Rick Wayne's Blog, page 77

June 11, 2018

Ejiwa Ebenebe’s body-positive Afro-fantasia

Ejiwa Ebenebe, who goes by the nickname “Edge,” is an illustrator based out of British Columbia whose work focuses on young women of color. Her subjects occupy positions of power and mystery in fantasia-like settings, where they almost always stare back at the observer in ways both indifferent and angry.

Ejiwa can be found on her website, artofedge.com.

[image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error]

June 9, 2018

The golden fantasies of Masaaki Sasamoto (NSFW)

Masaaki Sasamoto was born in Tokyo in 1966, graduated from the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music in 1989, and has been exhibiting ever since.

[image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error]

[image error] [image error] [image error] [image error]

June 8, 2018

The High Nordic Art of Viktor Vasnetsov

Viktor Mikhaylovich Vasnetsov (1848 – 1926) was a Russian painter specializing in mythological and historical themes and one of the founders of the nationalist romantic movement, the so-called “Russian Revival.” After graduating from the seminary, Vasnetsov moved to St. Petersburg, where he studied art at the Imperial Academy. Famed in his lifetime, he was given a noble title by Nicholas II just a few years before the revolution.

[image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error]

June 7, 2018

(Fiction) To catch a waking nightmare

Mr. Étranger watched her fly into the night. He turned to me.

“Do you know her?” I sniffed. My cheeks were red from running in the cold. I could hear a semi pass on the big freeway down by McDonald’s.

“We were lovers. For a while. You’d better come in. There won’t be much time.”

“With a raven?” I asked.

I walked in and he shut the door. There was flat carpet, the kind that people get when they’re afraid kids will spill stuff on it, and fake wood on the walls. There wasn’t any TV or anything. Just a single bed with a table next to it. And one lamp. There were boxes all around, just like the one with his books in it. Most of them were empty. Everything smelled like old cheese.

“That wasn’t a raven.” He shuffled past me toward the bed, which rested at an angle in the living room. “It was her voice.” He tossed the dagger onto it and laid down. “Ravens and magpies were often used as messengers. They are strong birds, both winged and intelligent.”

I saw the little totem pole on the table. The two pieces at the top were still blank. I looked at the kitchen, which was open to the living area. It didn’t seem like he had any food.

“How come you won’t eat?”

“I did something. Long ago. And I am trying very hard to make amends.”

He closed his eyes and I took a better look at him. He was so skinny I could see the skin of his neck throb with each heartbeat. “Is it working?”

He chuckled. “I won’t ever know.”

I knew what that meant. He had to die.

“Maybe I could help instead.”

He smiled. “You’re a good boy. And I have appreciated your company. More than you know. But you have enough to deal with, I think.” He raised himself up in the bed with a groan. “It’s an apparition. Your secret. A fear-eater. People think it haunts closets and the spaces under our beds, but what it truly haunts is our minds. We simply project our fears into those other places. And it feeds on that.”

He took a deep breath, held it, and let it out slow.

“Like a bogeyman?”

“Yes. That’s it exactly.” He was wheezing. I could hear it. “It is a bogeyman.”

I walked to the sink and got him a glass of water. All he had in any of the cupboards was a pack of red plastic cups.

“It will be close,” he said. “Every child it has attacked has been in your neighborhood, near the little forest behind your house.”

The hollow! That was it. That’s where I was when it attacked me. I felt better right away, and I thought maybe I was right to come for help, even though it probably meant Dad would send me away forever and I’d never see him or Mom or Wilson or Sudoku ever again.

“But you cannot sacrifice yourself like you did before.” He took the cup and took a drink. “It is not the creature you knew. It has been feeding. Growing strong.”

“What do I do?”

“It will be powerful. More powerful, I fear, than a child.” He looked at his shaking hands. He shook his head. He laid down. “And no one who can help knows I am here.” He chuckled. “That is why I came.”

“I can do it.”

He closed his eyes. “But you shouldn’t have to. Not by yourself.” He opened them again. “To trap a waking nightmare, you need a dreamcatcher. Have you seen one of those?”

I nodded.

He sat up. “This is a special kind. You will need many things.” He shook his head. “I don’t know how you will get them. I have no money. I have given it all away. And your father has fired me.”

“What kind of things?”

He tore a piece of paper from a junk mail flyer on the floor and found a pen and started to draw. I stood next to the table and watched. His hands were shaking so bad.

“A small hoop. As perfectly round as you can make it. Some string to weave and make this pattern. It looks complicated but it’s simple to make. Do you see? Over and under at each of these three points to make nesting triangles, like a funnel.”

I watched. I nodded again.

“Below it you must hang a symbol of the apparition you want to catch, such as a form it likes to take. You also need something shiny, to get its attention. It needs only to look. It is a dream, so one glance is enough to snare it.” He kept drawing with shaking hands. Then he got tired and had to stop. He was so weak. And breathing hard. “But most importantly, you will need a birthstone. To trap it.”

I looked at the pictures he drew in the blank space between the everyday low prices.

He leaned back against the fake wood on the wall. “What month were you born?”

“December,” I said.

“Of course.” He shut his eyes and breathed hard. “Do you know what turquoise looks like? It was prized by Native Americans.”

I didn’t respond. I was staring at the page. I had seen those things. Everything he had drawn. All of them. A ring. String to weave around it. Something shiny.

Everything.

It was the raven’s collection. She had brought me everything I needed to trap the fear-eater, the bogeyman. To thank me for saving her.

I pulled the blue pebble out of my pocket. “Is this it?”

Mr. Étranger froze perfectly still. He stared at the stone in my hand. Then he looked into my eyes. He was still. Then he said something strange. Something I didn’t understand. It was just a whisper.

“Every time I played the flute, you came . . .”

I looked at the picture he drew. I frowned.

“What is it?” he asked.

“I had everything. All of it. But I lost something. My dad took and threw it away.”

“Are you sure you don’t know where it is?” he asked.

I nodded.

“This is very important. Are you certain you aren’t just saying that? Are you certain it is well and truly lost?”

I nodded again. I tried not to cry. The white raven had given me everything I needed to stop the fear-eater, to save Trevor who didn’t say his S’s right, but I wasn’t strong enough to hold onto it all. I let my dad throw the Frisbee away.

I thought Mr. Étranger would be disappointed with me. But he wasn’t. He pointed to a coat hanging near the door. It wasn’t like any coat I had seen.

“Reach into the pocket,” he said.

“But my dad threw it away,” I said.

“Reach into the pocket,” he urged. “If it is truly lost, it will be found.”

I walked to the jacket. It was smoky colored and had big flaps in the front that closed with funny buttons. I reached into the pocket and felt a plastic ring.

I pulled out the Frisbee. It wasn’t a different one. It was the same kid’s size yellow ring with the broken hollow center.

I turned to Mr. Étranger.

“Good boy,” he said with a nod. “Well done.”

I put my arm through the ring like it was a bracelet. I folded the picture he made and put it in my pocket with the pebble. I picked up my backpack. I opened it and pulled out the snacks my dad had packed for me: fruit gummies and peanut butter crackers and a banana. I left them on the table next to the cup of water.

He just watched. “They brought me right to you,” he said, as if it were the most amazing thing he’d never considered.

“Who?” I put my backpack on walked to the door.

“Ólafur . . .” He looked at me intently. “Use the shell, the boundless ocean, as a prison, just as I have shown in the picture. Seal it with the stone. It will try to fill your mind with fear, then devour it whole. You must not succumb. Or you will be lost forever. Do you understand?”

Mr. Étranger had told me how to trap my secret. That meant he thought I could do it. No one had ever thought I could do anything. Not by myself.

“I can do it,” I repeated. “I promise.”

“It will not be so easy. The bogeymen attack children because they are vulnerable and easier to scare. A friend of mine lost his brother to a fear-eater—a young boy, no less brave than you. They are not to be taken lightly.”

I opened the door. He raised a hand in parting, like he was afraid he wasn’t going to see me again. Then he said, “Whatever I have left is yours.” His tattoos were almost gone. There was only one left, right in the middle of his hand: a perfect circle. I thought it had been in two halves before. But now it was whole.

I ran to the hollow. It was getting dark now. Adults were on the street with flashlights. And the police. They were looking for Trevor. I knew if they caught me they would take me to my dad. I hid in some bushes once. Then I ran some more. When I finally got to the woods, it was dark and quiet. I didn’t want to run in the hollow. I was too afraid I would trip, like before. I stopped and pulled the little key chain flashlight out of my backpack, the one I used as a night light when we stayed at my grandma’s. It was LED. It was bright. I decided I didn’t like the hollow anymore. It was too scary. I wished Wilson was with me. And Mr. Étranger. I wished my mom was home and my dad liked me. I wished my secret would go away and never come back. I wished I was strong enough to beat it. Maybe if I beat it, Dad wouldn’t worry so much and I would get to stay.

I walked through the gap in the ring of downed trees. The moon was faint overhead. Everything was so dark. And quiet. I took a deep breath. I could see the slim opening to the basement. Right away I knew it was inside. It had chosen the same place I had. A place adults didn’t know. Someplace dark. Someplace hidden. Someplace close to all the kids in my neighborhood. I looked at that dark hole. There could be anything inside. I walked forward. That’s when I saw something new resting on the dead leaves nearby. It was a dead rat. Someone had skinned it and left it sitting. They had burned a candle to its head, which left little spires like a crown. Above it, they’d folded green twigs back and forth together to make a kind of scaffolding.

And there was a wasp. A big one. As big as three of my fingers. It crawled over the back of the rat, antennae twitching. It saw me. I heard its wings buzz and it flew right at me.

The white raven snatched it from the air. She swooped to a nearby branch and swallowed it in one gulp. But she didn’t call. I think that meant we had to be quiet.

I held my breath.

I made fists.

I put the little flashlight in my mouth and got on all fours and crawled into the hole. I was just small enough.

There were wood stairs. I slid my feet around in front of me and stepped on the first and it creaked. I listened. But there was nothing. It was so dark. Like outer space but without the stars.

And quiet.

I climbed down one step at a time into the basement of the hollow. The stairs creaked as I stepped on them, and dust fell. The staircase ended before it reached the floor, like it had broken off. I had to jump a little ways. I waved my flashlight around. I was shaking. There were lots of dead leaves everywhere and some trash in the corners. Tree roots had grown down from above. Big ones. They twirled like fat snakes sprouting tiny hairs. There were cobwebs everywhere and little crawling insects on the walls like the ones you find when you lift a big rock, like the ones I had fed the raven when it was sick and hiding in the garage at my old house.

I was shaking so bad I could hear my teeth rattle. I slapped my hand over my mouth. I raised my flashlight. And there he was. Trevor. Lit by the round beam from my light. He was so small. I could see his face. His eyes were closed, but they fluttered like he was half awake. His head, arms, and legs jutted from a round, white sac hanging from the exposed roots. It was just like the sac spiders make. Only bigger. Big enough to trap a small boy. And it was throbbing.

The fear-eater had laid eggs. Its young squirmed inside. I looked around but I didn’t see the monster. But I saw my plastic bag a few feet away. I had missed it at first because it looked like any old bit of trash blown in by the wind. I ran to it and set my flashlight down so it pointed up at the dark ceiling. Old webs hung from it like drapes and reflected the light in all directions, and then I didn’t feel so scared. I dumped the raven’s collection on the ground and got to work as fast as I could.

That’s when I heard it. It was like a laugh, but full of snot. And hunger.

My heart beated faster. Don’t be afraid, I told myself. Don’t be afraid.

But it was in there with me. It was close. I looked around. Everything beyond the reach of my little night light was dark. It was somewhere in those corners. How far back did they go? I couldn’t tell.

Then it spoke, like a thousand hissing spiders all talking on top of each other. But there was no sound. It was in my head.

Did you think because you nursed me as a youngling that I would spare you?

“You said you were starving! You said you didn’t want to hurt anybody! You said if I helped, you’d leave everybody alone! You said!” I grabbed the twine and the Frisbee ring. I laid the clips out in a row.

Young minds. So easily scared. So ripe with terror. Like sweet, bulging fruit.

I heard a sound like it was licking its lips.

I have tasted you. And I cannot stop. You saved your little friend. But I was just a worm then, barely more than the young I have begot.

I tried not to think about the squirming things inside the sac in the corner. How many of them were there? Hundreds? Thousands?

But you lied to me! it cursed.

“I did not!”

You tricked me. I needed to feed. But you don ’t have fear like the others. You kept me starving. Barely alive! Unable to grow.

“I had nightmares every night!”

A mass of rats exploded from the dark. I turned to look. I couldn’t help myself. They rose up into a two-legged mass. A shape like a mouth opened at the top and spiders spilled out. They rose up and white leeches spilled out. And so it leapfrogged itself, each form changing and disappearing, getting closer. Closer.

I turned back to my work and wrapped the twine faster.

Mosquitoes rose up in a buzzing swarm, so loud I could barely think, and then it was quiet and I saw my mom. I stopped what I was doing. It didn’t look fake. It looked like her. She was in her red work suit. I could smell her, like when she would hug me after school. Laundry detergent and perfume.

“Mom?”

She just stood there looking at me. But her eyes were so cold. Like she didn’t even recognize me. Not at first. And when she did, like she didn’t care. Like I was just someone in her way. Someone she used to know.

“Mommy . . . ?” The corners of my lips turned down. My mouth quivered as I sucked in breath. “Please don’t look at me like that. I won’t be bad anymore. I promise.”

But she just stood there, looking at me. With those eyes. Cold. Uncaring.

She stepped closer. Just looking.

My mom didn’t love me anymore. That’s all I could think. She stood over me and looked down with those eyes, like I should just get out of her way. She was important. She had important things to so. And she didn’t want me. Not anymore. She barely even remembered my name.

She leaned over and reached for my throat and all I could do was cry. I felt her fingers wrap around my neck, nail polish and all. I was losing something. I couldn’t tell what it was, but I knew I was going away somewhere. And I wouldn’t come back. And that would be it. I would be gone.

I couldn’t fight. Not anymore. I was tired. Everyone said I was bad all the time and I was tired of being bad. Maybe I should just sleep. Yes. I would sleep.

But I couldn’t because there was a noise. In the distance.

My mom lifted her head. That meant it wasn’t in my mind. It was real because she heard it, too.

There it was again.

It was my name. Someone was calling my name.

My dad.

My mom turned to face it. She looked worried. And then I knew. It wasn’t her. Not really. She wouldn’t be worried about my dad. It was just a fake. A nightmare. A terrible, awful nightmare. It wasn’t the truth!

My dad yelled my name again. Mr. Étranger must have called him and told him where I was going to be. The sound of his voice carried through the still, cold air of the hollow. He was out there looking for me, calling my name. But he was still so far away. He couldn’t find me.

I pushed my mom, but she was too strong. She snarled and gripped tighter.

But now I knew it was a lie. I remembered that my mom loved me. And as I thought that, I felt the fear-eater’s grip loosen.

So I thought it again. And again.

And again.

I gasped for breath. Then I pushed as hard as I could. I pushed up with my legs and my nightmare fell free. But I stumbled too and knocked over my flashlight. It turned and the leaves blocked the light. It was completely black. I heard the fear-eater hiss and slither and buzz and snarl around me in a circle, but I couldn’t see it. And I couldn’t see my dreamcatcher, the one I had almost finished. The white raven had given me three paper clips, and I had attached them to the ring of the Frisbee at the points of a triangle and used them as anchors as I wrapped the twine back and forth. The rubber spider dangled on one side and the shiny bottle cap on the other. It was almost ready. But now I couldn’t find it!

I began to feel through the leaf litter.

“Oh no . . .”

The fear-eater was swirling, gathering itself again, like a rattlesnake getting ready to strike. It rumbled and hissed and howled and snapped and clawed and stank. I couldn’t hear my dad anymore. I tried to call to him, but my voice was lost in a storm. I felt the earth shake. I saw the sky rip free. And I heard it speak, like the rumble of thunder.

Let me show you the future, boy.

And then it didn’t seem like I was in the hollow anymore. And what I saw made me cry. Babies, skin cracked open like dried earth, right down to the red, were shrieking in nurseries, one after the other. Thousands and thousands of them, all over the world. They had some new kind of disease. It was everywhere. Then I saw rows of coffins draped with flags, filling a runway for a mile as soldiers loaded them onto a row of transport planes, even as more and more were coming. The sky burned above. Deserts spread across the world. Oceans rose. People moved but they didn’t know where to go.

And that was the worst. The faces. So many people. Good people. Ready to give up. Working and working and never making anything better. Still sick. Still poor. Still powerless.

This is what awaits your world. Now that He has risen. In death and despair, there will be so much fear. More than we can drink. We will grow forever and walk like gods among you, feasting for all time!

And then I saw the giants, walking with wings and tentacles through the ruins of a city. Skyscrapers were cracked and frayed like corn husks. Others had fallen to the streets. There was no power. Everything was dark except the smoke in the air. It reflected red as if lit by a big fire far away.

I was supposed to be afraid.

But I wasn’t. Not even a little. Because I knew something no one else in the whole world knew. Not even Mr. Étranger. The stag had told it to me. I knew the word. And I knew that if the Others had given it to us, that meant it wasn’t too late.

I felt my dreamcatcher in the leaves. I raised it. I held the sea shell on the other side. I lifted them high and kicked the litter from my flashlight. The shiny, dangling bottle cap caught the freed beam and the fear-eater shrieked. It wanted to turn, but it had glanced.

And just like that, it was gone.

My waking dream disappeared and the earth over my head returned and the wriggling in the white spider sac stopped. It shriveled. Thousands of unhatched worms, like long, squirming maggots, fell to the ground. They dried up and turned into dead leaves.

Trevor fell, too. He was unconscious. I think.

I looked down at the shell. A little insect, like a stinkbug, was trying to wriggle out. I took the blue pebble out of my pocket and wedged it in the opening to trap the bogeyman. Then I put the shell in my coat and ran to make sure Trevor was breathing. When I saw his chest move, I ran to the stairs and yelled as loud as I could for my dad.

I’m posting the chapters of my forthcoming urban paranormal mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS. A blend of hard-boiled whodunit and contemporary urban fantasy, it’s scheduled to be released later this summer. You can sign up here to be notified.

You can start reading in order here: The old ones are patient.

The next chapter is: (not yet posted)

[image error]

June 6, 2018

The album nobody wanted

Automat is an album of instrumental electronic music composed by the Italian musicians Romano Musumarra and Claudio Gizzi. It was produced in 1977 and released in 1978 by EMI Italy, through its Harvest label. All the sounds in this album were generated by the MCS70, a monophonic analog synthesizer designed, built and programmed by the Italian engineer Mario Maggi.

Automat was Musumarra’s initiative – after learning about the new instrument, he proposed to EMI Italy that he produce an album of electronic instrumental music. Although at the time such a project was considered risky, the answer was positive. EMI suggested, however, that Claudio Gizzi, a more experienced composer that already worked with them, also participate in the project. The composition work was divided: Gizzi contributed to side A, who filled it with a long suite with 3 movements, and Musumarra contributed to side B, who composed three shorter pieces.

They had very little time to complete the project with only four weeks in the studio. As a result, the last track, Mecadence, was left somewhat incomplete, and the final album did not please either Musumarra and Gizzi nor the producers. They never collaborated on any other project nor had the opportunity to use the MCS70 again. Automat has only been released on CD once. Despite this (or perhaps because of it) the album achieved a “cult” status among many fans of electronic music. (Wikipedia)

Everything finds new life on the internet.

June 4, 2018

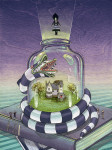

The vibrant pop-culture art of Nicole Gustafsson

It’s hard to be unhappy looking at the work of Nicole Gustafsson, AKA Nimasprout. Relentlessly bright and colorful, her art is both cosmic and hermetic. Whether it’s islands in space dripping rainbow rivers or pop culture franchises sealed under glass (Goonies, Beetlejuice, Stephen Universe, etc.), her spaces are unbounded and yet contained, just like fictional worlds she depicts.

Originally from Nebraska, Gustafsson now lives with her husband in the Pacific Northwest. Her work can be found at: www.nimasprout.com

June 3, 2018

The X-rated architecture of Jean-Jacques Lequeu (NSFW)

Later this year, the Petit Palais in Paris will host an exhibition on one of the most enigmatic and little-known figures in architecture, Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757-1825), whose fanciful, unorthodox, yet exactingly illustrated designs were just as grandiose as his contemporary (and better known) archrivals Etienne-Louis Boullee (1728-99) and Claude-Nicholas Ledoux (1736-1806). (Boullee’s cenotaph to Newton made an earlier appearance on this blog.)

But where the latter were true neoclassicists who captured the narcissistic, almost megalomaniacal grandeur of the Age of Reason, Lequeu was a maverick whose descent into madness is chronicled in the drawings he bequeathed to the French National Library some six months before he died, penniless and unknown.

But Lequeu didn’t restrict himself to blurprints, and after seeing his aptly-named “Figures Lascives” (lascivious images), it’s impossible not to interpret his architectural designs — arches and porticos, towers and grottos — as overtly sexual, a fact noted by the New York Times in a 1987 article entitled “These Buildings are X-Rated:”

After seeing those arresting anatomical renderings, superficially objective but deeply prurient in their depiction of female and male genitalia, it is impossible to look again at Lequeu’s architectural drawings without a new sense of their tumescent contours, scopophilic detailing and biomorphic transposition of classical motifs. The doors and windows of Lequeu’s villas, temples and gazebos seem more like inviting orifices than utilitarian openings; columns become insistently phallic, fountains joyously orgasmic…

They include a cow barn in the shape of an Assyrian bovine; an erotic garden folly called the ”Hammock of Love,” replete with a copulating couple; a priapic fountain in a Gothic tabernacle and two self-portraits in drag.

[image error]

[image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error]

June 1, 2018

The Maestro of Villarreal

Francisco de Asís Tárrega y Eixea (1852-1909), known simply as Francisco Tárrega, is considered the father of the classical guitar and one of the greatest guitarists in history.

Born in Villarreal, Spain to a watchman at the Convent of San Pascual, Francisco ran away from his father many times, despite that his father made great sacrifice to support his son’s music. Eventually, Tárrega entered the Madrid conservatory under the sponsorship of a wealthy merchant who heard the young man play.

Although the maestro spent most of his life in Spain, he did travel to London to play, where it’s said he composed arguably his most famous piece, Lágrima, in response to the dour weather and people, which he disliked to the point of melancholy.

Here is Vabejas playing your soundtrack to tonight.

And here is the full ongoing playlist, approaching 800 songs.

(Fiction) Salamongue Greymouth, Waspkeeper of Hell

When Mr. A. Tranjay and I got back, my dad was waiting for us. He was mad I had unlocked the door. And he had found the book, the one Mr. A. Tranjay gave me. He had found it under the mattress with my translation. I wrote it in pencil on the kind of lined paper we use in school.

Do you know the story of Salamongue Greymouth, Waspkeeper of Hell? No? I ’m not surprised. Salamongue was a minor angel who, in the great conflagration, spoke against patience and understanding, choosing instead to condemn his rebellious brethren with fire and damnation for daring to question the divine. Not openly of course. He spoke only in the quiet spaces, in his home and in the nooks of the cathedrals where he could bend the ears of his comrades and utter snarling, spittle-filled insults. He was seedy. And fractious. And pretended to be noble. And when the fighting was over, he was cast over the battlements with the insurrectionists, despite having only ever spoken against them.

Oh, Salamongue remembered well that day, when he and his fellows fell aflame through hazy orange clouds, like meteors, to crash upon a land of pus and acid, to stand again, despicable and deformed, on the shores of the Sea of Despair. But where Beelzebub and Azazel sat high and fat as princes of Pandaemon, Salamongue—now called Greymouth—was kicked and chided and given naught but the hellwasp farm of Blistermead, on the Venge, for it was a job no other would take.

Hellwasps, which Paul mistook for locusts in his famous revelation, sup on the suffering of sinners, which they collect with their bite. When they ’ve had their fill, they return to their nests, where they regurgitate it into blister-like sacs before concentrating the vomitus into a thick sap by beating their wings over it and sealing it with secretions from their anal glands. There it reaches potency after a fermentation of three seasons, at which time it’s collected by the Waspkeeper and given to the brewmasters, who turn it into a bitter relish that the Lords of Discord pour over their meals. It takes one drop to turn fresh meat foul, a single taste to waste a mortal man’s mind.

But the long years of tending Blistermead left their mark on Salamongue, who became even more despicable than after the fall. Hellwasps are vicious, needy things, and they nipped and stung him constantly. Stray drops of their acrid vomit burned his skin, which swelled into knots and turned callous. Over the centuries, he developed cankerous growths over his joints and fingers and large humps on his face and back that looked much like the nests of the wasps he tended. His afflictions made a perfect home for them, in fact, and they burrowed into his callouses and laid their young in the very pits of his flesh.

It is said that the major demons relished most of all the mead that was fermented from the back, fingers, and knees of Salamongue Greymouth, that it was a pustulous brew and tinged with blood, that the brewmasters sealed it in the ash-lined urns of the ancient dead where it aged like fine wine, and that after a century in the cellar it turned the color of charcoal and smelled of sulfurous urine and festering skin.

So it was, every three seasons, at the time of the harvesting, the Lords of Discord made a sport of the gathering. A great horn would sound and hellhounds would bay and Salamongue would run from Blistermead and across the Venge. He knew that if he could make it to the fells across the Styx, he could disappear into the maze of crypts, where the hounds could not follow, and the Lords of Discord would grow tired of the chase and return disappointed to the hollow halls of Pandaemon.

But if caught, Salamongue would be dragged by hook and chain down to the lowest circles of the Mad Keep and his cankers and mounds would be pierced with needles and he would be placed in a great vise and pressed like a grape, and he would scream, and what dribbled from his open sores would be collected in a fermenting vat tended by the Red Brewmaster himself, who watched each pressing with lips wet from smacking.

Such was the suffering of Salamongue Greymouth. Such was how he lived, with the buzzing and squirming of hundreds of tiny larvae buried in the humps and hills of his back, in his face, and in his fingers.

That was as far as I’d gotten. I didn’t know what all the words meant. Dad was mad I had hid it. I had been bad again. I was bad every day now, it seemed. I had ignored the doctor. I had run away. I wouldn’t listen. Good boys listen, he said. Why did I have to be bad? What had he done? He asked me politely to go to my room. He wanted to talk to Mr. A. Tranjay. He pretended like it wasn’t a big deal, but I could see it on his face.

I dragged my feet all the way upstairs. I stopped in the doorway to my room. I saw my toys on the floor. I had been ordered to pick them up. And do my homework. I hadn’t done either. I stared at the window. I couldn’t see the sun. It was cloudy and hazy. I stood there and stared and realized something about the symbols I had seen on the steam-covered glass. The window was clear, but in my mind I could still see them. No one had cleaned the glass, so that meant they were still there. Traced by a finger. Hidden. I was sure I wasn’t supposed to find them.

It had to be an adult who did it, I figured, because adults don’t get sent to their room and have to stare out at the world making deep sighs while their forehead is pressed to the glass so that their breath makes cool patterns on the pane, like clouds. I hadn’t been scared before. But I was now. If the steam could reveal them, I realized, that meant they were on the inside. And so whoever put them there had been in my room. I hadn’t been worried because I thought maybe they were protecting me. An adult made them and that’s what adults did, right? They protected kids. So that’s why they must be there. Even though I didn’t know why. But then I didn’t know why adults did lots of things.

But the symbols looked exactly like the ones in the book. Exactly. They weren’t traced backwards, like it showed in the instructions. That meant they weren’t there for my protection. They couldn’t be. They weren’t trying to keep something out. They were facing inside. They were keeping something in. In my room. Keeping it from escaping. Keeping it in there with me.

I looked at the dark space yawning under my bed. I looked at my closet door. Had I left it open?

I wavered at the entrance of my room until I heard my dad’s heavy footsteps on the stairs. Then I ran and jumped into bed so that whatever was underneath couldn’t reach up and get me. Dad walked in and sat down next to me. He was very sad. He said I was going to go someplace. Just for a while. He said that he’d talked to Mom and they agreed it was for the best. He said there were other kids there and good people who would take care of me. And he said he had just fired Mr. A. Tranjay, and that he wouldn’t be coming back there anymore. And that that was it, and he couldn’t talk to me about any of it now, and I was grounded and had to stay in my room until it was time to go. No exceptions. That he would bring me food and everything.

“Don’t make me lock you in here,” he said. “Please.”

I nodded.

Then he got up and left and I stayed in bed with the covers over me until Dad brought me dinner. I ate by myself on my bed, looking at my dark, open closet. I couldn’t play my gamepad. I couldn’t watch TV. I had to do homework until I just couldn’t do any more. I couldn’t take Wilson outside, so he just laid on the rug in my room and made sighs like he was just as bored as I was.

The doorbell rang and he ran downstairs barking. A man came, one of our neighbors, I think. I sat on my bed with my bedroom door open and I petted Betsy as I listened to them talk. I was sad because I was never going to see my friend Mr. A. Tranjay again. I liked him.

The man was handing out flyers. A kid was missing. A kindergartner, he said. A boy named Trevor.

My eyes got real big.

The man said Trevor had disappeared from his own back yard. His house was just down the street. It faced the hollow just like ours. His mom was ten yards away, bagging leaves. The man said it was like an eagle swooped down and took him. He said no one was safe. Our neighbors were organizing a search party. They were going to find the man who was terrorizing the community. The police said they had 24 hours. After that, it usually wasn’t good. The man wanted my dad to help. He said Trevor spoke with a lisp—whatever that is—and he was wearing a red Spider-Man T-shirt and blue jeans and sneakers. He said Trevor’s favorite food was strawberry ice cream and he wanted to be an ice cream man when he grew up because then he could eat ice cream all day long.

I sat on the edge of the bed. My feet dangled over the side and I didn’t care if there was something under there that was going to reach up and get me. Wilson and Betsy were on either side of me. I was supposed to be saying goodbye. My backpack was on the floor. It was all ready. My dad had packed it. Everything I needed. Except my pets. I needed them. And Mom and Dad. I needed them, too.

I was going to the doctor.

I looked at Wilson. Wilson looked at me back with his big brown eyes.

“They’re not gonna find him,” I said. “Trevor.”

Wilson said he knew.

“My secret will do terrible things. I stopped it before. But there’s no one to stop it now.”

Wilson said he knew that, too.

“What should I do?” I asked.

Wilson said I was a good boy and I should do what was in my heart, even if it made my dad angry.

I asked why I had to lose my parents. Why Mom left. Why Dad was sending me away.

He said he didn’t think there was a reason, just like there was no reason his people had hurt him so bad his fur didn’t grow back.

“I don’t know what to do,” I said.

Then Ribbon jumped onto the bed. I called him that because he had a long gray stripe on his side. He was an angry cat. His people had left him and I found him. He walked to the window. He went up on his hind legs and scratched on the glass over and over like he wanted to get out.

“Silly cat,” I said.

I reached for him. Then I saw there was something on the window sill. I unlocked the window. The sky was overcast. I couldn’t see the sun. It would be dark soon. The air was cold and still. I thought I heard something. But I couldn’t see behind me. Maybe my secret wasn’t under my bed or in my closet but on the roof.

There was a blueish pebble on the sill, about the size of a single peanut. I picked it up.

A scratch. Behind me. Now I knew there was definitely something on the house. I turned my head and looked up the sloped roof.

It was the white raven.

From my old neighborhood. It had found me.

It made a sound. Not a caw like a crow but a pleasant call. It was a big bird. Then it flapped its wings and flew to a nearby tree. The branches swayed when it landed. It called again. I looked at it and I could just tell. It wanted me to follow.

I looked back toward my bedroom door. I could see the stairs and the pictures on the wall. My dad was still talking with our neighbor on the front porch, right in front of the door. The back door was locked and Dad had the key.

I had to help Trevor. I was the only one who could. But I knew I couldn’t do it alone. It was too big for me. And there was only one person who knew about my secret. And about the stag and everything. There was only one person who believed me. Only one person in the whole world everywhere.

And the raven said she would take me to him.

I went to my closet and got an old pair of sneakers that didn’t fit me anymore. It hurt a little to put them on. I got the warm scratchy sweater from the bottom of my bottom drawer and the coat and gloves that my dad had packed in my backpack. He had lots of things in there. Good things to have for a trip, like snacks and my night light. He was a good packer. When I packed, I always forgot my toothbrush or my underwear or something.

I put on my backpack and climbed onto the roof. Pringles started barking at me, but I shushed her. I shuffled along the outside of my room to the place where Dad had been putting all the leaves that blew into the yard. I scooted on my butt to the edge and jumped. I was scared at first but it was real fun.

I left a note on my bed. It said:

I’M SORRY I HAVE TO BE BAD ONE LAST TIME

DON’T WORRY

LOVE, ÓLAFUR

I followed the white raven down Newcombe Street and under the big freeway but instead of turning left to go to the library, we turned right and walked past McDonald’s and a bunch of other places I had never been until we got to a little shopping center. The asphalt was old and had a bunch of holes and cigarette butts. There weren’t many cars. There were big piles of snow in the corners from when the plows came and it all sat there not melting. It was dark now.

The raven flew down a little street that ran along the far side of the shopping center and landed on a low sign that said: Midnight Gardens Mobile Home Community. There wasn’t any pavement. Just a dirt driveway with gravel and puddles. His name was written in marker on a white strip on the door of unit number five. It wasn’t Mr. A. Tranjay. It was spelled E-T-R-A-N-G-E-R. I felt stupid. Like a dumb kid who couldn’t even spell right. Like there was no way I could ever stop my secret from hurting anyone else and I should just give up and go home and go to the doctor and not try to be the good kind of bad anymore but just the regular kind like all the other kids.

I sniffed. It was cold and my nose was running. I reached in my pocket for tissues. Dad was a good packer. I wished he could have come with me. Someone had spray-painted red symbols on the ground all around. They were just like the ones on my window. The raven stood on a yellow plastic mailbox full of colorful junk mail. She called. She was a big bird. It was loud.

I was about to turn around and go home when the door opened.

And there he stood. He was worse than before. A lot worse. He was dressed in sweatpants. He had a cane. He couldn’t hold it still. He could barely stand. There was a knife in his other hand. It had a thick blade and looked like it was made of stone. It was red. He held it like he was expecting a fight.

I looked up at him. “It has a little boy named Trevor who likes ice cream and doesn’t say his S’s right. He’s in kindergarten.”

He looked at me. He looked at the raven on the mailbox.

She called again, softer.

“I didn’t think you were getting involved,” he said with his head lowered. He wasn’t talking to me.

But the raven just flapped her wings and flew away.

I’m posting the chapters of my forthcoming urban paranormal mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS. A blend of hard-boiled whodunit and contemporary urban fantasy, it’s scheduled to be released later this summer. You can sign up here to be notified.

You can start reading in order here: The old ones are patient.

The next chapter is: (not yet posted)

[image error]

May 31, 2018

Men Act, Women Appear (NSFW)

“The mirror was often used as a symbol of the vanity of woman. The moralizing, however, was mostly hypocritical.

You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, you put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting “Vanity”, thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for your own pleasure.”

“A woman must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself. Whilst she is walking across a room or whilst she is weeping at the death of her father, she can scarcely avoid envisaging herself walking or weeping. From earliest childhood she has been taught and persuaded to survey herself continually. And so she comes to consider the surveyor and the surveyed within her as the two constituent yet always distinct elements of her identity as a woman. She has to survey everything she is and everything she does because how she appears to men, is of crucial importance for what is normally thought of as the success of her life. Her own sense of being in herself is supplanted by a sense of being appreciated as herself by another….

One might simplify this by saying: men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object — and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.”

“The spectator-buyer is meant to envy herself as she will become if she buys the product. She is meant to imagine herself transformed by the product into an object of envy for others, an envy which will then justify her loving herself.”

“The happiness of being envied is glamour. Being envied is a solitary form of reassurance. It depends precisely upon not sharing your experience with those who envy you. You are observed with interest but you do not observe with interest – if you do, you will become less enviable. In this respect the envied are like bureaucrats; the more impersonal they are, the greater the illusion (for themselves and for others) of their power. The power of the glamorous resides in their supposed happiness: the power of the bureaucrat in his supposed authority.”

“Publicity has another social function. The fact that this function has not been planned as a purpose by those who make and use publicity in no way lessens its significance. Publicity turns consumption into a substitute for democracy.”

“Every exceptional work was the result of a prolonged successful struggle. Innumerable works involved no struggle. There were also prolonged yet unsuccessful struggles.”

“History always constitutes the relation between a present and its past. Consequently fear of the present leads to mystification of the past.”

“To remain innocent may also be to remain ignorant.”

Excerpts from John Berger’s landmark “Ways of Seeing,” both a book and a BBC program you can watch on YouTube.

Here is the second episode, on the female body. After presenting his argument, he turns the show over to a group of women and sits quietly and lets them speak, which was quite a thing to do in 1972.

cover image by Rikka Sormunen. art below by Rafal Olbinski and unknown

[image error]

[image error]