A Little Ghost, Barbara Guest, and Me

FROM PRABUDDHA DASGUPTA’s portfolio Longing in THE SPRING 2012 ISSUE OF THE PARIS REVIEW.

I don’t love being stoned, but I love being stoned in museums. Cannabis makes me quiet and uncertain, or chatty and self-conscious, which winds back to quiet and uncertain. Alone in a museum, however, the mind’s defenselessness—what divides me from all other objects is, it turns out, as sturdy as a sheet of wet tissue paper—no longer seems dangerous. I drift from room to room, pleased to dissolve into the art.

So, I took a low-dose edible upon arriving at the Museum of Modern Art on a September afternoon two years ago. I was there on assignment to write a poem about a piece in the permanent collection; I’d chosen a collotype by Eadweard Muybridge. As it wasn’t on display, I had an appointment in the photography department. A curator ushered me into a large room, all beige and white. In the center of the room stood a large table and a single chair, angled toward the window, which took up almost the entirety of one wall and looked out onto West Fifty-Third Street. The collotype, sleeved in plastic, lay waiting on the table. Woman Dancing (Fancy), one plate from Muybridge’s massive Animal Locomotion project, shows a woman in diaphanous white twirling across a black background. For an hour I took notes sober, and then, after my thoughts went wispy, for an hour stoned. Across the street, grass sprang from low gray clouds. A roof garden. A pleasant vacancy resolved: done here. I would wander the galleries, I decided, until the edible wore off.

Down a flight of stairs, through an archway, I saw black rotary telephones arranged on plinths. The gallery wasn’t crowded; people moved through it like migrating animals, undistracted from loftier destinations. “Dial-A-Poem,” the wall text, blown up, sans serif, read. I lifted a receiver, thinking of my grandmother, who taught me to dial on her rotary phone. I’d loved the swing and catch, how you had to wait for each electrical pulse to send. It made a game of communication. In 1968, the artist and poet John Giorno created Dial-A-Poem, catchily and accurately named: call a telephone number and listen to a poem read by its author. Giorno got some of the best minds of his generation to contribute: John Ashbery, Diane di Prima, Amiri Baraka … the famous names roll on and on. This room reincarnated a MoMA exhibit, phones randomizing through two hundred poems, from decades earlier. Giorno died in 2019. Now, in my ear, he theatrically elongated an introduction: “Diiiiiaaaaal a Poooome‚” “poem” converted to defiant monosyllable, and “Baaaaarbaraaaa Guest.” Then a woman’s tailored voice took control. People used to apply more drama to enunciation: they both sounded like minor characters in All About Eve or The Philadelphia Story. “Door bells,” Barbara Guest said, divorcing the compound with a pause.

The poem was simple, startling, one minute long. In the words, I recognized the perfect encapsulation of a thought I hadn’t known to think. The experience reminded me of the first time that words in another language became more than sound to me. In the wake of comprehension, I felt starved for more sense. I wanted to listen to it again and again. Wonder is an astonishment that births delight, and then curiosity.

It’s impossible to hold the whole of a poem in your head the first time you hear it. At best, you may hang on to a phrase; if you’re lucky, a whole crystalline image. I hastily typed two lines of this one into my Notes app: “I wish to change the filigree of our subjects” and “beware of intimacy it is only a footbridge.” Guest read another poem, none of which I retained. A pause, like a radio tuned to nothing. The next poem, by someone I’ve forgotten, started. It didn’t matter.

***

Those lines kept their power even after the return of sobriety—even in the B train’s orange envelope, where I first tried to search for the poem’s text, with no luck. I blamed Google’s turn toward uselessness, and the rickety connection on the subway. I’d try again at home. But there I also had no luck, though I tried all the tricks I knew for sifting truth from trash. “I wish to change the filigree of our subjects” ended up in the poem I wrote, which emerged as a headlong tumble, a manic attempt to diagnose and describe the relations between stillness and motion, dance and language, love and violence. When I’d chosen the collotype, I hadn’t known that Muybridge had killed his wife’s lover, and in the poem I made into lyric my entirely prosaic discomfort over the fact that I’d devoted hours of attention to the work of a murderer when my own brother had, two years before, been murdered. I did wish to change the filigree of my subjects: if not to escape the death that governed my thoughts, then at least to dodge the repetition of its old ornaments.

All autumn, I kept telling people about this Barbara Guest poem I’d heard and couldn’t find. Her poetry wasn’t entirely new to me. In graduate school, she’d been the lone woman to appear under “The New York School” on a syllabus. The author of more than twenty poetry collections, many essays, a biography of the poet H.D., an experimental novel, and several plays, she was overshadowed in the classroom discussion by her male contemporaries, Ashbery and the ineradicably popular Frank O’Hara. My obsession might have ebbed into a more reasonable appreciation had I been able to find the text of the poem anywhere. But it couldn’t be found online, nor did it appear in The Collected Poems of Barbara Guest, which I read straight through, in case the poem, or at least some of its lines, appeared under a different title. Nothing. No doorbells. Or door bells.

At first, I read like a student hunting for a suitable quote to squash into an essay, clock ticking down to deadline. Then I simply began to read. In Guest’s poems, the thoughts, impressions, images spring into being the way that God creates in Genesis, unapologetically strange and fully formed: “I am talking to you / With what is left of me written off, / On the cuff, ancestral and vague, / As a monkey walks through the many fires / Of the jungle while a village breathes in its sleep.” Some of the poems hew closer to an O’Hara-esque “I do this, I do that” reportage of turbocharged perception, whereas others draw together fancifulness and the habit of turning matter into metaphysics in the way that a great Ashbery poem does. She interpolates The Tale of Genji and Gertrude Stein as well as the pains of, presumably, her own life: “I am in love with him / Who only among the invited hastens my speech.”

And, throughout, there is art as subject: both the making and the thing made. In these poems, she writes of how “an emphasis falls on reality” through the artist’s way of seeing. If she begins envious of “fair realism,” then soon enough there is no reason for envy, as the real world conforms to the imaginative vision and a “drawn” house becomes real enough to move into, among “the darkened copies of all trees.” There’s a symbiotic grace here, a sense that art and reality are so intertwined that what the poet sees can be reported as calmly as any journalistic observation. A relaxed confidence pervades stanzas like “if I spoke loudly enough, / knowing the arc from real to phantom, / the fall of my voice would be, / a dying brown.” Thus these lines, in context, appear wholly natural yet still surprising. The force that binds and propels the poems never strains after intelligibility. This is the way, in Guest’s imaginative universe, that poetry should be: “Respect your private language,” she instructs in one essay. In her tenacious respect for her own, Guest reminds me of Anne Carson; both are so blithely unconcerned with making sense to anyone but themselves that it isn’t clear they understand the extent of the faith they place in a perfectly personal logic. (The truest believers don’t recognize an alternative to belief.) Guest’s poems, like Ashbery’s, often develop via sound, image, and coincident gesture, and, as with Ashbery’s, meaning seems not irrelevant, exactly, but subsidiary to the primary pleasure, also the primary purpose: language. Gorgeous sentences abound, but the line—“that nude, audacious line,” in Guest’s words—is the star. Compact phrases delight, one after another: “I impart to my silences / operas”; “this pharmacy / turns our desire into medicines and revokes the rain”; “the Church of // Our Lady cried Enough”; “It is the hour for decisions and I am going to take a little nap.” It’s possible to read Guest’s work with no attention to a poem’s larger significance and still feel the distinctive bliss of illumination. As if summoned from another world, a density of ideas and feelings takes shape and then passes, quick as a cloud. Even writing itself renews when the classical Muses return to an earth that is “no longer fragrant” and loose birds in a bedroom near “that old shawl in the corner.” Guest portrays the inspiration that dislodges poems as a dizzying, unrestrained, inexplicable, profane miracle: “The room fills now with feathers, / the birds you have released, Muses, // I want to stop whatever I am doing / and listen to their marvelous hello.”

***

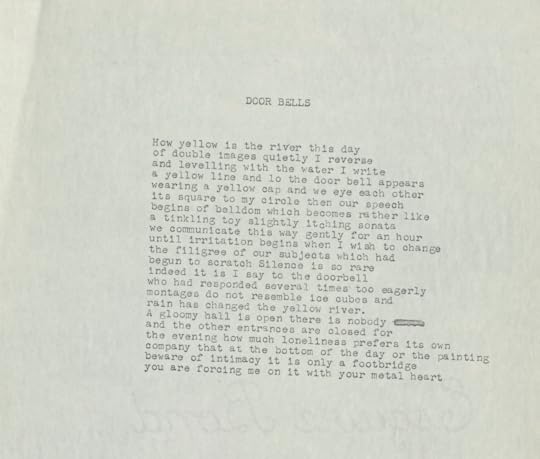

The search for the text of “Doorbells” (“Door Bells”?) became a minor quest running parallel to my real-life commitments. MoMA did not have any texts for the Dial-A-Poem exhibit. Nor did they have digital audio recordings to share. The Dial-A-Poem hotline still exists—at +1 (917) 994-8949—so my best friend and I called and called in an attempt to record the poem so I could transcribe it, but after dialing 103 times and then hanging up before dozens of excellent poems had time to get going, I conceded that this was a flawed strategy. Also, a transcription would offer only the words, and a poem stripped of its line breaks is a mutilated creature. I emailed the John Giorno Foundation, which provided the audio recording. Progress! I could slow it down, replay, get all the words as close to right as possible. Then I located pages in the Barbara Guest archives at Yale University that I thought might be the right poem—right title, right year. These pages had not been digitized or transcribed, so it was merely a list in the online catalogue: three typewritten drafts, box 53. My first impulse was to take the train to New Haven to check for myself, but, after lecturing myself on practicality (I mean really, a whole day spent working toward the possibility of solving a problem I’d created, irrelevant to my life), I settled for requesting a scan from the reference librarians. I waited. And there, at last, it appeared in my inbox as a downloadable PDF: the fulfillment of desire, the end of the quest. “Door Bells,” after all.

Photograph courtesy of the Beinecke Library and the Barbara Guest Estate.

I’d thought I would feel more triumph. As soon as I opened the PDF, my usual mode of textual engagement took over: it was just another poem. It was like starting to date a long-term crush. The fantasy simulacrum collapses, and then a new relationship must begin based on what’s actually there—a realism, fair or not.

***

Door Bells

How yellow is the river this day

of double images quietly I reverse

and levelling with the water I write

a yellow line and lo the door bell appears

wearing a yellow cap and we eye each other

its square to my circle then our speech

begins of belldom which becomes rather like

a tinkling toy slightly itching sonata

we communicate this way gently for an hour

until irritation begins when I wish to change

the filigree of our subjects which had

begun to scratch Silence is so rare

indeed it is I say to the doorbell

who had responded several times too eagerly

montages do not resemble ice cubes and

rain has changed the yellow river.

A gloomy hall is open there is nobody

and the other entrances are closed for

the evening how much loneliness prefers its own

company that at the bottom of the day or the painting

beware of intimacy it is only a footbridge

you are forcing me on it with your metal heart

“The poem begins in silence,” Guest wrote elsewhere, and I read this poem as a disputation with noise, with everything that interferes with the poet’s hearing the poem. That extra space between door and bells emphasizes the threshold’s precarious gap. The bell is embodied, autonomized, but of course a bell rings when a person rings it, and so the poem also engages, obliquely, the problem of human companionship, which a writer both craves and resents. Other people distract the poet from the writing; more dangerously, they may make it impossible to achieve the state of mind—the inner silence—required to write. Still, it is a “gloomy hall” that contains no open doors to other rooms and other lives, and “loneliness,” after all, is Guest’s choice over neutral “solitude.” But if intimacy connects us to others, then how far does that connection extend, and where does it take us? Is the reason to beware intimacy that it cannot take us as far in art as loneliness? Or is the problem that it’s “only a footbridge” rather than a place to arrive? For a writer, for any artist, I think, work and the rest of life, all the love and pain and obligation of personhood, necessarily conflict. The tension Guest enacts here never resolves. It just reiterates. Sometimes you sit with loneliness. Sometimes you obey the metal heart.

I do not know why Guest never included “Door Bells” in a book. Maybe she wrote it for Giorno’s project and never considered it outside that context. (The other poem she read, “Passage,” appears in Moscow Mansions.) Was it discarded or just forgotten? Guest died in 2006, so I can’t ask. She left behind a vast body of work, including a recently released collection of her prose, Meditations, which includes her strange, gifted, koanic essays on writing. A poem, she writes in the essay “Wounded Joy,” is a text that creates a gap between what’s expressed and what can never be expressed that does not attempt to hide this gap from the reader. We are supposed to hear the silence of what cannot be said: “no matter what there is on the written page something appears to be in back of everything that is said, a little ghost. I judge that this ghost is there to remind us there is always more, an elsewhere, a hiddenness, a secondary form of speech, an eye blink.” The poet must neither draw it out nor send it scurrying into the ether. To let it be—that is the crux of the poet’s task: “Leave this little echo to haunt the poem … It has the shape of your own soul as you write.”

***

I cared an inordinate amount about locating this poem. I attributed this to my tendency toward what a poet friend, Jameson Fitzpatrick, calls Rococo plot: harmless flourishes, small dramas, that bedazzle the everyday. The plotter’s drive is to make life, above all, more narratable. Once I invented the dilemma, the story demanded gratification. Rococo plot is a relaxed manifestation of Bovarysme, the term (derived from Flaubert’s tragically deluded Emma Bovary) for daydreaming oneself away from the boredom of reality. Emma’s demise comes via romantic novels, and discussions of Bovarysme treat falling under the influence of literature like taking fentanyl. (An internet-era version of the diagnosis is main character syndrome.) But, as T. S. Eliot noted, this “human will to see things as they are not” is just that: human.

But this answer, the first that came to mind, didn’t seem to quite account for the work, unglamorous and frustrating, I’d done to arrive at the poem. For a while I shrugged off the slight dissonance. Later, I recognized the presence, throughout this hunt, of my own little ghost. I hadn’t meant to write my dead brother into my own poem, but it couldn’t be helped. The grief is no filigree. It’s the form and the subject and the dark matter, too. I’d pursued this quest at least in part because my reality was suffused in a bleakness that I wished to believe was possible to dispel. In working to distract myself from my own thoughts, I also groped after the possibility of understanding and beauty within an everywhere sadness. That now seems the revelation “Door Bells” brought: there is the ineradicable, uneasy coexistence of silence and noise; there is also the ineradicable, uneasy coexistence of art and plain agony. All joy is wounded joy.

Elisa Gonzalez is a poet, fiction writer, and essayist. She is the author of the poetry collection Grand Tour.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers