The Paris Review's Blog, page 723

March 26, 2014

Immune System

Living in fear of 1999’s Melissa virus.

My father died when I was six, and though I didn’t, couldn’t, step into his shoes, I did inherit his role as my family’s IT guy. When I was around eight, I installed Windows 95 on our home computer with no adult assistance. This was a source of enormous pride and stress. I had dreams involving catastrophic software failures, corrupt data, red error boxes, low-res neon-green background screens. I wanted to find something arcane in Windows 95, something mystical. I looked through every file it installed on our computer.

A few years later, at my prodding, we bought an America Online subscription and lurched into the merge lane of the Information Superhighway, where my stress compounded. If I had any doubt that the Internet was a wild, dangerous place, it was dispelled by the bray and hiss of the 56k modem, which seemed to tear into my phone line—implying the abrasion and contusion necessary to connect.

After that, though, came the chipper baritone of the AOL spokesman: “Welcome!” Within the cheery confines of AOL’s walled garden—buddy lists, channels, chat rooms—I felt, as the company wanted me to, safe. I had a screen name. I had a password.

Beyond its purview, I knew, in the real Internet, there were worms and viruses waiting in microscopic, cyberspatial ambush. The World Wide Web was booby-trapped. All a young man had to do was wander into the wrong Geocities neighborhood, and everything he’d worked to build would be eaten away from the inside: the saved states in his old collection of MS-DOS games; the chats he’d copied and pasted into text files; weezer.mpg, the file for Spike Jonze’s Weezer music video, which came bundled with his copy of Windows 95. As the custodian and chief architect of the family PC, I had to be vigilant.

I phoned my friend’s father, who had a home office in his basement and was so much the master of his domain that he smoked cigarettes there, indoors, as if it were nothing. I asked him: What sort of virus protection did I need to protect my machine?

Soon enough, I’d purchased—or, more accurately, begged my mom to drive me to CompUSA and supply the requisite cash to purchase—a digital prophylactic. The box for my edition of Norton AntiVirus featured a doctor, graying, authoritative, bespectacled and lab-coated, a stethoscope around his neck. Whoever alighted upon the virus as a metaphor for computer trouble was shrewd, but cruel. To declare that a computer can “get sick”—to align the corruption of files with the invasion of the human immune system—is a stroke of empathetic genius; to this kid, at least, it transformed the prospect from one of mild inconvenience to hysterical terror. I did not want an ill machine. I did not want to have to call the e-doctor.

And fortunately, I never had to. Barring the occasional brush with a Trojan horse, I, and my Micron PC with its Pentium processor, survived what was arguably the most benighted era of cyber-security in computer history. But I tried to keep my guard up. I followed the news, and in 1999, when the Melissa virus made headlines by infecting millions of machines, I was afraid.

* * *

“Melissa” came in the form of an e-mail; it was named after a stripper whom its creator, David L. Smith, had met in Florida. “Important Message From [so-and-so],” the subject line said, which would be, today, enough to raise a red flag for most of us. And if it weren’t, the rather graceless body text would be a dead giveaway: “Here is that document you asked for … don't show anyone else ;-)”

A graphic composed by Symantec, the manufacturers of Norton AntiVirus, in the aftermath of the Melissa virus.

That emoticon strikes me as remarkably guileless. Shouldn’t it have suggested that something was amiss, that things were not what they seemed? Maybe people didn’t read their e-mails as closely in 1999; maybe documents were circulating so rapidly that one could never remember if one had requested them; maybe everyone, everywhere, was e-winking. Whatever the case, millions found it advisable to open that “document.” They discovered an infected Word file, a list of eighty porn sites in which was embedded a self-promulgating code: Melissa forwarded itself to the first fifty people in your Outlook address book.

Fifteen years ago, this unsophisticated prank was enough to horrify me, and rightly so—with its exponential growth, it soon felled the mightiest of servers. Paul McNamara, of Network World, wrote on the virus’s tenth anniversary,

It was Friday, March 26, 1999 when Melissa first began to bring corporate and government e-mail systems to their knees. By the time all was said and done, hundreds of networks would be temporarily crippled—including those of Microsoft and the United States Marine Corps—an untold number of e-mail users would be affected, and an overall damage figure of $80 million would be bandied about.

David L. Smith, Melissa’s thirty-year-old author, was soon smoked out in New Jersey; he served twenty months in prison and helped the FBI track other virus writers.

“It is supposed on his part that the motive was to see if he could achieve what he did achieve,” the New Jersey Attorney General, Peter Verniero, said. But even that statement, admirably and almost existentially circular, goes too far. Smith seemed to have no real appetite for achievement, even for its own sake; he never expected Melissa to replicate on such a massive scale. He released the virus on a usenet newsgroup, “alt.sex.” He was a geeky man who liked porn, trolling other geeky men who liked porn.

“I remember at the time being surprised at how old Smith was,” Graham Cluley, who works in Internet security, writes. “Most virus writers at the time were teenage boys, not emotionally mature enough to have grown out of writing viruses which were predominantly designed to show off rather than make money.”

Which raises a good point. I was terrorized, in preadolescence, by viruses that were in large part the inventions of adolescents: an early, oblique form of cyberbullying. In a time before Facebook and YouTube, the older kids were still getting their jabs in, whether they knew it or not.

As I grew up, viruses and all manner of technological meltdown lost their grip on my imagination—the Internet also became, of course, better inoculated against them. But I can still picture the stress dreams I had then, and I can still remember the earnestness with which I treated my charge as IT guy: the sweat that would sheen my palms when I opened an e-mail from a stranger, the care with which I handled the instruction manuals to new software. I think my relatives wondered if I’d be an engineer, like my dad. But that illusion can’t have lasted long. In 1999, while Melissa made hell for the real IT guys, I was in the seventh grade, on the verge of failing pre-algebra.

Translating Pushkin Hills: An Interview with Katherine Dovlatov

Sergei Dovlatov, one of the great writers of the Soviet samizdat period, immigrated to New York City in 1978 and published his bone-dry, deeply thoughtful stories in The New Yorker all through the 1980s, until his tragic early death in 1990. Even in translation, Dovlatov’s work is a gateway drug to Russian humor: twenty percent booze, fifty percent understatement, and thirty percent bureaucratic despair. The writer is a household name in Russia, and the publication of Pushkin Hills—the first English translation of his 1983 novel Zapavednik, translated by his daughter, Katherine—has been greeted with celebration in the émigré literary scene.

The autobiographical novel is narrated by an unpublished writer, Boris Alikhanov, who takes a job as a tour guide at Pushkin Hills, a group of estates affiliated with Alexander Pushkin. Alikhanov’s wife and daughter are leaving him for the West, and he is thus forced to weigh the merits of abandoning his country, his mother tongue, and even Pushkin, his literary heritage. The alternative is to remain in Soviet Russia, where almost everything external is false, and where the absurdities of the Pushkin estate function as a microcosm for the society. As the narrator observes: “Christ, I thought, everyone here is insane. Even those who find everyone else insane.”

Using language to subvert the regime was one of Dovlatov’s specialties, and his novel is rich with characters who speak in tongues—the more insane you are, the more sane, perhaps, in a mad society. Dovlatov writes with a deceptive minimalism—in fact, his humor and linguistic dexterity have made him one of the most difficult Russian writers to translate. His daughter Katherine, who also represents his estate, was happy to discuss her technique with me.

Pushkin Hills was originally published in 1983, after your father had emigrated to New York. But he wrote it in Russian. Can you talk about that?

Father was “nudged” to leave Russia in August 1978. Like many émigrés of the Third Wave, he spent a bit of time in Vienna before coming to New York in the early months of 1979. He knew a lot of words in English, and he could get by on the street or supermarket, but I wouldn’t go as far as to say that he was fluent. He wrote everything in Russian. His writing is language driven, and so of course he wrote in the only language he knew well.

How were Russian-language works published and distributed in the U.S. at that time?

The best-known Russian book publisher in the U.S. at the time was Ardis, founded by two Americans, Karl Proffer and his wife Ellendea, who made an enormous contribution to the preservation of Russian literature. Karl died in the eighties, and Ellendea is living in California. Dad published several works with them, but Pushkin Hills was first released through Hermitage, which was founded by another Russian immigrant.

These weren’t publishing houses in the same sense as we think of them today, but they did everything from typesetting to distribution—mainly to universities, libraries, and Russian grocery stores, which had shelves of books, newspapers, perfume and fancy chocolates. Some authors paid to have their books published, some did not. My dad never had to pay to publish, but then he never got paid. He preferred payment in kind, that is, in copies of the book. He also micromanaged the process—my mother and grandmother proofread everything, and he designed the cover, approved the layout, et cetera.

His New Yorker stories were translated into English for publication—by whom? How did he like the work?

In the case of the New Yorker stories, it was Anne Frydman, the translator, who made the introduction to the magazine. Father met Anne through Joseph Brodsky, who had been in America a few years and was already established. Dad valued working with Anne so much that he divided his royalties with her equally.

His second translator was the famed Antonina Buis. She’s still working today. The one thing I remember is that Anne used to work very slowly. One story could take up to six months. Nina worked quickly, which was important to Dad. They both have their strengths and their weakness. Their styles are very different, but both have done a terrific job.

What were his opinions on translation in general? I’ve had so many Russians tell me not to bother reading various Russian authors in translation, as their work is “untranslatable.” It’s kind of a truism of bar chat.

It’s interesting that Russians can say a Russian work is “untranslatable,” and then at the same time believe that Russian versions of foreign works are improvements on the originals! Some say Shakespeare, for instance, is better in Pasternak’s version. And many, my father included, believed that Rita Rait-Kovaleva added to Vonnegut.

It’s interesting that Russians can say a Russian work is “untranslatable,” and then at the same time believe that Russian versions of foreign works are improvements on the originals! Some say Shakespeare, for instance, is better in Pasternak’s version. And many, my father included, believed that Rita Rait-Kovaleva added to Vonnegut.

My father knew and loved American literature. And yet he read everything in translation. And he believed that his stories were translatable—although he feared this particular work, Pushkin Hills, was going to present problems because of the particular and idiosyncratic ways two of the characters speak. That didn’t end up being the biggest challenge, actually.

What inspired your decision to translate it?

We had a contract with the publisher for three titles. Two were reprints. The third was supposed to be a brand-new translation. So we started looking for a translator. There were some very good samples from established translators in England, but I just could not reconcile Dovlatov with a British voice, British musicality. And so we continued our search. But as I was re-editing the existing translations to get them ready for reprint, I began to think that maybe I could possibly do it. The first sample was rejected by the publisher because it read too much like a translation. For the second submission, I changed my approach, after realizing that part of translating is also adapting the text to a different cultural perception, and the publisher liked it.

What was your process?

I don’t believe I have a process. I would read a sentence a few times, in my head and out loud, and then I would try to say it in English. The goal was to keep the same musicality, the same tone. It was mostly an intuitive process. And of course hearing my dad’s voice helped, too.

My father’s sentences are short, and at times I had to merge them to avoid abrasiveness. That changed the rhythm. But sometimes Russian, when you try to recreate it in English, can sound curt and accented, as if all the articles were removed.

As for the challenges, the more difficult parts were the authorial speech. Soviet references are untranslatable anyway, and the best I could do was try and relate the humor. Coming up with adequate slang and making up words was exciting. But the authorial speech is unforgiving. It had to be perfect. And my English is nowhere near my father’s use of the Russian. He honed his craft. He wrote slowly and painstakingly. I picked up English on the streets of Queens. It was a huge responsibility. I did not want to let Dad down.

Dovlatov had a famously strange rule. In a given sentence, he wouldn’t use a word that started with the same letter as a word he’d already used. First, is this true? And second, it looks like you didn’t abide by that rule in the translation. Why not?

It is true, although not of his earlier works. There’s been some discussion about this among Russian critics. Some call it a gimmick, others—fetters. I know that Dovlatov did not use this as a device or a gimmick. He used it to slow himself down. It was meant to be a self-editing mechanism.

And no, I did not do that in the translation. The proliferation of articles in English would have made it impossible. And I would have had to change too much. When Dad did it, for example, he would easily change a character’s name or a city to get the letter he needed. I don’t think translators can do that. Or can we?

Your mother is a major character in this novel, and in all of your father’s work. Did she read the translation? What did she think?

She read the translation, although after nearly forty years here, there are nuances of English that still elude her. That said, she found two typos! She tells me she liked it. She thought it read well and was funny. She particularly enjoyed the scene where the narrator meets the two village drunks.

The title posed some problems. In Russian, it’s Zapovednik, which means The Preserve. But you opted instead for Pushkin Hills.

This was the first and biggest hurdle. Zapovednik can mean a number of things—an animal sanctuary, or a tract of land set aside for people, such as a Native American tribe, which can carry negative connotations, or a museum-estate, which is a very Soviet concept. So it is a delineated zone of sorts, designed by man to keep things in, and it is a museum, the idea of which was unnatural, to my father. Unfortunately, in English, The Preserve expresses only some of those meanings, and taken out of context it fails to allude to the book’s themes. So yes, translating the title was my first failure!

La Vie Bohème

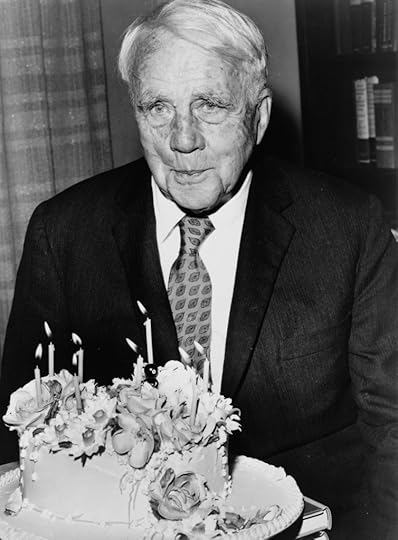

Robert Frost was born on this day in 1874.

Robert Frost, the poet and novice martial artist. Photo: Walter Albertin

FROST

Among other things, what [Ezra] Pound did was show me bohemia.

INTERVIEWER

Was there much bohemia to see at that time?

FROST

More than I had ever seen. I’d never had any. He’d take me to restaurants and things. Showed me jujitsu in a restaurant. Threw me over his head.

INTERVIEWER

Did he do that?

FROST

Wasn’t ready for him at all. I was just as strong as he was. He said, “I’ll show you, I’ll show you. Stand up.” So I stood up, gave him my hand. He grabbed my wrist, tipped over backwards and threw me over his head.

INTERVIEWER

How did you like that?

FROST

Oh, it was all right.

—Robert Frost, the Art of Poetry No. 2, 1960

Alice Munro Is Legal Tender, and Other News

Photo: Royal Canadian Mint

Alice Munro won the Nobel Prize last year, which is neat and all, but what’s even cooler is that her face is going to appear on a five-dollar Canadian coin—an honor second only to having a New Jersey Turnpike rest area named after you.

The world’s most expensive musical instrument: “a Stradivari viola, whose asking price will start at $45 million when it is offered for sale this spring.”

If one loses the ability to speak, a prosthetic voice offers the chance to restore one’s vocal identity.

What was on French television in the sixties? Michel Foucault and Alain Badiou discussing philosophy. Obviously.

If you’ve got two left feet, scientists have done you a solid: they now know exactly which dance moves catch a lady’s eye. The Electric Slide is not among them, experts say.

March 25, 2014

Shad Season

“The Shad (Clupea Sapidissima)” from the First Annual Report of the Commissioners of Fisheries, Game, and Forests of the State of New York, New York, United States: Commissioners of Fisheries, Game, and Forests of the State of New York, January 1896.

The thermometer outside my kitchen window reads thirty-nine degrees, firmly on the leonine side of March’s spectrum. But in the park, trees are budding. In the greenmarkets, forsythia are rearing their heads. And, in restaurants, shad are running.

Okay, they’re not actually running in restaurants. On my annual pilgrimage for shad roe, my better-informed dining companion told me that these particular egg sacs had likely traveled north from Washington, D.C.—maybe from the Potomac? The point is, shad are in season, whether one favors the bony fish itself or its slightly more approachable roe.

Shad and shad roe used to be a common spring meal up and down the Eastern seaboard. Nowadays, it is the purview of traditionalists and evangelical seasonal eaters. If you are neither, it is still the kind of edible time machine that is worth seeking out when you can. At the Grand Central Oyster Bar, the roe is served with bacon and a broiled tomato. Newly cleaned, the restaurant’s famous Murano tiles gleam under the lamplight, and commuters come and go, and even if you secretly think the shad is pretty overcooked and you’re kind of relieved not to have to eat it on the regular, all is very much right with the world.

You don’t need me to tell you that Cornelius Vanderbilt’s underground seafood house offers treats even to the shellfish averse. Like the Echo Wall in Beijing, St. Paul’s Cathedral, and the Salle de Cariatides in the Louvre, the hallway leading to the oyster bar contains one of the world’s handful of whispering galleries, an architectural oddity that allows one to hear the whispered communications of an interlocutor from a great distance.

Last year, I went with a friend for shad roe. After we ate, I said that I wanted to tell him a special secret. We took our places at diagonal points of the arched gallery just outside the restaurant. I whispered into the corner where the two walls of white tiles met. Like magic, my voice traveled across the vast room to his waiting ear.

“YOU DON’T LIKE ASTRAL WEEKS?” screamed my friend in horror.

So much for secrets.

“For Holly Andersen”

On April 8, at our Spring Revel, we’ll honor Frederick Seidel with the Hadada Award. In the weeks leading up the Revel, we’re looking at Seidel’s poems .

Bemelman's Bar in the Carlyle Hotel, New York. Photo: Arvind Grover

Over the weekend, I turned on Studio 360. A cardiologist was describing the health benefits of dance—and this cardiologist was none other than Holly Andersen, hero of a great poem by Frederick Seidel, from his 2006 collection, Ooga-Booga. Dr. Andersen is also the dedicatee of the poem. I guess you could say she is its muse, but hero is the better word. This is a poem about heroism: doing your job in the face of death. It happens also to be a love poem, for in Seidel’s work love and admiration are rarely far apart. I never have a drink at the Carlyle Hotel without thinking of the first lines, and I think of the last lines much more often than that.

Seidel has never given a public reading, but he has made several recordings of his poems, including this one. I played it as soon as the segment was over.

What could be more pleasant than talking about people dying,

And doctors really trying,

On a winter afternoon

At the Carlyle Hotel, in our cocoon?

We also will be dying one day soon.

Dr. Holly Anderson has a vodka cosmopolitan,

And has another, and becomes positively Neapolitan,

The moon warbling a song about the sun,

Sitting on a sofa at the Carlyle,

Staying stylishly alive for a while.

Her spirited loveliness

Does cause some distress.

She makes my urbanity undress.

I present symptoms that express

An underlying happiness in the face of the beautiful emptiness.

She lost a very sick patient she especially cared about.

The man died on the table. It wasn't a matter of feeling any guilt or doubt.

Something about a doctor who can cure, or anyway try,

But can also cry,

Is some sort of ultimate lullaby, and lie.

The Weather Men

The life, times, and meteorological theories of Josep Pla.

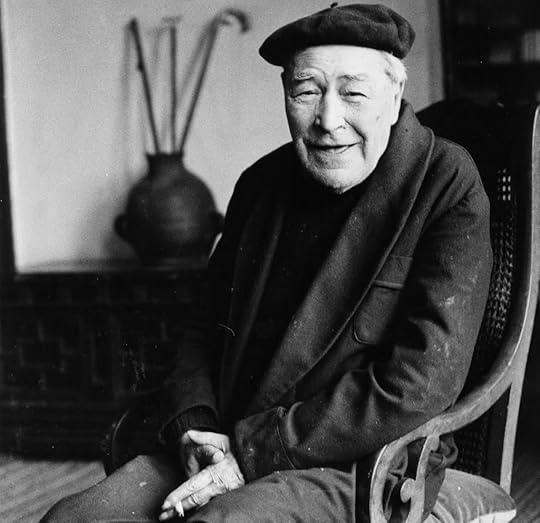

Josep Pla at his house in Llofriu, 1975.

“I’ve attended the procession of my country with a match in hand. Not an altar candle, not a torch, not a candlestick, but a match.”

Josep Pla (1897–1981) is a controversial figure in Catalan letters, and a well-kept secret of twentieth century European literature. If Barça is more than just a football club, then Pla—a political and cultural journalist, travel writer, biographer, memoirist, essayist, novelist, and foodie, whose collected works clock in at more than thirty-thousand pages and thirty-eight volumes—was more than just a writer.

Now that his deceptively simple, earthy prose and mordant sense of humor are available to American readers, the best way to read Pla is to curl up with a crisp glass of cava and a few spears of white asparagus. It’s impossible to read Josep Pla and not fall in love with his Mediterranean landscape. His native Empordà, with its mushroom-laced winds and its hint of burnt cork, mesmerizes.

Pla’s most important work, The Gray Notebook, is out now in a graceful translation by Peter Bush; the Daily published an excerpt yesterday. In the spirit of a bildungsroman and the form of a diary, the narrative chronicles 1918 and 1919, two crucial years in young Pla’s life. It captures the raucous energy of a precocious country boy who falls on his feet in the city, full of the spit and vinegar of youth. These were ebullient years in turn-of-the-century Barcelona; the city saw the first roiling curls of the belligerence that would lead to the Spanish Civil War, giving The Gray Notebook a tang of dramatic irony. But Pla’s masterpiece wasn’t actually published until 1966, after he had rewritten and reworked the material from his earlier diaries—a process similar to that of Proust, who returned to material written during Swann’s Way to fashion Time Regained.

In 1918, the Spanish flu epidemic forced Pla to abandon Barcelona, where he was studying law, and return to his village. Once the outbreak passed, he returned to the city and began frequenting the tertulias in Barcelona’s Athenaeum, using its well-stocked library and partaking of the charged social, cultural, and political atmosphere of the day. After graduating, Pla took off to Paris as a correspondent for the newspaper La Publicidad, initiating the first part of his writing life as an intrepid young reporter, travel writer, and cosmopolitan dandy. He covered Mussolini’s march on Rome and the collapse of the German economy from Berlin; in Russia, he met his countryman Andreu Nin, “the only practicing Nietzschean this country ever gave”; he traveled around Eastern Europe and witnessed many of the seminal events of the time.

But before all that, he had a farewell dinner with his circle in the Athenaeum, which he writes about in The Gray Notebook. In attendance was Salvador Dalí’s 260-pound elephantine uncle, Dr. Rafael Dalí; in the middle of the dinner, Dr. Dalí guffawed at a particularly saucy joke and was taken with an attack of the hiccups. “Dr. Dalí is paunchy and the spectacle of his paunch shaking with every hiccup was quite astonishing,” Pla wrote.

* * *

Pla was a polemical figure for many reasons; perhaps the greatest was that he practiced individuality when the collective urged consensus. “I sacrificed everything for my writing. Yet there is one thing that is perhaps my greatest passion: my private, intimate, and public freedom. Compared to that, everything else has no more value than a pipe’s worth of tobacco,” he wrote.

His writing doesn’t fit easily into any school or pervading style of the time, yet he’s the most important modern stylist in Catalan prose. At a time when the highly affected Noucentista style was the currency, he preferred a simple prose that could be parsed by the average reader. His was a practical, pragmatic approach to writing, an example of the seny (“common sense,” “restraint”) that is so characteristic of the Catalan sensibility: when it’s spoken by so few people, a language that is in the process of being standardized needs to reach as many readers as possible if it’s to grow.

Pla’s stylistic bylaws: Use natural words to describe the object. Unearth the adjectif juste like the pig who smells a truffle.

And Pla had a peculiar way of hunting these elusive adjectives. He literally smoked them out. As he worked on a sentence, he would take out his pouch of local tobacco, or “caldo,” as he called it, and begin the ritual of rolling a cigarette as he wrote and thought. With each movement of his fingers, the touch of the rice paper and the tobacco, the rhythm of the rolling and licking and finally puffing, he would draw the adjective out of its hiding place and capture the natural cadence of a sentence. “The only place you’ll find an adjective is in the pauses that result from the elaboration of a cigarette and its intermittent combustion,” he said.

In Spanish, as in Catalan, the words for time and weather are the same. Pla saw a strong connection between the two. He distinguished between physical time, “tiempo,” and the psychological time, “tempo,” of a human organism. “From the confusing, shapeless mass of psychological hours moments are produced, like sharp pricks, that project time onto our organism. They influence our lives decisively. They are the stitches of the Fates on the canvas of our lives,” he writes in his preface to Humor, candor. “We’ve lived through dangerous hours.” He was also prophetic: “The life of a fisherman is so tied to his environment, it’s such a marvelous life, that there’s no way it can last. How many centuries have they lived this way. Sometimes the sensuousness of the Mediterranean, the happiness of the country scares me. It’s a world that’s bound to be lost.”

* * *

In 1936, because of death threats by anarchists, he accompanied his fiancée Adi Enberg to Marseille. A Norwegian woman born in Barcelona, she worked as a spy for Franco. Eventually, the couple went their separate ways, and when Pla returned to Barcelona, Franco retired his passport—he’d written too many subversive articles. As the regime consolidated, Pla grew deeply disenchanted; the war had broken something in him, and he turned misanthropic, curmudgeonly, given to self-recrimination. He fled once again to the Baix Empordà, to isolate himself and recover.

Slowly, the dandy cosmopolitan was transformed into a sort of Catalonian Thoreau. He fell in love with the ancestral landscape, observing it with growing joy; it consoled him and he gave over to a sensual symbiosis, melding with it like a kind of neo-pagan Eros, eating its fish and vegetables, breathing its winds, smelling its violets and wild rosemary, touching its leaves and swallowing its minerals, contemplating the eternal indifference of the sea. “Here we live in a total cosmic dialectic. Seeing it has made me understand the human dialectic. How impossible it is that we’ll ever be able to understand each other,” Pla once said.

He came to believe that weather and climate determined character. The weather caused or relieved headaches, depression, elation; it made people boring or audacious, given to lethargy or fits of rage. Meteorology was an incipient science in the early twentieth century, and Pla thought it could become the “theology of the future.” He said the Empordà was locked in a perennial cosmic battle waged between the cold, dry north wind—the tramontane—and the hot, humid southeasterly—the garbi. In his article “Tiempo y tempo,” he writes, “This man has a stately and firm tempo, that one is more restless and caustic. How can they ever understand each other? The words each one uses can’t possibly mean the same thing. This man’s personality gives its best performance during a mistral or north wind, that man opens like a succulent when the languid, clammy, south wind blows.”

Spending his time with local fishermen, villagers, and farmers, he traveled around the countryside, delighting in the egg-yolk sun, observing the almond trees in bloom. He sipped at the sour homemade wine (read: vinegar) and referred to himself as a gentleman farmer who writes. Years later, in an act of pure Plasian mischief, he obliged the Prince and Princess of Spain, now King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofía, to drink this local wine with him when they visited Mas Pla in 1975, the year Franco died. “Isn’t it delicious?” he asked, his formidable shock of hair tamed unconvincingly under his beret, his coquettish beauty mark dancing a sardana over the bulge of his cheek, where his tongue was tucked to keep from snickering.

Mas Pla, a rural farmhouse in Llofriu, has been in his family for centuries; he finally moved there in 1946. It’s where his grandfather died, widowing his young grandmother by what is, according to Trivial Pursuit, the most common form of death by natural disaster: he was struck by lightning while watching a storm from the window. Once Pla installed himself there, Mas Pla became a place of literary pilgrimage, and he received many illustrious visitors, such as Camilo José Cela and Salvador Paniker. He died there in his bed, at eighty-four, after jotting a last note in his diary, in which someone visits a farmhouse and finds that the person whom they came to see isn’t there anymore because he’s gone out to feed the hens. “Magnificent,” he writes. “That’s the best possible news!”

* * *

Dalí and Pla. Photo: Enric Sabater

Another kind of king visited Mas Pla in 1977: Salvador Dalí, the other genius loci of the Empordà. Josep Pla affectionately called his old friend “King of the Carts.” Dalí arrived, moustache first, in a chauffeur-driven Cadillac, the same one now on display in his museum in Figueres. Pla once told him, “You’re going to poke a hole in something with that moustache,” which the painter found terribly funny. Dalí complains in his Diary of a Genius that Pla’s friends “usually have bushy eyebrows and they always have the air of suddenly having been plucked from some sidewalk café, where they had been sitting for at least ten years.”

Pla and Dalí first met at the Athenaeum in 1926, through the latter’s hiccup-prone uncle. In the history of the institution, only two members have ever been blackballed: Josep Pla and Salvador Dalí. Pla was constantly tearing his own articles out of the library’s magazines and newspapers, destroying the collections. As for Dalí, he gave an incendiary conference in 1930: after showing up a half-hour late, he called the president, Àngel Guimerà, a “fat pig,” an “immense hairy putrefaction,” and a “big pederast.” A group of men went after him with murderous thoughts, calling him a “good-for-nothing, foul-mouthed nobody.” Chairs flew. A few months later, Dalí sent the library a copy of his book, The Visible Woman, dedicated to the Athenaeum “putrefaction.” Meanwhile, they couldn’t officially kick Pla out—he’d never actually been paying his membership fees.

Pla was never as extravagant in his dramatis personae as the Empordà’s other prodigal son, but they are like animated emblems of the two words that characterize the Catalan volkgeist; seny and rauxà. Seny means restraint and common sense, rauxà means passion and reckless abandon. There can’t be seny without a little rauxà; it’s the cosmic balance of human nature, Pla’s battle of the winds. Both Pla and Dalí blamed their cantankerous natures on these elements.

Dalí told Pla that everyone talked about his impotence. Pla replied that he was, himself, the most erotic impotent of them all.

They finally worked together on a book titled Obres de Museu, the text by the master writer and illustrations by the master painter. In 2011 the journalist Víctor Fernández and Enrique Sabater published a posh limited edition with new images, new documents, and a 1,999 Euro pricetag. Dalí illustrated Pla in the landscape the writer loved; he was wearing his perennial beret, a symbol of his unpretentious subversion.

Franco had eased up by 1946—the year Pla moved into the farmhouse—and allowed books to be published in Catalan again. That year Pla’s Cartes de lluny, Viatge a Catalunya, and Cadaqués saw the light of day. The return to writing in his native language and the ability to travel again—now by tanker, to places like Israel, Cuba, New York, the Middle East, and South America— brought renewed energy to his writing. In 1966, he began compiling his thirty-eight volume collected works, which was inaugurated with The Gray Notebook. Six decades spent observing a place and its people, its winds, in a prose swept clean by the north wind. He pronounced their names in the long nights in Mas Pla before everything vanished into time’s thinnest air, the glassy air of Mediterranean skies. He had the good sense to die on the 23rd of April, 1981: Saint George’s Day, when the people of Catalonia come out to stroll the streets and exchange books and roses.

Valerie Miles is an American writer, critic, editor, and translator who lives in Spain. She is the curator of the exhibit “Archivo Bolaño 1977 - 2003,” and a co-editor of the New York Review of Books classics collection in Spanish and Granta en español. An English translation of her book A Thousand Forests in One Acorn will be published in September.

Dude Looks Like a Lady

Flannery O’Connor was born today in 1925.

O’Connor, right, with Robie Macauley and Arthur Koestler in Iowa, 1947. Photo: C. Macauley, via Wikimedia Commons

BARRY HANNAH

Flannery O’Connor was probably the biggest influence in my mature writing life. I didn’t discover her until I was at Arkansas, and I didn’t read her until I was around twenty-five, twenty-six. She was so powerful, she just knocked me down. I still read Flannery and teach her.

INTERVIEWER

What was it that got you? Was there something specific?

HANNAH

“A Good Man Is Hard to Find” and then I read everything.

I thought the author was a guy. I thought it was a guy for three years until someone clued me in very quietly at Arkansas. “It’s a woman, Barry.” Her work is so mean. The women are treated so harshly. The misogyny and religion. It was so foreign and Southern to me. She certainly was amazing.

—Barry Hannah, the Art of Fiction No. 184, 2004

All Your Favorite Shipwrecks in One Convenient Place, and Other News

Johan Christian Dahl, Shipwreck on the Norwegian Coast (detail), 1831.

If you woke up this morning and wondered, Will today finally be the day that the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS) puts together an interactive map of all known shipwrecks that have occurred off the treacherous Scottish coastline?, congratulations: .

Shut up the surly teenager in your life—remind him of how viciously teens were treated in medieval Europe. “A lord’s huntsman is advised to choose a boy servant as young as seven or eight: one who is physically active and keen sighted. This boy should be beaten until he had a proper dread of failing to carry out his master’s orders.”

Vis-à-vis cruelty: in Britain, it’s now illegal to send books to prisoners. Authors are protesting.

Back in the day, Orson Welles performed ten Shakespeare plays on the radio. You can listen to them.

“Not since the heyday of Dickens, Dumas, and Henry James has serialized fiction been this big.” Behind Wattpad, a new storytelling app.

What if classic writers wrote erotica? (Hats off to Camus’ Sutra, which is especially inspired.)

March 24, 2014

The Little Bookroom

Detail from the cover of The Little Bookroom, illustrated by Edward Ardizzone

This morning, it was announced that the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY) had named the Japanese writer Nahoko Uehashi and Brazilan illustrator Roger Mello the winners of the 2014 Hans Christian Andersen Award. Founded in 1956, the biannual “Nobel of Children’s Literature” honors outstanding contributions to both writing and illustration. Past winners have included Maurice Sendak, Paula Fox, Tomi Ungerer, and Tove Jansson. They are, of course, named for the Danish writer of the world’s most disturbing fairy tales, and the recipients are given a medal, emblazoned with Andersen’s likeness, by the Queen of Denmark.

The very first Andersen Award was presented to the prolific British writer Eleanor Farjeon, for her extremely bizarre collection The Little Bookroom. This book, illustrated by the peerless Edward Ardizzone, is composed of twenty-seven stories, all somewhat remote in tone, frequently redolent of loneliness, and often carrying a vague air of allegory.

To this day, a copy of The Little Bookroom sits on my nightstand, although I would be hard pressed to explain exactly why it should prove so comforting. The cozy title is misleading, although it derives from an actual room in the author’s childhood home. As she writes in the foreword,

Of all the rooms in the house, the Little Bookroom was yielded up to books as an untended garden is left to its flowers and weeds. There was no selection or sense of order here. In dining-room, study, and nursery there was choice and arrangement; but the Little Bookroom gathered to itself a motley crew of strays and vagabonds, outcasts from the ordered shelves below, the overflow of parcels bought wholesale by my father in the sales-rooms. Much trash, and more treasure. Riff-raff and gentlefolk and noblemen. A lottery, a lucky dip for a child who had never been forbidden to handle anything between covers.

Perhaps this gives some sense of the book’s appeal: it is rigorously unpatronizing, even though the author frequently adopts the lilting cadence of an oft-told fairy tale. In fact, some of the stories look, at first glance, like fairy tales: “The King’s Daughter Cries for the Moon,” “The Little Dressmaker,” and “The Giant and the Mite” feature casts familiar to anyone raised on Grimm. But just when the reader is lulled into comfort, the stories turn strange and elliptical. Desires are not gratified; people behave like people; life goes on. For instance, when the king’s daughter cries for the moon, the entire kingdom is dispatched to gratify her whim and chaos ensues. But,

“What’s for dinner?” they were asking all over the country; and the Women stirred the pots, and the Men went back to work, and the Sun rose in the East and set in the West; and the world forgot in less than no time everything that comes about when the King’s Daughter cries for the Moon.

Similarly, “The Little Dressmaker” seems to be leading towards a familiar conclusion: rewarded for her virtue and beauty, the protagonist will marry the young prince. Instead, the young prince turns out to be a footman, though they do indeed live happily ever after. In this respect, Farjeon was of her times: the literary fairy tale was a common form in the pain-shaded years following World War I. But she also wrote stories set in contemporary England, dealing frankly with matters of class and with childhood isolation. Whether her subject is homely or fantastical, her tone is unsentimental.

My copy is a library discard, still bearing a yellowed piece of protective plastic. I don’t remember a time when I didn’t own it, and the tattered hardcover shows its age. Like Farjeon’s childhood home, my parents’ house was an overwhelming jumble of books, and all kinds of things made their way onto my bookshelf.

Book editors hiring new assistants or interns tend to roll their eyes at certain phrases that pop up again and again in applications: “love of the written word,” “the smell of books.” These are common enough to suggest a fairly widespread fetish, and conjure images of opium den–style rooms full of slack-jawed addicts hungrily burying their faces in decaying Bantams. And yet we know what they mean. Paper stock and binding glue aside—and not to get too precious about it—few can deny that there is something deeply evocative about the sense-memory of a large expanse of assorted, uncurated books—much trash, and often much less treasure—at a library sale or used bookstore. As Farjeon writes, these “must all come to dust in some little bookroom or other—and sometimes, by luck, come again for a moment to light.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers