The Paris Review's Blog, page 727

March 14, 2014

What We’re Loving: The Backwoods Bull, the Ballet, the Boot

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

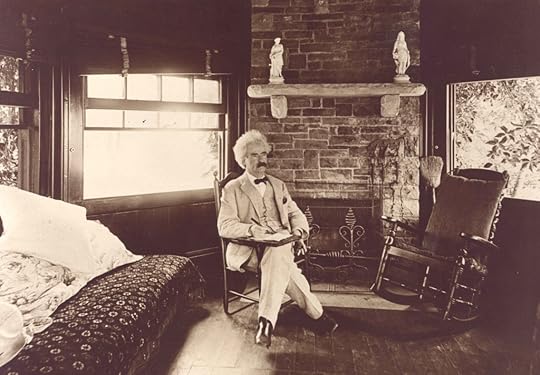

If you are afraid of public speaking, and ever called on to do it, I suggest that you avoid reading “The Backwoods Bull in the Boston China Shop,” from the August 1961 issue of American Heritage Magazine. In this lively article, the dean of American studies, Henry Nash Smith, tells how Mark Twain—perhaps the most popular after-dinner speechmaker of his time—flubbed what was supposed to be the comic relief at an 1877 banquet in honor of John Greenleaf Whittier. Twain made up an anecdote about three grifters passing themselves off as Whittier, Emerson, and Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. Apparently, it bombed. According to Twain’s friend and editor William Dean Howells, “Nobody knew whether to look at the speaker or down at his plate. I chose my plate as the least affliction … [Twain] must have dragged his joke to the climax and left it there, but I cannot say this from any sense of the fact.” Twain was so mortified that he wrote a letter of apology to the three venerable grandees, and they were nice about it, but a week later he told Howells, “I see that it is going to add itself to my list of permanencies—a list of humiliations which extends back to when I was seven years old and keeps persecuting me regardless of my repentancies.” Thirty years later he was still trying to decide exactly how bad the speech had been, even reading it aloud to gauge its offensiveness. I am indebted—if that’s the word—to Sadie Stein and her father for digging up this historical gem. It is the stuff of nightmares. —Lorin Stein

My decision to take up ballet at the ripe old age of thirty-one (572 in ballet years) is not without its challenges. The parts of my body that should be loose are tight, and the places that should be firm wobble; if I land one pirouette out of ten it’s a victory. I’m grateful, then, for Eliza Gaynor Minden’s The Ballet Companion, which not only visually breaks down basic steps (with a blessed glossary of all that French), but gives pointers on class etiquette and attire. Gaynor Minden also writes beautifully about the history of ballet (forget the tutu—bring on the seventeenth-century six-foot hoop skirt!), as well as provides a detailed list of ballets to see before you die. If after reading you still need a reason to pull on those leg warmers, remember: it’s never too late for a bracing dose of humility. —Rachel Abramowitz

A few years ago, two of our uncles took my sister out to a French restaurant in Manhattan. One uncle was pushing her to order the duck confit. The other uncle turned to her and said, “Don’t do it. It’s too rich. He made me do it once and I threw up. You’ll throw up, too.” The first uncle assured her, “You’ll definitely throw up, but you should still get it.” She ordered it and threw up right on schedule. We are a family of eaters, sometimes at any cost. But to A. J. Liebling, perhaps the best eater of the twentieth century, my sister’s fowl adventure would have been child’s play. I’ve spent the past week immersed in his Between Meals: An Appetite for Paris, a memoir of Liebling’s years in the city and, of course, the food he consumed there; he was unapologetically obsessed with eating. He was even lucky enough to have friends who could keep up with him, such as Yves Mirande, the French playwright, who, by Liebling’s account, could tuck away in one meal the contents of a New York–size kitchen. “In the restaurant of the Rue Saint-Augustin, M. Mirande would dazzle his juniors, French and American, by dispatching a lunch of raw Bayonne ham and fresh figs, a hot sausage in crust, spindles of filleted pike in a rich rose sauce Nantua, a leg of lamb larded with anchovies, artichokes on a pedestal of foie gras, and four or five kinds of cheese, with a good bottle of Bordeaux and one of champagne, after which he would call for the Armagnac and remind Madame to have ready for dinner the larks and ortolans she had promised him, with a few langoustes and a turbot—and, of course, a fine civet made from the marcassin, or young wild boar, that the lover of the leading lady in his current production had sent up from his estate in the Sologne. ‘And while I think of it,’ I once heard him say, ‘we haven’t had any woodcock for days, or truffles baked in the ashes.’” —Clare Fentress

You’ve caught me at SXSW—strange to see it without the hashtag—where I’ve spent the past few days overhearing musicians as they talk shop. (“Dude, sick whammy pedal. Is that the new one with true bypass?”) It’s quality eavesdropping, but none of it rivals the dudely conversation on offer in the “Tight Bros from Way Back When” tape, one of the gnarliest cultural documents to emerge from the late eighties. This is a forty-minute taped phone call between two bona-fide California metalheads, Kurt and Derek, that touches on a whole host of topics: police evasion, the occult, Jimmy Page, gravedigging, psychedelics, pyrotechnics, longstanding grudges (“From second grade to now I’ve fought this guy like two hundred times. And I’ve lost three of those times”), and many more. Its first twenty minutes—in which Derek explains how his car got the boot, and how he went to extralegal measures to remove it—make for some of the most memorable storytelling this side of Iron Maiden. “Imagine standing up, right? These bolt cutters were half my height, bro … I’m cruising down the street in broad daylight with these bolt cutters slung over my shoulder, like I’m carrying some skis or somethin’? … I snapped the lock on the boot. It made the gnarliest sound, dude. I summoned the power of all the gods.” The tape has been floating around musical circles for years; at the risk of sounding like Indiana Jones, it belongs in a museum, or at least a top-notch oral history archive. —Dan Piepenbring

I already knew Exact Change for their excellent publishing history—their authors include Leonora Carrington, Guillaume Apollinaire, and Fernando Pessoa—but thanks to our friends at Writers No One Reads, I now know about their new monthly e-zine app, too. The first issue is free, but poke around its archives and you’ll find two additional free issues. Selections include excerpts from Kafka’s notebooks, Emily Dickinson’s envelope poems, and video work by Amy Sillman: all short, and thus perfect for your morning commute. —Justin Alvarez

In 1982, George Lucas founded LucasArts, a sister company to Lucasfilm dedicated to producing video games. From the late eighties through the nineties, the studio created a number of very successful and original adventure games, many of which I grew up watching my brother play; I’ve recently returned to Grim Fandango, released in 1998 and duly renowned for its sharp characterization, its stylish art direction, and, most of all, its genuinely funny writing. Grim Fandango is set in the Land of the Dead, and the story features corrupt government officials and a mob plot to cheat the virtuous out of their just rewards in the afterlife and, caught up in it all, one Manuel “Manny” Calavera, a travel agent and skeleton-in-love, who, in trying to rescue one wronged soul, may find redemption himself. It’s full of charming and clever ideas—for instance, folks in the afterlife aren’t shot but “sprouted”; plants take root in their skeletons, “leaving you nothing but a patch of wild flowers on the ground swarming with butterflies”—and is wonderful to look at even sixteen years on, with a visual style that incorporates Mexican iconography (characters are calaca figures), Art Deco, and an atmosphere distilled from fifties film noir, especially The Maltese Falcon, Casablanca, and Double Indemnity. The dialogue is wry and funny, and the characters richly realized. There are some technical hurdles involved in getting it running on a modern computer, but I urge you, if you can, to discover it for yourself. —Tucker Morgan

Because I’m getting impatient waiting for Ann Goldstein to translate the final installment of Elena Ferrante’s Neopolitan trilogy, I’ve been reading through the rest of Ferrante’s work available in English. Apart from the first two trilogy installments, My Brilliant Friend and Story of a New Name, we Anglophone readers have Troubling Love, Days of Abandonment, and The Lost Daughter available to us. None of these are as disconcertingly excellent as the trilogy, but that might just be because the trilogy sets an impossible standard. The Days of Abandonment, in particular, is a great example of the terrifying and violent portrayal of domesticity and interior life that Ferrante is so good at. —Anna Heyward

Exploding in Sound is a small record label that puts out noisy music. Among the bands on their roster are Krill, fronted by a Jonah who wails like he’s caught behind baleen; Porches., with a crooner who seems to have strayed to some lonely bog; and Pile, whose piano accompanies a balletic barroom brawl. All are adept, ambitious, and something else live. —Zack Newick

“I’ve Lived Very Freely”

Getting to know Mavis Gallant.

A still from Paris Stories: The Writing of Mavis Gallant.

The first of a few unforgettable times I saw Mavis Gallant was in 2004 in Paris. She was eighty-two and had agreed to meet me for an interview at the Café Dome in the Boulevard Montparnasse, around the corner from the apartment where she had been living for decades. When I arrived at the old fashion “terrasse” of the Dome, framed by heavy red curtains, I found Gallant already sitting at the small table where we were to order our tea. I later discovered she must have arrived early on purpose so that I wouldn’t see her walk in—her spine was bent by osteoporosis, and the condition was most evident when she was walking. She was small and smartly dressed in a purple sweater and a checkered skirt, her hair dark red, her eyes lively with multiple shades of green. The first thing she said was: “Don’t ask me how I write. I wrote an introduction to this volume to avoid discussing such nonsense.” The volume was an Italian edition of her work that included some of her most memorable short stories, such as “The Moslem Wife” and “The Remission.”

“Very well,” I said, taking her challenging attitude as an invitation to play. “What would you like to talk about? Men?” She gave me a scornful but not unfriendly look.

“That would certainly be a better choice,” she answered, not meaning it at all. But it was a start, and I was determined to put both of us at ease by being relaxed and polite. I asked her about her husband, John Gallant, to whom she’d been married before the war. “When he came back from fighting, I told him: I want to go to Europe. And he said: I just returned from there, it’s the last place I want to go back to. So the marriage was over. But for the rest of his life he took pride in seeing himself in most of my male protagonists. And it was never true!”

She went on: “It happened the day I sold my first story to The New Yorker. I moved to Paris with a check for six-hundred dollars in my pocket. It was 1950. I was twenty-eight. And I never remarried.” She gave me a glance. “To men I never asked: do you love me? This is what wives asked—I knew it from the men. I’d rather ask: est-ce que vous êtes discret?” Then she added, in case I hadn’t gotten it: “I’ve lived very freely.”

She lived so freely—supporting herself by selling more than a hundred short stories to The New Yorker since 1951, plus publishing various collections and two novels—that she accepted whatever price she had to pay for it. “For me, money meant earning enough to buy myself the freedom to live the way I wanted and where I wanted. Some days it was meat and butter, some others it wasn’t even butter.” Her stubborn quest for independence meant, among other things, exiling herself for sixty years in a city where to this day her name is mostly unknown to readers, with the exception of some devoted and highly educated friends of hers—it seemed to me a harsh choice. “French culture is in terrible decline, have you noticed?” she said, stirring her tea in the white and blue cup of the Dome. “When I arrived here after the war, everything was filthy and shabby, but the last of the taxi drivers spoke like a poet. How I admired that!”

Hoping to hear her expand on her early life, I asked about Canada, where she’d been born. “It was provincial and depressed, most men were at war, and those who’d stayed weren’t happy to make women like me work. I didn’t go to college and became a journalist at the Montreal Standard. I interviewed Jean-Paul Sartre. He was surrounded by a crowd of morons who asked him the stupidest questions. When everybody left, I stayed on to talk with him and he treated me as an equal. Try and imagine what it meant for a girl in her early twenties!”

She was immune to flattery and intolerant of stupidity, but she was also immensely curious, and willing to find out if you were worth her time. I succeeded, eventually, in persuading her to discuss her childhood. “They fuck you up, your mum and dad: you know Larkin’s lines, don’t you?” she said. “When I was four, my mother took me to a convent and left me there without any explanation. I was wearing my best dress, a beautiful blue dress. The mother superior said: you won’t be allowed to keep that dress here. Then my mother left and didn’t come back.” She gave me a defiant look. “Don’t write that I cried, because I don’t remember crying. Even if I must have.”

Her father, whom she had loved, died when she was ten; she found out only three years later, from a family friend. Her mother remarried someone who sexually harassed her after she turned fourteen. She changed schools seventeen times, for no other reason than that her mother was crazy, and that Mavis had no desire to go home to her and her husband, anyway. Again and again she said how much being able to live by herself had meant to her.

“Do you mind if I tell you something personal?” I asked, pouring more tea in our cups. She nodded, alive with curiosity. “I married someone who was sent away to boarding school at a very early age, too, never to come back to his family. Years later, when we separated, his mother called me on the phone in a state of shock. All she said was: ‘Is it true?’ Meaning the separation. And then: ‘We should have never sent him to boarding school!’”

We both burst out laughing. “So you know!” Mavis cried. Of course I knew. I knew her life had been trapped in the contradiction between longing for the family she had been deprived of as a child, and fleeing as an adult the possibility of enjoying one of her own.

We kept in touch after that first interview, though not very often. Then one day I called her and she told me that the “wicked nurse” who was taking care of her insulin shots (she suffered from diabetes) had abandoned her “on purpose” on New Year’s Eve; she’d fallen into a coma, alone, on the floor of her apartment, for two days. The recovery in the hospital had been hell, she said; her voice was extremely animated and she sounded uncharacteristically terrified. I tried to console her telling her that an Italian translation of one of her books had been a great success—which was true. This seemed to stupefy and please her at the same time. “Really?” she kept repeating, her voice suddenly girlish.

By the time I saw her again I had moved to Paris myself. This was in 2008; we spent another afternoon at the Café Dome drinking tea and remembering friends and enemies. She loved Mordecai Richler, even if he affected that “talking about literature was for women.” And she loathed Simone de Beauvoir who, when they met, “was drunk and behaved like a royal idiot.”

Then she was in the hospital again, and I visited her with my friend Mariarosa Bricci, her Italian editor. We found her sharing a room with a very old lady who seemed to have turned to stone. “See this lady?” Mavis said when the conversation fell to French anti-Semitism. “She doesn’t talk, but if she could, she would probably complain about the Jewish lady in the room across the corridor.” I told Mavis it was strange she mentioned this, because I’d just read a passage in Edmund Wilson’s journals in which he recalled meeting her in the Paris of the sixties. He described her as “good looking—dark—and enormously clever and amusing to talk to,” adding that she might as well have been Jewish, even if she said she wasn’t. In her humiliated condition as a geriatric hospital patient, Mavis rejoiced at Wilson’s compliment, and then dismissed him as “a very a pompous man.”

Her deep friendship with William Maxwell came up. “What I liked in him as an editor was the fact that he was a famous writer but never in competition with other writers. And this is pure gold, pure kindness. He encouraged me enormously. For years after his death I kept cutting articles I thought could interest him … ” I thought it intriguing that she could speak about the past with such warmth, and still not mourn it.

“Do you realize she doesn’t need anything—no children, no family—that she contents herself with her intelligence?” Mariarosa said while we were leaving the hospital. It certainly seemed that way, but I wasn’t so sure.

The next time I paid Mavis a visit at Paris’s Hôpital Broca, where she would be confined for nine months, one crisis following another, I found her waiting for me sitting on the bed, with her bandaged legs dangling from its edge, her hair grown longer and half white. She felt rotten, she said with a furious look. “I can’t take it anymore. I want to go home.” She was outraged at her doctors, who wouldn’t let her go unless she accepted to take someone to live with her at home.

“I don’t need any help! I’m perfectly capable of living alone!” she cried. “The French health system is a totalitarian state! In any case, I feel very well,” she lied. “I’m even trying to put on a little weight to impress them. But I’m not fat, am I? Tell me I don’t look fat … ” She must have weighed about ninety pounds.

Eventually, before the summer, she did manage go home. And I stopped visiting her, both because her mind had started showing signs of weakness, and because I had begun writing about her for a book of mine, and I didn’t want to pry. But her friend and agent, Steven Barclay, who took upon himself the task of editing Mavis’s journals with her almost every day, kept me informed, and so did our mutual friend Odile Hellier, the former bookseller of The Village Voice bookstore, where Gallant had read many times.

Both Steven and Odile, of course, were at Mavis’s funeral in the Montparnasse cemetery on February 22. It was a sober affair. About fifty people, white and yellow roses, poems and writings read by friends, and the joyful surprise of a bright blue sky after some early morning rain. We were leaving the graveyard in small groups, hoping to go drink something warm, when I found myself thinking of a funny episode Mavis had once relayed to me. It had happened at the funeral of the Polish poet Alexander Wat, who committed suicide in 1967. While the coffin was carried away from his apartment and the widow was following in tears, Max Wat, the poet’s brother, had turned to Mavis and asked her: “Have you ever been to a Jewish restaurant? Because, if you haven’t, I’d like to take you to a place in the Rue des Rosiers … ” She was so appalled that he had chosen such a tragic moment to make a pass at her that she answered “Yes! I’ll accept.”

As I was amusing myself with this recollection of Mavis’s sense of humor and sex appeal, I shook hands with the writer Terry Tempest Williams, who had come to Paris from Utah to give a reading. “You know, the oddest thing happened to me last night,” she told me with pleasant familiarity while we were standing in the sun near the marble grave covered in roses. “I got myself locked into the bathroom of my hotel. For two hours! I had just taken a bath and I didn’t know what to do. So I had no choice but to open the bathroom window and lean out naked to my waist, to call for the attention of the only person in the street, a Frenchmen smoking a cigarette, who looked up at me and couldn’t help laughing while I begged him to call the concierge. It was like an act out of an opera,” she said. And I thought, here is what I’ve been looking for. One last perfect Mavis moment.

Livia Manera Sambuy is an Italian literary journalist and the author of the PBS documentary film “Philip Roth, Unmasked.” The piece on Gallant is taken from a book of “personal” portraits of writers to be published in Italy in 2015.

The Savage

The last of five vignettes.

Postcard of Zola, 1899.

I was teaching a class which I believe was called “Dramatic Theory” but which, more accurately, if more dauntingly, might have been called “On the Nature of Group Perception,” the study in which the dramatist is actually engaged.

The university had engaged me to show up two days each year for four years. In the second year of our compact I made a pre-appearance request of the English or dramatic department or whomever I was to traipse in under the auspices of.

I suggested they, if they wished, were free to judge the applicants for the limited space in the class according to grades, entrance quizzes, or any other criteria, if they, on determining the lucky winners, would then disqualify them, and assign the spaces at random to anyone else at all.

“Or just give me the ne’er-do-wells,” I asked.

I was saddened, but not surprised, to find, on my arrival, that the university had taken my request as a witticism, and chose for admittance only those students with high grade averages and correct demeanors.

Anyone with sufficient patience to sit through English and drama classes in hope of transmuting their attendance into knowledge or employment in the arts has a great gift. The gift, however, whether of courtesy or sedulousness, is a sure sign of a lack of talent, which is never found without zeal and disruption—in short, without love. And who loves being bored? Some may accept it as a notional price for some greater good, but the inspired know there is no acceptable trade for their enthusiasm and their time.

But there the students were, early, and with notebooks open. Being a mountebank, I asked them to close their notebooks, as, if I said something memorable, they would most likely remember it; and, if not, why torture themselves considering it twice?

Some half hour into the class the door opened and a young man came in. He was unapologetic, and, in fact, rather arrogant. He entered removing a full-face motorcycle helmet which he threw onto a side table, then he sat on the table, at ninety degrees to the class.

I remembered the advice of Lord Chesterfield, that the surest test of superior breeding is never to be upset by impertinences. And there he was, seated apart from and above his classmates, perched on the table lounging back against the wall, a ghastly bad portrayal of privileged youth.

I was leading the class in the construction of a screenplay. I’d taken suggestions for protagonist, objective, setting, and so on. I’d asked for a simple situation, and we had determined that the hero was to be threatened by a terrorist.

“A terrorist,” I said. “Good. An Arab terrorist.”

The young man spoke up.

“Why an Arab terrorist?” he said.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I suppose they came to mind as they have just blown up New York.”

“Haven’t they suffered enough?” he asked.

And there he had me. He had taken umbrage on behalf of a group which had just attacked his country, and suggested that their very contemplation as malefactors was inhumane, as they (a) would somehow suffer from my mentioning their group in a class of twelve, and (b) they had “suffered enough.” “Arab terrorists” had suffered enough.

But the class cowed. I saw that the fellow was some sort of campus personage. They were silent, and I was stunned. I do not know how I concluded the hour, but I did. I returned to my hotel, and, the next day, to my home.

One year later I was scheduled to teach my two days at the university. I was coming down with the flu, but went to the airport, and found myself too sick to get on the plane. I returned home to find that some organization had advertised, in the campus newspaper, a rally to determine whether or not I should be allowed back on campus, as I was some sort of racist.

I would say that the young man, his life, and future depredations do not bear more contemplation, except that I think of him often. His had intelligence uncolored by morality. He was not a psychopath, for he lacked even the desire to manipulate. His was merely the face of pure evil.

David Mamet is a stage and film director as well as the author of numerous acclaimed plays, books, and screenplays. His latest book is Three War Stories .

Eudora Welty Knew How to Make a Good Impression, and Other News

Sobriety pays. Portrait of Welty at the National Portrait Gallery; photo by Billy Hathorn, via Wikimedia Commons

Eudora Welty once explained her popularity as a public speaker: “Colleges keep inviting me because I’m so well behaved … I’m always on time, and I don’t get drunk or hole up in a hotel with my lover.”

Stanley Kubrick’s estranged daughter, Vivian, joined the Church of Scientology in 1999; some have argued, compellingly, that Eyes Wide Shut is a requiem for her. (Think about it: that strange, elite sex cult …) Now Vivian has released a series of touching photos that show her growing up on the sets of her father’s films.

“The first official Scrabble Word Showdown … allows players to nominate a new, officially playable word.”

What’s it like being a real private dick in New Yawk City? Neither as fizzy nor as seamy as you’d expect, alas.

“Welcome to the world of bouncing cars and velvet interiors at the Torres Family Empire Lowrider Convention in Los Angeles, California.”

March 13, 2014

Something Mythical

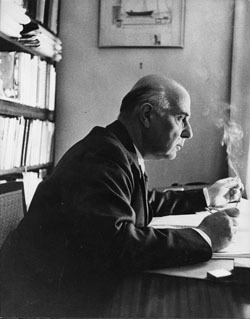

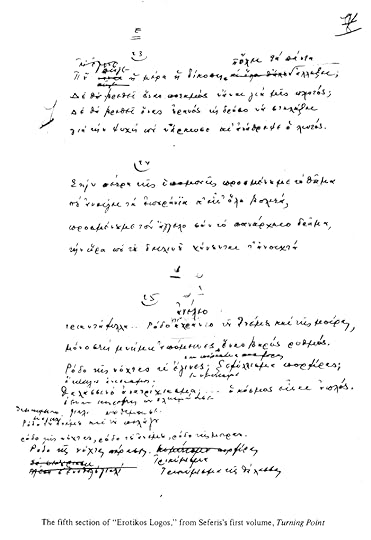

George Seferis was born on this day in 1900.

Seferis in 1957. Photo: The Educational Foundation of the Greek National Bank

SEFERIS

You know, the strange thing about imagery is that a great deal of it is subconscious, and sometimes it appears in a poem, and nobody knows wherefrom this emerged. But it is rooted, I am certain, in the poet’s subconscious life, often of his childhood, and that’s why I think it is decisive for a poet: the childhood that he has lived … When I was a child I discovered somewhere in a corner of a sort of bungalow we had in my grandmother’s garden—at the place where we used to spend our summers—I discovered a compass from a ship which, as I learned afterwards, belonged to my grandfather. And that strange instrument—I think I destroyed it in the end by examining and re-examining it, taking it apart and putting it back together and then taking it apart again—became something mythical for me.

—George Seferis, the Art of Poetry No. 13

Terra Incognita

Remembering Sherwin Nuland, the author of How We Die, who died last week.

Photo: Yale.edu

I attended the Yale School of Medicine when Shep Nuland taught there, and despite our both being surgeons, I know him best in my capacity as a reader. I don’t recall when I first read How We Die—I was just finishing high school when it came out—but I do know that few books I had read so directly and wholly addressed that fundamental fact of existence: all organisms, whether goldfish or grandchild, die. His description of his grandmother’s illness showed me how the personal, medical, and spiritual all intermingled. As a child, Nuland would play a game in which he indented her skin to see how long it took to resume its shape—a part of the aging process that, along with her newfound shortness of breath, showed her “gradual slide into congestive heart failure … the significant decline in the amount of oxygen that aged blood is capable of taking up from the aged tissues of the aged lung.”

But “what was most evident,” he continued, “was the slow drawing away from life… By the time Bubbeh stopped praying, she had stopped virtually everything else as well.” With her fatal stroke, Shep Nuland remembers Browne’s Religio Medici: “With what strife and pains we come into the world we know not, but ’tis commonly no easy matter to get out of it.”

I studied literature at Stanford, and later history of medicine at Cambridge, to better understand the particularities of death, which still seemed unknowable to me—and yet vivid descriptions like Nuland’s convinced me that such things can only be known face to face. How We Die brought me into medicine to bear witness, as Shep Nuland had done, to the twinned mysteries of death, its experiential and biological manifestations: at once deeply personal and utterly impersonal.

I like to think of Nuland, in the opening chapters of How We Die, as a young medical student, alone with a patient whose heart had stopped. In an act of desperation, he cut open the patient’s chest and tried to pump the patient’s heart manually, to literally squeeze the life back into him. The patient died, and Shep was found by the intern, his supervisor, covered in blood and failure.

Medical school has changed since Shep’s time, and such a scene is unthinkable now: medical students are barely allowed to touch patients. What has not changed, though, I hope, is the heroic spirit of responsibility amid blood and failure. This is the true image of a doctor. It is not the idealized happy profession in which we always cure diseases and ease suffering, our patients invariably leaving us better than we found them. It is also doctors facing the enormity of patient problems, seeing the crudeness of our tools, and, inevitably, watching our patients die, usually either in agony or under sedation.

I had dinner with Shep Nuland once, along with several other Yale students. It was right after he had given a talk on his battle with depression, his near complete loss of will. “All my major surgical cases,” he said, “I was scheduling them for twelve, one o’clock in the afternoon, because I couldn’t get out of bed before about eleven … I clearly became increasingly depressed until I thought, my God, I can’t work anymore.” He was admitted to a psychiatric hospital, where every treatment failed: “it got so there was a throbbing, there was a ferocious fear in my head. You’ve seen this painting by Edvard Munch, The Scream … Every moment was a scream.” He nearly had a lobotomy but a resident physician convinced the staff to try electroconvulsive therapy, and after twenty cycles, “I’ve never forgotten—I never will forget—standing in the kitchen of the unit … and thinking, ‘I’ve got the strength now to do this.’”

Shep’s books did not make him immune to tragedy, of course—to address suffering so directly is not to become impervious to it. To ward off depressive thoughts, he used a talismanic phrase: “Aw, fuck it.” Not the most literary of phrases, and I suspect there is a lesson in that.

We discussed none of this over dinner. I was too shy to speak a word the entire meal. I was still lost in the nakedness of his story—today I remember the talk primarily for its therapeutic effect. My closest friend from this time had attended the talk with me. She had been suffering from depression for years, alone in a crowd, cold in the warmth of friends, as the truly depressed are. Shep’s frank description of his experience, and my friend’s identification with it, convinced her to seek treatment. She has gone on to live a happy life.

I’m now a neurosurgical resident; I’ve removed scores of brain tumors, and Nuland’s descriptions of cancer often return to me. Cancer took his brother’s life, and, finally, his own, and he describes the disease not just as a body eaten away by monstrous forces, but as a civilization crumbling as it is increasingly overrun by ravenous juveniles: “Cancer cells are fixed at an age where they are still too young to have learned the rules of the society in which they live. As with so many immature individuals of all living kinds, everything they do is excessive and uncoordinated with the needs or constraints of their neighbors … they are reproductive but not productive. As individuals, they victimize a sedate, conforming society.”

What a perfect metaphor! Every time, a brain tumor looks like a young invader. My goal is eradication. Few things are as satisfying as completely excising a tumor, leaving only the glistening appearance of a healthy brain. Yet, in brain cancer, we know the system carries the disease and the reprieve is temporary: the society will likely be overrun.

Almost exactly twenty years after the publication of How We Die, I was diagnosed with lung cancer, and as I looked at images of my own body riddled with cancerous lesions, Shep’s compelling descriptions returned to me. His metaphor has helped me see the cancer as part of me, both literally and figuratively. At times I think of it as a native insurgency—something to be quelled. But every so often, my attitude is more charitable, and I’ll find myself spastic with pain, pitching a coughing fit, or overwhelmed with nausea, saying quietly, “Now, now, children … ”

By sharing his life as a doctor openly, Nuland demonstrated the power of honest self-appraisal, something I have always tried to replicate: to admit my failures to myself and others, to recognize that I will fail, to find the dedication to improve. Shep has shown us that writing allows the physician to fulfill another duty. Doctor derives, of course, from the Latin docere, “to teach”; he once wrote, “Only by a frank discussion of the very details of dying can we best deal with those aspects that frighten us the most. It is by knowing the truth … that we rid ourselves of that fear of the terra incognita of death.” No doctor or writer did more to draw the map. Condolences to Dr. Nuland, his family, and those who knew him. I hope he was one of the lucky few to find death with dignity. But I am glad that, until my own time comes, I have his voice in my head; and if I need an extended conversation, it is just a bookshelf away.

Paul Kalanithi is the chief resident of the Department of Neurological Surgery at Stanford Hospital and Clinics, in Stanford, CA.

Small Wonder

“Bond always mistrusted short men. They grew up from childhood with an inferiority complex. All their lives they would strive to be big—bigger than the others who had teased them as a child. Napoleon had been short, and Hitler. It was the short men that caused all the trouble in the world.” ―Ian Fleming

Every class has one, or maybe two: a child so improbably small that this becomes his or her identity. There he is, on the end of your class picture year after year, forced to play a pawn in the fifth grade human-chess game (wearing a teacher’s old velour shirt as a tunic), any child role in a play, and later the deadweight in a freshman year trust exercise. He humbly takes this as his due. He does not need James Bond proto-Godwin-ing to make him feel the sting of his lowly position.

I have come across many treasures on the giveaway table of my building’s lobby, but my most recent acquisition is perhaps the greatest. Short Chic: The everything-you-need-to-know fashion guide for every woman under 5'4" could have come from the apartments of literally half my neighbors, but now it is mine. The cover features a petite woman dressed in the height of 1981 style: slouchy heeled boots, what looks like a leather duffel coat, a large woolen scarf, and some kind of bulbous cap that (the helpful height chart next to her informs us) brings her to a towering 5'1". The two authors, according to their back-flap bios, are, respectively, 5'3" and 5'2".

Yes, it is something of a time capsule: most of us can only dream of having to choose the right Cossack pajamas or “bell-boy jackets,” and figuring out which fur coat “won’t dwarf you”—short-haired furs with vertical seaming, FYI—is not a priority for many a modern petite. Then too, there are the various experts, designers (think Bob Mackie), small celebrities (think Morgan Fairchild), and regular working women decisively dating matters to the very early eighties. For instance:

One of the smartest turnouts we saw during Short Chic interviewing was the unmatched suit worn by Monica M., 5'2 1/2", a whip-smart tax attorney in her early thirties: a gold tweed short jacket, a cinnamon-colored wool jersey dirndl, a challis blouse in a cinnamon/gold/green print, with a loosely tied black silk scarf under the collar. Proof positive that success dressing takes many forms and doesn't always mean “suited and starched.”

But it is a useful handbook for many things: various questions of proportion, discussion of fabrics, and a still-handy guide to alteration. Lord knows I had never considered the sliding scale of wide-leg pant width (I should apparently be sporting an 18" cuff) or where to get a petite-scaled veil (Priscilla of Boston). And more to the point, it touches on very real issues of psychological worth, and the necessity of accepting who you are in a tall world.

For much of my life, I was the class runt. I was a particularly gnomish one, tiny as well as short, and did not reach five feet until my later teen years. I am not tall now—I stand 5'3" in my stocking feet, which I never am—but to have attained a modicum of adult scale, to not have to shop in the children’s department, to get to ride roller-coasters (should I ever wish to) still seems to me miraculous. To this day, former classmates of mine are surprised by my relative grandeur.

As youthful problems go, I know and knew that it is not a serious one. But at the same time, I can’t remember those days without a catch of panic in my chest and an almost physical sense of diminishment. Many of us bear the scars of teen years, and in the case of those of us who remained physical children while our peers matured around us, it can be hard even years later to see yourself as adult, let alone sexual. You make the best of your identity—what else can you do?—and to abandon that can feel not only difficult but wrong. Long after it should.

And I’m not even talking about all those bosses-love-tall-people studies. The introduction to Short Chic tackles the question in a particularly demoralizing way.

Despite the growing influx of women into the working world, women in business are still given second-class treatment because of their sex. Old prejudices die hard.

The woman who is short, however, has two strikes against her. Not only is she female, but she’s also up against another obstacle: in the business world, there’s an acknowledged stigma against those of less-than-average height (something shorter men have been combating for years). ... In nearly all fields, short women run up against a credibility gap owing to the stereotype of their size: Their petite looks seem to suggest “young” and “little girlish,” decidedly hampering their acceptance both as effective co-workers and managers.

Then they detail a few “exceptions—dynamic women under 5'4", who, with talent and persistence, have succeeded in all fields of endeavor”: a college president, a “retail whiz,” and, somewhat lamely, a gymnast.

I was thoroughly depressed after reading it. I hadn’t really felt bad about my height for a while, but I was suddenly overwhelmed with the feelings of inadequacy and invisibility that were so constant as a teenager. To distract myself, I decided to do something I never do: go out for a drink alone at the dreary neighborhood watering hole, which had always struck me as being a little Goodbar-esque. (I took Short Chic, as well as, for comfort, my copy of Lee Bailey’s City Food.) When I got there, the bouncer made me show ID, and expressed surprise at my age. “I’m little but I’m old,” I said, as always, quoting Dill in To Kill a Mockingbird.

And in that moment, I realized three things. One: it is worth it to be small to be able to quote that line, and it will not become less true as the years go on. Two: I am a grown-up woman. Three: if we all did what James Bond wanted, we’d only wear wide leather belts, unpolished nails, and no makeup.

And after that, I felt confident enough to tackle the chapter “Maternity Dressing: Looking Tall When You’re Dressing for Two.” We’ve come a long way, baby.

Scotty

The fourth of five vignettes.

Photo: M. O. Stevens, via Wikimedia Commons

M.&thinsp:F. K. Fisher had a magic gardener. This fellow, she wrote, understood the daily weather, the seasons and the various planting cycles, the necessity of encouraging or discouraging bird and insect life, landscape arrangement, grafting, and everything associated with the garden. He was an old Scotsman who, she discovered, in an earlier life, had written extensively on horticulture; and here he was, in his retirement, working for her, and quietly teaching her to tend her garden. He was the Platonic ideal of the gardener. And, of course, she wrote, he did not actually exist.

But I did not believe her.

I knew not only that he somewhere existed, but that I might be lucky enough to meet him face to face. Those besotted by an interest long for the perfect teacher. He who would be not only the complete master of his craft, but of himself: capable of leading the student, through a brilliant mixture of silence and misdirection, to reach his own, practicable conclusions.

Socrates, it is fairly clear, loved all humanity except his wife. And he may actually have loved her too, but she did not interest him. He preferred to go out of an evening, and observe, and talk to people. He was the wise old owl who sat on an oak. The more he heard the less he spoke, the less he spoke the more he heard, now wasn’t he a wise old bird? His interest, and his constant question, was, “What do you think?”

The perfect teacher, then, would not impart but would increase the chances of the student’s discovery of knowledge. He, like Socrates, would begin with humility before a mystery, the mystery to which he had dedicated his entire life; and his discoveries in blessed propinquity to his beloved craft would extend both vertically, through history, and horizontally, into fields however remotely related.

Scotty was a pilot.

He’d spent fifty years in aviation, as a student of aeronautical engineering, a military flyer, a pilot for the airlines, charter companies, film crews, and private individuals. He had an uncounted number of hours, and every rating known.

He had fifty years of unabated study of winds and weather, mechanics, aeronautics, aircraft design, pilotage, and he understood and loved teaching.

There he was, craggy and silent as Mary Fisher could wish. I could not ask him a question he could not answer, and his answer, almost invariably, was, “What do you think?”

He taught me to fly a plane.

David Mamet is a stage and film director as well as the author of numerous acclaimed plays, books, and screenplays. His latest book is Three War Stories .

Opera As It Used to Be, and Other News

Lodovico Burnacini, Il Pomo d’Oro, Act I, Scene V, Jupiter and His Court at Banquet with Discord Floating in a Cloud above the Table, hand-colored engraving, 1668. Image via the New York Review of Books.

The world’s twenty most stunning libraries. How many have you been shushed in?

Bill Cunningham’s early photographs of New York.

These illustrations from F rom the Score to the Stage: An Illustrated History of Continental Opera Production and Staging elucidate the finer points of things you didn’t know you cared about, such as stagecraft and lighting techniques in seventeenth-century opera.

The late philosopher Bernard Williams knew what to look for in a role model: “glistening contempt for philosophy … it is only by condescension or to amuse himself that he stays and listens to its arguments at all."

“Hilma af Klint was an old-school spiritualist who believed that she channeled psychic and esoteric messages from the so-called High Masters—who existed in another dimension—into abstract paintings.”

March 12, 2014

Emma Cline Wins Plimpton Prize; Ben Lerner Wins Terry Southern Prize

Photo of Emma Cline by James Williams; photo of Ben Lerner by Matt Lerner

Each year, at our annual Spring Revel, the board of The Paris Review awards two prizes for outstanding contributions to the magazine. It is with great pleasure that we announce our 2014 honorees.

The Plimpton Prize for Fiction is a $10,000 award given to a new voice from our last four issues. Named after our longtime editor George Plimpton, it commemorates his zeal for discovering new writers. This year’s Plimpton Prize will be presented by Lydia Davis to Emma Cline for her story “Marion,” from issue 205.

The Terry Southern Prize is a $5,000 award honoring “humor, wit, and sprezzatura” in work from either The Paris Review or the Daily. This year’s prize will be presented by Roz Chast to Ben Lerner for “False Spring” (issue 205) and “Specimen Days” (issue 208). Both are excerpts from his forthcoming novel 10:04.

From all of us on staff, a heartfelt chapeau!

(And if you haven’t bought your ticket to attend the Revel—supporting the magazine and writers you love—isn’t this the time?)

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers