The Paris Review's Blog, page 737

February 16, 2014

Open Ye Gates! Swing Wide Ye Portals! Part II

This is the second in a two-part series on St. Louis and the 1904 World’s Fair. Read part one here.

Photo: Edward McPherson

The Palace of Agriculture is a blinding colossus in the sun. The man next to me reads from a booklet: twenty acres large, covered with 147,250 panes of glass. I have timed my visit—in one minute a giant clock made of 13,000 flowers will strike the noon hour. I am finished with the exhibits. I have seen the Missouri corn palace, the 4,700-pound cheese; I have laughed at Minnesota’s contribution, “The Discovery of St. Anthony Falls by Father Hennepin” shaped out of one thousand pounds of butter. Now a hiss of compressed air throws the 2,500-pound minute hand the final five feet, where it points to the giant numeral 12. An hourglass flips, doors open to reveal the gears of the clock—the triumph of industrial time—and a massive bell tolls the death of more agrarian rhythms.

Pyramids of fruit on a sea of china plates—the entire Palace of Horticulture smells like apples. Virginia has created a statewide shortage by sending too many to the Fair. I dip my fingers into the fountain, which gushes ice water. Farmers shake their heads at the monstrosities on display: a pineapple the size of a turkey and a mysterious dimpled fruit, said to be the unholy cross between a strawberry and a raspberry.

* * *

The company is a major employer in this city. One cannot miss its print and radio campaign: “We grow ideas here.” “We work together here.” “We dream here.” “We’re proud to be St. Louis Grown.” Its website offers videos of employees working in food banks, cleaning up after tornados, visiting Forest Park, and standing in front of the Arch. Articles rate the town’s best burger joints, as judged by company workers. The company is a major donor to local charities and institutions, including the university in which I teach. In 2013, the company’s net sales were $14.8 billion, up ten percent. Its chief technology officer won the 2013 World Food Prize. The company has 21,183 employees in 404 facilities in sixty-six countries—but its headquarters are here, where, over the years, the much-maligned Monsanto Company has worked to produce saccharin, PCBs, polystyrene, DDT, Agent Orange, nuclear weapons, dioxin, RoundUp, bovine growth hormone, and genetically modified seeds.

* * *

I live in a small apartment building that stands in the footprint of the Horticulture palace. We grow nothing in the backyard but herbs, potted lettuce, and a few stunted rose bushes, but on sunny days I like to think I smell apples.

* * *

A private gate in an old St. Louis postcard.

In Meet Me in St. Louis, Judy Garland’s older sister reminds her, “Nice girls don’t let men kiss them until after they’re engaged. Men don’t want the bloom rubbed off”—to which Garland responds, “Personally, I think I have too much bloom.”

The film’s crisis comes when Garland’s father declares his intention to move the family to New York City, dashing his daughters’ romantic interests and hopes of the Fair. In the dramatic Christmas Eve denouement, he decides the family will stay put, saying, “New York doesn’t have a copyright on opportunity. Why, St. Louis is headed for a boom that’ll make your head swim.”

* * *

A slick-haired fellow shouts from an automobile: “One hundred and forty models of cars powered by gas, electricity, and steam!” His eyes shine with belief in the Palace of Transportation. He waves a magazine furiously about; as he reads, he stabs his finger in the air: “This new form of carriage will become perfected, and then the great cities will spread out into the suburbs, and life on an acre will become a possibility for even the humblest class of people!”

* * *

Opened in 1954, Pruitt-Igoe was a mammoth, state-of-the-art public housing development designed by Minoru Yamasaki, who later would build the World Trade Center. The Pruitt-Igoe development rose on a parallelogram bounded by Cass Avenue, North Jefferson Avenue, Carr Street, and North 20th Street on St. Louis’ northside, close to downtown. A city-designated “slum” was razed and in its place rose a modern utopia, Le Corbusier’s “Radiant City” made real: thirty-three modular eleven-story buildings smartly arrayed in superblocks across fifty-seven acres, each high-rise facing the same direction, vertical neighborhoods of light and space with ample parking and vibrant public areas. Kids scampered in the breezeways. Apartments were clean and bright, offering views better than those enjoyed by the rich. In a recent documentary, The Pruitt-Igoe Myth, a former resident remembers her top-floor apartment as a “poor man’s penthouse.” Another says, “It was like another world,” and then adds, “Everybody had a bed.”

Pruitt-Igoe was founded on the faith of communal, public life; it offered better living through architecture. One set of high-rises was to be white (the Igoe Apartments, named after a Congressman), the other black (the Pruitt Homes, after a Tuskegee airman), but Brown v. the Board of Education came down the year the development opened—and the whites moved out. Black by default, Pruitt-Igoe flourished. In 1957, occupancy was at 91 percent. Fifteen thousand tenants would call it home.

But the project was built for a postwar boom that never came. Another kind of planned community was thriving beyond city borders—the suburb, fueled by the same 1949 Federal Housing Act that enabled Pruitt-Igoe. Having already legally fixed its boundaries, the city couldn’t abate its population decline by annexation. With the middle class fleeing to the suburbs, the development would never be able to raise the significant maintenance fees it needed from its tenants. The city let the brand-new buildings deteriorate almost from the start. There were also more pernicious factors at work. Suburbs passed zoning laws barring low-income housing; public projects became a tool of segregation, the goal being to prevent, in the parlance of the day, “negro deconcentration.”

One historian has called St. Louis “the poster child of white flight.” It’s often ranked as one of the country’s most segregated cities based on what’s called its “dissimilarity score,” which analyzes racial makeup across census tracts. While different measurements suggest the divide might not be so stark, the traditional color line is widely acknowledged to be Delmar Boulevard. Seventy-three percent of residents south of the boulevard are white; head north, and neighborhoods become ninety-eight percent black.

* * *

In the musical, Garland sings about her home at 5135 Kensington Avenue, a stately three-story Victorian on an idyllic block on the MGM back lot known as “St. Louis Street,” which would appear in a number of films before

The Victorian on Kensington Ave.

being torn down. The real address, a few blocks north of Delmar, belonged to the writer Sally Benson, from whose memoirs the film was drawn. Benson’s former home was abandoned and demolished in 1994. Today, 5135 Kensington Avenue is a vacant plot with a history of debris and graffiti complaints whose value was last appraised by the city to be $3,800. It is owned by the St. Louis Land Reutilization Authority. In 2001, a ten-year-old boy was eaten by wild dogs in a park two blocks away.

* * *

I push past the crowds into the Palace of Education and Social Economy. In a model classroom, the teacher struggles to keep the attention of the giggling local children, who are thrilled at their turn to take part in the exhibit. I wander into the “School for Defectives.” Deaf students sewing—blind students on violins. Helen Keller, a senior at Radcliffe, will be lecturing soon. On my way out, I peruse modern treatments for the insane.

* * *

St. Louis is preoccupied with school districts, perhaps because its public schools were stripped of accreditation by the State Board of Education in 2007. The district was nearly twenty-five million dollars in debt; fewer than one in five students could read at grade level. In fall of 2012, the schools regained provisional accreditation, though the previous spring’s exams had shown only twenty-seven percent of students passing in math.

The problem of St. Louis schools is a Gordian knot of politics and passion. But most people admit the usual “solutions”—bussing; lotteries; a district transfer system; a mix of private, parochial, charter, and magnet schools—have failed to create equal opportunity.

The odds are against the shrinking city. A voluntary transfer system, scheduled to extend until 2019, allows African American students from the city to attend schools in one of the wealthier county districts. Waiting lists are long; each year, thousands of students are turned away. Those who are admitted face an average one-way bus ride of fifty-four minutes, among other challenges. At the start of 2013, 5,036 students transferred from city to county schools. The program also allows white suburban students to transfer to city magnet schools—eighty-seven students took advantage of that opportunity.

* * *

East St. Louis, Illinois, sits just across the Mississippi River from downtown St. Louis. The U.S. attorney for the district recently called it “the Wild West.” From 2008 to 2011, the city had to cut its police force by thirty-three percent; the per-capita murder rate is more than sixteen times the national average. Since 1960, East St. Louis has lost two-thirds of its population. A casino and the school district provide most of the jobs.

But St. Louis holds its own. In 2013, it ranked as the third most violent city in the U.S., after New Orleans and Detroit. Another report listed two of its neighborhoods on the “Top 25 Most Dangerous Neighborhoods in America.” Such rankings are invariably rebutted by the mayor’s office and police department—often with good reason, as many of these stats are skewed by an antiquated city/county divide that puts St. Louis at a tremendous national disadvantage in the polling methodology. Still, at the time of the Fair, St. Louis was nearly twice the size it is now. It has lost some 500,000 people over the past fifty years. Segregation, disastrous “urban renewal” projects, white flight, “redlining” (racist lending practices), and blockbusting (racist real-estate scaremongering and profiteering) tell some of the complicated story. The fact remains: the last time the city had this few people was in 1870—and the national perception endures that it is dangerous to live in St. Louis on either side of the river.

* * *

A man in a blue uniform approaches me. He is a physical specimen—of “good feature and bearing”—one of the Jefferson Guard, the omnipresent guides and policemen of the Fair, some three hundred strong. I nod and say, “Just passing through.” He looks at me and smiles, but I feel nervous. I cross the street. He pulls his mustache as he reprimands a boy for spitting: “No one is innocent.” He should know. For fifty dollars a month plus housing, he and his brethren will arrest 1,439 citizens, including 312 trespassers, 421 disturbers of the peace, five murderers, and one vile soul charged with “wife abandonment.” On hot summer days, he sports a lighter khaki.

* * *

Pruitt-Igoe residents were treated with suspicion and subject to dehumanizing regulations, the subtext being that the poor were in need of forced moral uplift. Televisions were forbidden; apartments could be painted no color but white. Disastrous welfare laws broke up families—no able-bodied man could live in a unit that received federal aid, so fathers hid in closets when they were supposed to be, by regulation, out of the state. Many of the buildings’ modern innovations functioned poorly. “Skip-stop” elevators that didn’t land on every floor—an economic concession that supposedly encouraged mingling and use of the stairs—made residents easy bait for muggers. Public galleries became gauntlets. Residents had been promised beautiful, safe, affordable housing, but city maintenance deteriorated. Elevators smelled of urine and broke down regularly; “vandal proof” light fixtures stayed dark. Firefighters, police officers, and ambulances stopped showing up after frustrated tenants dropped bottles and bricks. Pruitt-Igoe quickly became an emblem of an overblown white fear of black poverty and crime. As the experiment unraveled, a complex story of structured inequality and misunderstood urban forces was turned—by some—into a more vicious parable of how those people just couldn’t be helped, just couldn’t be trusted with nice things.

* * *

I hurry past an anthracite coalmine belching soot and smoke in a gulch south of the palace. Slipping between a pair of Egyptian obelisks, I enter the Palace of Mines and Metallurgy: an oil rig, a 1,200-pound pot of mercury, the devil made of sulfur. I duck into a dark room that holds a luminous collection of radium ores. They look like fireflies. Next door, at 2:30, the U.S. Government will stage a demonstration of the mysterious element. Cosmopolitan implores I not miss this epochal discovery: “Revealing an energy so powerful, inexhaustible, and apparently so abundant in nature, that its substitution for other forms of light and power now in general use is within the range of possibility.”

* * *

A local sociologist named Lisa Martino-Taylor recently uncovered a secret Army experiment conducted in the 1950s and 1960s in which St. Louis citizens were unknowingly sprayed with a mixture of zinc cadmium sulfide that she believes might have been radioactive. Chemical sprayers were attached to buildings, schools, and station wagons. Residents were told smoke screens were being tested that might conceal the city from the Russians. The Army admits the aerosol was fluorescent, but it won’t say whether it was radioactive. Many documents remain classified. Most of the spraying was done around the Pruitt-Igoe complex, home at the time to about ten thousand low-income residents, some seventy percent of whom were children.

* * *

In 1969, Pruitt-Igoe tenants organized a rent strike, a shocking development in public housing. After nine months, the housing authority caved. But that winter, two months after the victory, water and sewage pipes burst, perhaps partly due to an estimated ten thousand broken windows. Sheets of ice cascaded down the façades. Buildings were vacated, then stripped by thieves. Superblocks became ghost towns, the darkened shells offering a high-rise vantage for drug lords looking to evade enemies and cops.

The implosion of Pruitt-Igoe.

In 1972, the city capitulated—the first three buildings were imploded. The demolition of building C-15 on April 21, 1972, was nationally televised, the spectacular footage spreading so widely that Charles Jencks, the architectural theorist, proclaimed this first stage of demolitions to be the day “modern architecture died.” The final 800 tenants were relocated, and by 1976 the development had been erased, leaving a fifty-seven-acre scar across the northside.

* * *

In the Hall of Anthropology, housed in a university building I can see from my office window, visitors could get tested anthropometrically—their bodies weighed, their skulls, foreheads, ears, and jaws measured—or gawk at a Brazilian shrunken head. On display in the ethnological exhibits: a family of nine Ainus from Japan (supposedly the world’s hairiest people), several Patagonian “giants,” pygmies from Africa, representatives from more than twenty Native North American tribes, and “many other strange people, all housed in their peculiar dwellings, such as the wigwam, tepee, earth-lodge, toldo, or tent.” The Department of Anthropology hoped to show “how the other half lives, and thereby to promote not only knowledge but also peace and good will among the nations.” Cultural and political imperialism were given a scientific gloss; the virtues of white, western assimilation were roundly praised. In his diary, one fairgoer favored the Ainus, whom he found “not as dirty nor nearly as lazy-looking as the Patagonians.”

* * *

St. Louis brick is a fine, beautiful brick that was once the pride of the city. In the fourth ward, there is a long-running scam in which thieves set fire to a vacant house; after firefighters come and scour off the mortar with their hoses, the thieves return and cart off the cleaned bricks. Thanks to a policy of demolition and clearance, an inner-city prairie has sprouted, a startling sight. Satellite imagery shows swaths of city blocks turned into gridded green plots of land. A four-way intersection in the middle of the city might look like a forgotten rural byway.

* * *

The gem of the anthropological offerings was the Philippine exhibit, dedicated to the islands that had become a U.S. protectorate following the recent Spanish American War.

The most popular—and controversial—part of the exhibit was the Igorot Village. In their loincloths, the tribesmen looked “like bronze statues,” according to one female viewer. (A male visitor noted they “seemed to have a tremendous attraction for the ladies.”) Secretary of War William Howard Taft wanted the tribesmen in trousers, but the fair’s Board of Lady Managers overruled, upholding their idea of science over prudishness. The loincloths carried the day, even late into the year, when the huts were warmed to accommodate the light dress.

Even more sensational were the regular dog feasts, an occasional tribal tradition greatly played up for the Fair. Fueled by reports in the papers, visitors brought dogs to the village to donate, sell, or trade; some sources claim twenty canines a week were provided by a local pound, though the number seems apocryphal.

At the Philippine Model School, Igorot schoolchildren serenaded President and Mrs. Roosevelt with “My Country ’Tis of Thee.” One Igorot chief insisted a telephone be installed in his imperial hut. A photo caption from Cosmopolitan that September: “Miss Roosevelt and her friends are amused at the manners and customs of the Filipinos.” Four white-hatted white ladies holding small bouquets of flowers peer around some shrubbery and laugh, flashing their white teeth.

* * *

An inner-city prairie.

A local sixteen year old named T. S. Eliot went to the Fair. I visit the reading room of the Missouri History Museum’s Library and Research Center, just south of the Life-Saving Lake (now gone), where shipwrecked sailors were rescued daily at two p.m. I pick up Stockholder’s Coupon Ticket #1313, signed “Thos. S. Eliot” and bearing a photo of the boy poet, who gazes slyly down to the left, as if he knows better than to look. He wears a coat and tie, with tidy hair and a tight collar. His alabaster skin is wan and washed-out, and his heavy-lidded eyes are sunken, blurred, and unfocused, almost blind. One large ear is turned, as if listening. He sports a thin coy smile. The archivist handed me the photo with a shudder. “Creepy,” she said.

Eliot never wrote directly of visiting the Fair—though a year later, in his school’s journal, he would publish a south-seas short story critical of the powers of civilization, certain details of which recall the Igorots. Lecturing at Harvard twenty-seven years later, he would state, “Poetry begins, I dare say, with a savage beating a drum in a jungle.”

I distrust my eyes. Chief Geronimo sits in a booth at the Indian Building. A sign says the seventy-five-year-old Apache prisoner-of-war arrived from Fort Sill, Oklahoma, under military guard. A man whispers, “Yesterday, he made a bow and arrow for my neighbor.”

* * *

August 12 and 13 were Anthropology Days, a series of sporting contests organized by the departments of Anthropology and Physical Culture a few weeks before the Olympic Games (when pervading beliefs held that the Americans would win over the “primitive” races, never mind the fact that George Poage, an African American sponsored by the Milwaukee Athletic Club, would become the first black medalist when he won bronze in both the 220- and 440-yard hurdles).

And so the Sioux competed against the Arapahos in tug-of-war. Tribesmen tossed a fifty-six-pound weight. There was a mud fight. Crack spear-throwers struggled with the javelin. Runners stopped and ducked under the finish-line tape. Participants laughed at the events; they didn’t try very hard. The white man’s games didn’t translate. Attendance was poor, as was the quality of “data” collected by the departments. Winners were given American flags. A Filipino Negrito named Basilio was the fastest to climb the greased pole.

* * *

On July 2, 1917, near Fourth and Broadway in East St. Louis, a black man was cornered and strung up on a telephone pole; when the rope broke, the man fell to the gutter, where, according to the New York Times, a mob “riddled his body with bullets” before hanging him again. In 1916 and 1917, some ten-thousand African Americans moved to East St. Louis from the rural south as part of the Great Migration, greatly feeding white cultural, economic, and political fear. Labor tensions ran high. The night before that July lynching—which would prove to be only one of many—a car of white men had driven through Market Street, shooting at black residents. When plainclothes police officers appeared in a car, they were mistaken for the original culprits and fired upon, killing two. East St. Louis exploded into some of the bloodiest race riots in American history. The goal: drive out the blacks.

Houses were set alight and the fleeing residents gunned down. Eyewitnesses described babies being tossed into the river or shot in the head and fed into the flames. Small boys fired revolvers. Two young white girls dragged a black woman off a streetcar; another white girl stomped on a black man’s face, bloodying her stockings. Bodies were left in the street. Militiamen were ordered to shoot to kill in their efforts to subdue the white mobs, but one black woman—hearing gunfire—fled an outhouse only to have her arm shot off by a soldier. The city’s most-famous expat, Josephine Baker, would remember watching—as an eleven year old—a man being beaten and hearing about a pregnant neighbor whose baby was torn out.

The mayor’s office attempted a cover-up; his private secretary ordered police and militiamen to smash cameras and arrest anyone attempting to photograph the violence. But the next day, a telegram reached the War Department: “Very bad night fires and rumors period. A lot of negroes killed number unknown period.” The approximate death toll: eight whites and anywhere from forty to hundreds of blacks. At least $400,000 in property lost. More than six thousand African Americans would flee. W.E.B. Du Bois, sent to bear witness to the massacre, reported an old woman’s lament: “We can’t live in the South and they don’t want us in the North. Where are we to go?”

* * *

In the fall of 2013, an editorial appeared in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch proposing an amendment to the state constitution that would join the city and county of St. Louis—undoing the “Great Divorce of 1876,” what the editorial board called “the biggest mistake this region ever made.” Secret talks—including “key city, county, civic, and corporate leaders”—had been underway for years. The paper pushed the mayor to go public. An anonymous opposition group set up a website. Weeks went by with no more news.

* * *

During the Civil War, St. Louis had slaves but was not southern. It is not western, like Kansas City, on the other side of the state, but it is not eastern, not really—just ask any transplant from the coast. It truly is Middle American, whatever that means. There’s the old joke: what kind of city would advertise itself as a jumping off point, an exit door, a gateway to somewhere else?

The fear: that it has become just another link on the Rust Belt, the next Detroit. It once competed to be the biggest and best in the middle of the country—a crown long since lost to Chicago, though the rivalry (which sometimes seems a little one-sided) endures. Valentine’s Day weekend 2014 marks the 250th anniversary of the founding of St. Louis, which will be celebrated with a lavish festival in Forest Park. The centerpiece: a sculpture of a heart—on fire—floating in the Grand Basin.

An international contest was held to reimagine use for the Pruitt-Igoe site, with winners announced in 2012, the fortieth anniversary of the demolition. The top design, from two Harvard graduate students, took home $1,000 and called for the abandoned land to become an “ecological assembly line,” with nurseries and aquaculture basins producing native plants, trees, mussels, and fish. The proposal is beautiful, part memorial, part farm, but I cannot stop staring at images of the implosion. Behind the buildings and the dust cloud, to the left of the horizon, stands what was then the city’s most recent monument to a radiant future—dedicated only four years earlier—the gleaming Gateway Arch.

* * *

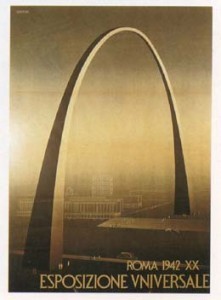

Mussolini's arch.

The Arch, designed in 1947 by Finnish futurist Eero Saarinen, was a monument to America’s westward expansion, a six-hundred-and-thirty-foot tall and wide stainless steel curve made of tapering equilateral triangles, a mathematical dream rising over the heartland. From the beginning, its purity was suspect. After Saarinen announced his design, an Italian architect claimed the idea was his, stolen from a fascist monument he had drawn up for Rome’s 1942 World’s Fair (never realized). Twenty-one years later, at the dedication, Vice-President Hubert Humphrey proclaimed the Gateway Arch would provide a “new sense of urgency to wipe out every slum,” promising that—by its example—“whatever is shoddy, whatever is ugly, whatever is waste, whatever is false, will be measured and condemned.”

Forty downtown blocks were leveled to make room for the arch, many of them home to poor bohemians, artists, and African Americans. A day or two after reading Humphrey’s speech, I hear a historian say on the radio that the arch hasn’t transformed the city as its builders had hoped, and if it is destined to be remembered by history, it will not be as a celebration of the Louisiana Purchase, but as a monument to the mid-20th century—to an America so powerful, so brash, so sure of its future that it would destroy a downtown to put up a symbol.

* * *

A perfect day at the Fair could be ruined in many ways, by rain, cold, heat, exhaustion, not to mention the usual human foibles and follies. The expense was not trivial; expectations had to be met—a lot was riding on the day. Countless diaries, photos, letters, articles, and books exist—an obsessive amount of documentation.

And so beneath the fairgoer’s wonder was a kind of manic sorrow, a present-tense nostalgia. Dazzled by the lights, you already began picturing life outside the glare. As one concert attendee rued in his diary, “Our taste will be better than our opportunities hereafter.”

* * *

Meet Me in St. Louis ends at the Fair. Overlooking the Grand Basin, Garland swoons to her beau, “I never dreamed anything could be so beautiful.” When the palace lights come on, her mother sighs, “There's never been anything like it in the whole world.” The youngest sister asks, “Grandpa? They'll never tear it down, will they?” He replies, “Well, they’d better not.” Garland gets the last breathless word: “I can’t believe it. Right here where we live. Right here in St. Louis.” Fade out.

* * *

Closing Day was December 1, 1904. The governor declared it a school and business holiday. As midnight approached, President Francis made a brief speech, then turned off the lights as the band played “Auld Lang Syne.” His face floated over the grounds, painted in fireworks next to the words “farewell” and “good night.”

Having cost roughly fifty million to build, the disposable Fair buildings were sold for $450,000 to the Chicago House Wrecking Company, which salvaged and resold one-hundred million linear feet of lumber (“enough to build outright over ten cities with a population each of 5,000 inhabitants”), plus roofing, steel, doors, plumbing, fittings, and so on. Also for sale, some 350,000 incandescent lamps: six cents used, sixteen cents new.

* * *

In an Alpine-themed restaurant on the Pike, the Fair fathers pick their teeth with quail bones; juice from medallions of beef drips down their chins. In the corner, the governors of Wisconsin, Missouri, and Minnesota share a hearty joke. In five days, President Francis will turn off the lights. The men are confident and rich. One of the waiters bumps me. He says to a guest, “Pardon him, sir—just another rube at the Fair.” The gentlemen smirk in my direction before offering me a seat. One asks, “Well, was it worth it?” Does he mean the Fair or my visit? Then President Roosevelt stands and delivers these thoughts: “I have but one regret, and that is a deep regret—the regret that these buildings and these exhibits could not be made permanent; that these buildings cannot be maintained as they are for our children and our children’s children and all who are to come after, as a permanent memorial of the greatness of this country. I think that an American who begrudges a dollar that has been spent here is not so far-sighted as he should be. It is a credit to the United States to have had such an exposition carried on so successfully from the beginning to its conclusion.”

* * *

I have ridden a tiny tram capsule up the north leg of the Arch. The 1960s space-age pod barely fits five people and rises in a rocking-step motion—ka-chunk, ka-chunk—followed by stretches of smooth ascent. My head brushes the roof of the pod. Before boarding, a futuristic female voice speaks from a monitor: “The Gateway Arch transcends time.” The trip lasts four minutes.

A Park Ranger repeats over and over: “Welcome to the top. It’s all good,” and, “You got questions? Let your tax dollars sing.” Visitors get their bearings by peering through seven-inch slits. A hot summer day: the arch casts a long, lopsided shadow. The base of the arch holds something called the Museum of Westward Expansion.

The arch is centered on the Old Courthouse, immediately to the west, where slaves were auctioned and Dred Scott tried his case twice. Ahead of me stretches downtown, Pruitt-Igoe, Forest Park, my university, my neighborhood, a number of private places. What was once the world’s largest wheel no longer rises over the fairgrounds—after the Fair, it was dynamited, its countless perfect spokes twisted and heaped. The remains were sold for scrap, but the wheel’s seventy-ton axle—then the largest piece of forged steel in the world—remains missing to this day.

The arch is centered on the Old Courthouse, immediately to the west, where slaves were auctioned and Dred Scott tried his case twice. Ahead of me stretches downtown, Pruitt-Igoe, Forest Park, my university, my neighborhood, a number of private places. What was once the world’s largest wheel no longer rises over the fairgrounds—after the Fair, it was dynamited, its countless perfect spokes twisted and heaped. The remains were sold for scrap, but the wheel’s seventy-ton axle—then the largest piece of forged steel in the world—remains missing to this day.

Behind me stretches the swollen, brown Mississippi, well above flood stage, having already swallowed the lip of downtown. On a submerged street, a stop sign lists with the current. Muddy water laps up the steps leading to the arch, as if to reclaim it. Across the river rise a casino, grain elevators, an American flag, and the train yards and telephone poles of East St. Louis.

* * *

Most of Pruitt-Igoe has returned to the wilderness. The land sat unused until 1989, when fourteen acres became a public school site that still houses magnet middle and elementary schools. The remaining thirty-three acres have become an abandoned urban forest bound by an easily and—judging by the total collapse in some places—frequently scaled chain-link fence. An access road leads to an electrical substation on the site; a chain dangles between two short poles, blocking the way, another gate swung shut: “Danger: Keep Out.”

* * *

Even after the Fair ended, visitors returned to wander the empty paths. One woman wrote her husband that she was “heart sick to see the ruin and desolation”—but she could almost imagine herself still at the Fair.

* * *

Here’s the thing: the Arch is beautiful. Before moving to town, I dismissed it as a hulking piece of modern midcentury kitsch—a civic branding tool, the stuff of bad airport T-shirts and mugs. But for more than a year the arch has watched over me, and while there are places in my neighborhood and on campus where I know to look for it, I often find myself catching an unexpected glimpse and—shocked back down to size—experience a jolt of the sublime. It is not unlike what used to happen with the Trade Center Towers. The arch is machined, perfect, soaring—the city’s greatest open gate. It changes color with the weather and hour: sometimes sky blue, sometimes gunmetal gray, sometimes pitch black.

The arch has no keystone; the north and south legs are of equal length. You’re either on one side or the other. Arches, it should be noted, hold themselves up: they rise on their own weight, they compress—higher pieces push down and out on those below. Some five-hundred tons of pressure were needed to pry the legs apart to install the final four-foot piece. That’s why the windows are so small: to preserve the structural integrity—a wider view would cause the whole thing to crash down. The National Park website lists the exact mathematical equation that describes the arch, but it never was a pure construct: it sits eighteen degrees askew from the north-south axis and sways some eighteen inches, like a chain or a gate. That fact does not comfort me when the wind blows, or even on a clear day like today. The balance is an illusion. I stand at a tense threshold—atop the tallest manmade monument in the country—upheld, for now, by forces great and unseen.

Read part one of this essay here.

Edward McPherson is the author of Buster Keaton: Tempest in a Flat Hat and The Backwash Squeeze and Other Improbable Feats. He has written for the New York Times Magazine, the New York Observer, Salon, The American Scholar, The Gettysburg Review, Epoch, Esopus, and Talk, among others. He teaches in the creative writing program at Washington University in St. Louis.

February 14, 2014

Nastia Denisova, St. Petersburg, Russia

I’ve been living here for four months. The center of the city. Fifth floor. I usually look out the window at night, but it’s not exactly a window—it’s the door of a balcony. I can see all the windows of the building opposite mine.

I see how, from a window on the right, they regularly throw out plastic bags of trash onto the roof of the one-story building in the courtyard. But I don’t know from which window, exactly—I follow the bags, and when I shift my gaze to the windows they’re all closed, identical, except for the one that has a piece of green plywood instead of glass.

From a window on the left side of the building, people throw garbage without bags. Brown plastic beer bottles and, for some reason, heaps of metal tops from jars of homemade preserves. I see the man who throws all this from the window of his kitchen, leaning out the window and looking down. He looks down and spits. His cigarette butt has set some dead grass on fire. He spits for a very long time. He goes out and comes back with a bottle of water. He pours down the water. He throws the bottle out.

In the windows of the second floor are the kitchen and the back rooms of a restaurant. They’re always throwing cardboard boxes out the windows. When the boxes start to block the little back courtyard, someone piles them up and they disappear. In the winter, covered in snow, the boxes become monolithic, angular snow architecture. And if you didn’t already know, you wouldn’t be able to say what they are.

From the window opposite me, cheerful teenagers fling DVDs. Maybe it’s a dorm room. Are they using them like throwing stars, or just tossing DVDs out the window? Have they noticed me? Two discs land on the balcony, through the door that I’ve been watching. Someone has drawn large, colorful butterflies on their surface. —Nastia Denisova

Translated from the Russian by Sophie Pinkham.

What We’re Loving (The Love Edition)

Photo: Seyed Mostafa Zamani, via Flickr

“As usual, the love plot is the least convincing aspect of the book,” said my friend, handing me a crumbling, loved-to-death copy of Barbara Pym’s last novel, A Few Green Leaves. It is not clear to me which part my friend found unconvincing—the growing attraction between the meek, widowed rector Tom and the awkward anthropologist Emma, or the obstacles to their match. (E.g.: Tom’s dreary sister, a visit from Emma’s old flame Graham, or the Oxfordshire village full of aging gossips who have nothing better to do than monitor the hand-delivery of casseroles to local bachelors.) At any rate, I bought the whole thing, and I believed that Emma did, too. As Pym’s narrator observes, “Even the most cynical and sophisticated woman is not, at times, altogether out of sympathy with the ideas of the romantic novelist.” —Lorin Stein

The weather yesterday was awful; this incessant wintry-mix business has got to stop. It has me thinking about Russian poems set during the siege of Leningrad, and last night my brain produced one of the most incredible jump shots since 2001: A Space Odyssey—from Boris Pasternak to Guns N’ Roses. The former has a poem that begins “February. Get ink and weep! / To write and write of February / like bursting into sobs, with thundering / slush burning in black spring.” Naturally, that led to “So never mind the darkness / We still can find a way / ’Cause nothin’ lasts forever / Even cold November rain.” The latter seems somehow right today—it’s a song, after all, about the vagaries of love. In fact, the classic Guns N’ Roses catalogue is brimming with Valentine’s Day–appropriate songs: charged lyrics for lovers (“Said, woman, take it slow / And it’ll work itself out fine / All we need is just a little patience”) and the lovelorn (“To think the one you love / could hurt you now / Is a little hard to believe / But everybody darlin’ sometimes / Bites the hand that feeds”). —Nicole Rudick

Some advice: Run, do not walk, to your love’s home. Take her by the hand and recite this Restoration-era poem about premature ejaculation: “The Imperfect Enjoyment,” by John Wilmot, the Earl of Rochester, a legendary libertine who slept his way around the Royal Court and succumbed, at age thirty-three, to venereal disease. Here, in words as lewd and depraved as anything uttered in 2014, he recounts one of his less inspiring performances. Making love, he can’t quite contain himself, and “In liquid raptures I dissolve all o’er, / Melt into sperm, and spend at every pore.” His lady unsatisfied, he finds himself unable to get it up again, and lambasts his errant penis. “Worst part of me, and henceforth hated most, / Through all the town a common fucking-post.” If that doesn’t make her swoon, gents, nothing will. —Dan Piepenbring

When Dan asked us to recommend love-themed staff picks, I was all set to talk about one of my favorite films, the 1945 Powell-Pressburger classic I Know Where I’m Going! Then I saw it described by Vanity Fair as “a cult among poetic bluestockings” and my enthusiasm dimmed somewhat. But it deserves whatever following it has—incidentally, Pauline Kael and Martin Scorsese are in the cult, too—and I can’t think of a more romantic movie than this tale of a willful young woman stranded in the Scottish Hebrides. (When I describe it like that, I can see why the poetic bluestockings are so excited, but don’t let that put you off!) —Sadie Stein

A few years ago I hosted a Valentine’s Day party for which I insisted that everyone read a love poem aloud. I cannot say this made me popular, but it certainly made for some rapid cocktail consumption. After a few sonnets and even some haikus, the guy I had a not-so-secret crush on read André Breton’s “Free Union” (L’Union libre, 1931), which begins, “My wife with hair of burning splinters / With thoughts of summer lightning / With hour-glass waist / My wife with the waist of an otter between the tiger’s teeth.” By the time he got to “My wife with her submarine molehill breasts / My wife with breasts of the ruby’s crucible / With breasts of phantom of roses under dew,” I wasn’t the only one with a crush. —Rachel Abramowitz

Slate Vault’s tweet says it all: “Pound’s directions to Yeats’s house, drawn up for Robert Frost.” As Dartmouth College’s Rauner Special Collections Library blog comments, “When Pound was helping Frost make the connections he needed to establish himself as a poet, he set up a meeting for Frost with W.B. Yeats. This postcard is an artifact of the meeting.” While the document has nothing to do with romance, Frost’s reflections on his long-time “bromance” with Pound in our Art of Poetry interview are full of wonderful tidbits. My favorite: “[Pound]’s review had something to do with the beginning of my reputation. I’ve always felt a little romantic about all that–that queer adventure he gave me.” —Justin Alvarez

Alain de Botton’s The Romantic Movement gives off the impression of being a literary Jolly Rancher. At least, the edition I have does: bright pink cover, slanted typeface, and the subtitle “Sex, Shopping, and the Novel.” The story is simple: in London, Alice, a cripplingly reflexive dreamer/ad exec in London meets Eric, a handsome, astute banker, at exactly the moment she was beginning to lose all hope of finding her one and only. Botton takes us through their relationship using graphs, philosophical references from Plato to Kierkegaard, and relentlessly honest insights on every aspect of being single and in a relationship. This is a love story told, not shown—and much better for it. Had Botton followed that beginners’ writers’ workshop advice, we’d have something blander than a Jolly Rancher, but no less trite. —Nikkitha Bakshani

In my mother’s faith, you become a man at thirteen, and there’s a ceremony to prove it. For my bar mitzvah, we hung colorful scrims from the rafters of the multi-purpose room in my synagogue. I had to dance the slow dances, and the girls had to say yes to me—it was my party. That would embolden a certain kind of boy, but I stayed literally at arms length whenever I danced, my hands safely above the girls’ hips. Three days later, Twista, Jamie Foxx, and Kanye West released “Slow Jamz,” and while I don’t know for certain how that song would have changed my party, I know it changed my life: I requested it to be played for a girl on MTV’s TRL and my request was granted. I sat close to the television, as if it were one of those lights Alaskans use to survive winter. Every time I hear “Slow Jamz,” I think about the younger me, who believed the song would finally make a girl notice him. But how could it? I never told her I’d requested it. —Zack Newick

Is it V-day or B’Day? Single ladies, drunk-in-love ladies, and divas already know: tonight Cobble Hill’s own Brucie will host a Beyoncé-themed Valentine’s Day dinner. While entrée names like Breastiny’s Child and I Am Pasta Fierce don’t exactly whet the appetite, the menu is pretty humorous (if only because of how willfully tacky it is). —Caitlin Youngquist

Open Ye Gates! Swing Wide Ye Portals!

St. Louis turns 250 today—or is it tomorrow? A two-part series on the city’s 1904 World’s Fair.

Temple of Mirth, 1904 World’s Fair.

I hand the attendant a fifty-cent piece and watch him drop it into the automatic turnstile, itself a marvel. Behind me, the murmur of moneychangers, the swish of gored skirts tapering to white shirtwaists. Beyond that, the din of St. Louis. My sack suit rustles as I stride ahead. I’m crossing the threshold of an impossible city: a manicured wonderland of symmetrical lagoons winding through sculpted gardens studded with allegorical statues. In the distance loom the massive palaces of learning, their Beaux-Arts façades harkening back to Ancient Rome and heralding a future brighter than the hundred thousand incandescent lights that line them against the night. The words of Exposition President David R. Francis ring in my ears—Open ye gates! Swing wide ye portals! Enter herein ye sons of man, and behold the achievements of your race! Learn the lesson here taught and gather from it inspiration for still greater accomplishments!—and I step into the Fair.

* * *

St. Louis is a city of gates that do not normally swing wide. The urban private street, or “private place,” is believed to be a local invention, dating to the 1850s. Private places are owned by their residents, who typically build and maintain the road, median, sidewalks, curbs, street lighting, and—most crucially—gates. Some gates were utilitarian, imposing, and plain; others were small castles, complete with clock towers, fountains, statues, gaslights, and gatehouse apartments that caretakers (and, later, college students) lived in until the 1980s. Private places offered a refuge from the ever-booming city, a world apart. Some have been razed, their gates uprooted, the neighborhoods now troubled by crime; many still stand, pockets of wealth and privilege, with boards of trustees that oversee matters of law (historic preservation, landscaping) and etiquette (street parking, book clubs, Easter egg hunts).

Nearly two years ago, when my wife and I were moving to town and looking for an apartment, we were taken aback: everywhere, gates, gates, gates. Gates that lock and unlock according to byzantine schedules publicized only to residents (thus thwarting commuters and anyone else who might try to cut through the neighborhood). Gates that open by remote control. Rolling metal gates with yellow hazard signs. Gates built for carriages that now barely fit a car. Even in less-rarified neighborhoods—with weeds in the lawns and unwashed economy sedans on the street—at the end of the block might stand a pitiful sawhorse made of white PVC pipe. A symbol that speaks to the natives. Private Street: Not Thru. Private Street: No Public Parking. No thru traffic. Private neighborhood. No smoking beyond this gate. Private. No trespassing. Keep Out.

* * *

The Louisiana Purchase Exposition, popularly known as the 1904 World’s Fair, opened in St. Louis on April 30, one hundred and one years to the day after the signing of the Louisiana Purchase Treaty. Before a crowd of 187,793 people, John Philip Sousa’s band played the “Star Spangled Banner,” five hundred choristers sang the “Hymn of the West,” the fair’s official song, and—from the East Room of the White House—President Theodore Roosevelt touched the gold telegraph key that sent the signal to unfurl ten-thousand flags and begin pumping ninety-thousand gallons of water a minute down the three terraced “cascades” that flowed into the Grand Basin, where four fountains threw water seventy-five feet into the air at the foot of Festival Hall. It was the centerpiece of the fair, a building that boasted—in addition to the world’s biggest organ—a gold-leafed dome larger than St. Peter’s.

At first glance, the Fair offered a spectacle of size, a vision of man’s enlightened expansion into—and conquest of—untrammeled space (recalling contemporary notions of the Louisiana Purchase itself). The fairgrounds occupied 1,272 acres—double the size of the famed 1893 Chicago World’s Fair—spilling out of the city’s giant Forest Park onto the campus of Washington University and neighborhoods to the south. Twenty thousand people would live and work on the grounds. In preparation, crews straightened and buried a river in sixty-five days. They built 1,576 buildings, plus a garbage plant, sewer, post office, press pavilion, telegraph stations, pay telephones, and 125 eateries that could feed 36,650 people at one time. Five of the restaurants could seat more than two-thousand people. Visitors ate everything from filet mignon to frankfurters, fried frog legs to caviar, plus international delights such as Japanese sukiyaki, Mexican guacamole, Indian curry, and Egyptian molokheya soup. To drink: 1893 Louis Roederer Brut Champagne (six dollars a quart), mineral water (sixty-five cents), or Jameson’s Whiskey (fifteen cents a shot), not to mention—this being St. Louis—plenty of beer. There were five fire engine houses and thirty-six miles of pipe serving a network of sprinklers and hydrants, some of which to this day still dot Forest Park, popping up incongruously on the golf course.

The great distances between attractions made the Fair taxing to navigate. Visitors traveled by intramural railroad, a trolley that trundled twelve miles per hour through seventeen stops; they boated along the mile-and-a-half system of lagoons in gondolas or swan and serpent boats. They rented a rickshaw or wheelchair, with or without a guide to push; drove a car; or, if the mood struck, rode a camel, burro, or giant turtle. The official guide claimed a “brief survey” of the wonders would require a minimum of ten days and fifty bucks.

The colossal exhibit palaces were built of yellow pine and ivory-colored “staff,” a mixture of plaster and hemp that could be easily molded, sliced, sanded, and sawed. On average, eighteen trains of forty cars each were needed to haul the materials for a single palace. There were some seventy-thousand exhibits from fifty-three foreign countries and forty-three states (plus more than a few territories and businesses). The Fair offered a taxonomy of knowledge: exhibits were sorted into departments that were divided into groups that were subdivided into 807 classes, an encyclopedic education open to all and structured to create, in the words of the director of exhibits, “a properly balanced citizen capable of progress.” The goal: to show civilization marching proudly in a direction. The faith: that from the artifacts of the past one could draw a line to the future. In practice, the Fair fostered fierce national competition under the banner of international exchange. Proudly on display: progressivism, nationalism, exoticism, racism, hucksterism, humiliation.

The Fair’s president, David R. Francis—local businessman, Democrat, former St. Louis mayor, the state governor who failed to win the bid to host the 1893 Exposition, and now, eleven years later, one of the most-photographed men in the country—would proclaim of his fair: “So thoroughly did it represent the world’s civilizations, that if all man’s other works were by some unspeakable catastrophe blotted out, the records established at this Exposition by the assembled nations would afford the necessary standards for the rebuilding of our entire civilization.” A time of optimism, these years between the Gilded Age and the First World War.

* * *

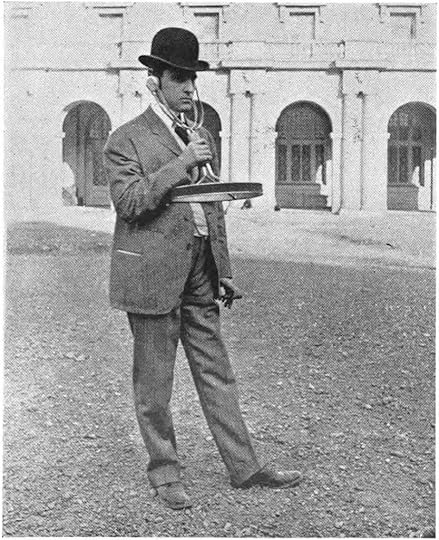

One of the earliest prototype wireless phones, the hPhone.

I wander the palaces, open from nine until dusk. Afterward, I walk the grounds until half an hour before midnight, when the Fair lights are gradually, almost imperceptibly dimmed to dark.

The Palace of Electricity is a cathedral of dynamos, motors, rheostats, transformers, and vacuum tubes. I touch the wall. The building hums. Meanwhile, I am speechless before the radiophone—sound transmitted over a beam of light! They are perfecting wireless telegraphy. I fling a message to Kansas City: “Wish you were here.” A man offers to show me the power of lightning. His companion says he can record and replay voices on a steel wire. Lights are everywhere—big, small, colorful, and bright. Inventors claim soon our homes will have wall outlets. I ponder the mysteries of electromagnetism, electrochemistry, electro-therapeutics, and electric cooking. A hefty gent clutches his wife: “Steak done in six minutes—lobster broiled in twelve!”

The central court bustles with crowds that circle aimlessly, heads bent. The yard is silent save for small, exultant sighs. A man bumps into me and, with a nod, moves on. He is wearing earpieces that sprout from a curious wheel he holds in one hand. A dusty farmer takes off his hat, then puts it on again—over and over, an incredulous, unconscious salute. An old woman stands on her toes, as if straining to the heavens. A little girl holds her skirt, her mouth hanging open.

* * *

In the 1944 MGM musical, Meet Me in St. Louis, Judy Garland plays a young spitfire trying to snare the boy next door in the months leading up to the 1904 World’s Fair. The Exposition’s unofficial anthem—“Meet Me in St. Louis, Louis,” a ditty about a man who returns home to find his sweetheart has fled their humdrum life for the bright lights of the Fair—can be heard at least six times in the film’s first five minutes. (To this day, the song turns up all over town; at my first hometown baseball game, I was not surprised to be led, on the jumbo screen, in a sing-along by the St. Louis Symphony clad in Cardinal red.)

The exposition saw almost twenty million visitors during its seven-month run—about 100,000 a day. (On weekends, trains to the fairground left downtown’s Union Station on the minute.) The Fair offered an unparalleled economic boon to the city that had lost the chance to host the 1893 Columbian Exposition to its great Midwestern rival, Chicago. In 1904, St. Louis was the nation’s fourth largest city, centrally located on America’s two largest rivers, a rail and river hub that—according to the official Fair guide—claimed the biggest brewery, tobacco factory, cracker factory, and chemical manufacturing plant in the country; the largest brickworks and electric plant on the continent; and one of the grandest shoe operations in the world. The city also churned out hardware, drugs, saddles, white lead, jute bagging, hats, gloves, caskets, and streetcars. Its Union Station was the terminus of twenty-seven rail lines; its citizens read nine daily papers. That said, St. Louis had suffered an economic depression from 1893 to 1897 and weathered a bloody strike of streetcar workers in 1900; the local government was plagued by corruption and graft, the city interests run by a cabal of businessmen called “the Big Cinch.” In 1902, McClure’s Magazine dubbed the city one of America’s “worst governed.” For St. Louis’s new Progressive Reform mayor—busy cleaning up the water, air, streets, and government in time for the grand opening—the Fair was a chance at redemption through political force.

Initial funding was raised through federal appropriation, local municipal bonds, and sale of ten-dollar shares of Fair stock to the good people of St. Louis. The Exposition was meant to honor the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, itself a shrewd deal, the U.S. government shelling out fifteen million to France for what would become thirteen states west of the Mississippi. Due to delays, the Fair missed the anniversary, which gave St. Louis the chance to steal—after threatening to hold its own rival athletic games—the previously scheduled 1904 Olympics from Chicago. The Fair would have it all, including sweet revenge.

* * *

The Colonnade of States at the World’s Fair.

I stroll the “Model Street,” block after perfect block courtesy of the Municipal Improvement Section of the Department of Social Economy. A man loafs on the wide lawn, his collar open, before a guardsman tells him to keep moving. I pass a town hall, a hospital, a civic pride monument, and a playground, where lost children are gathered. By the end of the Fair, all 1,166 of them will have found their way home. For a small fee, a woman checks her two-week-old infant with a nurse. She waves: “Mother will be back soon!”

* * *

The Fair’s fanned grounds—laid out by George Kessler, the architect of Kansas City’s parks and boulevards—offered a mix of the urban and pastoral. The landscape was strewn with 1,200 staff statues that, according to the Chief of Sculpture, aimed “to create a picture of surpassing beauty and to express in the most noble form which human mind and skill can devise, the joy of the American people at the triumphant progress of the principles of liberty westward across the continent of America”—though at least one fairgoer sniffed, “It is a pity that there are so many statues exhibited even on the grounds absolutely naked.”

Only twenty-five years old when Fair construction began, Forest Park was a wilderness still in the process of being uplifted. The fairgrounds began as more forest than park. In September 1901, President Francis and his party of VIPs were an hour late to ceremonially drive the first stake because they were lost in the wilds of the park’s northwest corner. Then steam shovels moved earth and hills, lakes were drained and century-old trees felled. Despite the exposition company’s contractual obligation—spelled out in 1901 St. Louis Ordinance 20412—to restore the park to its original form within a year of the Fair, there was no going back. Forest Park had become a groomed urban oasis, and wrangling between the city and the company lasted for years.

* * *

I pay fifty cents and step into the sky, courtesy of the Giant Observation Wheel, the invention of Mr. George Washington Gale Ferris, who envisioned a perfect circle spinning above the plain. After sixty of us crowd inside the cabin, a giddy couple announces they will be married at the top. They’re both sitting on ponies. A piano stands in the corner. The guard tells me he’s seen it all. Yesterday, a female daredevil made an entire revolution standing atop a car. A few cabins below, fashionable ladies and gents are enjoying a private banquet. The wheel is so quiet we can hear the tinkling piano as we’re swung twenty-five stories into the air. I can see the whole world: the Grand Trianon of Versailles, Charlottenburg Castle, the Orangery at Kensington Palace, a Roman villa, a Chinese summer palace, Robert Burns’ Cottage, and the homes of Andrew Jackson, Jefferson Davis, and Thomas Jefferson—all of them rebuilt at the Fair. A city of replicas, a cosmopolitan capital forged of iron will.

* * *

The lore of the Fair claims many firsts: the debut of Dr. Pepper, the ice cream cone (known as “World’s Fair Cornucopias”), iced tea, hotdogs, hamburgers, cotton candy (aka “Fairy Floss”)—but these items were merely popularized and not, as legend might have it, invented at the Fair. There were several true firsts: the first appearance of puffed rice cereal, which the Quaker Oats Company shot out of eight cannons every fifty minutes; the first large-scale cast of Rodin’s Thinker; the first participation from China in an exposition; the first Japanese garden in America; the first time British troops paraded on U.S. soil since the Revolution.

Perhaps foremost: the first Olympic Games played in the U.S., which also saw the first gold, silver, and bronze medals handed out and took place in the first concrete and steel stadium, Washington University’s Francis Field, which had room for fifteen thousand. Competitors from the U.S. and eleven foreign nations set thirteen Olympic records in twenty-two official events.

Notable performances included a gymnast, George Eyser, whose wooden leg didn’t prevent him from winning six medals, three of them gold, and an unsportsmanlike brawl after the fifty-yard swim. But the most memorable event was the marathon, which was run August 30 at three o’clock the afternoon in ninety-degree heat over tough terrain and dusty roads. There were only two chances for fresh water—at six and twelve miles—in deference to the head of the Department of Physical Culture’s amateur scientific interest in dehydration. Fewer than half of the thirty-two participants crossed the finish line. Runners were plagued by traffic, hills, and cheating. (The first man to return to the stadium received a wreath from Alice Roosevelt, daughter of the president, before it was revealed he had ridden eleven miles in a car.) The true victor, Thomas Hicks, pride of the Cambridge YMCA, ran a time of 3:28, though aided by brandy, raw eggs, and the stimulant/rat poison strychnine. After being sponged by his supporters with hot water from a car radiator, he had to be carried, hallucinating and shuffling his feet in the air, across the finish line. He had lost eight pounds.

* * *

Education was the theme of the Fair—which was meant to be “an international university” concerned not with commerce but knowledge—but not all exhibits were meant to uplift. More liberal entertainment could be found on the mile-and-a-half-long midway called the Pike, whose battle reenactments, hootchy-kootchy girls, ragtime rhythms, and flights of wild fancy were outside the purview of the Bureau of Music and the Department of Art. The Old Plantation featured log cabins and cakewalking “slaves.” The Jerusalem recreation was said to include 1,000 natives of the city, though one magazine reporter found a fellow from Hoboken. Battle Abbey included cycloramas of the battles of Gettysburg, New Orleans, and Manila, plus Custer’s Last Stand. Jim Key, the educated horse, could spell and sort mail. He was not the only equine wonder; in the Boer War reenactment, even the horses played dead.

On the Pike, one visitor observed, “No respect was shown to age or dignity, no mercy to starch and feathers.” Couples might be accosted by bands of dancing young men, and “every stiff hat was a target for the inflated bladder” (or water balloon). The same fairgoer wrote in his memoir, “I believe if the Pike had been a mile longer it would have led to hell.”

Later, he recanted: “And yet I had a desire to imbibe a little of the spirit of the Pike. I wanted to be a boy again. Be a little bit bad perhaps.”

This essay’s second part will be published on Sunday.

Edward McPherson is the author of Buster Keaton: Tempest in a Flat Hat and The Backwash Squeeze and Other Improbable Feats. He has written for the New York Times Magazine, the New York Observer, I.D., Esopus, Salon, and Talk, among others. He teaches in the creative writing program at Washington University in St. Louis.

R. S. Thomas’s “Luminary”

Photo: André Mouraux, via Flickr

I wrote in my journal, “It is Valentine’s Day. Very good weather. I walked through Central Park feeling lonely and benign and so happy for everyone I saw who was in love, or starting to be in love. I have come to accept that that kind of thing is not meant for me, but that is not a sad thought: there are many ways to love, and be loved, and live a rich life anyway. I will be okay!” I was eighteen.

At the time, I didn’t know the poem “Luminary” by R. S. Thomas; I wish I had. A friend would introduce me to his work the next year. This poem, which so captures a certain wistful quality, came to me even later; it is one of the “rediscovered poems” anthologized a few years ago with Thomas’s other uncollected works.

Those who know Thomas will recognize certain tropes: the elevation of the natural, the suspicion of institutions and “the Machine.” But it is, first and foremost, a love poem. “My balance / of joy in a world / that has gone off joy’s / standard.”

Romantic, yes, but as even I recognized as a melodramatic spinster of eighteen, romance and love can coexist quite comfortably. This poem, to me, conjures both.

My luminary,

my morning and evening

star. My light at noon

when there is no sun

and the sky lowers. My balance

of joy in a world

that has gone off joy’s

standard. Yours the face

that young I recognised

as though I had known you

of old. Come, my eyes

said, out into the morning

of a world whose dew

waits for your footprint.

Before a green altar

with the thrush for priest

I took those gossamer

vows that neither the Church

could stale nor the Machine

tarnish, that with the years

have grown hard as flint,

lighter than platinum

on our ringless fingers.

That’s a No-No

Choosing your own erotic destiny, or trying to.

Panel from Secret Hearts No. 111, April 1966.

A few nights ago, I was in a world-class sushi restaurant, holding a radish shaped like a rose and contemplating my next move. Koji, the head chef, had carved the radish-rose for me moments ago, after a game of strip poker that ended with him fucking me in the dining room. Earlier that night, I’d adjourned to a lavish hotel suite to suck tequila from a rock star’s navel; a renowned fashion photographer had taken pictures of my genitals and gone down on me in his darkroom, where I’d blurted without thinking, “God, I’m so wet!”; and I’d indulged in a little tasteful S&M with my friend’s older boss, spanking his firm, muscled, George Clooney-ish buttocks with a schoolteacher’s ruler.

Now I felt trapped, denatured, and sort of bored.

A Girl Walks into a Bar is a new choose-your-own-adventure-style erotic novel in which “YOU make the decisions.” YOU, in this case, was me—I was calling the shots in this vale of thrills. I’d picked up Girl in pursuit of cheap gender-bending laughs, but I also had what you might charitably call an anthropological curiosity. In the wake of Fifty Shades of Grey, I wanted to see: What did a mainstream erotic novel look like?

Written by three South African women under the pseudonym Helena S. Paige, A Girl Walks into a Bar markets itself as an empowerment agent. “YOUR FANTASY, YOUR RULES. YOU DECIDE HOW THE NIGHT WILL END,” its cover says. (Another new novel with a similar conceit, Follow Your Fantasy, suggests, “Even if you choose submission, the control is still all yours.”) But by promising refuge for the powerless, the publishers reveal something much sadder—the subtext of these proclamations is that control, especially for women, is simply too hard to come by in the real world. One might as well get one’s kicks elsewhere. When you print “YOU DECIDE HOW THE NIGHT WILL END” on the front of a work of fiction, you imply that women are not often afforded the pleasure of doing so.

Unfortunately, they’re not afforded that pleasure here, either. On the face of it, the choose-your-own-adventure format seems like an ideal vehicle for erotica—it frees you from the shackles of linear storytelling, allowing you to choose the road less traveled, the orifice less penetrated, whatever—but in practice, it’s more claustrophobic than a conventional erotic novel would be. Someone else has invented all the prompts. What you can’t do becomes just as central to the experience as what you can; you’re more aware of the narrative cage when its nuts and bolts are exposed.

And so the book, nominally a tribute to free will, ends up enforcing a kind of erotic determinism. The fantasy isn’t yours at all—from page one, you’re predestined to act within its narrow parameters. The first choice you’re given, for instance: What kind of underwear do you want to put on before you go out on the town? You can choose a purple lacy G-string, “granny panties,” control-top underwear, or nothing at all. No matter what, though, you’ll end up in the purple G-string; pick any of the others and you’re greeted with a page of awkward exposition, the upshot of which is, you didn’t really want that, anyway.

Well, of course you didn’t. The authors will need to mention your underwear in later chapters, and they can’t produce four panty-dependent iterations of the same scene. Which makes you wonder: why bother to provide the illusion of a choice you intend to deny?

When it comes to the lovemaking itself, things are even more vexed. Tired mores come into play. In one scenario, Charlie, the drummer for “the Space Cowboys”—you’re spared, mercifully, the option of perusing their discography—invites you into his shower, which offers an enchanting view of the skyline. He asks you, gently, to pee on him. Not only are you denied the choice to say yes—you’re not permitted to decline gracefully. “You thought that was something people only did if they’d been stung by jellyfish.” Your only recourse is to sneak out, “laughing hysterically as you picture Charlie turning into a prune in the shower.”

That is not my fantasy.

Likewise, when Miles, he of the Clooney-ish bod, asks you to insert a ridged dildo in him, your assent leads only to a rebuke from the authors: “Noooooooooooooooooooo! Are you out of your mind? No way are you doing that!”

The last thing Girl really wants is for you to let your imagination run wild. The book presents itself as transgressive, but it delights in telling you how far you should want to go. Even among consenting adults, it suggests, there are certain thresholds one must not cross. And it’s not just your sexual palate that’s vanilla: Given the chance to try tuna eyeballs, a Japanese delicacy, your only response is, “That’s just too disgusting for words!”

* * *

The Choose Your Own Adventure concept was invented by Edward Packard; when he was telling his daughters a bedtime story, he found himself low on ideas, and asked them what should happen next. He wrote the first book in the series, The Cave of Time, published in 1979; the novels went on to sell more than 250 million copies, launching a long fascination with interactive entertainment: interactive movies, interactive video games, and plenty of interactive erotica.

The choose-your-own conceit is intuitive for kids, who have a nascent, flexible sense of themselves, and for whom the power to decide, even between simple binaries, can yield a deep satisfaction. And it has an understandable appeal for adults, who may yearn to escape, particularly sexually, from the people they’ve become. But it also reminds me of why the second-person perspective is such a literary gambit: its persistent you is unusually invasive. And if you don’t like who you are, it can come to feel like a bad body swap.

In A Girl Walks Into a Bar, my persona frustrated and disquieted me. I was not the kind of woman I wanted to be. I was materialistic: “You’re sure one of these is worth the GDP of a small country.” “You tap glasses and take a sip. It’s good. Tastes expensive.” “You’ve always wanted a chandelier in your bathroom.” And I’d cultivated no interests or skills; I’d learned them all from men. Though I could identify, and drive, a sleek, limited-edition sports car, “you only recognize it because one of your exes … subjected you to thousands of hours of sports-car porn.”

And then there was my taste in partners. My new you, my me, lusted only for trysts with wealthy, banal, hyperbolically successful, presumably white men. (The novel grants you the chance for a lesbian tryst, but the whole affair is pretty vanilla, and peppered with self-congratulation: “You have to admit that you’re fascinated. And her boobs are absolutely luscious.”)

I was plunged into an oubliette of rock-hard cocks, rippling abs, and oceanic orgasms. My night came to seem like one protracted counterfactual. It was everything I never would’ve done; it was everything I did. You’ve decided to take a shower with a rock star. You’ve decided to share a taxi with the sexy older guy. You decide to go with the bodyguard on his mysterious errand.

For readers of any age, gender, or sexual orientation, A Girl Walks into a Bar is a master class in one of life’s hardest lessons: no matter how many options you think you have, total control is always beyond your grasp. There are limits to who you can be. You may never pee on anyone. You may never eat the eyeballs or fuck an interesting person. You will always be constrained by life’s purple G-string.

But for Girl’s perceived readership, I admit, that might be the point: to uphold convention, to flirt with the unknown while still clinging to all that’s safe and solid. The original Choose Your Own Adventure novel boasted more than forty endings; this book has only two. In the first, you go home, make some popcorn—“the buttered kind, you’ve earned it”—and watch Bridget Jones’s Diary in your pajamas. In the second, you tuck yourself into bed with a vibrator. That’s your binary. You can watch TV or you can masturbate. Either decision yields the same final sentences: “Life is good. In fact, it doesn’t get better than this.” Let’s hope it does.

Darling, Come Back, and Other News

Photo: Jnlin, via Wikimedia Commons

In Taiwan, a commemorative Valentine’s Day train ticket sold out in less than an hour: it takes you from “Dalin (大林, pronounced similarly to ‘darling’ in English) station in Chiayi County to Gueilai (歸來, literally: ‘come back’).” A journey any of us should be willing to make after we’ve behaved badly. It’s love on a real train.

Voltaire in love: “She understands Newton, she despises superstition and in short she makes me happy.”

But we can count on literature to remind us that things are not always so sweet. Here are the ten unhappiest marriages in fiction.

Can atrocity be the subject matter of poetry? Our poetry editor, Robyn Creswell, on Carolyn Forché’s new anthology.

“I also like to catch dangling modifiers, because we all miss those … I have had authors who say that dangling modifiers are part of their style and don’t want to change them.” An interview with a crackerjack copyeditor.

February 13, 2014

How Mechanical Rubber Goods Are Made

It’s late, and you’re still awake. Allow us to help with Sleep Aid, a new series devoted to curing insomnia with the dullest, most soporific prose available in the public domain. Tonight’s prescription: “How Mechanical Rubber Goods Are Made,” first published in the Scientific American Supplement on February 13, 1892.

Christian Krohg, Sleeping Mother with Child, 1883.

While the manufacture of rubber goods is in no sense a secret industry, the majority of buyers and users of such goods have never stepped inside of a rubber mill, and many have very crude ideas as to how the goods are made up. In ordinary garden hose, for instance, the process is as follows: The inner tubing is made of a strip of rubber fifty feet in length, which is laid on a long zinc-covered table and its edges drawn together over a hose pole. The cover, which is of what is called “friction,” that is cloth with rubber forced through its meshes, comes to the hose maker in strips, cut on the bias, which are wound around the outside of the tube and adhere tightly to it. The hose pole is then put in something like a fifty foot lathe, and while the pole revolves slowly, it is tightly wrapped with strips of cloth, in order that it may not get out of shape while undergoing the process of vulcanizing. When a number of these hose poles have been covered in this way they are laid in a pan set on trucks and are then run into a long boiler, shut in, and live steam is turned on. When the goods are cured steam is blown off, the vulcanizer opened and the cloths are removed. The hose is then slipped off the pole by forcing air from a compressor between the rubber and the hose pole. This, of course, is what is known as hose that has a seam in it.

For seamless hose the tube is made in a tubing machine and slipped upon the hose pole by reversing the process that is used in removing hose by air compression. In other words, a knot is tied in one end of the fifty foot tube and the other end is placed against the hose pole and being carefully inflated with air it is slipped on without the least trouble. For various kinds of hose the processes vary, and there are machines for winding with wire and intricate processes for the heavy grades of suction hose, etc. For steam hose, brewers’, and acid hose, special resisting compounds are used, that as a rule are the secrets of the various manufacturers. Cotton hose is woven through machines expressly designed for that purpose, and afterward has a half-cured rubber tube drawn through it. One end is then securely stopped up and the other end forced on a cone through which steam is introduced to the inside of the hose, forcing the rubber against the cotton cover, finishing the cure and fixing it firmly in its place.

CORRUGATED MATTING.

After the mixing of the compound and the calendering, that is the spreading it in sheets, the great roll of rubber and cloth that is to be made into corrugated matting is sent to the pressman. Here it is hung in a rack and fifteen or twenty feet of it drawn between the plates of the huge hydraulic steam press. The bottom plate of this press is grooved its whole length, so that when the upper platen is let down the plain sheet of rubber is forced into the grooves and the corrugations are formed. While in that position steam is let into the upper and lower platens and the matting is cured. After it has been in there the proper time, cold water is let into the press, it is cooled off, and the upper platen being raised, it is ready to come out. A simple device for loosening the matting from the grooves into which it has been forced is a long steel rod, with a handle on one hand like an auger handle, which, being introduced under the edge and twisted, allows the air to enter with it and releases it from the mould.

PACKING.

Sheet packing is often times made in a press, like corrugated matting. The varieties, however, known as gum core have to go through a different process. Usually a core is squirted through a tube machine and the outside covering of jute or cotton, or whatever the fabric may be, is put on by a braider or is wrapped about it somewhat after the manner of the old fashioned cloth-wrapped tubing. The fabric is either treated with some heat-resisting mixture or something that is a lubricant, plumbago and oil being the compound. Other packings are made from the ends of belts cut out in a circular form and treated with a lubricant. There are scores of styles that make special claims for excellences that are made in a variety of ways, but as a rule the general system as outlined above is followed.

JAR RINGS.

The old fashioned way of making jar rings was first to take a large mandrel and wrap it around with a sheet of compounded rubber until the thickness of the ring was secured. It was then held in place by a further wrapping of cloth, vulcanized, put in a lathe and cut up into rings by hand. That manner of procedure, however, was too slow, and it is to-day done almost wholly by machinery. For example, the rubber is squirted out of a mammoth tubing machine in the shape of a huge tube, then slipped on a mandrel and vulcanized. It is then put in an automatic lathe and revolving swiftly is brought against a sharp knife blade which cuts ring after ring until the whole is consumed, without any handling or watching.

Still awake? Read more here.

“Snow Is a Hat Worn By Mountains”

Some might suggest that for a literary blog to feature three snow-related posts in a day is excessive. Well, tough. The weather has always been a great common denominator. And to our credit, we’ve refrained from calling this “Winter Storm Pax” or “the snowpocalyse.” We have standards.