The Paris Review's Blog, page 725

March 20, 2014

Thomas Ken’s “Old Hundredth”

The New England Butt’ry Shelf Cookbook, written in 1969 by Mary Mason Campbell, is one of the most perfect works of nostalgia ever published. Ms. Campbell runs through the year’s calendar, remembering her New Hampshire family’s idyllic holiday celebrations: Fourth of July picnics on the river, Valentine’s Day children’s parties, Hallowe’en revels, all accompanied by lots of homemade food and liberally supplemented with stores from the eponymous buttery, or pantry.

As a child, I was understandably obsessed with this book. From the vantage point of my own chaotic household, the order and tradition of the year Campbell described seemed indescribably appealing. For some reason, one vignette made a particular impression on me. The author describes how, every Thanksgiving, her grandfather (who had a good baritone) would summon all the guests to table by booming out “The Doxology.”

At the time, I didn’t know what “The Doxology” was. Lacking Internet, I asked my mom, who explained it was an alternate name for “Old Hundredth,” one of the most canonical of traditional hymns. And then I realized that I sort of knew it—we sang a version of it, with Pete Seeger’s ecumenical lyrics, at my progressive elementary school. (Although we omitted the lyrics “Between the white, black, red, and brown,” because by the mideighties that was considered racist.)

One Thanksgiving—I was probably about ten—I decided to conjure a little of the magic of Campbell’s book. We might not have had the pineapple-pattern damask, the incomparable flavor of the tin-roaster turkey (which everyone would turn as they passed), or the cornucopian relish tray. But damned if I couldn’t play “The Doxology” when it was time to eat.

I sat down at the piano, opened the hymnal, and, with great gravitas, played a halting and terrible version of #134. No one seemed very impressed. Certainly no one took this as a signal to file reverently into the dining room. In point of fact, no one noticed.

“DINNER!” my mother yelled. Everyone charged out.

Praise God, from Whom all blessings flow;

Praise Him, all creatures here below;

Praise Him above, ye heavenly host;

Praise Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.

Bull City Redux

Kate Joyce, Pressbox, April 2013.

On view as part of the New York Public Library’s recent exhibition “Play Things”—on prints and photographs that deal in some way with games and recreation—was a series of nine baseball cards made in 1975 by artist Mike Mandel. Originally packaged with sticks of Topps gum, the cards feature some heavy hitters at bat, pitching, and fielding: Joel Meyerowitz (2), who prefers Kodachrome film; Aaron Siskind (66), whose favorite developer is Mircodol-X; and Betty Hahn (54), who likes to shoot with a Nikon. Oh, didn’t I mention—they’re photographer trading cards.

Mandel made them (there are 134 in all) in order to satirize, and frustrate, the commercial art market: the only way to collect all the cards is by making trades. Mandel’s link between photography and baseball is apt for another reason: baseball, a famously uneventful sport, is a game in which players and fans spend a lot of time observing—each other, the stands, the field, the sky—and what is photography if not the art of observing?

My appreciation of this visual aspect of baseball is fairly new. It was exactly a year ago that Sam Stephenson wrote to ask whether we might collaborate on a series of blog posts documenting the 2013 season at the Durham Bulls Athletic Park. Initially, I demurred. I’ve never had much interest in baseball, unless you count a short-lived crush on Chuck Knoblauch in the early aughts. But Sam also promised images by a roster of photographers, and I was won over.

Bull City Summer ran on this site for six months and reported not only on the team’s players and manager but, more significantly, on the field, the fans, and the idiosyncratic atmosphere of minor-league baseball. When Adam Sobsey introduced the series last April, he wrote that “to the unpracticed eye, the mostly static conditions on the field can seem slack or desultory, but in fact the opposite is true: the game conceals in its apparent inactivity (even woolgathering) maximum tension, precision, aspiration, tactics, worry, and grudge.” The action is in the details, and Sobsey and other writers from the series—Sam, Michael Croley, David Henry, and Howard Craft—spent the summer digging into the rote boredom and finding life within the long stretches of empty innings.

But what of the photographs? What do pictures of minor-league woolgathering look like? In many ways, they don’t look much like baseball—or at least not the baseball we’re using to seeing in still images. There are no shots of players running bases, of pitches just as the ball has left the mound, or of the crack of bats. The moments captured here are small and transitory but nonetheless make up a season at the Durham Bulls ballpark.

Alex Soth looked to the green wilds of the stadium, where solitary outfielders hold their positions and wait; Frank Hunter looked to the skies over the field, where the stadium lights met gathering thunderheads. Leah Sobsey studied individuals by composing formal tintype portraits of Bulls staff. For Kate Joyce, the details of a game were often literal: the wrung torsos of players in batting practice, a pitcher’s fingers lightly positioned on the ball, the myriad bubblegum-wrapper darts tossed by players into the grass. But in the minors, the accounting of a game doesn’t only take place in the space of the field but also among the social community in the stands: the fans and workers who provide a different kind of theater during the slow procession of innings. So we have Hunter’s shot of fans shielding their eyes from the late afternoon sun, Alex Harris’s portraits of attendees as they enter the stadium and Sobsey’s as they mill on the concourse, Soth’s enigmatic concessions workers, and Joyce’s playful typology of cups containing melted slushies and watered-down cokes.

Kate Joyce’s typologies are some of my favorite photographs. She took some ninety thousand pictures over roughly a thousand hours in preparing for and realizing the BCS project. But these grouped photographs—the lawn darts, the abandoned concessions, the white smudges made by balls hitting the Blue Monster in left field—are the clearest indication that she, like me, was trying to make sense of a game that is as much about ritual as it is about rules. These accumulations make up a pattern, a vocabulary, through which Joyce can begin to understand the larger language.

On view this spring and summer, in Raleigh, North Carolina, are two exhibitions of photography and video work from the Bull City Summer project, by ten artists—Kate Joyce, Alec Soth, Frank Hunter, Leah Sobsey, Hank Willis Thomas, Hiroshi Watanabe, Alex Harris, Elizabeth Matheson, Ivan Weiss, and Jeff Whetstone. You can work on your own art of observation with the slide show of selected images below. And remember that baseball, to quote Leonard Zelig, “doesn’t have to mean anything, it’s just beautiful to watch.”

“Bull City Summer” is on view at the North Carolina Museum of Art, in Raleigh, through August 31. Another exhibition, at the Contemporary Art Museum–Raleigh, opens May 15. The book Bull City Summer: A Season at the Ballpark will be published by Daylight Books in April.

Kate Joyce, Impact of a Ball and the Outfield Wall, Part 2, 2013.

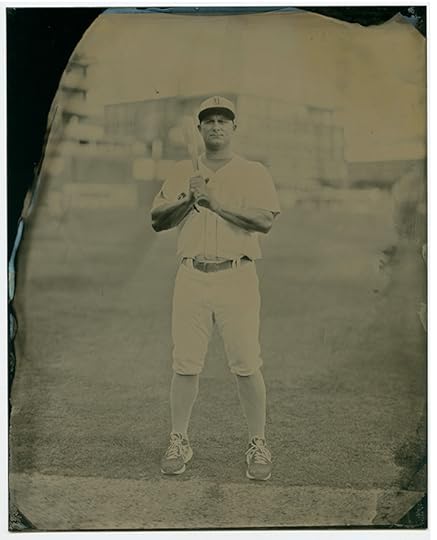

Leah Sobsey/Tim Telkamp, Groundskeepers (L–R: Scott Strickland, head groundskeeper; Connor Moser, Bill James), tintype.

Alex Harris, Outside the Ballpark #4, Durham, North Carolina, May 2013.

Leah Sobsey.

Alec Soth, Center Field #3, 2013.

Frank Hunter, Light in a Summer Night #4, 2013.

Leah Sobsey.

Frank Hunter, Man with a hotdog.

Kate Joyce, Lawn Darts Made from Bubblegum Wrappers and the Field of Play, 2013

Leah Sobsey/Tim Telkamp, Vince Belnome, tintype.

Leah Sobsey.

Frank Hunter, Light in a Summer Night #8, 2013.

Alex Harris, Outside the Ballpark #3, Durham, North Carolina, May 2013.

Alex Soth, Jamal, 2013.

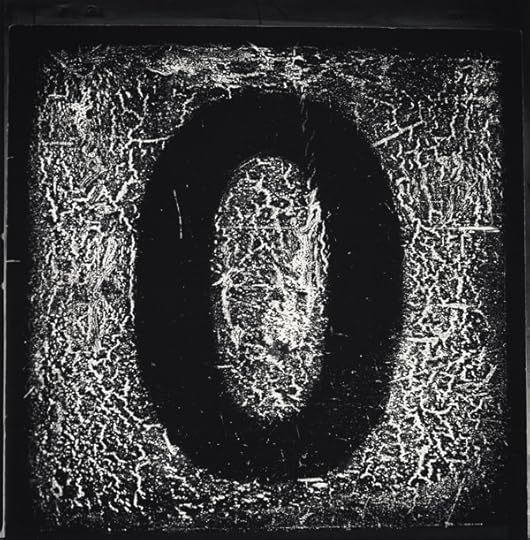

Hiroshi Watanabe, Zero, 2013.

Ovid’s Ancient Beauty Elixirs

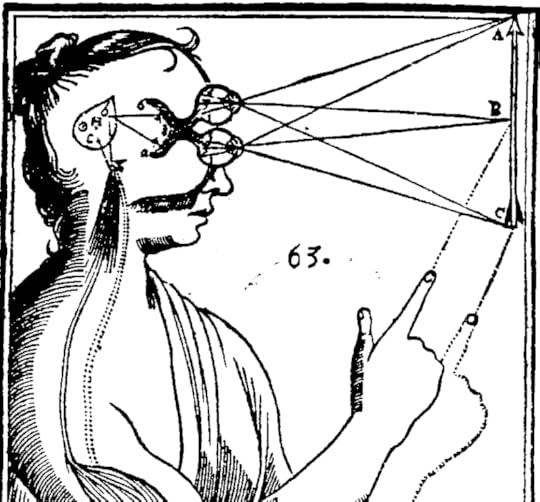

The man knew his makeup. Ovid, in a woodcut from the Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493.

The rumors are true: it’s Publius Ovidius Naso’s 2,057th birthday. You can score some points with the classicists in your life by mentioning this in casual conversation, especially if you toss in a reference to the Metamorphoses. (“I was just thinking of Pyramus and Thisbe,” you might say, wiping a tear from your cheek as you gaze wanly upon a crack in the wall.) And if you’re wooing a classicist, or wooing anyone, really, be sure to heed the advice in Ovid’s Ars Amatoria, his instructional elegy on romance—its efficacy has not been diminished by the passage of millennia. Mental Floss even has eleven dating tips from the poet himself. They include “the theatre is a great place to pick up girls,” “do not make a parade of your nocturnal exploits,” and “pay your lovers in poetry.”

But I write today with a more urgent, and more profitable, message. Even if readers still (occasionally) reach for the Metamorphoses or Ars Amatoria, there’s a massive blind spot in our modern view of Ovid. We’ve all but forgotten the man’s gifts as a beautician.

Somewhere between 1 BC and 8 AD, Ovid wrote Medicamina Faciei Femineae, known variously as The Art of Beauty or—my personal preference—Cosmetics for the Female Face. Though only about one-hundred lines survive, they include step-by-step instructions for making your own ancient Roman cosmetics, and believe you me, these concoctions are unlike any beauty products on the market right now. True, they include egg whites, frankincense, and honey, all of which are still found in cosmetics today—but Ovid also calls for such boutique ingredients as hart’s-horn, thural seed, and “the froth of which the Halcyon builds / Her floating nest.” (Presumably available at your nearest specialty grocer.)

At a time when all-natural, organic, locally sourced, “heritage” products are de rigueur—when quinoa is trumpeted as an ancient super-grain and anti-aging creams boast chestnut and citrus extracts—it seems to me that our nation’s leading cosmetics manufacturers have a clear mission: to reproduce Ovid’s makeup as exactingly as possible, and to market the hell out of it. With their poetic lineage and assertively pure ingredients, Ovid® brand foundations, balms, creams, lotions, ointments, and emollients could easily capture the hearts, and dollars, of upmarket consumers and vain PhDs. Procter & Gamble, Unilever, Johnson & Johnson: I’m looking at you. And I’m happy to offer, for a reasonable fee, my services as an Ovid® consultant and brand ambassador. Let’s talk. As a token of good faith, I include here Ovid’s proprietary formulas.

Vetches, and beaten barley, let ‘em take,

And with the whites of eggs a mixture make;

Then dry the precious paste with sun and wind

And into powder very gently grind.

Get hart’s-horn next (but let it be the first

That creature sheds), and beat it well to dust.

Six pound in all; then mix and sift ‘em well,

And think the while how fond Narcissus fell;

Six roots to you that pensive flower must yield

To mingle with the rest, well bruis'd and cleanly pill’d.

Two ounces next of gum, and thural seed,

That for the gracious gods does incense breed,

And let a double share of honey last succeed.

With this whatever damsel paints her face,

Will need no flattering glass to show a grace.

Nor fear to break the lupine shell in vain,

Take out the seeds, then close it up again,

But do it quick, and grind both shell and grain.

Six pounds of each; take finest ceruse next,

With fleur-de-lis, and snow of nitre mix’d:

These let some brawny beater strongly pound

That makes the mortar with loud strokes resound,

Till just an ounce the composition’s found.

Add next the froth of which the Halcyon builds

Her floating nest: a precious balm it yields,

That clears the face from freckles in a trice:

Of this about three ounces may suffice.

But ere you use it, rob the lab’ring bee,

To fix the mass, and make the parts agree.

Then add your nitre, but with special care,

And take of frankincense an equal share:

Though frankincense the angry gods appease,

We must not waste it all their luxury to please.

To this put a small quantity of gum,

With so much myrrh as may the rest perfume.

Let these, well beat, be through a searce refin’d,

And see you keep the honey ail behind.

A handful too of well dry’d rose-leaves take,

With frankincense and sal ammoniac;

Of frankincense a double portion use;

Then into these the oil of malt infuse.

Thus in short time a rosy blush will grace,

And with a thousand charms supply the face;

Some too, in water, leaves of poppies bruise,

And spread upon their cheeks the purple juice.

The Self Resides in the Chest, and Other News

Descartes thought the seat of the soul was in the pineal gland. He was so wrong.

“Revenge should have no bounds,” the Bard wrote in Hamlet, and one man, at least, vigorously agrees: when a graphic designer in Bristol failed to receive the gaming console he’d bought online, he sought retribution by sending the scammer the complete works of Shakespeare via text message.

An early photo of Jason Segel portraying David Foster Wallace indicates that Jason Segel does not very much resemble David Foster Wallace.

Where are you? You are in your chest. Researchers “asked ten blindfolded adults to use a metal pointer to motion at ‘themselves.’ Most people indicated their upper torso area … ‘the torso is, so to speak, the great continent of the body, relative to which all other body parts are mere peninsulas. Where the torso goes, the body follows.’”

In a new interview, Ralph Steadman discusses, among other things, his old pet sheep: “It was a mutant sheep, but a local farmer was taking it to slaughter. I adopted her, named her Zeno, or him perhaps—does it really matter? It’s a sheep, after all … I would go to her in the morning for wisdom, for a philosophic message of what to do with the day.”

John Banville’s new novel resurrects Raymond Chandler’s beloved private eye, Philip Marlowe, raising the question: “At what point does a work of supposed literary merit simply become fan fiction?”

March 19, 2014

The First Footage from the Cinematograph

On March 19, 1895, 119 years ago, August and Louis Lumière made the inaugural recording with their newly patented cinematograph, a sixteen-pound camera made to compete with Edison’s nascent kinetoscope. The cinematograph was powered by a hand crank, and it improved on the kinetoscope in that it incorporated a projector, which allowed a large audience to take in its spectacles. (Edison’s machine had only a peephole; maybe he thought moving pictures would appeal exclusively to voyeurs. And maybe they do.) The perforated film reel in a cinematograph was easier to hold in place, which meant it produced sharper, stabler images than had ever been seen.

This first film, La Sortie des usines Lumière à Lyon, features, as its title promises, workers leaving the Lumière factory in Lyon. What’s remarkable to me is how purely documentary this footage is: no one breaks the fourth wall. Even the dog isn’t terribly curious. If I were toiling in a factory all day, about to play a part in the debut of a revolutionary new technology, I would be sure to wave at the camera on my way out.

Trading Places

An illustration from the Betsy-Tacy series.

Repeating compliments to a third party is a bit like giving money: everyone’s glad to get them, but the giving can be awkward.

It was not always so. Time was, the passing on of compliments was so ritualized a part of life that the practice had a name: trade-last. Merriam-Webster’s defines it as “a complimentary remark by a third person that a hearer offers to repeat to the person complimented if he or she will first report a compliment made about the hearer,” and dates the first recorded use of the term to 1891.

No doubt like many other readers, I first discovered the term in Maud Hart Lovelace’s Betsy-Tacy books. To the uninitiated, these nine autobiographical novels follow the career of aspiring writer Betsy Ray from the age of five to twenty-three; the reading level changes to match Betsy’s age (more or less). Thus they begin as children’s books and then, when Betsy reaches high school in 1906, they become what we might nowadays call YA. In the four books that take place around Deep Valley High School, Betsy and her beloved “Crowd” frequently exchange “trade-lasts,” or TLs, as they are known. It is customary, when given a TL, to return the favor at some point.

The practice ends up playing a key part in one of the last books, Betsy and the Great World. Having quarreled with her love interest, Joe Willard, Betsy breaks the ice in a letter by repeating a compliment she has heard about his writing. “I have a TL for you, Joe,” she writes, setting the stage for the reconciliation that culminates in the final volume of the series, Betsy’s Wedding.

If you keep your ears open, “TL” can also be found in old movies and the occasional radio show. I don’t know when or why it fell out of fashion; it is an eminently useful and civilized practice that eliminates a lot of social difficulty and encourages the repetition of nice things. How much easier to say, “I have a TL for you,” then “I heard something from someone I wanted to tell you,” or some other inelegant setup. I can’t imagine Betsy could have effected her reconciliation so breezily without the turn of phrase.

I have been singlehandedly trying to bring “TL” back into circulation, but as with any innovation—or reintroduction, I guess—it is uphill work. No one knows what you’re talking about, for one, and explaining the phrase takes way more time than just repeating a compliment (however inelegantly) would. It doesn’t help that, when provoked, I tend to launch into lengthy synopses of the entire Betsy-Tacy series; and making matters worse, the letters TL apparently stand, these days, for toilet, top level, team leader, and true love. Oh, and last, there’s the fact that, when questioned, I have absolutely no idea what trade-last means.

A Philip Roth Bonanza

The birthday boy, looking decidedly more bored than he’d be if he were reading our back issues.

Philip Roth turns eighty-one today. You must be wondering: How can you, little old you, partake of such an historic occasion? Well, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. You could masturbate into a piece of raw liver, à la Alexander Portnoy; you could masturbate on your mistress’s grave, like Mickey Sabbath; or you could masturbate into your beloved’s hair, as David Kepesh does.

Then again, there’s no law saying life must imitate art. If you’re absolutely set on not paying tribute through masturbation, there is one other option: you can peruse our archives, where you’ll find a whole host of work by, about, or otherwise in the orbit of Philip Roth.

There’s “The Conversion of the Jews,” a short story The Paris Review published in 1958, later collected in Goodbye, Columbus:

If one should compare the light of day to the life of man: sunrise to birth; sunset—the dropping down over the edge— to death; then as Ozzie Freedman wiggled through the trapdoor of the synagogue roof—his feet kicking backwards bronco-style at Rabbi Binder’s outstretched arms—at that moment the day was fifty years old. As a rule, fifty or fifty-five reflects accurately the age of late afternoons in November, for it is in that month, during those hours, that one’s awareness of light seems no longer a matter of seeing, but of hearing: light begins clicking away, in fact, as Ozzie locked shut the trapdoor in the rabbi’s face, the sharp click of the bolt into the lock might momentarily have been mistaken for the sound of the vast gray light that had just throbbed through the sky.

And “Epstein,” another story from Goodbye, Columbus:

At the corner luncheonette he bought his own paper and sat alone, drinking coffee and looking out the window beyond which the people walked to church. A pretty young shiksa walked by, holding her white round hat in her hand; she bent over to remove her shoe and shake a pebble from it. Epstein watched her bend, and he spilled some coffee on his shirt front. The girl’s small behind was round as an apple beneath the close-fitting dress. He looked, and then as though he were praying, he struck himself on the chest with his fist, again and again. “What have I done! Oh, God!”

There’s our seminal Art of Fiction interview with Roth, from 1984:

It’s all the art of impersonation, isn’t it? That’s the fundamental novelistic gift … I am a writer writing a book impersonating a writer who wants to be a doctor impersonating a pornographer—who then, to compound the impersonation, to barb the edge, pretends he’s a well-known literary critic. Making fake biography, false history, concocting a half-imaginary existence out of the actual drama of my life is my life. There has to be some pleasure in this job, and that’s it. To go around in disguise. To act a character. To pass oneself off as what one is not. To pretend. The sly and cunning masquerade.

If you’re really looking to party hearty, there’s Roth’s speech at our 2010 Revel; Roth reading a eulogy for his high school teacher, Bob Lowenstein; an account of Roth’s eightieth birthday party last year; and Roth giving invaluable life advice (“quit while you’re ahead”) to a young writer.

It’s more pleasure than you could give yourself, if we dare say so.

“[Subscribe to] The Paris Review.” —Philip Roth

Unhousing

Foreclosed homes as haunted houses.

Photo: Casey Serin

My wife and I began searching for a house in 2008, just as the market was crashing, just as those first waves of foreclosed homes and short sales were hitting the market. Priced out of Los Angeles real estate for so long, we were finally able to afford houses whose prices had been ridiculously inflated only six months earlier. Occasionally we went to those open houses with smiling realtors and bowls of candy set out, where owners had recently landscaped or repainted to enhance value, but we could never seriously consider any of these. The homes that mattered had lock boxes, were abandoned or in the process of being abandoned—the ones that reeked of disrepair and despair.

We spent the summer touring nearly every distressed property in the neighborhoods East of Hollywood: Los Feliz, Silverlake, Echo Park, and Atwater Village—every abandoned or half-abandoned monstrosity and beloved ruin, looking for a home. I still have a hard time articulating the sense of dread and fascination those houses stirred in me. The feeling of moving through these spaces—particularly as we were visiting seven or eight of them in an afternoon—was indescribable. A sense of wrongness pervaded so many of these homes. I’m not superstitious—I don’t believe in spirits or forces or haunted houses—but much of our lexicon in these cases depends on notions of the supernatural; in the end, the only word that seems useful for talking about the houses is unheimlich—a German word, literally “unhomely” or “not of the home,” “unfamiliar.” It’s more idiomatically translated as “uncanny”: a word that Freud plucked and repurposed from the realm of the supernatural.

* * *

Freud’s 1919 essay, “The Uncanny,” is among the stranger of his well-known works. He doesn’t really know where to begin with the uncanny—when it comes to the feeling, he admits, “the present writer must plead guilt to exceptional obtuseness.” One wonders why he’s bothering with the subject at all. Mostly he wants to contradict Ernst Jentsch, another psychoanalyst, who first attempted to define the uncanny in 1906, thirteen years before Freud’s essay. Jentsch posits the sensation of the uncanny as stemming from a kind of cognitive uncertainty, where one is unclear as to whether an object or figure or a person is inanimate or somehow alive.

Freud, unconvinced by Jentsch, begins by surveying dictionaries, copying out as many different definitions of uncanny as he can. Much of Freud’s brilliance, one could say, was in naming: in strange and uncertain times, Freud defined amorphous feelings and ambiguous moments. So he begins by trying to unearth a word or a definition that might fit this feeling, discarding vague terms like eerie and creepy; what finally catches his attention is the fact that heimlich, in addition to meaning “homey” or “familiar,” can also mean “hidden, locked away.” And so he finally seizes on Friedrich Schelling’s definition for unheimlich: “Uncanny is what one calls everything that was meant to remain secret and hidden, and has come into the open.”

This formulation works for Freud—he is, of course, interested in repression—but it doesn’t work as well for haunted houses. What, after all, is being repressed? Jentsch’s notion, of a confusion between the living and the inanimate, works much better—think of the anthropomorphized façade of The Amityville Horror’s house. With a haunted house, the question is: To what extent is the house itself alive, and to what extent is it inanimate?

But it’s not a house’s consciousness that makes it uncanny—it’s my own consciousness. The question is not which of us is the automaton and which of us sentient, but rather what, if anything, my projections onto an inanimate object mean. Really, it’s the most basic definition of uncanny—unheimlich—“unhomely,” that matters. The haunted house is precisely that which should be homey, should be welcoming, the place one lives inside—a place that has somehow become emptied out of its true function. It is terrifying because it has lost its purpose, yet stubbornly persists. Like a zombie, which is not alive or dead but undead, the haunted house is the thing in between.

* * *

My wife and I walked, zombie-like, through home after home, throughout that stifling summer, into homes that had been closed against the light but bristled with claustrophobic air. We took to nicknaming these places: the Flea House, after whatever it was that bit our realtor; the Burn House, with its charred patches of wall and blackened carpets; Tony’s House, after the name on the novelty license plate still stuck to a bedroom door, a detail particularly creepy amid the otherwise empty gloom of the house, as though Danny Torrance would big-wheel down the hall at any moment.

For the most part, these homes were on regular streets, among other unexceptional homes. It was strange to find them in Los Angeles; the haunted house is usually built outside of some small town, a nightmare in the wilderness that beckons just beyond some tiny hamlet. In Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, as Eleanor Vance makes her way to Hillsdale, Illinois, she’s told not to ask about Hill House: “I am making these directions so detailed,” Dr. Montague writes to her in a letter, “because it is inadvisable to stop in Hillsdale to ask your way. The people there are rude to strangers and openly hostile to anyone inquiring about Hill House.”

It’s a common trope: the unaware traveler and the wary, even hostile townspeople. Why, in all these stories, do the poor townspeople hate the haunted mansion? Well, because they’re poor. They can’t afford to move away, to uproot their families, even after some rich eccentric has unleashed an unspeakable evil just beyond the town limits. “People leave this town,” a Hillsdale resident tells Eleanor, “they don’t come here.” The archetypal haunted house story is often really about class, about the rich who don’t understand the land or the people or the history and blunder into the landscape, attempting to buy their way into a community, blithely oblivious to the locals nearby. The town grows resentful because, by the force of economics, they are imprisoned by the rich and their folly—haunted by forces beyond their own control.

* * *

These past few years we’ve witnessed an explosion of vocabulary as we struggle to conceptualize a new and terrifying time. Terms like distressed mortgages, toxic assets, underwater, along with repurposed words like ghost and zombie. A ghost loan, for example, involves a mortgage fraud scheme, where a 100 percent financed loan is inflated at closing, the buyer and seller in collusion to defraud the lender; in 2009, an ex-Labour MP was suspended after claiming a £16,000 “ghost mortgage” that never existed.

Dean Maki, managing director and chief economist at Barclay’s Capital, refers to underwater mortgages as zombie mortgages: home loans worth more than the underlying value of the house. Zombie foreclosures, meanwhile, are foreclosures originally done by careless foreclosure mills and dismissed, in places where a court is involved, without prejudice. That last part is key: it means that the banks can have a second shot at the foreclosure if they get their act together, and the foreclosure threat rises once again, as it were, from the dead. Zombie debt, on the other hand, involves losses that homeowners assume they’ve already written off. When a bank forecloses on a house and sells it as a loss, it can decide to pursue the homeowner for the difference. And then there are zombie homes, repossessed but unsold properties that bring down the value of the neighborhood, infecting them with the disease of future foreclosures.

We live among the undead. The things that used to have meaning and purpose—not just houses but banks and governments—have been emptied of what they once meant, and yet they remain, haunting us. We are, like the residents of Hillsdale, Illinois, haunted by forces larger than ourselves, imprisoned by the folly of the rich, who have unleashed some unspeakable dread from which we cannot escape.

* * *

That summer, the two of us toured all manner of strange abodes, including those that seemed all but uninhabitable. There were, of course, the hoarding houses: homes we couldn’t enter because of the high stacks of magazines or newspapers, deemed safety hazards. We could only peer in from the windows.

Far more common, though, were the malformed do-it-yourself homes. Los Angeles is a zoning no-man’s land, home to thousands of unpermitted additions and modifications, so that each house on a block of once-identical residences will be different. East Hollywood, particularly in Echo Park and Silver Lake, is home to dozens of bungalows, seven-hundred-square-foot cottages that line the hills, built originally for actors. Over time, extra bedrooms were added, garages converted, crawl spaces enlarged into dens—often without rhyme or reason or any real sense of purpose. So we looked at house after house where the space felt unnervingly wrong—not because of ghosts or murders, but simply because the house had become strange. Living rooms had been built behind existing bedrooms, so an exterior window looked from one room to the next; thousand-square-foot homes somehow contained four or five bedrooms, each one barely more than a closet cut from some once-sane layout; bathrooms sat in the middle of kitchens; bedrooms without windows were built into the side of hills; doors on the second floor opened into empty air. The effect was vertiginous; you walked into a room and felt a sense of unease before you could say why.

It seemed impossible that anyone had lived in these places. I thought again of Shirley Jackson’s description of Hill House:

This house, which seemed somehow to have formed itself, flying together into its own powerful pattern under the hands of its builders, fitting itself into its own construction of lines and angles, reared its great head back against the sky without concession to humanity. It was a house without kindness, never meant to be lived in, not a place fit for people or for love or for hope.

These homes, too, seemed without concession to humanity, but in a sense they were just the opposite: these were not the caprices of rich men whose hubris unleashed a holy terror. Instead, they were the products of dozens of lower-class families trying to make their homes a little bigger, a little more livable—creating unworkable labyrinths out of necessity.

Probably three-fourths of the houses we looked at had been altered in some way, but none of them came close to the Happy Murder Castle. Driving up to it, we could see the faux flagstone that had been painted on some, but not all, of its walls. It was just up the street from an elementary school and may have once doubled as an unlicensed daycare; perhaps the castle aesthetic had looked inviting at one point. The citrus trees on its edges were untended and filled with ripe and rotting fruit, and from those trees rose the back bedroom, complete with plywood crenellations to complete the medieval tower aesthetic. Meanwhile, the front of the house still bore the evidence of its former life as a 1920s bungalow. This was an architectural version of The Fly where two incompatible species had been gratuitously grafted together.

As we walked in, we found another couple on their way out. They looked grimly at us and said, “Hope you brought your mask.” The owners, we learned, had left the taps dripping, so that pools of black mold festered beneath the sinks, but that was hardly the most noticeable thing about the house. It, too, had once been half its current size, and its additions boggled the mind: the only door to the backyard was through a bathroom, and off the kitchen was a room too wide to be a hallway, too small to be a room. This “room,” in turn, led to that back bedroom tower, which amazingly had a painted ceiling with a marginal trompe l’oeil of scarf-draped cherubs blowing trumpets amid wispy clouds. It was hard to imagine how anyone could have made a home here, but we walked through it anyway, drinking in its distorted weirdness, its history measured out in garish juxtapositions. We were about to leave when our realtor noted something we’d overlooked: scrawled in pencil on the living room wall were the words, a murderer lived here.

* * *

The feeling the house gave me stayed for weeks, even after we’d ended our search. The Happy Murder Castle was disquieting, uncanny, possessed of an uneasy sense I’ve rarely felt in any structure; I’ll admit there are times I’m tempted to call it “haunted.” We tell ourselves ghost stories perhaps because we truly believe in the paranormal—or perhaps because we just need a word, a term, a story for that vague feeling that would be too silly to admit otherwise.

After our trip to the Happy Murder Castle, I googled the address along with “murderer,” “killer,” “child molester,” etc., every combination I could think of. I came up with nothing. A realtor has to notify you if a murder has been committed in the house, but not necessarily if a murderer has lived there.

It’s possible, I suppose, that a murderer really did live there. But the truth is likely far more obvious, more quotidian, more biting. These were homeowners who bought at an inflated price before the market crashed and found themselves underwater with a zombie mortgage; they finally lost their home like so many thousands of others. Those penciled words were, like the black mold, their attempt to make their home as unappealing as they could, an albatross around the neck of the bank that had taken it from them. Wherever they are now, their memory lingers in that house—a bitter and spiteful spirit, a sense of melancholy and regret.

In the end, I find myself agreeing more with Freud than with Jentsch after all. The uncanny sense in the haunted houses we walked through—the short sales and foreclosures and distressed properties, the toxic assets and zombie houses—was not borne of a confusion between the living and the inanimate. It was the thing long hidden that had come to light: the thousands of homeowners who’d been promised a future and wagered too much for it.

Colin Dickey is the author of Afterlives of the Saints: Stories from the Ends of Faith and Cranioklepty: Grave Robbing and the Search for Genius.

Youth, Eternal Life, and Other News

Garuda, the “vahana” of Vishnu, returning with a vase of Amrita, a nectar thought to bestow immortality. A drawing by an unknown artist, ca. 1825.

Some writers—the white male ones, mostly—expect to attain immortality through their work. Others simply write about eternal life.

And others still must wait for the afterlife for their work to get the attention it deserves. Walter Benjamin, for instance, was “all but forgotten in the years leading up to his death … his name had been kept alive by a small number of friends and colleagues, the kind of trickle of a readership that hardly suggested he would one day be counted among the most significant and far-ranging critics, essayists, and thinkers of the past 100 years.”

But the ebb and flow of critical reputation is almost a given these days, when we’re always developing provocative new rubrics with which to classify our writers. E.g.: “As novelists spend much of their day watching the grass grow, it is only logical that they can be defined according to their landscaping technique. Thus Donald Antrim is a push-mower novelist, while Rachel Kushner is a ride-mower novelist.”

There were not always “teenagers.” A new documentary examines the peculiar history of the concept, which was “the result and invention of adolescent girls … There is a kind of sexist quality to it as well, a crucifixion of the young female figure.”

As Ukraine becomes the nexus of geopolitics, pickup artists worry about the implications for getting laid. Would EU membership make Ukrainian women more independent, and thus more difficult to seduce? “Kiev’s pussy paradise potential has been permanently damaged … It’s very sad.”

March 18, 2014

Baby Talk

A still from War Babies, 1932.

Since I wish to spare you the disappointment I myself experienced Sunday morning, I’m going to give it to you straight. Despite what the New York Times headline—“A Star Was (Recently) Born: A Play Boldly Casts Babies”—may imply, the current production of A Doll’s House at the Brooklyn Academy of Music does not feature an all-baby ensemble. The baby in question plays Nora’s youngest child, and merely makes a brief cameo, apparently sporting a sheepskin vest.

It’s not that I don’t understand the risks inherent in having a real baby onstage, or the novelty of going for verisimilitude in a role customarily played by a doll. But having had five seconds of imagining baby Ibsen, it was hard to go back. Those five seconds were some of the most glorious of my life.

Of course, there is something of a precedent for baby acting. (And I don’t mean the fact that I came of age in a time when boys in my elementary school still enjoyed quoting zingers from Look Who’s Talking! or Full House.) While the bulk of child actors are not preverbal, a notable exception is the Baby Burlesks of the 1930s, perhaps best known for casting a three-year-old Shirley Temple. The eight one-reelers were a sort of low-rent Our Gang, created by producer Jack Hays. In the words of Wikipedia’s anonymous scribe,

The eight films are satires on major motion pictures, film stars, celebrities, and current events,and are sometimes racist and sexist. Cast members are preschoolers clad in adult costumes on the top and diapers fastened with large safety pins on the bottom.

Here is one, 1932’s “War Babies”:

If you are wondering how they got all these toddlers to act so well, the answer is a lot of manipulation behind parents’ backs: allegedly, the adults in charge would make children who misbehaved sit on blocks of ice. In later years, Temple would describe the films as “a cynical exploitation of our childish innocence” as well as “the best things I ever did.”

My own brush with childhood fame was short-lived. Although I was a relentless little show-off who enjoyed performing a pidgin version of “The Queen of the Night’s Aria” to anyone who would listen—or not—apparently I was not cut out for stardom. I have a strong memory of accompanying my dad, at about three, to a photographer’s studio where he was having an author’s photo taken for a book jacket. In my opinion, I looked fantastic: I had put on my favorite dress, blue with a huge white tie-dyed heart across the tummy.

When we arrived, the photographer—whom I took in instant dislike—asked if I would pose, too. Would I?! But then came the catch: she wanted me to remove my dress and pose in this white silk scarf, which she for some reason referred to as “a garment.” I had never heard the word and instantly hated it. I guess she wanted to arrange it around me like a classical drapery.

Long story short, I threw a tantrum, howling over and over, “I don’t want to wear the garment!” In the end, I “compromised” with her—I don’t know why this seemed like a better idea—by declaring that I would pose in my underpants, but not in the garment. I remember thinking this was an elegant solution. The picture still exists: there I stand, glowering, in my cotton underpants. But dignity, I guess, intact. Had I known any Ibsen, I’m sure I would have quoted it: “I have another duty equally sacred … My duty to myself.”

I’m sure she was just dying to stick me on a huge block of ice.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers