Rick Wayne's Blog, page 79

May 21, 2018

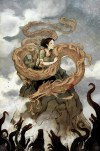

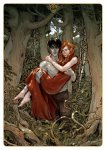

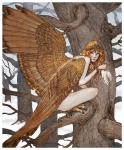

The secretive art of Erin Kelso

All I could find about the artist is what she has on her DeviantArt profile and a defunct Blogger. She apparently lives somewhere here in Kansas and has a couple kids and doesn’t seem to be working professionally, which would be too bad, if true, because this is amazing stuff, especially the tarot cards — Strength, Moon, and Star major arcana — and the illustration of Eowyn and the Nazgul.

EDIT: Thanks to folks to turning me on to her Tumblr. Erin Kelso Illustration

Click for a larger image.

(Fiction) What’s the trick?

The next day was dark and rainy. But it never came down very hard. Not enough to put you to sleep. Not enough to bring earthworms from the ground or flowers from the trees. Just enough to be sad. To keep everyone inside. I was grounded anyway, so it was fine with me.

Mom called. Dad had left her a message. About me. He told her about the hospital. Then they started talking about the lot. They were arguing about it. I never saw my dad get as mad as when he was talking to my mom. It scared me sometimes. I went up to my room.

Later that day, we had a visitor. I think Dad told me he was coming but I had forgot. Uncle Oliver wasn’t really my uncle. He was my dad’s cousin. But my parents said I should call him Uncle because they weren’t sure how that made us related. I said we were also cousins, but removed, because we had learned about that in a big genealogy project at school. But Dad said to call him Uncle anyway. He was a loud man.

He scowled at his plate. “Peanut butter and jelly sandwiches?”

Mr. A. Tranjay nodded.

Uncle Oliver and I sat at the kitchen table. Dad was in his office with the door closed. He was on the phone with his lawyer who was on the other line with Mom’s lawyer. Uncle Oliver seemed really confused. And maybe a little worried. He had come to see how things were working out with Mr. A. Tranjay. Plus he heard I had run away. I think he thought maybe they were related. He looked at me. I had already taken two bites. He looked back at the sandwich in his hand. He rubbed the long hairs on his head that he combed over the bare spot to make it look like he had more hair.

“What’s the trick?” he asked.

“There is no trick,” Mr. A. Tranjay said.

“What’s in it?”

“Peanuts.”

“And?”

Mr. A. Tranjay reached for the colorful plastic jar and started to read the ingredients. “Peanuts. Salt. Partially hydrogenated vegetable oil.” He set it down.

Uncle Oliver wasn’t convinced. “No bugs? Or larva?”

“No bugs.”

“No human excrement?”

Mr. A. Tranjay scowled. “I have never served excrement.”

I laughed with a mouthful.

“He does!” Uncle Oliver objected.

He sniffed the sandwich. It must have smelled fine because he took a bite. He chewed slowly. His lips smacked as he looked at me. I had eaten one half of my sandwich all the way down to the crust, and there was nothing else left but bite marks. I had purple jelly smeared on my cheeks, like a smiling clown. I don’t like clowns.

Uncle Oliver nodded reluctantly to the chef and turned to me. “So.” He stopped. He always got hung up on my name. He thought it was silly for Mom and Dad to name me that. “Ólafur. How are you enjoying your time with Mr. Étranger?”

I nodded. With Mr. A. Tranjay there it only seemed polite.

Uncle Oliver and I were named after the same man, but my great-aunt called him Oliver because she thought it was the same and she preferred to use “the American spelling” because they believed that’s what Great-Grandpa Ólafur would have wanted. It was really important to him that all his kids sound American and not like foreigners. That was a long time ago, I think. I asked my dad, if that’s what Great-Grandpa wanted, why didn’t he and Mom do the same thing, and he said because his aunt was wrong and Oliver and Ólafur weren’t really the same name at all, plus things weren’t like how they used to be and we should respect the old country. That’s where Great-Grandpa Ólafur was from. The old country. They have trolls and gnomes there. And it’s very cold, so everyone wears animal fur. Uncle Oliver said they discovered America first even though my history book said it was Columbus. I asked my teacher which was right and she said it was Uncle Oliver but that they expected us to say Columbus on the test so that’s what I should put at the end of the year. I asked her why they wanted to teach us the wrong thing and she asked me to go back to my seat.

Uncle Oliver swallowed the bite from his sandwich and took a drink. “What has he done? Is he cooking you all kinds of fun things?”

“I talked to a stag,” I explained. “It was dead though.”

“A stag?” Uncle Oliver looked impressed, and then he gave Mr. A. Tranjay a wink. “And what did the stag have to say?”

“I’m not supposed to tell.”

“How come?” Uncle Oliver pulled his sandwich apart and looked hard at the insides when Mr. A. Tranjay turned to the sink.

“Because it’s a secret.”

“Why is it a secret?”

I had to think for a moment. “That’s a secret, too.”

“Well, if you can’t tell anyone, and you can’t tell them why you can’t tell them, what’s the point of the stag telling it to you?”

“He said there would be a good time to say it, and I should hold on to it until then. But I should practice saying it in my head every day, just never out loud. If I say it out loud, then it loses . . .” I scowled. “Something. And I’ll need every last bit of it when the time comes.”

“Ohhh.” Uncle Oliver was confused. “I see.”

He used the voice adults use when they don’t really take you seriously. Like the time I told my dad about the willow tree growing in my closet. Hundreds of old metal keys dangled from the branches like fruit. Dad said willow trees don’t make fruit. It was there for a week. I was seven. I couldn’t get into my closet so I could only wear clothes out of my dresser, old clothes that didn’t fit me anymore. The other kids laughed. Then one day it was gone and I could get into my closet and wear my regular clothes again.

“So it’s important, this secret word.”

“Very.”

I chewed the last of my sandwich and set the second crust next to the first. Dad gave up trying to get me to eat them. Mom always made me.

“Well, are you going to see your friend the stag again?”

“He’s not really my friend. I don’t think. We haven’t played together or anything. He just tells me things. I think he’s waiting for something.”

“Waiting? For what?”

“I think somebody’s gonna die.”

Uncle Oliver pointed a big, round finger at Mr. A. Tranjay. “Don’t make me regret this.”

Mr. A. Tranjay raised both his hands. “It is not my doing.”

“People are looking for you, you know. I could very easily let them know about this arrangement, NDA or not.”

Mr. A. Tranjay nodded. “Has anyone approached you?”

“No. Why would they? We’re enemies. Or something like that. Everyone knows it. I’m starting to think that’s the whole reason you came to me for help. Because no one would ever suspect. And here I was touched.”

Mr. A. Tranjay scoffed. “We are not enemies.”

“Then what are we? Friends?”

“I have always respected you.”

“Oh, bullshit!” Uncle Oliver was loud.

Mr. A. Tranjay gave a little shrug. “But you are still a bureaucrat.”

“Can you believe this guy?” Uncle Oliver wanted me on his side. “I help him and he responds by insulting me.”

“You want me to sugarcoat the truth?” Mr. A. Tranjay motioned to the pans in the sink. “I can make a nice glacé very quickly.”

I didn’t know what that was.

“Rules are there for a reason,” my uncle objected.

“Yes, to prevent people from getting sick. But no one has gotten sick on my food.”

I fed my crusts to Wilson when no one was looking. Wilson liked the crusts.

“That’s not true.” Uncle Oliver turned back to me. If he noticed Wilson, he didn’t say. “His last dinner. The very last food circus. Last thing he did before he opened the Bistro. It’s all there online. It was the first thing I ever read about the man. Know what he did? Made his guests sick. Made them throw up. First one lost it right at the table and most of the others followed on sight. Some people tried to hang on but no one made it to the end. The final dish. It’s still a mystery.” He turned back to the chef. “What was it going to be? That Spanish cheese with the live maggots in it. What’s it called?”

“Casu marzu.”

“Yeah. Or maybe a cold soup made from cat piss. You do that kind of thing in Australia or Africa or wherever and maybe you’re the only one who gets in trouble. But that’s not how it works here.” Uncle Oliver turned to my dad as he walked into the room. “I can’t deal with him.”

“Ólafur, go upstairs.” My dad was scowling.

I could tell by his voice that it was serious adult stuff. I didn’t like being the kid, but I figured it would be boring anyway. I wanted to draw, but I was afraid my dad would get scared. He was always scared now. I could tell. He was always checking on me and doing things for me and looking at me when he thought I couldn’t see. I think he loves me but maybe he doesn’t like me very much. I didn’t want to be bad. I laid on the rug in my room with Wilson and Betsy and I tried to think of a plan. I was going to draw it out in marker. I had a blank sheet of paper and I put our house and Newcombe Street on it. Then I put the hollow and the big freeway. But that’s as far as I got.

I saw Ribbon in the corner under my bed. He was always hiding. He was a silly cat. I saw him hiding and it gave me an idea. Maybe I could trap it somehow. Like the guys on the Discovery Channel. So I went downstairs to watch TV and learn how to trap wild animals. But I fell asleep on the couch.

I woke up past dinner. Dad must have let me sleep. He said because I had been gone I didn’t have to go to school until next week, so I could sleep in and my teacher would bring my homework. I didn’t want to do it.

Uncle Oliver had left. I could tell because there was no yelling. Mr. A. Tranjay was sitting at the dining room table with his back to me, but I could see his face when he turned. He looked like he might throw up at any moment. He had a full glass of wine. I don’t think he drank any. He was facing my dad, who was half-hidden by the wall. There was an open bottle on the table next to him and a couple plates and dishes. Dad was telling Mr. A. Tranjay about Mom. It seems like that’s all he talked about, especially when he was drinking.

I was going to get up, but then Mr. A. Tranjay asked my dad about me, about what had happened, so I stayed still and listened.

“Oh, goodness.” My dad sat back. “There was an incident.”

I laid on the couch in the living room and pretended to be asleep.

“We moved out here—well, the plan had always been to renovate, to get out of the city. But I think Janet and I both would have preferred a little more time. To get ready. It’s hard for me to run my business from so far away, although the distance has been a blessing what with all of the excitement lately.”

“Of course.”

“Janet wasn’t ready at all. She preferred to let it all go, the whole thing, to send him back to school as if nothing had happened. I insisted on the change. I don’t think she ever really made peace with it. She hated it here. She started to resent everything. Most of all me, for pushing it.” My dad took a drink from his big wine glass. “But the truth is, things had been bad between us for a long time.”

“What kind of incident?”

I think Mr. A. Tranjay wanted to change the subject. Dad always made everything about him and Mom. I don’t think he ever stopped. I could tell it made people uncomfortable.

“A child was kidnapped. A little girl. It was horrible.” My dad shook his head. I could tell by the way his glass shook. “A nightmare. She was in a cage. Like an animal. She had these . . . marks on her body. They looked like bites and stings. She was covered in them, like a disease. The place stank of filth. And they never caught the guy. That was probably the scariest part.

“When the police arrived, they found Ólafur curled up on the floor outside the cage, sleeping. He was holding her hand through the bars. He had a single large welt on his chest. He’d been crying, it seems, and had worn himself out.” My dad sat up and raised a finger. “But there was nothing to indicate he was in any way involved.”

“Of course.”

“Sorry if I seem defensive. There were some suggestions at the time. There are plenty of stories, you know. About kids getting into witchcraft or whatever. Hurting each other.”

“Urban legends,” Mr. A. Tranjay said softly.

“Sure. But in a way, I can understand. A horrible tragedy like that, the circumstances . . . It was very unusual for him to go missing from class. He was such a good boy. Before. I can see where people might talk. If the roles were reversed, who knows what I would’ve thought?”

“Did he say what happened?”

“No. But he had an alibi.” My dad snorted. A little spit came out, and he covered his mouth. “Sorry. It’s just, you haven’t lived until you’ve had to provide proof of an alibi for your 7-year-old son. It was all so ridiculous, with the police and everything. Of course it didn’t help that Ólafur claimed . . .” My dad swirled his wine in the glass. “He claimed that there was some kind of ghost or something.” He shrugged.

“Oh, really?”

That seemed to interest Mr. A. Tranjay. I could tell because he lifted his head to look my dad in the eye for the first time.

“He said there was all kinds of vermin on her. That’s where the marks came from. Cockroaches. Mosquitoes. Rats.” Dad looked down at his twirling wine. “But . . . it’s over. And we shouldn’t dwell on something so horrible.” He finished his wine. “More?”

Mr. A. Tranjay put his hand over his glass politely.

My dad drained the bottle into his. It nearly filled it. “I have to say, it’s nice having someone out here. An adult, I mean. I love my son, but he’s not much for conversation.”

“How is he? Now?”

My dad took another drink. “He has nightmares. Or at least he did until just recently. But then, who wouldn’t after something like that? And we took him to the doctor, if that’s what you’re asking. Of course we did. Three months of therapy. Not that he ever seemed to need it, which worried us more than anything! Every night he’d wake up screaming, but every day he was fine. Sad, of course. About the girl. Every time it came up, with the police or whatever, he would just start to cry. He’d turn to the nearest person and hide his face. It broke everyone’s heart to see. But otherwise he seemed like his normal self.”

“Children can be very resilient.”

“Oh, sure. But it’s easy to imagine some trauma hidden just below the surface, something you could find and deal with if only you were a little more diligent. Do you have children?”

Mr. A. Tranjay nodded.

“Then you know being a parent is a lot like being a backseat driver. Every turn, every brake seems so much less certain when you’re not the one with your hands on the wheel. We kept taking him to the sessions. Two different doctors. We tried group settings. We tried individual. I would wait for him outside, half holding my breath, trying to hear what they were talking about. In the end, they never found anything.”

My dad shrugged and took another big gulp.

“The girl was another story. Catatonic, poor thing. Like the world had scared her so much, all she could do was hide from it. And her poor parents . . . I met them once at the hospital. They were aloof—suspicious of Ólafur’s involvement, I suppose—and in such shock. They were just kind of wandering around like they had no clue what to do. We rush through life so much of the time. Our minds are never in the present, except to check that our child did their homework or to answer email at the dinner table. We’re always looking ahead to the next day of work, to the weekend’s chores, to the grocery list, to soccer games and vacations that never arrive. In a moment, these people were pulled back into the present, and their whole future, all those plans, just disappeared. It was like they had no idea what to do, what to think, even.”

My dad made a curious face. “She wasn’t raped. Thankfully. But then, it was nothing anyone could explain either. At least not without considerable strain.” He grew half a smile. His eyelids drooped. He hesitated. “How much do you know about the occult?”

“I dabbled.”

“Oh?”

“As a younger man.”

“I see. Well, it’s something of a hobby with me.” He swirled his wine. “I’m something of a savant on the subject, actually.”

“Is that so?”

“Or, at least, I was. Before I got married. Janet never liked me to talk about it.” My dad’s face was very red from drinking. He scratched his beard. I knew what that meant. “Which I could understand. That’s not something one likes to admit in polite society. Her father is a congressman, after all.”

“Oh? Washington?”

“Harrisburg.”

“I see.”

“We always had to remember that the things we did affected him. We had to respect that.”

“Of course.” Mr. A. Tranjay drew his fingers over his lips. “You think they were supernatural? These marks?”

My dad settled back into his chair. “ ‘Supernatural’ is not a word we like to use.”

“Is that so? I didn’t know that.”

“Yes. It makes it all seem so hocusy-pocusy.”

“And it’s not like that?”

Dad shook his head. He took a breath to speak but Mr. A. Tranjay cut him off.

“Why did it spare your son?”

My dad stopped, confused. “What do you mean?”

“This occult force, why did it not harm your son?”

“I don’t know.” My dad drank again. His glass was nearly empty again. I could tell that his eyes weren’t very focused. And he was nervous. “I have these terrible thoughts. I can never bring myself to ask him. But I get why people were talking. I mean, how did Ólafur find her? Why was he holding her hand like that? And those awful marks on her skin. Like leeches or something.”

“Why wasn’t he scared?” Mr. A. Tranjay interrupted. He stood and walked behind his chair. I don’t think he was even listening to my dad anymore.

Dad put his hand over his mouth. He spoke through parted fingers. “Oh my God . . .” He looked at Mr. A. Tranjay with bloodshot eyes. “Oh my God, I never thought of that. Is that terrible? I was so scared. For the both of us. For everyone. I never even thought of that.” A moment passed. “You’re right. Oh my God. He was never scared.” He kept his hand over his bearded mouth. “Even when the police came. There was a girl in a cage. He was sad, but he never seemed scared.”

Then Mr. A. Tranjay turned his head and looked right at me, like he knew I was eavesdropping the whole time.

I’m posting the chapters of my forthcoming urban paranormal mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS. A blend of hard-boiled whodunit and contemporary urban fantasy, it’s scheduled to be released later this summer. You can sign up here to be notified.

You can start reading in order here: The old ones are patient.

The next chapter is: Time for dreaming

[image error]

What’s the trick?

The next day was dark and rainy. But it never came down very hard. Not enough to put you to sleep. Not enough to bring earthworms from the ground or flowers from the trees. Just enough to be sad. To keep everyone inside. I was grounded anyway, so it was fine with me.

Mom called. Dad had left her a message. About me. He told her about the hospital. Then they started talking about the lot. They were arguing about it. I never saw my dad get as mad as when he was talking to my mom. It scared me sometimes. I went up to my room.

Later that day, we had a visitor. I think Dad told me he was coming but I had forgot. Uncle Oliver wasn’t really my uncle. He was my dad’s cousin. But my parents said I should call him Uncle because they weren’t sure how that made us related. I said we were also cousins, but removed, because we had learned about that in a big genealogy project at school. But Dad said to call him Uncle anyway. He was a loud man.

He scowled at his plate. “Peanut butter and jelly sandwiches?”

Mr. A. Tranjay nodded.

Uncle Oliver and I sat at the kitchen table. Dad was in his office with the door closed. He was on the phone with his lawyer who was on the other line with Mom’s lawyer. Uncle Oliver seemed really confused. And maybe a little worried. He had come to see how things were working out with Mr. A. Tranjay. Plus he heard I had run away. I think he thought maybe they were related. He looked at me. I had already taken two bites. He looked back at the sandwich in his hand. He rubbed the long hairs on his head that he combed over the bare spot to make it look like he had more hair.

“What’s the trick?” he asked.

“There is no trick,” Mr. A. Tranjay said.

“What’s in it?”

“Peanuts.”

“And?”

Mr. A. Tranjay reached for the colorful plastic jar and started to read the ingredients. “Peanuts. Salt. Partially hydrogenated vegetable oil.” He set it down.

Uncle Oliver wasn’t convinced. “No bugs? Or larva?”

“No bugs.”

“No human excrement?”

Mr. A. Tranjay scowled. “I have never served excrement.”

I laughed with a mouthful.

“He does!” Uncle Oliver objected.

He sniffed the sandwich. It must have smelled fine because he took a bite. He chewed slowly. His lips smacked as he looked at me. I had eaten one half of my sandwich all the way down to the crust, and there was nothing else left but bite marks. I had purple jelly smeared on my cheeks, like a smiling clown. I don’t like clowns.

Uncle Oliver nodded reluctantly to the chef and turned to me. “So.” He stopped. He always got hung up on my name. He thought it was silly for Mom and Dad to name me that. “Ólafur. How are you enjoying your time with Mr. Étranger?”

I nodded. With Mr. A. Tranjay there it only seemed polite.

Uncle Oliver and I were named after the same man, but my great-aunt called him Oliver because she thought it was the same and she preferred to use “the American spelling” because they believed that’s what Great-Grandpa Ólafur would have wanted. It was really important to him that all his kids sound American and not like foreigners. That was a long time ago, I think. I asked my dad, if that’s what Great-Grandpa wanted, why didn’t he and Mom do the same thing, and he said because his aunt was wrong and Oliver and Ólafur weren’t really the same name at all, plus things weren’t like how they used to be and we should respect the old country. That’s where Great-Grandpa Ólafur was from. The old country. They have trolls and gnomes there. And it’s very cold, so everyone wears animal fur. Uncle Oliver said they discovered America first even though my history book said it was Columbus. I asked my teacher which was right and she said it was Uncle Oliver but that they expected us to say Columbus on the test so that’s what I should put at the end of the year. I asked her why they wanted to teach us the wrong thing and she asked me to go back to my seat.

Uncle Oliver swallowed the bite from his sandwich and took a drink. “What has he done? Is he cooking you all kinds of fun things?”

“I talked to a stag,” I explained. “It was dead though.”

“A stag?” Uncle Oliver looked impressed, and then he gave Mr. A. Tranjay a wink. “And what did the stag have to say?”

“I’m not supposed to tell.”

“How come?” Uncle Oliver pulled his sandwich apart and looked hard at the insides when Mr. A. Tranjay turned to the sink.

“Because it’s a secret.”

“Why is it a secret?”

I had to think for a moment. “That’s a secret, too.”

“Well, if you can’t tell anyone, and you can’t tell them why you can’t tell them, what’s the point of the stag telling it to you?”

“He said there would be a good time to say it, and I should hold on to it until then. But I should practice saying it in my head every day, just never out loud. If I say it out loud, then it loses . . .” I scowled. “Something. And I’ll need every last bit of it when the time comes.”

“Ohhh.” Uncle Oliver was confused. “I see.”

He used the voice adults use when they don’t really take you seriously. Like the time I told my dad about the willow tree growing in my closet. Hundreds of old metal keys dangled from the branches like fruit. Dad said willow trees don’t make fruit. It was there for a week. I was seven. I couldn’t get into my closet so I could only wear clothes out of my dresser, old clothes that didn’t fit me anymore. The other kids laughed. Then one day it was gone and I could get into my closet and wear my regular clothes again.

“So it’s important, this secret word.”

“Very.”

I chewed the last of my sandwich and set the second crust next to the first. Dad gave up trying to get me to eat them. Mom always made me.

“Well, are you going to see your friend the stag again?”

“He’s not really my friend. I don’t think. We haven’t played together or anything. He just tells me things. I think he’s waiting for something.”

“Waiting? For what?”

“I think somebody’s gonna die.”

Uncle Oliver pointed a big, round finger at Mr. A. Tranjay. “Don’t make me regret this.”

Mr. A. Tranjay raised both his hands. “It is not my doing.”

“People are looking for you, you know. I could very easily let them know about this arrangement, NDA or not.”

Mr. A. Tranjay nodded. “Has anyone approached you?”

“No. Why would they? We’re enemies. Or something like that. Everyone knows it. I’m starting to think that’s the whole reason you came to me for help. Because no one would ever suspect. And here I was touched.”

Mr. A. Tranjay scoffed. “We are not enemies.”

“Then what are we? Friends?”

“I have always respected you.”

“Oh, bullshit!” Uncle Oliver was loud.

Mr. A. Tranjay gave a little shrug. “But you are still a bureaucrat.”

“Can you believe this guy?” Uncle Oliver wanted me on his side. “I help him and he responds by insulting me.”

“You want me to sugarcoat the truth?” Mr. A. Tranjay motioned to the pans in the sink. “I can make a nice glacé very quickly.”

I didn’t know what that was.

“Rules are there for a reason,” my uncle objected.

“Yes, to prevent people from getting sick. But no one has gotten sick on my food.”

I fed my crusts to Wilson when no one was looking. Wilson liked the crusts.

“That’s not true.” Uncle Oliver turned back to me. If he noticed Wilson, he didn’t say. “His last dinner. The very last food circus. Last thing he did before he opened the Bistro. It’s all there online. It was the first thing I ever read about the man. Know what he did? Made his guests sick. Made them throw up. First one lost it right at the table and most of the others followed on sight. Some people tried to hang on but no one made it to the end. The final dish. It’s still a mystery.” He turned back to the chef. “What was it going to be? That Spanish cheese with the live maggots in it. What’s it called?”

“Casu marzu.”

“Yeah. Or maybe a cold soup made from cat piss. You do that kind of thing in Australia or Africa or wherever and maybe you’re the only one who gets in trouble. But that’s not how it works here.” Uncle Oliver turned to my dad as he walked into the room. “I can’t deal with him.”

“Ólafur, go upstairs.” My dad was scowling.

I could tell by his voice that it was serious adult stuff. I didn’t like being the kid, but I figured it would be boring anyway. I wanted to draw, but I was afraid my dad would get scared. He was always scared now. I could tell. He was always checking on me and doing things for me and looking at me when he thought I couldn’t see. I think he loves me but maybe he doesn’t like me very much. I didn’t want to be bad. I laid on the rug in my room with Wilson and Betsy and I tried to think of a plan. I was going to draw it out in marker. I had a blank sheet of paper and I put our house and Newcombe Street on it. Then I put the hollow and the big freeway. But that’s as far as I got.

I saw Ribbon in the corner under my bed. He was always hiding. He was a silly cat. I saw him hiding and it gave me an idea. Maybe I could trap it somehow. Like the guys on the Discovery Channel. So I went downstairs to watch TV and learn how to trap wild animals. But I fell asleep on the couch.

I woke up past dinner. Dad must have let me sleep. He said because I had been gone I didn’t have to go to school until next week, so I could sleep in and my teacher would bring my homework. I didn’t want to do it.

Uncle Oliver had left. I could tell because there was no yelling. Mr. A. Tranjay was sitting at the dining room table with his back to me, but I could see his face when he turned. He looked like he might throw up at any moment. He had a full glass of wine. I don’t think he drank any. He was facing my dad, who was half-hidden by the wall. There was an open bottle on the table next to him and a couple plates and dishes. Dad was telling Mr. A. Tranjay about Mom. It seems like that’s all he talked about, especially when he was drinking.

I was going to get up, but then Mr. A. Tranjay asked my dad about me, about what had happened, so I stayed still and listened.

“Oh, goodness.” My dad sat back. “There was an incident.”

I laid on the couch in the living room and pretended to be asleep.

“We moved out here—well, the plan had always been to renovate, to get out of the city. But I think Janet and I both would have preferred a little more time. To get ready. It’s hard for me to run my business from so far away, although the distance has been a blessing what with all of the excitement lately.”

“Of course.”

“Janet wasn’t ready at all. She preferred to let it all go, the whole thing, to send him back to school as if nothing had happened. I insisted on the change. I don’t think she ever really made peace with it. She hated it here. She started to resent everything. Most of all me, for pushing it.” My dad took a drink from his big wine glass. “But the truth is, things had been bad between us for a long time.”

“What kind of incident?”

I think Mr. A. Tranjay wanted to change the subject. Dad always made everything about him and Mom. I don’t think he ever stopped. I could tell it made people uncomfortable.

“A child was kidnapped. A little girl. It was horrible.” My dad shook his head. I could tell by the way his glass shook. “A nightmare. She was in a cage. Like an animal. She had these . . . marks on her body. They looked like bites and stings. She was covered in them, like a disease. The place stank of filth. And they never caught the guy. That was probably the scariest part.

“When the police arrived, they found Ólafur curled up on the floor outside the cage, sleeping. He was holding her hand through the bars. He had a single large welt on his chest. He’d been crying, it seems, and had worn himself out.” My dad sat up and raised a finger. “But there was nothing to indicate he was in any way involved.”

“Of course.”

“Sorry if I seem defensive. There were some suggestions at the time. There are plenty of stories, you know. About kids getting into witchcraft or whatever. Hurting each other.”

“Urban legends,” Mr. A. Tranjay said softly.

“Sure. But in a way, I can understand. A horrible tragedy like that, the circumstances . . . It was very unusual for him to go missing from class. He was such a good boy. Before. I can see where people might talk. If the roles were reversed, who knows what I would’ve thought?”

“Did he say what happened?”

“No. But he had an alibi.” My dad snorted. A little spit came out, and he covered his mouth. “Sorry. It’s just, you haven’t lived until you’ve had to provide proof of an alibi for your 7-year-old son. It was all so ridiculous, with the police and everything. Of course it didn’t help that Ólafur claimed . . .” My dad swirled his wine in the glass. “He claimed that there was some kind of ghost or something.” He shrugged.

“Oh, really?”

That seemed to interest Mr. A. Tranjay. I could tell because he lifted his head to look my dad in the eye for the first time.

“He said there was all kinds of vermin on her. That’s where the marks came from. Cockroaches. Mosquitoes. Rats.” Dad looked down at his twirling wine. “But . . . it’s over. And we shouldn’t dwell on something so horrible.” He finished his wine. “More?”

Mr. A. Tranjay put his hand over his glass politely.

My dad drained the bottle into his. It nearly filled it. “I have to say, it’s nice having someone out here. An adult, I mean. I love my son, but he’s not much for conversation.”

“How is he? Now?”

My dad took another drink. “He has nightmares. Or at least he did until just recently. But then, who wouldn’t after something like that? And we took him to the doctor, if that’s what you’re asking. Of course we did. Three months of therapy. Not that he ever seemed to need it, which worried us more than anything! Every night he’d wake up screaming, but every day he was fine. Sad, of course. About the girl. Every time it came up, with the police or whatever, he would just start to cry. He’d turn to the nearest person and hide his face. It broke everyone’s heart to see. But otherwise he seemed like his normal self.”

“Children can be very resilient.”

“Oh, sure. But it’s easy to imagine some trauma hidden just below the surface, something you could find and deal with if only you were a little more diligent. Do you have children?”

Mr. A. Tranjay nodded.

“Then you know being a parent is a lot like being a backseat driver. Every turn, every brake seems so much less certain when you’re not the one with your hands on the wheel. We kept taking him to the sessions. Two different doctors. We tried group settings. We tried individual. I would wait for him outside, half holding my breath, trying to hear what they were talking about. In the end, they never found anything.”

My dad shrugged and took another big gulp.

“The girl was another story. Catatonic, poor thing. Like the world had scared her so much, all she could do was hide from it. And her poor parents . . . I met them once at the hospital. They were aloof—suspicious of Ólafur’s involvement, I suppose—and in such shock. They were just kind of wandering around like they had no clue what to do. We rush through life so much of the time. Our minds are never in the present, except to check that our child did their homework or to answer email at the dinner table. We’re always looking ahead to the next day of work, to the weekend’s chores, to the grocery list, to soccer games and vacations that never arrive. In a moment, these people were pulled back into the present, and their whole future, all those plans, just disappeared. It was like they had no idea what to do, what to think, even.”

My dad made a curious face. “She wasn’t raped. Thankfully. But then, it was nothing anyone could explain either. At least not without considerable strain.” He grew half a smile. His eyelids drooped. He hesitated. “How much do you know about the occult?”

“I dabbled.”

“Oh?”

“As a younger man.”

“I see. Well, it’s something of a hobby with me.” He swirled his wine. “I’m something of a savant on the subject, actually.”

“Is that so?”

“Or, at least, I was. Before I got married. Janet never liked me to talk about it.” My dad’s face was very red from drinking. He scratched his beard. I knew what that meant. “Which I could understand. That’s not something one likes to admit in polite society. Her father is a congressman, after all.”

“Oh? Washington?”

“Harrisburg.”

“I see.”

“We always had to remember that the things we did affected him. We had to respect that.”

“Of course.” Mr. A. Tranjay drew his fingers over his lips. “You think they were supernatural? These marks?”

My dad settled back into his chair. “ ‘Supernatural’ is not a word we like to use.”

“Is that so? I didn’t know that.”

“Yes. It makes it all seem so hocusy-pocusy.”

“And it’s not like that?”

Dad shook his head. He took a breath to speak but Mr. A. Tranjay cut him off.

“Why did it spare your son?”

My dad stopped, confused. “What do you mean?”

“This occult force, why did it not harm your son?”

“I don’t know.” My dad drank again. His glass was nearly empty again. I could tell that his eyes weren’t very focused. And he was nervous. “I have these terrible thoughts. I can never bring myself to ask him. But I get why people were talking. I mean, how did Ólafur find her? Why was he holding her hand like that? And those awful marks on her skin. Like leeches or something.”

“Why wasn’t he scared?” Mr. A. Tranjay interrupted. He stood and walked behind his chair. I don’t think he was even listening to my dad anymore.

Dad put his hand over his mouth. He spoke through parted fingers. “Oh my God . . .” He looked at Mr. A. Tranjay with bloodshot eyes. “Oh my God, I never thought of that. Is that terrible? I was so scared. For the both of us. For everyone. I never even thought of that.” A moment passed. “You’re right. Oh my God. He was never scared.” He kept his hand over his bearded mouth. “Even when the police came. There was a girl in a cage. He was sad, but he never seemed scared.”

Then Mr. A. Tranjay turned his head and looked right at me, like he knew I was eavesdropping the whole time.

I’m posting the chapters of my forthcoming urban paranormal mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS. A blend of hard-boiled whodunit and contemporary urban fantasy, it’s scheduled to be released later this summer. You can sign up here to be notified.

You can start reading in order here: The old ones are patient.

The next chapter is: (not yet posted)

[image error]

May 20, 2018

Ten Depictions of the Cosmos

Depictions of the universe, variously defined. List of figures:

Cosmological Mandala with Mount Meru. China. Yuan Dynasty (circa 1300)

l’Image du Monde by Gautier du Metz (1245)

Geheime Figuren der Rosenkreuzer (1785)

Sphaera Coelestis Mystica (1739) plate 7 by Johann Georg Hagelgans

Lokapurusha (Cosmic Man), Rajasthan (circa 19th cent.)

Sheppard’s Geographical and Astronomical Clock (circa 1840)

Figure from History, Observations and Interpretations of the Big Bang Theory (20th cent.)

Classical depiction of Yggdrasil and the Norse firmament

Cosmolux by Paul Laffoley (1981)

Pollen Boy on the Sun. Navajo sand painting

[image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error]

[image error]Working Title/Artist: Cosmological Mandala with Mount MeruDepartment: Asian ArtCulture/Period/Location: HB/TOA Date Code: Working Date: 1271-1368 photography by mma, Digital File retouched by film and media (kah) 04_01_14

[image error] [image error] [image error] [image error]

May 19, 2018

Chernobyl: Stefan Koidl’s Visual Horror Story

Inspired by the artist’s visit to the famed disaster site. You can see the full set here and here.

The highlights:

[image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error]

(Fiction) What were you feeding it?

I woke to flute music. The soft notes fell over me, light and gentle, like how tears fall, or autumn leaves after a stiff breeze. The stag was gone. The sun was shining. I was covered in brown leaves. I had my jacket on and my hat and my hood up, but something had covered me in the night, made me a den like the animals use to keep warm. I was completely hidden. If someone had passed, they wouldn’t have seen. I laid in my warm cocoon and listened to the flute. I felt like I should have been colder. There was still a little snow in the nooks behind the trees. But the sun was so nice. It was getting higher in the sky these days. The tall trees were reaching for it. It seemed as if I could step up them and walk the earth.

I stood to stretch and that’s when I noticed the buds. They hadn’t been there the night before. Little green sprouts just poking from the tips of the branches. They swayed back and forth in the wind. The limbs of the trees knocked into each other and made a sound like wood blocks to accompany the notes of the flute. Like a symphony. Dad took me to a symphony once and I fell asleep there, too.

I turned toward the music and noticed a ring of mushrooms had sprouted around me in the night. Mushrooms do that. My dogs poop all over the yard and then some days I wake up and look out my window and see the white caps in the grass where they weren’t there before. In school we learned that mushrooms recycle dead stuff and make it like it’s new. Teacher said there’s even some that glow in the dark, but these were just the regular kind like we have in our yard. I stepped outside the ring and followed the sound of the flute.

Mr. A. Tranjay was in a clearing. He was sitting Indian-style on a turquoise blanket. He was just sitting in a wide depression in the hollow. By himself. Playing the flute. I think it was the same one he’d been carving.

When he was done, a breeze blew again and the tree branches knocked into each other more. Almost like applause.

I walked over to him. He didn’t seem surprised to see me.

“Where have you been hiding?”

I shrugged.

“Everyone is out looking for you.”

I nodded. I shivered. It seemed much colder then. Away from my den.

“Your father is very worried.” He moved to the side and pulled the blanket from underneath him and handed it to me.

It was warm. I think that’s why he’d been sitting on it. And it smelled like campfire and spices. I wrapped it around myself and sat down next to him.

“But where they are looking, they will not find you.”

I thought that was funny since the hollow wasn’t that big. Not for adults. Although, I didn’t recognize where we were. I thought I knew everywhere in the hollow, but this place was new.

“Are you ready to go back?” he asked.

I thought for a moment. My dad would yell. I shook my head.

Mr. A. Tranjay nodded. He lifted the flute to his lips and started to play again. It was a different song this time. It sounded like tears falling into a gurgling stream. The notes warbled and spun and then stopped. Mr. A. Tranjay started coughing. He took out a handkerchief and wiped his mouth.

“That’s nice,” I said.

“Thank you.”

“What does it mean?”

He looked at me curiously. “What makes you think it means anything?”

I shrugged.

He extended the flute to me. It was covered in intricate carvings. And it was a strange color, like a brownish-white ash. A small gold tassel dangled from the top.

I looked at it.

“Go on.”

I took it and raised the end to my lips. “Is it okay?”

“Please.” He motioned to the air with a tattooed palm.

His hands were shaking. More than before. I think there were more symbols missing now. Like they were disappearing from his skin. Or he was sending them away. He was so skinny. Not just his body but his face, too. Like Wilson when I found him. I think he had stopped eating.

I pressed my lips gently to the flute. The wood felt soft. It wasn’t at all like the plastic tubes I had to play in music class. I didn’t have to push to make sounds. All I had to do was breathe and move my fingers up and down the holes. I didn’t really know what I was doing. But it was fun.

I stopped when I heard drops hit the leaves with a pit-pit-patter. I looked up at clouds rolling overhead. Just before it had been sunny.

“Don’t worry,” Mr. A. Tranjay said. “It will pass.”

“How do you know?”

“Because you didn’t finish the song.”

I looked up at the sky, at the island clouds moving by, and then back to the strange chef. “I did that?”

“Why are you sad?”

I was surprised by the question. “I’m not sad.”

“You played a very sad song.”

“So did you.”

The chef made a face like he’d been caught in a lie. “So it would seem.”

“Did someone die? Is that why you came here?”

“You are a very inquisitive boy.” He held out his hand.

I gave the flute back. He pressed it softly to his lips and moved it back and forth a little, like feet settling into a warm bed. Then he finished the song from before. When it was done, he looked at the flute before resting it in his lap.

“I suppose I am sad,” he said. He turned to me. “If I tell you why I am sad, will you tell me why you are sad?”

I looked up and thought. “I can’t,” I said.

“Why not?”

“I promised I wouldn’t say.”

He nodded and slipped the flute into a carved leather slip-pouch. “You know, if you don’t tell me where it’s hiding, I can’t help you.”

I looked down. I knew he meant my secret.

“But then,” he added. “I’m not sure I could be much help anymore.”

I wanted to pretend like I didn’t know what he was talking about, like adults do. Everybody knows they’re lying, but they do it just good enough. I thought maybe I should practice.

“What do you mean?”

“What were you feeding it? Your nightmares?”

I didn’t know what to say. I think we were quiet for a long time. “I dunno.”

“It is very dangerous.” He looked at me.

I pushed the leaves on the ground with my shoe.

“But then I think you know that.”

I shrugged.

“Come. Your father is worried.” He stood very slowly. His legs wobbled once. I had to help him.

“Are you sick?”

I held on to his hand while we walked. I don’t know if that was because he wanted to or I wanted to. Maybe we both did.

He said he wasn’t sick.

“Then how come you’re not getting better?”

He was silent for a few steps. The leaves crunched softly under our feet. I saw fireflies. They popped in and out and seemed to be following us.

Mr. A. Tranjay asked me if I had ever lost a balloon, and I said yes, I had. Last year my mom had taken me to the big fair they have in the fall and I had a balloon that looked like a poodle and I had lost it. I didn’t tell him the real reason. I had given my balloon to a girl who wanted it very bad. But she didn’t say. I could just tell. And it didn’t look like her parents had enough money to get her one. I think they were from a different country. So I gave her mine while my mom was getting us funnel cakes. Mom wasn’t very happy with me. She said it was irresponsible to lose it and I was old enough to know better and I had to eat my funnel cake and then we would go. I miss my mom.

Mr. A. Tranjay said a soul was like a balloon. Most of the time—which was all of the time for people like me—it was a bad idea to cut it open. But, he said, there were some people who had special knowledge, and they knew it wasn’t the cutting so much as the when and the where. That’s what he said. The when and the where. I liked that.

Then he asked me what would happen if you cut a balloon before it was full.

I said when the man at the carnival had made a mistake with one of the balloons and it had made an awful noise and flapped around and fell to the ground flat. I thought it was a waste. It had been very pretty, like a big, colorful flower.

He said yes, it would be a terrible waste. Then he asked what would happen if you cut a balloon while it was full. I said it would pop and kicked a rock on the path. I don’t remember there being a path in the hollow. We had been walking for a while. Longer than we should have if we were just going across. It seemed like maybe we had been somewhere else. Maybe the stag had taken me somewhere. To be safe. Maybe that was why no one found me. Except Mr. A. Tranjay.

Then he asked what would happen if, instead of cutting the balloon, you just cut the string.

I said I’d be sad because the balloon would fly away.

“But you weren’t sad before you had the balloon. So the happiness or sadness is not in the balloon, is it?”

“I guess not,” I said.

We passed a cluster of fireflies, which seemed like they stopped at the border of two big old trees. I didn’t remember there being trees that big in the hollow. We walked between them and left the fireflies behind.

Mr. A. Tranjay said we’re all like the flat balloons at the carnival: bright and colorful but empty until someone fills them up and ties them with a string. He said that we spend our lives tying more and more things onto the end so that eventually the balloon is so heavy it can’t get off the ground, and some pop. He said he’d been very busy lately cutting all his strings, although some had been cut for him, and he wasn’t very pleased about that. But he said he’d done such a good job that there was only one left—that very first string—and when that was cut, he would float off into the air, only I don’t think he meant actual air. I think he meant something else.

That’s when I heard my dad.

“Ólafur!”

He came running around the fence that ran along the hollow near Newcombe Street. He was in his long, dark coat, like what he wore to Grandpa’s funeral, and a red scarf. He had a cup of coffee in his hand and he threw it down to hug me.

I smiled. It was a good hug.

“Here he is,” Mr. A. Tranjay said. “None the worse for wear.”

“Thank God. Are you okay? Where have you been? We were so worried.”

There were some other people around. Adults mostly. I recognized a couple of them. I think they were our neighbors. One of them was Trevor’s dad. They were out looking for me. They smiled and shook my dad’s hand as we walked home. It seemed like maybe it was a big deal. My dad held on to me the whole way. It was a strong grip. I could tell he was mad. He was happy I was back, but he was mad, too.

Pringles was waiting at home. She had come back before me. And after I said hi to her and Wilson and Betsy and Speedy, Dad and I sat at the kitchen table and he made soup and told me there was a bad man on the loose, and that everyone thought he had taken me. My dad looked really tired. He looked like he’d run all the way to our old house and back. He said that just down the street someone had attacked a little girl, and that a few days before I went missing, some kids a couple streets over said something was chasing them.

“Was it like a bunch of spiders all together in a big bunch?”

My dad looked at me funny. Then he told me I couldn’t go into the hollow by myself for a while. Or anywhere. Even the library. Until they caught the bad man. He asked me if I understood, and I said yes. Then he said he was going to start locking the doors with a key.

“But how will I let Wilson and Pringles out to pee?”

“That will be my job. You just feed them in the evenings, and I’ll do the rest.”

I didn’t think that was fair. They were my pets. Dad was just doing it because he was worried. But he was worried about the wrong thing. Then he said something funny.

“You don’t have to go to school tomorrow.”

But it was the weekend. Tomorrow was supposed to be Sunday, but Dad said tomorrow was Tuesday and I could stay home for as long as I wanted and play video games. I didn’t think that was right. That it went from Saturday right to Tuesday.

When it was bedtime, Sudoku came and laid on my covers. She was an old dog and mostly slept downstairs. But I had been missing so she came to check on me. I petted her. She’s brown and white. I was in my red Phillies pajamas.

“Dad?”

“Yes?” He stopped in the doorway on his way downstairs. He told me I had to leave it open now. All the time. He hugged me a lot.

“If I tell you something, will you promise not to be mad?”

“That depends.”

I waited for a moment. Once I told him, there would be no going back.

“There was something in the garage. Before. I don’t know what it is, but it was hurting Emerald. I had it there and it got out. I’ve been looking for it. It came here, and I chased it into the hollow. Then I got scared and fell asleep.” I didn’t want to mention the stag again.

I saw my dad’s face. He looked so hurt. And disappointed. And angry. Like he was trying to keep from yelling at me. But mostly he looked hurt and sad, like he didn’t know what else to do. With me. Like maybe I wasn’t a good boy anymore. Maybe I was a bad kid.

Maybe I wasn’t a very good son.

“I know you said I couldn’t bring any more strays home, and that Betsy and Ribbon and Pringles and Wilson and Sudoku were enough, but this wasn’t a stray. It’s something else. I didn’t want it to hurt any—”

“Ólafur.”

I stopped.

His voice. I could tell. I could hear it. The way he said my name. I felt tears. He was so disappointed in me. My dad. He was so hurt and disappointed. Because of me. Because of everything I’d done. I was bad. My eyes got blurry.

“Let’s just talk in the morning, son. Okay?”

My lip was shaking. I swallowed. I nodded. My dad was so disappointed with me. “I’m sorry,” I said quietly.

“It’s okay, son. Let’s just talk in the morning. Get some sleep.”

I nodded. He didn’t wait for me to lay down and pull the covers over me like he usually did. He just walked away. He turned the hall light off and closed his bedroom door. He never did that. Not since I started having the nightmares.

I got up and tiptoed down the hall. I leaned close to the door. I thought maybe he was crying. I’d heard him once, after he found out about Mom. He cried a long time. I did, too.

But he wasn’t crying. He was talking on the phone. He was talking to a doctor. I could tell. Because of the words he was using. Big words. He was talking about taking me somewhere. To a hospital, maybe. He said the nightmares had stopped suddenly, but now I was seeing things and drawing horrible pictures of giant insects devouring children. And I had run away for two days and told him I was chasing ghosts. He said it seemed like my condition was getting worse, and he didn’t know what else to do. He was starting to feel like he couldn’t keep me safe and that was a terrible feeling and he just wanted some help.

“For how long?” he asked.

“Yes,” he said. “Yes, maybe that would be best.”

I didn’t want to go away from my dad. I didn’t want to be in a strange hospital with people I didn’t know. I didn’t want to get taken away again. I wanted to find my secret and stop it before it hurt anyone else. I wanted my mom to come back and for everything to be like it was. Before “the incident.”

My dad said goodbye to whoever was on the phone and I crept back to my room.

I couldn’t go to a hospital. I had seen what my secret did to Emerald. And the girl in the pink dress. It came back to the house because it was hungry. But it couldn’t get in. It couldn’t get to me. Something had stopped it. So it would find another kid. Maybe soon. Then it would find another. And another.

I had to stop it.

But I didn’t know how.

I’m posting the chapters of my forthcoming urban paranormal mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS. A blend of hard-boiled whodunit and contemporary urban fantasy, it’s scheduled to be released later this summer. You can sign up here to be notified.

You can start reading in order here: The old ones are patient.

The next chapter is: What’s the trick?

[image error]

What were you feeding it? Your nightmares?

I woke to flute music. The soft notes fell over me, light and gentle, like how tears fall, or autumn leaves after a stiff breeze. The stag was gone. The sun was shining. I was covered in brown leaves. I had my jacket on and my hat and my hood up, but something had covered me in the night, made me a den like the animals use to keep warm. I was completely hidden. If someone had passed, they wouldn’t have seen. I laid in my warm cocoon and listened to the flute. I felt like I should have been colder. There was still a little snow in the nooks behind the trees. But the sun was so nice. It was getting higher in the sky these days. The tall trees were reaching for it. It seemed as if I could step up them and walk the earth.

I stood to stretch and that’s when I noticed the buds. They hadn’t been there the night before. Little green sprouts just poking from the tips of the branches. They swayed back and forth in the wind. The limbs of the trees knocked into each other and made a sound like wood blocks to accompany the notes of the flute. Like a symphony. Dad took me to a symphony once and I fell asleep there, too.

I turned toward the music and noticed a ring of mushrooms had sprouted around me in the night. Mushrooms do that. My dogs poop all over the yard and then some days I wake up and look out my window and see the white caps in the grass where they weren’t there before. In school we learned that mushrooms recycle dead stuff and make it like it’s new. Teacher said there’s even some that glow in the dark, but these were just the regular kind like we have in our yard. I stepped outside the ring and followed the sound of the flute.

Mr. A. Tranjay was in a clearing. He was sitting Indian-style on a turquoise blanket. He was just sitting in a wide depression in the hollow. By himself. Playing the flute. I think it was the same one he’d been carving.

When he was done, a breeze blew again and the tree branches knocked into each other more. Almost like applause.

I walked over to him. He didn’t seem surprised to see me.

“Where have you been hiding?”

I shrugged.

“Everyone is out looking for you.”

I nodded. I shivered. It seemed much colder then. Away from my den.

“Your father is very worried.” He moved to the side and pulled the blanket from underneath him and handed it to me.

It was warm. I think that’s why he’d been sitting on it. And it smelled like campfire and spices. I wrapped it around myself and sat down next to him.

“But where they are looking, they will not find you.”

I thought that was funny since the hollow wasn’t that big. Not for adults. Although, I didn’t recognize where we were. I thought I knew everywhere in the hollow, but this place was new.

“Are you ready to go back?” he asked.

I thought for a moment. My dad would yell. I shook my head.

Mr. A. Tranjay nodded. He lifted the flute to his lips and started to play again. It was a different song this time. It sounded like tears falling into a gurgling stream. The notes warbled and spun and then stopped. Mr. A. Tranjay started coughing. He took out a handkerchief and wiped his mouth.

“That’s nice,” I said.

“Thank you.”

“What does it mean?”

He looked at me curiously. “What makes you think it means anything?”

I shrugged.

He extended the flute to me. It was covered in intricate carvings. And it was a strange color, like a brownish-white ash. A small gold tassel dangled from the top.

I looked at it.

“Go on.”

I took it and raised the end to my lips. “Is it okay?”

“Please.” He motioned to the air with a tattooed palm.

His hands were shaking. More than before. I think there were more symbols missing now. Like they were disappearing from his skin. Or he was sending them away. He was so skinny. Not just his body but his face, too. Like Wilson when I found him. I think he had stopped eating.

I pressed my lips gently to the flute. The wood felt soft. It wasn’t at all like the plastic tubes I had to play in music class. I didn’t have to push to make sounds. All I had to do was breathe and move my fingers up and down the holes. I didn’t really know what I was doing. But it was fun.

I stopped when I heard drops hit the leaves with a pit-pit-patter. I looked up at clouds rolling overhead. Just before it had been sunny.

“Don’t worry,” Mr. A. Tranjay said. “It will pass.”

“How do you know?”

“Because you didn’t finish the song.”

I looked up at the sky, at the island clouds moving by, and then back to the strange chef. “I did that?”

“Why are you sad?”

I was surprised by the question. “I’m not sad.”

“You played a very sad song.”

“So did you.”

The chef made a face like he’d been caught in a lie. “So it would seem.”

“Did someone die? Is that why you came here?”

“You are a very inquisitive boy.” He held out his hand.

I gave the flute back. He pressed it softly to his lips and moved it back and forth a little, like feet settling into a warm bed. Then he finished the song from before. When it was done, he looked at the flute before resting it in his lap.

“I suppose I am sad,” he said. He turned to me. “If I tell you why I am sad, will you tell me why you are sad?”

I looked up and thought. “I can’t,” I said.

“Why not?”

“I promised I wouldn’t say.”

He nodded and slipped the flute into a carved leather slip-pouch. “You know, if you don’t tell me where it’s hiding, I can’t help you.”

I looked down. I knew he meant my secret.

“But then,” he added. “I’m not sure I could be much help anymore.”

I wanted to pretend like I didn’t know what he was talking about, like adults do. Everybody knows they’re lying, but they do it just good enough. I thought maybe I should practice.

“What do you mean?”

“What were you feeding it? Your nightmares?”

I didn’t know what to say. I think we were quiet for a long time. “I dunno.”

“It is very dangerous.” He looked at me.

I pushed the leaves on the ground with my shoe.

“But then I think you know that.”

I shrugged.

“Come. Your father is worried.” He stood very slowly. His legs wobbled once. I had to help him.

“Are you sick?”

I held on to his hand while we walked. I don’t know if that was because he wanted to or I wanted to. Maybe we both did.

He said he wasn’t sick.

“Then how come you’re not getting better?”

He was silent for a few steps. The leaves crunched softly under our feet. I saw fireflies. They popped in and out and seemed to be following us.

Mr. A. Tranjay asked me if I had ever lost a balloon, and I said yes, I had. Last year my mom had taken me to the big fair they have in the fall and I had a balloon that looked like a poodle and I had lost it. I didn’t tell him the real reason. I had given my balloon to a girl who wanted it very bad. But she didn’t say. I could just tell. And it didn’t look like her parents had enough money to get her one. I think they were from a different country. So I gave her mine while my mom was getting us funnel cakes. Mom wasn’t very happy with me. She said it was irresponsible to lose it and I was old enough to know better and I had to eat my funnel cake and then we would go. I miss my mom.

Mr. A. Tranjay said a soul was like a balloon. Most of the time—which was all of the time for people like me—it was a bad idea to cut it open. But, he said, there were some people who had special knowledge, and they knew it wasn’t the cutting so much as the when and the where. That’s what he said. The when and the where. I liked that.

Then he asked me what would happen if you cut a balloon before it was full.

I said when the man at the carnival had made a mistake with one of the balloons and it had made an awful noise and flapped around and fell to the ground flat. I thought it was a waste. It had been very pretty, like a big, colorful flower.

He said yes, it would be a terrible waste. Then he asked what would happen if you cut a balloon while it was full. I said it would pop and kicked a rock on the path. I don’t remember there being a path in the hollow. We had been walking for a while. Longer than we should have if we were just going across. It seemed like maybe we had been somewhere else. Maybe the stag had taken me somewhere. To be safe. Maybe that was why no one found me. Except Mr. A. Tranjay.

Then he asked what would happen if, instead of cutting the balloon, you just cut the string.

I said I’d be sad because the balloon would fly away.

“But you weren’t sad before you had the balloon. So the happiness or sadness is not in the balloon, is it?”

“I guess not,” I said.

We passed a cluster of fireflies, which seemed like they stopped at the border of two big old trees. I didn’t remember there being trees that big in the hollow. We walked between them and left the fireflies behind.

Mr. A. Tranjay said we’re all like the flat balloons at the carnival: bright and colorful but empty until someone fills them up and ties them with a string. He said that we spend our lives tying more and more things onto the end so that eventually the balloon is so heavy it can’t get off the ground, and some pop. He said he’d been very busy lately cutting all his strings, although some had been cut for him, and he wasn’t very pleased about that. But he said he’d done such a good job that there was only one left—that very first string—and when that was cut, he would float off into the air, only I don’t think he meant actual air. I think he meant something else.

That’s when I heard my dad.

“Ólafur!”

He came running around the fence that ran along the hollow near Newcombe Street. He was in his long, dark coat, like what he wore to Grandpa’s funeral, and a red scarf. He had a cup of coffee in his hand and he threw it down to hug me.

I smiled. It was a good hug.

“Here he is,” Mr. A. Tranjay said. “None the worse for wear.”

“Thank God. Are you okay? Where have you been? We were so worried.”

There were some other people around. Adults mostly. I recognized a couple of them. I think they were our neighbors. One of them was Trevor’s dad. They were out looking for me. They smiled and shook my dad’s hand as we walked home. It seemed like maybe it was a big deal. My dad held on to me the whole way. It was a strong grip. I could tell he was mad. He was happy I was back, but he was mad, too.

Pringles was waiting at home. She had come back before me. And after I said hi to her and Wilson and Betsy and Speedy, Dad and I sat at the kitchen table and he made soup and told me there was a bad man on the loose, and that everyone thought he had taken me. My dad looked really tired. He looked like he’d run all the way to our old house and back. He said that just down the street someone had attacked a little girl, and that a few days before I went missing, some kids a couple streets over said something was chasing them.

“Was it like a bunch of spiders all together in a big bunch?”

My dad looked at me funny. Then he told me I couldn’t go into the hollow by myself for a while. Or anywhere. Even the library. Until they caught the bad man. He asked me if I understood, and I said yes. Then he said he was going to start locking the doors with a key.

“But how will I let Wilson and Pringles out to pee?”

“That will be my job. You just feed them in the evenings, and I’ll do the rest.”

I didn’t think that was fair. They were my pets. Dad was just doing it because he was worried. But he was worried about the wrong thing. Then he said something funny.

“You don’t have to go to school tomorrow.”

But it was the weekend. Tomorrow was supposed to be Sunday, but Dad said tomorrow was Tuesday and I could stay home for as long as I wanted and play video games. I didn’t think that was right. That it went from Saturday right to Tuesday.

When it was bedtime, Sudoku came and laid on my covers. She was an old dog and mostly slept downstairs. But I had been missing so she came to check on me. I petted her. She’s brown and white. I was in my red Phillies pajamas.

“Dad?”

“Yes?” He stopped in the doorway on his way downstairs. He told me I had to leave it open now. All the time. He hugged me a lot.

“If I tell you something, will you promise not to be mad?”

“That depends.”

I waited for a moment. Once I told him, there would be no going back.

“There was something in the garage. Before. I don’t know what it is, but it was hurting Emerald. I had it there and it got out. I’ve been looking for it. It came here, and I chased it into the hollow. Then I got scared and fell asleep.” I didn’t want to mention the stag again.

I saw my dad’s face. He looked so hurt. And disappointed. And angry. Like he was trying to keep from yelling at me. But mostly he looked hurt and sad, like he didn’t know what else to do. With me. Like maybe I wasn’t a good boy anymore. Maybe I was a bad kid.

Maybe I wasn’t a very good son.

“I know you said I couldn’t bring any more strays home, and that Betsy and Ribbon and Pringles and Wilson and Sudoku were enough, but this wasn’t a stray. It’s something else. I didn’t want it to hurt any—”

“Ólafur.”

I stopped.

His voice. I could tell. I could hear it. The way he said my name. I felt tears. He was so disappointed in me. My dad. He was so hurt and disappointed. Because of me. Because of everything I’d done. I was bad. My eyes got blurry.

“Let’s just talk in the morning, son. Okay?”

My lip was shaking. I swallowed. I nodded. My dad was so disappointed with me. “I’m sorry,” I said quietly.

“It’s okay, son. Let’s just talk in the morning. Get some sleep.”

I nodded. He didn’t wait for me to lay down and pull the covers over me like he usually did. He just walked away. He turned the hall light off and closed his bedroom door. He never did that. Not since I started having the nightmares.

I got up and tiptoed down the hall. I leaned close to the door. I thought maybe he was crying. I’d heard him once, after he found out about Mom. He cried a long time. I did, too.

But he wasn’t crying. He was talking on the phone. He was talking to a doctor. I could tell. Because of the words he was using. Big words. He was talking about taking me somewhere. To a hospital, maybe. He said the nightmares had stopped suddenly, but now I was seeing things and drawing horrible pictures of giant insects devouring children. And I had run away for two days and told him I was chasing ghosts. He said it seemed like my condition was getting worse, and he didn’t know what else to do. He was starting to feel like he couldn’t keep me safe and that was a terrible feeling and he just wanted some help.

“For how long?” he asked.

“Yes,” he said. “Yes, maybe that would be best.”

I didn’t want to go away from my dad. I didn’t want to be in a strange hospital with people I didn’t know. I didn’t want to get taken away again. I wanted to find my secret and stop it before it hurt anyone else. I wanted my mom to come back and for everything to be like it was. Before “the incident.”

My dad said goodbye to whoever was on the phone and I crept back to my room.

I couldn’t go to a hospital. I had seen what my secret did to Emerald. And the girl in the pink dress. It came back to the house because it was hungry. But it couldn’t get in. It couldn’t get to me. Something had stopped it. So it would find another kid. Maybe soon. Then it would find another. And another.

I had to stop it.

But I didn’t know how.

I’m posting the chapters of my forthcoming urban paranormal mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS. A blend of hard-boiled whodunit and contemporary urban fantasy, it’s scheduled to be released later this summer. You can sign up here to be notified.

You can start reading in order here: The old ones are patient.

The next chapter is: (not yet posted)

[image error]

May 18, 2018

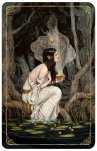

The Dreams of Jin Xingye

I love art that tells a story. Chinese artist Jin Xingye captures single frames from dreamlike stories, each a moment of a larger implied narrative.

[image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error]

[image error]

May 17, 2018

Razorback Fairy

This art by Emma Lazauski is almost exactly as I imagined the razorback fairies from my first book, FANTASMAGORIA.

From Chapter Three: A Radioactive Man Has No Friends

Gilbert stripped out of the heavy lead-lined suit as he walked to the bathroom. His thinning hair was wispy, and it reached for the ceiling as he removed his hood. His condition was getting worse. He could feel it. He was filled with energy. He barely slept. He had headaches every night. He needed answers soon. He showered and tried not to think about it.

Sitting at his workbench, minty and damp, he stared into the glass jar at its eyeless passenger. The dome of the creature’s cranium reached across its forehead and ended at two fleshless, skull-like nasal openings. Its skin was gray and soft. Its phalanges looked long enough to strangle a man. Its camouflaged wings resembled dead, black leaves, and they snapped together in angry clicks as the creature hissed at Gilbert through rows of tiny serrated teeth.

Gilbert set the glass jar down next to the terrarium. His three remaining live fairies, a male western crested blue fay and two female pink Winkler’s pixies, peered at the new arrival from behind the rock. The withering sprite was larger than the others by several inches. Gilbert wondered if it looked like a giant to them, or if, like insects, they were too stupid to notice. Either way, at least they were cowering at something besides him.

Gilbert took out the mounting block he had made for the withering sprite. He’d carved it custom. The withering was so rare, McMasters didn’t even keep a specimen tray large enough in stock. Gilbert pressed the inlaid cork to make sure the glue had dried. Then he pasted the information card to the right side.

Species: Withering Sprite

Genera: Winter

Gender: Unknown

Habitat: Unknown

Average Size: Unknown

Unknown, he thought. Perfect.

Gilbert looked up at the rear wall of his loft. It was covered in specimens: pixies, fairies, fay, and sprites of all sizes and colors hung inside small wooden blocks, sorted by genera, color, and type. Gilbert had a sizable collection of autumn and summer varietals and quite a few spring as well. Similar species tended to show similar coloration, and so there was a splotchy rainbow effect on the wall. Warblers tended to be purple or violet-hued—except for that blasted green meanie—and Gilbert had arranged them in a cluster near the bottom. Above the warblers were the mint pixies, then the dark spotted, then the western and eastern light spotted, and so on up to the crown jewel: Gilbert’s exhaustive collection of razorbacks, all reddish-hued and violent.

He had mounted the razorbacks in live-action poses, wielding small sticks like swords and poised mid-strike. (It was well-known that razorbacks, besides being potent insect-hunters, were one of the few species intelligent enough to use tools.) Taken together, the red collection looked like a dance of devils, a miniature dark mass, photographed and frozen.

In the center of everything was a picture of Gilbert’s dad. Carl Tubers had died of a stroke in a crowded elevator. Rush hour patrons had come and gone while he clutched his chest in silent agony, unable to move or call for help. Pressed to the back of the car by the crowd and then released, over and over, the coroner estimated Carl was stuck there, clinging to the rail, for the better part of an hour, surrounded by people who could help.

“Sorry, Dad.” Gilbert took the picture off the wall and looked at it. His dad was bald and scrawny and smiling. “You were only just a placeholder.”

Gilbert hung the empty mounting board on the vacant nail. It fit perfectly.

He walked back around his cluttered workbench and picked out the supplies he needed: the jar of ether, a cotton ball, an extra-large skewering needle. He cleared a stack of medical texts and set the equipment down. The withering sprite had stopped hissing at him. Its tentaclelike phalanges were pressed to the glass. A thick, mucous drool hung from the edge of the sprite’s rounded mouth as its eyeless head stared at the cowering fairies. Their tremors shook their wings, which shed a sparkling dander that floated down to the terrarium floor.

“I bet you’re hungry,” Gilbert said. “You had a long trip. How about one last meal?”

Gilbert loosened the top of the jar and placed it inside the terrarium. The pixies shrieked in high-pitched squeaks, like a record player run too fast. The two pink Winklers hid behind the crested male, who was standing upright, chest puffed, head and neck glowing blue, as the withering sprite worked the lid off.

The metal top fell with a clatter and the dark sprite fluttered out on black wings. It hovered in the air for a moment, and Gilbert thought maybe it wasn’t hungry after all. But as soon as he reached for the ether, the sprite swooped down on the crested blue, two-thirds his height, and batted him out of the way.

“Hmm . . .” Apparently it had a taste for Winklers.

The withering grabbed the closest pink, who was trembling and covering her eyes in fear, and sank its rows of teeth into her head. Gilbert could hear a slight sucking sound as the sprite inhaled the sap from her body. Her eyes rolled to the back of her head and Gilbert watched her tiny body shrivel like plastic wrap under the withering’s slow, steady sucking.

For his part, the crested blue was still trying to drive the giant away, but he was no match in size or ferocity. The withering sprite grabbed him by the head and dragged him, struggling, toward the second Winkler, who curled into a ball in the corner and sobbed uncontrollably. Her pink gossamer wings trembled to a blur.

The black sprite lifted the little pixie by her feet and bit into her side like an apple. There was a short shriek, then the slow, steady sucking again before she too was reduced to wrinkles stretched over a tiny skeleton. A bit of pink pixie sap dribbled down the sprite’s neck, and after it tossed the Winkler’s corpse aside, it wiped its face with the back of its hand. Then it lifted the crested blue, took off his head in one clean swipe, and started to munch on his thick, azure wings.

Gilbert watched the glow of the blue’s head fade. When it was dark, he again reached for the ether. As he dropped a soaked cotton ball into the terrarium, he heard a sliding sound. He turned and saw something in the middle of the floor. It was black. An envelope. It had come from under the door. He listened.

From the artist’s collection of bottled beasts:

[image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error]

The end of the world

Take a deep breath. Now, repeat.

It gets harder and harder to do that the higher you go, but there’s never a point where the atmosphere just stops. Like an aging celebrity, it just kind of faaaaaaades away….. which raises the question, where does the world end and space begin?