The Paris Review's Blog, page 2

September 10, 2025

At the Shakespeare Festival

Photograph by David Schurman Wallace.

A HEY, AND A HO, AND A HEY-NONNY-NO

The old people are going apeshit for the mariachis. My dad and I are sitting on a bench in the plaza at the bottom of the hill, killing time before the next play. We were hoping to do a little reading, but then, under the light of a half moon shaded by trees, the musicians appeared and started playing a promotion for the reopening of a nearby Mexican restaurant. A crowd appeared from thin air: the ranks of the silver-haired and still-fit, the perennial window-shoppers of this cultural oasis, who show more enthusiasm for this advertisement than for any of the Shakespeare plays we’ve been to so far. They take a lot of pictures on their phones of the brass-buttoned musicians, who put in their work. They try to clap along. A couple even dances for a song or two: a dip, a twirl, more applause. Romance never dies—its definition only degrades.

For several years when I was growing up, my family drove to Ashland for the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. In Ashland, the main drag of olde-time, small-town storefronts fold into the surround of rolling evergreen hills; an actual babbling brook, complete with footbridge, runs through it. Ashland is a certain kind of cultural haven for those who mute their wealth tastefully under their shawls. With a complex of three theaters at its heart, it hosts a ninety-year-old institution dedicated to spreading the word of the Bard all summer long. As a child, I was always soothed sitting in the darkness, where everything felt perfectly in order. One scene stitched into the next, the actors hit their lines, and together we headed toward marriage or death.

It began as a nostalgia trip. My parents hadn’t been since before the pandemic, and for me it had been even longer. A combination of COVID and wildfires had threatened to bankrupt the festival, so we agreed it was time to both support and take stock. And my parents are getting older—who knows if we’ll ever do it again. On our drive, we see the dead skeletons of trees still left after the burning, with new greenery coming up in their shadows.

My dad, cheerful enough but fatigued, maybe, from the day’s first show, says that we can just park him anywhere, that he’s going to finish reading tomorrow’s play, August Wilson’s Jitney. I linger with him near the town’s fountain. Ashland is supposedly known for its famous Lithia water. I examine the sign: the natural spring source can poison you (“contains elevated levels of Barium—daily consumption is not recommended”). The town’s founders hoped the water’s alleged healing properties would create a tourist destination, but the water tasted awful and its mineral residue clogged the old pipes. You can still get some at the fountain in the square. I’d describe it as yeasty-tasting with an unpleasant smell. For subsequent tourists, Shakespeare would have to do. People come to be healed in a different way now, to enter the high church of Art, if only to stand around in the back pews for a few minutes.

The band plays on, and my dad tunes it out. We don’t speak. I feel a bit like a Thomas Bernhard character, wallowing in my low opinion of my fellow man. Nothing in particular against mariachis, but this scene is just bulk storage on these people’s devices, never to be looked at again. There’s a Ren Faire energy here now, but without the benefits of the Renaissance. A snatch of trumpet melody from the musicians, just playing their part, becomes another input into the scroll-in-progress. Who will miss all this when it’s gone?

FIRST DAY

One pleasure of Shakespeare is that every era projects itself into him. As the critic Harold Goddard wrote more than seventy-five years ago in The Meaning of Shakespeare (God, if we could name our books so confidently now …), “One by one all the philosophies have been discovered in Shakespeare’s works, and he has been charged—both as virtue and weakness—with having no philosophy. The lawyer believes he must have been a lawyer, the musician a musician, the Catholic a Catholic, the Protestant a Protestant.” In some sense it doesn’t matter what we say about Shakespeare—he gives us an occasion to talk about ourselves. What, then, is the meaning of Shakespeare in the Rogue Valley, a little liberal enclave in the forest?

We arrived in the evening, met my aunt, a therapist who also traveled up for the festivities, and had dinner (along with the best margarita in southern Oregon, some say). Everything in Ashland is encased in the amber of the upper-middlebrow: there’s one fancy hotel with an oddly Palm Springs–esque restaurant, several bistros with so-so food and elaborately-named beers (“Drink Me Potion” Fruited Sour), boutiques where men buy sun-shielding hats and women buy comfortable sandals, and places for people to “nourish themselves with artisan pastries and Direct Trade coffee,” as one bakeshop puts it. The Shakespeare fanfare isn’t too ostentatious around town; the knowing have been coming for years to stay at the Bard’s Inn and the Stratford. At the gift shop, my mom looks for a wacky T-shirt to buy my nephew and complains that the merchandise has become too standardized with the Festival’s logo, presumably an effort to build its Brand. Even if kitsch has been mostly ousted, you can still buy a I READ PAST MY BEDTIME throw pillow or a surplus prop from last year: “take a piece of LIZARD BOY set home with you / $5.00 each.”

The complex of three Shakespeare theaters, including a full reproduction of Shakespeare’s own Globe (a sign in faux-Gothic script proclaims it “America’s First Elizabethan Theatre”) is up a decently steep hill. The complex is efficiently run, with ticket-takers, impromptu music, and restaurants where tired patrons can be easily deposited after their journey in the dark. My dad’s leg is hurting him, so we decide to try out his wheelchair. Over the last few years, both of my parents’ ability to walk long distances has declined. Pushing my father in a wheelchair, even a temporary one, marks the time gone. (The infinitely kind ushers are ready with the kind of chitchat that alleviates some awkwardness—”So sporty that your wheelchair is red!”—and this both soothes and aggravates me.) Being temporary, the chair is also flimsy, not suited for an old public sidewalk, with little wheels that constantly risk lodging the chair in ruts or grooves and throwing my father to the ground. More than once I think I see him putting his head in his hands in what looks to me like a rare sign of emotion.

Filing into the matinee performance of Julius Caesar, what makes the biggest impression on me is the audience. They are old. At least two phones, full-volume ringtone, go off during every performance. As the play progresses, eyes close, postures slouch.

It’s a fairly boilerplate production, except it has an all-woman cast. Maybe because it’s a play so often taught in schools, there’s a temptation to stick to what people know. Brutus is mild, and Caesar has been dressed in white fatigues, a cape, and a red beret, some cross between Las Vegas magician and Hugo Chávez. In a play about empire and insurrection, images of contemporary politics are bound to figure. It’s one of the ways we speak our time into Shakespeare, draw his political imaginary into our own. It leads us back to the particular in the universal, even at the risk of an insipid flattening. (I have attended Shakespeare in the Park and seen the Stacey Abrams sign in a backdrop window, a flourish they repeated the following year when she wasn’t even running for office.) Trump as Caesar, sure. But Caesar is also a figure of illness; he has epilepsy, “the falling sickness.” His body is always betraying his immortal ambitions. Perhaps a little Joe Biden rattling around in there too? But no one goes there. Maybe the production’s limpness—my eyes glaze over during the choreographed fighting and dancing—is in the inability to find a coherent liberal narrative in a play that suggests assassination might be desirable.

Regional theater, man. You want it to continue to exist, but you don’t always want to be the one who has to sit through it. Part of the problem with reading Shakespeare is that performance rarely equals the text. If you see enough plays, you know the standard tactics that productions everywhere use to keep the audience “in it”: shouting as a substitute for passion, leaning heavily on Shakespeare’s bawdy puns (this year we’re spared the actors jerking off in pantomime), enlisting the audience to clap along. The text often gets tweaked to make sure we stay oriented, a bit like bowling with bumpers. The next day, when an actor shouts “Give me a break!” in reply to a fatuous speech, I’m fairly sure the line isn’t one of Shakespeare’s.

I’m disappointed most by the performance of Cassius, that slippery arch-plotter, another of the yellers. Her eyes wide, her teeth bared, she stands firmly planted to deliver her lines. The flip side of Shakespearean universality: there are so many characters who don’t let us understand why they do what they do. When Cassius tells the story of saving Caesar from drowning (“Help me, Cassius, or I sink!”), isn’t there a mysterious hurt there when he says, “Cassius is / A wretched creature and must bend his body / If Caesar carelessly but nod on him”? Caesar is obviously a father figure, striding over us like a Colossus. Set aside the Freudian thing for a moment. Cassius wants power, of course, but there’s more. There’s compassion inside Cassius’s story, the near-tenderness by which body raises body, and the speech shivers to life. It’s a complex feeling to recognize the frailty of your enemy. Even the strongest of us become helpless, often before we realize it. There’s an image from another epic inside Cassius’s speech: Anchises, the father of Aeneas, carried on the back of his son as they leave the burning ruins of Troy. We all swim in the waters of time, and we don’t know when our bodies or minds will give out. Suddenly, we find ourselves carried.

After one of the plays, we squeeze the wheelchair into an elevator with a man in a gray T-shirt. In the way people do when they want to banter in an elevator, he looks at us and says, “It’s like Groucho Marx said about the woman who told him she had ten children: ‘Lady, I love my cigar, but I take it out of my mouth once in a while.’ ” I’m not exactly sure how this relates, but I think about it. I keep thinking about it for a while.

SECOND DAY

I spend most of the morning reading As You Like It in the hotel breakfast area over a plate of powdered eggs. Nobody said I wasn’t a procrastinator. For the matinee, we see Fat Ham, a loose adaptation of Hamlet that won the Pulitzer Prize in 2022. It takes place at a cookout—the family business is barbecue—where the would-be prince is visited by his father in a white sheet with eyeholes. Hamlet is queer, Ophelia is queer, Laertes is queer. Loose reimaginings of Shakespeare can work: Where would the nineties teen romcom be without them? It does surprise me when the lead bursts out into a full rendition of Radiohead’s loser anthem “Creep.” Bizarre, but weirdly effective. The actors sell everything as hard as they can.

At Caesar, an older man—silver-haired in a purple polo shirt, still vigorous—had been sitting behind us, discoursing to his two women companions. “When they talk about ‘woke,’ ” he said, “it means that they feel defensive. They feel bad about themselves, and then they want to take it out on other people.” Maybe, though when I watch these modern renditions, I feel the drip of self-satisfaction more than anything. As long as I’ve been going to see Shakespeare, he has been a harbor for the politically correct. This says something about liberal politics and its seizure of the canon, sure, but it also says something about the playwright’s essential generosity. Call it the “dyer’s hand,” that ability to remove a singular interpretation and let all the dueling voices echo and intertwine. Diversity is inside the plays from the beginning—anyone might inhabit the words and infuse them with their own voice. But in Fat Ham, a direct monologue about inherited intergenerational trauma lands with the thud of received wisdom. The strange friction of Shakespeare’s thinking about fathers and sons is reduced to a formula.

The play winds up with a happy ending (and a drag show to boot), as the characters ask us if we deserve better than tragedy. We’ve been doing this, too, as long as Shakespeare has been performed, perhaps most famously in a 1681 revision of King Lear by Nahum Tate: Cordelia marries Edgar, and everyone can feel good on the way home. I think there’s still something more subversive in Shakespeare’s protean originals. Isn’t Hamlet a little on the side of madness of revenge? Maybe “not to be?” is more than the rhetorical question that we take it for. I’m still waiting for the production that tells me that suicide is painless.

OUR ARDEN

It’s a nearly perfect mid-May evening when we head back up the hill to As You Like It, and I put my back into it. My mother is going with my aunt to a cabaret performance of the musical Waitress. Even at the Shakespeare festival, musicals tend to do a better job of filling the seats. In the theater, it’s another similarly aged audience, with the exception of three millennial jackals that sit behind me and talk through the entire performance. They laugh heartily at the jokes and stage-whisper about how the actor playing Duke Senior looks like Will Forte.

The court of Duke Frederick is minimal. All white benches and backdrop, the nobles and courtiers in white too. For me, there’s only one way to interpret this: the Apple Store. The corrupt court, then, is another boomer nightmare: What’s wrong with my phone? (And why can’t I stop looking at it?) When the play reaches the forest of Arden, a vast carpet rolls down the back wall of the theatre and across the stage floor: soft green shag, bright cartoon flowers. We’re in the hippie sixties, the summer of love, a common choice for productions of As You Like It, which has the most songs of any Shakespeare play (five, perfect for some Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young–style riffs) as well some appropriately one-with-nature rhetoric: “tongues in trees, books in the running brooks, / Sermons in stones, and good in everything.”

Who really knows why Duke Frederick usurps Duke Senior? Why is Olivier determined to put down his brother Orlando, our naïve “hero” so quickly upstaged by Rosalind, his female counterpart? Family antipathy is no more logical than family love—because both ultimately evade our understanding, we accept the comedy’s “unrealistic” twists. Jaques, the play’s melancholy dissenter, is dressed up as Leonard Cohen, in a black suit, black fedora, and sunglasses. Sixties-appropriate, I suppose, but misses the swirl of cynicism that Jaques injects into the would-be Utopia. Everyone knows the famous “All the world’s a stage” speech, or at least the first lines. One might forget: the subject of the rest of the speech is about growing older, as Jaques outlines the seven acts of man’s life. I’ve heard it argued that the speech is really a bit of banal conventional wisdom. But it still ends with force:

Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

As the speech ends, Orlando bursts in, desperate for food after carrying his old servant Adam into the forest with him. In the play, Adam is the true father figure, true to his name, the first man. He has rescued Orlando from his family strife, and now Orlando repays him, making him his family. Apocryphally, this part was played by Shakespeare when As You Like It was originally performed. Adam, though he goes into twilight, is not childish. He lacks neither eyes nor taste, at least for now. After the play, I push my dad home, holding his weight as we move slowly downhill. We all go to bed early.

THIRD DAY

We catch August Wilson’s Jitney for the final matinee. It’s easier for audience and performers alike; it’s skillfully done, and done straight. It’s a bright, hot day, the start of summer, and we take a cab to an extremely early dinner at a farm-to-table restaurant that theatergoers love. My dad, who has finished his reading, expresses great admiration for it. My aunt asks which of the plays was my favorite. I offer some tempered criticisms of each, or they seem so to me, before adding a self-deprecatory caveat: “But I’m a snob, of course.” Everyone agrees, leaving me chagrined. My family, very reasonably, has enjoyed their time here. The quotable chestnuts of Caesar rang out, and Fat Ham thrilled with unexpected song and dance. Since when was it no longer enough to simply sit in the dark and let speech ebb and crest in the mind?

For the next few days, driving home and at my parents’ house, I have a series of dreams. That I’m back in school again, but that I can’t read. That I’m running down a long, dark corridor, with someone coming up behind me. I think back to Julius Caesar. It’s easy to forget how turbulent the play is, especially its first half. Omens and apparitions, strange fires in the sky. A lion walks through the Capitol. While we’re in Ashland, we’re all resting in a dream. A peaceful one, and peaceful perhaps because of its broken relationship to everything beyond these forested hills. The theater has a promise we can’t entirely reach; it bores us, it disappoints us, it can hardly compete with the rush of time. I could complain, but the actors were still there, delivering beautiful lines, upholding something even as it slips away. The darkness there still gathers something difficult, elusive.

During Caesar, I turned to see how my father was doing. I couldn’t tell if his head was slouched because he was looking at the iPad of captions that had been provided for him, or if he had dozed off. I turned towards the rest of the audience, and surely many were resting out there, silver-haired sleepers, soothed by iambic pentameter. I hoped they were having good dreams.

David Schurman Wallace is a writer and editor living in New York City.

September 8, 2025

A Little Ghost, Barbara Guest, and Me

FROM PRABUDDHA DASGUPTA’s portfolio Longing in THE SPRING 2012 ISSUE OF THE PARIS REVIEW.

I don’t love being stoned, but I love being stoned in museums. Cannabis makes me quiet and uncertain, or chatty and self-conscious, which winds back to quiet and uncertain. Alone in a museum, however, the mind’s defenselessness—what divides me from all other objects is, it turns out, as sturdy as a sheet of wet tissue paper—no longer seems dangerous. I drift from room to room, pleased to dissolve into the art.

So, I took a low-dose edible upon arriving at the Museum of Modern Art on a September afternoon two years ago. I was there on assignment to write a poem about a piece in the permanent collection; I’d chosen a collotype by Eadweard Muybridge. As it wasn’t on display, I had an appointment in the photography department. A curator ushered me into a large room, all beige and white. In the center of the room stood a large table and a single chair, angled toward the window, which took up almost the entirety of one wall and looked out onto West Fifty-Third Street. The collotype, sleeved in plastic, lay waiting on the table. Woman Dancing (Fancy), one plate from Muybridge’s massive Animal Locomotion project, shows a woman in diaphanous white twirling across a black background. For an hour I took notes sober, and then, after my thoughts went wispy, for an hour stoned. Across the street, grass sprang from low gray clouds. A roof garden. A pleasant vacancy resolved: done here. I would wander the galleries, I decided, until the edible wore off.

Down a flight of stairs, through an archway, I saw black rotary telephones arranged on plinths. The gallery wasn’t crowded; people moved through it like migrating animals, undistracted from loftier destinations. “Dial-A-Poem,” the wall text, blown up, sans serif, read. I lifted a receiver, thinking of my grandmother, who taught me to dial on her rotary phone. I’d loved the swing and catch, how you had to wait for each electrical pulse to send. It made a game of communication. In 1968, the artist and poet John Giorno created Dial-A-Poem, catchily and accurately named: call a telephone number and listen to a poem read by its author. Giorno got some of the best minds of his generation to contribute: John Ashbery, Diane di Prima, Amiri Baraka … the famous names roll on and on. This room reincarnated a MoMA exhibit, phones randomizing through two hundred poems, from decades earlier. Giorno died in 2019. Now, in my ear, he theatrically elongated an introduction: “Diiiiiaaaaal a Poooome‚” “poem” converted to defiant monosyllable, and “Baaaaarbaraaaa Guest.” Then a woman’s tailored voice took control. People used to apply more drama to enunciation: they both sounded like minor characters in All About Eve or The Philadelphia Story. “Door bells,” Barbara Guest said, divorcing the compound with a pause.

The poem was simple, startling, one minute long. In the words, I recognized the perfect encapsulation of a thought I hadn’t known to think. The experience reminded me of the first time that words in another language became more than sound to me. In the wake of comprehension, I felt starved for more sense. I wanted to listen to it again and again. Wonder is an astonishment that births delight, and then curiosity.

It’s impossible to hold the whole of a poem in your head the first time you hear it. At best, you may hang on to a phrase; if you’re lucky, a whole crystalline image. I hastily typed two lines of this one into my Notes app: “I wish to change the filigree of our subjects” and “beware of intimacy it is only a footbridge.” Guest read another poem, none of which I retained. A pause, like a radio tuned to nothing. The next poem, by someone I’ve forgotten, started. It didn’t matter.

***

Those lines kept their power even after the return of sobriety—even in the B train’s orange envelope, where I first tried to search for the poem’s text, with no luck. I blamed Google’s turn toward uselessness, and the rickety connection on the subway. I’d try again at home. But there I also had no luck, though I tried all the tricks I knew for sifting truth from trash. “I wish to change the filigree of our subjects” ended up in the poem I wrote, which emerged as a headlong tumble, a manic attempt to diagnose and describe the relations between stillness and motion, dance and language, love and violence. When I’d chosen the collotype, I hadn’t known that Muybridge had killed his wife’s lover, and in the poem I made into lyric my entirely prosaic discomfort over the fact that I’d devoted hours of attention to the work of a murderer when my own brother had, two years before, been murdered. I did wish to change the filigree of my subjects: if not to escape the death that governed my thoughts, then at least to dodge the repetition of its old ornaments.

All autumn, I kept telling people about this Barbara Guest poem I’d heard and couldn’t find. Her poetry wasn’t entirely new to me. In graduate school, she’d been the lone woman to appear under “The New York School” on a syllabus. The author of more than twenty poetry collections, many essays, a biography of the poet H.D., an experimental novel, and several plays, she was overshadowed in the classroom discussion by her male contemporaries, Ashbery and the ineradicably popular Frank O’Hara. My obsession might have ebbed into a more reasonable appreciation had I been able to find the text of the poem anywhere. But it couldn’t be found online, nor did it appear in The Collected Poems of Barbara Guest, which I read straight through, in case the poem, or at least some of its lines, appeared under a different title. Nothing. No doorbells. Or door bells.

At first, I read like a student hunting for a suitable quote to squash into an essay, clock ticking down to deadline. Then I simply began to read. In Guest’s poems, the thoughts, impressions, images spring into being the way that God creates in Genesis, unapologetically strange and fully formed: “I am talking to you / With what is left of me written off, / On the cuff, ancestral and vague, / As a monkey walks through the many fires / Of the jungle while a village breathes in its sleep.” Some of the poems hew closer to an O’Hara-esque “I do this, I do that” reportage of turbocharged perception, whereas others draw together fancifulness and the habit of turning matter into metaphysics in the way that a great Ashbery poem does. She interpolates The Tale of Genji and Gertrude Stein as well as the pains of, presumably, her own life: “I am in love with him / Who only among the invited hastens my speech.”

And, throughout, there is art as subject: both the making and the thing made. In these poems, she writes of how “an emphasis falls on reality” through the artist’s way of seeing. If she begins envious of “fair realism,” then soon enough there is no reason for envy, as the real world conforms to the imaginative vision and a “drawn” house becomes real enough to move into, among “the darkened copies of all trees.” There’s a symbiotic grace here, a sense that art and reality are so intertwined that what the poet sees can be reported as calmly as any journalistic observation. A relaxed confidence pervades stanzas like “if I spoke loudly enough, / knowing the arc from real to phantom, / the fall of my voice would be, / a dying brown.” Thus these lines, in context, appear wholly natural yet still surprising. The force that binds and propels the poems never strains after intelligibility. This is the way, in Guest’s imaginative universe, that poetry should be: “Respect your private language,” she instructs in one essay. In her tenacious respect for her own, Guest reminds me of Anne Carson; both are so blithely unconcerned with making sense to anyone but themselves that it isn’t clear they understand the extent of the faith they place in a perfectly personal logic. (The truest believers don’t recognize an alternative to belief.) Guest’s poems, like Ashbery’s, often develop via sound, image, and coincident gesture, and, as with Ashbery’s, meaning seems not irrelevant, exactly, but subsidiary to the primary pleasure, also the primary purpose: language. Gorgeous sentences abound, but the line—“that nude, audacious line,” in Guest’s words—is the star. Compact phrases delight, one after another: “I impart to my silences / operas”; “this pharmacy / turns our desire into medicines and revokes the rain”; “the Church of // Our Lady cried Enough”; “It is the hour for decisions and I am going to take a little nap.” It’s possible to read Guest’s work with no attention to a poem’s larger significance and still feel the distinctive bliss of illumination. As if summoned from another world, a density of ideas and feelings takes shape and then passes, quick as a cloud. Even writing itself renews when the classical Muses return to an earth that is “no longer fragrant” and loose birds in a bedroom near “that old shawl in the corner.” Guest portrays the inspiration that dislodges poems as a dizzying, unrestrained, inexplicable, profane miracle: “The room fills now with feathers, / the birds you have released, Muses, // I want to stop whatever I am doing / and listen to their marvelous hello.”

***

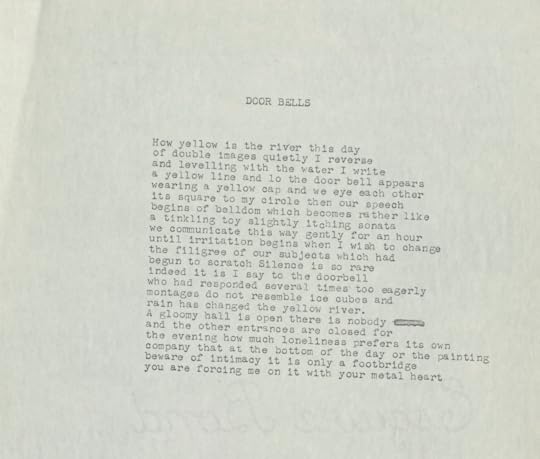

The search for the text of “Doorbells” (“Door Bells”?) became a minor quest running parallel to my real-life commitments. MoMA did not have any texts for the Dial-A-Poem exhibit. Nor did they have digital audio recordings to share. The Dial-A-Poem hotline still exists—at +1 (917) 994-8949—so my best friend and I called and called in an attempt to record the poem so I could transcribe it, but after dialing 103 times and then hanging up before dozens of excellent poems had time to get going, I conceded that this was a flawed strategy. Also, a transcription would offer only the words, and a poem stripped of its line breaks is a mutilated creature. I emailed the John Giorno Foundation, which provided the audio recording. Progress! I could slow it down, replay, get all the words as close to right as possible. Then I located pages in the Barbara Guest archives at Yale University that I thought might be the right poem—right title, right year. These pages had not been digitized or transcribed, so it was merely a list in the online catalogue: three typewritten drafts, box 53. My first impulse was to take the train to New Haven to check for myself, but, after lecturing myself on practicality (I mean really, a whole day spent working toward the possibility of solving a problem I’d created, irrelevant to my life), I settled for requesting a scan from the reference librarians. I waited. And there, at last, it appeared in my inbox as a downloadable PDF: the fulfillment of desire, the end of the quest. “Door Bells,” after all.

Photograph courtesy of the Beinecke Library and the Barbara Guest Estate.

I’d thought I would feel more triumph. As soon as I opened the PDF, my usual mode of textual engagement took over: it was just another poem. It was like starting to date a long-term crush. The fantasy simulacrum collapses, and then a new relationship must begin based on what’s actually there—a realism, fair or not.

***

Door Bells

How yellow is the river this day

of double images quietly I reverse

and levelling with the water I write

a yellow line and lo the door bell appears

wearing a yellow cap and we eye each other

its square to my circle then our speech

begins of belldom which becomes rather like

a tinkling toy slightly itching sonata

we communicate this way gently for an hour

until irritation begins when I wish to change

the filigree of our subjects which had

begun to scratch Silence is so rare

indeed it is I say to the doorbell

who had responded several times too eagerly

montages do not resemble ice cubes and

rain has changed the yellow river.

A gloomy hall is open there is nobody

and the other entrances are closed for

the evening how much loneliness prefers its own

company that at the bottom of the day or the painting

beware of intimacy it is only a footbridge

you are forcing me on it with your metal heart

“The poem begins in silence,” Guest wrote elsewhere, and I read this poem as a disputation with noise, with everything that interferes with the poet’s hearing the poem. That extra space between door and bells emphasizes the threshold’s precarious gap. The bell is embodied, autonomized, but of course a bell rings when a person rings it, and so the poem also engages, obliquely, the problem of human companionship, which a writer both craves and resents. Other people distract the poet from the writing; more dangerously, they may make it impossible to achieve the state of mind—the inner silence—required to write. Still, it is a “gloomy hall” that contains no open doors to other rooms and other lives, and “loneliness,” after all, is Guest’s choice over neutral “solitude.” But if intimacy connects us to others, then how far does that connection extend, and where does it take us? Is the reason to beware intimacy that it cannot take us as far in art as loneliness? Or is the problem that it’s “only a footbridge” rather than a place to arrive? For a writer, for any artist, I think, work and the rest of life, all the love and pain and obligation of personhood, necessarily conflict. The tension Guest enacts here never resolves. It just reiterates. Sometimes you sit with loneliness. Sometimes you obey the metal heart.

I do not know why Guest never included “Door Bells” in a book. Maybe she wrote it for Giorno’s project and never considered it outside that context. (The other poem she read, “Passage,” appears in Moscow Mansions.) Was it discarded or just forgotten? Guest died in 2006, so I can’t ask. She left behind a vast body of work, including a recently released collection of her prose, Meditations, which includes her strange, gifted, koanic essays on writing. A poem, she writes in the essay “Wounded Joy,” is a text that creates a gap between what’s expressed and what can never be expressed that does not attempt to hide this gap from the reader. We are supposed to hear the silence of what cannot be said: “no matter what there is on the written page something appears to be in back of everything that is said, a little ghost. I judge that this ghost is there to remind us there is always more, an elsewhere, a hiddenness, a secondary form of speech, an eye blink.” The poet must neither draw it out nor send it scurrying into the ether. To let it be—that is the crux of the poet’s task: “Leave this little echo to haunt the poem … It has the shape of your own soul as you write.”

***

I cared an inordinate amount about locating this poem. I attributed this to my tendency toward what a poet friend, Jameson Fitzpatrick, calls Rococo plot: harmless flourishes, small dramas, that bedazzle the everyday. The plotter’s drive is to make life, above all, more narratable. Once I invented the dilemma, the story demanded gratification. Rococo plot is a relaxed manifestation of Bovarysme, the term (derived from Flaubert’s tragically deluded Emma Bovary) for daydreaming oneself away from the boredom of reality. Emma’s demise comes via romantic novels, and discussions of Bovarysme treat falling under the influence of literature like taking fentanyl. (An internet-era version of the diagnosis is main character syndrome.) But, as T. S. Eliot noted, this “human will to see things as they are not” is just that: human.

But this answer, the first that came to mind, didn’t seem to quite account for the work, unglamorous and frustrating, I’d done to arrive at the poem. For a while I shrugged off the slight dissonance. Later, I recognized the presence, throughout this hunt, of my own little ghost. I hadn’t meant to write my dead brother into my own poem, but it couldn’t be helped. The grief is no filigree. It’s the form and the subject and the dark matter, too. I’d pursued this quest at least in part because my reality was suffused in a bleakness that I wished to believe was possible to dispel. In working to distract myself from my own thoughts, I also groped after the possibility of understanding and beauty within an everywhere sadness. That now seems the revelation “Door Bells” brought: there is the ineradicable, uneasy coexistence of silence and noise; there is also the ineradicable, uneasy coexistence of art and plain agony. All joy is wounded joy.

Elisa Gonzalez is a poet, fiction writer, and essayist. She is the author of the poetry collection Grand Tour.

September 5, 2025

Making of a Poem: Yongyu Chen on “Outpost”

“This was my desk. Below the window is a children’s playground.”

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets and translators to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Yongyu Chen’s “Outpost” appears in our new Summer issue, no. 252.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase, or something else?

I started this poem in late September in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I came back from a long trip in Asia and was waking early because of the time difference. I felt good! I was writing a lot.

I wrote the first draft after a sequence of experiences that felt like experiences already while I was inside them—starting with meeting, for the first time, a friend’s close friend and ending with a walk home on a gray day, after rain, looking at the oak branches on the ground.

It felt like the feeling of wanting to pick up the oak pieces—and noticing it, then making myself do so—did something to the previous experiences. When I came home, I started writing the poem.

How about the second draft? The third? How many drafts were there, and what were the primary differences between them?

There was one continually evolving draft, which became shorter. Over two months, I also started new poems, and a few layered into this one.

I went to a claire rousay concert—it reminded me of an Ichiko Aoba concert I didn’t go to. The title of one of Aoba’s songs, “Imperial Smoke Town,” became a scene with an ironsmith and feathers and an outpost …

I saw my friend, and we sat on the stairs—there were no seats in the café. People walked between us, up and down. We read a poem by Celan together …

Hölderlin was the last, sudden addition to the poem. I was learning about his walk through the mountains and the gun under his pillow in the cold …

While editing, the word free became important. I was writing a lot, and freedom was what writing felt like to me. I was reading Alice Notley, which freed me to write about more things I notice. I thought that there was something photographic about this loosening, which to me meant writing a lot, just writing what happens, and knowing a lot of it won’t work and that what works will work not because of technique, mainly, but through the assemblage of real things indexed in the poem.

The photographer Moyra Davey once wrote that “accident is the lifeblood of photography.” And “My ratio these days is perhaps one usable frame for every five or ten rolls of film.” In the same text, she quotes Garry Winogrand—“That’s really what photography—still photography—is about. In the simplest sentence, I photograph to find out what something will look like photographed.”

When did you know this poem was finished? Were you right about that? Is it finished, after all?

When I put Hölderlin in, the poem felt finished because doing so felt … like it broke a rule, or inner pattern. He is so historical, graspably real and concrete. That texture finished the poem for me.

The last set of edits were done with the Paris Review poetry editor Chicu Reddy’s suggestions, which tightened the poem. Some of these edits changed or reversed meanings—“No longer remembering” became “Remembering.” Others removed objects which I couldn’t imagine removing, like the hand at the end, on the thigh. I admired those edits because I couldn’t have made them, from within the logic of making the poem. They work on the poem and let its meaning change, if necessary. Or maybe the meaning itself needed to be developed for the poem to work, better. These edits were easy to accept because they were sharp, difficult, and not me.

Are there hard and easy poems?

Yes. This one was easy.

Yongyu Chen’s first book of poems, a winner of the 2023 Nightboat Poetry Prize, is forthcoming from Nightboat in spring 2026.

September 4, 2025

A Lyric Nation: On the Uncollected Dream Songs

From “Six American Days and One Night,” a portfolio by David Bowes that appeared in the Spring 1984 issue of The Paris Review.

The United States is a lyric nation. It has a geography suited to epic, and an expanse suited to epic, but it is organized in a lyric way—organizationally, the United States has more in common with Astrophil and Stella than Paradise Lost. Each state is a lyric, and the nation as a whole is a lyric sequence—or, better, a lyric group. That is to say, the United States is many individual poems that can also be understood as one poem. This organizational feature and the resulting constant tension between individual states and the federal government—that the states seem always, even if at times only minimally, to threaten to pull entirely away from the nation—are, I think, among the several reasons that no successful traditional epic poem, no Aeneid, has been produced in the United States (the exception that proves the rule being Alice Notley’s The Descent of Alette, both traditional epic and anti-epic at once). But John Berryman’s The Dream Songs is an epic.

It has taken me years to realize that The Dream Songs is an epic—and a successful, even great one. For years, I searched for the successful traditional epic I felt certain must have been written by an American, and although I more than once encountered poems that seemed to fit the bill formally, none of them seemed an artistic success to me. Most often, they were let down by their language, which was commonly pedestrian, almost as if it were a secondary or even tertiary concern of their authors. But, of course, the language of an epic poem must be, in its way, as compressed as the language of a lyric poem—and in those moments when it is not compressed, the language must strike the reader as relaxed from compression, and loaded with the certainty of future compression. The language of The Dream Songs is always either compressed or suggestive of compression. The poem has this, and little else, in common with traditional epic.

But The Dream Songs also, of course, features a hero, as epics traditionally do—Henry. In his note included with the complete edition of The Dream Songs, Berryman described Henry, and The Dream Songs as a whole:

Many opinions and errors in the Songs are to be referred not to the character Henry, still less to the author, but to the title of the work … The poem then, whatever its wide cast of characters, is essentially about an imaginary character (nor the poet, not me) named Henry, a white American in early middle age sometimes in blackface, who has suffered an irreversible loss and talks about himself sometimes in the first person, sometimes in the third, sometimes even in the second; he has a friend, never named, who addresses him as Mr Bones and variants thereof.

Henry, of course, is no Odysseus, though he more closely resembles Odysseus than all other epic heroes, with the exception of the unnamed protagonist of Dante’s Commedia (indeed, Henry strikes me as a combination of both heroes, but sitting in an armchair, sometimes a desk chair, at the end of a long day, talking, sometimes singing, sometimes shouting, in an otherwise empty room). Henry is an unheroic hero—a heroic hero has in-narrative effects upon the physical world and the people in it; Henry, for the most part, does not. When he does, the reader must take his word for it that he does; he, rather than the narrative of the epic, describes the effects he has. He is, in other words, a twentieth-century white American male, not especially remarkable, the sort of person who doesn’t establish or recover a nation, or parley with angels, or explore hell, but the sort of common person of whom nations are constituted, to whom angels were once commonly believed to minister in small ways, of whom hell was once commonly believed to be full. Henry is a hero for a disenchanted nation, from which once-common beliefs have mostly fled. He does not mourn the disappearance of those beliefs; he has held on to the beliefs he could.

The Dream Songs has no narrative, however, although it features a hero, and it is this lack of a binding narrative that prevented me, and has perhaps prevented others, from recognizing that The Dream Songs is an epic. Just as the United States is an amalgamation of states, The Dream Songs is an amalgamation of lyrics; just as the stories of the states do not melt and vanish into the story of the nation, the lyrics that constitute The Dream Songs do not melt and vanish into it. The states, considered together, give one the idea of the United States, but the single entity that is the United States floats just beyond that idea, whole thanks to the addition of an ineffable element; the individual Songs, considered together, give one an idea of The Dream Songs, but the single entity, the epic, is something more, whole thanks to the additional consideration of Henry as an entity—he is the cover that binds the pages of the book together. And he makes the expansion of the epic with the Songs in the book you are now reading, or hearing, possible.

The Dream Songs is an epic, then, of a representative twentieth-century American mind, and it is important that it is understood to be the mind of a white person. To contemporary readers, Henry’s use of verbal blackface might be off-putting, but it is essential. With Henry’s verbal blackface, Berryman externalizes the racial anxieties of the white, midcentury American. And he seems to do so consciously. As seen above, in his introductory note to The Dream Songs, Berryman made a point of indicating that Henry is white—he wanted his readers to keep that in mind; in the context of the introductory note, he did not allow whiteness to be a default position—and, in his own life, Berryman refused academic jobs in the South because he didn’t like how black people were treated there. I do not here suggest that Berryman was perfectly enlightened with regard to issues of race, but I do believe he recognized race relations as a—perhaps the—central problem for white Americans, the obstacle that the epic hero must think his way through, and I believe he worked to think his way through toward justice.

***

In a 1968 interview with Berryman, Catherine Watson wrote, “Not all the songs about Henry are in the books, Berryman said, but ‘if there is a third volume, it will not take him further. It will be up to the reader to fit those poems in among the published ones.’ ” Berryman understood his epic to be complete, but he did not believe that its completeness could have only one form—although his remark does suggest that it has an established beginning and end; note the phrase, “fit those poems in among.” Only Sing collects 152 possible additions to the epic, each of which is worth reading for its own merits.

Berryman seems to have realized that the Songs he hadn’t included in his complete edition of The Dream Songs would one day be published. In reference to his then unpublished material, he said in a 1967 interview with Elizabeth Nussbaum, “Why should I publish it? I have little need for fame and money at this point. Anyway, somewhere there’s an assistant professor waiting to become an associate professor—and here are my manuscripts.” Apparently, Berryman often contemplated facilitating such an academic transition; he mentions it in other interviews, as well as in Dream Song 373:

will assistant professors become associates

by working on his works?

Although he wondered, he didn’t object. It is often difficult to know whether a deceased author’s unpublished work ought to be published; I think it almost always ought to be, but I can understand why other people think otherwise. However, with regard to Berryman’s unpublished work, there is considerably less ambiguity than one might find with other writers.

And it seems to me the work ought to be published not only because the Songs are good—some of my favorite Berryman poems are in this book, among them “For Louis MacNeice” and the Song beginning “Grim Pilgrims gather: ‘Thanks.’ I give thanks too,” both of which are elegies for friends who were also poets—but also because Berryman is a central poet of his generation. He seems now to reach more readers than his contemporaries, with the possible exception of Elizabeth Bishop. I have seen more people, strangers, reading The Dream Songs in public than any other book of poems. Also—a fact less noted among poets than it ought to have been—every season finale of the HBO show Succession, including the series finale, is titled after a phrase from Berryman’s Dream Song 29.

***

At the beginning of John Haffenden’s introduction to the volume he edited of late poems not included in Berryman’s final books (that volume, currently out of print but not difficult to find used or in libraries, is titled Henry’s Fate), one encounters the following sentences: “This volume of poems, written between 1967 and 1972 … represents only a fraction of Berryman’s unpublished and uncollected work. There are several hundred unpublished Dream Songs, and as many more miscellaneous poems.” Although I had first read Henry’s Fate over a decade ago, it wasn’t until reading it again in 2023 that I realized the “several hundred unpublished Dream Songs, and as many more miscellaneous poems” hadn’t yet been collected, and upon that realization, of course, I tweeted about it, expressing a wish that somebody would collect the unpublished Songs and poems. Soon after I posted that tweet, Christopher Richards, who had edited my memoir, emailed me to suggest I edit a volume of unpublished Berryman myself. The idea first seemed absurd to me, then terrifying, then possible and absurd and terrifying, and I set about trying to make the idea a book. In December of 2025, that book, Only Sing: 152 Uncollected Dream Songs, will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Two of the Songs from the book appear in the Summer 2025 issue of The Paris Review.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. In November of 2023—on the anniversary, although I didn’t know it at the time, of the date on which Berryman wrote Dream Song 29—I flew to Minneapolis for a daylong visit to the Andersen Library Reading Room at the University of Minnesota. There, Erin McBrien, then the interim curator, located the boxes of Berryman’s unpublished material and patiently answered all my questions, and I photographed each of the manuscripts of the unpublished Dream Songs. The next day, I flew home and began transcribing the Songs. Doing so, I made no effort to Americanize Berryman’s spelling—he studied for two years at Clare College, Cambridge, and often favored British spelling—and I left the entirely idiosyncratic spellings and words untouched (one example of the latter: the word sieteus in the poem beginning “Hearkened Henry,” which perhaps ought to be she tells, but is, in fact, sieteus in Berryman’s typescript). I corrected only obvious typos. Once the Songs were transcribed, I had to determine how to arrange them, and I settled upon ordering them alphabetically according to first line. I could not organize them chronologically, because most of them hadn’t been dated by the poet and I didn’t want to guess—my goal was to impose as little of my own will as possible upon the organization of the Songs. However, I have made two exceptions: there are two short sequences of Songs among the Songs collected in Only Sing, one titled “Four Dream Songs,” and one an incomplete group of Songs, each of which is titled “Idyl.” Each group I placed alphabetically according to the first line of the first poem in the group. Although it was Berryman’s practice, when collecting the Dream Songs into books, to group the Songs in numbered sections, I haven’t done so, as to do so would be to impose the will I’m trying to minimize. These Songs are put together in the way that I hope best allows—or at least allows as well as any other way—readers to “fit [them] in among” the already existing Songs, so that each reader might expand the epic according to their own wishes, thereby laying claim to their particular sense of what The Dream Songs is.

Only Sing: 152 Uncollected Dream Songs will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in December.

Shane McCrae’s most recent full-length book is New and Collected Hell, and his most recent chapbook is Two Appearances After the Resurrection. He teaches at Columbia University.

September 3, 2025

Stolen Goods

Berlin’s historic Kaufhaus des Westens (Department Store of the West) with its front gate up. C.Suthorn, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

The border opens, and people from the West bend down from the tailgates of their trucks and give presents to their poor sisters and brothers from the East: Christmas is coming, and they’re giving wrapping paper away for free in the joy of reunification. But now here they come, the evil sisters from the East, the well-educated girls who took piano lessons at home, who know Faust’s final monologue by heart, and they stuff the West into their pockets, they slip sunglasses from Schlecker into their sleeves and music cassettes between the buttons of their jackets, they tie sweaters they haven’t paid for around their waists and even walk around the store with them on, while these things that don’t belong to them slowly absorb the heat of their bodies. Well, that’s just outrageous, these young ladies don’t know what gratitude is (clearly they were completely ruined by the Russians), they come along and just toss cheese, sausage, and coffee, even champagne bottles and chocolate, into their shopping bags, maybe they pay for the three rolls at the top, but then they stroll out of the shopping hall, which is called a supermarket nowadays, with all those other, stolen things bouncing around underneath, and those girls don’t even blush. At home they practice drawing in perspective, but on the Ku’damm they put on expensive fur hats and then leave the store with alabaster faces. These same girls used to have to line up at dawn to get hold of even one copy of The Aesthetics of Resistance by Peter Weiss—and now that they can buy any book they want, they start stealing! The factories in the East are so dilapidated that those people can be happy if someone buys them for one mark: if you want to be able to afford expensive underwear, you have to work first, work until you turn old and gray, until you turn black if you have to, don’t just stuff a bra down the front of your pants until you have a belly, nothing is free anymore, Christmas is over, but they don’t listen, those brash young things, they drive out of the hardware store on riding lawnmowers, right past the salesman, and even give him a friendly nod, if we’re not careful, they’ll rob the West blind. Anno 1990.

Translated from the German by Kurt Beals.

From Things That Disappear , to be published by New Directions in October.

Jenny Erpenbeck was born in East Berlin in 1967. Her most recent novel, Kairos, won the 2024 International Booker Prize.

Kurt Beals is an associate professor in the department of Germanic languages and literatures at Washington University in St. Louis. He has previously translated books by Anja Utler, Regina Ullmann, and Reiner Stach.

September 2, 2025

Intrigue on the Slopes of Bardonecchia

Illustration by Sean Donahue.

When one’s boss says, “We’re goin’ to Italy in January,” one is not in a position to disagree. There is Italy: beautiful. There is the gentle coercion: “We’re goin’.” There are the professional considerations: one’s boss. And there is the mysterious magnetism of the occasion itself: Some sort of conference? For international journalists? And we’ll be skiing the whole time?

“It’ll be a team-building thing,” the boss told Our Journalist over the phone. Something more was said about “networking with the foreign press” and “footing the bill for our airfare,” and Our Journalist soon found himself committed to attending the Ski Club of International Journalists’ seventieth annual meeting.

The boss’s name is Ryan, and he has a way of making things happen. “Inviting Chandler to Italy, so it’ll be the four of us,” he texted a few days later. The fourth person is Valen. They are all young American journalists, and they work for the same magazine. Ryan is the managing editor, Valen and Chandler are contributing writers, and Our Journalist is a modest copy editor. He has gently placed commas into Valen’s and Chandler’s articles.

“Families That Ski Together, Stay Together,” reports the website All Mountain Mamas. Psychology Today declares that “real rewards come when we leave the bunny slopes, both on skis and in life.” Time magazine calls skiing “a Ridiculously Good Workout.” This trip was shaping up to be a real professional and personal boon.

The Ski Club of International Journalists is as real as you or me. It exists not only in the fantasies of frustrated Swiss radio hosts and overworked Kazakhstani investigative reporters but in the Nock Mountains of Austria, the Karawanks of Slovenia, the Mangfall Alps of Germany, and other magnificent alpine ranges, where for seventy winters journalists from all over the world have gathered to ski and drink and bask in conviviality.

As do NATO and the International Olympic Committee, the Ski Club of International Journalists (SCIJ) has as its official languages English and French. As with Aspirin and deconstruction, a Frenchman may be held responsible for this peculiar invention. It was 1955, a tense year. It was the year of the Bern incident, in which a mustachioed Transylvanian sculptor attacked the Romanian embassy in Switzerland. It was the year of the Geneva Summit, in which top leaders from the USSR, the USA, Britain, and France convened in an attempt to soften the international tensions of the Cold War. The year of the Warsaw Pact, in which the Soviet Union and seven Eastern Bloc countries pledged mutual defense. And the year that Gilles de La Rocque, playing his own humble ambassadorial role, convened the first meeting of SCIJ.

Gilles de La Rocque was a journalist of aristocratic origins. He liked to hike and ski. He has been described as romantic. His forehead was high, his nose broad, and his frame in photographs looks slight but sinewy. He sometimes wore a cravat. He fought against the Germans. And after World War II ended, he began working for a daily newspaper in Paris. But his ambitions exceeded the press box: he had a talent for diplomacy, and a disdain for the Iron Curtain dividing Western and Eastern Europe, and these traits collided to create an idea.

“It’s some kind of Boy Scout idea,” La Rocque would say two decades after SCIJ’s founding. The idea was to get journalists from both sides of the Iron Curtain together and put them on skis: Yugoslavs and Swedes, Bulgarians and Brits, all gliding down the same white hill, bridging their countries’ ideological rifts, chipping away at that East-West barrier …

“Mountains bring people together,” La Rocque believed. And they did. From 1955 on, all around Europe the journalists went, to the resorts of Méribel and Zakopane and Bayrischzell and Bad Gastein, talking and skiing under the auspices of SCIJ. Club membership was not individual but, like an intergovernmental organization, a matter of nation-states. Each “Member Nation” would get one captain and one vote in the General Assembly (GA), where club matters would be decided. SCIJ would also be overseen by a kind of executive branch: an International Committee (IC) comprised of a club president and a secretary-general. SCIJ rules on term limits have changed over time, but IC members are currently allowed to serve two three-year terms.

The first SCIJ meeting included eight Member Nations, or national teams: Austria, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, Switzerland, West Germany, and Yugoslavia. Soon enough, Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Czech Republic joined, along with the Brits and Americans. Russia was added in 1960, four years after Team USA. Russia did not always behave. In 1977, its SCIJ team was led by Kremlin officials. The Kremlin’s skiers reportedly spied on their peers.

Nonetheless, SCIJ prospered and grew, during and after the Cold War. It welcomed more nations into its arms. Individual membership reached a thousand. Members roamed the earth, skiing in Québec and Utah and Kazakhstan.

Today, SCIJ has demographics in some ways akin to Italy’s: the old far outnumber the young. In 2024, the average SCIJ member was fifty-five years old. When Our Journalist and his colleagues joined in 2025, the average age went down to fifty-two.

Joining SCIJ is simple. You shell out sixty euros for the membership fee, four hundred euros for the meeting fee, and answer yes to the prompt “More than 80% of my professional compensated activities are from journalism” on the online registration portal. “Journalism” and “80%” are to be understood capaciously: certain members seem to derive their income primarily from flying airplanes, or from practicing law, or from “the industrious nature of my grandparents and parents.” In exchange for the privilege of participating in SCIJ, attendees are expected to write light touristic dispatches about their time at these gatherings, e.g.:

For one surreal, suspended week on an island … borders and age gaps and ideological differences faded into a whipped cream wonderland of camaraderie. (Scott Newman, 27 Rouge; SCIJ 2023, Canada)

We, of course, had a good selection of regional cheeses, but do not think of sophisticated wine-cheese pairings and tastings. Despite being in France, we were usually indulging ourselves in Belgian beer. (Aylin Öney Tan, Hürriyet Daily News; SCIJ 2019, France)

Customs regulations prevented bringing turkey from the US, but the hotel did a commendable job of roasting two large birds. (Leah Larkin, Tales and Travel; SCIJ 2012, Turkey)

Each year, a different Member Nation accepts the responsibility of hosting SCIJ in their country. This year it was Team Italy’s turn. On January 26, 2025, SCIJ celebrated its seventh decade in the Italian alps, in the Susa Valley, in the town of Bardonecchia.

***

Our journalist’s journey to Italy passed pleasantly. He spent part of it catching up on the SCIJ WhatsApp chat, to which he’d just been inducted:

“Dutch pea soup is on its way to Turin.”

“German Currywurst just passed the border to Bella Italia!”

“Oysters and champagne arriving from France!”

“Some Turkish delight to please the sweet tooth!”

The bus then rattled from the airport to its terminus in Turin, and Our Journalist shuffled out to look for the rest of Team USA. He found them by the train station, unloading their gear from a different bus.

Ryan and Valen looked up and grinned.

Valen wore a long dark coat and her hair touched the coat’s fur collar. Ryan was tall and blond and Californian; he had a trim handsome beard and a tan face. Our Journalist hugged his colleagues.

There was an older gentleman with them too. He was dressed formally, in a gray blazer, a white shirt, and a red silk tie patterned with sunflowers. His hair was cut close to his head, his cheeks were stubbled gray, and he bore a certain jolly heft. He told the Americans that he was Bulgarian.

“Let’s fuckin’ go!” said Ryan, as the last of the bags came out of the bus. He put his hands on his hips and sighed happily. “Should we sit down somewhere and have a beer?”

The group found a café inside the train station, and everyone ordered a local IPA.

“What was your name again?” Our Journalist asked the Bulgarian.

“I am Tihomir,” he declared. “But friends call me Tisho. Like … piece of paper for blowing nose.”

The Americans nodded.

“What is your name,” said Tisho.

“Noah,” said Our Journalist.

“Noah. Like the coffin.”

“No,” Our Journalist said, “like the ark.”

Tisho, it emerged from their conversation, was primarily a lawyer. He had a legal column in a newspaper and sometimes wrote reported pieces. His latest article was about Bulgarian expats in Munich who paid steep prices for imported Bulgarian cabbage. Bulgarians preferred Bulgarian cabbage.

“Do you like the Bulgarian State Women’s Choir?” Our Journalist asked. The choir was one of the few things he knew about Tisho’s country.

Tisho frowned. “I prefer Ray Charles. Ray Charles came to Bulgaria.” He smiled. “Tina Turner came to Bulgaria.” He smiled wider. “Rolling Stones”—he scowled and scrunched his face—“do not come. They are my favorite.”

Tisho fell silent and looked at his bottle of beer. His eyes narrowed. “This beer says rock and roll,” he muttered. This realization seemed to unlock something in him. He rummaged in his backpack and extracted a large green can and set it on the table. It was beer.

“Bulgarian,” he announced with satisfaction. He picked up the can and splashed some into each American’s glass. Then he filled his own. The waiter didn’t seem to notice.

“That’s very kind of you,” said Ryan.

“It’s nice,” Our Journalist said after taking a sip.

“I’m nice too,” said Tisho.

Our Journalist agreed. There was a pause.

“So how big is the Bulgarian team?” Ryan asked.

“I am the only one,” Tisho said.

“What?”

Tisho shook his head sadly. “We’re in a very … difficult place right now. You will see.”

And here we must clarify: mountains can, but do not always, “bring people together.”

It was 2019, and the Bulgarians were in the hole.

The issue of the debt had begun in Val d’Arly, France, on a trip organized by the Belgian branch of the Ski Club of International Journalists. Four members of SCIJ Bulgaria had, with what some considered insufficient notice, canceled their trips to the French Alps after initially committing. This put the hosting Belgians in an uncomfortable position—they had already paid for the hotel rooms and buses. One of those Belgians was a man named Bruno Schmitz. The Bulgarians, he and certain members alleged, owed SCIJ sixteen hundred euros. The Bulgarians, other members alleged, did not; they had canceled well in advance. In 2023, Bruno Schmitz was elected as SCIJ’s secretary-general, whose duty it is to manage club finances. In his new role, Schmitz made debt collection something of a priority.

The debt sowed discord. So did some unsavory social media posts and text messages that may or may not have been related to it. What those posts and texts were certainly related to was the leader of the Bulgarians, Alex Bogoyavlenski.

“I like our Bulgarian friends,” Bruno has noted. “Alex, however, is a bit difficult.”

Alex had been the first Bulgarian to cancel his trip to Val d’Arly, citing “personal problems.” He vociferously refused to pay arrears for so doing. “I think Alex would prefer to take the money and burn it in front of us rather than pay up,” one SCIJ member would later tell Bruno. In 2023, further problems accrued: certain members of the Ski Club of International Journalists asserted that Alex Bogoyavlenski was, in fact, not a journalist. It must be admitted: Alex’s username on Instagram is thelazyflyer. He has three titles on LinkedIn: first “Commercial Pilot,” second “Digital Marketing Mastermind,” and then “Aviation Journalist.” He flies Boeing 737s and Airbus A220s for Bulgaria Air. There was talk of banishing Bogoyavlenski from the club.

***

“There’s so many schisms I could tell you about,” said a slight British woman.

“It’s part of the pleasure of SCIJ,” said a Canadian.

It was Welcome Night at the Villaggio Olimpico, the hotel in Bardonecchia that was hosting the skiing journalists for the week, and we were all getting acquainted—reporters from the Financial Times, editors from Agence France Presse, hosts from Radiotelevisione italiana. The hotel was reminiscent of a provisional hospital someone had forgotten to tear down. Inside, its walls were cold and white. Outside, it was painted a queasy green.

“Might one of those schisms have to do with Bulgaria?” asked Our Journalist.

The Brit’s eyes twinkled Britishly.

“You’ll see,” she said. It was time for dinner.

The skiing journalists filed over to the hotel cafeteria with their glühwein, ducking between swarms of swaggy Italian teens and tweens dressed in black. In the dining hall, there were chicken legs and roasted potatoes and big plastic pitchers of wine. Our Journalist sat across from a tall rosy Belgian who was, it emerged from their conversation, a lawyer, not a journalist. He was excited about the recent American elections.

“The average American … is so ignorant!” he said. “The average American … has no idea of history!”

Our Journalist glanced to his right. Tisho was off at a different table, concentrating on pouring wine into a plastic water bottle.

“The average American …”

Our Journalist looked to his left. Over in the lobby, a woman from SCIJ Italy had begun distributing ski passes and goody bags from behind a counter.

“… knows nothing of the world!”

Our Journalist excused himself to collect his goodies.

He thanked the woman behind the counter and peeked in the bag. There were 650 grams of salami, 466 grams of Parmigiano Reggiano, and a black notebook labeled PARMIGIANO REGGIANO.

“You accuse me?!” someone was shouting.

Our Journalist looked up from his salami. Hey, it was Tisho.

“We already gave you your pass!” hissed the Italian woman. She thought Tisho was trying to bamboozle her into giving him an extra bag.

“I got pass but not bag! You accuse me?!” Tisho touched his chest proudly.

“Take it and get out of here!” She flung the bag on the counter.

Tisho scowled. He was not satisfied.

“Apologize to me!” he said.

The Italian woman ignored him.

“You apologize to me!”

“Yeah, yeah. I’m sorry. Now please leave.”

Tisho swiped the goodies and stomped away. I insisted on my rights and got them, he thought.

***

Rumor is a river that runs two ways. Alex the Bulgarian stood accused, in essence, of refusing to repay a debt and of being a fraud. But it was said by other skiing journalists that the current president of SCIJ, a middle-aged Canadian named Frederick Wallace, was the one who was not a journalist. It was said that under his tenure six thousand euros in club funds had been spent with a suspicious lack of documentation. It was said that he was trampling on justice in his treatment of Alex Bogoyavlenski, who in fact had “over three-hundred authored publications and media projects in the past two years.” (Alex’s words.) And it was said that the Bulgarians were not really in debt: The Belgians had actually run a raffle at SCIJ 2019 to recoup their losses—and succeeded. The Belgians, it seemed to some, were thus after not sixteen hundred euros but revenge for the cancellation. It did not help that Wallace was currently serving a third term, in defiance, some believed, of current club statutes. SCIJ had come to seem like “the president’s fiefdom,” as one club member would put it. (“I have no comment,” the president told Our Journalist when asked about the intricacies of the Bulgarian Case.)

Adding to the Bulgarians’ rue was the fact that they had helped Wallace win his first presidential election so many years ago. That was in 2014. That was in Switzerland. That was a mistake. I gave him good advice, Alex Bogoyavlenski would remember of those days. He seemed like a reasonable guy. He had a business plan. Now Wallace had turned against him.

The issue took on a curious midcentury flavor. “I remain totally disgusted from the action against Alex; it is against all of us from the East,” one of Alex’s countrywomen messaged a German SCIJ member who’d cast doubt on the Bulgarian leader’s professional bona fides. Alex’s defender continued in an ominous vein: “It takes me efforts to abstain from comparison with German history.” Even some Westerners saw what this Bulgarian woman saw: autocracy. “This is the behaviour of a dictatorship, not a club of journalists,” a British member wrote in a SCIJ Facebook group.

***

The Americans headed up to their rooms after the first night’s dinner. They were weak and woozy. The pitchers of wine had been unlimited, the chicken sat uneasily in their stomachs, and they’d met a dizzying number of international journalists. They stepped out onto the balcony for some alpine air.

The voice seemed to come from above, and it sounded like …

“Tisho, is that you?” said Ryan.

“Where is that from,” said Tisho.

The Americans looked up to the floor above and saw an open window.

“We’re down here,” said Ryan.

A single hand crept slowly from the window overhead.

“We are … serving life sentence up here,” said Tisho. This seemed to be his way of saying he didn’t like the hotel.

“Tish!” said Valen.

“You have … balcony-terrace?” Tisho’s hand withdrew.

“Yeah!”

“I do not,” he said with a hint of envy. “I will come see what is there.”

Tisho shuffled into the Americans’ hotel room a few minutes later. His tie was loose and he was holding a plastic water bottle full of red wine. He looked around unimpressed. The accommodations at recent SCIJ gatherings had been rather more glamorous.

Our Journalist had heard about last year’s trip to Kazakhstan at the welcome dinner. The international journalists had been lodged at the Royal Tulip Hotel, a palatial resort with gilded columns, crystal chandeliers, marble floors, and a casino. It was there that SCIJ’s General Assembly had met to adjudicate what had come to be called the “Bulgarian Case.”

On account of his debt and pugnacity, Alex the Bulgarian had not been invited to the 2024 SCIJ meeting. Alex did not care. He had flown alone to Kazakhstan. He had shown up at the Royal Tulip Hotel and sat amid the General Assembly. He had defended himself valiantly against the allegations: pilot and journalist are not mutually exclusive professions, he had argued. He had then observed his clubmates’ own deliberations on The Bulgarian Case.

“Forget about the debt from SCIJ Bulgaria,” a merciful Dane proposed.

“We cannot forgive the debt,” said a merciless Kazakhstani.

“We should have had this conversation last year,” said a weary Croatian.

Eventually, the issue was resolved through a kind of deferral: a group called “the Committee of the Wise” was formed to determine, conclusively, what had happened. Later that year, this committee recommended that the Bulgarian debt be canceled. But this was only a recommendation, and it was in Bardonecchia, at the meeting of the General Assembly, on the third day of the seven-day trip, that all would be decided.

***

“C’mon!” screamed Our Journalist. His fellow Americans kept collapsing on the ski slope. The slope was called Baby 1.

It was their first full day in Bardonecchia, and they needed to practice. Chandler was from Phoenix, Arizona. Valen was from San Diego, California. They had never skied before. Valen had scarcely seen snow. Our Journalist had to whip Team USA into shape before the SCIJ 2025 race. It was just four days away, and the week’s main event. The rest of the week, club members were free to ski as they pleased.

There was a race every year, and the club members approached it with gravity and resolve. The Italians were known to wear matching red jackets. The Kazakhstanis were known to wear matching blue coats. Injuries had been sustained in the quest for speed and glory. A Dutchwoman had once sustained a concussion; a Slovenian had busted a knee; an Irishwoman had broken an arm.

“I wanna see less pizza and more hot dog!” screamed Our Journalist.

Chandler put his skis in parallel position and spun around and collapsed. Valen was in the snow trying to get up. Our Journalist turned sharply and tumbled too. Little Italians zoomed by.

Bambini, Our Journalist thought. When he was a bambino himself, he had learned to ski at Appalachian resorts dusted with artificial snow, on the meager mounds of Virginia and West Virginia. Italy was something else.

After a few more runs on Baby 1, they tried Baby 2. It was slightly steeper.

“Lean more on your back leg!” Our Journalist called across the snow. He wasn’t sure he knew what he was talking about. “It’s like you’re sitting in a chair!” Chandler grazed a small child.

They decided to take a break at Harald’s Ski Restaurant, at the bottom of Baby 2. They ate lukewarm cheeseburgers and drank pints of beer under long timber beams.

“My skis keep getting crossed,” said Chandler.

“One of my legs is better than the other,” said Valen.

“You guys are doing great,” said Our Journalist.

They returned to the slopes and spent four more hours hurtling downhill. They needed the practice. And it would feel good to celebrate that evening’s Nations Night after a long hard day of skiing.

Nations Night is an old SCIJ tradition, a chance to drink, dance, and share one’s cherished native cuisine with fellow skiing journalists. “The Slovenians and Croatians make a very rich Nations Night,” Tisho had approvingly told Our Journalist back when they first met: It was a standard to which one wished to live up,. But every American, it soon became clear, had forgotten to bring foodstuffs from back home. This was bad optics for Team USA.

A few hours before the party kicked off, Ryan and Our Journalist recalled the words of a subeditor for the Times of London: “We just bring whiskey cuz no one wants to eat British food.” Here was an idea. Following an après-ski dinner, they set off into town to procure some American hooch.

They wandered through the snow and streetlights of Bardonecchia. The grocery stores were closed. The liquor stores were closed. It was time to get resourceful. They walked into a bar.

“Posso comprare tutta una bottiglia di Jack Daniels?” Our Journalist struggled to say.

The barman was somber. “I ask,” he said, and ducked into the back.

He returned. “Non è possibile.”

“What if we pay a premium?” said Ryan.

“I ask,” said the barman. He ducked away again.

The barman was grave. “Sessanta euro.”

“We’ll take it,” said Ryan.

They walked back to the hotel, out of the cold, into the warm bosom of Nations Night, and were whopped by a musky, dark, magnificent smell … the many cured meats of Europe and Eurasia … fermented milks and fermented grains … raw mollusks and salted cod … goat cheese and anchovies and sausage and wine … a thrilling blend of sounds and deep stenches … the French cracking oysters … the Swiss melting raclette…the Kazakhstanis slicing some kind of dried animal leg … the Canadians pouring maple syrup on snow… an Italian DJ playing Linkin Park’s “Numb” …

The Americans began serving up shots at the Team USA table.

“I looove Jack Daniels,” a German woman moaned in a baritone. “I looove Jack Daniels.”

Our Journalist looked elsewhere. Tisho was over in the corner, seated solo behind the Team Bulgaria table.

Tisho acknowledged him with a tired nod. “Bulgarian grappa, from grapes,” he said. He lifted a tall thin glass bottle. “It’s natural.”

Our Journalist drank a cup. Tisho was less energetic than yesterday, but he was as bighearted as ever, and Our Journalist’s presence seemed to animate him.

“Bulgarian salami,” Tisho continued. He gestured toward a dark pile of meat-sticks on a plate. Our Journalist thanked him and chewed on one.

“It’s delicious,” Our Journalist said.

This seemed to uplift Tisho even more. He suddenly picked up the plate and stood and began calling out into the party, “Come! Bulgarian salami!” There was light in his eyes.

***

The day after Nations Night found the international skiing journalists a slightly haggard and crapulent bunch. Still, the club members had political responsibilities to fulfill. The General Assembly was tonight, and upon its unfolding Bulgaria’s fate would depend.

Despite the austerity of its decor, Bardonecchia’s Villaggio Olimpico hotel was rich in special features. Its basement held a pool and a discotheque; its ground floor had a “Lounge Bar.” Close by the lounge was the theater, and in the theater the General Assembly of SCIJ was about to meet.