The Paris Review's Blog, page 731

March 4, 2014

Transcending the Archetypes of War: An Interview with Phil Klay

Photo: Hannah Dunphy

In late 2011, Phil Klay, a former Marine officer who served in Iraq during the Surge, published “Redeployment,” a harrowing short story about a group of Marines returning stateside from the war. It drew praise for its subject matter, its lean prose, and its psychological acuity. Klay’s first collection, also titled Redeployment, is out this week. Its twelve stories revolve around war and its aftermath. Klay’s narrators include a State Department official charged with popularizing baseball in Iraq and a military chaplain offering spiritual guidance to an out-of-control unit.

Like a young professor who is still as comfortable in the world as he is in the library, Klay has an easygoing warmth. He exudes a passion for and knowledge of his craft. He is also unfailingly punctual. Last month, we sat down over coffee to discuss his book, the state of contemporary war literature, and the pitfalls of drawing too much from personal experience when writing fiction.

First books by vet-writers often read as rough autobiography, but in your collection, every story has a different narrator. Was this is a deliberate choice?

It was. When I first came back from Iraq, I of course found myself thinking a lot about it. Not just my experiences, but those of people I talked to, friends, and colleagues. What did our deployment mean, where did it fit into the broader perspective of what we as a country were doing? What was it like going out and making condolence payments to Iraqi families? What about the artilleryman who sent rounds downrange but never saw the effects of what happened, didn’t know how to conceptualize the bodies of those he helped kill, but wanted to? Even in my earliest stories, I knew I wasn’t writing about myself.

It also felt important to convey that modern war is this huge industrial-scale process with a lot of parts making the machinery work. There’s an incredible diversity of experience. We have a tendency to think of war as this quasi-mystical thing, and that interpretation flattens the experience—by using different perspectives, I wanted to open a place for readers to compare and contrast, to make judgments, to engage.

“Prayer in the Furnace” is narrated by a military chaplain in Ramadi during one of the most violent periods of the war. How did that story come about?

A lot of the great pieces of journalism from Iraq showed how important command influence was in violent, aggressive environments, where Marines and soldiers had a constrained set of choices to make in sudden moments. Sometimes that command influence was positive. Sometimes it wasn’t. So as “Prayer in the Furnace” developed in my mind, I decided to tell it from the perspective of someone who is sympathetic to those men and the decisions they make, but removed enough to adopt a more contemplative stance. An observer who’s with them, but not of them.

I wanted to write from the point of view of a chaplain because I was interested in what that role meant. I knew some very good chaplains during my time in the Marines and some not so good ones—the story seemed an opportunity to ask a variety of moral questions, not just about war. When I was developing the story, I read Bernanos’s The Diary of a Young Country Priest, which, though it has very little to do with war, muses upon the same set of issues.

The collection strikes an even balance between stories of war and stories of aftermath. Why was exploring the postwar experience significant?

One of the things that really stands out about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan is the degree of disconnect between the military and civilian America. That seems to play out most during the homecoming experience. On my own mid-tour leave, I flew home to New York. I lived near a trauma facility in Anbar and had grown used to seeing people come in with really horrible injuries. Then, a couple days later, I found myself walking down Madison Avenue, realizing there was zero sense that we were a nation at war. I felt like a stranger in my own country. And this was in 2007. Things are worse now.

Most vets of these wars have stories like that. For me, that walk down Madison raised a lot of questions about citizenship, the relationship of the soldier to the citizen, the relationship of the citizen to the nation at war. Those things interest me, so it made sense to write about them. My purpose with this book is not to say, This is how it is. Sure, I want to explore the combat experiences and evoke them accurately, but I also sought to place them within a larger context.

Regarding that larger context—the war in Iraq lasted nine years, while the war in Afghanistan has persisted for well over a decade now. Both are, of course, incredibly politicized. Certainly you’re aware it’ll be the rare reader who enters your collection with a completely open mind.

There’s so much cultural garbage floating around about war and veterans, and these wars and our generation of veterans, particularly. These are topics that are very complicated. They need to be approached in a delicate way, but they frequently aren’t. A lot of this has to do with politics. There’s a wide spectrum between a Navy SEAL hero-killer and a traumatized victim, but those are the archetypes—hashed and rehashed in the media, in popular culture, in the minds of people with a lot of preconceived notions but not much else.

For example, there’s a bit in one of the stories—“Unless It’s a Sucking Chest Wound”—when a law student tells the narrator all this stuff that happened to her and says, I feel like I can tell you this because you have PTSD too. He responds, Well, I don’t have PTSD. But it doesn’t matter—she doesn’t believe him, because he fits her preconceived notion of what a vet is and should be. Then he finds himself going along with it, and not for any noble reason.

Like you said, we’re well past the decade marker of the “War on Terror,” but there’s still so little understanding—or interest—in these wars’ lessons and legacies. If we as a society and culture are going to talk about war seriously, we need a more nuanced discussion. We need to think about how poor foreign policy plays out—how it’s experienced by those who exact it and those who are affected by it.

Love and Friendship

Johannes Vermeer, Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid, oil on canvas, c. 1670-71

Do you remember Amish Friendship Bread? Basically, it’s like a chain letter, except you give people bags of gloppy, smelly starter, which they grow and mix with various strange ingredients, and distribute along with loaves of bread; the idea is you pass it along in perpetuity. It’s easy to find the recipe online. One—which attributes it to a “Mrs. Norma Condon of Los Angeles”—describes it thusly: “This is more than a recipe—it’s a way of thinking. In our hi-tech world almost everything comes prepackaged and designed for instant gratification. So where does a recipe that takes ten days to make fit in? Maybe it’s a touchstone to our past—to those days not so very long ago when everything we did took time and where a bread that took ten days to make was not as extraordinary as it seems today.” (Well, those days not very long ago when you made a bread with a box of instant vanilla pudding, anyway.)

Name notwithstanding, the bread apparently bears very little resemblance to anything made by the Pennsylvania Dutch. Wikipedia was good enough to address the issue, informing us that “according to Elizabeth Coblentz, a member of the Old Order Amish and the author of the syndicated column ‘The Amish Cook,’ true Amish friendship bread is ‘just sourdough bread that is passed around to the sick and needy.’”

As memory serves, I was neither particularly needy nor infirm the long-ago summer it came into my life, but, perhaps knowing that I liked to bake, a church friend of my grandmother’s brought me the Ziploc bag of starter, and I dutifully fed and stirred it every day before forcing sacks of it on three hapless neighbors, along with the obligatory mimeographed paper bearing the instructions and recipe. Not making it did not even occur to me: this was on the order of a sacred trust. And while the final product—which is somewhere between a gently-spiced snack and a dessert—may leave something to be desired, it’s true that making the friendship bread was a fun experience.

I think that was the last chain I ever continued. But then, in those early days of email, we all became reckless chain-breakers: there was simply no way to keep up with the letters and threats and benign pyramid schemes that filled our inboxes. And then you call their bluff soon enough you learn that no bad luck has befallen you. Or worse, that it has, and it’s too late. And after a certain point, they just stop coming. Maybe people can tell you don’t have the vocation to be a priestess of the chain flame, or whatever.

So I was surprised, the other day, to receive an email about a poetry chain. Participants were encouraged to send along inspiring bits of favorite verse to the lead name on a list and forward the chain to an additional twenty friends. My initial reaction was skepticism; I didn’t want to spend the time doing it, or flood my friends’ inboxes. But there were things about the email I liked—that it was specifically a one-time thing, that we were encouraged to use a poem or quote we already had in mind. So I did just that: I sent along the Keats sonnet that has been buzzing around my head to the name on the list, and, feeling a bit like someone’s aunt, passed the email on to friends.

Then the replies started coming in, from names I recognized and those I didn’t. There was a quote from Calvino’s Invisible Cities, and the lyrics to “Sunny Side of the Street.” I opened my email before breakfast to find a Persian poem:

The vegetables would like to be cut

By someone who is singing God’s Name

How could Hafiz know

Such top secret information?

Because

Once we were all tomatoes,

Potatoes, onions or

Zucchini.

and next time I checked, a link to Built to Spill’s “Fly Around My Pretty Little Miss.”

This was the shortest: “O little Purgatory, / the necessary expanse / between desire and duty!” (That’s Nicky Beer’s “Ode to the Perineum.”)

I was so inspired by this project that I began thinking fondly of that long-ago batch of Friendship Bread, even toying with the idea of reanimating the chain, maybe with a streamlined recipe. Delighted to see that no lesser an authority than Martha Stewart had provided a recipe, I clicked on the comments. “I very disappointed with Martha’s lack of understanding the recipe,” said one Mary. “She should have read and understood it before going on air. I thought it really made her look ‘silly.’ Also the Amish do not watch TV. The recipe does NOT even list the instant pudding so it is wrong also. What’s up with this? Martha can do better than this. She should do another show and do it correctly.” Bad luck.

Fata Morgana

Reinaldo Arenas, writers in exile, and a visit to the Havana of 1987.

Hotel Habana Libre. Photo: Sandino235, via Wikimedia Commons

Twenty years have passed since the publication of Before Night Falls, Reinaldo Arenas’s tale of his years in Cuba under the Castro regime and his life in exile in the U.S. One of the most talented and prolific writers to emerge during the revolution, Arenas was persecuted for his writings and his homosexuality. He escaped in the 1980 Mariel boatlift and in 1990, dying of AIDS, committed suicide in his Hell’s Kitchen apartment. Published in 1993, Before Night Falls is as urgent and compelling as ever—a portrait of exile and longing, of the anguish and rage of the dispossessed.

Born in 1943 on a farm in the province of Oriente, Cuba, Arenas developed a rich inner life early on. “[Regarding] the magical, the mysterious, which is so essential for the development of creativity, my childhood was the most literary time of my life,” he wrote in Before Night Falls. Morning fog blanketing the landscape like a ghostly shroud, palm trees bursting into flame as lightning struck, dark rivers flowing endlessly to the sea—all entranced him. Most astonishing was night, when, beneath the ancient glittering sky, his grandmother told tales of the supernatural.

At sixteen, Arenas joined Castro’s rebels in the mountains, but his enthusiasm gave way to disenchantment and despair, a trajectory he chronicled in his writing. In 1962, he finished Celestino antes del alba (published in the U.S. as Singing from the Well), the first in his Pentagonía, a series of five semi-autobiographical books. Celestino won second prize in the 1965 UNEAC (Cuban Writers and Artists Union) competition; in 1967, it was published in a print run of two thousand copies that sold out in one week. No further editions were issued; it was the only novel Arenas would publish in Cuba. His next novel, El mundo alucinante (published in the U.S. as The Ill-Fated Peregrinations of Fray Servando), the tale of a renegade Mexican monk who dreams of a free society, was banned in Cuba for its “erotic passages” but smuggled out and published in France in 1968 to great acclaim.

In 1973, while Arenas and a friend were swimming at the beach, their belongings were stolen by some men they’d just had sex with in the mangroves. When they reported the theft, the police accused them of public lewdness and disturbing the peace. Later, even though the men were of age, Arenas would be charged with corruption of minors. The case against him gained momentum, with the government’s “evidence” including his publishing activity abroad, his homosexuality, and a statement from UNEAC declaring him immoral. After several unsuccessful attempts to escape the island, including on an inner tube, Arenas was incarcerated at El Morro, a former Spanish fortress overlooking Havana Harbor. In this hellhole of rape, murder, and torture, Arenas suffered very dark days, including a period of solitary confinement in a one-meter-high cell. “I must confess,” he wrote in Before Night Falls, “that I never recovered from my experiences in Cuban jails; I think no former prisoner can.”

Released in 1976, Arenas wandered about, jobless and homeless, writing when he could and trying to stay under the radar. When, in 1979, a group of visiting American professors inquired after him, people said they had no idea who he was. The most promising lead came from someone who’d heard Arenas was living under a bridge somewhere. “I had suddenly become invisible,” Arenas wrote. “[People], perhaps out of mere cowardice, forgot I existed, though we had shared long friendships.” In those years, he saw his “youth vanish without ever having been a free person … I had never been allowed to be a real human being in the fullest sense of the word … I lived in terror in my country and with the hope of someday being able to escape.”

When he at last succeeded, slipping out in the chaos of the Mariel boatlift, it was only to discover that true escape was impossible. Attacked by leftist intellectuals for his denunciations of the Castro regime, condemned by some of his publishers for leaving Cuba, “despised and forsaken” by Miami’s Cuban exile community, Arenas moved after a few months to New York. He fell in love with the city’s tremendous vitality, but found no lasting solace. In Before Night Falls, recorded on twenty cassettes and finished in the last months of his life, he wrote, “The exile is a person who, having lost a loved one, keeps searching for the face he loves in every new face and, forever deceiving himself, thinks he has found it.”

* * *

Late on a warm night in 1987, I left Miami for Havana to report on contemporary Cuban writing and see Arenas’s environment firsthand. I’d met Arenas in 1983, when I interviewed him for my comparative literature thesis one fall afternoon at Princeton. The thesis included my translations of some of his work, one of which, a novella entitled “Old Rosa,” was later published in Old Rosa: A Novel in Two Stories.

As the Challenger Airlines plane churned through the predawn darkness, I recalled Arenas’s dedication in his novella The Brightest Star—“To Nelson, in the air”—in memory of Nelson Rodriguez Leyva, a friend and fellow writer who was executed in 1971, at the age of eighteen, after he’d tried to hijack a Cubana domestic flight to the U.S. And I remembered the horrifying story told by poet Armando Valladares in Against All Hope, the memoir of the twenty-two years he was imprisoned by the Castro regime. According to a recent New York Times report, Cuba had the greatest number of political prisoners of any country in the world. Some were journalists—not foreign ones as far as I knew, but I’d heard that foreign reporters were sometimes denied entry, expelled, or detained on arrival.

In about half an hour, the lights of the island came into view and we began our descent.

What I’d forgotten—or been unable to imagine—on the way to Havana was that somewhere among the horror stories would lie another story. It was the melancholy beauty of the city that surprised me most. The pastel, salt-worn buildings with iron gratings over the windows and enclosed leafy patios; the restless, encircling sea. Men with slicked-back hair cruised the streets in vintage Dodges and Cadillacs. Women in sleeveless tops, cotton skirts, and sandals stood waiting for the bus. At the Plaza de Armas in Old Havana, lovers strolled along stone arcades, a pharmacy sold medicines in white ceramic bottles painted with blue flowers, and for five centavos, mineral water poured from a creamy porcelain jar. I bought a Granma newspaper from a vendor outside my hotel and noticed it was the previous day’s edition. “Da lo mismo,” the man said, his leathery face unsmiling. It doesn’t make any difference.

Havana was young men and women in military fatigues, people calling me Compañera Ana (Comrade Ann). It was an evening at the ballet, where a man gave me a rose and a note: We are stockpiling sardines. It was flea-bitten, emaciated dogs; people waiting in line all night to buy deodorant and women asking if I could spare them a lipstick; impromptu salsa jam sessions, men drumming on soda cans or against walls; the poet Eliseo Diego reading me his translation of Yeats’s “When You Are Old” one heat-stunned afternoon. An American couple who, sure their hotel room was bugged, found a cluster of wires under the carpet and cut them, at which point the chandelier in the room below crashed to the floor. It was Finca Vigia, Hemingway’s house, where everything was kept just as he’d left it in 1960: the typewriter, the visor he wore while writing, the tombstones for his cats. It was a bookstore near the Hotel Habana Libre (formerly the Hilton) where the book of the week was Arthur Eaglefield Hull’s La armonía moderna: su explicación y aplicación (Modern Harmony: Its Explanation and Application; © 1915). In dilapidated mansions converted to offices, employees slept on desks under performance charts with tattered gold paper stars glued to them; in stores, clerks slumbered on top of the merchandise. At restaurants, waiters ignored you, chatting and laughing amongst themselves, and—if they ever did get around to taking your order—almost nothing on the menu was available.

Over ice cream at the Coppelia—an open-air ice-cream parlor with staggeringly long lines—or chop suey and beer at Mandarin restaurant, or cocktails at the Bar Azul, where a window behind the bar provided an underwater view of the pale limbs of swimmers in the pool—I talked to writers. The older, well-known ones, many of whom had, like Arenas, at first supported the Revolution, were long gone. Guillermo Cabrera Infante, no longer allowed to publish in Cuba, had been in exile in Europe since the mid-sixties. José Lezama Lima, censured by the regime for the homosexual passages in his novel Paradiso, had died in 1976, and Virgilio Piñera, jailed and ostracized for his political views and homosexuality, died under mysterious circumstances in 1979. Heberto Padilla left Cuba in 1980 after being imprisoned for criticizing the Revolution and forced to denounce friends and family.

The newer writers I spoke with, mostly men, were in their twenties and early thirties. Some, like Arenas, were originally from the countryside, and said that in pre-Revolutionary Cuba, their talent would never have been discovered, not least because the literacy rate was only about seventy-five percent, especially in rural areas. Before the Revolution, they told me, being a writer was something to be ashamed of—there were hardly any bookstores, and it was almost impossible to make money writing. But now writers were well-respected, bookstores could be found in even the smallest towns, and publishing was subsidized by the state. Writers were free to write whatever they wanted: instead of writing only about things like the heroes of the Sierra Maestra, the literacy campaign, the Bay of Pigs, the adjustment of the bourgeois to the new society, they were now writing science fiction, spy novels, horror, erotica.

“If people aren’t writing what they want to, that’s their problem,” one writer told me. “No themes are taboo in the way they used to be. We’re writing about sex, divorce, problems with the system.” The dark days of censorship, middle-of-the-night house searches and arrests, were over. “For a book to be published,” another writer explained, “it has to be good. If people aren’t getting published, it’s because their work isn’t good enough.” But the one thing you could not do, he said, was criticize the Revolution. Problems within the Revolution, yes, but not the Revolution itself. In a speech made soon after his triumph, Castro had insisted that artists were entitled to freedom of expression; the only caveat was that this expression must accord with the aims of the Revolution. “¡Dentro de la Revolución, todo!” Castro thundered. “¡Contra la Revolución, nada!” “Within the Revolution, everything! Against the Revolution, nothing!”

Almost everyone was kind, funny, eager to talk, and, as we got to know each other, more and more willing to deviate from the party line. “It’s a question of maintaining a delicate balance between being honest with yourself and passing the censors,” one writer explained. “To tell you the truth, it’s stifling here. I feel like I’m suffocating.” People were desperate for books and magazines: one journalist offered me anything I wanted from his library if I would send him reading materials from the States. “I don’t understand the U.S. and el bloqueo,” he said, referring to the American embargo against Cuba, in effect since 1960. “If I were Ronald Reagan I’d be sending everything I could to Cuba: books, magazines, movies.”

Important matters were never discussed on the telephone. People worried that someone might be listening, that they might be reported for saying something “counter-revolutionary.” I spent long windy evenings at houses with the doors and windows left open to keep the neighbors from getting suspicious. It was so difficult to catch what people were saying that I began to wonder if I was getting hard of hearing—but then I realized that most of my conversations were in crowded rooms, in private offices with the doors open to noisy corridors.

With each day, I felt more nervous and exhausted. It was the disjunction: how to reconcile the island’s brutal government with the warmth of the people and the beauty of the surroundings? I was followed everywhere by plainclothesmen and the security police. Trained by the East Germans, the police were easy to spot in their blue uniforms and caps, handguns at their hips. “Everybody is scared of them,” one writer told me. “They’re so smart. I don’t understand it—they know everything. It seems like they even know what you’re thinking.”

When I asked people about Arenas, I was told, of his arrest in 1973, that he’d been imprisoned for paying a minor to engage in homosexual activity. (“He wasn’t arrested for writing against the Revolution,” one writer told me, “but for soliciting a minor. You would do the same in your country.”) Publicly, the people I talked to dismissed Arenas as suffering from mental problems: “I knew Reinaldo when he was here,” said one writer. “There was always something funny about him, like he was a little off in the head.”

But privately, he was greatly admired. On a street corner one evening, a writer told me he’d devoured Arenas’s Termina el desfile (The Parade Ends), a story about a young man’s disillusionment with the Revolution, on a deserted late-night bus run when a friend loaned it to him for two hours. “None of Cuba’s writers today,” another writer said, “comes close to Reinaldo.”

Arenas had told me in our interview a few years earlier that all of his writing was one long book, fragments of a single dreamlike, hallucinatory world: “I’ve never been interested in telling a story in a purely anecdotal or linear way. ‘Realist’ literature is, to me, the least realistic, because it eliminates what gives the human his reality, his mystery, his power of creation, of doubt, of dreaming, of thinking, of nightmare.”

In Havana, I understood something new about this power, how it could allow us to undertake—like medieval pilgrims who couldn’t travel to Jerusalem—our own road to Jerusalem, wherever we may be.

* * *

The days passed in the humid, windswept city. Havana came to life well before dawn, buses and trucks lurching along dark streets, diesel fumes wafting through windows left open to the tropical night. The sun beat down. It rained, silver sheets of water swaying in a wraithlike dance. Storms tossed the palms and whipped the sea into a frenzy. Great waves surged over the sea wall along the Malecon promenade extending five miles from the harbor. The freeing, imprisoning sea was everywhere: you could see it, taste it, feel it on your skin. What was it like to live surrounded by water? The state of suspension, of being adrift, of forever traveling and never arriving. Walking along the Malecon, I watched ships on the horizon: it took time to understand whether they were going out or coming in.

Only ninety miles away was Key West, the U.S.A. If you looked hard and long enough, it rose like a fata morgana, one of the mirages that appear over deserts and oceans, a mirror of something that lies beyond the horizon. Cubans tried to escape on inner tubes, on rafts made of wood and lashed-together oil drums, in homemade boats, and even, once, in a Chevy truck with a propeller attached. At the mercy of nature, of the ocean currents that would carry them to freedom or return them to their sorrows, some made it; others drowned or were caught.

“Those who are critical should have left Cuba when they had the chance,” people told me. (But there was a joke circulating in Havana: if a flotilla of boats sailed up to the Malecon to take people away, not even a cat would be left in the city.) Still, while defectors were called gusanos or “worms,” there was a certain compassion for them because they could never return to their homeland. The prospect of being dépaysé seemed to be enough to convince many to remain. Again and again, people told me they wouldn’t leave if they had the chance: their parents were getting old, they had a sick brother, they couldn’t live without their family and friends. They’d also heard the cautionary tales about people who’d made it to Miami, New York, Chicago, but were living in the margins, jobless and lonely. In Havana, people were in exile in their own country. There was un anhelo en los ojos, a yearning in people’s eyes—a readiness, a heaviness, a hope.

At night, Havana was dark because of Castro’s austerity measures. Walking around, I felt as if I’d wandered into a state of siege or a de Chirico dreamscape. But even though the city was often deserted, it felt crowded, like no one had ever left. The doorways and narrow streets were alive with shadowy figures and voices.

“Every person who lives outside his context is always a bit of a ghost,” Arenas told me that fall afternoon at Princeton, “because I am here, but at the same time I remember a person who walked those streets, who is there, and that same person is me. So sometimes I really don’t know if I am here or there.” At times, his longing to be in Cuba was greater than the necessity of being in New York. This was not, he felt, a personal calamity but a universal one, because the world was full of uprooted people. It was why, he believed, all the literature of the twentieth century was somewhat condemned to grapple with the theme of uprootedness. He felt “less bad” in New York than in other places like Miami, Puerto Rico, Spain, because in New York he could have both people and solitude. “In other places, you suffer the people or you suffer the solitude, and both are terrible. But New York allows you that equilibrium: you write, you mix with the multitudes, leave them, jump back in. Still, I don’t know where I can settle. I really don’t know.”

In those last days in his Hell’s Kitchen walk-up, Arenas wrote, “I have realized that an exile has no place anywhere, because there is no place, because the place where we started to dream, where we discovered the natural world around us, read our first book, loved for the first time, is always the world of our dreams.”

Ann Tashi Slater’s translation of Reinaldo Arenas’s “La vieja Rosa” was published in Old Rosa: A Novel in Two Stories. She is working on a novel based on the Tibetan side of her family and a travel memoir set in India.

Who Wants Flapjacks?

Photo: Janine, via Wikimedia Commons

Today is Mardi Gras, yes—the beads, the cake, the booze, the breasts. We get it. I love a Dionysian spectacle as much as the next joe, but one can take only so many years of unhinged debauchery, face paint, and galettes des Rois before the charm wears thin, even when there’s nudity involved. We need a change of pace.

Enter Shrove Tuesday, i.e. National Pancake Day, i.e. today. Picture a Mardi Gras where men lust not for nipples, but for fluffy flapjacks. The Oxford English Dictionary Word of the Day has just taught me about the pancake bell, “A bell rung on Shrove Tuesday at or about eleven a.m., popularly associated with the making of pancakes.”

Imagine! A bell devoted entirely to pancakes, a bell whose mellifluous peals say to all within earshot, Abandon your post, hire a sitter, and get thee to the griddle—it is time to eat starch.

Shrove is the past tense of shrive, meaning “to hear the confession of, assign penance to, and absolve.” On the Tuesday before Lent began, the same bell that called people to confession served as a stern reminder: use your eggs, milk, and butter now, because once the day is out, we must begin ritually fasting and you are totally fucked.

Thus, everyone began to run home and whip up hotcakes; some people, rumor has it, even tried to cook the pancakes as they ran home, tossing and jogging, jogging and tossing, perhaps ladling syrup on occasion. To this day, the British town of Olney holds a pancake race (“Participants must don an apron and hat or scarf to compete. They are also required to toss the pancake three times during the 415 yard race, serve it to the bell ringer, and receive a kiss from him”) and IHOP hosts a fundraiser, though it does not, to my knowledge, involve the tolling of a pancake bell.

The OED includes an early reference to the bell, from Thomas Dekker’s The Shoemakers Holiday, which dates to 1600: “Vpon euery Shroue tuesday, at the sound of the pancake bell: my fine dapper Assyrian lads, shall clap vp their shop windows, and away. This is the day, and this day they shall doot, they shall doot.”

The Idylls of Prison, and Other News

Alyse Emdur, Anonymous Backdrop Painted in State Correctional Facility, Otisville, New York. Image via Beautiful Decay.

Who owns the moon? It could be you! (It’s probably not you.)

The National Enquirer’s sixties covers show how the language of scandal has evolved—what used to pass as odious is now just sort of quaint. “I’M A SLOB. I Burp & Slurp in Public,” says one headline. The horror.

Brian Eno has chosen twenty essential books for saving civilization; I’ve read zero of them.

“I thought at the time it was really bad luck to survive. I really wanted to die with them.” An interview with a kamikaze pilot.

The surreal world of prison portraiture: “visitation rooms of penitentiaries have backdrops where friends and family can get pictures taken of/with the inmate … Often, these backgrounds are idyllic landscapes that offer the inmate a moment to emotionally escape their sentence.”

March 3, 2014

Murder, She Wrote

Photo: eflon, via Flickr

Over the weekend, for reasons too silly to get into, I decided to change my phone number. It was a surprisingly emotional process. I have had this, my first phone number, for some twelve years, and there was something bittersweet about abandoning the area code of my parents’ suburban home. A great deal of the difficulty, however, arose from my own incompetence, a faulty Internet connection, and a confusing and ancient family plan. Long story short, I accidentally changed my dad’s number instead. The result was a small transcontinental panic, a volley of hysterical phone calls, and several confusing texts from my friends, each of which my dad apparently greeted with a suspicious “whoisthis?”

I was sure some enterprising suburbanite would snap up my dad’s abandoned 914 number before I could reclaim it, and my anxiety only grew as the automated voice on the customer-service line cheerily informed me that there was an unusually high call volume and the estimated wait time was eighteen minutes. I bit my nails and refreshed my browser every few minutes to find out if anything new had happened in the news, if, for example, we had sent troops into Ukraine. On speaker, the voice droned on about various mobile plans.

In the meantime, I took a call from my dad. “We’re very concerned,” he said. “Do you have a stalker? Is that why you’re changing numbers?”

“No. I don’t want to get into it. It’s complicated,” I said. “I just need a new number. And you have to stop watching the murder channel.”

“We can’t. The murder channel figures very prominently in our rotation. And every time a young woman is killed, we discuss the odds of the same thing happening to you.”

“No one’s going to murder me.”

“They all think that.”

At eighteen minutes and thirty-eight seconds, I was taken off hold. And the woman who answered, whom I will call BobbySue, was remarkable. “This is a pickle,” she said, with a heavy southern accent. “But we’re going to fix it.” The fix proved challenging. Several things didn’t work. The number was in some kind of limbo. It belonged to a different carrier. We couldn’t reverse the process. Various departments were contacted, in vain. Minutes turned into an hour. I was beginning to despair. “Don’t give up!” she said. “I’m going to try something we’ve never done before.” And she disappeared for fifteen minutes. “Don’t think I was just cooling my heels,” she said when she came back on. “I’ve been manually searching through every 914 number available … and I found it!”

“Oh, bless you, BobbySue!” I said. “I hope this call was monitored for customer-service purposes! Is there someone I can call, to compliment your work?”

“Hush, it’s my job!” she said. “Now I’m just going to call your dad and make sure it works.”

Fifteen minutes later, she called back. “Your dad is just as sweet as sugar,” she said. “We had a nice talk.”

I thanked her again, profusely, and went to make my bed. A few minutes later, my phone rang—curious only because no one yet had the new number.

“This is BobbySue,” she said. “I was just looking through your dad’s records, and I’m very concerned—there’s no password on his voicemail.”

“Oh,” I said. “Well, I’ll … encourage him to add one. Thank you for letting me know.”

“People think it’s not important,” she said. “But I’m here to tell you the truth. Teenagers can get into your mailbox and leave ugly outgoing messages. And you don’t even know they’ve done it. And they say very ugly things. Very ugly.”

“Well, I’ll certainly tell him,” I said. “Thanks—”

“That’s not all.” she said. “They can also erase important messages from your mailbox. Frankly, it happened to me.”

“Well, that’s awful,” I said. “Thank—”

“It almost cost me my life,” she continued. “You see, there was a threat against my life. A murder attempt. I’ll call your dad and tell him how to do it.”

“That’s so kind, but it’s really above and beyond the call of duty,” I told her hastily. “I’ll be sure to tell him, and I’ll emphasize the … the risks.”

“Be sure you do,” she said darkly.

I called my dad and related the conversation. “Put the password on,” I said. “Or you might get murdered. Or, I guess, miss the call warning you of the murder. Not sure.”

“Yeah, I don’t need that,” said my dad. “No point in descending to paranoia.”

The call was interrupted by the beep of a text message. “This is BobbySue,” it read. “I don’t want this experience to frighten you out of using self-service options. There is almost nothing we can’t figure out together.”

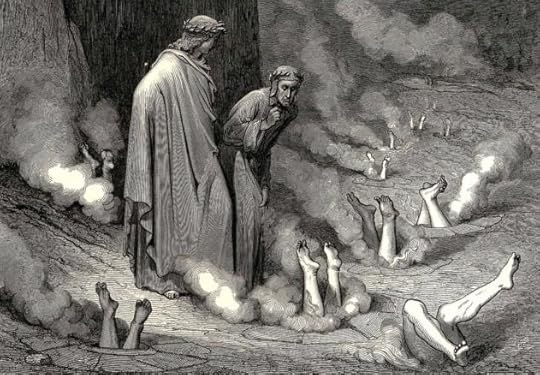

Recapping Dante: Canto 19, or Popes Under Fire

Gustave Doré, The Inferno, Canto XIX

This winter, we’re recapping the Inferno. Read along! This week: an internal memo from the Vatican to the Archdiocese of Florence after the release of Canto XIX.

By now, you have seen excerpts from last night’s episode of Mr. Alighieri’s The Inferno, Canto 19, in which Dante visits the ditch that punishes simony. We have filed a defamation suit and sent a cease and desist to Dante’s attorney, but there will undoubtedly be a public reaction. Rest assured: our lawyers are going to crucify this guy.

For those of you who are not aware, the segment focuses on Dante and Virgil’s descent through the eighth circle of hell, where Dante enters the realm of simony—which, more or less, covers any form of buying or selling powers or positions in the Church. At this point, we feel it is important to remind you all that any rumors of simony were supposed to have been snuffed out for good this last quarter. It has come to our attention that Dante must be getting his information from within our offices. At this time, any higher-ranking members of the church who happen to be White Guelphs are our prime suspects. We’ve launched an internal investigation, but please be at high alert and keep all information on a need-to-know basis until we have resolved this problem.

As the canto goes on, Dante sees a bunch of feet in the air—sinners buried head-first in the ground, the soles of their feet covered in fire as they are slowly ingested by hell. As he approaches, one buried sinner, Pope Nicholas III, mistakes Dante for another pope, Boniface VIII. Dante then listens to Nicholas confess to simony and describe the way he lined his pockets. Clearly Dante is not our most subtle critic, but we cannot stand idly by as he implies that all our popes are simonists. It’s bad for business. Short of having a pope curse in public, nothing could be more damning.

After the confession, Dante’s character begins an extended tirade, berating the Church—he even reminds Nicholas that the Lord didn’t ask Peter for treasures in exchange for the “keys into his keeping.” It’s a petty attempt at making us look like a bunch of hack televangelists. It shall not go unpunished.

For the coup de grâce, Dante informs Nicholas that he would have used much harsher language in his rant, had it not been for Dante’s own profound respect and love for the Church. This self-righteous audacity, this flippant disregard for the power of the current leadership, is only the first of the troubles we can expect if we do not respond with equal or greater force. Our colleagues in the Florentine municipal office are currently looking into whether we can have Dante exiled.

We urge you all to keep elevator chatter to a minimum, and to shred all invoices, expense reports, and promotion notices until we get to the bottom of this. Do not speak to the press. Refrain from releasing any statements until our public relations office has had an opportunity to go over it first. I am sure many of your congregants are very curious, but please do all you can to keep everyone calm. Dante has already jabbed at us a few times in his Inferno, and so it is important, especially for those of you in Florence, that we refrain from provoking him. We have no way of knowing what he will choose to say in Canto 20.

Yours concernedly,

The Vatican Press Office

Alexander Aciman is the author of Twitterature. He has written for the New York Times, Tablet, the Wall Street Journal, and TIME. Follow him on Twitter at @acimania.

Presenting Our Spring Issue

Our new Spring issue is full of firsts. That fellow on the cover is Evan Connell, whose first novel, Mrs. Bridge, originated as a short story in our Fall 1955 issue.

Our new Spring issue is full of firsts. That fellow on the cover is Evan Connell, whose first novel, Mrs. Bridge, originated as a short story in our Fall 1955 issue.

Then there’s our interview with Matthew Weiner, the creator of Mad Men—the first Art of Screenwriting interview to feature a television writer. Weiner discusses the influence of T.S. Eliot, John Cheever, Alfred Hitchcock, and The Sopranos on his work:

Mad Men would have been some sort of crisp, soapy version of The West Wing if not for The Sopranos. Peggy would have been a climber. All the things that people thought were going to happen would have happened … The important thing, for me, was hearing the way David Chase indulged the subconscious. I learned not to question its communicative power.

And in the Art of Nonfiction No. 7, Adam Phillips grants us our first-ever interview with a psychoanalyst; he discusses not just his writing but his philosophy, and the importance of psychoanalysis:

When people say, “I’m the kind of person who,” my heart always sinks. These are formulas, we’ve all got about ten formulas about who we are, what we like, the kind of people we like, all that stuff. The disparity between these phrases and how one experiences oneself minute by minute is ludicrous. It’s like the caption under a painting. You think, Well, yeah, I can see it’s called that. But you need to look at the picture.

There’s also our first story from Zadie Smith; fiction from Ben Lerner, Luke Mogelson, and Bill Cotter; and the second installment of Rachel Cusk’s novel, Outline, with illustrations by Samantha Hahn. Plus new poems by John Ashbery, Dorothea Lasky, Carol Muske-Dukes, Geoffrey G. O’Brien, Nick Laird, and the inimitable Frederick Seidel, who will be honored with the Hadada Award next month at our Spring Revel.

And a portfolio of previously unpublished photographs by Francesca Woodman.

It all adds up to an issue sure to put a spring in your step.

Celebrating Alain Resnais, and Other News

A still from a 1961 interview with Alain Resnais.

Who can talk about the Oscars when Alain Resnais has died, at ninety-one? YouTube offers a number of interviews with him; many consist of baffled Frenchmen attempting to divine the meaning of Last Year in Marienbad.

Scientists have looked into being funny: the whys, the hows, the what-have-yous. “It could be that office-cooler witticisms, stand-up routines, and sitcoms are just part of one big pickup line you never saw coming.” Surely many of us have seen it coming.

Bill Watterson, the Calvin and Hobbes creator, has drawn his first public cartoon in nearly twenty years. It contains buttocks.

“Surely the fact that writers really don’t mean a goddamn thing to nine-tenths of the population doesn’t hurt. It’s inebriating.” An expansive new interview with Philip Roth.

Take out your credit card and clear your schedule: you’re about to buy an erotic computer game based on Oscar Wilde’s Salomé.

February 28, 2014

What We’re Loving: Science, Spicer, Sea Maidens, Sandwiches

Rita Greer, The Scientists, 2007

The Haggis-on-Whey World of Unbelievable Brilliance is McSweeney’s hilarious series of faux-science books. The latest volume, “Children and the Tundra,” is due out in May; it includes such edifying features as “Quick Fixes for the Growing Epidemic of Talking Child Syndrome,” “Snow Druids: Fact and Fiction,” and “Comparing Snow with Presidents Past and Present.” (Snow and Zachary Taylor share the following attributes: cold, white, usually on the ground.) In its tone and design, to say nothing of the sturdiness of its typefaces, Haggis-on-Whey nails the authoritarian aesthetic of 1950s textbooks. Most important, it is very, very silly. —Dan Piepenbring

Wordsworth looked forward to a day when poets would “be ready to follow the steps of the man of Science … carrying sensation into the midst of the objects of Science itself.” Alfonso D’Aquino is one such poet of sensation and science. Fungus skull eye wing, his first collection available in English, is dense with the tropical life of Cuernavaca: root systems, veins of mineral, tangles of foliage. Some of the poems are spookily nonhuman; in others, even the stones seem to speak: “I squint fixedly / and find / in this marvelous density in the hollow of my hand / in its livid insomniac paleness / and in its veins dialogues / that only for a moment crisscross.” Forrest Gander’s translation is another marvel. —Robyn Creswell

You could easily teach a whole seminar on Denis Johnson’s “The Largesse of the Sea Maiden” (in this week’s New Yorker). You could prepare students by assigning them “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love” and “The Dead,” which seem to me a sort of North and South Pole to Johnson’s story, and shape its beginning and end. Then you could have students compare the two paintings in the story, and the two newspapers called the Post, and the names Elaine and Maria Elena, and you could let those comparisons lead you into the narrator’s habits of mind. Or else you could spend a whole semester reading Denis Johnson, trying to pinpoint the quality of his prose that makes him sound both matter-of-fact and possessed. Or you could dismiss class and send everyone home to read the story again and stare at the wall, because “The Largesse of the Sea Maiden” is great and the questions it raises—like, What difference would it make if Whit could say he loved his wife, or that his daughters were beautiful or clever; or, What kind of fairytale is this—are too big for an English seminar to answer. —Lorin Stein

In Seattle, this year’s AWP is off to a rollicking start: picture 15,000 writers and all their attendant neuroses in one sprawling conference center. Madness! Luckily, no one bats an eye if you take a break to read some newly published poetry; that is, after all, what this thing is about. My first AWP purchase was Caroline Manring’s Manual for Extinction, which soothes the overstimulated soul with its lyrical surrealism and extraordinary formal experimentation. And of course one cannot help but see the mass of writers reflected: “When we are arranged by crop // you can see we are a toothy, / forever naked, rag-tag lot.” —Rachel Abramowitz

I’m jumping on the bandwagon to recommend Silence Once Begun, the fourth novel by Jesse Ball (a past winner of the Plimpton Prize). There’s much to admire in the strangeness and precision of the images, interviews, and text that comprise the book: it’s narrated by a journalist, also named Jesse Ball, who is investigating the Narito Disappearances of 1977, that is, the silent disappearance of eight Japanese men and women from their homes. With its slinking, fragmented structure and its detective work, the novel reminds me of everything from The Wire to The Hamilton Case by Michelle De Kretser, and of Laurent Binet’s metahistorical novel, HHhH. But mostly, it reminds me of nothing else I’ve read before. —Anna Heyward

Jack Spicer is a provocateur; he writes poems that seem to come from someone indelibly wounded. He is capable of profound tenderness, too—in his Collected Poems you can read hundreds of his lines where his voice is violent, cruel, attacking, and then come to “Tell everyone to have guts / Do it yourself / Have guts until the guts / Come through the margins / Clear and pure like love is.” Spicer was always hunting something. This collection is titled My Vocabulary Did This to Me; those were supposedly his dying words. In a poem about Babel, he writes: “It wasn’t the tower at all / it was our words he hated.” —Zack Newick

Like Rachel, I’m in Seattle for AWP—my first time here in fifteen years. After a blur of connecting flights, wrong train lines, and book-fair booths, the only thing I needed was a good sandwich. Luckily, I found my way to Bakeman’s—down a flight of stairs on a sleepy side street, with a sign heralding the best turkey and meatloaf sandwiches in the city. I knew I was in the right place. The sandwich, roasted turkey with a twenty-five cent addition of cranberry sauce, hit the spot, but the real standout was the big slice of blueberry pie, which made me feel right at home in a distant city. —Justin Alvarez

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers