The Paris Review's Blog, page 734

February 24, 2014

Tonight: Jenny Offill in Conversation with Lorin Stein

This evening at seven, join us at McNally Jackson, where our editor, Lorin Stein, will be in conversation with Jenny Offill. Jenny’s excellent new novel, Dept. of Speculation, is out now; Vanity Fair calls it “a startling feat of storytelling—an intense and witty meditation on motherhood, infidelity, and identity, each line a dazzling, perfectly chiseled arrowhead aimed at your heart.” (I hasten to assure you that no arrows, perfectly chiseled or otherwise, will be aimed at anyone at tonight’s reading.)

Jenny’s name should sound familiar: her story “Magic and Dread,” an excerpt from the novel, appears in our Winter issue. If her name doesn’t ring a bell, it probably means you haven’t read our Winter issue—get on that!

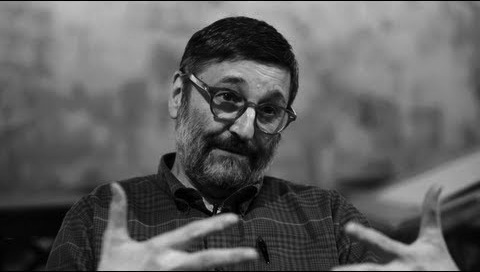

The Physics of Movement: An Interview with Santo Richard Loquasto

A still from BAM’s On Set with Santo Loquasto: The Master Builder, 2013.

Santo Richard Loquasto has a big, easy smile, and an infectious enthusiasm for his work. Since his first production—Sticks and Bones, in 1972—he’s worked on some sixty-one Broadway productions, either as a scenic or costume designer, and often as both. His cunning sets and fanciful costumes have garnered him fifteen Tony Award nominations (he’s won three times), and he’s also won numerous Drama Desk Set Awards for Outstanding Set Design and Outstanding Costume Design. Loquasto is also known for his work in film—most notably with Woody Allen, with whom he’s worked for decades, most recently on Blue Jasmine. One afternoon last summer we met at the Margot Patisserie on the Upper West Side, where Loquasto talked about how he got his start, the demands of designing for dancers, and the downsides of his job.

What got you into costume design?

Well, it just always interested me as a kid. I grew up in Pennsylvania. Mine is the classic story of a teenager in the Poconos, painting summer-stock scenery because that’s what you do there. What I was really interested in was scenery and visuals. I was always creating the mise-en-scène in my backyard. The costumes were always part of it. I was interested in the scenery because in many ways it’s … well, I can’t say it’s more manageable, but it is, of course, because you don’t have to deal with people quite in the same way. People think of me as a costume designer, but in New York, the first things I did were scenery. I did a Sam Shepard one-act play off Broadway in 1970, and then worked for Joe Papp for many years. By that time, I was in grad school at Yale, concentrating on both scenery and costumes. I was designing costumes at Williamstown. When you don’t sew, you’re somewhat intimidated by that aspect of it. You’re lucky if you get to work with amazing people who make the costumes for you and with you.

I just raced from this little shop, Euroco Costumes, where I have the costumes designed for most of my dance projects. It’s two people, Janet Bloor and Werner Kulovitz. She’s brilliant at the stretch issues, and he is an amazing costume-maker of the grand school. Beautiful period cutting. I’ve only known him for about thirty years. You rely on the shorthand that develops between you and also what they bring to it, which is not only their expertise but also their passion. It’s very interesting—normally people who make costumes, who deal with the horrible deadlines and the issues of comfort and the egos of the performers, get sick of it. But I see them get excited by new projects and it’s exhilarating for all of us.

Can you talk to me about designing for Alexei Ratmansky’s The Tempest?

The Tempest you can approach in any number of ways, like most Shakespeare. I did a lot of Shakespeare in the Park in the seventies, both scenery and costumes, and for ten years, I worked in Stratford, Ontario, at the Shakespeare festival. I didn’t do The Tempest there, but I’ve dealt with the play. It was interesting to work with Ratmansky. For him, working on The Tempest is not like, say, Romeo and Juliet, which is so much more of a ballet vocabulary, both because of the great score, which so guides you, and because of his ballet background. Also, everyone knows the story so well. Whereas with our production of The Tempest, there is this much looser Sibelius score.

I follow the play, and I think you have to start there. As an interpreter, you have to follow the progression as Shakespeare laid it out, with your own understanding of where the words aren’t applicable to movement. You understand when Ferdinand and Miranda fall in love. You know what to do. There’s anger and rage and comedy. There was a debate at one point about losing the clowns, Trinculo and Stephano. I quietly fought to keep them. I said, their relationship to Caliban makes for a wonderful scene, and those things are in the structure to give us a breather, so it’s not just this man railing against everything.

Now I want to switch directions for a moment and talk about Woody Allen. You’ve had a very long affiliation with him.

Stardust Memories was our first project. I started out doing costumes for him. I was asked to do a film called Simon that Marshall Brickman, Woody’s collaborator on Annie Hall and Sleepers, wrote and directed. He must have liked working with me, because he recommended me to Woody.

Twenty-seven movies. It’s incomprehensible to me how that all happened and that it has endured. And now I’m doing the musical adaptation of Bullets Over Broadway. I am comfortable calling him on things, and I try to steer. Even though there is such a distinct look to his movies, I don’t let them become hopelessly predictable. Working on Blue Jasmine in San Francisco was certainly fun. I steered him into a rougher neighborhood—there were parts that were cut, unfortunately—where we saw more of some amazing streets, which gave the movie a little more flavor. And, I thought, made the character feel as uncomfortable as Woody did.

A different world than the ballet, which I imagine has very specific kinds of demands.

There are technical demands, certainly, and it’s often a matter of saying, No, actually we can’t let the costumes have so much weight, because even though weight propels … well, the physics of movement is such that you have to make sure a dancer isn’t fighting the weight of a dress.

What do you like best about your job?

My good friends, whom I complain to about things, always say that you like the beginning. You like the search for how you’re going to do it. The fun of Shakespeare and dance is that it’s abstract and yet you have to really reinforce the line of the story. Narrative in dance is difficult, I don’t care what they say, because it can be so cloying in how it’s expressed. Ideally, you don’t just emulate the nineteenth-century devices—I fell in love, my heart’s racing—you want to expand on it and make it more sophisticated. And yet there has to be a frame of visual reference in how you tell the story. Who’s rich, who’s poor, who’s in mourning, who’s evil, who’s good. I was doing Richard III years ago in the Delacorte and I said, Oh, I just want everyone to wear black! And they said, We would never know who was talking! That is the problem.

I love finding the vocabulary, the search for important elements. As I’ve learned from the best of them, you have to stay out of their way. Take Alexei, for instance. We have what I refer to as “the rock” in The Tempest—this black cluster of rocks that kind of emerges into the wreck of the ship and a little cave. Alexei is quite literal in that way. Even though he speaks English perfectly well, it’s nonetheless his second language, and so he wants to convey very specifically what you’re looking at, even though he does quite abstract pieces. I had to get him to trust me about taking things away from him. When you design Shakespeare in a regular ongoing way, you learn how little you need onstage. It’s all there in the language, even if we don’t have the language. We have to rely on a certain familiarity that the public will have.

We talked about what to do with the storm sequence a lot, and I said, We don’t want to use silk. We reviewed how to portray what I call the flaming water—black, shiny, threatening water that sort of envelopes the space. Cutting through it, as I envisioned it, are not only the people who are drowning, but the spirits of the island, who are under the control of Prospero. They are the color of surf, the color of sea glass. Not quite human and yet human. The movement of what they’re wearing will kind of extend the sense of water. In an ideal world, I would’ve designed it using garbage bags, but we couldn’t get them past the fire code.

But you have a different language—the dance language, right?

Yes. It has great emotions—movement. In the seventies, with Baryshnikov and Makarova, you saw the power possible with the classical pieces. Two thousand people can actually be moved to tears when this swan dies? It’s amazing. You know that certain things will just take care of themselves.

And what would you say you like least about your job?

That it is a business. As they say, it’s not called show fun. It’s endless pricing and negotiating. I don’t mean to make money. I mean how much things cost to be made, how many you need. Whether it’s costumes or scenery—how much do those cost? How it breaks apart and goes together. The technical part of it is fascinating, but the haggling does wear you out. And producers will say, Oh, we don’t want you to cut things, we just want you to do it for less. Sometimes you can. Sometimes that’s almost fun. But it wears you out ultimately, and it’s everywhere. It’s not just in institutions, it’s on Broadway. It can be brutal on Broadway, because you often feel as though you’re dealing with people who could care less. I have had management over the years say, I don’t want the birch trees, you want the birch trees. I don’t care if they’re there. It’s nice when they at least say, Oh, it’s beautiful and we really hope we can have as much of that as possible, but we don’t have much money. At least you feel that they looked at it. There are certain general managers who I’m certain would deliberately not come to any of the presentations because they don’t what the production can really look like.

Recapping Dante: Canto 18, or Beware the Bolognese

Sandro Botticelli, Canto XVIII, colored drawing on parchment, c. 1480

Canto 18 is perhaps the unsung workhorse of the Inferno—at only 136 lines, it is filled to the brim with political commentary, mythology, personal attacks, and feces. There’s a distinct energy in the way this canto is written; even the obligatory geographical descriptions feel alive, and Dante, when he sets the scene, uses the word new: new suffering, “new torments,” “new scourgers.” In short, this is a sort of broad-spectrum dis track that deals with two different kinds of sinners: the panderers/seducers and the flatterers.

After Dante and Virgil get off Geryon’s back, they end up in the eighth circle of hell. (The seventh really dragged on, didn’t it?) This is Malebolge, where sinners are made to run through a series of ditches; if they slow down, demons descend to flog them. As grim as this might sound—running naked through a ditch in hell, being whipped by demons—Dante uses the occasion to showcase his wit. “How they made them pick their heels up / at the first stroke! You may be certain no one waited for a second or a third.”

Dante meets Venedico of Bologna—a sinner, and as such, not exactly a model human being. (He sold off his sister.) Venedico identifies himself and his fellow Bolognese as those who use the word sipa to mean yes in their dialect. (Dante frequently uses this sort of indirect revelation, especially when it comes to hometowns. Francesca, for example, doesn’t say she is from Rimini, but she says she is from where the river Po slows down. Using a linguistic idiosyncrasy as a form of ID is classic Dante.) Venedico’s words suggest this is precisely the sort of thing one can expect from a Bolognese: “I’m not the only Bolognese here … this place is so crammed with them,” he says.

Dante scurries over to Jason, a sinner marching nobly through the pain. Jason traveled to Lemnos, home to a bunch of unattached women—unattached because they’d murdered their husbands—and then he seduced one of them and left her when she was pregnant. Dante judges Jason, but I’d like to see him stick around after accidentally impregnating a murderer.

Finally, Dante shifts his focus to the other ditch: this one’s for the flatterers, who are smeared in shit and busy devouring it. I’m sure scholars have debated, and may be presently debating, whether Dante means to suggest that flatterers are full of shit or that they are shit-eaters. My personal verdict? Both.

Dante recognizes one of the sinners through the veil of crap—in case there was any ambiguity regarding Dante’s feelings about the church, he even notes that the sinner is so ridiculously lathered in feces that it’s hard to tell if he’s a priest or a layperson. As it turns out, the sinner is Alessio Interminei of Lucca, a noble member of the White Guelph party, whom Dante apparently found worthy of direct attack.

Writing canto 18, one can only imagine, must have offered some form catharsis. Dante is unabashed and unreserved. And indeed, the poetry here is remarkable, and the story full of lessons: namely, never trust anyone from Bologna.

Movie Novelization Is a Dying Art, and Other News

The portraits of Carl Van Vechten: Henri Matisse, Gertrude Stein, Theodore Dreiser, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and more.

“Even when he’s dead, as he is for much of the book, we feel that he’s still hovering right next to us, closer to us than our own clothes.” On grief, parallel universes, and Paul Murray’s Skippy Dies.

“When you want a science fiction movie adapted into a novel that might be better than the original source material, you don’t fuck around. You speed dial Alan Dean Foster and send the check pronto.” The lost art of movie novelization. (Among the stranger films to become novels: Taxi Driver, Young Frankenstein, Deep Throat .)

Attention, surrealist novelists in search of a conceit: a town in Holland has designed a village made exclusively for people with dementia.

Or you can start your day with leather and handcuffs: Robert Mapplethorpe’s early Polaroids are here for you.

February 21, 2014

What We’re Loving: NASCAR, Nukes, Nobility

From the cover of Elaine Scarry’s Thermonuclear Monarchy.

When I discovered the work of Elaine Scarry in college, I remember thinking that her name was somehow bound up in her field of study—one had informed the other. She has a new book out, and the connection has never seemed more apt. Thermonuclear Monarchy is a badass title and a frightening one. The book is 640 pages, so I haven’t read it—it could be a while before I have that much time—but I have been reading about it. Nathan Schneider’s essay at The Chronicle of Higher Education is the best read. Scarry is a broad thinker, pulling from unusual corners of politics, history, and culture (including, Schneider notes, “the town where [Thomas] Hobbes grew up, a mistranslation of the Iliad, marriage, CPR, the Swiss nuclear-shelter system”). Thermonuclear Monarchy, then, is “less an argument that nuclear weapons should be eliminated, or how, than an entire worldview in which they have no rightful place.” —Nicole Rudick

We all know him as The Paris Review’s trusty third baseman (“Wisdom” and “Chaos Mode” are just two of his on-the-field nicknames), but it turns out that Ben Wizner occasionally gets around to other things, too—such as serving as the legal advisor to, um, Edward Snowden. (Yeah, NBD.) Listen here as he and Daniel Ellsberg argue in favor of the motion “Edward Snowden Was Justified” in a debate against Andrew C. McCarthy and R. James Woolsey. (Really, listen—it’s riveting.) —Stephen Hiltner

Our forthcoming Art of Nonfiction interview with the British psychoanalyst and author Adam Phillips is full of literary reminiscences and references to books that have meant something to Phillips over the course of his life. One in particular has stuck with me over the past few weeks, a Randall Jarrell quote from “A Girl in a Library”: “The ways we miss our lives are life.” Happily, it has reminded me to return to Jarrell’s The Animal Family, which I started a few months ago and put down for no good reason. (I don’t even have the excuse of length—it’s a children’s chapter book). Through the simple story of a woodsman who gathers together members of various species—real and imagined—to form an unconventional family, Randall touches on death, love, the pain of being alone, the strangeness of taste, the joys of language, and the terrifying calm of the wilderness. It is a lesson in what plain words thoughtfully said can evoke, perhaps the best such lesson I’ve ever read in prose. My edition, and I think most others, includes beautiful Maurice Sendak illustrations that are, for Sendak, unusually pastoral—not a figural representation in the lot—and add much to Jarrell’s story. —Clare Fentress

NASCAR was incorporated on this day in 1948—exactly one hundred years after the first publication of The Communist Manifesto. (Would that their similarities didn’t end there.) On such a storied anniversary, an educated citizen has two duties. First, reread your Marx and Engels—now’s as good a time as any to hone your critique of capitalism. Second, visit—or revisit—the thrilling world of NASCAR romance novels. Bonus points if you’re somehow able to combine these pursuits, e.g., by writing a book that’s both a critique of capitalism and a NASCAR romance. —Dan Piepenbring

For no reason other than it was given to me, and I was taking a long flight, I’ve been reading Ivan Goncharev’s Oblomov, a nineteenth-century Russian novel that had heretofore eluded my grasp. The title character, who has been called “the laziest man in literature” and answers “No!” to Hamlet’s big question, is incapable of making any decision or taking any decisive action. His life and his attempts to get anything done become a satire of the Russian nobility of the day—but the novel will also comfort anyone who doesn’t feel like getting out of bed on a winter’s morning. That’s a serious philosophical affliction. —Anna Heyward

Sunday, despite the Bangles song, is most decidedly not my fun day. (Laundry! Litter box! Ineludible Monday!) But from eleven A.B. to twelve P.B. EST, I get to relax and tune in to the brilliant Alexandra Manglis on Cyprus’s online MyCyRadio. Manglis’s show, “Spinning Global Yarns,” weaves together international literature, music, and even archaeology, from Charlotte’s Web to Scheherazade, Beyonce to Yma Sumac, prehistoric Venus statuettes to ancient shipwrecks. If Sunday finds you out and about, you can listen to the recorded podcasts of that week’s show. —Rachel Abramowitz

I grew up in Madras, India, notable for its dosas and for the images of politicians splayed on its every public wall. I think negative space might make Indians uncomfortable, so the walls are as crowded as the streets. The latest street art trend concerns Jayalalithaa, one of two politicians among between whom the state of Tamil Nadu has been tossed like a hot potato for the past three decades. Rumor has it Jayalalitha is a lesbian; urban legend says she once swallowed an entire cow. She’s a big-boned lady, and of late, her face is ubiquitous in street posters; her image can’t help but go unregulated. In other words, she was born to be Tumblr-ed, and now here she is, watching you. —Nikkitha Bakshani

Instant Happy Woman

Paul Albert Besnard, Morphinomanes ou le plumet, 1887. Image via the Hammer Museum.

The Hammer Museum, in LA, is currently showing an exhibition titled “Tea and Morphine: Women in Paris, 1880 to 1914.” The juxtaposition of the two substances is deliberate; the show aims to present what the curators call “a multidimensional portrait of the Parisian woman at the turn of the century, spanning from the frilly collars of the upper class to the dirty syringes of the desperately poor.” All of this is represented by some of the great artists of the day in a series of arresting engravings, paintings, and lithographs. (Occasional bits of ephemera—and books like Les morphinées—round out the show.)

By definition, the portrayals run the gamut from civilized—George Bottini’s graceful fin de siècle women shopping or walking down Parisian boulevards—to depraved. But even the most abject addict is glossed with romance. The renderings, whether they be stylized art nouveau commercial work or a Bonnard etching, are so achingly beautiful as to provide a sense of continuity. All these women, whatever they were drinking, were muses.

And the show is at pains, via notes and curation, to make it clear that one substance was not synonymous with only one group of subjects; monied women frequently resorted to morphine in the nineteenth century, to the point where their widespread drug use became a problem. Meanwhile, even when yielding acid, or injecting morphine, the demimondaine is rendered with the same beauty and care, avenging goddesses and righteous furies. (Which is all very well, if you were a Parisian prostitute.) As Proust—no stranger to morphine himself—would have it, “The paradoxes of today are the prejudices of tomorrow, since the most benighted and the most deplorable prejudices have had their moment of novelty when fashion lent them its fragile grace.” That women numbing themselves was so pervasive a theme is both scary and illuminating.

But here is the thing. Shortly after studying the images in this exhibition, I took a walk and saw this:

Too easy, I think, to say plus ça change. But barely.

Postcard from California

Paul Albert Besnard, Morphinomanes ou le plumet, 1887. Image via the Hammer Museum.

The Hammer Museum, in LA, is currently showing an exhibition titled “Tea and Morphine: Women in Paris, 1880 to 1914.” The juxtaposition of the two substances is deliberate; the show aims to present what the curators call “a multidimensional portrait of the Parisian woman at the turn of the century, spanning from the frilly collars of the upper class to the dirty syringes of the desperately poor.” All of this is represented by some of the great artists of the day in a series of arresting engravings, paintings, and lithographs. (Occasional bits of ephemera—and books like Les morphinées—round out the show.)

By definition, the portrayals run the gamut from civilized—George Bottini’s graceful fin de siècle women shopping or walking down Parisian boulevards—to depraved. But even the most abject addict is glossed with romance. The renderings, whether they be stylized art nouveau commercial work or a Bonnard etching, are so achingly beautiful as to provide a sense of continuity. All these women, whatever they were drinking, were muses.

And the show is at pains, via notes and curation, to make it clear that one substance was not synonymous with only one group of subjects; monied women frequently resorted to morphine in the nineteenth century, to the point where their widespread drug use became a problem. Meanwhile, even when yielding acid, or injecting morphine, the demimondaine is rendered with the same beauty and care, avenging goddesses and righteous furies. (Which is all very well, if you were a Parisian prostitute.) As Proust—no stranger to morphine himself—would have it, “The paradoxes of today are the prejudices of tomorrow, since the most benighted and the most deplorable prejudices have had their moment of novelty when fashion lent them its fragile grace.” That women numbing themselves was so pervasive a theme is both scary and illuminating.

But here is the thing. Shortly after studying the images in this exhibition, I took a walk and saw this:

Too easy, I think, to say plus ça change. But barely.

An Urgent Message

Bob Adelman, An Urgent Message, Washington, DC, 1963, Courtesy of the Photographer

Bob Adelman, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Coretta Scott King Outside Montgomery on the Fourth Day of the March, Alabama Route 80, 1965, Courtesy of the Photographer

Bob Adelman, CORE Worker Mimi Feingold and Local Residents Singing at the End of the Day, St. Francisville, West Feliciana Parish, LA, 1963, Courtesy of the Photographer

Bob Adelman, On the Frosted Window of a Freedom Ride Bus Between New York and Washington, DC, 1961, Gelatin silver print, Courtesy of the Photographer

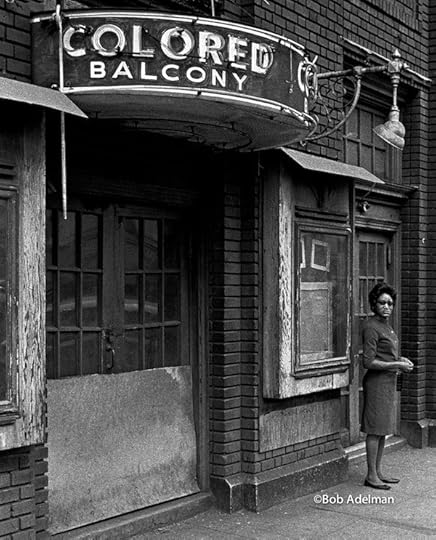

Bob Adelman, Segregated Movie Theater, Birmingham, AL, 1963, Gelatin silver print, Courtesy of the Photographer

Bob Adelman, Marcher with Flag, Alabama Route 80, 1965, Digital c-print, Courtesy of the Photographer

Bob Adelman, Nighttime Demonstration in Support of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, with

Images of Slain Civil Rights Workers Schwerner, Chaney, and Goodman, Atlantic City, NJ, 1964, gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the photographer.

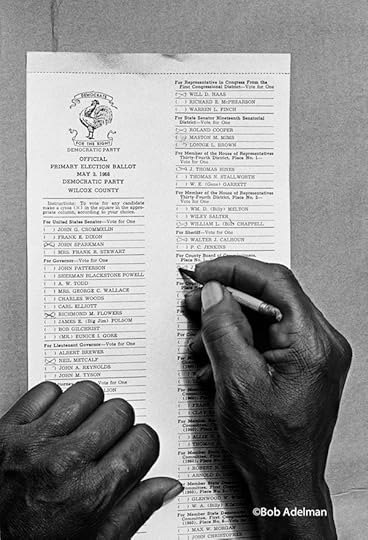

Bob Adelman, Marking a Ballot, Camden, AL, 1966, gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the photographer.

Bob Adelman, CORE Volunteer Helping an Older Woman Learn to Fill Out a Voter Registration Form, East Feliciana Parish, LA, 1963, gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the photographer.

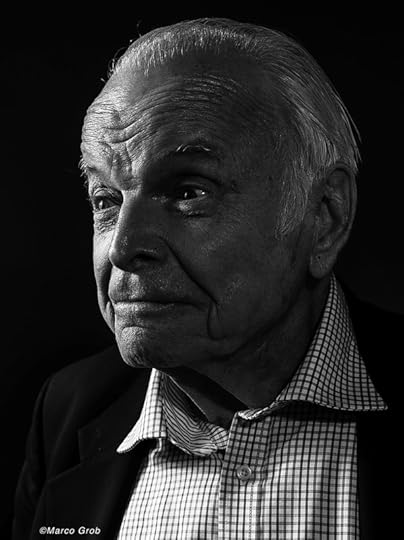

Marco Grob, Bob Adelman.

Bob Adelman’s amazing photographs—the majority of them black-and-white prints—fill the second floor of the Museum of Art in Fort Lauderdale, where they will be on display until May 17. He photographed what came to be significant moments in the civil rights movement as they were happening. As a photographer for CORE, SNCC, Life magazine, and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, he was on the scene for moments both momentous and not, to photograph Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. and also never-to-be-famous individuals, families, children—people we wouldn’t have seen again, had Adelman not been there to show them on the sidelines as well as in the forefront, their eyes their own camera lenses, looking back; exiting “White Men Only” bathrooms at the courthouse in Clinton, Louisiana; and then kids who climbed up in a tree to view the memorial service of Dr. King, attended by Robert Kennedy (what a portrait of grief), who’d be dead himself only months later. As a documentary photographer, nothing stopped Bob. It was dangerous work, as was pointed out by one of the speakers at the January 19 museum opening, but Bob found inequality inexplicable and insupportable. In his college years, he studied philosophy to try to figure out the point of being alive. In the civil rights movement, he found his answer.

Don’t miss (not that you could) the enormous enlargement of the contact sheet from when Bob was first focusing on the police’s attempt to blast away protestors in Birmingham by aiming fire hoses at them. It gives you a chance to see the photographer’s mind at work, frame after frame, and is unforgettable as an image, the people holding hands, some with their hats not yet knocked off, in Kelly Ingram Park, struggling to remain upright in the blast, a fierce, watery tornado that obliterates the sky as it seems to become a simultaneously beautiful and malicious backdrop that obliterates the world. The large photograph in the museum took two days to print. Dr. King, upon first seeing Bob’s photograph: “I am startled that out of so much pain some beauty came.”

Ann Beattie’s story “Janus” was included in John Updike’s The Best American Short Stories of the Century.

Prizes Make Books Less Popular, and Other News

“Is the goal so far away? / Far, how far no tongue can say, / Let us dream our dream today.” The worst poems by canonical writers. (Those lines are Tennyson’s—not his finest hour.)

On the commercialization of nostalgia: “The memorial-industrial complex ensures that our past—our collective past—permeates our present.”

How did Jeopardy! get its strange the-question-is-the-answer format? It was Merv Griffin’s doing.

Aspiring writers: better to toil in obscurity. Studies show that literary prizes make books less popular. “Winning a prestigious prize in the literary world seems to go hand-in-hand with a particularly sharp reduction in ratings of perceived quality.”

New behind-the-scenes footage from Full Metal Jacket shows Kubrick’s perfectionism in full force; “He labors to get just the right spacing between lime-covered actors playing corpses in an open grave.”

Blunders—they’re a good thing!

February 20, 2014

Learn to Figure Skate the Old-Fashioned Way

Frontispiece from A System of Figure-Skating

If you’re like me, the Olympics have borne in you one mighty, overriding desire: to become a strapping world-class professional figure-skater. Well, we’re in luck, every one of us. Thanks to the glut of teaching materials available in the public domain, dazzling one’s peers in the rink and taking home the gold has never been easier.

As a starting point, consult an invaluable volume from 1897: T. Maxwell Witham’s A System of Figure-Skating: Being the Theory and Practice of the Art as Developed in England, with a Glance at its Origin and History. In sporting matters, Witham was no slouch—the title page notes that he was a “Member of The Skating Club.” Which skating club, you ask? Well, let me answer your question with a question: How many skating clubs do you belong to?

With verve and good humor, A System of Figure-Skating will teach you such cherished and essential maneuvers as “the Jagendorf dance,” “the Mercury scud,” “the spread-eagle grape vine,” “the sideways attitude of edges,” and—of course—the “United Shamrock.” Confused? You needn’t be. The System offers detailed instructions every step of the way. Here’s an edifying bit about how to conduct the “outside edge forwards”: “We have also to bring into the more important action the hitherto unemployed leg, which must be gently and evenly swung round the employed one in such a manner that it arrives exactly at the proper time and angle to be put down, and so become the traveling one.”

See? You’ll be getting the hang of things in no time!

If all else fails, the System is meticulously illustrated—its dozens of diagrams and charts make even complicated performances seem rudimentary. Even a trained dog could follow these instructions:

Oh, now I get it!

The System also includes an expansive history of the sport, which begins, “Geologists tell us that the earth was formed under great heat, and that it is gradually cooling down—decidedly a cheering prospect for future skaters.” And lest you think that the Olympic village is beyond your aged reach, Witham includes a stirring aside: “A relation of mine, who did not put on a pair of skates until he was thirty years of age, became, by dint of perseverance, a very fair figure-skater.”

Inspiring.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers