The Paris Review's Blog, page 738

February 13, 2014

The Silent Treatment

On Art Spiegelman’s new stage show, Wordless!

Photo: Robert Kozloff/The University of Chicago

In 1970, when Art Spiegelman was twenty-two, he went to a gallery opening in Binghamton, New York, for an exhibition of woodcuts by Lynd Ward. Spiegelman wanted to tell Ward how much he admired the wordless novels the artist had made in the 1930s, but also, and no less importantly, he wanted to ask him what his favorite comic books were. The way Spiegelman tells it, the sixty-five-year-old Ward was gracious but confused: he didn’t know much about comics; his Methodist minister father had forbidden them. Ward’s woodcut novels, which blended Depression-era social realism with a Faustian sense of good and evil, owed more to the biblical engravings of Gustave Doré than they did to the Sunday funnies. Spiegelman didn’t get the comics talk he came for, but he spent some time in the gallery, studying those prints. Two years later, he composed a four-page comic about his guilt over his mother’s suicide. It was just a few panels, but their startling intimacy set the pattern for much of his later work, including the Pulitzer Prize–winning Maus, in which they were later included. Spiegelman titled that short comic “Prisoner on the Hell Planet,” and in its stark style and pitch-black outlook, you can see the influence of Ward’s woodcuts.

Spiegelman has given Ward’s novels a central role in Wordless!, the new stage show he created with the composer Phillip Johnston, and which the two men presented twice last Saturday to sold-out crowds at the University of Chicago’s Logan Center for the Arts. Wordless! weaves together Spiegelman’s reflections on the history of wordless novels with slide show projections of the genre’s classic works, which Johnston and his sextet accompany with rollicking, klezmer-inflected, vaudeville jazz. The back-and-forth between lecture and performance neatly captured Spiegelman’s ambivalence about his role on stage. On the one hand, he was a comic artist on a mission, there to add a new branch to the family tree of the graphic novel, one that would demonstrate the genre’s deep roots and help solidify its place in the canon of “real literature.” Mostly though, Spiegelman was having fun. He was there to give the crowd what he had sought from Ward: a conversation about some of his favorite comics and a taste of the overwhelming pleasure they give him. “Don’t worry if you get a little lost while you’re watching,” he reassured his listeners between puffs on his e-cigarette. “I’m hoping you will careen between my words and these picture stories until you’re left as breathlessly unbalanced as I am.”

Spiegelman started the night by reviewing the ongoing debate about comics’ literary value. They’ve long borne the reputation of being a lowbrow craft, but battle lines were drawn in 1954, when the psychologist Fredrick Wertham published the minor best seller Seduction of the Innocent, arguing that violent imagery and subversive messages in comics led to juvenile delinquency. Comics were subject to mass burnings, and a congressional inquiry—“kind of the Grand Theft Auto of their day,” as Spiegelman put it. Intense self-censorship by major publishers soon polarized comics between the sanitized fare of grocery-store checkout aisles and an underground scene that reveled in transgression. Neither side got much respect in literary circles.

Photo: Robert Kozloff/The University of Chicago

Underneath the culture wars were fundamental questions about how words and pictures could and should be used. Spiegelman cites the Enlightenment critic Gotthold Lessing’s 1766 treatise Laocöon; Or, the Limits of Poetry and Painting as a good summary of the kind of thinking that relegated comics to the bottom of the artistic totem pole. In a nutshell, Lessing argued that words are meant to weave narratives in time, images are meant to capture likenesses in space, and that poets and painters should stick to their guns; he would have hated thought bubbles. In our postmodern era, Lessing’s theory has been flipped on its head. The genre-bending qualities that previously condemned comics to the bonfire are now widely celebrated by academics and critics as uniquely apt for making sense of an uncertain world. Once considered corrupted hybrids of purer forms, comics now claim proximity to a kind of fundamental language. “Picture stories ask us to make meaning out of abstractions, using both sides of our brain, and as you focus on and decode the images, you’re left with that holy-shit flash of recognition as the pictures take on meaning,” Spiegelman told the crowd. “Comics mimic the way the brain works, and can therefore explore the mysteries of capital-A Art.” Sure enough, the cultural tides turned in the 1980s, as ambitious works like Maus earned critical respect, and started to go by the name “graphic novels” (“so they could pass for white,” Spiegelman quipped). Comics’ parvenu status as high literature allows a revision of their lowbrow history, and that’s where the wordless novels come in. “I’ve been called the father of the graphic novel,” Spiegelman said. “But I’m here tonight to demand a paternity test.”

Several of the wordless picture stories Spiegelman presented were clearly comics—pages from Mad magazine, panels by the early English cartoonist H. M. Bateman, scenes from Milt Gross’s slapstick He Done Her Wrong—but he spent most of his time tracing the less obvious relationship between graphic novels and wordless woodcut novels, a genre that originated with the Flemish artist Frans Masereel. Trained as a woodcutter just in time for the technique to become commercially obsolete, Masereel followed it into art and created more than twenty wordless novels. His 1919 book A Passionate Journey was particularly influential—Thomas Mann once called it his favorite film. In it, we follow a naive, Chaplin-esque everyman through a huge city, dropping in and out of the lives of strangers: nursing a dying woman, farting on a group of businessmen, falling in and out of love with a prostitute. Masereel’s books showed a thrilling world, at once intimate and expansive, and they laid the way for many emulators, Lynd Ward among them.

Wordless woodcut novels showed Spiegelman that pictures could do justice to the serious stories he had to tell. “I needed to graft the high and low branches of my family tree together to climb out of the prison of little boxes that defined my medium,” he explained after a projection of Ward’s work. The grafting was in part stylistic; the black-and-white panels of Maus are closer in style to Ward’s woodcuts than they are to, say, Mad covers. But Spiegelman didn’t go out and make wordless novels. “Those might be appropriate for more universal stories, and this one was sorta personal,” he said, of creating the panels of “Hell Planet.” Spiegelman didn’t say directly how woodcut novels influenced his approach to storytelling, but they seem to have played a critical role. His great innovation has been to harness the flexible boundaries of the comics form for metanarrative; he is a master at communicating an unrepresentable level of pain by sidestepping traumatic events, and instead telling the story of the struggle to represent them. Maus is about Spiegelman’s father’s suffering during the Holocaust, but before that it is about Spiegelman’s own struggle to relate to his father’s past through comics. Maus is successful in large part because it doesn’t approach the Holocaust directly, but through ciphers—animal masks, memory, family relationships—that break up the horror into smaller moments. Words, too, are a kind of cipher in Maus and are often used less to create meaning than to mute it, thereby allowing a greater proximity to a subject that would otherwise be too painful. The father-son bickering and anxious internal monologues don’t add to the intensity of the Holocaust memory—they subtract just enough from it to make it comprehensible. Ironic distance is Spiegelman’s path to intimacy, so after his time with Ward, he didn’t make a wordless novel; he made comics in which nearly everything that matters is left unsaid.

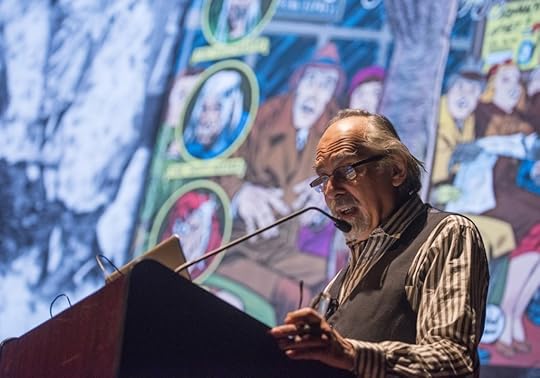

Photo: Robert Kozloff/The University of Chicago

This same principle shows up in the structure of Wordless! Spiegelman revels in decoding the rich tensions of picture stories, but he sidesteps the huge contradiction of the show itself: he tells the crowd about the beauty of wordless novels, but the projections he shows in the interludes are not wordless novels at all. Set to Johnston’s jazz and animated by a panning camera, the sequences have a new visual character, and a new sense of time. They effectively become silent films. Spiegelman acknowledges the irony only briefly, at the end of his show: “Making Wordless! has been a bit like taking sausages and turning them back into pigs,” adding, “We’ve tried to make our pigs dance without violating their true nature.” Most of the time it feels like the audience is doing the dancing, careening between images, sounds, and words, trying to keep up with slides, appreciate music, follow arguments. Decoding comics, it seems, isn’t ultimately what Spiegelman is after. To figure them out entirely would kill their magic.

Even as he makes the case for comics as an original language of human thought, Spiegelman delights in undermining stuffy theory, letting Johnston’s music burst in to express his joy on seeing the stories that flash before us. He believes in the universal power of comics—“an Esperanto understood beyond the borders of language”—but to insist on universality, to claim an objective, disinterested authority uninhibited by pleasure, would be dishonest, presumptuous, and not nearly as much fun. So instead of explicating the play between words and images, Spiegelman creates mystery in the play between his lecture and Johnston’s music. It’s disorienting, but as he warned us at the beginning, that’s part of the point.

After the last horn blasted and the cymbals faded, his listeners in the auditorium roared applause, dazed but appreciative. Some were academics studying comics, and several were comic artists themselves. And many others were twenty-two.

In A Passionate Journey, Masereel took a line from Walt Whitman as his epigraph. It works for Wordless! just as well:

Behold! I do not give lectures, or a little charity:

When I give, I give myself.

Harry Backlund is a writer living in Chicago and the publisher of the South Side Weekly.

Noodles and Mush

A valiant mascot shovels snow outside the Nissin Cup Noodles Museum in Yokohama.

All my life I ate noodles. Because my mother used to repair old lacework. And one thing about old lace is that odors stick to it forever. And you can’t deliver smelly lace! So what didn’t smell? Noodles. I’ve eaten basinfuls of noodles. My mother made noodles by the basinful. Boiled noodles, oh, yes, yes, all my youth, noodles and mush.

—Louis-Ferdinand Céline, the Art of Fiction No. 33

There’s Not an App for That, and Other News

Do you really want to write like this guy, anyway?

The last thing the world needs is another Hemingway imitator, but a new app purports to help you write like Ernest Hemingway. It lops off adverbs and corrects instances of passive voice, but “it’s pretty tricky to distill instructions into computer code and make a machine into an editor.” Phew. Job security.

Why are writers such inveterate procrastinators? “We were too good in English class.”

Another question: Why do literary biographers insist on portraying “a positive moral image” of their subjects, many of whom were ethically lax?

. There will be blood. And bruised egos. And bold Mediterranean recipes.

An 1882 pamphlet—“The Nonsense of It!”—sunders the flimsy arguments against giving women the vote. “‘The polls are not decent places for women at present.’ Then she is certainly needed there to make them decent … the presence of one woman would be worth a dozen policemen.”

February 12, 2014

Common Language

Photo: Konstmat, via Flickr

During my junior year of college, I had the chance to study at a university in London. I flew out of JFK on September 15, 2001, and the flight was so empty I was able to lie down across four seats for the first and last time in my life. In England, many of our fellow students seemed to feel obliged to either ask solicitously about our 9/11 experiences, or express their views on American imperialism. In both capacities, I felt I proved a disappointment.

During that year abroad, my American friend Rachel and I became fascinated with a group of fellow literature students who seemed to us unspeakably wonderful. They never said anything in seminar, they always looked glamorously ridiculous, and, best of all, their company was highly exclusive.

We came up with names for all of them. There was the seeming leader, “Robert Smith,” who had sculptural, Cure-like hair. “Charles and Camilla Macaulay” looked a bit alike—in fact, the whole crew struck us as very Secret History-esque. We called one tall, severe boy “Adam Bede”; one emaciated fellow was “Schiele”; another, I’m sorry to say, was just “the Balding One.”

They moved in a pack, smoked roll-ups in a secretive cluster, exchanged notes and amused eye contact during class, and cohabited, or so we assumed. The clique seemed to us all things not-American. It shamed us to think that they associated us with the Boston girl who was always shouting loud, obvious things about Sylvia Plath or the sleazy Arizona boy who hit on all the prettiest girls. We were desperate to prove our worth to them, but how? The only person outside their circle with whom we’d ever seen them associate was a studious, translucently fair young man named Rupert Davies.

For weeks, Rachel and I watched the group from afar, talking about them an unhealthy amount, like teenagers with an obsessive crush. We pretended our interest was ironic. We both knew the truth. Where did they go? What did they do? Whatever it was, it was obviously much cooler than what we were doing, which, in my case, was eating at the Indian YMCA every night in the old man cardigan that was my ill-considered uniform.

One evening, at the department Christmas party, something momentous happened. Rachel and the Balding One danced together—sort of—for the entirety of a Grease medley. But they were all very drunk. Lots of people were, besides the abstemious Rupert Davies, who did not dance. And the next day they went back to ignoring us.

Several weeks later, Rachel and I were sitting in the student union when the entire pack of them came in. They seated themselves at the next table and their conversation was wholly audible. Talk had turned to Rupert Davies; it seemed he was not, in fact, a member of their circle at all, because they were mocking him.

“I have often wondered,” said Camilla Macaulay, “whether he bleached his eyelashes.”

“Oh, come now, he’s an albino,” said Robert Smith impatiently.

Then, magically, he turned to us. “Rupert Davies.” he stated. “Albino?”

We fell all over ourselves in our desire to please. Oh yes, we said. Albino. Definitely an albino. Clearly an albino. Absolutely.

“It would explain a great deal,” said Schiele, somewhat obscurely.

Rachel and I stood the next two rounds. Obviously we did. We learned their names. They offered us cigarettes. We hardly dared look at each other for the elation.

“The Americans this year,” said Camilla, whose name was Kate. “Do you know many of them?”

Oh, no, we said. They were awful, appalling, embarrassing, we had nothing to do with them.

The evening wore on; it was last call.

After what appeared to be some silent communication amongst the others, Robert Smith—whose name was Gareth—turned to us. “Would you like to come to our after-hours?” he asked.

We trudged for what felt like a very long time to an unprepossessing street. But we were walking on air; we were about to be admitted to the inner sanctum, to a place that was surely so cool, so exclusive, that no other American had ever been extended the privilege of entry. We were, we both felt, now in that exclusive fraternity of the acceptable inhabited by T. S. Eliot and Henry James.

“Here we are,” said Charles, whose name was James. We descended some steps and there we were.

It was a twenty-four-hour snooker parlor.

“Who’s buying?” said Arthur, formerly known as the Balding One, looking at us expectantly.

“I will,” I said somewhat reluctantly. After a moment. “What would people like?”

“Smirnoff Ice,” said Robert Smith. “It’s what we all drink.” I waited another moment to ascertain whether he was joking; he was not. I tried to decide whether this was awesome. I was beginning to suspect otherwise.

The twenty-four-hour snooker parlor was brightly lit and stuffy.

“So, do you play?” I asked after yet another moment of silence as I absorbed the shock of my first-ever Smirnoff Ice. (Berry.)

“Oh no,” said Arthur. “We just come here. Every night.”

“Oh,” said Rachel.

“Well, not every night,” said Kate, leaning in. “Some nights …” she lowered her voice as if about to reveal a delicious piece of gossip. “Some nights we go to mine and we work out the harmonies for Beach Boys songs. A cappella.”

“That’s the only reason to bother with that albino Rupert Davies,” said Robert Smith/Gareth. “In fairness, the man is very good on the high harmonies.”

“Would you like to join us some night?” said Arthur eagerly.

“Uh, maybe,” I hedged.

“‘Sloop John B’ is our best, probably,” said James, or whatever his name was.

“There’s something I’d like to ask you,” said Kate, “but I don’t want to overstep.”

“Sure, anything,” said Rachel.

“Well… ” she said. “Where were you on 9/11?”

* * *

We never saw them again after the Night the Magic Died. We made other friends, good friends, and the year went on. It turned out they were right about one thing: Rupert Davies had a really beautiful voice. He wasn’t, incidentally, an albino.

Get Ready to Revel

Just when you thought you couldn’t wish for spring any more fervently, news arrives of our Spring Revel. Save the date: on Tuesday, April 8, writers, poets, artists, editors, readers, supporters, eminences, patrons of the arts, bon vivants, and other all-around admirable sorts will convene at Cipriani 42nd Street for a legendary evening. Women’s Wear Daily calls the Revel “the best party in town”; Mary Karr calls it “prom for New York intellectuals.”

This year, we’ll honor Frederick Seidel with the Hadada Award, to be presented by John Jeremiah Sullivan. Lydia Davis will present the Plimpton Prize for Fiction; Roz Chast will present the Terry Southern Prize for Humor; and Martin Amis, Charlotte Rampling, and Zadie Smith will all read. There will be dinner, and cocktails, and unabated merriment, thanks in no small part to our event chairs, Chris Weitz and Mercedes Martinez.

We’d love to see you there! Tickets and tables are available now.

River of Fundament

Matthew Barney’s singular new film.

Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler, River of Fundament: Ren, 2014, Production Still. Photo: Chris Winget. © Matthew Barney.

Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler, River of Fundament, 2014, Production Still. Photo: David Regen. © Matthew Barney.

Matthew Barney, Djed, 2009-2011, Cast iron and graphite block, 20 1/4 x 406 x 399 inches (50.2 x 1031.2 x 1013.5 cm). Photo: David Regen. © Matthew Barney.

Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler, River of Fundament: Khu, 2014, Production Still. Photo: Hugo Glendinning. © Matthew Barney.

Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler, River of Fundament: Khu, 2014, Production Still. Photo: Hugo Glendinning. © Matthew Barney.

Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler, River of Fundament, 2014, Production Still. Photo: Keith Riley. © Matthew Barney.

Matthew Barney’s studio, the birthing place of some of the biggest and most ambitious art of our time, sits in an industrial New York netherzone by the East River in Queens. A couple blocks down is a garage for cast-off food carts in states of obliteration and disarray. On the streets stroll workers whose sturdy coats solicit calls to 888-WASTEOIL, for the service of all waste-oil wants and needs. Alongside the studio the mercurial river flows, its current changing direction several times a day.

Inside are forklifts to move things like six-ton blocks of salt and sculpturally abetted Trans Ams. Football jerseys hang on a wall, including one for the fabled Oakland Raiders center Jim Otto (his number, 00, puts Barney in mind of extra-bodily orifices). A staff of a half dozen studio hands oversees projects of enterprising kinds, from building and bracing large architectural oddities to disrupting and destroying sculptures and letting objects rot.

It was here that Barney completed River of Fundament, a new epic film project premiering this week at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, with a running time of nearly six hours (including two intermissions) and passages that play as extravagantly abstracted and absurd. The film was inspired by Norman Mailer’s 1983 novel, Ancient Evenings, set in ancient Egypt and invested in stages of reincarnation that come after death. The story would not seem to be eminently filmable.

But River of Fundament is not exactly a film. It draws on a series of site-specific performances and elaborate happenings—live actions related to the project date back as far as 2007—and all of them, however cinematically presented in the end, fit as sensibly within the traditions of theater and opera. Shoots lasted for days, doubling as rituals or séances, with characters performing for an audience that would come to be part of the work.

“I really was not in the mood at that point to make a film,” Barney says of the earliest stages of the project. “That’s not where my head was.” Instead, after an eight-year period devoted to directing films for his phantasmagorical Cremaster Cycle, Barney conceived River of Fundament as a premise for more immediate experiments and events to be presented on stage. The first was a performance at his studio that later went public, in 2007, at the Manchester Opera House.

“I don’t have much of a relationship with opera,” Barney says, “but I’m interested in opera houses, the way organic spaces are designed acoustically to receive the human voice. It’s like the resonant chamber in your body. You feel like you’re inside another body when you’re in an opera house. I like thinking about a character on stage performing inside another body.”

After the first performance, a critic for the Guardian puzzled over what to make of a show that featured a live bull and, in its human cast, a “pair of incontinent contortionists, one of whom arcs her body and pees all over the stage.” Another character came across as a “static, naked odalisque [who] spends almost the entire performance with her head hidden under a black rubber veil, and with a hand up her own bottom.”

The strictures of the stage did not exactly suit him, Barney says now. “I couldn’t work with the same level of physicality that I’m used to. I also couldn’t create a close-up.”

* * *

The idea to adapt Ancient Evenings came from Mailer himself, whom Barney had cast to play Harry Houdini in Cremaster 2, which also enlisted elements of Mailer’s nonfiction masterpiece The Executioner’s Song. That book, about the crime-scarred life and complicated execution of Gary Gilmore, was an established classic from its release in 1979. The novel Ancient Evenings, however, had not met with the reception Mailer thought it deserved.

“It is, speaking bluntly, a disaster,” wrote Benjamin DeMott in the New York Times. Though his review thrills over elements of a story that “pulls its reader inside a consciousness different from any hitherto met in fiction,” DeMott found the bulk of the book a dire mess, populated by characters who came across as “ludicrous blends of Mel Brooks and the Marquis de Sade.” Other less-than-charitable dismissals cast the book as “pitiably foolish,” “impossible to summarize,” and blighted by “pointless, painful, unintended hilarity.”

“It is, speaking bluntly, a disaster,” wrote Benjamin DeMott in the New York Times. Though his review thrills over elements of a story that “pulls its reader inside a consciousness different from any hitherto met in fiction,” DeMott found the bulk of the book a dire mess, populated by characters who came across as “ludicrous blends of Mel Brooks and the Marquis de Sade.” Other less-than-charitable dismissals cast the book as “pitiably foolish,” “impossible to summarize,” and blighted by “pointless, painful, unintended hilarity.”

Mailer himself was of a different mind. “He loved that book,” says John Buffalo Mailer, the writer’s son, who plays one of three incarnations of his father in River of Fundament. “He would no sooner pick a favorite book than he would a favorite child, but Ancient Evenings was a labor of love”—it took more than ten years to complete—“and it was heartbreaking the way it got, I don’t want to say ‘written off’ … The truth of the matter is the first hundred pages of that book are incredibly tough to get through. If you make it through those hundred pages, then it starts reading like The Naked and the Dead. It starts to flow and move. He always wanted to see something more happen with it, which is why he talked to Matthew.”

Barney dug into the book at Mailer’s insistence and found elements of its surreal, body-snatching story fit for extrapolation. He tangled with Mailer’s prose and read reactions to its bawdy, sprawling sensationalism. “I was influenced as much by a review of Ancient Evenings as by the book,” he says. That review was Harold Bloom’s in The New York Review of Books, which was vexed by parts of the novel but rather more pleased with its scope than many others at the time.

“Our most conspicuous literary energy has generated its weirdest text,” Bloom wrote, before making a case for its endearing, invigorating, spiritually searching weirdness. He continued: “I don’t intend to give an elaborate plot summary, since if you read Ancient Evenings for the story, you will hang yourself.” But: “Ancient Evenings rivals Gravity’s Rainbow as an exercise in what has to be called a monumental sado-anarchism.” And: “Ancient Evenings is on the road of excess, and what Karl Kraus said of the theories of Freud may hold for the speculations of Mailer also—it may be that only the craziest parts are true.”

Key to Bloom’s reading of the book, for Barney, was the notion that the most meaningful characters in Ancient Evenings were in fact stand-ins for Ernest Hemingway and Mailer himself. The review, Barney says, posited “that the book was effectively autobiographical, that Mailer saw himself as being too late—that the great American novel wasn’t needed anymore by the time he had come into his own. He wanted to be Hemingway but he couldn’t. That interested me. So I started putting Mailer himself into the role of the protagonist, in reincarnations of the same character.”

His revelation as to how to approach Ancient Evenings came after his conversations with Mailer, who died in 2007. “We talked about in what way it could function as a libretto,” Barney says. “But he passed away not long after that, so unfortunately he never saw it develop into the hybrid that it is now. There are definitely things about the film that I couldn’t or probably wouldn’t have done were he alive. I’m not so sure what he would have thought about it.”

But the prospect of a less-than-literal approach must have been on the author’s mind. “I think he certainly knew, from the way I used The Executioner’s Song in Cremaster 2, what adaptation means to me,” Barney says. “It’s loose. I always visualize these things as host bodies and my language [as] a guest passing through the host body, touching it but not really becoming it. I think Mailer understood that.”

John Buffalo Mailer, for his part, thinks his father would have been pleased. “There were not many people in the world that Norman acknowledged as a genius,” he says. “Matthew was one of them.”

* * *

The spirit on a Matthew Barney film set is never less than unconventional. For a stretch in the fall of 2012 the artist’s studio in Queens was outfitted with a precise replica of Norman Mailer’s former Brooklyn home. The author’s book collection sat on dusty shelves, with actors in zombie garb roaming among real-life literary mavens and Hollywood stars. Emblems of ego and achievement strained for space on the walls. There was a memento from a debate with William F. Buckley in 1962, and a framed Life magazine cover trumpeting Mailer’s  report on a fight between Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali (with a cover photograph by Frank Sinatra).

report on a fight between Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali (with a cover photograph by Frank Sinatra).

On a day of shooting, Barney, as director, painted gold accents on grisly undead characters’ faces and guided actors through dialogue drawn from Mailer as well as Hemingway, Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and William S. Burroughs. “Past and future come together on thunderheads, and our dead hearts live with lightning in the wounds of the gods,” bellowed one character, in a scene that required more than a few takes to get right.

With his bushy white beard, and wearing a black T-shirt ornamented by the death-metal band Cannibal Corpse, Barney looked like anything but a refined cineaste. But his charge was much the same. “Pour it a little more aggressively,” he said through a mouthpiece to a production designer wetting the set with a strange, unidentified liquid. To the actress Ellen Burstyn, in the midst of a stubborn scene, he suggested, “I think we should not smile.” He was right: the eerie Burstyn’s version of not-smiling makes for an effect not to be forgotten.

A month later, another day of shooting began at 6:30 A.M. and called for floating an outdoor replica of Mailer’s apartment around the New York waterways on a barge. As the cast ate catering in the dark outside the studio, preparations were made: structures hoisted, lifejackets secured, boats untied. Shortly after sunrise, the industrial-size barge drifted off, pushed by a tugboat and followed, at a distance, by a camera boat with Barney and a few others on deck.

The floating processional made its way down the East River to Newtown Creek, an industrial waterway separating Brooklyn and Queens. In the midst of the workday, noisy and clanging, industrial rigs filled barges with dirt. Towering silver “digester eggs” gleamed in the sun, doing the work of a nearby sewage treatment plant. All seemed still on the water as, on land, cranes separated piles of trash at a recycling receiving center. “That pile’s pretty bad-ass, with the seagulls on it,” Barney said to the camera operator. The gulls were eating glass.

On the barge, characters from the story, in dirty makeup and costumes like decomposing clothes from the grave, spent the day standing sentry on the apartment’s balcony for shots to be mixed with scenes set inside, at Norman Mailer’s wake. Actors playing guests at the wake make up an eclectic cast: Paul Giamatti, Maggie Gyllenhaal, Elaine Stritch, Salman Rushdie, Debbie Harry, Dick Cavett, Lawrence Weiner, and Larry Holmes, among others. But today the action was contained to just a few mourners and undead souls, to be filmed from out on the water.

With footage from the morning logged and the afternoon whiled away in wait, the schedule led to a sunset scene featuring the avant-garde vocalist Joan La Barbara singing Walt Whitman beneath the Brooklyn Bridge. The boats loosened up and ventured out again, past the United Nations Headquarters, the Chrysler Building, the Con Ed East River generating station. Closer to the bridge, floating out in the middle, the drummer Milford Graves stepped onto the barge’s balcony and began banging on the railing, shaking bells and making a racket. Then La Barbara stepped out and sang, her mouth moving and her microphone on but her sounds falling silent across the distance and the wind. Her song drew words from Leaves of Grass, recast by Barney’s own sense of writerly refraction. Of the style of the script, La Barbara later said, “It's almost like Virginia Woolf, the way she will turn a phrase and then bring a phrase back after having put it through some kind of prism.”

As the sun went down, the sky glinted pink off the water. The barge continued drifting beneath the bridge, crossed above by traffic with no notion of what was happening below. The tugboat started its laborious turn. It was time to go home. The sky, as it blackened, looked somehow both sensuous and macabre. “It’s a beautiful sky, isn’t it?” Barney said.

Back at the studio, the barge and the boats nested into their docking stations. Bringing such vessels in is no easy feat. The barge was more than fifty yards long, with nearly forty feet of height between the water and the top of Mailer’s floating home. The tugboat was large enough to marshal the barge. The camera boat was smaller and easier to steer but less resilient against its surroundings. “Steel on fiberglass?,” the driver asked as he idled his way in. “Steel wins.”

* * *

Spells of shooting happened elsewhere in New York and other locales as well. A crucial scene was filmed last summer with a mass of more than three hundred extras in a disused dry dock at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Before that came a trip to sites where salmon spawn in Idaho, near where Hemingway died and Barney was raised. Toward the beginning of the project, the traveling road show ventured out for extended stays to film and perform in Los Angeles and Detroit.

Both cities figure prominently, as part of a triumvirate with New York, in a film that is intensely peculiar yet permeated by a sense of place. A typical scene from LA features a ragtag marching band playing discordant music at a gnomic ceremony outside a car dealership (for Chrysler, which seems significant and proves to be, but in ways that are more cryptic than clear). A curious speech transpires on the subject of putrefaction, feces, fermentation, and rot. A gold 1979 Trans Am, which turns out to be one of the movie’s lead characters, drives off a lot to a parking garage where a naked woman with bugs in her hair writhes around as a group of musicians makes sounds with horns and guitarróns.

In Detroit, slow panning shots of an urban hellscape give way to more action involving the car, which races around mysteriously and drives off a bridge from which Houdini once jumped. A monumental set piece takes place at an abandoned steel plant where Barney and his crew spent months designing and building a custom set of furnaces to melt rock into metal. Onscreen, five towers rise, fire shooting from their tops, as hard forms are made molten by temperatures topping two thousand degrees. “It was very dangerous,” Barney said. Actors wore safety suits; an audience watched. The result of the orange streams of iron, bronze, lead, and copper was an indelible film scene and a series of sculptures made from twenty-five tons of material poured.

Many of the memorable scenes in New York telescope out from Mailer’s wake, with the writer himself featured in three reincarnated forms. John Buffalo Mailer, who plays the youngest form of his father, features in one scene for which he climbed inside the cut-open cadaver of a cow. “They had cleaned it out as best one can, but it’s the inside of an animal,” he remembers. “I will say that once I got inside I felt oddly peaceful and sheltered and taken care of.” The jazz percussionist Milford Graves, in his role as the second incarnation of Mailer’s soul, later plays the cow as drums, from the inside.

Musicality, in fact, plays a significant role in River of Fundament’s sense of anarchic freedom and its sense of shape. Remnants of the project’s beginnings as an opera remain on screen, in dialogue delivered with an unorthodox sing-song cadence and set pieces given over to surreal musical interludes.

“In film, it’s very hard for people not to think of music as something there to inform one’s sense of what the emotion is,” says Jonathan Bepler, a composer who collaborated with Barney on all stages of River of Fundament. (He wrote music for the Cremaster Cycle too.) “For me, it’s much more than that.” Blurring the distinction between opera and film proved catalytic, he says. “In opera, musicians are allowed to be anywhere at any time. Having that permission helped.”

For Barney, as a director whose concerns are more sculptural and imagistic than conventionally cinematic, music is a liberating agent. “I’m really interested in the abstractness or openness that music can provide,” he says. “It can also do the opposite—it can be so emotionally fixed that it works against what I’m interested in. But the way that Jonathan composes music is quite similar to the approach I take in terms of less-determined ways of thinking about linearity and storytelling.”

* * *

Photo: Samantha Marble

In his studio, commanding actions to continue after River of Fundament’s premiere, Barney is quiet and intensely present. His speech is considered and slow, with long pauses when searching for the right word, if in fact a word will convey something that silence cannot. He is affable but also able to deflect vacant questions back with eyes that have grown dark and hard through looking.

“He is incredibly focused and centered as an individual,” says Barbara Gladstone, the gallerist who gave Barney his first New York show in 1991 and has since represented him on his rise to prominence in the art world. “As Matthew thinks about something and works at it in his head, it becomes evermore complex.”

With the film just recently finished—final edit set, sound mix complete—Barney sits in a makeshift office above the construction floor below. His beard is gone, and he wears a winter hat adorned with the logo of Budco Enterprises (the favored source of steel fabrication for Richard Serra). Pages for an elaborate River of Fundament catalog to be published this summer by Rizzoli hang tacked up on the wall, along with images of art works to travel to an exhibition, opening in Munich in March, of sculpture borne from the project.

The exhibition is as much a part of River of Fundament as the film itself. In terms of scale and sheer materiality, many of the pieces are more formidable than work from earlier in Barney’s career. In place of his signature use of plastics, jellies, and all manner of oozing agents is a new focus on earthy materials like iron, bronze, sulfur, and salt.

“There are descriptions in Ancient Evenings where you have elemental waste coming from the earth, like sulfur, molten iron,” Barney says. “Elements are interchangeable with the waste products of the body. Sulfur and excrement are used in a very similar way in the writing, as a sort of fundamental state.”

They figure into infrastructure too. In New York, “it’s all there along the waterways but barely visible,” Barney says. “You see it in a flash on your way to the airport—you look down and see the recycling plant, wastewater management, the natural gas and sanitation department. But the view from the waterways … I was interested from the start in framing the city through these waterways,” he says. “Working here on the East River and seeing it every day, watching the current change the way that it does, moving both directions, has a lot of power. The rivers are big working rivers. Once I started exploring the water, it changed my perspective on the city as a natural landscape.”

The notion of cities as natural machines for living, in all their grotesquery and pageantry and gasping for air, figures as one of River of Fundament’s prevailing themes. The camera fixes on sights of industrial might and decay the same way it ogles objects with a wizened sculptor’s eye. From those objects come stories, and the current washes back.

“The story comes first, then out of the story come reductions that are distilled,” Barney says. “I have to start with a story, as a sculptor. I haven’t really figured out any way around that.”

Andy Battaglia is an arts writer in New York. His work has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, The National, Frieze, The Wire, The New Yorker, and more. Find him here.

WWDD?

Dorothea Brooke and Will Ladislaw. Illustration: the Jenson Society, New York, 1910.

This afternoon at one, join our contributing editor (and, of course, daily Daily correspondent) Sadie Stein for a live Web chat with Rebecca Mead, hosted by Jezebel. The topic: What Would Dorothea Do? In honor of Mead’s engaging new book, My Life in Middlemarch, they’ll be discussing, as Sadie says, “George Eliot, Dorothea Brooke, what the novel can teach us today, plus life, love, and, yes, sex in Middlemarch.”

It promises to be a lively and enlightening discussion about a lively and enlightening novel. For my money, whenever I make eyes at someone, which, as you can imagine, is almost constantly, I still think of a line from Middlemarch: “They were looking at each other like two fond children talking confidentially of birds.”

And whenever I confront the dubiety of my future: “Even Caesar’s fortune at one time was, but a grand presentiment. We know what a masquerade all development is, and what effective shapes may be disguised in helpless embryos.—In fact, the world is full of hopeful analogies and handsome dubious eggs called possibilities.”

And whenever I encounter a physically unattractive person: “It is so painful in you, Celia, that you will look at human beings as if they were merely animals with a toilette, and never see the great soul in a man’s face.”

And whenever I’m too hungover to pull up the window shade: “We must keep the germinating grain away from the light.” (I think of myself, you see, as germinating grain.)

If you haven’t read Middlemarch, you still have a few hours to catch up before the chat. In all honesty, though, you should read Middlemarch. Believe the hype. It is the best.

The First-Ever Fuck, and Other News

Image via io9

Behold: the first written use of fuck, from 1528, inscribed by a monk who seems to have been pretty pissed off with an abbot.

“Kicking against the pricks becomes rather less impressive when the pricks have melted away.” Taking a hatchet to the Hatchet Job of the Year.

Wes Anderson’s new film, Grand Budapest Hotel, is by his own admission “more or a less a plagiarism” of the works of Stefan Zweig. Will the movie renew American interest in Zweig’s writing?

An “edit-a-thon” aims to close the gender gap on Wikipedia, to which far more men contribute than women. Though as the Newsweek reporter Katie Baker tweeted, “Maybe few women edit Wikipedia because they do enough thankless unpaid labor already.”

“Emptying the Skies,” Jonathan Franzen’s 2010 essay on the poaching of migratory songbirds, is soon to be a documentary.

Toby Barlow’s Write-a-House, a residency program that gives houses to writers, is still a bit shy of its fundraising goal, but there’s a week left in the campaign—help out.

February 11, 2014

Tonight: Rachel Kushner and James Wood

Photo: Lucy Raven

Tonight at seven, Rachel Kushner launches the paperback edition of her wonderful novel The Flamethrowers—she’ll be in conversation with The New Yorker’s James Wood at the Powerhouse Arena, in Dumbo. (Note to the uninitiated: it’s a bookstore, not an arena, though it would be something to live in a world where a Kushner/Wood bill could sell out Madison Square Garden.)

As we mentioned briefly yesterday, The Flamethrowers is one of eight books to have been shortlisted for the inaugural Folio Prize, the first major English-language book prize open to writers from around the world. Its aim? “To celebrate the best fiction of our time, regardless of form or genre, and to bring it to the attention of as many readers as possible.” Kushner is in good company: the other nominees are Anne Carson, Amity Gaige, Jane Gardam, Kent Haruf, Eimear McBride, Sergio de la Pava, and George Saunders. The winner will be announced on March 10; we wish her the best of luck.

But perhaps these recent developments aren’t enough to slake your Kushnerphilia. Should this be the case, we recommend her short story “Blanks,” excerpted from The Flamethrowers in our Winter 2012 issue. Or, from that same issue, the collection of art and photography she curated—images that inspired the novel. Or her interview with Jesse Barron, published on the Daily last year.

You can also read James Wood’s acute review of The Flamethrowers, published last year in The New Yorker—a fitting appetizer for his conversation with Kushner tonight.

Strawberry Fields

Photo: Ash Berlin, via Flickr

It has been some years now since I mastered the art of dressing strawberries in tuxedos.

I was first introduced to the skill at a friend’s baby shower in Rhode Island; a young woman demonstrated how one dipped the strawberry in white chocolate, and then, after letting it dry, dipped it again, at an angle, in milk chocolate. One appended a small chocolate bow tie and perhaps, with a toothpick, shirt studs. (And, if feeling really ambitious, made a distaff counterpart, all in white chocolate.)

My first strawberry-in-a-tuxedo looked like he had just come off a week-long bender. His lapels were smudged, his bow tie askew. But by the time I had dipped my fifth—I think we were supposed to stop at two, but I couldn’t—that out-of-season berry was a veritable Brummel. (Just in case one of them needed to attend a summer dinner-dance or something, I made one in a white dinner jacket, too.) The trick is letting it dry properly between dips, and holding it aloft while it does so.

In the years since, I have had occasion to perfect the skill, and have found it to be a very useful babysitting activity, too. I will not lie: on these occasions I have sometimes impugned the purity of the enterprise by introducing those little tubes of gel icing, and sometimes even a candy button, for extra detail work.

Many a locavore has bemoaned the denatured state of the supermarket strawberry: huge, tasteless, pale, and available year-round. It is true that a California-grown Elsanta, baptized with toxic fumigants and bred for long travel, bears little resemblance to the heirloom varieties you see, increasingly, at farmer’s markets. At a greenmarket not far from me, a terrific farm called Berried Treasures sells a hybrid wild-cultivated strain that is really delicious. But you cannot dress such a thing in formalwear. No, for that you want the hardiest, largest, beefiest specimen you can find, able to withstand repeated dipping in warm, tempered chocolate, and large enough to do justice to its finery.

As we know, chocolate-dipped strawberries have long held a cherished place in the echelons of Romantic Signifiers. Apocryphal sources from around the Internet claim that a woman named Lorraine Lorusso invented them in the sixties, when she was a candy buyer for Stop & Shop in Chicago—she used to demonstrate new products at the front of the store, and as looked at the strawberries one day, it occurred to her that they ought to be dipped, immediately, in chocolate. But who was the genius who decided to dress the strawberry in formal wear? Google yields no results, although one suspects the eighties. Like the large martini glass filled with mashed potatoes, or the bed strewn with rose petals, its origins are lost in the mists of time. Like love itself, it simply Is. In the immortal words of James Baldwin, “Love is a battle, love is a war; love is a growing up.” Love is a strawberry dressed in a chocolate tuxedo.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers