The Paris Review's Blog, page 735

February 20, 2014

Keep Smiling

For the origins of the selfie, look to the dandy.

Honoré Daumier, Dandy, oil on canvas, 1871.

When selfie was crowned the Word of 2013 by the Oxford Dictionaries, the media reaction ranged from apocalyptic to cautiously optimistic. For the Calgary Herald’s Andrew Cohen, “selfie culture” represents the “critical mass” of selfish entitlement; for Navneet Alang in the Globe and Mail, selfies are inextricable from the need for self-expression, a “reminder of what it means to be human.” For the Guardian’s Jonathan Freedland, the selfie is both: at once “the ultimate emblem of the age of narcissism” and a function of the “timeless human need to connect.”

With a few exceptions, commentators tended to converge on one point: the selfie, and the unencumbered act of self-creation it represents, is unmistakably of our time, shorthand for a whole host of cultural tropes wedded to the era of the smartphone. As Jennifer O’Connell, writing for the Irish Times, puts it: “It’s hard to think of a more appropriate—or more depressing—symbol of the kind of society we have become. We are living in an age of narcissism, an age in which only our best, most attractive, most carefully constructed selves are presented to the world.”

But our obsession with the power of self-creation—and its symbiotic relationship with the technology that makes it possible—is hardly new. Even the “selfie artist” is hardly a creation of 2013. Its genesis isn’t in the iPhone, but in the painted portrait: not among the Twitterati, but among the silk-waistcoated dandies of nineteenth-century Paris.

It may seem like a stretch to mention selfie artists like Kim Kardashian or James Franco in the same breath as, for example, the French writer Jules-Amédée Barbey d’Aurevilly, but today’s self-creators owe more to d’Aurevilly's view of the power of public image than you might think. For d’Aurevilly and his ilk—recently celebrated in coffee-table book I Am Dandy, which profiles “modern-day” dandies from across the globe, dandyism was about more than mere sartorial elegance. It was a way of consciously existing in the world.

And d’Aurevilly existed more consciously than most. His clothing was as legendary as his writing. He famously kept a collection of bejeweled walking sticks in his front parlor and informed journalists that his favorite was to be referred to as “ma femme.” His 1844 hagiography of Beau Brummel, a dandy of another age, doubles as a manifesto: in his eyes, the true dandy evokes surprise, emotion, and passion in others, but remains entirely insensible himself, producing an effect to which he alone remains immune. D’Aurevilly's celebration of the dandy at times borders on idolatry: for d’Aurevilly, dandies are “those miniature Gods, who always try to create surprise by remaining impassive.”

Charles Baudelaire goes still further, treating dandyism in his 1863 essay “The Painter of Modern Life” as “a kind of religion.” Like d’Aurevilly, Baudelaire sees the ultimate dandy as transcending his humanity—by choosing and creating his own identity, he remains splendidly aloof, unaffected by others or by the world at large. “It is the pleasure of causing surprise in others, and the proud satisfaction of never showing any oneself. A dandy may be blasé, he may even suffer pain, but in the latter case he will keep smiling, like the Spartan under the bite of the fox.”

Baudelaire takes pains to emphasize that the popular trappings of dandyism—“clothes and material elegance”—are secondary to the philosophy underpinning them. “For the perfect dandy,” he writes, “these things are no more than the symbol of the aristocratic superiority of his mind.” Clothing, makeup, intentionally confounding accessories—all these are useful not for themselves but for the role they play in creating a public persona.

Such a view of self-creation is at once attractive and unsettling. To be a dandy, in Baudelaire’s view, is to be utterly free: to produce only the effect one chooses, to exist in the world as a kind of eternal subject, ever operating, never operated upon. Yet such power is granted only to a privileged few. It’s predicated on the troubling notion that these masters of artifice are inherently superior to the “masses”; that this is not only inevitable but desirable. The common man, after all, cannot create his own identity—he’s too busy being subjected to the great and brutalizing forces of biology and economics. The aristocrat alone is allowed the privilege of self-fashioning. To be a dandy is to exist in opposition to “the masses,” to treat them, at best, as a kind of captive audience.

* * *

One of the best portraits of the cult of dandyism, perched uncomfortably between satire and sincerity, can be found in the 1876 short story “Deshoulières,” by Jean Richepin. The title character, the “dandy of the unpredictable,” is brilliant and bored; he lives in terror of being pigeonholed by others. “Having dabbled in nearly everything—arts, letters, pleasures—he had forged for himself an ideal, that consisted in being unpredictable in everything.” Deshoulières lives by the maxim that “one should never look like oneself”; he applies false hair and makeup to alter his appearance and confound his peers. He has the potential to be a great artist or writer, but he cannot bear the “vulgarity” involved in committing to a single activity, and hence becoming “predictable” to the common man. Instead, he decides on a whim to be a great criminal, hoping to alleviate his ennui that way. He proceeds to dispassionately murder his mistress, have her embalmed, and live quite happily (if disturbingly) as her lover until he is finally caught, at which point, fearing that working on a defense would be far too ordinary, he spends his time in jail “classifying and codifying the mysteries of animal magnetism, and of transforming this dense philosophical treatise into a sequence of monosyllabic sonnets.” Despite this, Deshoulières is almost acquitted. Not content with that victory, however, he stands up in the courtroom and condemns the poor arguments of the prosecutor. Even his final execution, Richepin tells us, is original: he leans back so that the guillotine can slice his head rather than his neck.

Here, the dandyist obsession with the freedom to fashion one’s own identity is taken to the extreme. Every element of Deshoulières's identity is constructed for maximum effect. He is less a human being than an artistic rendering of one: a selfie in three dimensions.

Such existence comes at a spiritual cost. Deshoulières can commit to no meaningful course of action, because to be committed is to be predictable, and hence no longer free. He is incapable of love, or of any real emotion. In this, he echoes d’Aurevilly, who included love in his list of things his ideal dandy should avoid: “For to love, even in the least lofty acceptation of the word—to desire—is always to depend, to be slave of one’s desire. The arms that clasp you the most tenderly are still a chain.”

* * *

For all their obsession with freedom, these dandies are wedded, at least, to their environment. Dandies exist in a particular urban context—one in which a growing bourgeoisie accumulates the time to sit in cafés and watch these dandies strut by, along with the ability to afford the kind of bespoke suits and tailored waistcoats d’Aurevilly so adored. The possibility of being subsumed into an anonymous urban mass fills the dandy with terror, but that mass, with its disposable income and its penchant for reading the gossip column in newspapers, gives the dandy an audience to “effect.” An 1886 newspaper article about d’Aurevilly informs us that “his costume is his hobby and, though he would prefer that only his talent should be talked about, the masses know him rather by this and his general reputation for eccentricity than by his writings, which are only appreciated by the literati.”

The dandy may live in horror of “the masses,” seeking the original and the bespoke over the common or the factory-produced, but it’s mass production that enables him to embrace artifice over reality. Technology at once threatens the dandy with anonymity and provides him with the tools to distinguish himself from “the rest.”

In J. K. Huysmans’s 1884 novel, Against Nature—which owes a great debt to Baudelaire and d’Aurevilly—Jean des Esseintes, a dyspeptic aesthete, takes the project of self-creation to the extreme: he shuts himself up in a country estate in which everything is artificial and tailored to his liking, from the mechanical flowers to the jewel-encrusted tortoise. Artificiality, des Esseintes tells us, is the next stage of man’s development.

Nature had had her day … By the disgusting sameness of her landscapes and skies, she had once for all wearied the considerate patience of aesthetes … What a monotonous storehouse of fields and trees! What a banal agency of mountains and seas! There is not one of her inventions, no matter how subtle or imposing it may be, which human genius cannot create; no Fontainebleau forest, no moonlight which a scenic setting flooded with electricity cannot produce … this eternal, driveling, old woman is no longer admired by true artists, and the moment has come to replace her by artifice.

Like the Romantics of the early nineteenth century, des Esseintes seeks to escape the uniformity and reproducibility of the modern age, desperately craving something original. But, unlike a Keats or a Shelley, he finds respite not in the power of nature, but rather in the potential of human intelligence: he escapes the overcrowded Paris technology has built by applying technology, appropriating the “human genius” designed into a tool for the creation of his environment alone. In this, des Esseintes is not only of his time, but entirely of ours.

The selfie, no less than d’Aurevilly’s collection of bejeweled walking sticks or des Esseintes’s customized country estate, represents a thrilling possibility: that one can, with the help of technology, create his identity, triumph over nature, and “produce an effect” while remaining at a safe remove behind his computer screen. Selfies are, in a way, a more egalitarian take on the dandy’s notion of self-creation—they’ve made Baudelaire’s snobbish “aristocratic superiority of the mind” more widely accessible. And unlike Deshoulières, who defined himself solely in opposition to a nebulous “mass” worthy of neither respect nor love, today’s selfie artists are less aristocratic than democratic: the cultivated self, and the power to share that self publicly, is available to anyone with a camera and an Internet connection.

Likewise, the relationship between performer and observer, dandy and people-watcher, is no longer as one-sided as that envisioned by d’Aurevilly or Baudelaire. The possibility of a retweet, a “like,” or a reply allows for a degree of vulnerability that curtails the excessive impassivity of a Deshoulières. Our self-presentation—increasingly intersubjective—becomes more of a self-offering.

The idea of a democratized dandy might well have been d’Aurevilly’s worst nightmare. But every era gets the dandy it deserves. If Deshoulières is the dandy of 1876, then Kim Kardashian—surgically altered beyond Deshoulières’s most dizzying fantasies, taking a selfie, running it through various filters, posting it on Instagram, and receiving three thousand meticulously composed selfies in reply—is the dandy of 2014. In the hands of the many, the act of self-creation becomes not a narcissistic act of superiority, but a human expression of all we have in common. We all have the capacity to tell our own life stories, and we all fear that these stories will end up lost in the crowd.

Tara Isabella Burton’s work has appeared or is forthcoming at National Geographic Traveler, the Atlantic, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Guernica, and more. Her first novel, The Snake Eaters, was recently longlisted for the 2013 Mslexia Novel Competition. She is currently working on a doctorate in French decadence and theology as a Clarendon Scholar at Trinity College, Oxford.

Futurama

A still from Dave Fleischer’s All’s Fair at the Fair, 1928.

I am writing this from mid-air, having checked in via a code on my phone, and am generally feeling very much like an Art Deco cartoon. The Future is here. It is more like the past and the present than we expected.

There was a day on which two things happened. First, I went to see an exhibition about the 1939 World’s Fair. It featured a life-size replica of Elektro the Smoking Robot, and the famous Futurama Pavilion, and in general the Art Deco marvel that was visionary designer Norman Bel Geddes’s masterpiece was beautifully evoked. (Incidentally, for a thorough account of Geddes’s creative process, check out the terrific Barbara Alexandra Szerlip on his game design and the Chrysler Airflow.)

The exhibit was also attended by a group of young people, maybe undergrads, all of them aggressively and meticulously dressed in vintage finery. There were boys in tweed caps and sport shoes and pressed, high-waisted trousers, and girls with perfect pin curls and matte red lips. The commitment was impressive. Their interest in this particular exhibition seemed natural. I tried to stick close to them, as they added a certain air to the proceedings. But then I heard one boy say, “Wait, who was Herbert Hoover?” Still, they took careful notes on the clothes and the aesthetic, and I was glad they were there.

After the museum I went to get a cup of coffee at a nearby diner. There was a young couple at the next table, this one completely modern in dress. I heard the girl say to the boy, “The thing is, computers are the new slaves. We insult them and yell at them. We treat them like inanimate objects.”

And the boy said, “Yeah, yeah, that’s really interesting.” Which, in its way, was true.

I don’t want you to think I didn’t love all these young people, because I did. The name of the exhibition was “I Have Seen the Future,” and that day, it felt apt.

Attention, Angelenos: We Are in Your Fair City

Photo: John Taylor

As New York’s brutal winter wends its way onward, ever onward, two among us have had the good sense to go West: our John Jeremiah Sullivan and Lorin Stein have absconded to LA, which reliable sources indicate is sunny, balmy, and unspeakably pleasant. The two of them are probably, at this very moment, tooling around in a slick late-model convertible and soaking up rays, the reflection of the Hollywood sign visible in the lenses of their Wayfarers.

But they have a job to do: tonight, at 7:30 P.M., Sullivan will give a reading as part of the Hammer Museum’s Some Favorite Writers series, where he’ll be joined by Stein. The event is free, and given how wonderful it must feel to be in Los Angeles, you can expect both gentlemen to be in top form. Go!

The Italian Futurists Are Coming, and Other News

Ivo Pannaggi, Speeding Train, 1922.

Why can some people remember their dreams while others can’t?

And a note to perennial dreamers: positive thinking makes you less successful. In a two-year study of undergraduates, “those who harbored positive fantasies put in fewer job applications, received fewer job offers, and ultimately earned lower salaries.” And those were German students—not a people given to excessive sunniness. You can imagine what this means for Americans.

The authors of old weather proverbs, on the other hand, were deeply pessimistic, especially about the omens of cats: “When cats sneeze it is a sign of rain. When cats lie on their head with mouth turned up expect a storm. When cats are snoring, foul weather follows.”

One reason to attend your son’s football games: you may meet John Grisham there, and he may offer to be your mentor.

“Italy’s relationship to modernity is very complicated … [The Futurists] try to do something new and not repeat what’s already been done, but in the end you can’t shake off 2,000+ years of art and culture.” On the Guggenheim’s new Italian Futurism exhibit.

February 19, 2014

Paperback Writer

Happy 50th birthday, Jonathan Lethem!

Photo: Fred Benenson

INTERVIEWER

You don’t seem to have bothered to rebel against your parents’ milieu—their bohemianism, their leftism.

LETHEM

I tried. It’s very hard to rebel against parents whose lives are so full and creative and brilliant—the option is my generation’s joke: the rebel stockbroker. That wasn’t for me. I wanted what my parents had, but I needed to rebel by picking a déclassé art career. My father came from the great modernist tradition, and so I found a way, briefly, to disappoint him, to dodge his sense of esteem. Very briefly. He caught on soon enough that what I was doing was still an art practice more or less in his vein.

I felt I ought to thrive on my fate as an outsider. Being a paperback writer was meant to be part of that. I really, genuinely wanted to be published in shabby pocket-sized editions and be neglected—and then discovered and vindicated when I was fifty. To honor, by doing so, Charles Willeford and Philip K. Dick and Patricia Highsmith and Thomas Disch, these exiles within their own culture. I felt that was the only honorable path.

—Jonathan Lethem, the Art of Fiction No. 177

It’s All Lustful to Me

Georgia’s obscene novels.

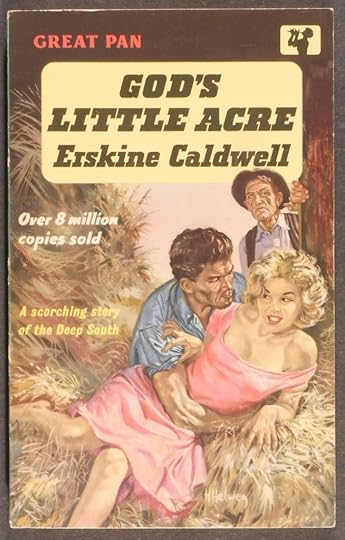

From a foreign edition of Erskine Caldwell’s God’s Little Acre

Sixty-one years ago today, on February 19, 1953, the State of Georgia approved the formation of the first-ever literature censorship board in the United States. It went by the misleading name of the Georgia Literature Commission, and its humble charge was to stamp out obscenity in all of the myriad and insidious forms it took in our nation’s periodicals and publications. The Washington Post has an excellent gloss on the commission, which persevered for some twenty years, despite having been mired in controversy from its inception. James P. Wesberry, the committee’s chairman—and not coincidentally a Baptist preacher—found himself ridiculed by the national press when, soon after the committee’s formation, he said, “I don’t discriminate between nude women, whether they are art or not. It’s all lustful to me.”

Thus, with God and a pure, unyielding ignorance on his side, Wesberry developed an eight-question checklist with which to gauge literature for obscenity:

1. What is the general and dominant theme?

2. What degree of sincerity of purpose is evident?

3. What is the literary or scientific worth?

4. What channels of distribution are employed?

5. What are contemporary attitudes of reasonable men toward such matters?

6. What types of readers may reasonably be expected to peruse the publication?

7. Is there evidence of pornographic intent?

8. What impression will be created in the mind of the reader, upon reading the work as a whole?

(One imagines that question seven did most of the heavy lifting—the committee probably skipped ahead to that one, much as a wayward youth would skip ahead to the prurient bits in a girlie mag.)

Erskine Caldwell’s God’s Little Acre was the first book to be suggested for censorship, in 1957; The Catcher in the Rye and The Naked and the Dead were also deemed obscene. For the most part, though, the commission went after dime-store sleaze like Alan Marshall’s Sin Whisper—when they banned that title, the battle went all the way to the Supreme Court, which overturned the decision. By 1971, the whole commission seemed kind of silly. When Jimmy Carter, he who had lusted after women in his heart, was governor, he slashed the commission’s funding, and by 1973 it was no more. Still, when you see the lurid covers of these novels, you’ll understand why they were believed to corrupt and deprave. Here are some of the books the committee found too debauched for the public consumption:

Reese Hayes, Turbulent Daughters

Reese Hayes, Turbulent Daughters

Peggy Swan, Campus Lust

Peggy Swan, Campus Lust

George H. Smith, Strip Artist

George H. Smith, Strip Artist

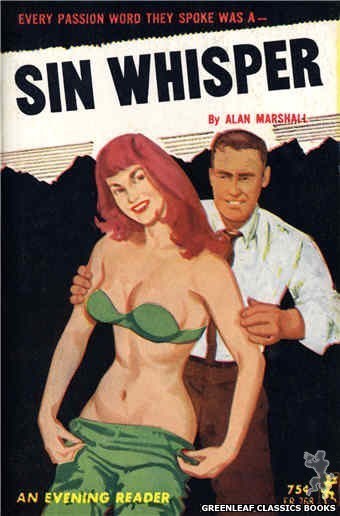

Alan Marshall, Sin Whisper

Alan Marshall, Sin Whisper

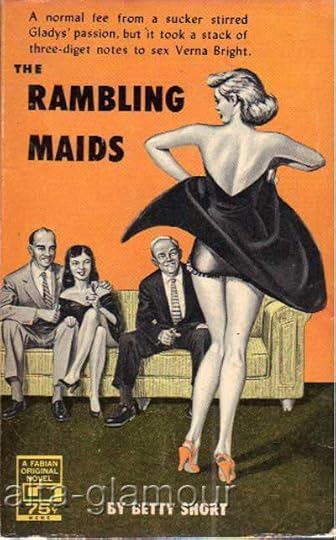

Betty Short, The Rambling Maids

Betty Short, The Rambling Maids

John Dexter, Lust Avenger

John Dexter, Lust Avenger

Erskine Caldwell, God’s Little Acre

Erskine Caldwell, God’s Little Acre

A Public Appeal: Help Me Remember This Book

Assuredly not the book in question.

I throw myself on your mercy, readers.

For some years now, I have been searching fruitlessly for a long-lost book, and I’m hoping someone out there can help me remember the title. The problem is, I have very little to go on: I know it is a paperback career romance from the late fifties or early sixties. I believe it follows the career of an event planner, or maybe an interior decorator. But it is not—I repeat, not—1964’s Weddings by Gwen, in which wedding planner Gwen Wright gets in over her head with a rich family, a dud boyfriend named Steve, and a cockamamie blackmail plot; nor is it One Perfect Rose, from the same year, in which Prill Sage redecorates a Victorian mansion. (Out of scholarly obligation, I reread both, just to make sure.)

Part of the difficulty is that there is a certain, well, formula to the bulk of these career-romance titles. The Julian Messner series—Nancy Runs the Bookmobile; Lady Lawyer; Lee Devins: Copywriter—are sober, conscientious, and informative. Young woman moves to the city, learns about career in mind-numbing detail, has a dull beau, finds satisfaction in work. In the case of the more entertaining but less educational Valentine and Avalon titles—think Dreams to Shatter (pottery) or A Measure of Love (department-store modeling)—the careers are mere backdrops to lurid and implausible romances, skeletons in closets, and Nancy Drew–style investigations.

The mystery book, which I will call Title X, also deals with a scandal subplot of some kind. But in this case, the rich family in question (there is often a rich family in the picture, with a playboy scion who briefly tempts the heroine away from a reliable steady) is concealing a completely different kind of secret: a brother whom they claim is dead. In fact, he is a midget (in the parlance of the times), and has been hidden away on an island or something with a caretaker, even though he is in his thirties and, apparently, of sound mind. At the book’s climactic dénouement, he appears in a limousine, his face “lined with cynicism and dissipation.” That may not be an exact quote, but I know both these descriptors are employed, although everything else about the book is hazy.

“The advantage of a bad memory is that one enjoys several times the same good things for the first time,” said Nietzsche. I am not claiming Title X is a great book, or even a good one. From what little I recall, it is not merely problematic but ludicrous and slightly dull as well. But now, when I look at my shelf of Career Romances for Young Moderns, it feels like something is missing. And rereading the perplexing book is not the sole advantage of the endeavor.

There is something obscurely gratifying, in this day and age, about not being able to track something down instantaneously. Just as there was a strange pathos in that, with the end of the Concorde, we were experiencing the novelty of watching technological progress regress in our lifetimes, so too is there an element of time travel to being really dead-ended by an Internet search. This is an arbitrary consolation.

If you have any leads, won’t you write them below or send them to tips@theparisreview.org?

Writing the Lake Shore Limited

Trains as writers’ garrets.

A postwar ad for the Pennsylvania Railroad.

I am in a little sleeper cabin on a train to Chicago. Framing the window are two plush seats; between them is a small table that you can slide up and out. Its top is a chessboard. Next to one of the chairs is a seat whose top flips up to reveal a toilet, and above that is a “Folding Sink”—something like a Murphy bed with a spigot. There are little cups, little towels, a tiny bar of soap. A sliding door pulls closed and locks with a latch; you can draw the curtains, as I have done, over the two windows pointing out to the corridor. The room is 3’6” by 6’8”. It is efficient and quaint. I am ensconced.

I’m only here for the journey. Soon after I get to Chicago, I’ll board a train and come right back to New York: thirty-nine hours in transit; forty-four, with delays. And I’m here to write: I owe this trip to Alexander Chee, who said in his PEN Ten interview that his favorite place to work was on the train. “I wish Amtrak had residencies for writers,” he said. I did, too, so I tweeted as much, as did a number of other writers; Amtrak got involved and ended up offering me a writers’ residency “test run.” (Disclaimer disclaimed: the trip was free.)

So here I am.

Why do writers find the train such a fruitful work environment? In the wake of Chee’s interview, Evan Smith Rakoff tweeted, “I’ve been on Amtrak a lot lately & love writing while traveling—a set, uninterrupted deadline.” The writer Anne Korkeakivi described train travel as “suspended impregnable time,” combined with “dreamy” forward motion: “like a mantra, it greases the brain.”

In a 2009 piece for The Millions, Emily St. John Mandel describes working on a novel during her morning commute on the New York City subway. “It felt like extra time,” she writes. “I began scrawling fragments of the third novel on folded-up wads of scrap paper, using a book as my desk.” Mandel polled around and found other writers used the subway as a workspace, too. Julie Klam: “Part of the reason I like it is because it has a very distinct end. It’s not like having six hours at home. I tend to have great bursts of inspiration that last about six stops.” Mark Snyder: “I think the act of working, surrounded by other people living their lives, can be quite a compelling act for yourself. It makes me feel less alone.”

These reasons are all undergirded by a sense of safety, borne of boundaries. I’ve always been a claustrophile, and I think that explains some of the appeal—the train is bounded, compartmentalized, and cozily small, like a carrel in a college library. Everything has its place. The towel goes on the ledge beneath the mirror; the sink goes into its hole in the wall; during the day, the bed, which slides down from overhead, slides up into a high pocket of space. There is comfort in the certainty of these arrangements. The journey is bounded, too: I know when it will end. Train time is found time. My main job is to be transported; any reading or writing is extracurricular. The looming pressure of expectation dissolves. And the movement of a train conjures the ultimate sense of protection—being a baby, rocked in a bassinet.

Writing requires a dip into the subconscious. The lockbox, at times kept tightly latched in our daily lives, is pried open, and things leak onto the page that we only half-knew were there. Boundaries help to contain this fearful experience, thereby allowing it to occur. Looking around at my fellow passengers gives me an anchor to the world: my fantasies, my secret desires, aren’t going to get anyone killed. We’re all okay here; we’re all here, here.

* * *

My father is a foamer. That’s the technical term for a rail fan so enthusiastic he foams at the mouth at the sight of a train. There’s a black-and-white photograph of my dad as a child in a onesie, his nose in a book called Wheels and Noises. When I was growing up, he routinely spent weekends “chasing trains,” or driving alongside impressive steam engines and hopping out of the car to film them chugging by. (He still does this.)

His dream, I think, was for my brother and me to grow into fellow foamers. But whereas my dad was fascinated with the mechanics of trains (“note the slender pipes pointing towards the rail in front of each drive wheel,” he wrote in one of his “Train Picture of the Day” emails), my “foaming” is pure emotion. His fascination is with the train itself. My fascination is with me on the train.

My father was so dedicated to his passion that he made trains his job. Throughout my childhood, he traveled weekly to Indiana to manage a particular product line within a freight transportation company: vehicles that were equipped to travel on both road and rail. Something like two decades ago, when my brother and I were children, we accompanied my dad on a trip to the headquarters of his company. On the way home, we rode the Lake Shore Limited, the train I’m on now.

Here are my scattered sense memories of that trip: a sleeper cabin shared with my brother. We slept in bunk beds; my dad slept across the hall. Dinner in the dining car; delight in the compactness and efficiency of our little cabin. A desire to live on this train—but, underneath that, a comfort in the knowledge that we wouldn’t, that the trip had an end, that we would leave, that we’d be home.

Jessica Gross is a writer based in New York City.

Opulence of Twaddle, Penury of Sense, and Other News

Bierce in 1892, barely containing his rage. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

More of Mavis Gallant’s diaries.

“That sovereign of insufferables, Oscar Wilde, has ensued with his opulence of twaddle and his penury of sense. He has mounted his hind legs and blown crass vapidities through the bowel of his neck.” No one spews contumely like Ambrose Bierce spews contumely.

Bret Easton Ellis has written a script for Kanye West. Guess which one said of the other, “I really like him as a person”?

So many movies, novels, and TV shows are set in prison—but do they depict it accurately?

Meet the man who designed David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust outfits. “His interest in Central Asian fabrics led to a coat that can cause car accidents.”

Fuck it—let’s go skiing.

February 18, 2014

Business as Poetry

The poet A. R. Ammons was born on this day in 1926.

Photo: East Carolina University

INTERVIEWER

I know that you worked in your father-in-law’s biological glass factory as a vice president in charge of sales. Were you interested in the work or was it dull?

AMMONS

It wasn’t dull. I have a poem somewhere explaining how running a business is like writing a poem. In business, for example, you bring in the raw materials and then subject them to a certain kind of human change. You introduce the raw materials into a system of order, like the making of a poem, and once the matter is shaped it’s ready to be shipped. I mean, the incoming and outgoing energies have achieved a kind of balance. Believe it or not, I felt completely confident in the work I was doing. And did it, I think, well.

—A. R. Ammons, the Art of Poetry No. 73

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers