Rick Wayne's Blog, page 68

October 15, 2018

Studio Peregalli’s Ultimate Reading Room

Italian company Studio Peregalli, specialize in old European style. Appropriately, their website is a single static page. If you want to hire them, you have to call or visit. http://www.studioperegalli.it/

It’s cold here. Pull up a book.

Now, then, I was again happy: I now took only 1000 drops of laudanum per day: and what was that? A latter spring had come to close up the season of my youth: my brain performed its function as healthily as ever before: I read Kant again; and again I understood him, or fancied that I did. Again my feelings of pleasure expanded themselves to all around me: and if any man from Oxford or Cambridge, or from neither had been announced to me in my unpretending cottage, I should have welcomed him with as sumptuous a reception as such a poor man could offer. Whatever else was wanting to a wide man’s happiness,–of laudanum I would have given him as much as he wished, and in a golden cup.

–Thomas De Quincey, “Confessions of an English Opium-Eater” (1821)

October 13, 2018

Ignacio Cobo’s Tarot

Ignacio Cobo is an artist from Santiago, Chile who uses digital collage to make novel tarot cards out of old art. His “deck” eschews traditional major/minor arcana in favor of loose associative representations and a simple numbering system, which I think gets to the symbolic heart of the system.

October 11, 2018

The Mystery of the Arnolfini Portrait

Contemporary artist Theo Vandor has painstakingly removed the figures from Jan Van Eyck’s 1434 masterpiece, commonly known as “The Arnolfini Portrait,” which depicts a wealthy Italian merchant and his (eventual) wife in their home. Painted on an oak panel, it is widely considered one of the most mysterious works in the Western canon.

Contrary to common perception, the woman in the original, reproduced below, is not pregnant. At the time, it was common (if not fashionable) for women to lift their bulky dresses that way.

[image error]

The couple is reflected in the curved mirror on the back wall, above which are the words “Jan Van Eyck was here,” the painter’s highly unusual signature. If one looks closely, you can see the artist himself reflected as well, in a move similar to what Velázquez would later do in his 1656 masterpiece, “Las Meninas.”

Scholars and art historians have long speculated as to the point of the reflection, or the unusual note on the wall, or indeed the entire painting. Once thought to be commissioned as a kind of marriage certificate, it was later discovered that Giovanni Arnolfini didn’t marry until 13 years after the painting was made, six years after Van Eyck died. Since then, no one is quite sure what to make of it.

Why the mirror? What is the purpose of the discarded shoes? Why is the gentleman holding his lady’s hand that way? Why commission a painting if they are not married?

Hannah Gadsby, Australian comedienne of recent Netflix fame, apparently studied art history and wrote about the painting for The Guardian a couple years ago. Spoiler: she’s just as perplexed as the rest of us.

In the contemporary remake, the artist has removed the figures not only from the foreground but the mirror as well, and perfectly filled the interior in an exact replica of Van Eyck’s style. What remains is an utter hollow, an absence that is haunting, even if one has never seen the original, deepening the mystery.

In the mirror, which should contain our reflection, now there is nothing.

What exactly is this painting about?

[image error]

October 9, 2018

The Far Away Fantasy of Ghostbow

Alexandr Komarov, AKA Ghostbow, is a digital painter from Ukraine who makes classic, high fantasy paintings elves, dwarves, dragons, adventurers, and deep forest gods. You can find more by the artist on his DeviantArt page.

October 7, 2018

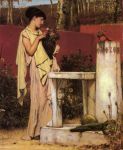

Sir Lawrence, the worst artist who ever lived

Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912) was a Dutch-born British artist who became one of the wealthiest painters of the 19th century. A talented marketer as well as painter, he anglicized his name from Laurens to Lawrence so he could be better remembered in the English-speaking world. He also added the forename Alma so that he would appear near the top of alphabetized lists — the equivalent of calling your business AAA Plumbing in the days of the phone book, or SEO today. He also invented an innovative numbering system to make it hard for forgers to pass off fakes as his genuine work — a kind of basic copy protection.

[image error]The Vintage Festival (1870)

Although wildly popular in his time — he was knighted in 1899 — today he remains largely unknown outside the art world. Indeed, his works were almost completely ignored until the 1950s, when they found commercial use as inspiration for set design and matte painting for blockbuster movies such as Cleopatra and Ben Hur. While making The Ten Commandments, famed director Cecil B. DeMille would regularly look at prints of Alma-Tadema’s paintings, inspired by Alma-Tadema’s ability to create personal drama within a grand, wide-angle perspective. His paintings can look to us like stock images of the past because stock images were created from them by popular films.

That “wide-angle drama” that so inspired DeMille is part of Alma-Tadema’s genius. Classic depictions of important historical or religious events, such as the finding of baby Moses in the reeds, are typically full of rage and portent, where even the people depicted clearly have a sense of the future importance of their acts, and in that way, they are distant from both us and from themselves. As players of predestination, their destiny is inescapable. Indeed, most of them are doomed.

The people in Alma-Tadema’s work, however, look very much like people today, or any day. In his depiction of the discovery of Moses, for example, several of the porters conveying the queen on her caravan are clearly bored or annoyed or their attention is otherwise drawn elsewhere. Thunder doesn’t break in the background. Angels do not sing on high. There’s just a foundling in a basket — a not altogether uncommon occurrence in the old days — which some rich woman has taken a fancy to, because she can.

[image error]

If this were a Renaissance painting, you would be able to draw straight lines from the eyes of all the figures which would converge on the baby Moses at the vanishing point. Here, even the women carrying the basket seem to care less about the baby than how they’re going to get him up the approaching bank.

[image error]Despite that his paintings were used in movies into the early 60s, Alma-Tadema remained gauche in the art world. His works were not exhibited and dealers, who had once paid large sums to acquire them, let them gather dust in basements. Sir Lawrence was, in a sense, a victim of his own success. Seeking to ride his coattails, marketers in the early 20th century copied his style on everything from perfume advertisements to the cover art on boxes of chocolates. Once so breathtaking, his work became associated with a vulgar commercialism. Seeking to avoid the stigma of association, collectors no longer displayed his works in their homes or galleries, and he became all but forgotten.

Unlike Van Gogh, who enjoyed no commercial success in his life but who challenged and ultimately changed the art world, Sir Lawrence’s art merely depicted culture rather than provoked it. His paintings, while technically advanced and visually stunning (especially when seen in person), did not inaugurate a new style or epoch. They merely epitomized one. And in that way, they didn’t serve the needs of the elites — critics and art historians — who are the retrospective arbiters of “good taste.”

Alma-Tadema was rediscovered and resurrected by one man, fellow millionaire marketer Alan Funt, creator of the TV show Candid Camera and one of the founders of what we now call reality TV. While browsing a private art gallery one day in 1967, Funt was approached by the dealer, who asked if he’d like to see something by “the worst artist who ever lived.” The man then produced Alma-Tadema’s “The Voice of Spring” (below), and Funt bought it on the spot for a steal.

[image error]

Funt went on to collect a number of Sir Lawrence’s paintings, only to be forced to sell them in the 1970s after discovering that his accountant had embezzled $12 million. Bankrupt and facing large debts, he liquidated his art collection, but by then, interest in Alma-Tadema had revived and Funt cleared something like half a million dollars on his paintings alone — quite a lot of money in those days and orders of magnitude more than he had paid.

The painting below, for example, “The Roses of Heliogabalus,” was purchased from the painter by Sir John Aird, 1st Baronet, for £4,000. It depicts an apocryphal episode from the life of the Roman emperor Elagabalus, also known as Heliogabalus (204–222 AD), as related in the “Augustan History.” The emperor unexpectedly dropped “violets and other flowers” on his guests from a false ceiling in such quantity that some of them were smothered to death.

[image error]

After the artist died in 1912, the painting was displayed publicly (for the last time until 2014). After Alma-Tadema’s reputation plummeted, the painting was sold by the 3rd Baronet in 1935 for 483 guineas. It failed to sell at auction in 1960 and was “bought in” by Christie’s for 100 guineas.

In 1973, Funt sold the painting at auction for £28,000. American collector Frederick Koch acquired it later and sold it in 1993 for £1.5 million.

Still, even with his reputation revived, Sir Lawrence is largely unknown today outside the art world. I suspect that’s because, first, Hollywood co-opted his style into a visual language that is well-known to us, which makes it no longer novel or interesting. Even though Alma-Tadema based his images on the best archeology of the time, we’ve since learned better, which further adds to their apparent quaintness.

Second, his paintings frequently depict people and scenes from the ancient world, which, while part and parcel of common education at the time — and therefore as recognizable to Sir Lawrence’s audience as, say, a painting of Eowyn and the Witch King would be to us — are nevertheless completely foreign to most people today. We can look at his paintings and recognize that these are Greeks or Romans, but there is no “a-ha” moment of recognition. We have to be given the context.

This, for example, is “Caracalla and Geta: A Bear Fight in the Coliseum” (1909). Odds are, unless you have a classical degree or a hard-on for Roman history, you don’t know who those people are or why it matters they’re about to watch a bear fight.

[image error]

Caracalla and Geta were brothers. After their father died, they rules as co-Emperors of Rome — for all of one year, that is, until Caracalla (188-217 AD) had his brother killed. The men were, along with Elagabalus, members of the Severan dynasty, which was the last patrician family to rule the empire. Fifty years of political chaos followed their fall in 235, where a variety of rebellious generals, warlords, and rich men made successive claims and counter-claims to the throne. Some lasted no more than a few days.

The next strong emperor, Diocletian, who ruled from 284-305 AD, was born in Dalmatia (present-day Croatia) to what we might call a “middle class” family. The bear fight, then, is not just another spectacle of cruelty common in the empire, although it’s that, too. In fact, given that bears are not literally depicted, the actual bear fight — the spectacle for the audience of the painting, as distinct from the audience in the painting — is the muted conflict between the two brothers, itself symbolic of the inter-family fighting that plagued the Severans and ultimately brought low the entire Roman aristocracy.

Look at the painting again. The woman at the center, possibly the boys’ mother, gazes directly at the viewer with a look of concern, as if troubled by the hints behind her sons’ competitive banter. Of course, if you don’t know that, it just looks like a pretty picture.

Have some more. This is “The Education of the Children of Clovis.”

[image error]

October 5, 2018

The Neo-Art Deco of Mike Mahle

Mike Mahle’s mixes classic art deco illustration with the solid colors of contemporary animation, often depicting, as he calls it, “sirens and superheroes,” but also quite a few classic book covers. Check it out.

October 4, 2018

Let me put your flowers on

[image error]

Holyday (1876) by James Tissot.

“Autumn is coming, the leaves of the large chestnut tree are changing color, but the rest of the vegetation is still green and luxurious. On the right is the painter’s wife, Kathleen Newton, who appears to avert her eyes from the scene. The men in the painting belong to the well-known I Zingari cricket club, judging by their yellow, red and black hats. The women are overdressed, one of Tissot’s idiosyncrasies. The influence of Manet can be recognized, also in the choice of subject, reminiscent of his Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (The Luncheon on the Grass). However, Holyday does not provoke but is suffused with a British conservatism.” [Wikipedia]

Words by Nayyirah Waheed.

October 2, 2018

Sex, Lies, and Oil Paint

Georges-Antoine Rochegrosse’s “The Death of Messalina” (1916) is one of those paintings you really need to see in person to appreciate. Your eyes need to be able to focus on the various components separately — the anger of the soldier as he grips her hair, the patrician’s douchebro smirk as he grips the execution order, the way the soldiers stand like an audience at an outdoor theater, how the only other woman (also the largest figure, dressed in black in contrast to the patrician’s white toga) is also the only one not watching.

Messalina (c. 17/20–48), third wife of the Roman Emperor Claudius, whom she married at 15, is infamous in history for her insatiable promiscuity, ruthless persecution of rivals — particularly other women in her family — and for her ability to manipulate her husband.

If the historical sources are to be believed, Messalina had Senator Appius Silanus killed simply because he spurned her advances, choosing instead to remain faithful to his wife. Messalina conspired with a freedman, Narcissus, where both separately reported to Emperor Claudius that they’d had a dream about Silanus in which he tried to kill the emperor. Seeing this as evidence of portent, Claudius had the man arrested when he innocently showed up later that day, presumably summoned by the Empress.

Messalina reportedly had one of her husband’s secretaries poisoned after she became bored with him as a lover and wouldn’t suffer the risk that he might reveal their dalliance in the future. She had another lover, Publius Suillius Rufus, prosecute a fellow senator on charges of “failing to maintain discipline amongst his soldiers, adultery, and engaging in homosexual acts,” supposedly because he offended her.

(Contemporary propaganda sometimes suggests homosexuality was practiced openly and freely in the pre-Christian world. The truth is significantly more complicated.)

But Messalina seems to have reserved her deepest animosity for her niece by marriage, Agrippina the Younger, who she persecuted for years. Agrippina’s son, Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (later the emperor Nero), received more applause at the public games than her own, Britannicus. The persecutions only ended when Messalina became distracted by a new lover, which was to be her downfall.

Messalina became so infatuated with the man, Gaius Silius, a famously attractive consul-designate, that she married him when Claudius was away. Her reasons are not well understood. The freedman Narcissus, with whom Messalina had conspired before, told the Emperor that this was the beginning of a plot to replace him.

The painting above depicts Messalina’s execution for the crime, although of course it did not happen this way. In fact, according to our sources, Claudius was not at first inclined to kill his wife. It was Narcissus, pretending to carry orders from the Emperor, who ordered the Praetorians to execute her. In that way, she may simply have been outwitted to her death as she’d done to so many others before.

Upon hearing the news that his wife had been killed, the Emperor apparently showed no reaction, but simply ordered another glass of wine.

In subsequent generations, Messalina became the archetype of the wanton and destructive woman. However, we have reason to doubt almost all of what comes down to us.

Two of our biggest sources, Tacitus and Suetonius, wrote 70 years after the events in an age generally hostile to that entire imperial line, in much the same way that the Tudors did everything they could to smear Richard III — giving him a physical deformity, a hunchback, and telling everyone that he killed his own nephews, the rightful heirs, none of which is true.

(As I’ve mentioned before, Richard was actually G.R.R. Martin’s inspiration for Ned Stark, the man noble to a fault.)

We can similarly doubt Pliny the Elder, who reports in Book X of his Natural History that Messalina once engaged in a 24-hour sex competition with a famous prostitute and that she won by bringing a total of 25 men to climax.

Ridiculousness aside, it is highly unlikely that Messalina was virtuous or an innocent victim of history. She almost certainly took lovers and almost certainly had people murdered for no good reason. In that way, she was no different than the rest of her family, which is why there was so much hostility toward them in the later empire. Messalina’s cousin was the famously perverse Caligula, for example, and although it’s unlikely that her nephew Nero actually played the fiddle while Rome burned, that such a story comes down to us tells us much about what people thought of him.

It’s hard to say Messalina has suffered any worse at the hands of history than her male peers, almost all of whom are remembered as weak or vile. Yet, there’s certainly no question that for Europeans of the Christian era, Messalina’s sexual perversions, however much they actually existed, are relished as an abomination.

“To call a woman ‘a Messalina’ indicates a devious and sexually voracious personality. The historical figure and her fate were often used in the arts to make a moral point, but there was often as well a prurient fascination with her sexually-liberated behavior. In modern times, that has led to exaggerated works which have been described as romps” [Wikipedia] where viewers are invited to shake their heads while secretly enjoying graphical depictions of her immoral acts.

This painting is not one of those romps, but knowing now the background to the work, note the peculiar savagery and satisfaction with which the men punish her. It’s almost pornographic.

And here you thought old art was all boring and shit.

[image error]

October 1, 2018

Ereshkigal, Queen of the Underworld

Ereshkigal , Sumerian goddess of the underworld, was also called Irkalla, the name of her land, in the same way that in the Greek, Hades is both the name of the realm and its king. Compare to Hela in the Norse pantheon or Persephone or Hecate in the Greek.

Ereshkigal was the older sister of the beautiful Inanna, worshiped later by the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians under the name Ishtar. Inanna was called “the Queen of Heaven,” despite that she was not married to Anu, the sky god and supreme deity, for she was the goddess of love, beauty, sex, war, and power (as in political power), which tells you what the ancient Sumerians thought of those things. Inanna was famous for, among other things, going to war with a mountain because she feared it was more majestic and beautiful than she.

One day, Inanna showed up, as younger siblings do, outside the front door of her sister’s kingdom, demanding to be let inside, presumably with the aim of extending her dominion there. (This didn’t have to mean killing Ereshkigal. Maybe Inanna just wanted to strut around giving orders. Sadly, the text doesn’t say.) Unwilling to be humiliated in her own land, Ereshkigal orders the seven gates of the underworld sealed, but tells her gatekeeper, Neti, to open each, one at a time, if Inanna removes an article of clothing. The goddess does so, and after passing all seven gates, Neti brings Inanna naked and powerless before Ereshkigal, who calls forth the seven judges of the underworld, who weigh men’s souls. A trial is held, Inanna is found guilty, and her body is impaled on a hook, where it is left hanging for all to see — which pleased Ereshkigal, I’m sure.

Seeing this, Innana’s minister, the messenger goddess Ninshubur (sort of a cross between Hermes and Cupid), flies swiftly to Enki, god of creation, crafts, knowledge, water, and mischief, and begs him to free her queen. Enki, who had a wife but who always liked a pretty face, agrees and creates from clay two sexless beings who can pass through the seven gates unseen, and they retrieve Inanna’s body and steal it back to heaven, where the goddess of love and war comes to life again, in all her radiant glory.

Furious that the laws of her land — the laws of nature — have been broken, Ereshkigal orders Neti to throw open the seven gates so that Irkalla maybe emptied, and an army of demons and shades flies forth.

In the Sumerian tradition, as in the later Greek, a soul could not leave the underworld unless it could find another to take its place. Seeing the armies of the underworld screaming toward heaven, Inanna runs to her husband, only to discover that he has not, per tradition, been mourning the loss of his tempestuous wife. In a fit of anger, Inanna casts him down, into the hands of the demons, who drag him back to hell, where he forever takes her place.

According to Sumerian tradition, Inanna stands in heaven still, raining her capricious whims on mankind. Ereshkigal, however, is content with her dark dominion, for she knows — in time — she will be the queen of all.

cover image: Ereshkigal game art by Yigit Koroglu

Here are some other renditions.

September 30, 2018

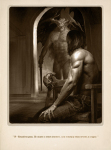

The Sex of Art (Very NSFW)

People don’t get Erotic Art.

To be clear, what I am calling Erotic Art is (capital A) Art first, versus mere pornography. That doesn’t mean Erotic Art is never pornographic, nor pornography artistic. Rather, pornography, as genre of (lowercase a) art, is fundamentally commercial. It is meant to titillate, to get you off.

Erotic Art has the same aims as Regular Art, whatever you believe those to be — to challenge, subvert, distort, whatever. It merely uses the sexual as a thematic or symbolic vehicle.

Erotica, which is aesthetic pornography, occupies the border. It is not Erotic Art, even though it often claims to be. The distinction, however, is hardly clear, and depending on the viewer, a work of erotica might function as Art, as pornography, or even as both.

Erotic Art is also not the Nude, which these days is as much landscape as anything else. Although at one time the preserve of goddesses and muses, both erotic and sublime, the female form is now so ubiquitous as to be mundane. It fills our magazines and TV screens. Indeed, there is a concerted political effort to demystify and debase it to its foundation, to “free the nipple” and turn the vagina into a mere organ, like the pancreas.

Ultimately, what is most erotic is that which is not seen, or which is glimpsed only. Hence it is increasingly not the female form but the erect penis — the last bastion of impropriety — which symbolizes the erotic.

(Fan fiction, which portrays, often graphically, a homosexual relationship between two otherwise straight male characters, is the male equivalent of the lipstick lesbian, a homoerotic fantasy to titillate the opposite gender.)

However, in as much as there seems to be an indelible link between it and fragility, beauty remains effeminate. Masculine beauty, which circumscribes a much smaller erogenous zone, is muscular and strong, never fragile or sublime — or if it is, it’s homosexual, or else a perversion.

The male organ is a required active participant in the physical act of love. Hence, the flaccid penis, peeking at the viewer from under a belly, is the antithesis of the erotic: the spent miracle, the false promise, the weakling.

Impotence, that uniquely male fragility, is never beautiful.

The following selections all come from the last couple decades. I’ve tried to represent several different mediums, from photography to painting to illustration. (There’s even a work of street art.)

As I’ve indicated, there are generally fewer depictions of men than women, and what’s out there is mostly homoerotic. There seems to be an assumption, as one female critic noted, that women don’t enjoy looking at naked men, fragile or otherwise.

The artists are:

Fabian Morassut

Ali Franco

Chiba Kotaro

AlphaChannelings

Ida Belogi

Kristin Liu-Wong

Harumi Hironaka

La Fleuj

Nancy Murrian

Robin Isely

Pogo Lin

Stephanie Sarley

Perry Gallagher

Tara Booth

Nikolay Tolmachev

Wishcandy

Tony Kelly

Yuji Moriguchi