have spent much of her life scrubbing the floor, for that is what she did compulsively. When she spoke, it was always to herself or to someone else not present—in French. I heard only fragments of stories, and she would often disappear midway through. Sometimes she would glance at me first, suddenly, as if just realizing I was there before blinking away in fright.

But as one week turned to two, and two to three, my continued presence in the library coaxed a certain calm from her, as with a tiger, and she told me stories. She didn’t tell them to me directly, but if I sat and read near the lower arches—which were close enough to the water that I could hear the echo of gentle lapping in the near-total silence—she would often appear after a time, scrubbing the floor—always scrubbing, scrubbing—and start talking to herself, which was of course talking to me. I would put a finger in my book and close it and look away from her, to the floor, and listen to her tell her friend Charlotte all the reasons why she had best stay away from the farm boy down the lane, for he was a ne’er-do-well if ever there was one. I would listen to her argue with a man—a father, perhaps, or a lord—about why she hadn’t cleaned the kitchen or brushed the horses. She told a great many lies, especially about where she went when she wasn’t needed and why it is she lingered so long there.

How she came to the Keep of Solomon, I can only guess, but the reason for her departure from her home seemed clear. Her dalliance with the farm boy down the lane had turned sour after she caught him mounting her friend Charlotte behind a tree. Realizing he had no intention of honoring his promises, she planned to visit a “lady of the dells”—a witch—to procure her revenge. But that required a day’s travel, round trip, and servants in those days did not have week-ends. She managed to secure permission through a clever deception involving a prized mare and the “accidental” throwing of a shoe. She was to take the animal to town, and since travel then was risky and roads sparse, schedules were always imprecise. It would’ve been easy for her to take the necessary detour, especially since she would not actually have to lead the animal on foot, as her master thought, but would be able to ride it bareback. I suspected the money he gave for the shoe, which she had removed and later replaced, would go to the witch as payment for services.

Everything went well until the eve of her departure, when Charlotte either discovered the truth or guessed it and informed their master. Although my young acquaintance didn’t say, I’m sure she was sent away after that and eventually came in service to The Masters, where she met her end within the walls of the Keep of Solomon—through violence, one would guess, since she remained there as a wayward spirit. Whatever had happened, she didn’t speak of it, merely of her love for the farm boy, through which I could discern the sense of utter worthlessness she felt when she saw him grunting and thrusting into her friend.

I think she was also worried for me. I think she understood I was a prisoner of some kind. I think she was also jealous, as the dead often are of the living, as well as angry at what had happened to her, and sad about it as well, and all of those emotions played out in her speech, sometimes across a span of mere sentences.

One day, while she was scrubbing the floor and telling her friend Charlotte how beautiful she was and that she could do so much better than a simple farm boy, I heard the words “don’t trust him” in between the rest. They were out of place. They were spoken in the same voice, but the tone and cadence were different, as if they had been interjected from a different time and place. I looked up and the young woman was peering at me. She was speaking gaily to her friend Charlotte, but her eyes were on me.

I nodded, and she disappeared again.

July 29, 2018

The Brilliant Worlds of Francisco Badilla

July 27, 2018

The Glitchy Duplicity of Illustrator Lynn Nguyen

Lynn Nguyen’s “glitch” art reveals the duplicity of human psychology in the era of high technology. Her subjects’ reflections and GIF-based glitches reveal a darker truth to our tender moments. Click for larger image.

July 26, 2018

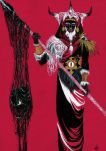

The High-Fashion Occult of Luciana Lupe Vasconcelos

Luciana Lupe Vasconcelos (b. 1982) is a self-taught illustrator and former tattoo artist from Brazil whose highly stylized works explore motivating mythos of dark ritual, often with the brilliantly simple color scheme of black and blood red.