The Paris Review's Blog, page 724

March 24, 2014

Recapping Dante: Canto 22, or Don’t Play Too Close to the Tar Pits

This winter, we’re recapping the Inferno. Read along! This week: demons horse around in canto 22.

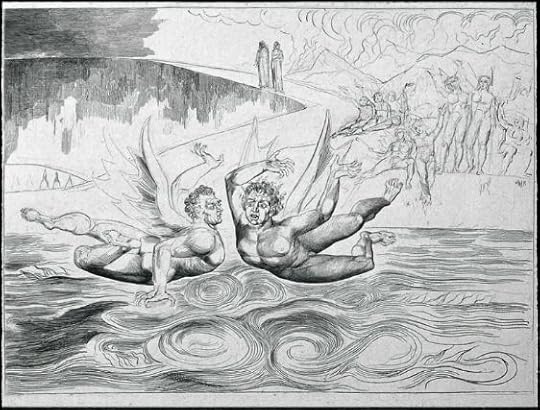

William Blake, Two of the Malebranche quarrelling, Dante’s Inferno Canto XXII, c. 1824-27.

The opening lines of canto 22 have a two-sided brilliance to them. First, there’s the way Dante—who is, along with Virgil, now in the company of demons—breathlessly describes the movements of a cavalry unit, the way soldiers will tousle hand-to-hand on the battlefield with war horns sounding through the air. It’s a nice lyrical passage that sounds like a nineteenth-century Romantic poet trying to modernize Homer’s battlefield passages. But then, absurdly, Dante juxtaposes those battle scenes with this “savage” band of demons; “as they say,” Dante writes, “in church with the saints, with guzzlers in the taverns.” It’s his polite way of saying that one must behave differently in the presence of demons who make farting sounds with their mouths and gather to the less-than-noble sounds of an anus trumpet. (See canto 21.)

As in the last canto, Dante is spellbound by a pool of pitch, where, now and then, he will see a sinner expose his back above the boiling liquid to relieve his suffering for a brief moment before diving back down. If the sinner stays above the surface for too long, a demon swoops down and tears him apart. Suddenly, Dante sees an overzealous sinner who has taken an irresponsibly long coffee break above the surface. Almost instantly, one of the demons grabs a billhook and prepares his talons so he can swoop down and shred the sinner to pieces. Dante has Virgil stop the massacre in order to learn a bit more about the sinner—he is from Navarre and accepted bribes when he worked for the king. Just as the sinner is about to be attacked, Virgil asks if there are any other Italians in the pitch. And who are we kidding? Of course there are going to be a ton of Italians in a place reserved for barrators. The sinner announces that he was just hanging out under the pitch with another Italian.

At that point, one of the flesh-hungry demons loses his patience with Dante’s whole I-gotta-interview-the-sinners shtick and rips out a chunk of the sinner’s flesh. Before he is overpowered, the sinner tells Dante and Virgil about the other Italians he knows—Fra Gomita and Don Michel Zanche, both from Sardigna and constantly yapping about the place. The sinner, who seems far more glib about the threat of being torn to death, says almost tauntingly, “Oh, look at that one there, gnashing his teeth.”

Trying to delay his punishment a bit longer, the sinner then offers to find some Tuscans and Lombards for Dante and Virgil to talk to. As I’ve noted before, this indirect form of identification is very common in Dante’s work. Dante the pilgrim has already been identified many times as a Tuscan, from the sound of his dialect. But what is strange is that the sinner knows that Virgil is from Lombardy by his accent; although Dante is addressing the issue of how the pilgrim and his guide communicate (we learn it must be in Italian), it also raises the question of why Virgil, one of the most important Latin poets, is not only speaking a language that didn’t exist for him, but is speaking it in the regional dialect of his hometown, Mantua in Lombardy. (And while we’re on the subject of plot holes: What exactly happens to the sinners after they’re torn to shreds?)

Another thing to consider is that the formal standardization of Italian was in part due to The Divine Comedy. This means not only that Dante’s dialect is very close to the standard Italian today (and that, as a result, I can read Dante in the original but cannot read a page of a twentieth-century Sicilian novel), but also that Lombardese might have been different than Tuscan. Thus, Dante has written a Virgil who speaks Italian, but whom Dante may have had some difficulty communicating with, because they spoke different dialects. It might have been easier if they both spoke in Latin.

The sinner assures Dante that he can get other Italians to the surface, but the demons see through his ruse and challenge the sinner to a game: Can he make it back into the pitch faster than the demons can catch him? The sinner accepts, and manages to escape. One demon, furious at another for letting his human rag doll go free, attacks the other. Before they can realize what has happened, they have both fallen into the pitch. As a demon rescue party sets out to discover that their fellow demons have been broiled to a crisp in the pitch, Dante and Virgil decide, wisely, to take this moment to sneak away.

To catch up on our Dante series, click here.

Alexander Aciman is the author of Twitterature. He has written for the New York Times, Tablet, the Wall Street Journal, and TIME. Follow him on Twitter at @acimania.

A Vitreous Vault

In 1918, when Josep Pla was in Barcelona studying law, the Spanish flu broke out, the university shut down, and Pla went home to his parents in coastal Palafrugell, Spain. Aspiring to be a writer, not a lawyer, he resolved to hone his style by keeping a journal. In it he wrote about his family, local characters, visits to cafés; the quips, quarrels, ambitions, and amours of his friends; writers he liked and writers he didn’t; and the long contemplative walks he would take in the countryside under magnificent skies. Nearly fifty years later, Pla published his youthful journal as The Gray Notebook , the first volume and capstone of the great Catalan writer’s collected works.

[image error]

Aigua Xelida (Palafrugell, Girona). Photo: Asier Sarasua Aranberri, via Flickr.

3 November 1918, Sunday. Spent with friends. Piera the tailor, Bonany, et cetera. I walk up to Sant Sebastià. A beautiful afternoon. The sinuous ribbon of road draws the loveliest afternoon light. I hear someone chopping wood in the distance. A donkey brays in a remote spot. A black-and-white magpie jumps over the green alfalfa. When I walk past Ros, I think, as I always do: I wish I owned Ros, the vineyard and the pinewood. By the hermitage, total solitude. Opposite Calella, boats—bobbing like walnuts—fish for squid. Two brigs appear on the Italian horizon, driven by a northeasterly wind. The sea is purple-edged beneath the hermitage terrace. Far out at sea, opposite Tamariu, another sailing ship is returning. A crabbing boat sails slowly by Cape Begur. An empty steamer passes arrogantly by, very close to land, spitting large mouthfuls of water overboard in fits and starts—like a dog barking. The water on the horizon turns deep violet; the water by the strip of land darkens. We circle the hermitage, marveling, awestruck. The afternoon seems in limbo, abstracted from time—a creation of the mind. If I could imagine or create another world, it would be a world like this.

We return at dusk. The road is thronged by the shadows of hunters and mushroom pickers; we hear the hum of invisible people conversing. As I stand on En Casaca bridge, I remember the frog that sang there in summer. The evening dissolves into a delicate gauze, a misty haze floating and shimmering above the land. The sky is very clear and the starlight cold and metallic.

A night at the cinema. Frou-Frou, with Francesca Bertini, Gustavo Serena, and the usual Italian suspects. A very ordinary plot played by people who spend hours and hours posing for their portraits—who would like to pose, night and day, indefinitely. Bewildering, enthusiastic cries of admiration go up from the audience when a luxurious set or an elegant dress puts in an appearance.

As we leave the cinema, Roldós plays a Schumann score for Coromina, lluís Medir, and me. Schumann never got a note wrong. He is as round as an apple. Or an almond. Though slightly sweet, with a circumference that’s ever so, ever so slightly too perfect. Schumann seems two-dimensional. Chopin, three.

[image error]4 November. Feeling idle, unable to devote a moment to my textbooks, rather bored by café conversation, I go for an afternoon stroll. I walk along the road to Llafranc. At this time of year, the plain of Santa Margarida is simply beautiful. I can’t walk by the fence around Can Vehí without remembering the scent of the roses of Sant Ponç. Llafranc is so deserted it seems skeletal. You sometimes see a gaunt figure taking a stroll, or a hesitant cat or dog, on the other side of the beach. Everything reinforces the effect. Seagulls flap their wings near the beach, above the green sea. They emit cries now and then that sound almost human. As dusk approaches, the contours of the mountains in the west glow with an archaic light. I wrote: an archaic light. What is an archaic light? I mean a light from an antique painting, the luminosity that remains on a painting when it’s engrained with centuries-old layers of dust and grime. Like a light that passes through thick, yellow glass. To the west—Maragall’s warm, gentle west—the vineyards in the foreground are blood-red. The crab fishers returning to the Bo port in Calella, helped by a blustery tailwind. When I gaze at the pine trees by the side of the sea it makes me think of the curves, the idiosyncratic, unmistakable arabesques painted by Joaquim Sunyer. A Gypsy woman stands under a streetlamp by the entrance to town cradling a half-naked child: The child opens her eyes wide, too wide—perhaps from the cold. These eyes also make me think of eyes painted by Joaquim Sunyer.

At night in bed, I return to Plato’s Dialogues. How wonderful! In the early hours, fifty gross, crazy roosters are screeching, but I can’t switch off the light. The power of suggestion is so strong, so fascinating I sometimes think that it’s inevitable I will encounter Socrates in the street one day. I don’t think this could happen with any other figure in the history of culture. How is it possible to suggest so many things with so few words, in such an apparently simple fashion?

5 November. Coromina has purchased a motorcycle—one of the first to be ridden in the country. He is beaming and—as one would expect—has become an ardent champion of motorcycles. He has bought a helmet, goggles, and some flashy gloves. He is almost scary.

Today he made me try out the attractions of his new toy, so I straddled the rear seat—if it can be called a seat. We sped along the Bisbal-Pals-Begur-Palafrugell circuit. Hellish roads that Coromina climbed cheerfully.

The machine flies and that sensation of flying would feel even more real if it weren’t for the hugely uncomfortable seat. The ridges in the road resonate on my posterior through a merciless iron mesh separated from my flesh by a single, stupid cushion that has no substance or guts. But I act bravehearted. I have no choice.

Now and then, he turns around slightly and says, “Are you all right? We’re going seventy an hour.”

“I am fine. My backside’s hurting a lot, I’m not sure I can stand much more, but I think it’s a wonderful experience.”

“You’ll soon get used to it.”

“Many years from now maybe. We’ll see!”

We stop in Begur and drink a glass of cognac. It’s the drink of choice for those who deal in iron engines and tools. I reflect on our trip for a moment. I realize that I wasn’t at all frightened. If it had been any different, I would say so. I found the speed fascinating though never what you might call rapturous. They are unique moments when you forget almost everything else. Though not entirely. The machine always made me feel safe—for example. And something else was always mentally present—an awareness that my butt was slowly becoming a misshapen, painful lump of dough.

“Forget it!” Coromina exclaims, sternly. “If you say so.” Just then Lola Fargas crosses the square, dressed for winter. She is a pure delight. I find it incredible that women who can be so shapeless and off-putting can furnish such distinct, tangible beauty. What an apparition! I try to interest Coromina in my thoughts. But it’s hopeless. He is obsessed by his machine. He has become the perfect motorcyclist and dodges the issue with a platitude worthy of the village wit. He says, “Yes, you can say what you like, but her beauty is as fleeting as the road my bike leaves behind it.”

The old road from Begur is hellish and on our way back we have to do without gears. Nevertheless, my nether parts continue to suffer. I reach home a sore, battered, mutilated man, as if I’d been given a real caning. But all in all the worst of the journey was Coromina’s wisecrack. His sentence is a sure sign that machines will create literature, and horrible literature at that.

[image error]

Photo: Asier Sarasua Aranberri

The newspapers are full of grim news. Half of Europe is collapsing, like a battered building that’s subsided and falling apart. Russia, Austria, Germany … my feelings sway me toward the side that’s collapsing. My reason doesn’t!

At night I read Pompeu Fabra’s Catalan Grammar. It brings to mind a standard European grammar—Augier’s French Grammar, for example—and above all it makes me forget those grisly texts that made high school such a torture. How beautiful a grammar that is clear, simple, precise, and understandable! As I read, I wonder how I could make so many spelling mistakes. I can’t seem to impose any discipline on myself. This feeling of insecurity I have when I discover I’m a slovenly bohemian is extremely unpleasant. However, there’s nothing at all I can do about it …

6 November. In the afternoon, I walk up to Can Calç de Sant Climent along the path by the cemetery and the Morena spring. It’s a farmhouse that belongs to my mother: three hundred square yards of cork oaks, a shadowy kitchen garden, a small patch of thin wheat-growing earth, and an old family house on the ridge. All in the parish boundaries of Fitor.

It’s a luminously white afternoon with a cream-cake glow in the sky. The snow on the peak of El Canigó is opaque and dull. Its lower, snowless buttresses are gray, soft, and doughy. Water whines down irrigation channels. Everything is damp and slimy.

The woods are full of voices. Woodcutters are chopping everywhere. You occasionally hear the sound of a tree falling. The owners make charcoal or sell the logs. It will soon all be bare. It’s an astonishing sight. The number of trees that must have been felled in these war years is crazy, too many to count.

At three o’clock I reach the Teula spring. The water flows impassively in that dark, solitary spot. The remnants of a banquet of snails litter the stone table. The surrounding shabby eucalyptus trees secrete sadness. Country springs are so cheerful in summer, so dismal in winter. When I reach the Fitor saddle, past the dead vines, the vista opens up and out: I see the dull, tinny sea by Estartit and the Medes Islands.

The farmhouse is a rural drama. I’m almost afraid to go in. When they see me coming, they give me strange, suspicious glances out of the corner of their eyes. It’s hard to start a conversation. Luckily, two hungry hounds, ears drooping, pad over and sniff my shoes. That provides an excuse to talk. The forlorn, squalid house is home to the tenant farmer, his wife—a twisted, squint-eyed, filthy woman with unkempt hair—a coal-black charcoal burner, and a son of theirs who looks like a complete moron.

Naturalism—I believe—has just one defect: telling it as it is. Carner’s quip about reading naturalist books with a bouquet of roses at your side is rather trite, but it is sensible advice. Naturalism will never be popular because it implies the description or recognition of that sewer—large or small—where we all slog. We mount our mean, miserable convictions over that sewer. Gori is right: idealistic literature will always be what readers like—even if it is a fairy tale, as long as it is idealized.

I walk back at dusk, through the damp cork-oak woods. Owls fly across the low, gray sky.

Before supper, a long conversation with my father about the new map of Europe and the massive upsurge of socialism. My father, who’d clung to the idea that Germany would win the war as long as possible because—in his view—it was best for the onward march of progress, is shaken. Nonetheless, curiously enough, we speak perfectly calmly. Personally this sudden advance by the poor impresses me: an inextricable mixture of satisfaction and fear.

At night, at the club, my friends and I pitch in to play baccarat. When it is time to add up it turns out we have won four pesetas per head, that is, sixteen coffees each.

Afterwards, Coromina and my brother—a chemical sciences student—get embroiled in an endless argument about science. To my great surprise, Coromina attacks my brother’s deeply rooted belief in the absolute priority of science in any system of human knowledge. Like all anti-rationalists, Coromina fashions brilliant, beautiful turns of phrase: He says, for example, that the discovery of Hertzian waves was more the fruit of poetic intuition than of any systematic observation. My brother is indignant. It has always been a mystery to me that some people seem fated to be rationalists and others anti-rationalists. Why? Is it prompted by the branch of studies or the body of knowledge pursued? I think not. There are very sensitive individuals with artistic temperaments who are rationalists, and individuals obsessed by particularly technological inclinations who are anti-rationalists. Is a difference in temperament the root cause? Or a difference in curiosity? There are rationalists with extreme tunnel vision. Generally anti-rationalists are not interested and are indeed irritated by any tangible scrap of knowledge. Why?

The smallest, most fundamental problem hurls me into an abyss of ignorance and sadness.

[image error]

“Baldomer Gili Roig. Calella de Palafrugell, 1905-1925.” Photo: Museu d'Art Jaume Morera

A long, solitary stroll in the early hours, along the town’s deserted streets. I see the light from the Sant Sebastià lighthouse burning from different positions. The beam shines ineluctably, with perfect precision. At four o’clock, it is still burning. Faced by the relentless tenacity of machines I can’t help but think about the extent to which man has been diminished. One sometimes feels like taking a bucket of water and putting out that light.

7 November. A very loud, noisy family row. They heard me come home too late. I’ve still not been able to solve the problem of entering the house without making noise. I can’t report any progress on my old pledge to become economically independent. I serve no purpose. I am totally useless.

I spend the afternoon reading. Zola is considered a naturalist, but I see in the Mercure de Paris that in fact he documents himself very little on real humans. So just as you eat slices of melon in the summer, naturalists devour slices of life. However, Zola generally improvised, invented. That explains one thing that had baffled me until now: the one-sided, rather simplistic, rarely contradictory psychology of the characters in his novels. They are characters—with different clothing, in a different era—of a piece, hewn from a single kind of stone, like Racine’s.

I am rereading Shadows on the Peaks, by Ramón Pérez de Ayala, which impressed me when it was published. Now the book drops from my hands. It is a brilliant first novel, no doubt. Ayala has real, natural control over the spiraling sentences of Castilian prose—something Baroja and Azorín don’t have.

It was a bright day and a warm afternoon that waned as I watched through my window. Twilight clusters of dark clouds against the off-white vault of the sky, a touch of pink and streaks of purple in the west.

Before dinner, I pop into the arts school for a moment. I find lluís Medir, Coromina’s assistant, tidying away materials with a passion for order, cleanliness, and efficiency I find admirable. lluís Medir is one of the most estimable youngsters of my generation, with a striking understanding of concrete things. I think I am drawn to him largely because of my own—often frenzied—longing to learn. Deep down I am only interested in people who can teach me something. I feel Medir is well aware of this.

Aperitifs unravel the final part of my day. Countless cafés after supper. I lose my hat and coat playing baccarat. A second supper, late at night, with my friends. I never have money but there is always somebody who does. Besides, people are trusting. Gori eats solemnly, like a priest. Someone decides to order manzanilla. The Spanish drink gives me a splitting headache. Pain at the top of my head—between the encephalic mass and my skull. We spend the last hours of the night in the brothel. Paquita.

[image error]

“Baldomer Gili Roig. Calella de Palafrugell, 1905-1925.” Image: Museu d'Art Jaume Morera

8 November. A stroll along the road to Sant Sebastià. A beautiful, colorful day. The sky is a bright gray, a swarm of light. The pale whites are wonderfully subtle. On the house walls certain whites seem alive. Trees pose elegantly in the gray mist. A gentle breeze blows, like a rose petal caressing one’s skin, and makes the bamboo hum. The mountain is full of mushroom hunters. I climb Cape Frares via Ros. A magnificent spectacle. From the side of Sant Sebastià, the raw, vertical geology is oppressive. The scene is more appealing to the north: a pale leaden Cape Begur, pinkish Cabres Cove, and Aigua Xallida. Tamariu, above the dark green of the pinewoods. The sea is a grayish blue. Banks of great cottony clouds on the horizon drenched in the light of sunset. The land in repose. The red vines are a ripe, creamy, oily red. A cypress dreams. The west dissolves into orange juice.

At dusk, from one window I can see a flock of sheep munching grass in the old cemetery. I can make out a bunch of white flowers—little white heads—as if some child were buried beneath. Beyond, the grass fields seem to be shivering from the cold.

A bright, animated night under a vitreous vault.

At two in the morning a fire alarm sounds. The sinister bells underline how peaceful the town is—peace that can strike terror. Tomorrow people will be saying: First, they store; then they burn. I don’t think there is a community in the world more insensitive to fires.

Translated from the Catalan by Peter Bush.

Josep Pla (1897–1981), the eldest of four children, was born in Palafrugell on the Costa Brava to a family of landowners. He studied law in Barcelona, abandoned law for journalism, and in 1920 moved to Paris to serve as the correspondent for the Spanish newspaper La Publicidad. Banned from Spain in 1924 for his criticisms of the dictator Primo de Rivera, Pla continued to report from Russia, Rome, Berlin, and London, before returning to Madrid in 1927. He supported the new Spanish Republic that emerged in 1931, but was soon disillusioned and left the country during the Civil War, returning in 1939. Under the Franco regime, he was internally exiled to Palafrugell and his articles for the weekly review Destino were frequently censored. After 1947 his work began to be published in Catalan, and his complete works were published in full in 1966. They comprise forty-five volumes, of which The Gray Notebook—begun in 1919, but polished and added to throughout the intervening years—is the first.

Reprinted with the permission of New York Review Books.

Copyright © 1966 by the Heirs of Josep Pla.

Translation copyright © 2013 by Peter Bush.

Take a Mental Vacation—Listen to Travel Writers

Paul Theroux on a train, doing what he does.

What do Paul Theroux, Ryszard Kapuściński, Peter Matthiessen, and Jan Morris have in common? All four have advanced the art of travel writing, or writing that foregrounds a sense of place. And over the years, all four have been interviewed at 92Y’s Unterberg Poetry Center, where The Paris Review has copresented an occasional series of live conversations with writers—many of which have formed the foundations of interviews in the quarterly. Now, 92Y and The Paris Review are making recordings of these interviews available at 92Y’s Poetry Center Online and here at The Paris Review.

As yet another cold front shunts frigid air in our direction, it’s especially nice to hear smart people talk of exotic climes and faraway places. So you can listen to Paul Theroux, who spoke to our beloved founder, George Plimpton, in December 1989:

I came from, not a small town, but basically not a very interesting place. I felt that the world was elsewhere and that nothing was every going to happen to me, or that I wouldn’t actually see anything, feel anything, any sense of romance or action, or that my imagination wouldn’t catch fire until I left home. So it was very important for me not to rebel but simply to get away, to go away …

Or a conversation with Jan Morris, who appeared at 92Y that October:

I resist the idea that travel writing has got to be factual. I believe in its imaginative qualities and its potential as art and literature. I must say that my campaign, which I’ve been waging for ages now, has borne some fruit because intelligent bookshops nowadays do have a stack called something like travel literature. But what word does one use? … I think of myself more as a belletrist, an old-fashioned word. Essayist would do; people understand that more or less. But the thing is, my subject has been mostly concerned with place.

Or Peter Matthiessen, another cofounder of The Paris Review, from 1997:

It’s broad daylight, good visibility, yet mountains move. You perceive that the so-called permanence of the mountains is illusory, and that all phenomena are mere wisps of the cosmos, ever changing. It is its very evanescence that makes life beautiful, isn’t that true? If we were doomed to live forever, we would scarcely be aware of the beauty around us …

Or Ryszard Kapuściński, from 1991:

If we write about human beings, in the most humanly way we are able to, I think everybody will understand us. I find humanity as one family. People really are very much the same in their reactions, in their feelings. I know the whole world. I can’t find much difference in the way men react to others’ unhappiness, disasters, tragedies, happiness. Writing for one man, you write for everybody.

These recordings are the next best thing to a vacation. Their release is made possible by a generous gift in memory of Christopher Lightfoot Walker, who worked in the art department at The Paris Review and volunteered as an archivist at 92Y’s Poetry Center.

Your Aura Is Orange and Squiggly, and Other News

Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater, “The Intention to Know,” a synesthetic illustration from Thought-Forms (1901).

That wild pope of ours—what’s he up to this time? Why, he’s hiring a Japanese tech firm to digitize the whole of the Vatican Library’s archives, of course! It’s almost as if this pontiff wants to make the world a better place.

Victorian occultists believed in a kind of synesthesia, “the theory that ideas, emotions, and even events, can manifest as visible auras.” Fortunately for all of us, they made many terrific illustrations to support this theory, too.

A landfill in New Mexico may contain truckload upon truckload of the worst video game of all time: Atari’s 1982 E.T. tie-in.

After years of trying to sweep him under the rug, atheists are finally talking about Nietzsche again.

Turkey’s Twitter ban has spawned a new Web site, Mwitter, which is semantically pretty fascinating. (Look for Elif Batuman in the comments section.)

March 21, 2014

What We’re Loving: Digressions, Disappointments, Delicious Kisses

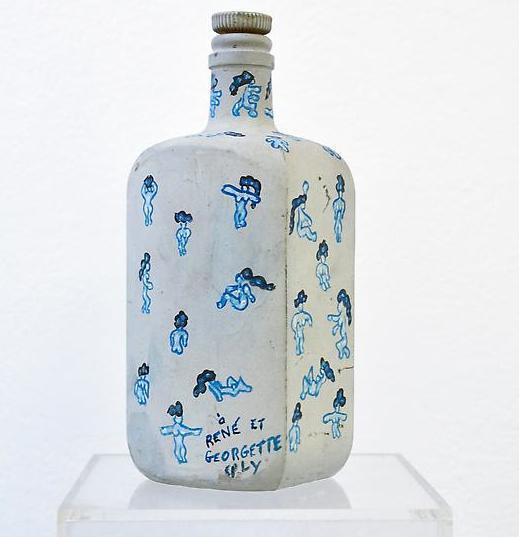

William N. Copley, Untitled, undated, hand-painted Marie Brizard glass bottle, 8 x 3 x 3 inches. Image via Paul Kasmin Gallery.

Paul Kasmin Gallery has a show up about the Iolas Gallery, which was open from 1955 to 1987 and was helmed by Alexander Iolas. He’s best remembered as the dealer who (along with William Copley, in California) helped introduce the Surrealists to the American art world; the work on view, which he originally showed, is worthy of a museum exhibition—paintings by Magritte, de Chirico, Ernst, and Man Ray. But Iolas championed art that suited his taste, rather than art that was trendy, which means he liked what was, at the time, very weird stuff—such as Joseph Cornell, Copley, and Takis. He gave Warhol his first gallery exhibition when the artist was eighteen, and he was the first to show Ed Ruscha in New York. In Paul Kasmin’s showcase, there’s a wonderfully big, ethereal painting by Dorothea Tanning and a bronze toilet in the shape of a fly (the paper is dispensed through the fly’s mouth, and you can store reading material in a bin under its thorax) by Les Lalanne. My favorite, though is a hand-painted glass bottle by Copley covered with tiny blue nudes, a modern take on the Grecian urn. —Nicole Rudick

In our recent interview with Matthew Weiner, the Mad Men creator states, “To me … digressions are the story.” César Aira’s wildly funny novel, The Conversations—recently translated by Katherine Silver—is one long digression: two friends discussing an action movie argue over the inconsistency of a Rolex watch on one of the film’s goatherd characters. This seemingly small error sets off an exploration of, among other topics, the reinterpretation of memory, reality vs. fiction on film, and storytelling in our “technological state of globalized civilization.” As Aira writes, “What had seemed about to come to an end had, in fact, just barely begun.” —Justin Alvarez

I realize I’m 993 years late to this party, but Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji, as centuries of scholars and readers know, is one of the richest and soapiest books ever written—not bad for what’s arguably the first novel ever. The story follows Emperor-spawn Genji as he navigates his way through the Imperial Court of eleventh-century Japan, marrying, political-intriguing, philandering, marrying again, and predating Freudian psychology by nearly a thousand years. The Penguin edition, translated by Royall Tyler, retains the high language of the original Japanese while situating the modern reader in a world in which poetry could make policy—would that it could today!—and the intricacies of court hierarchy could make even a Junior Fourth Rank, Upper Grade Left Officer’s head spin. —Rachel Abramowitz

I’ve just received a new translation of Louise Labé’s love sonnets and elegies. Labé wrote during the French Renaissance; after her death, her poems fell into obscurity until they were rediscovered in the nineteenth century. Earlier today, I flipped through its pages and landed on Sonnet 18, which brought an immediate smile to my face. It begins,

Kiss me, rekiss me, & kiss me again:

Give me one of your most delicious kisses,

A kiss in excess of my fondest wishes:

I’ll repay you four, more scalding than you spend.

You complain? Well, let me ease your pain

By giving you ten more honeyed kisses.

What it lacks in subtlety it recoups in passion. No need to compare your love to a summer’s day: just bring on the kisses. —Dan Piepenbring

This week I reread The Journal of a Disappointed Man & A Last Diary, by W.N.P. Barbellion (real name Bruce Frederick Cummings), who was crippled by multiple sclerosis and kept a journal from 1903 until his death in 1919. Aware that he is dying—and angry that he can’t find an outlet for his ambition or his amorous feelings for beautiful London women—the diarist manages to be fascinated by all things in life—the tines of a fork, head lice, “the bare fact of existence.” This book is a little heartbreaking, but better than that, it’s also very funny. Open it up on just about any page, read any sentence, and it’s bound to be gold. —Anna Heyward

Thanks to 50 Watts, I stumbled upon the Times art critic Ken Johnson’s comic, Ball and Cone. Johnson describes the premise: “Ball and Cone encounter a series of metaphysical (and often comical) conundrums—and remain side by side as they face these challenges together.” For a better grasp on the philosophical playground Johnson has created with these two characters, read this great , conducted by Claire Donner. “Despite their inadequacies,” Johnson writes, “Ball and Cone have some pretty interesting adventures.” —J.A.

A Few Notes on Presiding over the Punch Bowl

William Hogarth, A Midnight Modern Conversation, 1730

March 21st was my maternal grandparents’ wedding anniversary; they were married in 1946 in Silver Spring, Maryland, my grandmother’s hometown. As a child I loved to pore over the Silver Spring Standard wedding notice in her scrapbook, which contained lines like, “The church was massed with spring blossoms, a fitting setting for the exquisite beauty of the bride herself, in her ethereal white marquisette gown and flowing lace.” (“TERRIBLE write-up,” my grandmother had written in the margins.)

What struck me lately, as I reread the notice yet again, was the range of tasks assigned to the wedding guests. The maid of honor and best man were duly accounted for, but there was also this: “Mrs. Elizabeth McLean presided at the coffee urn and Miss Mary Roberts at the punch bowl.”

A cursory Internet search shows that this was indeed a thing: if you google “presided over punch bowl” or “presided over coffee urn,” you’ll come across a raft of vintage wedding and party notices, all of which describe the dispensing of beverages. What I really wanted to know is, was this duty—which sounds dull, potentially messy, and interminable—considered an honor, or was it a sort of booby prize for extra relatives? “Presides” has a regal ring, but the task itself sounds akin to light drudgery.

One also wonders whether the punch-bowl president was supposed to be a sort of killjoy: one recollection of a Savannah New Year’s party mentions that, as a rule, “One of the hostess’ best friends, dressed in a hoop-skirted gown, presided over the punch bowl, guarding it carefully in case a jokester decided to drop in a bit of bourbon.” Another write-up references “the three married women who presided over the punch bowl,” suggesting that this was no job for an untried virgin.

The most recent iteration of Emily Post, in her section on receiving lines, has only this to say: “When the receiving line is held at the reception site, have a waiter offer a variety of drinks—juice, punch, sparking or still water, Champagne—to those waiting in line. Be sure to have a small table where guests can place their drinks before going through the line.” Clearly, this is not a position that enjoys the respect it was once due, at least in some places. But think about it: who else “presides” at a wedding? The officiant, that’s who. The punch-bowl and coffee-urn women are, in their way, second in importance only to the law and God.

Here is the most unlikely thing I found, from a 2001 edition of New Jersey’s Amityville Record:

On Sunday, December 10, the Amityville Historical Society held its annual Christmas Party featuring Santa for the children, Alan Lush entertaining at the keyboard in the front parlor, and Joe and Theresa Guidice performing on harp and flute in the back room where Chairwoman Barbara Guidice presided over the punch bowl and the hors d’oeuvres.

And that really just confuses everything.

A Few Notes on Presiding Over the Punch Bowl

William Hogarth, A Midnight Modern Conversation, 1730

March 21st was my maternal grandparents’ wedding anniversary; they were married in 1946 in Silver Spring, Maryland, my grandmother’s hometown. As a child I loved to pore over the Silver Spring Standard wedding notice in her scrapbook, which contained lines like, “The church was massed with spring blossoms, a fitting setting for the exquisite beauty of the bride herself, in her ethereal white marquisette gown and flowing lace.” (“TERRIBLE write-up,” my grandmother had written in the margins.)

What struck me lately, as I reread the notice yet again, was the range of tasks assigned to the wedding guests. The maid of honor and best man were duly accounted for, but there was also this: “Mrs. Elizabeth McLean presided at the coffee urn and Miss Mary Roberts at the punch bowl.”

A cursory Internet search shows that this was indeed a thing: if you Google “Presided over punch bowl” or “presided over coffee urn,” you’ll come across a raft of vintage wedding and party notices, all of which describe the dispensing of beverages. What I really wanted to know is, was this duty—which sounds dull, potentially messy, and interminable—considered an honor, or was it a sort of booby prize for extra relatives? “Presides” has a regal ring, but the task itself sounds akin to light drudgery.

One also wonders whether the punch-bowl president was supposed to be a sort of killjoy: one recollection of a Savannah New Year’s party mentions that, as a rule, “One of the hostess’ best friends, dressed in a hoop-skirted gown, presided over the punch bowl, guarding it carefully in case a jokester decided to drop in a bit of bourbon.” Another write-up references “the three married women who presided over the punch bowl,” suggesting that this was no job for an untried virgin.

The most recent iteration of Emily Post, in her section on Receiving Lines, has only this to say: “When the receiving line is held at the reception site, have a waiter offer a variety of drinks—juice, punch, sparking or still water, Champagne—to those waiting in line. Be sure to have a small table where guests can place their drinks before going through the line.” Clearly, this is not a position that enjoys the respect it was once due, at least in some places. But think about it: who else “presides” at a wedding? The officiant, that’s who. The punch-bowl and coffee-urn women are, in their way, second in importance only to the law and God.

Here is the most unlikely thing I found, from a 2001 edition of New Jersey’s Amityville Record:

On Sunday, December 10, the Amityville Historical Society held its annual Christmas Party featuring Santa for the children, Alan Lush entertaining at the keyboard in the front parlor, and Joe and Theresa Guidice performing on harp and flute in the back room where Chairwoman Barbara Guidice presided over the punch bowl and the hors d’oeuvres.

And that really just confuses everything.

I Heart Suburbia

The light verse of Phyllis McGinley, born on this day in 1905.

Friends Over for Tennis, Douglas Crockwell, 1949

McGinley was on the cover of Time; her work appeared in the Atlantic and The New Yorker. And yet this scathing, passing reference is the only mention she receives in our entire archive. How can we have passed over such a popular and laureled poet?

Chalk it up to, let’s say, a difference in sensibility. As Ginia Bellafante put it a few years ago in an excellent essay for the Times, McGinley wrote “reverentially of lush lawns and country-club Sundays … [she] is almost entirely forgotten today, and while her anonymity is attributable in part to the disappearance of light verse, it seems equally a function of our refusal to believe that anyone living on the manicured fringes of a major American city in the middle of the 20th century might have been genuinely pleased to be there.”

That’s a much more generous and evenhanded appraisal than Snodgrass’s. But even as I sit here reading McGinley’s work, I share in the refusal to believe. This woman was actually living it up in Larchmont. Can it be true? Her verse is clever and well wrought—it earned praised from no less a luminary than W. H. Auden, who wrote the foreword to one of her collections—but after a few lines, I find my brow reflexively arched. Is it not at least possible that she was pulling one over on us, churning out delightful, perfectly cadenced paeans to the ’burbs while privately guarding a faint flame of Cheeverian ennui?

No, it is not. McGinley genuinely adored the life of a suburban housewife—she had a tumultuous, itinerant childhood, and she relished the stability of married life, the fine china, the deviled eggs, the stand mixer, the quilting bees. Her poems tout convention and pooh-pooh feminism; they sound as if they were made to be read aloud by the president of the PTA on the occasion of an eighth-grade graduation. Here’s a bit from “Ode to the End of Summer”:

Farewell, vacation friendships, sweet but tenuous

Ditto to slacks and shorts,

Farewell, O strange compulsion to be strenuous

Which sends us forth to death on tennis courts.

Farewell, Mosquito, horror of our nights;

Clambakes, iced tea, and transatlantic flights.

And from “Reflections at Dawn”:

I wish I owned a Dior dress

Made to my order out of satin.

I wish I weighed a little less

And could read Latin.

Had perfect pitch or matching pearls,

A better head for street directions,

And seven daughters, all with curls

And fair complexions.

I wish I’d tan instead of burn.

But most, on all the stars that glisten,

I wish at parties I could learn

to sit and listen.

And here I could mount a trenchant critique of the suburbs or trot out a couple of zingers—but what would be the point? The tragicomedy of these poems is how they’ve gone, in the span of a few decades, from prizewinning to self-parodying. Work like McGinley’s is jarringly familiar and yet totally foreign, indicative of how quickly a culture can scorn what it once adored—how an era’s prevailing tastes become passé, or worse, naive. Suburbia has become so inextricably (if deservedly) affiliated with conformity, conservatism, and delusive sameness that it’s impossible to read McGinley with an objective eye, even more than fifty years after her heyday. And as Bellafante notes, light verse, once an arts-and-letters staple, is now extinct. It’s worth considering how and why such a thriving form came to seem so silly—and, for that matter, which one is next on the chopping block. It’s entirely possible, for instance, that quick, five-hundred-word blog posts pegged to poets’ birthdays will not age gracefully.

Fake Locales with Real Visitors, and Other News

The Timberline Lodge, in Mount Hood, Oregon—more often taken for the Overlook Hotel, which it portrayed in 1980’s The Shining. Photo: mthoodterritory.com

It’s World Poetry Day. Take time to remember the dissident poets in your life.

Today in simulacrum news: fictional places that attract real tourists. (The Most Photographed Barn in America is not here, alas, though arguably that’s a real place which was then fictionalized, thus becoming more real.)

“The national discussion of grammar and language is stuck in half-remembered dictates and daft shibboleths.”

“I was curious about changes in the Mark Twain Boyhood Home and Museum, which I hadn’t visited for two decades … the room was silent save for a single whispered comment I heard from one museumgoer to another, ‘I didn’t know he was so poor.’” Mark Twain’s deep, abiding history with the Mississippi River.

International Corporate Translation Goof of the Day: “Of all the available Chinese translations for ‘oracle’ as the name of one of the world’s largest and most advanced computer technology corporations, jiǎgǔwén 甲骨文 (‘oracle bone script’) is probably the least appropriate.”

March 20, 2014

The Equinox Reality Check

Image via Giphy

Feel that? It’s the vernal caress of the equinox, its breeze seeming to whisper, There, there, your misery will soon fade, spring is here, the world is in bloom, cast off your gloves and scarves, put down the whiskey, lower your firearm, you’ve made it out alive.

In 1968, The Paris Review published a poem for just this occasion, kind of. Diane di Prima’s “Song for Spring Equinox” does indeed celebrate the first day of spring—it begins, “It is the first day of spring, the children are singing”—but it also boldly admits, and indeed seems to bask in, a truth most of us are trying to ignore: things are still really brown outside. As di Prima puts it, “nothing is blooming / nothing seems to bloom much around farms, just hayfields and corn / farms are too pragmatic.”

Well. Bummer. It’s probably no coincidence that this poem appeared in a fall issue, not a spring one.

Still, you can and should read the entire poem, which unfolds in a kind of free-associative frolic, touching on crossword puzzles, hydrangeas, and pioneers. Consider it a corrective, not a rebuke; any poem that includes the line “will I hate the Shetland pony we are buying” won’t harsh your springtime buzz too much.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers